4. Using school funding to achieve both efficiency and equity in education

Most countries explicitly aim to improve access, quality, equity and efficiency in their education systems. However, fulfilling these objectives at the same time is a challenge for policy makers. The pursuit of equity and efficiency in particular has often been presented as a trade-off when it comes to the allocation of resources in education. Nevertheless, efficiency and equity can go hand in hand and this chapter examines how the two can be brought together. It presents insights and promising policies from OECD countries in four areas that can help improve both equity and efficiency: Investing in high-quality ECEC; investing in teacher quality; reducing educational failure; and adapting school networks to changing demand.

Most countries worldwide have formulated explicit goals for broadening access and enhancing the quality, equity and efficiency of their education systems. Yet school systems have limited resources with which to pursue these objectives and are thus confronted with difficult spending choices and resource trade-offs.

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a vivid illustration of these dilemmas and further complicated resource allocation choices given the emergence of a new priority: containing the spread of the virus within schools as a way 1) to ensure the safety of students, teachers and other school staff, and 2) to maintain education continuity and face-to-face social interactions following the 2020 school closures. In addition, the episodes of school closures have increased socio-economic disparities and thus renewed the priority of addressing inequities in the education system. Finding the best possible allocation of limited resources among competing priorities has, therefore, only gained in importance. These concerns gained even more prominence in the aftermath of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the surge in new budgetary priorities that resulted from this new crisis, e.g. in boosting investments into national defence and military equipment for many countries.

Regardless of which areas of school spending – such as infrastructure, staff or ancillary services – are concerned, school systems need to make sure that resources are used efficiently and directed where they have the greatest impact on students, informed by an analysis of national and local contexts. Educational efficiency is typically conceptualised as the property of fulfilling maximum educational potential at the lowest possible cost. In this context, efficiency improvements in school education can be achieved in two ways: either by maintaining identical levels of outcomes while lowering the amount of school funding, or by attaining better outcomes with the same level of funding (OECD, 2017[1]).

The pursuit of equity and efficiency in education has often been presented as a trade-off when it comes to the allocation of resources, but these two objectives can go hand in hand.

Efficiency and equity are sometimes seen as competing goals in education since equity measures often entail additional investment for disadvantaged student groups, which may not translate into proportional increases in student achievement at the aggregate level. This could lead to lower efficiency and thus a potential trade-off between the two objectives. However, the relationship between efficiency and equity is not that clear-cut. Research points to a number of policy approaches that can support both efficiency and equity objectives and which, therefore, warrant attention from policy makers considering where to invest resources. These policy approaches are also likely to be relevant to inform reflections in countries on how to allocate funding as they recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and face competing budget priorities in a time of deteriorating geopolitical and economic situation. Acknowledging that efficiency and equity can go hand in hand redirects the focus of policy debates from zero-sum conflicts towards enabling synergies between equitable education, better learning outcomes and the best use of the available resources (OECD, 2017[1]).

This chapter analyses some of these policy areas that can support both efficiency and equity in school education. The chapter is organised around four selected key themes:

First, this chapter discusses the importance of investing in high-quality early childhood education and care, and in particular 1) increasing participation for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, and 2) fostering process quality in settings to enhance the quality of children’s experiences and interactions.

Second, this chapter analyses trade-offs in teacher policies and the critical importance of investing in teacher quality, with a particular focus on 1) making a career in schools attractive for high-quality candidates including adequate compensation, and 2) working towards an equitable and effective distribution of teachers across schools.

Third, this chapter delves into the structural factors influencing students’ transition through the system and efforts to reduce the risk of educational failure and dropout. Educational failure and dropout typically result from a lack of co-ordination and early intervention, grade repetition practices or early tracking, which can lead to inefficiency and inequity.

Fourth, the chapter concludes with a discussion of strategies to effectively manage and adapt school networks to changing demand, while safeguarding quality, equity and well-being. In this context, the chapter also investigates the complementary strategies that are necessary to support access to educational opportunities for students in remote rural areas.

Policy makers worldwide recognise the myriad of advantages of ECEC

High-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) holds tremendous potential for children, families and societies. Clear evidence spanning research from neuroscience to economics demonstrates that ECEC can give all children a stronger start by supporting their development, particularly those from less privileged backgrounds (OECD, 2021[2]; OECD, 2018[3]).

Children’s early learning and development is closely connected across domains. Cognitive, social and emotional, as well as self-regulatory skills grow together during early childhood, with gains in one area contributing to concurrent and future growth in other areas (OECD, 2020[4]). Participation in high-quality ECEC supports children’s development in all these areas, with implications for learning beyond early childhood. For example, children in Denmark who participated in higher-quality ECEC performed better on a written exam at the end of lower secondary schooling (ten years after their ECEC participation) than their peers whose ECEC experiences were of lower quality (Bauchmüller, Gørtz and Rasmussen, 2014[5]). Similarly, findings from the United Kingdom show that participation in high-quality ECEC is associated with stronger performance at the end of compulsory schooling, enough to generate a 4.3% increase in gross lifetime earnings per individual (Cattan, Crawford and Dearden, 2014[6]).

In addition to educational and economic benefits, quality ECEC also supports social and emotional well-being (see also Chapter 2 on the broader social outcomes of education for individuals and societies). In a sample from the United States, at age 15, adolescents reported fewer behavioural and emotional problems when they had participated in higher-quality ECEC (Vandell et al., 2010[7]). In the longer term, participation in ECEC positively predicts well-being across a range of indicators in adulthood, including physical and mental health, educational attainment and employment (Belfield et al., 2006[8]; Campbell et al., 2012[9]; García et al., 2020[10]; Heckman and Karapakula, 2019[11]; Heckman et al., 2010[12]; Karoly, 2016[13]; Reynolds and Ou, 2011[14]). Finally, societies benefit from high-quality ECEC in the long term through greater labour market participation and earnings, better physical health and lower crime rates (OECD, 2021[2]).

In this context, investing in high-quality ECEC pays off, and ECEC enrolments have been growing…

Investing in high-quality ECEC, while targeting it particularly to disadvantaged children, is therefore a fundamental policy lever for achieving both efficiency and equity in education (OECD, 2017[1]), although more research is needed on the specific types of investments that ensure ECEC delivers high rates of return (Rea and Burton, 2020[15]; Whitehurst, 2017[16]), and how to sustain gains in early childhood through investments in primary school and beyond (Johnson and Jackson, 2019[17]).

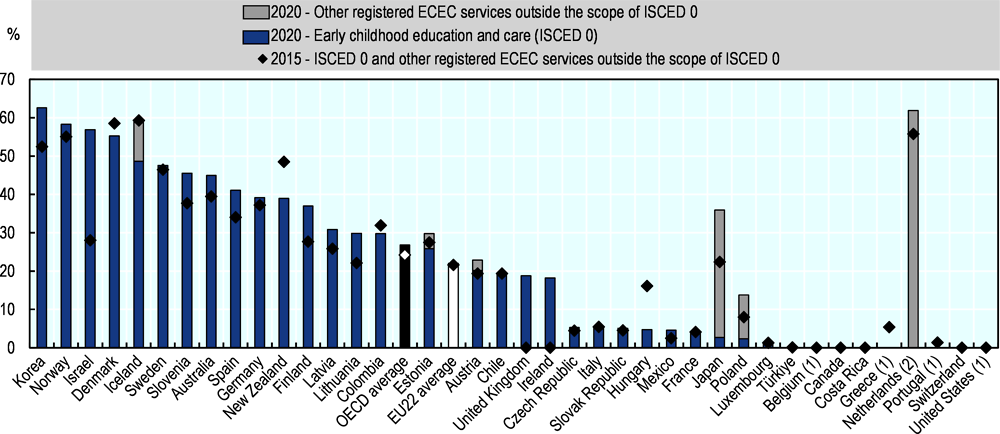

As awareness on the importance of ECEC has grown worldwide, OECD countries have expanded the provision of pre-primary education (ISCED 02) and targeted measures for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. As a result, enrolment rates in ECEC have increased, reaching universal or near-universal levels for children aged 3 to 5 in several countries, and in most countries in the year before primary school entry. ECEC enrolments of children under the age of 3 – who are growing and learning at a faster rate than at any other time in their lives – are also increasing across OECD countries, although enrolment rates for this age group are still more variable than for older children (Figure 4.1) (OECD, 2021[18]).

Yet children from disadvantaged backgrounds, who stand to gain the most from ECEC, still tend to participate less in ECEC…

ECEC is a powerful policy tool to reduce inequalities and help all children have strong foundations for learning and well-being. In general, however, children from socio-economically disadvantaged families are less likely than their more advantaged peers to participate in ECEC (OECD, 2017[20]; Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2016[21]).

