Chapter 6. Tax policy and incentives in Egypt

This chapter provides an overview of Egypt’s tax system, including recent reforms, and an assessment of the country’s investment incentives regime. It provides an overview of existing incentives, their implications for the tax administration and proposes options to ensure that tax incentives achieve the government’s policy goals in a cost-effective manner. The chapter also looks at tax governance and transparency issues.

Summary and policy recommendations

Tax policy and administration are important components of an investment climate. Governments worldwide use tax incentives to achieve certain outcomes, whether more investment overall or greater flows to certain sectors, activities or regions. At the same time, corporate income taxes are often an important source of fiscal revenue for governments, particularly in emerging economies which can in turn contribute to improving other aspects of the investment environment such as through public spending on infrastructure or health and education. Sound tax policy requires effective coordination across ministries and agencies and at different levels of government, transparency and consistency in its application and regular monitoring and review of its effectiveness. Tax expenditure reporting should be publicly available and subject to parliamentary oversight. Tax policies that create an uneven playing field for business or that are uneven in their application create uncertainty for investors which might negate any positive outcomes which the policy was intended to achieve in the first place.

The Egyptian government has made substantial improvements in its tax policy in recent years. The 2017 Investment Law includes many positive changes, including limiting corporate income tax holidays to free zone (FZ) companies. Similarly, the 2015 amendment of the Law on Economic Zones of Special Nature no longer includes reduced corporate and income taxes for projects inside special economic zones. The government also has an extensive array of measures to protect the domestic tax base from cross-border tax minimisation techniques used by multinational enterprises (MNEs). The Egyptian Ministry of Finance and the OECD have recently launched an EU-funded project to strengthen domestic resource mobilisation in Egypt. Project elements include guidance on enhancing tax transparency, implementing international standards on exchange of information, capacity building to assist authorities in addressing aggressive tax planning by MNEs, and compiling internationally comparable revenue statistics.

Incentives offered to companies in FZs contribute to revenue leakage when commodities (imported and domestic supplies) enter zones tax-free. They also introduce distortions and hamper productivity growth when FZ companies enjoy competitive advantages focus on the domestic market, as shown by recent figures presented in Chapter 5. To limit revenue leakage, the authorities are encouraged to prescribe and publish lists of commodity inputs currently eligible for customs duty and value added tax (VAT) exemptions. They could also consider mechanisms to monitor firms’ export performance until CIT holidays are phased-out in zones.1.

To ensure consistency with overall tax policy and to strengthen accountability, the government is encouraged to consolidate tax incentive legislation and tax legislation and assign to the Ministry of Finance (MOF) primary responsibility to introduce tax incentive legislation. The report recommends that the tasks of monitoring compliance with tax incentives be assigned to the Egyptian Tax Authority (ETA), and that strict penalty regimes be exercised. The current project to switch to a fully electronic data management platform in the tax system is strongly supported.

Guidance on tax policy and tax incentive design

Recommendations on tax policy

Target the tax deduction for undocumented expenses to small businesses

Increase the withholding tax rate on dividends paid by resident companies to resident shareholders and eliminate the EGP 10 000 dividend exemption

Eliminate the personal tax exemption for dividends paid by FZ companies.

Eliminate the corporate tax exemption for interest on bonds issued by listed companies

Limit the exemption for pension income

Supplement or replace the (4:1) thin-capitalisation rule with an interest deduction limitation rule that follows the recommendations of BEPS Action 4

Discontinue the statutory non-resident withholding tax exemption for interest

Recommendations on tax incentive design

Target the 30% expensing of capital costs to new investment expenditure

Prescribe conditions and list commodity inputs eligible for customs duty exemption

Redesign targeting criteria and clarify terms to minimise discretion in determining eligibility

Revise the base of the investment tax allowance to investment expenditure on tangible capital (with a ‘first-in-use’ rule)

Recommendations on tax incentives for Free Zone projects

No longer provide FZ projects with a CIT holiday (grandfather existing projects)

Extend the investment tax allowance to include investments by FZ companies

Ensure electronic tracking of goods entering and exiting FZs

Monitor very closely export performance of public FZ projects as long as CIT holidays exist

Align fees on sales by public FZ projects to the domestic market with those of private FZs (i.e. increase them from 1% of sales to 2%).

Guidance on governance of tax incentives

Recommendations on introducing tax incentive legislation

Consolidate tax incentive legislation and tax legislation

Reduce discretion of officials in providing tax incentive relief

Assign to the MOF sole authority to introduce tax and tax incentive legislation

Strengthen capacity of MOF staff for tax analysis

Regularise data collection and ensure MOF access to anonymised tax data

Recommendations on monitoring tax incentives

Assign to the ETA responsibility to monitor compliance with tax incentives

Ensure electronic tracking of goods entering and exiting FZs

Apply strict penalty regimes for non-compliance with tax incentive laws and regulations

Recommendations on reporting of tax incentives

Prepare tax expenditure reports to accompany budget documents2

Prepare reports on purchases, sales and tax relief for FZ companies

Prepare reports on cost-benefit analysis of main tax incentives

Tax system review and scope for revenue mobilisation

Tax revenues in Egypt have been relatively stable over the past decade but remain below many peers in the region and elsewhere as a percentage of GDP. The government will need to raise revenues over time for public spending on health, education, infrastructure and other areas which, among other benefits, will contribute to improvements in the business climate. Revenue mobilisation will require efforts on several fronts, not least concerning income, property and consumption taxes, as well as on improving tax administration.3 This section focuses mainly on corporate taxation which has the most direct impact on investor behaviour and on the broader social returns from economic activity. The discussion which follows looks at how taxes on capital are applied and at how Egypt protects its tax base against profit shifting by investors.

Domestic taxation

Table 6.1 reports the tax mix in Egypt in fiscal year 2016/17, including the recent introduction of VAT showing tax revenues in millions of Egyptian pounds and as a percentage of GDP. One notable feature is the relatively low contribution of personal income tax (PIT), due in part to the importance of the informal market and in part to narrow rules governing the taxation of investment returns at the individual level (as noted below).

