7. Uzbekistan

This chapter assesses recent achievements trade facilitation reforms in Uzbekistan, while also considering the remaining challenges. It highlights the progress made in establishing the Single Window, reducing tariffs, streamlining trade-related documentation, implementing automation procedures, and creating stakeholder engagement and feedback mechanisms. Subsequently, the outstanding issues in procedural streamlining, process automation, and agency co-operation are assessed. Finally, the chapter addresses the importance of drawing inspiration from, and collaborating with, neighbouring peers to further progress in trade facilitation performance.

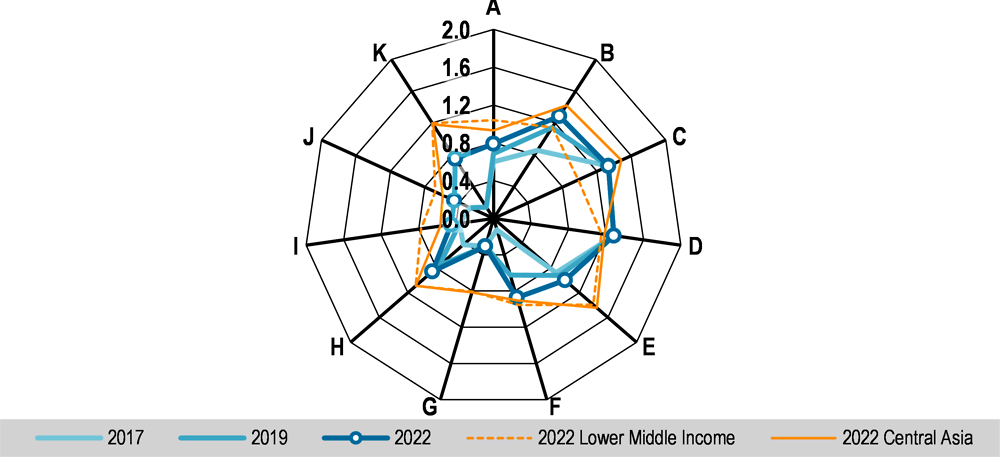

Uzbekistan has made the greatest relative improvement since 2019, but as it has progressed from a low base it still lags its regional peers in average Trade Facilitation (TFI) performance. During this period, it has made strides in simplifying and streamlining trade-related documentation and improving its governance and impartiality as well as trade community inclusion. Though Uzbekistan’s progress is commendable, and it performs relatively well on appeal procedures, private sector consultations, and streamlining of procedures and processes, it trails other countries in Central Asia on most other indicators.

Since 2017, Uzbekistan has improved trade conditions for firms by easing financial pressure. For instance, it unified the exchange rate in 2017, devalued the som, and further liberalised the currency controls in 2019 by introducing a floating exchange rate (OECD, 2023[1]). This accompanied an easing of the foreign exchange restrictions with the abolition of the requirement for firms to surrender foreign exchange earnings. At the same time, import tariffs were reduced for some 8,000 of the 10,800 subjected goods and discriminatory excise taxes have nearly been totally removed. As outlined in the Development Strategy of New Uzbekistan for 2022-2026, the government aims to make further progress in this area to reduce the cost of trade and develop a more comprehensive regulatory framework, in part due to its renewed interest in joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) (OECD, 2023[1]).

The government has also enhanced its stakeholder engagement and feedback mechanisms. It has developed guidelines and procedures on public consultation processes, created a framework for notice-and-comment procedures, and increased the number of stakeholders involved in consultation processes. The country has also made progress in its advance rulings system and procedural rules for appeals. It has taken important steps in establishing an Authorised Operators (AO) programme, simplifying post-clearance audits as well as the treatment of perishable goods (separating release from clearance), pre-shipment inspections, the use of customs brokers, and temporary admission of goods. The electronic payment of duties has improved and the government has introduced automated risk management along with accepting copies rather than originals of documents. Uzbekistan has established a Single Window (see Box 7.1) to lower the barriers to trade and it is increasingly aligning with international standards, further simplifying trade-related documentation requirements.

