5. Transforming the legal and regulatory environment for business in Uzbekistan

Responses to the survey suggest that firms consider ongoing legal and regulatory reforms to support the business climate in Uzbekistan to be moving in the right direction. At the same time, respondents note that there remains significant work to be done both on the implementation of these reforms, and on additional and complementary pro-competition reforms. These views are in line with OECD analysis on a number of areas highlighted by respondents, such as overall framework conditions for business, taxation, and competition policy. While the legal and regulatory environment for business in Uzbekistan has improved significantly developed since 2017, reducing many unnecessary fixed costs of doing business, the survey highlights a number of areas where more work is necessary to foster private sector development.

Responses to the survey reveal a mixed picture of how firms in Uzbekistan regard the speed, effectiveness and direction of ongoing reforms to support private sector development. For example, respondents overwhelming reported that Uzbekistan had a business-friendly climate, with 28% reporting that it was very friendly, and 54% reporting that it was somewhat friendly. Only 9% of respondents claimed that the business climate was not friendly. Yet this generally positive assessment belies a significantly more mixed appraisal of various local indicators of the health of the country’s business climate.

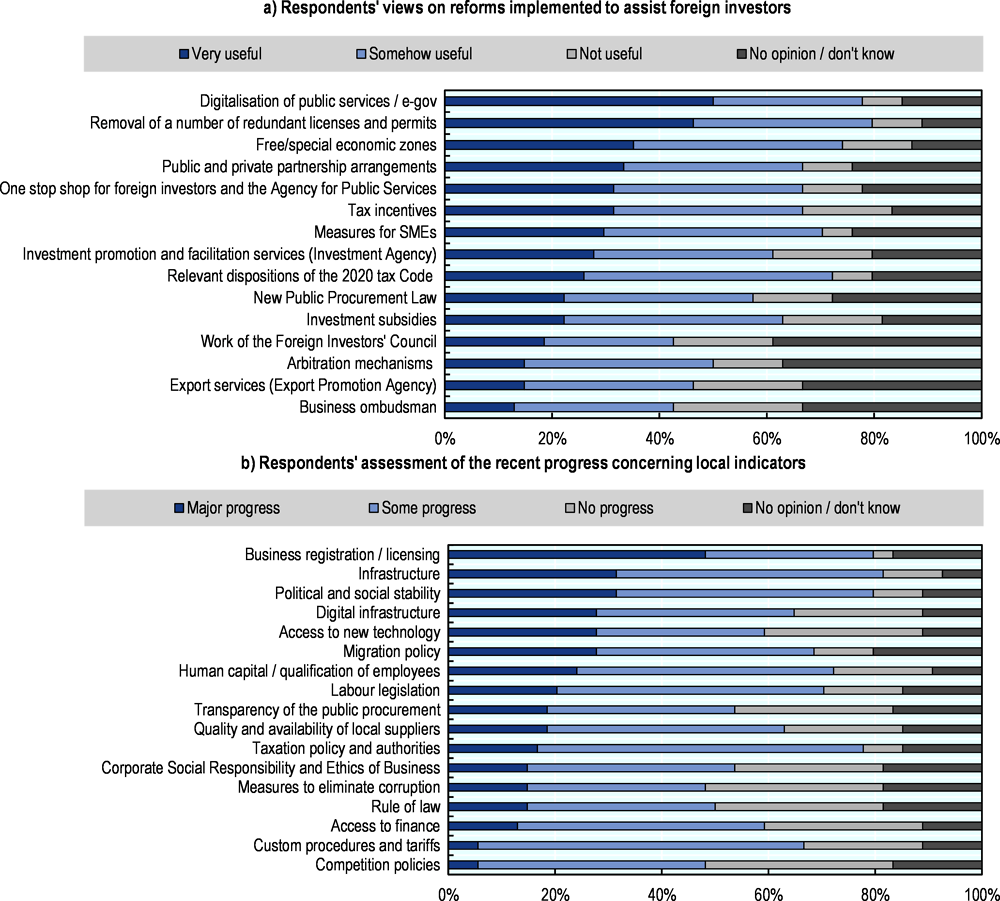

For example, a significant proportion of firms reported that business registration and licensing, labour legislation and migration policy were satisfactory, though significantly fewer rated these indicators as strong. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that these are areas where the government is continuing to implement reforms, and it is notable that a majority of respondents agreed that in each of these areas, the government had made some or major progress over the previous five years (Figure 5.1 b). Improvements to the registration and licensing requirements for firms was were among the key areas for action highlighted OECD Improving the Legal Environment for Business report, together with tax policy, another area where a significant majority of respondents report some or major progress, even if relatively few rate the current tax administration and policy as strong (OECD, 2021[1]).

