6. Attraction, admission and retention policies for international students

This chapter reviews OECD countries’ policies to attract, admit and retain international students. It provides examples of communication and outreach strategies to international students as well as parameters for their admission. It outlines policies in place that support international students during their stay, such as through labour market access and the admission of family members. It looks at international students’ stay prospects to search for a job upon graduation. It finally discusses policies to monitor the compliance of international students with the regulations set out on their study permit and ensure that institutions and students do not misuse this channel.

In all OECD countries, a study permit requires proof of acceptance by a university, proof of financial means to support living expenses, and health insurance. Despite similar core requirements, rejection rates for study visas vary greatly, ranging from 2% to 40% in OECD countries with available data.

Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden are the only OECD countries where international students enjoy full access to the labour market during their study programme with no restrictions. In all other countries, labour market access is restricted in some way, most commonly via an hourly limit of work permitted during classes. Only in Colombia are all international students prohibited from working.

Over the last decade, OECD countries have implemented wide-ranging policies to retain international students after completion of their degree. In particular, international students can remain in the country upon graduation to look for a job in almost all OECD countries. Most of these postgraduate extension schemes have a duration between 12 and 24 months, though they extend to three years or more in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

To monitor that international students comply with the provisions set out in their study permit, some countries require the Higher Education Institutions to report on their students’ progress or lack thereof, while in other OECD countries this obligation rests with the student themselves in order to prolong their permit. Other integrity concerns include misuse of the visa to overstay, to engage in unauthorised employment, and to conduct technological or military espionage.

While student migration can be of great benefit to the student, the host institution and the host country, the delegation of a gatekeeping role to higher education institutions, and the growing share of economic migration comprised by former students, still carry a risk of distorting migration regulation, ensuring respect of labour market regulations, and in extreme cases, of malicious misuse.

Over the last decade, OECD countries have taken active measures to attract, support and retain international students. The attraction and admission of international students involves many actors, including universities and agencies specialising in higher education marketing. Higher Education Institutions (HEI) carry most of the costs of informing and pre-screening prospective students. In this respect, the role of national authorities in the attraction and admission process is more limited than for other migrant groups.

While international students have to meet certain self-sufficiency and insurance criteria, once accepted, they often do not undergo the same skills assessment as labour migrants. This is despite the fact that in most OECD countries international students can work (part-time) during studies and stay in the country upon graduation to look for a job. In many countries, they also face facilitations to enter the labour market and stay in the mid to long term.

Against this backdrop, this chapter provides an overview of the policies in place in OECD countries along five key areas: i) outreach and communication to international students; ii) parameters for admission; iii) support during studies; iv) retention after graduation; and v) monitoring of compliance.1, 2

A first step for attracting international students is to inform relevant target audiences about the unique advantages of study, research, and live in their respective countries and institutions. International student outreach across the OECD is characterised by a diversity of communication initiatives on an institutional, national, and regional level, as well as by a diversity of actors involved, including ministries and higher education agencies, universities, and private agencies specialising in higher education marketing.

Communication channels

All OECD countries have official national websites to inform international students about the higher education programmes offered and to provide relevant information regarding the migration process. In some countries, such as in Sweden, the website content on fees, residence permits, and scholarships changes depending on the target audience. It utilises the IP address of the connection and allows potential applicants to choose the information relevant to their nationality.

These websites and related outreach efforts are either managed by a designated ministry, such as the Ministry of Education in Denmark and Italy, or by specialised independent agencies and organisations in charge of promoting the country as a destination of international study, such as DAAD in Germany and Campus France in France (Table 6.1).

One important channel to promote international study are student fairs and the presence of overseas offices. Over the last three years, about two-thirds of OECD countries have arranged or participated in (virtual) student fairs in origin countries (Annex Table 6.A.1). The main OECD destination countries (Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Germany, France and Japan) have agency offices in origin countries, but so do Austria, Korea and Sweden. Campus France has, for example, more than 250 offices and branches located in over 120 countries.

Social media have become an increasingly important communicational tool for student attraction. Given that international students constitute a particularly diverse audience in terms of nationality, degree level, study interest, culture, language, and income, with different media usage habits and access to technology, OECD countries use a diverse mix of communication channels and platforms. Most OECD countries have social media presence on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and LinkedIn. In some cases, the governments use more nationally specific social media platforms. Australia and Korea are, for example, using the social platform Sina Weibo to target Chinese students.

Reports from communication officers on higher education3 highlight that using social media to engage discussions and dialogue, rather than just “broadcast” information, is especially important to build trust and to respond to information needs.

Another channel to reach potential students are student and alumni networks. They provide the opportunity to reach possible international students through intermediaries who can share their personal experience and answer questions in the languages of the specific target audiences. In an effort to build a stronger community of international students, the Czech National Agency for International Education and Research (DZS) invited student ambassadors and alumni to use their social media channels. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Kingdom launched student-led communication campaigns to reassure and support prospective EU and international students to continue with their plans to study in the United Kingdom. The campaign produced more than 100 student testimony videos where students gave their view on their experience of studying at a British university during the pandemic. Of more than 2 000 prospective international students surveyed, 67% said that the campaign had made them feel more confident to continue their plans to study in the United Kingdom. In France, the communication campaign Bienvenue en France, launched, in 2020 uses actual students not only for testimonies on their website, but also as ambassadors at student fairs.

