2. Yemen

This chapter looks in depth at the situation in Yemen. It presents the political context of the country and provides a detailed picture of the illicit trade. Human trafficking, drugs, heritages and antiquities as well as illicit capital flows are discussed. Finally, governance framework aimed at monitoring the country's maritime entries is also presented.

To understand current illicit trade dynamics in Yemen and the absence of any coherent or robust governance that aims to combat illicit trade flows within the country, it is important to acknowledge its pre-conflict dynamics. For this section, the focus is on the two decades that followed the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990 and the permissive illicit trade environment that Yemen’s political and military elite helped shape during this period.

Yemen has experienced almost non-stop conflict since 1948, significantly affecting governance across the country and the development of state institutions and the economy, notably institutions tasked with managing “illicit” flows, such as control over the coastline and technocratic oversight institutions managing borders and trade flows.1 This combines with the fact that Yemen’s geographic position straddles some of the world’s busiest trade routes, has independent and powerful tribes located across many border regions, and has long land borders which are geographically hard to police. As a result, the country has become a destination, origin, and transit point for many different forms of “illicit” movement, from human trafficking to the smuggling of arms, narcotics, historical artefacts, fuel, and various other forms of unregulated trade. Many of Yemen’s illicit flows have been the result of poorly implemented and regulated government policies, which have sometimes even incentivised illicit flows.

As a result, Yemen has long been a hub and conduit for regional and international arms trade and trafficking, as well as other illicit activities and goods that included: the outward smuggling of cheap, heavily subsidized fuel from Yemen to East Africa; the smuggling of people from East Africa and the Horn of Africa through Yemen that aimed to reach and secure employment in Gulf countries; and the smuggling of qat2 and other drugs (e.g. opiates and hashish) into neighbouring countries.

Yemen’s relevance for regional and international arms flows has been defined by two primary factors. First, its plentiful domestic weapons stocks – particularly small arms.3 Second, a political and military elite that aided, abetted, and ultimately benefited from a state-sponsored system that enabled arms dealers to operate and profit, in exchange for supplying Yemen’s Armed Forces with a percentage of the arms entering the country.4

For former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the facilitation of arms imports and smuggling to and across Yemen was a means of consolidating his position of power. First, the direct acquisition of weapons imported by private arms dealers and subsequent distribution among different military and security forces meant these weapons could be deployed against any domestic actors that posed a threat to him.5 Second, and equally important, a permissive arms trade environment acted as a critical form of patronage, whereby non-state actors were granted the freedom to manoeuvre and profit from the domestic and regional arms trade. This included a variety of actors operating at different stages of the process: from domestic arms dealers to the owners of maritime and overland transportation companies that helped move the weapons where they needed to go, and tribal leaders that permitted the transit of weapons flows through their local areas of jurisdiction.

Saleh’s prioritisation of the maintenance of the extensive patronage system and networks that he developed after becoming president of North Yemen in 1978 and unified Yemen in 1990 ultimately superseded state interests and institutions.6 In terms of illicit trade, this meant that illicit trade was allowed to occur through Yemen so long as it provided potential opponents the financial incentive to continue supporting Saleh and the system of patronage he oversaw.7 As a result, the state-run institutions and bodies that were technically responsible for the monitoring, prevention, and penalising of illicit activities were essentially powerless.

The lack of governance and varying degrees of involvement and complicity among Yemen’s elite regarding illicit trade that originated in or passed through Yemen was appealing to certain regional and international arms dealers, as well as their respective clients. Before the conflict Yemen was implicated in several transnational weapons pipelines and arms deals.

Illicit trade networks were also behind an illicit trade of diesel. Although Yemen is an exporter of crude oil, it imported diesel, which in turn was heavily subsidised by the state as a pillar of its social protection and development strategy. Government subsidized fuel would then get re-sold for profit by fuel traders.

Despite Ali Abdullah Saleh’s forced abdication of the presidency in February 2012 and replacement with incumbent President Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi, and the shifting of political alliances both during and after the 2012-2014 failed transitional period, a “business as usual” approach was adopted for illicit trade. As will become clearer in the sections below, the onset and escalation of conflict did, however, alter illicit trade dynamics and the previous governance structure that was designed to curb such activity.

Background

The Yemeni conflict originated in 2014 and has since created one of the largest humanitarian crises facing the world today. The civil war began when Houthi insurgents, a rebel group with a lengthy history of government opposition, took control of Sana’a, Yemen’s capital and largest city. Angered by the removal of fuel subsidies, the Houthis attempted to usher in a replacement government. After negotiations to establish this new government failed, the Houthis seized the presidential palace in early 2015.

The civil war has taken a particularly heavy toll on Yemeni civilians. The U.N. estimates that over half of 230,000 deaths in the country since 2015 result from indirect causes such as food insecurity and lack of access to health services. Furthermore, nearly twenty-five million Yemenis need assistance, five million are at risk of famine, and over one million have been affected by a cholera outbreak.

The crisis in Yemen also extends beyond conventional humanitarian issues, as illicit trade has played a larger role in the country’s economic landscape since the civil started. The primary government agency to combat this increasingly important risk is the Yemeni coast guard. Since 2015, the coast guard has worked closely with Joint Forces Command to protect Yemen’s coast from counterfeiting and organized crime. However, the coast guard has fallen victim to the civil war, as a least one boat has been struck by a sea mine likely placed by Houthi rebels. Outside of the coast guard, no other institutions are engaged in countering illicit trade.

