1. Under pressure: Labour market and wage developments in OECD countries

The recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic lost momentum in 2022, with employment and unemployment stabilising. Labour markets remain tight, despite signs of easing. In this context, the quality of jobs on offer has improved in some dimensions, but real wages are falling significantly in almost all OECD countries despite a pick-up in nominal wage growth. In most countries, profits have grown robustly, often more than nominal wages. Nominal minimum wages are keeping pace with inflation, but any real gains may fade rapidly if inflation remains high. In contrast, wages negotiated in collective agreements between employers or employers’ organisations and trade unions are reacting with some delay even in countries where the majority of workers are covered by a collective agreement, although a catch-up phase is expected in the coming quarters.

Amid a cost-of-living crisis, the robust recovery from the COVID-19 recession lost momentum since 2022. The energy shock caused by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine put a drag on global growth and contributed to propelling price inflation in many countries to levels not seen in decades. However, OECD labour markets have proved resilient. Employment and unemployment have held their ground, and the labour market remains tight in most countries, despite some signs of easing. The past quarters have shown signs of improvements, with global GDP growth picking up slightly.

The latest available evidence at the time of writing suggests that:

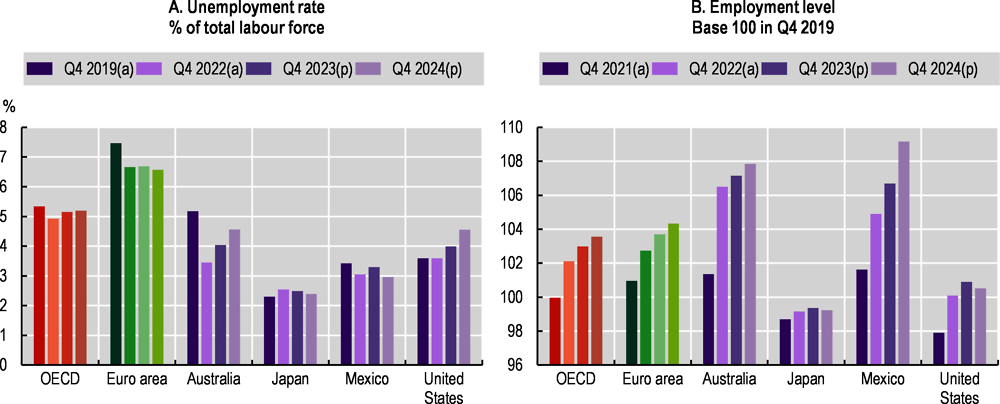

After stabilising in the second half of 2022, employment in the OECD area picked-up slightly in the first months of 2023. In May 2023, OECD-wide employment was about 3% higher than in December 2019. Unemployment rates across the OECD mostly remained below pre-crisis levels. A recent pick-up in growth has led to an improvement of the economic projections for the near future, but GDP growth is likely to remain subdued in 2023 and 2024. Over the same period of time, OECD-wide employment is projected to continue to expand and the unemployment rate to increase slightly.

Inactivity rates have declined relative to the pre- COVID-19 crisis in most countries. Early concerns that the pandemic might permanently increase inactivity rates have not come to pass, including among older adults. On average across all OECD countries, inactivity rates for 55 to 64 years old have decreased more than for the younger age groups. Inactivity rates for the whole working age population, however, are higher than before the crisis in seven OECD countries, with the largest increases found in Latin American member states.

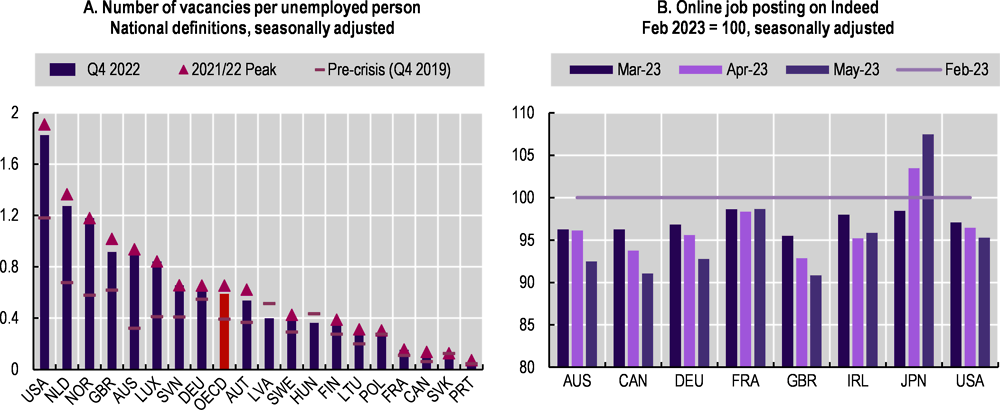

Labour markets remain tight even as pressures are easing. Labour market tightness (i.e. the number of vacancies per unemployed person) eased in the second half of 2022 but remained well above pre-crisis levels. Online job postings data for selected countries suggest that labour demand has continued to ease in the first half of 2023.

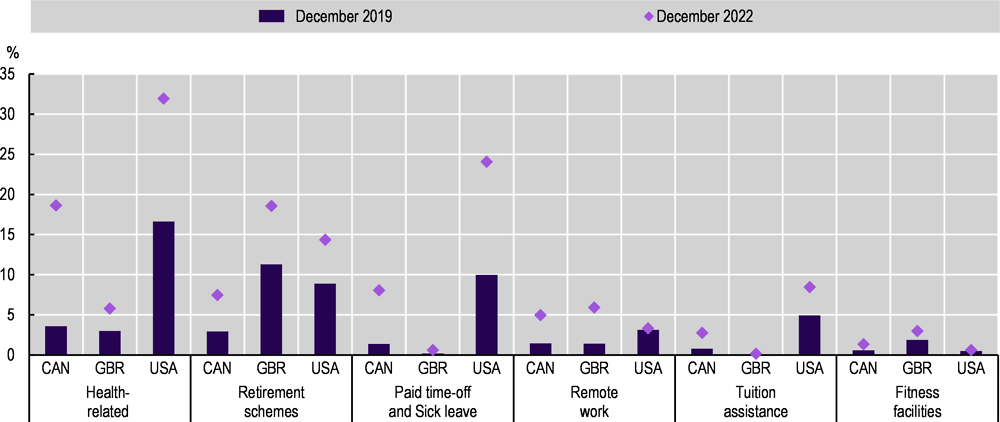

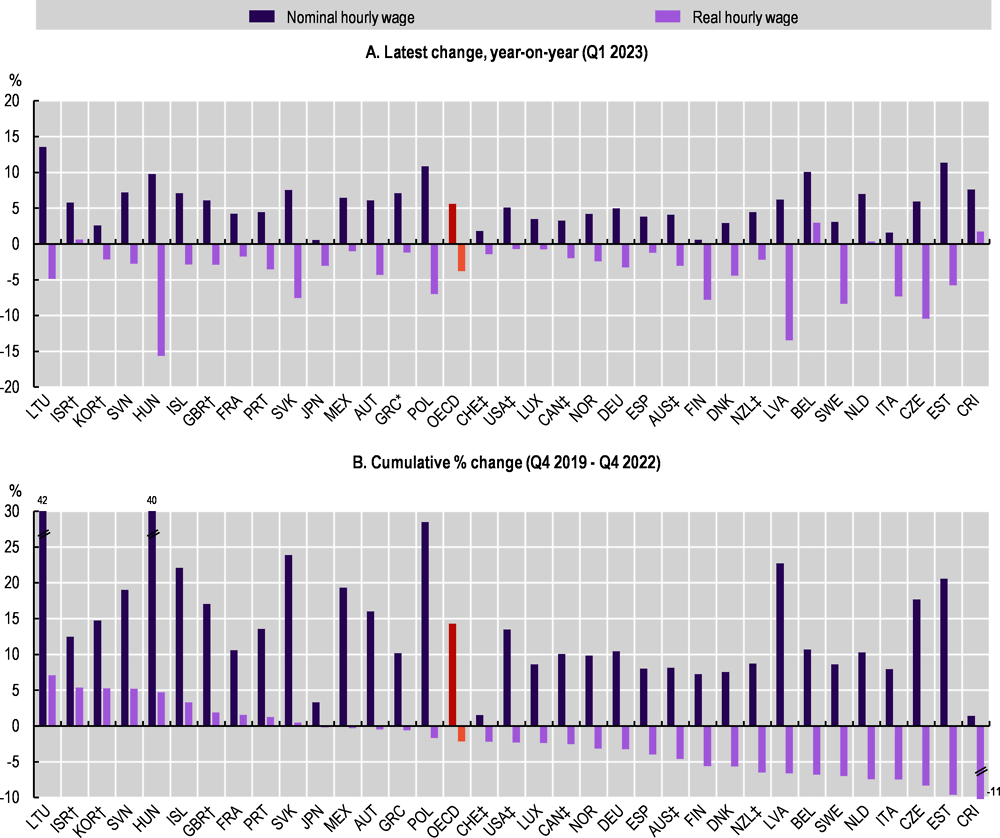

Amid tight labour markets, nominal wage growth has picked up and some non-monetary aspects of job quality have improved. In Q1 2023, nominal year-on-year wage growth exceeded its pre-crisis level in nearly all OECD countries, reaching 5.6% on average across the 34 countries with available data. Among new hires, the share of temporary contracts and involuntary part-time has declined in most OECD countries. In addition, data on online job postings in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States show an increase in the share of vacancies offering employee benefits, especially health-related benefits, retirement programs/schemes and paid time off.

As inflation reached levels not seen in decades in many countries, real hourly wages have fallen – often substantially – in virtually every industry and OECD country, contributing to the cost-of-living crisis. In Q1 2023, despite the pick-up in nominal wages, the difference between nominal annual wage growth and inflation was -3.8% on average across the 34 OECD countries with available data, with a negative difference observed in 30 countries. The loss of purchasing power is particularly challenging for workers in low-income households, who have less leeway to deal with increases in the cost of living through savings or borrowing and often face higher actual inflation rates because a higher proportion of their spending goes to energy and food.

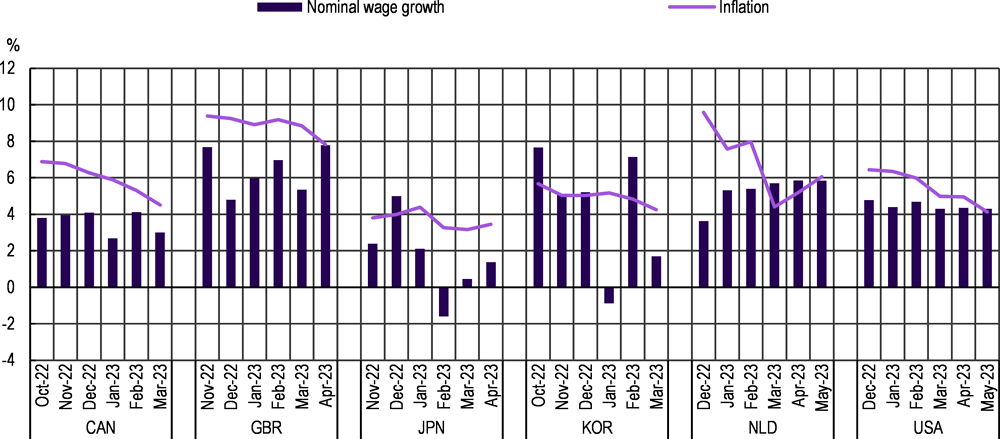

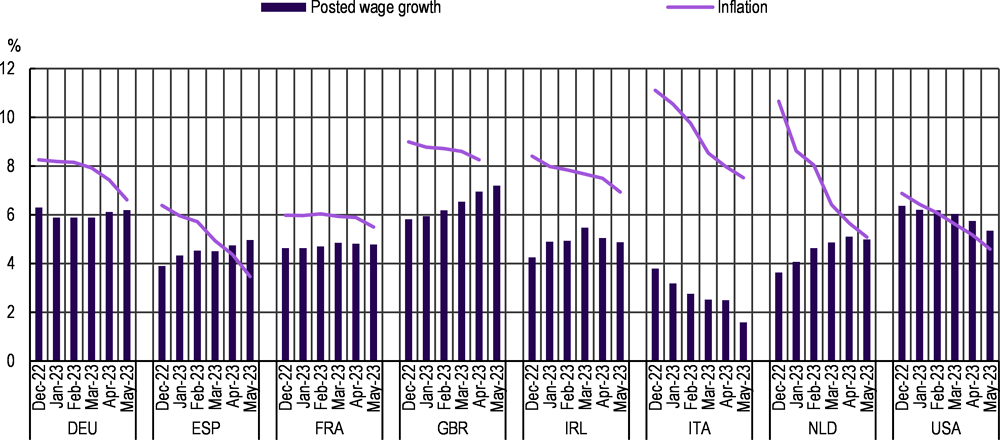

Nominal wage growth has not significantly accelerated in the first half of 2023, but the gap with declining inflation is narrowing in some countries. Recent wage data from five countries point to stable nominal wage growth in most in April and May 2023. Similarly, growth in wages posted on the online platform Indeed has been steady or declining in the first five months of 2023 in France, Germany, Ireland, Italy and the United States. In Spain, the Netherlands, and – more markedly – the United Kingdom nominal growth of posted wages has increased. In general, the gap between inflation and nominal wage growth in posted wages has become smaller. However, wages posted on Indeed have grown in real terms only in Spain and the United States in recent months.

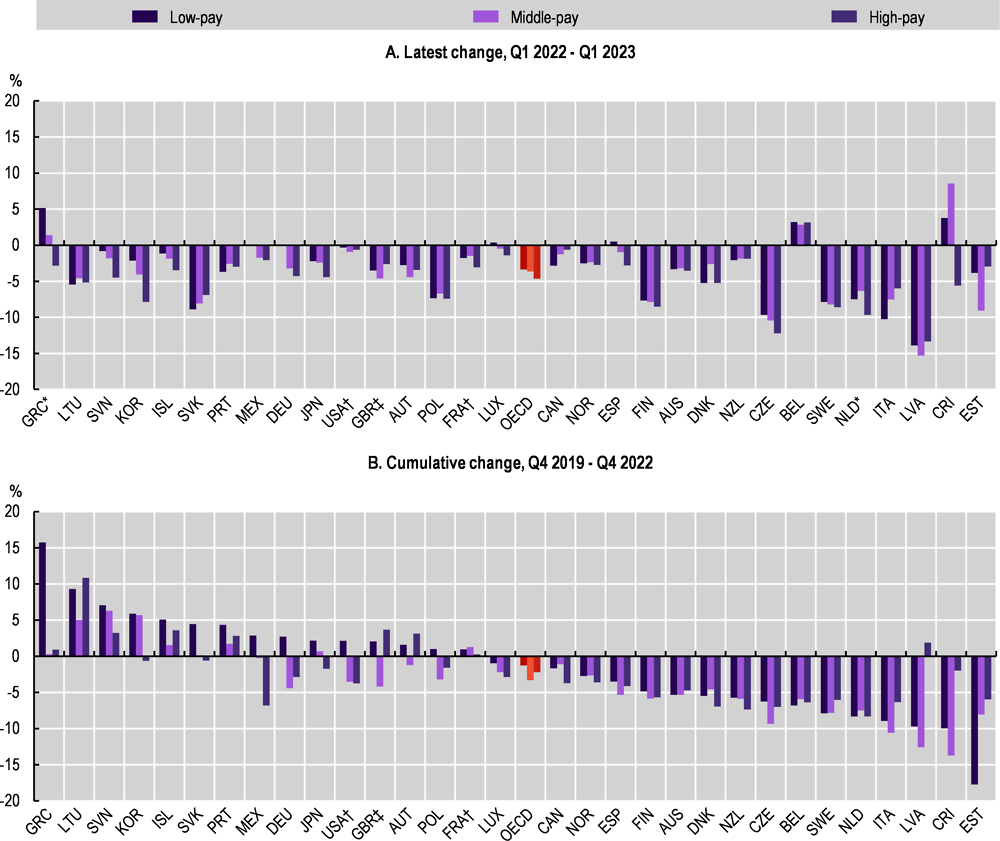

In many countries, real wages are falling across all industries, but less so in low-pay industries. Among the 31 countries with available data, in Q1 2023, real wages in low-pay industries performed better than those in mid-pay industries in 18 countries, and better than those in high-pay industries in 22 countries. Real wages in low-pay industries had a worse performance than real wages in both mid- and high-pay industries only in six countries.

