2. Governing and financing inclusive education

This chapter is about the governance and resourcing of inclusive education in Portugal. It analyses the country’s educational goals for diversity, equity and inclusion; the curriculum; the regulatory framework; the responsibilities and administration and the resourcing of inclusive education. Portugal started focusing on inclusion in education in the 1970s. It has developed one of the most comprehensive legal frameworks for inclusive education. The country has made significant efforts to respond to the needs of all students and grant more flexibility and autonomy to local actors. Many programmes and resources are now available to support equity and inclusion. However, challenges remain regarding the management of these resources and the administration of inclusive education. Also, the system is still mainly orientated towards the inclusion of students with special education needs. The chapter provides recommendations to overcome these challenges and strengthen the governance and resourcing of inclusive education.

Educational goals for diversity, equity and inclusion

Portugal has a specific history of inclusive education policies that has led to its current educational priorities. After the 1974 revolution, based on previous small and local experiments, more intensive efforts to integrate students with special education needs (SEN) in mainstream schools started in Portugal (Nogueira and Rodrigues, 2010[1]). In 1979, the national policy already stated that students with special education needs should, as far as possible, attend mainstream schools and that these schools should progressively readjust their structures to respond to these students’ needs (Alves, 2019[2]).

In parallel to the emergence of integration policies, parents and specialised staff created various private special education schools. About 100 of these institutions, called Education and Rehabilitation Cooperatives for Citizens with Disabilities (Cooperativa Educação e Reabilitação de Cidadãos com Incapacidades, CERCI), were formed, specifically dedicated to supporting and educating students with SEN in separate settings (Nogueira and Rodrigues, 2010[1]). Decree Law No. 319/19911 then established the right of children with SEN to attend mainstream schools. While inclusion emerged as an important orientation relatively early in Portugal, the inclusive education terminology was only adopted after the 1994 Salamanca Conference, which established the principle of inclusive education. However, inclusion was not fully integrated into school culture and remained mainly understood as the inclusion of students with SEN.

In 2008, there were approximately 10 000 students in 93 private special education schools. Within the logic that an inclusive system should, as much as possible, avoid separate provisions and equip mainstream schools to respond to diversity, the Ministry of Education (MoE) in Portugal started a dialogue with these special private schools. The MoE suggested that students and staff should be placed in mainstream schools, which should be supported in promoting the inclusion of these students. This consultation led to the elaboration of Decree Law No. 3/2008, 7 January, which defined the specialised support to implement in pre-school, basic and secondary education for the inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream schools. An agreement was made ensuring these separate private schools received funding from the MoE to intervene in public schools (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]). Most of these institutions thus became Resource Centres for Inclusion (Centros de Recursos para a Inclusão, CRIs).

While inclusion has been an important part of Portugal's education agenda since even before the 1990s, the focus largely remained until recently, almost exclusively students with SEN. However, over the last years, in particular, in the last three years, there have been major changes in education policy in Portugal. As in many OECD countries, trends such as an increase in the share of the population with an immigrant background and a shift towards accommodating diversity (Cerna et al., 2021[4]) have led to a greater recognition of diversity in Portuguese schools. There has been, for example, a steady increase in the share of students with an immigrant background and of identified students with SEN across regions in Portugal (see Chapter 1). Also, in PISA 2018 (OECD, 2020, p. 24[5]), nearly 55% of students responded that they have contact with people from other countries in schools, placing Portugal slightly above the OECD average. In this context, measures to promote students’ inclusion into the education system through access to the curriculum, educational success and ensuring their sense of belonging and self-worth have become core priorities.

The 22nd Constitutional Government's programme promotes an education policy that focuses on people, guaranteeing equity and quality. In particular, it states that “the public school is the main instrument to reduce social mobility inequalities. As such, schools must guarantee equality of opportunity in accessing a quality and inclusive education”.2

In line with these principles, policies and laws adopted at the national level have been increasingly orientated towards the inclusive education model, adopting inclusion in a broad sense as a cornerstone of educational policy and a key responsibility of the education system. Equity and inclusion principles inform national policy measures within the education system, particularly those that deal with the curriculum, assessment, school evaluation, continuing teacher professional learning and budgets.

Recent legislation on inclusive education requires the provision of support for all students to be determined, managed and provided within mainstream school settings. For example, local multidisciplinary teams to support inclusive education (Equipas multidisciplinares de Apoio à Educação Inclusiva, EMAEI, see Chapter 4) are formed within schools to support inclusion. They are responsible for determining what support is necessary to ensure that all students (regardless of socio-economic, cultural, linguistic, ethnic backgrounds and ability) have access and the means to participate effectively in education and be fully included in society. Furthermore, various national action plans and programmes support all students, especially those from diverse groups who are particularly vulnerable and at risk of dropout, such as students with special education needs, students from ethnic minorities (in particular, Roma communities) and students with an immigrant background.

Measures within the education system are designed and implemented at all levels - national, regional and local - so that all students have access to good learning conditions. The system promotes inclusion for all and the creation of a system-wide culture of inclusion that requires a shared commitment amongst staff at the national, local and school levels.

There has been an increasing trend towards local autonomy, which has been accompanied by new governance and accountability mechanisms. Ongoing reforms are leading to a growing intervention of municipalities in the field of education. There is a common assumption that there is not one single model of an inclusive school. Therefore, within the recent political orientation developed at the system level, schools have been granted more autonomy. Autonomy and curriculum flexibility, together with inclusion, are key concepts and principles in the design and implementation of curricula and educational activities. Significant effort is being made regarding personalisation, which involves giving individual attention to students and closely working with them. A strong development-orientated political commitment currently exists, which aims to reduce educational inequities and promote quality education and learning for all. There is also the possibility for schools to have up to 25% autonomy in managing the curriculum to respond to the needs and characteristics of their students and local context.

Curriculum reference documents and other essential documents developed at the central level, such as The Students’ Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling and Essential Learning described below, guarantee coherence within the education system. They guarantee the inclusive function of the school and guide them through a set of principles, values and vision, resulting from social consensus.

Curriculum

Since 2017, the MoE of Portugal has adopted a set of new documents that constitute the framework for the design and implementation of a 21st century curriculum. The national curriculum for primary and secondary education has changed according to three major guiding central documents: (1) the Students’ Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling (2017); (2) the National Strategy for Citizenship Education (2017); and (3) a set of documents, called the Essential Learning.

The Students’ Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling (Students’ Profile)

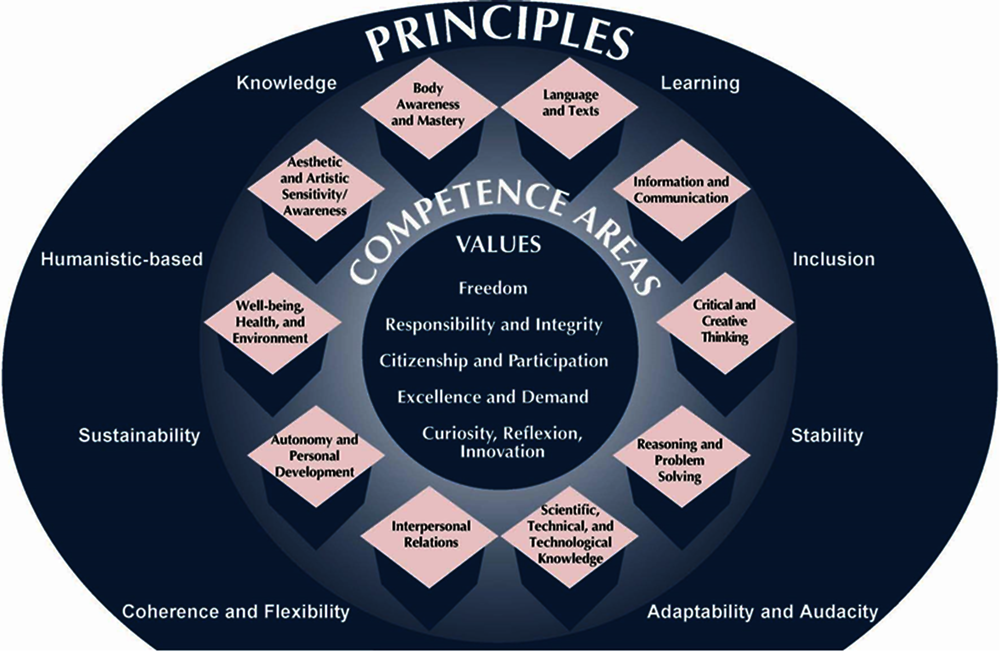

The Students’ Profile (Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória, Legislative Order No. 6478/2017, 26th June) is a reference guide for the whole curriculum, setting out the principles, vision and competence areas (academic, social and emotional competences) that students should have attained by the time they complete compulsory schooling. It is the matrix for decisions to be taken by educational managers and actors at the level of the bodies responsible for educational policies and schools. The purpose is to contribute to the organisation and management of the curriculum and to the definition of strategies, methodologies, and pedagogical-didactic procedures to be used in learning and teaching practices. It is the matrix for decisions to be used by educational stakeholders at all levels of the education system.

