1. Key policy insights

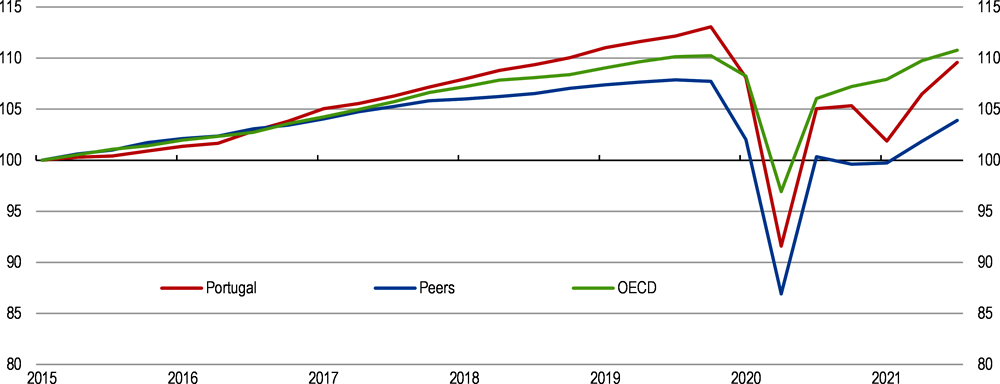

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised multiple challenges for Portugal and exacerbated existing weaknesses. It triggered a major health crisis, reversed the strong recovery from the last downturn and caused the deepest post-war recession (Figure 1.1). The economy recovered fast, supported by the policy response notably the provision of income support, measures facilitating credit expansion and supporting job retention (Box 1.1). In addition, Portugal has managed to have one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide, notably for older persons, who are almost fully vaccinated. However, virus mutations might complicate the containment of the virus and the authorities should keep encouraging its population to take vaccination boosters. Supportive economic policies must be maintained to prevent this crisis from leaving profound scars on the economy and the society.

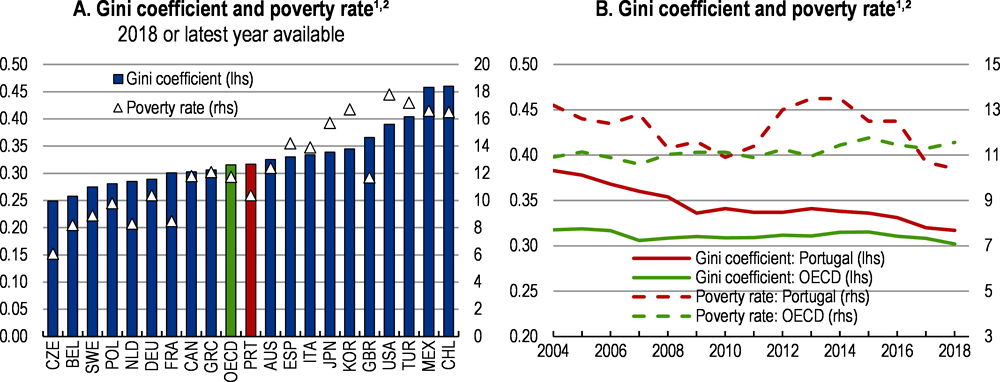

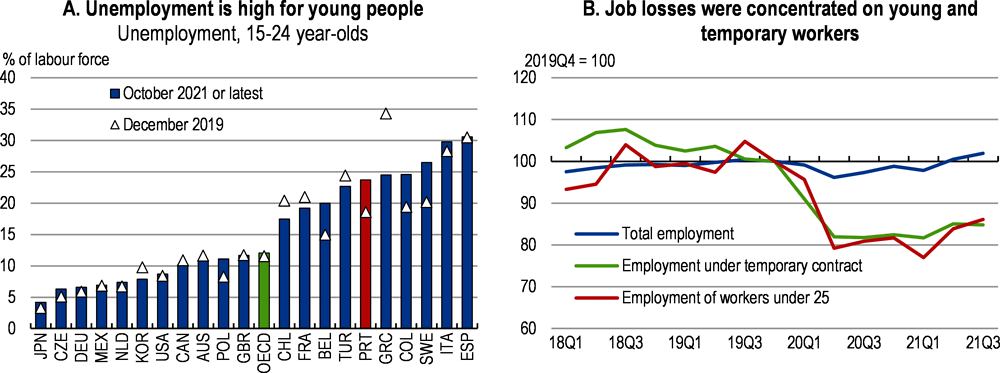

The pandemic has significantly affected living standards. The disproportionate impact of the crisis on sectors with abundant seasonal, temporary and low-paid jobs, such as hospitality and tourism, and on people with pre-existing financial difficulties may reverse the progress made in reducing poverty and inequality levels in recent years (Figure 1.2). By the end of 2020, the number of people receiving income support in the form of unemployment benefits and the number of registered unemployed increased by around 40% and 30% respectively compared to 2019. Women, youth, and low-skilled workers were overrepresented among the newly registered unemployed (IEFP, 2020). The crisis also risks aggravating low self-perception of well-being (OECD, 2019a).

Portugal’s policy response to the COVID-19 crisis has been broad, with a relatively high number of measures put in place in 2020. Measures aimed first at providing income continuity for workers and liquidity support to businesses to ensure they can restart operations after the lifting of containment measures. The government expanded or re-introduced these measures in early 2021 in the wake of a second national lockdown and in summer 2021 in response to the fourth wave. Other measures aimed at stimulating the recovery included the extension of the income support measures for vulnerable households and firms, an extraordinary tax credit for investment, and new credit lines with State guarantees. Direct aid through subsidies or tax cuts was less used than on average in the EU, while guarantees and moratoria accounted for a large share of the policy support (ESRB, 2021). The budget cost of direct measures is estimated at EUR 4.5 billion in 2020 (around 2.2% of 2020 GDP) and EUR 5.6 billion in 2021 (around 2.6% of 2021 GDP).

Job retention measures: Under the simplified lay-off scheme (from March to August 2020, reintroduced in January 2021), workers with reduced working hours in firms closed due to containment measures or with turnover down by more than 40% received 2/3 of their gross wage (up to EUR 1950 per month, 30% paid by the employer and 70% by the social security). Since January 2021, the replacement rate for hours not worked has been increased to 100% (up to three minimum wages) and the compensation paid by firms maintained at around 20%. A new scheme, Apoio à Retoma Progressiva, replaced the simplified lay-off scheme in August 2020 for firms not covered by administrative restrictions, with compensation of hours not worked and exemptions to social security contributions varying according to the drop in turnover and the size of the firm. A one-off support for each worker covered by the simplified lay-off scheme was also introduced in August 2020 (one or two minimum wage per worker).

Measures to support individuals in affected sectors include a top-up to employees and self-employed and the creation of a special benefit for informal workers. The maximum possible duration of unemployment benefit payments and sick-leave entitlements for people with COVID-19 and isolation entitlements have been increased.

Liquidity measures include a moratorium on banks loan repayments for firms and households affected by the pandemic (until September 2021) and a moratorium and interest-free credit for rent payments in case of income losses (until September 2020). The Retomar programme launched in September 2021, facilitates the restructuring of credit operations that were in moratorium, introducing a new principal grace period and maturity extension.

Around EUR 8.9 billion of State guaranteed credit lines have been allocated between March 2020 and November 2021. Capital was injected in private companies, including the national airline company (TAP). Between the end of 2020 and October 2021, almost EUR 1.2 billion of grants have been allocated to micro, small and medium-sized firms that lost over 25% of their turnover during the pandemic to help cover their non-wage fixed costs (with a cap, Apoiar.pt programme) and a share of their rents (Apoiar Rendas).

Tax measures notably include the extension of deadline payments for tax and social security contributions, a VAT relief on spending on accommodation, culture and restaurants in the form of vouchers.

Digital initiatives included the development of platforms and applications to coordinate the availability of hospital resources and the hotel occupation to support COVID-19 health professionals, to trace and communicate with COVID-19 suspects and home patients, to support digital home schooling. Digital service infrastructures were reinforced to deal with higher demand. Public services digitalisation accelerated mainly through the national digital gateway (ePortugal) and key administrative modernisation initiatives (i.e. the Digital Mobile Key, see Chapter 2)

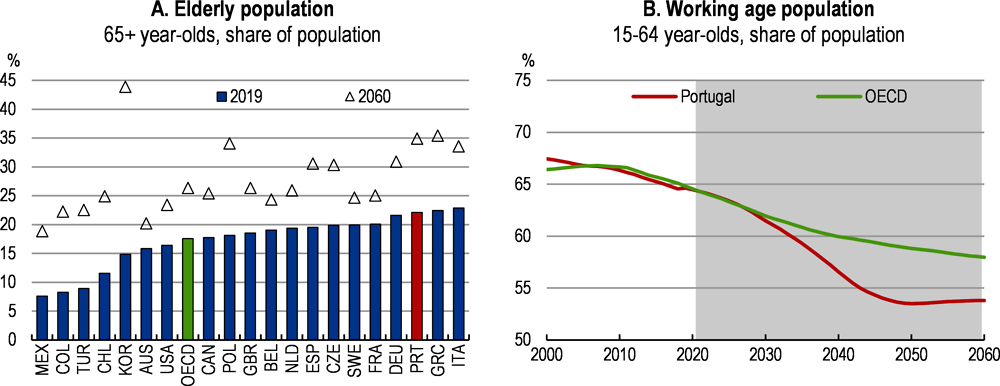

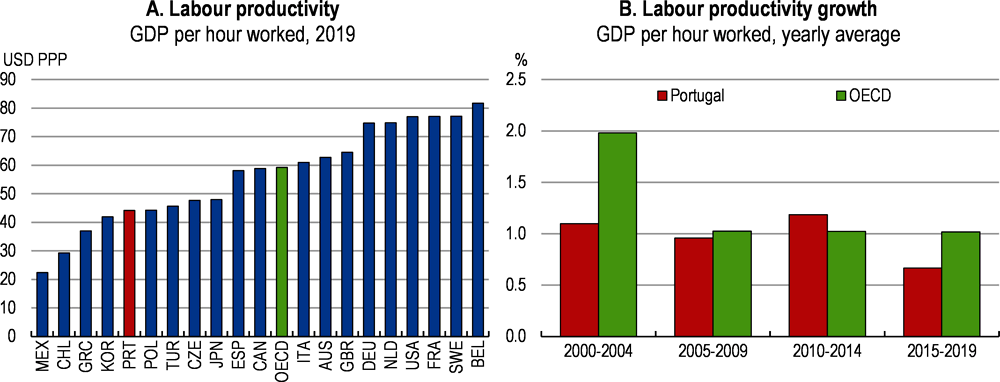

Portugal needs a strong policy response to avoid a deterioration in living standards and put growth on a sustainable and resilient path. With an ageing and fast-shrinking working age population (Figure 1.3), future growth will hinge on productivity gains. At the same time, like in most OECD countries, productivity growth has been low (Figure 1.4), and the COVID-19 crisis has already put a drag on productivity drivers, including business dynamism and investment. A package of reforms can bring substantial support to the recovery and long-term growth without derailing public finances. Portugal should seize the opportunity provided by the massive financial support from the EU to initiate positive socio-economic changes and address long-term challenges, including climate change and the digital revolution.

Against this background, the main messages of the Survey are the following:

Policy needs to remain supportive until the recovery from the pandemic is well underway. In parallel, the government should design a prudent fiscal consolidation trajectory and implement it once the recovery is firmly established.

A resilient, sustainable, and inclusive recovery hinges on the capacity to improve access to healthcare, support viable firms and jobs, transition to greener technologies, prevent a rise in poverty and social exclusion, and cope with an ageing population.

Accelerating the digital transition is central to facilitate the changes of the economy to a post-pandemic world, while boosting productivity growth. This notably requires equipping the population with adequate skills, expanding communication infrastructure and supporting technology adoption by small firms.