At the same time, 50% or more of respondents rated over half the indicators as weak, a significantly larger proportion than the corresponding figure for strong, the highest figures for which were 20% (political and social stability) and 19% (business registration and licensing). The percentage of firms to rate the remaining 15 indicators as strong was less than 10%. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to note that a sizable plurality – and in many cases a majority – of firms assessed the progress of the government’s reforms in each area to be positive, which perhaps underscores the generally positive overall assessment offered by respondents.

5.1.1. Transparency and competition remain problematic areas for firms

A number of business climate issues emerged as particularly problematic through firms’ responses to the survey, each reflecting long-standing issues in the legal and regulatory environment. Transparency of public procurement remains a significant challenge for firms, with 56% respondents reporting this as weak, and only 2% reporting it was strong. This is an issue not just for European firms, but for the broader private sector, and indeed the public sector, which through its significant purchasing power is able, for example, to privilege low-carbon and sustainable technologies and solutions through procurement. The reverse is also true – poor procurement decisions now may make it harder for the government to achieve long-term targets such as net zero should those decisions result in the grandfathering of carbon intensive technologies or modes of organisation. Addressing transparency issues in procurement is therefore not only important for increasing the opportunities for firms, but also for accelerating the deployment of the types of sustainable and productivity-enhancing infrastructures and technologies necessary for the government’s stated socio-economic ambitions. Access to finance is another major issue, with the same proportion of respondents reporting that it is strong (2%) and weak (56%). Working on access to finance issues, particularly for SMEs, remains a key pillar of OECD engagement with the Uzbek government.

One major issue that emerges from the survey is that of competition. While 56% of respondents reported that competition policies were weak, none reported that they were strong. This is a key weakness in Uzbekistan’s business climate and a major barrier to the development of a resilient and inclusive private sector. On each of the sub-indicators for competition policy, a majority reported that they were weak (institutional framework for competition policy – 52%; concentration control – 54%; measures in place against cartels and concerted practices – 57%; control of market dominance and monopoly practices – 67%). This is an issue about which the authorities are aware, and on which they are working with the OECD to improve (OECD, 2022[2]).

As representatives of European businesses in Uzbekistan, firms were also asked to assess government measures that are designed to support foreign investors (Figure 5.1), For 11 of the 15 measures that respondents were asked to assess, a majority considered government efforts to support foreign investors to be either somewhat or very useful.

Respondents were not asked to report the relative importance of each measure, simply to answer whether and to what degree it was or was not useful. It therefore is not possible to determine from the responses the extent to which any one measure has affected investment decisions taken – or not – by European firms in the country. Nevertheless, it is notable that two areas where government reforms have been extensive in recent years – the digitalisation of public services and the removal of redundant licenses and permits – were the two areas rated the highest for being ‘very’ useful (50% and 46% respectively), which echoes the findings of earlier OECD work on these areas. A significant plurality of firms responded they were unable to assess the usefulness of a number of measures, perhaps due to a lack of awareness of these among the European business community.

In many ways, the responses to the survey align with the OECD’s own analysis of the business climate in Uzbekistan. That there has been major progress in improving the business climate is clear, notably through the market liberalisation reforms discussed in Chapter 4, as well as through numerous reforms to the legal and regulatory environment for entrepreneurship and investment (OECD, 2021[1]). At the same time, the impact of these reforms on the de facto operational environment for firms remains limited, in large part due to only piecemeal progress in implementing reforms that address competition, investment and development in certain key framework conditions for business, and in consistently implementing the de jure changes to the regulatory environment.

Since beginning a sweeping set of reforms in 2017, Uzbekistan has made significant steps towards improving the legal and regulatory environment for business. Activity has been intense on the part of policymakers and regulators, and in recent years there has been a large volume of new legislation that affects, directly or indirectly, private enterprise in the country. Many recent legislative changes have addressed long-standing uncertainties and weaknesses in the legal and regulatory environment for business, notably the 2020 Law on Investment and Investment Activities and the substantially revised 2020 tax code, while an entrepreneurial code, which will condense numerous hitherto disparate pieces of business-related legislation into one law, was drafted in 2022.