Data from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 show that, on average across OECD countries, 86% of students from socio-economically advantaged backgrounds attended ECEC for at least two years, whereas this was the case for only 74% of their less advantaged peers (Figure 4.2). Importantly, the gap in ECEC participation between students of different socio-economic backgrounds did not change much on average across OECD countries between PISA 2015 and PISA 2018, suggesting that despite overall trends of growing participation in ECEC, inequities remain. However, these data must be interpreted with caution, as students reporting on their ECEC participation for PISA in 2018 attended ECEC settings more than a decade ago (OECD, 2021[2]).

These disparities not only deprive many disadvantaged children of the benefits of participating in high-quality ECEC, they also deprive their families of economic opportunities since caretaking activities hinder their participation in ongoing education or the labour market. The COVID-19 pandemic may have aggravated this participation gap: Rising unemployment in the first year of the pandemic has particularly affected women and mothers’ labour market participation, which has been a good predictor of enrolment rates in ECEC before the pandemic (OECD, 2021[2]).

This requires further strategies to raise ECEC participation for disadvantaged children, such as universal free access balanced across age groups

Possible strategies to provide equal access to ECEC and raise overall participation include increasing the provision of free ECEC, for at least some hours, ages, or targeted population groups. Universal free access to at least one year of ECEC is now common across OECD countries and having accessible, high-quality ECEC can encourage broad participation from diverse families. However, countries need to carefully balance their investments across different age groups (OECD, 2021[2]). Universal free access is typically targeted to pre-primary education, potentially limiting the available public resources to support participation of children under the age of three (OECD, 2017[20]). The expansion of free or subsidised ECEC, targeted to families who face income losses due to furlough or unemployment, may also help ensure that children can continue to engage in ECEC should their parents become unemployed (OECD, 2021[2]).

Alongside universal free access, governments can use other tools to encourage equitable participation in ECEC. This includes regulatory frameworks to foster high-quality public and private ECEC provision, or mechanisms to adapt ECEC settings to the needs of disadvantaged families (OECD, 2020[22]; Blanden et al., 2016[23]).

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of high-quality ECEC, funding for the sector has remained lower than for later stages of education

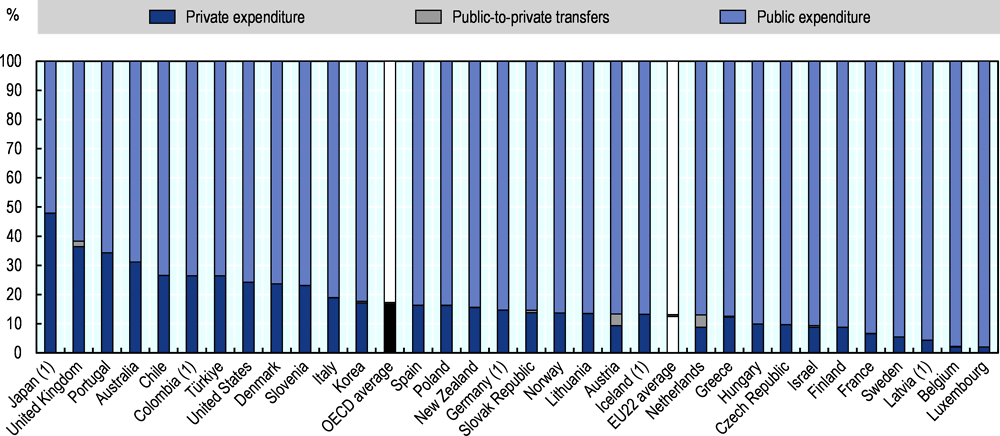

According to data from Education at a Glance, on average, OECD countries spent 0.9% of their gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018 on ECEC as compared to 1.5% and 1.9% of GDP on primary and secondary education, respectively (OECD, 2021[18]). In some countries, pre-primary education has a shorter duration than primary education, potentially justifying lower overall expenditures. However, the proportion of private spending in total spending is higher for pre-primary education than for primary education, highlighting the gap between funding that is needed in the sector and public investments (Figure 4.3) (OECD, 2021[2]). On average across OECD countries, private funding represented 29% of total expenditure on early childhood educational development (ISCED 01) and 17% on pre-primary education (ISCED 02) in 2018. At the primary level, by contrast, only 8% of expenditure on educational institutions came from private sources, on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[18]). Also, expenditure per child in pre-primary education is lower than spending per student at higher levels of education, on average across OECD countries, even if several countries, notably Nordic ones, combine strong investments per child with widespread access to ECEC (OECD, 2021[18]).

Besides fostering access to ECEC for disadvantaged children, investments in ECEC need to also advance quality in provision

Policy makers strive for a better understanding of what marks the success of public investments in the early years of education and how it can be improved. Research consistently underscores the importance of ensuring that ECEC is of high quality to unlock the full potential of investments in early education (OECD, 2021[2]). In particular, process quality has been identified as the primary driver for children’s development in ECEC (Melhuish et al., 2015[24]), which refers to children’s experience of ECEC and their interactions with other children, staff, space, materials, their families and the community (OECD, 2021[2]).

The complex nature of quality in ECEC requires multifaceted policy solutions. The OECD’s work on ECEC has highlighted five policy levers which are instrumental for building ECEC systems that can foster process quality: governance, standards and funding; curriculum and pedagogy; workforce development; data and monitoring; and family and community engagement (OECD, 2021[2]). The ECEC workforce is, of course, central to ensuring high-quality ECEC for all children. However, in part due to historical conceptions of childcare as an unpaid activity undertaken by women, ECEC staff is not always recognised for the professionalism that their work requires. Increasing qualification requirements can, in countries where they are low, be one policy option for raising the status of ECEC professionals and help attract stronger candidates to the sector (Box 4.1) (OECD, 2021[2]).

Higher qualification requirements, however, need to be accompanied by opportunities for existing staff to meet these new requirements through training and the recognition of prior learning. This requires granting time and funding to increase access to and engagement in professional development. To ensure that the demands on the workforce and wages are aligned in the long term, and to attract and retain high-quality staff, countries can set long-term objectives for improving salaries and career development opportunities (OECD, 2021[2]).

Several countries have employed a range of strategies to increase the number of qualified teachers in ECEC over time, such as setting higher standards, incentive mechanisms, or offering workplace education opportunities for staff working in the sector.

In Australia, since 2012, higher workforce requirements have been progressively introduced. Centre-based services with children in pre-primary education are required to ensure a minimum level of access to qualified early childhood teachers, based on service operating hours and the number of children attending each day. From 2020, services must ensure access to two early childhood teachers if 80 or more children are in attendance. Furthermore, requirements cover both teachers and assistants: half of the staff must hold or be working towards at least a short-cycle (Diploma level) tertiary qualification (ISCED 5), and the other half must hold or be working towards at least a post-secondary (Certificate III level) qualification (ISCED 4). In line with the progressive implementation of the regulatory requirements introduced in 2012, the qualification levels of early childhood teachers in the ECEC workforce have increased in Australia over recent years.

In Canada, many provinces and territories have recently set new standards for initial education. For example, in the province of Nova Scotia, the curricula of post-secondary programmes have been updated to meet the newly adopted teaching standards. The province also introduced a process of recognition of prior learning to provide individuals who have been working in the ECEC field for ten years or more with the opportunity to demonstrate that they have acquired the necessary knowledge and skills to obtain an ECEC qualification.

In Ireland, new qualification requirements have been introduced in the past years, as well as incentives for ECEC centres to hire staff with higher qualifications. Teachers – so-called “lead educators” in the Early Childhood Care and Education programme (for 3 to 5-year-olds) – are now required to have an ISCED 5 diploma at the minimum. However, centres with teachers who hold a university degree (ISCED 6) in early childhood receive higher funding. The proportion of ECEC staff (working with children of all ages) who are graduate teachers has increased in the last decade, rising from 12% in 2012 to 34% in 2021. For all staff who work directly with children, the minimum requirement is a major awarded in ECEC at ISCED 4.

Source: OECD (2021[2]), Starting Strong VI: Supporting Meaningful Interactions in Early Childhood Education and Care, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f47a06ae-en.

Teachers are the most important resource in schools, and there is solid evidence showing that teachers can have long-term impacts on adult outcomes

Teachers are arguably the most important resource in schools. There is a solid evidence base indicating that teachers are key in improving learning opportunities for students, likely more than anyone else in children’s lives outside their families, and that they can have long-term impact on adult outcomes, such as earnings and tertiary education attendance (Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff, 2014[25]; Rivkin, Hanushek and Kain, 2005[26]; Rockoff, 2004[27]). Recent research has also documented teachers’ impact on other desirable outcomes, including students’ behaviours at school, such as attendance and drop-out (Liu and Loeb, 2019[28]; Gershenson, 2016[29]; Koedel, 2008[30]), and socio-emotional skills, such as resilience, growth mindset and self-efficacy (Kraft, 2019[31]; Blazar and Kraft, 2016[32]; Jennings and DiPrete, 2010[33]).

