3. Calls for greater social protection – if the price is right

The year 2020 was marked by high levels of anxiety – around personal health and economic security, prospects for the future, and concerns about the effectiveness of social protection in the face of a pandemic and an economic crisis.

OECD governments innovated quickly, expanded and enhanced coverage of social programmes, and implemented a battery of additional emergency measures to address serious threats to personal health and economic security in 2020. Nevertheless, many national, regional and local governments struggled to respond efficiently and thoroughly to save human lives and livelihoods. Issues like institutional capacity and inadequate funding sometimes hampered the effectiveness of COVID-19 social protection measures (OECD, 2021[1]).

As a result, despite unprecedented efforts in the provision of social protection, RTM 2020 reveals that many people are dissatisfied with their government’s approach. Most would prefer a more expansive and higher quality safety net, even if they have to pay for it in the form of higher taxes. Most people are calling for higher taxes on the rich to help the poor. These results are in line with the results of RTM 2018, though attitudes have sharpened – especially among those who suffered economically due to COVID-19.

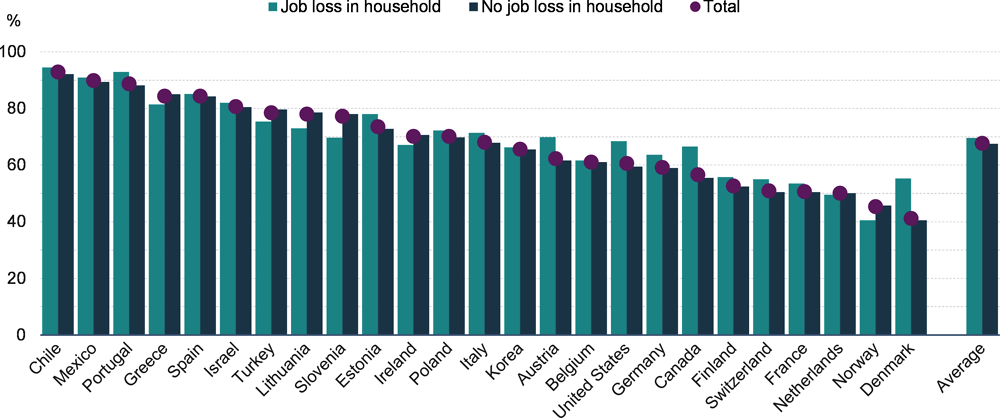

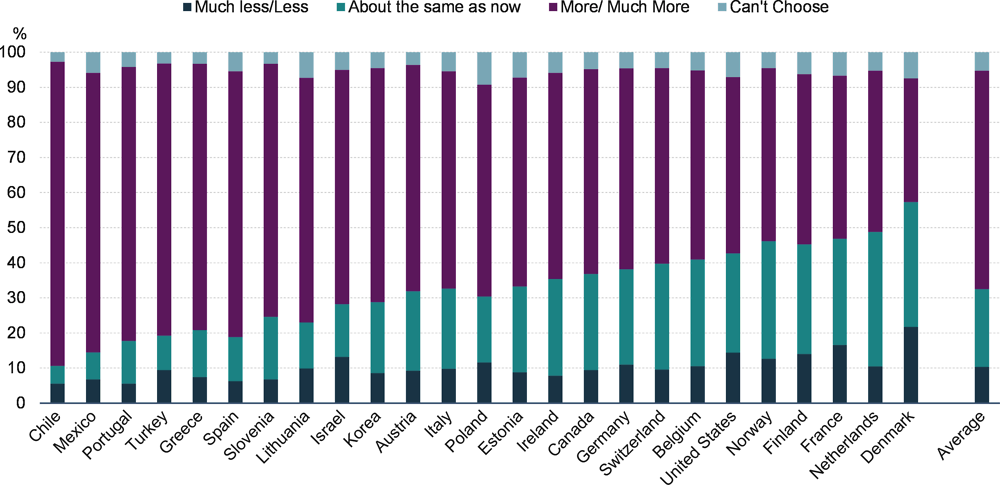

The vast majority of respondents throughout the OECD call for either more spending to protect their economic and social security or for a continuation of current levels of spending. On average, 67.7% of all respondents say they think government should be doing more. Rates range from 41.2% in Denmark (where the social protection system is well-developed) to 92.9% in Chile. A majority of people in all but two countries –Denmark and Norway – say that government should be doing more. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in most countries, respondents whose household experienced job loss during COVID-19 were more likely to call for greater government intervention (Figure 3.1).

