Executive Summary

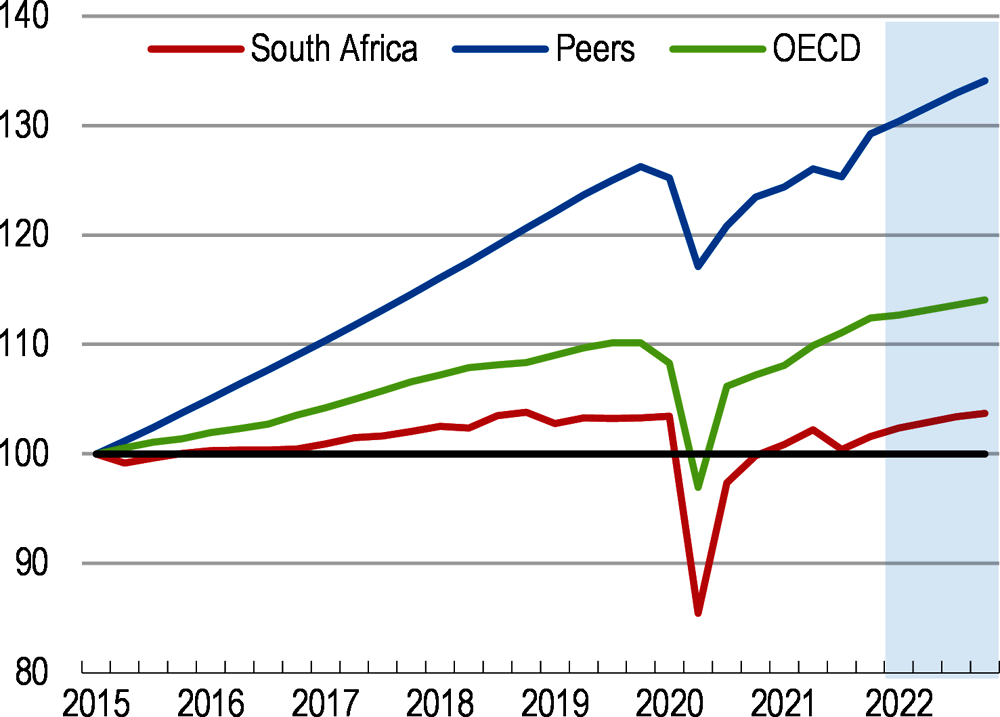

The economy was hard hit by the pandemic in 2020 (Figure 1), but the bold policy response limited its socio-economic impact and contributed to a strong recovery. Risks remain high, though.

The government has managed the crisis rather well. Since 2020, the wage subsidy scheme has protected employment and household incomes. The temporary increase in social grants and the introduction of a relief grant for unemployed have helped households withstand the crisis. Certain social measures have been prolonged until March 2023. In 2021, mobility restrictions have become more targeted and were gradually relaxed as the health situation improved, and new restrictions in response to the Omicron wave proved short-lived.

Consumption and exports are driving the recovery, with exports benefiting from robust global demand and favourable commodity prices, (Table 1). Assuming that the pandemic is progressively brought under control, growth will be increasingly driven by household consumption and investment.

Risks remain high. The vaccination campaign has slowed down and is lagging peer countries. New waves of the pandemic driven by new variants could affect economic activity. Domestic near-term risks to growth include increased electricity load-shedding and higher-than-expected prices. Also, investor’s confidence remains low and vulnerable to policy developments.

Prudent fiscal policy and reactive monetary response will be key in preserving the recovery. Increasing government revenues while better spending and fighting corruption within public entities are needed.

The tightening of monetary policy should continue if needed for inflation to converge toward the mid-point objective. Headline inflation reached 7.4% in June, well above the mid-point of the target band of 4.5% and above the 6% upper limit. Inflation is expected to remain above the target in 2022 and only start to converge towards the target by the end of 2023.

Public spending pressures remain high, but the government should maintain a progressive consolidation strategy to bring back debt on a sustainable path, notably by reinstating and strengthening the spending rule. Reducing the size of the government’s wage bill remains essential. The wage freeze plan agreement between civil servant unions and the government is welcome.