In most countries, profits have increased more than labour costs, making an unusually large contribution to domestic price pressures, and leading to a fall in the labour share. Data from Europe and Australia indicate that this has occurred not only in energy sectors, but also in other parts of the economy, including in accommodation and food and manufacturing. As economies re-opened, pent-up demand and large recovery plans bolstered aggregate demand, helping profits grow quickly while supply bottlenecks limited the speed of adjustment of output. With strong consumer demand and rapidly evolving inflation driven by external factors, many producers were likely able to adjust prices quickly, while wage increases typically involve longer renegotiations periods.

Several policy levers can be activated to limit the impact of inflation on workers and ensure a fair sharing of the cost-of-living crisis between taxpayers (through government taxes), companies, and workers. The most direct way to help workers is via an increase in their wages. Wage setting institutions – including minimum wages and collective bargaining – can help mitigate losses in purchasing power and ensure a fair distribution of the cost of inflation between firms and workers, while avoiding a price-wage spiral. The latest available evidence and information from a policy questionnaire addressed to Labour Ministries and social partners across OECD countries suggests that:

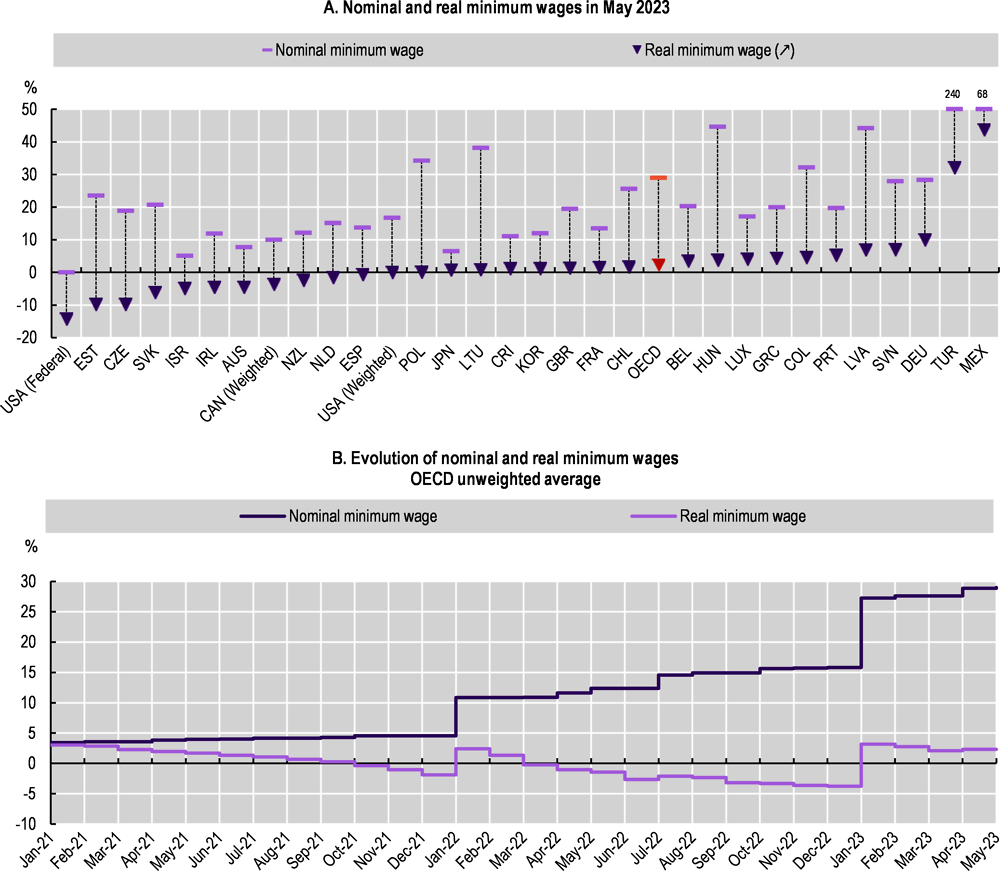

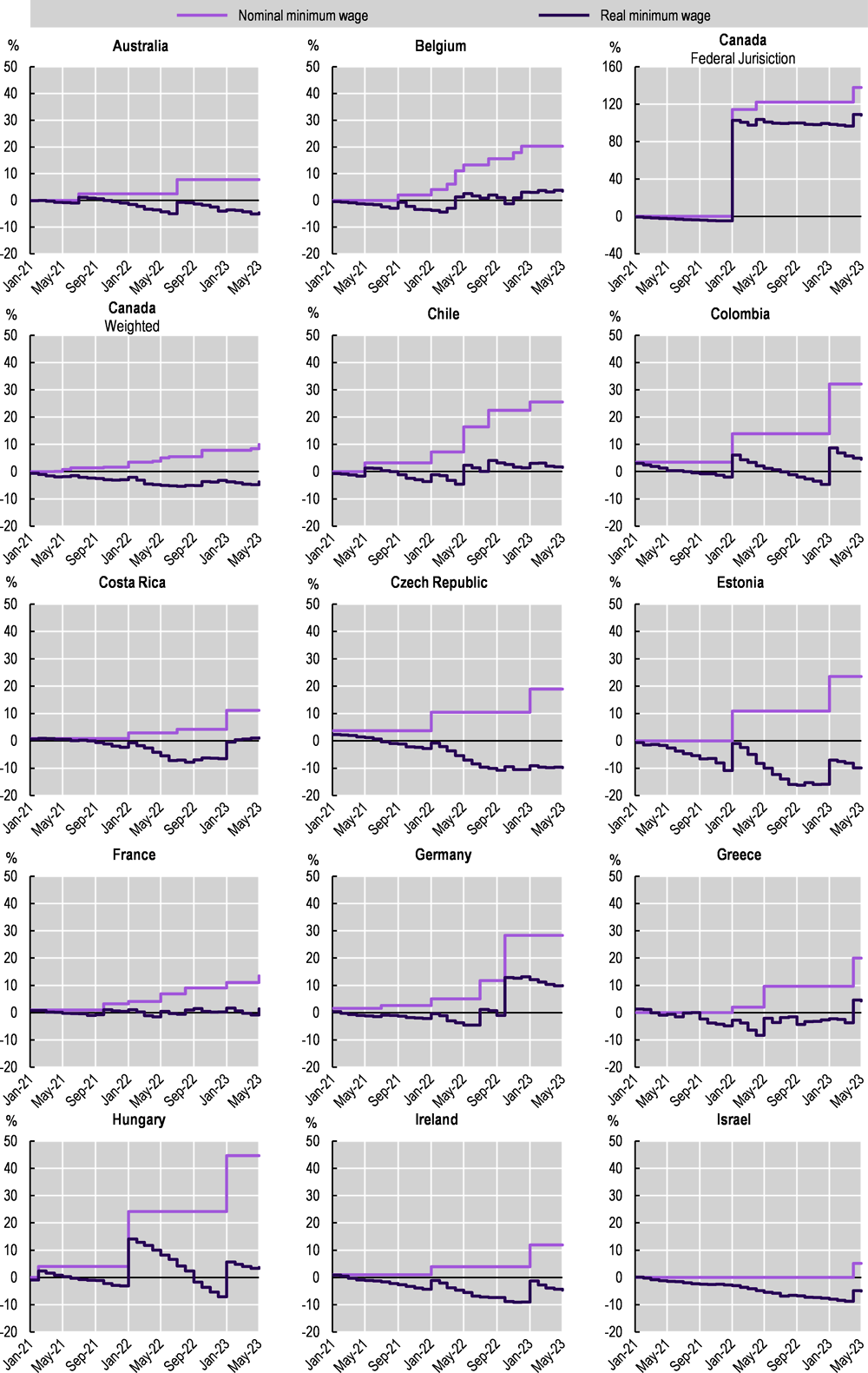

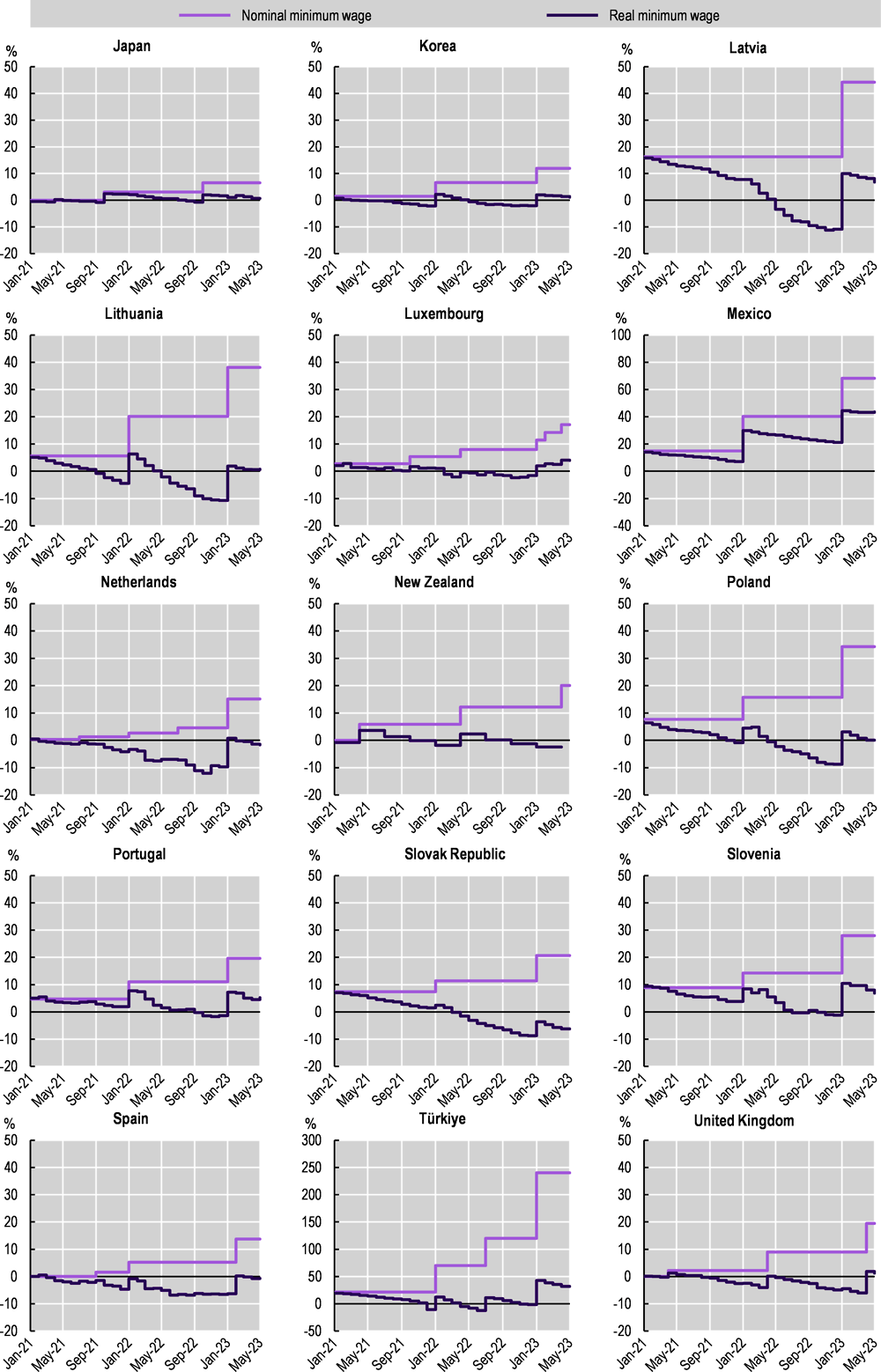

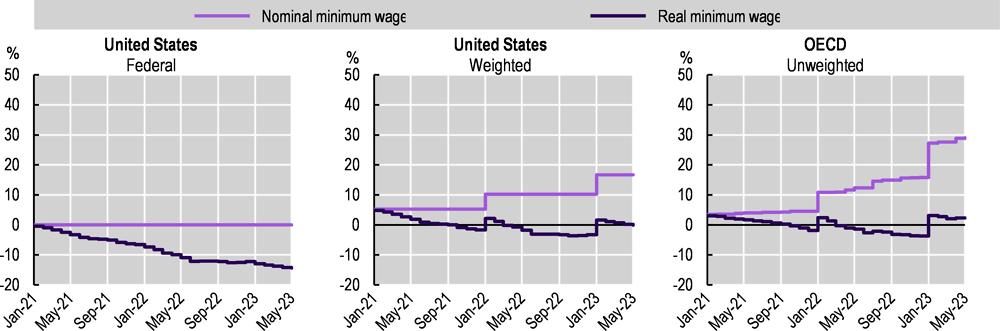

Between December 2020 and May 2023, on average across OECD countries, nominal statutory minimum wages have increased by 29%. This trend has allowed minimum wages to keep pace with inflation (prices increased by 24.6%, on average, over the same time period), even if real gains tend to be quickly eroded as inflation remains high. Going forward, it is important to ensure that statutory minimum wages continue to adjust regularly through the different national institutional settings and uprating mechanisms. There is a concern that increases in the minimum wage contribute to fuel inflation. However, the effect of minimum wage increase to the growth in aggregate wages is limited, even accounting for spillover effects on wages above the minimum.

In most OECD countries, increases in the minimum wage are the result of a discretionary policy decision that is typically taken once a year at most, while in six countries the national statutory minimum wage is automatically indexed to inflation. Automatic indexation helps to safeguard the purchasing power of minimum wage earners and improve the predictability of future increases. However, it also reduces the scope for governments, social partners or commissions to exercise judgement on future increases and could lead to an excessive compression of the wage distribution if other wages are not raised, with consequences both for individual careers, and for the design of redistribution policies.