Overall, OECD countries and their national student agencies use a multi-channel approach, reaching out to audiences in different places at different times, online and offline, allowing for feedback from audiences as well as the inclusion of alumni networks and ambassadors.

Effective messaging

To attract international students, countries also adjust their messaging to the identified reasons and preferences of the international students to choose their country. While some countries highlight the international reputation and quality of education, others highlight additional and increasingly valued elements such as the diversity of students in the study location, their culture, quality of life, or general safety. For example, Sweden developed a new communication and brand strategy after surveying 7 000 international students in Sweden and discovering that two main factors determining the choice of Sweden were the Swedish lifestyle and its education system.

Estonia’s main message revolves around the strong recruitment and employability perspectives granted by Estonian diplomas. Canada highlights the prospects for international students to eventually become residents. In contrast, the outreach of Hungary and the United States makes no mention of retention.

Targeting specific students

Some countries target international students from certain countries and backgrounds. The British Council has, for example, run specific campaigns targeting China, particularly promoting the United Kingdom as a destination to learn English to prepare for an international job market. Among other groups, Latvia and the Slovak Republic also target their own nationals living abroad. Most countries target multiple countries. For example, New Zealand has a list with currently 13 countries on which the marketing activity is focused. In Israel, a similar list exists but is limited to four countries: Canada, China, India, and the United States. Spain targets students from countries of Latin America, the Mediterranean basin and North Africa.

Targeting international students based on characteristics other than their country of origin is less common. Attracting individuals with particular language skills, if considered at all, is mostly done in the context of particular scholarship programmes for studying in the national language, for example in the Slovak Republic. Canada also expanded a specific programme (Student Direct Stream), which provides faster processing for applicants resident in certain countries, to include prospective students from Morocco and Senegal and to encourage more young French speakers to choose to study in Canada.

Only a handful of OECD countries target international students based on their intended field of study or broader labour market needs as in the case of Australia. Among those who do, sectors include information technology and communication (ICT) in Estonia and STEM subjects in the United States. In Lithuania and the Slovak Republic, targeting the field of studies appears only in the context of government scholarships. Policies to attract international students despite or particularly because of socio-economic factors are limited. The most common tools to do so are grants and scholarships, discussed below.

Admission process

In all OECD countries, a study permit requires proof of acceptance by a university, proof of financial means to support living expenses, and health insurance. Beyond these minimum requirements, the admission process differs between countries, and often also from one higher education institution to the next.

In the majority of OECD countries, university sponsorship is restricted to accredited institutions. In Australia, for example, applicants can only enrol in a full-time course registered on the Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students. In Denmark, applicants are restricted to publicly accredited educational institutions or specific state-approved programmes.

In most cases, verification of prior education is conducted by individual academic institutions as a condition for admission, rather than by migration authorities as a condition for issuance of the visa for studies. Several OECD countries, however, request verification of previous educational outcomes before issuance of residence permits. How this is done varies. For example, in Germany, public authorities require prior education to be provided by a state-recognised body of the home country. In France, credentials are inspected and authenticated by a national academic information centre.

Other policy changes simplify the admission procedure. In Spain, for example, since 2018, international students can fill out immigration forms from abroad and from within Spain, and task a representative to deliver their application, eliminating the obligation to go themselves to the consulate. In addition, authorisations to stay for studies in higher education institutions can be submitted by the institution itself. In this way, universities participate in the admission process of international students.

Duration of study permit

In about half of OECD countries, the study permit is issued for the full duration of studies (Table 6.2). In several of these countries, the permit is valid for a few months longer such as in Canada (+90 days), Latvia (+4 months), the Netherlands (+3 months), and the United Kingdom (+4 months, if the study course is longer than 12 months). In Japan, the period is designated individually by the Ministry of Justice and can be up to 4 years and 3 months. In Estonia, it can be between 12 months up to the entire duration of the study. In Lithuania, the permit is for the duration of studies but not longer than two years. In Poland, the first permit is valid for 15 months, but for three years upon renewal. In the rest of the OECD, the permit or visa is usually valid for about one year. In the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and Slovenia, the permit is valid for a maximum of one year or the duration of the study course, whichever is shorter.

Against this backdrop, international students in some countries have to renew their permit annually, while in others, the maximum duration for a single issuance of a permit is for many years (as for PhD studies in France, 60 months in Australia, 51 months in Japan). This does not mean that students once admitted do not need to provide proof of their study progress, but rather that they do not have to resubmit paperwork and pay fees for renewal or extension.

In about two-thirds of OECD countries, there is a limit on how long someone can hold a student permit (including renewals). This ranges from 3-5 years in the United Kingdom (degree vs below degree level) and 5 years in Australia to 10 years in Germany. Other countries fall in between, such as 6 years in the Slovak Republic, 7 years in the United States, and 8 years in Switzerland, where exceptions are possible. By contrast, in about a quarter of OECD countries, no such restrictions are in place, and a student visa can be prolonged as long as its conditions are met.

