1. Measuring trust in government to reinforce democracy

Trust is an important indicator to measure how people perceive the quality of, and how they associate with, government institutions in democratic countries. This chapter presents a summary overview of the report Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy. It includes a discussion of the motivation behind the inaugural OECD Survey on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (Trust Survey), presents the OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, and summarises the key findings of the report.

Public trust helps governments govern on a daily basis and respond to the major challenges of today and tomorrow: the ongoing health and economic crises, the longstanding rise in inequalities, population ageing, technological advances, and the existential threat of climate change. Sufficiently high levels of institutional trust can help governments reduce transaction costs – in governance, in society, and in the economy – and help ensure compliance with public policies. Trust can help foster public investments in challenging reforms and programmes that produce better outcomes. In democratic countries, moderately high levels of trust – along with healthy levels of public scrutiny – can help reinforce important democratic institutions and norms.

Yet just as public trust serves as an input to governance – helping or hindering policy implementation – public trust is an equally important outcome of governance. Trust is an expression of how people perceive their public institutions and what they expect of their government.

High trust in public institutions is not a necessary outcome of democratic governance, of course. Indeed, low levels of trust measured in democracies are only possible because citizens in democratic systems – unlike in autocratic ones – have much greater freedom to report that they do not trust their government. Critical views and constructive feedback can even be a sign of a healthy democracy. Yet trust remains an important indicator to measure how people perceive the quality of, and how they associate with, government institutions in democratic countries.

From a policy-making perspective, then, it is important for democratic governments to think holistically about both these inputs and outputs: how trust influences policy outcomes, and how trust is influenced by policy processes.

This report explores the relationship between governance and trust by analysing original data from the inaugural OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (hereafter “Trust Survey”). Covering twenty-two OECD countries, the Trust Survey is the most thorough cross-national stocktaking of the complex relationship between public trust and democratic governance to date. It offers actionable ways forward to reinforce institutions and democratic cultures.

This report finds that most OECD governments are performing satisfactorily in public perceptions of government reliability, service provision, and data openness, although governments should still strive for better results in these areas. Governments are faring considerably less well, however, in perceptions of key features of advanced democratic governance. Few people see their government as responsive to their wants and needs, and many see high-level political officials as easily corruptible. Disadvantaged groups – young people, women, people with lower incomes and those with less education – are less likely to trust their government and are often sceptical that their government listens to them.

Governments must take a more holistic approach to building trust, considering both processes and outcomes. This means focusing in particular on how to address these perceptions of low government responsiveness and integrity, in order to consolidate the functioning of democratic societies. This will help advance the pandemic recovery and help address the significant policy challenges countries face today.

The Trust Survey took place at a challenging time in most of the surveyed countries: November and December 2021, nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic. While most OECD countries saw an uptick in trust in government in 2020 around the start of COVID-19 – the so-called “rally around the flag” effect – by mid-2021 this trust had declined in many countries (Brezzi et al., 2021[1]). The Survey interviewed respondents in 13 of the 22 participating countries at the start of the fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, which corresponded with rising case counts and interventionist measures like the closures of public places and the start of vaccine passes. Indeed, in several European countries, the start of Trust Survey interviews corresponded with new national lockdown measures.

Perhaps related to this, many of the European countries are clustered together in the survey results exhibiting moderate to low levels of trust (Figure 1.2). And across countries, “pandemic fatigue” has set in, perhaps especially in Asia – where the pandemic has been going on the longest.1 The Trust Survey therefore presents a point-in-time2 estimate of perceptions of government that, for some questions, represents a particular challenging period for self-assessment. These perceptions may also be influenced, to different degrees across countries, by more “objective” economic or social outcomes of governance, as well as underlying cultural or societal differences across countries.

At the same time, the vast majority of questions asked in the Trust Survey investigate structural and persistent features of governance that predate (and are likely minimally impacted by) the pandemic. These include, for example, questions about the perceived integrity of public servants, the fairness of government programmes, governments’ responsiveness to public feedback, and the reliability of public services. These are structural traits of OECD governments that long preceded – and will long outlast – the current crisis. These questions are based on foundational concepts in the OECD Trust Framework (Box 1.2), which has been developed over the past decade with OECD governments’ feedback.