In countries where there is relatively lower support for additional social spending, it is worth noting that most of the rest of the respondents want those countries to continue to spend at the same level at which they currently do. 43.7% of respondents in Denmark, 27.3% in France, 35.95% in the Netherlands, 41.5% in Norway, and 34.4% in Switzerland say that they want government to spend about the same amount as they do now. France leads in the share of respondents who say they want government to spend less (15.3%), followed by Poland (12.2%), Turkey (11.6%) and the United States (11.3%).

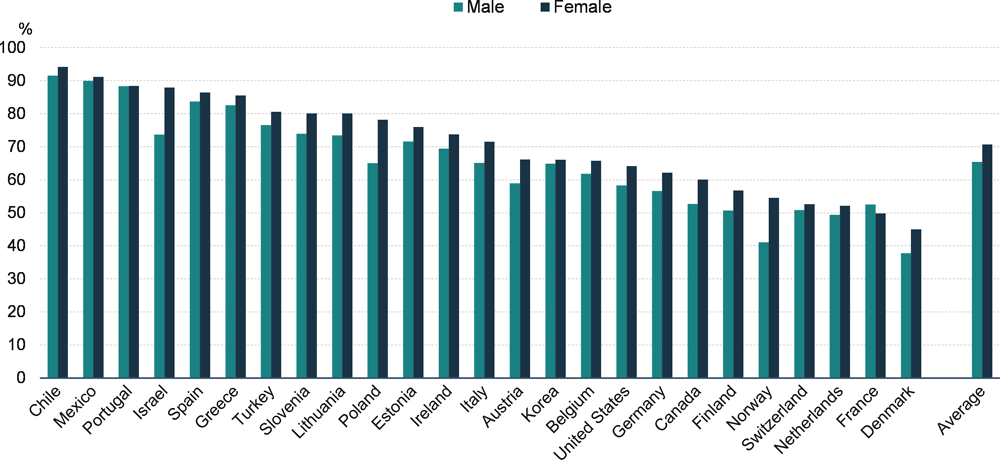

On average across countries, women are 5 percentage points more likely than men to say that government should be doing more to ensure their economic and social security – perhaps reflecting the higher perceived economic risks many women cite.

“The main challenge I have in the coming months is to keep my job. My company has already said it is not ruling out layoffs if the pandemic continues to affect people across the board. The government should help companies not lay off so many people. Although I realise that that is difficult.”– 46-year-old woman, Spain

The delivery of social programmes comes at a cost to the government and to taxpayers, of course. The fiscal cost of social spending has not been at the forefront of policy discussions thus far, as generally OECD governments have recognised that they need to do “whatever it takes” to protect people and jobs during the crisis (OECD, 2020[2]). Yet most governments are borrowing at unprecedented levels (at least in peacetime) to survive the crisis (OECD, 2020[17]). Budgetary costs and hard decisions about which programmes and populations to prioritise will surely become more pressing political issues as governments move into the recovery period. RTM attempts to gauge the political feasibility of specific reforms by reminding respondents of the cost of social protection.

When respondents are primed to consider the tax and social contribution costs of specific expansions in the welfare state, support for government spending decreases relative to when people are simply asked whether government should do less, the same or more to ensure their security (Figure 3.1).

Nevertheless, even when asked to consider cost, a sizeable degree of support for social protection spending remains – at least for specific programmes. When primed with a fairly general reminder of the cost of social programmes, a majority of respondents in all 25 countries voice support for greater spending in at least one policy area, but typically more.

