2. Improving health outcomes

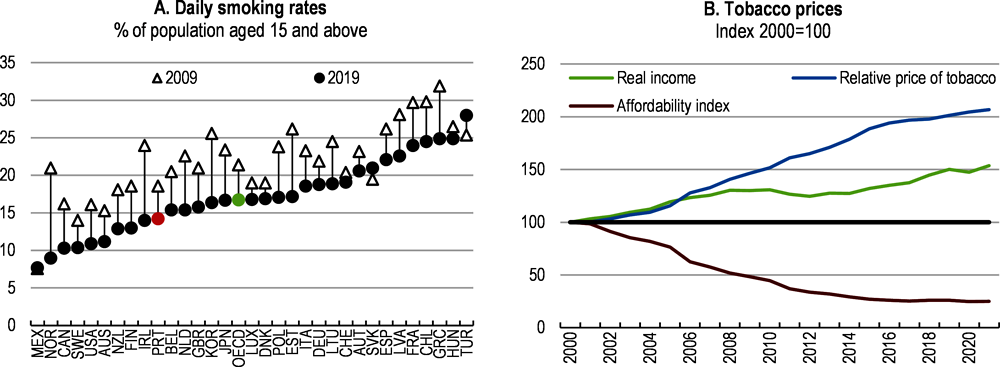

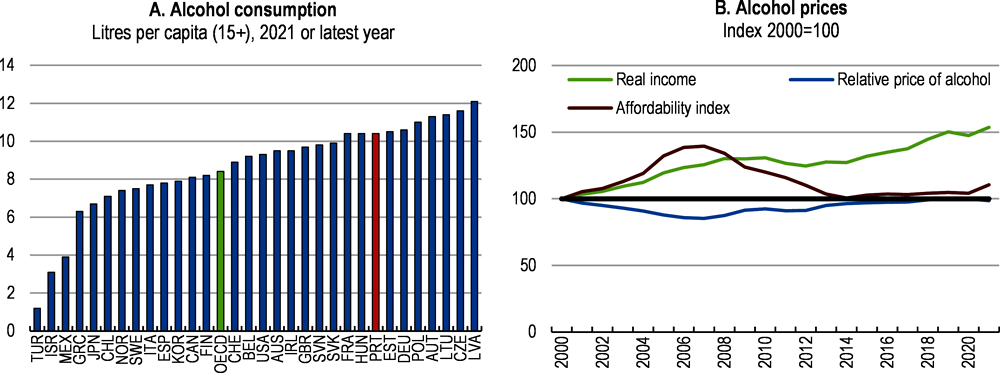

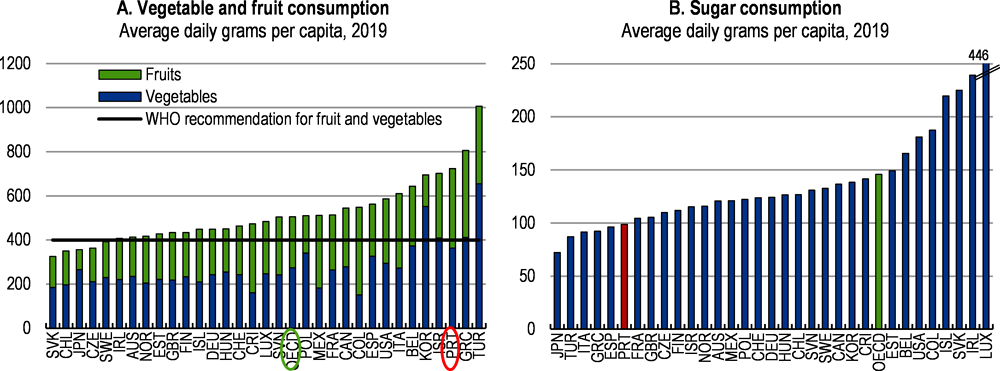

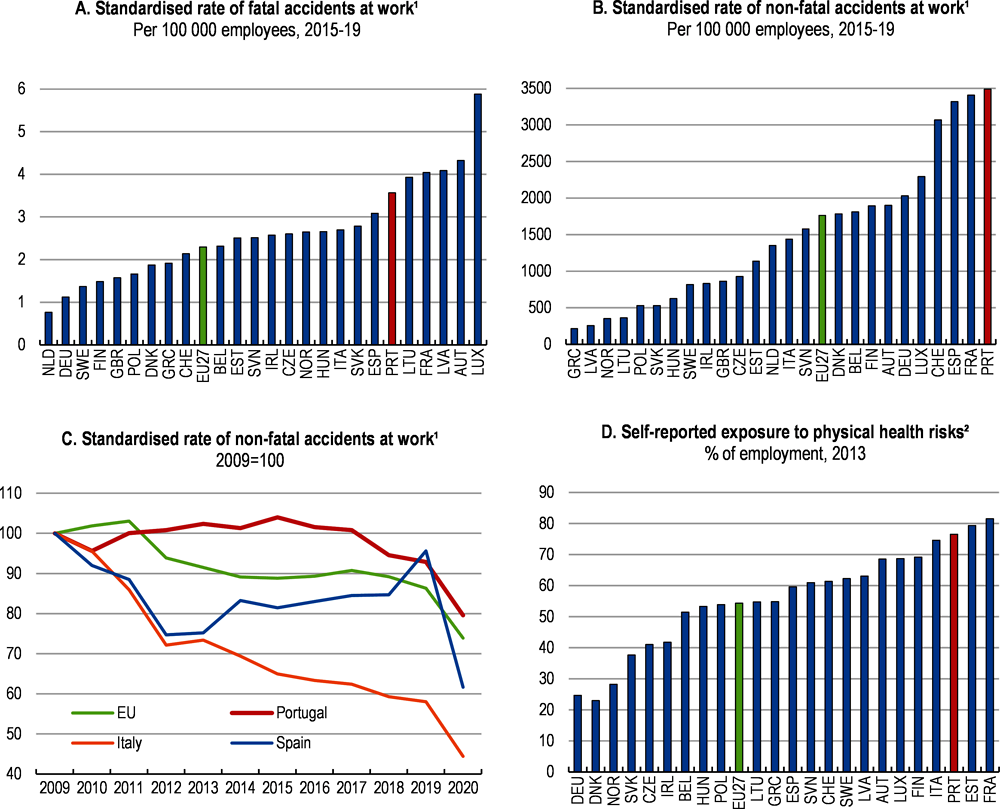

Health outcomes have improved substantially during recent decades and life expectancy is high compared with other OECD countries. Overall, the universal National Health Service offers good quality-care and has delivered high vaccination rates, while public spending remains contained. However, challenges related to staff shortages and heavy pressures on staff, long waiting lists in the public sector and high out-of-pocket expenditures have been building and were further compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. This partly reflects a system that remains strongly based on hospital care and has suffered from underinvestment in the years following the global financial crisis. In addition, obesity, a lack of physical activity and high alcohol consumption are weighing on long-term health outcomes, while the ageing of the population will increasingly require more and different healthcare services. The government has initiated a wide-ranging reform agenda through the Recovery and Resilience Plan and the 2022 reform of the National Health Service, with the aim of enhancing the integration of primary, community and hospital care. Reforms will need to address the generally weak budgeting and accountability practices, building on improved information systems and regular evaluations to ensure more efficient spending. Reforming primary care should remain a priority to scale up efficient prevention programmes, promote cost-efficient choices by care providers, improve access for low-income households and limit avoidable hospitalisations.

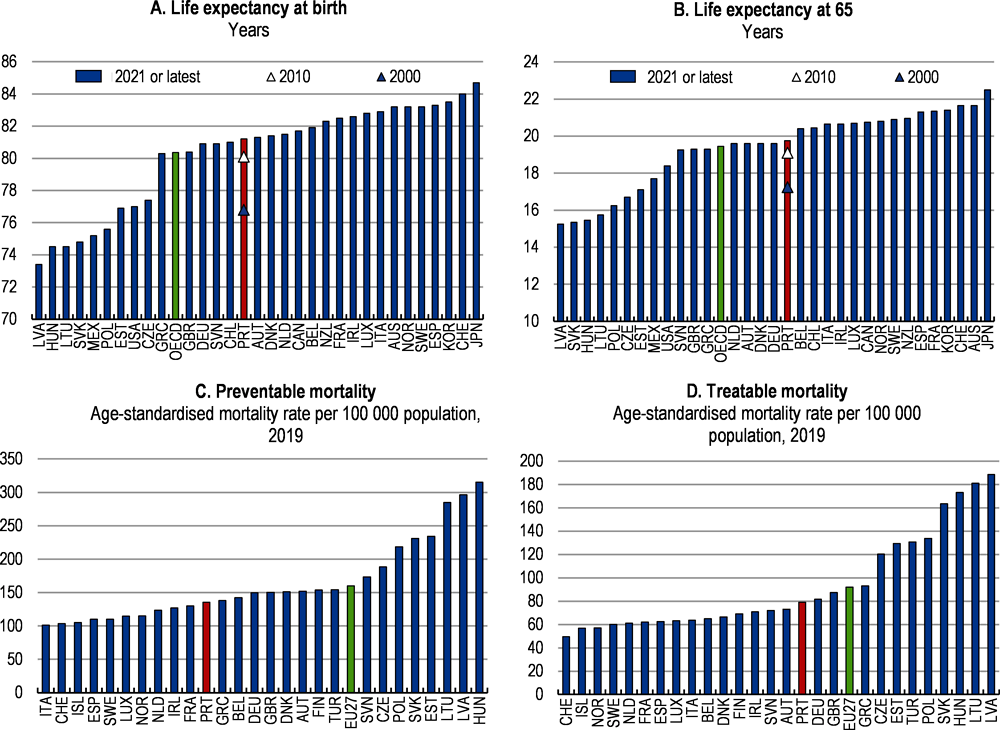

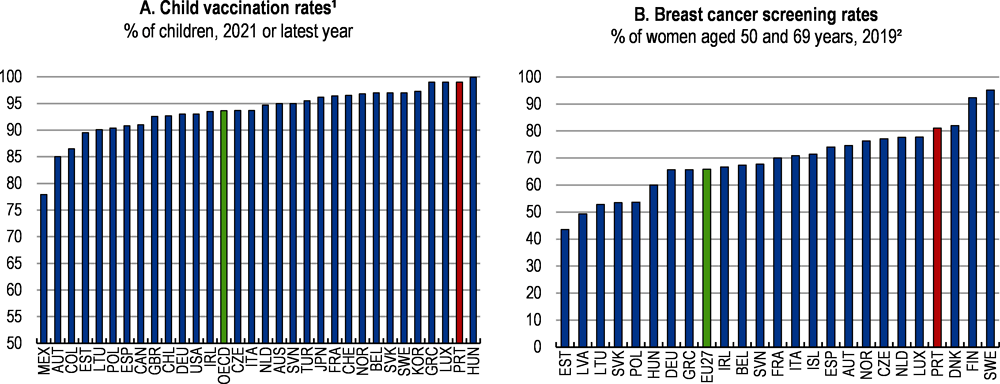

Health in Portugal has improved substantially over the past four decades. Life expectancy, the most frequently-used measure of health outcomes, has increased considerably, up by 10 years since 1980, and stands one year above the OECD average (Figure 2.1, Panels A and B). The national health system in Portugal provides universal access to good-quality care for all residents through the National Health Service and has many strengths: preventable and treatable mortality are low (Figure 2.1, Panels C and D) and routine and COVID-19 vaccination rates are among the highest in the OECD (OECD/EU, 2022[1]).

Overall, the quality of care delivered by Portugal’s health system is good, but there is scope for improvement in specific areas. While deaths related to preventable and treatable causes are below the OECD average, Portugal lags behind other European countries, such as Italy, Spain and France, suggesting that more could be done to save lives by reducing risk factors for leading causes of death, such as the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Avoidable hospital admission rates for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes are amongst the lowest in the OECD. Hospital admission rates for diabetes have steadily decreased over the last decade in Portugal and are now less than half of the OECD average. During the COVID-19 outbreaks, the health system proved fairly resilient, and was able to adjust the capacity of beds and medical staff through exceptional measures. However, many hospital procedures were postponed and staff working conditions deteriorated further, adding to already-existing backlogs, waiting lists and dissatisfaction among healthcare workers, which continue to remain elevated (Box 2.1).

As in most countries, the pandemic took a significant toll on health, lives and livelihoods. The government response included containment measures to limit the spread of the virus and substantial additional funding to the health system, which allowed a temporary expansion of human resources, and hospital and testing capacity (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]). Good public and private laboratory capacity and a successful vaccination campaign have also significantly contributed to lower the COVID-19 burden (ECDC, 2022[3]).

