1. The future of learning and implications for teaching

Pedagogies for future ready student competencies and outcomes

Students face a future filled with uncertainty and change. For education systems to continue to remain relevant, they must empower students to navigate these changes and succeed in the future by equipping them with the requisite knowledge, skills and values. Teachers are key enablers of this endeavour, and it is imperative that governments and teacher organisations collaborate to support teachers in exploring and enacting pedagogies, and designing learning environments that support student attainment of future-ready competencies, through policies, processes and teacher professional development.

Approaches to facilitate students’ development of 21st Century Competencies (21CC)

Ways to ensure that our educators have the skills and capacity to better support students in attainment of 21CC and other future-ready skills through a values-based education

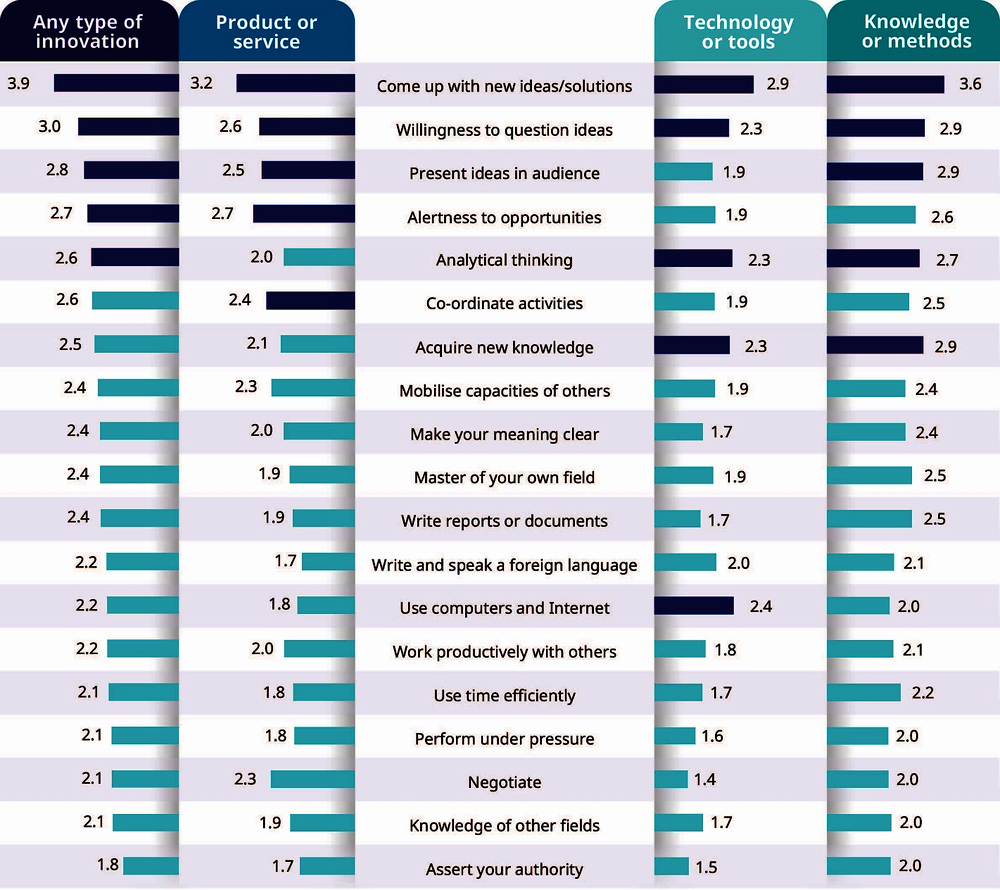

For the most innovation-driven jobs – from AI to the creative arts to renewable technologies – employers are looking for employees that create value. Workers that are able to thrive in this environment are the ones that have the skills and mindset to ask questions, collaborate with others and think creatively. These skills can be taught and nurtured in the classroom, and require coherent pedagogical approaches. This doesn’t necessarily require wholesale curriculum change or new resources: subtle changes to teaching methods can go a long way.

OECD countries are increasingly driven by innovation. Workers are expected to contribute to change, to continually seek ways to leverage new technologies and ways of working to remain competitive. What’s more, as digitalisation and artificial intelligence advance, the premium on creativity and critical thinking increases compared to routine skills, which are more susceptible to automation. In the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2023 report, companies considered creative thinking the second most important skill for workers, ranked only behind analytical thinking. Other research by companies like LinkedIn have found similar results (Petrone, 2019[2])

But innovation isn’t only important for the job market. The knowledge, skills, attitudes and values; insights, ideas, techniques, strategies and solutions that today’s students develop will be key to solving many of the world’s most pressing challenges—from climate change to poverty. These require the ability to put creative thinking into practice, working effectively with others to explore, analyse and implement new ideas. They also call on students to consider the interests of others. After all, to solve existential issues like climate change, we must develop the values and capabilities in today’s generation to ensure that the interests of future generations are given full weight in our decisions (Cignetti and Fuster Rabella, 2023[3]).