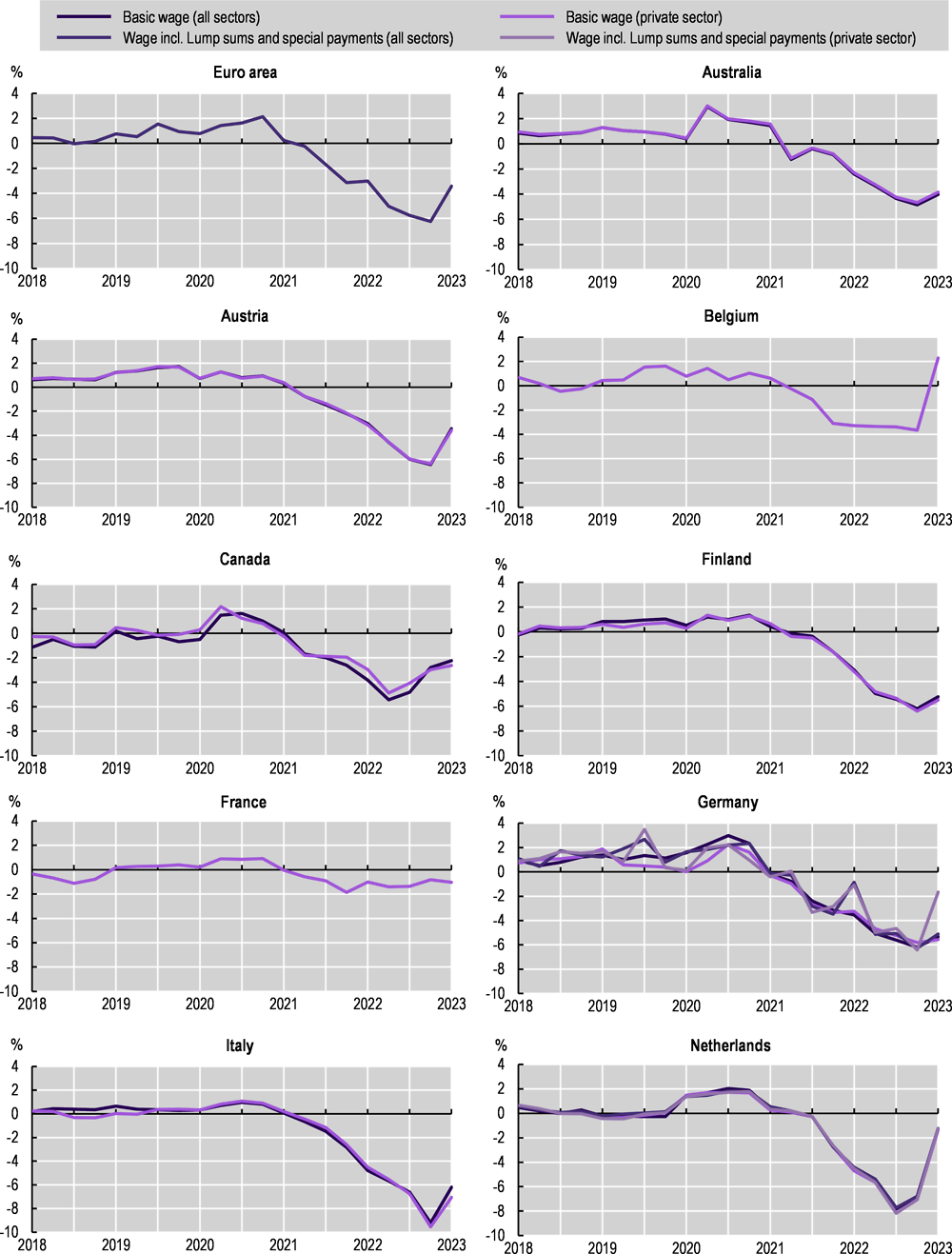

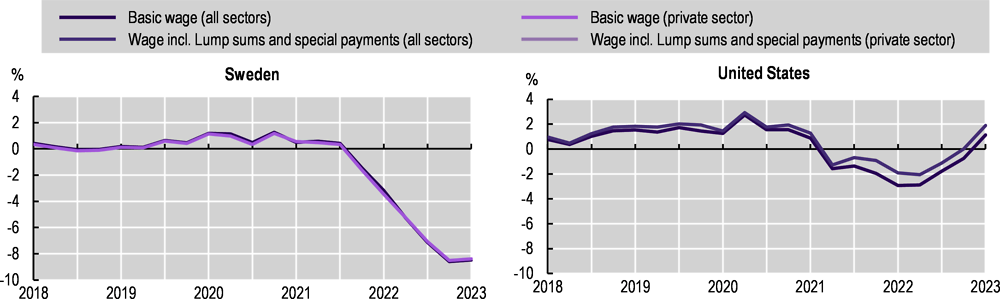

Wages negotiated in collective agreements between firms and workers have declined in real terms and are reacting with longer delays. Several factors can explain why negotiated wages, on average, have not managed to keep up with inflation. Most importantly, the staggered and rather infrequent nature of wage agreements means that negotiated wages rarely adjust immediately to unexpected price inflation. However, in some OECD countries, unions, employers’ organisations and governments have found innovative ways to cushion the effects of inflation while limiting the costs for firms by using tax-free lump-sum bonuses or non-wage benefits.

Faster growth in negotiated wages is likely in the coming quarters as the most recent bargaining rounds have tried to recoup some of the losses in purchasing power. However, the available evidence suggests that, after a catch-up phase, nominal negotiated wage growth are likely to go back to previous trends without generating a price-wage spiral. Overall, aggregate nominal wage growth is projected to be just over 4% in the OECD area in 2023, before moderating to around 3.5% in 2024 while inflation is projected to be at 6.6% in 2023 and 4.3% in 2024.

Minimum wages and collective bargaining can help achieve a fair distribution of the cost of inflation between workers and employers, as well as across workers of different pay levels. A fair sharing of the cost of inflation can prevent further increases in inequality and support effective monetary policy by averting feedback loops between profits, wages and prices. The analysis of this chapter suggests that, in several sectors and countries, there is room for profits to absorb some further increases in wages to mitigate the loss of purchasing power at least for the low paid without generating significant additional price pressures. Given the downward rigidity of prices, the recent decline in input costs will also likely provide further room to absorb some wage increases without generating inflationary pressures. Collective bargaining can also help identify solutions tailored to firms’ varying ability to sustain increase in wages – for instance for small and medium firms that may face more significant constraints.

This chapter offers a detailed overview of recent labour market developments across the OECD countries with a particular focus on wage dynamics and discusses the policy measures that countries have at their disposal to help address the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, focusing on wage policies. This includes a discussion on the role that minimum wages and collective bargaining have played so far in cushioning the costs of inflation, drawing on a policy questionnaire that was addressed to OECD countries as well as employers’ organisations and trade unions through, respectively, the Business@OECD (BIAC) and the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC) networks.

The chapter is organised as follows: Section 1.1 reviews recent labour market developments across the OECD; Section 1.2 reports on recent wage developments; and finally Section 1.3 discusses the role of statutory minimum wages and collective bargaining as a policy lever to support workers and ensure a fair burden-sharing of the cost of inflation among governments, firms and workers. Section 1.4 concludes with policy recommendations.

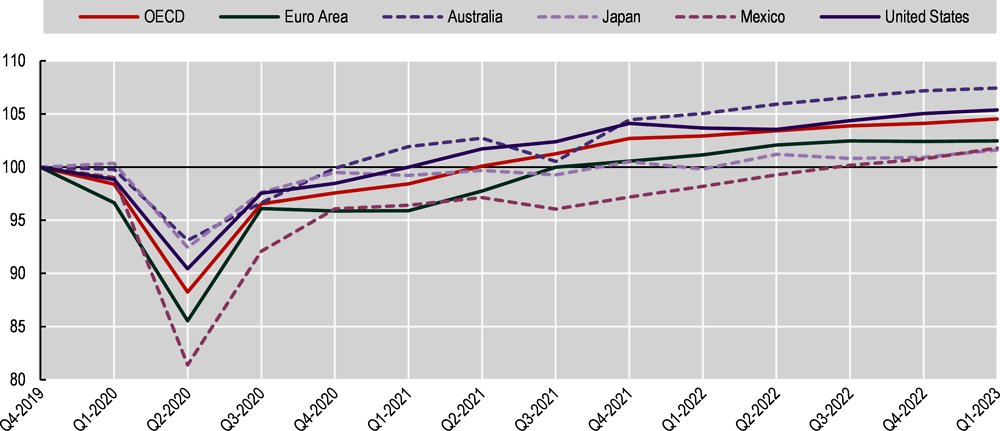

Growth across the OECD slowed substantially over the course of 2022, but there are signs of improvement in 2023 (Figure 1.1). Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine pushed up prices substantially, especially for energy and food, adding to inflationary pressures at a time when the cost of living was already rising rapidly around the world. Inflation eroded household incomes and monetary policy tightened considerably amidst the unusually vigorous and widespread steps to raise policy interest rates by central banks in recent months (OECD, 2022[1]). By the fourth quarter of 2022, global growth had slowed to an annualised rate of just 2%, with growth over the year falling to 2.3%, just over half the pace seen through 2021. Output declined in 15 OECD economies in the fourth quarter, with most of these in Europe. The recent decline in energy prices and the improving prospects for China have contributed to an uptake in economic indicators in the first half of 2023, with global GDP growth picking up to an annualised rate of just over 3% in the first quarter, despite mixed outcomes across countries and particularly weak growth in the Euro Area (OECD, 2023[2]). In the first quarter of 2023, GDP for the OECD area stood 5% above its level at the end of 2019, after a year-on-year growth of 1.5% (Figure 1.1).

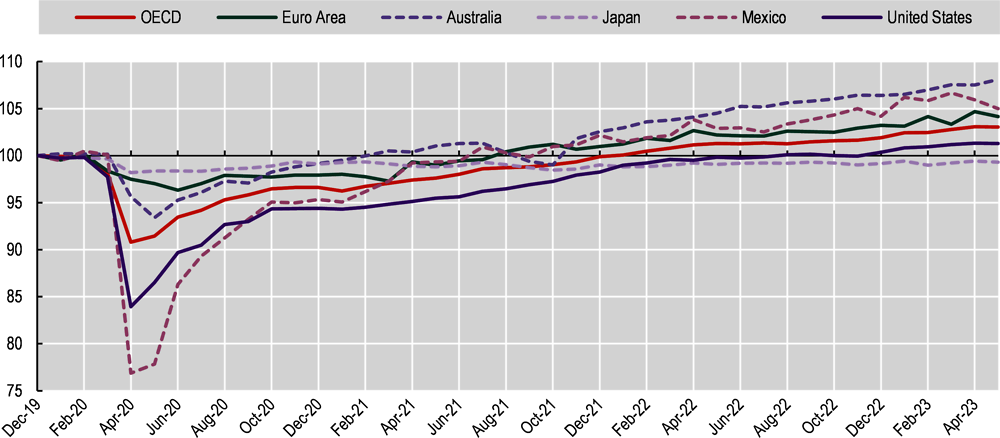

Amid the slowdown in economic growth, employment growth also lost momentum over the course of 2022 but continued to grow in the first months of 2023 (Figure 1.2). In May 2023, total employment for the OECD, was about 3% higher than in December 2019. Overall, employment growth since the start of the pandemic was slightly stronger for women than men (see Box 1.1). Employment rates across most OECD countries also stabilised above pre-crisis levels by the first quarter of 2023 (Annex Figure 1.A.1).

The initial labour market impact of the pandemic was stronger among women than men in most OECD countries, raising the concern that the pandemic-induced recession might be a “shecession” (OECD, 2020[3]). However, as economies reopened, in most OECD countries women benefitted more than men from the rebound in economic activity. Indeed, in early 2022 – two years after the onset of the pandemic – the employment rate gap between men and women had declined in most of the OECD countries relative to its pre-pandemic level (Salvatori, 2022[4]).

Over the course of 2022 and the first half of 2023, employment levels for both women and men stabilised above pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1.3). By May 2023, on average across the OECD, women’s total employment had grown about 1 percentage point more than men’s, reaching 3.5% above its pre-crisis level.

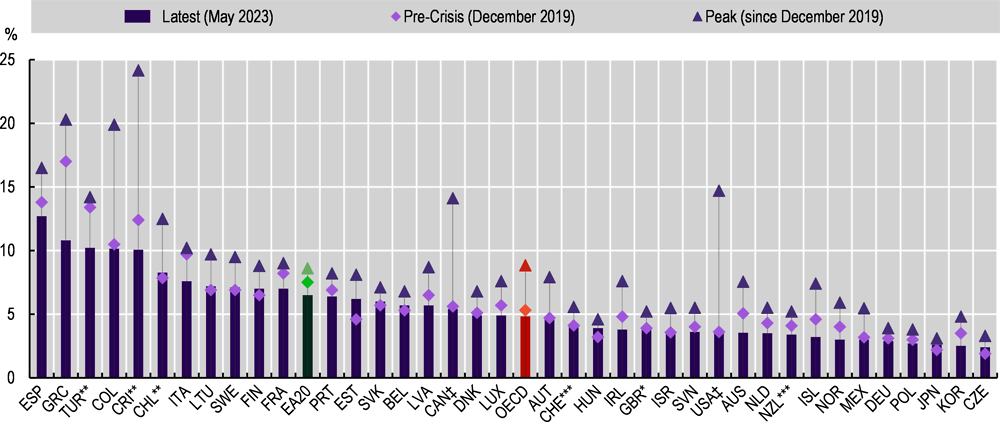

Similarly, unemployment rates across the OECD held their ground as the year ended, mostly remaining below pre-crisis levels (Figure 1.4). The average unemployment rate for the OECD stood at 4.8% in May 2023 – or half a percentage point below its pre-crisis levels. In May 2023, the unemployment rate indeed exceeded its pre-crisis levels by at least half a percentage point only in four countries – with the maximum difference of 1.6 percentage points recorded in Estonia.

1.1.1. Inactivity rates have generally declined but average hours worked are slightly below pre-crisis levels in several countries

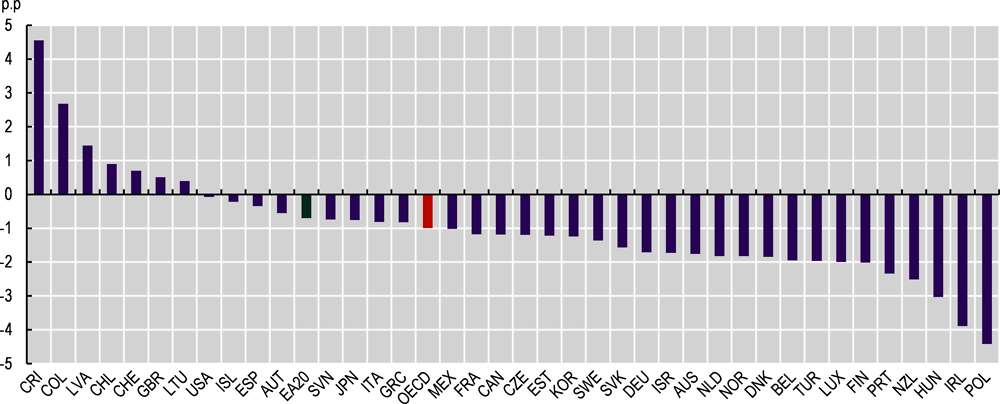

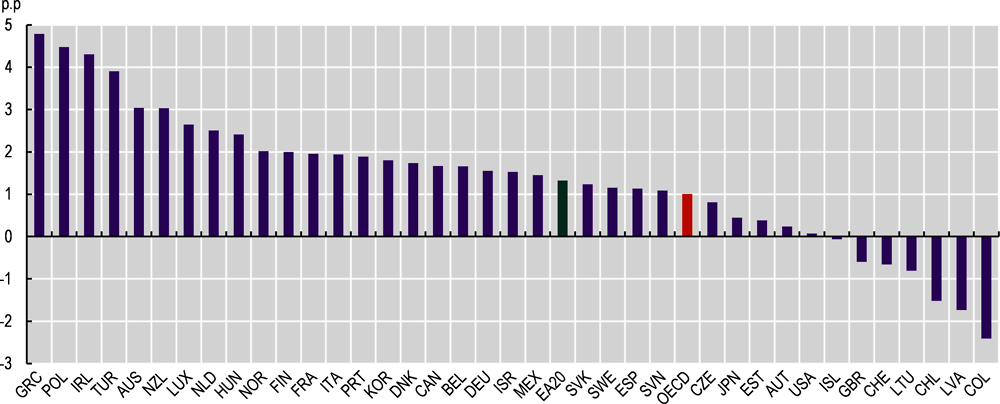

Inactivity rates among the working age population are below pre-crisis levels in most countries, pointing to a recovery of labour supply from the initial decline at the start of the COVID-19 crisis. As of Q1 2023, inactivity rates were at or below pre-crisis levels in 31 countries, with an average decline across all countries of just under 1 percentage point. Inactivity rates were at least 1 percentage point above pre-crisis levels only in Colombia, Costa Rica and Latvia.1

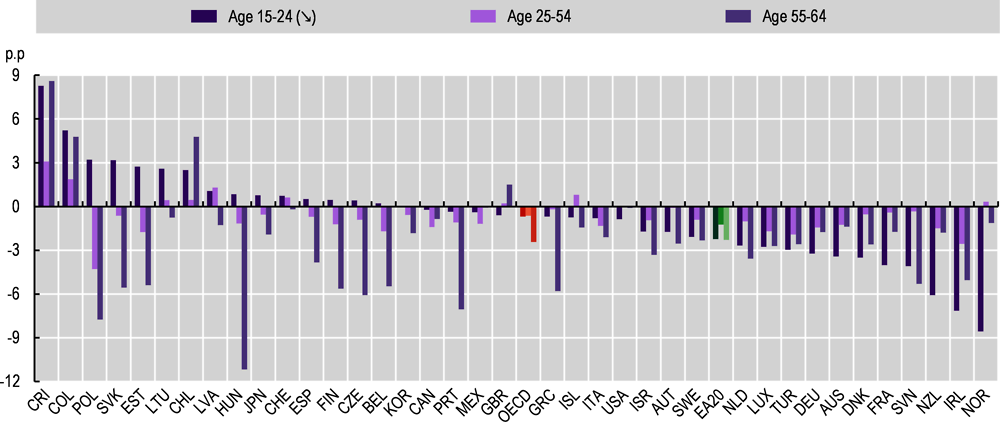

Inactivity rates have generally decreased among older adults as well, despite earlier concerns that the pandemic might induce a permanent reduction in the labour supply of this group. In fact, on average across all OECD countries, by Q1 2023, the inactivity rate for individuals aged 55 to 64 had decreased relative to pre-crisis levels more than for those aged 25 to 54 (-2.5 vs -0.6 percentage points) (Annex Figure 1.A.2). More broadly, there is little indication that the pandemic induced an increase in retirement of older workers across countries. While some earlier evidence for the United States suggested that this might have been the case (Faria-e-Castro, 2021[5]), more recent data point to a limited impact (Thompson, 2022[6]). In addition, there is no indication of significant increases in retirement in the United Kingdom (Murphy and Thwaites, 2023[7]), the Euro Area (Botelho and Weißler, 2022[8]) or Australia (Agarwal and Bishop, 2022[9]).