The VAT rate is relatively low and additional VAT revenues could finance spending needs, including the social grant, education or infrastructure. A VAT increase will need to be accompanied by measures to offset negative repercussions on the poor, for instance as done in the 2018 increase of the VAT rate.

There is scope to make the tax system more growth-friendly. The corporate income tax rate of 28% is relatively high. Tax liabilities are reduced by generous assessed losses. The design of interest deductions and capital depreciation rules can be improved.

Government exposure to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) represents a significant risk to debt sustainability. The electricity producer Eskom is the highest liability risk to public finances. Public transfers to failing SOEs remain high. The widespread underperformance of SOEs is due to mismanagement, corruption, overstaffing and an uncontrolled wage bill. The market discipline faced by SOEs is low.

Efforts to tackle corruption within public entities are too slow. Responses to revealed corruption cases are sluggish. Many investigations have not yet progressed to prosecution and convictions. Public procurement remains vulnerable to corruption and mismanagement.

South Africa has one of the highest measured levels of wealth and income inequality in the world. Boosting job creation and strengthening the redistributive role of the tax and benefit system are key priorities.

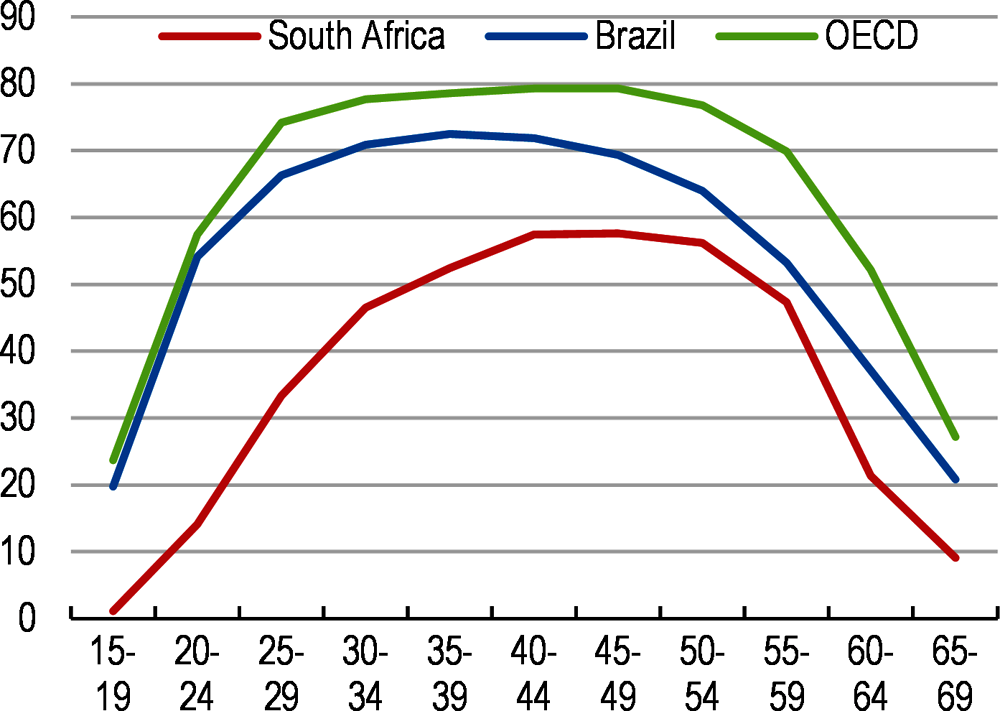

The pandemic has worsened labour market outcomes and further pushed up inequality. Unemployment is high, while the employment rate is lower than the OECD average and peer countries, particularly for the youth (Figure 2).

The labour market needs to become more flexible. Wage bargaining remains confrontational and labour-employer relations have been ranked among the weakest by the World Economic Forum. The wage bargaining system suffers from a relatively high level of bargaining at industry level, declining representativeness of bargaining councils and inadequate extension of their agreements to non-members. As a result, wage growth is weakly linked to productivity growth.