These ideas matter for education, too. Critical thinking acts as a powerful stimulus to learning itself, deepening students’ absorption in their learning, activating higher order cognitive skills and stimulating emotional development and resilience. This was important in helping students navigate the complexities and challenges of COVID-19-induced remote learning by fostering adaptability, problem-solving, engagement, and emotional well-being.

Teachers have a critical role to play in nurturing these skills and behaviours among students. They can unlock student creativity by using teaching practices that encourage students to explore, generate and reflect upon ideas. They can build empathy by linking learning content to real-world scenarios and the lived experiences of students. They can help students develop the capacity to identify positive future outcomes and develop the judgment to arrive at those outcomes by promoting horizontal thinking across diverse areas of knowledge (OECD, 2023[4]). In other words, teachers can help organise experiences, relationships and content in order to foster expanded ambitions for young people. This movement, which has been called “deeper learning, or “4-Dimensional Education”, is centered around authentic, challenging learning tasks that are relevant to and engaging for the learner (Hannon, 2023[5]).

It's no coincidence that high performing systems integrate formal guidelines and requirements related to teacher training on developing and assessing creativity and on developing or assessing student creativity directly. Having all three of these is uncommon. Fewer than 70% of jurisdictions surveyed have guidelines or requirements on developing students’ creativity and requirements and guidelines for assessing student creativity are rarer still: only 44% of primary and 40% of secondary education systems reported having these in place (Cignetti and Fuster Rabella, 2023[3]).

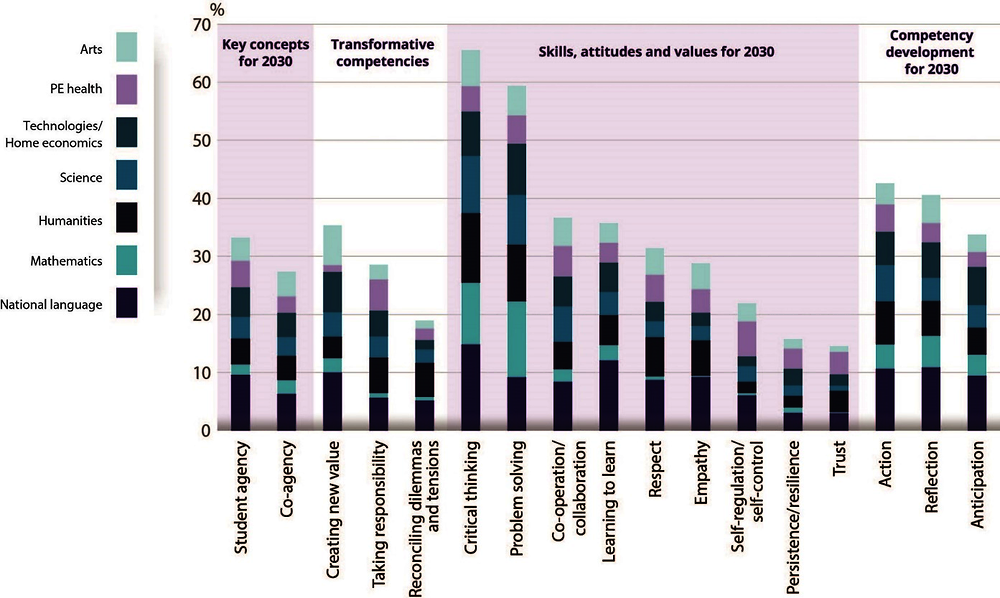

For another, creative thinking needs to be taught. This may sound obvious, but only 60% of education systems that took part in the 2022 PISA survey include references to creative thinking in all or almost all curricular subjects for primary education. The reasons for excluding it vary, but most survey responses flagged an overcrowded curriculum and insufficient teaching team, lack of assessment focus and lack of teacher training as the main barriers. Policies to promote the integration of creative thinking in the curriculum can lower these barriers.

More broadly, barriers to value creation in education for teachers encompass a range of systemic, institutional, and personal challenges. In addition to the above, a lack of support and recognition from school leadership and the community can demotivate teachers, while technological challenges and resistance to change impede the integration of new methodologies. Cultural and social barriers in classrooms also present obstacles to leveraging diversity as a strength. Overcoming these barriers requires a concerted effort involving policy reforms, increased investment in resources, professional development, and a cultural shift towards embracing innovation and diversity in education.