Hours worked per employed person are below pre-crisis levels in most countries with recent data available (Figure 1.6). The persistence of lower hours worked in tight labour markets does raise the question as to whether the COVID-19 crisis might have led to some structural changes, for example in workers’ preferences over work-life balance. However, the differences are generally small. In Q4 2022, hours worked per employed person were above pre-crisis levels or below that level by less than 2% in 22 of the 30 countries with recent data available. On average, hours worked per employed person were down by just under -1%. In Latvia, New Zealand, Slovenia and Poland they had increased by more than 2%, while they had decreased by more than 4% in Ireland, the Slovak Republic, Portugal, Austria and Korea. The relatively large decline in hours per employed in Korea is due to the progressive lowering of the statutory limit on total weekly working hours from 68 to 52 (Carcillo, Hijzen and Thewissen, 2023[10]).

1.1.2. Labour markets remain tight even as there are signs that pressure is easing

After the sharp increase in vacancies in 2021 amid the unprecedented rebound of economic activity, labour market tightness (i.e. the number of vacancies per unemployed person) peaked in the first half of 2022 in many OECD countries (Figure 1.7, Panel A). Among the 19 countries with data available, the increase in tightness in 2021 was particularly large in English speaking countries, but also in Norway and the Netherlands.2 By the end of 2022, labour market tightness was mostly below its peak levels but generally remained significantly higher than before the COVID-19 crisis.

Data on job postings on the online platform Indeed suggest a continued easing over more recent months in the majority of countries (Figure 1.7, Panel B). Online job postings declined in the first five months of 2023 in Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. The largest decline occurred in the United Kingdom (-10% in May 2023 relative to February 2023). In France, online job postings declined at the start of the year and stabilised in the three months leading to May 2023. Japan is the only country among those with available data where online job postings increased steadily in the first half of 2023. In New Zealand, the official index of online job vacancies fell 9.9% in the year to March 2023.3

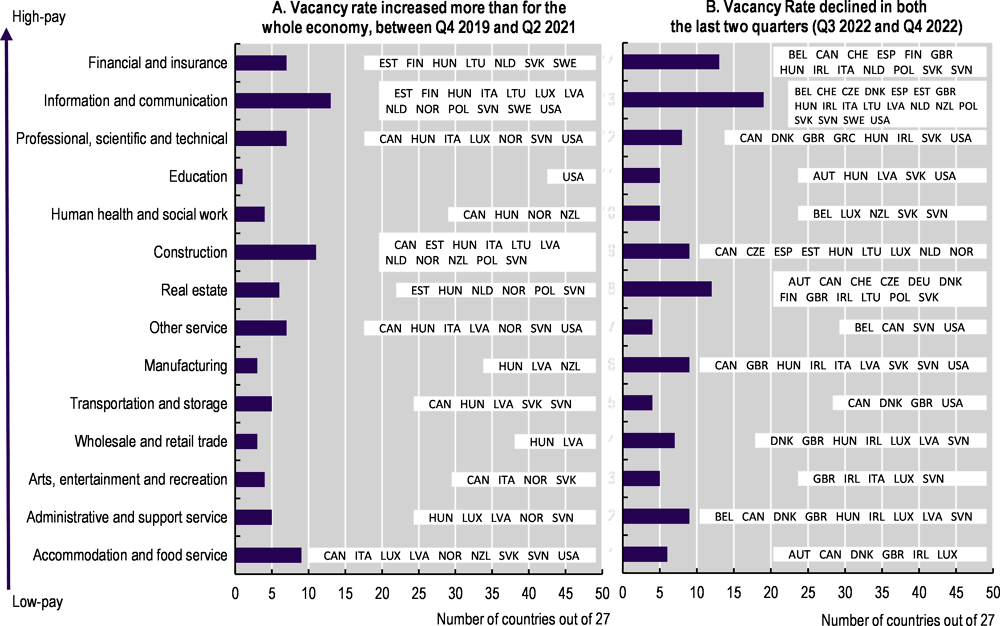

Imbalances between labour demand and supply have been widespread across industries. Vacancy rates capture the fraction of all available jobs that are unfilled and for which employers state that they are actively trying to recruit. Panel A of Figure 1.8 provides an overview of the number of countries (out of the 27 with available data) in which a specific industry experienced an increase in vacancy rates larger than the country average. The three industries most likely to have seen relatively larger increases in vacancy rates cut across the pay ranking are “Information and Communication” (13 countries), Construction (11 countries), and “Accommodation and Food Services” (9 countries).

Vacancy rates declined in the last two quarters of 2022 in many industries across countries (Panel B of Figure 1.8). Declines in vacancy rates have been particularly frequent across countries in “Finance and insurance” (13 countries) and “Information and communication” (19 countries) – two high-pay service sectors. Other industries with frequent declines in vacancy rates across countries are found across the pay rank, and include construction, manufacturing and “administrative and support services” (9 countries each).

Numerous factors contribute to differences in the dynamics of labour market tightness between countries. On the demand side, the initial strength of the economic rebound and the intensity of the slowdown differed depending on the composition of the economy, exposure to the energy crisis, and timing of the tightening of monetary policy. On the supply side, while labour market participation is back to pre-crisis levels in most countries (see above), the speed of its recovery varied. Notably, labour force participation lagged behind in two of the largest OECD economies – the United States and the United Kingdom – which also experienced some of the largest increases in labour market tightness. The European Central Bank (2023[11]) attributes part of the higher labour market tightness in the United States relative to the Euro Area to the slower recovery of labour supply.

As the COVID-19 crisis began, there was a concern that the crisis would create mismatches between labour supply and demand due to its differential impact across industries (Salvatori, 2022[4]). However, studies have found that the initial increase in mismatch was short-lived and smaller than during the Global Financial Crisis (Pizzinelli and Shibata, 2023[12]; Duval et al., 2022[13]). During the recovery, labour demand increased across sectors and countries, with no significant changes in sectoral composition. Some evidence suggests that workers redirected job searches away from affected occupations but not industries (Carrillo-Tudela et al., 2023[14]; Hensvik, Le Barbanchon and Rathelot, 2021[15]).

In some countries, quits increased as workers reaped the benefits of tight labour markets

Workers have taken advantage of tight labour markets to improve their working conditions, leading to an uptake in quits and job mobility in several countries. In the United States, quits in non-farm employment increased to their highest levels since the start of series in 2000. After a peak in December 2021, the quit rate (i.e. quits as percentage of total employment) returned to pre-crisis levels in April 2023.4 Initial concerns that this wave of resignations might be eroding the labour force have not come to pass as participation rates in the United States have continued to increase. Instead, the increase in quits is linked to an improvement in working conditions especially for younger and less-educated workers (Autor, Dube and McGrew, 2023[16]). In addition, historical evidence from manufacturing, indicate that the recent surge in quits was not unprecedented since waves of job quits have occurred during all fast recoveries in the post-war period in the United States (Hobijn, 2022[17]).

Similarly, evidence from France indicates that the increase in quits in 2022 was large but not unprecedented and did not erode the labour force, as over 80% of those who quit were employed within six months. Evidence from early 2022, indicates that amid the recruiting difficulties and the increase in workers’ mobility, some firms have made attempts to improve working conditions or allow more flexibility in the organisation of work (Lagouge, Ramajo and Barry, 2022[18]). Similar results also hold for Italy (Armillei, 2023[19]). In the United Kingdom, job-to-job transitions reached a record high at the end of 2021, and then declined slightly over the course of 2022, but in Q4 2022 they were still 10% higher than in the same quarter of 2019.5 By contrast, there is little indication of an increase in quits in Australia, as the proportion of businesses with open vacancies reporting the need to replace leaving employees was stable just under 80% over the course of 2021 and 2022.6

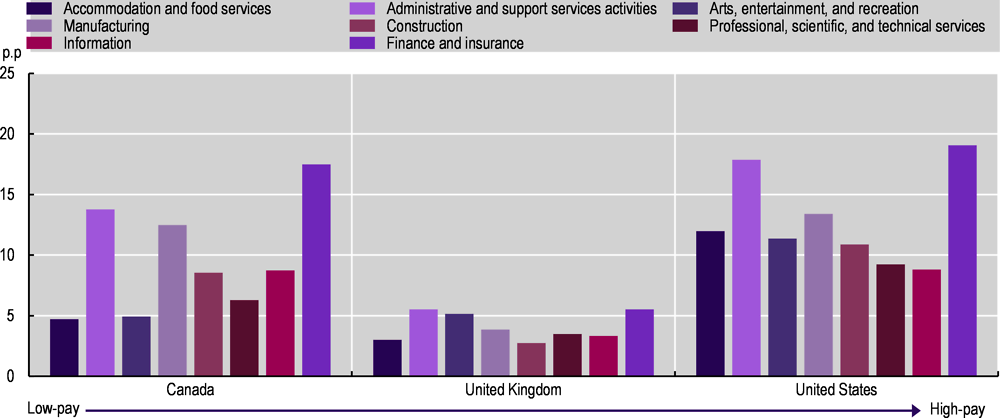

Amid tight labour markets, online job postings have offered benefits more frequently while temporary contracts and involuntary part-time have decreased among new hires

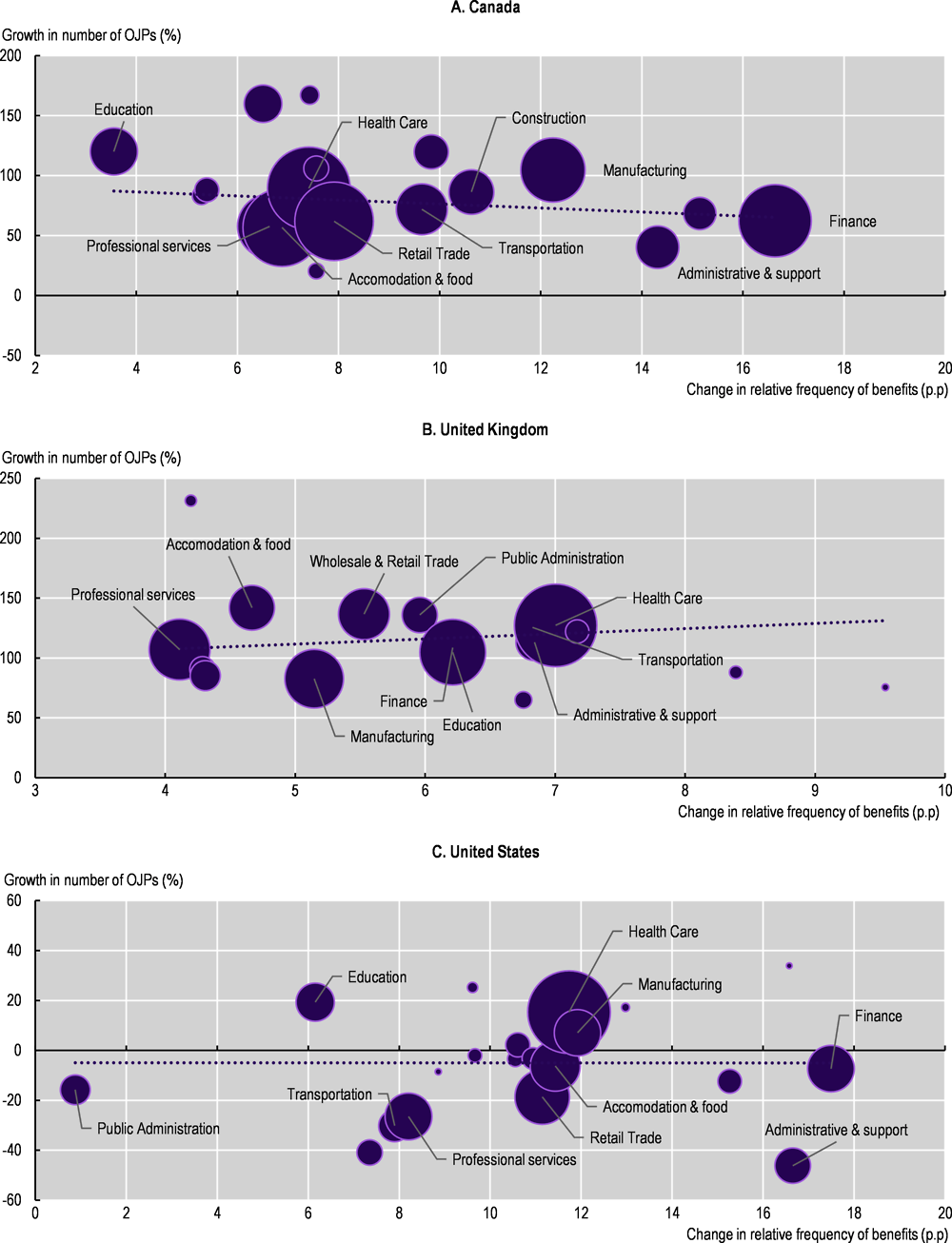

Amid tight labour markets, the share of online job postings offering job benefits has increased in several countries.7 Between December 2019 and December 2022, the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom saw an increase in the share of online job postings offering employee benefits, especially health-related benefits (including dental, vision and life insurance), retirement programs/schemes and paid time off (Figure 1.9).8 The fraction of job postings offering health-related benefits increased in particular in the United States and Canada, by 24 and 11 percentage points respectively. The mention of retirement benefits increased the most in the United Kingdom (+15 percentage points), while the share of job postings offering paid time off or sick leave increased by 17 percentage points in the United States. There were also significant increases in the mention of tuition assistance in Canada and the United States, and small increases in the mention of fitness facilities in all three countries analysed.

The increase in benefit offerings coincided with the sharp increase in labour market tightness described above. While this suggests that workers overall might have benefitted from the tight labour markets of the last year, additional analysis find no indication that benefit offerings increased more in industries where the growth in labour demand (as proxied by the growth in the number of job postings) was stronger (see Annex 1.B).9 The increase in benefit offers also appear to affect industries regardless of their pay level.