In 2015, Uzbekistan started to digitalise public authority services. In 2018, the State Customs Committee of Uzbekistan developed the Unified Customs Single Window Information System, a centralised platform for the processing of certificates and permits by competent authorities hosted on http://singlewindow.uz/. The system has gradually incorporated several institutions with responsibilities in cross-border trade, allowing Uzbekistan to increase the comprehensiveness of the system. By now, the Single Window provides a unified list of templates of required administrative documents and guides on how to complete them, information about the potential risks as well as a tool the verify online the authenticity of certificates. There are links towards external but related websites, such as those of the different controlling authorities, customs registries, and logistics companies, as well as a dedicated portal for trade – Uzbekistan Trade Info – available in Uzbek, Russian and English at https://uztradeinfo.uz/.

The State Customs Committee has also developed mechanisms to secure integrating systems of other agencies feeding information into the Single Window. To increase the extent of trade transactions covered, there are plans to include additional institutions such as the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Culture and Sports, or the State Tax Committee. This will also require further work to map the different regulatory and documentary requirements that need to be incorporated into the system. Developments have also been taken towards enhancing the system’s electronic data exchange capability and in harmonising data requirements in the Single Window with internationally accepted data standards, such as those provided by the World Customs Organization (WCO).

Source: OECD TFIs background data repository. (State Customs Commmittee of the Republic of Uzbekistan, 2019[2]; Ministry of Investment, Industry and Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan, 2023[3])

Automation of border-related processes, and streamlining and harmonisation of procedures, are among the most significant shortcomings in Uzbekistan’s trade facilitation environment. Though establishing a trade facilitation portal through the Ready4Trade programme is an important endeavour in this area, more can be done to make trade information available increasingly comprehensive and available online. Additional efforts are required to make the data requirements and Single Window design and work plans compatible with the different border management and user platforms in the country. Further efforts are also needed to make private sector feedback mechanisms more operational. For instance, Uzbekistan launched a modernisation project of its border infrastructure and processes in Yallama. It streamlined procedures, such as distinguishing between passenger and cargo vehicles, automating and digitalising processes through a one-stop shop, and a Single Window system enabling the submission of all regulatory documents. In the first quarter of 2020, it introduced automated inspections that reduced the average border crossing time for goods from 11.4 to 4.4 hours by the end of 2021 (Development Asia, 2022[4]). The improvements achieved in recent years in the streamlining of processes require equal improvements in the areas of trade-related documentary requirements and automation. In addition, the advances in the implementation of regulatory frameworks for streamlining border processes need to be complemented by subsequent progress in operational practice, though it has made progress.

Co-operation, co-ordination, exchange of information and mutual assistance now involve domestic agencies taking part in the management of cross-border trade, but Uzbekistan’s agency collaboration remains largely ad hoc rather than systematised. There are regular meetings between involved public agencies, while informal and ad hoc coordination is taking place between agencies to address contingencies at the border. Domestic agencies involved in the management of cross-border trade share infrastructure and equipment more frequently. In addition, national legislation now allows for cross-border co-operation, co-ordination, exchange of information and mutual assistance with border authorities in neighbouring economies, providing a foundation for further progress, including road permit standardisation. Uzbekistan connected its national customs systems to the e-TIR road permit system together with Azerbaijan and Georgia in 2022, and the following year it trialled the first BSEC e-Permit project together with Türkiye that combines the e-CMR and BSEC e-Permit systems (BSEC-URTA, 2023[5]; UNECE, 2023[6]).

Uzbekistan should look to publish more comprehensive and up-to-date information online and establish a dedicated interactive page for professional users. This would not only improve transparency but would also help to build a more predictable trade environment. It could include appeal procedures, examples of customs classification, penalty provisions, and judicial decisions on trade-related issues, as well as all fees and charges on its Single Window and relevant websites. It can consider better integration of non-customs agencies as well as improving site functionalities, such as fixing broken links, in its Single Window. Like other countries in Central Asia, Uzbekistan should ensure that fees and charges are assessed periodically and adapted to changed circumstances and include sufficient time between the adoption of new or amended fees and charges and their entry into force. Similarly, notice-and-comment procedures should include trade and border issues and regulations as well as drafts of new or updated trade-related regulations before entry into force, also enabling stakeholder comments. Finally, Uzbekistan could pay more attention to adapting the enquiry points to commercial needs and improve their timeliness.