One of the main products illicitly traded in Yemen is illegal weaponry. It is estimated that there are between 40 and 60 million weapons in the country, making Yemen the second-most armed country in the world after the United States. However, arms trafficking is not a new trend in Yemen. Prior to the civil war, Yemen was already a regional arms-trafficking hub with well-connected smuggling networks. The illegal arms trade is also not isolated to one part of the country. Arms markets flood the streets in both north and south Yemen.

Beyond the arms trade, the illicit flow of drugs in Yemen is also wreaking havoc in the nation. Yemen’s pervasive drug problem is rooted in cultural tradition, as the chewing of qat, goes back more than 500 years. It is estimated that around 90% of Yemeni men and 25% of Yemeni women chew these leaves daily.

This drug trade is not confined to Yemen, as drug trafficking out of Yemen and into Saudi Arabia is a persistent problem. The border between the two nations is incredibly porous, and just between 2008 and 2010, over 6 million kilograms of qat heading to Saudi Arabia were seized. During the same time, 13 million tablets of amphetamine and 500 kilograms of hashish were seized before they entered Saudi Arabia.

The drug trade also has close ties to the Yemeni conflict. Reportedly, in Houthi-controlled areas, narcotics are very prevalent and can even be found in grocery stores. Houthi militias have also transformed their territory into open drug markets, exploiting a lack of central authority to crack down on smuggling. The illegal drug trade is a large source of revenue for these groups.

Beyond the arms and drug trades, the illicit trafficking of cultural property is a problem in Yemen. Many cultural objects are illicitly looted from archaeological sites and are sold for a profit. Museum collections are also illicitly traded around the world. In recent years, the increased risk of illicit trafficking of cultural artefacts brought about by war and conflict, combined with the social-economic growth of the Africa and Arab States regions and the rapid expansion of the international art market, through internet, has created a fertile environment for the illegal trafficking of cultural artefacts originating from countries, like Yemen, that do not have the necessary measures in place.

To re-iterate, the current conflict contributed to the fragmentation and regionalisation of Yemen and consequently prompted a shift in previous illicit trade governance. The largely centralised, Sana’a-centric governance model now operates in tandem with a set of diffuse, and at times competing, localised governance models that mirror different areas of territorial control. Against the backdrop of violence and political and regional fragmentation, illicit goods have crossed front lines and different areas of territorial control inside Yemen relatively seamlessly. Pre-conflict illicit activities, such as arms, people, and drug smuggling have continued if not increased in scale and complexity and have been joined by an increase in the smuggling of historic artefacts and exotic plants and animals.

Weapons

Yemen has one of the highest levels of gun ownership in the world, with 2007 estimates that 10 million small arms are held by a population of 23 million.8 These stocks have increased significantly during the conflict that has existed since 2015, to the point where Yemen has begun to re-export portions of its stock through arms networks in the Horn of Africa and Beyond. Weapons are traded freely through open markets throughout the country. The conflict saw the weapon stock grow as many weapons supplied to armed groups have often been sold in local markets, often ending up in the hands of Houthi forces, as well as armed groups throughout Africa.9

Houthi armed forces rely partially on weapons and weapon parts supplied by Iran. Between 2015 and 2021, 15 maritime seizures were made by the CMF, the coalition and the Yemeni coast guard of illicit weapon shipments that originated from Iran and that violate the weapons embargo. Weapons come via two coastlines, Al Mahra in the eastern part of Yemen and the red seacoast in the Western part.

Most of the shipments were transported through stateless dhows and fishing boats.10 Weapons are also transhipped in the sea after first stopping at Puntland, Somalia,11 where Yemeni fishing ships are more familiar with the waterways and less conspicuous, and therefore can relatively easily bypass Saudi Led Coalition (SLC) naval forces and IRG coast guard forces.

The Iranian shipments include Iranian manufactured weapons such as missiles and their component parts, Russian weapons such as the AK-pattern rifles and PK type machine guns, and Chinese type 56 assault rifles. Investigations conducted by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime indicate that Iranian weapons rely to an extent on the same smuggling networks previously used by AQAP and IS.12

Weapons seem to have also been smuggled on land through the Omani border. Being transported on land and through Government of Yemen controlled territory indicated that within the Government of Yemen structure there exists complicit entrepreneurs that aid in the smuggling of the weapons into Houthi territory. A report by the Conflict Armament Research showed that it’s mainly the components of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) used in cross-border attacks on locations in Saudi Arabia that rely on components smuggled through the Omani border.13

Illicit trade in fuel and oil

The general collapse of centralised state authorities across many parts of Yemen has also led to major changes in its fossil fuels sector. Traditional export pipelines have been cut by frontlines, with domestic production and refining declining significantly, and a concurrent far greater dependence on imported fuels. These market dynamics have continued to encourage complex interplay of illicit activities around the sector (See section 4.2 for efforts to stop the illicit import of Iranian fuel). Crude oil export has continued, however, in an ad-hoc fashion, and with a complex revenue sharing relationship between local and central authorities in IRG controlled areas developing in light of the former’s increasing independence from central authorities. While rather irregular in nature, this is largely within the framework of non-illicit movements and transactions.