Teaching value creation doesn’t necessarily require a radical curriculum change. Simple techniques can be employed in the classroom to build students’ skills. For one, situating what students learn within a ‘big picture’ that illustrates the connections between different topics may help them to start thinking in a synthetic way (OECD, 2020[6]). For example, environmental and sustainability education is a commonly articulated cross-curricular theme as part of the general goals of education and countries such as New Zealand have introduced new subjects specifically devoted to this subject.

Another simple technique is to move away from right/wrong questions wherever possible, giving students an open-ended prompt and encouraging them to offer a variety of solutions. Groupwork can also be an effective vehicle for creative thinking and helps students to develop a broader set of social emotional skills, too. In the 21st century, it is those relational aspects of teaching – mentorship, coaching, guidance – that will distinguish the most effective and successful teachers from their peers (OECD, 2019[7]).

Korea has, since 2009, integrated a curriculum that not only enhances subject-based learning but also allocates nearly 10% of total school time to creative projects and activities (Vincent-Lancrin, 2013[8]) This strategic approach aims to nurture a diverse set of value creation skills among students, including creativity in learning, communication and collaboration. Similarly, Singapore's educational framework, under its "Desired Outcomes of Education," places a significant focus on developing critical and inventive thinking alongside social and emotional competencies. By the conclusion of secondary education, Singaporean students are expected to emerge as resilient, innovative, and enterprising individuals. They are also trained to think critically and communicate their ideas effectively and persuasively, preparing them to tackle challenges and thrive in an ever-evolving global landscape.

Singing with Friends is a weekly initiative where 16-17 year-old students from the United World College of South East Asia (UWCSEA) collaborate with young adults from the Down Syndrome Association of Singapore (DSA). Launched in 2014, this programme utilises music to foster connections and celebrate song. Each session involves the UWCSEA students leading activities, including games and singing, with children who have Down Syndrome. The aim is to boost the confidence, musical abilities and communication skills of the children with Down Syndrome while simultaneously teaching the UWC students the importance of listening to and learning from the experiences of others.

In Ontario, Canada, the Thames Valley District School Board's Rethink Secondary Learning project aims to prepare future ready learners. Its approach incorporates hands-on, experiential learning tailored to student interests, applying knowledge to real-life situations. A key initiative is the Greenhouse Academy, a 60 000-square-foot student-run learning space where students gain practical experience managing a greenhouse business. They tackle real-world problems, from choosing plants and designing layouts to budgeting and collaborating with local industries for resources like irrigation. Under teacher and staff mentorship, students learn to navigate business challenges, enhancing their independence and teamwork skills, and contributing value to their community and the business itself.

Creative thinking is recognized globally as a critical skill for the future, with education systems worldwide acknowledging its importance in curricula. Yet, simply revising curricula isn't enough to guarantee the development of creative thinking skills in students. A coherent approach is needed, ensuring that curricula, teacher training, and assessment methods are all aligned to foster an educational environment that truly supports and nurtures creativity.

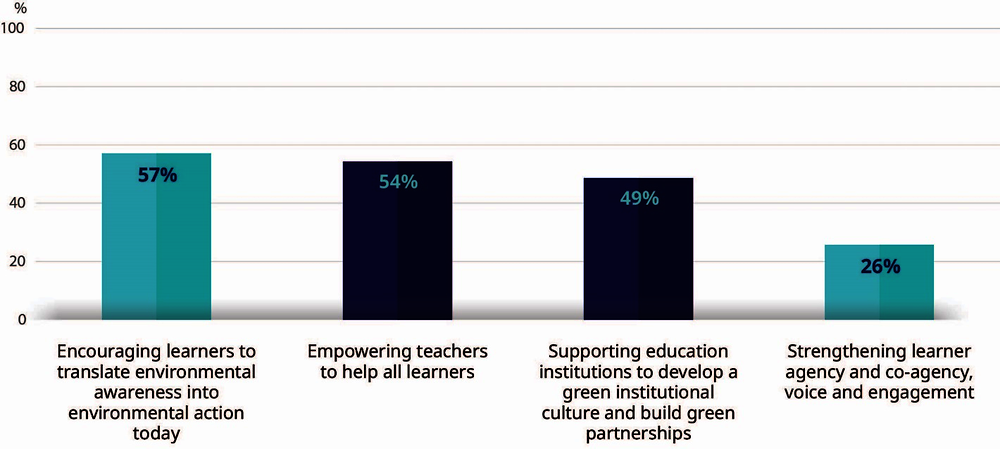

In 2018, only one-third of OECD students were environmentally active. One of the most effective ways to turn awareness into action is by supporting the agency of young people, yet only a quarter of education systems prioritise strengthening learner agency and co-agency for the transition to greener and fairer societies. Shifting from teaching to mentoring, and creating a classroom culture that encourages student voice, exploration and responsibility can provide a fertile ground for the development of student agency (defined in the context of the OECD Learning Compass 2030 as the capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change) (OECD, 2019[7]).