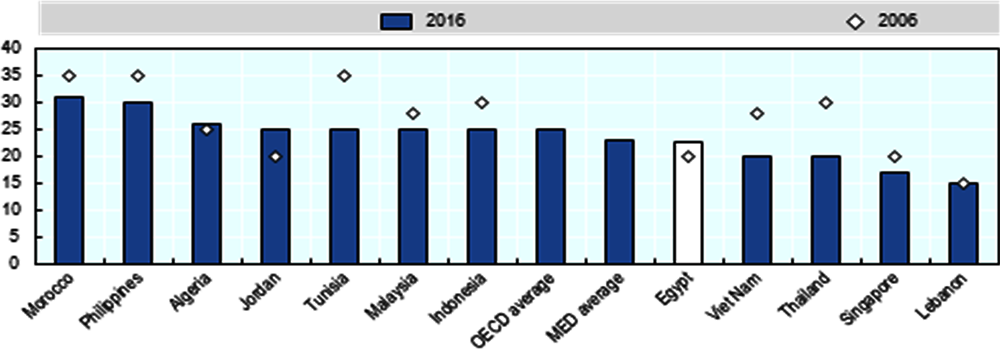

The corporate tax-to-GDP ratio is not low by international comparison but has declined sharply from 6% over the past decade and may decline further over time, depending on the path of corporate tax policies, administration and governance going forward. The statutory corporate income tax (CIT) rate is moderate at 22.5%, the second lowest rate in the Mediterranean region after Lebanon (Figure 6.1).4 The CIT base is nevertheless at risk, depending on how broadly the FZ regime is applied (number and size of firms covered), how successful authorities are in protecting the CIT base from profit stripping, and other factors.

Table 6.2 provides a summary of corporate income tax provisions in Egypt. Ordinary business losses may be carried forward for up to five years for both listed and non-listed companies, with few exceptions.5

The tax depreciation system is attractive in its simplicity, based on four asset classes. Buildings and intangible assets are depreciated on a straight-line basis at 5% and 10%, respectively. Computer devices and information-technology assets are depreciated on a declining-balance basis at 50%. Other depreciable assets are depreciated at a 25% declining-balance rate.

Under the Investment Law No. 17 of 2017, businesses may claim an immediate 30% deduction on the machinery and equipment used in production (with 70% of investment costs depreciated according to the above-noted tax deprecation rules). Presumably, this acceleration of depreciation, through immediate expensing of 30% of capital costs, applies to the acquisition of both new and used capital goods. To improve efficiency, the expensing should be targeted at new (rather than pre-existing) capital.6 This could be accomplished using a ‘first-in-use’ rule that limits the expensing to new capital used in production.

Egypt is currently planning to implement e-invoicing. One provision that should be reviewed, to assess the implications for income tax revenues, is a general deduction for undocumented business expenses equal to 7% of documented general and administrative expenses (including wages). This provision, which applies to (closely-held) private corporations and unincorporated businesses, may have been understandable in years past, when provided to micro-businesses challenged by tasks of record-keeping. But given current low costs of keeping digital records on expenses (e.g., as required for VAT purposes), this provision appears to be dated and offering poorly targeted tax relief. At a minimum, it would seem appropriate to target the provision (if retained) to small firms that are below the VAT registration threshold.

The personal income tax exemption for dividends on shares in FZ companies is inefficient,7 providing investors with windfall gains on their returns, as opposed to lower costs of finance for FZ firms. Moreover, to the extent the PIT exemption lowers the rate of return shareholders expect on their investments in FZ companies, this relief tends to favour FZ companies relative to companies outside FZs. As noted earlier, the multiple forms of tax relief targeted at FZ companies may be limiting productivity growth and wages in the economy and should be scaled back.

Tax incentives for investment

Many governments offer incentives in one form or another to achieve certain outcomes related to the overall level of investment or investment in targeted sectors or regions, or to encourage certain activities on the part of businesses such as training or the development of local suppliers. Incentives can take many forms but are usually either a tax holiday or an investment tax allowance or tax credit. Incentives in Egypt have undergone a major reform with the introduction of Investment Law No. 72 in 2017.8 The current system of tax incentives is reviewed below, with a particular focus on FZ incentives in the final section.

General, special and additional incentives

Tax incentives are included in Income Tax Law No. 91 of 2005 and Investment Law No. 72 (INVL). Tax incentives under the INVL include general incentives, special incentives and additional incentives, and varied incentives across a number of categories of zones. Law No. 83/2002 on “Economic Zones of Special Nature Law”, amended by Law No. 27/2015, does not provide for corporate income tax incentives.

a) CIT incentives (Income Tax Law)

The Income Tax Law provides accelerated depreciation, whereby companies can immediately expense 30% of capital costs and depreciate the remaining 70% by applying standard tax depreciation rules. As noted earlier, the 30% expensing provision should be targeted at new (rather than pre-existing) capital, to improve efficiency.

b) General incentives (Article 10 of INVL)

General incentives include a uniform customs duty at 2% on imports of machinery and equipment, and exemption from stamp duty for five years. Furthermore, a customs duty exemption is provided to manufacturing projects for imported items brought into the country for temporary use, although ‘temporary’ is not defined in the law or Executive Regulations. The CEO of the General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI) holds the power to grant certificates for general incentives.9 Presumably, GAFI determines lists of duty-free goods and how the term ‘temporary’ is to be applied, on a case-by-case basis.

c) Special incentives (Article 11 of INVL)

Special incentives include an investment tax allowance (ITA) deductible against taxable profits, for qualifying investments. The ITA rate differs between Sector A-type and Sector B-type investments. The ITA rate is 50% for Sector A investments, which target geographic areas designated in an ‘investment map’ determined by Executive Regulations.10 The INVL regulations specify that Sector A includes investments in the Economic Zone of the Suez Canal, the Economic Zone of the Golden Triangle, and “areas in most need for development as determined by the Council of Ministers”.11

A reduced ITA rate of 30% applies to Sector B investments which targets certain types of investments in all other locations within Egypt. The list of investment types that qualify (Box 6.1) includes targeting by i) business size (small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)), ii) inputs used in production (labour-intensive projects, and projects using new and renewable energy), iii) percentage of production that is exported, iv) strategic importance of production, and v) type of output (projects producing new and renewable energy, and projects in a listed set of industrial sectors).