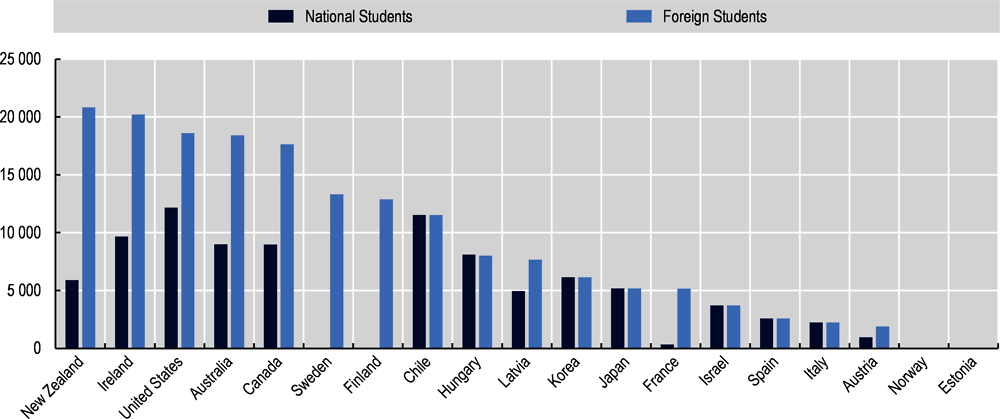

Tuition fees

In most OECD countries with available data, international students at public institutions pay different fees than national students enrolled in the same programme. Differences are most pronounced in France and the English-speaking OECD countries. In the latter, also nationals pay comparatively high amounts, but foreign students pay on average about twice or more the tuition fees charged to national students (Figure 6.1). By contrast, fees are identical for both foreign and national students in Chile, Italy, Japan and Spain. There are no tuition fees for any students at public universities in Norway.

Several European countries apply lower or no fees for EEA students but apply increased fees for those from outside the EEA. In Denmark, Finland and Sweden, higher education is tuition-free for nationals and EEA citizens, but international students from outside EEA countries are charged. While this policy has been in place for over a decade in Denmark (2006/07) and Sweden (2011), it was introduced only in 2017 in Finland. Similarly, France introduced a fee regime at public universities, which, as of 2019, applies different tuition fees to European and non-European students. From the start of the 2019/20 academic year, annual fees for a bachelor’s and master’s degrees increased more than 15-fold to EUR 2 770 for bachelor’s and EUR 3 770 for master’s annually for international students. In international comparison as shown above, they are nevertheless low and universities can waive part or all of the higher study fees for specific groups and may do so for a maximum of 10% of the total number of students (including national and European ones). Most French institutions grant exemption to international students coming from less developed as well as French-speaking countries (Campus France, 2019[1]). Other European countries that distinguish between EEA and non-EEA students include Austria, Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the Flemish Community in Belgium.

Australia, Canada, and Israel apply differentiated fees for national and foreign students. In Israel, the average tuition fees charged by public institutions for international bachelor’s students are more than three times the fees charged for national students.

In some countries, the tuition fees vary depending on the language of instruction, with higher tuition fees for programmes in non-national languages. For example, in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece and the Slovak Republic, international students studying in the national language pay the same fees as nationals. The concept of different study fees by the language of instruction is also applied in Hungary, Israel, Italy, Latvia, and Poland, though to varying degrees (Table 6.3).

Language requirements

International students in OECD countries typically need to demonstrate study language knowledge before enrolment (Table 6.3). In most countries, requirements and levels are set by the HEI or the academic programme via the enrolment procedure and not by immigration policy. In some countries such as Estonia and Hungary, however, proof of sufficient knowledge of the language of the study programme is required in the framework of the immigration procedure.

Only in a few countries are international students required to learn or attend classes in an official national language during their studies. These requirements are usually tied to scholarships. In Hungary, for instance, Stipendium Hungaricum beneficiaries have scholarships covering their tuition fees for studying in Hungary including for all English-taught programmes. However, scholarship holders need to study Hungarian language and culture as a subject in their first year. In Latvia, international students who have the Latvian State Scholarship are required to understand some degree of the Latvian language.

In almost all OECD countries that provided information on the subject, at least some full-degree programmes at public universities are offered in English. In most cases, English is the only non-national language that is available as the language of instruction in addition to the national languages. However, in some Eastern European countries, other offers exist. These include programmes in German and French in Hungary, in Russian in Lithuania, and in German, French, Russian and Hungarian in the Slovak Republic. Mexico is an exception in the OECD, as no full degree programmes at public universities are available in English. Notably, the English-speaking countries, here Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States do not offer full programmes in another language than their national language(s).

Many OECD countries have increased their offers of English language programmes over the last years. In Norway, for example, in 2020, 90% of undergraduate offers but only 44% at a higher degree are registered to be taught in Norwegian. In addition, while in 2011 just 11% of courses were registered with English as the language of instruction, this share had increased to 19% in 2020 (Diku, 2022[2]). In Sweden, 64% of all programmes at master’s level are taught in English. This is an increase of 26 percentage points from 2007 (Malmström and Pecorari, 2022[3]). In Italy, the number of programmes in English increased from 143 to 245 between 2013/14 and 2015/16 (Rugge, 2018[4]). In Israel, English-taught programmes offered have doubled for bachelor’s degrees, 25 instead of 13 in 2016, and increased by 25% for master’s programmes, 85 instead of 63 in 2016. The number of English-language degree programmes at German higher education institutions has increased more than six-fold from 258 (2008) to 1 550 (2020). The proportion of all degree programmes they account for also rose considerably during this period, from 2% to 8%, and the vast majority of these programmes (86%) were offered at the master’s degree level. In 2020, English-taught programmes accounted for 2% of bachelor’s degree programmes, but 14% of master’s degree programmes. In the Netherlands in 2018/19, about 28% of bachelor’s programmes at research universities were exclusively offered in English, and another 15% were offered in multiple languages. For master’s programmes, there were 76% offered in English only, and another 10% offered in multiple languages, typically Dutch and English. Engineering, liberal arts, and sciences master’s courses were only offered in English (Nuffic, 2019[5]). Also in cross-national surveys, and aside from the national language(s), English is the most frequent language of study, mentioned by four in ten respondents (38%) in a recent Eurobarometer on the topic. Analysing data from 19 European countries, Sandström and Neghina (2017[6]) report a 50-fold increase in the number of English-taught bachelor’s programmes in Europe.