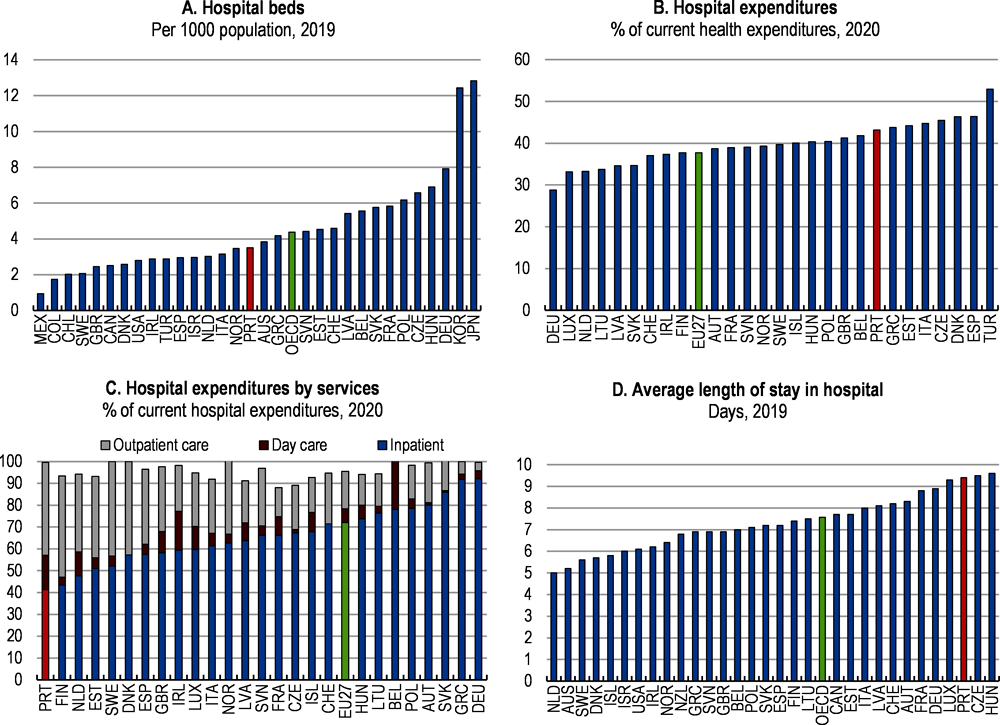

Yet, the peak of the outbreak put the Portuguese health system, notably hospitals, under severe strain. At the onset of the pandemic, both the number of beds per population and of intensive care unit (ICU) beds were relatively low (OECD/EU, 2022[1]). The government had to mobilise additional hospital capacity and equipment in March 2020, notably by shifting capacity from planned and elective procedures, and to take additional extraordinary measures a year later. As a result, Portugal nearly doubled its ICU capacity – from 587 beds in March 2020 to 1 015 beds by March 2021. Though the use of interregional patient transfers and requests (of mostly non-ICU) beds in the private sector also relieved some pressures, hospitals in some regions were regularly overwhelmed.

The pandemic led to significant health service disruptions. In 2020, Portugal was among the most affected European countries for elective surgeries, cancer related surgeries and chronic care (OECD/EU, 2022[1]).

Source: OECD/EOHSP (2021[2]), Portugal: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels; OECD/EU (2022[1]), Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris; ECDC (2022[3]), Data on testing for COVID-19 by week and country, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

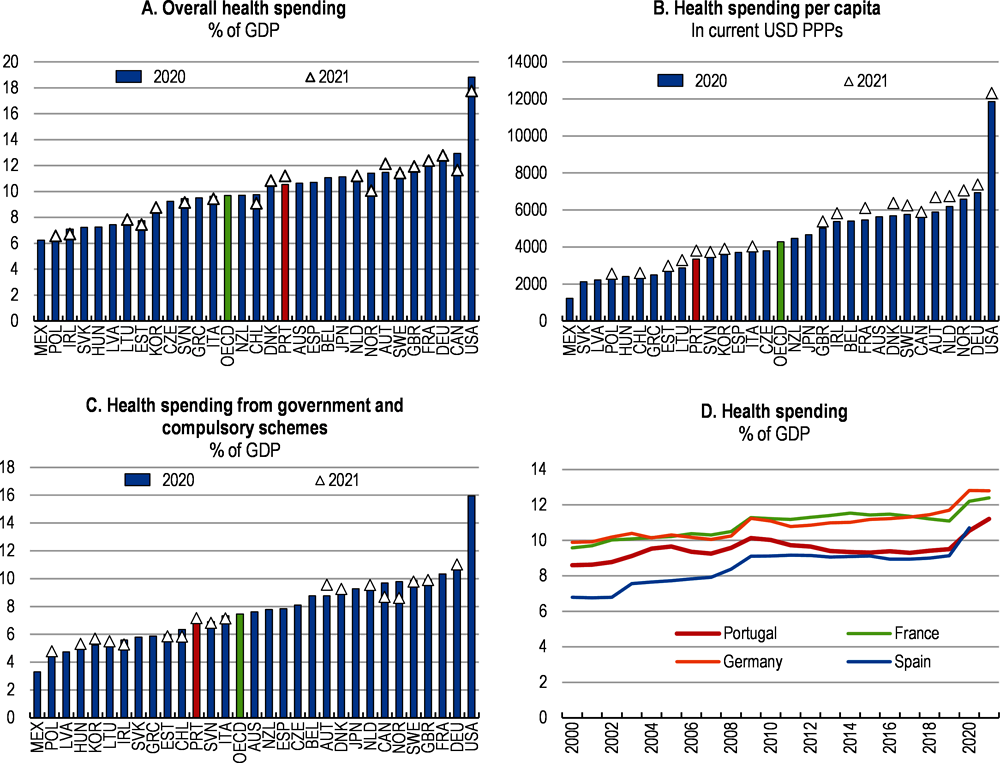

Public and private current expenditures on healthcare have been increasing in 2020-22, but this increase started from a comparatively low base. Health expenditures only returned to their 2009 share of GDP in 2021 following a persistent decline since the 2011 economic crisis (Figure 2.2). Spending on health, including public and private expenditures, was around 9.5% of GDP in 2019 and 11.2% in 2021, which is higher than the OECD average. However, on a per-capita basis, yearly spending was around USD 3,350, lower than the OECD average (Panel B) and public expenditures through the Portuguese National Health Service (NHS) accounted for only 6.8% of GDP in 2021 (Panel C). At the same time, there is sizeable potential for achieving cost-efficiency gains.

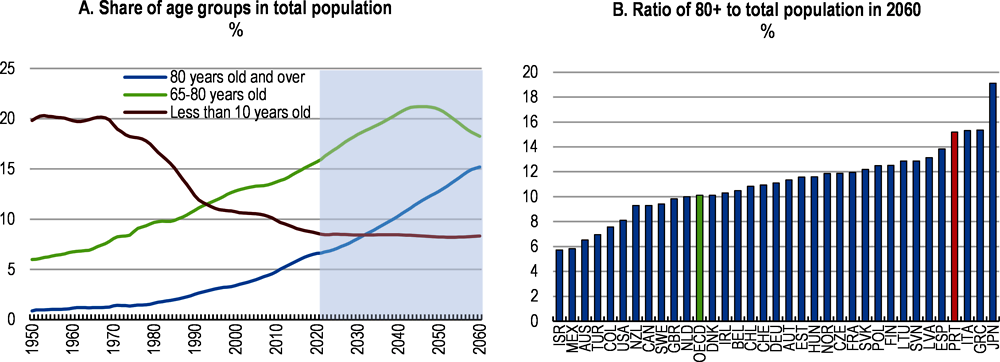

Rapid population ageing is one of the major upcoming challenges for Portugal’s health system. Despite a good performance on life-expectancy at birth, healthy life years at 65, which count the number of years spent free of activity limitations, are below the European average (OECD/EU, 2022[1]). Over the coming years, the health system will face rising care burdens and financial pressure as population ageing continues. The share of people over 80 years old, who are the largest per capita recipients of health and long-term care, will increase strongly (Figure 2.3). Population ageing will add to the already-increasing burden of chronic and degenerative diseases as well as multi-morbidity, which will gradually become more prominent.

Projections suggest that these developments will require significant increases in the number of health workers and in public health expenditures until 2060 (Box 2.2), while the current shortages of some health workers, notably nurses, and limited hospital capacity have already lead to high waiting times for surgeries and care and rising unmet medical needs. The COVID-19 pandemic has further aggravated these long-standing challenges.

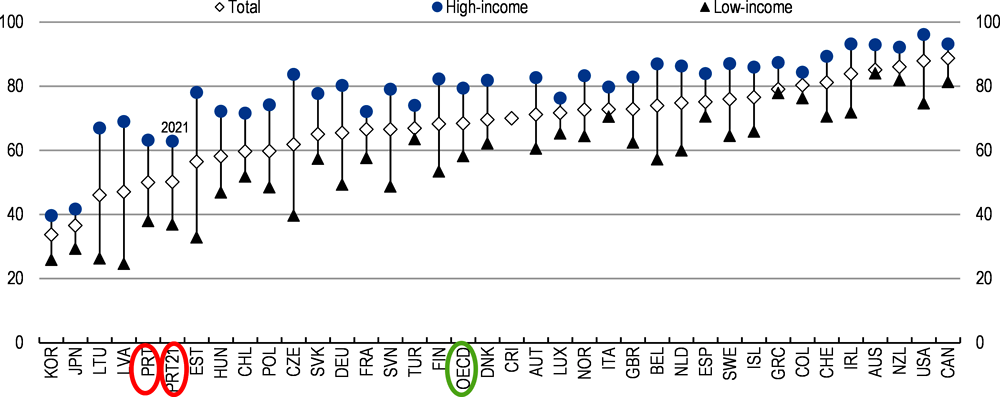

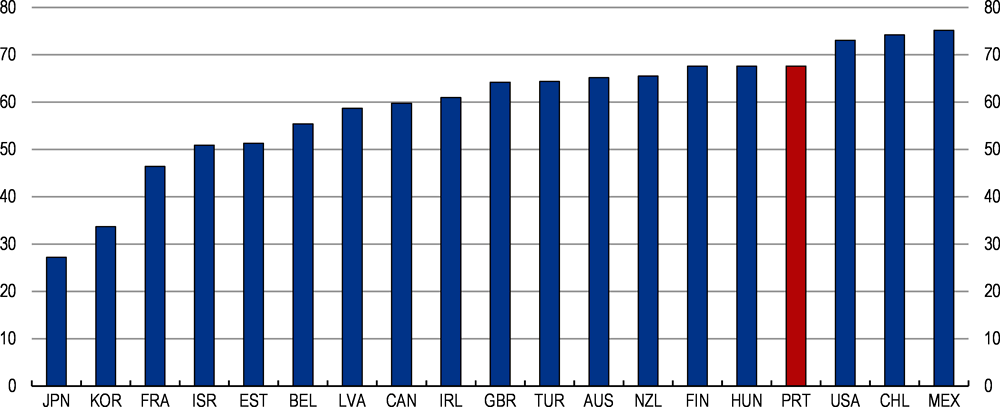

Social and geographical disparities in health outcomes are significant, despite good aggregate outcomes. Only 38% of those in the lowest income quintile reported being in good health in 2019, compared with 63% of those in the highest (Figure 2.4). Men are more likely to rate themselves in good health (56%) than women (47%) (OECD, 2022[4]). Compared to adults with the lowest level of formal education, those with a tertiary education have significantly lower occurrence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal disease and obesity (Perelman, 2022[5]). Health disparities in terms of obesity and mental health also appear correlated to education (Campos-Matos, Russo and Perelman, 2016[6]), while preventable death rates across municipalities are significantly correlated with local poverty rates (Costa and Santana, 2021[7]) and rural and low-density areas tend to display lower health outcomes (Girotti-Sperandio and Pereira-Montrezor, 2017[8]).