The COVID-19 outbreak has triggered a major health crisis

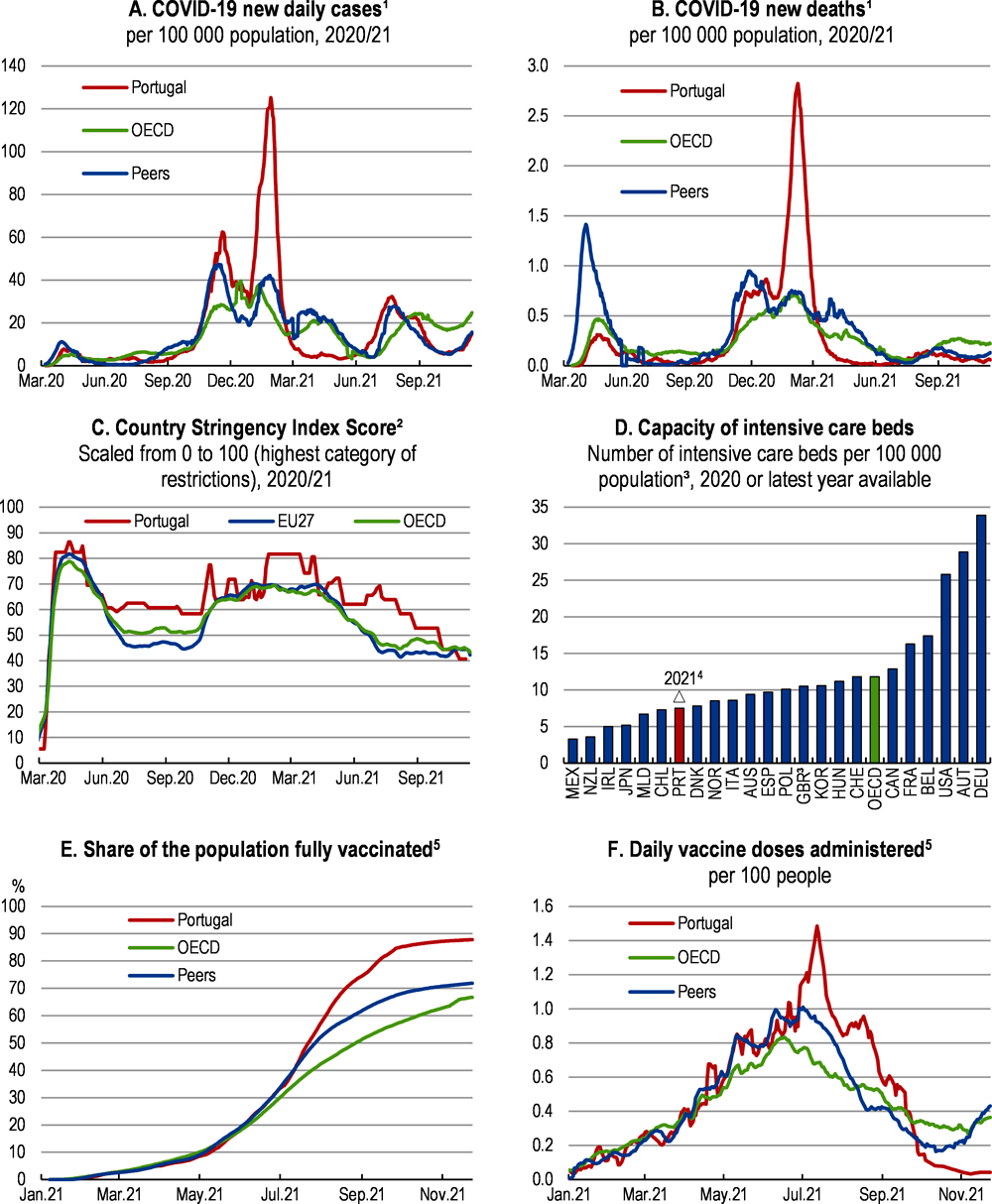

While Portugal has been less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than many other European countries during the first wave of the virus, subsequent waves hit the country hard (Figure 1.5, Panel A and B). In January 2021, Portugal had the highest rates of new infections and deaths worldwide. Some relaxation during the Christmas’ period in 2020 combined with the emergence of a more contagious virus variant led to a fast rise in infections. The partial lockdown and geographically targeted containment measures introduced in response up to mid-January 2021 were insufficient to slow the spread of the virus. The number of infections declined with the introduction of a second lockdown on 15 January. As Portugal has low hospital and intensive care units (ICU) capacities (Figure 1.5, Panel D), the virus surge put strong pressure on the healthcare system, with hospitals reaching full occupancy rates in early 2021 (Reuters, 2021). With the emergence of new variants of the virus, accelerating planned increases in hospital capacity, including ICU beds, remains crucial. The number of ICU beds increased significantly in 2020 (Figure 1.5) and is planned to reach the OECD average in 2021.

The high vaccination rate of the population, which is a major achievement of Portugal, likely played a crucial role in moderating the fourth wave of the pandemic. Like most European countries, Portugal started its vaccination campaign at the end of December 2020. Despite the rollout of vaccination being initially relatively slow, like in most European countries, Portugal has managed to reach the highest vaccination rate in the OECD, with more than 85% of the population fully vaccinated. However, due to high uncertainty regarding virus mutations, physical distancing measures, testing, tracing and isolating measures will remain key to control the fifth wave of the virus and other future surges in infections though.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated critical gaps and deficiencies in the healthcare system, especially long waiting times for specialised care. In 2020, hospital emergency attendance has declined by almost 30% and more than one-third of the population reported having forgone a needed medical examination or treatment during the first wave of the pandemic (OECD, 2021a). People with chronic health conditions have faced major disruptions to routine care. Hospital waiting times for surgery and outpatient appointments increased and non-essential operations were delayed. This will result in a significant backlog of surgeries that will likely take some time to be resolved after the crisis.

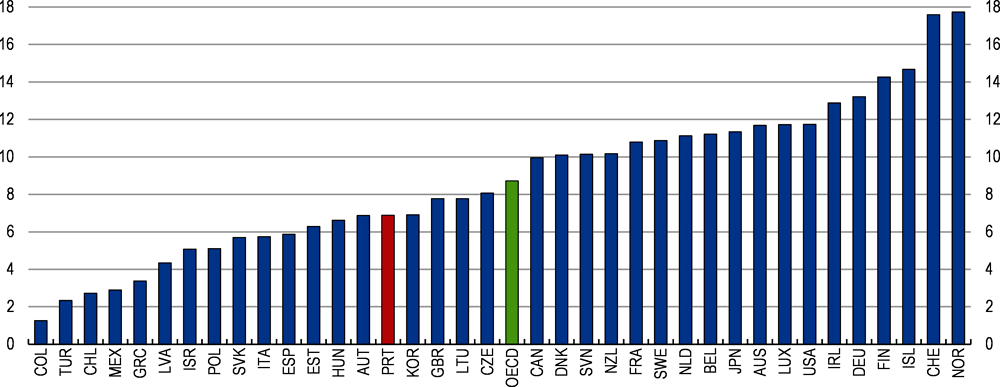

Proper access to medical care requires a sufficient number of doctors, with an adequate mix of generalists and specialists and a balanced geographic distribution to serve the population across the whole country. The COVID-19 pandemic substantially increased the workload of most health workers, accentuating shortages in the health workforce. The number of practising doctors is estimated to be slightly below the EU average (OECD, 2020a). Shortages are particularly critical for nurses (Figure 1.6), as they tend to emigrate due to large differences in remuneration level and career opportunities abroad (Simões et al., 2017). Current plans to improve working conditions of health professionals are thus a welcome step forward. A number of OECD countries have taken actions to improve service availability either by targeting medical students early in their training or by providing financial incentives to practice in underserved areas. A more widespread use of telemedicine could also help to improve access to healthcare (see Chapter 2).

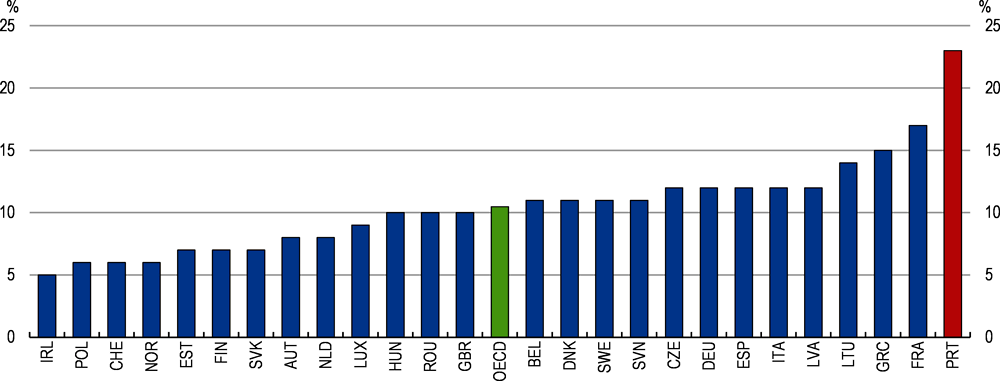

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated mental health problems particularly for people with pre-existing mental health disorders. In Portugal, over 20% of adults reported symptoms of psychological distress before the crisis, one of the highest rates across Europe (Figure 1.7). Empirical evidence shows that community mental health services are much more effective to address mental distress, and are preferred by patients and their families, but the provision of such services is limited in Portugal, especially in rural areas (Perelman et al., 2018). The Portuguese mental health system is centred on hospitalisation treatment and emergency consultations, unevenly distributed in the country (WHO, 2018; Perelman et al., 2018). The government plans to phase out user charges for psychiatrists in hospitals, but this will not be sufficient to improve accessibility. Portugal needs to implement a comprehensive mental health strategy that includes prevention and promotion. It is thus welcome that the Recovery and Resilience Plan includes measures to enforce the National Mental Health Plan adopted in 2008.

The economic recovery is fraught with risks

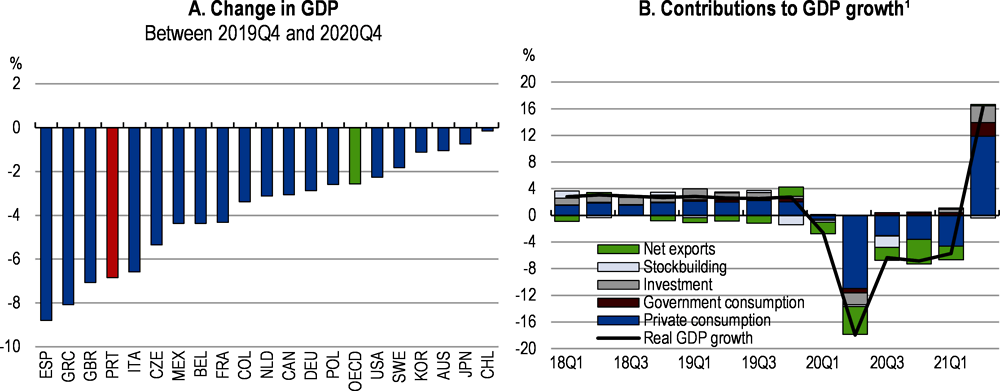

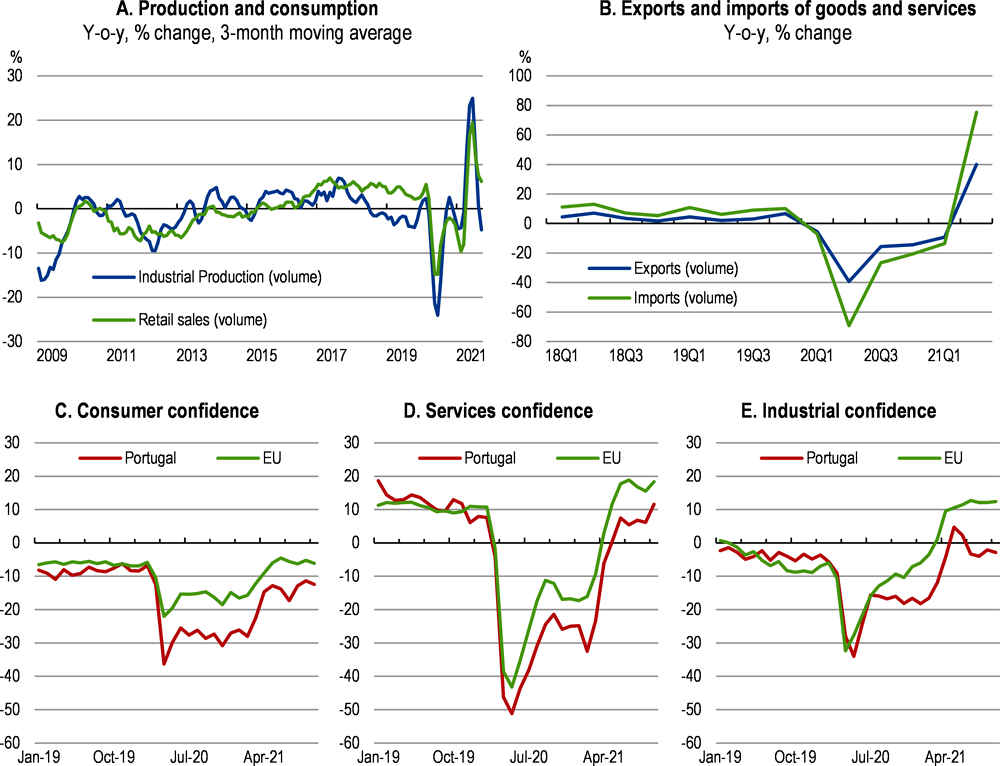

Portugal was among the OECD economies most strongly hit by the pandemic, but has been recovering fast since mid-2021 (Figure 1.8). A deep decline in GDP followed lockdown measures imposed to slow the spread of the virus in March 2020, which were lifted in mid-2020, and successive containment measures, which were introduced subsequently due to the health situation. Private consumption plunged due to high uncertainty, fear of contagion, and mobility restrictions (Figure 1.8, Panel B). Activity has been constantly supported by policy measures and rebounded markedly each time when diverse restrictive measures were lifted. Nonetheless, the recovery has been uneven, as the hit was particularly strong in the tourism, hospitality and transport sectors that have a relatively large weight in the economy. By contrast, activity in construction and manufacturing remained strong in 2020. As the health situation improved and most of the restrictions were removed, activity in the services sector has gained momentum, associated with strong household consumption since the second quarter of 2021.