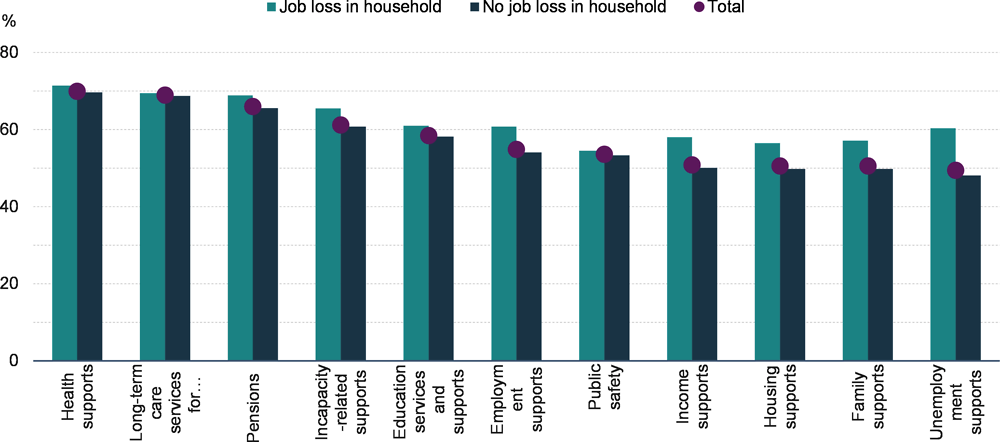

When considering the taxes they might have to pay and the benefits they might receive, seven out of ten respondents across countries say that they would support greater spending on public health services – the most popular issue area (Table 3.1). Health services are also the top spending priority in 12 of the 25 countries surveyed in RTM 2020 (Figure 3.3).

There are many potential drivers of this result showing respondents’ view of health services. The presence of a global pandemic surely encourages greater prioritisation of health care provision, though health was also a top perceived risk in RTM 2018 – it is a risk everyone shares. The desire for greater health care spending may also be related to the aforementioned result that people are most satisfied with health care provision – suggesting that people may be more willing to invest in services that they feel are provided (relatively) well.1

Perhaps related to their economic insecurity, respondents whose households lost jobs during COVID show a stronger willingness to pay more in taxes to receive better social protection. There is especially strong support in this group for better investments in employment supports (e.g. job search services, skills training, access to entrepreneurial funds), unemployment supports, and income supports like minimum income benefits (OECD, 2021[1]).

Across countries, 60.3% of respondents whose household experienced job loss say that – thinking about the taxes they might have to pay and the benefits they might receive – they would like the government to spend more or much more in order to provide better unemployment supports (e.g. unemployment benefits). This figure stands in contrast to the 48.1% of respondents who did not experience outright job loss during COVID who call for greater government spending on unemployment supports – though this is, of course, still a large share. In Austria, Canada, Finland, Slovenia, and the United States, the preference gap between people whose households lost jobs and those who did not is greater than 20 percentage points. This is a sizeable divergence in preferences following COVID insecurity.

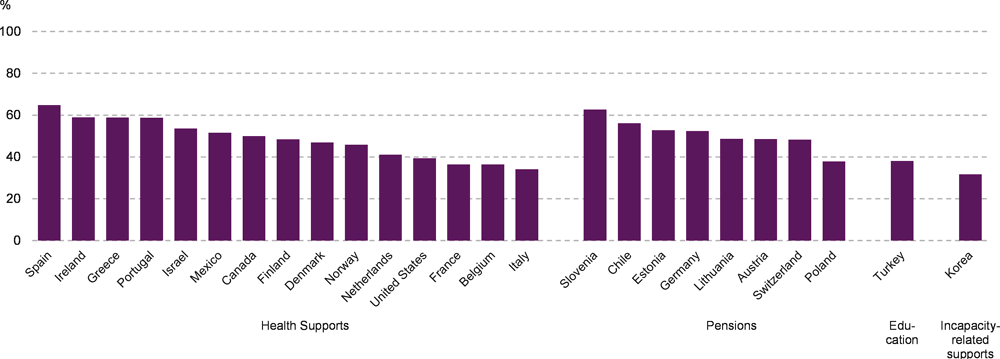

The next set of questions put a price tag on social programmes: an additional 2% of income in taxes and social contributions. People are most willing to pay more for better provision of health care, again, but faced with the 2% figure, the share supporting spending more in this policy area drops to 44.7%, on average, across countries (Table 3.2) – down from 70% when the cost is described more generally (Table 3.1).