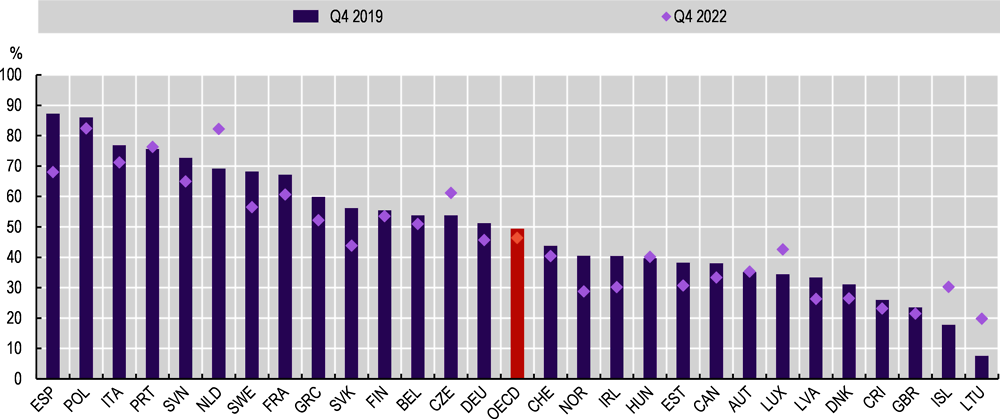

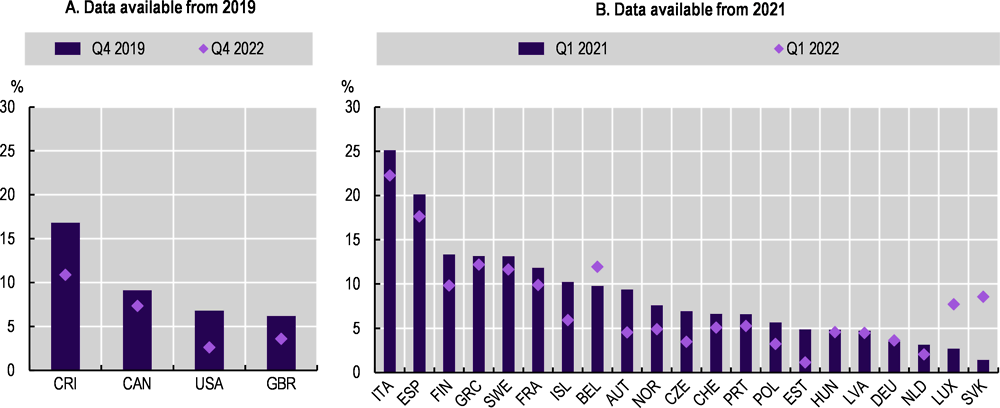

Amid the tight labour markets, the number of temporary contracts and of workers in involuntary part-time jobs have declined among new hires, suggesting an improvement in the working conditions of this group.10 In Q4 2022, the share of new hires on temporary contracts was lower than in Q4 2019 in 20 of the 28 countries with data available – despite the strong economic cycle in both periods (Figure 1.10). On average, the share of new hires on temporary contracts declined from 49% to 46%. The largest proportional declines were recorded in Norway, Spain, Sweden, the Slovak Republic and Ireland, while Lithuania and Iceland saw an increase in the share of new hires on temporary contracts although from initially low levels. Involuntary part-time among new hires declined between Q4 2019 and Q4 2022 in Canada, Costa Rica, the United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 1.11, Panel A). Similarly, in European countries, involuntary part-time among new hires declined in 18 of the 21 countries with data available between Q1 2021 and Q1 2022 (Figure 1.11, Panel B).11

1.1.3. Economic growth in the OECD is expected to remain subdued in 2023 and 2024, with moderate employment growth and a small increase in unemployment

Despite the signs of improvement seen in the early months of 2023, the outlook is for a period of subdued growth and persisting inflation.12 The full effects of the tightening of monetary policy since the start of 2022 are likely to appear over the course of 2023 and early 2024, particularly on private investment. Annual OECD GDP growth is projected to be below trend at 1.4% in both 2023 and 2024, although it will gradually pick up on a quarterly basis through 2024 as inflation moderates and real income growth strengthens. Helped by the decline in energy prices over the past few months, average annual headline inflation in the OECD as a whole is now projected to fall relatively quickly from 9.4% in 2022 to 6.6% in 2023 and 4.3% in 2024, with year-on-year inflation in the last quarter of 2024 down to 3.8%.

OECD-wide employment is projected to keep expanding in 2023-24 (Figure 1.12) and the unemployment rate to rise only marginally, especially in the Euro Area. The OECD-wide unemployment rate is expected to increase from 4.9% at the end of 2022 to 5.2% in the fourth quarter of 2024 (Figure 1.12), though with relatively large rises of around 0.75 percentage point or more in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Significant uncertainty about economic prospects remains, and the major risks to the projections are on the downside. One key concern is that inflation could continue to be more persistent than expected requiring tighter monetary policy for longer. In addition, the impact on economic growth could be stronger than expected if tighter financial conditions were to trigger stress in the financial system and undermine financial stability. Another key downside risk to the outlook relates to the uncertain course of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the associated risks of renewed disruptions in global energy and food markets. On the upside, reduced uncertainty from an early end to the war, easier-than-expected financial conditions, more robust labour force growth, and greater use of accumulated savings by households and businesses would all improve growth and investment prospects.

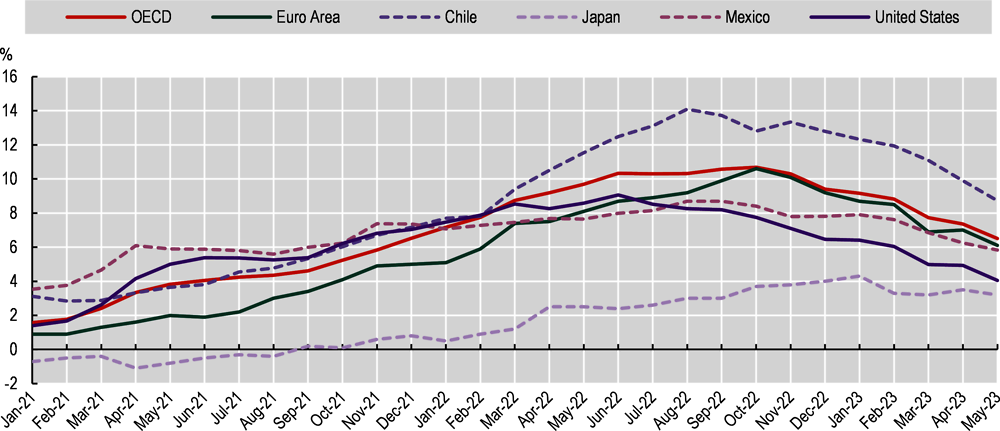

The COVID-19 crisis was followed by a large surge in prices. Prices began to increase in 2021 due to the rapid rebound from the pandemic and related supply chain bottlenecks (Figure 1.13). Then, over the course of 2022, the impact on energy prices of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine pushed inflation to levels not seen for decades in most countries. Inflation was initially mostly imported and driven by input and energy prices (OECD, 2022[1]), but, over the course of 2022, it became more broad-based with higher costs increasingly being passed through into the prices of goods and services (OECD, 2022[1]).13

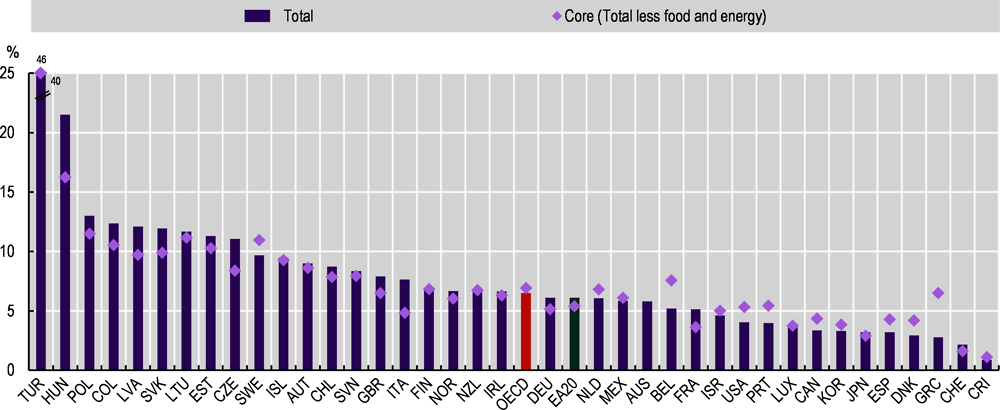

Inflation for the OECD area increased rapidly from below 2% at the start of 2021 to a peak of 10.7% in October 2022 and then fell to 6.5% in May 2023 – the last observation available at the time of writing. As of May 2023, inflation remained above 10% in nine OECD countries. Differences in total inflation across countries tended to be larger than differences in core inflation (see Figure 1.14), reflecting the differential exposure of countries to the increases in energy prices. Because of their higher vulnerability to the increase of energy prices, total inflation was particularly high in countries in Central and Eastern Europe. In general, however, amongst OECD countries, inflation was higher in Europe and South America, while it remained at relatively low levels in Korea and Japan (3.3% and 3.2% respectively).

1.2.1. Low-income households often face higher effective inflation rates and have less leeway to absorb increases in the cost of living

In most countries, low-income households have faced a higher effective inflation rate because a higher proportion of their spending goes towards energy and food which drove most of the initial increase in inflation.14 Similarly, there is evidence that rural households have suffered more in several countries because energy and fuel account for a larger share of their total expenditures (Causa et al., 2022[20]). In general, however, as inflation becomes more broad-based, differences in effective inflation rates across different households or groups with different consumption patterns become less pronounced.

However, low-income households have less leeway to absorb increases in cost of living even when facing effective inflation rates like those of other households. First, low-income households might have less room to substitute for lower-price alternatives if they are already buying cheaper versions of a given item.15 Second, low-income households typically can rely less on savings or borrowing to buffer the increase in cost of living (Charalampakis et al., 2022[21]; The German Council of Economic Experts, 2022[22]).16

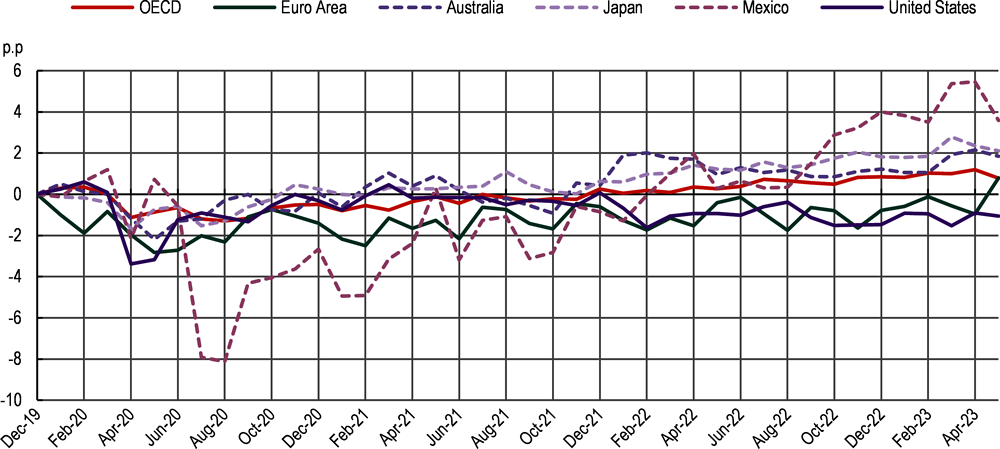

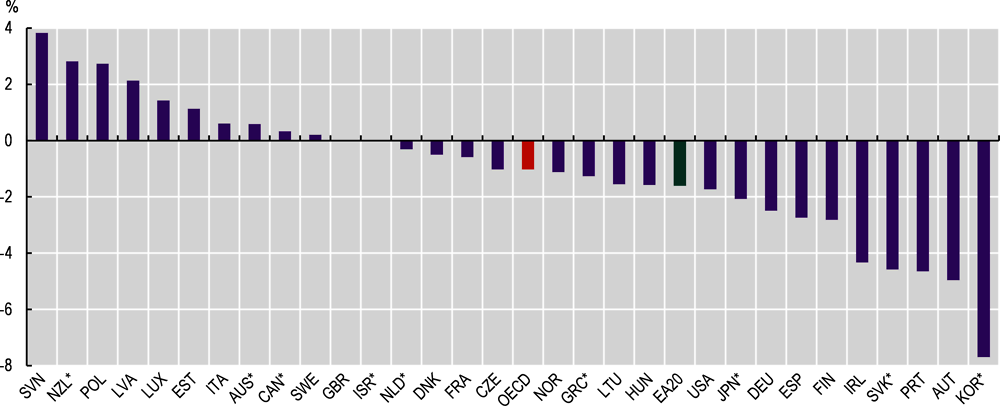

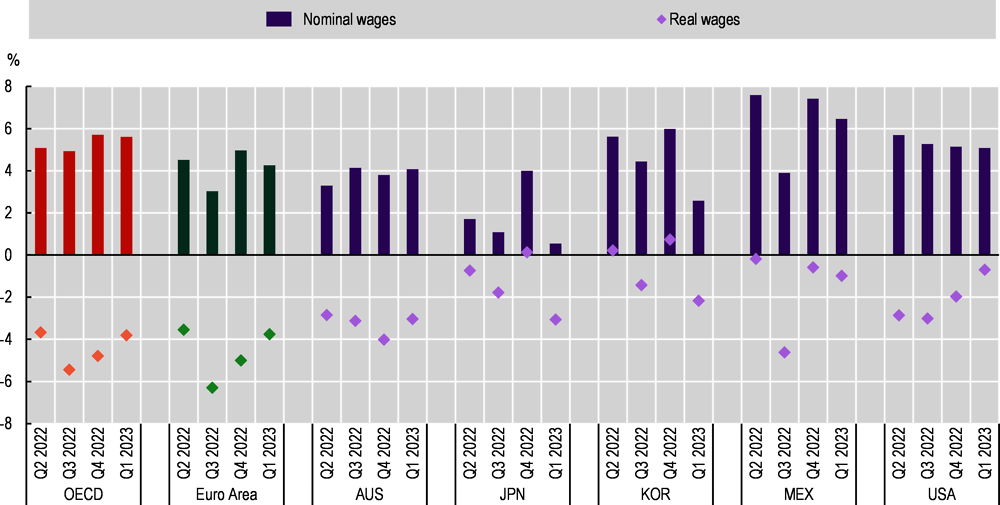

1.2.2. Despite a pickup in nominal wage growth, real wages are falling in all OECD countries

Year-on-year nominal growth in hourly wages generally picked up in 2022, but by less than the rise in inflation, leading to widespread falls in real wages. In Q1 2023, nominal year-on-year wage growth exceeded its pre-crisis level in nearly all OECD countries, reaching 5.6% on average across the 34 countries with data available (Figure 1.15, Panel A).17 However, nominal wage growth fell short of inflation by -3.8%, on average, with negative differences observed in 30 countries.18 19

Inflation has now exceeded nominal wage growth for several quarters in most countries. As a result, at the end of 2022, real wages were below their Q4 2019 level by an average of -2.2% in 24 of the 34 OECD countries with available data (Figure 1.15, Panel B).20 Even in the remaining 10 countries, however, inflation had eroded most of the nominal wage growth.

The evolution over the past year (leading up to Q1 2023) shows no clear sign of substantial acceleration of nominal wage growth across countries – with the dynamics of real wages still largely driven by inflation instead (Annex Figure 1.A.3). Data for April or May 2023 are only available for a limited number of OECD countries and, along with data from wages advertised in online job postings, point to a narrowing (or even closing in some countries) of the gap between nominal wage growth and inflation. This is mostly because of steady nominal wage growth and declining inflation (see Box 1.2).