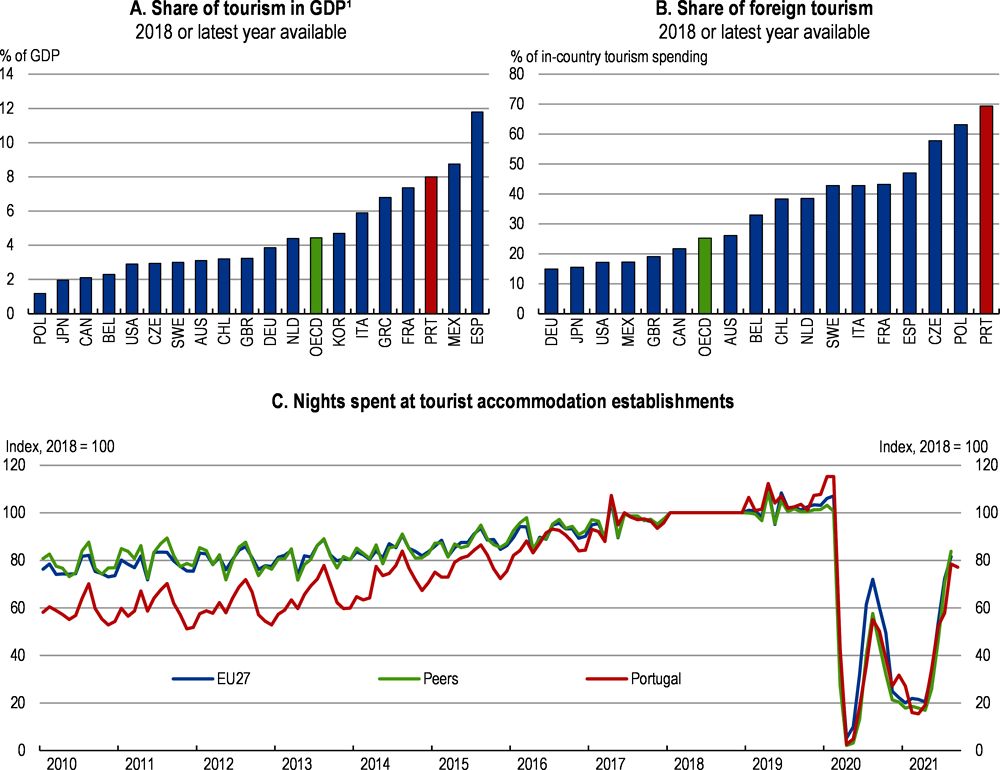

Portugal’s economy has been particularly vulnerable to the pandemic due to its high reliance on international tourism (Figure 1.9). Tourism has been one of the most severely hit sectors, with a 58% decline in travel and tourism exports in 2020. The share of tourism in total export declined from 19.5% in 2019 to 10.4% in 2020. Since March 2020, hotels, restaurants and touristic attractions have operated with restricted capacity due to health protocols and international aviation restrictions. While most of mobility restrictions have been removed, the tourism sector has recovered strongly over the past months (Figure 1.9). The total revenue in the sector in the first nine months of 2021 has already exceeded that for the whole year of 2020. Despite this strong recovery, activity in the tourism sector still remains well below pre-crisis levels.

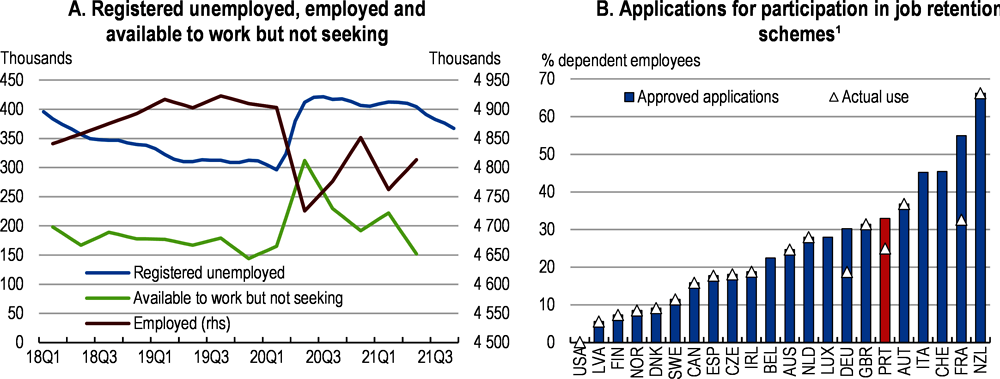

Public support weathered the impact of the crisis on the labour market. In 2020, unemployment rose moderately compared with the decline in economic activity as nearly 15% of the labour force benefited from various temporary forms of state support at the height of the crisis (Bank of Portugal, 2020a), including notably the job retention schemes (Box 1.1). Both employment and, to a lesser degree, labour force participation have risen along with the economic recovery (Figure 1.10). The unemployment rate has declined to 6.3% (those aged 15-74) as of the third quarter of 2021, from 8.2% at its peak in 2020. Nonetheless, the recovery in employment has been uneven across workers, as employment among previously temporary or part-time workers and those with lower educational attainment remains well below pre-crisis levels.

A large number of firms have faced financial stress, which has been mitigated by policy measures. Survey data suggest that half of the firms were benefiting from some public support at the end of 2020 (Bank of Portugal/INE, 2020, Bank of Portugal, 2020c). Government liquidity measures, including a moratorium on credit instalment payments and credit lines with public guarantees, and the European Central Bank’s accommodative monetary policy have contributed to maintaining credit, preventing a surge in insolvencies and credit defaults. Business investment dropped during the first lockdown and has been weighed down by supply constraints as well as liquidity and solvency concerns in some firms (Bank of Portugal, 2021c). Nonetheless, public and residential investment have remained strong, supported by EU funds, and overall gross fixed capital formation has already surpassed pre-crisis levels.

Both exports and imports declined strongly in 2020 due to the crisis and have recovered unevenly (Figure 1.11). Imports have rebounded fast over the past quarters as domestic demand has gained momentum, while the recovery of exports has been comparatively limited, leading to a deterioration of the current account balance. In 2020, exports of goods and services contracted sharply (-20.5% in nominal terms), which was even more pronounced for tourism (-57.8%). Brexit also weighs on exports and investment, as the UK was the destination of around 10% of exports, the largest market for travel exports (around 18% of total), and the fifth largest source of foreign direct investment before the pandemic. In fact, the contraction of exports to the UK was stronger than that of overall exports in 2020 (total goods and services declined by 34.4% and tourism by 63.4%).

After a steep decline of 8.4% in 2020, GDP is projected to strongly rebound in 2021 and 2022 following the lift of restriction measures and the rollout of vaccination as well as the absorption of EU funds (Table 1.1). Despite still high uncertainty and corporate debt, investment will be solid, supported by the Next Generation EU programme. Consumers spending, which rebounded recently following the removal of mobility restrictions, will remain robust. Exports, still subdued, will be slow to recover fully, reaching the pre-crisis level only at the beginning of 2023, as tourism is expected to continue to be affected by mobility restrictions across borders. As job support measures will have been phased out, unemployment can increase in particular among workers with precarious jobs and low wage levels who have higher propensity to consume. In the absence of additional policy measures, the end of moratoria in debt repayments will likely trigger an increase in credit defaults and liquidations.

Inflation turned negative in 2020, but has been rising relatively strongly over the past months, standing at 1.8% in October 2021, essentially driven by high energy prices. Production costs have risen strongly largely due to energy prices and supply constraints as the industrial production prices index rose 13.3% year-on-year in September 2021. However, the current rise in production costs is not expected to fuel underlying price pressures so far, given still sizeable slack in the economy (Table 1.1). Since October 2021, the government has introduced a number of measures to cushion the negative effects from rising energy prices, such as fuel subsidies for households and for public transport operators as well as a control of fuel marketing margins.

Risks to the outlook are significant. Like in all other OECD countries, the evolution of the pandemic remains the major factor that will determine future economic performance and is difficult to predict. Downside risks include the spread of new variants of the virus and low effectiveness of vaccines that could lead to new containment measures and low confidence. The current rise in energy prices can be more protracted than expected, which would weigh on production and consumption in spite of the relief measures introduced recently by the government. A rapid implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Plan will be key to sustain a fast recovery. A stronger rebound in tourism could accelerate GDP growth, notably by improving employment prospects for vulnerable workers affected by the crisis. In contrast, the recovery of tourism can be even slower than expected, if the pandemic affects tourists’ preferences and confidence permanently.

Maintaining Portugal’s comparative advantage in tourism is crucial to sustain the recovery in the medium run. A set of targeted measures (i.e. earmarked credit lines, VAT vouchers, creation of a “Clean and Safe” label among other measures to ensure tourists’ safety) rightly aimed at protecting companies and jobs in the sector so they can operate after the lifting of containment measures. So far, the crisis did not seem to have affected Portugal's productive capacity as a tourist destination. The number of jobs in hospitality and restaurants in 2020 declined by 8.9%, which only moderately recovered in 2021, but the number of touristic accommodation establishments, travel agencies and touristic animation enterprises registered in the national tourism registration system has increased compared with 2019. In the longer run, fully reaping the benefits of the recovery of tourism will require maintaining strong international competitiveness, to intensify linkages with other sectors in the economy, while ensuring its development all over the territory. A coherent and integrated national plan for the development of tourism can help to achieve these objectives. In this respect, the government launched a EUR 6 billion plan to reactivate tourism in May 2021.

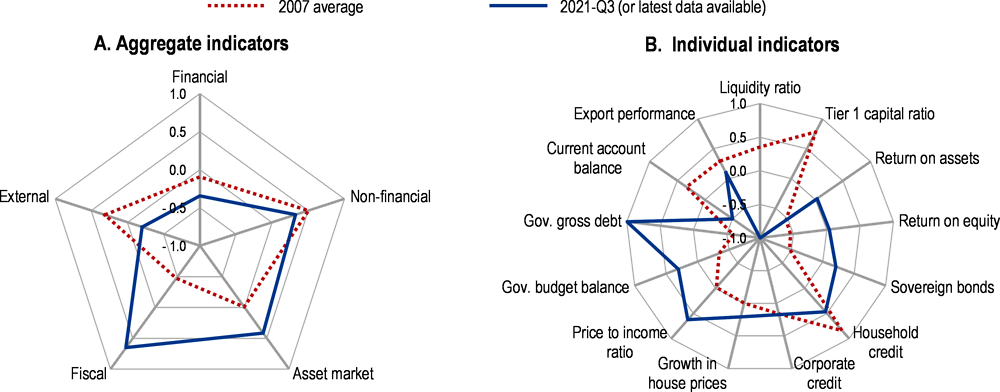

Indicators of macro-financial stability suggest Portugal’s economy is more resilient than in past major crises (Figure 1.12). However, the escalation of the health crisis could trigger tail events that would affect economic prospects significantly (Table 1.2). Resilience of Portuguese firms, which are in relatively large proportions very small and undercapitalised, and thus more vulnerable to shocks, is another source of uncertainty. A higher than projected rise in insolvencies could dent economic prospects, thus the capacity of public policies to provide adequate support is essential.

Policy support should continue, but adapt to the evolution of the pandemic

While relatively weaker than in the OECD on average, public support was sizeable and mitigated the negative impact of the pandemic on the economy (IMF, 2021). Direct aid through subsidies or tax cuts was substantially lower than in other EU countries, but state guarantees on loans were massively used (ESRB, 2021). Fiscal support should remain in place until the recovery is firmly underway. Job retention schemes, benefit payments to the self-employed, income support for workers caring for children and tax deferrals should continue as far as restrictions are in place. Loan and guarantee programmes should also be pursued for firms affected by regulatory restrictions to ensure they can restart activity when possible.

As the pandemic evolves, the authorities should regularly reassess and adapt measures to support the economy, finding the right balance between protecting firms and workers and encouraging the liquidation of unviable activities. Furthermore, a durable recovery will require improving productivity growth and reducing disparities in economic performance, not least by boosting the digital transformation and addressing the digital divide (Chapter 2). Structural reforms recommended in this Survey can have a substantial positive impact in the medium to long term. Box 1.2 presents estimates of the impact of a selection of reforms discussed in this Survey on growth and fiscal balance.

The tables below present the growth and fiscal impacts of some key structural reforms proposed in this Survey. These estimates are illustrative. The impact on GDP per capita is estimated using historical relationships between reforms and growth in OECD countries. The fiscal impacts presented in Table 1.4 do not take into account indirect effects, such as those induced by the positive impact of the reforms on growth and public revenues.

Supporting distressed firms

Despite a stronger position of firms when compared to the previous crisis, the small size, low capitalisation, and high indebtedness of businesses suggest high insolvency and bankruptcy risks in Portugal following the phasing out of public support to businesses and the end of the moratoria on bank credit payments and insolvencies in 2021. According to recent estimates of the Bank of Portugal, moratoria covered around 28.5% of firms’ loans (around EUR 21.5 billion) as of end August 2021, just before the end of the moratoria (Bank of Portugal, 2021b). To limit a surge in default, support measures are needed. First, Linha de Apoio à Recuperação Económica (LARE) Retomar was launched in September 2021, as a new support measure for economically viable firms operating in the most affected sectors, which aims to provide an additional relief of debt repayment, by restructuring credit operations in moratorium, introducing a new principal grace period and maturity extension. In addition, Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan includes measures to support firms’ recapitalisation, aiming at restoring firms’ financial autonomy and fostering productive investment (see below).