Employability and labour market access during studies

In most OECD countries, the student permit automatically grants access to the labour market (Table 6.2). International students in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, and the United Kingdom do not require a separate permit for employment. In most other OECD countries, including Austria, the Czech Republic, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Switzerland, Türkiye, and the United States, international students need to obtain an authorisation, typically a work permit, before the start of their employment. In New Zealand, only some programmes qualify for part-time work rights. Likewise, in Israel, employment is only possible for a small group of international students, those enrolled in a high-tech related field of study. Colombia is an exception in the OECD, as the employment of international students is generally not possible.

Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, and Sweden are the only OECD countries where international students can work full-time during their study programme with no hourly restrictions, provided that this does not interfere with their study progress. In all other countries, labour market access is restricted in some way, most commonly via an hourly limit of work permitted during classes.

In about two-thirds of OECD countries, international students can only work part-time, when university courses are in session (Figure 6.2).4 In some countries, this limit is slightly more flexible such as 40 hours per fortnight in Australia, 60% of the statutory maximum for full-time employment in France, and 120 full days or 240 half days in Germany. In Austria, Denmark, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom, the maximum work hours depend on the study level, with stricter limits in place for lower levels of study. About half of the countries that apply an hourly limit to employment during academic terms lift this during academic breaks. This is the case in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In the Netherlands, international students can either work 16 hours per week during academic terms or full-time during the summer break from June to August.

Beyond an hourly limit, the second most common restriction is the sector of employment. For example, in Korea, international students who have obtained a part-time work permit must not work in a non-skilled sector, but are allowed to work in a skilled sector if the sector is related to their field of study, or translation. In Luxembourg and Mexico, the job must be related to the international student’s field of study. In the latter, work is only possible to carry out postgraduate and research studies. In France, the job must be related to the course of study if the work hours exceed the 60% limit.

Finally, specific requirements and restrictions are in place in some countries. For example, in Austria, employment permits for more than 20 hours per week require a labour market test. In the United States, off-campus employment is possible only after one year of studies through Curricular Practical Training (CPT) and only by sponsoring employers through co-operative agreements with the school; more than 12 months of full-time work under CPT precludes later use of post-graduate Optional Practical Training (OPT). In Switzerland, non-EU students are allowed to start working alongside studies only after 6 months of staying in the country.

Housing support and access to student loans and scholarships

In addition to labour market access, OECD countries can support international students also indirectly, via publicly subsidised student housing and access to public loans.

Access to publicly subsidised student housing is a common support measure in this context, at least in European OECD countries, as well as Japan and Korea. However, some specifications apply, often at the individual programme level. Regarding national policies, for example in Greece, undergraduate third-country national students have access to student dormitories in the same way as national students, but housing allowance is provided only to Greek and EU nationals. By contrast, access to subsidised housing is not available in English-speaking OECD countries, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

National students’ loans are only available to international students in the same way as to nationals in a few OECD countries. Partly this is because such a support system does not exist in all countries. Among the countries that do offer access to national students’ loans are Chile, Hungary, Italy, Mexico, and Switzerland. In Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Sweden, access to national student loans is only possible for EU/EEA nationals and only under certain conditions. In Estonia, an application to study loans is possible only for those with a long-term residence permit or permanent right of residence.

In about half of OECD countries, international students have access to public scholarships in the same way as national students do. This is the case in Austria, Chile, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Many countries offer public scholarships under a specific framework. An example is the Latvian State Scholarship, to which prospective students of over 40 eligible countries can apply based on bilateral agreements.

Family admission and their labour market access

Family reunification is an important factor to attract migrants and foster their integration into the host society. International students are no exception. In all but four OECD countries, partners of international students can join international students (Table 6.4). Only in Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Türkiye are international students not allowed to have spouses join them abroad as they move. Lithuania is the most open among these four, where partners can join international students after two years of residence, while PhD students can immediately reunite. In Luxembourg instead, only PhD students are allowed to reunite with their spouses/partners, and only if their contract is longer than one year. In Ireland and Türkiye, international students are not allowed to have their spouses join them at all. The terms and conditions of admission or reunification of partners of international students vary. For example, in the Czech Republic, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia, applications can be filed only after arrival. The specific type of visa (visitor, family reunification, or residence) and its duration differ as well.

In most OECD countries, partners of international students can work. In Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak Republic (after one year of residence), Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, they automatically have access to the labour market. By contrast, in Australia, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Mexico, Slovenia, and the United States, they must apply for a work permit, whose requirements differ by country. For example, in Australia, partners of international students need to pass a labour market test and Austria limits the number of hours spouses/partners are allowed to work. In other countries, income parameters apply, such as personal income thresholds in Finland and the Netherlands, while in the United States, the income earned by the spouse/partner must not be required for the financial support of the student visa beneficiary. Only in eight countries where partners can join international students, they are generally not allowed to work. This is the case in Chile, Colombia, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain.