At the same time, in 2017-2022, much of the government’s policy focus was on what might be described as the low-hanging fruit of reform. Certain notable barriers to business were certainly addressed – it is, for example, significantly simpler and cheaper to start a business – but other barriers, often related to inveterately difficult policy and political economy issues, remain either in place or only partially alleviated.

5.2.1. A number of high-level strategies guide the reform process

A number of high-level strategy documents guide the reform process. The guiding strategic document for the initial stages of the reform process was the National Development Strategy for 2017-21 (NDS), which set out the government’s plans to liberalise the economy, reduce the role of the state, strengthen governance and increase the role of the private sector and foreign investment (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2017[3]). The NDS was supplemented by the operational 2019-21 Reform Roadmap, (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2019[4]). Both documents and a large number of presidential decrees, laws and bylaws, are indicative of the breadth and depth of the reform agenda. In 2022, the NDS was replaced by the National Development Strategy for 2022-2026, which builds on the priorities of the earlier document and adds a number of specific targets: a 1.6-fold increase in GDP per capita by the end of the project period, per capita income to reach USD 4,000 by 2030, reducing annual inflation to 5% by 2023, increasing the volume of industrial production by 40% and increasing the share of industry in GDP, and achieving a number of targets around climate change and sustainability, electricity generation, and WTO accession.

To support the implementation its private sector and business climate development priorities, the government has undertaken significant institutional reform. It has created new institutions and agencies, reformed existing ones, and increased the autonomy of certain existing institutions. These reorganisations represent a concerted effort to ensure that relevant institutions are empowered and able to implement the government’s reform agenda, as well as being representative of the general trend in downsizing and streamlining the public administration. A number of such developments are detailed below:

The government established the Strategic Reforms Agency (SRA), under the president’s office, which both oversees and evaluates ongoing reforms whilst also being tasked with formulating additional possibilities for policy change and reform.

The government established the Ministry of Investment, Industry and Trade (MIIT) and the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), with these being tasked to improve the overall business and investment climate.

To support privatisation, the government established the State Assets Management Agency (SAMA), which replaced the now-dissolved State Committee on Privatisation, Demonopolisation and the Development of Competition.

The government also created the Capital Markets Development Agency (CAMA), which is working with SAMA on its privatisation strategy as well as independently on establishing a functioning capital market in Uzbekistan.

The government also created the Agency for the Development of Small Businesses and Entrepreneurs under the MEPR, with the MEPR also responsible for non-agricultural land reforms and the development of the country’s urbanisation strategy.

The government also established a new body to co-ordinate a horizontal approach for the development, coordination and implementation of anti-corruption policy through interdepartmental commissions at the national level (Republican Inter-Agency Commission), and across the country’s regions (territorial inter-agency commissions).

A business ombudsman has been created under the aegis of the Presidential Administration.

In 2022, the government drafted a new Entrepreneurial Code (EC), which consolidates a number of hitherto disparate pieces of business-related legislation. The current draft EC includes key sections that are organised in line with international standards, including clear definitions of: businesses, in particular of SMEs with associated thresholds and a time-bound reference period, as well as a clear distinction between the definition and purpose of business entities and social enterprises; their rights and obligations; the provisions needed for a sound regulatory framework for businesses, in particular the definition of the procedure for business registration and closure, an important step for enterprise formalisation; and, the rules concerning the nature and modalities of state support to businesses. In addition, the document spells out a hierarchy of normative acts between international treaties and national laws, as it gives primacy to international treaties ratified by Uzbekistan over the EC, and primacy of the EC over all other legal acts related to entrepreneurship (current Article 2).

5.2.2. Regulatory reforms have significantly simplified business registration and licensing

Opening a business has become far easier. The registration process for domestic entrepreneurs has been significantly improved, with a shift towards online registration and the use of digital platforms (World Bank, 2019[5]). Businesses can register physically at one of the Public Service Centres, located in Tashkent and with branches in each region, or through the online registration platform www.fo.birdacha.uz. Minimum capital requirements for establishing a Joint Stock Company (JSC) or a Limited Liability Company (LLC) were abolished in March 2019 to establish (Dentons, 2019[6]). Renewal procedures every three years involving an apostille could also be discontinued.