Insufficient investments in the teaching workforce, then, risk creating challenges to quality, equity and efficiency in school education in the long run. Spending reforms driven by reductions in teachers’ salaries or cuts to professional development may make a career in schools less attractive and motivating, and thus make it more difficult to recruit qualified staff (OECD, 2017[1]). Effective human resource policies, by contrast, develop attractive and stimulating careers, distribute teachers effectively and equitably, and support powerful professional learning so teachers maintain the quality of their teaching (OECD, 2019[34]).

Nevertheless, many countries face a number of shared challenges. Notably, careers, salaries and working conditions often remain unattractive and act as a barrier for talented individuals to pursue or remain in the teaching career (OECD, 2019[34]). According to data from Education at a Glance, teacher attrition, that is the proportion of teachers leaving the profession during their career, exceeded 8% in half of the countries with available data for 2016 (OECD, 2021[18]). Moreover, the most effective and experienced teaching staff are often not matched to the schools and students that need them the most (OECD, 2019[34]).

Further challenges relate to the quality of initial teacher education programmes, which may not adequately screen candidates and prepare them for a career in teaching. This can result in candidates dropping out of teacher education programmes or graduates not going into teaching at the end of their studies, creating considerable inefficiency. Finally, teachers’ time can be used more or less effectively, which influences the cost and the quality of education (Boeskens and Nusche, 2021[35]).

But countries face important trade-offs in their human resource policies, which are also relevant as countries respond to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The experience of countries suggests that the resource implications of teacher policies are often underestimated at the design stage. Human resource policies must recognise important resource trade-offs and be implemented in ways that are sensitive to the unique contexts faced by schools. For instance, policies that require smaller class sizes, longer teacher working hours or less instructional time per teacher all increase the number of teachers required and raise per-student spending (OECD, 2019[34]).

School systems have also been facing these trade-offs as they have sought to respond to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a Survey on Joint National Responses to COVID-19 School Closures suggested, nearly half of countries surveyed (48%) had recruited temporary teachers and/or other staff to support student needs in at least one level of education for the school year 2020/21. These additional teacher resources were deployed to ensure substitution for teachers on sick leave, to facilitate social distancing through class size reductions as well as for remedial teaching. Some countries decided to increase teachers’ salaries to compensate for additional workload (Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia), while others increased teachers’ working time to give schools the autonomy to reduce class size or provide tutoring (Austria) (OECD, 2021[36]).

The size of classes is a much-debated topic, yet does not show strong potential for efficiency gains, except for younger and disadvantaged students

Teacher-student ratios and class size are controversial topics in education policy. Strategies targeted at reducing class size are generally supported by arguments related to closer ties between teachers and students, increased time on task and more attention paid to individual students (OECD, 2017[1]). Data from TALIS 2018 show that smaller classes tend to be associated with more actual teaching and learning time, but that they are not related to key indicators of teaching quality, such as the use of cognitive activation practices and teachers’ reported self-efficacy in teaching (OECD, 2019[37]).

Moreover, any potential benefits of small classes need to be weighed against other potential investments such as improvements in professional development and working conditions. Organising students in smaller classes is an expensive policy since it requires more staff resources per student. In other words, there may be a policy trade-off between investing in more teaching staff to reduce class size and investing in better human resources and new approaches to teaching and learning (OECD, 2017[1]).

Given the high cost of class size reduction policies, they appear comparatively less efficient than other interventions to support student learning (Rivkin, Hanushek and Kain, 2005[38]). Some high-performing school systems, such as Shanghai and Singapore, have chosen to reduce teacher workloads instead in order to free time for professional development (Jensen et al., 2012[39]). While the effects of class size on students’ achievement are still debated (Santiago, 2002[40]), there is substantial evidence pointing to strong positive effects of small classes on the learning of particular student groups. This includes learners in their earlier years and from disadvantaged backgrounds (Krueger, 1999[41]; Angrist and Lavy, 1999[42]; Chetty et al., 2011[43]; Dynarski, Hyman and Schanzenbach, 2013[44]). This indicates that additional teacher resources – for example in school systems with declining student numbers – should be allocated to disadvantaged students and students in pre-primary and primary education, who benefit the most from such interventions (OECD, 2017[1]).

For school systems more broadly, there still seems to be room for more creative solutions in organising smaller student groups. For example, teachers can be encouraged and supported to set up their classroom space in a way that is conducive to more individualised and active learning approaches. School leaders can also be given increased discretion to use staff more flexibly within schools and thus enable teachers to work with smaller groups at least part of the time (OECD, 2019[37]).

Attracting, retaining and motivating talented individuals for a teaching career is a pressing concern that requires attention to both intrinsic and extrinsic factors

Attracting and retaining the best teachers, motivating them throughout their careers and enabling them to use their talents effectively to foster student learning and well-being is at the heart of what makes a successful school system (OECD, 2019[34]).

Evidence from TALIS 2018 suggests that although individuals choose a career in education for a variety of reasons, the great majority of serving teachers were motivated by a strong commitment to public service and the social impact of teaching (OECD, 2019[37]). Working with young people and inspiring them to learn are powerful sources of intrinsic motivation. At the same time, a substantial number of teachers report that extrinsic factors, including career prospects (61%), job security (71%) and the ability to reconcile their work schedule and private life (66%) also mattered for their decision to join teaching. Moreover, working conditions, salaries and administrative workload represent the top concerns of practicing teachers in many OECD countries (OECD, 2019[37]).

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are thus closely intertwined, and countries need to consider both when seeking to raise the attractiveness of a career in schools, to motivate school staff and to enable them to support student learning. Countries need to make teaching a financially rewarding career, while also making it intellectually satisfying and allowing teachers to focus on their instruction (OECD, 2019[34]).

Comparatively low salary levels can be one factor contributing to teacher shortages and high rates of turnover

While remuneration is only one among many factors that can render a profession attractive, salary levels, the structure of salary scales and the factors that determine salary progressions are critical policy levers that need to be considered for the supply, retention and motivation of teachers (OECD, 2019[34]).

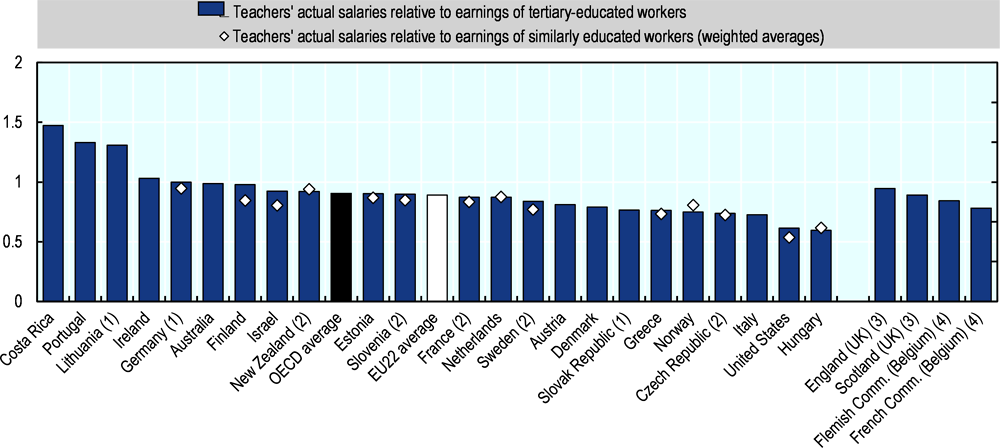

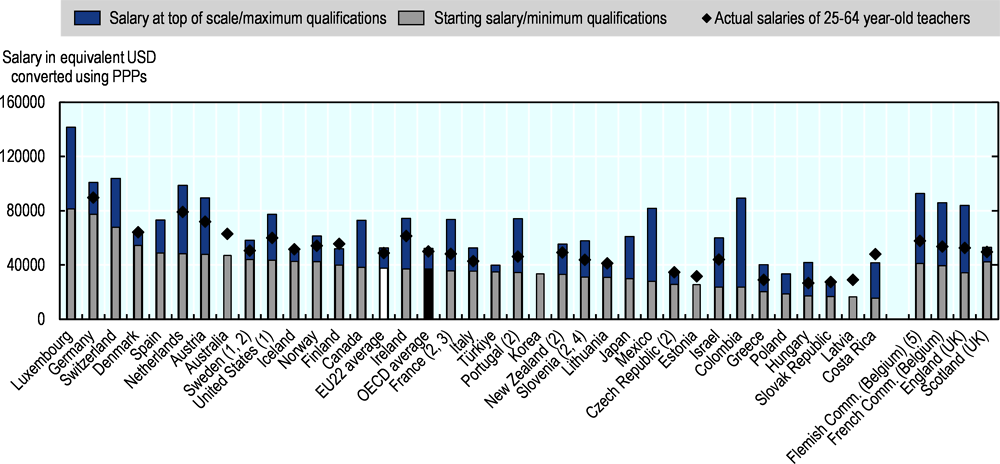

It is widely recognised that teachers’ remuneration should be competitive with that of similarly educated adults working in comparable occupations in order to attract and retain high-potential candidates. Yet, according to OECD Education at a Glance, teachers’ actual salaries are lower than those of similarly educated workers in almost all countries with available information, although salaries tend to increase with the level of education taught (Figure 4.4). In 2020, pre-primary teachers’ average salaries amounted to 81% of the full-time earnings of tertiary-educated adults between the ages of 25 and 64, while primary teachers earned 86% of this benchmark, lower secondary teachers 90%, and upper secondary teachers 96%. Teachers’ relative earnings nevertheless vary widely across countries. In Costa Rica, Lithuania, Portugal and Ireland teachers earn more than other tertiary-educated adults at all levels of education, while teachers at some levels of education in Hungary and the United States earn only two-thirds or less (OECD, 2022[19]).