OECD member countries’ participation in the Trust Survey was optional. The twenty-two countries who volunteered to be in the survey have placed themselves under this microscope to understand better what is driving trust in government in their country and other countries – and to make use of this evidence to explore what policies may contribute to building trust, preserving it or restoring it. Potential levers may include engaging better with diverse populations, responding more effectively to citizens’ needs and growing expectations, improving the design and delivery of public programmes, addressing integrity issues, and adopting public sector reforms that foster stronger, long-term commitments to the people. Such efforts, in turn, should help improve public trust in government institutions. Given the depth of challenges facing democracies going into the third year of the pandemic, the OECD is strongly committed to helping countries rebuild trust.

Countries’ participation in the Trust Survey – in and of itself – represents a high degree of transparency and democratic accountability. It is an impressive commitment to public engagement.

The OECD explores the relationship between trust and governance using an original and comprehensive dataset of representative survey data across twenty-two countries: the OECD Trust Survey. Reflecting a long history of OECD work on this topic, this project represents the first cross-national survey devoted solely and extensively to measuring institutional trust and its determinants. The questions in the Trust Survey are based on foundational concepts in the OECD Trust Framework (Box 1.2), which, under the guidance of the OECD Public Governance Committee, lays out key drivers of trust in government.

Given the importance of citizen perceptions for the viability and success of public policies, survey measurements of public trust should become regular, modern instruments of public governance in OECD countries, alongside traditional outcome measures like government expenditures, programme coverage, national income and poverty rates. Among the many mechanisms and initiatives to engage citizens, population surveys are an important tool for consulting people and allowing them to voice their opinion. Regular population surveys allow governments to gather input, hear people’s voices and inform policies accordingly. The Trust Survey, in particular, enables a careful look at the drivers of trust and levels of trust in different public institutions.

A brief overview of the survey method and documentation

The OECD Trust Survey, carried out by the OECD Directorate for Public Governance, has significant country coverage (usually 2000 respondents per country) across twenty-two countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Ireland, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The large samples facilitate subgroup analysis and help ensure the reliability of the results.

These surveys were conducted online by YouGov, by national statistical offices (in the cases of Finland, Ireland, Mexico, and the United Kingdom), by national research institutes (Iceland) or by survey research firms (New Zealand and Norway). The YouGov online surveys use a non-probability sampling approach with quotas to ensure that samples are nationally representative by age, gender, large region and education. The majority of the surveys conducted by YouGov took place in November and December 2021; the other surveys went into the field within a year of (before or after) that date. Mexico conducted face-to-face interviews focused on urban areas. For a short discussion of how different survey questions adapted to different national contexts, see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2.

For a detailed discussion of the survey method and implementation, please find an extensive methodological background paper at https://oe.cd/trust.

The survey process and implementation has been guided by an Advisory Group comprised of public officials from OECD member countries, representatives of National Statistical Offices and international experts. The OECD intends to continue to improve and conduct the survey on a regular basis in the coming years to help governments improve the way they govern, monitor results over time, and better respond to public feedback.

The underlying motivation of the OECD Trust Survey is to understand the drivers of trust in government. To what degree do a government’s competence and values influence trust in public institutions? Survey questions measuring reliability, responsiveness, integrity, fairness and openness reflect the key components of the OECD Trust Framework (Box 1.2).

As the survey data were collated and analysed, however, it became apparent that the results not only illustrate strengths and weaknesses of governments through the rubric of the Framework. The data-driven results also tell an important story about the need to reinforce democracy in OECD countries.