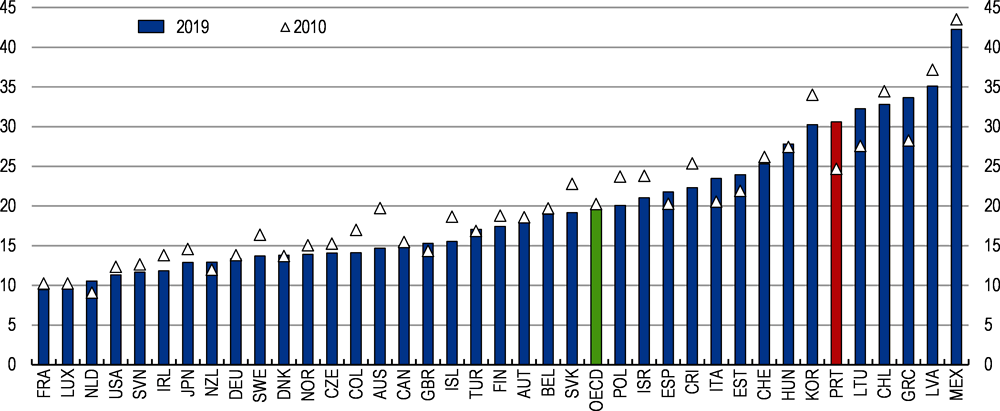

Health disparities across socio-economic and geographic groups are partly explained by different lifestyles and the design of the health system. The distribution of health resources, including facilities and health professionals, is unequal across regions and results in shortages of specialists in some areas (OECD/EOHSP, 2017[9]; OECD, 2023[10]). Differences in access to healthcare services across regions and neighbourhoods are related to high out-of-pocket expenditures for some households and care services, heterogeneous medical practices, notably among hospitals, and the low focus on prevention. For example, municipalities in low-density or border areas tend to have higher weaker geographical access to their reference hospitals (Costa, Tenedório and Santana, 2020[11]), while access to emergency services appears weaker in Lisbon’s poorer neighbourhoods (Silva and Padeiro, 2020[12]). Out-of-pocket payments for healthcare as a share of total health expenditure in Portugal (28.6%) are twice above the European average and amongst the highest in the OECD, which can limit access to healthcare and result in high private healthcare spending for some households, particularly low-income groups (OECD, 2021[13]; 2022[4]).

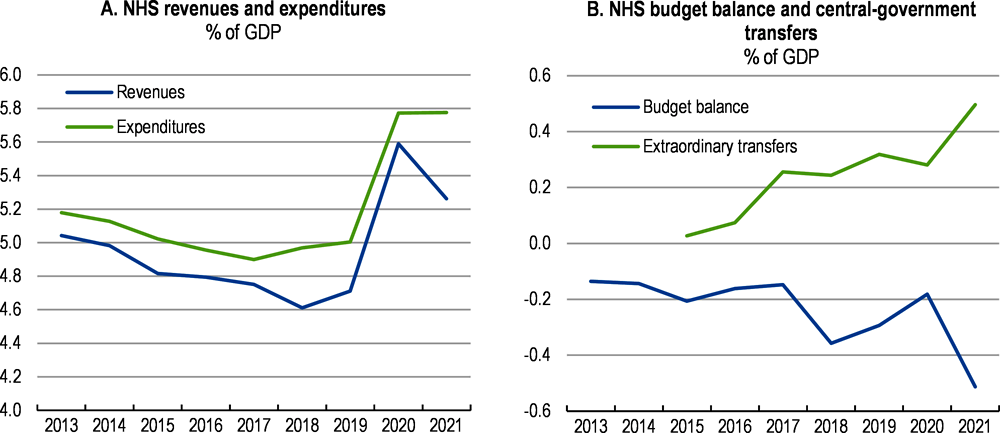

Portugal’s NHS has been a backbone of strong health outcomes, but its financial management has been a longstanding challenge. The increasing expenditure in the NHS since 2015 has been driven by a pick-up of public wages and rising costs of medicines and medical devices, putting increasing pressure on hospitals’ budgets (EC, 2021[14]). Combined with weaknesses in planning, costing and management control, hospital budgets have been repeatedly insufficient. As a result, public hospitals have accumulated sizeable arrears over each yearly budget, which have been repeatedly addressed by extraordinary transfers from the central government. In addition, growth in public capital spending on health has been particularly subdued since 2011, in line with a more general trend across government functions. Between 2011 and 2020, nominal capital spending increased by only 1.4% per year, compared to 9% on average between 2001 to 2010. Recent measures have started to address some of these issues, with the full payment of hospitals’ arrears at the end of 2022 and the increase in the health budget for 2023, while Portugal’s Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) foresees the implementation of a strengthened cost-accounting system.

Future health and long-term care needs are sizeable and challenging, but they are also highly uncertain, as illustrated by the large differences in projected outlays under different sets of assumptions (Table 2.1).

In addition to demographic and economic trends, health and long-term care spending needs will depend on:

The quality of additional years of life, i.e. the fraction of life expectancy gains that will be spent in good health. This will depend notably on medical progress, appropriate and equal access to good quality health care, and changes in preventive practices and lifestyles. OECD projections assume fully healthy ageing, while the European Commission assumes only “half healthy” ageing in its “reference” scenario.

The effect of technological progress on the cost of healthcare services, both in terms of lowering the price of existing services and creating new potentially costly services. The latter effect has been dominant over the past few decades, contributing to higher spending.

The income elasticity of healthcare demand, i.e. by how much rising incomes will increase healthcare spending. There is no consensus in the literature on the size of this effect. OECD projections assume an elasticity of 0.8, while the European Commission assumes 1.05 on average over the projection period, after controlling for other spending drivers.

The development of wages in the healthcare sector relative to other sectors. Wages in service sectors tend to grow as fast as in the rest of the economy despite slower productivity gains, leading to relative price increases for services, including healthcare (the so-called Baumol effect).

Societal changes, such as the evolving willingness of family members to provide informal long-term care for relatives.

The pace of reforms, such as changes to the follow-up of long-term diseases and payments to healthcare providers that would contain expenditure growth, as in the OECD cost-containment scenario.

The health sector has seen significant reforms, notably through the RRP (Box 2.4) and the 2022 Health law, which initiated structural changes to the National Health Service (Box 2.3). Ensuring the effective implementation of this demanding legislative and administrative reform agenda will be key to improve health outcomes and the efficiency of health expenditures. This will imply, among others, moving towards a better integrated primary, community and long-term care system. Against this background, this chapter reviews the current framework surrounding the healthcare system and health providers before focusing on some specific aspects. The main findings are:

The Portuguese system produces good aggregate health results, but with significant disparities and increasingly binding funding constraints. The current budgeting practices and past under-investment hinder the effective use of funding. At the same time, capacity shortages create disparities in access to care and coverage. More efficient budgeting practices and human resources management would help to address elevated waiting lists and staff shortages.

Ageing and rising chronic diseases make strengthening primary care and prevention an ever more urgent priority. Stepping up the ongoing efforts to increase prevention and co-ordination among care providers would promote healthier lifestyles and improve medium-term health outcomes. Beyond the healthcare system, re-organising long-term care will be crucial (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]).

Meeting the changing needs of the population and addressing the short-run shortages of health workers in the National Health Service will require a comprehensive review of payment systems, management practices and working conditions in primary care and public hospitals. Some regulations and payment arrangements could further encourage appropriate care and the development of efficient multi-disciplinary group practices.

The Portuguese National Health Service (NHS), established in 1979, is a tax-funded health system, governed by the public sector (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]; EOHSP, 2017[15]). The NHS provides universal health coverage through publicly-provided primary and specialised hospital care, and contracts with private and social sector entities on a supplementary and temporary basis. Its creation was in line with the principle of every citizen’s right to health, embodied in the new 1976 democratic constitution. The NHS coexists with two other health assistance mechanisms: the health subsystems and private voluntary health insurance (VHI) schemes, where citizens receive extra coverage either contracted through their employer or on an individual basis.

In Portugal, healthcare services are delivered by a combination of public and private providers (OECD, 2015[16]). The network of NHS primary care providers, such as primary care centres and primary healthcare clusters, are public entities under the Ministry of Health. , The hospital sector contains a mix of publicly and privately-owned facilities (OECD, 2015[16]). While remaining under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, the majority of NHS hospitals as well as hospital centres and local health units are run as public enterprises, a model in which the government retains ultimate ownership but gives some autonomy to managers of hospitals and local health units. Doctors and nurses employed by the NHS in both primary and hospital care are salaried government employees. The private sector commonly provides dental consultations, diagnostic services, haemodialysis and rehabilitation. Long-term care is mainly provided by social sector entities, under contracts with the NHS.

The responsibility for planning and allocating health resources is highly centralised (EOHSP, 2017[15]). The Ministry of Health is responsible for developing health policy and overseeing and evaluating its implementation, including most planning and regulation, and coordinating the provision of health care (EOHSP, 2017[15]). It also finances public healthcare services, and is responsible for the regulation, auditing and inspection of private healthcare providers.

The Ministry of Health includes several institutions under its direct and indirect administration. Some institutions under direct administration include the Directorate-General of Health (Direcção-Geral da Saúde, DGS), which plans, regulates, directs, coordinates and supervises all health promotion, disease prevention and healthcare activities, institutions and services. Others under indirect administration include the Central Administration of the Health System (Administração Central do Sistema de Saúde, ACSS), which manages financial and human resources, facilities and equipment and systems and information technology of the NHS, alongside the Executive Directorate of the NHS (Direção Executiva do Serviço Nacional de Saúde, DE-SNS). The National Authority on Drugs and Health Products (Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde, INFARMED) regulates the pharmaceuticals and health products sector. In 2022, the ACSS took on the role of managing agreements with healthcare providers and private and social sector entities, previously under the responsibility of five regional health administrations (Box 2.3). As reforms are implemented, they should be rigorously evaluated to ensure value for money, including through a formal spending review of all health spending.

The Shared Service of the Ministry of Health (Serviços Partilhados do Ministério da Saúde, SPMS) is a public enterprise responsible for providing the information systems, according to the priorities defined by the ACSS and the Executive Directorate. In addition, the National Health Council, a consultative, independent body for the Ministry of Health, is responsible for providing recommendations and advice on the implementation of health policies, and the Health Regulatory Agency independently regulates the healthcare sector, including the private sector.

Other ministries also play a role in the healthcare sector. The Ministry of Finance approves staffing and investment budgets for the NHS, while the Ministry of Labour, Solidarity and Social Security is responsible for social and disability benefits and the provision of some long-term care. The Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education is responsible for the education of undergraduate medical, nursing and allied health professionals, such as physiotherapy and radiology and for academic degrees (EOHSP, 2017[15]). However, specialised postgraduate medical training is the joint responsibility of the Portuguese Medical Association (Ordem dos Médicos) and the Ministry of Health.

Local governments have a limited role in providing healthcare. In 2018, several competencies were transferred to municipalities, including planning, management and investment in new primary healthcare units; management and maintenance of existing primary healthcare infrastructure; management of operational assistants in primary care centres; and participation in health programmes that promote community health, healthy lifestyles and healthy ageing (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]).

In late 2022, the government altered the status, management and task structure of the NHS by establishing an Executive Directorate to coordinate the healthcare response of NHS health units (Decree-Law No. 52/2022 of 4 August 2022 and Decree-Law No. 61/2022, of 23 September 2022; (EOHSP, 2022[17])). The Executive Directorate is a public institute under a special regime, with its own legal personality and endowed with administrative and financial autonomy. While under the supervision of government, it is not subject to the management power of the Ministry of Health.

The Executive Directorate is to issue regulations, guidelines, directives and generic and specific instructions to NHS establishments and services. It is also to take over the management of the National Network of Integrated Continuous Care (RNCCI) and National Network of Palliative Care (RNCP) from the ACSS. The Executive Directorate will also have the power to propose the appointment and removal of the management of health units.

The institute is headed by the Executive Director, who is the highest governing agent in terms of representation and management responsibility of the NHS and will have decision-making powers over the integration of care provision, network functioning and referral, access to healthcare and patient rights and governance and innovation. The Executive Directorate also includes a Management Council, to aid the Executive Director, a Strategic Council, comprised of the President of the Central Administration of the Health System (ACSS) and the President of the Shared Services of the Ministry of Health as well as a management assembly and supervisory bodies (Decree-Law No.61/2022, of 23 September 2022; (EOHSP, 2022[17])). It can also have regional units.

The creation of the Executive Directorate will result in flow-on changes to roles within the Ministry of Health. In particular, the ACSS and the local primary healthcare clusters (ACeS) are planned to take on the previous role of the Regional Health Administrations in managing agreements with healthcare providers and private and social sector entities (Box 2.5). The ACSS continues to plan and manage the financial resources of the Ministry of Health but will work with the Executive Directorate to prepare multi-year budgets and investment plans.

The 2022 reforms follow other recent reforms to tackle the challenges facing the healthcare sector. In early 2020, the government implemented the Plan to Improve NHS Responsiveness reform to address persistent budget imbalances, long waiting lists, increasing struggles for hospitals to hire healthcare workers and the need for greater investment in the NHS (EOHSP, 2020[18]). To address these issues, the Plan reinforced the 2019 and 2020 Health Budgets, approved a multi-annual investment programme, established a framework to recruit 8 400 new health workers between 2020 and 2021 and reinforced the autonomy to recruit healthcare workers in NHS hospitals. To promote better management the government allocated EUR 100 million to performance management schemes in NHS hospitals, providing incentives to both professionals and institutions.