Support measures should target viable firms in sectors more affected by the containment measures. Banks’ expertise could be used to identify firms to which they are exposed and that are still viable, but have liquidity constraints. The government could develop a common framework to assess the viability of firms and complementary measures needed to address the short-term solvency of viable firms. This could be for example delaying the main payments of loans guaranteed by the State, agreeing on some restructuring of unpaid social contributions, or increasing the maturity of State-guaranteed loans, in line with the prudential framework. However, this last measure would require renegotiating the conditions of this State aid measure with the European Commission. When doing so, it is crucial not to delay debt restructuring as this could weigh on bank lending capacity (see below).

A number of policy options promoting equity and quasi-equity financing can flatten the curve of crisis-related insolvencies and lessen the risk of debt-overhang (Demmou and al., 2021). Portugal has already a number of non-debt funding instruments in place, such as fiscal incentives for firms to undertake equity-type capital injections, a regulatory framework for Investment Funds and a mechanism of conversion of loans to equity, but their scope has been modest. More needs to be done to expand the availability of non-debt instruments. The package of financial instruments to support firms’ capitalisation and investment envisaged under the Recovery and Resilience Plan includes the development of the National Promotional Bank, Banco de Fomento. It manages a total amount of EUR 1.3 billion that can be invested in viable firms in the form of equity and quasi-equity. The package under the Plan also includes a reform of the capital market for promoting the capitalisation of non-financial companies with particular emphasis on investment firms, and envisages regulatory and administrative simplification and capitalisation incentives such as deduction for retained and reinvested earnings, to be completed by 2025.

The creation of a public equity fund, like in Spain, can contribute to stimulating non-debt funding. Its effectiveness would depend on developing a credible exit strategy of public funds and monitoring the associated contingent liabilities (OECD, 2020b). State contingent loans for which repayments are conditioned on future returns, like in France with the “participative loans”, can help small firms that do not have access to equity markets to recapitalise. Similar to equity, such loans are subordinated to other debts and their returns are linked to profits. They have a relatively long maturity, and can include State guarantees and higher interest rates to attract private financing. In Portugal, the possibility to introduce participative loans has been examined by regulators and stakeholders. Converting loans into grants, under a number of conditions, as done in the US or in Germany, is a more direct way to reduce debt of distressed firms. Portugal has already provided non-refundable grants to firms, notably to pay rents, which is welcome. Nevertheless, room to expand the scope of such measures is small due to their high cost and the limited fiscal space.

Stimulating activity through productive investment

The COVID-19 pandemic jeopardises the recovery of investment by weighing on firms’ profitability and capacity to invest. In 2020, private investment dropped by around 16%. Before the pandemic, private investment was already relatively low, undermining the adoption of new technologies, especially in SMEs (see Chapter 2). The deterioration of economic conditions risks deepening this performance gap by undermining capital acquisition. Foreign direct investment flows can be affected negatively, as FDI prospects are weak in some sectors, including the automotive and the aeronautic sectors (EY, 2020). The pandemic has put a drag on firm creation in 2020, which was subsequently reversed but has not reached to pre-crisis levels yet. Weak firm dynamics could have long-lasting effects on growth potential, as new entrants tend to bring innovation, use more intangible capital and increase market contestability (Calvino, Criscuolo and Menon, 2016).

Policies should sustain investment, especially in new firms. A key issue is investment funding. Weakening balance sheets, increasing financing constraints and high uncertainty have complicated access to finance, especially for SMEs that lack collateral and for intangible investment (Demmou and al., 2021). Despite extensive public support to credit supply (i.e. state guarantees, see Box 1.1), financing conditions have worsened for higher risk companies. Credit standards tightened in response to the economic outlook, a deterioration in borrowers’ creditworthiness and a decline in risk tolerance (Bank of Portugal, 2020b).Banks – the main external financing sources for businesses – apply tight collateral requirements, restricting the supply of unsecured loans. Under these circumstances, firms benefited from publicly guaranteed credit lines. Between March 2020 and March 2021, the stock of loans of companies that resorted to publicly guaranteed credit lines increased significantly. Overall credit standards have been eased since early 2021 and currently standing close to pre-crisis levels (Bank of Portugal, 2021d).

Policies that improve the availability of long-term market-based financing can support the recovery of investment. As detailed in Chapter 2, alternatives to bank financing are missing in Portugal, which has been a barrier to access to finance already before the crisis, especially for small innovative firms (European Investment Bank, 2019). Options to diversify financing sources include introducing schemes for equity-type capital injections directed to SMEs, as equity markets for SMEs are lacking. Other possible measures include the establishment of funds as done for instance in France with the “Fonds de renforcement des PME” or the BPI France Entreprises or the setup of convertible bonds as done in the UK. Developing a special framework for private bond placements by small companies following successful examples in Europe could also be envisaged (e.g. the mini-bond market in Italy). Initiatives to improve awareness on equity instruments among entrepreneurs and incentives for investors can accelerate the development of equity finance. Finally, reducing costs and streamlining listing requirements can facilitate access to equity markets for smaller firms, as stressed in the 2020 OECD Capital Market review (OECD, 2020c). Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan envisages reforms to develop capital markets, including the revision of the legal framework for collective investment undertakings and of incentives to capitalisation.

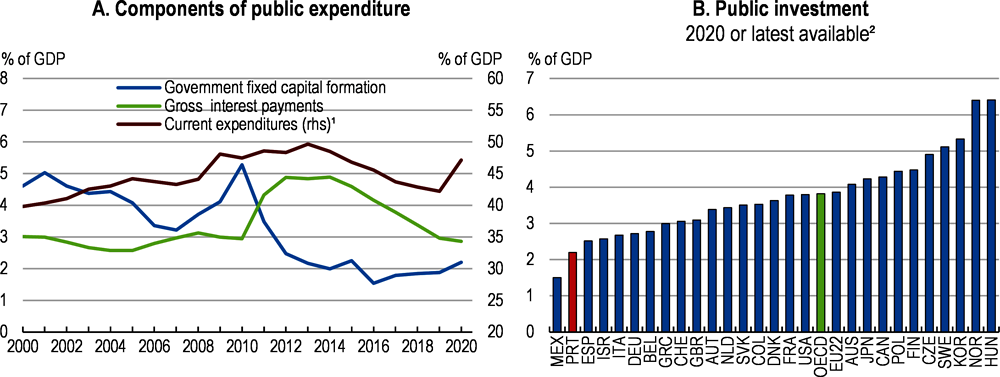

Public investment in growth-enhancing areas, such as digitalisation, environment, education and health care, can boost productivity from current low level and inclusiveness (see Figure 1.4, Chapter 2). However, public investment, at around 2% of GDP, was among the lowest in the OECD in 2019 and in 2020, despite an increase in response to the pandemic (Figure 1.13). Over the past decade, subdued public investment has been part of the fiscal consolidation strategy that focused on the headline deficit with only limited structural improvement (Weise, 2020).

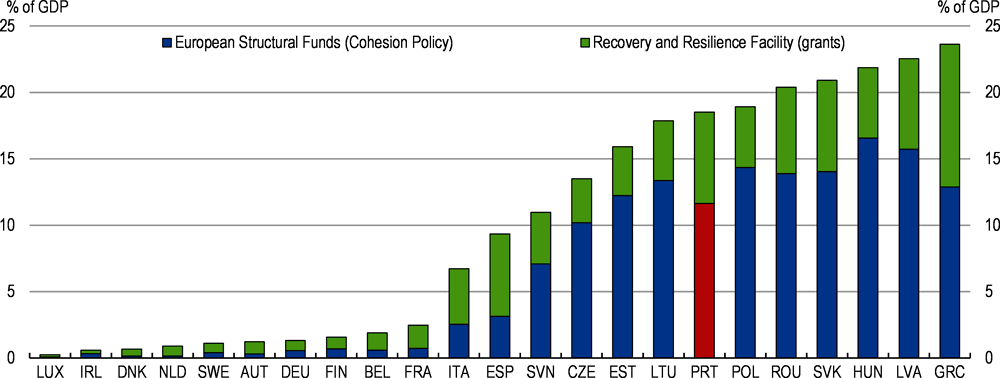

EU funds will help to increase public investment. Portugal will receive around EUR 61 billion over 2021-29, in particular from the Recovery and Resilience Facility and the Cohesion Policy funds (Figure 1.14). While Portugal has been successful in using EU funding so far and has experience with financial assistance programmes, absorption might be slow due to hurdles in designing, approving and implementing programmes. Portugal has already received EUR 2.2 billion (1% of GDP) in pre-funding and is expected to absorb 1.2 billion in 2021. Portugal will have to develop administrative capacities to accelerate the management of the funds. Reducing red tape and streamlining administrative processes in the public procurement system, while ensuring high levels of transparency and accountability to prevent the risks of fraud, would also help to speed up the execution of planned investment.

Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan presents the main orientations for the use of the Next Generation EU funds. The main areas for investment and reforms coincide with those highlighted in past and present Surveys (Box 1.3). In line with EU guidelines, the plan dedicates 38% of the budget to measures addressing environmental challenges and 22% contributing to the digitalisation of the economy. The plan aims at strengthening economic, social and territorial resilience by reducing social vulnerabilities, raising the national productive potential and ensuring competitive and cohesive territory. The implementation of the plan is underpinned by a specifically designed governance, the structure of which is considered to be adequate (European Commission, 2021a). It consists of a coordination body chaired by the Prime Minister (the Inter-ministerial Commission), monitoring mechanisms associating also relevant stakeholders outside the government, and an audit and control mechanism.

Portugal will have to execute a significantly larger amount of EU funds over the next years than in the past, representing both an opportunity and challenge in terms of programming, complementarity of instruments, management capacity, audit responsibility and successful and impactful execution (European Commission, 2021a). Also, the implementation of the plan is supposed to be coordinated with that of the Partnership Agreements for 2021-27 (for the Cohesion Policy) under a broader economic and social strategy ‘Estratégia Portugal 2030’. Therefore, the coordination between the monitoring mechanisms for the plan, the Development and Cohesion Agency in charge of all EU funds, and the Ministry of Finance in charge of formal interactions with the European Commission will be crucial. The launch of a platform (i.e. the “More Transparency Portal”) that aims at improving the transparency of the European funds’ execution process by providing clear and relevant information to citizens in April 2021 is a welcome step. The effective implementation of the plan should ensure value for money and reduce the risk of fraud. It will be also important to keep monitoring the costs and benefits of projects, favour those that have the highest economic and social returns, and to ensure funds will finance projects that would not have been carried out in the absence of public co-funding.

The Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan is part of the Next Generation EU initiative and integrated in the Portugal 2030 Strategy approved in early 2021. The Plan is structured around three main dimensions: resilience, climate transition and digital transition. It includes 20 main components, some of which are covered in this Survey.

Measures in the resilience section include

Health, housing and social policies targeting vulnerable people. Objectives include expanding the healthcare network in low-density regions, completing the Mental Health reform, and providing decent housing to at least 26 000 households.

Investment and innovation policies aiming at raising R&D spending (2% of GDP by 2025 and 3% in 2030), expanding export capacity of Portuguese firms to 50% of GDP by 2027 and improving its value added content.

Measures to reinforce the responsiveness of the education and training system, to foster the creation of permanent jobs and to upskill the adult population.

Investment in transport infrastructure, forest and water management for a more competitive and cohesive territory.

Measures related to the climate transition (38% of the RRP budget), with the stimulation of research, innovation and application of more efficient technologies, intend to promote better use of energy resources and enhance the development of economic sectors around the production of renewable energies. They should contribute to achieving Portugal’s objective to reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

Measures for the digital transition (22% of the RRP budget) focus on digitalisation in the public sector, including the healthcare system, culture, general digital public service delivery, interoperability between platforms and systems, cybersecurity, tax and social security administration and the justice system. The Digital School programme aims at equipping all students and teachers with laptops, improving connectivity and developing curriculums that integrate digital tools and the Workers Digital Skilling dimension providing adult population with digital skills from basic to proficient levels. Measures to promote digital adoption in companies, especially SMEs, account for around 20% of the amount allocated to the digital dimension.

Facilitating the restructuring of viable firms

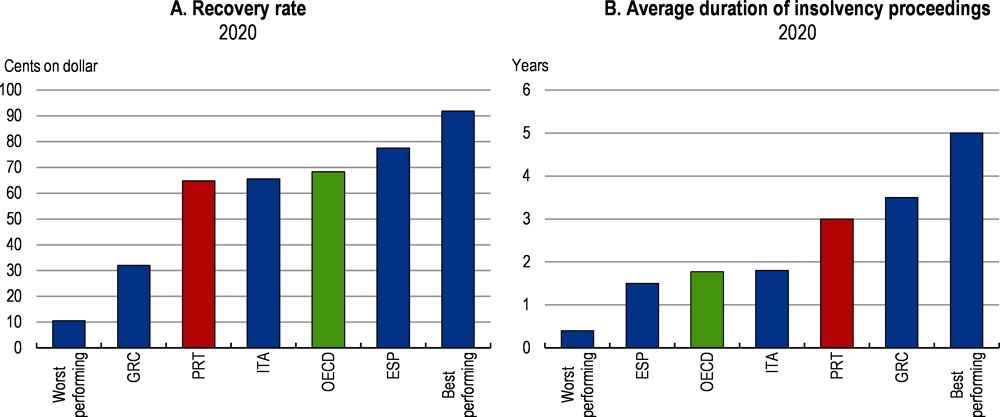

The insolvency regime and the judicial system will have to adapt to ensure a rise in insolvencies will not excessively increase delays in proceedings nor lead to the exit of viable firms. Lengthy insolvency procedures reduce the chance of survival and lower the liquidation value of failing firms (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018). This could induce a fall in debt recovery from relatively low levels (Figure 1.15, Panel A), increasing credit risks and further deteriorating financing conditions. At the same time, speeding up procedures when courts get congested decreases efficiency and can lead to the liquidation of viable firms (Iverson, 2018).