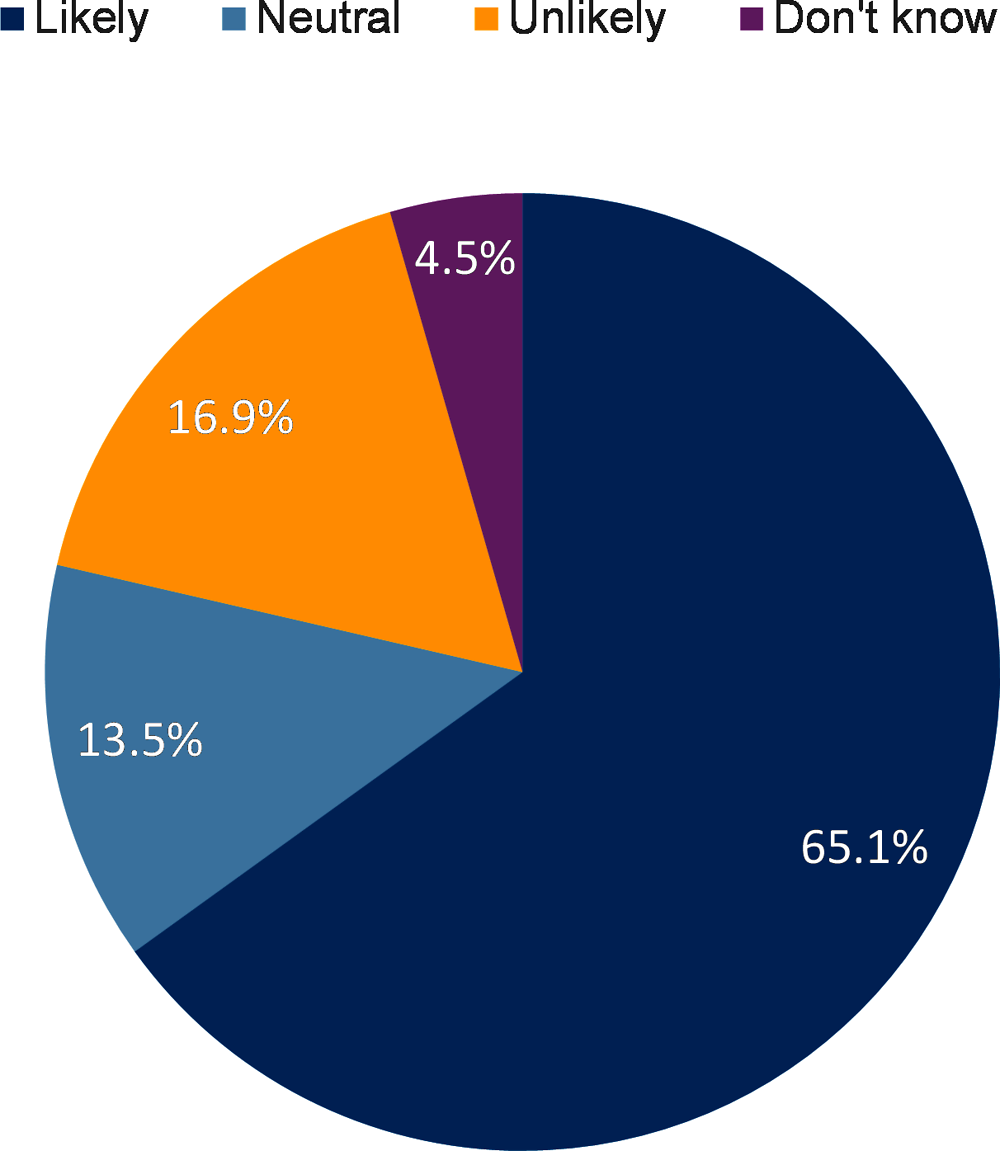

OECD governments are doing satisfactorily on what might be considered baseline measures of effective governance in developed countries. 65.1% of respondents, on average, say they can find information about administrative processes easily (Figure 1.1). A slight majority (51.1%) trust government to use their personal data safely. A majority in most countries say they are satisfied with their national healthcare (61.7%, on average) and education systems (57.6%, on average). About half of respondents (49.4%), cross-nationally, predict that their government will be prepared for the next pandemic (Chapter 4).