The 2019 Health Basic Law aimed for a deeper separation of public and private sectors. It reinforced the requirement of public management of NHS units. While contracts with private and social sector entities can exist, these can be only on a supplementary and temporary basis (EOHSP, 2022[17]). The Law also established the waiving of user charges for primary healthcare and other care prescribed within the NHS. Previously, the use of most services, including emergency care, general practitioner (GP) visits and specialist consultations, incurred flat-rate user charges.

Source: EOHSP (2020[18]), Portugal - Health Systems in Transition, Country Update: The Portuguese Government approves a Plan to improve NHS responsiveness, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies); EOHSP (2022[17]) , Portugal - Health Systems in Transition, Country Update: The SNS Executive Directorate is created, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; Decree-Law No.61/2022, of 23 September 2022.

The Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) includes three reforms and nine investment projects in the NHS, valued at EUR 1.4 billion, to be completed by 2026 (EC, 2022[19]; Ministério do Planeamento, 2021[20]). The RRP addresses Country-Specific Recommendations (CSR) from the European Commission, including strengthening overall expenditure control, cost efficiency, and adequate budgeting, with a focus on a durable reduction of arrears in hospitals (CSR 1 2019) as well as strengthening the resilience of the health system and ensuring equal access to quality health and long-term care (CSR 1 2020; (EC, 2021[14])). Notable reforms and investments include:

Reinforcing the core role of primary healthcare services. Reforms and investments include deepening the capacity for screening, creating more proactive primary care centres with expanded areas of intervention, improving the geographical distribution of primary care providers, supporting community-based responses and enhancing the skills of the health workforce. Portugal will complete these reforms by end 2023 and the EUR 466 million of investments by mid-2026.

Completing the reform of the governance model of public hospitals to increase efficiency in hospitals by reforming their organisation and internal management, reconfiguring the hospital network, improving articulation with other elements of the NHS and involving health professionals in the management of public hospitals. Portugal is to complete the reforms by end 2025.

Addressing bottlenecks hampering the digital health transition and digital hospital, including a lack of hardware and software available for healthcare workers, strengthening the standardisation of information systems in the NHS and improving user experience and access to data. The EUR 300 million investments and EUR 15 million in Madeira will be completed by end 2024, while the EUR 30 million investments in Azores will be completed by 2025Q3.

Upscaling mental health services, addressing a model centered around hospitalisation and the lack of a nation-wide network of services (EUR 88 million) and investing in the National Network of Integrated Continuous Care (Rede Nacional de Cuidados Continuados Integrados – RNCCI) and National Network of Palliative Care (RNCP) (EUR 205 million).

Source: EC (2021[14]), Analysis of the recovery and resilience plan of Portugal, Commission Staff Working Document; EC (2022[19]), Portugal’s recovery and resilience plan, https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/economic-recovery/recovery-and-resilience-facility/portugals-recovery-and-resilience-plan_en; Ministério do Planeamento (2021[20]), PRR – Recuperar Portugal, Construindo o future.

The Ministry of Finance provides the Ministry of Health with an annual budget for total NHS expenditure based on historical spending and proposed plans (see below). From this NHS budget, public hospitals are allocated global budgets based on negotiated contracts signed with the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance. These contracts include plans for activity as well as staff numbers and investment. Public primary care providers are allocated budgets based on contracts on activity, performance, staff numbers and investment.

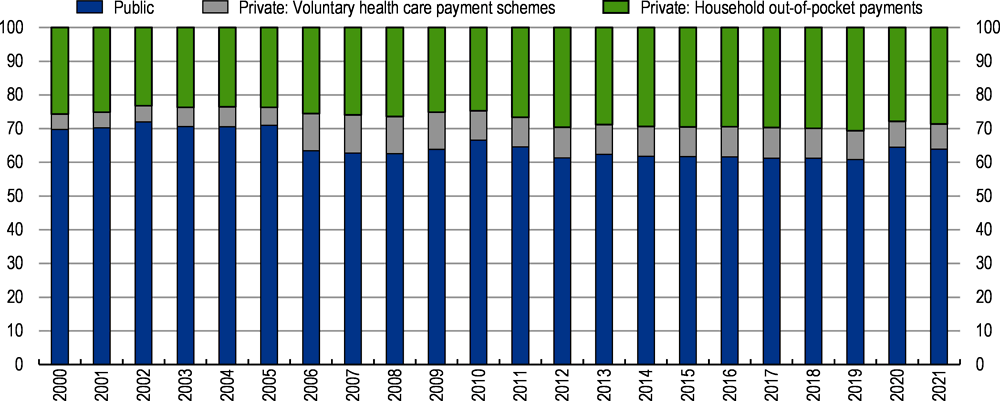

The NHS offerss a broad benefit package, covering the costs for services including general practitioner (GP) visits and outpatient specialist care in the public sector, as well as other services prescribed by NHS doctors, such as pharmaceutical products. User fees remain for the use of emergency rooms when not referred from within the NHS. While coverage is broad, Portugal has one of the highest shares of out-of-pocket (OOP) payments in the OECD, accounting for around 29% of total health expenditure in 2021, compared to around 18% on average across the OECD (Figure 2.5). OOP payments apply to some services typically provided by private providers, such as dental care, and to costs incurred by patients who opt out from NHS-provided services, notably those who benefit from some coverage of private providers’ costs through voluntary health insurance. While OOP payments were limited to 11% of inpatient curative and rehabilitative care expenditures in 2020, public coverage was particularly limited for outpatient medical care, medical goods and long-term care. Financial hardship associated with OOP payments for households, as measured by the incidence of catastrophic spending on health, is well above the OECD average. In 2015, close to 11% of households had to spend more than 40% of their remaining income on healthcare after deducting spending on basic needs (OECD, 2021[13]).

Voluntary health insurance and OOP payments play a significant role in financing health care (Figure 2.6). The two special health assistance mechanisms that coexist with the NHS, the health subsystems and private voluntary health insurance (VHI) schemes, provide comprehensive or partial coverage for particular professions or sectors, such as the schemes for civil servants and the banking sector, and are financed through employee contributions. Health subsystems only accounted for around 3% of current health expenditures in 2020 (INE, 2022[21]), though they generally provide better access to private providers than the NHS. The ADSE (Assistência à Doença dos Servidores do Estado) is the largest scheme, covering over 1.3 million public servants and their dependents. The VHI have a supplementary role to the NHS and the health subsystems. Buyers of voluntary private health insurance benefit from better access to several health services through private providers, notably private hospital treatment and ambulatory consultations. While more than 3.3 million individuals (around 32% of the population) were covered by voluntary individual or group private health insurance in 2021 (ASF, 2021[22]), spending only accounted for around 6% of current health expenditures in 2020 (INE, 2022[21]).

One of the principal challenges of the NHS relates to its budgeting processes, whose shortcomings have had serious implications for managing expenditures, ensuring the accountability of health providers and determining and achieving cost-efficient expenditures, both in the short and the longer run. The NHS budget has been repeatedly set below the cost of providing health services, leading to persistent deficits (Figure 2.7). This has made it impossible for the NHS to comply with the budgetary limits approved by Parliament (CFP, 2022[23]) and has led to the NHS’s frail economic and financial situation (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[24]). The Ministry of Finance provides the Ministry of Health an annual budget for the administration of the NHS during the preparation of the State Budget. In 2021, 96% of the NHS budget was allocated from the State Budget, complemented by a small share of earmarked revenues (CFP, 2022[23]). In 2019, more than two-thirds of NHS public enterprise hospitals were highly undercapitalised and over half had negative equity (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[25]). The unachievable budgets have meant that it has been difficult for management to identify and manage key spending priorities. Incentive mechanisms to meet budgeted expenditure have also been lacking, with the Ministry of Finance historically providing additional necessary funding in the form of extraordinary transfers. Aiming at addressing budget challenges, budgeted health spending has been increased by 7.8% for 2023 compared to spending executed in 2022, and 10.5% compared to the initial 2022 health budget (Governo da República Portuguesa, 2022[26]).

Beyond the inadequate size of the NHS budget, annual budgeting procedures also have scope for improvement to help better allocate spending in line with health goals and evaluate spending efficiency. Currently, authorities cannot determine the cost of single hospital procedures due to the lack of an accounting management system at the hospital level, even though this is a requirement in legislation. A new system will be put in place by the end of March 2024 as part of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), which will allow for the accurate calculation of healthcare costs. In the past, planning, strategy and budget documents and contracts between the Ministry of Health and healthcare providers have often been completed in the middle of the year to which they relate, or even later, limiting their usefulness yet using administrative resources for extended periods (Barros, 2022[27]). This delay has lead to significant payment arrears that end up spreading hospitals’ fragile financial situation to their providers.

Improving the budget process would allow management to more effectively allocate and monitor spending. Establishing some form of coordination mechanism between the Ministries of Finance and Health would be crucial for this, as Portugal is one of only three OECD countries with no formal or informal mechanism for this purpose (OECD, 2015[28]). Additionally, ensuring that the Ministry of Finance has the analytical capacity to assess the policies proposed by the Ministry of Health, which has previously been identified as a challenge, as in many OECD countries, will help to assess policy proposals (OECD, 2015[28]). The inclusion of some form of automatic budget adjustment mechanism for major cost drivers, as in Israel, could also help to simplify the annual budgeting process and improve coordination between the two ministries (Box 2.5). Expanding the budget from an annual to a multi-annual budget aligned with strategic and medium-term health priorities could aid in planning and meeting health objectives.

Given that budgets have provided little actual guidance on expected expenditures, they have failed to provide a reference point for the effective monitoring of spending over the year, and deviations from budgeted expenditures have risen in recent years (CFP, 2022[23]). The significant delays in the settlement of some contracts also hinder the ability to provide incentives for better management practices. The effectiveness of existing governance mechanisms, which aim to promote accountability and transparency, have been undermined by some flaws in implementation (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[24]). For example, management contracts outlining goals and targets have been of limited use when signed late or not at all. Acknowledging these challenges, in 2022 the government reformed procedures around the finalisation of management contracts to ensure the signing of contracts no later than three months following the appointment of the hospital board. Better monitoring the activity of NHS providers will also depend on collecting a wider range of performance indicators (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[24]). Accurate reference points would allow for more effective monitoring of health budgets through monthly expenditure reporting and mid-year budget reviews. An early warning system for overspending resulting in corrective mechanisms, such as those used in Belgium and France (Box 2.5), could help to reduce persistent deficits (OECD, forthcoming[29]).

The weaknesses of the health budget have hindered a transparent end-of-year reporting on its execution. Audits are fundamental to accountability and can yield useful findings on performance and value-for-money to inform future budget allocations (OECD, forthcoming[30]). The Court of Auditors, which has been auditing the NHS accounts since 2015, has reported material misstatements in the consolidated financial statements of the NHS that affect the true and fair view of the NHS’ financial position and performance (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[25]). Moreover, they noted that members of supervisory bodies are often appointed with a delay and statutory audits of accounts of NHS entities are often not performed within the legal deadline, which precludes the effective control of the financial and asset management of NHS entities. The delayed settlement of contracts with NHS health providers has often meant that external audit reports are issued with qualified opinions due to a limitation of scope (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[25]), limiting the quality and robustness of the audit process. The Portuguese Fiscal Council (Conselho das Finanças Públicas) has also provided a useful independent analysis on the economic and financial performance and sustainability of the NHS since 2013, and annually since 2020, highlighting the financial limitations of the NHS.

In Israel, the annual budget for health expenditure is based on an automatic adjustment mechanism according to demographic and technological developments and a price index. A specialised committee is responsible of the inclusion of new technologies into the health basket, linking the results of health technology assessment to the budget impact. The price index reflects changes in the price of inputs in the health sector, notably wages. The use of a set formula to determine the health budget has simplified the scope of negotiations between health and finance ministries. In addition, it guarantees a minimum annual increase in the health budget and provides some visibility over future funding levels.

In Belgium, a process known as permanent audit, monitors and controls health expenditure by monitoring all health insurance reimbursements. Reports are published monthly, quarterly, and half-yearly detailing the evolution of expenditure and volumes of healthcare usage. In response to the monitoring reports, the Minister of Social Affairs as well as the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance can propose corrective measures at any time to prevent an overrun of the budgetary objectives.

In France, several monitoring and corrective mechanisms ensure compliance with an annual target for health expenditure, known as the ‘Objectif national de dépenses d’assurance maladie’, or ONDAM. An ‘Alert Committee’ signals to key stakeholders if health expenditure risks exceeding the ONDAM by more than 0.5%. In addition, to limit the risks of exceeding the ONDAM, tools to correct the price of healthcare have been gradually put in place. Since the introduction of these measures, France has been better able to control health expenditure growth and prevent annual health expenditure exceeding its target.