The licenses and permits needed for running a business continue to be streamlined. In April 2018, the two presidential decrees –“On Measures to Further Reduce and Simplify Licensing and Licensing Procedures in the Field of Entrepreneurial Activity” and “On Improving Business Conditions” acknowledged that many licenses and permits did not meet modern standards and had become obsolete. Moreover, they recognised that the process of license issuance was too slow and that government bodies’ interaction remained too limited. The decrees called for reducing the number of activities requiring a license and the time required to obtain licenses, removing time limits on most licenses, and authorising applicants to carry out licensed activities if the public authorities failed to meet the established deadlines for processing licence applications (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2018[7]).

5.2.3. The government is continuing reforms to the tax adminsitration

Since 2017, the government has been reforming the tax system, with changes intended to simplify tax policy and administration. Starting in 2018, personal and corporate taxes, for all firms of all sizes, were unified at a flat rate of 12%; firm size classifications changed from being employee-based to turnover-based, and a new unified rate of tax for small firms was introduced at 4% of turnover (World Bank, 2021[8]). Rules were also changed to allow small firms to pay VAT, which in turn has allowed them to operate more efficiently in the VAT supply chain to larger firms – something that has been identified as a barrier to SME growth (OECD, 2021[1]). The new code was introduced in January 2020, and its introduction follows a major overhaul of the country’s tax system (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2019[9]). Despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, tax revenues increased from 19.2% of GDP in 2019 to 19.5% of GDP in 2020, due in part to an increase of the tax base and increased employment formalisation offsetting revenue loss from lower tax rates (World Bank, 2021[8]).

5.2.4. The government’s privatisation programme has accelerated in recent years

To address the role of the state in the economy, the government has begun to implement a broad programme of corporatisation as it prepares for the privatisation of a number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2018[10]). One of the fundamental challenges for policy-makers and investors in understanding the extent of the state’s presence in the economy is a question of measurement and classification, with legislation classifying only 100% state-owned state-unitary enterprises as SOEs (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2006[11]). The narrow definition used by authorities means that many other types of firms with direct or indirect state involvement are not included in official statistics, creating a potentially misleading impression of the state’s involvement in the economy. For example, while the government reports that there are 257 directly owned joint-stock companies in Uzbekistan, a recent ADB study found that a further 329 JSCs were owned indirectly by the state, suggesting that almost three quarters of all such firms in the county were controlled, wholly or partially, by the state (Abdullaev, 2020[12]). Whilst it is encouraging to see the state recognise its control beyond the strict definition used by the authorities by including LLCs and JSCs in their calculations, there remain challenges in ensuring that analyses of state ownership are reflective of the de facto reality in the economy.

The government has already begun taking practical steps in implementing its privatisation agenda with technical assistance from IFIs, including the EBRD, the ADB, and the World Bank (World Bank, 2019[13]): tariffs have been raised to improve the economic viability of a number of utilities SOEs; legislation has been passed allowing the privatisation of non-agricultural land plots (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2019[14]); and, in 2019 a government resolution approved the selling of state shares in the chemical, hydrocarbon, mechanical engineering, banking and insurance sectors (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2019[15]). The government review of the vertically integrated national air company (NAK) is indicative of the its SOE reform intentions, with a presidential decree already reorganising the functions of NAK into new legal entities with a plan to engage in PPPs for the operation of the previous monopoly’s assets (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2018[10]). The privatisation process must contend with what remains a fragmentary and unconsolidated legal landscape, which weighs on the administration and valuation of assets that may be privatised. For example, the law that determines the valuation of SOEs and state assets dates from 1992 and has never been amended, which may create difficulties in the accurate valuation of assets in the contemporary context.

5.2.5. A clearer and more liberal regulatory framework is being put in place to support foreign investment

In 2020, a new Law on Investment and Investment Activities (LoI) was enacted, replacing and expanding earlier laws from 1998 on foreign investment and investor protection, among others. An investment law can help provide transparency and clarity in a country’s investment regime, stipulating the conditions for market access, as well as the protection of investment and the settlement of disputes. Many governments, particularly among OECD members, regulate investment through laws of more general application, but over 100 countries have enacted a specific investment law as a signalling device to potential investors.

