2. Thailand’s development trajectory: Past and future strategies

The chapter provides an historical background of Thailand’s development path and related strategies over the past decades. It makes special reference to the role of foreign direct investment (FDI), the integration in the global trading system and rising social and environmental pressures. The chapter describes Thailand’s ambitious strategy for the future and how investment promotion and related policies are contributing to its implementation. The chapter also describes how the emerging global economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic could affect Thailand’s development trajectory and what support measures the government has introduced.

Thailand experienced rapid growth, at an annual rate of around 8%, before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. It recovered quickly from that crisis but economic expansion has remained more modest ever since. Despite slower growth in recent decades, per capita incomes have continued increasing due to fast demographic transition. Thailand joined the group of upper middle-income countries in the early 2010s.

Economic development has led by rapid urbanisation, coupled with the emergence of industrial hubs. Thailand’s development model involved a long-term structural shift from agriculture to industry, enabled first by an import substitution policy and later by greater emphasis on export promotion and an investor-friendly industrial policy. Nonetheless, one-third of the population is still involved in agriculture and it remains important to ensure that an agrarian population, already the lowest income sector in the country, does not get left further behind. Their function remains important for the Thai economy, for example in respect of food security.

The emerging global economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to bring this long period of growth to a sudden halt. The economy is predicted to contract by approximately 7% in 2020, with exports and FDI expected to slow even more. The government has introduced firm measures to address economic challenges for individuals, businesses and the economy more broadly, which total approximately 15% of GDP, among the highest in Asia.

Economic development has also brought some social progress to Thailand. Poverty rates, measured against the national poverty line, have decreased considerably from around 60% in 1990 to 7% today. Although access to basic education at primary and secondary levels is universal, there is a need to address the quality of education being provided. In particular, higher and vocational education needs to equip the workforce with skills required by industry and the emerging needs of the services economy. Social pressures remain significant particularly in poorer regions, where precarious employment conditions are omnipresent, despite some improvements over the past decades. The COVID-19 outbreak is putting new stress on income and wealth inequalities in Thailand. Both the 1997 and 2008 crises have led to increased unemployment and income inequalities and are likely to spike once more.

Rapid economic growth in Thailand has also led to significant use of natural resources, resulting in rising environmental challenges. Thailand suffers from frequent and severe floods and droughts, causing loss of life and significant economic disruption. Air and water pollution remain severe problems, particularly in industrial zones. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have increased rapidly but remain below the OECD country average.

Thailand aspires to graduate from an upper middle-income to high-income country by 2037, along with improved security and inclusive and sustainable development, as outlined in the 20-year national strategy (2018-37). With its recently introduced Thailand 4.0 vision, the government would like to achieve its 20-year strategy through economic upgrading toward a value-based, innovation driven economy away from the production of commodities and low value added manufacturing.

Thailand’s vision will not be achievable without progress towards environmental sustainability and socially inclusive growth benefiting all parts of society and regions, consistent with Thailand’s long-standing ‘Sufficiency Economy Philosophy’ prioritising economic self-reliance for all. Thailand therefore introduced the Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) economy model in 2019, involving a strategy and reform agenda on how to achieve the Thailand 4.0 vision and long-term objectives related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Investment promotion and facilitation efforts, led by the Board of Investment (BOI) and coordinated with other public and private agencies, play an essential role in these ambitions. The current investment promotion scheme aims to promote innovation and productivity-enhancement, improve human capital and develop targeted areas, particularly the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). While the COVID-19 crisis could slow the speed of progress towards Thailand’s ambitions, the focus on an inclusive and sustainable development pathway needs to be upheld during the crisis as well as its recovery.

Thailand’s orientation to a liberal market economy was established during the Cold War when the US provided extensive military support to Thailand to reduce the spread of communism in the region (Baker and Phongpaichit, 2014). After the departure of the US military from Southeast Asia in the 1970s, there was an initial period of economic and political adjustment in Thailand, although Thailand soon benefited from the Asia-wide economic boom led by Japan and the East Asian ‘Tiger’ economies (Hong Kong China, Singapore, South Korea and Chinese Taipei).