Speaking at last year’s UN climate conference (COP28), former Irish President Mary Robinson said that “people in powerful positions must be prepared to step aside to make space for children and youth” (Robinson, 2023[10]). Children and young people, she argued, have solutions to offer with regards to climate change mitigation and adaptation and it is only by enabling them to shape their own future that we will be able to unleash their potential.

Student agency plays an important role in addressing climate change. Students who have the capacity to take responsibility for their actions develop a strong moral compass that guides considered reflection, work with others and respect for the planet. It also helps in the classroom. Students who exercise agency are better able to navigate by themselves through unfamiliar contexts and find their direction in a meaningful and responsible way.

Climate change isn’t the only unprecedented territory that young people find themselves in today: artificial intelligence, the fracturing of the global political order and economic insecurity all require agency both as a goal and as a process to help learners navigate an ever-changing landscape (Stenalt and Lassesen, 2021[11])

When students actively participate in shaping their education by selecting what and how they learn, they can exhibit increased motivation and are more inclined to set specific learning objectives (OECD, 2019[12]). This can not only enhance their enthusiasm for learning but also equip them with the essential ability to self-educate—a skill of lifelong value. This agency is applicable across various domains, including ethical decision-making, social interactions, economic understanding, and creative work. For instance, exercising moral agency is critical for students to make decisions that acknowledge the rights and needs of others.

While a robust sense of agency aids students in achieving long-term objectives and overcoming challenges, it is imperative that they possess fundamental cognitive, social, and emotional skills. These skills are crucial for applying their agency effectively, benefiting both their personal development and society at large.

When it comes to climate change, most students are aware of the issues. In 2018, 79% of students across the 37 OECD countries in that year’s PISA study said that they knew about the topic of climate change and global warming. But this does not necessarily translate into action. That same study found that only one-third of OECD students were environmentally active. And this has a socioeconomic dimension as well: the share of students displaying pro-environmental attitudes was 23 percentage points higher among economically advantaged students than disadvantaged students (OECD, 2022[13]) These findings are especially concerning given that while disadvantaged students are at greater environmental risk than their advantaged counterparts, they are currently less well equipped to take action to mitigate these risks.

The citizen-led MolenGeek initiative, which aims to provide an opportunity for employment, business creation or career building to anyone in the historically-deprived Molenbeek area of Belgium, regardless of their identity, doesn’t rely on entry exams or any prerequisites. Recognising that these might exclude the most disadvantaged students, many of whom will have faced challenges with formal qualifications or testing, MolenGeek instead requires all entrants to develop their own project within the first six months of joining. This fosters the agency of students, empowering them to create their own roadmap to success while encouraging their creativity and problem-solving skills.

The educational environment is an important crucible for student agency. Teachers can stoke the fires of student agency by creating a classroom culture that encourages risk-taking and values each student's voice. Teachers can also model and promote a growth mindset, providing opportunities for students to make choices about their learning. Helping students to become aware of their own learning processes can enable them to set goals, monitor progress and adjust their strategies. Finally, authentic learning experiences that connect to students’ lives and interests also play a crucial role.

To inculcate agency in students, teachers themselves need agency. This includes the skills to observe students' learning processes, make decisions based on these observations, implement actions, evaluate the outcomes, and learn from this entire cycle. A key aspect of this professional autonomy is the capability to defend classroom methods with a foundation in theoretical knowledge and critical reflection, along with a clear understanding of one's motivations and values in making decisions.

Norway uses mentors to help guide student teachers in planning and reflecting on teaching practices. These mentors are also responsible for aiding the student teachers in translating their theoretical knowledge gained at university into effective classroom teaching, as well as in supporting them to articulate and reflect upon their teaching decisions.

The Montessori system is a good example of a school system centred on students’ inquisitiveness and problem solving around activity-based learning and play. The role of the teacher in this context is to prepare a suitable environment for these activities and to adapt this environment to the students’ interests and needs as he or she grows.