The 2020 LoI is designed to systematise existing laws and by-laws and to level the playing field for foreign and domestic investors. As such, it applies to both foreign and domestic investors, although it excludes many forms of investment, such as those carried out under production sharing agreements, concession contracts and public-private partnerships, as well as in special economic zones. It is therefore unlikely to apply to many high-value natural resources and infrastructure investment projects, among others, where project-specific contractual arrangements with the state are commonplace. At the same time, it is unclear whether laws governing these other areas of activity (such as PPPs or SEZs, or project-specific contracts with the state) can supersede clauses in the LoI, thereby providing the government a loophole for expropriation or nationalisation. The question of legal hierarchy is one that the government must clarify for businesses, domestic and international alike, so that they can have certainty over the legal finality of acts such as the LoI. For investments falling within the scope of the LoI, the new law retains a broad set of generous protections, many of which apply equally to foreign and domestic investments. It includes a general principle of non-discrimination and guarantees of national treatment, protection from nationalisation (although not indirect expropriation) and transferability of funds abroad.

The new law also addresses an issue faced by investors in certain former Soviet republics, notably the attempts by some parts of central and regional governments to nullify licences for foreign investment projects under the pretext of violations of environmental or other regulations. It also insulates covered investors against detrimental regulatory changes by providing regulatory stability for a period of ten years from the time of the initial investment. While stabilisation guarantees are common in the region, they are far less common in other regions of the world as they can severely tie the hands of governments. An alternative – and more flexible – approach might be to include a provision on indirect expropriation in the law itself, subject to certain clear exceptions.

The new law introduces a four-stage process for resolving disputes concerning foreign investments. While there is some ambiguity in the drafting of the relevant provisions, the new law appears to list these four stages as mandatory and consecutive steps. An investor may only seek to commence international arbitration proceedings against the state if it has first attempted to resolve a dispute through negotiations, mediation and litigation in the Uzbek courts. The new law envisages the possibility of investor-state arbitration under investment treaties or contracts but stops short of providing open-ended consent of the state to arbitrate all investment disputes.

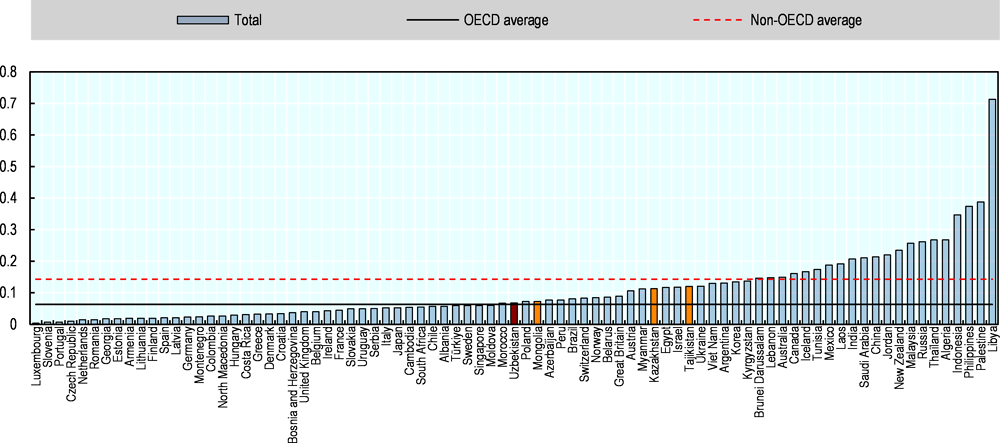

The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index demonstrates that Uzbekistan is relatively open to foreign investment. The country is in line with OECD average for statutory restrictions and outperforming other countries in the region included in the FDI Index, such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia (Figure 5.2 )