This document is the framework for curriculum development and the organisation of school activities. The broadness of the Students’ Profile respects the inclusive and multiple character of the school, ensuring that, regardless of the school pathways, all knowledge is guided by explicit principles, values and vision, resulting from social consensus (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

The principles and values outlined in the Students’ Profile’s conceptual framework (see Figure 2.1) mirror the humanistic-based philosophy on which the whole document is based. By referring to students in the plural form, it fosters inclusion and values diversity viewing each student as a unique human being. Therefore, the Students’ Profile leads to a school education on which the students of this global generation can build a humanistic-based scientific and artistic culture. It aims to help students: (1) mobilise values and skills that allow them to act upon the life and history of individuals and societies; (2) make free and informed decisions about environmental, social and ethical issues; and (3) carry out civic, active, conscious and responsible participation (d’Oliveira and al., 2017[6]).

National Strategy for Citizenship Education (ENEC)

The 2017 National Strategy for Citizenship Education (Estratégia Nacional da Educação para a Cidadania, ENEC3) was created to support children and young people to acquire citizenship skills, knowledge and values throughout compulsory education. The Strategy was developed in accordance with the Students’ Profile. In line with the ENEC, the national curriculum includes the Citizenship and Development subject, which promotes and reflects on the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion and encourages interdisciplinary activities.

This strategy aims to help students develop and participate actively in projects that promote fairer and more inclusive societies within the context of democracy and democratic institutions, the respect and defence of human rights, and respect for diversity and gender equality, environmental sustainability and health education. Enshrined in the 1986 Basic Law of the Education System (Law No. 46/86) and the Students’ Profile, the inclusion of this area in the curriculum recognises the school’s responsibility to provide adequate preparation for active and informed citizenship, as well as appropriate education to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals4.

The Essential Learning

In 2018, based on these two reference documents, the MoE developed the Essential Learning (Aprendizagens Essenciais, AE, established by Legislative Orders No. 6944-A/2018, of 19th July and No. 8476-A/2018, of 31st August). The AE are curricular orientation documents that describe the bases for the planning, realisation and assessment of each school subject for each year of schooling5 to Vocational Courses and Artistic Specialised Courses (Legislative Orders No. 7414/2020, of 24th July and No. 7415/2020, of 24th July). The AE were developed in consultation with teacher associations. When there was no professional teacher association constituted, this was undertaken by scientific societies and authors, allowing for the development of meaningful learning standards. The AE also facilitate interdisciplinary work, various assessment procedures and tools, the promotion of research, comparison and analysis skills, the mastery of presentation and argumentation techniques and the ability to work cooperatively and independently (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

School autonomy and curriculum flexibility

It is critical that schools and teachers make the main decisions at curricular and pedagogical levels, for instance by having greater flexibility in curriculum management, aiming to foster interdisciplinary work, in order to deepen, strengthen and enrich the Essential Learning by subject and year of schooling. As such, within Decree Law No. 55/2018, 6 July, schools are provided with up to 25% of curriculum autonomy in order to meet their specific needs by fostering pedagogical differentiation in the classroom, interdisciplinary work and project-based methodologies; creating new subjects; and allowing upper secondary students to choose their own course format by being able to swap and replace subjects within the scientific component of each course, among other measures.

In the scope of the School Autonomy and Curriculum Flexibility the MoE issued Ordinance No. 181/2019, of 11th June, which allows public and private schools, according to their autonomy and flexibility, to manage more than 25% of the curriculum by designing innovation plans. This Ordinance aims at facilitating the implementation of curricular and organisational innovation school plans based on the need to implement appropriate responses to curriculum and pedagogy to meet each educational community’s challenges and improve the quality of learning, the focus on meeting diverse learners’ needs and, ultimately, the success of all. Each innovation plan must be proposed and presented by each school and requires validation by the MoE.

Curricular accommodations

Students can benefit from curricular accommodations which aim to facilitate their access to the curriculum. Portugal implemented various tools to respond to the needs of students at risk of school failure and those from disadvantaged and diverse backgrounds who encounter difficulties in their learning. These tools are to be implemented in the classroom through diverse strategies, including the diversification and appropriate combination of various teaching methods and strategies, diversified and inclusive assessment strategies and the removal of barriers in the organisation of space and equipment. In other words, curriculum adaptation strategies are designed to respond to the different learning styles of every student and promote their educational success (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]). The main curricular adaptation programmes and strategies are the following:

Education and Training Courses (CEF)

The Education and Training Courses (Cursos de Educação e Formação - CEF) were first implemented during the school year 2004/2005. They aim at supporting young people who:

CEFs are mainly aimed at young people aged 15 or over but are also offered to students under 15 in exceptional circumstances. The courses have a specific curriculum design, tailored to the profile and individual features of each student. They provide academic and/or professional certification at different levels, depending on the student's starting point.

Education and Training Integrated Programme (PIEF)

Created in 1999, the Education and Training Integrated Programme (PIEF)6 is an exceptional measure for students up to 15 years old in a situation of abandonment that has been redesigned over the years. The PIEF is a socio-educational measure, of a temporary and exceptional nature, to be adopted after all other school integration measures have been exhausted. It aims to promote the fulfilment of compulsory education and social inclusion, granting a qualification in a second or third school cycle. The programme aims to reintegrate students into education and promote the completion of compulsory education and/or integration into the labour market. Each student is specifically targeted through the development of an Individual Education and Training Plan. It differs from Education and Training Courses (CEF) in that it does not confer double academic and professional certification. The two also differ in terms of curriculum and study scope. The main objective of PIEF is to recover students who have left the education system early.

Distance learning (ED)

Drawing on a previous educational provision entitled Mobile School (Escola Móvel) in 2005, distance learning (Ensino a Distância, ED)7 formally became an official educational provision in 2014 through Ministerial Implementing Order no. 85/2014, of the 14th April, which was repealed by the Ministerial Implementing Order no. 359/2019, on the 8th October. Distance learning aims to adapt an educational and training offer to students for whom face-to-face teaching is not possible. A virtual education platform was put in place for:

Student-athletes attending distance learning in the network of schools with High Performance Support Units at School.

Students integrated in social solidarity institutions that establish cooperation agreements with the ED school.

Students with health problems or physical conditions that limit their regular attendance at school.

The ED aims to ensure equal access to education, stable educational paths, quality learning, and students' educational success in the above circumstances. It is offered from the second cycle of primary education until the end of secondary education. It provides an organisational, curricular, pedagogical and learning structure suitable for this type of teaching, functioning on a b-learning model.8 Both b-learning and e-learning models are used in distance learning. However, students have to attend some face-to-face lessons, namely Physical Education. Students usually attend these lessons in a nearby school.

Alternative Curricular Pathways (PCAs)

Alternative Curricular Pathways (Percursos Curriculares Alternativos, PCAs)9 were implemented in 2006. They are specific educational provisions for exceptional circumstances, which require prior authorisation from the MoE. These pathways target students who have repeated years in the same cycle and are at risk of early school leaving, or experience school or social exclusion. PCAs are adapted to the profile and specific needs of each student. They are part of a re-orientation strategy and aim at facilitating inclusion into mainstream education.