Over the last decade, OECD countries have implemented wide-ranging policies to retain international students. These include options to change residence permits before graduation, (automatic) study permit extensions or specific post-graduation permits to search for, and start, a job. Other facilitating measures include facilitating employment by, for example, removing the labour market test. Some policies also foster long-term stay, for example when countries count (part of) the duration of study in the application process for permanent residence and naturalisation. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, some countries extended these policies to international students enrolled in full-time online courses.

In almost all OECD countries, international students can change their study permit to another residence permit already prior to graduation, provided they meet its requirements. In some countries, this is restricted to certain categories, such as only to family permits as in Luxembourg. Sweden requires international students to demonstrate proof of study activity and to have completed at least half a year of coursework (30 ECTS) prior to changing status to a permit for employment. In some countries, it may be difficult for students who have not graduated to qualify for any of the work permits available if they all require higher education qualifications.

Most OECD countries have policies to enable international students to stay on and look for a job upon graduation. However, access to and duration of these postgraduate extensions vary (Table 6.5). In Denmark, Estonia, Greece and Luxembourg, the extension of a study permit is automatic, without request. In some countries, international graduates can stay for a limited period, such as 60 days in the United States, three months in Poland, four months in Latvia (based on their study permit), but have to apply for an extension if they want to stay longer.

The post-graduate extension is typically between one and two years of duration (Figure 6.3). In some countries, the extension is tied to the duration of prior studies, such as in Canada, or to the level of the newly obtained qualification, as in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Notably, in all European OECD countries that transposed the EU Directive (2016/801), third-country nationals are allowed to stay for at least nine months upon graduation. In Finland, graduates can apply for the permit for job search within five years of the expiration of their residence permit for studies. Hence, international students can leave the country and still have favourable conditions to return to Finland for several years. A similar provision is in place in France, for up to four years after graduation. Mexico and Colombia are exceptions in the OECD, as they do not offer post-graduation extensions to international students.

International graduates can usually work to finance their living expenses during their period of job search. In some countries including Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden, international graduates have full labour market access during this period. In Japan, international graduates need to apply for a permit to engage in activities other than those allowed under the status of residence previously granted. In Denmark and the Slovak Republic, the employment is restricted to 20h/week, similarly to during studies, and likewise in France, it is restricted to 60% of normal working hours. New Zealand prohibits self-employment and employment in commercial sexual services. In Luxembourg, the job must be in graduates’ prior field of study. By contrast, in Austria, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, and Poland, work is not allowed while on a job search permit.

Countries also offer other forms of facilitation to employment for international graduates. For example, in Germany, after the job-seeking period, graduates are exempt from the labour market test, provided that their sector and qualification level of employment corresponds to their field and degree of study. In Italy, international graduates from an Italian educational institution are exempt from the annual quotas set on issuance of a residence permit for work purposes. In Austria, graduates who have at least completed a bachelor’s programme are exempt from passing the points system and can apply directly for the Red-White-Red Card to settle temporarily in Austria and to work for a specified employer. In the Slovak Republic, employers can employ international graduates without the need to apply for a work permit or a labour market test. Also in Finland, no labour market test is needed. In Lithuania, international graduates applying for a residence permit for work are exempted from the 1-year work experience requirement and the labour market test if they are applying within 2 years after completing their studies. In Belgium, international graduates can apply for a single permit from within the territory.

The time international students spend studying in the host country often counts fully or partially towards permanent residence or naturalisation. In Colombia, Denmark, Japan, Korea and Türkiye, study time counts entirely as residence for such purposes. In Switzerland, stays for study purposes are counted when, at the end of their studies, the foreigner has been in possession of a permanent residence permit for two years without interruption. For long-term residence under the EU Directive 2003/109/EC, at least half of the periods of residence for study purposes may be taken into account in the calculation of the five-year legal continuous residence requirement.5 This is reflected in the national legislation in countries that are covered by the Directive, for example, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia. The same conditions apply in these countries to the national permanent residence scheme. In Chile, international graduates can apply for permanent residency after only one additional year of stay in the country, so in total at after at least two years of stay in Chile.

By contrast, in several key destination countries, including France, Israel, Italy and Mexico, study years do not count towards permanent residence applications. This is also true in Sweden, except for doctoral students who can count the period with a temporary residence permit towards obtaining a permanent one. In Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, permanent residency is issued separately from residence requirements on a temporary status, so the question of counting years as a student is less relevant. However, in some countries, a period of international study or a national degree allow for favourable access for long-term stay (Box 6.1).

In Australia, international students who completed at least two academic years can earn 5 points (10 if in rural Australia) of the currently required 60 points pass mark to express their interest in migrating permanently. Engineering, accounting, and computer science graduates can complete a one-year Professional Year Program upon graduation, which earns them an extra five points in the skilled migrant visa points test.

In Canada, applicants to the high-skilled permanent migration programme earn additional points for their post-secondary Canadian education. What is more, the Canadian Experience Class is an immigration stream that allows those with just one year of Canadian skilled work experience to make an expression of interest, a pathway open to all those who have worked in the country on a post-graduation permit.

In Chile, international graduates can apply for permanent residency after only one additional year of stay in the country, so in total at after at least two years of stay in Chile.

In France, while all international students are allowed to stay in France for 12 months after the completion of their post-graduation or higher degrees from a French institute to look for employment, bilateral agreements with Benin, Burkina Faso, India, and some other countries extend this privilege to two years. Students who have left France may apply for this permit as well, within a maximum of four years from obtaining their diploma in France.