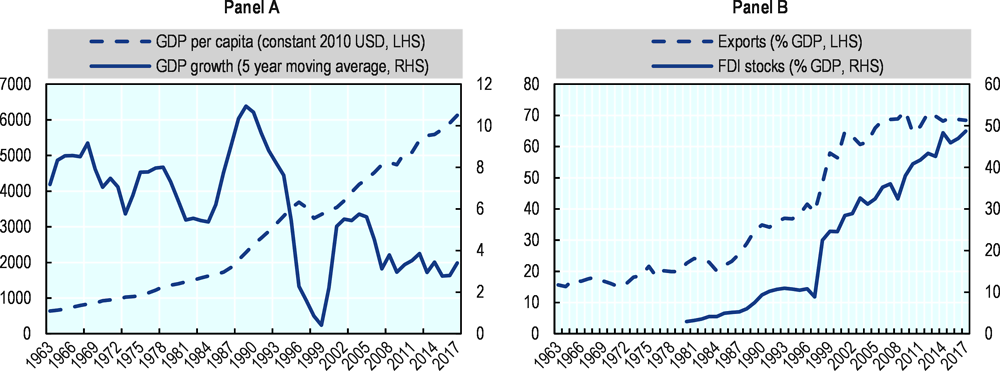

The pace of economic transformation accelerated over the last quarter of the 20th century. Thailand was one of the world’s fastest growing economies before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 (Figure 2.1, Panel A). Very high real growth rates at around 8% were maintained without a single year of negative economic growth despite occasionally high world interest rates, oil shocks, and cyclical declines in demand for Thai exports. By 1997, the economy was more than 10 times as large as in 1960.

Thailand recovered quickly from the 1997 crisis, although growth has not reached pre-crisis levels. In the early 2000s, annual growth was around 5% and has since slowed to rates closer to 3%. Despite slower growth over the past two decades, per capita incomes have continued growing steadily due to a rapid demographic transition as a result of birth control campaigns, rising prosperity and delayed childbearing for education and careers (Figure 2.1, Panel A), enabling Thailand to join the group of upper middle-income countries in the early 2010s. Recent economic development of Thailand has occurred in parallel with recurring political change and uncertainty.

Since the mid-1970s, the economy and society has shifted from rural to urban and from parochial to open and globalised. Bangkok dominated the urbanisation process, growing to over 10 million by the 2000s. With urbanisation, industrial hubs have developed in and around urban centres. The Thai economy has transformed away from agriculture and into industry since the 1980s. While the contribution of agriculture to GDP was three times that of manufacturing in 1960, it was less than one third as important as manufacturing in 2017. Nonetheless, one-third of the population is still involved in agriculture and it remains important to ensure that an agrarian population, already the lowest income sector in the country, does not fall further behind. Their function remains important for the Thai economy, not least for food security. With industrialisation, Thailand has become a major exporter of manufactured goods, rising from only one third of total exports of goods in 1980 to over 80% today. The share of exports in GDP has grown from 20% in the 1980s to almost 70% today (Figure 2.1, Panel B).

Thailand would need to further develop its services sector to advance development. Services have been responsible for approximately 55% of GDP since the early 1990s, with a somewhat lower share in the early 2000s. This share corresponds to those seen in other upper middle-income countries, but is considerably below services shares in more developed countries. Thailand does have a comparative advantage in services related to tourism, including health-related tourism which generates relatively higher value added, but Thailand could further develop its ICT, financial and other business services as well as transport (Chapter 3). These services are all important inputs into advanced manufacturing production and enable growth in advanced and modern economies.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has played a key role in the industrialisation process. FDI in Thailand was dominated in the early period by US firms (OECD, 1999), but over the 1980s, Japanese investment exceeded that from the United States by approximately three times. Some investment involved Japanese companies in tariff-jumping projects to assemble automobiles and household goods from imported components for domestic sale, but foreign investment in the automobile, electronics as well as textile sectors also enabled rising exports in those sectors. FDI’s share in GDP increased to 50% by 2017 (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Investment was still dominated by Japanese manufacturing investors, but with rising shares of other investors from both within the ASEAN region, mostly Singapore, as well as outside, for example China and Europe.

The emerging global economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic could slow progress towards Thailand’s ambition to become a high-income, innovation-driven country by 2037. The government predicts the economy will contract by 5.3% in 2020 (Bank of Thailand, 2020), in line with estimates by the World Bank (3-6.8%) and the International Monetary Fund (6.7%) (Maliszewska et al., 2020; and IMF, 2020). All estimates find Thailand’s economy to be the most affected in Southeast Asia.

Thailand relies extensively on trade and investment in global value chains (GVCs), which have come to a sudden halt in many sectors earlier in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. Thai exports may fall by as much as USD 22 billion in 2020, with the biggest impacts on exports of manufacturing goods and (travel) services and very little impact on agricultural goods or natural resources (Maliszewska et al., 2020). Likewise, FDI is set to fall in 2020 by more than 30% globally and is likely to affect developing countries, including Thailand, relatively more given their exposure to crisis-affected manufacturing sectors (OECD, 2020a). Cross-border M&A deals and announced greenfield FDI in Thailand dropped considerably in the first months of 2020 compared to the previous years (Chapter 4). With much of the world having entered full or partial lockdown in March, the downward trend is likely to have been magnified since.