Recent data on wages for five OECD countries mostly point to a narrowing of the gap between nominal wage growth and inflation (Figure 1.16). In fact, the latest data suggest that the fall in real wages might have come to an end in the United Kingdom, the United States and the Netherlands. This is mostly driven by a deceleration of inflation rather than an acceleration of nominal wage growth. In the United Kingdom, however, nominal wage growth was particularly robust in April 2023, reaching a high of just under 8%. In Canada and Japan, however, the latest year-on-year nominal wage growth remains below inflation, while in Korea it exhibits considerable short-term variation.

Nominal wage growth in online job postings is mostly steady in Europe and the United States, while inflation is slowly declining

Evidence from wages advertised in job posting on the online platform Indeed suggests a steady or declining nominal wage growth over the first five months of 2023 in Germany, France, Ireland, Italy and the United States (Figure 1.17). In Spain, the Netherlands, and – more markedly – the United Kingdom, nominal growth of posted wages has increased slightly. In general, the gap between inflation and nominal wage growth in posted wages (both measured here as 3-month moving averages) has becomes smaller. However, real growth in posted wages has turned positive only in Spain and the United States in recent months. In Italy, the gap between inflation and growth in posted wages increased again in May 2023, after declining for the first four months of the year.

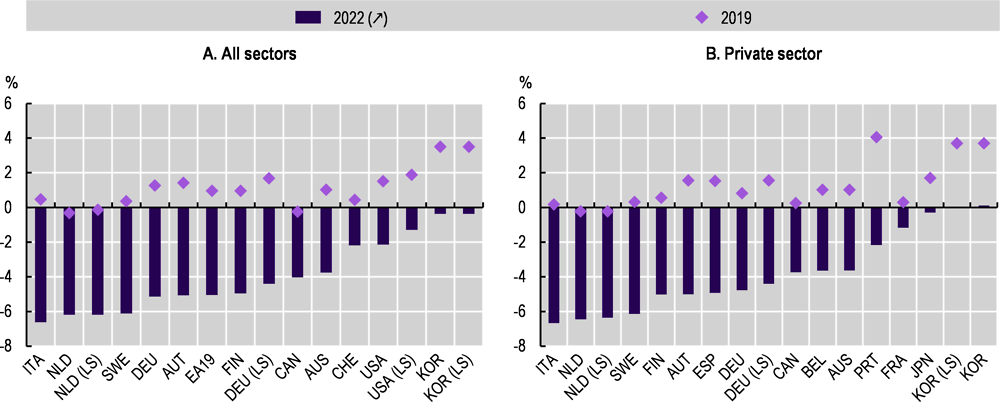

Real wages are falling across industries, but they are faring relatively better in low-pay industries in many countries

Wage dynamics could vary across the wage distribution due to factors such as labour demand, minimum wage laws, collective bargaining, and employer monopsony power. Since data on individual wages become available only with a significant lag for most countries, this section relies on wages by industry to provide some initial insights on how workers of different pay levels have fared in many OECD countries.

To offer an overview of wage developments by industry across countries, Figure 1.18 reports changes in real wages by industries aggregated in three broad groups: low-pay industries (accommodation and food services, administrative & support services, arts, entertainment and recreation, wholesale & retail trade); mid-pay industries (transportation and storage, manufacturing, other services, real estate activities, and construction); and high-pay industries (human health and social work, education, professional activities, information and communication, and finance and insurance). Industries are weighted by employment shares within each group.

Real wages have declined across industries in almost all OECD countries, but workers in low-pay industries have often fared relatively better (Figure 1.18, Panel A).21 The latest year-on-year changes for Q1 2023 show that real wages performed better in low-pay industries than in both mid- and high-pay industries in 15 of the 31 countries with data available. Conversely, wages in low-pay industries had the worst performance only in six countries, losing more than 1 percentage point relative to both mid- and high-pay industries only in Canada and Italy. In the pair-wise comparison, real wages performed better in low-pay industries than in mid-pay ones in 18 countries, and better than in high-pay industries in 22 countries.

The pattern of relatively better wage performance in low-pay industries also holds when considering changes relative to pre-crisis levels – even if over this longer time horizon real wages declined in fewer countries and industries (Figure 1.18, Panel B). Between Q4 2019 and Q4 2022, real wages performed better in low-pay industries than in both high- and mid-pay ones in 16 of the 31 OECD countries with available data. Conversely, wages in low-pay industries fared worse than both the other two groups of industries only in four countries (Belgium, Estonia, the Netherlands and Sweden). In the pair-wise comparison, real wages performed better in low pay industries than in mid-pay ones in 23 countries, and better than in high-pay industries in 20 countries.

Tight labour markets have contributed to stronger nominal wage growth

Tentative evidence suggests that labour markets tightening has been associated with stronger wage growth at the industry level. A simple analysis correlating changes in real wages with changes in vacancy rates for 14 industries in 15 OECD countries suggests that – on a year-on-year basis – a 1% increase in the vacancy rates was associated with a 0.03% increase in real wages. The analysis provides some indication that the correlation between tightness and real wage growth might have been slightly stronger in low-pay industries, but the differences are not statistically significant. In addition, a simple extension of the exercise does not support the conclusion that differences in either the level of tightness or in its impact across (broad) industries can explain the relatively better performance of real wages in low-pay industries. Similarly, another extension of the analysis finds that increases in statutory minimum wages are associated with larger increases in average wages particularly in low-pay industries, but this difference does not explain the differentials in wage growth across industries (see Section 1.3. for a detailed discussion of minimum wage policies and adjustments across OECD countries in recent times).22

These findings might be at least in part the result of averaging across countries with very different institutional settings. Using more granular data from before the pandemic, Duval et al. (2022[13]) find that in the United Kingdom and the United States, the impact of a given increase in tightness on wage growth is at least twice as large in low-pay sectors as in the average industry. However, they acknowledge that the gap might be smaller in continental Europe because of binding and stickier statutory or collectively bargained minimum wages. Consistent with this observation, Hentzgen et al. (2023[23]) find no correlation across industries between recent changes in tightness and nominal wage growth in France, a country where both collective bargaining and the minimum wage play a significant role in wage setting (see Section 1.3). As for the effect of the minimum wage, Hentzgen et al. (2023[23]) find a clear correlation between recent increases in wages in an industry and the proportion of workers affected by increases in minimum wages in France, but Autor et al. (2023[16]) find no indication in the United States that wages at the bottom of the distribution increased more in states that increased their minimum wages recently.

The developments of wages by industry suggest a compression of wages across pay levels, but more granular data are needed to assess the impact of the real wage crisis on inequality

The results presented in this section indicate a trend of compression of wages across workers of different pay levels, as proxied by industry wages. For the few countries for which data on wages by education and occupations are already available, the picture is mixed, with an indication of compression of wages across both education and occupation groups in Costa Rica, Mexico and the United States, but not in Canada and in the United Kingdom (see Box 1.3).

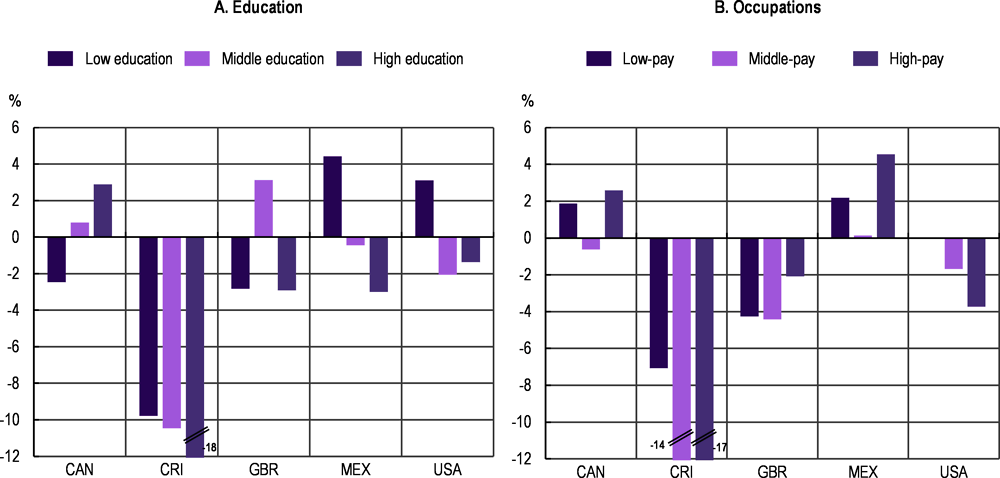

The main analysis in the chapter looks at wages by industry to provide evidence on wage dynamics across workers of different pay levels. For five countries, the analysis can be extended to look at changes in wages by education and occupation thanks to the timely availability of Labour Force Survey data. Figure 1.19 reports changes in real wages (calculated as the difference between nominal wage growth and inflation) for various groups between the end of 2019 and that of 2022. The results suggest a compression of wages across workers of different pay levels (as proxied by education and occupation) in Costa Rica, Mexico and the United States, but not in Canada and in the United Kingdom.

In Costa Rica and the United States, wages performed better among the low educated and workers in low-pay occupations (Figure 1.19). In Costa Rica, real wages fell across the board but much less among workers of low education and workers in low-pay jobs. In the United States, workers with low education and those in low-pay occupations were the only ones that avoided a real wage contraction between Q4 2019 and Q4 2022.

In Canada, Mexico and the United Kingdom, however, there is no clear sign of a compression of wages across groups of different pay levels, with results varying depending on whether education or occupations are considered. In Canada, workers with low education are the only ones to have experienced a fall in real wages since the start of the crisis (by -2.5%), but workers in low-pay occupations have seen better wage performance than those in middle-pay occupations (Figure 1.19). In Mexico, wage differentials by education have compressed, as the low-educated are the only group that experienced real wage growth. However, at the same time, wages have grown more for workers in high-pay occupations than in low-pay occupations. In the United Kingdom, the low-educated saw a decline in real wages of -3%, similar to that of high-educated workers, while real wages of mid-educated workers increased by 3%. Workers in low-pay occupations experienced a decline in real wages like those in mid-pay ones, while workers in high-pay occupations saw a smaller fall in real wages.

While informative of a widespread trend across OECD countries, these results do not allow strong conclusions on how the current wage crisis is affecting wage inequality more broadly. More granular data on wages are necessary to assess changes across the wage distribution and conduct a more reliable analysis of their determinants. Because of the paucity and the delay of this type of data, however, there is currently very limited evidence even on individual countries, with data pointing to a compression of the wage distribution in the United States but not in the United Kingdom.

For the United States, Autor et al. (2023[16]) document a remarkable compression of the wage distribution in 2021-22 which counteracted one-quarter of the four-decade increase in aggregate inequality between the 10th and 90th percentile. They find that the pandemic increased the elasticity of labour supply to firms in the low-wage labour market, reducing employer market power and spurring rapid wage growth at the bottom. Among the factors they discuss that might have contributed to this change is a decrease in work-firm attachment spurred by the large number of separations that occurred during the pandemic. By contrast, in the United Kingdom, gross hourly earnings of employees at the bottom and at the top of the distribution have grown in similar ways between the last quarter of 2019 and the last quarter of 2022, with slightly larger growth in the top decile than in the bottom one over the last year.23

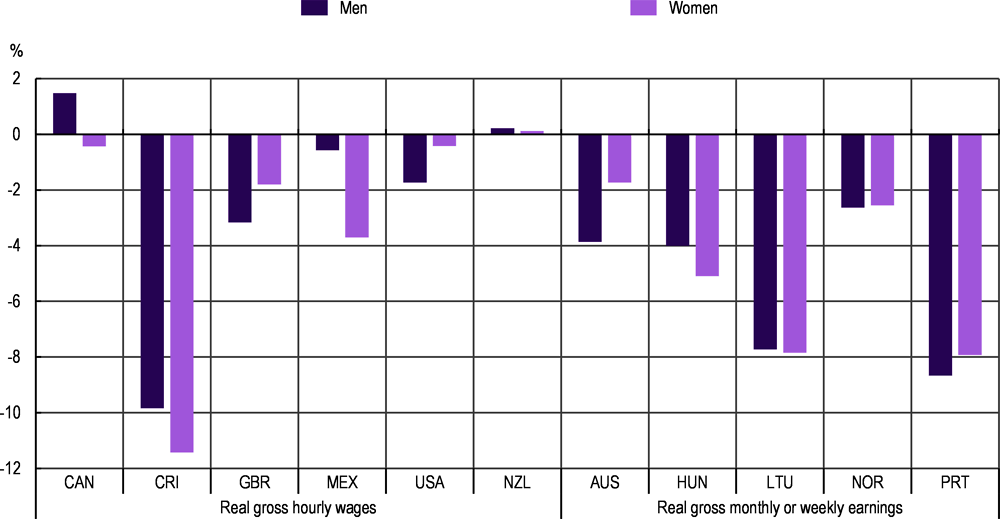

The cost-of-living crisis could affect men and women in different ways if wage dynamics differ substantially across industries and occupations with different gender composition. However, the limited data currently available show no systematic gender differences in the evolution in real wages across countries (Figure 1.20). In four of the 11 countries with data available for Q4 2022, men experienced larger year-on-year declines in real wages than women, with the largest differential in Australia and the United Kingdom where real wages for men fell by at least 3%. In four other countries, men fared better than women on average – with the largest difference in Mexico, where real wages for women fell by more than 3% against less than 1% for men. In the remaining three countries (Lithuania, Norway and New Zealand), year-on-year changes in real wages were similar between the two genders.

1.2.3. In many OECD countries, profits have grown faster than wages, making an unusually large contribution to price pressures and reducing the labour share

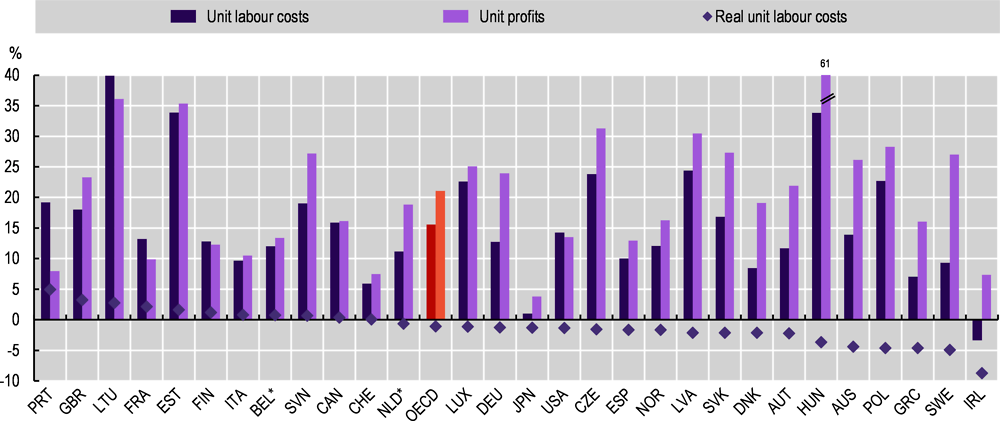

Over the last three years, labour costs per unit of real output (or unit labour costs) have increased in most OECD countries as growth in nominal wages has exceeded productivity growth (Figure 1.21).24 Profit margins, as measured by profits per unit of real output (or unit profits), also grew in most countries, indicating that – on aggregate – firms were able to increase prices beyond the increase in the cost of labour and other inputs.

