1. Key policy insights

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Italy hard, triggering the deepest recession since the Second World War. The government has prioritised bringing the health situation under control, and generously supporting livelihoods and firms. The economy is recovering as the vaccination campaign has expanded. Growth has broadened from manufacturing and investment to include services and consumption. The banking and non-financial corporate sectors are stronger than the start of the sovereign debt crisis. Together with the efforts to preserve economic capacity, this has helped the economy rebound.

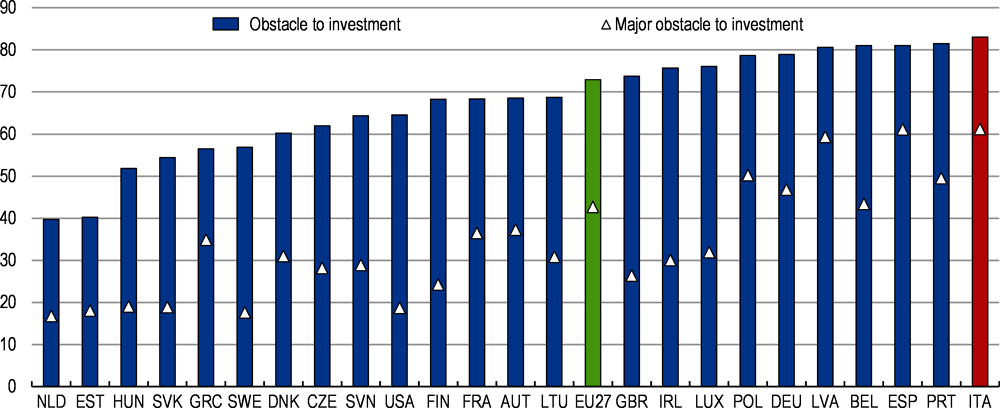

To reverse the trend of stagnant real per capita GDP, the economic recovery must address the obstacles to higher rates of investment, productivity and employment. Too few firms are created and once they exist, they grow too slowly. Skills levels are low and emigration is high. Despite numerous legislative reforms, implementation tends to lag, with large gaps in public sector effectiveness affecting spending outcomes. Lengthy court disputes, investment approvals and other business processes reduce investment, as does regulatory uncertainty in critical areas such as green investment. With an ageing and fast-shrinking working age population, future growth will be very dependent on lifting investment, developing skills and raising the productivity of firms to the levels of Italy’s top performers.

The National Plan for Recovery and Resilience outlines a set of structural reforms in public administration, civil justice and competition that will remove obstacles to growth and facilitate the financing of investments in faster, greener and more digitised growth. The scale of spending (EUR 235 billion), the broad scope of reforms, and the tight link between reforms and spending could amplify the potential growth and confidence impacts of reforms and investments. Implementation requires a more effective public administration, the focus of the special chapter of this Survey. Public finance reforms can allow more growth- and equity-enhancing spending, and lower the drag of the tax system on job creation.

Against this background, the main messages of the Survey are the following:

Policy should remain supportive and increasingly targeted until the recovery is well underway. Faster growth will help to lower the public debt-to-GDP ratio. A medium-term fiscal plan needs to be established to reduce the public debt ratio, taking into account the future impact of an ageing population.

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan requires implementing a demanding legislative and administrative reform agenda. Acting now to make the public administration more effective should include: revising budget allocations and regulations based on outcomes; a more agile public workforce; and, better leveraging the roles of different levels of government and private providers.

There is considerable room to improve the composition of spending and taxation to support higher skills, employment and investment, whilst reforms to civil justice and competition, especially in services, can further be enhanced.

COVID struck as economic momentum had been slowing in 2019, following a modest expansion that began in 2015. Employment and investment levels had still not recovered from the successive shocks of the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis. Per capita incomes, having grown modestly until 2008, have remained below 2 000 levels for the last 11 years. The government’s priorities are to bring the health situation under control and create the conditions to raise Italy’s growth – by preserving productive capacity and livelihoods, and then creating the environment to facilitate faster growth.

Successive COVID waves necessitated extensive mobility restrictions

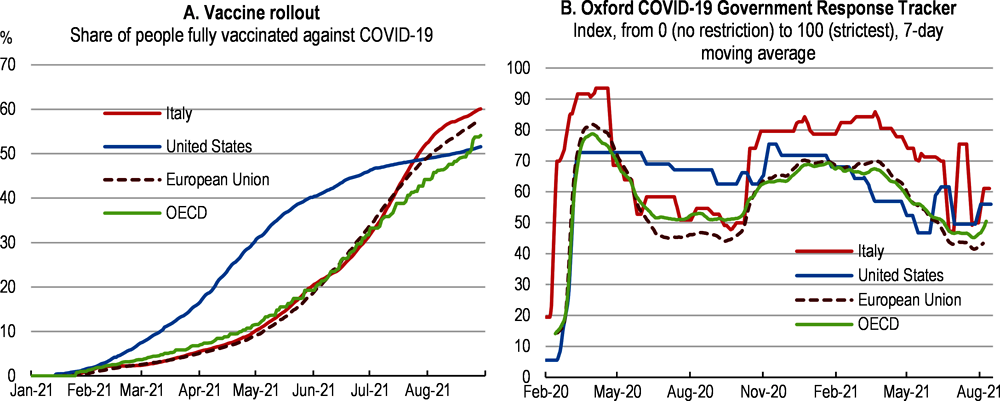

Italy was the first OECD country to impose a strict national lockdown in March 2020 in response to an early and sharp rise in fatalities. Subsequently, restrictions have primarily been applied regionally according to threat level. Vaccine rollout has improved alongside more secure supply and greater certainty about vaccine efficacy. The government plans to vaccinate 80% of the population by September 2021 (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, 2021[1]). Since the most vulnerable groups have been prioritised for vaccination, pressure on intensive care units should remain moderate. The government has updated its regionally based colour coded risk alert protocols, and has clear, published benchmarks for moving between risk levels, based on infection and hospitalisation rates. A green passport for those vaccinated, immune or tested against COVID has been introduced from 15 June 2021, in order to facilitate the safe re-opening of contact-intensive tourism and entertainment sectors. However, as for other countries, the potential spread of more infectious and deadly variants remains a risk.

The economic and social impact of the pandemic has been severe

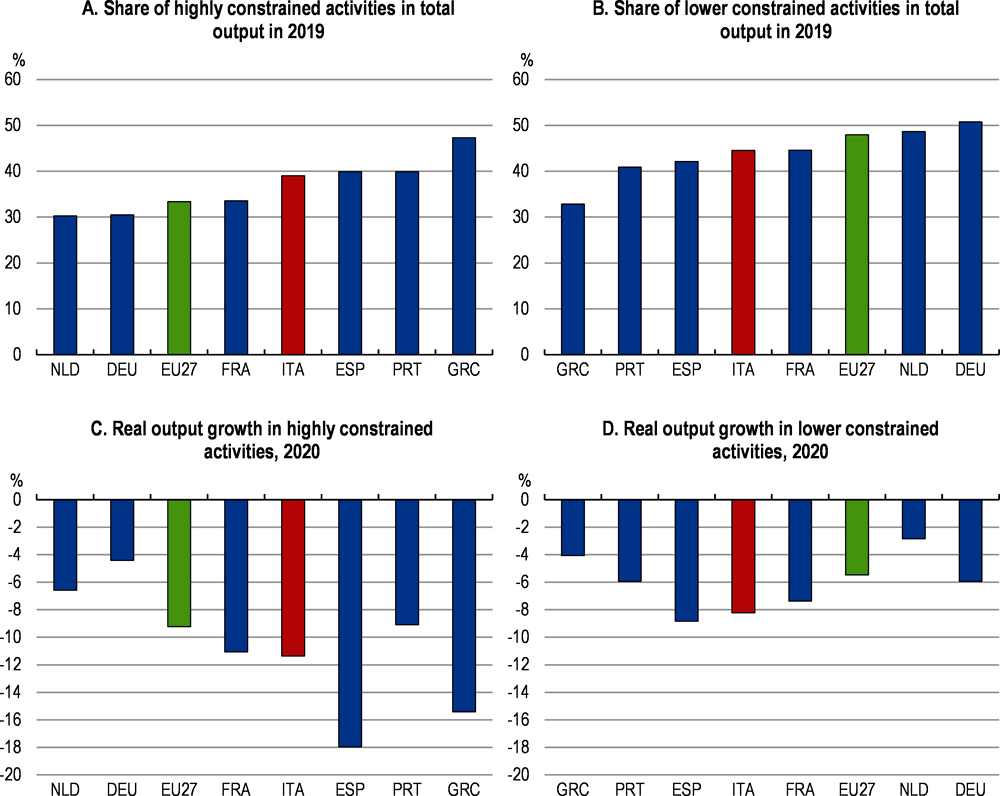

The intensity of the first and subsequent lockdowns (Figure 1.1) was reflected in an abrupt drop in GDP in April 2020, resulting in a GDP contraction of 8.9% in 2020, one of the steepest in the OECD. In part, this was the result of the composition of Italian GDP: contact-intensive services make up a relatively large proportion of the economy compared to other large European countries (Figure 1.2, Panel A and B). Tourism accounts directly for about 6% of GDP and indirectly 13% of GDP. Foreign tourism accounts for 42% of in-country activity, similar to most OECD members. Activity fell both in sectors that were severely constrained by COVID-related restrictions, as well as in those that were less so (Figure 1.2, Panel C and D).

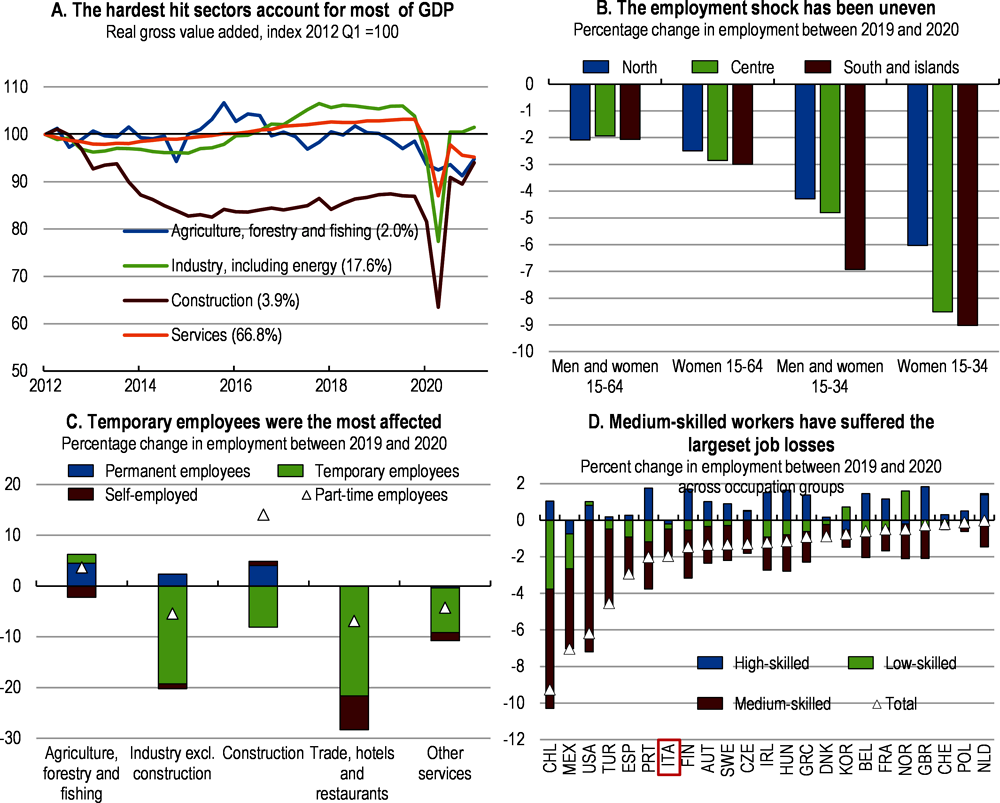

Manufacturing and construction activity has exceeded 2019 levels, as productive processes adapted relatively quickly to subsequent restrictions. The services sector by contrast, with a larger proportion of high-contact activities, has recovered less quickly (Figure 1.3.). Gross household savings rose sharply to 17.5% of GDP in 2020, due to precautionary motives and restrictions on activity limiting spending. Savings rates have fallen as restrictions on activity and consumption eased. The savings rate will, however, likely remain elevated for some time - the wealthiest 20% of households, which have a lower propensity to consume additional income, hold 60% of savings (Rondinelli and Zanichelli, 2021[2]). As savings rose and investment fell, the current account surplus increased to 3.7% of GDP in 2020. The net international investment position became positive in the second half of 2020.

The slowdown in activity prompted a decline in hours worked, which fell by almost 13% in 2020. The participation rate fell in 2020 from 2019, as COVID-19 restrictions limited job search. The ban on firing and access to short-time work schemes limited job losses in 2020 to 2.8%. The unemployment rate fell to 9.3%, from 10% in 2019 as COVID restrictions and the weak job market reduced the labour force by 3.4% in 2020. Job losses fell disproportionately on youth and women, and in particular on young women resident in the South (Figure 1.3). These individuals are over-represented in less secure forms of work: temporary contracts fell by 11.8% in 2020 and permanent positions fell by 0.4%. Whilst the firing ban covered all employees in 2020, temporary contracts that expired were allowed to lapse. The number of self-employed fell by 4.1%. Medium-skilled workers were most affected.

The policy response cushioned the crisis’ impact on firms and households – but the vulnerable remained heavily affected

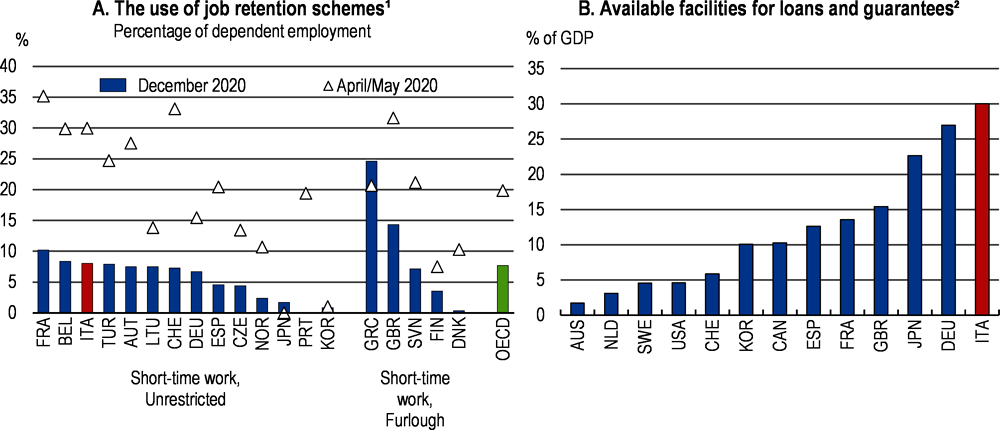

The initial policy response to COVID sought to limit hardship and maintain productive capacity by supporting cash flow and limiting bankruptcies and job losses (Box 1.1). The government provided wide-ranging direct budget support to households and firms. In order to preserve jobs, short-time work schemes were adapted to cover COVID-shutdowns and, in conjunction, a temporary ban on firing was put in place. Government guarantees, loan moratoria and macro-prudential regulations supported increased lending by banks, whilst monetary policy supported financial market liquidity.

