Mortality following acute myocardial infarction (AMI)

Mortality due to coronary heart disease has declined substantially since the 1970s (see indicator “Mortality from circulatory diseases” in Chapter 3). Important advances in both prevention policies, such as for smoking (see indicator “Smoking among adults” in Chapter 4), and treatment of cardiovascular diseases have contributed to these declines (OECD, 2015a).

A good indicator of acute care quality is the 30-day AMI case-fatality rate. The measure reflects the processes of care, such as timely transport of patients and effective medical interventions. The indicator is influenced by not only the quality of care provided in hospitals but also differences in hospital transfers, average length of stay and AMI severity.

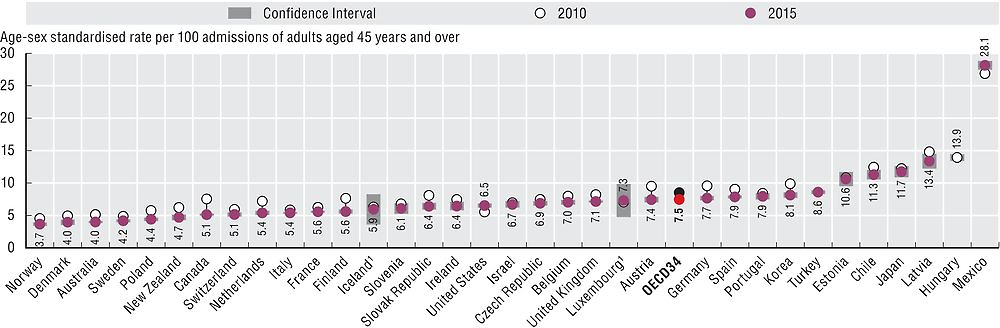

Figure 6.17 shows the case-fatality rates within 30 days of admission for AMI where the death occurs in the same hospital as the initial AMI admission. The lowest rates are found in Australia, Denmark and Norway (all 4% or less). The highest rates are in Latvia, Hungary and Mexico, suggesting AMI patients do not always receive recommended care. In Mexico, the absence of a coordinated system of care between primary care and hospitals may have contributed to delays in repurfusion and low rates of angioplasty (Martínez-Sánchez, 2017). High rates of uncontrolled diabetes may also be a contributing factor in explaining the high AMI case-fatality rates (see indicator “Diabetes care” in Chapter 6) as patients with diabetes have worse outcomes after AMI compared to those without diabetes, particularly if the diabetes is poorly controlled. In Japan, people are less likely to die of heart disease overall, but are more likely to die once admitted into hospital for AMI compared to many other OECD countries. One possible explanation is that the severity of patients’ admitted to hospital with AMI may be more advanced among a smaller group of people across the population, but could also reflect underlying differences in emergency care, diagnosis and treatment patterns (OECD, 2015b).

Note: 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for all countries, represented by grey areas.

1. Three-year average.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

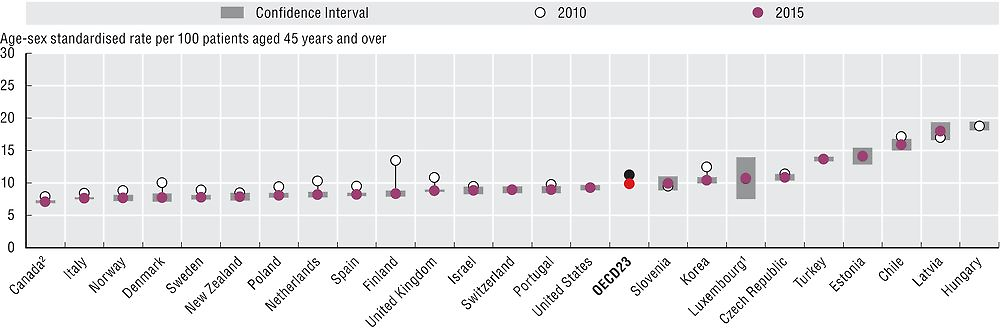

Figure 6.18 shows 30-day case fatality rates where fatalities are recorded regardless of where they occur (after transfer to another hospital or after discharge). This is a more robust indicator because it records deaths more widely than the same-hospital indicator, but it requires a unique patient identifier and linked data which is not available in all countries. The AMI case-fatality rate ranges in 2015 from 7.1% in Canada to 18% in Latvia.