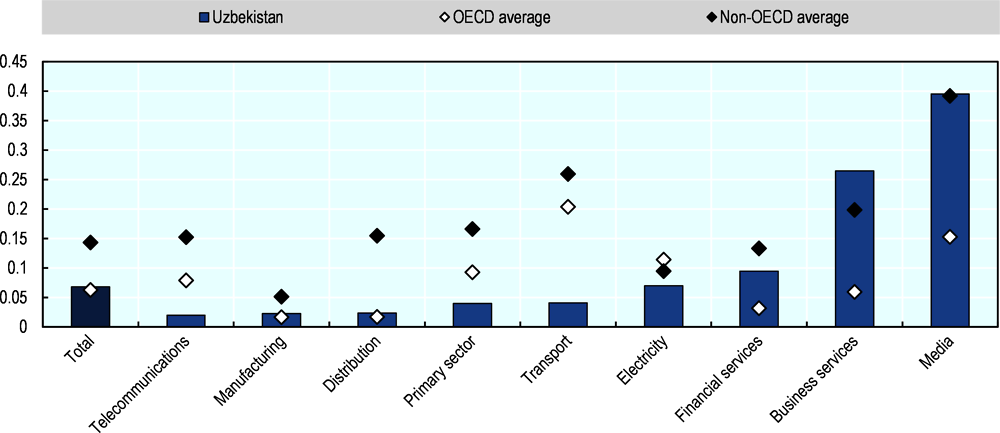

Restrictions remain for mass media, telecommunications, power generation, business services and other sectors and are particularly high in media, financial and business services (Figure 5.3). Some sectoral restrictions are fairly common, and reflect national concerns, but others could be re-evaluated to assess whether their intended impact justifies the possible deterrent effect they might have on inflows. This is particularly the case in the financial and business service sectors. Beyond the immediate impact on inflows, governments should also consider how restrictions affect downstream industries and consumers. At the very least, the government should communicate restrictions clearly on the online investment portal. As sectors currently dominated by SOEs are to be opened up, conditions for foreign investors’ participation in the privatisation process will also need to be clearly defined and communicated. The EBRD is currently working with the government on a new law on privatisation, and is encouraging the government to ensure the law improves transparency surrounding the privatisation process and the participation of international investors therein.

Sectoral FDI incentives are numerous in the industrial, hospitality, pharmaceuticals and natural-resource sectors and mostly consist of tax benefits. Companies operating in Special Economic Zones (SEZ) also benefit from tax incentives, as well as customs benefits and services. There are currently twelve SEZs in the country, some of which have a sectoral focus (pharmaceuticals, sport, agriculture and tourism) (Dentons, 2019[6]). Whilst the laws for SEZs may be fairly clearly established, uncertainty arises concerning the interaction of national laws with these demarcated jurisdictions. This issue is not limited to Uzbekistan; across the region the issue of “legal hierarchy”, i.e., understanding definitively how national legislation interacts with SEZ rules, creates uncertainty in the legal environment for business. Plans to reform these zones, better define their objectives and reassess incentive packages have been discussed but have not yet materialised according to the CCI.

Limited progress has been made in liberalising key factor markets such as transport and land, but the purchase and transfer of the latter remain difficult. Foreign participation in the privatisation process of non-agricultural land is, however, possible only through local incorporation. Foreign investors and foreign-owned companies established in Uzbekistan are allowed to hold lease titles to land, but they are subject to different rules regarding the needed authorisation by the state in relation to leasing such lands. Foreign investors and foreign-owned companies require approval by the Cabinet of Ministers, while domestically-owned legal entities require approval only from district and cities khokim (governor). The dual process, and the existence of specific regulations on granting land plots to foreign legal and individuals (e.g. in Tashkent; see the “Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers on granting land plots to foreign legal and natural persons in Tashkent”), raise concerns about discriminatory treatment against foreign investors and are reflected in the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.

As it continues to open up additional sectors of the economy to foreign investors, the government should prioritise ensuring that the LoI and related legislation are properly implemented. This should involve a concerted effort to raise the capacity of government agencies and to develop the capabilities of the MIIT to help with implementation and investor needs. In particular, Uzbekistan has recently created an Investment Promotion Agency under the MIIT that could be the entry point for investors and inform them of regulatory requirements and recent changes, as well as helping them meet these requirements (OECD, Forthcoming[17]). Stability of stakeholders is an essential feature of effective investment relations that is regularly cited by investors.

Effective Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) in OECD members, such as Turkey and Ireland, are active generators of investment and knowledge centres for investors, beyond promotion and image building activities (President of Turkey’s Investment Office, 2019[18]). Uzbekistan’s IPA could go beyond information provision and deliver advisory and aftercare services for investors, including on regulatory aspects by co-ordinating with other agencies, especially tax authorities and licensing bodies, to avoid multiplicity of contacts and inconsistent administrative procedures.

The government should also strive to remove further sectoral restrictions for investors, including in the financial and business service sectors. It could also communicate restrictions clearly on the online investment portal. As sectors currently dominated by SOEs are to be opened up, conditions for foreign investors’ participation in the privatisation process will need to be clearly defined and communicated.