The reach of these measures has been substantial. Over 7.2 million workers had benefitted from the wage supplementation scheme between March 2020 and February 2021 (INPS, 2021[3]). By November 2020, just under 2 in 5 firms with three of more employees requested liquidity and credit support (ISTAT, 2020[4]). State guarantees underwrote EUR 173.5 billion in new loans to small, medium and exporting firms (Banca d’Italia, 2021[5]). By mid-May 2021, debt moratoria covered EUR 144 billion in SME loans and EUR 23 billion in home loans.

Whilst poverty increased, public transfers limited the fall in households’ disposable income in 2020 to 2.6% in real terms. Italy’s social safety net, deepened in 2019 with the introduction of the Citizen’s Income scheme, increased the size of transfers to the poorest households. As a result, poverty in the poorest households did not increase (ISTAT, 2020[4]). Workers with temporary or seasonal contracts (particularly in tourism), as well as the self-employed, were assisted with cash grants, as many were not covered by short-time work schemes, nor Citizen’s Income. The relatively small size of these grants meant they likely had a proportionately larger cushioning impact on lower income households (Cantó Sánchez et al., 2021[6]). Access to social safety nets in the short term will need to take into account the nature of the employment recovery. Italy’s social safety nets are targeted to the poorest individuals and households, and many more may remain at risk if the recovery in employment is slow.

Schools were fully closed for 13 weeks, similar to the OECD average, whilst partial closures affected schools for 24 weeks, five weeks more than the OECD average (UNESCO, 2021[7]). Children from less advantaged homes will find it harder to regain this lost time with online teaching, since they tend to have less space and less access to technological equipment (European Commission, 2020[8]). The lockdown worsened conditions for those living with domestic abuse. Between March and October 2020, calls for help from victims of violence and reports of violent cases doubled. The sharpest increases in the use of helplines have been among those over 65 and under 17 (ISTAT, 2020[9]). Migrants are likely to have seen hardship increase as many are excluded from social safety nets such as the Citizens’ Income and are overrepresented in informal work.

The Italian government approved a wide range of measures to cushion firms, jobs and households from the COVID-19 shock and to kick-start the recovery. The government estimates these measures’ total value at EUR 108 billion in 2020 (6.6% of 2020 GDP) and EUR 72 billion in 2021 (4.1% of GDP). They were enacted through seven extensive decrees plus the 2021 budget. Major measures include:

Direct cash grants for firms: Firms received cash grants based on the size of their loss in turnover. Initial measures targeted firms in the most affected regions and sectors, but these were expanded as they did not account for the impact of restrictions on value chain activities. Sector-specific funds are also available for some of the hardest hit sectors, such as tourism.

Loan guarantees for firms: Over EUR 500 billion in loan guarantees was made available. The public guarantee schemes for small, medium and large firms were expanded, and a fee-free guarantee for new SMEs loans was introduced. SMEs in the most affected sectors received a moratorium to December 2021 on repaying loans.

Short-time work and measures to support employment: Italy’s existing short-time work scheme was enlarged, its coverage expanded to all sectors and firms, and the costs of accessing the funds was reduced.

Postponed tax and social contribution payments: Tax and social security contribution payments were deferred for all firms in the most affected sectors, and for all firms in all sectors with revenues below EUR 2 million. VAT payments were deferred for all firms and self-employed working in the most affected provinces.

Household income support: Several one-off payments have been made for those that did not benefit from short-time work schemes, including: cash payments to various categories of self-employed and seasonal workers; and supplementary monthly emergency income support of EUR 400 to EUR 800 for at-risk, low-income households. Childcare costs or costs to support carers obliged to take leave were funded. Unemployment benefits will not be affected by the duration of unemployment until 31 December 2021.

Supporting public authorities suffering revenue losses: Fiscal transfers have been made to subnational governments, public authorities and state-owned enterprises.

Support is evolving as the recovery takes hold

Most of the 2021 response package continues to support cash flow for a broad group of firms and households, targeting in particular those that have been most affected by the crisis. The risks from prematurely withdrawing support are asymmetric, given the size of the shock, its heavy toll on part-time and fixed term contracts, as well as women and the youth, and Italian firms with low cash levels. Guarantees and loan moratoria applications for SMEs and first-time buyers have been extended to the end of 2021. This balances the normalisation in bank lending standards and the gradual withdrawal of extraordinary access to short-time work schemes for all but the most heavily affected firms. As the recovery from the crisis continues, support will need to become increasingly targeted.

A number of measures are intended to offset the potential impact of the end to the ban on firing by large firms from 30 June 2021 and by smaller firms from 31 October 2021. Firms that do not reduce their workforce receive free access to short-time work schemes until the end of 2021. The solidarity contract allows firms that have experienced sharp losses in revenue to reduce wages by 70% if the workforce is maintained and the shift is agreed by unions. In addition, to support hiring in the short term, the government has introduced a new re-employment contract that waives social security contributions for six months for temporary contracts offered between July and October 2021, provided they are converted into permanent contracts at the end of the probation period. The expansion contract, which allows workers to retire early and thereby create space for new hires, can now be used by all firms with more than 100 employees. Fixed-term contracts can be renewed until the end of 2021 without limits on the number of extensions or providing reasons for the extension. Active labour market policies, necessary to support re-skilling of the workforce and the unemployed, are proving more difficult to implement. In the longer term, reducing non-wage labour costs should remain a priority rather than continuing rigidity in firing policies (see below).

Reducing the risk of debt overhang is critical to safeguard investment for firms that remain solvent after the crisis (Demmou et al., 2021[10]). Measures to support faster investment and deleveraging include expanding tax credits for equity investments in SMEs, start-ups and non-listed companies, as well as a temporary increase in the generosity of the allowance for corporate equity in 2021. The Patrimonio Rilancio fund set up under Cassa Depositi Prestiti is able to undertake equity-like investments, such as convertible bonds, particularly for medium and larger firms. Further policies to encourage the use of equity financing, such as the allowance on corporate equity, and measures to reduce bankruptcy costs are discussed below.

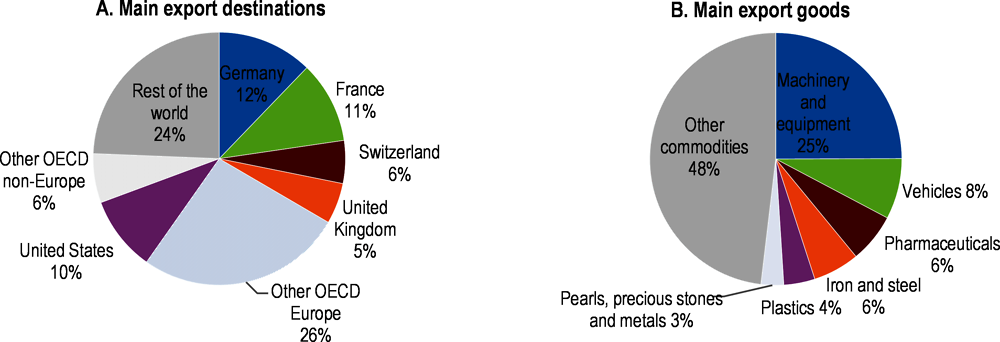

The United Kingdom is an important trading partner. It receives 5% of Italy’s merchandise exports (Figure 1.5). The full effects of Brexit will be clearer over time. Initial estimates of the impact of Brexit in Italy are relatively low compared to other EU countries (Arriola et al., 2020[11]). Trade data in 2020 and 2021 suggest the worst direct effects of Brexit on Italian goods exports were mitigated by avoiding a no-deal scenario. The value of the United Kingdom’s imports from Italy have fallen far less than imports from the EU, and are more in line with changes in the United Kingdom’s imports from the rest of the world. Italy’s supply chains have also not experienced severe disruptions, with just 2.2% of Italian imports coming from the United Kingdom in 2020. The knock-on impact of restricted movement of people and services restrictions is estimated to be relatively low in Italy (Arriola et al., 2020[11]).

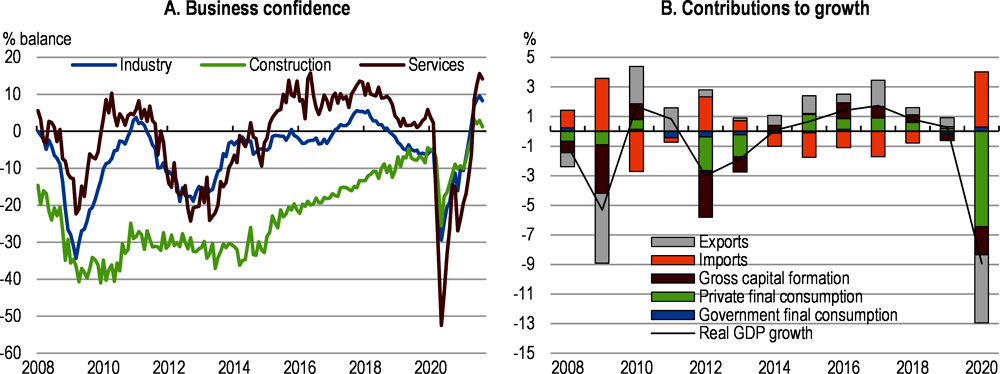

The economy is projected to recover steadily from the COVID shock, reaching 2019 levels in the first half of 2022. Higher public investment, including from Next Generation EU funds, will help to crowd in private investment in 2022. Consumption is expected to recover as jobs return and lower uncertainty encourages households to reduce precautionary saving. Recent data show a significant increase in business and consumer confidence, which is encouraging for activity and employment (Figure 1.6). Price pressures will rise in the near term due to higher commodity and construction prices, but will remain contained over the medium term. The manufacturing sector will benefit from the recovery in export demand in key markets, as well as positive spillovers from the construction sector. The services sector has recovered quickly in response to the government’s vaccination programme and green card system. Low entry barriers in tourism and entertainment sectors should allow a relatively rapid rebuilding of productive capacity.

Risks to the forecast are significant in both directions. The largest uncertainty lies in the evolution of the virus and the pace of vaccination in Italy and globally. Other downside risks include a reversal in the confidence recovery, higher or more rapid rates of bankruptcies and deeper-than-forecast scarring from the loss of business capacity or employment. This would likely worsen bank profitability and slow lending, although the systemic risk for the banking sector is lower than during the sovereign debt crisis. Upside risks include a sharper recovery in confidence, a more rapid drawdown of households’ accumulated savings, faster-than-expected investment spending via the Next Generation EU funds, and more rapid implementation of structural reforms.

Bankruptcy risks have increased but banks are better equipped to manage them

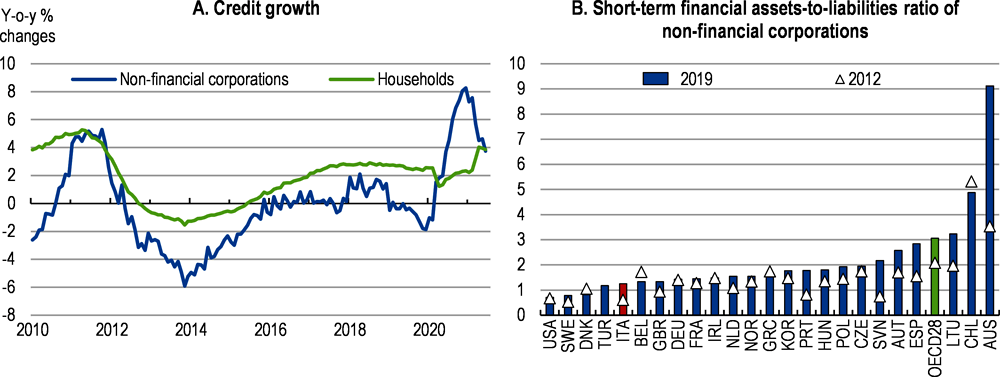

The government’s liquidity support, alongside counter-cyclical bank regulations, resulted in credit constraints for firms that were the same or lower in late 2020 compared to late 2019. The rise in credit growth was a critical lifeline for Italian firms whose cash levels are relatively low compared to OECD peers (Figure 1.7). Although higher credit growth raised firms’ leverage, many firms increased cash holdings and, on average, debt became longer-term, thanks to government guarantees (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]). A moratorium on bankruptcy filings between March and June 2020 and reduced court activity due to the pandemic further assisted. As a result, bankruptcies fell by 22.7% in Italy in 2020 compared to a 58.1% rise during the global financial crisis (OECD, 2021[13]).By preserving otherwise-viable firms, these policies minimise the risk of lasting damage to the economy’s productive capacity.

As support measures are gradually withdrawn, bankruptcies are likely to rise - although the average default rate is expected to remain below that of the global financial crisis (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]).The share of the highest-risk firms (with a probability of default above 5%) rose from 10% before the COVID crisis to 14% by the end of 2020 (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]). The performance of loans qualifying for moratoria suggests that the aggregate rise in borrower vulnerability is concentrated amongst borrowers linked to pandemic-hit sectors (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]).

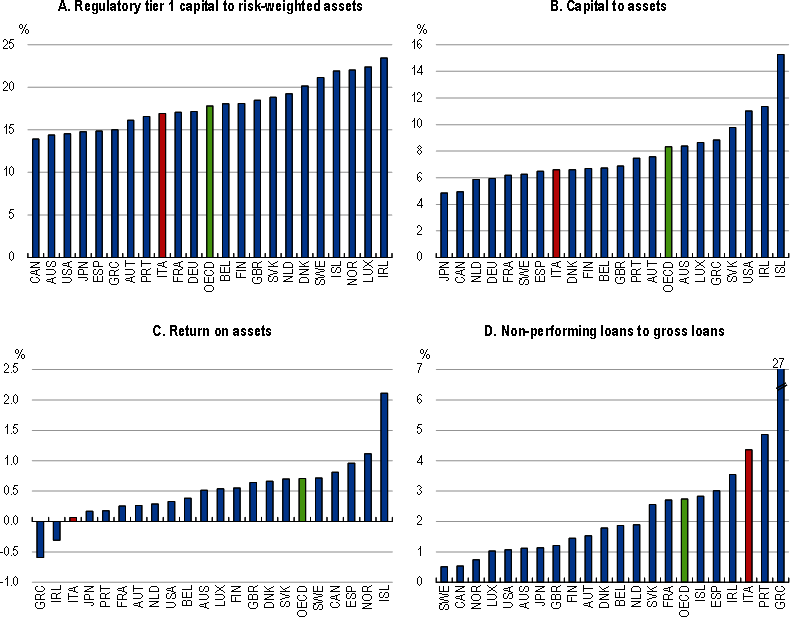

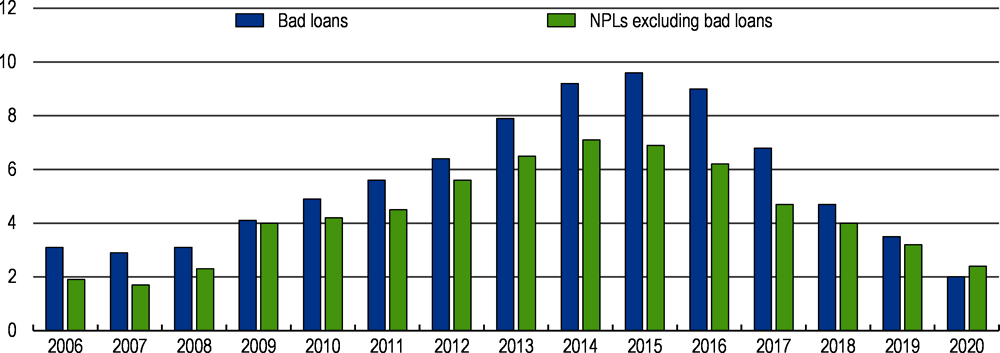

Higher bankruptcies will weigh on banks in the context of relatively low profits and still high non-performing loans compared to other OECD countries (Figure 1.8). Nonetheless, the banking system is on a firmer footing than at the time of the sovereign debt crisis in 2012 (Box 1.2). Banks have raised capital adequacy and improved the identification, valuation and sale of non-performing loans. Sensitivity to short-term funding pressures has remained low. Liquidity levels are double the regulatory minima thanks to higher retail deposits and the European Central Bank’s policies on bank holdings. Guidance to withhold the distribution of dividends has improved resilience in the short term. Furthermore, balance sheets are less sensitive to fluctuations in the market price of government bonds as the share of bonds valued at amortised costs has risen (European Commission, 2020[14]); (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]).