In fact, in most countries, unit profits rose more than unit labour costs in 2021 and 2022. As a result, over the last two years, profits have made an unusually large contribution to domestic price pressures (Box 1.5) and the labour share (i.e. the part of national income allocated to wages and other labour-related compensation) has fallen in many OECD countries.25 Changes in real unit labour costs, i.e. the difference between changes in unit labour costs and changes in producers prices (i.e. GDP deflator) – offers a visualisation of the labour share changes. Real unit labour costs declined in 18 out of 29 countries with available data. Among the remaining countries, the largest increases in real unit labour costs took place in Portugal, the United Kingdom and Lithuania (Figure 1.21).26

The combination of rising unit labour costs and unit profits is relatively unusual as increases in one are often absorbed by a fall in the other (OECD, 2023[2]). Looking at historic evidence, one could have expected that the worsening of the terms of trade would have reduced profits (Arce and Koester, 2023[24]). The specific nature of the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis likely provided conditions particularly favourable to the expansion of profits margins.27 At the height of the COVID-19 crisis, in many countries, the fall in profit margins was mitigated by various forms of public support, including job retention schemes which subsidised labour hoarding to an unprecedented extent (European Central Bank, 2021[25]; OECD, 2021[26]). Unlike in previous recessions, production capacity was largely preserved during the pandemic-induced freezing of the economy. As economies re-opened, pent-up demand and large recovery plans bolstered aggregate demand and helped profits pick up quickly as supply-chain bottlenecks slowed down the expansion of supply. In a context with strong consumer demand and rapidly evolving inflation driven by external factors, firms might have had more room to increase prices simultaneously as they expected competitors to behave in the same way, while consumers might have been more prone to accept price increases given the inflationary context (Weber and Wasner, 2023[27]). In addition, some of the increases in prices might have also been in anticipation of future increases in input and labour costs (Glover, Mustre-del-Río and von Ende-Becker, 2023[28]). However, the recent decline in the cost of energy and other inputs along with downward price rigidity is likely to sustain profit margins at least in the near future (INSEE, 2023[29]; European Commission, 2023[30]).

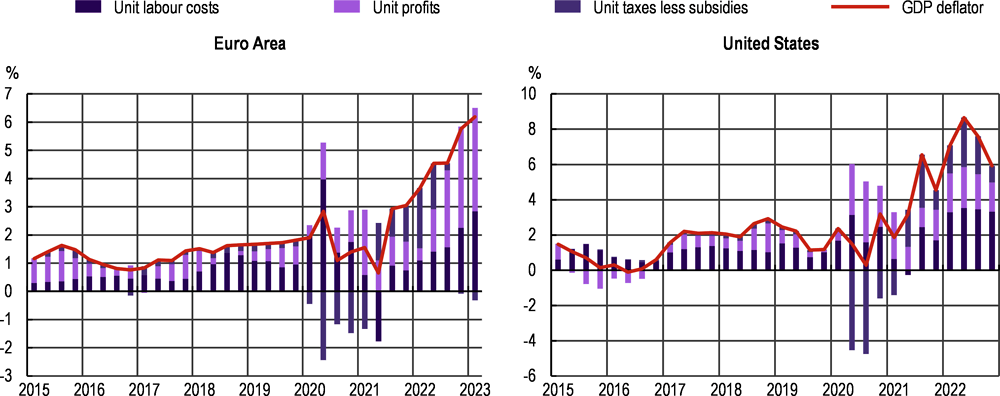

The initial surge in inflation was largely imported in many OECD countries and driven by commodity and energy prices. However, over the course of 2022, inflation became more broad-based with higher costs increasingly being passed through into the prices of domestic goods and services (OECD, 2022[1]). In addition to the increase in the costs of intermediate inputs, price dynamics are also influenced by changes in wages, profits, and taxes and subsidies. The analysis of this section shows that in recent quarters, both profits and labour costs have increased, with growth in profits exceeding growth in labour costs in many countries and sectors.

Figure 1.22 presents a decomposition of changes in the GDP deflator to gauge the contribution of wages, profits, and taxes to domestic price changes. Changes in the GDP deflator differ from consumer price inflation discussed in this section because the composition of household consumption underlying CPI-based measures of inflation is different from the composition of domestic output measured by GDP. Nevertheless, domestic price pressures are one of the main drivers of core inflation, i.e. inflation excluding energy and food (Arce and Koester, 2023[24]).

In the Euro Area and in the United States, both wages and profits have contributed to recent increases in domestic prices. In the Euro Area, the contribution of profits has been particularly large, accounting for most of the increase in domestic prices in the second half of 2022 and first quarter of 2023. This is in contrast with previous energy shocks, when increases in GDP deflator were mostly accounted for by changes in labour costs (Hansen, Toscani and Zhou, 2023[31]). In the United States, amid particularly tight labour markets, wages have generally contributed to increases in domestic prices more than profits in recent quarters. The recent contribution of profit margins was much larger than in the years before the crisis but has decreased in the most recent quarters. The differences between the Euro Area and the United States might in part reflect the fact that price dynamics have been more demand-driven in the latter (Hansen, Toscani and Zhou, 2023[31]). The contribution of unit taxes and subsidies has been particularly volatile over the period considered due to the introduction and withdrawal of pandemic-related subsidies as well as changes in the composition of household consumption (OECD, 2023[2]).

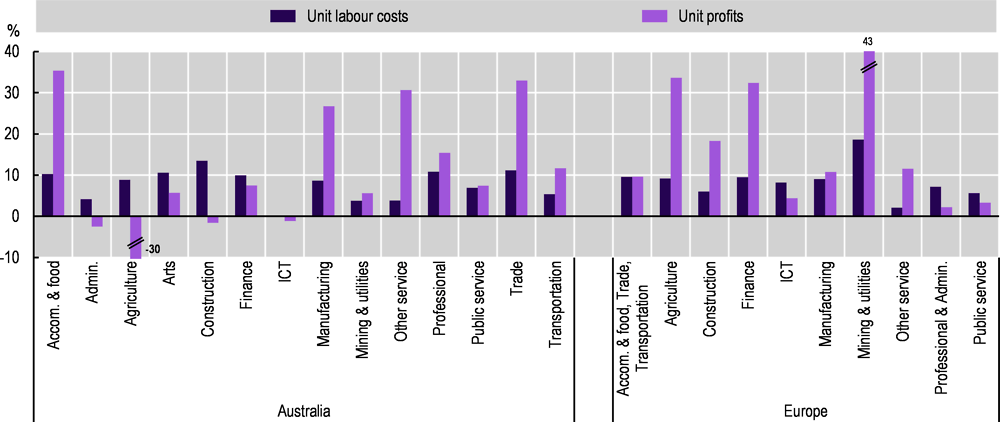

Data from Europe and Australia show that in the last year unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in several sectors beyond the energy one

Data from Europe and Australia show that the strong performance of profits in 2022 was not limited to the energy sector. In the year to Q1 2023, in Europe, unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in manufacturing, construction and finance, and grew at the same rate as unit labour cost in “accommodation food and transportation” (Figure 1.23). Similarly, unit profits increased more than unit labour costs in several sectors in Australia, including “accommodation and food”, manufacturing, trade, and transportation.

Going forward, this evidence suggests some room for profits to absorb further partial adjustments in wages without generating significant price pressures or resulting in a fall in labour demand. However, the implications of further increases in labour costs for prices, profits and labour demand can vary across firms depending on the competitiveness of the output market, the cost structure of the firm and the evolution of the business cycle. These factors can vary significantly even within the broad sectors referenced in Figure 1.23. Firms that have more market power or operate in non-tradable sectors are more likely to be able to increase prices.28 In contrast, firms operating in more competitive markets may have to absorb wage increases by reducing profits.

Rising costs of other inputs, such as energy, can also eat into profits and limit the ability to absorb some wage increases. Indeed, some of the increases in prices might have been in anticipation of further increases in input costs, as the energy shock works its way through the supply chain. Energy-intensive manufacturing may be particularly vulnerable to these cost pressures, but some service sectors – such as accommodation and food – are also relatively energy-intensive (European Commission, 2022[32]). The impact of the increase in input prices is likely to be more significant on small and medium firms in these sectors. However, given the downward rigidity of prices, the recent decline in input costs will also likely provide further room to absorb some wage increases without generating inflationary pressures. More broadly, firm profitability may be undermined in the short term by a fall in the demand due to the tightening of monetary policy and the erosion of purchasing power. In this context, rising labour costs might be more likely to translate into a reduction in labour demand and potential employment losses. All in all, while the evidence suggests room for profits to absorb some adjustments in wages in several sectors and countries, the exact room of manoeuvre will likely vary across sectors and type of firms.

With no indication of a price-wage spiral in recent data, there is room to adjust wages at least for the most vulnerable

The quick rise of inflation over the past two years – that largely originated outside the labour market – raised the concern that it might set-off a price-wage spiral which could further undermine the purchasing power of those employed and even lead to significant employment losses. The evidence presented in this section, however, offers no indication of signs of a price-wage spiral so far. Nominal growth has picked up but it exhibits no clear signs of significant further acceleration across countries. The gap with inflation appears to be narrowing in recent months mostly because of a slow decline in inflation, but the erosion of real wages has not halted yet in the vast majority of OECD countries.

On balance therefore, the main problem going forward is a deepening of the cost-of-living crisis across the OECD. A gradual recovery of at least some of the recent losses in purchasing power is essential to prevent widespread increases in economic hardship especially among workers with low earnings. The analysis of this chapter suggests that, in several sectors and countries, there is room for profits to absorb some further increases in wages to mitigate the loss of purchasing power at least for the low paid without generating significant additional price pressures. Given the downward rigidity of prices, the recent decline in input costs will also likely provide further room to absorb some wage increases without generating inflationary pressures. A fair sharing of the cost of inflation can prevent further increases in inequality and support effective monetary policy by averting feedback loops between profits, wages and prices. The next section discusses policy options to tackle the cost-of living crisis while avoiding a price-wage spiral, focusing on wage setting institutions.

Several policy levers can be mobilised to limit the impact of inflation on workers and ensure a fair share of the costs between governments, companies, and workers. The most direct way to help workers is via an increase in their wages. Governments can take measures to increase their national statutory minimum wage to ensure that they maintain purchasing power for low-paid workers. They can also promote regular renegotiations of collective agreements − given the critical role of wage settings institutions in ensuring adequate wage increases, while avoiding a price-wage spiral − via a suitable regulatory framework as well as tailored fiscal incentives.

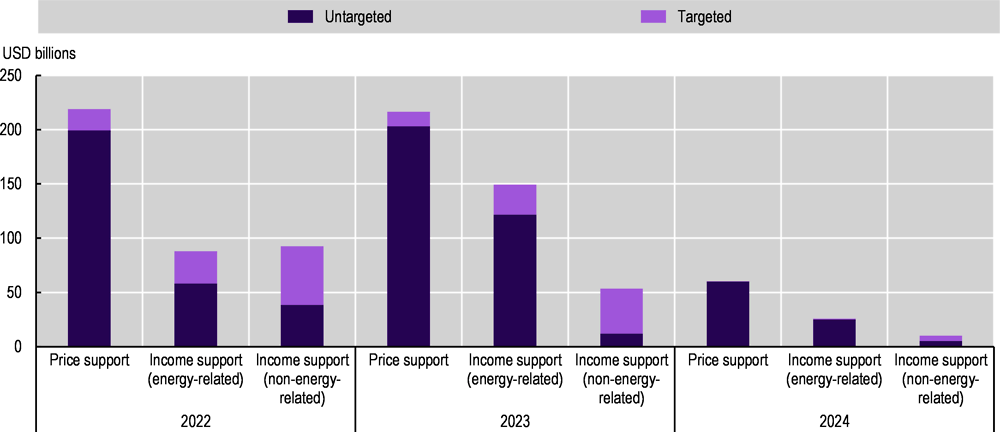

Beyond facilitating suitable adjustments of gross wages, governments can also provide direct support to net income more generally. Households and businesses can be compensated for the increase in prices via temporary price measures or via direct government transfers. Most OECD countries have for instance taken energy support measures between the end of 2021 and 2022, through price regulations, income support or tax reductions. Support to energy consumers was about 0.7% of GDP in the median OECD economy in 2022 but above 2% of GDP in some countries, especially in Europe. For the OECD area, similar levels of support are foreseen for 2023 (OECD, 2023[33]). However, only a fraction of the measures adopted in the last two years appears to be targeted to the most affected households and businesses (Figure 1.24). Ensuring that support measures are targeted and temporary is important to concentrate the support on those who need it most, preserve incentives for energy savings and avoid a persistent stimulus to demand at a time of high inflation (Hemmerlé et al., 2023[34]).

Finally, on top of ad hoc measures to mitigate energy costs, the existing tax and benefits systems can also be used to cushion the shock on the most vulnerable workers through in-work benefits and other social transfers.

On the tax side, some governments, for instance, have taken measures to limit the effects of the so-called “fiscal drag” (i.e. when increases in wages result in larger tax burdens) – see Box 1.6 – and reduce the tax wedge as to increase net wages without affecting labour costs for firms. Austria and Germany, for instance, introduced the possibility for firms to pay tax-free inflation-compensation bonuses (i.e. lump-sum payments) up to EUR 3 000. France detaxed profit-sharing bonuses in 2022 and 2023 for workers earning less than three times the minimum wage. Italy increased the threshold for tax-free “fringe benefits”29 to EUR 3 000, up from EUR 600, for all workers.

On the benefit side, several targeted cash benefits that provide a safety net in case of turbulence, including high inflation, were already in place prior to the cost-of-living crisis (OECD, 2022[35]). Unlike price regulation and subsidies, income support maintains price signals that are needed for easing supply bottlenecks and rebalancing consumption towards greener energy sources. However, except for some forms of in-kind transfers and “social tariffs” for housing or other forms of committed expenditures, such as utilities or public transport, most transfers are not immediately responsive to price shocks (e.g. social benefits do not increase when recipients face higher energy or food prices) as experienced by individual households. It is important therefore to ensure an effective and predictable support and that, despite rapidly changing price levels, transfers keep operating as they were intended to (OECD, 2022[35]).

Inflation not only erodes wages in real terms but can also increase the tax burden of workers via the so-called “fiscal drag” – i.e. the phenomenon whereby increases in wages result in larger tax burdens – meaning that workers could be doubly disadvantaged by inflation – see OECD (2022[35]) and OECD (2023[36]).

“Nominal” fiscal drag1 occurs when thresholds and tax brackets fail to fully adjust for inflation, resulting in workers being pushed into higher tax brackets. Inflation also reduces the real value of tax-free allowances, tax credits, and benefits. To the extent that these instruments target low-income workers, nominal fiscal drag can have a disproportionately large impact at the middle-to-lower end of the income distribution. Social security contributions are also affected by nominal fiscal drag, with impacts varying by income level. At the bottom end, fiscal drag will increase public revenues by lowering the real minimum earnings threshold for paying social security contributions. At the upper end, it will reduce revenues by reducing the value of contribution ceilings.

To mitigate “nominal” fiscal drag, countries can adjust personal income tax (PIT) systems, social security contributions (SSCs), and cash benefits in response to inflation. Some countries automatically adjust these parameters, while others use discretionary approaches. In 2022, in just under half of OECD countries, the PIT system is adjusted automatically, while for 21 countries the adjustments are discretionary (see Table 1.1). The majority of countries index SSCs and cash benefits2. Twelve countries adjust each of PIT, SSCs and benefits automatically, while ten adopt a discretionary approach to all three categories. The timing and modality of adjustment vary across countries: some use prices (CPI or other indices) while others use wages. Long delays in adjusting parameters and incomplete adjustments can contribute to discretionary measures, including pressures for untargeted solutions, and be particularly challenging for the most disadvantaged individuals (OECD, 2022[35]).

← 1. As opposed to “real” fiscal drag which occurs when wages grow in real terms, resulting in a worker’s tax burden increasing with the progressivity of the tax system.

← 2. The cash benefits analysed in this box are limited to those transfers that are contained in the OECD Taxing Wages models; the analysis may not cover all social protection benefits that a given country might provide.

The remainder of this section focuses on the role that minimum wages and collective bargaining have played so far in cushioning the costs of inflation partially drawing on a policy questionnaire that was addressed to OECD countries as well as trade unions and employers’ organisations through the Business@OECD (BIAC) and Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC) networks – see Box 1.7.

The analysis on minimum wages and collective bargaining in this chapter partially draws on the information provided by the responses to an OECD policy questionnaire that was circulated in January and February 2023 to Labour Ministries as well as to employer organisations and trade unions through the Business@OECD and TUAC networks across OECD countries. The information collected via the policy questionnaires has been complemented and cross-checked with other data sources at national and international level.