There is still significant room for improvement in terms of service provision, information access, and future preparedness, and – importantly – some countries are doing much better than others. But in general, governments are doing reasonably well on these measures of reliability, service provision and access to information.

OECD governments, in short, are governing.

Yet a crucial factor distinguishing democracy from other forms of government is equal opportunities for representation in governance. Trust Survey data illustrate that people in OECD countries see these democratic aspects of governance, in particular, as falling short – both in more bureaucratic policy-making processes and in more explicitly political, democratic processes. This discontent is likely caused by a range of explanations, including socioeconomic outcomes that fall short of people’s expectations for advanced democracies.

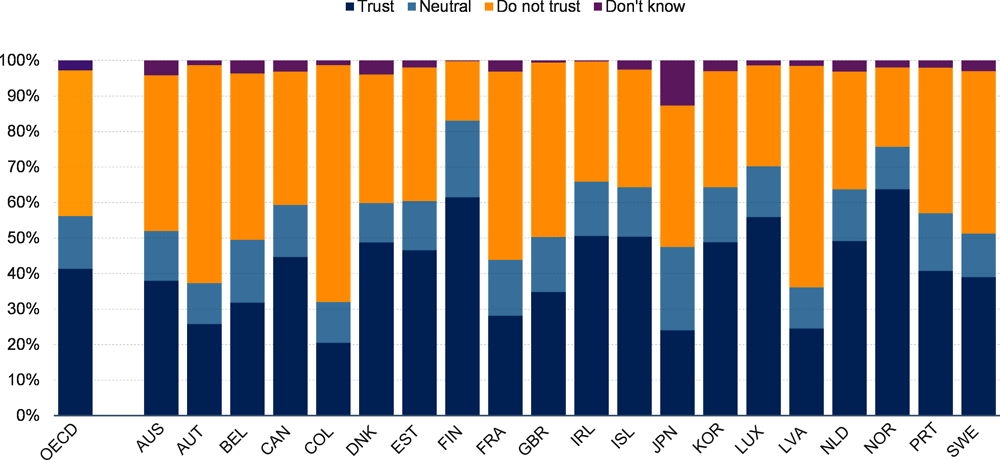

A basic signal of this discontent is the Trust Survey’s topline finding on trust. Only about four in ten respondents (41.4%), on average across countries, trust their national government (Figure 1.2). Of course, this average conceals wide variation. The share of people who trust their government reaches over 60% of the population in places like Finland and Norway, but rates are below 30% in about a quarter of countries.3

While fewer than half of respondents trust their national government, on average, it is worth noting that this does not mean a majority distrusts their government. In fact the share that trust and that do not trust are practically evenly split: 41.1%, on average, report that they do not trust their government.

Importantly, in some countries there is also a high degree of neutrality and uncertainty around this question of trust. 14.8% of respondents, on average, hold a neutral position – neither trusting nor distrusting their government – and about 3%, on average, report that they do not know. This group may be important, as they could perhaps be better engaged and persuaded by governments.

Cultural differences across countries may also explain the relative shares of neutral and uncertain responses to questions on trust in different institutions. Japan, for example, has high shares of respondents who either feel neutrally about trust in government or selected “Don’t know,” which is not associated with a number value on the scale. Taken together, a solid majority of respondents (60.2%) in Japan either trust government, hold a neutral view, or report they are unsure whether they trust government. Related to this, the share of respondents who do not trust government in Japan is below the OECD average of people who do not trust government. This suggests relatively high neutrality and an important flexibility in terms of trust in government in Japan. These midrange results for Japan are seen across several results in the survey (Box 2.1).