Some experts have suggested that complex GVCs might be less robust in the crisis, possibly due to additional risks and costs related to international trade.1 This outcome is unlikely in Thailand. There is no relationship between the level of fragmentation of Thai production (complexity of sectoral GVCs) and the severity of the economic impact of COVID-19; not only because of services activities but also among manufacturing industries. Additionally, Thailand’s past experience of severe floods in 2011, which also resulted in a sudden supply shock, may provide some hope that Thailand’s GVC integration is quite resilient – even if not always robust. Key producers relaunched and expanded operations in Thailand soon after the floods in 2011 (Miroudot, 2020).

Economic development over the past decades has also brought social progress. Measured against the national poverty line, poverty has considerably dropped from levels of around 60% in 1990 to 7% today. Thailand provides almost universal access to basic education at the primary and secondary levels, but despite relatively high levels of public expenditures on education (4% of GDP), the quality of basic education can be significantly improved relate to global benchmarks. Higher and vocational education needs to equip the workforce with skills required by the industry and the emerging needs of the services economy (Chapter 3).

Social pressures remain significant, particularly in poorer regions. While the number of workers in precarious employment conditions fell from around 70% in the 1970s to 50% in the mid-2000s, improvements have stagnated since then, reflecting a high share of low-income agricultural workers and significant urban informality. Today, only one in ten Thai citizens say that they can live comfortably with their current income (OECD, 2018). Bangkok has been the driver of Thailand’s economic transition, and is therefore more developed than the Northeast, North, and South regions.

As the labour market tightened in the early 1990s, the borders were implicitly opened to admit labour migrants from neighbouring countries, mostly Myanmar. Today, almost 10% of the labour force or 3.5 million are low-skilled migrant workers employed predominantly in agriculture, fishing, construction, domestic services, manufacturing and retail. Many of those migrant workers, but also many low-skilled Thai workers, have informal work arrangements and are paid below the minimum wage without unemployment protection. The latter is reserved to employees in the formal sector. More recently, basic social protection has improved in some areas: the 2002 universal health coverage scheme and the 2009 universal allowance for elderly provide access to services for all, including those in the informal sector.

Significant informality among migrant workers also results in persistent problems in other areas of responsible business conduct (RBC), including with respect to human trafficking and forced labour, especially in the commercial sex industry and domestic work sector but also in the fishing industry. The government’s efforts have been strengthened more recently with enhanced inspection frameworks, improved laws and increased penalties in case of abuse (HRW, 2018). Thailand is the first Asian country with a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, whose implementation is supported by the OECD and ILO (Chapter 9).

The COVID-19 outbreak is putting new pressure on income and wealth inequalities in Thailand. Both the 1997 and 2008 crises led to increased unemployment and income inequalities and these are likely to spike once more. Significant job losses are already being reported by the Department of Employment (Asadullah and Bhula-or, 2020). People with informal and precarious employment conditions, including those with small family businesses, are most affected. The government has introduced important measures to address economic challenges facing households (see Box 2.1).

As in many emerging economies, rapid economic growth in Thailand has come with a significant use of natural resources, resulting in rising environmental challenges (Chapter 10). The natural environment is the foundation of key economic sectors and millions of livelihoods in Thailand. Careful use and protection of environmental resources are therefore crucial and have become a priority in Thai policies since the 1990s (OECD, 2018). Thailand is exposed to frequent and severe floods and droughts that have caused loss of life and significantly disrupted the economy. While some of these outcomes are due to Thailand’s general climatic exposure, urban expansion, intensive agriculture and the deterioration of watershed forests have made Thailand more vulnerable to flooding. Moreover, high water consumption, agricultural and industrial land development and urbanisation have contributed to droughts.

Air pollution has been worsening since 2010 after some improvements during the previous two decades. The problem is particularly severe in industrial zones, where air pollution is often above safe limits. Similarly, one-quarter of surface water is assessed as poor quality, with some reported improvements over recent years. Progress is held back by a shortfall in wastewater treatment facilities, poor compliance with existing regulation and an absence of financial disincentives to pollute. Moreover, the quantity of solid waste is increasing rapidly, almost half of total solid waste is disposed of through open burning or illegal dumping, putting additional pressure on environmental assets (OECD, 2018).

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have increased rapidly with economic growth. Over 1990-2015, absolute carbon emissions increased from 80 million to 244 million tonnes per year, more than doubling in per capita terms – although still well below the OECD country average. Thailand has ambitious plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – up to 20-25% by 2030 under current projections (ONEP, 2015). The energy and transport sectors are identified as the key sectors for mitigation efforts. In order to achieve targets, some features under current energy plans may need to be adjusted. For example, it is currently planned to increase the share of coal in the energy mix which could challenge carbon emission reduction efforts (MOE, 2016). The planned transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy is now being challenged by the unprecedented health emergency and economic crisis trigged by the global COVID-19 outbreak. The collapse in oil and gas prices and decline in coal prices may reduce support for renewable energy.