Source: OECD (forthcoming[30]), “Effective management of health expenditure”; and OECD (forthcoming[29]), “Applying good budgeting practices to health”.

The weaknesses in the budgeting process have also limited the review and evaluation of health policies, reducing incentives to complete reforms in the absence of clear evidence on how much they help to achieve medium-term health objectives. Indeed, many reforms remain in the process of completion, such as those of Family Health Units (Unidades de Saúde Familiar, USF). Shortcomings have also limited the analysis for adopting new health policies to improve the health of the nation, which will increase in importance as demographic factors evolve, such as the ageing population and increase in chronic diseases. Integrating regular reviews of health expenditure in the budgeting process, such as those carried out in the United Kingdom every 2-4 years, could help to formalise the evaluation process.

Despite overall good health outcomes, structural reforms in Portugal’s health sector would help to accommodate pressures from an ageing population and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, while lowering disparities in access to care. Recent OECD cross-country evidence suggests that both supply-side aspects, such as payments to health practitioners and regulations, as well as demand-side features, such as gatekeeping and cost-sharing, can play a key role in regulating healthcare expenditures (de la Maisonneuve et al., 2016[31]). Well-trained general practitioners (GPs) and specialists, evenly distributed across the country, are also crucial to ensure an adequate supply of outpatient care and co-ordination with hospitals and other primary-care providers (OECD, 2016[32]; 2020[33]).

Strengthening primary care

Primary care, which is mostly performed by the public sector, functions as the central pillar of the NHS. Before the 2022 reform, the five regional health administrations were responsible for strategic management of population health, supervision of NHS hospitals, direct management of public primary care centres and providers, and the implementation of national health policy objectives, with further decentralisation since 2018 (Box 2.6). Primary care is provided through a network of 55 local primary healthcare clusters (ACeS), which, until 2022, contracted with the regional health authorities and agglomerate various public primary care centres (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]; Nunes and Ferreira, 2022[34]).

The 2018 reform

In 2018, several competencies were transferred to municipalities, including planning, management and investment in new local primary care centres; management and maintenance of existing primary healthcare infrastructure; management of allied professionals in primary care centres; and participation in health programmes that promote community health, healthy lifestyles and healthy ageing. The reform appears to have improved access to healthcare for people suffering from chronic conditions, and enlarged coverage of services such as mental health, nutrition and oral health (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]; Ministry of Health, 2019[35]).

The 2022 reforms and the Recovery and Resilience Plan

The 2022 reform of the NHS (Box 2.3) foresees that the Central Administration of the Health System (ACSS) and the local primary healthcare clusters (ACeS), which are to receive additional autonomy, will be responsible for contracting the provision of primary healthcare. The five regional health authorities will remain responsible for the approval of these strategic plans and for the planning of resources dedicated to coordination and some public prevention programmes.

The 2022 law also creates local health committees (Sistemas Locais de Saúde), formed by groups of health establishments and other public institutions in the areas of social security, civil protection, education and municipalities. These local committees will elaborate strategic plans and annual plans are approved by the Regional Health Administrations.

In addition, the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) foresees the full implementation of the 2018 reform in some municipalities to make them responsible for Local Health Strategies.

Source: OECD/EOSHP (2021[2]), Portugal: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels; Ministry of Health (2019[35]), Coordenação Nacional para a Reforma do Serviço Nacional de Saúde, Área de Cuidados de Saúde Primários: 2015-2019.

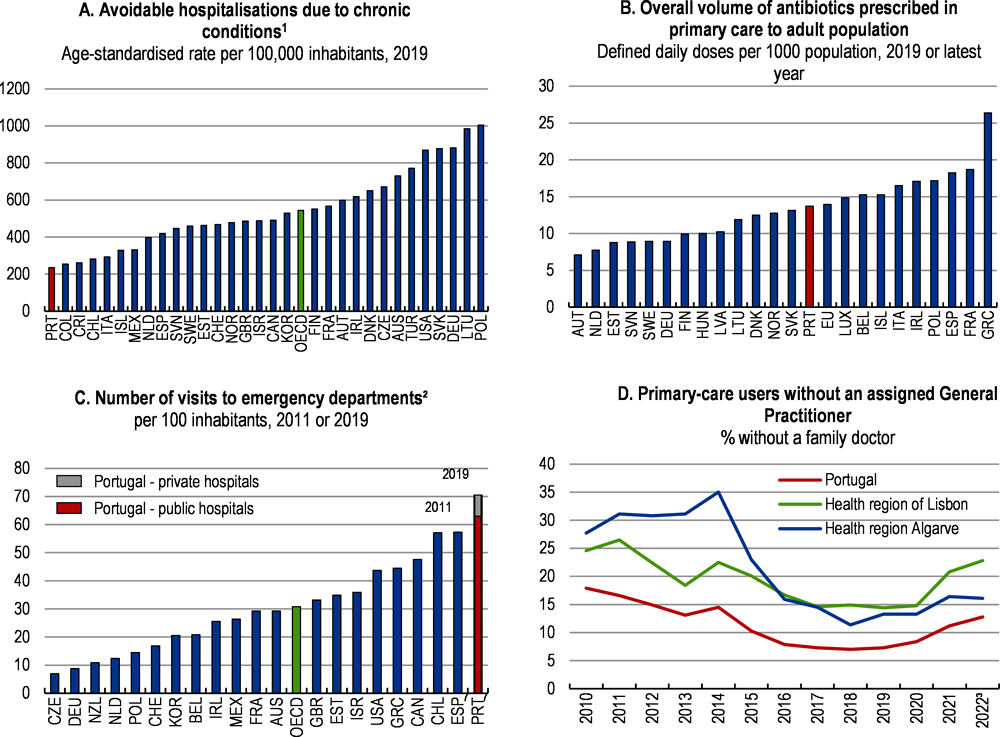

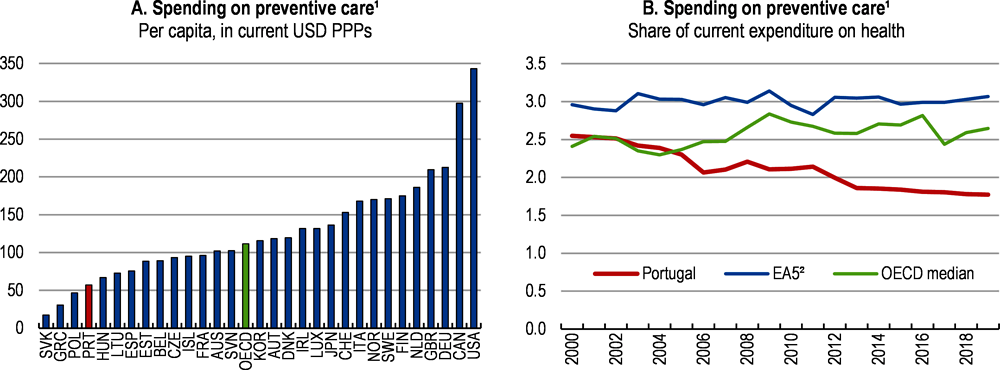

The Portuguese primary care system is generally perceived as well-performing (OECD, 2015[16]). However, some outcomes are mixed, despite the launch of well-designed national action plans. On the one hand, primary care is expected to serve as the first point of contact for people in health systems and to provide continuous and coordinated care over time, notably for people suffering from chronic diseases. Portugal’s hospital admission rates for asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure and diabetes are the lowest in the OECD (Figure 2.8, Panel A; (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2])). The use of antibiotics, which has been validated as a marker of quality in primary care given the rising public health concern caused by antimicrobial resistance (OECD, 2021[13]), also appears below the EU average (Panel B). On the other hand, the use of hospital emergency departments is high, reflecting in part the failure to organise sufficient round-the-clock outpatient services in primary care and the misuse of the hospital care system by patients (Panel C; (Berchet, 2015[36])). The lack of available primary care services is reflected in the number of NHS users not registered with a GP, which lower the quality of patient follow-up (Panel D) and is associated with more frequent complaints about access to services at the regional level (ERS, 2022[37]). Moreover, hospital spending has been rising faster than total health spending, with a declining share of public spending on ambulatory care, while spending on prevention programmes is lagging (Table 2.3).

Reforming primary care would help to address inefficiencies. For example, hospital emergency departments tend to be used for routine needs, which could be dealt with by a GP. Around 41% of emergency visits in Portugal and up to 49% in some regions could be avoided (CNS, 2022[38]). Some targeted interventions to high users of emergency departments have managed to reduce visits by around 50% (Pereira et al., 2001[39]; Gonçalves et al., 2022[40]). Within the RRP 2022 primary care reform, a new typology of emergency episodes in hospital emergency services aims at referring some episodes to primary care services and the measure appears promising. Despite the availability of a 24/7 clinical triage call centre (SNS 24), emergency departments tend to be perceived as “one-stop shops”, where a full range of diagnostic tests can be obtained in a few hours (EOHSP, 2017[15]). In addition, up until user charges for primary care and for services prescribed within the NHS were waived in 2020, low-income populations may have bypassed primary care in favour of emergency services because hospitals were more likely to waive co-payments than local primary care centres.

Strengthening investment and staffing in primary care centres is needed to transform them into “one-stop shops” with ancillary diagnostic and therapeutic service capacity and some specialised care providers. This would help avoid frequent referrals to hospital outpatient and emergency care services. Indeed, GPs act as gatekeepers to specialist visits and are also expected to support the integration of care. The RRP foresees a EUR 466 million investment in primary care centres to provide basic ancillary diagnostic and therapeutic service capacity by 2026 (Box 2.4; (Ministério do Planeamento, 2021[20])).

Beyond the significant planned investments, there is a need to reform the management and structure of local primary care centres, as planned for 2023 in the RRP (Box 2.7). In October 2022, around 1.3 million citizens did not have an assigned General Practitioner (GP), which represents 12.8% of total users in the local primary care centres, and Portuguese GPs spend a large amount of time on non-medical tasks (Granja, Ponte and Cavadas, 2014[41]). The inability to register with a GP is a growing concern, notably in the Health Region of Lisbon and the Southern Health Region of Algarve (Figure 2.14, Panel D; (ACSS, 2022[42])), and translates into long waiting times, high dissatisfaction regarding healthcare access in these regions and higher unnecessary emergency visits (EOHSP, 2017[15]; ERS, 2022[37]; Saraiva, 2019[43]). Currently, one type of organisational structure, the family health units (USF), have much higher ratios of patients per doctor and are generally seen as more efficient (Box 2.7; (CNSP, 2018[44])). Yet only teams interested in evolving into USFs participate in this model (OECD, 2016[45]), while the transition between the two types of USF needs the approval by the Ministry of Health and is limited by yearly quotas fixed by the Ministries of Finance and Health. Further encouraging the convergence towards the USF model and abolishing the yearly quotas for the transformation of existing primary care centres in “USF model B” that benefit from a different payment scheme (Box 2.7) would be positive steps.

The current structure of primary care centres

Public primary care centres are clustered into local primary healthcare clusters (ACeS, Agrupamentos de Centros de Saúde). Each ACeS is mainly composed of family health units (USF) created by the 2005 reform of primary care, as well as traditional primary care centers (UCSP) (Table 2.3). At the same time, shared resource units (URAP) in each ACeS provide dedicated support and include social workers, psychologists, physiotherapists and some dental health technicians. Yet, dental consultations, diagnostic services, haemodialysis and rehabilitation are most commonly provided by the private sector.

The main models of primary care centres have various levels of autonomy and organisational structures (OECD, 2016[45]). The family health units (USF) have some level of autonomy, and participative management and add-on payments for additional services. They are classified in models A and B, based on the way they are organised and on their pay-for-performance (P4P) schemes. Professionals in USF-B receive a monetary incentive for performance, in particular, GPs. In USF-A individual payments are restricted to salaries, but the monitoring of health outcomes results in financial incentives for the team. The traditional primary care centres (UCSP) tend to have vertical hierarchies and a low level of autonomy: their GPs, nurses, and administrative staff are paid fixed salaries.

This heterogeneous structure has been challenging access to care and the convergence of quality across primary care services. In principle, patients have the right to choose between traditional primary care centres and USF. Nonetheless, USF quickly attain the maximum number of patients, leaving no vacancies for new patients to enrol (OECD, 2016[45]). As part of its Recovery and Resilience Plan – RRP – Portugal foresees significant changes to primary care services through additional investments and structural reforms, notably to standardise the primary care models (EC, 2021[14]; Ministério do Planeamento, 2021[20]).