While the average time needed to resolve civil and commercial cases has continued to decline and is now close to the EU average, the estimated duration of insolvency proceedings remains well above the OECD average (Figure 1.15, Panel B). The backlog of old insolvency cases remains high (64% of cases closed in 2020 were pending for over 5 years) and is likely to increase should the number of cases surge as expected. Improving judiciary efficiency is key to shortening procedures, while improving the quality of court decisions. In line with past OECD recommendations, measures have been put in place (i.e. the Tribunal+ project, Table 1.5), but their benefit might take time to materialise. In the medium run, resources in the court system need to increase, for instance by adding new temporary judges on insolvency procedures or by accelerating the hiring of judges’ assistants as envisaged in the Recovery and Resilience Plan. Increasing the managerial autonomy of the courts can contribute to a better allocation of resources. Effort should also concentrate on developing digital tools for the workload assessment further. Plans to improve electronic processing of procedures are welcome (Table 1.5). A single platform for case management, integrating both judicial and alternative mechanisms for dispute resolution, can support effective triage of cases and help with court congestion (OECD, 2020d).

The use of out-of-court procedures should be encouraged to prevent court congestion and fasten procedures. The insolvency framework has improved significantly in that respect since the global financial crisis, with the introduction of early warning mechanisms and pre-insolvency procedures for restructuring (Jin and Amaral-Garcia, 2019). However, only around 200 firms were restructured under out-of-court mechanisms in 2018-19. A new recovery process for firms affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (PEVE) and a public system of alternative dispute resolution for natural persons (SISPACSE) have been introduced. The Recovery and Resilience Plan foresees further reform of the insolvency regime, notably to simplify procedures. Judicial staff should be encouraged to orient users to the out-of-court mechanisms, when appropriate, as done in the UK or Germany. Establishing a unique judicial portal for businesses that provides legal information and advice can increase awareness of available options for restructuring (OECD, 2020d). Finally, as recommended in previous Economic Surveys, financially attractive out-of-court schemes for firm liquidation should be introduced and exit costs on entrepreneurs reduced to create the right entrepreneurial environment of a “second chance” (Table 1.5).

Adapting job retention measures

Job retention measures have preserved employment relationships and sustained household income in 2020. They have been reinforced in response to the third wave of the virus, following the re-introduction of lockdown measures at the beginning of 2021. They rightly target most affected firms, and include features that limit the uptake by vulnerable ones. For instance, access to the “simplified lay-off” scheme has been restricted to firms directly or indirectly affected by lockdown restrictions and conditioned to the maintenance of employment for at least two months.

As the economic situation improves, firms’ contribution to the costs of hours not worked (currently around 20%) should gradually increase to strengthen incentives to use subsidies for jobs that are viable. Besides, short-time work benefits are significantly more generous than unemployment benefits. The replacement rate should be reduced, as it may discourage workers to look for another job, even when job survival is uncertain (OECD, 2020e). In addition, the mobility of workers from subsidised to unsubsidised jobs can be promoted by encouraging workers on short-time work to register with the public employment services. This would allow workers at risk of displacement to benefit from their services, supporting their career progression.

The short-time work scheme also included incentives for employers to provide training to workers with reduced working hours. Unfortunately, the uptake has been low, reaching only 0.6% of the firms that participated in the simplified lay-off scheme by the end of October 2021, with a similar result for the other job retention scheme. While this is partly due to the difficulty of providing vocational training during lockdowns, this also reflects the low capacity of firms, especially SMEs, to provide training (Chapter 2). Effort to promote training should strengthen, targeting workers more at risk of losing their jobs.

Supporting job seekers

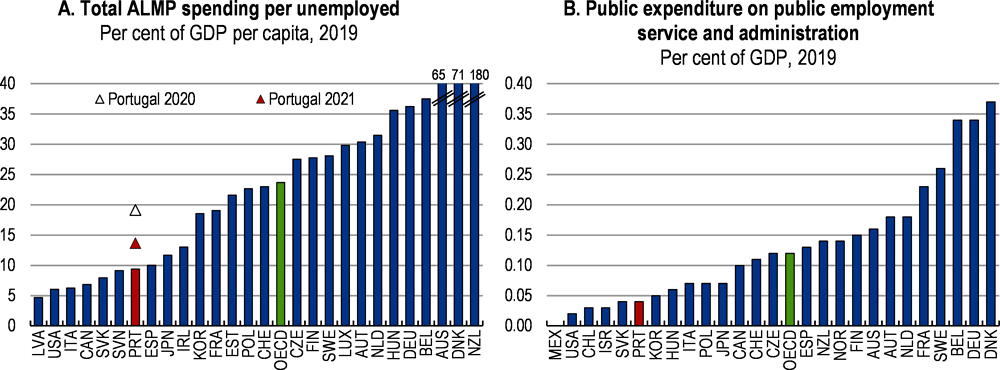

Public employment services need to adapt to new circumstances surrounding unemployment and inactivity. They will play a central role in the reallocation of workers across industries, firms and occupations, as some sectors – including tourism – will likely continue to operate below pre-crisis levels over the next few years. Fostering labour market participation, which stands below the OECD average for men, will also be paramount to sustain long-term growth in a context of rapid population ageing. Portugal has put a stronger emphasis on active labour market policies (ALMPs) before the pandemic as recommended in past Economic Surveys (OECD, 2017a). In particular, direct and indirect support to job creation has contributed to lower unemployment, while training measures (especially those provided for a longer duration) have increased employability of jobseekers (OECD, 2019b; European Commission, 2020a). Following a significant increase since the beginning of the pandemic, spending on active labour market policies per unemployed is still expected to remain below the 2019 OECD average in 2021 (Figure 1.16).

The effectiveness of ALMPs largely relies on the capacity of the public employment services. In Portugal, the share of jobseekers in regular contact with the public employment services is among the lowest in the OECD and only around 35% of jobseekers used their services to find a job in 2018 (European Commission, 2020a). Resources in public employment services have been relatively low (see Figure 1.16, Panel B). They should be targeted at improving job search support and counselling on training, which would be most useful to address the expected increase in unemployment. Public employment service staff workload is heavy and varies across regions. This undermines the implementation of a case management system with individualised guidance (Düll et al., 2018). Raising the number of career managers would improve the effectiveness of the personal employment plans, particularly in regions with higher unemployment or a higher share of jobs potentially at risk (OECD, 2017a).

The digitalisation of public employment services needs to accelerate, as it can free up resources and thus support caseworkers in coping with potentially fast increasing number of clients in the future (OECD, 2020f). During the COVID-19 crisis, the use of online tools increased significantly in response to containment measures, which gives good momentum to further structural transformations. Refining statistical profiling tools can improve the targeting of activities in public employment services (Desiere, Langenbucher and Struyven, 2019). Automated matching can minimise the need for caseworker intervention. Finally, automation of procedures, such as registering jobseekers, processing unemployment insurance benefits and the short-time working scheme, via exchange of data across administrations, like in Estonia, could achieve large efficiency gains.

Training accounts for a large share of spending on ALMPs. This is welcome as the lack of skills is one of the main barriers to employment in Portugal (Düll et al., 2018). Training should adapt skills needed for the fast changing labour market and the digital transformation (see Chapter 2). Programmes, such as the Digital Guarantee that aims at providing all jobseekers with digital training adapted to their level of qualification and skills profile by 2023, are steps in the right direction.

Employment prospects have dramatically worsened for the youth, who already faced higher rates of unemployment and underemployment before the pandemic (Figure 1.17). The capacity of public employment services to reach out to the youth needs to improve, in particular to those who do not receive unemployment or social assistance and have fewer incentives to register with public employment services (ILO, 2019). Engaging young people, especially the most disadvantaged ones requires specific strategies. For instance, experiences from other EU countries, such as Germany, Greece and Hungary, show that the introduction of outreach services, such as job fairs organised in youth centres, or at the premises of training centres, can be successful in enhancing youth engagement with public employment services (ILO, 2019). Similarly, campaigns using social media and new technology used by young people can be effective (OECD, 2017a). Portugal initiated an outreach strategy in 2018, with various channels of communication, but the scope and the coordination of programmes need to improve (European Commission, 2020b).

Workers with non-standard work contracts, who are poorly covered by conventional social protection and other forms of income smoothing, are likely to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic (ILO, 2020). Portugal extended access to unemployment benefits, which increased the coverage of unemployment insurance and provided temporary support to jobseekers without social protection, but the regulatory framework of unemployment benefits has not yet fully adapted to the specific needs of workers in non-standard forms of employment. Providing income support to jobseekers, especially to those with short or irregular employment history, can limit poverty risks and improve the quality of matching on the labour market, as jobseekers can devote more time to find a job that match their competences (Wulfgram and Fervers, 2013; Tatsiramos, 2009). Portugal should consider easing its strict eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits. For instance, social unemployment benefits are restricted to jobseekers with 6 months employment history and strictly means tested. Employment requirements need to be reduced. Opening unemployment assistance to all jobseekers like in the United Kingdom and Finland would also diminish the risk of large income losses for those with patchy employment history.

Ensuring a sustainable recovery requires preventing the build-up of large macroeconomic vulnerabilities. Sustainable levels of public debt improve the resilience of the economy, by increasing governments’ room of manoeuvre to mobilise fiscal policy during recessions and by reducing the risk of default (Fall and Fournier, 2015). The quality of public finances is also paramount, due to its significant impact on growth (Fournier and Johansson, 2016). Improving the efficiency of public spending and removing distortive taxes can contribute to a growth-friendly debt reduction strategy. In the same vein, a robust financial system is key to ensure effective monetary policy transmission and adequate access to finance, even when economic conditions deteriorate.

Improving the sustainability and the quality of public finances

Risks to public finance sustainability have increased

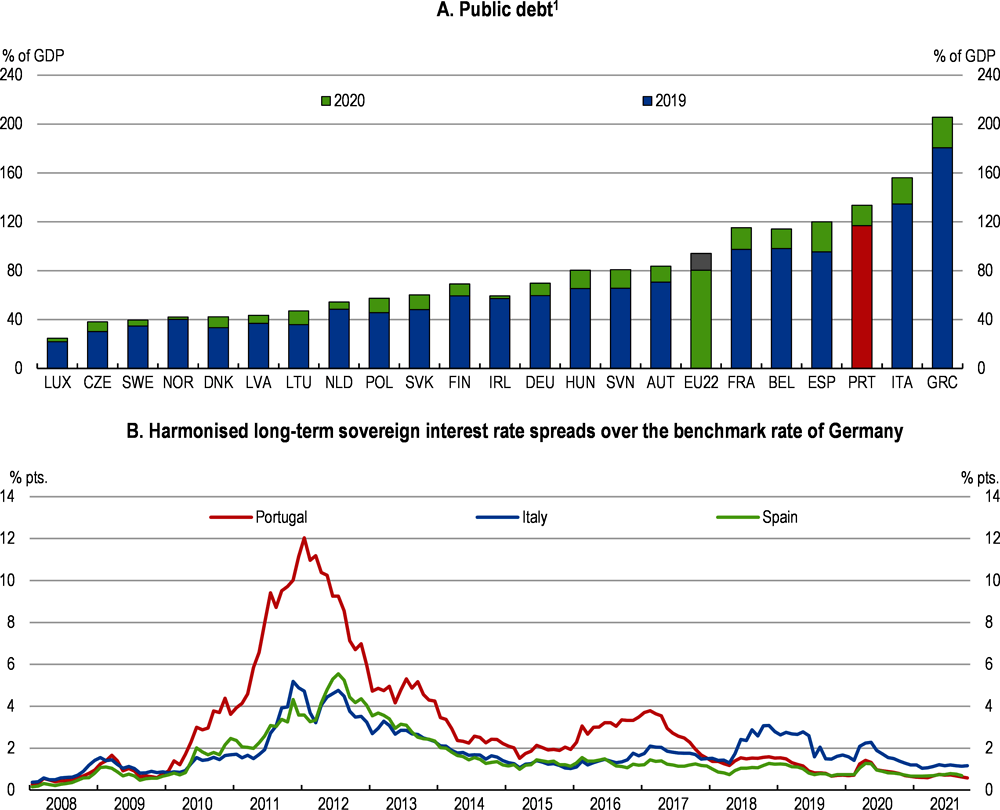

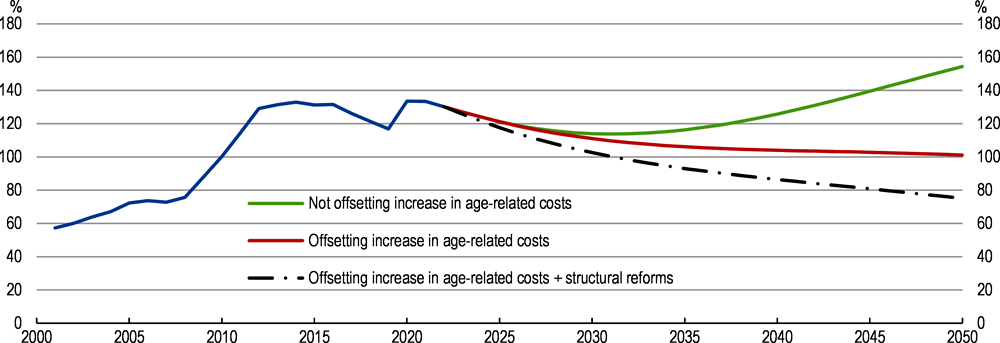

Like in all OECD countries, the COVID-19 crisis has triggered a deterioration of public finances in Portugal, widening the fiscal deficit to 5.8% of GDP in 2020. Public debt increased to the record high level of 135% of GDP (Figure 1.18). Demographic changes will further weigh on public finances in the medium term (European Commission, 2021b). According to OECD projections, primary government expenditure could rise by over 4% of GDP by 2060, with more than half of the increase coming from healthcare (Guillemette and Turner, 2018). Not compensating for higher ageing costs could push the debt level above 150% of GDP by 2050 (Figure 1.19). By contrast, gradual fiscal consolidation combined with policies fostering GDP growth could put public debt on a more sustainable path.