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, respondents highlighted competition policies as the weakest aspect of the legal framework for business in Uzbekistan, as well as being the area where respondents had seen the least progress over the past five years. When asked to give their opinion on three specific aspects of competition policy – control of market dominance and monopoly practices, measures in place against cartels and concerted practices, and concentration control – progress was rated as weak by over 50% in each instance (as high as 67% for market dominance and monopoly practices). The government of Uzbekistan is aware of the need to seriously improve competition policies if the broader ambition of private sector development and investment attraction is to be achieved, and in 2022 solicited OECD help in this area (OECD, 2022[2]).

The picture that emerges is one where the private sector continues to be beset by a myriad of competition-related issues (for example, the practice of preferential lending to SOEs below market rates, tax breaks for certain SOEs and even quotas in certain industries), hampering incentives to invest and grow. Yet as with the general legal and regulatory framework for business outlined in section 5.2, these complaints and concerns come amidst a large number of changes that have been put in place precisely to level the playing field for private business. That firms have yet to feel the benefits of these legal reforms speaks to challenges with implementation, the scope of the legal reforms made so far, and a complicated range of adjacent reforms (such as in land and other factor markets, or corporatisation and privatisation of state assets) that that are required to level playing the field between public and private enterprise.

5.3.1. Reforms to competition law and enforcement have been a key part of the broader reform process

Competition law and policy have formed an important part of the ongoing, broader reform agenda of the government of Uzbekistan. One of the first important steps towards creating a strong competition framework was the establishment of the Competition Promotion and Consumer Protection Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan (ACRU) in 2019, which was achieved by institutionally reorganising a larger regulator that had previously overseen both competition and privatisation policy. The ACRU, which is designed to be an independent regulatory, has the task of overseeing the implementation of competition and other market-related policies, such as consumer protection, advertising, and tackling corruption that distorts competition.

The regulator is already very active. Since its inception, it has already assessed more than 5,500 legislative acts in terms of their possible impact on market competition, conducted more than 2,000 antitrust investigations, cleared around 500 mergers, and has organised around 100 advocacy events aimed at improving the awareness of public bodies regarding the importance of market competition (OECD, 2022[2]).

In addition to the institutional changes to support competition policy, the government drafted a new law on competition in 2022. The law codified a number of important changes to the country’s competition framework, including: new rules for vertical agreements; an extended list of behaviours considered abuse of dominance; merger control in cases of establishment of joint ventures; enhanced enforcement powers, including the right to issue fines; the inclusion of state aid regulation with ACRU responsible for oversight; regulation on the extent of the state in the economy; and a framework for regulating digital markets.

Following the assessment conducted by the OECD in 2022, the Organisation made a number of targeted recommendations, which, if implemented, would directly address many of the concerns that firms continue to report. These recommendations included improving the independence and mandate of the ACRU, including by ensuring that the ACRU has the budget and resources it needs to fulfil its mandate, improving both the legal provisions for addressing cartels and abuses of dominance as well as ensuring adequate powers for enforcement, and ensuring effective powers and procedures for the ACRU to be able to promote competitive neutrality.

These recent changes to Uzbekistan’s competition law, on top of the conditions that were already in place, mean that the country has a strong de jure competition law regime, with Uzbekistan performing well against its regional peers in an international benchmarking exercise conducted by the OECD (OECD, 2022[2]). Its highest scores were in the categories of enforcement policies against anti-competitive behaviour and advocacy, and lowest in the area of probity of investigation. There nevertheless remains a significant deal of work to be done to improve the legal framework for competition, though the government’s decision to submit to an OECD review of competition policy is in itself an important indication of the seriousness with which the government takes the matter.

References

[12] Abdullaev, U. (2020), State-Owned Enterprises in Uzbekistan: Taking Stock and Some Reform Priorities, ADBI Working Papers, No. ADBI Working Paper 1068, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/560601/adbi-wp1068.pdf.

[6] Dentons (2019), Doing business in Uzbekistan.

[27] European Union (2019), European Union Supports Uzbekistan’s Accession to WTO, https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/burkina-faso/59579/european-union-supports-uzbekistan%E2%80%99s-accession-world-trade-organization-wto_en.

[25] ITF (2019), Enhancing Connectivity and Freight in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/connectivity-freight-central-asia_2.pdf.