Planned investments

Portugal is to invest EUR 466 million in primary health care services by mid-2026 through its Recovery and Resilience Plan. The foreseen investments include the building of 100 new primary care centres and the refurbishments of existing buildings (EUR 300 million); deepening the capacity for screening and diagnostic services; creating more proactive primary care centres with expanded areas of intervention; correcting local disparities in terms of health equipment; supporting community-based responses and enhancing the skills of the health workforce.

By the end of 2023, Portugal’s RRP aims at (i) broadening the responsibilities and scope of intervention of the local primary healthcare clusters (ACeS); (ii) reviewing the organisation and functioning of the health centres and the related incentive schemes; (iii) developing a risk stratification instrument to support clinical governance in the ACeS; and (iv) further decentralising health responsibilities to 201 municipalities. Moreover, the 2023 National Programme for Access to Oral Health foresees the installation of new dental offices and professionals in primary health care centres.

Source: OECD (2016[45]), Better Ways to Pay for Healthcare, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris; Ministerio do Planeamento (2021[20]), PRR – Recuperar Portugal, Construindo o Futuro, Lisboa; EC (2021[14]), Analysis of the recovery and resilience plan of Portugal, European Commission.

The convergence of management structures among local primary care centres should progress alongside efforts to increase quality, a review of incentive schemes and improvements in access to care. Despite the absence of an ex-post evaluation of its impact on health outcomes, Portugal’s P4P scheme, which amounts to around 30% of the concerned GPs’ incomes, is generally seen as having had a positive impact (OECD, 2016[45]; EOHSP, 2017[15]; Monteiro et al., 2017[46]). Yet, some financial incentives are not promoting efficiency at the level of each primary care centre. Moreover, the number of indicators used for financial incentives is limited, though a broader range of indicators of access, activity and quality is monitored. For example, in “USF model B”, overseeing the training of interns increases these remunerations by around EUR 520 net per month in contrast to other primary care models where GPs are compensated with a reduction in hours, further aggravating difficulties in accessing primary care. Additionally, incentives do not include actual health outcomes and the follow-up of disadvantaged patients (Tribunal de Contas, 2016[47]; Perelman, Miraldo and Russo, 2020[48]), while low-income households are less likely to consult physicians for prevention purposes and to perform screening procedures. The use of geographic and socioeconomic characteristics, as in the United Kingdom or in France, could allow to adjust the payments of the GPs according to their efforts and their population specific needs (Maricoto and Nogueira, 2021[49]).

A review of the incentive scheme in primary care could also raise the quality of care. In Portugal, there are no clinical standards to guarantee the adequacy of prescriptions from primary health centres (Tribunal de Contas, 2014[50]). The systematic use of agreed protocols, to be followed by GPs and other actors to decide whether specific tests are required and how to access them, would help rationalise the use of existing diagnostic facilities, limit the risk of excessive take up and support effective planning. A stronger focus on prevention in primary-care centres should be encouraged by dedicating permanent resources, as well as the provision of better data on how much is being spent in preventive care (see below). The implementation of prevention programmes could also be included in the GPs’ P4P targets, as in Germany or France.

Optimising hospital management and services

Improving hospital management could generate significant efficiency gains and help to reduce waiting times for some elective surgeries. In 2021, the hospital sector was divided between 52 public hospital care providers (including hospitals, hospital centres, one public-private partnership and local health units) and 128 private ones, but public hospitals still accounted for above 70% of hospital expenditures in 2019 despite the growing use of private ones. The number of hospital beds per inhabitant is below the OECD average and has been decreasing for decades, partly linked to the greater uptake of day surgery (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]). Before the pandemic, the number of intensive care unit (ICU) beds was also lower than in most western European countries. Yet, to manage the surge in demand, Portugal nearly doubled its ICU capacity in 2021 (Box 2.1, (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2])). In Portugal, as in other OECD countries, hospitals play a large role for inpatient care services through accident and emergency departments or specialist outpatient units, but they tend to play a larger role for outpatient care, such as consultations or light exams with a doctor without being admitted to the hospital (Figure 2.9). Hospital expenditures have risen quickly to reach 43% of current health spending (4.6% of GDP) in 2020 (Table 2.2), (INE, 2022[21])), while the average length of stay, an indicator of efficiency in health service delivery and care co-ordination, is relatively long.

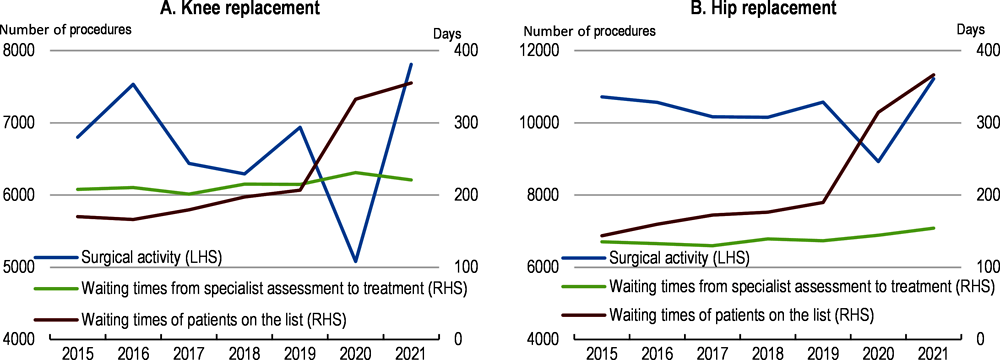

In the short term, the postponement of many elective surgery procedures during the COVID-19 outbreak, is likely to result in further increases in waiting times until the backlog of patients is addressed. Maximum waiting times are regularly exceeded (Tribunal de Contas, 2020[51]). In 2021, the rebound in surgical activities did not prevent waiting times from increasing further (Figure 2.10). Since November 2021, additional payments have targeted surgery procedures, which have longer waiting lists and for which waiting times go beyond the waiting time guarantees (Ministry of Health, 2021[52]).

Strengthening management practices and accountability in public hospitals is crucial to raise their efficiency. The existing financing model has recurrently underfinanced public hospitals, creating a pressing need for ensuring cost control, accountability and efficiency gains. Moreover, the performance budgeting framework is only partly implemented (see above and Box 2.8; (Tribunal de Contas, 2022[25])). Because budget overruns are covered by supplementary allocations, the activity-based system creates limited incentives to encourage cost-containment or efficient practices (EOHSP, 2017[15]). Moreover, the wage bill amounts to 60% of public hospital spending, but managers have little impact on hiring decisions and the careers and wages of public servants and doctors. The current plan to improve hospital performance management is welcome. It aims to reinforce the intermediate management of NHS hospitals, with internal contracts tied to performance incentives and tighter accountability rules for hospital administrations, including general efficiency considerations (EOHSP, 2020[18]). This would help to define and follow up on objectives, alongside with more autonomy to meet objectives and make decisions.

Public hospitals are funded through global budgets, with some role for a diagnosis-related groups (DRG)-based payment system, which allocates funding according to the expected number of stays, patient pathologies and tariffs. The DRG component accounts for nearly 50% of hospitals’ financing, while the remaining revenue comes from fee-for services (for outpatient visits), bundled payments (for some chronic conditions), fees (for emergency visits) and some quality-based payments (OECD, 2015[16]). The DRGs are used to set the budget given to the hospital, but they do not define a payment episode by episode. In principle, the DRG-based tariffs cover the full costs of treatment for a patient in a particular DRG.

Source: OECD (2015[16]), OECD reviews of health care quality: Portugal 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Strengthening human resource management and hospital autonomy could improve patient care and working conditions. The rigidity in staff management has led to a rise in the costly use of consultant contracts from independent service providers, potentially worsening patient outcomes and working conditions. In addition, the governance of university hospitals is complicated by the different affiliations of staff to universities, other public and private hospitals and the lack of coordination among them (see below). At the same time, public managers have little autonomy regarding investment decisions, which may be an obstacle to an effective implementation of the contract system, as this hinders the restructuring of public hospitals and the potential to realise efficiency gains. The ongoing reform of the hospital management system, which will ensure the nomination of hospital management boards by the new “CEO” of the NHS, appears as a positive step to limit the risks of political interventions.

Ensuring more integrated care

Effectively integrated care services will be critical to provide high-quality healthcare for the growing number of patients with chronic conditions and multi-morbidity. This will require successful coordination across different care providers (Barrenho et al., 2022[53]). Portugal has long initiated processes to support integrated care. Since 1999, the roll-out of eight local health units (Unidades Locais de Saúde, ULS) has promoted the vertical integration of different levels of healthcare, with the joint management of hospitals and primary healthcare units in some geographical areas covering around 12% of the population. Yet, the results of the existing local health units appear mixed (Gonçalves et al., 2011[54]; ERS, 2015[55]; Gonçalves, 2015[56]; Lopes et al., 2017[57]; OECD, 2015[16]; Cruz et al., 2022[58]) and coordination among providers is not optimal and has been identified as hindering the strategy for dimentia (Balsinha et al., 2020[59]; Barrenho et al., 2022[53]).

Further innovations in organisation structure could help to improve coordination among providers and address shortages. In recent years, Portugal has adopted a number of organisational changes that increased the involvement of primary care, including the use of digital consultations or tele-expertise between primary health care teams and specialists, and the establishment of mobile health clinics (OECD/EOHSP, 2021[2]). The new Portuguese governance structure introduced in 2022 should ensure that the four new local health units (ULS) planned in 2023 and the new units to be established under the planned generalisation of the ULS model have an adequate degree of autonomy to fine tune service delivery, as well as the organisation of their operations, based on the specific needs of their patients. It will also need to strengthen further coordination of care delivery beyond the local health units, by establishing effective new care networks and defining responsibilities to primary care providers for providing well-coordinated care. For example, though most physicians work in group practices, the development of structures for out-of-hours consultations with local non-hospital doctors and other health professionals could offer better geographic coverage, around-the-clock availability and continuity in the course of treatment. The adoption of new service platforms like intermediate care could build on the existing network of local health centres, as well as a larger roll out of the existing mobile health clinics and hybrid models of care (face-to-face and telemedicine).

Such structural changes will need to be supported by a review of the payment schemes of GPs and other providers to promote the delivery of integrated care services. Since 2009, the existing local health units have been financed through a mixed model including an adjusted capitation, pay for performance, and service level agreements, which take into account patient flow to and from their geographical area (OECD, 2015[16]). Yet, payments for performance account for around 10% of their budgets, of which 2% are directed towards avoidable hospital admissions (ACSS, 2022[60]; OECD, 2017[61]). In 2023, the planned creation of the four new local health units will include the analysis of the clinical and financial impacts of this form of organisation, aiming at ensuring an effective integration of care. More generally, a review of payment systems should aim to reward more multidisciplinary care, notably for patients suffering from chronic conditions who rely more on coordinated care between different providers. This could build on the framework of Norway’s “Distriktsmedisinsk senters”, where payments encourage a discussion between hospitals and primary care providers about issues, such as the management of patients discharged to the community, ways to avoid unnecessary hospitalisation, the organisation of follow-up and post-acute care (Box 2.9, (OECD, 2017[61]; 2014[62])).

A distriktsmedisinsk senter (also called Sykestue) is an intermediate care facility, halfway between hospital and primary care, where people are admitted for a few days and cared for by primary care practitioners working closely with hospital specialists. Some facilities only provide specialist care, while others provide a shared model of care between primary and secondary settings (OECD, 2017[61]). These institutions are often co-located with other municipal health services (EOHSP, 2020[63]).

The development of the shared model of care took place in the 1980s, and it was more broadly rolled out in rural parts of the country from 2012. This encouraged experimentation with and diffusion of such facilities to provide high-quality health care more conveniently, particularly for the elderly, and vulnerable populations that find it difficult to travel long distances.

Source: OECD (2017[61]), Caring for Quality in Health: Lessons Learnt from 15 Reviews of Health Care Quality, OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality, OECD Publishing, Paris; EOSHP (2020[63]), Norway Health system review, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Revising legislation to make better use of the skills of health professionals could also ease such changes. The training and qualifications of nurses and allied health professions currently encompass wide-ranging and substantial knowledge, but their role in the health system has not changed and the health system remains centred on physicians (EOHSP, 2017[15]). Family Nurses created in 2014, which are in charge of promoting healthy lifestyles and prevention, covered 85% of all patients accessing care through the public system in 2021 (ACSS, 2022[42]) and are a positive step. Yet, the responsibilities assigned to Portuguese nurses also falls short of some other OECD countries, despite their rigorous four-year, university-level training. For example, family nurses remain legally unable to prescribe medicines, although this could significantly relieve doctors. Midwives, qualified nurses who have undertaken an 18-month specialisation, have a more limited role than in other European countries. In 2016, the Portuguese Court of Auditors recommended a greater role for nursing care centred on a family nurse to free some of the duties of doctors (Tribunal de Contas, 2016[47]). Implementing this recommendation could help to address shortages of healthcare workers in a cost-effective manner.