Other education systems adopt similar philosophies of student-centred learning. Finland’s HEI schools, for instance, are “grounded in the belief that early childhood is a time when children should be free to explore their interests and discover new things” (HEI Schools, 2020[14]) As such, they integrate individualised learning that accounts for the different developmental phases, personality and attributes of each child. In doing so, they aim to build the confidence and self-determination of students: two essential characteristics of agency.

In British Columbia, Canada, completing a capstone project or a culminating activity is a necessary part of graduating from secondary school. This project is undertaken at the conclusion of higher secondary education as an innovative alternative to traditional exams in specific subjects. The project's format is a collaborative effort among the student, their mentor, and a teacher or supervisor, drawing insights from the student's Career Education course, mentorship experiences, and self-assessment documentation.

The capstone project aims to empower students to actively participate in demonstrating their knowledge, take responsibility, and work collaboratively, fostering their growth and social and emotional skills. The Ministry of Education and Childcare has seen benefits from these projects, such as enhanced academic performance in the final year of secondary school, heightened student motivation and engagement, more defined goals for after graduation and future careers and improved confidence and self-awareness.

A case from Japan illustrates the potential of pairing learning and practice. In 2015, the country changed the laws to lower the voting age from 20 to 18, which led to a revision of the national curriculum standard for high schools to create a new civics subject, call “Ko-kyou” (OECD, 2020[15]). Ko-kyou aims to not only teach students about democratic processes, it also seeks to develop the competencies to make decisions fairly, based on an analysis of facts and in consideration of perspectives. It includes discussions and work towards consensus building and social participation and the use of ideas that contribute to decision making, good judgment and basic public principles to solve real problems in society.

By integrating approaches that prioritize hands-on activities, real-world problem solving, and individualized learning paths, educators can foster environments that promote autonomy, creativity, and critical thinking. Such a shift requires a re-evaluation of curricular designs, teaching methods, and assessment practices to ensure they are flexible and responsive to students' diverse learning styles and paces. Professional development programmes can play a crucial role in equipping teachers with the skills and mindset needed to implement these changes effectively.

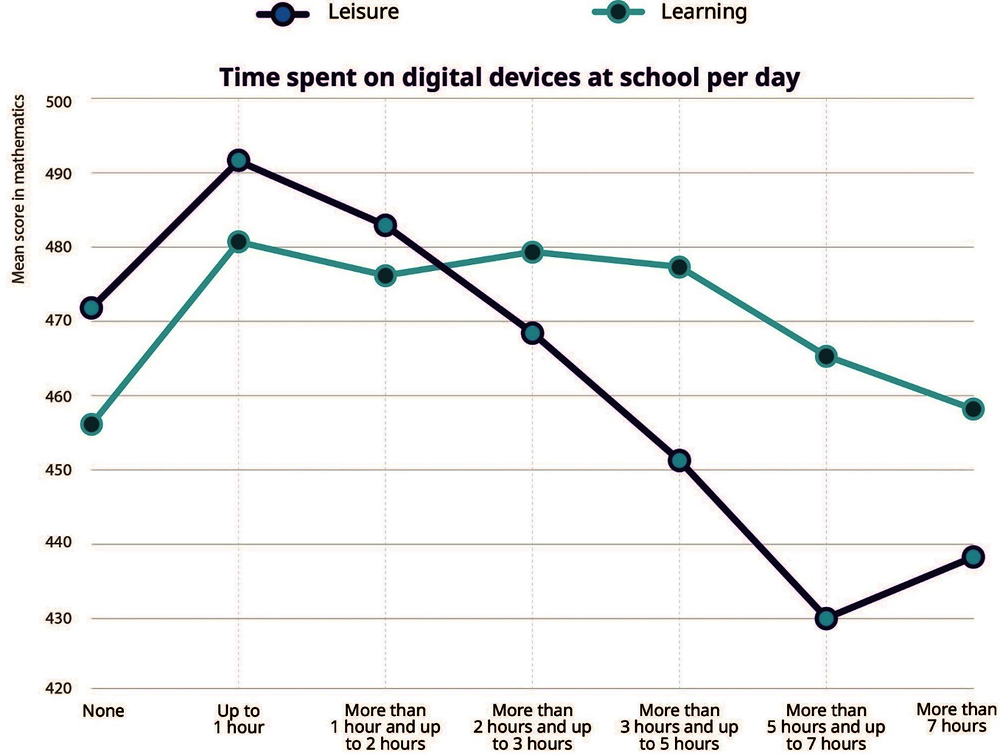

Even in schools with phone bans, 29% of students on average across the OECD reported using smartphones several times a day, with 21% using one every day or almost every day at school. The more students use digital devices for leisure during school hours, the lower their math scores. Even if students aren’t using their own phones, they become distracted by their peers: 65% of students on average across OECD countries report being distracted by digital devices in at least some math lessons.