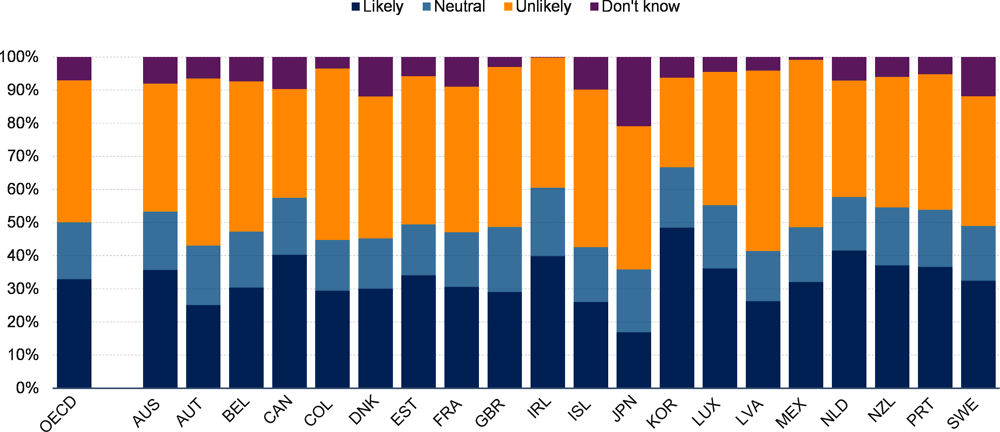

This finding on trust is driven, in large part, by a lack of confidence in government responsiveness, integrity, and equal opportunities. Results from multiple questions in the Trust Survey consistently illustrate that governments are seen as unresponsive to people’s demands both in policy making and in more obviously democratic processes. Only one third of people (32.9%) think their government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation, for example (Figure 1.3). And only about four in ten respondents, on average across countries, say that their government would improve a poorly performing service, implement an innovative idea, or change a national policy in response to public demands (Chapter 5). When considering more overtly democratic political processes, only three in ten say the political system in their country lets them have a say.

Results on perceptions of government integrity are similarly concerning. There is widespread scepticism around the integrity of policy makers: almost half of respondents (47.8%), on average across countries, think a high-level political official would grant a political favour in exchange for the offer of a well-paid private sector job, and over one-third (35.7%) of respondents, on average across countries, consider it likely that a public employee would accept money by a citizen or a firm in exchange for speeding up access to a public service (Chapter 5).

These feelings of disempowerment – a lack of voice in policy making, and the sense that political officials are captive to undue influence – are compounded by persistent, underlying inequalities in society.

The most vulnerable in society – youths, people living on low incomes, those with lower levels of education, and those who feel financially insecure – consistently report lower levels of trust and satisfaction with government (Chapter 3). There is a widespread sense that democratic government is working for some, but certainly not for all.

The Trust Survey is the result of the OECD’s long prioritisation of the issue of trust in government. After the 2008 global financial crisis eroded trust in governments, with profound implications for countries’ democratic foundations, countries at the 2013 OECD Ministerial Council Meeting called for “strengthen[ed] efforts to understand trust in public institutions and its influence on economic performance and well-being”. Following this call, the OECD built a conceptual framework – the OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – and statistical guidelines for measuring the drivers of trust in public institutions. These were tested in few countries via the OECD TrustLab project (OECD, 2018[2]; OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2017[4]; González and Smith, 2017[5]).

Following country reviews in Korea (OECD/KDI, 2018[6]), Finland (OECD, 2021[7]), and Norway (OECD, 2022[8]), the OECD Public Governance Committee in 2021 endorsed a cross-national survey to take stock of trust in government institutions, apply the theoretical foundations of the Trust Framework, and better understand the drivers of trust – and the OECD Trust Survey was born.

Defining trust and its determinants

The OECD defines trust as “a person’s belief that another person or institution will act consistently with their expectation of positive behaviour.” Trust offers people confidence that others, individuals or institutions, will act as they might expect, either in a particular action or in a set of actions (OECD, 2017[4]). While trust is influenced by actual experience and facts, it is often a subjective phenomenon based on interpretations or perceptions (OECD, 2021[7]). The OECD definition is informed by over half a century of academic research across disciplines like economics, political science, psychology and sociology (Levi and Stoker, 2000[9]; Norris, 2022[10]).1