There have been also some isolated reports of crude oil being smuggled out of Yemen via a stretch of the Shabwa coastline.14 Fuel was reportedly trucked from an unknown production source to an area as being located near to Bir Ali Port (and 25km east of the LNG export terminal in Belhaf), where the fuel was then unloaded and transferred via a pipeline that connected the truck to a large vessel waiting offshore.15 Although the exact frequency of this reported smuggling activity is unknown, there have been a few separate alleged sightings of this activity taking place in late 2015, July 2018, and August 2018.16 The expectation is that if this activity was happening on a large scale there would have been more reporting and alleged sightings of this activity with the kind of visual imagery that was presented to back up earlier allegations of smuggling.17

Human Trafficking

Given the strategic location of the Republic of Yemen in the south-western corner of the Arabian Peninsula, it has long served as the established route for irregular migrants from the Horn of Africa seeking refuge and economic opportunities in wealthy Gulf states, a source country for outward movement of irregular migrants, and to some extent a destination country. The illicit smuggling networks that facilitate these movements are highly lucrative, and as with other aspects of illicit trade outlined in this report, many Yemenis have turned to illicit activities due to the impact of the conflict both on the Yemeni states ability to regulate these activities, as well as the severe degradation of other economic opportunities.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), 50,000 migrants from the Horn of Africa, mainly Ethiopia, entered Yemen alone during 2018.18 While these movements preceded the current conflict, a combination of the breakdown of state authority in Yemen, with a series of environmental, economic, and political crises in the Horn of Africa, has prompted higher rates of migration since the beginning of the current conflict in Yemen in 2015. These migrants have been highly vulnerable to abuse, and in turn have been caught up in a range of other illicit activities, notably forced conscription by armed actors, forced labour, kidnapping for ransom, and sexual abuse. Increased and often punitive efforts by Saudi authorities to limit migration flows at the border have seen large numbers of migrants stuck in Yemen for significant time.19

Illicit “human trafficking” flows have not been limited to migrants from the Horn of Africa. The impact of the conflict in Yemen has seen thousands of Yemenis utilise smuggling networks to enter Saudi Arabia to access livelihood opportunities no longer available inside Yemen. The business of human trafficking has become highly lucrative, and highly interlinked with other illicit flows, such as weapons, drugs, and unregulated financial transfers, which will be addressed in the next section.

Narcotics

Narcotic exports from Yemen, largely in the form of hashish of the local drug, Qat, have been a major form of illicit trade out of Yemen. Prior to the war, an estimated 160 million USD of drugs were exported from Yemen, primarily through land or coastal routes into Saudi Arabia.20 This has reportedly continued and increased during the recent conflict. Yemen’s northern tribes were historically the greatest benefiter, many of which support the Houthi movement, which has in turn made significant efforts to expand its control over the trade. This trade has increased significantly because of the conflict. Vibrant border markets that existed on the border between Saudi Arabia and Yemen have largely been destroyed because of the conflict.21 While the illicit trade in drugs and weapons existed prior to the conflict along the border, it didn’t dominate all economic activity, with much trade being legal. Since the conflict, many involved in what were previously regulated businesses turned to more illicit means to ensure continuation of livelihoods. With traditional border crossings largely being closed, dozens of smuggling routes have developed across the porous border, thriving on a combination of mountainous terrain and complicit and corrupt border security.22 Other drugs include cocaine, cannabis, and heroine. Saudi efforts to improve control over their border have been hamstrung by the corresponding decline in capacity of regulatory/security authorities on the Yemen side.23

Unregulated Financial Networks, illicit trade and illicit capital flows

The increase in illicit flows in their various forms in Yemen has been closely linked to the established presence and growth of unregulated financial networks in Yemen, the Horn of Africa, and into the Arabian Peninsula. The use of “hawala” networks to facilitate trade are not new. However, over the course of the current conflict, the regulatory frameworks that did exist in Yemen have been severely undermined in the face of the breakdown of central governing authority, the impact of international de-risking on Yemen’s banking system, the partial bankruptcy of Yemen’s banks, and the ongoing institutional conflict between Houthi controlled economic authorities and those of the IRG Central Bank of Yemen. By 2016, this had seen a significant liberalization of local “informal” hawala services, with hundreds of new institutions springing up around the country, largely facilitating the inward flow of remittances and the outward flow of funds for trade financing.24 The significant lack of “Know Your Customer” practices linked to these networks, and therefore the nonexistence of anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism controls, is a major characteristic. For example, Hawala networks are critical in facilitating the outward flow of weapons from Yemen to Somalia, as was shown in a 2020 investigation by the Global Initiative against transnational organized crime.25

Yemen is also ranked as one of the world’s highest sources of illicit capital outflows among poor countries, with 12 billion USD being estimated to have left the country between 1990 and 2008, dwarfing the amount of foreign aid entering the country during this time.26 Capital outflow has likely significantly increased during the conflict, although data is hard to find. Anecdotal evidence coming from interviews with Yemeni economists based in Cairo, stated that real estate have been bought by Yemenis over the course of the conflict alone, potentially reflecting the movement of additional capital from Yemen.27 The lack of any viable economic investment opportunities inside Yemen has increased the incentive to move wealth offshore, largely outside of the framework of government regulatory frameworks or taxation.