With more of our daily activities happening online, digital technology is transforming how we gather and apply knowledge. The digital skills workers learn are vital for adapting to a job market that is becoming transformed by digitisation, automation and artificial intelligence. But beyond employment, these skills are instrumental in closing social disparities (OECD, 2019[12]). They offer a bridge for people from various backgrounds to access opportunities and resources that were previously out of reach. While mastering complex technology isn't mandatory for everyone, acquiring basic digital skills is crucial for everyone looking to thrive in the digital age, ensuring broader participation and reducing inequality.

The good news, as any parent of a teenager knows, is that most young people are acquiring digital skills at a pace that far outstrips their parents. In fact, research has shown that parents on average have higher digital literacy skills than their children only until the age of 12 (Byrne et al., 2016[17]) By 15, most children have surpassed their parents. Raised in an era where digital devices are ubiquitous, these teenagers navigate the online world with a technical ease that comes from lifelong exposure.

But as the digital environment comes to encompass more and more of the lives of young people, so do the threats. Evidence is mounting that the quality and frequency of social and emotional interaction among youth is declining, cyberbullying, exposure to violent and inappropriate content is on the rise, and many are becoming addicted to their devices (Winther et al., 2023[18]).

Used for learning, digital devices have the potential to enhance learning outcomes. The latest PISA data show that students who spent up to one hour per day on digital devices for learning activities in school scored 14 points higher on average in mathematics than students who spent no time. As artificial intelligence advances, these benefits may multiply. AI has the potential to provide more personalized learning experiences, tailoring instructions to the needs and interests of individual learners (OECD, 2023[19]) Augmented and virtual reality may allow learners, especially those in vocational education and training programmes, to develop practice-oriented skills in a safe environment which mimics the workplace.

Access to ICT infrastructure in schools is widespread in most OECD countries: by 2015, almost 9 in 10 students had access to computers in schools. Significant numbers of students remain on the other side of the digital divide, though. For example, in Jordan, Morocco, the Philippines, the Palestinian Authority and Thailand, only half or less of students felt confident or very confident about using a video communication programme. It’s important that we close the gap (OECD, 2023[19]).

But digital skill acquisition is only part of the story. For students to thrive in a digital world, they need to acquire the attitudes and values, such as self-discipline, self-motivation and critical thinking, to help them navigate what is often a confusing, alienating and even hostile online environment. On this front, many education systems are failing.

According to PISA, on average across OECD countries, 45% of students reported feeling nervous or anxious if their phones were not near them. This has effects that go beyond the well-being of young people: students who felt this way scored 9 points less in PISA tests than the average, across the OECD. They were also less satisfied with their lives, had less emotional control and were less resistant to stress.

65% of students reporting being distracted by using digital devices in at least some maths lessons. Digital distraction is not merely an inconvenience; it is associated with poorer learning outcomes, according to PISA. Students who report being distracted by peers using digital devices in some, most or every maths class score significantly lower in maths tests, equivalent to three-quarters of a year’s worth of education. The rates in high-performing systems are far lower: just 18% of students in Japan and 32% in Korea reported this level of distraction.

Studies have shown that students who struggle academically often find it difficult to stay motivated with remote learning. Unlike their peers from wealthier families, they may lack the necessary support system to facilitate their education from a distance. As PISA 2022 found, more disadvantaged students than advantaged students reported that they had frequent problems with remote learning during COVID-19-related school closures. Addressing these challenges is critical to ensure that all students can keep up with their studies and maintain a connection with their schools during periods of remote learning.

Teachers have an important role in helping students acquire healthy online values and behaviours, and in helping them to navigate an ever-more complex digital world. This is borne out by our PISA data, which showed that in education systems where students reported that their teachers were available when they needed help, students tended to be more confident that they could learn independently and remotely if their school has to close again in the future. On average across OECD countries, students who had a more positive experience with remote learning – for example, students who agreed or strongly agreed that their teachers were available when they needed help – scored higher in mathematics and reported feeling more confident about learning independently if their school has to close again in the future.

Integrating home-based learning (HBL) as part of the regular school programme can also help students become self-directed, independent learners. Singapore has been offering around two HBL days for students each month, where schools determine the subjects and topics covered on HBL days and customise the support for student-initiated learning based on their students’ interests and needs. Critically, students who require additional learning support or who do not have a home environment that is conducive to learning can return to school on HBL Days where they will be supervised by school personnel but will still have the opportunity to learn and organise their schedule independently.