The means-tested cash-transfer system covering about a third of South Africans plays a critical role in reducing poverty, inequality and protecting vulnerable households. The social distress relief grant instituted during COVID-19 has extended a social grant for the first time to people of working age, mainly unemployed and informal workers. The possibility of making permanent this COVID-19 relief grant is raised.

South Africa’s high level of inequality undermines social stability and inclusive growth. The top 10% earners capture almost 50% of revenues and the wealthiest 10% hold 85.6% of net wealth. The tax system could do more to reduce inequality. The progressivity of the personal income tax is undermined by tax deductions benefiting mostly high-income earners. Tax allowances and deductions are substantial and regressive. Deductions for medical expenses and the tax relief for pensioners are regressive.

Wealth taxes rely mostly on estate duty, which could be broadened. Life insurance, trust and pension savings are exempted from estate duty and are used to escape taxation. Greater reliance on immovable property taxation is currently hampered by great variation in local governments’ capacity.

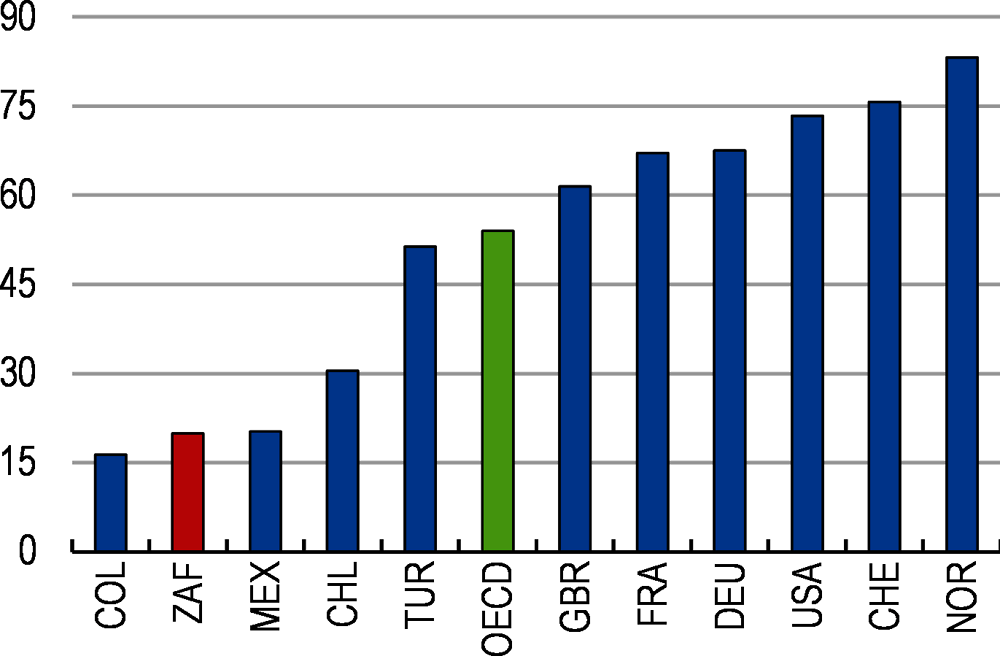

South Africa’s productivity is comparatively low and declining (Figure 3). Improved infrastructure, enhanced competition and better skills are required to lift productivity and potential growth. In addition, the tax system could be made more growth friendly.

Lower public investment and insufficient cost-benefit analysis is weighing on the quality of transport infrastructure. The road network is used intensively for trade, as 90% of goods are moved through roads. Maintenance is not conducted as regularly and early as needed, which has a large impact on road quality, given heavy usage and extreme weather events.

Lagging telecommunication infrastructure is holding back the benefits of digitalisation. Access to broadband connection is low and only 2.4% of inhabitants have subscribed to high-speed Internet. Broadband speed is also low by international comparison while subscription fees are high. Many high-income areas are over-served while the rest of the country remains unconnected. Access to mobile communication remains expensive. New frequencies should be attributed rapidly.