Fiscal risks have expanded due to large increases in contingent liabilities. State guaranteed credit line covered around 12% of loans granted to non-financial corporations in March 2021, totalling EUR 9 billion (Bank of Portugal, 2021a). They were mostly and rightly directed to firms with pre-crisis good creditworthiness in the most affected sectors (Bank of Portugal, 2020b and 2021a). Nevertheless, they have widened off-balance-sheet liabilities and increased State exposure to a potential wave of corporate defaults. The execution of the guarantees can be large if the economic recovery is slow in the hospitality and the transport sectors as projected. In the same vein, capital injections in private companies, like for instance in the national aviation company TAP, could generate high costs, if the supported firms do not recover. Finally, debt rules for local governments have been relaxed temporarily to allow for emergency spending, increasing the risk of over indebtedness in municipalities with pre-existing financial difficulties.

In this context, Portugal should design and make public a credible strategy for debt reduction over the medium term in line with EU fiscal rules. The government plans a progressive decline in the public deficit to below 3% of GDP by 2023 on the back of the economic recovery, the gradual phase out of COVID-19 related measures and the containment of public spending. However, the strategy for cost containment is unclear. In the past, fiscal consolidation happened through cuts in public investment and was not accompanied by a strategic reallocation of spending to priority areas (European Commission, 2020a). The strategy needs to contain escape clauses to avoid that maintaining this deficit objective despite slower growth leads to a pro-cyclical fiscal stance.

In the short run, restricting support measures to sectors and individuals affected by the pandemic would contain fiscal costs. As a matter of principle, firms that cannot fully operate due to containment measures should continue receiving financial support. At the same time, measures, especially capital injections, should target firms with strong business models and good corporate governance to the extent possible. Future state support to private companies should be allocated after a thorough evaluation that involves experts from the private sector. Quasi-equity injections (preferred equity), that provide a senior claim to dividends and assets in case of liquidation, and allow companies to raise funds without diluting control, should be favoured to limit risks to the taxpayer. In addition, to promote the transition to a greener economy, public support should prioritise environmentally sustainable activities, and, when possible, be conditioned to achieving environmental objectives.

In the longer term, limiting future increases in ageing costs will be challenging. Portugal has a public pay-as-you-go earnings related pension scheme and some voluntary private pensions whose share in overall pensions is small. Portugal has already implemented a panel of reforms that improve the sustainability of the pension system, although these reforms came at the cost of shifting most of the burden on future generations (OECD, 2019b). The statutory retirement age increases in line with the evolution of life expectancy and pathways into early retirement have also been restricted. However, the COVID-19 crisis, especially via its impact on the labour market, has reduced social security contributions and can increase the number of older workers eligible to social benefits. The government is considering new financing sources. Other options to reinforce the sustainability of the pension system include the application of the sustainability factor to all pensions and increasing the minimum age for early retirement in line with life expectancy (OECD, 2019c). Increasing progressivity in the public pension system could compensate for induced cuts in low pensions such reforms could generate. Finally, as stressed in the previous Economic Survey and the OECD Pension Review, pathways to early retirement should be eliminated (OECD, 2019c and 2019c). In the healthcare sector, planned measures to improve governance and cost efficiency in hospitals should resume once the pandemic is contained. At the same time, improving access and quality of health and long-term care will require additional public resources (see below).

Moving towards a performance-oriented and transparent budget framework

As stressed in previous Economic Surveys, and to seize the full benefits of available EU funds, improving public spending efficiency is a priority (OECD, 2017a). Doing so requires modernising the budget framework by developing performance budgeting and medium-term planning. Portugal initiated an ambitious reform in 2015, with the Budget Framework Law, but enforcement was delayed, due to governance and expertise issues. In December 2019, only two out of the 21 projects required for the reform had been completed (Tribunal de Contas, 2020). Implementation needs to accelerate, by imposing medium-term targets, closely monitoring progress and allocating adequate human and technical resources.

Portugal should take stock of overall expenditure and reassess its alignment with fiscal objectives and national priorities. Following OECD best practice, a major step would be to establish coordinating entities in each ministry in charge of budget execution, providing them with guidelines for setting programme objectives and assessments of targets (OECD, 2018a). This would free up resources in the Ministry of Finance for the analysis of the financial performance of programmes. Broadening the collection of performance information and developing evaluation capacity is another necessary condition. Performance information is unevenly collected and data are not sufficiently used as a strategic asset to serve citizens (OECD, 2017b; OECD, 2020g). Improving the public administration data ecosystem is one priority of the new Strategy for Innovation and Modernisation of the State and Public Administration 2020-2023. To strengthen transparency on the use of public money and provide information on the quality of public services, the administration operates multiple online portals (i.e. Health Service Transparency Portal, Justice Transparency portal, Municipal Transparency Portal). The integration of information collected by different administrations has improved through the data interoperability platform (OECD, 2019d). Implementation of the Strategy is challenging however, due to a lack of financial and human resources. Large funds under Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan will be allocated to the modernisation projects (Box 1.3), but difficulties in recruiting and retaining skilled professionals risk delaying their implementation.

Medium-term budgeting is central for public finance sustainability as it defines concrete actions a government will take to achieve fiscal objectives by subsectors and policy areas, highlights the budget impact of policy initiatives and provides certainty over fiscal envelopes allocated to ministries. In Portugal, medium-term fiscal plans are not binding, temporarily due to a transitional rule of the Budgetary Framework Law, and deviations from plans within a year were frequent even before the pandemic. Furthermore, estimated impacts of policy decisions on the budget are not detailed. The Fiscal Council, the body in charge of monitoring the adequacy of the budget with national and EU rules, regularly points to the lack of information and incoherence in the budget documentation. The budget administration needs to devote more resources to the provision of timely, transparent and comprehensive information on the draft budget (OECD, 2019e). Following past OECD recommendations, the Fiscal Council will reinforce its analyses of medium-term fiscal projections, including on the sustainability of the social security system, to provide an independent assessment of policy decisions that have a long-term impact on public finances (OECD, 2019e).

Streamlining the tax system and removing distorting tax expenditures

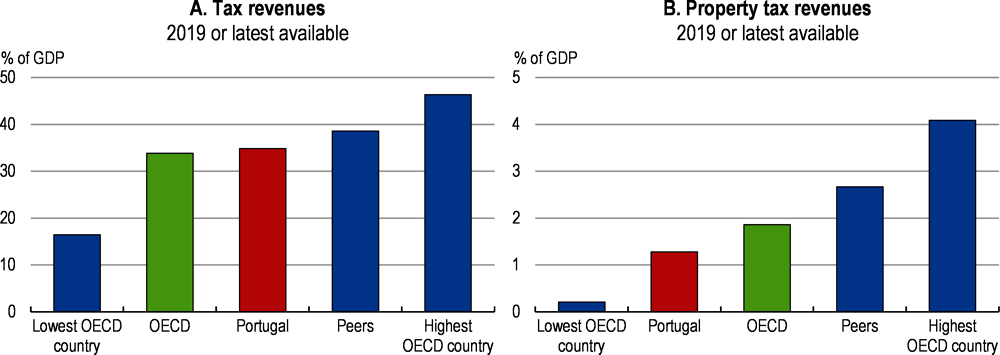

Tax revenue has increased over the past decade and exceeded the OECD average in 2019 (Figure 1.20). Instead of raising tax rates, priority should be given to rebalancing the tax mix. Revising the tax composition can foster economic growth, by reducing taxes most harmful to growth and inclusiveness (Johansson, 2008; Brys et al., 2016). Reductions in the corporate income taxation to stimulate investment should be carefully evaluated and reinforced if found insufficient. In the longer run, size-contingent tax rates should be reviewed, as they may hamper growth of small firms when the recovery will be underway (OECD, 2019b and Chapter 2). There is room to increase taxes on immovable property and inheritance taxes, as they are relatively low by OECD norms (Figure 1.20, OECD, 2021b). Taxes on polluting sources could also increase to reflect their negative impact on the environment (see below). The government plans to revise the rural property and vehicle taxes, but details on the measures are not available yet.

The fiscal consolidation strategy should include a revision of special provisions in the tax system. Tax expenditures accounted for 6.2% of GDP in foregone tax revenues in 2019 and reform to improve their effectiveness should be considered. Among more than 500 existing tax expenditures, 120 do not have a clear objective (Grupo de Trabalho para o Estudo dos Benefícios Fiscais, 2019). While taxpayers have access to online and prefilled tax declaration, paying tax remains lengthier than in most OECD countries and the time taken to prepare and pay taxes has not declined since 2016 (World Bank, 2020). Previous Economic Surveys pointed to the need to simplify the tax system by reducing the use of special provisions (e.g. tax exemptions and special rates), as they make the tax system complex and less transparent (Table 1.6). Tax exemptions and targeted tax cuts have increased to support those most affected by the COVID-19 crisis (see Box 1.1). When the recovery is underway, they should be streamlined and the process of tax simplification should resume.

Further enhancing the stability of the financial system

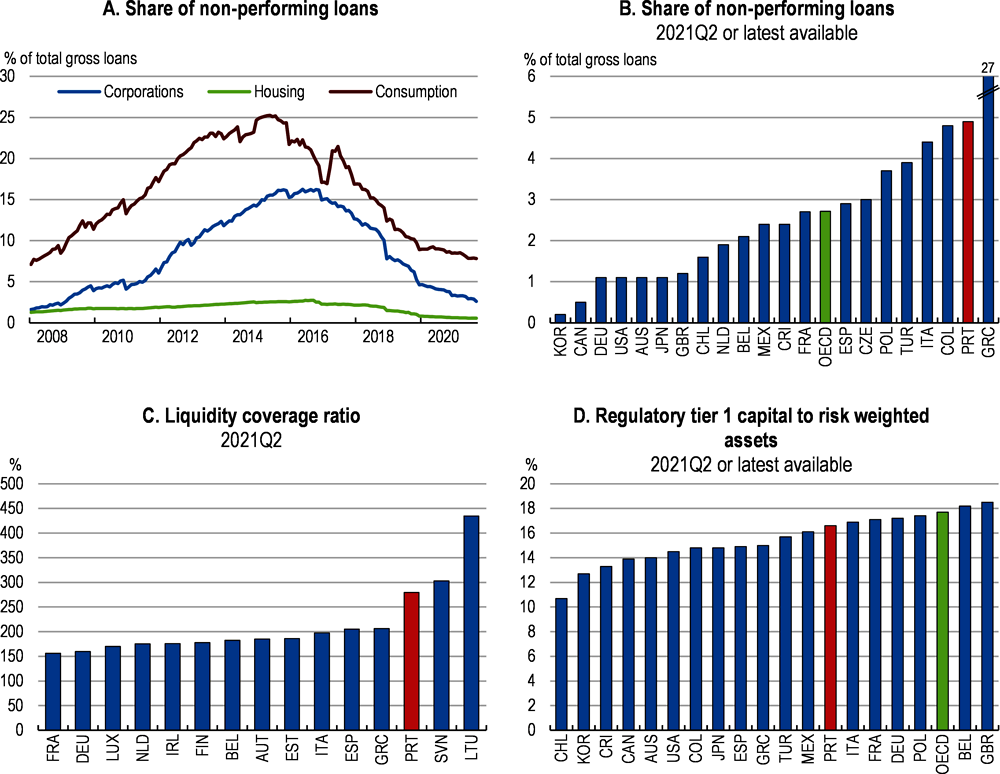

The banking sector entered the coronavirus crisis in a significantly stronger position compared to the last financial crisis (IMF, 2019; OECD, 2019b). Its funding structure has become more stable, with increased deposits and equity financing and less reliance on funding from securities and interbank markets. Capital and liquidity ratios had improved, strengthening banks’ resilience to absorb losses against a deterioration in asset quality (Figure 1.21, Panel C and D). In addition, banks had made significant progress in reducing operational costs and in strengthening their balance sheets, with non-performing loans (NPLs) falling significantly and returning to levels close to 2008 (Figure 1.21, Panel A and B). Policy support to the financial sector following the pandemic has been significant, notably through the relaxation of the use of capital and liquidity buffers, and higher flexibility in accounting rules and computation of regulatory capital. It contributed to containing near-term financial stability risks and supported banks’ lending capacity.