Continued efforts are required to monitor and actively manage the risks to bank balance sheets from the impact of the COVID-pandemic. In the last crisis, weak banks in Italy, as elsewhere, channelled loans to “zombie” firms, worsening the reallocation of credit (Acharya et al., 2019[15]). Current estimates suggest the number and credit needs of zombies are low (Schivardi and Romano, 2020[16]), reflecting improved bank risk management. However, the debt moratorium reduces the ability of banks to distinguish good and bad credit risks in real time (Bruno and Carletti, 2021[17]). To ensure that loans to non-viable firms are appropriately identified and removed from banks’ balance sheets, a combination of strong regulatory oversight (particularly for smaller banks) and the continuation of incentives, such as tax credits for disposal of non-performing loans and guarantees for securitised loan tranches, is required.

The non-performing loans market has grown dramatically in Italy, but there is further room for development. Correct pricing is critical to support both the entry of investors willing to buy non-performing exposures and the sale of these loans by banks. More efficient court procedures would raise recovery rates and reduce uncertainty and risk. Guidance from the regulator as to standards on identifying at-risk loans would help establish market-wide standards, particularly in the more difficult to value “unlikely-to-pay” segment. Common standards would reduce information asymmetries between banks and would-be purchasers of bank loans, and improve price-finding.

Obstacles to faster cost-reduction by banks should be removed to support longer-term profitability in the banking sector. Whilst there has been some progress in branch reductions, banks should be further encouraged to undertake cost savings. Foreign investment in the banking sector is very low, and allowing it to increase, for example with the sale of smaller, non-systemic banks, would avoid the risk of weakening domestic banks and may help to strengthen competitive pressures.

Following the sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s, bank capital buffers have been raised and governance improved. Reforms to mutual and cooperative credit banks have accelerated the consolidation of banks in the sector. The crisis management framework for non-financial firms has been strengthened with the introduction of the new business crisis and insolvency code, which are due to enter into force in September 2021.

The reforms were complemented with efforts to help banks manage their non-performing loans (NPLs) (Figure 1.9). Stricter supervision improved provisioning for NPLs. Provisioning was also supported by transitional arrangements to the IFRS9 accounting standard, which do not require capital ratio increases with these provisioning increases. The government supports the sale of NPLs by offering tax credits for banks to make the sales, and incentivising firms to buy the loans by guaranteeing senior securitised loan tranches (the GACS “Garanzia sulla cartolarizzazione delle sofferenze”). The GACS scheme has underwritten EUR 14.4 billion in senior loans as part of EUR 17.7 billion in total securitisations (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]).

In response to the COVID crisis, the government further incentivised banks to continue to sell NPLs in 2020 by offering generous tax credits. As a result, despite the fall in bankruptcies and low levels of activity, banks were able to sell around EUR 30 billion in 2020. The state-owned AMCO was a major purchaser of non-performing exposures in 2020 (Canino et al., 2020[18]). Market participants forecast a period of consolidation in the market for the purchasers of loans, as well as a shift towards increased use of securitised NPL products to attract more investors into the market. This will require improvements in how to value the unlikely-to-pay segment, a difficult category to assess in Italy as elsewhere – especially in loan exposures that are not securitised with real estate.

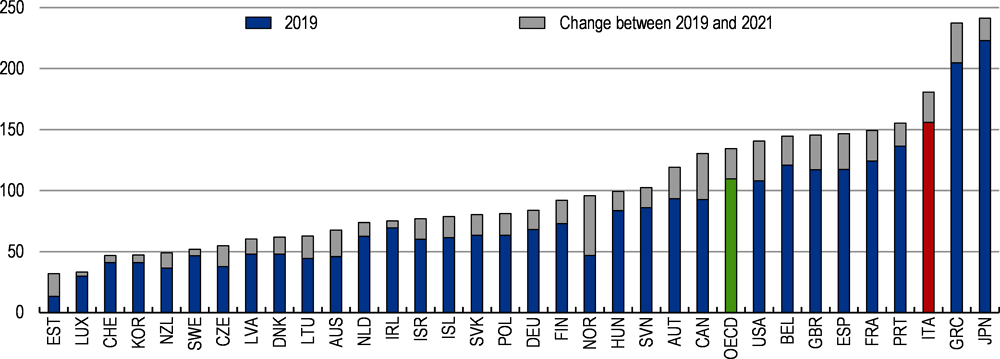

Risks to public finance sustainability

The government’s decision to strongly increase support given the prolonged fight against COVID-19 has resulted in a sharp increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio in the OECD, adding to already high debt levels (Figure 1.10). Before this, the primary budget surplus averaged 1.5% of GDP between 2012 and 2019. Even as COVID-related support spending is withdrawn, the government intends to increase investment spending between 2022 and 2024, delaying a reduction in the budget deficit to under 3% of GDP until 2025. A sustained increase in growth and continued low interest rates are required to achieve the government’s target of reducing the debt to GDP ratio to 2019 levels (134% of GDP under the Maastricht definition) by 2030.

The relatively high public debt-to-GDP ratio increases Italy’s sensitivity to interest rates changes. Interest payments are forecast to rise from EUR 57.3 billion in 2020 to EUR 61 billion in 2021 (3.7% of 2020 GDP), and gradually decline as a proportion of GDP as nominal growth increases (Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze, 2021[19]). Proactive debt management by the Treasury has lengthened the average residual life of issued debt to 6.9 years in March 2021 from 6.3 years in March 2014, helping reduce this pressure (Department of Treasury, 2021[20]). Going forward, the “snowball” effect (the difference between nominal growth and interest rates) is forecast to help reduce the debt to GDP ratio for the next 10 years (European Commission, 2021[21]). A rise in interest rates would, however, negatively affect Italy if not matched by a rise in the growth rate.

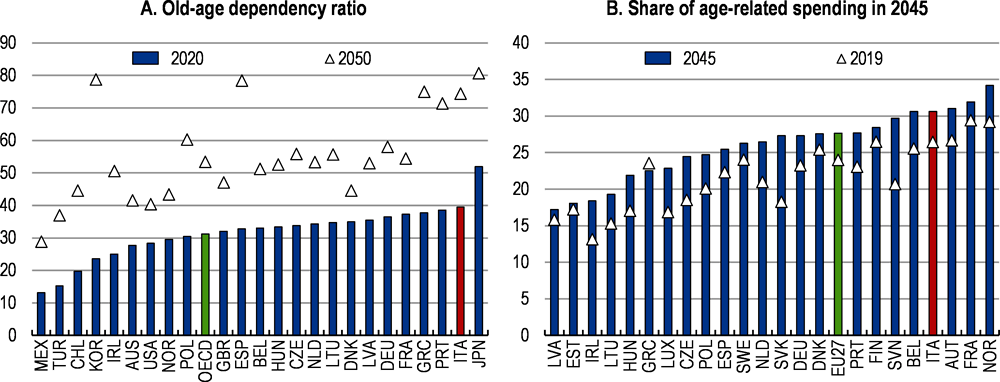

A series of comprehensive pension reforms since 2011, helped to contain the impact of ageing-related spending pressures (Ministero dell’economia e delle finanze, 2020[22]); (European Commission, 2021[21]). This is thanks in part to the rise in the retirement age which has beenlinked to life expectancy (OECD, 2019[23]).

Nonetheless, age-related spending will continue to rise over the next 25 years, due to health care and long-term care spending (European Commission, 2021[21]). With poor demographics, the old age dependency ratio will remain amongst the highest in the OECD (Figure 1.11). In the very long-term, as sustainable pension rules affect more of the workforce, pension spending will decline from 2045 to fall below 2019 levels by 2070 (European Commission, 2021[24]). In 2019, measures were introduced to delay the link between retirement age and life expectancy until 2026. The Quota 100 scheme, also introduced in 2019 and due to expire in December 2021, allows early retirement from age 62 with 38 years of contributions. If Quota 100 was permanently adopted, spending on pensions would lead to cumulatively higher spending of 11 percentage points of GDP between 2020 and 2045 (Ministero dell’economia e delle finanze, 2020[22]). It should be allowed to expire in December 2021. To further contain costs, permanent survivor pensions – which cost 2.4% of GDP compared to the OECD average of 1% – should not be available to those much younger than the standard the retirement age (OECD, 2019[23]).

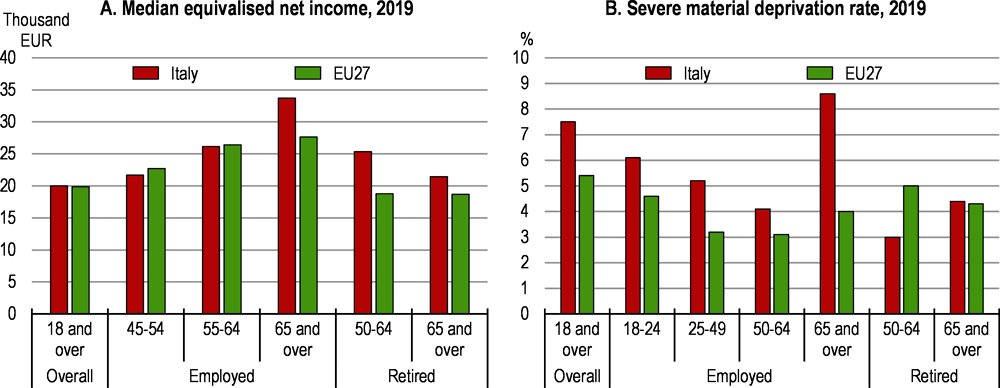

Currently, the typical Italian pensioner enjoys higher incomes and lower poverty rates than their European counterparts – in contrast with those in work (Figure 1.12). In the long term, in spite of the projected reduction in pension expenditures to GDP, Italian pensioners will enjoy relatively high replacements rates vis-à-vis other EU workers. The “Citizen’s Pension” introduced in 2019 substantially improved social protection for the aged (OECD, 2019[23]). However, some pensioners are at risk of poverty. The so-called “women’s option”, which allows early retirement on a notional defined contribution basis until December 2021, should not be renewed as it increases old-age poverty risks (OECD, 2019[23]).

Contingent liabilities increased to 13% of 2020 GDP, a rise of EUR 129.7 billion from 2019, as the government relied heavily on loan guarantees as a mechanism to improve liquidity during the COVID-19 crisis. The loans disbursed have been lower than the announced guarantee ceilings (Table 1.3). Contingent liabilities related to the COVID crisis stood at EUR 196.4 billion in July 2021 (7.1% of 2020 GDP). Any call on the guarantees will raise the overall public debt stock. Guarantees from the central guarantee fund cover loans issued for between 6 and 8 years. Loans issued by SACE tend to be asset backed and dominated by larger firms. Although debt moratoria cover a substantial EUR 193 billion in loans, the fiscal risks of this scheme are expected to be low, as the guarantee covers only 33% of payments due, after the banks have made a recovery effort. Approximately 22.9% of the stock of bank loans is high risk, with a greater-than 5% default probability (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]).

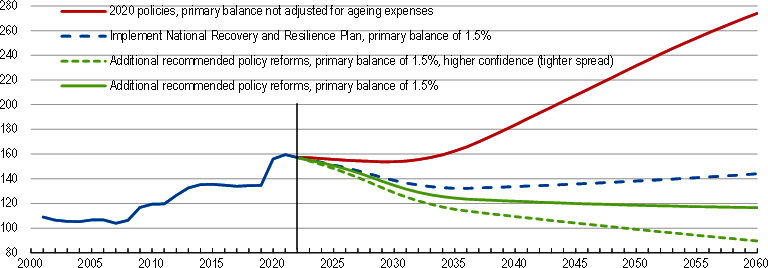

To place public debt ratios on a sustained downward path, Italy will need to grow faster and better allocate public resources and taxation. The reforms embodied in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan will help to raise growth if well implemented. However, even with a primary budget surplus of 1.5% of GDP, this will be insufficient to reduce the public debt-to-GDP ratio over the very long term (Figure 1.13). Signalling a clear, effective and sustainable fiscal framework will be put in place is a key condition to maintain investor confidence. Rebuilding fiscal space will help to absorb future shocks. Medium-term fiscal plans should be developed, even if implementation will be dependent on the pace of recovery. These fiscal plans should recognise the potential risks from higher interest rates or lower growth and set out strategies to address them.

Over the medium term, the fiscal framework must support faster growth whilst meeting the high and rising cost of ageing. Raising already high tax revenues or lowering levels of public investment in education and physical infrastructure would adversely affect economic growth. This will weigh on younger generations who are now more at risk of poverty than older generations. Reallocating public spending and adjusting the tax mix are thus key priorities. Spending plans should be informed by a succinct set of policy performance indicators and public spending reviews to ensure allocations reflect spending effectiveness in achieving priorities and meeting citizens’ needs. These measures are discussed in Chapter 2. Tax reforms should ensure a fair, efficient and progressive tax system. To boost growth, public finance management reform should be complemented with additional structural reforms as discussed below.