When designing digital learning programmes, it’s also important to remember that the practices of the classroom cannot simply be translated to the digital space. Simply placing a camera at the back of a classroom and recording a livestream of your lecture isn’t likely to hold the attention of your students for very long – especially those that are already struggling. In fact, one study found that lower ability students who viewed livestreams of lectures performed approximately two percentage points lower than in the classroom setting, while those at the top of the ability distribution saw a two-and-a-half point gain (Hague, 2024[20]).

Instead, online learning programmes that empower students to be self-directed, to collectively problem solve with their peers and to investigate global issues that matter to them may provide better learning outcomes while also fostering the kind of online value and behaviours that future-ready learners need. Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Global Scholars programme is designed to let students create, share and discuss original content in virtual discussion boards with peers from around the world (Tiven et al., 2018[21]) Instead of being graded on how well they can memorise facts, they are expected to complete assignments, post original work, and engage with fellow students.

Many teachers listed digital infrastructure and connectivity, as well as teachers and school leaders’ positive attitudes towards digital tools as necessary prerequisites for digital uptake in schools. Time is also an important resource that both students and teachers need to be able to explore and familiarise themselves with new digital tools. Additionally, teachers agreed that teacher training should prepare them to understand the underlying learning frameworks of these tools and give them indications on how to use them in effective ways (OECD, 2023[19]).

Future-ready learners are digital learners but this requires more than merely acquiring technical skills; it involves cultivating healthy digital values and behaviours. Navigating the digital landscape with integrity, responsibility, and critical thinking is as crucial as mastering digital tools. Therefore, policy and educational frameworks should be designed to support this comprehensive view of digital literacy. By retaining a central crucial role for teachers within the digital landscape, integrating remote learning into everyday lessons in a structure and supported way, and shaping digital learning in such a way that empowers and motivates learners, educators can prepare students not just for the workforce, but for a life lived online.

In an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world, students need to be able to balance contradictory or seemingly incompatible logics and demands, and become comfortable with complexity and ambiguity. This requires a range of skills, including systems thinking and social and emotional skills. Yet most 15-year-olds report lower social and emotional skills nearly across all measures. The use of simulation exercises, peer learning and encouraging autonomy among students all play a role in fostering the skills needed to manage uncertainty.

This moment in history is one of profound uncertainty, where competing ideas, ways of living and even fundamental matters of science and fact are swirling around an information landscape whose complexity and pace of change is outstripping our ability to navigate it. To adapt to complexity and uncertainty and be able to help shape a better future, every learner needs to be equipped with certain transformative competencies. These specific competencies enable students to develop and reflect on their own perspective, and they are necessary for learning how to shape and contribute to a changing world. Creating new value, taking responsibility, and reconciling tensions, dilemmas, trade-offs and contradictions are all examples of such competencies (OECD, 2020[22]).

These skills matter in the classroom. By holding conflicting ideas in tension, students can acquire a deeper understanding of opposing positions, develop arguments to support their own position, and find solutions to dilemmas and conflicts (OECD, 2019[23]) For example, a systems thinking approach, where students develop an understanding of how complex systems behave by studying real-life examples, such as the water-energy-food nexus or the energy system, can help students see various opportunities for making change within a system.

These skills matter in the workplace, too. Google’s Project Oxygen programme, running since 2008, seeks to determine which skills are key to the performance of its best managers. It has consistently found that collaboration, self-management, communication and encouragement are in top place. In fact, only one of the top 10 skills is technical.

School is where we can learn and sharpen these skills. In many ways, schools are like giant petri dishes of social emotional learning, where students interact with their peers in formative ways. But teaching is as important. The effective teaching of social and emotional skills can positively affect students' success in school. Skills such as problem-solving, self-regulation, impulse control and empathy can help improve academic outcomes and reduce negative social behaviours such as bullying. This can lead to a virtuous circle: when a student believes in herself and is able to exercise self-control, her performance increases (Steponavičius, Gress-Wright and Linzarini, 2023[24]). This in turn leads to further self-belief and so on.

And this is borne out by the data. A 2006 study of the 1979 US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth found that an increase in the measure of social and emotional skills – from the 25th to the 75th percentile of its distribution – was associated with a nearly 25 percentage point increase in the probability of being a four-year college graduate at age 30 (OECD, 2021[25]). The OECD’s own PISA data show that in 2022, on average across OECD countries, students that were curious or persistent scored around 11 points higher in math. Students who were better able to control their emotions or were stress resistant also outperformed their peers by around six points.