Comparatively low salaries are frequently regarded as one of the factors contributing to teacher shortages and a lack of qualified candidates for the profession. Uncompetitive salaries may also contribute to teacher attrition as some evidence suggests that teachers’ salaries (and the opportunity cost of forgone wages from a career outside of teaching) affect their likelihood of leaving the profession (Falch, 2011[45]), particularly in the early years of their careers (Hendricks, 2014[46]; Murnane, Singer and Willett, 1989[47]). Competitive salaries may therefore also support schools in reducing high rates of turnover that can adversely affect student achievement and that tends to particularly affect disadvantaged schools (Ronfeldt, Loeb and Wyckoff, 2013[48]).

Several countries where teachers’ salaries were significantly lower than those of similarly educated workers have considered reducing this gap to make teaching more attractive (Box 4.2). Yet, while absolute and relative salary levels are an important factor shaping the financial attractiveness of a career in schools, other aspects associated with remuneration should also be considered when assessing their competitiveness. For instance, in many countries, teachers are civil servants and enjoy a high level of job security or benefits like pensions, tax exemptions, family allowances and annual leave that workers in comparable private sector positions lack. The competitiveness of teachers’ salaries, therefore, needs to be assessed against a relevant comparison group, bearing in mind both financial and non-financial benefits (OECD, 2019[34]).

In the Czech Republic, poor salaries and working conditions have been identified as drivers of the low social status and attractiveness of the teaching profession. Following an initial increase in teachers’ salaries by 22% in real terms between 2009 and 2014, the government made it a priority to continue raising salaries to tackle staff shortages as part of its Strategy for Education 2020, adopted in 2014. As a result, teachers’ salaries have risen annually since 2015, with an 8% increase of teaching staff in 2016. In 2017, the government implemented a programme to increase salaries by 15%. Following pressure from and negotiations with regional teacher unions, the 2019 education budget earmarked CZK 95 billion for teacher salaries, an increase of CZK 16.1 billion from 2018 and constituting an average teacher salary increase of 10%. The country’s new sector strategy (Strategy 2030+) foresees further increases in teachers’ wages, both relative to the average wage in the national economy and the average salary of university-educated workers. Actions considered in the strategy also include the review of the salary system and increasing the share of funding for bonus-pay components so that school leaders can reward teaching quality (MSMT, 2020[49]; OECD, 2020[50]).

In Estonia, ensuring teachers’ satisfaction and their image in society was at the core of the Lifelong Learning Strategy 2014-2020. The government’s actions included, among others, salary raises and reforms in work organisation to improve the reputation of the teaching profession. To attract the best candidates, average salaries of teachers were adjusted to make them consistent with the qualifications required and the set of skills developed. Novice teachers’ salaries were specifically targeted to promote the appeal of a career in teaching for young people. The salary system for teachers also incorporated incentives for participation in professional development, with the possibility of taking half a year away from teaching to fulfil definite developmental assignments (OECD, 2020[51]).

In Sweden, the government introduced the National Gathering for the Teaching Profession in 2014, which contained measures to avoid teacher shortages and boost the attractiveness of the profession. This initiative included salary increases and more rapid wage progression for teachers, linked to their competences and development. In 2016, this was followed by the Teacher Salary Boost initiative (Lärarlönelyftet), which rewarded teachers for participation in professional development programmes. Furthermore, the government sought to encourage entry to the profession by promoting alternative pathways to teaching and increasing government grants for new teachers. Grants were also implemented to improve working conditions and career opportunities, thereby increasing retention. These measures were complemented by an information campaign (För det vidare) to attract more people to teaching, encourage retention and boost the social prestige of the profession (OECD, 2020[51]).

Source: OECD (2020[51]), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en; (OECD, 2020[50]), Education Policy Outlook 2020: Czech Republic, https://www.oecd.org/education/policy-outlook/country-profile-Czech-Republic-2020.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022); MSMT (2020[49]), Strategy for the Education Policy of the Czech Republic up to 2030+, https://www.msmt.cz/uploads/brozura_S2030_en_fin_online.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

The design of the salary scale and criteria for salary progression also need to be considered when seeking to raise the attractiveness of a career in teaching

Apart from the competitiveness of teachers’ lifetime earnings, policy makers must pay attention to the distribution of earnings over the course of the career and the factors that determine salary progression. Higher starting salaries, for example, may need to be weighed against the benefits of greater pay raises over the course of the career. Indeed, many countries face the dual challenge of providing competitive starting salaries to attract high-calibre entrants to the profession while also seeking to retain, motivate and recognise experienced, high-quality teachers through salary increases (OECD, 2019[34]).

According to Education at a Glance, the range of teachers’ pay scales and their slope (i.e. the rate at which salaries increase over the course of the career) vary significantly across OECD countries with available data. In a number of countries, teachers earn comparatively little as they start their career but experience a stronger salary progression as they gain further qualifications or seniority. In Chile, Costa Rica, Hungary, Israel, England (United Kingdom), Korea and Mexico, for example, top-end salaries can be more than 2.5 times as high as starting salaries. In Colombia, salaries at the top of the scale are more than three times as high as starting salaries. By contrast, the salary scales in countries like Denmark, Germany and Spain, which offer some of the highest starting salaries, are comparatively compressed (Figure 4.5) (OECD, 2022[19]).

…but there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the design of effective salary scales…

However, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the design of effective salary scales. Instead, policy makers’ decisions need to reflect the specific challenges their country has to address as well as their local labour markets. While a failure to attract graduates to the profession might call for higher starting salaries, high attrition rates among mid-career teachers may indicate the need for a more attractive progression of earnings. Likewise, broader economic developments, such as the level of private sector wages or unemployment rates, can affect whether, and up to which point, higher starting salaries can be an effective means to attract high-performing candidates and what forms of salary progression are best suited to recognise and amplify teachers’ profound impact on student learning and development (OECD, 2019[34]).

Compressing the salary scale can free up resources to increase starting salaries at the expense of salaries of more experienced staff. This might help to attract more students to teaching and reduce attrition in the early years of teachers’ careers. Austria’s 2015 teacher service code provides an example of a reform towards a more compressed salary scale (Box 4.3). By contrast, increasing the rate at which salaries rise over the course of the career can create space to provide higher salaries at the top end of the scale. Such scales may serve to retain and motivate more experienced staff or offer a wider scope for salary differentiation among teachers (OECD, 2019[34]).

In 2015, Austria implemented a new teacher service code which has been mandatory for all teachers entering the profession since 2019/20. It implied a compression of the salary scale, thus offering more attractive starting salaries while reducing top-end salaries, keeping the expected lifetime earnings of teachers roughly constant. The changes have been accompanied by a raise in qualification requirements for new teachers in provincial schools and an increased teaching load in federal schools.

It is expected that flattening the salary structure in Austria (whose slope had been considerably steeper than the OECD average) may lead to an increase in spending in the medium term until the more highly paid senior teachers - who have a right to continue serving under the old salary system – will retire. Part of this effect may be offset by longer teaching hours and the new service code’s overtime regulations. Fewer teachers than anticipated chose to enrol under the new service code during the transition period (2015-2019) in which its adoption was voluntary.

Note: In Austria, responsibilities for school education differ between so-called federal schools and provincial schools. Federal schools (Bundesschulen) comprise academic secondary schools as well as upper secondary vocational schools and colleges (ISCED 2-3). Provincial schools (Landesschulen) include primary schools, general lower secondary schools, New Secondary Schools, schools for students with special education needs, pre-vocational schools and part-time upper secondary vocational schools (ISCED 1-3).

Source: OECD (2019[34]), Working and Learning Together: Rethinking Human Resource Policies for Schools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b7aaf050-en.

… and significant implementation challenges need to be anticipated when reforming compensation systems

Compensation reforms always involve a degree of uncertainty about the size and distribution of their benefits and are likely to cause resistance among those who fear to lose out, whether in absolute or relative terms. They therefore require an open dialogue with and involvement of stakeholders, including teacher unions. To build and sustain trust for the implementation of compensation reforms, they must be underpinned by clear communication, consensus building, and a process for prioritising competing claims on resources. Failing to effectively engage stakeholders at the design stage of reforms can come at a high cost as shown by examples of OECD countries that had to delay or abandon compensation reforms due to stakeholder resistance.