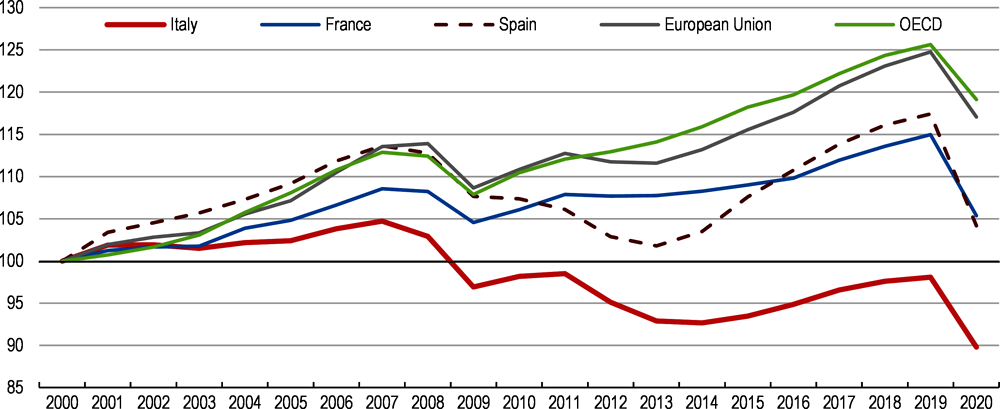

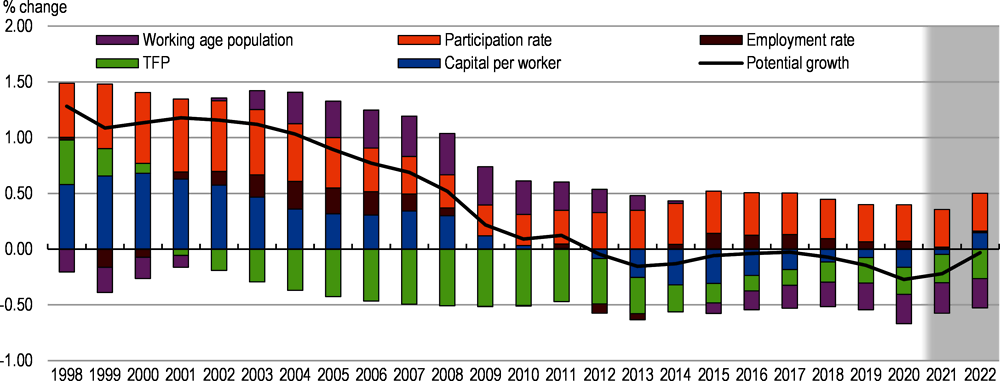

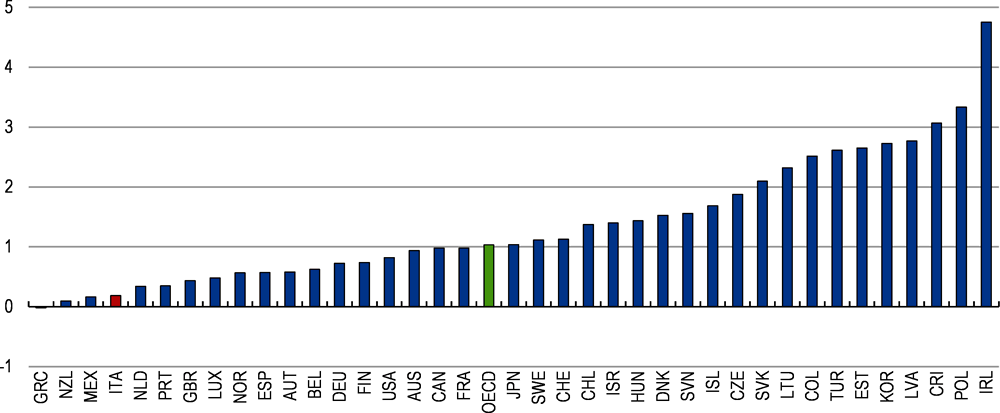

Italy’s per capita income is now below its level 20 years ago while most other OECD countries have seen an increase (Figure 1.14). Investment, productivity and job creation have all lagged behind peers. To overturn decades of low per capita income growth, Italy must implement structural reforms that will boost employment, investment and productivity (Figure 1.15).

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan prioritises investment and structural reforms

The government intends to support growth in the near-term through providing substantial support for households and firms to preserve productive capacity in 2021 and to a lesser extent in 2022. The transition to faster growth post-COVID is primarily cdriven by implementing structural reforms and increased public investment (Box 1.3). Public investment spending, focused on green and digital and technology investments, will remain above 3% of GDP from 2022, up from an average of 2.5% between 2010 and 2020.

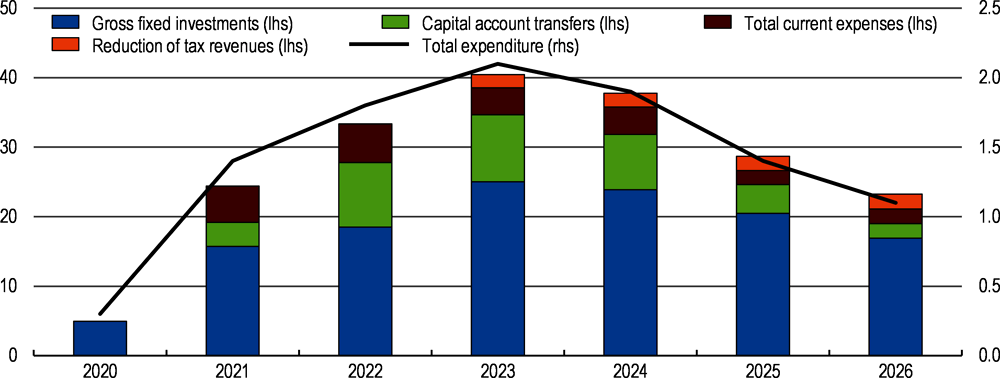

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan outlines structural reforms and spending plans of EUR 235 billion to raise Italy’s growth. Funding includes EUR 205 billion Next Generation EU funds. Italy intends to utilise the full EUR 68.9 billion in grants and EUR 122.6 billion in loans from the Recovery and Resilience Fund, as well as EUR 13.5 billion in REACT-EU funds. National resources of EUR 30 billion will be held in a complimentary investment fund.

Spending is spread along 6 core priority areas (Table 1.4). Greener energy, transport (in particular high-speed rail) and the efficiency of buildings are prioritised alongside broadening Italy’s use of technology including through faster broadband connectivity. New projects account for just over 70% of the total spend. Public investment and research and development make up over EUR 90 billion in new investments, combined with almost EUR 30 billion in new incentives to encourage investment in the private sector (Figure 1.16).

The Plan uses a number of successful existing incentive programmes to stimulate higher private investment. A number of projects can be deployed rapidly and are likely to raise growth in the near term - in particular, projects to support railways, private investment and R&D tailored to businesses make up a third of total spending. Plans for renewable energy, electric vehicle infrastructure and broadband could quickly crowd in higher private investment beyond the amount directly budgeted if there is clarity about the long-term vision for the market in the respective sectors.

Transversally, spending on the South accounts for about 40% of all investments with a specific geographic focus, although the proportion varies across the different thematic areas. In order to translate into a sustained improvement in regional growth and employment outcomes, it will be necessary for public administration effectiveness to rise. (Papagni et al., 2021[32]) find differing investment outcomes based on the quality of institutions. (Albanese, Blasio and Locatelli, 2021[33]) find that European Reconstruction and Development Fund investments tend to raise total factor productivity growth where institutions are better.

Total direct spending dedicated to women is estimated at EUR 7.5 billion, including the plan’s EUR 4.5 billion to expand early childhood care infrastructure and access, which is an obstacle to female labour force participation. Other efforts also seek to raise participation in science, technology, engineering and maths, women’s entrepreneurship and a gender equality certification system. Women will also benefit from a temporary hiring incentive for employers.

Source: (Servizio del Bilancio del Senato, 2021[34]) ; (L’Ufficio parlamentare di bilancio (UPB), 2021[35]); (Consiglio dei Ministri, 2021[31]).

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan places a central role for a series of structural reforms, which will be critical to secure long-term growth gains from higher spending. The key themes are to raise the effectiveness of the public administration and reduce regulatory burdens, improve the efficiency of civil justice and foster competition. Some of these reforms have begun (Box 1.4 and Box 2.1). Chances of successful implementation of structural reforms are greater than in the past as clear milestones and targets have been set and are linked to the disbursement of Next Generation EU grants and loans.

The identified areas are all in line with the priorities identified by the OECD (see below). Chapter 2 outlines the priorities for reforming the public administration to improve the implementation of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan. The potential impact of the Plan’s structural reforms and investment plans, assuming historic absorption rates, are modelled in Table 1.5, together with a series of already-legislated reforms. These include the introduction of a EUR 100 monthly tax credit for workers, the introduction of legislated bankruptcy reforms and temporary support for disadvantaged workers.

The results highlight that the substantial increases in spending alongside structural reforms envisaged by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan can have an important impact on growth. Permanent increases in public investment in physical capital and education and skills, when accompanied by improvements in spending quality, would complement and reinforce these gains.

This Survey’s recommended reforms are intended to deepen the substantial reform programme the government has outlined in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Higher absorption rates of investment funds are possible with reforms to public investment processes as described in Chapter 2. Over the longer term, raising the quality of and access to adult learning and early childhood education and care, as well as lowering non-wage labour costs, would ensure that the gains from growth are more evenly spread. Productivity growth can be increased through reducing regulatory burdens and improving competition – particularly in the services sector. (Table 1.5) presents estimates of the impact of a selection of reforms discussed in this Survey on growth and Table 1. the impact on the fiscal balance.

The structural reforms agenda addresses some of the most important obstacles to raising Italy’s long-term growth potential. A timetable of reforms has been agreed with the European Commission. Since many reforms will take time to implement, the disbursement of Next Generation EU funds is contingent on reaching a series of milestones. The structural reform agenda is ambitious and demanding. Improvements in the public administration’s effectiveness will facilitate rapid implementation. The monitoring and accountability mechanisms established will be crucial for successful implementation, alongside a clear, agreed program with the legislature.

The tables below present the growth and fiscal impacts of some key structural reforms proposed in this Survey. These estimates are illustrative. There are high levels of uncertainty in determining the growth impact of reforms. The timing and quality of investment spending will also affect estimates. The government has estimated that depending on the efficiency and quality of investment, the impact on growth can vary between 1.8 and 3.6 percentage points (Consiglio dei Ministri, 2021[31]). The Banca d’Italia estimates that the investments outlined in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan could raise GDP by almost 2.5% in 2024 (Banca d’Italia, 2021[36]), assuming that investments are spent promptly. If the investments are successful at crowding in private investment, the number could rise to 3.5% in 2026. The Banca d’Italia estimates an additional 3 to 6 percentage points of growth could be achieved with structural reforms over a ten-year time horizon. The European Commission estimates that the impact of the investments on growth by 2025 could vary between 1.4% and 2.3% depending on the productivity of the investments (European Commission, 2021[37]).

Supporting more effective public investment spending

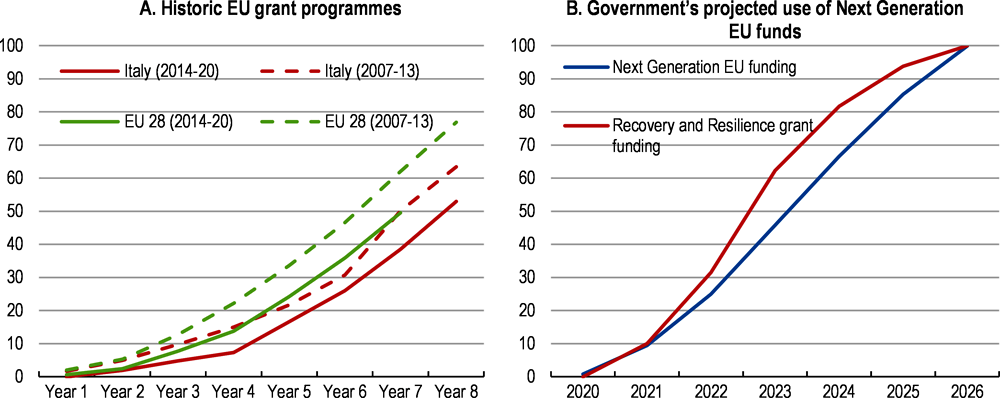

Italy plans to disburse the Recovery and Resilience funds more swiftly and effectively than it has disbursed its European investment budgets in the past (Figure 1.17). Stakeholders have highlighted governance, administrative capacity and procedures as core elements in slowing down past disbursement rates. (Crescenzi, Giua and Sonzogno, 2021[39]) find that past EU projects structured similarly to Next Generation EU funds are spent in a timely fashion if there is a strong role for the national government, wide consultation with local stakeholders (beyond regional and local authorities) and limited intermediate governance layers. Italy has undertaken a number of innovations to improve disbursement rates. Centralised monitoring of progress in implementing investments and structural reforms, and a separate team to monitor financial compliance, will improve accountability. Simplified procedures, tighter deadlines for government authorisations and deadlock breaking mechanisms in the event of non-performance have been legislated. This also includes intervening in local authorities’ powers in certain circumstances, such as delayed project implementation. Procurement processes have been adjusted, including consolidating all required authorisations and opinions into a single feasibility document, and restricting which bodies can issue tenders for investments linked to the National Plan. This could lead to improved project planning, prioritisation and implementation (Chapter 2).

Nonetheless, addressing the underlying constraints to public investments would reduce Italy’s need to turn to exceptional arrangements such as special commissioners to implement urgent or high-profile projects. Delays in starting projects could be reduced further by consolidating procurement into regional and central governments’ specialised procurement agencies (Chapter 2). These have deeper capacity, are better able to prepare and cost projects, have experience in assessing procurement against broad economic effectiveness and other policy criteria, and are better able to manage disputes with tenderers. Better coordinating and collaborating across the different government agencies involved in investment projects would smooth implementation and help navigate differences in capacity. If it were to be fully developed and resourced, Investitalia – the new agency that helps different government bodies prepare public investment projects, obtain approvals and implement projects – may be a model that merits expanding. Ensuring sufficient funding for ongoing maintenance would help avoid further cases of assets degrading to the point where they require costly emergency reconstruction. Other suggestions to strengthen the Plan include efforts to improve public administration efficiencies, digitisation and green energy, as discussed below.

Efforts to raise private investment must reach the services sector

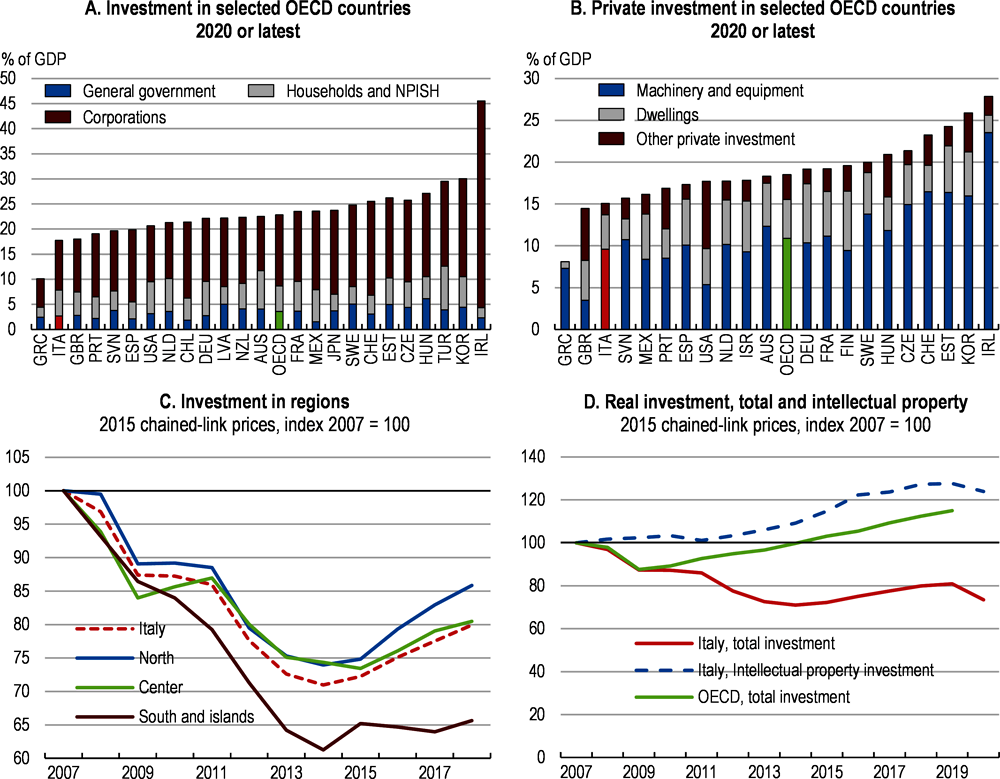

Business investment in Italy is much lower than in OECD peers (Figure 1.18). The global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis both lowered investment. The recovery has been slow due to weak demand, low profitability and firms’ difficulties in accessing finance; high taxes and burdensome regulations also played a role (Briguglio et al., 2019[41]). Services firms, which are more numerous in the South, account for 71% of total investment, but their recovery was much slower than manufacturers’ (Figure 1.19).