The good news is that many schools are teaching social and emotional skills. A 2019 study of American schools by the RAND Corporation found that nearly four in five principals listed the promotion of students’ social and emotional skills as the top priority or among the school’s top priority (Hamilton, Doss and Steiner, 2019[26]). This was especially true for schools in lower-income areas. The bad news is that on many measures, young people seem to be struggling with social and emotional skill development.

OECD survey data on social and emotional skills show that 15-year-olds in all participating cities demonstrated lower social and emotional skills than 10-year-olds, and this is especially true for optimism, trust, energy and sociability. Developmental psychology provides some explanations for that, but on the other, these effects may be worsened by the often-stifling effect of secondary school on creativity and self-expression.

And there are other warning signs. In 2022 one in five students reported being bullied at least a few times a month, on average across OECD countries, with 8% being bullied regularly. For the victims of bullies, the consequences on academic performance can be severe. Students who are lonely, unhappy or frightened are unlikely to excel in a classroom. In systems that have lower incidences of bullying, especially among disadvantaged students, educational performance is better. It is important not to forget that bullies themselves are also often facing social and emotional issues and require support as well.

Most people aren't taught systems thinking in their education, making it hard for them to tackle systemic issues that impact their lives. To help teachers improve their skills in systems analysis and thinking, resources can be created to incorporate these topics into their teaching (OECD, 2023[4]). These could range from comprehensive curricula for university, school, and adult education to modular teaching aids that teachers can adapt to their needs, including specific course materials. Practical tools for teachers and their students, such as qualitative methods, simulation games, and even quantitative methods, can provide further benefit. Encouraging teachers to explore systems thinking can be achieved by offering broad introductions that highlight its relevance to their teaching activities.

In Latvia, students enrolled in a media theory class are encouraged to reflect on how the media landscape in the country is defined by the system of donor-political relationships (World Economic Forum, 2023[27]) They practice this skill by mapping all donations given to various political parties and analysing the political agendas of the respective parties. This helps them better understand the stated beliefs and values of political parties running for election and visualise how a complex interconnection of relationships influences the political landscape, in turn helping students become more informed civic actors and providing them with the knowledge to enact positive change in their communities.

To effectively introduce social-emotional learning in classrooms, teachers must first master these skills themselves. When teachers model and teach social and emotional competencies, such as self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision-making, they create a supportive learning environment that can improve academic outcomes. They also contribute to a positive classroom climate where students feel safe, supported, and engaged. This is conducive to learning and can reduce behavioural problems such as bullying.

For example, Peru’s Escuela Amiga model offered teachers and principals a comprehensive year-long course, facilitated by psychologists, blending classroom instruction with practical activities such as role-playing and peer support (Guerra, Modecki and Cunningham, 2014[28]) Participants, hailing from underserved communities, emerged with certificates and notably transformed their classrooms into calmer, more engaging spaces, employing innovative teaching methods. Beyond professional growth, teachers reported significant personal gains, underscoring the critical role of supportive learning environments in enhancing children's skill development.

To address the social and emotional issues facing young people, educators also need to better understand them. New Zealand deploys the What About Me? Survey, targeting students at upper secondary level, and uses the data and insights to inform decisions and policies which support well-being in schools around a range of dimensions, including physical, spiritual, family and mental health (OECD, 2023[4]). In Finland, the educational system gathers information through the Youth Barometer, an annual survey of the values and attitudes of 15 to 29-year-olds in the country. By contributing to an understanding of young people’s social and emotional context, the Youth Barometer provides educational institutions with an invaluable source of data to shape social and emotional learning.

Pedagogical methods can be adapted to utilize social-emotional skills for academic learning. Korea has shifted towards embedding social and emotional learning into education, notably through the 2009 introduction of Creative Experiential Learning (CEL) into curriculums (OECD, 2022[29]) CEL encourages students to engage in extracurricular activities that foster creative thinking, autonomy, and hands-on learning across diverse areas such as multiculturalism, environmental sustainability, and financial education. By participating in self-regulated, club, volunteering, and career exploration activities, students enhance vital skills like creativity, self-regulation and cooperation, building a stronger sense of community and personal identity.

Future ready learners need strong socio-emotional skills. To build those skills, teachers need to act as much more than only traditional conduits of knowledge: they must serve as role models, guides and facilitators of a supportive learning environment. Policymakers have a role to play in ensuring teachers have the required training and support and by equipping them with the knowledge and data to better understand the world that their students inhabit. In doing so, we can enhance students' academic performance, improve relationships and prepare them for the challenges of the future.