The experience of OECD countries also highlights the importance of anticipating the costs and challenges involved in compensation reforms. For example, although adjusting the slope of salary scales and shifting resources towards their lower or upper end can be budget neutral in theory, fiscal consequences are often hard to predict and reforms may involve significant transition costs over the course of their implementation. Finally, policy makers need to bear in mind the inertia of reform processes and the significant amount of time that it can take for a change in teachers’ compensation systems to reach all or even just a majority of the profession (OECD, 2019[34]).

Some countries have sought to strengthen the link between teachers’ compensation and their performance to promote quality teaching, which is fraught with difficulties

In addition to linking salaries to seniority, many systems seek to incentivise continuous improvement by differentiating compensation based on teachers’ education and training or responsibilities. Other forms of differentiated pay have aimed to more explicitly link teacher pay to their assessed effectiveness. For instance, starting in 2006, the US Department of Education competitively awarded Teacher Incentive Fund grants to school districts to fund the development and implementation of performance pay programmes aimed at teachers and principals. Participating districts were required to use measures of student achievement growth and at least two observations of classroom or school practices to evaluate effectiveness (OECD, 2019[34]).

In theory, performance-based compensation is meant to motivate teachers to improve their practice and raise students’ achievement by rewarding effective teaching (OECD, 2019[34]). However, research from different contexts has underlined the difficulty of measuring performance at the level of individual teachers and the potential. It has also showed potential perverse effects associated with incentive schemes to improve teacher performance , such as teachers narrowing the curriculum or reducing their efforts on tasks not explicitly rewarded by the programme (Ballou and Springer, 2015[52]; OECD, 2013[53]; Papay, 2011[54]; Rothstein, 2010[55]). An excessive reliance on extrinsic incentives may also undermine teachers’ intrinsic motivation and have a negative impact on collegial relationships (Bénabou and Tirole, 2003[56]; Frey, 1997[57]).

As an alternative, linking salaries to career advancement creates a more indirect link between teachers’ growing expertise and their compensation and can address some of the challenges associated with conventional performance pay (Box 4.4). First, this can combine extrinsic rewards for high performance (in the form of salary increases) with intrinsic rewards in the form of professional opportunities and responsibilities that grow in line with teachers’ knowledge and skills. Second, this offers both beginning and experienced teachers realistic goals based on their current position on the career ladder and a clear pathway to achieve them. Implementing such systems may require countries to further develop and integrate their teaching standards, appraisal systems, career structures and salary scales (OECD, 2019[34]).

Colombia’s new teacher career structure, introduced in 2002 and applicable for teachers appointed following its introduction, illustrates how indirect links between appraisal and compensation can be established. In contrast to the seniority-based system in place for teachers appointed prior to 2002, teachers need to undergo a system of Diagnostic and Formative Evaluation (Evaluación de Carácter Diagnóstico Formativo, ECDF) to advance their career and reach the next step of the salary scale. While initially based on a written assignment, the evaluation process was reformed in 2015 to measure teachers’ effectiveness in the classroom more directly. The process has since focused on peer evaluations based on video observations, on identifying professional development needs and providing access to professional development opportunities for teachers. While the details of the process have been subject to frequent negotiations since it was introduced (e.g. concerning the evaluation method’s reliability), the system signals a clear commitment to strengthening the indirect linkages between teachers’ performance and their compensation.

Similarly, Chile uses a certification process (Sistema de Reconocimiento) to regulate teachers’ progression across the five stages of their career structure (Carrera Docente) based on competencies specified in the national teaching standards (Marco para la Buena Enzeñanza). Progression through the career structure is linked to better remuneration through specific salary supplements (Asignación por tramo de desarrollo profesional docente) and a higher base salary (Bonificación de Reconocimiento Profesional). It also provides access to new professional opportunities, such as teacher networks, and professional learning to improve practice. The certification process includes a standardised written assessment, the evaluation of teachers’ professional portfolio through external markers, as well as classroom observation. While advancing to the two highest stages of the teaching career (Expert I and Expert II) is voluntary, teachers are expected to move from the first stage (Initial) to the second or third (Early, Advanced) after four to eight years. This also serves as a means to make underperforming teachers leave the profession if they fail the examination more than twice.

Source: OECD (2019[34]), Working and Learning Together: Rethinking Human Resource Policies for Schools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b7aaf050-en.

Inequities in the distribution of teachers are problematic in many countries…

Inequities in the distribution of staff across schools in different socio-economic circumstances mark a problem in many countries as a rich research literature and data from the OECD have established (OECD, 2018[58]; OECD, 2019[34]). Data from PISA 2015, for example, show that teachers in the most disadvantaged schools are less qualified or experienced than those in the most advantaged schools in more than a third of the participating school systems. Further, the gaps in student performance related to socio-economic status are wider when fewer qualified and experienced teachers work in socio-economically disadvantaged schools (OECD, 2018[58]).

More recent data from TALIS 2018 similarly show that, on average across OECD countries, novice teachers tend to work in more challenging schools that have higher concentrations of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes and immigrant students (Figure 4.6) (OECD, 2019[37]). As new teachers often struggle with classroom challenges in the initial phase of teaching (Jensen et al., 2012[59]), this may reduce their sense of efficacy and make them more likely to move schools or to leave teaching altogether.

… which can be driven by a number of factors, including recruitment processes and regulations as well as staff preferences

There are concerns that, while facilitating a more effective matching of staff and workplace, giving schools autonomy in the recruitment of their teachers may lead to greater disparities in staff qualifications and experiences among schools. Teacher allocations through higher-level authorities, by contrast, may help steer a more equitable teacher distribution across advantaged and disadvantaged schools and help fill hard-to-staff positions in schools (OECD, 2019[34]).

International data nevertheless suggest that inequities in the distribution of teachers can be observed both in systems with higher-level teacher recruitment and those with school-based recruitment (OECD, 2018[58]). This indicates that an effective and equitable distribution of teachers depends not only on the level of decision making but also on recruitment processes and teacher incentives and preferences. In a number of systems, teachers’ interests rather than students’ needs drive the deployment of teachers and make it difficult to match the mix of teachers’ experiences and skills to school contexts. For example, in centralised recruitment systems, the preferences of teachers with the highest rank may be prioritised in choosing schools to work at. In decentralised systems, schools or sub-central authorities may have to safeguard teachers’ statutory rights, such as permanent contracts or higher levels of seniority, when recruiting staff (OECD, 2019[34]).

… and be potentially addressed through both financial and non-financial incentives

Some school systems have introduced financial incentives to channel teachers to the schools that need them the most. For instance, such measures include higher salaries in schools enrolling large proportions of students from disadvantaged backgrounds, differential pay for particular expertise, or scholarships and subsidies for working in disadvantaged schools (Box 4.5).

Chile’s government has designed different awards that provide a financial bonus for high-performing teachers choosing to work in disadvantaged schools. The Asignación de Excelencia Pedagógica (AEP) programme sought to reward the most effective teachers and to increase retention in the teaching profession. The programme was in place between 2002 and 2021 and incorporated a monetary bonus for teachers working in disadvantaged schools since 2012. An evaluation of the programme suggested that the incentive was not sufficient to redirect high-performing teachers to disadvantaged schools but was effective in retaining quality teachers in high-need schools. Since 2017, a separate monetary incentive has been in place (Asignación de Reconocimiento por Docencia en Establecimientos de Alta Concentración de Alumnos Prioritarios), which is also focused on attracting and retaining teachers to work at schools with a large proportion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In 1981, France established the Zones d’Éducation Prioritaire (ZEP), a compensatory education policy directing additional resources to disadvantaged schools. In 1992, for example, an annual bonus of EUR 600 was awarded to teachers working in ZEPs. The policy scheme has substantially evolved since then. For instance, since September 2015, teachers working in schools serving disadvantaged communities are awarded an annual bonus, which may vary between EUR 1 734 and EUR 2 312 (gross amount). Since September 2019, teachers working in schools in the most deprived areas (REP+) are awarded an annual gross salary bonus of EUR 4 646.

Source: OECD (2020[51]), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en.

In some contexts, monetary incentives have shown promising results to deploy teachers where they are needed the most (Steele, Murnane and Willett, 2010[60]; Clotfelter et al., 2008[61]). But such policies will work differently depending on the design and size of the incentives and the general framework for teacher employment and career progression. The financial incentive for working in disadvantaged schools in France described in Box 4.5 , for example, did not show positive results. This highlights that the size of the financial bonus and the perception of the policy are crucial to achieve the policy’s objectives (Prost, 2013[62]). Financial incentive schemes therefore require adequate evaluation and monitoring.