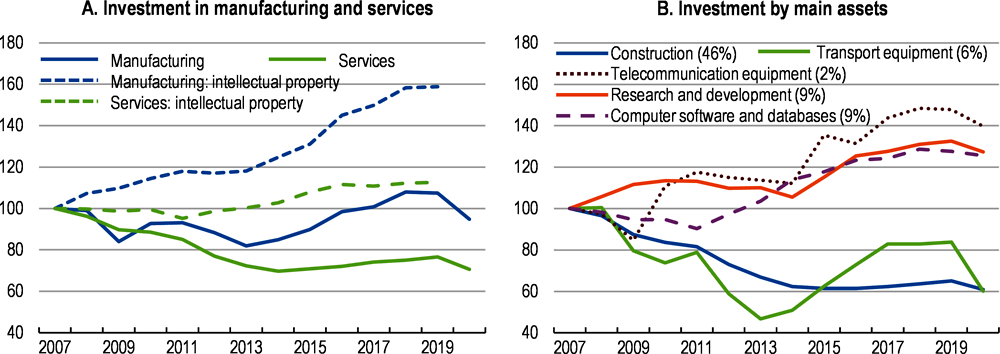

To promote business investment, the government instated a generous set of incentive schemes under the banner Impresa 4.0 and most recently Transizione 4.0, to offset the high regulatory burdens and levels of uncertainty faced by firms. Investment in assets favoured by the incentives, such as R&D and computer software, have grown very quickly (Figure 1.19). The incentives have worked particularly well in supporting investment in manufacturing firms (Ciapanna, Mocetti and Notarpietro, 2020[42]); (Briguglio et al., 2019[41]); (Bratta, Romano and Acciari, 2020[43]); (ISTAT, 2018[44]).

The incentives do not reach all firms, and take-up by the service sector, where productivity and investment lag, has been low. The already large productivity gaps between firms that invest and those that do not risk widening further following the pandemic (OECD, 2021[45]). The impact of competence centres, established to assist firms to train, plan and execute investments, must be assessed. A dedicated focus on services sectors may be required. In an effort to better target SMEs, the government has limited access to the incentives to smaller firms by limiting claims as well as the size of potential investments. The impact of this shift should be monitored, as it could have unintended consequences – excluding larger investments may lower the aggregate investment rate (Zangari, 2020[46]). In addition, it may create incentives to stay small for firms that take up the incentive.

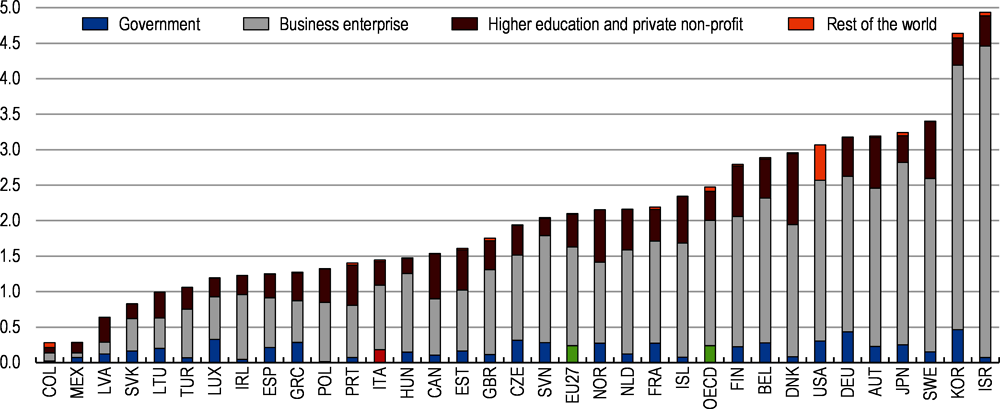

Italy’s total research and development spending (1.4% GDP) lags peers, particularly in government and higher education institutions (Figure 1.20). Increasing budget allocations to basic research, channelled through universities, would raise long-term innovation. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan importantly raises support for research and development, with EUR 9.4 billion spending on new initiatives, including direct public grants for R&D, technology transfer and innovation, and green innovation. Existing innovation hubs, which increase the links between business and universities, could amplify the impact of this spending.

Progress in improving the business climate remains slow. Key issues include: the number of permits required to undertake an investment; the lack of clarity about the different regulatory processes in different regions; and overlapping mandates and approval processes from different regional entities. The government plans to collate all regulatory requirements for EU funded investments into one place. A better business environment would reduce the need to rely on financial incentives to support investment.

Improving access to equity financing could boost business investment

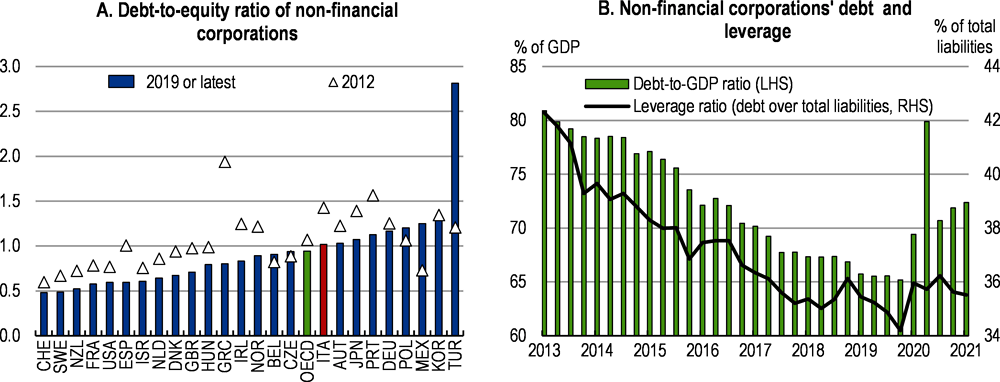

Italy’s firms tend to rely heavily on bank loans rather than equity as a source of finance. A strong negative relationship between leverage and investment exists in Italy as elsewhere (Briguglio et al., 2019[41]). The bias for debt over equity financing is likely to impede innovative, fast-growing firms, because these firms may invest more heavily in intangible property which makes them more reliant on equity financing (Andrews, Adalet McGowan and Millot, 2017[47]). The government has taken a number of steps to encourage the development of non-bank channels of finance, both equity and debt (Box 1.6). Leverage has fallen since the sovereign debt crisis (Figure 1.21) due to lower levels of debt - the debt bias remains (OECD, 2020[48]).

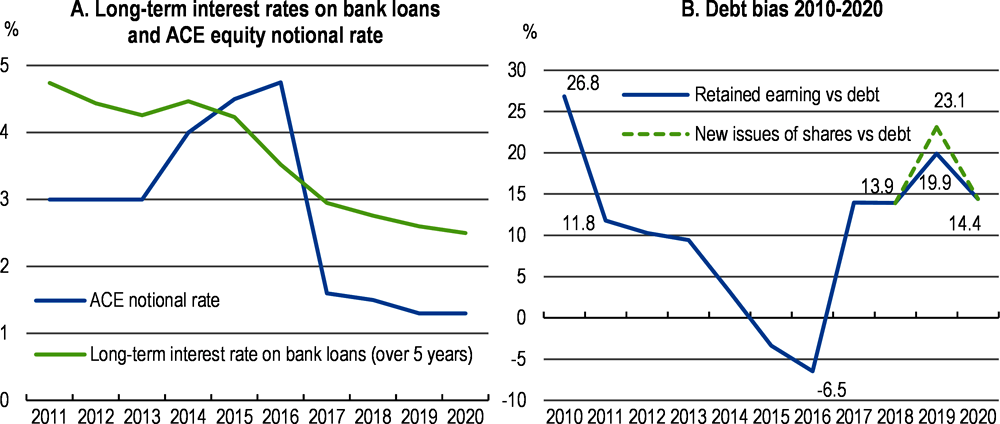

Removing or reducing tax-related incentives for debt financing could foster increased productivity diffusion. Italy’s tax allowance for corporate equity (ACE) was considered by many to be international best practice in supporting firms’ use of equity (Box 1.7). The current regime is much less generous than previously, which has helped to contain its fiscal cost but also probably reduced its impact. In 2021, the government temporarily increased the scheme’s generosity to accelerate de-leveraging following the COVID-19 crisis, particularly among smaller firms. Stabilising the ACE regime would improve investors’ certainty in the costs of different sources of finance, which may improve the scheme’s support for deleveraging and investment. To better target The ACE and reduce its fiscal costs, a notional rate for firms that face higher barriers to accessing equity finance (e.g. smaller firms) could be raised (Zangari, 2020[46]).

Italy has introduced several incentives to promote the use of market-based financing, with a particular emphasis on improving access for SMEs. These include:

Supporting equity listings, including for SMEs. Less onerous equity market listing requirements were encouraged through the Alternative Investment Market (AIM Italia), initially established in 2009. The bourse has now more listings than the main bourse. Elite was introduced as a platform to facilitate private fundraising placement. From 2018, firms are incentivised to list on a stock exchange with a tax credit equal to 50% of their advisory costs.

Increasing access to corporate bond financing. The mini-bond market framework established in 2012 provides a simplified process where unlisted companies (other than micro enterprises and banks) can issue bonds with less stringent disclosure requirements, within certain issuance limits. These bonds can only be bought by qualified investors. They can also be securitised, potentially increasing their appeal to institutional investors.

Incentivising investments in venture capital funds and in SMEs. Government-supported venture capital funds include Italia Venture I, II and III to incentivise investment in SMEs, the South and larger corporates respectively. The piani individuali di risparmio (PIR) introduced in 2017 exempts investors in SMEs from capital gains and inheritance taxes if funds remain in the PIR for at least 5 years. 2019 amendments, which raised risks and lowered liquidity, were subsequently over-taken by reforms to broaden the scope of investments (including bond issuances) and doubled the maximum annual investment to EUR 300 000. A five year tax credit for losses is available for investments undertaken in 2021.

Source: (OECD, 2020[48])

An Allowance for Corporate Equity reduces the tax bias favouring debt over equity by introducing tax deductions based on a company’s equity, at a policy-determined notional interest rate. By reducing leverage, it can potentially increase investment. The instrument complements efforts to raise the availability of equity capital and may help overcome a potential aversion from firm owners to using equity in light of the potential loss of control.

Italy introduced an allowance for corporate equity in 2011 (“Aiuto alla Crescita Economica” - ACE). The deduction only applied to new equity accumulated from 2011, which limited initial costs. The regime underwent a number of iterations: its generosity was increased substantially with the notional rate peaking at 4.75% in 2016. The cost of the scheme rose as generosity increased and the cumulative amount of equity subject to the ACE grew. In 2017, the notional rate was reduced to 1.6% and its application was limited to certain investments. The ACE was then repealed in 2019, to be replaced with deductions on regional tax rates. It was reintroduced in 2020 given the difficulties in implementing the replacement regime. The notional rate currently stands at 1.3%.

Studies of the efficacy of the ACE in Italy show that it helped correct the debt bias. (Branzoli and Caiumi, 2020[49]) estimate that it reduced the leverage ratio by around 9 percentage points in solvent manufacturing firms with a leverage ratio of around 50%, with effects largest for smaller and older firms. Since then, a steady reduction in the notional rate has likely reduced its impact on corporate leverage. (Zangari, 2020[46]) estimates the reduced generosity increased the cost of capital by 1.4 percentage points between 2016 and 2018, and by even more for firms facing structurally higher financing costs. Nonetheless, it still helps to correct the debt bias (Figure 1.22). Substantial policy uncertainty on the structure and rate of ACE may reduce its future impact on investment.

The green transition requires credible, long term commitments to carbon pricing

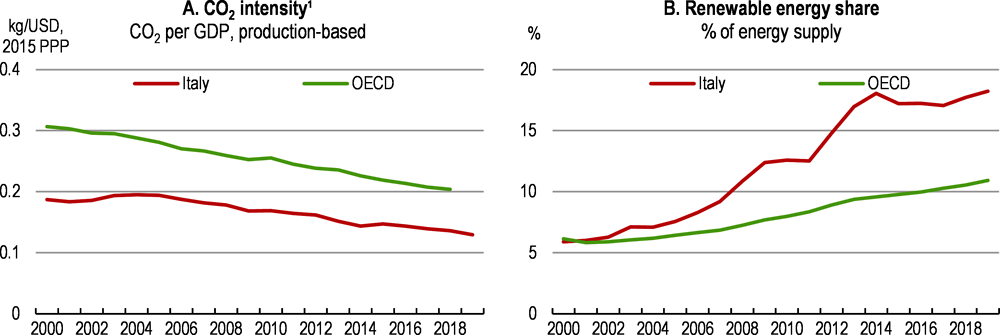

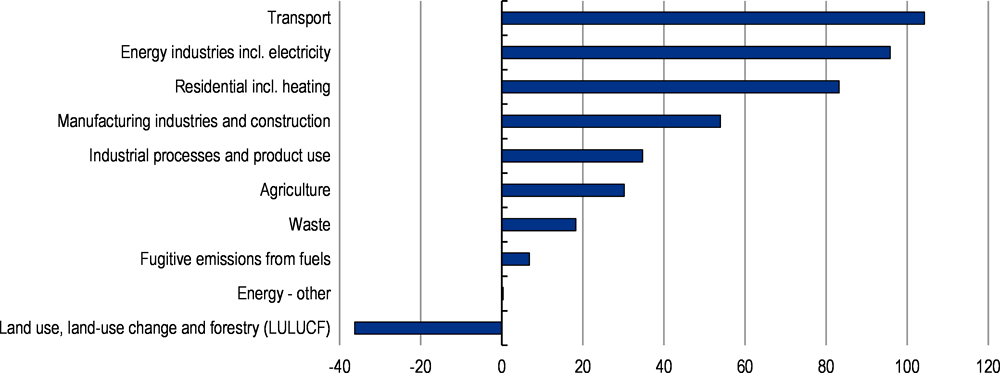

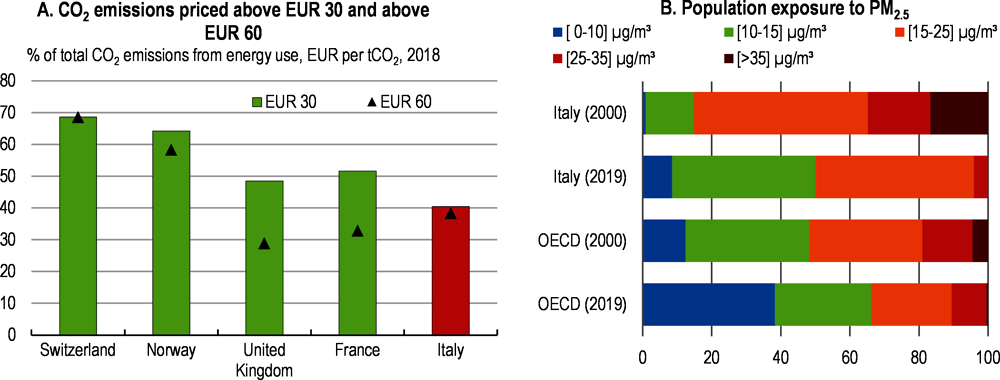

Italy performs relatively well compared with other EU and OECD countries in its progress towards reducing carbon emissions, its high share of renewables in energy (Figure 1.23) and high recycling rates (European Environment Agency, 2019[50]). In March 2021, the country issued its first Green Bond for EUR 8.5 billion, becoming the fifth largest issuer in Europe (Banca d’Italia, 2021[12]). Electricity, heating and transport remain the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions (Figure 1.24). Oil and coal reliance have been steadily substituted for biodiesel and natural gas, reducing overall emissions. Nonetheless, oil and coal constitute almost 40% of total energy supply. The country has one of the highest shares of passenger vehicles per inhabitant in Europe (European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association, 2021[51]) but just over 0.1% of the stock is in electric vehicles (Anfia, 2020[52]). Over 60% of the country’s building stock is over 45 years old, and highly energy inefficient.