“If I am unemployed [after college], I would need to rely on a different source for my basic needs, as my parents expect me to not rely on them after graduating. To address this, I hope the government can provide better resources for those who are unemployed, not just for sustenance, but also so they can find a job and escape that difficult financial situation.”– 20-year-old woman, the United States

Pensions are the issue where respondents are second-most likely to support paying an additional 2% of income in taxes and social contributions, on average across countries (Figure 3.5). This could of course be related to the personalised nature of pension contributions, as many countries have links between lifetime contributions and individual benefits received in retirement. Using the “2% of income” definition of cost, support for pensions is greatest in Slovenia: 62.7% of respondents there say they would favour spending more on pensions, even at the cost of an additional 2% of income.

Importantly, this specific price tag proposes the same rate to all respondents; it does not account for redistributive preferences in terms of who should pay.

Much of the discussion thus far has focused on what might be considered the social insurance function of the welfare state – health care, pensions, unemployment insurance and so on, which provide people with a degree of support at specific moments in the life cycle.

When thinking about the redistributive function governments play in reducing income inequality, respondents across countries are generally supportive of government intervention. On average across countries, 62.2% of people say that government should do more, or much more, to reduce income differences between the rich and the poor by collecting taxes and providing social benefits (Figure 3.6).

The countries where people are least likely to call for more redistribution – Denmark, the Netherlands, France – tend to have already relatively high levels of redistribution. These countries also have relatively high levels of satisfaction with current redistributive measures. Across countries, very few people say that government should be doing less to reduce income differences. The cross-national average calling for less intervention to reduce inequality is 10.3%.

“In Mexico, no [political] party has done enough to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor. There have been some attempts, like a very low pension for seniors, but they are very low amounts.”– 59-year-old man, Mexico

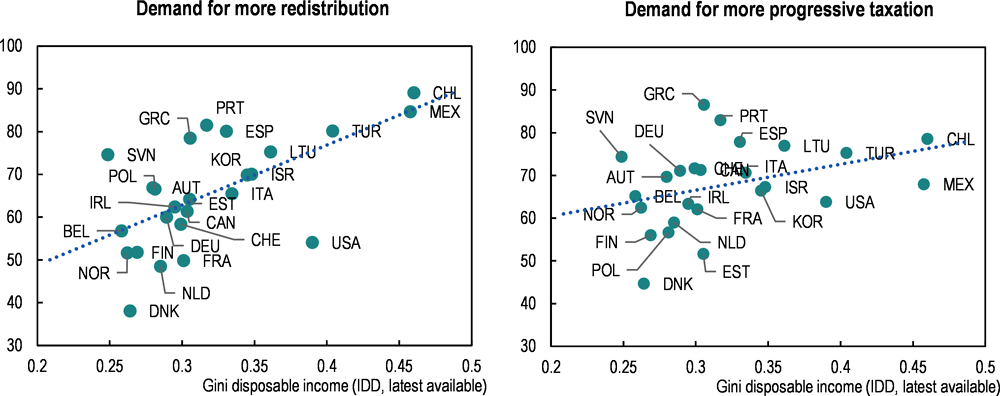

When asked specifically whether government should tax the rich more than they currently do in order to support the poor, 64.5% of respondents, on average across countries, reply “yes” or “definitely yes”. This is slightly lower than the cross-national average in 2018, but since 2018 the rate also increased more in countries that are more unequal (OECD, 2021[18]). There is a slight positive correlation between the degree of income inequality in a country, measured by Gini, and demands for more redistribution and more progressive taxation (Figure 3.7) – suggesting that people are responding to inequality with demands for more redistribution. There is also a positive association between experiencing financial hardship during the pandemic and calls for greater redistribution (OECD, 2021[18]), similar to the findings looking at preferences for spending on specific programmes (Figure 3.4).

Note

← 1. Some of the tax morale literature supports this idea, finding that effective public programmes and interactions with competent and respectful public authorities help drive tax compliance. Seminal works include (Barone and Mocetti, 2011[19]) and (Feld and Frey, 2002[20]). More recent experimental literature has also found positive relationships between the quality of public services and willingness to pay taxes (see for example (Ortega et al., 2016[21]).