Currently, PCAs are integrated into innovation plans established by Ordinance No. 181/2019, of the 11th June, altered by Ordinance No. 306/2021, of 17th December. Within the scope of their curricular autonomy and the principles that underpin innovation plans, a school can design PCAs if: (1) it identifies a group of students from the same year of schooling who require specific and temporary management of the basic curricular matrix; and (2) none of the existing educational and training offers proves to be adequate. These innovation plans, of which PCAs are part, are submitted to the MoE for analysis and approval.

Portuguese as a Second Language (PLNM)

Some measures have been implemented to respond to these challenges to improve access and inclusion of newly arrived students with an immigrant background and, more recently, of refugee students (see Box 2.1), in primary and secondary education. Data from PISA 2018 show that in Portugal, 33.2% of first-generation and 23.5% of second-generation students with an immigrant background do not speak the language of instruction at home. Evidence shows that students who do not speak the language of instruction at home might face significant challenges in accessing the curriculum and feeling that they belong (OECD, 2019[8]; European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019[9]).

To promote the inclusion of students with an immigrant background who recently arrived in the Portuguese educational system, the MoE implemented measures to support the acquisition of the Portuguese language. These students are offered the school subject Portuguese as a second language (PL2 or Português Língua Não Materna, PLNM), in primary and secondary education (ISCED 1, 2 and 3). The objective is to ensure that all students who are non-native Portuguese speakers are offered equal conditions to access the school curriculum and achieve educational success. The idea that schools “must provide specific curricular activities for students whose language is not Portuguese to learn Portuguese as a second language” first emerged in 2001 with Decree Law No. 6/2001, 18 January. The PNLM subject was created a few years later, in 2006 (Ordinance No. 7/2006) in basic schools and in 2007 (Ordinance No. 30/2007) in secondary schools. It was strengthened with Decree Law No. 139/2012 that requires PNLM to be a mandatory part of the curriculum (Oliveira, 2021[10]).

The PL2 offer is taught in ISCED 1 and 2 (primary and lower secondary education - year 1 to year 9) in most education and training courses, including sciences - humanities courses and specialised artistic courses in ISCED 3 (upper secondary education – year 10 to year 12) as well as professional courses with dual certification at the secondary level10.

All public primary and secondary schools in the Portuguese educational system offer these measures. Based on language assessment through interviews and placement tests, students are placed depending on their language level (A1, A2 or B1, according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFR). They can benefit from PLNM classes for the development of the Portuguese language and follow a specific PL2 curriculum. Immigrant students with a B2 or C1 level follow the Portuguese subject as described in the national curriculum and can benefit from additional language support classes. Furthermore, students placed at the A1, A2 and B1 language levels can also benefit from specific assessment criteria in the PLNM subject, as well as final exams of PLNM, which correspond to their language level instead of the regular final exams of the Portuguese subject.

During the 2018/2019 school year, there were 3 487 students attending PNLM classes, fewer than in 2017/2018 (3 922) although 1.3 times more than in 2015/2016 (2 644) (Figure 2.2). In 2018/2019, 86.6% of PLNM students were enrolled in basic education, and 17.4% of them were in secondary education. Moreover, the same year, 48% were girls, and 52% were boys (Oliveira, 2021[10]).

Also, within the scope of the Decree Law No. 54/2018, other specific educational measures, such as universal, selective and/or additional measures can be applied by each school to support immigrant students placed at level A1 to ensure their access to the curriculum and inclusion.

Since the 2015/16 school year, the MoE has developed a set of extraordinary educational measures for foreign non-accompanied minors (menores estrangeiros não acompanhados, MENA). These measures aim to welcome refugee or asylum seeker non-accompanied students by supporting progressive access to the national curriculum and ensuring their educational success. It reinforces support for PLNM classes and provides specific educational measures. These include simplifying the process of academic degree recognition, progressive integration in the curriculum (through the adaptation of the school calendar and separate small group classes to reinforce learning) and School Social Assistance (Ação Social Escolar, ASE). In 2020, the Directorate-General for Education (Direção-Geral da Educação, DGE) and the National Agency for Vocation Education and Training (Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Professional, ANQEP) created a “Welcoming Guide” (Guia de Acolhimento) to help officials and school staff implement the appropriate measures.

Various entities from the different ministries collaborate to welcome unaccompanied children and youth to ease the inclusion of these children and youth in the Portuguese society and schools.

Source: DGE and ANQEP (2020[11]), Menores Estrangeiros Não Acompanhados (MENA) - Guia de Acolhimento: Educação Pré-Escolar, Ensino Básico e Ensino Secundário [Unaccompanied Foreign Minors (MENA) – A Welcoming Guide: Pre-school, Basic and Secondary Education ], http://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Projetos/Criancas_jovens_refugiados/guia_acolhimento_mena_agosto2020.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

Regulatory framework for diversity, equity and inclusion in education

The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic establishes that:

“[t]he State promotes the democratisation of education and other necessary conditions, for education, realised through the school and other educational means, to contribute to equal opportunities, the overcoming of economic, social and cultural inequalities, the development of personality and a spirit of tolerance, mutual understanding, solidarity and responsibility, for social progress and democratic participation in collective life.”11

As mentioned above, Portugal has undertaken major changes to reform its education system. While one of its main focuses was the inclusion of students with SEN into mainstream education from the 1970s, the new regulatory framework established in 2018 has broadened the approach to inclusive education. Moving away from the one-dimensional approach to inclusion in education as the mere participation of students with SEN in mainstream schools, the new legislation adopted a vision that implies developing equitable quality education systems by removing barriers to the “presence, participation and achievement of all students in education” (Ainscow, 2005, p. 119[12]). Following international standards, inclusion in education in Portugal is seen as a process in which the education system has to adapt to the needs of all students, and all students should attend mainstream education as much as possible. According to this approach, a new set of legal instruments has been developed (see Table 2.1).

The Law for Inclusive Education - Decree Law No. 54/2018

Decree Law No. 54/2018 (to which amendments were introduced by Law No. 116/2019, 13 September) entered into force following a rigorous evaluation process of the past ten years’ policies and practices and a broad national consultation in 2017. The proposal of the new Law on inclusive education was elaborated by a taskforce that listened to multiple stakeholders searching for the best solutions from didactic, pedagogical, health, education and social inclusion perspectives. The draft of the Decree Law was submitted to public consultation between July and September 2017, with broad participation of stakeholders, including public and private educational establishments, teachers' associations, professionals of the educational community, professional associations, parents and guardians’ associations, representatives of persons with special education needs, federations, trade unions and individuals in general. Also participating were the National Council for Education, the Council of Schools, the Association of Schools of Private and Co-operative Education, the Portuguese Co-operative Confederation, the National Confederation of Solidarity Institutions, the Union of Portuguese Misericórdias and the Union of Portuguese Private Health Insurances. The political organs of the Autonomous Regions were also consulted (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

It establishes the principles and regulations that ensure inclusion as a process by which the education system must adapt to respond to the diversity of needs and capabilities of each student through increased participation in the learning processes and educational community. According to the law, inclusive education has eight main principles that must guide its implementation: (1) Universal education; (2) Equity; (3) Inclusion; (4) Customisation; (5) Flexibility; (6) Self-determination; (7) Parental involvement; and (8) Minimum interference.

Equity, as one of the core principles of inclusive education, must guarantee that all students have access to the necessary support to achieve their learning and potential, while inclusion is the right of all children and students to access and participate fully and effectively in the same educational contexts. In this sense, schools, and more broadly the education system, must adapt to respond to the needs of each student, valuing diversity and promoting equity and non-discrimination in accessing the curriculum and the different levels of education.

Furthermore, the new law on inclusive education reflects a move away from the rationale that it is necessary to categorise to intervene. This means that there is no need to categorise students based on personal characteristics or establish a formal diagnosis of special education needs to provide specific support. Rather, it seeks to ensure that all students can access the curriculum and realise the Students’ Profile. Providing relevant support can be realised through reasonable accommodations, i.e. differentiated learning paths that allow each student to progress in the curriculum in a way that ensures their educational success. Therefore, Decree Law No. 54/2018 abandons categorisation systems for students, including the categories associated with special education needs. By doing so, it removes the restricted concept of “support measures for students with special education needs”. Instead, it takes a broader view, implying a whole school approach, which considers multiple dimensions and the interactions between them. It aims to end segregation and discrimination based on diagnosis or clinical labels, as well as suppress special education legislation.