Although Italy’s carbon tax rates are higher than many peers (Figure 1.25), it lags the best performers. In addition, carbon pricing is uneven: industrial consumers pay less than households; and diesel is taxed less than petrol, despite its higher health costs (Figure 1.25) (OECD, 2019[53]); (G20 peer review teams, 2019[54]). For example, the effective carbon price for petrol in road transport exceed EUR 300 per tonne of CO2, whilst the effective carbon price on natural gas for commercial users is below EUR 8 per tonne of CO2. This means commercial users face few incentives to reduce emissions and are likely to forego abatement opportunities, even if their abatement costs are considerably less than the EUR 300 per tonne of CO2 price of carbon in road transport Current energy use, as well as geographic factors, result in elevated exposure to particulates (Figure 1.25), especially in the North.

The government has responded to the EU’s new target to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030 by targeting the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions in its National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Raising renewable energy capacity, including wind, green hydrogen and biomass, as well as recently legislated reforms to reduce regulatory obstacles to faster renewable investment. The Ministry has announced the country will install an additional 65-70 GW of renewable energy over the next decade, raising the targets set out in the 2019 Integrated National Plan for Energy and Climate. Electricity storage capacity and interconnections are also forecast to rise to support increased renewable energy generation.

Tackling transport emissions. High-speed rail investments are substantial, at almost EUR 24 billion. Electric vehicle subsidies are augmented by introducing EUR 0.74 billion support for charging stations infrastructure. This more holistic approach would benefit from encouraging closer, city-based collaboration on regulation, as done in Norway and Austria, as well as with energy providers, such as in Stockholm, Sweden, to reduce the costs of providing charging infrastructure and meet the capacity of local grids (Hall and Lutsey, 2020[55]). The impact on behaviour could be strengthened if, at the local level, investment plans for electric vehicles, high-speed rail and incentives to support alternative transport are coordinated. Toll pricing strategies should also be considered. Together, these could help mitigate the impact of air pollution in some of the most crowded cities.

Improving building energy efficiency. Incentives of EUR 18.5 billion have been introduced, including EUR 4.6 billion in spending by the Complimentary Fund. This is accompanied by legislated reforms to make building renovation approvals faster and simpler than in the past. These could be more explicitly linked with efforts to reduce reliance on domestic diesel heating systems, which are responsible for up to 40% of PM10 emissions in the most affected regions. This would help address the very high levels of particulate emissions Italians are exposed to, and which drives the elevated levels of premature deaths due to air pollution (G20, 2019).

Supporting the circular economy. Italy has one of the highest recycling rates in Europe, supported by effective regulations such as the four stream waste collection system, the ban on micro plastics and the financial levy paid by plastic packagers (Ghisellini and Ulgiati, 2020[56]); (WWF, 2019[57]). There are, however, stark divergences between top and poor performing municipalities across Italy, as illustrated by the large gap in separate collection rates between Veneto (73.7%) and Sicily (21.7%) in 2017 (Cialani and Mortazavi, 2020[58]). The National Recovery and Resilience Plan allocates EUR 5.3 billion to support the circular economy, of which EUR 2.1 billion is focused on supporting improved waste management, with a particular focus on infrastructure. This is in line with past Survey recommendations. A focus on infrastructure could help municipalities take advantage of the increasing returns to scale in waste management (Cialani and Mortazavi, 2020[58]).

At a national level, a clear, time-bound carbon price target would signal the need for behaviour change whilst providing time for households and firms to adapt. Germany has provided a carbon price path from EUR 25 per tonne to EUR 55-65 per tonne between 2021 and 2026 for those sectors not covered by the European Union’s Emission Trading System (EU ETS). The Netherlands has imposed a floor price for the EU ETS price that rises steadily from EUR 30 per tonne to EUR 125-150 per tonne between 2021 to 2030 (OECD, 2020[59]). Setting regulations, standards and norms and clearly communicating them will raise certainty and reinforce behaviour change.

To be credible over the long-term, the transition to a higher carbon price must explicitly manage the associated distributional and competitiveness costs. This could help reduce the very high levels of uncertainty that inhibit climate-mitigating investment (Figure 1.26). A higher carbon tax would likely reduce demand for carbon and raise revenue, but also affect the poorest households most (Faiella and Lavecchia, 2021[60]). These households would need to be compensated.

Sweden explicitly announced in advance that subsidies and taxes would be gradually adjusted over time to reflect a higher carbon price, but coupled this with explicit transfers to benefit lower income households in particular. The green tax increases of 2001 to 2006 were matched with cuts in income taxes focused on low-income households, and the increases of 2007 to 2013 were matched with sharp reductions in labour taxes (Ministry of Finance, 2018[61]).

In Switzerland, to compensate for the introduction of a carbon tax on heating fuels, two thirds of the revenue from the tax were earmarked to reduced labour taxes, and one third to energy efficiency and retrofitting investments (Office fédéral de l’environnement (Suisse), 2020[62]).

A revenue neutral switch to carbon taxes in the medium term could be considered. Firms currently receiving fuel subsidies could continue to receive the same amount of support – but decoupled from their use of carbon-intensive technologies. The subsidies could then be gradually phased out over time. The newly formed Ministry for Ecological Transition, which is similar to ministries in place in France, Spain and Switzerland, could coordinate such a strategy.

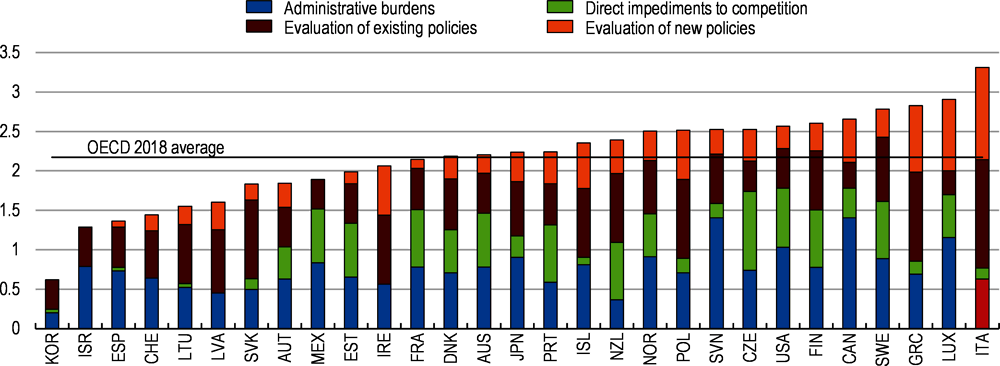

Sustained behaviour change also requires supportive regulations, standards and norms. Technology and performance standards or bans on certain products are necessary to complement carbon pricing. It is critical, however, that these regulations are designed without increasing the overall regulatory burden facing firms (Berestycki and Dechezleprêtre, 2020[63]). Italy’s current environmental regulations impose relatively high burdens (Figure 1.27). Recent reforms as outlined above are a step in the right direction to streamline and improve environmental regulations.

Boosting productivity requires addressing regulatory obstacles and more concerted digital skill development

Weak productivity is concentrated in the services sector and seems linked to excessive regulation

Italy’s weak aggregate productivity performance (Figure 1.28) compounds the growth-inhibiting effects of an ageing society and low employment rates. Productivity is the main driver of growth and well-being over the long run, allowing resources to be combined in new ways, rather than relying simply on increased accumulation of capital and labour which are subject to decreasing returns to scale (OECD, 2015[64]). Large differences in income per capita observed across countries reflect in large part differences in labour productivity. Lagging productivity translates into relatively low wages and higher inequality when productivity dispersion is high (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[65]).

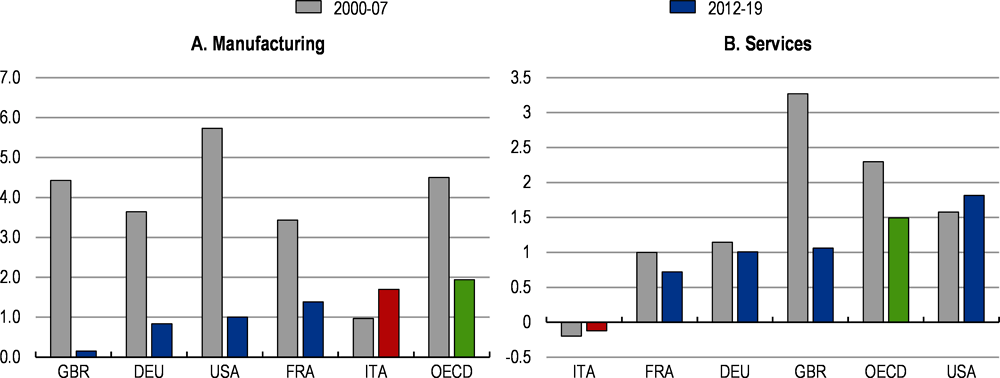

Weak aggregate performance masks significant divergences between industries, firms and regions. Productivity gains in manufacturing since the early 2010s have outstripped many peers in Europe (Figure 1.29). The exit of lower productivity growth firms, the entry and growth of more productive firms as well as increases in R&D have underpinned the improvement (Bugamelli et al., 2018[66]). Most of the productivity gains were driven by improvements in manufacturing firms with average productivity, rather than the top performers (Lotti and Sette, 2019[67]). In contrast, service sector productivity growth has remained negative since the sovereign debt crisis (Figure 1.29), weighing on aggregate productivity growth (Giordano, Toniolo and Zollino, 2017[68]); (Bugamelli et al., 2018[66]). In the services sector, productivity growth has slowed in both the top performers as well as in the least productive firms.

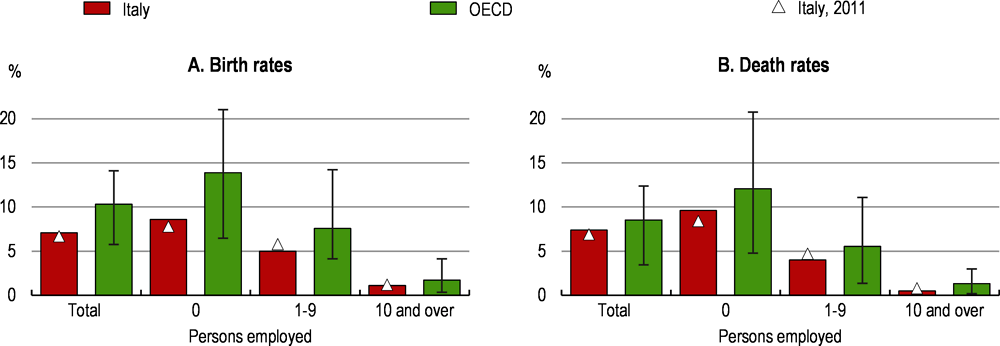

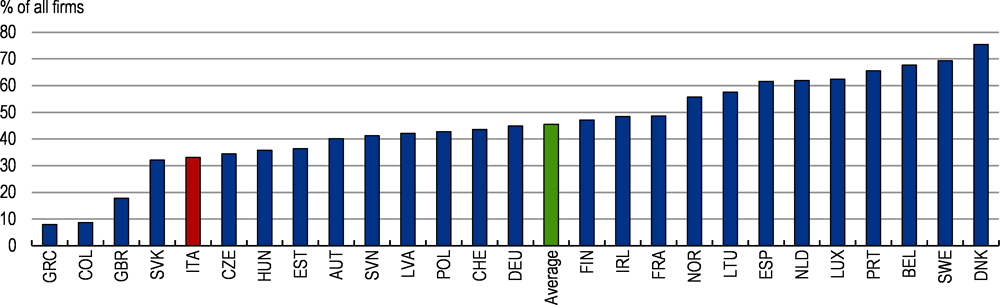

Dynamism in the Italian corporate sector is low. There are fewer firms created in Italy than the OECD average (Figure 1.30). Once created, firms survive for longer than the OECD average – but they also tend to stay small and grow very slowly (OECD, 2020[69]); the share of high-growth firms in Italy remains low (OECD, 2020[48]). The tendency for firms to stay small in Italy is interrelated with the ability to raise managerial skills, adopt new technology and invest in human capital (Visco, 2020[70]). Low rates of exit limit the pace of capital reallocation across firms, lowering overall productivity. These low exit rates and potentially high sunk costs in the event of closure can in turn impact on the rate of entry of new firms, as well as their subsequent growth rates (OECD, 2020[69]).

Dynamism is negatively affected by excessive regulations, which reduce competition, efficiency and workers’ mobility between firms (Bambalaite, Nicoletti and von Rueden, 2020[71]). They increase the productivity gap between leading and lagging firms (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[65]) as well as mark-ups (Thum-Thysen and Canton, 2017[72]). Lower entry barriers and more effective exit processes can boost productivity by allowing a reallocation of resources to the most promising firms and sectors (OECD, 2019[73]). Numerous efforts to simplify new regulations have been undertaken, although the reforms have not always prioritised the highest impact areas, nor simplified the existing stock of regulations or how they are implemented, as discussed in Chapter 2. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan’s near-term competition focus is on key network industries, which should support faster investment. Competition in services sectors also requires attention.