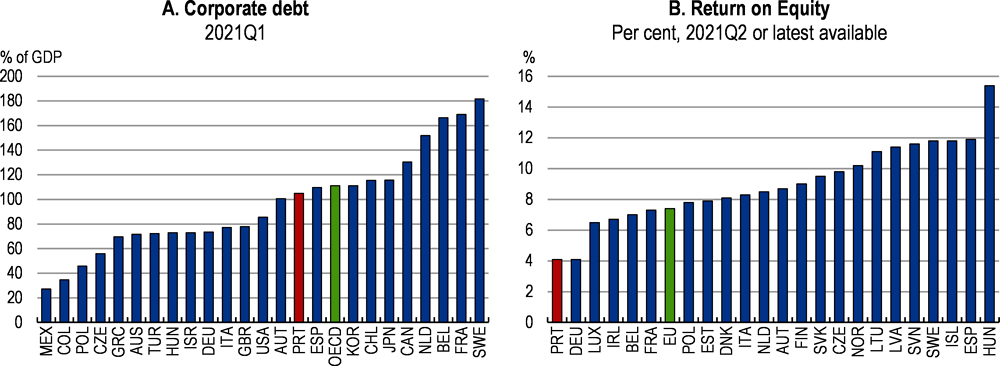

However, remaining vulnerabilities and a challenging environment could test the resilience of the Portuguese banking sector. Firstly, the level of troubled assets remains one of the highest in the OECD (Figure 1.21, Panel B) and risks increasing further in the medium term. Secondly, banks’ profitability has deteriorated and is very low (Figure 1.22, Panel B). In an environment characterised by low interest rates, high competition, and an expected increase in credit losses, Portuguese banks may find it increasingly difficult to restore profitability. This is worrisome, as low profit margins, by limiting banks’ ability to preserve capital during economic turmoil, pose a risk to credit supply. Thirdly, Portuguese banks are exposed to sovereign debt, with government bonds accounting for 16.2% of their assets at the end of 2020 (Bank of Portugal, 2021a). Increases in sovereign spreads, following for instance a deterioration of investors' confidence in the sustainability of Portuguese public finances, could significantly weaken banks’ financial position. At the same time, risks are mitigated by the relatively high share of public debt in banks´ balance sheet classified at amortised cost and immune to change in yields (47%).

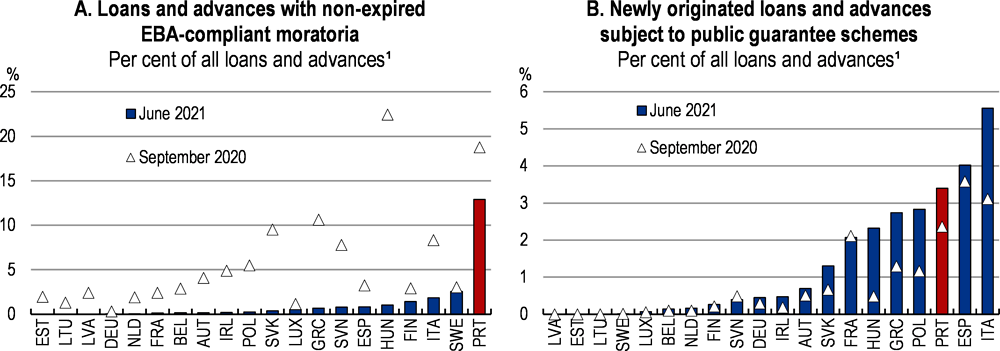

The pandemic has increased financial risks in the corporate sector. Despite deleveraging efforts in the past, corporate debt levels remain relatively high and increased again during the pandemic (Figure 1.22). This is mainly due to loan guarantee schemes and the moratorium on bank loans repayments introduced to prevent liquidity pressures turn into insolvency and the drop in nominal GDP (Bank of Portugal, 2020b). Between March 2020 and March 2021, approximately 30% of new loans to non-financial corporations were issued through state guaranteed credit lines (Bank of Portugal, 2021a). In addition, Portuguese banks had one of the largest shares of loans under moratoria across Europe (Figure 1.23). At the end of August 2021, 28.5% of bank loans to non-financial corporations were under moratoria, but this amount declined substantially with the phase out of the moratorium in September 2021 (Bank of Portugal, 2021b). Estimates of the Bank of Portugal point to a significant increase in vulnerable firms’ debt and excess debt in 2020, but below levels observed during the sovereign debt crisis (Bank of Portugal, 2020b).

In the absence of further policy support, the phase out of support measures, especially of the public moratorium in September 2021, could translate into a sharp increase in default rates on the back of fragile corporate fundamentals and weakening debt-servicing capacities. Banks’ loan loss provisions increased markedly in 2020. Nevertheless, under the Single Supervisory Mechanism, high variability in the expected losses booked across banks that might reflect inadequate provisioning by some banks, in part due to profitability constraints, calls for thorough monitoring (ECB, 2020). Supervisory authorities should develop contingency plans for institutions displaying substantial fragilities (IMF, 2020).

Tackling a surge in credit defaults will require adapting the national strategy to reduce non-performing loans. Such strategy should be diversified, and include measures facilitating the internal management of non-performing loans by banks (on-balance sheet approach) and developing distressed debt markets. Supervisory authorities have reinforced the monitoring of banks’ plans for resolving NPLs and introduced new tools to ensure timely recognition of losses and debt restructuring, in line with those adopted at the EU level. These measures should be strengthened, should they prove insufficient.

Developing distressed debt markets is also paramount. The bid-ask divide (i.e. the gap between the price at which banks are willing to sell non-performing loans and the market price) is a major factor blocking the development of secondary markets for non-performing loans (OECD, 2021c). Measures to improve loan recovery and to raise prospects of efficient repossession of collateral by lenders can contribute to increase market valuations of non-performing assets and reduce the gap. The creation of asset management companies, like done in Spain or Ireland, could also be reconsidered, as it can considerably accelerate the clean-up of banks’ balance sheets (European Commission, 2018a; OECD, 2018b). In the recent past, Portuguese authorities estimated that the potential for a bulk transfer of the non-performing loans in the banking system to an asset management company was low given the characteristics of the underlying assets (OECD, 2019b). This measure would be particularly suitable for addressing a large surge of non-performing assets with relatively high quality of collateral (i.e. linked to loans of relatively large unit sizes or commercial real estate). Establishing an asset management company is complex, especially if backed by public funds. The company should ideally be funded by private investors, including selling banks to avoid conflict with EU State-aid rules and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive. However, public participation would be desirable should a large and widespread deterioration of bank asset quality arise in the aftermath of the pandemic, resulting in a threat to financial stability (OECD, 2021c).

Digitalisation efforts can help to improve the efficiency in the banking sector and to restore margins. Banks will need to make better use of innovative Fintech solutions by underpinning digital delivery models, making service delivery faster and more cost effective, or improving the efficiency of back-office functions. For example, in the UK, collaboration with a Fintech platform reduced the amount of time required to process loan requests for SMEs from 2-4 weeks to 24 hours (KPMG, 2017). The development of regulatory sandboxes by the supervisory authorities are welcome as it can help banks to adopt new financial products and services. Indeed, regulatory sandboxes allow the pilot testing of newly developed technologies within a well-defined space and duration, with safeguards to contain the consequences of failure. The Portugal FinLab initiative offers in-depth consultations to some Fintech innovators with the Portuguese regulatory authorities (see Chapter 2). At the same time, the National Competition Authority points to important entry barriers in the Fintech sector that need to be addressed (Competition Authority, 2021). Finally, banks that have already exhausted cost-saving opportunities and have not yet attained sustainable profitability levels might opt to consolidate branches to exploit potential cost synergies, but the impact on competition needs to be monitored (European Commission, 2020c).

Tackling in-work poverty

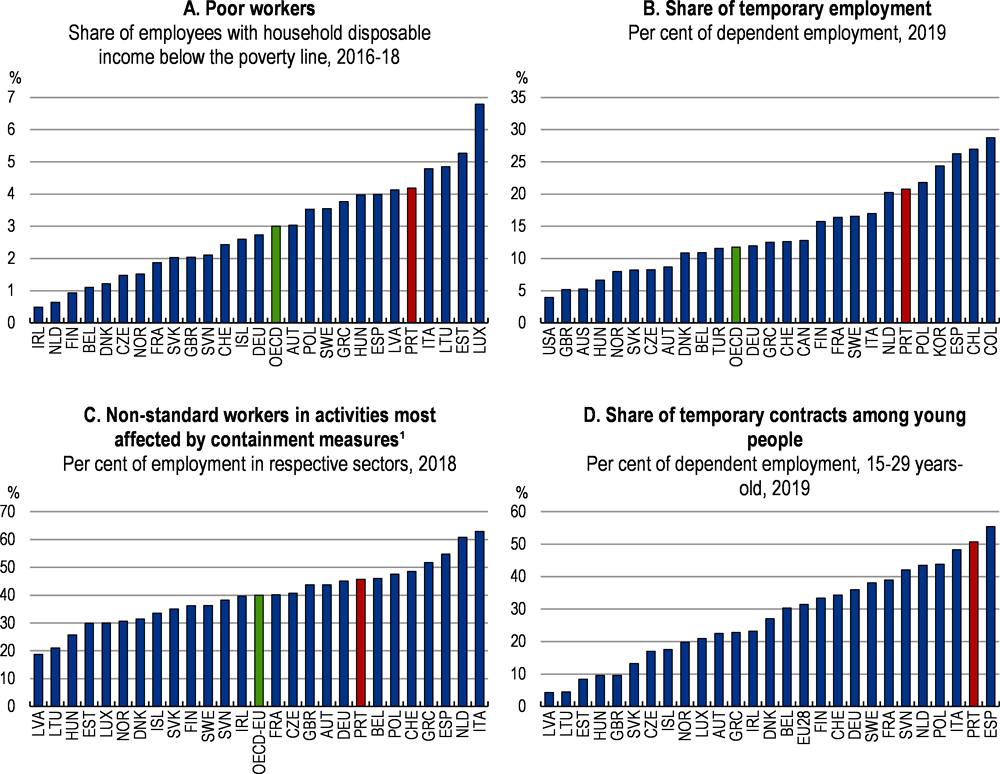

Despite robust economic growth and labour market improvements before the pandemic, in-work poverty has remained high (Figure 1.24, Panel A). Causes for in-work poverty are complex, but the high degree of labour market segmentation plays an important role (OECD, 2009; European Commission, 2019a). In Portugal, workers with non-standard employment, i.e. self-employed workers and those on temporary or part-time contracts, have three times higher income poverty rates than dependent employees (OECD, 2020h). While part-time employment is low, the share of temporary employment as a percentage of dependent employment was among the highest across the OECD in 2019, especially among young workers (Figure 1.24, Panel B and D). Furthermore, non-standard employment is prevalent in sectors heavily hit by the pandemic (Figure 1.24, Panel C). Despite the efforts to protect jobs, economic hardship of workers in these sectors and without standard employment contracts may further accentuate as the pandemic continues.

Tackling labour market segmentation by reducing temporary employment can have beneficial effects on the incidence of in-work poverty (Autor and Houseman, 2005). In line with past recommendations from OECD Economic Surveys (OECD, 2019b; OECD, 2017a), progress has been made in that direction, mostly by discouraging the use of temporary contacts. The 2019 labour market measures reduced the maximum accumulated duration of fixed-term contracts from 3 years to 2 years. The duration of the exemptions of social security contributions for young people obtaining their first job and the long-term unemployed has been extended to promote permanent contracts (European Commission, 2019a). However, the planned introduction of a penalty for employers that use fixed-term contracts excessively has been delayed due to the deterioration of economic conditions. It should be implemented as soon as the recovery is firmly underway.

Strengthening labour inspections is another effective policy tool to prevent abuses in the use of non-standard contracts. Portugal intensified labour inspections during the crisis and increased hiring substantially. By the end of 2020, the number of labour inspectors was for the first time in line with the guideline of the International Labour Organisation reference ratio (ILO, 2006). Resources allocated to the Labour Inspectorate should remain high. Evaluating and reducing administrative burden for inspectors, like done in the Netherlands, the UK, Italy, and Denmark can help to achieve efficiency gains and free up resources in the longer run (Blanc, 2012).