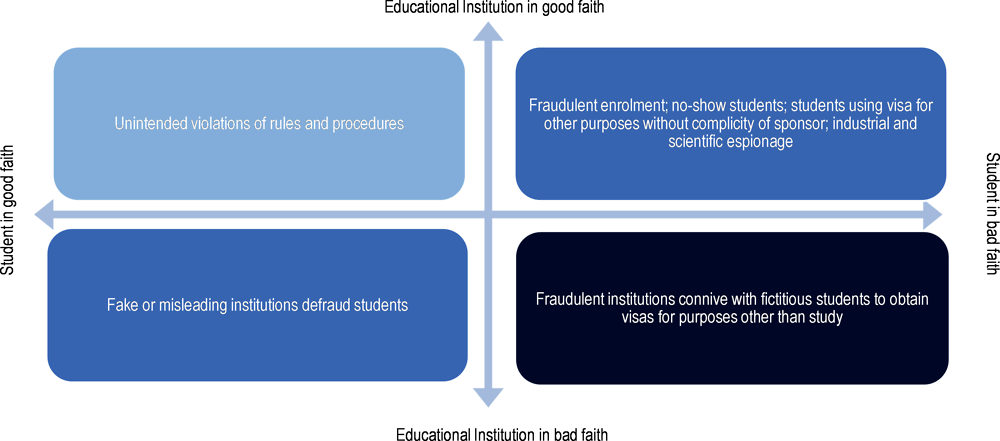

Alongside the arguments for expanding the number of international students and supporting their bridge to residence following study, there are also concerns about programme integrity and oversight of international student programmes. International student programmes can be misused by students, intermediaries and institutions in bad faith, for purposes other than those for which they were designed and for illicit gain. Even when institutions are in good faith, they can be defrauded or exploited by bad-faith students; even when students are in good faith, they can be duped into paying for programmes which are not legitimate (e.g. not accredited) or even fictitious (Figure 6.4).

Concerns in regulation centre on separate areas. These include misuse of the student visa, primarily to circumvent restrictions on labour migration, but also related forms of fraud. In addition, there is growing discussion of the risk to protection of intellectual property and strategic knowledge represented by international students conducting espionage. This section addresses the following compliance areas:

The risk of applicants for student visas use the visa to enter the territory and overstay after expiration, with no intention of ever studying;

The related issue of fraudulent or bogus schools, set up to defraud international students or to knowingly serve only as vehicles for visa issuance, conniving with students to sponsor a visa in exchange for payment;

The risk that applicants use the student visa to come to work, and remain in student status indefinitely while employed but not graduating;

The risk that legitimate students violate restrictions on employment by working excess hours or in jobs or locations not allowed under their status;

The risk that international students conduct technological or industrial espionage on behalf of their origin country or other malicious actors.

There are other concerns that countries may have about misuse of student visas, such as the potential for criminal or terrorist activity, but these are not specific to international student visas and apply to all admissions.

Issuing student visas only to bona fide students

Combating entry with no intention to take up studies – and the related risk of overstay – generally concentrates on pre-admission screening.

Even before a student applied for a visa, they must be enrolled in an institution. These sponsor institutions are expected, in return for “gatekeeping” privileges, to conduct reasonable verification of the good intentions of students. Indeed, the fact that it is often schools which verify the authenticity of documents attesting prior education means that risk management is partially delegated to them.

Many countries use not only accreditation but a separate system of recognised or ranked institutions granted rights to enrol international students. Usually these systems take into account the capacity of the school to support and report on students, as well as the observed behaviour of their students. A recognition or ranked sponsor system provides an incentive for schools to carefully review applicants to identify risk factors, rather than blindly enrol all applicants; if they can lose the privilege of sponsoring international students, they must exercise more care. In countries where international students are a significant source of income for higher education institutions there may be additional compliance mechanisms.

In the United States, HEIs must be approved by USCIS for attendance by F-1 foreign students. Only schools certified by the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) can enrol F or M non-immigrant students. Schools must meet recordkeeping, retention, reporting and other requirements to remain certified, as well as renew certification every two years. In Australia, HEIs must be in the Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS) in order to sponsor students; the Department of Education oversees this Register, although review and monitoring is conducted by state-level bodies. Registration is valid for up to seven years and can be renewed. The United Kingdom requires Student Sponsor Licences of education providers (previously Tier 4 Sponsors). Student Sponsor Licences are valid for four years and renewable. HEIs with the required rating in the pre-existing statutory education inspections generally qualify. Initially, applicants are probationary until they pass a first Basic Compliance Assessment. Since 2011, Korea has used a ranking system called the International Education Quality Assurance System (IQEAS) to ease document requirements for foreign students enrolling in these institutions. IQEAS is based on the share of overstaying and non-compliant students, as well as a subjective evaluation of the capacity of the institution to support international students (OECD, 2019[7]).

Fraudulent and bogus institutions are also a concern. It may not be sufficient to require accreditation if educational institutions can easily obtain accreditation. The approved sponsor requirements – which may involve an often expensive review process and ongoing auditing – is one means to filter out fraudulent institutions. Violations, as well as a record of poor compliance, lead to withdrawal of the right to sponsor students.