The framework identifies five main drivers of trust in government institutions. They capture the degree to which institutions are responsive and reliable in delivering policies and services, and act in line with the values of openness, integrity and fairness. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the Framework has been reviewed through a consultative process entitled “Building a New Paradigm for Public Trust,” which engaged over 800 policy makers, civil servants, researchers, data providers and representatives from the private and non-profit sectors across six webinars between 2020 and 2021 (OECD, 2021[11]). This process led to a revision of the Framework intended to guide public efforts to recover trust in government during and after the crisis, with a particular focus on building back more inclusively, e.g. by taking into account socioeconomic, political and cultural differences, and by generating buy-in to address challenging, long-term, intergenerational issues like climate change. These drivers interact to influence people’s trust in public institutions and are compounded by countries’ economic, social and institutional situations.

← 1. Many academic definitions of trust include a component of vulnerability or uncertainty on the part of the principle in a principle-agent relationship (where the principle is the public and the agent is government institutions/actors). This is implicit rather than explicit in the OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, which attempts to measure determinants of trust.

Strengthening public trust in government is key to reinforcing democracy in OECD countries and building an inclusive recovery coming out of the pandemic. This report suggests that these goals must be targeted together. Governments cannot focus solely on the outcomes of policies but also on processes.

As we emerge from the crisis, and as governments understandably focus on social, economic and environmental outcomes, it is more important than ever that governments work to strengthen the democratic values and institutions that are the backbone of OECD governments today. By making the strengthening of trust between the public and their government an explicit objective of public policy, countries can reinforce democratic processes in all aspects of governance, across policy areas, while responding to evolving public expectations. This must be a whole-of-government approach across all levels of government, from civil servants to high-level political officials.

Respondents have reasonable levels of trust in their government’s reliability. Only a third (32.6%) of respondents, for example, say their government would not be prepared to respond to a future pandemic – a noteworthy outcome considering the ongoing human and economic costs of COVID-19 (Chapter 4).

Most people, in most countries, report feeling satisfied with their national healthcare (61.7%) and education systems (57.6%), even in times of crisis (Chapter 4).

A majority are satisfied with administrative services (63.0%). More than half of respondents (51.1%) trust their government to use their personal data safely (Chapter 4), and 65.1% of respondents, on average, say they can find information about administrative processes easily (Chapter 5). Those who perceive information to be open and transparent also have higher levels of trust in government.

Despite these good outcomes, as countries fight to emerge from the largest health, economic and social crisis in decades, trust levels decreased in 2021 but remained slightly higher than in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis (OECD, 2021[12]). The Trust Survey finds public confidence is evenly split between people who say they trust their national government and those who do not. Data show that it takes a long time to rebuild trust when it is diminished; it took about a decade for trust to recover from the 2008 crisis. This is why countries urgently need to invest in re-establishing trust to tackle the policy challenges ahead.

Trust varies across institutions. The police (67.1%), courts (56.9%), and civil service (50.2%) and local government (46.9%) garner higher levels of public trust than national governments (41.4%) and national legislatures like congresses and parliaments (39.4%)

Governments can do better in responding to people’s concerns. Less than half of respondents, on average across countries, expect that their government would improve a poorly performing service, implement an innovative idea, or change a national policy in response to public demands (Chapter 4). Fewer than one-third of respondents believe that the government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation (Chapter 5).

Public perceptions of government integrity is an issue. Slightly less than half of respondents, on average across countries, think that a high-level political official would grant a political favour in exchange for the offer of a well-paid private sector job (Chapter 6). Around one-third say a public employee would accept money in exchange for speeding up access to a public service (Chapter 5).

Generational, educational, income, gender and regional gaps in trust illustrate that progress can be made in enhancing participation and representation for all. Young people, respondents with low levels of education, and those living on low incomes report lower levels of trust in government than other groups. Perceptions are important, too – trust in government is noticeably lower for people feeling a sense of financial insecurity or a lack of political voice (Chapter 3). Perhaps related to this, trust in even apolitical government institutions is much lower among those who did not vote for the parties in power than those who did, suggesting deeply embedded polarisation.