Of course, non-financial incentives also matter. For example, recognising experience in difficult or remote schools for teacher career development is a further option. Professional factors, such as opportunities to take on extra responsibilities and to engage in research and innovation, also need to be considered as do working conditions, such as preparation time, leadership, collegiality, accountability demands, class size or facilities. Hence, it is equally important to ensure that schools in difficult contexts provide attractive conditions for staff to work in (OECD, 2019[34]).

Educational failure entails high costs for individual students, and is a major source of inefficiency in education systems

Formal education is a cumulative – if not linear – process. When students’ progression through school is compromised by knowledge gaps or disrupted by grade repetition, students are more likely to drop out, fail to progress to tertiary education and to face lower prospects in the labour market (OECD, 2018[63]). When students do not progress through the system as expected and leave school with insufficient knowledge, skills and competencies, this has a high cost for school systems and individuals, constituting an important source of inefficiency in many countries (OECD, 2017[1]). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing the urgent needs of students who may have left school early or are at increased risk of doing so will be a critical educational and economic priority in some contexts, for example through high-quality second-chance or early acceleration programmes (Box 4.6).

Second chance and early acceleration programmes are specific types of interventions for students who have struggled or are struggling to make successful transitions through secondary education and into post-secondary education or the labour market. They provide a different curriculum and structure to re-engage students, rather than aiming to better support students in the regular curriculum.

Second-chance programmes are a common way of addressing students who have dropped out of school, but later express interest in gaining skills and credentials at the secondary level as adults. These programmes can tackle skill gaps and school failure in a variety of ways including literacy and numeracy remediation, course repetition through online or in-person classes, test-based competency demonstrations and work experience.

For example, in France, a network of second chance schools (Écoles de la 2e Chance, E2C) provides practical training for early school leavers. The training, which targets 16- to 25-year-olds without qualifications, focuses particularly on individualised learning pathways and practical work experience. As part of the government’s investment plan for 2018-2022 (Grand Plan d’Investissement), the Ministry of Labour provides financing for places in the programme between 2019 and 2022, for the development of the network’s information systems, and the development of a skills-based approach.

In Denmark, a new type of educational programmes (Preparatory Basic Education and Training, FGU) was launched in 2019 to rethink and strengthen second-chance education and lower the share of youth not in education or training by 50% until 2030. This type of programme is offered by dedicated institutions serving a number of schools and is embedded within the youth initiatives of the country’s 98 municipalities. It offers various educational tracks, a strong element of guidance and counselling and new pedagogical approaches to support youth under 25 in entering upper secondary education or the labour market.

An alternative to the traditional second-chance programme is to alter a student’s trajectory before they experience failure in the first place. These types of early intervention programmes are often premised on an idea of acceleration rather than remediation. Though such strategies vary in nature, a common structure involves providing students with the opportunity to earn tertiary credits and credentials while enrolled in secondary school, coupled with the opportunity for embedded employer internships. Students are assigned professional mentors, visit multiple workplace environments on learning missions and access paid or unpaid internships. In some cases, graduates from these early acceleration programmes are given priority in job opportunities with partner private employers.

One such Early College High School in New York City (United States) is the Pathways in Technology Early College High. “The school provides students with an enriched curriculum that is aligned with actual employment opportunities with industry partner IBM and that enables them to earn both a high school diploma and a cost-free Associate in Applied Science (AAS) degree in six years. Students have professional mentors, substantive workplace experiences … and internships.”

Source: OECD (2018[63]), Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306707-en. EPALE (2019[64]), Preparatory basic education and training, https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/blog/preparatory-basic-education-and-training (accessed on 31 January 2022); Réseau E2C France (n.d.[65]), Qui sommes nous?, https://reseau-e2c.fr/qui-sommes-nous (accessed on 31 January 2022).

Many school systems face challenges in supporting student transitions, potentially leading to educational failure, inefficiency and inequity in resource use

Students’ experiences as they progress through the school system differ markedly across OECD countries, but vertical (that is upward) transitions play an important role in every student’s educational experience, often right from the beginning. In any school system, students accumulate years of educational attainment before leveraging these educational milestones to seek success in the labour market (OECD, 2018[63]).

However, many school systems face challenges in supporting students in their transitions through the system. Practices and policies to facilitate transitions from early childhood education and care to primary school providers vary widely. Also, school systems across the OECD have struggled finding the best ways to address the unique learning and social needs of students transitioning from primary into lower secondary education. Lastly, the transition between lower and upper secondary education is often one of the most fraught, frequently coinciding with the end of compulsory schooling (OECD, 2018[63]).

Where the organisation of the educational offer fails to support students’ smooth progression through the system and to guide them to programmes that correspond to their interests, this can lead to disengagement, educational failure and skill mismatches resulting in an inefficient and inequitable use of school resources. Smooth transitions, on the other hand, facilitate human capital development, ease entry into the labour market and reduce costs associated with youth unemployment and poor adult health outcomes (OECD, 2018[63]).

Greater co-ordination between educational levels and sectors can have benefits for students’ transitions through the system

Accomplishing smooth transitions for students requires careful co-ordination between the different and oftentimes fragmented levels and sectors of school education as well as their responsible governing bodies. For instance, early childhood education and care and primary education tend to be more locally managed than secondary education, which tends to be the responsibility of central governments. Enhancing the co-ordination between different levels of education yields efficiency, quality and equity improvements:

First, the effective co-ordination of the educational offerings can reduce the duplication of educational services, reinforce professional collaboration and supervisory capacity.

Second, it can facilitate and incentivise the sharing of resources, such as facilities and materials, between schools providing different levels of education and their governing bodies.

Third, co-ordination can help to better articulate the curricular and pedagogical offer, to facilitate the progression of students throughout the system, to allow them to integrate skills acquired at each level of education and to minimise reasons to drop out of school (OECD, 2018[63]).

Designing explicit transition programmes or combining different levels of schooling into a single organisation in areas with high rates of early school leaving can also help to ease vertical transitions for all students. More generally, the configuration of years and levels of education will affect the nature and ease of students’ transitions as well as the extent to which services, facilities and materials can be efficiently shared. Policy makers should therefore assess the relevant curricular options in consultation with stakeholders and reflect on the best configuration of years and levels of education (OECD, 2018[63]):

For example, several studies in the United States have found that entirely eliminating the transition between primary and lower secondary schooling by keeping students in the same school up to eighth grade is beneficial for student outcomes (Rockoff and Lockwood, 2010[66]; Schwerdt and West, 2013[67]).

In Sweden, a reform in 1994 aimed at integrating grades seven to nine in locally run basic schools, led students to keep attending smaller schools closer to their homes, while having no significant impacts on educational outcomes (Holmlund and Böhlmark, 2017[68]).

A greater integration of different levels of education can also be achieved through an alternative administration of schools and curricula. Colombia and Portugal, for example, have organised their educational provision in school clusters which group schools offering different levels of education. This enables students to complete their entire schooling within the same extended school community if they wish so and allows for a more efficient resource use (OECD, 2018[63]).

High rates of grade repetition challenge efficiency and equity in some countries…

Students’ vertical progression through the school system is also affected by institutional factors and educational regulations, such as academic standards, promotion examinations, grade repetition practices, or structures to support struggling learners. School systems must constantly navigate a tension between adopting policies intended to ensure adequate student learning through imposing high standards for students’ knowledge and skills, and policies that do not unnecessarily inhibit students’ vertical progression (OECD, 2018[63]).

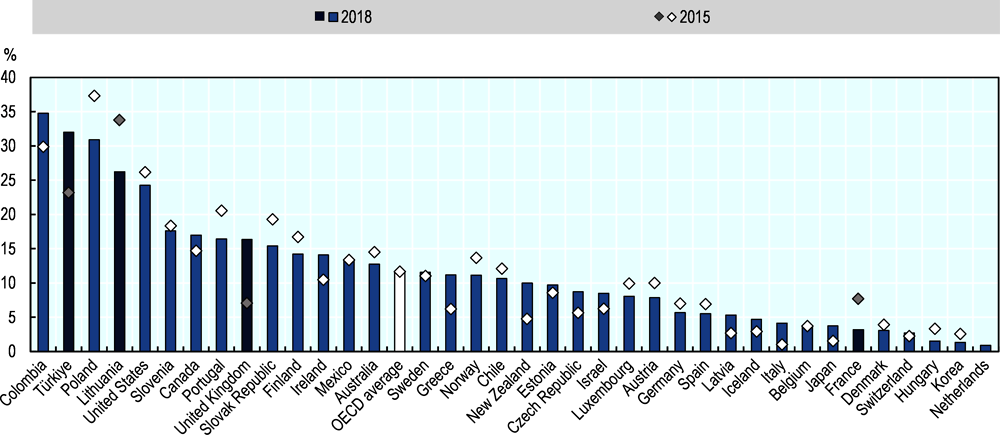

Whether students acquire specific academic skills may or may not determine whether they progress from one year to another, depending on system policies and cultural contexts (Goos et al., 2013[69]). Norway and Japan represent extreme examples among OECD countries, where – according to data from PISA 2018 – there is no grade repetition at all. In contrast, 41% of 15-year-olds in Colombia, 32% of students in Luxembourg and 31% of students in Belgium had repeated a grade at least once by the time they reached the age of 15 (OECD, 2020[70]).