[32] OECD (2023), FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FDIINDEX.

[16] OECD (2023), OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, Uzbekistan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FDIINDEX.

[31] OECD (2023), OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, Uzbekistan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/trade-facilitation/.

[2] OECD (2022), An Introduction to Competition Law and Policy in Uzbeksitan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/an-introduction-to-competition-law-and-policy-in-uzbekistan.pdf.

[20] OECD (2021), Beyond COVID-19: Prospects for Economic Recovery in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Beyond_COVID%2019_Central%20Asia.pdf.

[23] OECD (2021), Boosting the Internationalisation of Firms through better Export Promotion Policies in Uzbekistan, OECD Eurasia Policy Insights, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Monitoring_Review_Uzbekistan_ENG.pdf.

[1] OECD (2021), Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/Improving-LEB-CA-ENG%2020%20April.pdf.

[19] OECD (2020), COVID-19 Crisis Response in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=129_129634-ujyjsqu30i&title=COVID-19-crisis-response-in-central-asia.

[24] OECD (2017), Boosting SME Internationalisation in Uzbekistan through better Export Promotion Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/competitiveness-programme/central-asia/Uzbekistan_Peer_review_note_dec2017_final.pdf.

[17] OECD (Forthcoming), Investment promotion practices in Eurasia.

[33] OECD (Forthcoming), Monitoring Report: Improving the Legal Environment for Business and Investment in Central Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[18] President of Turkey’s Investment Office (2019), Official website, http://www.invest.gov.tr.

[22] Republic of Uzbekistan (2022), Development Strategy of New Uzbekistan for 2022-2026, https://uzembassy.kz/upload/userfiles/files/Development%20Strategy%20of%20Uzbekistan.pdf.

[9] Republic of Uzbekistan (2019), Draft Tax Code, https://regulation.gov.uz/ru/document/7232-nalogovy_kodeks_respubliki_uzbekistan (accessed on 2020).

[15] Republic of Uzbekistan (2019), Law No. ZRU-522 “On privatization of non-agricultural land plots”.

[14] Republic of Uzbekistan (2019), On Further Measures for the Implementation of the Mechanisms for Attracting FDI into the Economy No. 4300.

[4] Republic of Uzbekistan (2019), Reform Roadmap 2019-21.

[7] Republic of Uzbekistan (2018), Decree of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Measures to Further Reduce and Simplify Licensing and Licensing Procedures in the Field of Entrepreneurial Activity, as well as Improving Business Conditions, http://www.lex.uz/ru/docs/3676962 (accessed on 13 May 2019).

[10] Republic of Uzbekistan (2018), Presidential Decree 5584 On Measures to Improve Civil Aviation.

[3] Republic of Uzbekistan (2017), National Development Strategy 2017-21.

[30] Republic of Uzbekistan (2017), State Programme for the Realisation of the Strategy on Five Priority Areas for Development of the Republic of Uzbekistan 2017-2021.

[11] Republic of Uzbekistan (2006), Law on State Owned Enteprises, https://nrm.uz/contentf?doc=372435_polojenie_o_gosudarstvennyh_predpriyatiyah_(prilojenie_n_1_k_postanovleniyu_km_ruz_ot_16_10_2006_g_n_215)&products=1_vse_zakonodatelstvo_uzbekistana.

[28] State Asset Management Agency of Uzbekistan (2020), Privatization as a Driver of Economic Reform.

[21] The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics (2023), Small Business and Entrepreneurship, The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, Tashkent, https://stat.uz/en/official-statistics/small-business-and-entrepreneurship.

[29] World Bank (2022), Uzbekistan: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic, World Bank, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/933471650320792872/pdf/Toward-a-Prosperous-and-Inclusive-Future-The-Second-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic-for-Uzbekistan.pdf.

[8] World Bank (2021), Assessing Uzbekistan’s Transition: Country Economic Memorandum, World Bank, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/862261637233938240/pdf/Full-Report.pdf.

[26] World Bank (2020), Doing Business 2020, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1440-2.

[5] World Bank (2019), Doing Business 2019: Uzbekistan, Training for Reform, World Bank Group, DC, https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/u/uzbekistan/UZB.pdf.

[13] World Bank (2019), Press Release: Support to Public Financial Management and State-Owned Enterprises Reforms to Benefit Uzbekistan’s Citizens and Economy.