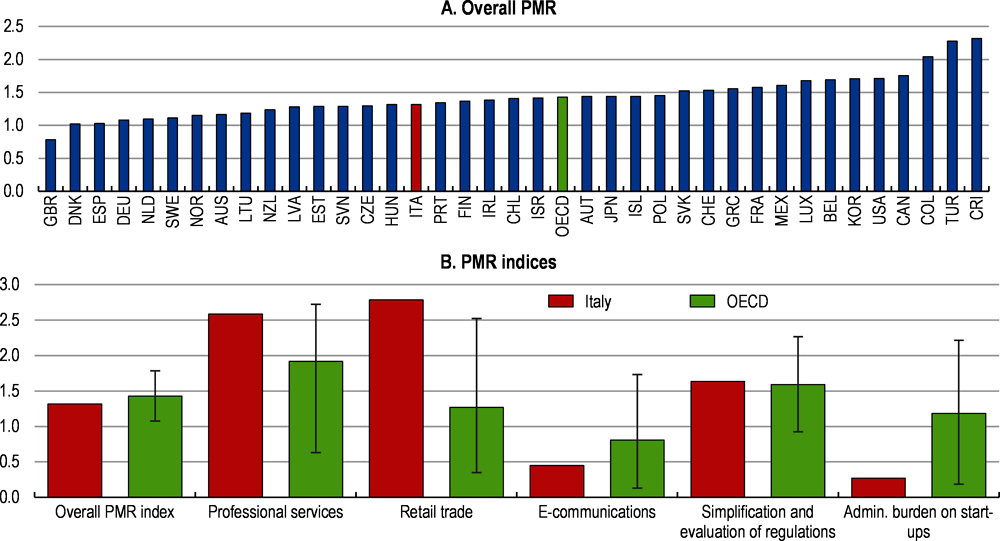

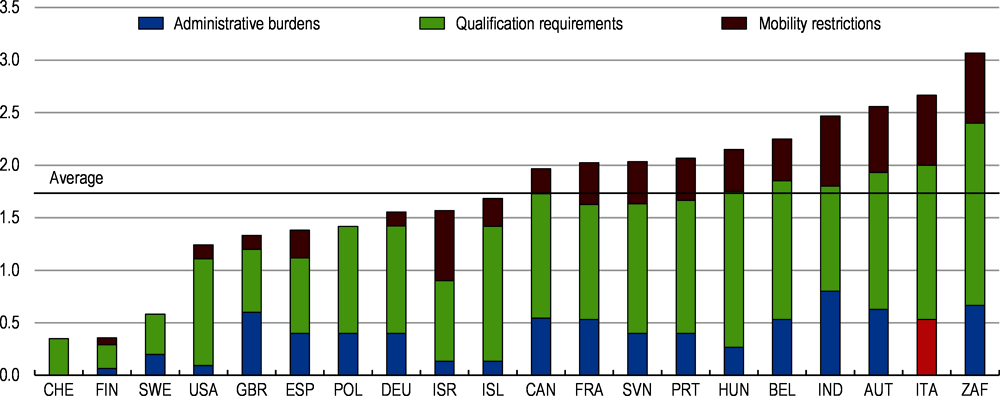

Italy scores relatively well on the OECD’s product market regulations index, and has made significant improvements to the regime for start-ups (Figure 1.31). However, regulations are high for retail, limiting sales promotions as well as store openings. Entry restrictions for professional services are very high (Figure 1.32) and associated with both quantitative restrictions, as well as regulated fees. The impetus for dynamism and competition from online services such as Airbnb or Uber is often limited by regulations – for example, forcing drivers to return to a specific point or for homeowners to comply with complicated procedures. Entry into Italian services subsectors is between 30% and 50% lower than the international benchmark (OECD, 2020[69]). The entry rate in regulated professions is lower than in other occupations and wages about 9% higher (Mocetti, Rizzica and Roma, 2019[74]). This has a depressing impact on productivity: (Ciapanna, Mocetti and Notarpietro, 2020[42]) estimate service sector liberalisation in Italy could induce a permanent increase in the service sector TFP of 4.3% and a permanent reduction in the services sector mark-ups of 0.7 percentage points. (Bambalaite, Nicoletti and von Rueden, 2020[71]) estimate an almost 0.3 percentage point increase in the efficiency of labour allocation if Italy moved its occupational entry regulations to the stringency of Sweden.

Authorities could support better information flow and sanctions regarding the quality standards for goods and services, rather than reserving activities or setting standards for the professionals providing them. This could include replacing licensing systems with less distortionary certification schemes and leverage digital platforms (Bambalaite, Nicoletti and von Rueden, 2020[71]).

A productivity board (see Box 1.8) could be particularly helpful in identifying and communicating the benefits of regulatory, competition and other policy reforms that can best support productivity and other policy goals. In Italy, the board could inform the design and implementation of reforms and assess the benefits for productivity of the reforms included in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan. It may also help ensure more consistent implementation of the annual law for competition. Provided for in 2009 legislation, the intention was to annually remove obstacles or develop competition based on advice from the Competition Authority, but implementation was limited. The 2015 draft was watered down and passed in 2017 (European Commission, 2017[75]). In 2021, the Competition Authority’s annual submission focused on network industries and investment, many of which were included in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Digitisation needs to be supported to boost productivity

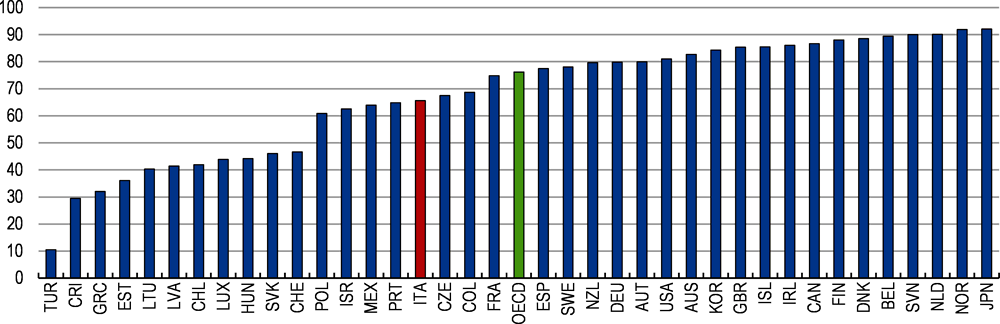

Digital literacy and the take-up of digital services is low relative to the rest of the OECD. Only 44% of people aged 16-74 years possess basic digital skills vs 57% in the EU. Supporting quicker rollout of fast broadband, which is currently very low (Figure 1.33), could accelerate digitisation (Andrews, Nicoletti and Timiliotis, 2018[76]); (Gal et al., 2019[77]). The National Recovery and Resilience Plan allocates EUR 6.7 billion to broadband infrastructure. The new broadband strategy aims to give access to 1 gigabit per second connections across the whole country by 2026, ahead of the European targets for 2030 (Ministro per l’Innovazione Tecnologica e la Transizione Digitale and Ministero delle Sviluppo Economico, 2021[78]). Importantly, the plan targets simplified authorisation processes for infrastructure and seeks to designate fixed and mobile ultra-high-speed infrastructures as strategic. Vouchers, initially for low-income households and thereafter other families and SMEs, will support the migration of users from copper to faster fibre networks.

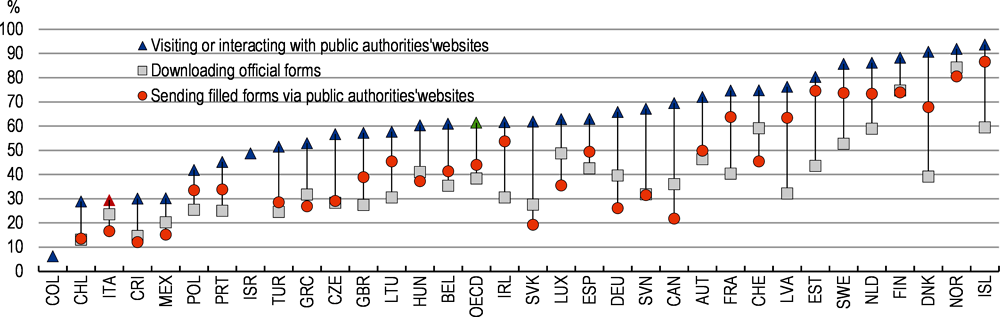

It is also necessary to invest in complementary intangible assets such as technical and managerial skills, since low management skills reduce the take-up of digital technologies (Andrews, Nicoletti and Timiliotis, 2018[76]). A number of countries have encouraged increased digital uptake by SMEs through encouraging digital platforms. Australia, Korea, Japan and France all provide support to SMEs to transition to online sales. In addition, the current push to raise the use of e-Government services, alongside behavioural shifts underway due to COVID, will help to increase familiarity with e-services (Figure 1.34 and Box 2.10). The broader shift to digitalising public services and processes forms part of efforts to improve the effectiveness of the public administration (see Chapter 2).

A growing number of OECD countries have found that establishing well-resourced, permanent bodies dedicated to developing policies and communicating their benefits can accelerate reforms. Although they are often called “Productivity Boards” or Commissions”, governments frequently set a wider mandate that can include green growth and social issues, as well as the public sector’s role and effectiveness. These bodies evaluate government policies and regulations in specific areas that are identified as priorities, and recommend reforms. They can identify trends, produce robust evidence, collect data and consult with stakeholders. In the process, they make the case for reforms by clearly presenting their benefits, which are often diffuse or uncertain. They support a “whole-of-government” approach, helping overcome fragmentation in policy-making across different public agencies or layers of government. They can serve as a platform to share ideas and help forge a common view, deepening national ownership of reforms, including in government bodies responsible for implementation.

These bodies fall into three broad types:

1. Stand-alone inquiry bodies, such as the Productivity Commissions in Australian, Chile and New Zealand. These are generally well-resourced with strong analytical skills, are independent and have inquiry and consultative mandates.

2. Advisory councils, such as the French Conseil National de Productivité, the US Council of Economic Advisers, and the Belgian Conseil National de la Productivité. These may tap into the existing knowledge of several well-established, high quality institutions without necessarily building their own capacity.

3. Ad hoc task forces, such as the Norwegian Productivity Commissions. These may be formed with temporary mandates to assess particular issues.

Countries’ experience suggests that these bodies are generally most effective when they can work autonomously and have strong internal analytical, consultative and communication skills. Occasional external audits or reviews can help ensure these bodies produce robust, relevant analysis. Institutions located outside government can better promote reforms that challenge vested interests and work towards longer-term policy goals. For example, in reviewing regulations in a priority policy area, such bodies operate at ‘arm’s length’ from regulators. They bring experience in consulting with different groups, in quantifying the benefits and costs of policies and regulations aimed at supporting productivity, competitiveness and sustainable growth, as well as in identifying alternative approaches.

Italy has committed to establishing a productivity board. Recent Economic Surveys of Italy (OECD, 2015[79]); (OECD, 2017[80]); (OECD, 2019[53]) have recommended that the board have the mandate to provide advice to the government on matters related to productivity, promote public understanding of reforms, and engage in a dialogue with stakeholders. Similarly, the European Council recommended in 2016 that all Euro-area countries establish national productivity boards (European Council, 2016[81])

Italy’s complex, multi-layered government suggests that an autonomous body with an inquiry capacity, sufficient research capacity and strength, and independence in communicating its analysis and recommendations may be most effective. A board of core experts who are able to commission and supervise research, utilising existing resources and institutions, would avoid creating an additional institution. This approach is similar to other EU countries. It could strengthen capabilities to monitor trends, assess the potential impacts of policy options, build a consensus for reform, and encourage policies that better support productivity, competitiveness, sustainability and inclusiveness.

Source: (Banks, 2015[82]); (Renda and Dougherty, 2017[83]); (European Commission, 2019[84]).

The planned insolvency code should be implemented alongside measures to improve their efficiency

Italy legislated far-reaching bankruptcy reforms in 2019. These reforms include enhanced governance procedures for firm directors, simpler procedures favouring out of court settlement, and the use of a specialised pool of bankruptcy experts to help resolve court cases (CERVED, 2020[85]). The early warning system prioritises early detection of bankruptcy problems based on firms’ capitalisation rates and financial performance, the thresholds of which vary according to firm size and legal status (Orlando and Rodano, 2020[86]). Assessments are undertaken at the firm’s request or due to compulsory referrals from institutional creditors or supervisory bodies such as auditors. The need for action is assessed by the local chamber of commerce’s crisis management committee (OCRI - Organismo di Composizione della Crisi d’Impresa). Incentives have been introduced for entrepreneurs to declare problems earlier. The reforms should help to reduce the time spent in courts, and the early warning mechanisms should help increase the speed with which corrective action is taken for firms in difficulty. These changes could potentially improve recovery rates for insolvency procedures, which are low in Italy (Figure 1.35). The initial 2020 implementation date was postponed to September 2021 in light of the COVID crisis.

Streamlining and digitising some of the early warning processes would help avoid the system becoming overwhelmed. (Orlando and Rodano, 2020[86]) estimate that 13 000 firms may be flagged by the early warning system, a fourfold increase in the number of firms that would normally be assessed for insolvency risk. Automating the prioritisation of cases to be considered by groups of business experts would allow the system to become operational without being overwhelmed. The Netherlands implemented bankruptcy reforms despite the pandemic, which has provided time for the system to adapt prior to the expected increase in bankruptcies following the COVID crisis. Sending standardised, non-binding guidelines and information about the options available to firms that are flagged on the early warning system before they need to be assessed formally by the local chamber of commerce could improve managers’ responses before requiring more costly and complex interventions.

Civil justice efficiency needs to improve

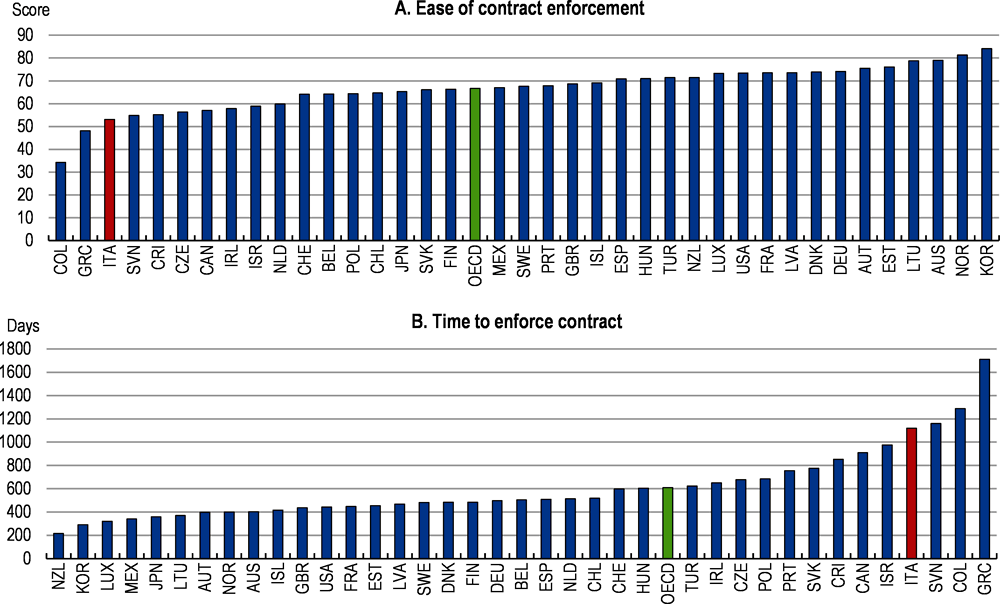

Reforms to the civil justice system helped reduce the time to complete civil cases at trial from 13 to 11 months between 2014 and 2019, and pending proceedings at civil courts fell by 23.7% over the same period. Backlogs in the court of appeals and tribunals have fallen 50% and 43% over the same period (Ministero della Giustizia, 2020[87]). Nonetheless, the system continues to struggle with a high backlog of cases (Council of Europe, 2020[88]). Civil and commercial litigious cases remain characterised by lengthy delays and high levels of uncertainty (Figure 1.36). Proceedings at Italy’s highest court lasted 1 293 days in 2019, the highest in Europe, where the average is 207 days (Ministero della Giustizia, 2020[87]). Improving the efficiency of the judicial system is critical to raise productivity (OECD, 2019[53]); (OECD, 2017[80]); (Ciapanna, Mocetti and Notarpietro, 2020[42]).