Under this approach, there is a need to evaluate the reasons why students encounter difficulties in the learning process, both taking into account the students themselves and their context (e.g. need for additional support, poor teaching, inappropriate curriculum, inadequate resources, socio-economic factors). Support is no longer the exclusive responsibility of a specific professional considered as a "specialist". Rather, a broader and systemic approach to support is adopted, considering all factors that increase a school's ability to respond to diversity. In this sense, building support networks within and between schools as well as between the school and its community is needed.

Every student has the right to receive adapted measures to support their learning and inclusion process and to specific resources that might be mobilised to meet their educational needs in all education and training offerings. The law distinguishes between three broad types of measures to support students (see Table 2.2).

The Decree Law for inclusive education emphasises the responsibility of schools to identify barriers to individual students’ learning and develop diverse strategies to overcome them. The law calls for a change in school culture and encourages multi-level and multidisciplinary interventions (see Chapter 4) to support all students who need additional support for their learning. To support the implementation of the Decree Law, meetings and training opportunities have been offered to school boards, teachers and other staff (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

The Law for Curriculum flexibility – Decree Law No. 55/2018

An increasing number of OECD countries implement measures to have greater flexibility in curriculum management. A recent OECD report covering OECD and non-OECD estimates that 61% of participant countries allow local flexibility on curriculum content, pedagogies or assessment (OECD, 2021[13]). In Portugal, since Decree Law No. 55/2018, schools’ autonomy allows a flexible management of the curriculum and of the learning spaces and schedules, so that the methods, timing, instruments and activities can respond to the singularities of each student.

Schools have greater flexibility in curriculum management, which aims to foster interdisciplinary work to strengthen the competence areas set out in the Students’ Profile and deepen the Essential Learnings. As such, within Decree Law No. 55/2018, schools are provided with up to 25% of curriculum autonomy to meet their specific needs by fostering pedagogical differentiation in the classroom, interdisciplinary work and project-based methodologies; creating new subjects; and allowing upper secondary students to choose their own course format by being able to swap and replace subjects within the scientific component of each course, among other measures (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

The Decree Law requires the creation of school-based strategies for implementing flexibility and autonomy as key concepts in the design and implementation of curricula and educational activities organisation, giving increased autonomy to schools in order to design and shape their curriculum options so that teaching and learning are meaningful and beneficial for all their students and their specific contexts. Decree Law No. 55/2018 on Curriculum Autonomy and Flexibility was established at the same time as the Decree Law No. 54/2018 on Inclusive Education. Through these legal documents, schools are encouraged to change their organisational and pedagogical practices, according to the Essential Learnings, to ensure that all students acquire the competences set out in the Students’ Profile.

Decree Law No. 55/2018 also sets out the curriculum for primary, lower and upper secondary education, as well as the guiding principles for the design, implementation and evaluation of the learning process to ensure that every student acquires the knowledge and develops the skills and attitudes, which contribute to the achievement of the competences outlined in the Students’ Profile. In line with the ENEC, the Decree Law No. 55/2018 enacts the mandatory creation of school-based strategies for the implementation of a specific curricular component, Citizenship and Development. This aims at developing a broad range of active citizenship competences deemed essential for any young person to achieve before they reach the age of 18.

The Decree Law was completed by Ordinance No. 181/2019, 11 June, altered by Ordinance No. 306/2021, of 17th December, which allows public and private schools to potentially manage more than 25% of the curriculum. The Ordinance aims at:

Further facilitating the implementation of curricular and organisational innovative school plans based on the need to implement curricular and pedagogical appropriate responses to meet each educational community’s challenges

Improving the quality of learning, the focus on meeting diverse students' needs and, ultimately, the success of all.

To gain the possibility of managing more than 25% of the curriculum, school must design and present to the MoE an innovation plan, focused on curriculum and pedagogical innovation. In the school year 2020/2021, 103 schools implemented innovation plans.

To support and monitor the implementation of this curriculum autonomy and flexibility (Autonomia e Flexibilidade curricular, AFC) in all public schools, regional AFC teams were created. The members of these teams come from different entities of the MoE to ensure proximity to the field.

Responsibilities for and administration of inclusive education

Portugal is a semi-presidential republic, which joined the European Union (EU) in 1986. The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic (1976) governs the separation of powers into the legislative (the Assembly of the Republic), the executive (the Government) and the judiciary (the Constitutional Court as well as Administrative, Civil and Criminal Courts) branches. The President of the Republic – elected every five years – is the State’s Chief, whose duties are to represent the country, as well as supervise and guarantee the regular functioning of democratic institutions. The President is also vested with the responsibility of commanding the Armed Forces, approving or vetoing legislation and nominating the Prime Minister, after approval of the Parliament. The Parliament (Assembleia da República) is composed of 230 members who are elected by popular vote every four years (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]).

The executive power in Portugal is shared across two administrative tiers: central and local. The central government is divided into executive departments headed by their respective ministers who are nominated by the Prime Minister. The local level is sub-divided into municipalities (concelhos) and civil parishes (freguesias). Each municipality has executive and deliberative representation. The Municipal Chamber, composed of a President – the mayor – and other elected members (vereadores) acts as the executive body, whereas the Municipal Assembly supervises all municipal activity. At the sub-municipal level, civil parishes are governed by a Council of parishes (junta de freguesia) and an Assembly. The Portuguese Constitution established a political division of Portugal into Portugal Mainland and two Autonomous Regions, the Azores and Madeira, which have autonomous power over several areas, including education. Portugal Mainland is divided into five continental regions (North, Centre, Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Alentejo and the Algarve). However, no formal regional administration exists on the Continent. The five continental regions have no governance power and are only used for statistical purposes.12 Instead, Supra-municipal administration is generally provided by such entities as Metropolitan Areas, Regional Co-ordination and Development Commissions (Comissões de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional, CCDRs) or inter-municipal communities (comunidades intermunicipais, CIMs), which often have intertwining and overlapping functions.

Most regional approaches are related to the use of EU Structural and Investment Funds, put forth in the Partnership Agreement with the EU for 2014-2020. The five statistical territorial regions in continental Portugal – and to which the Review refer – are the North (Norte), Centre (Centro), Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Área Metropolitana de Lisboa), Alentejo and Algarve.