Strengthening confidence in government’s ability to address global challenges is a priority. Governments face new threats in the form of disinformation/misinformation, unequal opportunities for representation and participation, and intergenerational, global, and existential crises like climate change. While half of the respondents, on average across countries, think the government should be doing more to reduce their country contribution to climate change, only 35.5% of respondents are confident that countries will actually succeed in reducing their contribution to climate change (Chapter 6).

OECD Trust Survey data can help governments to deliver better. The Trust Survey provides for the first time a comprehensive view of people’s expectations and assessments of government across 22 OECD countries. These data provide actionable evidence for countries to see what works and what does not as they make efforts to strengthen public trust.

These results serve as a call to action for OECD governments. Governments must continue improving their reliability and preparedness for future crises, designing policies and public services with and for people, and enhancing transparency and communications to citizens around promises and results, as there is room for improvement and learning across and within countries in these areas.

Governments need to connect and engage better with citizens in policy design, delivery and reform; safeguard and enhance people’s ability to exercise effective political voice; ensure the integrity of elected officials; continuously measure and improve public service delivery; and ensure the inclusion of vulnerable and marginalised groups.

References

[1] Brezzi, M. et al. (2021), “An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 48, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6c5478c-en.

[14] Gaigg, V. (2021), “Mehr als 40.000 Teilnehmer und einige Festnahmen bei Demos gegen Corona-Maßnahmen in Wien”, Der Standard, https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000131661460/auch-dieses-wochenende-zig-demos-gegen-corona-massnahmen-und-impfpflicht (accessed on 9 March 2022).

[5] González, S. and C. Smith (2017), “The accuracy of measures of institutional trust in household surveys: Evidence from the oecd trust database”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2017/11, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d839bd50-en.

[15] Henley, J. (2021), “Violence in Belgium and Netherlands as Covid protests erupt across Europe”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/nov/21/netherlands-arrests-second-night-covid-protests (accessed on 9 March 2022).

[13] Kihara, L. and D. Leussink (2021), “Pandemic fatigue complicates Japan’s COVID fight, risks recovery delay”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pandemic-fatigue-complicates-japans-covid-fight-risks-recovery-delay-2021-08-18/ (accessed on 14 February 2022).

[9] Levi, M. and L. Stoker (2000), “Political Trust and Trustworthiness”, Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 3, pp. 475-508, https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.POLISCI.3.1.475.

[10] Norris, P. (2022), In praise of skepticism: Trust but verify, Oxford University Press, New York, https://www.pippanorris.com/forthcomingbooks (accessed on 11 February 2022).

[8] OECD (2022), Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Norway, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/81b01318-en.

[11] OECD (2021), “Building a New Paradigm for Public Trust”, Webinar Series, https://www.oecd.org/fr/gov/webinar-series-building-a-new-paradigm-for-public-trust.htm (accessed on 10 March 2022).

[7] OECD (2021), Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Finland, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/52600c9e-en.

[12] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Trustlab Initiative, https://www.oecd.org/wise/trustlab.htm (accessed on 9 March 2022).

[4] OECD (2017), OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278219-en.

[3] OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

[6] OECD/KDI (2018), Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308992-en.

Notes

← 1. Media articles on the extent of “pandemic fatigue” and protests against COVID-19 measures cover countries as varied as Austria (Gaigg, 2021[14]), Belgium, Japan (Kihara and Leussink, 2021[13]), the Netherlands (Henley, 2021[15]) and many other countries in which the survey was conducted.

← 2. Other factors, too, can influence trust at a specific point in time, such as the timing of a survey within a political/electoral cycle (e.g. start or end of government mandate) or current events. Austria, for example, had two federal chancellors sworn in between October and December 2021. This likely affected Austria’s results and complicates comparability. Portugal’s survey ran in early 2022, right after a national parliamentary election.

← 3. The results on trust in the national government roughly align with results found in other surveys, particularly in terms of country ordering. The OECD estimates of trust are slightly lower than in some other surveys because the OECD uses a “neutral” category in its continuous scale, rather than a dichotomous “trust”/”do not trust” response option.