Sector B-type of investments that qualify for the 30% ITA are investments in:

SMEs

Labour-intensive projects, as set out in Executive Regulations

Projects depending on or producing new and renewable energy

Projects exporting no less than 10% of products

National and strategic projects listed under resolution of the Supreme Council of Investment

Electricity generation and distribution projects listed by a decree of the Prime Minister

Tourism projects listed under resolution of the SCI

Automotive manufacturing and the supplying industries thereof

Wood, furniture, printing, packaging and chemical industries

Antibiotics, tumour drugs and cosmetic industries

Food, agricultural crops and agricultural waste recycling industries

Engineering, metallurgical, textile and leather industries

Sector-B investments include investments in labour-intensive projects. Executive Regulations explain that a project is considered labour-intensive if at least 500 Egyptian workers are employed, and wage costs exceed 30% of total operating costs. The CEO of GAFI (or a representative) has the power to grant certificates for special incentives.12 Presumably, GAFI rules on whether targeting criteria are satisfied. The prime minister and Supreme Council of Investment (SCI) also have discretionary authority to determine eligibility.13

For both sector A and sector B-type investments, the ITA is a one-time deduction, based on investment cost measured on the date when economic activity begins and capped so as not to exceed 80% of paid-up capital. The ITA is available within the first seven years following the commencement of economic activity and is deducted against a company’s total taxable profit (and not ring-fenced to be deducted against the revenues of a single investment project).14

d) Additional incentives (Article 13 of INVL)

The Council of Ministers may grant additional (non-tax) incentives to projects entitled to special incentives (namely ITAs).15 In order to assess the rationale for and possible effects of the ITA on investment, a review of the additional incentives is required. Additional incentives include:16

Permission to establish special customs ports of entry, for imports or exports

A grant covering all or part of the expenses incurred in providing utilities to a project

A grant covering part of expenses of providing technical training to personnel

A grant of 50% of the value of land (100% for strategic projects) used for industrial projects, if production commences within two years of the date of transfer of land to the project.

The Executive Regulations (Article 12) explain that projects eligible for additional incentives must satisfy any (one or more) of the following conditions:

1. Egypt should be a main country for producing its products. Also, the main country of the company’s products should be Egypt.

2. The company shall rely on foreign funds (funds transferred from abroad) for financing.

3. A minimum of 50% of products are exported.17

4. Project activities include the transfer of technologies to Egypt and ‘exert efforts to support their feeding industries’ (to confirm that this means purchasing domestic inputs to production).

5. The project uses local content (domestic inputs) in production, with a minimum local content of 50% of raw materials and (other) production requirements.

6. The company’s activity should be based on the output of research projects in Egypt.

The conditions required for eligibility, as specified, are generally not demanding and investors need only satisfy one of them. For example, it would appear (without further guidance) that the financing requirement (condition 2) can be met in cases where domestic funds are invested through offshore conduits.

Tax incentives for investment in zones

There are multiple zone designations applied in Egypt, as described extensively in Chapter five. This chapter focuses on public and private FZs. Two other zones (not described in detail here) which were created by the new investment law (INVL) are investment and technological zones. Incentives offered for investment in these latter two zones are as follows.

Incentives for investment zone projects: Projects located in investment zones, established by the prime minister, are eligible for general incentives, special incentives and additional incentives (as described above).18 Each investment zone is governed by a board of directors which approves projects, subject to the approval GAFI,19 and sets rules and requirements.

Incentives for technological zone projects: Projects specialised in communications and information technology located in technological zones, established by the prime minister, are eligible for special incentives (as described above)20 and are exempt from customs duties on machinery and equipment.21 Each technological zone is governed by a board of directors, which approves investment projects, and sets rules and requirements.

The most extensive tax incentives are available to investment projects in FZs. A FZ established for a single large-scale project is designated as a private FZ. Other FZs are designated as public FZs. Private and public FZs (and their shareholders) enjoy the same tax incentives. Fees and taxes on domestic sales differ between the two. Certain business activities are denied registration in FZs:22 oil processing; natural gas processing, liquidation, transport; energy-intensive industries; fertiliser industries; iron/steel industries; liquor and alcohol industries; guns, ammunitions and explosive industries; and other industries of national security interest. The INVL and Executive Regulations do not set minimum export percentages for public FZ projects (the percentage of output that must be exported). Instead, the power to set requirements on export percentages is assigned to relevant ministers.23

Tax incentives provided to FZ companies are as follows:

Exemption from corporate income tax on business profits (indefinite CIT holiday)24

Exemption from personal income tax on dividends and gains on FZ company shares

Exemption from customs duties and VAT on imports of goods and services25

Zero-rating of VAT on purchases of domestic goods and services (with VAT charged on goods and services sold to the domestic market).26

The exemption from customs duties and VAT (third bullet) continues to apply for machinery and equipment (other than passenger cars) that “temporarily exit” FZs into the domestic market. The conditions (and presumably the maximum amount time for “temporary exit”) are established by the Council of Ministers. While providing these exemptions, the INVL imposes certain charges on imports, and charges akin to turnover taxes on domestic sales and exports of FZ products, as summarised in Table 6.3.

For storage projects,27 the 2% charge on imports matches the 2% customs duty provided by the INVL as a general incentive (noted above). For manufacturing and assembly projects, the charge (1 or 2%) on gross revenues on sales (export or domestic) is akin to a turnover tax. Presumably, the turnover taxes are applied given the exemption from CIT on profit. A well-known problem with a turnover tax is that, when used as a substitute for taxation of profit, the effective tax rate on profit increases inversely with the profit rate – less profitable firms bear a higher tax rate on their profit. Given the distortions to competition amongst firms that this creates, turnover taxes are typically targeted in other countries at small firms as a simplification measure, substituting for tax on profit and/or VAT. Turnover taxes are targeted to small firms by applying only to firms with turnover below a ‘small business’ threshold.

Concerns with customs duty exemptions and design of the ITA

The customs duty exemption for imported items brought into Egypt for temporary use should be circumscribed to a fixed list of products, and the term ‘temporary’ should be defined with objective criteria and prescribed in the associated Law.28 Presumably the exemption is provided to reduce the cost of business inputs, and therefore the list should be specified to exclude final consumption goods. To mitigate against tax avoidance, conditions should be specified in regulations that indicate when a duty exemption can be provided, and the considerations determining the maximum duration of ‘temporary.’

According to the authorities, the new Investment Law (art. 39) and its executive regulation regulate the movement of local and foreign goods, materials, parts, and raw materials between the Free Zone and the domestic market, as well as the allowed time periods. The technical committee recommendations of Free Zones (no. 2/206/2011) specifies three months with a possible renewal for another three months for local and foreign goods and materials.

The basic design of the investment tax allowance is also problematic for the following reasons:

The ITA is based on the ‘investment cost of a project’ determined as the amount (value) of equity rights plus long-term liabilities of a company invested in fixed assets, intangible capital and working capital.29 By focusing on balance sheet amounts, rather than actual expenditures on physical capital assets, the base of the ITA could include amounts invested abroad (foreign assets generating income outside of Egypt), and tangible and/or intangible assets licensed to foreign companies. The base is too broad where the purpose is to incentivise investment in production in Egypt.