The proliferation of intermediary recruiting agents in certain origin countries, who draw a commission from the institution, means that there is a layer of agents with an incentive to place students with sponsor institutions in the destination country. Fraudulent institutions may take advantage of this ready supply of agents to enrol international students, and agents may seek institutions willing to sponsor bogus students. One notable operation to identify and combat this phenomenon was in the United States, where authorities created a fictitious university in 2013 – complete with accreditation – and waited for agents in origin countries to propose students. The operation concluded in 2016 with charges against these agents, who were aware that the institution was bogus but still enrolled more than 1 000 students. Some of these students may have believed they were attending a real institution, while others may have sought a visa allowing admission and access to employment.

Institutions may also be legitimate but exist primarily to place students into employment rather than to provide education. This has been a concern in a number of countries primarily with language schools, leading some (e.g. the United Kingdom, Ireland) to restrict labour market access to students enrolled in higher education institutions.

Once a potential student has enrolled, they still must apply for and receive a student visa. Proof of sufficient resources and insurance are generally required, subject to consular review. Document verification and in-person interview are the principal means used in European countries (European Migration Network, 2022[8]), although some may also contact HEIs to confirm enrolment and payment of fees. Language ability certificates may be checked, and some authorities even test language skills. The consulate may also require authentication of prior education documents. Rejection rates for visas show how consular review can lead to refusal of some applicants. The rejection rate varies widely among the countries that provided or publish official data. For instance, the rejection rate of study visas was 2% for Greece, for the period 2019-21, 7% in 2021 for Denmark, and 4% in 2021 in the Netherlands. In other OECD countries, rates are higher, with about 21% of student visas being refused in 2021 in Belgium, 40% in Canada, and around 40-50% in Sweden. Rejection rates may reflect many factors, including the accessibility and the complexity of the procedure, risk assessment approaches, and the types of programmes to which potential students apply. Therefore, they are not comparable across countries as an indicator of the level of scrutiny or the legitimacy of applicants, or even the ease of admission of international students.

Monitoring of compliance with educational progress

A key question for managing the migration of international students is monitoring that students comply with the conditions specified in their permit; the main concern is that the primary purpose of stay is to pursue education. To deal with the risk of use of the student visa for employment, without graduating, authorities require academic progress (Table 6.6) and impose a maximum stay (Table 6.2). These requirements are meant to ensure that students take their education commitments seriously.

Who is responsible for reporting and providing evidence of study progress varies between OECD countries. Only Sweden has no reporting requirements in place for institutions or students.

The HEI is responsible for reporting and providing proof of study progress in Australia, Denmark, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, the United Kingdom and the United States. In the United Kingdom, for example, a licensed sponsor must inform the Border Agency if a student does not arrive for their course, is absent or leaves the course earlier than expected. In the Slovak Republic, universities are obliged to inform the authorities in case a student has prematurely cancelled their study or has been repelled from the study.

By contrast, in Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Japan and Switzerland, the students themselves have to provide proof of their study progress. In Austria, this is due when students apply for an extension of the residence permit, when they must provide evidence of sufficient academic success (at least 16 ECTS per academic year). Similarly, in Israel, students must provide yearly written proof from the recognised educational institution of continued registration in order to renew their visa.

In Belgium, Canada, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal and Türkiye the monitoring obligation is shared. Thus, both the host institutions and the international students themselves have to report on study progress or if the conditions under which they received their permit have changed. For example, in Canada international students may be requested to complement the HEI report by providing evidence that they are enrolled in a designated learning institution and are actively pursuing their studies. In Belgium, the Immigration Office can send a demand for proof of continued progress to both the applicant or the HEI and they have 15 days to send in the required documents.

In almost all OECD countries, the student permit can be revoked during its duration for school-related reasons. The most common reason is the absence and discontinuation of studies. Some countries, such as Belgium, Latvia, Lithuania, and the United States, specify that a lack of progress may also be a reason for revoking the permit. The EU Students and Researchers Directive provides for the possibility to withdraw an authorisation if there is evidence that the third-country national is residing for another purpose than study. Also in Türkiye the permit can be revoked if there is evidence that the permit has been used for a purpose other than that for which it was granted. In Mexico and New Zealand a study permit cannot be revoked, although other administrative measures or sanctions may be in place.

Monitoring compliance with employment restrictions

In addition to checking academic progress, most countries also impose restrictions on employment to ensure that students focus on their education (Figure 6.2). The risk of working more hours than allowed, or in jobs not permitted by the work authorisation, may be difficult to address since it requires either reporting or data monitoring. In a number of countries, employers must report hiring, so it is possible for authorities to manually or automatically check if contract conditions comply with the restrictions of the student status. In the case of multiple employers of a single student, each contract may fall within maximum hours, but to check whether hours cumulatively exceed the limit, compliance checks must also sum hours worked in all job sites. If employers declare the employment relationship and pay social contributions, it may also be possible to use social security contribution information to assess whether hours are exceeded, although employment contribution data does not always contain hours worked. Illegal employment – undeclared by the employer, with or without the awareness of the student – is harder to detect.

The more complex the restrictions, such as in field of study or type of occupation, the more challenging the compliance effort. In the United States, for example, post-graduate Optional Practical Training must be in the major area of study; the institution is responsible for approving placements in employment and the extension of student status is contingent on this approval. It is only with inspections by field agents that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement identified cases where approval was given to placement in jobs outside the student’s area of study.

Preventing use of student visas to conduct espionage

Industrial and technological espionage using international students and researchers recruited by the origin country have become of increasing concern in some major OECD destination countries. Concern has focused primarily on students from China – in particular, from military-linked universities and from government-funded programmes for researchers sent abroad (CSET, 2021[9]; NIDS, 2020[10]). Transfer of technology – patents and intellectual property – is the main concern, both in military and civilian industries. However, misuse of student visas by others – such as Russians – performing military espionage and intelligence gathering has also been identified.