A centralised system

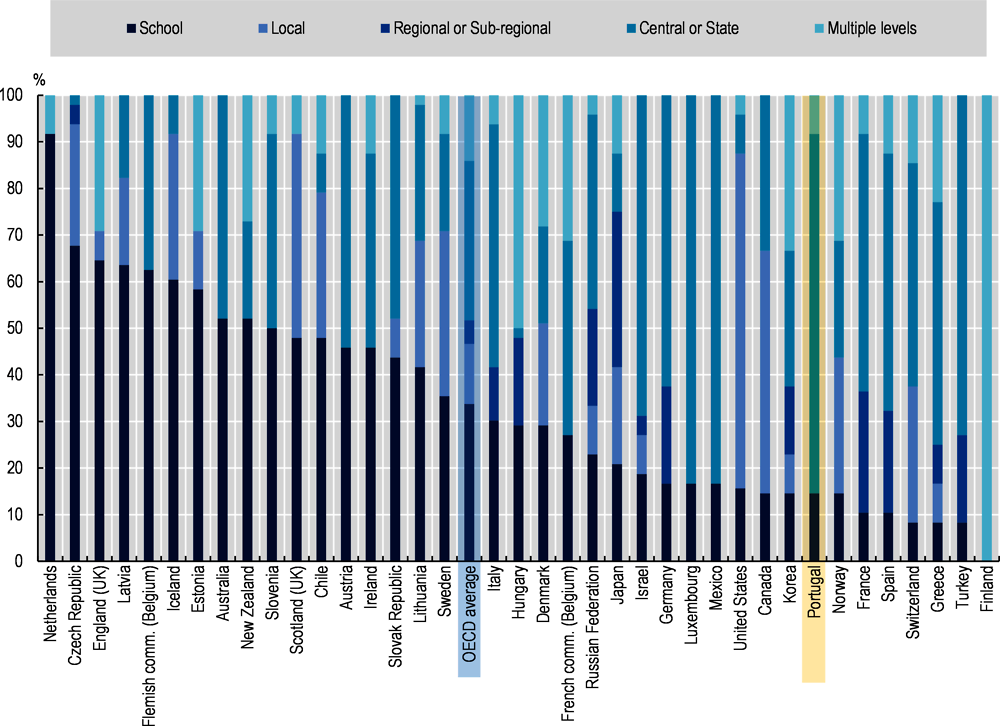

Governance in Portugal is highly centralised. Decisions about education policy are made at several levels of government, although a majority are made at the central level. Figure 2.3 shows that in 2017 in Portugal, 77% of decisions in public lower secondary education were made at the central level, only 15% at the school level, and 8% at multiple levels of government. This was below the OECD average of 34% for decisions made at the school level. At that time, Portugal had the second highest most centralised education decision-making of OECD countries and economies (OECD, 2018[15]).

There are multiple stakeholders involved in the functioning of the educational system at the national level (see Table 2.3). At the central level, government bodies under the MoE are the main ones responsible for managing the education system. Among others, they ensure the design and implementation of laws and policies, the creation of a common curriculum, the management of public schools, including vocational education and training (VET) and their regular evaluation. Entities that are part of the Portuguese MoE are the Directorate-General for Education (DGE), the Directorate-General for School Administration (DGAE), the Directorate-General for Schools (DGEstE), the Directorate-General for Statistics of Education and Science (DGEEC) and the Inspectorate-General for Education and Science (IGEC).

The Directorate-General for Education (Direção-Geral da Educação, DGE) is responsible for the management of the curriculum and the production of curricular reference documents for general education and out-of-school education to be developed by all schools at the national level (from pre-school to ISCED 3). In this vein, the DGE is responsible for the support and monitoring process regarding the implementation of education policies. Moreover, it is also responsible for the conception and management of specific programmes regarding school achievement.

The Directorate-General for School Administration (Direção-Geral da Administração Escolar, DGAE) ensures the implementation of policies for the strategic and efficient management of human resources in education. It guarantees the development of the human resources allocated to public educational structures. DGAE also responsible for the management of the teaching workforce and the organisation of school leadership, including recruitment and selection, career progression, remuneration and training.

The Directorate-General for Schools’ (Direção-Geral dos Estabelecimentos Escolares, DGEstE) mission is to ensure the regional implementation of administrative measures and the exercise of peripheral competences related to the MoE, without prejudice to the competencies of the other central services. It has decentralised services with a regional scope. Some of its competencies involve monitoring, coordinating and supporting the organisation and functioning of schools and the management of their human and material resources, as well as promoting the development and consolidation of their autonomy. It is also responsible for the co-ordination with local authorities, as well as public and private organisations involved in education in order to strengthen local interactions and support the development of good practices. DGEstE's follow-up work is carried out in collaboration with schools, teachers, parents and the entire educational community.

The Directorate-General for Education and Science Statistics (Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência, DGEEC) is a central service under the State's direct administration, with administrative autonomy that operates under the purview of the MoE and the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (MCTES). The DGEEC’s mission is to guarantee the production and statistical analysis of education and science. To create and ensure the proper functioning of the integrated information system of the MoE, DGEEC provides technical support for policy formulation, strategic planning and operations. Also, DGEEC observes and evaluates the overall results obtained by the educational, scientific and technological systems in co-ordination with other services of the MoE and MCTES.

The Inspectorate-General for Education and Science (Inspeção-Geral da Educação e Ciência, IGEC) has a specific law that details its organisational framework and states its role within the education system. Inspection activities range from the supervision of legal compliance to school external evaluation. In addition, there are many other activities the Inspectorate can perform, such as monitoring schools’ performance, administrative and financial audits or even disciplinary proceedings against individual staff. Schools are inspected regularly (often more than once a year), although inspections can fill different purposes. IGEC gives significant attention to schools’ culture, specifically to how they promote equity and inclusion. It recently modified its reference framework for evaluation by adding indicators to assess how the management of the school promotes the development of an inclusive education culture.

Portugal also created the National Agency for Qualification and Vocational Education and Training (Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e o Ensino Profissional, ANQEP). ANQEP is a public institute under the indirect administration of the State, with administrative, financial and pedagogical autonomy. The ANQEP has superintendence and joint supervision of the Ministry of Education and Labour and the Ministry of Solidarity and Social Security, in co-ordination with the Ministry of Economy and Digital Transition. Its mission is to contribute to improving the qualification levels of young people and adults in Portugal.

Undergoing a decentralisation process

As explained above, in Portugal, the core institutional actors at the local levels are the municipalities. There are no decision-making authorities at the regional level, except for the Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira. The municipality is also a territorial unit endowed with legal personality and a certain administrative autonomy, led by its political and administrative bodies, namely the Municipal Assembly - legislative body - and the City Council - executive body. While central entities remain the main decision-making bodies, Portugal has intensified its decentralisation process in recent years, giving increasing responsibilities to municipalities in the field of education. The ongoing decentralisation process has encouraged the transfer of some decision-making and responsibilities to municipalities. These responsibilities include the areas of school social assistance, recruitment and management of some human resources (non-teaching staff), as well as curricular enrichment activities, facilities and the management of pre-school and basic education (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

Decentralisation became a dominant paradigm in the 1980s (Lima and Franca, 2020[16]). The Portuguese Education Act, established by Law No. 46/86, was the first major tool that established the reform of the role of the state in education. The act states that the education system must be organised in ways that that “decentralise and diversify the structures of the educational actions” (Art. 3). According to Santos, Rochette Cordeiro and Alcoforado (2018[17]), while the 1976 Constitution already recognises the role of municipalities, it is in 1999, with the Law No. 159/99, that the principles of administrative decentralisation and local power autonomy started to be realised. The law established the framework for the transfer of responsibilities to local authorities, delimiting the intervention of the central administration. It also reinforces principles enshrined in the Education Act by requiring municipalities to participate in the planning and management of educational equipment and infrastructure (in pre-school and basic education). A year before, in 1998, Decree Law No. 115-A/98, 4 May, was enacted. It approved the regime of autonomy, administration and management of pre-school, basic and secondary schools. This normative framework, with cuts from municipal initiative, also foresaw the creation of Local Education Councils (CLE), conceived as structures of participation of the various agents and social partners for the articulation of educational policy with other social policies, mainly in terms of socio-educational support, organisation of complementary curricular activities, school network, timetables and school transport. These councils were conceived as structures of participation and collaboration for various actors and social partners in order to articulate educational policy with other social policies, mainly in terms of socio-educational support, organisation of complementary curricular activities, school network, timetables and school transport (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

Nonetheless, little change happened in practice until Decree Law No. 7/2003, 15 January, was enacted (Santos, Rochette Cordeiro and Alcoforado, 2018[17]). This Decree Law introduced a diploma that requires the Constitution and functioning of Municipal Councils of Education (Conselhos Municipais de Educação, CME). The CMEs are essential entities that concretise the institutionalisation of the intervention of educational communities at the municipal level. The same legal act also introduced the Educational Charter (1st generation), which is a fundamental instrument for organising the education network and teaching offers. The contracts for the transfer of competences between state and municipalities, established in Decree Law No. 144/2008, 28 July, defined the conditions for the transfer of the management of non-teaching staff in pre-schools and basic schools, of curricular enrichment activities in lower primary education and the management of public school facilities in upper primary and lower secondary education.