The ‘one-time’ feature means that where the amount of capital injected into a company is increased following the commencement of activity, the additional investment is not included in the base of the ITA (an additional deduction is not available).

The Article 12 restriction to curtail churning is limited to tangible assets.30 Given that the investment deduction can be claimed in respect of intangible (‘non-material’) assets, as indicated in the Executive Regulations, this means that the base of the ITA could include pre-existing intangible assets. MOF authorities explain that the reason for this is to avoid instances where investors are denied an ITA where ‘investment cost’ includes amounts paid for an existing trade name.

The targeting of the 30% ITA for Sector B investments is imprecise. For example targeting to SMEs is imprecise as the term ‘SMEs’ is not defined (e.g., with reference to turnover or asset size). Similarly, there are no thresholds given that specify ‘projects depending on or producing new and renewable energy’. This lack of precision makes it unclear whether a project that uses a minimal amount of new or renewable energy (e.g., a single solar panel) qualifies.

Determining how to treat firms that operate in targeted and non-targeted regions (and sectors) is difficult, requiring separate accounting of the base that is used to determine the incentive amount – which enables creative accounting by tax advisers.31 Tax incentives to stimulate economically depressed areas should be subject to proper cost-benefit analysis, given the poor track record worldwide of location-based targeting.

Rather than listing qualifying sectors, consideration should be given to listing non-qualifying sectors – for example where national security concerns arise and foreign investment is less desirable. This would recognise the difficulty for policy makers to identify sectors where markets fail in allocating capital or where net benefits to society from investment are the greatest.

Concerning additional incentives, the scope of subsidies provided is uncertain. Neither the law (Article 13) nor the Executive Regulations specify the types of technical training that qualify, or the training institutions (including in-house) that qualify, or the fraction of expenses that are covered. Similarly, under Article 13, all or part of expenses incurred in providing utilities to an investment project are subsidised. This provision raises questions over the types of utility expenses that qualify (electricity, gas, water?) and the fraction of expenses that are covered. Decisions to be taken are based on decisions of the Council of Ministers and GAFI, presumably on a case-by-case basis.

The Executive Regulations that specify conditions for obtaining additional incentives also raise questions, requiring administrative discretion in deciding whether conditions are met in practice.32 The requirements and measures of technology transfer are not specified in the law or regulations. Similarly, requirements and measures of research findings used in production are not specified. Presumably, GAFI holds the power to determine how the conditions are to be interpreted on a case-by-case basis.

The imprecise nature of the targeting (scope) of these incentives and conditions on eligibility create uncertainty and require further guidance from authorities. In general, this approach is problematic as it involves significant discretion on the part of authorities in awarding subsidies. As observed elsewhere, administrative discretion should be kept to a minimum through greater guidance and specificity in the laws and regulations themselves (and not on their interpretation by officials) to avoid opportunities for corruption. Moreover, where rules are applied on a case-by-case basis in a non-uniform manner across taxpayers, unfair competition results. Uncertainty over eligibility, the cost of bribes, and scope for an uneven playing field all pose a deterrent to investors.

Investment zone and technological zone projects are eligible for general incentives, special incentives and additional incentives and the concerns identified above in relation to these (see sub-section 2) apply. In particular, the conditions for duty exemptions should be clarified in regulations (including lists of eligible products and conditions around temporary use). Also, the investment tax allowance should be based on expenditures on depreciable capital used in Egypt and targeting criteria should be clarified and sharpened to avoid efficiency losses and specified in regulations to reduce discretionary power in deciding how subsidies are allocated.

Tax incentives for free zone companies come with challenges

Egypt provides generous tax incentives to projects in FZs, which raises three concerns. The first is with the efficiency of corporate tax holidays.33 A second concern is the tendency for FZ companies to sell into the domestic market where they enjoy a competitive advantage over companies outside of FZs (non-zone companies) owing to indirect (and direct) tax relief targeted at FZs. Total factor productivity growth in the economy may be impeded where FZ companies are able to largely avoid export markets and attendant pressures for business efficiencies needed to be profitable at internationally determined output prices.

Third, indirect tax relief for FZ companies – which waives VAT and customs duties on imports and zero-rates for VAT purposes purchases of domestic supplies – offers opportunities to evade taxes. These opportunities arise under provisions that allow tax-free transfers of commodities of FZ companies into the domestic market on a temporary basis, and tax-free transit through FZs of commodities moved from one border point to another. As tax-free entry of goods into FZs effectively multiplies opportunities to evade tax on goods brought into the country, total revenues lost to avoidance and evasion may be significant.

Efficiency concerns with corporate tax holidays for free zones

As highlighted in a recent report to the G20 by international organisations,34 profit-based tax incentives, such as corporate tax holidays, are generally less efficient than cost-based tax incentives, such as accelerated tax depreciation and investment tax allowances and tax credits. This observation, based on many years of disappointing experience with CIT holidays, is an important consideration for Egyptian authorities as they seek to revitalise their investment promotion strategy.

As noted in the previous section, the current tax system in Egypt provides two main corporate income tax incentives35 – a CIT holiday that exempts profit from corporate income tax, available to FZ companies, and an ITA that provides a deduction against the CIT base, available to non-FZ companies. The authorities are encouraged to reconsider the relative advantages of granting an ITA rather than CIT holiday to new investments.

Under the new Investment Law No. 72, the rate of ITA differs depending on targeting criteria including the location of investment – sector A (50%) and sector B (30%). As noted in the previous section, the ITA is a one-time deduction earned as a percentage of investment (equity plus long-term debt) in a project assessed at the start of production. While the more limited targeting of newly granted CIT holidays in the new Investment Law is a positive development,36 the continued reliance on this form of tax incentive is of concern given the relatively large scale of FZ companies, the corresponding amounts of profit that escape CIT and the profit-shifting possibilities that continue to exist.37

Key factors in a cost-benefit assessment of corporate tax incentives for investment include returns on estimated additional capital and employment, and the social opportunity cost of forgone CIT revenues that inevitably result when tax relief is provided to redundant investment – that is, investment that would have occurred without the tax incentive. The review draws on the G20 report on effective and efficient use of tax incentives. In anticipation of next steps of incentive reform, the review is intended to offer general guidance in identifying the types of data that would be needed, to factor into a formal cost/benefit assessment of past and current incentives in Egypt.38

Productivity concerns from direct and indirect tax relief to free zones

Direct tax relief (profit exemption) and indirect tax relief provided to FZ companies raise concerns about reduced productivity growth in the Egyptian economy. Productivity growth may be hindered where these tax reliefs encourage firms to supply the domestic market where they enjoy a competitive advantage, rather than export markets where greater efficiency of business operations may be required to be competitive and profitable. These mechanisms are at play in Egypt’s FZs, as described in chapter 5 and according to the IMF (2017) and Mori (2017).