Uzbekistan remains behind its regional peers on harmonisation, digitalisation, and automation of import/export procedures, so it can draw on best practices from them to facilitate trade processes. In particular, it could look at how Kyrgyzstan continues to develop its Single Window (see Chapter 4 on Kyrgyzstan). In the short term, streamlining can be achieved by expanding the number of documents for which copies instead of originals are accepted, while documentation requirements should be frequently reviewed and updated. Finalising the introduction of an automated risk management system for all relevant border agencies, developing the pre-arrival processing for all import transactions, separating the release from clearance for all goods, developing post-clearance audits and improving the physical inspections and storage conditions of perishable goods would streamline operations and increase Uzbekistan’s competitiveness. As these actions require close co-ordination and co-operation among agencies, the government could consider how Croatia created inter-departmental and -ministerial groups to improve cross-cutting border management processes (Box 7.2).

Public entities could increase the share of import and export procedures and declarations that can be processed electronically. Moreover, Uzbekistan can expand the duties, taxes, fees, and charges that can be digitally collected upon in advance. Domestic agencies involved in the management of cross-border trade should improve their interconnected or shared computer systems and real-time availability of pertinent data among themselves.

Croatia set up its strategy for improving domestic border agency co-operation in 2005, which was implemented by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Customs Administration of the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Development, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the State Inspectorate. The strategy gradually incorporated additional agencies, including the state authorities in charge of sea traffic and infrastructure, foreign affairs and European integration, defence, justice, economy, labour and entrepreneurship, environment, physical planning and construction, culture, and mining. It set up two teams:

Inter-departmental Working Group (IWG) was set up to ensure and improve the co-ordination and co-operation between agencies involved in border management to avoid duplication of procedures, reduce the time necessary to complete border processes, better align the work of all departments at the border, and increase synergies between all central government bodies. The tasks of the IWG were to analyse the border procedures of individual agencies, implement processes for faster border crossing and more effective border protection; enhance inland waterways co-operation with central and local government bodies and other agencies; address disagreements between the agencies; supervise the implementation of Croatia’s Agreement on Co-operation in Integrated Border Management; and co-ordinate the construction, maintenance and equipping of border crossings and other infrastructure required. The IWG meets regularly on all matters relevant to border management decisions and can also meet on extraordinary matters, keeping records of all its meetings.

Inter-ministerial professional work (IMPW) teams to address legal issues, organisation and management, and infrastructure, equipment and information technology. Depending on the topic, IMPW teams integrate other entities such as plant health, animal health, or environmental protection. They address specific areas of border agency co-operation, such as monitoring and adjusting the national legal and regulatory framework with legal standards and best practices of the European Union; developing an overview of border and other procedures to suggest improvements, developing common standard operating procedures, analyse data received from all the agencies involved, develop joint risk analysis, organise and implement joint actions proposed, develop joint manuals, organise joint training and exercises, and develop joint plans for the use of infrastructure facilities, technical equipment and information technology; revising as needed the strategy and action plan of domestic border agency co-operation; preparing reports on their implementation which, after approval by the IWG are sent to the Croatian Government for adoption; monitoring and analysing the operational implementation of Croatia’s Agreement on Co-operation in Integrated Border Management.

Source: OECD TFIs background data repository based on (WCO, 2016[7]).

References

[5] BSEC-URTA (2023), Project: Digitalization Direction: Lots of common work and cooperation, https://bsec-urta.org/2023/04/08/project-digitalization-direction-lots-of-common-work-and-cooperation/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

[4] Development Asia (2022), “Facilitating Cross-Border Trade in Yallama”, Development Asia, https://development.asia/insight/facilitating-cross-border-trade-yallama.

[3] Ministry of Investment, Industry and Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2023), Uzbekistan Trade Info, https://uztradeinfo.uz/?l=en (accessed on 21 September 2023).

[1] OECD (2023), Insights on the Business Climate in Uzbekistan, OECD Publisher, https://doi.org/10.1787/317ce52e-en.

[2] State Customs Commmittee of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2019), Single Window of the Republic of Uzbekistan, http://singlewindow.uz/ (accessed on 20 September 2023).

[6] UNECE (2023), First eTIR transport takes place between Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan paving the way to a digital era in international transport and transit, https://unece.org/media/transport/TIR/press/374919.

[7] WCO (2016), Strategy for Integrated Border Management (Croatia), https://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/webtool/es/art-8/practices-_-croatia.docx?la=es-ES.