While much of the compliance check occurs in the visa issuance process, there are also measures taken by universities and research institutions to examine the source of funding for applicants and to report to the government on research activities in fields considered of strategic importance. Not all countries have specific reporting procedures. In the United States, students are required to disclose ties to military and government as part of their visa applications. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) published guidelines in 2021 for institutions to examine sources of funding for foreign researchers (National Science and Technology Council, 2021[11]). In the United Kingdom, the Academic Technology Approval Scheme (ATAS) requires students and researchers in certain fields and from certain countries to obtain an ATAS certificate in order to study or do research in the United Kingdom. In 2022, the national intelligence agency reported that 50 Chinese students left due to ATAS (MI5, 2022[12]).

There is a clear policy trend across OECD countries to attract and retain international students, and many countries have increased facilitations for international students by providing longer residence permits, broader employment opportunities, and easier transition to employment after graduation. International students who graduate are explicitly seen as a desirable component of labour migration inflows. The effect of these policies is to give greater gatekeeping power to higher education institutions, since their enrolment choices affect the downstream composition of migrants – potentially even crowding out other labour migrants when admission is subject to caps and ceilings. This gatekeeping responsibility has also meant greater compliance obligations to combat the misuse of student routes to circumvent migration regulations. It also means greater supervision of education institutions to ensure that none exploit this gatekeeping role. Further, the broader employment rights granted to students are often subject to complex restrictions, which can be difficult to enforce. While student migration is clearly of great benefit to the student, the host institution and the host country, this chapter has also noted some of the risks to the migration framework, with respect of labour market regulations, and even national security. These risks must be taken into account as countries compete to have the most attractive policies for international students.

References

[1] Campus France (2019), Introduction of differentiated enrolment fees for non-EU students. Comprehensive overview of the measure, https://www.campusfrance.org/en/droits-inscription-2019-2020-etudiants-internationaux (accessed on 19 April 2022).

[9] CSET (2021), “Assessing the Scope of U.S. Visa Restrictions on Chinese Students”, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) Issue Brief, Washington, DC., https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/CSET-Assessing-the-Scope-of-U.S.-Visa-Restrictions-on-Chinese-Students.pdf.

[2] Diku (2022), Dikus rapportserie 07/2021 Tilstandsrapport for høyere utdanning 2021, https://diku.no/rapporter/dikus-rapportserie-07-2021-tilstandsrapport-for-hoeyere-utdanning-2021 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

[8] European Migration Network (2022), EMN inform: Preventing, detecting, and tackling situations where authorisations to reside in the EU for the purpose of study are misused, European Migration Network, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

[3] Malmström, H. and D. Pecorari (2022), Språkval och internationalisering Svenskans och engelskans roll inom forskning och högre utbildning, Rapporter från Språkrådet, https://www.isof.se/sprakrapport19 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

[12] MI5 (2022), Joint address by MI5 and FBI Heads, MI5, London.

[11] National Science and Technology Council (2021), Recommended Practices for Strengthening the Security and Integrity of America’s S&T Research Enterprise, U.S. Government, Washington, D.C., http://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp. (accessed on 15 July 2022).

[10] NIDS (2020), “NIDS China Security Report 2021: China’s Military Strategy in the New Era”, National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS), http://www.nids.mod.go.jp/publication/chinareport/pdf/china_report_EN_web_2021_A01.pdf.

[5] Nuffic (2019), Incoming degree student mobility in Dutch higher education 2018-2019, http://www.nuffic.nl/en/publications/incoming-degree-student-mobility-in-dutch-higher-education-2018-2019 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

[7] OECD (2019), Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Korea 2019, Recruiting Immigrant Workers, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307872-en.

[4] Rugge, F. (2018), L’internazionalizzazione della formazione superiore in Italia., Fondazione CRUI, https://www2.crui.it/crui/crui-rapporto-inter-digitale.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

[6] Sandström, A. and C. Neghina (2017), “English-taught bachelor’s programmes Internationalising European higher education”, http://www.eaie.org (accessed on 6 May 2022).

Notes

← 1. This work was produced with the financial support of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. It includes a contribution by Hedvig Heijne (Consultant to the OECD).

← 2. Unless cited otherwise, data and policy evidence were collected via a questionnaire on international student attraction, admission and retention policies, from January 2022 as well as from the national reports of the OECD Expert Group on Migration.

← 3. Many examples in this section are based on a meeting of communications experts in June 2021, as part of the OECD Network of Communication Officers on Migration (NETCOM). Additional good practise examples can be found on the network’s website: https://www.oecd.org/migration/netcom/.

← 4. This is notably the case in all EU countries that transposed the EU Students and Researchers Directive, which specifies that students shall be able to work at least 15 hours a week.

← 5. In April 2022, the European Commission presented a proposal for a Recast Long-Term Residents Directive (COM(2022) 650 final). The proposal would fully count any period of residence spent as holder of a long-stay visa or residence permit for acquiring the EU long-term resident status. This will cover cases where a third-country national who previously resided in a capacity or under a status excluded from the scope of the Directive (e.g. as a student), subsequently resides in a capacity or under a status falling within the scope (e.g. as a worker). In those cases, it will be possible to fully count the periods of residence as a student, towards the completion of the five years period.