Heritage and antiquities

As with other forms of illicit trade outlined in this report, the collapse of state authorities tasked with countering the illicit trade in antiquities has fuelled a vibrant export market for Yemen’s cultural heritage. Notable was the 2015 looting of Taiz Museum of several ancient manuscripts, with only a small portion being recovered. The non-payment of public sector salaries in Yemen has also significantly increased the theft of antiquities. The destination for stolen items, according to different investigations of the matter, is generally Saudi Arabia. A contributing factor to the outward flow of Yemen’s antiquities – illegal under Yemeni law – is cataloguing and preservation that existed even prior to the conflict, with many items remaining in the hands of local Mosques and families.

Wildlife in Socotra

Socotra is an archipelago that sits around 380 Kilometers south of Aden consisting of 4 Islands. Due to its rich wildlife and its importance for biodiversity conservation, it was designated in 2008 as a UNESCO world heritage Site.28 Also because of those reasons, the Island has always been the site of smuggling. Smuggling in Socotra comes in the form of tourists that try to smuggle out endemic animals and plants for collection purposes as well as ex-situ breeding.29 The island’s relative isolation up until the end of the 20th century has helped in preserving its exotic wildlife. However, with the turning of the century the Island attracted both opportunistic wildlife traders as well as collectors. The onset of the 2015 conflict saw a growing UAE presence on the Island and has helped in decreasing the smuggling of wildlife due to limiting fighting in and out of the Island.

Counterfeits

Yemen has been appearing several times in the OECD/EUIPO studies on illicit trade in counterfeit good (see (OECD/EUIPO, 2017[7]) and (OECD/EUIPO, 2021[6])). A more recent data on customs seizures counterfeit goods reconfirms that Yemen was a remarkably vibrant hub for the illicit trade in fakes. Over the period 2011-2019 Yemen has been reported as a destination and source of fake goods, which points at its potentially important role in facilitating the transit of fakes (see Table A.1 and Table A.2 in the Annex). Importantly, the volumes of seizures of fakes in Yemen has been constantly decreasing over the analysed period, while the volumes of counterfeits coming from Yemen, remained stable. This suggest that counterfeit goods were losing their importance for Yemeni enforcement. This is clearly linked with the on-going conflict, and changing priorities of relevant enforcement agencies.

Data on customs seizures indicate that counterfeit goods imported into Yemen mainly came from Egypt, China, United Arab Emirates, and Turkey. These four countries represented more than 85% of seizures of counterfeit goods destined to Yemen. Importantly, such global hubs of trade in fakes as Hong Kong (China) and Singapore don’t appear on the list of main provenance countries for counterfeit goods imported into Yemen. To the contrary, some neighbouring countries such as Egypt, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia play an important role.

It is important to note that among the countries of origin of counterfeit goods destined to Yemen, a distinction is made between economies that export counterfeit goods to Yemen on a recurrent basis and those that export on an occasional basis. Figure A.1, which shows the provenance economies of counterfeit goods imported into Yemen by year from 2011 to 2015, is useful in understanding this distinction. This figure indicates that year on year, China, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey are still the main countries supplying counterfeit goods to Yemen. In contrast, one can note a seasonal trend for economies such as the US, Germany and the UK which are only occasional suppliers of counterfeit goods to Yemen.

The source of counterfeit goods destined to Yemen has evolved over time. Egypt was the top provenance economy of Yemeni fake imports during the 2011-13 period while United Arab Emirates was the first source more recently. While Egypt, China and United Arab Emirates were the main providers of fake goods destined to Yemen, there was also seasonal trend like the role played by the United States in 2011 (See Figure A.1 in the Annex).

Counterfeits departing from Yemen were mainly destined to nearby countries (Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, Egypt and United Arab Emirates) and to the EU countries (Netherlands and Germany).

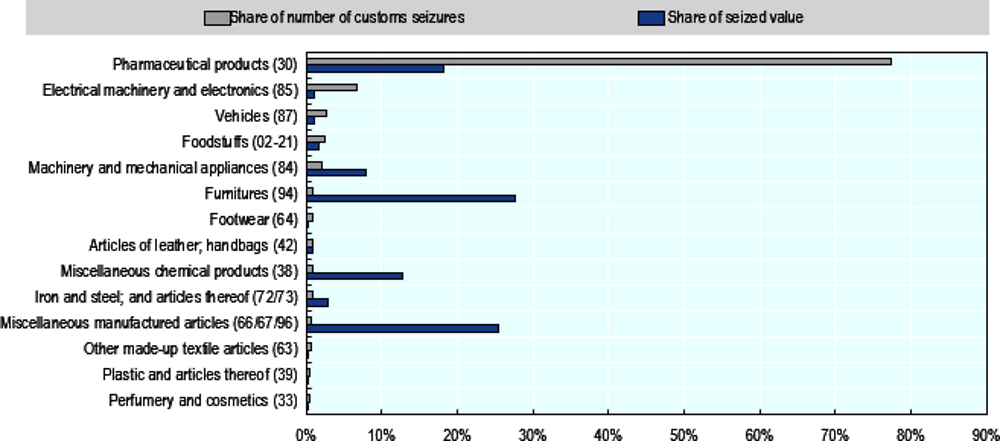

In terms of product categories, a wide range of fake products has been smuggled to Yemen (Figure 2.1). Over 2011-19, most of counterfeit goods destined to Yemen were fake pharmaceuticals (77% of customs seizures destined to Yemen) followed by electrical machinery and electronics (7%), spare parts (3%) and foodstuffs (3%). The fake pharmaceuticals destined to Yemen included anxiolytic, diabetes treatment, erectile dysfunctions treatment, lung diseases treatment or gastric ulcer treatment.