Regulatory policies remain restrictive and competition low in many key sectors. South Africa compares unfavourably in most product market regulation indicators. The economy suffers from lack of openness, which affects the cost of doing business and impedes entry and growth of SMEs. Access to many professional services is heavily regulated and costly. Widening access to professional services and aligning competition policies of sectors regulators with the Competition Commission would open up opportunities and boost growth.

Increasing human capital is key to lift potential growth. The country suffers from shortages of high-skilled workers and skills mismatches more generally. Although educational performance has improved markedly, progress has slowed since 2015. The education system has adjusted in several aspects to reduce the effects of poverty on learning. Efforts to increase the quality of education should include increasing the quality of primary and secondary schools, further developing vocational training and adult learning.

The supply of university and post-secondary graduates remains limited. In 2019, only 5.4% of people aged between 18 and 29 were enrolled in higher education, compared to 20.5% in the OECD. Enrolment in higher education and graduation rates are low. The supply of graduates is severely constrained by the lack of university infrastructure and the high cost per student. Changing the financing formula of universities would reduce the cost per student and allow enrolling more students.

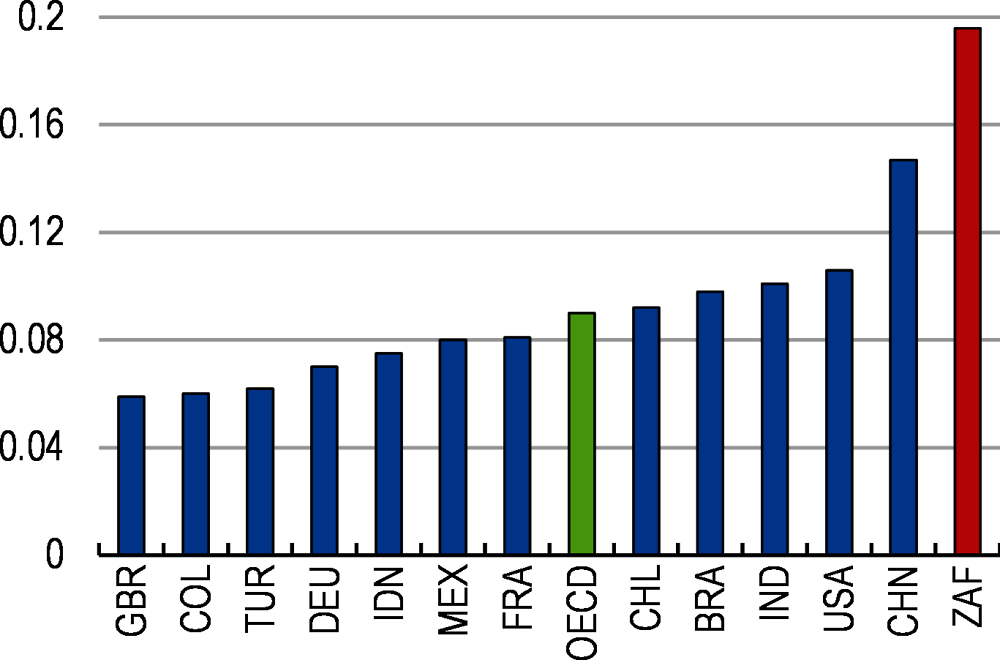

Tackling climate change is a pressing challenge. CO2 emissions per unit of GDP are high, reflecting in part the high-energy intensity of the economy (Figure 4).

Coal remains the main source of energy. The carbon tax introduced in 2019 is welcome but is relatively low: exemptions to the carbon tax should be reduced and its level gradually increased. The $8.5 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership between South Africa and France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the EU offers an opportunity to finance the transition to renewable energy.

Increasing the share of renewable energy in electricity will reduce electricity shortages quickly and CO2 emissions. The number of hours of load shedding has continuously increased since 2018. The cost of electricity is high and rising. Admitting private providers of renewable energy would quickly increase electricity availability. The amendments to allow renewable electricity generation projects from private providers up to 100 MW without licencing are welcome. However, steps should be taken to ensure that registration process and undue regulatory procedures will not delay the implementation.