FZ companies enjoy considerable indirect tax advantages, including indirect tax deferral. FZ companies are encouraged to purchase inputs from domestic suppliers producing outside of FZs (non-FZ companies). Such purchases (backward linkages) are intended to bring wider benefits to the Egyptian economy of the FZ system. As non-FZ companies must compete with foreign suppliers, sales by non-FZ companies to FZ companies are zero-rated for VAT purposes. With zero-rating of sales by domestic suppliers, FZ companies are not charged VAT on domestic purchases and domestic suppliers are provided with tax credits to offset VAT paid on their inputs. Thus, VAT is removed from the entire chain of production underlying domestic supplies to FZ firms. This treatment matches that of foreign supplies, which are zero-rated exports in the host (source) country and are exempt from Egyptian VAT when imported by FZ companies.39

A non-negligible portion of FZ output is supplied to the domestic market (see Chapter 5 for further evidence). When output is sold to domestic purchasers, VAT should apply in full, without input tax credits, and customs duties should be collected on the foreign content of products sold. As noted below, the practice of waiving duties and not collecting any VAT on supplies to FZs creates opportunities for tax evasion. However, even in instances where taxes due are collected on sales to the domestic market,40 the ability to defer payment of tax provides cash-flow advantages and a lower effective tax rate on business supplies to FZ firms (with tax payments measured on a present value basis). In addition, profits of FZ companies are exempt from corporate income tax, and dividends, capital gains and interest on investments in FZ companies are exempt from personal income tax. These tax policies tend to lower the cost to FZ companies of domestic sources of finance.41 FZ firms are also exempt from paying property taxes, as well as enjoying other cost advantages.

These indirect tax and direct tax reliefs provide FZ companies with a competitive advantage when supplying goods and services to the domestic market relative to non-FZ firms. Given this advantage, FZ companies may be oriented to domestic markets.42 Chapter 5 provides evidence that this is the case, as a sizeable fraction of output of FZ companies (particularly those in public FZs) is sold to the domestic market, rather than exported. If tax policy does indeed encourage FZ firms to supply the domestic market, then this outcome raises a concern to the extent that it lessens pressures for FZ firms to innovate and transition to productivity-enhancing business strategies generally required to compete successfully in export markets. Moreover, tax policies that place non-FZ companies at a competitive disadvantage, tending to limit their domestic sales, may seriously curb their ability to achieve economies of scale required in order to position themselves to compete successfully in export markets.

Tax revenue losses from tax avoidance and evasion possibilities

While normally VAT and customs duties should be levied when products are sold by FZ companies into the domestic market, opportunities may arise whereby these taxes can be avoided, as the Investment Law allows commodities to be brought into the domestic market in some cases on a temporary basis free of VAT and customs duties.43 Neither the Investment Law nor the Executive Regulations define ‘temporary’, implying an uncertain deferral advantage. Additionally, as some tax/customs officials may succumb to accepting returns to facilitate a side-stepping of the law/administrative practices, the unfortunate reality is that VAT and customs duties are illegally avoided in some cases. While this outcome can occur under any system, the possibilities of deferral and the creation of multiple border crossing and transit check-points under a zone system multiply these opportunities.

Tax revenues are also lost where FZ companies use their CIT holiday status to shelter profits of other companies from corporate tax. Because profits of FZ companies are exempt from tax, while profits of non-FZ companies are not, tax-planning opportunities are created to artificially shift taxable profit to FZ companies. One way is through commodity transactions between FZ companies and related non-FZ companies, with non-arm’s length pricing used to shift taxable profit. Taxing projects rather than entities through a modified form of group taxation can provide partial tax base protection, but such measures are limited in scope and reach. Financing arrangements (including back-to-back loans) and other arrangements may be used to shift otherwise taxable profit into a CIT-free enclave.

Proper management of tax holidays requires continuous monitoring of operational activities and financial arrangements of tax holiday firms, to verify compliance with qualifying conditions and to detect tax evasion. Where key conditions for tax holiday status are not observed, then it would be appropriate that actions be taken to withdraw tax relief that has been provided.

The treatment of transit goods, free of all taxes and charges, would be expected to encourage businesses to consider ways in which non-transit goods could be mischaracterised as transit goods. Given this, it would be prudent to ensure that goods passing through the country as transit goods be subject to inspection, while the Executive Regulations appear to allow for random verification. The Executive Regulations (Article 37, paragraph 3) state that “The Zone Management shall inspect the goods once they reach the Zone through random sample or detailed inspection.”

Given opportunities created for avoiding customs duty and VAT on goods brought into the country through FZs, and opportunities for avoiding VAT on zero-rated domestic supplies purchased by public and private FZ companies, it is prudent to monitor export percentages, as per the requirements defined in the Investment Law. Export share percentages should however be a temporary measure. Such requirement should be removed in cases where CIT holidays are phased-out and/or the gap in customs duty and VAT rates between the FZ and inland regime are reduced. The terms of the export share percentage should not raise potential risk of non-compliance with WTO rules, notably the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM).

Governance of tax incentives

This section addresses the governance of tax incentives – including current and best practice in introducing and amending tax incentive legislation, the monitoring of tax incentives, and reporting on them. Authorities are encouraged to consider reform of the mandates of the public institutions engaged in tax incentive policy and implementation, and how reform has the potential to go a long way in improving overall governance in Egypt. As in other countries where corruption is a serious problem, the tax system can be a major fault line. By sharpening legislation and regulations on tax incentives (covering implementation, monitoring and reporting), accountability of the institutions involved is increased, and the rule of law and role of parliament are strengthened. Through this process, fundamental tax incentive reform has the potential to profoundly shape and strengthen governance.44

Introducing and amending tax incentive legislation

Accountability of government over tax incentives is weakened by diffuse legislative powers, the involvement of multiple ministries and agencies in setting tax incentive policies, and broad discretion in interpreting tax incentive eligibility. Each of these contributes to the opaqueness of tax incentive policy and administration, which translates into reduced government accountability. A review of the new Investment Law finds a complex and non-transparent tax incentive policy decision-making structure, with diffuse responsibilities and powers amongst the Ministry of Finance, GAFI, and relevant ministers. The current patchwork complicates decision-making and creates a lack of accountability, which limits analysis, evaluation and fundamental reform. The Prime Ministerial Decree No.7/2020 identifies Zones A and B and provides for tax incentives specific to each zone. Zones A, which include South of Giza Governorate, Governorates affiliated to the Suez Canal Region (Suez - Ismailia - Port Said) and Border Provinces (Governorates of the Red Sea from the South of Safaga), are identified as priority development areas. Prime Ministerial Decree (6/2020) clarifies the conditions of project expansion benefitting from investment incentives.