A few years later, an inter-administrative contract for the delegation of competences was signed under Decree Law No. 30/2015, 12 February. This Decree Law established the system of delegation of competencies to municipalities and inter-municipal entities in the field of social functions. Among other elements, this set a general programme for transferring responsibilities in education and better collaboration between the MoE (central level), municipalities (local level) and schools. Recently, Decree Law No. 21/2019, 30 January, reinforced and consolidated the framework for transferring power and competences to local authorities. It reinforces the areas that have, to some extent, already been decentralised. It gives the municipality new local and inter-municipal competences in the fields of planning, investment and management of education. However, the definition of the educational network, in conjunction with municipalities, inter-municipal entities and school clusters and non-clustered schools, as well as the decision on contracting or assigning creation and maintenance, remains within the competences of the MoE.

Furthermore, the competences of local authorities in the field of investment, equipment, conservation and maintenance of school buildings are now extended to all basic education and secondary education. The provision of meals in cafeterias of upper primary and secondary schools is now managed by the municipalities. Allocation of subsidies and/or provision of support and services by or contracted by municipalities are complementary to those available in schools. Furthermore, the responsibility for the recruitment, selection and management of non-teaching staff, of all levels and teaching cycles, is now ensured by the city councils. Consequently, this responsibility covers and reinforces the legal and functional mechanisms already enforced in the completion contracts.

In the area of security, the municipalities have also acquired, in conjunction with the security forces present in their territory and with the administrative and management bodies of clusters of schools and ungrouped schools, the competencies of organising the surveillance and security of educational equipment, namely the building and exterior spaces included in their perimeter.

Finally, as the highest expression of territorialisation, the municipal education council is an institutional body of intervention, leading consultation and debates to advance educational policy. Its composition has now been extended and includes, in addition to the members who already belonged to it, a representative of the co-ordination and regional development commissions, a representative of each of the pedagogical councils of the groupings of schools and non-grouped schools and a representative of social and solidarity sector institutions that develop activities in education.

Central policies and programmes for diversity, equity and inclusion in education

Many educational policies and programmes implemented in the last two decades in Portugal are aligned with equity and inclusion principles described above. They are designed to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds, promote school success and respond to Portugal’s current educational challenges, including grade repetition and early school leaving. The primary policies and programmes that allow for adaptation of and support to learning processes for students or groups of students are described in this section.

School Social Assistance (ASE)

Implemented in 1971, the granting of School Social Assistance (Ação Social Escolar, ASE) aims to prevent social exclusion and early school leaving. It promotes school and educational success, allowing all students to successfully complete compulsory schooling, regardless of their social, economic, cultural and family situation. As mentioned earlier in this report (see Chapter 1), eligibility for financial aid is structured in income brackets. Students in bracket A, corresponding to students with families receiving the lowest income, receive the most support, including free meals and textbooks. Students in bracket B also receive significant support, although less than students in bracket A (e.g. they have to pay 50% of the price of school meals). Students in bracket C are from families with the highest income and do not receive any support (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]). Between the 2014/2015 and 2017/2018 school years, the share of students benefiting from the ASE decreased from 40.1% to 36.1%. During the 2017/2018 school year, among the 36.1%% benefiting from the ASE, 20.7% were in bracket A, while 15.4% were in bracket B (Figure 2.4).

The Priority Intervention Educational Territories Programme (TEIP)

The first generation of the Priority Intervention Educational Territories Programme (Terrirórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária, TEIP) was implemented in the 1996/1997 school year. The fourth generation, which is currently starting, includes 146 school clusters (about 18% of the total of Portuguese school clusters). The TEIP programme involves schools located in areas with high levels of poverty and social exclusion, as identified by educational (e.g., school failure) and socio-economic indicators (e.g., the ASE). Within the transition from third generation to fourth generation (TEIP 3 to TEIP 4) there was the revision of the criteria for integration in the TEIP Programme and thus, recently ten school clusters have been added to this programme (there used to be 136) following the Council of Ministers’ Resolution 90/2021 in the scope of a national learning recovery programme that extended the TEIP programme to schools with a high number of students with an immigrant background and with a wide variety of mother tongues.

Through the TEIP 3, schools have been encouraged to develop a plan of improvement (plano plurianual de melhoria, PPM) based on their own knowledge of their context and challenges. The plans aim to strengthen their autonomy and positive discrimination measures to support the inclusion of all students. The last PPMs cover the years 2018 – 2021.

With the support of the MoE, TEIP schools implement their three-year Improvement PPM focused on four main, broad areas of intervention: (1) improvement of teaching and learning to ensure educational success; (2) prevention of early school leaving, absenteeism and indiscipline; (3) school management and organisation; and (4) relationship between school, family and community (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]). Regarding the monitoring process of the TEIP programme, there are regional teams from the MoE that support and provide a close contact for these schools to help them make the necessary adjustments to their commitments, methodologies and practices.

Specific Tutorial Support (ATE)

Implemented since the academic year 2016/2017, Special Tutorial Support (Apoio Tutorial Específico, ATE) consists of close and continued support to students in the second and third cycles of basic education who are over 12-years-old and have had two or more grade repetitions. It aims to prevent early school leaving, increase retention and, overall, promotes educational success by complementing other existing measures.

Choices Programme (PE)

First implemented in 2001, the Schools Programme (Programa Escolhas, PE) is a government programme promoted by the Council of Ministers under the leadership of the Portuguese High Commissioner for Migrations (Alto Comissariado para as Migrações, ACM). The PE targets 6- to 30-year-olds in vulnerable social and economic situations. These include children and young people with an immigrant background and from Roma communities. The PE, currently in its seventh generation, funds 101 projects, including three in the Autonomous Regions of Madeira and Azores. Its budget comes from the overall State budget and is co-funded by the European Social Fund and regional programmes in Lisbon and the Algarve.

The main objectives are to promote the social inclusion of children and young people from the most vulnerable socio-economic contexts. Various areas are included in the programme, including education and training considered essential to foster equal opportunities and inclusion. Projects funded by the PE are planned to be intensified in 68 municipalities, mobilising numerous partnerships between municipalities, parishes, school clusters, migrant associations and other relevant stakeholders13.

Commissions for the Protection of Children and Youngsters (CPCJ)

Created in 2001, the Commissions for the Protection of Children and Youngsters (Comissões de Proteção de Crianças e Jovens, CPCJ) succeeded the Commissions for the Protection of Minors created in 1991. The CPCJ offices are spread throughout the country and aim to prevent or end current or imminent situations which endanger the lives of children and young people. In addition to other areas of intervention, they specifically consider children and young people’s participation in school and their educational success. Each Commission includes a representative from the MoE, preferably a teacher. There are 269 teachers in total working at the CPCJ.

The National Programme for School Success Promotion (PNPSE)

The National Programme for School Success Promotion (Programa Nacional de Promoção do Sucesso Escolar, PNPSE) was created in April 2016. Its mission is to prevent school failure by reducing grade repetition rates through a bottom-up approach. Each school can implement its own strategic action plan to promote educational practices and improve learning14. The PNPSE has been engaging closely with local authorities and inter-municipal entities, with which it implements various programmes to combat school failure, such as the Integrated and Innovative Plan to Combat School Failure (Plano Integrado e Inovador de Combate ao Insucesso Escolar, PIICIE).

In practice, the PNPSE is based on a logic of proximity, meaning that it is implemented through teams constituted of officials close to the field. The PNPSE can:

Support local initiatives of diagnosis and interventions, i.e., ensure the training of local officials and school staff to design and implement strategies tailored to their context.

Promote practices that anticipate and prevent failure through an emphasis on early intervention instead of remedial strategies.

Encourage common and collaborative strategies between local education authorities.

In August 2020, all the public schools of mainland Portugal (including the TEIP schools) were invited to apply for the Personal, Social and Community Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento Pessoal, Social e Comunitário, PDPSC), which is part of the PNPSE and sets out measures to support students’ return to school after the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These plans aim to welcome students, reinforce their learning, promote well-being, foster social skills and enhance interaction with the community. From a total of 810 schools and school clusters, 668 have designed plans that comprise a total of 1 316 measures for social and educational intervention, corresponding to an average of two measures per plan. During the school year 2020/2021, schools and school clusters that applied were able to hire more than 900 specialised support staff (e.g. psychologists, social workers, IT technicians, artists) to implement these plans (Verdasca, J.; et al., 2020[19]).