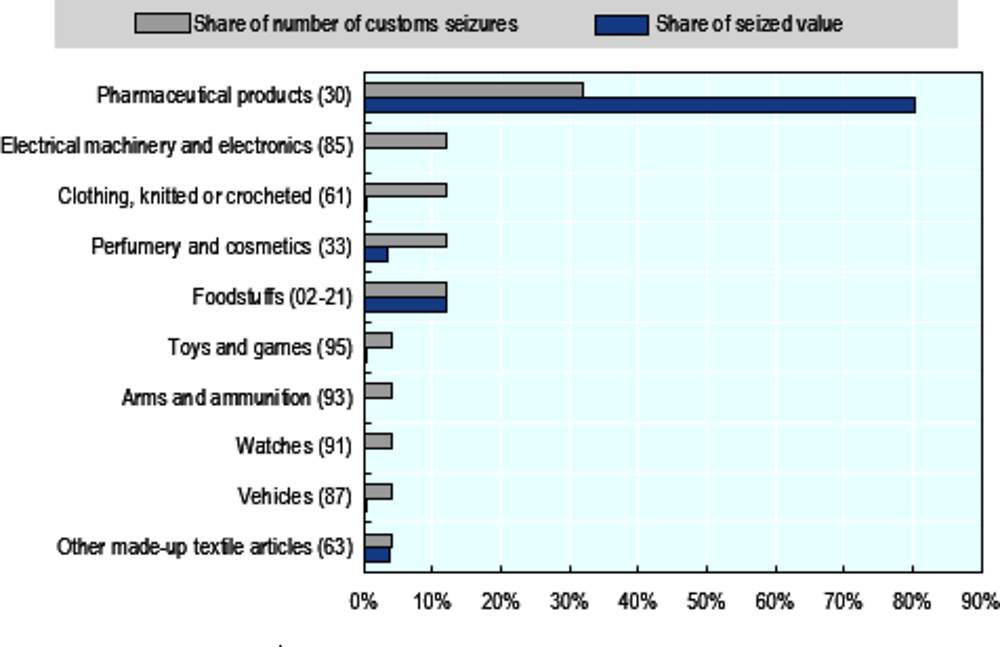

While some of these goods stay in Yemen, many of them are re-exported, as Yemen is abused a transit point in global trade in fakes. Data on customs seizures shows that counterfeit goods originating from Yemen were mainly pharmaceuticals (32%), electrical machinery and electronics (12%), clothing (12%), perfumery and cosmetics (12%) and foodstuffs (12%). In terms of value, fake pharmaceuticals clearly dominated, representing 80% of the seized value of counterfeit goods coming from Yemen (see Figure 2.2).

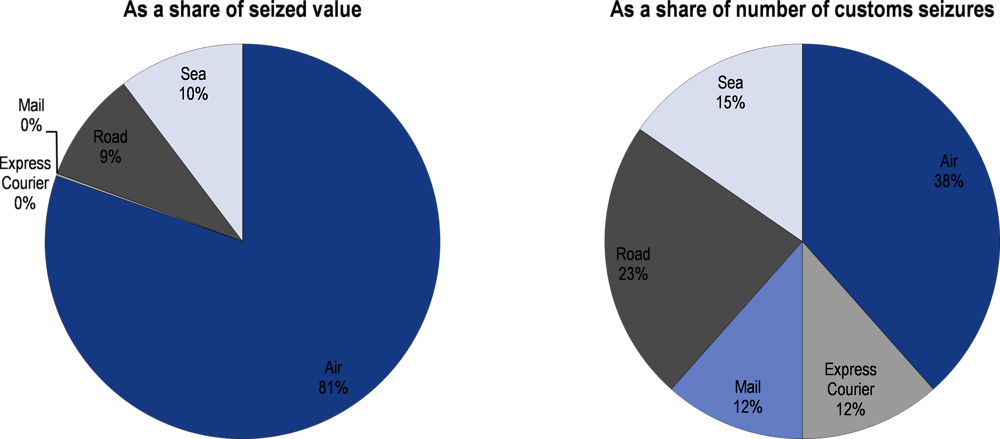

Data on customs seizures indicate that air was the preferred conveyance methods of counterfeit goods originating from Yemen (see Figure 2.3). In terms of seized value, air clearly dominated – 81% of seizures was made on air shipments, 10% referred to sea shipments, and 9% road transport. Interestingly, fakes that were leaving Yemen, were shipped through several transport modes including air (38%), road (23%), sea (15%), mail and express courier (both at 12%).

The data on customs seizures also provide information on shipment size. This indicates that shipment of counterfeit goods destined to Yemen tend to be large. Indeed, almost 100% of seizures refer to shipment containing more than 10 items. This result differs from what is observed in the OECD countries, where small shipments tend to dominate trade in counterfeit goods. As noted in OECD/EUIPO (OECD/EUIPO, 2021[6]) the dominance of small shipments is trend is directly correlated with the on-going boom of e-commerce coupled with the expansion of postal and express services, which may be less developed in Yemen.

The analysis of shipment size reveals that trade in counterfeit goods originating from Yemen is dominated by large shipment. Indeed the largest majority of seizures (92%) refers to shipment containing more than 10 items.