While certain improvements have been made, including less pervasive use of corporate tax holidays, relief from income taxes, VAT and customs duties is still embedded outside of the main legislation.45 In particular, tax incentives are provided mainly in the new Investment Law or in the SEZ Law, and not in the Income Tax Law, VAT Law and Customs Law that the tax incentives provide relief from. This makes it difficult to determine the net implications of various provisions that together determine effective tax rates and the amount of tax due. This practice also clouds responsibility over tax policy.

To address this, legislation that authorises the provision of tax incentives should be embedded in main statutes that the tax incentives provide relief from (e.g., law providing an investment tax allowance should be contained in the Income Tax Law; law providing for a VAT exemption should be contained in the VAT Law). With this change, the recently enacted Investment Law would be amended, so that articles that currently provide for tax incentives are revised to reference new articles in the Income Tax Law, VAT Law and Customs Law. Similarly, regulations for tax incentives should be included in the regulations of the relevant tax legislation.

Good practice in providing tax incentives involves prescribing qualifying conditions in laws, regulations and bulletins (official interpretations of laws) and minimising the discretion of tax administration and other officials in determining eligibility. The Minister of Finance should have final authority over the determination of the design and targeting of tax incentives. Limiting discretion helps serve various objectives. First, it curbs opportunities for corruption involving tax officials accepting compensation for the granting of tax relief. Second, limiting discretion in determining eligibility helps provide certainty of tax treatment, which reduces uncertainty for taxpayers in determining after-tax returns on projects – including their own projects, and those of competing firms. By reducing uncertainty, investment is encouraged. Third, where tax incentives are granted on a case-by-case basis, involving private negotiations with taxpayers, the fiscal and broader implications of agreements are not known by the general public – and possibly not known by tax official, which inhibits assessments of impacts and determinations of whether policies or practices should be revised.

Furthermore, following best practice, the Minister of Finance should have sole authority to introduce, amend or withdraw tax incentive legislation, after approval of the Council of Ministers.46 This could be anchored in the Constitution or in public finance management legislation.47 Responsibility for deciding tax incentive policy and design should be centralised within the Ministry of Finance and the Egyptian Tax Authority, drawing on tax experts from multiple fields (e.g., economists, lawyers, accountants). The General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI), as well as other ministries should be involved in the design process.48 In deciding upon tax incentive design, a main objective should be to minimise the discretion of government officials in determining eligibility for tax relief (Box 6.2).

The government is encouraged to provide the Ministry of Finance with the necessary resources to finance the hiring of highly-qualified staff to undertake economic analysis of current tax policies and possible reforms.49 Staff need to be trained in modern public finance theory, frameworks and toolkits to assess tax proposals submitted to government for consideration, and to propose and analyse reform agendas.

Analysis of tax policy, including the costing of tax incentives, is data intensive. Given this, and the importance of the Ministry of Finance being equipped to provide high-quality, independent policy analysis, it is imperative that tax authorities regularly collect taxpayer-level data (gathered from tax returns) to feed into revenue estimation (microsimulation) models. Comprehensive taxpayer data collection requires that all businesses, including FZ companies, complete and file tax returns. These changes will involve institutional arrangements that may require legislative action. The ETA is currently undertaking a wide-ranging business process reengineering project, whereby all tax administration processes will be automated. This provides a timely opportunity to address key governance issues.

Monitoring tax incentives

As a check on the operation and outcomes of any tax incentive regime, careful monitoring is essential. As reviewed earlier, the tax incentive regime has many concessions intended to limit unintended distortions. Examples include the duty exemptions provided to domestic firms supplying zone companies, the temporary exit of goods to the domestic market and the allowance of transit commodities without VAT and duties that would otherwise apply. Given these concessions, data collection and monitoring are needed as a check on the integrity of the system and to make adjustments to policies and practices where fraud is detected. It is not clear from a review of the investment promotion legislation and regulations which government body is responsible for monitoring tax incentives, including data collection on take-up, the measurement of forgone tax revenues, and the determinations of whether investors (FZ companies) are complying with commitments in relation to export percentages and employment of local workers. It is also not clear which entities are tasked with determining corrective interventions when tax incentive design is found to be problematic.

Legislation authorising tax incentives should specify which government agency has responsibility for monitoring compliance and enforcing penalties in cases of non-compliance. In practice, experience shows that electronic tracking is required of transactions in goods and services (quantities and values) – including the tracking of commodity codes and values for commodities receiving duty waiver, duty drawback, transit goods, exported goods, goods sold to domestic market, and goods temporarily brought into the domestic market.

Strict and proportionate penalties are required as a deterrent to fraud, including a claw-back of tax relief in cases of non-compliance (e.g., export requirements as percentage of production, local hiring commitments). Where FZ companies are permitted to continue (under grandfathering rules) to benefit from FZ incentives provided to them, these firms should be held to account for the commitments made to the government in benefiting the host country (e.g., in terms of local hires, and exports).

Reporting of tax incentives

Annual tax expenditure reporting to parliament of revenues forgone by tax incentives (part of tax expenditure reporting), as part of the annual budget and budget documentation cycle, is recognised as a cornerstone of good practice in providing tax incentives. Tax expenditure reporting is required to ensure transparency and oversight, in the same way that tabling direct expenditure programmes is of central interest to parliament.

In its pursuit of best practice, the government is encouraged to introduce legislation requiring tax expenditure reports to be included with budget documents (annually or bi-annually). The reporting of tax incentives should identify the policy purpose (as specified when introduced or amended) and the estimated amount of forgone tax revenue. Consistent with this, legislation should be introduced that requires the ETA each year to provide the Ministry of Finance with anonymised micro-level data (e.g., gathered from tax returns) to enable robust estimates of forgone tax revenues. Furthermore, given the extensive tax incentives provided to FZ companies, reports should be prepared (annually or bi-annually) giving aggregate data by sector, on total production, inventories (storage), export and domestic sales, customs duty waivers and customs duty drawbacks (for FZ companies and separately for domestic suppliers).