Note: 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for all countries, represented by grey areas.

1. Three-year average.

2. Results for Canada do not include deaths outside of acute care hospitals.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

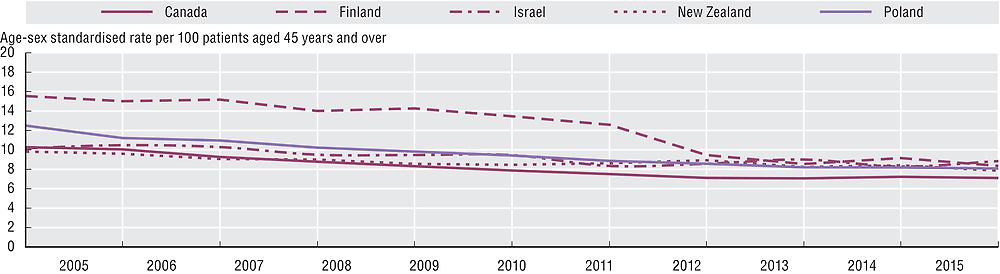

Case-fatality rates for AMI have decreased substantially between 2005 and 2015 (Figures 6.17 and 6.18). Across the OECD, case fatalities fell from 8.5% to 7.5% when considering same hospital deaths and from 11.3% to 9.9% when considering deaths occurred in and out of hospital. The rate of decline was particularly striking in Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark, when considering deaths occurred in and out of hospital, with an average annual reduction of over 4% compared to the OECD average of 2.5%.

Figure 6.19 illustrates the evolution of the decline in AMI case fatality rates for selected countries. Better access to high-quality acute care for heart attack, including timely transportation of patients, evidence-based medical interventions and specialised health facilities such as percutaneous catheter intervention-capable centres have helped to reduce 30-day case-fatality rates (OECD, 2015a). For example, Korea had higher case-fatality rates for AMI but in 2006 it has implemented a Comprehensive Plan for CVD, encompassing prevention, primary care and acute CVD care (OECD, 2012). Under the Plan, specialised services were enhanced through a creation of regional cardio and cerebrovascular centres throughout the country, and average waiting time from emergency room arrival to initiation of catheterisation fell from 72.3 in 2010 to 65.8 minutes in 2011, leading to a reduction in case-fatality (OECD, 2015a).

The case-fatality rate measures the percentage of people aged 45 and over who die within 30 days following admission to hospital for a specific acute condition. Rates based on unlinked data refer to a situation where the death occurred in the same hospital as the initial admission. Rates based on linked data refer to a situation where the death occurred in the same hospital, a different hospital, or out of hospital. While the linked data based method is considered more robust, it requires a unique patient identifier to link the data across the relevant datasets which is not available in all countries.

Rates are age-sex standardised to the 2010 OECD population aged 45+ admitted to hospital for a specific acute condition such as AMI (ICD-10 I21, I22) and ischaemic stroke (ICD-10 I63-I64).

References

Martínez-Sánchez, C. et al. (2017), “Reperfusion Therapy of Myocardial Infarction in Mexico: A Challenge for Modern Cardiology”, Archivos de cardiología de México, Vol. 87, No. 2, pp 144-150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acmx.2016.12.007.

OECD (2015a), Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: Policies for Better Health and Quality of Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233010-en.

OECD (2015b), OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Japan 2015: Raising Standards, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264225817-en.

OECD (2012), OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Korea 2012: Raising Standards, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264173446-en.