The intervention and continued involvement of different regional and international actors prompted the establishment of more rigorous maritime monitoring and regulation of goods entering the country. The primary objective that underpins the various regulations and steps taken by the Saudi-led coalition and its allies has been to prevent the Houthis from receiving weapons that could drastically alter conflict dynamics and pose a threat to Saudi national security. The accomplishment of this primary objective has been mixed.

Resolution 2216/UNVIM

In April 2015, the United Nations Security Council passed resolution 2216, which aimed to restrict weapon flows into Yemen. The resolution imposed an arms embargo on former president Ali Abdallah Saleh and Abdulmalik Al Houthi two months after the Houthi Saleh alliance solidified its control over Sanaa by forming a ruling council. It is also important to note that increasing instability and lack of arms regulation in Yemen coupled with its abundant arms stockpile also raised concern over its role in supplying other rebel armed groups in the wider region.

Because of complications in implementing Resolution 2216, commercial imports into Yemen declined impacting the livelihood of civilians.30 The UN regional humanitarian coordinator for Yemen established the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen to better coordinate the implementation of the Resolution. In May 2016, the United Nations Office for Project Services implemented a Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM) to ensure that cargo shipments delivered to Red Sea ports are compliant with Resolution 2216.31 UNVIM runs an assessment of all commercial imports destined for seaports under Houthi control, most notably the Red Sea ports of Al Hodeidah and As Salif.

In addition to a commercial import clearance, UNVIM requires that cargo undergo physical inspection in Djibouti. UNVIM inspection and clearance does not however apply for dhows, which tend to be the primary vector for illicit trade into and outside of Yemen.32

IRG policy to combat Iranian fuel imports

During the conflict IRG introduced different fuel import regulations that aimed in part or in full to prevent the import of Iranian fuel to Yemen, following decisions by it to support the US implemented sanctions regime, as well as to combat support to the Houthi movement illegal under Security Council Resolution 2216. The rationale behind this approach was to limit the Houthis’ ability to generate revenue from different Iranian fuel financing schemes present from 2016 to 2018 that would in turn be used to support the war effort.

In September 2018, IRG introduced Decree 75 that contained a new set of specific requirements that fuel importers needed to meet moving forward to obtain clearance from IRG to import fuel to Yemen.33 Additional clearances are also needed from UNVIM, the Saudi-led coalition, and the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) for fuel shipments via Al Hodeidah Port.

A Technical Office was established to review documentation submitted by fuel importers that would enable the Technical Office to assess importers’ level of compliance with the Decree 75 requirements.34 The Technical Office will then coordinate with the Saudi-led coalition regarding the issuance of clearance for fuel traders that wish to import via Al Hodeidah Port. The Saudi-led coalition will not grant fuel vessels authorisation to proceed from the Coalition Holding Area (CHA) to Al Hodeidah Port until the Technical Office has issued its own clearance for the vessel/shipment being held in CHA.

Among the main documents, that the importer must provide to the IRG-run Technical Office to obtain clearance from IRG to import fuel to Yemen includes a certificate of origin approved by the Chamber of Commerce in the exporting country or completed technical inspection certificates from approved companies. This specific requirement was designed to ensure that the fuel being imported into Yemen was not of Iranian (or Iraqi) origin.35 Likely in an effort to enforce this, June 2019, IRG introduced a ban on fuel imports from Al-Hamriya port in Sharjah, UAE, or any port in Iraq or Oman.36 The ban was, however, only temporarily enforced, with imports again allowed from Al-Hamriya and Oman but not Iran nor Iraq.37

IRG and Saudi Led Coalition prohibited items lists:

In October 2018, the IRG and Saudi-led coalition published a list of goods restricted for entry into Yemen. The list includes eight categories of imported goods that can be used for military and violent activities: vehicles (including pickup trucks and four-wheel drive vehicles); power generation materials (including deep-cycle batteries and solar panels); telecommunication equipment; toys; mechanical spare parts; unmanned aerial vehicles; explosive material; and chemicals.38 Some of these goods, including four-wheel drive vehicles, are able to enter through land ports, and are usually imported through Salalah Port in Oman and transported via land to the Shihan border crossing. Several of these items however still make their way into Yemeni markets, mainly through land crossings (See Omani border below) with the prohibition only serving to increase their prices.

Yemeni waters

There are several countries engaged in monitoring and regulating maritime activity in Yemen’s waters and off Yemen’s coastline, as part of ongoing regional and international efforts.

Saudi Arabia

Members of the Saudi-led coalition, namely Saudi Arabia, have deployed warships along Yemen’s Red Sea coastline to monitor vessel activity, and specifically vessels that wish to enter and unload at the Houthi-controlled Red Sea ports of Al Hodeidah and Saleef. They also prevent fuel vessels from unloading at Ras Issa, which has been offline since August 2017.39 Saudi Arabia established the Coalition Holding Area (CHA), which vessels must pass through as part of the import process for vessels that wish to proceed to and unload at Houthi-controlled ports. The CHA is located in the Red Sea, adjacent to Jazan, Saudi Arabia, and Massawa, Eritrea, and about 250km from Al Hodeidah Port.