The National Plan for Arts (PNA)

The National Plan for Arts (Plano Nacional das Artes, PNA)15 is a culture and education initiative for 2019-2029 that operates through partnerships with school clusters that develop their own artistic and cultural projects promoting curricular development and inclusive education.

The PNA is currently working with 148 school clusters, spread across the country and the Autonomous Regions (Azores and Madeira) and two Portuguese schools abroad: Mozambique and Timor-Leste. In these schools, Coordinators of the Cultural School Project (CSP) are identified, and CSP Consultative Commissions are formed. The commissions are formed of school staff, staff from the departments of culture of the city councils, cultural institutions (directions of theatres, museums, educational heritage services, etc.), artistic associations, higher education institutions and representatives from previously described plans and programmes already existing in schools.

The PNA supports various artistic and cultural projects, including:

Resident Artist Projects: An artist, cultural association or theatre company can reside in a school for a minimum of three months. During the 2019/2020 school year, there were 19 Artists in Residence. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of this work was conducted through online communication.

Digital Educational Resources Website: Created in March 2019, the online page provides digital resources for all students, teachers, mediators and parents about the arts, heritage, culture, citizenship, sciences and the humanities. More than 300 digital resources are provided to be incorporated in other curricular subjects at each year of education.

Academia PNA: The PNA also provides training courses and accreditations for teachers. The vast majority are now online courses, carried out in partnership with the School Association Training Centres.

The Digital Programme for Schools

The Digital Programme for Schools (Programa de Digitalização para as Escolas16) is a part of the national Plan for Digital Transition. The Action Plan for the Digital Transition was formally created in 2020 (Council of Ministers Resolution No. 30/2020) to develop a programme for the digital transformation of schools. The Programme has a strong commitment to teacher training to ensure the acquisition of the competences necessary for teaching in digital environments. The training of teachers is articulated with the Action Plan for the Digital Development of Schools, a fundamental document to support decision-making and monitoring of digital strategies. This measure aims to actively contribute to schools’ technological modernisation, familiarising students with digital tools they might increasingly encounter in the labour market. The objective is to develop teacher’s digital literacy skills so that they can use digital tools to strengthen pedagogical practices and simultaneously promote innovation in the teaching and learning process. Also, the programme aims to foster digital inclusion and give access to the internet to all. Within the frame of the programme, spurred by distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, computers with an internet connection have already been distributed to many students, giving priority to the most socio-economically disadvantaged students. Computers with an internet connection have also been distributed to all teachers. Digital access and literacy are important for inclusion not only to ensure certain student groups are not further excluded, but that digital education tools can also increase flexibility and personalisation for diverse student needs.

Resourcing for inclusive education

Overview on the funding of the education system

In comparison to other OECD countries, Portugal invests substantially in non-tertiary education. According to OECD (2021[20]), 3.8% of the added-value produced in the country (gross domestic product, GDP) in 2018 was dedicated to financing education, from primary to upper secondary education institutions. The share of GDP invested by Portugal in education was above the OECD average (3.4%) and, apart from France (3.7%), well above its Southern European peers (Figure 2.5).

According to the OECD (2021[20]), between 2012 and 2018, the total expenditure per student in primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary corrected for differences in purchasing power increased in Portugal, from USD 8 950 (EUR 7 876) to USD 9 300 (EUR 8 183) (+0.6%). Meanwhile, the total expenditure on education institutions at the same levels slightly decreased (-1.1%), which can be explained by a decrease in the student population (-1.8%). In sum, although between 2012 and 2018, Portugal’s student population has decreased and less is spent on education, the country spends more per student. Similarly, Portugal has observed a negative change in public expenditure on educational institutions as a share of the GDP within the same period (-7.4%). More than two-thirds of OECD and partner countries with available data experienced a reduction in the total expenditure on educational institutions as a share of GDP, although this is in most cases the result of a higher rise in GDP compared to education expenditure. Lithuania and Portugal were among the countries with the largest negative adjustments over that period, due to increases in GDP over 5% combined with reductions in total expenditure on educational institutions (OECD, 2021[20]).

While the share of GDP spent in education is relatively high at all educational levels, the absolute level of expenditure and expenditure per student is close to the OECD average. In fact, the annual expenditure per student in pre-primary and primary schooling, corrected for differences in purchasing power across countries, is below the OECD average at all levels of education except from lower secondary (Table 2.4). In 2018, Portugal spent slightly more than the OECD average in secondary schooling, a notable change in comparison to 2014 when the annual expenditure per student in secondary schooling, corrected for differences in purchasing power across countries, was about 15% below the OECD average (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]). Although expenditure has increased since 2014 at all levels of education, it still favours secondary and tertiary levels compared to pre-primary and primary ones (Table 2.4).

Furthermore, at the non-tertiary level, the funding of education in Portugal is mostly supported by public revenues, representing 89% of the total expenditure. The remaining 11% of the funding comes from household expenditure, while private sources do not participate in the funding of non-tertiary education (OECD, 2021[20]).

According to the National Council of Education (Conselho Nacional da Educação, CNE) (2020[18]), in 2019 Portugal spent a total of around EUR 9 million in education. About 71.2% (around EUR 6.4 billion) of this amount was devoted to non-tertiary education from pre-primary education to upper secondary. While the amount spent on non-tertiary education significantly decreased between 2010 and 2015, it steadily increased until 2019, the year that registered the third highest amount spent on education since 2010. Still in 2019, around EUR 5.7 billion were spent in pre-primary education, the highest amount since 2013 (EUR 5.8 billion). It was highlighted in the 2019 State Budget that the “budget has gradually increased over the past years. This is the result of an increase in the budget dotation for public pre-school classrooms, including animation activities and support to the families that extend the daily functioning hours of pre-schools, promoting a balance between work and family”.

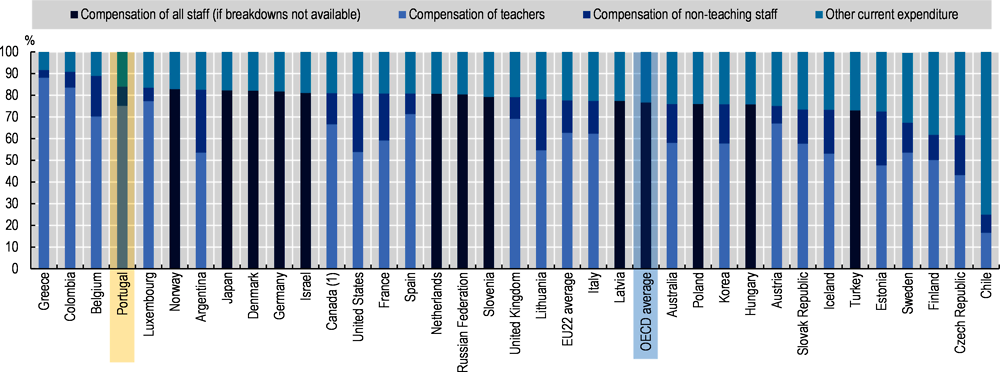

Also, overall, 98.4% of the budget for non-tertiary education was spent on current expenditures and less than 2% on capital expenditures17 (CNE, 2020[18]). Regarding current expenditures, as in most OECD countries, the largest share is spent on compensation of staff. In 2018, about 75% was dedicated to the compensation of teachers, 9% to the compensation of non-teaching staff and the remaining 16% to other current expenditures (see Figure 2.6). The latter category includes teaching materials and supplies, ordinary maintenance of school buildings, provision of meals and dormitories to students, and rental of school facilities.

Budgeting and planning process

The governance of the funding system in Portugal is historically largely centralised. Article 74 of the 1976 Constitution besides establishing that everyone has a right to education, indicates that the State must be responsible in ensuring universal and free basic education for all. This logic is extended to secondary education. The budget process for financing schools is annually defined, based on information provided by schools and central estimates, and is anchored in past expenditure corrected for inflation. The public budget for education is proposed by the MoE, negotiated with the Ministry of Finance and finally approved by both the central government and parliament (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]). Two separate mechanisms exist for budgeting centrally distributed funds, one for the teaching salary component of the budget and the other for non-teaching salaries and non-salary expenditures.