Lastly, it is recommended that the government instruct the MOF to undertake cost-benefit analysis of FZ incentives and other major tax incentives (identified by a ranking of tax revenue forgone estimates). While resource demanding, it is important given the scarcity of public funds that societal benefits and costs be compared, and corrective action taken when necessary. Of major fiscal policy concern are instances of incentives having limited impact in boosting investment expenditure, and yet involving significant forgone revenue, due to tax relief provided to redundant investment, and limited success in countering tax avoidance and evasion by MNEs, facilitated by tax incentives (most notably CIT holidays).

References

Aitken, B. and A. Harrison (1999). “Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Foreign Direct Investment? Evidence from Venezuela.” American Economic Review, 89, 605-618.

Boadway, R., N. Bruce and J. Mintz (1984). “Taxation, Inflation and the Marginal Tax Rate on capital in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 15, 278-93.

Clark, W. (2000). “Tax Incentives for Foreign Direct Investment: Empirical Evidence on Effects and Alternative Policy Options.” Canadian Tax Journal, 48, 1139-1180.

_______ (2010). “Assessing the Foreign Direct Investment Response to Tax Reform and Tax Planning.” in Cockfield, Arthur J. (ed.), Globalization and its Tax Discontents—Tax Policy and International Investments, University of Toronto Press, 84-114.

Clark, W. and A. Klemm (2015). “Effective Tax Rates and Multinationals: The Role of Tax Incentives and Tax Planning.” Canadian Tax Journal 63(1), 133-148.

De Mooij, R. and S. Ederveen (2008). “Corporate Tax Elasticities: A Reader’s Guide to Empirical Findings.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24 (4), 680-697.

Defever, F. and A. Riaño (2017), “Subsidies and export share requirements in China”, Journal of Development Economics, 126, pp. 33-51.

Department of Revenue, India (2014). Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General for India – Performance of Special Economic Zones, No. 21.

Devereux, M.P. and R. Griffith (1998). “The Taxation of Discrete Investment Choices”, Institute for Fiscal Studies Working Paper 98/16.

IMF (2017). “Arab Republic of Egypt – Selected Issues.” (December)

IMF, OECD, World Bank, and United Nations (2015). “Options for Low Income Countries' Effective and Efficient Use of Tax Incentives for Investment.” Study and Background Paper Prepared for the G20 Development Working Group. Washington.

Jorgenson, D. (1963). “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” American Economic Review 53, 2, 247-259.

King. M. (1974). “Taxation, Investment and the Cost of Capital.” Review of Economic Studies, 41, 21-35.

King, M. and D. Fullerton (1984). The Taxation of Income from Capital: A Comparative Study of the United States, The United Kingdom, Sweden and West Germany, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mori, I. (2017), Free zones in Egypt: A critical reading, Al-Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, December 2017.

OECD (2002). Foreign Direct Investment for Development – Maximising Benefits, Minimising Costs. Paris, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investmentfordevelopment/1959815.pdf.

_______ (2007). Tax Effects on Foreign Direct Investment – Recent Evidence and Policy Analysis. OECD Tax Policy Studies, No. 17. Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/39866155.pdf.

_______ (2013). OECD Principles to Enhance the Transparency and Governance of Tax Incentives for Investment in Developing Countries. Paris.

OECD (2015), Designing Effective Controlled Foreign Company Rules, Action 3 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241152-en.

OECD (2016), Limiting Base Erosion Involving Interest Deductions and Other Financial Payments, Action 4 - 2016 Update: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268333-en.

UNCTAD (2000). Tax Incentives and Foreign Direct Investment: A Global Survey.

UNIDO (2011). Africa Investor Report: Towards evidence-based investment promotion strategies.

U.S. Council of Economic Advisors (2015). Economic Report of the President. Washington.

Van Parys, S. and S. James (2010). “The Effectiveness of Tax Incentives in Attracting Investment: Panel Data Evidence from the CFA Franc Zone,” International Tax and Public Finance,17, 400-429.

Notes

← 1. An export share requirement of 80% of production exists for private FZ companies. It was set by the Investment law Executive Regulations Article No. 76. Export share requirements could have unintended consequences by lowering export prices and increasing those of goods sold on the domestic market (Defever and Riaño, 2017). They also must be designed to ensure compliance with WTO rules, notably the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. Chapter 5 provides further analysis on ESR effects on Egyptian zone-based exports.

← 2. For example, IMF, OECD, UN, World Bank (2015[69]) describe different methods to calculate revenue forgone from tax expenditures, while IMF (2019[70]) sets out guidelines for tax expenditure reporting.

← 3. The Egyptian government is currently drafting a Medium-Term Revenue Strategy that also considers current and new reforms of tax policy and tax administration.

← 4. A 40% CIT rate applies to the Central Bank, the Suez Canal, and the General Authority for Petroleum. A slightly higher rate (44.5%) applies to oil exploration and production companies.

← 5. The exemption involves the prohibition of loss carryover if 50% or more of the ownership of share capital changes, or if a company’s main business activity has changed. This provision is limited to listed companies.

← 6. Current rules encourage ‘double-dipping’, whereby machinery and equipment is sold from one taxpayer to another, to obtain multiple tax savings from the same unit of capital.

← 7. Exempting capital gains on shares in zone companies tends to reward and thereby incentivise patient capital invested in growth-oriented firms. In contrast, exempting dividends tends to reward investment in mature firms that distribute (rather than reinvest) their profits.

← 8. The Investment Law No. 72 of 2017 repealed application of the (previous) Law on Investment Guarantees and Incentives No. 8 of 1997 (incentives granted in the past under Law No. 8 are grandfathered under the new Law No. 72). Under previous law (No.8), a 20-year CIT holiday was provided to companies located outside the old valley, in areas designated by the Council of Ministers. A 10-year CIT holiday was provided to companies in new industrial zones and located in remote areas determined by decree by the Prime Minister. In other cases, firms engaged in (any) commercial or industrial activity were provided a 5-year CIT holiday.

← 9. Article 14 of INVL.

← 10. Article 10 of the Executive Regulations of INVL.

← 11. The regulations explain that such areas are characterised by i) poor levels of economic development, low gross domestic product and the surge of the informal sector; ii) poor operation level, low employment opportunities and rising unemployment rates; iii) remarkable population surge, poor education quality and rising illiteracy, poor health services and high poverty rates.”

← 12. Articles 11 and 14 of INVL.