Saudi-led Coalition / UAE

There is also an unknown number of Saudi-led coalition forces stationed on Mayun Island (also known as Perim Island) that is located on the strategic Bab al-Mandeb Strait. UAE forces were thought to be present on the island before it started to reduce the number of UAE soldiers deployed in Yemen in 2019.40 In May 2021, a Saudi-led coalition official dismissed reports that UAE forces were (still) deployed at Mayun Island, stating that: “all equipment currently present on Mayun Island is under control of the Coalition Command, and is situated there to... counter the Houthi militia, secure maritime navigation and support West Coast forces.”41

Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) and Joint Task Force CTF-151

The Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) is a 34-member multinational coalition of naval forces that patrol the so-called Maritime Security Transit Corridor that spans from the Gulf of Oman to the Red Sea.42 The CMF coordinates with the Saudi-led coalition on anti-smuggling operations. Brazil currently leads the Combined Task Force 151 (CTF-151), which is one of three task forces operated by CMF.43 CTF-151 is deployed in the Gulf of Aden where it is tasked with combating piracy in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia in the Indian Ocean.44

Ministry of Transport and Yemen Coast Guard

Prior to the current conflict, the Ministry of Transport (MoT) maintained direct oversight of Yemeni seaports. The current overarching conflict between the Houthis (formerly the Houthi-Saleh bloc until the Houthis killed former President Saleh in December 2017) and the internationally recognized Yemeni government (IRG) led to the bifurcation of state-run institutions. In terms of regulating the movement of people and goods into and out of Yemen, the IRG-run MoT, which is headquartered in Aden and has an important liaison office in Riyadh, is responsible for providing requisite clearance for vessels to berth at Yemeni seaports.45

The IRG-run MoT has direct oversight over two out of three of Yemen’s seaport corporations: the Yemen Gulf of Aden Ports Corporation (YGAPC) that oversees Aden Port and other small ports west of Balhaf LNG export terminal in Shabwa; and the Yemen Arabian Sea Ports Corporation (YASPC) that oversees Mukalla (Hadramawt), Nishtun (Al Mahrah), and the Island of Socotra.46 The IRG-run MoT also has a degree of oversight over Mokha and Midi ports in Taiz and Hajjah governorates, after anti-Houthi forces captured these ports from the Houthis during the conflict.47 The third Yemen seaport corporation – the Yemen Red Sea Ports Corporation (YRSPC) – is run by the Houthis and oversees the Red Sea ports of Al Hodeidah, Saleef, and the Ras Issa export terminal.48 Ras Issa is currently being used as a fuel storage facility under the supervision of the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC).

The Yemen Coast Guard, which was established by Republican Decree in 2002 but not fully operational until 2004, falls under the umbrella of the IRG-run Ministry of Interior and is headquartered in Aden.49 The Yemen Coast Guard is technically responsible for the following missions: human migration interdiction and anti-piracy, anti-smuggling operations (e.g. drugs and other illicit materials), maritime safety, and fishery protection.50 The Yemen Coast Guard, which was already operating at a reduced capacity before the conflict due to limited resources, has continued to struggle during the conflict.

Management of Yemeni seaports and hydrocarbon export terminals

The following is a summary of the main Yemeni seaports and export terminals that are managed by different entities. Information concerning the location of each port or export terminal is included along with an indication of the forces present.

References

[2] Bindner, L. (2016), Illicit Trade and Terrorism Financing December 2016 – Interim result, Center for the analysis of terrorism, http://cat-int.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Interim-note-Illicit-trade-and-terrorism-financing-Dec-2016.pdf.

[1] OECD (2018), Governance Frameworks to Counter Illicit Trade, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264291652-en.

[6] OECD/EUIPO (2021), Global Trade in Fakes: A Worrying Threat, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/74c81154-en.

[5] OECD/EUIPO (2019), Trends in Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union Intellectual Property Office, Alicante, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9f533-en.

[7] OECD/EUIPO (2017), Mapping the Real Routes of Trade in Fake Goods, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278349-en.

[4] OECD/EUIPO (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252653-en.

[3] Shelley, L. (2020), Illicit Trade and Terrorism, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26927661.

Notes

← 1. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2015/01/21/yemen-the-difficulties-of-curtailing-smuggling-and-the-regional-implications/#_edn7

← 2. Qat, also known as khat, is a plant native to Yemen. Its leaves contain a stimulant, which gives the chever of khat leaves some excitement. Khat chewing is a practice and social custom that dates back thousands of years in the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

← 3. Yemen’s arms supplies increased during the 1994 North-South civil war. In 2003, the Small Arms Survey (SAS) estimated that there were 6-9 million weapons circulating inside the country; Miller, Derek, Demand, Stockpiles, and Social Controls: Small Arms in Yemen, Small Arms Survey, May 2003.

← 4. Senior officials (e.g. from the Ministry of Defence, the military, and the president’s office) provided the state approval that enabled arms dealers to import shipments to Yemen. Import permits granted to arms dealers would list Yemen’s Armed Forces as the end user. For these types of arms deals, the local arms merchant would finance the deal themselves and arrange for transportation to Yemen. Once inside the country, around 10 percent would go to Yemen’s Armed Forces (overseen by President Saleh and Brigadier General Ali Mohsen Al Ahmar). The rest of the weapons shipment would be broken down into smaller consignments that were either sold on the domestic arms market and/or sold to other arms brokers that could secure the entry and sale of weapons to buyers in other neighbouring countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the Horn of Africa.