Increasing minimum wages might provide limited support to the large majority of the working poor who cannot find a permanent job. The government aims to increase the monthly minimum wage up to EUR 750 by 2023 (from EUR 665 in 2021). While moderate increases tend to have little impact on employment and can even contribute to stronger productivity growth, sharp and substantial increases can reduce job opportunities for low-skilled workers (OECD, 2018c; Clemens and Wither, 2019). Keeping wages in line with productivity remains essential to avoid pricing out low-skilled workers from the labour market. Evaluating the effects of higher minimum wage on employment and poverty is also key, especially in the context of changing labour market conditions. Setting up a technical independent body in charge of carrying out such evaluations and providing recommendations, as done in Germany and United Kingdom, should be envisaged.

Strengthening social assistance

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated structural challenges of social protection systems and renewed attention to social safety nets (Hyee et al., 2020). Safety net benefits should ensure socially acceptable living standards for households that have no or very low incomes from work, and do not qualify for other benefits. They become an increasingly crucial part of governments’ strategies for stabilising family incomes and relieving acute economic needs.

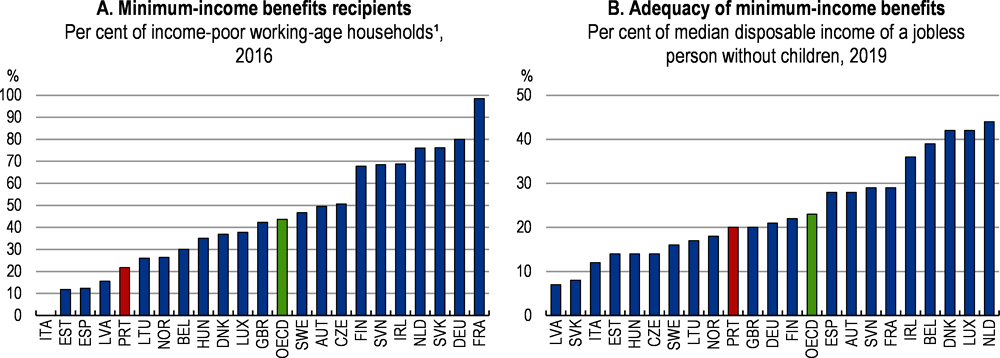

In Portugal, the minimum income benefit (Rendimento Social de Inserção) is low and subject to extensive means testing (Arnold and Farinha Rodrigues, 2015). Topping up recipient’s monthly income, it was set at around EUR 187 for a single person in 2020, well below the poverty threshold. The reference income threshold needs to increase to improve protection against poverty risks. Despite efforts to increase its coverage in the past, the benefit covers only around 20% of poor households, below the OECD average (Figure 1.25). This is due to low entitlement and the complexity of regulations and procedures (European Commission, 2015a). Establishing a one-stop shop application within the public employment system as done in Austria and using data-linking to identify non-applicants can help to improve take-up (OECD, 2020i). A number of other social and means-tested benefits are directed to vulnerable groups (e.g. Complemento Solidário para idosos, Prestação social para a inclusão, Pensões sociais mínimas, Apoio a pessoas com dependência). Reducing the fragmentation of the benefit system and streamlining existing benefits can improve efficiency of social assistance.

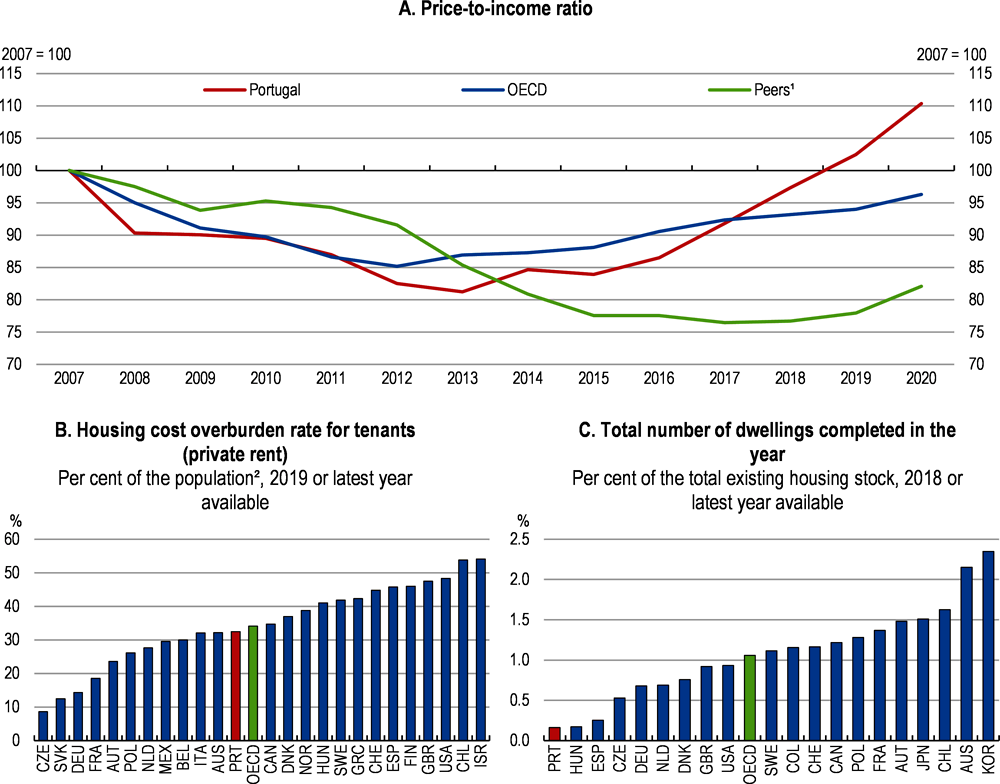

Improving housing affordability

Housing affordability was already a challenge before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis due to strong pressures on housing prices, especially for poor and middle-class households (Figure 1.26). Between 2007 and 2019, housing costs for poor households increased by 28% compared with 7% in the EU on average (Eurostat, 2021). In 2019, around a third of the lowest income tenants in the private market were spending more than 40% of their disposable income on rent (Figure 1.26, Panel B). Despite the government’s effort to protect mortgage-holders and tenants by temporarily suspending rent and mortgage payments during the pandemic, the sudden job and income losses brought by the COVID-19 crisis are bound to increase the pressure on housing affordability further.

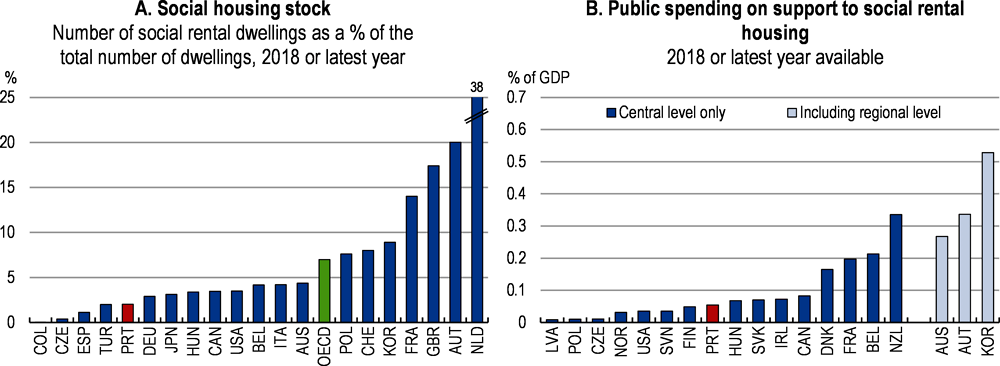

Housing supply has not responded to the increase in housing demand prompted by the low-interest rate environment, high demand for tourist accommodation and policy incentives to foreign residential investment (Figure 1.26, Panel C). Investment in rental housing has remained underdeveloped. The rental market stands at 24% of total dwellings out of which merely 2% represents social housing (Figure 1.27, Panel A). In addition, public spending on social housing has been low, mostly restricted within the Lisbon and Porto areas (Figure 1.27, Panel B). Among policies that support housing affordability for low-income earners, social housing implies lower trade-offs than subsidies and rent control (OECD, 2020j). The government’s plans to increase the social housing stock to 5% of the total by 2026 are thus welcome. Improving technical capacity in municipalities to design adequate housing projects and use available EU funds will be key to achieve this ambitious target.

Burdensome construction procedures can undermine housing supply. The number of procedures and days to get a building permit is higher in Portugal than in the average OECD high-income country (World Bank, 2020). Multiple overlapping procedures are imposed on providers of installation works such as lifts, telecoms, water, sewage and alarms, which could benefit from simplification (European Commission, 2020a). Streamlining procedures can help to reduce the time to receive a building permit and ultimately speed up the pace of housing development. The cost for obtaining a construction permit is also relatively high by OECD standards and could be reduced (OECD, 2021d). Finally, future reform to the property taxation should not aggravate housing affordability issues and aim at increasing tax progressivity.

Adapting long-term care to fast population ageing

The COVID-19 crisis has put the spotlight on the long-term care sector. The pandemic has disproportionately affected elderly people and their care workers. A range of measures have been in place to protect these vulnerable groups, including restricting care home visits, prioritising testing and vaccination of care home residents and staff (OECD/European Union, 2020). Nevertheless, addressing structural shortcomings in the long-term care sector, especially underinvestment, is pressing due to the rapidly ageing population (see Figure 1.3).

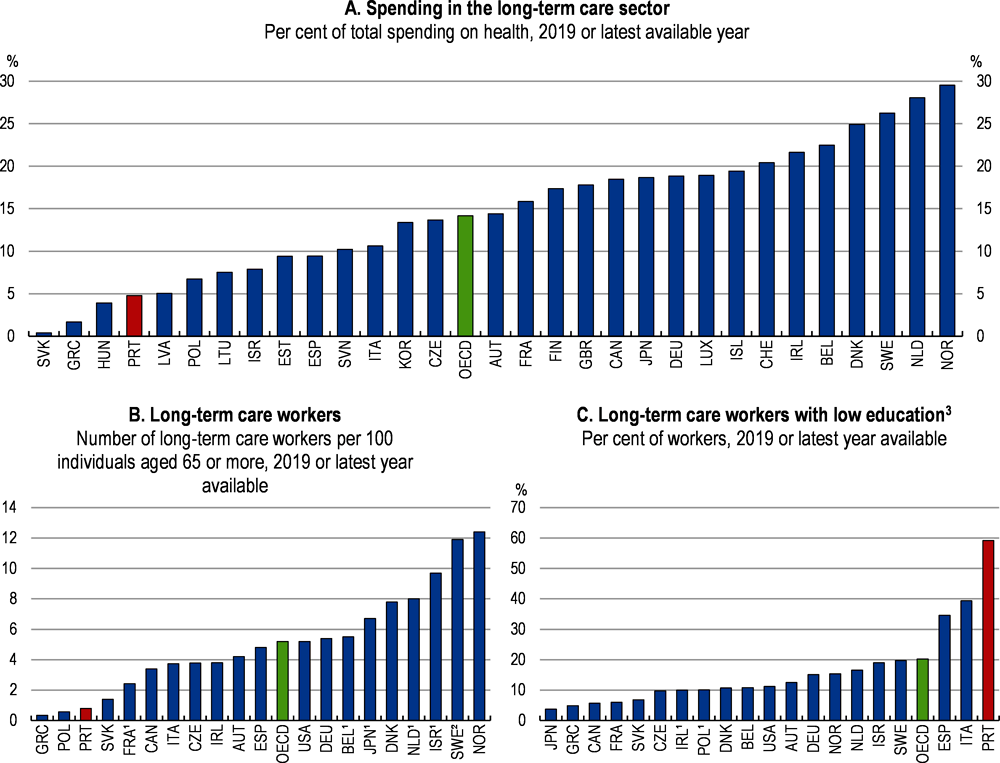

Spending on long-term care is one of the lowest across the OECD (Figure 1.28, Panel A), resulting in large unmet needs (OECD, 2019f). Only around 2% of adults aged 65 and over received long-term care in 2019, compared with around 11% in the OECD (OECD, 2021a). Similar to peer countries, Portugal relies on the support by families and other unpaid caregivers to provide long-term care for older people. Unpaid caregivers, mostly women, report worse self-perceived health outcomes and are disproportionately affected by poverty (WHO, 2020). Recent measures to support informal caregivers (i.e. providing them with a formal status, information, training, and a means-tested allowance) are welcome, but it is too early to assess their impact. Measures are limited to family members and should be extended to all informal caregivers (European Commission, 2019b).

Residential care capacity has grown from 1808 beds in 2007 to 8840 in 2015, but the provision of institutional care is significantly lower than in other OECD countries, resulting in high occupancy rates and long waiting times. Shortages are especially acute in larger urban areas, like Lisbon (WHO, 2020). Paid home-based care has developed only recently in Portugal and remains marginal. Public home-help services still reach less than 5% of elderlies (WHO, 2020). Geographical distribution of home care is uneven, home-care teams have to cover long distance in areas with low population density. This calls for increasing the funding of long-term care at the national level. Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan includes projects in the long-term care sector, amounting to around EUR 205 million.

The National Network of Continuing Integrated Care (RNCCI) and the Network of Social Services are the main providers of long-term care services. The governance of public long-term care services is fragmented, preventing the integration of services and thus optimising the service delivery (WHO, 2020). Improving cohesion and eliminating overlapping services in the two public networks can improve access, coverage and quality of services, not least by freeing up scarce resources. Integrating quality measures of hospitals’ performance could help to identify possible efficiency gains and free up resources to expand long-term care capacity (Shaaban, Peleteiro and Martins, 2020).