Authorities propose temporarily raising the number of staff in the civil justice system to tackle backlogs. The EUR 2.3 billion allocated by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan seems small considering the impact of court backlogs in raising uncertainty, reducing returns and lowering productivity. The amount will average EUR 0.5 billion per annum to support 8 000 fixed-term contracts and 1 000 honorary magistrates, who assist judges in drafting sentences, for two consecutive 2.5 year cycles (Relazione del Ministro sull’amministrazione della giustizia, 2020[89]). The total annual justice system budget is EUR 5.5 billion on personnel.

The number of personnel also needs to be accompanied by more effective ways of working. Parliament is currently considering a range of reform proposals for the civil justice system that should be swiftly approved to minimise the likely surge in cases from postponed legal disputes as well as the likely increase in court cases related to the COVID crisis. The bill before parliament includes proposals to reduce time spent in appeals, the procedure for forced execution (which will speed up bankruptcy cases) and rules on alternative dispute resolution, which have been raised in past surveys (OECD, 2019[53]); (OECD, 2017[80]). The bill includes facilitating exclusive online filing and payment in civil courts, reduced instances requiring multiple judges and greater administrative management oversight of judges, which will include their management of timeframes for procedures (European Commission, 2020[90]). A Commission has been established to report on tax justice and the backlog in tax cases. Specialised courts could reduce the likelihood of appeal. Greater promotion of the large number of existing alternative dispute mechanisms in Italy could also contribute to reducing court workloads and backlogs.

Tackling corruption could help improve confidence

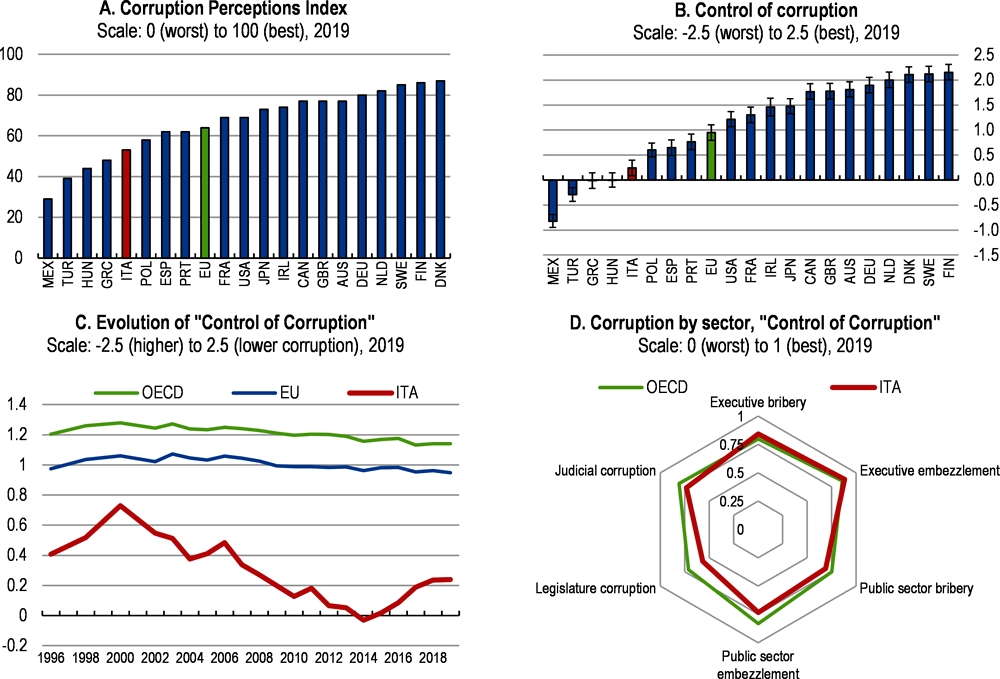

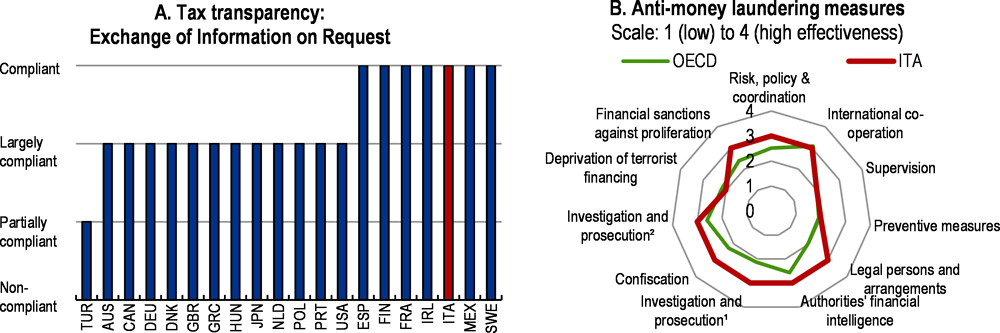

Italy’s anti-corruption regime, which was mostly recently augmented in January 2019 with the so-called bribe-destroyer law, includes a stringent legal regime to discourage offenders, with lengthy prison sentences, a revised regime for undercover operations and witness cooperation incentives, as well as tougher sanctions for corruption in the private sector (Maggio, 2020[91]); (European Commission, 2020[90]); (United Nations, 2018[92]). Despite these efforts, perceptions of corruption remain high and trust in institutions low (Figure 1.37). Greater emphasis on simpler regulations that are implemented more effectively, as outlined in Chapter 2, could reduce the complexity of the business environment, lower the demands on civil servants and reduce the scope for corruption.

To improve perceptions of corruption, oversight of the integrity and accountability of high-ranking powerful public officials such as politicians and magistrates must increase (Cantone and Caringella, 2017[93]); (Carelli, 2019[94]). The legal framework on lobbying is fragmented, opaque and unable to address conflict of interest risks associated with the move to private party funding. The limits to self-regulation of magistrates was demonstrated in 2019; efforts are needed to enhance integrity standards and safeguards within their governing body. Stricter regulation on political participation of magistrates would contribute to safeguard the real and perceived independence and impartiality of the judiciary (European Commission, 2020[90]); (Carelli, 2019[94]). Enforceable asset declaration and verification systems for senior public officials need to be established (United Nations, 2018[92]).

The establishment of a broad-based Anticorruption Alliance in early 2021 is welcome. Its efficacy will depend on the ability to convert its recommendations into actions. Chaired by the Judiciary and the Governor of the Banca d’Italia, a team of academic experts from a range of disciplines will consider issues raised in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan such as: i) the quality of regulation of public contracts; ii) the simplification of rules and procedures; iii) the quality of administrative and accounting controls; iv) the use of digital technologies to reduce the scope of corruption; v) regulatory shortcomings concerning lobbying; and vi) conflicts of interest (Relazione del Ministro sull’amministrazione della giustizia, 2020[89]).

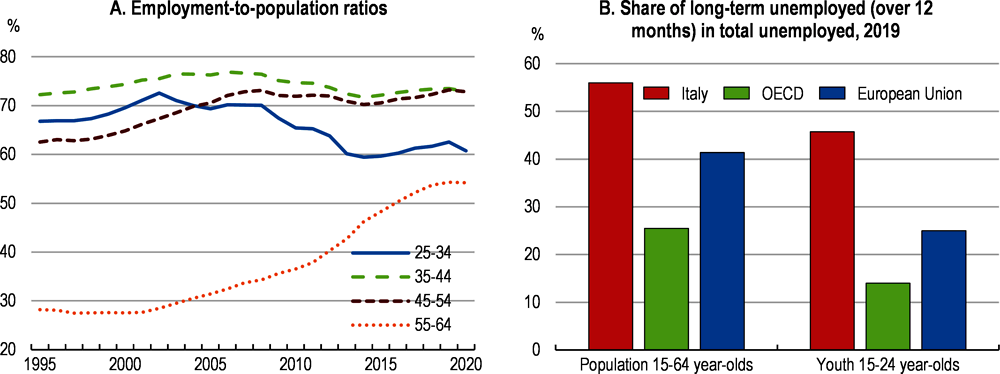

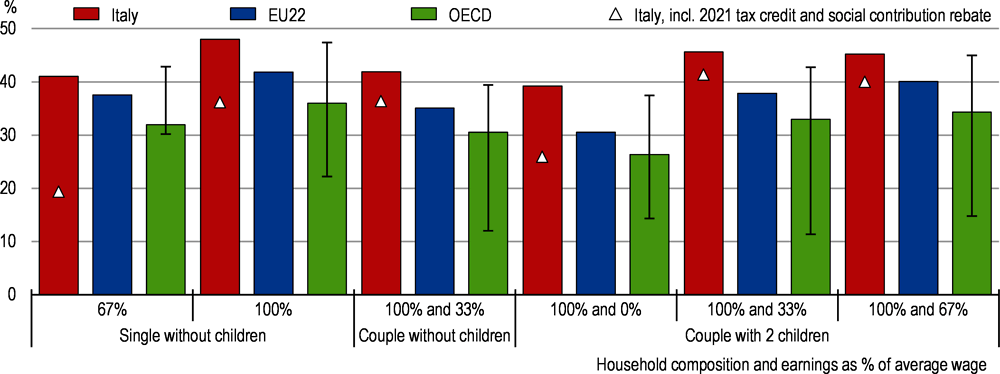

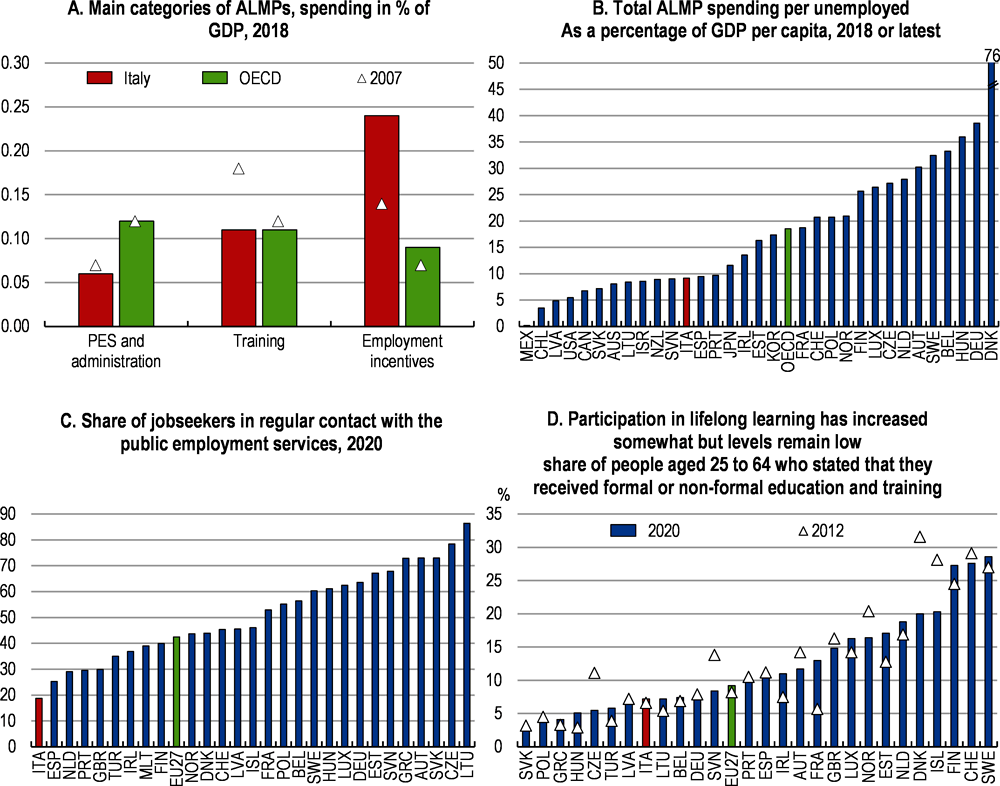

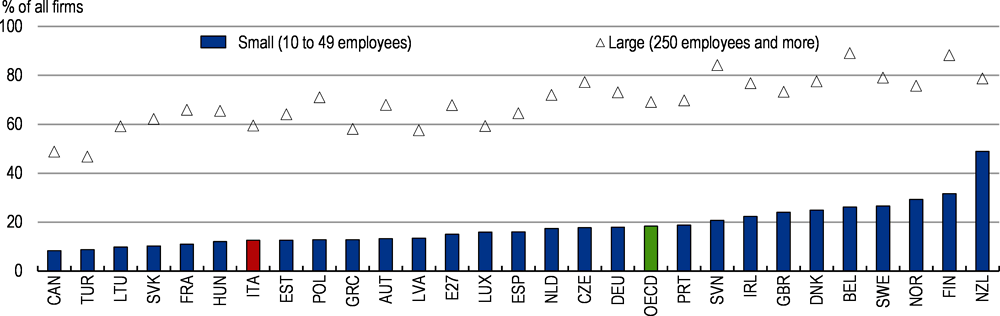

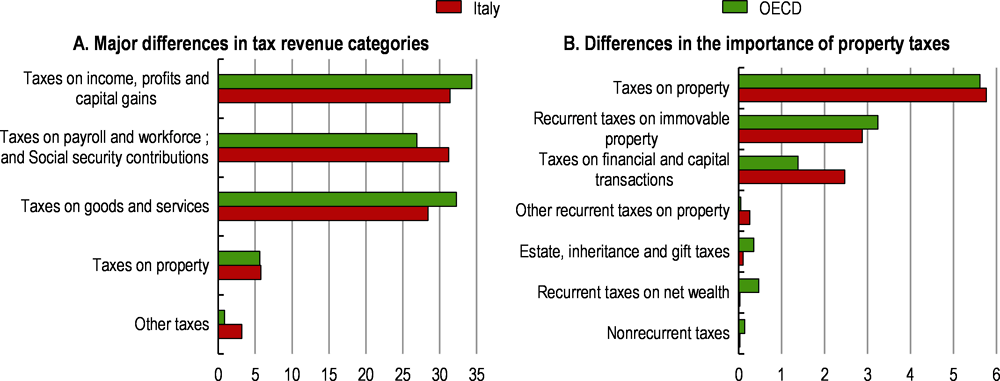

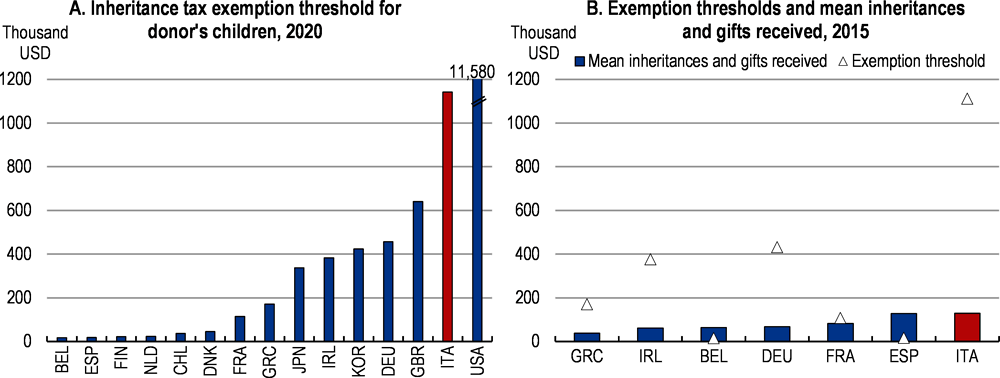

Raising employment, in particular for women and youth