← 5. A prime example is the six wars that Saleh and Yemen’s Armed Forces fought against Houthi militants in Sa’adah governorate from 2004-2010. Saleh later allied with the Houthis during the current conflict after being removed as president in February 2012.

← 6. Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combatting Corruption in Yemen,” November 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No4_En.pdf; Alley, April. “Shifting Light in the Qamariyya: The Reinvention of Patronage Networks in Contemporary Yemen.” PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2008.

← 7. Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combatting Corruption in Yemen,” November 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No4_En.pdf; Alley, April. “Shifting Light in the Qamariyya: The Reinvention of Patronage Networks in Contemporary Yemen.” PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2008.

← 8. https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/resource/fault-lines-tracking-armed-violence-yemen-yava-issue-brief-1

← 9. https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2019/02/middleeast/yemen-lost-us-arms/, and https://jamestown.org/program/arms-from-yemen-will-fuel-conflict-in-the-horn-of-africa/

← 10. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Snapping-back-against-Iran-The-case-of-the-Al-Bari-2-and-the-UN-arms-embargo_GITOC.pdf

← 11. https://undocs.org/S/2016/919

← 12. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Snapping-back-against-Iran-The-case-of-the-Al-Bari-2-and-the-UN-arms-embargo_GITOC.pdf

← 13. https://www.conflictarm.com/perspectives/iranian-technology-transfers-to-yemen/

← 14. Author interviews in February 2020

← 15. Author interviews in February 2020

← 16. https://twitter.com/3MAR7_7/status/1025413816174215168?s=09 ; https://twitter.com/kamal_ALNomani/status/1024302611355324417?s=19 ; https://twitter.com/NYS9511/status/670895229478830080?s=19

← 17. https://twitter.com/3MAR7_7/status/1025413816174215168?s=09 ; https://twitter.com/kamalALNomani/status/1024302611355324417?s=19 ; https://twitter.com/NYS9511/status/670895229478830080?s=19

← 18. https://www.iom.int/news/iom-raises-protection-concerns-2018-migrant-arrivals-yemen-approach-150000

← 19. Saudi anti-smuggling efforts have increased substantially over the last decade, with large sums invested in improving border security. This includes the construction of electrified fences, surveillance and heightened security presence. This has even been reflected in abuse towards migrants, with some reports of mass shootings taking place in border areas. See, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-saudi-idUSKBN0KV1VH20150122

← 20. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2015/01/21/yemen-the-difficulties-of-curtailing-smuggling-and-the-regional-implications/

← 21. https://carnegie-mec.org/2021/06/14/yemeni-border-markets-from-economic-incubator-to-military-frontline-pub-84752

← 22. https://carnegie-mec.org/2021/06/14/yemeni-border-markets-from-economic-incubator-to-military-frontline-pub-84752

← 23. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/hunting-children-saudi-border-guards-prey-teenage-yemeni-qat-smugglers.

← 24. Yemen Bringing Back Business Project: Risky Business - Impact of Conflict on Private Enterprises. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32048

← 25. https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/yemen-somalia-arms/

← 26. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Middle%20East/0913r_yemen_es.pdf

← 27. Interview with Cairo based Yemeni Economist

← 28. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1263/

← 29. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09397140.2011.10648899

← 30. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2016-09/the_story_of_the_un_verification_and_inspection_mechanism_in_yemen.php

← 31. https://www.vimye.org/doc/UNVIM%20SOPs%20English.pdf

← 32. UNVIM carries out an initial desk review of each application (including the required supporting documentation provided to it) as well as a physical inspection of the shipment.

← 33. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6620#Import-regulations

← 34. The Technical Office previously operated under the umbrella of the IRG-run Economic Committee that is no longer operational. The Technical Office currently operates under the authority of the Supreme Economic Council that is overseen by the prime minister.

← 35. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6620#Import-regulations

← 36. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7665#Economic-Committee-Bans-Oil-Imports-from-Oman-UAE-and-Iraq-Ports

← 37. Interviews with operational actors, August 2021

← 38. https://almahrahpost.com/news/6488#; https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/print~119945

← 39. Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combatting Corruption in Yemen,” November 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No4_En.pdf.

← 40. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/11/world/middleeast/yemen-emirates-saudi-war.html

← 41. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-led-coalition-says-its-behind-military-buildup-red-sea-island-2021-05-27/ .

← 42. https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/

← 43. https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-151-counter-piracy/ ; The other two task forces are: CTF 150 (Maritime Security Operations outside the Arabian Gulf) and CTF 152 (Maritime Security Operations inside the Arabian Gulf); https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/

← 44. https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-151-counter-piracy/

← 45. Key informant interview on October 03, 2021.

← 46. http://www.portofaden.net/en; https://www.yaspc.co/

← 47. https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2016/01/07/Yemen-troops-seize-northwestern-port-from-Houthis-militias; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-idUSKBN15M2FI

← 49. https://www.facebook.com/ycg2017/; http://www.y-coastgaurd.com/?fbclid=IwAR1AtX3nOq1r4xUQFMyk3wDTjGfQs0ErzsoZJDUreO5hphFjNVw3k_gDNGM

← 50. http://www.y-coastgaurd.com/?fbclid=IwAR1AtX3nOq1r4xUQFMyk3wDTjGfQs0ErzsoZJDUreO5hphFjNVw3k_gDNGM