← 13. Article 11 of INVL states that the Prime Minister may determine by decree sub-sectors that the ITA applies to, for sector A and B-type of investments. The Supreme Council of Investment may add qualifying activities.

← 14. Presumably an ITA claimed by an unincorporated business may be used to offset wage and non-business income.

← 15. Article 13 of INVL.

← 16. Under Article 13, the Council of Ministers may also grant other non-tax incentives.

← 17. The English translation of the Executive Regulations show a 20% export requirement, but MOF authorities advise that the text should read 50%.

← 18. Under Article 28 of the INVL, investment projects located in Investment Zones are eligible for incentives provided under Part I and Part II of the INVL. Chapter II of Part II (Investment Guarantees and Incentives) provides General Incentives described in Article 10, Special Incentives in Article 11, and Additional Incentives in Article 13.

← 19. Approval is required from the Board of Directors of GAFI.

← 20. The customs duty exemption is more generous than the 2% customs duty rate under General Incentives.

← 21. Under Article 32 of INVL, investment projects located in Technological Zones are eligible for Special incentives described in Article 11.

← 22. Article 34 of INVL.

← 23. Article 35 of INVL assigns this power to ‘appropriate’ ministers including the minister of industrial affairs.

← 24. Article 41 of INVL provides an exemption for corporate and personal income tax.

← 25. Article 39 INVL.

← 26. Article 6 of VAT Law No. 67 of 2016. Zero-rating of VAT on domestic supplies does not apply to passenger cars.

← 27. A storage project is a project where the sole business activity is storing (housing) commodities.

← 28. While the (temporary) customs duty exemption is targeted at the manufacturing projects, the exemption is prone to abuse if the targeting is not also limited to specific commodities (e.g., machinery and equipment).

← 29. Executive Regulations, Article 11.

← 30. The INVL aims to curtail ‘churning’, whereby pre-existing capital is misrepresented as new capital, to qualify for the ITA. Article 12 stipulates that to qualify, “neither shareholders nor partners nor owners of establishments have offered, contributed or used any of the tangible assets of a company or an establishment, existing since the date on which the provisions of this Law come into force, in setting up, incorporating or launching an Investment Project enjoying the incentives awarded by this Law.”

← 31. Targeting concerns are generally the greatest when profit-based tax incentives are used. Profit-based tax incentives (like corporate tax holidays) provide tax relief to firms that are investing and to firms that are not – in which case the incentive merely waives tax on profit from prior-year investment. Given the scope for pure windfall gains (tax savings) to investors, it is understandable that governments would wish to target tax relief to growth-oriented sectors. But this is difficult to determine and accomplish. An advantage of cost-based tax incentives is that they provide tax relief only to firms that are investing (making targeting less of a concern).

← 32. MOF authorities explain that the condition under Article 12 of the Executive Regulations, requiring that “Egypt should be a main country for producing its products. Also, the main country of the company’s products should be Egypt” concerns where production occurs (not where products are sold) and that thresholds are determined by GAFI.

← 33. An analysis which compares CIT revenues forgone by a CIT holiday with CIT revenues forgone by an investment tax allowance (which when granted at a 33% rate is predicted to provide the same boost to the level of investment) will be available separately in a link (to be established). The analysis, based on standard investment theory, is carried out at the investment-project level using illustrative tax and non-tax parameters for Egypt.

← 34. See IMF, World Bank, OECD and United Nations (2015).

← 35. The term ‘corporate income tax incentive’ refers to measures that provide an offset to (relief from) corporate income tax, intended to encourage investment. The CIT holiday for zone companies and the ITA are prescribed in INVL, which repealed the provision of incentives under the Law on Investment Guarantees and Incentive No. 8 of 1997. Under this previous law, a 20-year CIT holiday was provided to companies located outside the old valley, in areas designated by the Council of Ministers. A 10-year CIT holiday was provided to companies in new industrial zones and located in remote areas determined by decree by the Prime Minister. In other cases, firms engaged in (any) commercial or industrial activity were provided a 5-year CIT holiday. CIT incentives previously granted under Law No. 8 are grandfathered under the new Law No. 72.

← 36. The new Investment Law includes ‘grandfathering’ provisions that continue to provide an exemption for current and future profit on projects that were granted CIT holiday status under the old investment law.

← 37. The profit-shifting opportunities concern the use of non-arm’s length transfer pricing and financing arrangements to shift otherwise taxable profits from companies outside FZs to related companies inside FZs.

← 38. A recent reform requires FZ companies to report income tax statements. This positive development should be strengthened to require reporting of tax returns.

← 39. As customs duties are waived on imports by FZ companies, neutrality would require that a duty drawback is provided to domestic suppliers to FZ companies. A duty drawback aims to provide domestic suppliers with an offset to customs duty paid on imported foreign products used as inputs in the production of output sold to FZ companies.

← 40. While required by law to charge customs duties on foreign content, when selling products into the domestic market, opportunities are created to avoid customs duties on imports as the amount and true value of foreign content is often difficult to establish.

← 41. Where investors require a fixed after-tax rate of return (e.g., available on other investments), policies that lower personal tax on dividends, capital gains and interest may operate to lower the pre-tax rate of return that investors are willing to accept. Where this is the case, the cost of financing of firms may be significantly reduced.

← 42. As a result of tax advantages implying lower costs, FZ companies may be (inadvertently) provided scope to charge below-market prices on products sold in domestic markets. This advantage may limit pressure to innovate production and distribution strategies, in order to achieve cost savings and competitive pricing in export markets.

← 43. This recognises that the present value of deferred tax payments declines as the period of deferral is extended. In the limiting case, the present value approaches zero.

← 44. See OECD (2013).

← 45. Income Tax Law No. 91 of 2005, and VAT Law No. 67 of 2016.

← 46. Meetings of the Council of Ministers and other committees arranged to decide on applications for tax incentives (those decided on a discretionary basis) should be recorded to provide an auditable account of the application assessment process and the criteria used in determinations.

← 47. Public finance management (PFM) legislation should authorise only the Minister of Finance to introduce legislation that imposes (or provides relief from) national taxes and duties. Under this structure, the Minister of Finance would have sole authority to introduce, amend or revise tax relief including targeted tax incentives.

← 48. Other relevant ministries to contribute to discussions would presumably include the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the Ministry of Investment and International Cooperation, the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Wealth, and the Ministry of Local Development.

← 49. In March 2016, the organisation of the Ministry of Finance was changed to include three Vice Ministers, including a Vice Minister of Finance for Tax Policy. Since then the tax policy analysis has been centralised in the MOF.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/9f9c589a-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.