International evidence provides no support for systematic grade repetition practices. Research clearly shows that students who repeat years do worse on a host of measures than students who have never repeated (Ikeda and García, 2014[71]). The evidence points to worse – or at best mixed outcomes for repeaters, which may be partially explained by the fact that year repetition is rarely accompanied by a modified curriculum or additional instructional resources (Schwerdt, West and Winters, 2017[72]; Allen et al., 2009[73]; Jacob and Lefgren, 2004[74]; Jimerson, 2001[75]; Jimerson, Anderson and Whipple, 2002[76]).

… as it is a costly practice for school systems and individuals

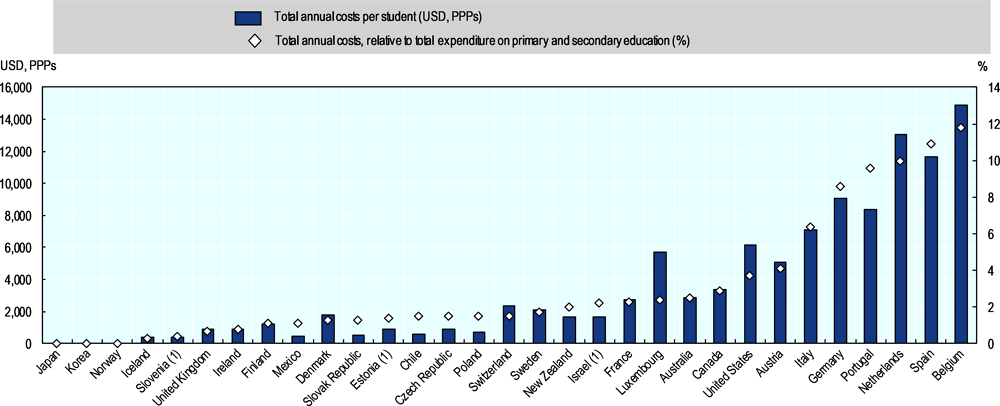

Grade repetition, which adds an additional year of schooling, is a costly practice. The retention of students in the system increases the number of enrolled students and thus the level of funding required, besides delaying students’ entry to the labour market (Manacorda, 2012[77]; Alet, Bonnal and Favard, 2013[78]; Benhenda and Grenet, 2015[79]). In an OECD estimate, the total cost of year repetition was equivalent to 10% or more of the annual national expenditure on primary and secondary school education for some countries. The cost per 15-year-old student can be as high as USD 11 000 or more (Figure 4.7) (OECD, 2011[80]).

… and tends to affect disadvantaged students disproportionally

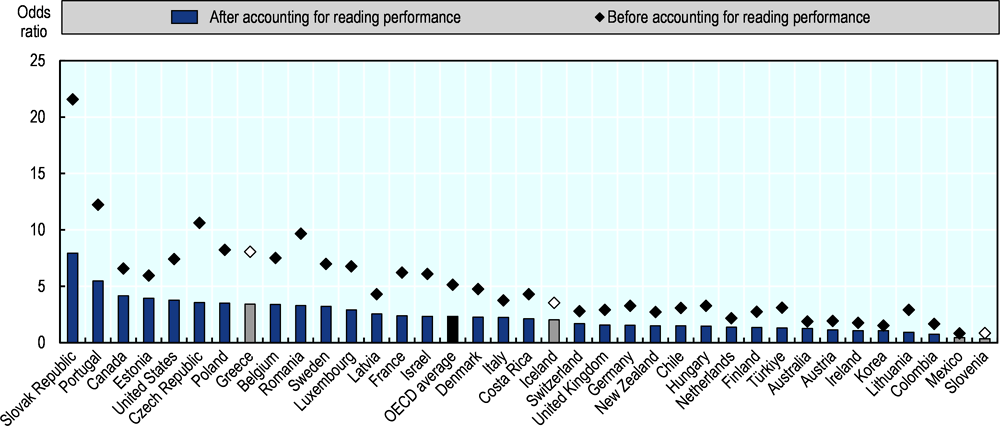

Furthermore, grade repetition raises important equity concerns as socio-economically disadvantaged students are more likely to be held back compared to their more advantaged peers. On average across OECD countries, a disadvantaged student is more than twice as likely to have repeated a grade at least once, as compared to an advantaged student, even if both students scored similarly in the PISA reading test (Figure 4.8). Across OECD countries, one in five students in socio-economically disadvantaged schools has repeated a grade at least once since entering primary school, compared to only 5% of students in advantaged schools (OECD, 2020[70]). Similarly, boys are more likely to repeat a grade than girls, and immigrant students compared to native-born students (OECD, 2018[63]).

A number of countries have taken steps to change grade repetition practices through individualised support for struggling students…

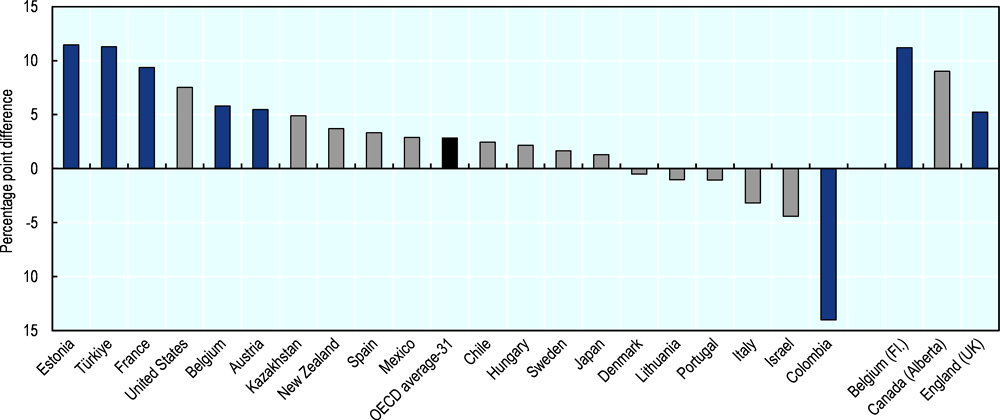

Over the past years, a number of OECD countries have taken steps to reduce their reliance on grade repetition practices. According to data from PISA, the incidence of grade repetition decreased between 2003 and 2018 in 14 out of 36 countries and other participants for which there is comparable data. On average across OECD countries, the percentage of students who reported that they had repeated a grade at least once decreased by three percentage points during the period. Notably, grade repetition decreased by more than 10 percentage points in France, Mexico, the Netherlands and Türkiye, although it increased in Austria, the Czech Republic, Iceland, Korea, New Zealand and the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2020[70]).

Reducing grade repetition begins by providing intensive, individualised support to students who struggle to keep up: learning gaps between students should be targeted early with necessary support provided for students with difficulties so that they can get back on track before they fall further behind (Box 4.7).

In Austria, different measures seek to provide early support to students with learning difficulties. In primary school, the curriculum allows for one lesson of remedial teaching (Förderunterricht) per week for students at risk of falling behind, in particular in the core subjects. This additional instruction can be delivered as an additional class or be integrated in the regular schedule. Further, students in upper secondary education with learning difficulties can receive individual learning support (Individuelle Lernbegleitung). This type of support does not focus on individual subjects, but covers the entire learning process. As part of the scheme, students work together with a tutor (Lernbegleiter*in) with a focus on individual learning goals. An early warning system (Frühwarnsystem) should help identify students with learning difficulties at risk of falling behind and inform early support measures.

In the Finnish education system, almost all students automatically pass to the next year (none are retained prior to grade 10); every child has the right to individualised support provided by trained professionals as part of their regular schooling. A teacher who is specifically trained to work with struggling students is assigned to each school and works closely with teachers to identify students who need extra help.

In Uruguay, the Community Teachers Programme (Programa Maestros Comunitarios) allocates between one and two community teachers to disadvantaged schools, depending on school size. This programme aims to prevent students from falling behind and having to repeat a year by supporting children who perform poorly. This is coupled with the Teacher + Teacher (Maestro más Maestro) Programme providing either after-school or team-teaching support for students in underserved communities.

Source: OECD (2018[63]), Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306707-en; Eurydice (2021[81]), Support Measures for Learners in Early Childhood and School Education: Austria, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/support-measures-learners-early-childhood-and-school-education-1_en (accessed on 31 January 2022).

Identifying the contextually specific indicators that are simultaneously highly predictive of grade repetition and easy for all stakeholders to interpret is a critical first step of early intervention (Box 4.8). This may require building data systems that can track student attendance, course marks and behaviour in an integrated fashion. Once these data systems are built, education professionals at the school level must be trained to interpret their outputs and design a standardised response protocol (OECD, 2018[63]).