The questionnaire focused on i) the minimum wage uprating procedures (e.g. the frequency of updating, the use of indexation, etc.); ii) the special measures taken to speed up the increase of minimum wages since January 2022; iii) the renegotiation of collective agreements (e.g. frequency, indexation, ultra-activity, etc.); iv) the measures taken by governments to promote the renegotiation of collective agreements and protect wages from the increase in prices.

36 out of the 38 OECD countries have filled in the questionnaire as well as 18 employers’ organisations and 18 trade unions. If the rules change across geographical areas (states, provinces, prefectures, cantons, etc.), the information was reported using the largest area as a reference. Moreover, in the case of collective bargaining, if there are differences across sectors, the answers focused on what is applicable in the agreement that prevails for the manufacturing sector.

1.3.1. Minimum wages have kept pace with inflation

Currently, 30 out of 38 OECD countries have a national statutory minimum wage in place30 and minimum wages also exist in most non-OECD emerging economies. Statutory wage floors are the most direct policy lever governments have for influencing wage levels at the bottom of the distribution. Historically, minimum wages have been justified as a measure for: i) ensuring fair pay, ii) counterbalancing the negative effects of firms’ labour market power; iii) making work pay; iv) boosting tax revenue and/or tax compliance by limiting the scope of wage under-reporting.31

With the sharp rise in prices in most OECD countries hitting particularly the most vulnerable, low-income households, minimum wages have become an even more important tool to protect the standard of living of low-paid workers.32

Almost all OECD countries have taken measures to increase their minimum wages between January 2021 and May 2023, including special measures to speed up minimum wage adjustments in the current cost-of living crisis (see below). If minimum wages are keeping pace so far with inflation in many OECD countries, real wage gains may actually quickly vanish over time as inflation remains high as it happened in 2022 – see Figure 1.25 and trends for all OECD countries with a statutory minimum wage in Annex 1.C.

Some of the differences across OECD countries in the timing, frequency, and size of the nominal increases are linked to different uprating procedures (see Table 1.2). In most OECD countries, the minimum wage is adjusted annually with a usually short delay between the decision and the application. In other countries, the minimum wage is adjusted annually or biannually but with a slightly longer delay which may make a difference in times of high and/or rising inflation. Finally, in some countries, there is no regular adjustment, which may result in long delays and major losses in purchase power. In the United States, for instance, the federal minimum wage has not been increased since 2009 (while minimum wages at state and local level have been updated much more regularly).

The revision of minimum wages may be subject to government discretion or can take place automatically in case of indexation. In some OECD countries – notably, Belgium, Canada (since April 2022), Costa Rica, France, Israel, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Poland – there is a form of automatic indexation mechanism for the minimum wage at national level (Table 1.3). But automatic indexation also exists for minimum wages at subnational level (e.g. in Canada, Switzerland and the United States). Indexation may then be anchored to wages or prices. Minimum wages are for instance indexed to negotiated wages (i.e. wages defined in collective agreements) in the Netherlands, and to average wages in Israel. Indexation to (past) prices is in places, instead, in Belgium, Canada, France33 and Luxembourg34 as well as nine provinces and territories in Canada, four cantons in Switzerland and 19 states and the District of Columbia in the United States.35 Furthermore, multiple increases can also take place in years of high inflation, as in Belgium, France and Luxembourg.36 Poland links its minimum wage to future price developments and corrects it ex post in case of differences between the forecasts and the realised rates. Finally, a few countries have a form of indexation that kicks in only if social partners fail to find an agreement (Colombia and the Slovak Republic).

In other countries, discretionary measures have been taken over the last months to speed up the increase of minimum wages. In Chile, for instance, the minimum wage was increased three times in 2022 reflecting the increases in inflation. In Greece, after postponing the increase during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government increased the minimum wage in January 2022 and then again in May 2022. In Türkiye, the minimum wage was increased by around 40% in January 2022 and nearly 30% in June 2022. In October 2022, Germany increased its minimum wage by 15%, from EUR 10.45 to EUR 12 per hour.37 Similarly, in the Netherlands, in October 2022, the government decided, for the first time since the introduction of the minimum wage in 1969, to go beyond the formula displayed above and exceptionally increase the minimum wage by 10% in January 2023. Ireland also announced in 2022 its intention to raise the minimum wage to 60% of the median by 2026, which would correspond to an increase of 16% compared to the current level. In Hungary, the social partners agreed to further increase the minimum wage mid-year if inflation rises to 18% and GDP growth is positive (Eurofound, 2023[37]).

These minimum wage increases, especially when linked to a formula that automatically indexed them to past inflation, are raising two main concerns: a squeezing of the wage distribution and the risk of a price-wage spiral, especially in case of high inflation and uncertainty. In fact, increases in minimum wages often have spillover effects higher in the wage distribution and can, therefore, have an aggregate effect on wage growth that goes well beyond the direct beneficiaries. This happens because minimum wages are used, formally or informally, as a benchmark in the negotiation of collective and individual wages as well as a reference for certain social minima.

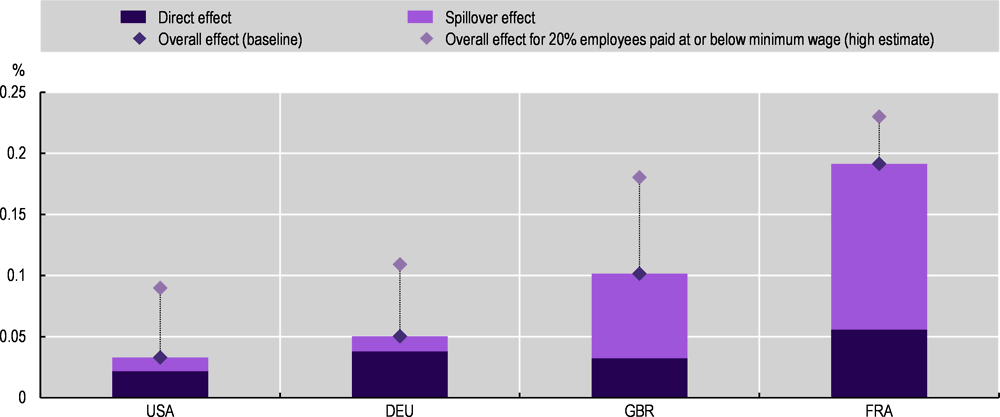

Figure 1.26 estimates the impact of minimum wage increase to the growth in aggregate wages, accounting for both its direct effect (on those at or below the minimum wage) and its spillover effect (on those above the minimum wage). The impact of a 1% increase in the minimum wage is simulated using estimates of spillover effects from the literature and taking the share of the minimum wage earners in a baseline year (2018 for France and Germany, an average of 2019, 2021 and 2022 for the United Kingdom and 2022 for the United States) – see Box 1.8 for more details. This exercise suggests that a minimum wage increase of 1% can be expected to have an effect on aggregate wage growth between 0.03% (in the United States, using the share of minimum wage earners of state-level minimum wages) and 0.2% (in France). These estimates are in line with those of Koester and Wittekopf (2022[38]) who conducted a similar analysis with another data source and only including the direct effects.

These cross-country variations can be explained by the difference in the share of minimum wage earners, the magnitude of the spillover effects and the shape of the wage distribution. In France, where a relatively high proportion of workers earns the minimum wage (the share of minimum wage earners even increased since 2018 to 14% in 2022), a double automatic indexation of the minimum wage is in place and the wage distribution is relatively compressed, most of the aggregate wage effects come from wage increases higher up in the wage distribution (i.e. spillovers). On the opposite, in a country like the United States where the share of minimum wage earners is low (around 6% in 2022), spillovers are quite limited and the wage distribution is less compressed, most of the aggregate wage effects come from the increase in minimum wage earners (i.e. direct effects). Between these two polar cases, there are Germany where the share of minimum wage earners is relatively high (8.4% at the baseline in 2018) but the wage distribution is less compressed and the United Kingdom where the share of minimum wage earners (5.9% at the baseline) is similar to the United States but the wage distribution is more compressed.

These effects could be, nonetheless, somewhat underestimated. First, spillover effects could be stronger in a high inflation environment when minimum wage increases are larger and more frequent. Second, these estimates do not account for possible feedback loop on the minimum wage, notably in a country like France where the minimum wage is also indexed to half of the past increase of the real wage of blue-collar workers.38 However, the overall impact is likely to remain relatively limited in magnitude: even assuming a higher share of minimum wage earners (20%), Figure 1.26 shows that the aggregate wage effects range between 0.09% (in the United States) and 0.23% (in France) suggesting a rather limited risk of major impact on wage inflation of minimum wage increases.

On top of the effect of a minimum wage increase on aggregate wages, a second issue is how firms which employ minimum wage workers respond to increases in the minimum wage, and, in particular, if and how much these firms are able to pass higher wages onto prices. Most empirical studies agree that part of minimum wage increases is passed on to consumers – see e.g. Harasztosi and Lindner (2019[39]). However, Lindner (2022[40]) calculates that in the United Kingdom, an increase in the minimum wage of 20% would still only lead to an increase in inflation of 0.2% − which compared to the inflation rates observed in the last quarters is small.

In order to estimate the impact of an increase in the minimum wage on the total wage bill (henceforth, the “aggregate effect of minimum wage increases”), both the direct effect of a minimum wage increase, i.e. the wage increase for minimum wage earners, and the spillover effects, i.e. the wage increase for those employees earning more than the minimum wage as firms may have to readapt pay scales to maintain wage differentials, is calculated.

The direct effect is estimated by a 1% increase in hourly wages at, below or slightly above the minimum wage (threshold set at 105% of the minimum wage). For the employees at or below the threshold, the average hourly wage and the average number of hours worked are calculated using EU-SES (2018) for France and Germany, the UK-LFS (2019 and 2021-22) for the United Kingdom and the CPS (2022) for the United States. Using the information on hourly wages and hours, the total wage bill of the employees affected by an increase in the minimum wage is computed.

For the spillover effects, the same calculation is made for four wage bands expressed as a fraction of the minimum wage MW (1.05<MW≤1.2; 1.2<MW≤1.5; 1.5<MW≤2; MW>2) using spillover estimates from the literature (pre-dating the surge in inflation):

In France, building on the work by Gautier, Roux and Suarez Castillo (2022[41]) and Aeberhardt, Givord and Marbot (2012[42]), an increase in the minimum wage of 1% is assumed to lead to an increase of 0.2% in wages up to 1.2 times the minimum wage level; 0.1% between 1.2 and 1.5 times the minimum wage; 0.1% between 1.5 and 2 times the minimum wage, and 0 above.

In Germany, building on the work by Biewen, Fitzenberger and Rümmele (2022[43]), an increase in the minimum wage of 1% is assumed to lead to an increase of 0.02% in wages up to 1.2 times the minimum wage level, and 0 above.

In the United Kingdom, building on the work by Giupponi et al. (2022[44]), an increase in the minimum wage of 1% is assumed to lead to an increase of 0.02% in wages up to 1.2 times the minimum wage level, and 0 above.

In the United States, building on the work by Gopalan et al. (2021[45]), an increase in the minimum wage of 1% is assumed to lead to an increase of 0.03% in wages up to 1.2 times the minimum wage level; 0.03% between 1.2 and 1.5 the minimum wage, and 0 above.

Beyond the risk of a price-wage spiral, which is likely to be limited as just illustrated before, there are other aspects to consider in assessing the merits and pitfalls of regular and sustained minimum wage increases in times of high inflation, especially when linked to an automatic indexation to past price developments. On the one hand, these increases contribute to safeguard the purchasing power of minimum wage earners and may help to reduce in-work inequality (or at least limit its increase, in cases where high-wage workers are able to negotiate wage increases that keep pace with inflation while low-wage workers are not). Automatic indexation, more specifically, may also increase visibility and transparency for firms, which can more easily anticipate future increases,39 as opposed to discretionary increases. On the other hand, automatic indexation mechanisms may reduce the margins of judgement that governments, social partners or commissions have in deciding future increases (e.g. in a period of stagflation, decision-makers may have to weigh the risk of loss of purchasing power against the risk of job losses), limit the role of social partners in setting wages, and may also lead to an excessive compression of the wage distribution if the rest of the wage structure does not move, with consequences on individual careers, as well as on the design of redistribution policies.

While keeping these potential pitfalls in mind, in a context of high inflation, it remains important to ensure regular adjustments of statutory minimum wages to maintain their usefulness as a policy instrument and protect, at least partially, the most vulnerable workers from rising prices.

1.3.2. Negotiated wages: falling in real terms even in countries with high collective bargaining coverage

Collective bargaining: A tool to ensure fair and tailored responses to inflation cost

Statutory minimum wages only determine the wage floor. Above that floor, collective bargaining can play an important role in ensuring a fair share of the cost of inflation for a large share of the employees, in particular at the bottom and the middle of the wage distribution. Collective agreements can help companies and workers find tailored and ad hoc solutions to avoid a price-wage spiral, for instance by limiting (permanent) wage increases in exchange for lump-sums and/or non-wage benefits. Blanchard and Pisani-Ferry (2022[46]), for instance, argue that a forum in which trade unions, employers’ organisations and the government agree on how to share the burden of inflation would likely allow a fairer outcome and lower risk of second-round inflation (e.g. a pass-through of inflationary shocks on wages and prices, thereby triggering a price-wage spiral), making the job of monetary policy easier. Tripartite agreements, including on wages, were relatively common in the heydays of collective bargaining, but they are now very rare. However, the 2022 tripartite agreement on wages and competitiveness in Portugal shows how tripartite social dialogue can be revived to help ensuring a fair share of the costs of high inflation (see Box 1.9).

In October 2022, the government, four employer associations and the trade union UGT in Portugal signed a tripartite agreement on wages and competitiveness. The General Confederation of Portuguese Workers (CGTP-IN) did not sign the agreement, taking the view that wages should be subject of collective agreements alone.

The key goals of the pact are to increase the labour share (i.e. the part of national income allocated to wages and other labour-related compensation) by 3 percentage points compared to the pre-crisis value, to converge with the European average and to raise productivity growth to 2% by 2026.

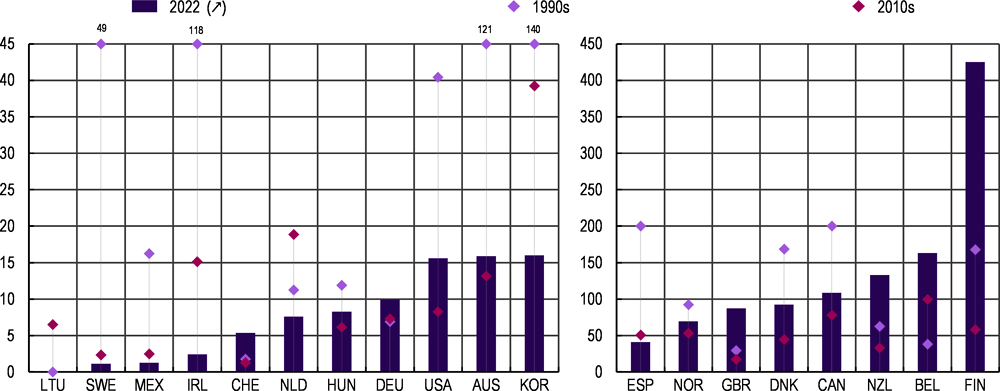

To achieve these objectives the minimum wage will increase from EUR 760 in 2023 to EUR 900 in 2026. In parallel, several measures will be taken to boost workers’ income via the tax and benefit system. In particular, the personal income tax (IRS) brackets will be revised to avoid that pay rises to compensate for inflation lead to higher taxes – a phenomenon known as fiscal drag. In addition, the incentives to return to the labour market will be strengthened by allowing the partial accumulation of unemployment benefits with the wage. Moreover, overtime pay will be increased, and the severance pay in case of dismissal for economic reason (individual or collective) will increase to 14 days per year of tenure from 12 now.