More generally, reallocating tasks to better harness the skills of pharmacists, nutritionists, and nurses, whilst remunerating these professions, accordingly, could help to improve both patient outcomes and the efficient use of the health workforce. Professional bodies still play a strong role in task allocation. Portugal could make better use of health professional bodies to help develop regulation and standards and adjust to a rapidly changing environment. In addition, the initial education and lifelong learning of health professionals could include more joint training and practices among GPs, specialists, nurses and pharmacists to improve coordination over the medium term.

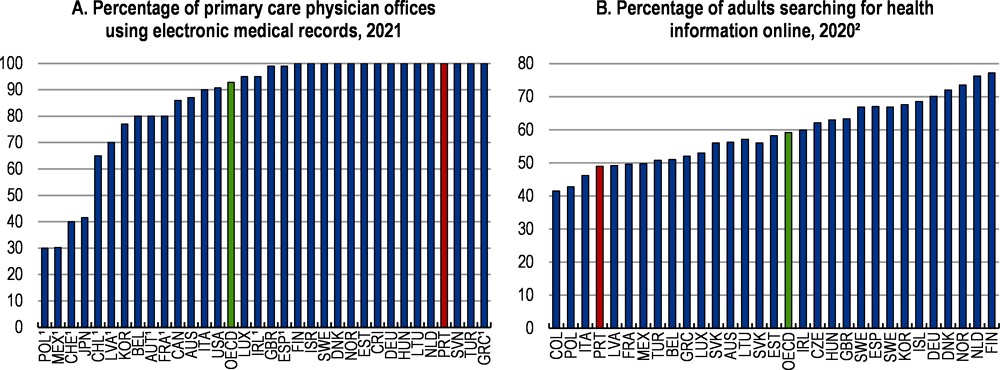

Portugal is a frontrunner in the uptake of digital technologies in healthcare services (OECD, 2021[64]), but the fragmentation of health data hinders comprehensive care, individual patient empowerment and the use of health data for health system improvement (Figure 2.11). Key national health data remain fragmented across providers and standardised electronic medical records ensuring their interoperability have not been widely disseminated (OECD, 2022[65]), leading to low or inefficient use of electronic health records (Tavares and Oliveira, 2017[66]). OECD estimates point at yearly investment needs worth 0.3% of GDP (Morgan and James, 2022[67]). The welcome investments planned under the RRP notably include new hardware and software for health workers, the standardisation of the public information systems and better access to data by the end of 2024 and 2025Q3 in the Azores (see above). This should build on the OECD guidance on Health Data Governance (OECD, 2017[68]; OECD, 2022[65]) and the establishment of a national health data governance framework to develop integrated health information. This would notably help the development of integrated digital platforms for the scheduling and management of consultations, ancillary diagnostic and therapeutic services, hospital admissions and surgical interventions, as, planned through the “SNS Portal”, which aims to provide registered users with access to their medical records, as well as online prescriptions and appointments.

Beyond information sharing, digital healthcare technologies could improve the quality and efficiency of care. As e-prescribing is the norm in Portugal, there is significant potential to use additional Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools to diffuse good practices and make greater use of these data. For example, some initiatives promote the use of generics and biosimilars, such as the app “Farmácias Portuguesas” while the “Sifarma Clínico” software allows for the following-up and monitoring of volunteer patients in community pharmacies (PGEU, 2021[69]) or the “ePatient” software in public hospitals (OECD, 2021[64]). Yet a broader use of statistical tools will require new legislation to increase access to data (OECD, 2022[65]). Allowing a safe and broader access to health data could build on the experience of other OECD countries. For example, the French government announced the creation of a Health Data Hub in 2019, with an expanded set of information and enhanced regulated access to the datasets. The first selected projects included public institutions, start-ups and larger firms (MSS, 2019[70]).

The cooperation between public and private providers should also be strengthened and better monitored to ensure more equal access and better efficiency. The relationship between the NHS and private providers remains overall limited and often based on one-off contracts, while competition appears weak for some contracted services (Barros, 2017[71]; AdC, 2022[72]). Three PPP hospitals that were widely seen as successful have been transferred back to the public sector. According to the Court of Auditors, their performance in terms of quality, effectiveness and access indicators was in line with the average comparable publicly managed hospitals, but the PPP hospitals had lower operational costs (Tribunal de Contas, 2021[73]). Moreover, in areas where access to private services is relatively easy, private providers allow high- and middle-income patients with voluntary or some specific public insurance schemes to jump the queue in the public system, creating perverse incentives for doctors working in both the public and private parts of the system. A first step is to fully ensure the interoperability of information systems to improve transparency. Indeed, private hospitals and other providers that run a large share of blood tests and imagery tend to have their own information systems, which were integrated into national patient records at the end of 2022.

Shortages of staff like doctors and nurses hamper access to quality healthcare for some types of care in the NHS and in some geographic regions. Shortages particularly affect access to general practitioners (GPs) working for the NHS. At the same time, Portugal is facing a wave of retiring doctors in the coming years, particularly GPs as well as some specialists. There is also significant scope to increase the use of nurses. These challenges are more pronounced in some regions than in others but will ultimately require increasing remuneration and improving working conditions and training opportunities for doctors and nurses to increase the attractiveness of working for the NHS, which are priorities in the reforms currently underway (Box 2.3, Box 2.4 and Box 2.7).

Opportunities for skill progression in the NHS have been held back by a lack of investment in technology and innovation over the past decade, limiting the number of healthcare professionals who work with the latest technology. Increased investment in equipment, facilities and IT tools under the government’s Recovery and Resilience Plan will help to address previous low investment (Box 2.4). The NHS could also provide more financial and time resources for continuous training, which would boost skill levels and career progression.

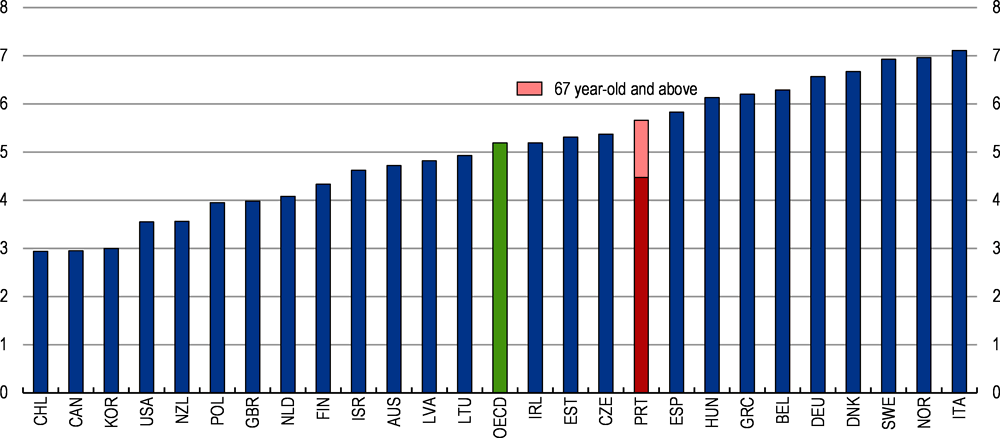

Improving the supply of general practitioners and specialists

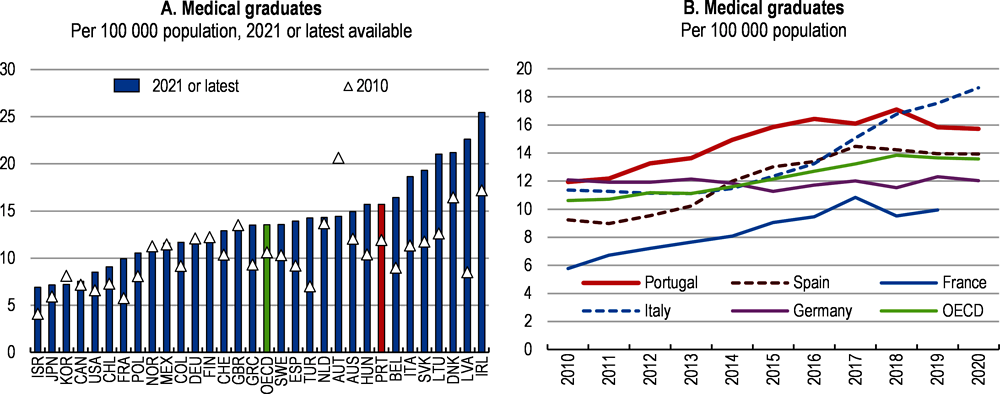

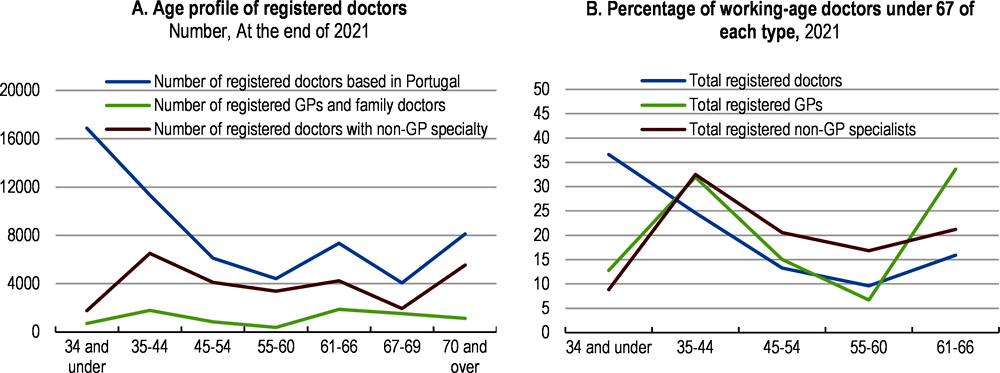

The number of registered doctors per capita in Portugal is around the OECD average, in part supported by an increasing number of medical graduates over the past decade (Figure 2.12 and Figure 2.13). While most OECD countries compile data on both registered and practicing doctors, in Portugal there are only data on registered doctors. Registration is a legal requirement but does not imply active practice in the country. When excluding doctors aged 67 and over, perhaps a better approximation of the number of doctors potentially practicing, the share of registered doctors per 1000 population falls from 5.7 to 4.5.

While the number of registered doctors is around the OECD average, there is an uneven age profile of doctors. Around 25% of registered working-age doctors are aged between 55 and 66 (Figure 2.14). However, as doctors over 55 are exempt from emergency work in the NHS, this age profile is creating shortages in emergency services that would not occur with a more even age distribution (Pereira da Silva et al., 2022[74]). The share is particularly elevated for some specialties. For example, 46% of obstetricians and gynecologists working in NHS hospitals were over the age of 55 in 2020 (Pereira da Silva et al., 2022[74]).

This uneven age profile of doctors is also leading to a forthcoming wave of retirements. Around one in three registered working-age GPs and one in five registered working-age non-GP specialists are currently aged between 61 and 66 and close to the 2023 legal retirement age of 66 years and 4 months (Figure 2.14). This cohort is followed by a small group of doctors currently aged between 55 to 60 and as such, the number of retirements will ease. These large fluctuations are partly due to a decline in medical graduates between the revolution in 1974 and the establishment of the NHS in 1979.

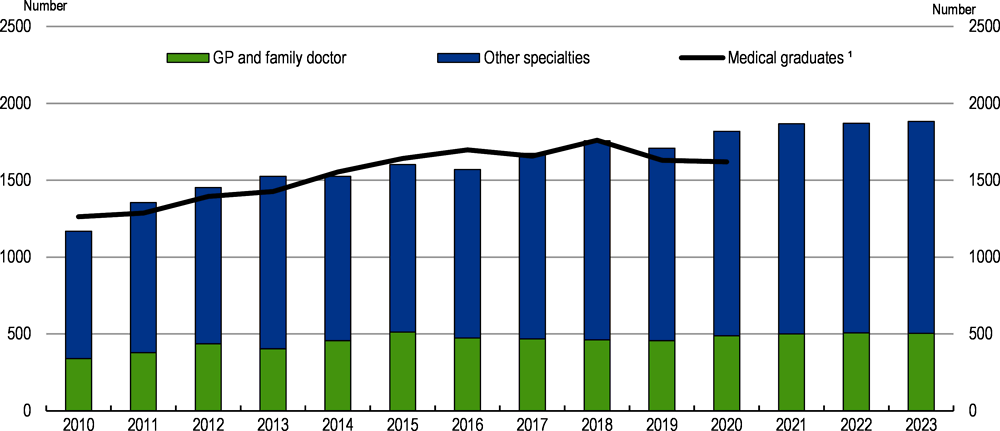

The number of specialist training positions has continued to increase over the past decade, although the new cohorts of graduating GP or specialist doctors will not be sufficient to replace the forthcoming retirements and address the current shortages (Figure 2.15). For example, around 460 GPs should complete their training in 2023, given the four-year programme, reaching 500 per year by 2025. This compares to the around 370 GPs who on average will reach retirement age over the coming years, given the number currently aged between 61-66. The number of GP and specialist residency positions was greater than the number of medical graduates in 2019 and 2020; however, the number of positions has plateaued since 2021.