A critical factor compromising early intervention is the failure to systematically identify at risk students sufficiently early. Some profiles of students at risk of repeating a year or dropping out of school are easily discernible for school staff: students who are frequently disruptive, refuse to complete work and fail examinations. There are, however, less obvious cases such as students who attempt to avoid being noticed and students who produce the minimal required work at low levels of proficiency. Designing a comprehensive system to identify all students who are at risk requires robust data systems that are regularly used by school staff.

As a first step, ensuring that each student has a unique identifier that can be tracked across schools and networks is critical to follow highly mobile students who are at significant risk. Second, combining educator expertise with empirical analysis to identify the factors that are most predictive of students failing a course, repeating a year and dropping out of school can clarify which are the key indicators to track. In some contexts, these results can run counter to accepted wisdom. For instance, in the United States, school attendance, course marks and behavioural conduct are much stronger predictors of school completion than external test scores.

Once countries have built data infrastructure systems and agreed on which indicators to track, extensive training of school staff (teachers, counsellors and school leaders) must take place to ensure that they both understand the meaning of the early warning indicators and acknowledge their validity. For school staff to see value in gathering these data, there must exist a clear intervention plan. This might include targeted small-group teaching and counselling sessions or referral to social service providers. Thus, it is essential to set out a clear protocol of the measures taken if students are flagged as in need as well as a system to track and ensure that these interventions have, in fact, occurred.

The last step to ensure that the data-tracking system successfully addresses risk cases is to periodically review the intervention impacts at the school and system levels. This involves analysing trends in early warning indicators across types of students and schools and comparing students’ outcomes on the early warning indicators before and after the interventions to track individual growth. Further, more formal evaluation studies are required to identify the causal effects of the interventions, for instance by using regression discontinuity design or matching techniques to compare treated and non-treated students with similar characteristics. These types of analyses permit review of areas in which students or schools need extra support, an assessment of the efficacy of specific interventions and an overall programme evaluation.

Source: OECD (2018[63]), Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306707-en.

… as well as forms of “conditional promotion” and efforts to change school cultures

School systems can also shift away from understanding grade repetition as a binary choice. Particularly in higher grades, students can be required to take a course from the year below in the specific subject in which they struggle, rather than repeating the entire previous year. With thoughtful student scheduling, this approach can be implemented at earlier year levels as well. This form of “conditional promotion” can satisfy many educators’ practice-based preferences for student-level accountability and support, while avoiding system-level concerns about its associated harms (OECD, 2018[63]).

Finally, cultural shifts in the education profession and school-level incentives to avoid repetition are critical. In many countries, educators and the public see grade repetition as a valuable tool to maintain high standards. To change the narrative around grade repetition, the awareness among educators about the dangers of grade repetition must be raised, for instance through professional development and initial and ongoing teacher education. Furthermore, system leaders must take a strong public stance against the widespread practice of grade repetition and publicly present data on its effects. Such strong initiative from the top will be crucial to shift long-standing grade repetition practices over time. France and the French Community of Belgium provide examples for serious policy attention to the issue of grade repetition (Box 4.9).

France

In 2008, the Ministry of Education set ambitious objectives to reduce repetition rates. School leaders were required to explain their school level results and encouraged to decrease the number of repeaters. Students struggling in the last two years of primary school were provided with two additional hours of academic support. The rate of primary school repetition was still 14% in 2009, so the ministry set a goal of halving this rate by 2013. In 2014, Parliament passed a decree addressing school repetition [Decree 2014-1377 of 18 November relating to the monitoring and educational support of pupils]. The decree indicates that the repeating of a year should be considered “exceptional.” It also highlights the value of dialogue between the student and the school staff prior to the decision on a student’s repetition (Benhenda and Grenet, 2015[79]). While the rate of repetition has dropped significantly, it remains high, calling for further policy efforts. In 2018, the incidence of grade repetition still ranked 11th highest in the OECD, and 17% of students were retained at least once in primary school.

As the French case study shows, budget savings from grade repetition abolition appear gradually. In fact, suspending this practice can induce short-term costs related to the more rapid flow of students towards higher and more costly education levels. However, savings could occur in the medium term (after two years in the French case) and increase gradually over time. This has important implications in terms of policy: “First, the savings to be made by abolishing year repetition can only be realised and used for other education purposes gradually. Second, the reform would require several years of careful and rigorous management of the recruitment and allocation of teaching staff over the whole transition period.” (Benhenda and Grenet, 2015, p. 4[79]).

French Community of Belgium

In the French Community of Belgium, grade repetition and early school leaving have been long-standing issues, resulting in significant costs for individuals and society. Some rather optimistic estimates put the cost of grade repetition at EUR 42.8 million in primary education and EUR 349.2 million in secondary education (2014 values). This is equivalent to 10% of the budget devoted to these levels of education. A number of policies and initiatives have therefore been put in place over time to change the culture of grade repetition, in particular in primary but also in secondary education. A major reform (Pacte pour un Enseignement d'excellence) adopted in 2015, which seeks to improve the quality of education, also aims to smooth educational pathways and to reduce educational failure and repetition.

Following legislative changes in 2015 and 2016, children can only be retained in pre-primary school (maternelle) under exceptional circumstances. Upon parents’ request and subject to the approval of the school provider, a child can repeat the third year, but is excluded in the calculation of the operating grant in that case. As part of teachers’ continuing education, third grade teachers in pre-primary can also participate in training to better understand specific learning disabilities and to adjust their pedagogy accordingly. In general, schools – In collaboration with their psycho-medical-social support centre – must put in place individualised support and remedial measures where learning difficulties are identified and define strategies to combat school failure, early dropout and grade repetition as part of their six-year school development plans (plan de pilotage). In the first stage of secondary education, an individual learning plan (Plan Individuel d’Apprentissage) which sets personal objectives and provides multidisciplinary support to students must be put in place for students where teachers and counsellors report particular learning difficulties.

These measures build on previous initiatives, such as the Décolâge! project which created a community of schools with a common interest in implementing new pedagogical practices to reduce grade repetition in the transition between pre-primary and primary education as well as a reform of the first stage of secondary education (ISCED 2) seeking to strengthen the common core for all students up to the age of 14.

Source: OECD (2018[63]), Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success, OECD Publishing, Paris; https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306707-en. Benhenda and Grenet (2015[79]), How much does grade repetition in French Primary and Secondary Schools Cost?, Institut des Politiques Publiques, Paris; Ministère de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (2016[82]), Examen de l’OCDE des politiques pour un usage plus efficace des ressources scolaires RAPPORT PAYS Communauté française de Belgique, Ministère de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Bruxelles, http://www.oecd.org/education/school-resources-review/reports-for-participating-countries-country-background-reports.htm (accessed on 01 February 2022).

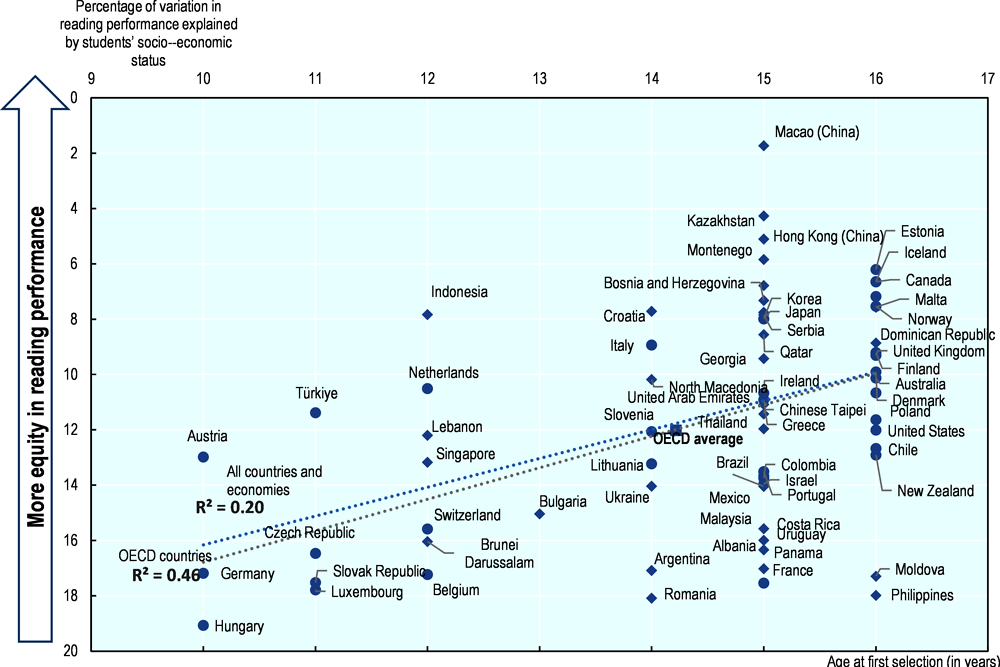

Early tracking of students into specific programmes may also limit educational efficiency and equity