Furthermore, the financing of schools and the provision of resources are structured around two main axes (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]):

Teaching salary budget

Each spring, the DGEstE, in articulation with ANQEP for planning VET courses, provides student enrolment projections to each school cluster administration. The school cluster administration uses this information to decide on an offering of classes sufficient to meet student needs, following the guidelines presented in a set of governmental dispatches for the organisation of the school year. These include Normative Dispatches No. 10-A/2018, 19th June, and No. 16/2019, 4th June, which provide orientations on the class size and the organisation of the school year (organização do ano letivo), an official regulation published on a yearly basis by the Secretary of State for Education that defines key elements such as staffing rules for schools. The school cluster proposal takes into account planned strategic projects, including PNPSE and TEIP, and the estimated number of classes previously approved by DGEstE on the basis of the estimated distribution of students. DGEstE reviews, corrects as necessary and ultimately validates the network of class offerings for each school and the entire system (Ministry of Education, 2022[3]).

Once classes have been determined, the school cluster administration reviews the available permanent teaching staff returning to the cluster, compares the instructional needs with the available human resources and submits a proposal for any missing teaching hours to the DGAE to meet its instructional needs. Similarly, DGAE reviews the proposal, corrects it as necessary, validates the number of required teachers and then assigns the required teachers following established protocols. Finally, the financial department within the MoE, the Institute for the Management of Educational Finance (Instituto de Gestão Financieira da Educação, IGeFE), receives the defined staffing levels for each school cluster and transfers earmarked funds to schools and school clusters to pay teachers’ salaries (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]).

The source and allocation of funding for teaching staff and specialised technicians mainly come from the state budget and funds from the Human Capital Operational Programme (Programa Operacional Capital Humano, POCH). This system is managed by specialised entities of the MoE (mainly DGAE and DGEstE), according to centrally established criteria and guidelines to monitor local needs (see 0.).

Non-teaching salary budget

A parallel process exists for planning and developing the budget for the non-teaching component of schools’ budgets. Each spring, school administrators prepare a proposal for their non-teaching expenses to submit to IGeFE. This proposal takes into account prior-year expenditures, planned investment in school facilities and resources, and other projects pursued by the school, all following the guidelines relating to non-teaching expenses in the organisation of the school year regulations (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]).

IGeFE is responsible for analysing the budget proposal according to legal criteria and for defining the school budget. The amount requested by the school is contrasted with the results of a model recently developed by IGeFE based on historical expenses, number of students, levels of education, facilities at the schools, the existence of central heating and the geographic location of schools. This model, which was newly introduced for the 2017/2018 school year and is not public, automates the rules defined for each expenditure item. During the school year, IGeFE may approve additional ad hoc funding following a justified request from a school (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]).

Budgetary responsibilities and resource allocation

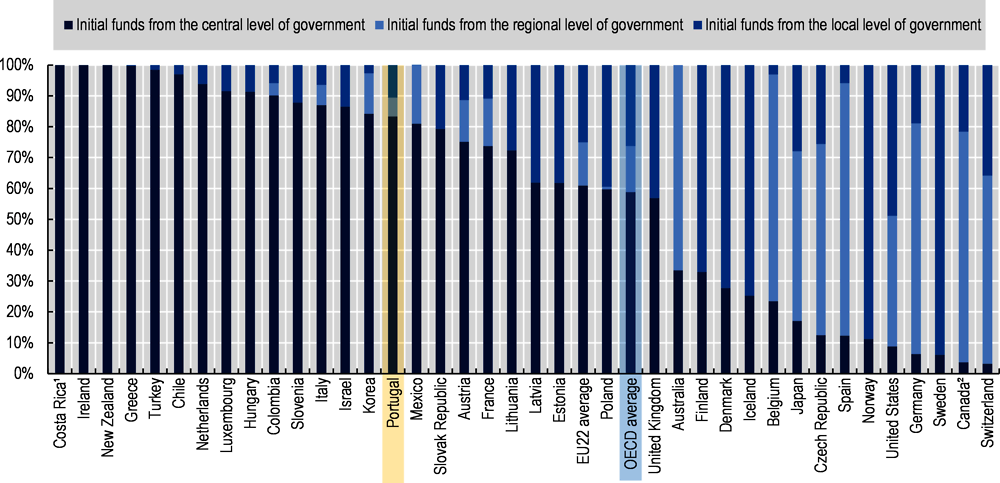

The funding system for education in Portugal is based on a system of transfer from central authorities towards the other levels of administration, which benefit from increasing autonomy to manage their resources (Lima and Franca, 2020[16]). Most of the budget is calculated and managed at the central level (see

Figure 2.7). It is then distributed through several funding streams, either directly to school cluster administrations or to municipalities that then distribute resources to schools according to needs assessments and established partnerships mechanisms. While this is true for current expenditures, most capital expenditures are managed by the municipalities or the Parque Escolar. Parque Escolar is a state-owned company, functionally dependent on the MoE, created in 2007. The main goal for the creation of Parque Escolar was to plan and carry out a Programme for the Modernisation of Secondary Schools, with the objective of updating and restoring the physical, environmental and functional effectiveness of secondary school facilities. Parque Escolar also inaugurated a new management model for the maintenance of the intervened school infrastructures (Liebowitz et al., 2018[14]). Actors at the different levels of the education system and other relevant stakeholders take part in the allocation of the educational funds and resources.

While the education system remains largely centralised, policy initiatives, programmes and support measures have recently created room for local agents, namely schools and municipalities, to intervene with relative autonomy. They are increasingly able to implement initiatives in partnership with schools and other stakeholders so that they can adapt to local contexts and further promote inclusion and school success.

Schools and school clusters have limited autonomy to manage their budget. The vast majority of schools’ operating budgets are devoted to staffing and transferred to competent units within the MoE (mainly DGAE and DGEstE) through IGeFE. However, the levels of staffing, the selection of staff and the assignment of teaching staff to schools are decisions made at the central level (see Chapter 3) as established in Decree Law No. 41/2012 (first established by Decree Law No. 139-A/90) Career Statute of Childhood Educator and Basic and Secondary Education Teachers (Estatuto da Carreira dos Educadores da Infância e Professores do Ensino Básico e Secundário). The Statute18 is the reference document for the management of teacher’s careers from their education and training to their retirements. It describes the rights and duties of educational staff and sets rules related to recruitment, salary, career evolution opportunities, etc.

School clusters control the assignment of teachers to roles. In particular, at the school level, the directors of the school clusters are responsible for: (1) managing the allocated funds (except for the salaries of teachers and other professionals and investment expenditure, which are directly managed by the MoE); (2) monitoring spending; and (3) reporting the number of students engaged in school activities and their academic achievement. Schools report their annual activities plan and budget to the MoE each year. This report includes the initiatives and activities promoted by the school, the associated expenditures and students' academic results. Schools also report periodically on additional funding allocated to them through applications for specific support measures or programmes. These are sent to the administrative bodies mentioned above that have approved the initiatives and the associated funding.

Municipalities have formal responsibilities for the education funding of pre-primary and primary schools (first cycle/lower primary). In particular, they are responsible for providing non-teaching staff, maintaining buildings and assigning/maintaining standard equipment. Additional responsibilities are in the process of being transferred to the municipalities, covering non-instructional aspects of education.

Since 2019, with Decree Law No. 21/2019 (Framework for the transfer of competences to municipalities and to intercity entities in the field of education), the competences of municipalities in the field of investment, equipment, conservation and maintenance of school buildings are extended to all basic education and secondary education, with the exception of schools whose education and training offer covers, due to its specificity, a supra-municipal territorial area. In preparing the Educational Charter19, the municipalities and the government department with competence in the matter must closely collaborate and coordinate their interventions. At the municipal level, the Educational Charter is the instrument for planning. The educational charter is thus the reflection, at the municipal level, of the planning process at the national and inter-municipal level of the network of education and training offers.

Municipalities report their annual interventions in terms of activities promoted or supported, the number of students involved and the expenditure incurred. Results and cost effectiveness are not usually evaluated. Annual accounting reports from municipalities are submitted to the Municipal Assembly for approval before being disseminated on their websites.