A more analytical and independent approach to determining the number of postgraduate medical placements could help to make the allocation process more focused on the projected supply and demand of doctors. The number of specialist training positions offered each year is jointly determined by the ACSS and the Portuguese Medical Association. The Medical Association is responsible for certifying the capacity of each institution to receive residents for postgraduate medical training, which helps to ensure a high-quality programme (EOHSP, 2017[15]). The performance of this task by an independent government agency could provide a more robust and impartial view. Additionally, if this agency were better placed to determine the scope to increase institutions’ training capacity, this could help to more quickly adjust the offered number of training positions to meet projected demand.

While the number of registered doctors is around the OECD average, within the NHS there is a lack of GPs, which is limiting access to primary care and there are shortages of some medical specialists. In October 2022, over 1.3 million or 12.8% of users registered with the NHS were not registered with a GP, which limits the quality of patient follow up (Figure 2.14, Panel D). Around 770 GPs would be needed to fill this gap, assuming each GP could take on the average number of registered users in USFs in 2022 (Table 2.3). The National Register of Users (RNU) is currently being updated, which will provide more accurate information on shortages and health needs. Since even before the pandemic, waitlists for some specialties have been high (see above).

Access to a GP is particularly limited in some regions. While in the Northern region only 2% of users are not registered with a GP, this share increases to 23% in the Lisbon and Tagus Valley region. Regional GP shortages can add to other challenges, such lengthy travel distances for some rural populations to reach their nearest GP (OECD, 2015[16]). As the population has become increasingly concentrated around Lisbon and Porto and the more densely populated coastal areas, inland areas, which have a more elderly population, have become more scarcely populated. These long travel distances can be a particular challenge for frail elderly citizens. In some regions transport services are available and primary care providers in a mobile practice visit villages without a local GP and access to digital consultations has increased (see above). Medical and nurse-provided home care are also more common in less densely populated areas.

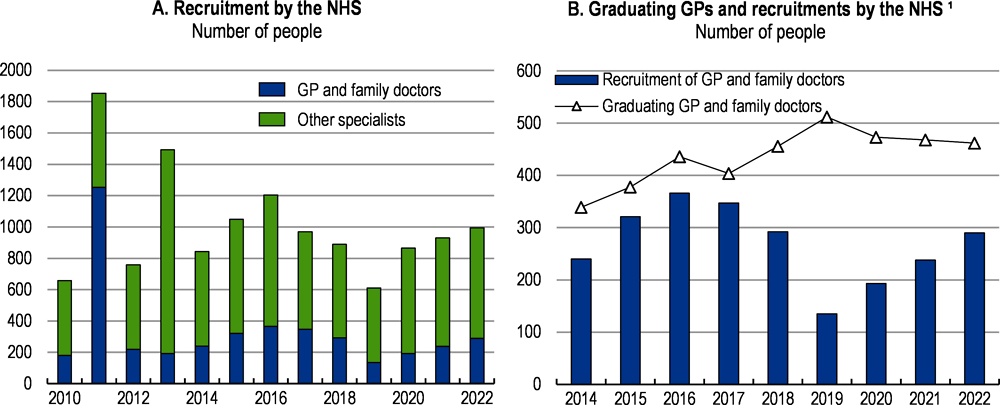

The NHS has been struggling to address the shortage of doctors through increasing recruitment. The government has been posting more vacancies than recent graduates since 2018 to attract doctors working outside of the NHS. For example, in the first, and largest, recruitment competition in 2022, the government announced 1636 vacancies for 1220 newly trained GPs and specialists (ACSS, 2022[42]; Público, 2022[75]). In addition, a simplified selection procedure with a view of recruiting 731 practitioners was launched in December 2021 and the 2022 agreement with Portuguese-speaking countries aims to attract migrant caregivers. Nevertheless, the recruitment of GPs and specialist doctors has been relatively low since 2017 (Figure 2.16, Panel A). The government has also struggled to attract recently qualified GPs, with a growing gap between the number of GPs completing their training and those accepting positions in the NHS (Figure 2.16, Panel B).

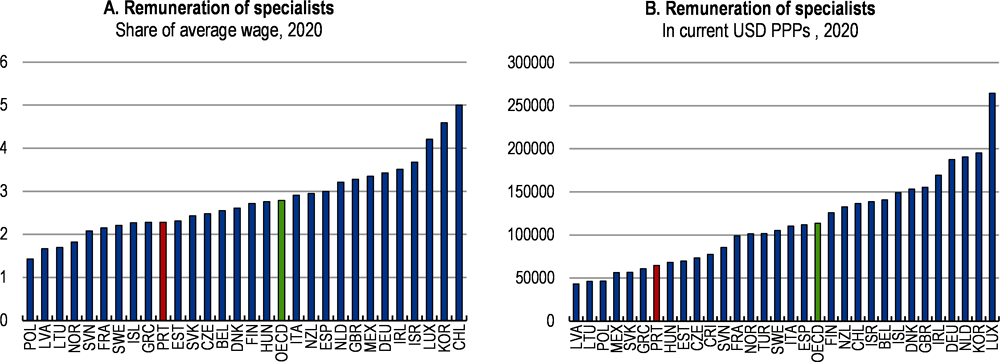

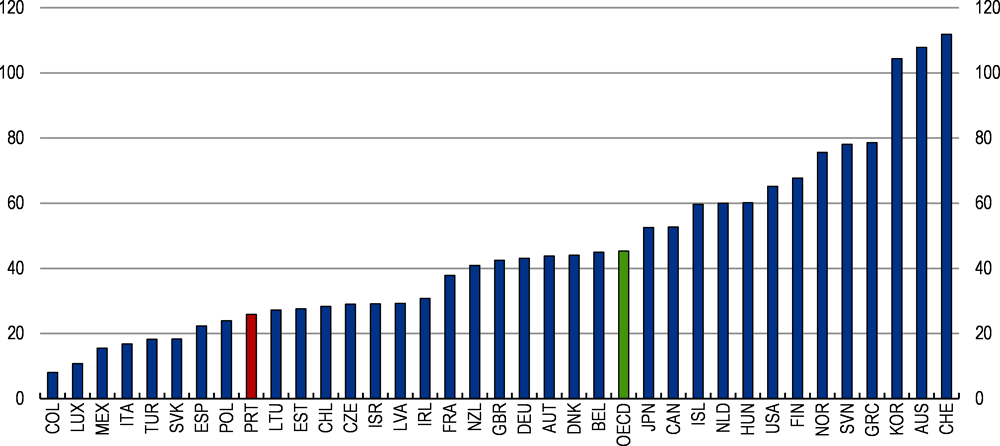

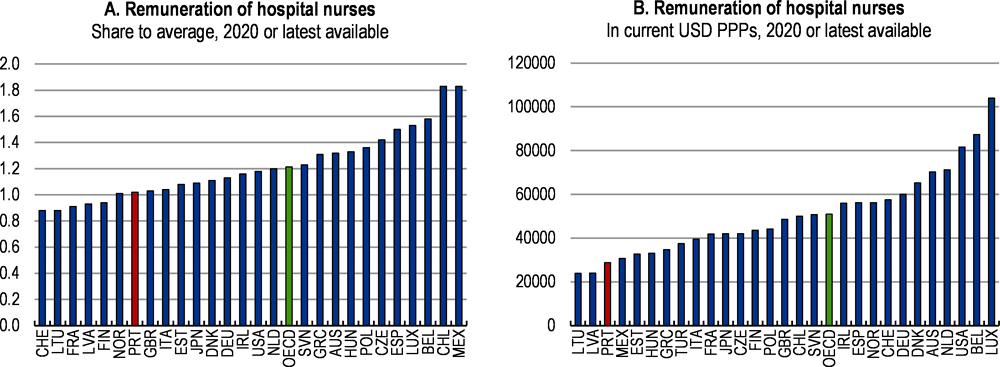

Disadvantageous working conditions in the NHS, including low pay and few training opportunities, are making it more attractive for doctors to work in the private sector or abroad. Remuneration for an NHS specialist doctor was 2.3 times the average wage in 2020, compared to 2.8 in the average OECD country (Figure 2.17, Panel A). International comparisons of nominal salaries adjusted for differences in purchasing power are even less favourable (Figure 2.17, Panel B). Between 2010 and 2021, real remuneration in euros fell by 21% for specialists and 28% for GPs (OECD, 2022[4]). Salary progression in line with experience is very gradual, limiting increases in remuneration and recognition for the completion of additional training. Remuneration is rarely linked to performance, reducing incentives for high performance. Increasing remuneration towards the OECD average and providing opportunities for regular increases, in line with performance and skill progression, would provide greater financial incentives to work for the NHS and better reward high performance.

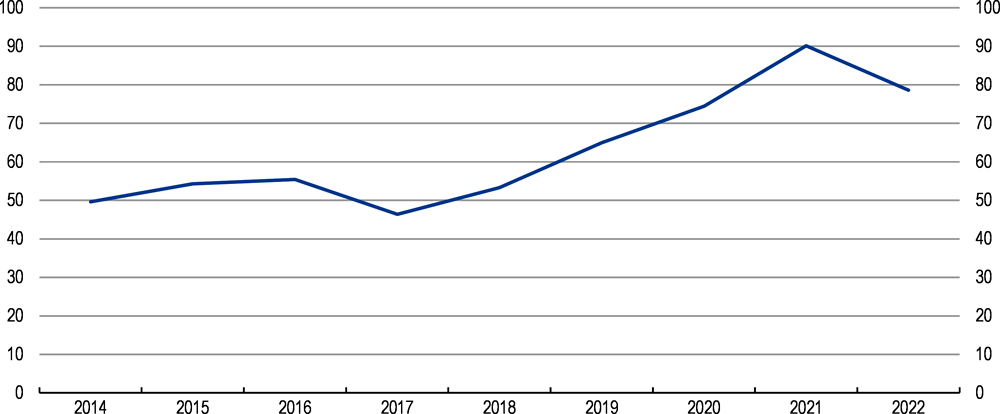

Reviewing the wage-setting mechanisms across types of primary care centres (see above) and improving working conditions in the NHS by reducing overtime hours and increasing the flexibility of work could help to attract and retain doctors. In the NHS, doctors work 40 hours per week and can work an additional 12 hours providing emergency services (with increased remuneration). The use of overtime hours has increased in recent years (Figure 2.18). Facilities with particularly elevated shortages and overtime hours will likely particularly struggle to attract staff, perpetuating a vicious circle. However, reducing overtime hours may temporarily reduce the provision of healthcare until shortages are addressed. Expanding flexibility around time schedules, part-time work and increased opportunities to manage work alongside personal and family commitments would increase the attractiveness of working for the NHS, although it could temporarily aggravate shortages. Increased flexibility could help to support working parents, and particularly women, who made up almost 60% of Portuguese registered doctors in 2021 (INE, 2022[76]).

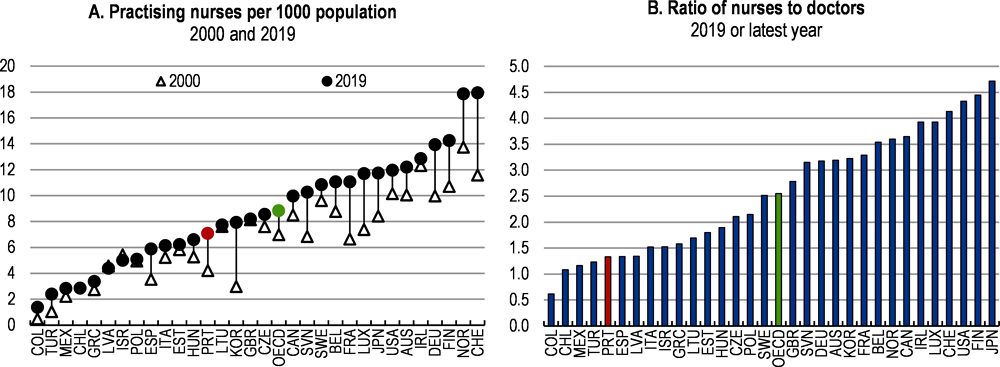

Addressing the shortages of nurses