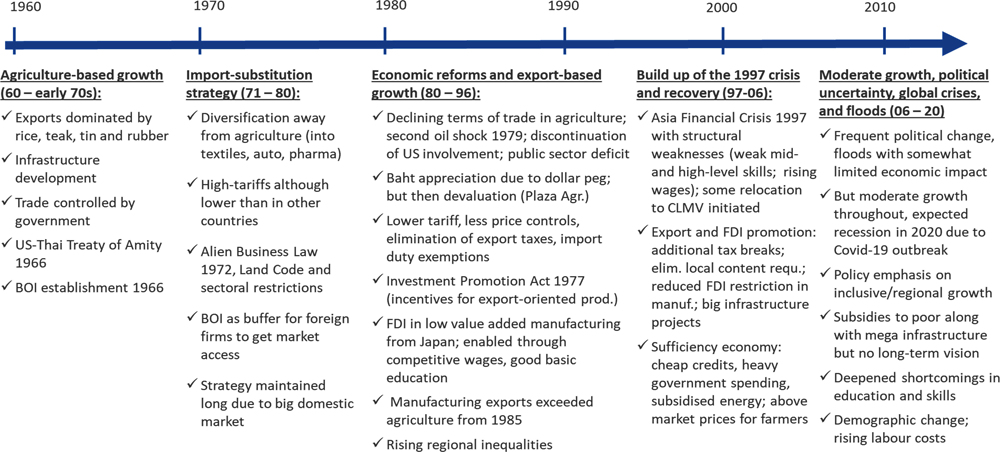

Embedded in 5-year development plans since the early 1960s, Thailand’s macroeconomic policy has been relatively stable over the past decades despite frequent changes in government (Figure 2.2). Thailand followed a development model like many in Asia and elsewhere, involving a long-term structural shift from agriculture to industry. The shift from an import substitution policy to greater emphasis on export promotion was essential for the rapid growth of manufacturing production and exports. Nonetheless, the export boom came slightly later with more favourable exchange rate policies and an investor-friendly industrial policy. More recent development policies have emphasised inclusive and sustainable growth, but challenges remain particularly in light of the emerging global crisis due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Agriculture-based growth (1960 – early 1970s)

As many developing countries, Thailand traditionally produced and exported primary and agricultural products. The industrialisation process, mostly of textiles and garments, started during the 1960s, but high growth rates at around 8% were importantly driven by exports of agricultural products. Rice, teak, tin and rubber were responsible for more than 80% of total exports in the 1960s (OECD, 1999).

The government focused on developing economic infrastructure, including roads, dams and water reservoirs, and on diversifying agricultural production. International trade was controlled by the government: for example, rice exports were controlled by a state monopoly and discouraged by significant export taxes. During this period, the government initiated support for the industrialisation process with the establishment of the Board of Investment (BOI) in 1966. Attempts at more inclusive and broad-based development were made by decentralisation of education, but the gap in the quality of education between urban and rural areas remained significant. The 1960s was a period during which Thailand had a strong alliance with the United States, both economically and through military support and funding. The US-Thai Treaty Amity was signed in 1966 and exempted US investors from many of the restrictions foreign MNEs from other countries were soon facing and to some extent are still facing today.

Import-substitution strategy (1971 – 80)

In the early 1970s, the government strengthened its industrialisation efforts and adopted an import-substitution strategy, common in many developing countries at the time. The objective was to limit the dependence on imported goods, save foreign exchange, increase domestic value added and diversify away from agriculture. The industrial policy prioritised large-scale producers in capital-intensive industries, mainly textiles, automobiles and pharmaceuticals. Import tariffs remained modest compared to other countries (30-55% for consumer goods), but still included very high tariffs above 90% on some categories, including on automobiles. Import-substitution started on consumer goods but then also moved to capital and intermediate goods.

Foreign investment was regulated by the Announcement of the Revolutionary Council 1972 (ARC. 281), the Land Code and other sectoral restrictions. Foreign participation was restricted across agricultural, industrial and services sectors (Chapter 6). The Alien Business Law (ABL) served to protect industries where Thailand already had domestic capabilities, while providing market access to foreign firms in sectors where foreign capital was needed for their development, e.g. textiles and automobiles. The BOI served as a buffer, that is, foreign firms would get access to the Thai market in some sectors if they were promoted by the BOI after initial screening. American firms were mostly excluded from restrictions due to the Treaty of Amity, except for certain specific sectors.

Although import substitution was questioned by leading banks and businesses with some support of technocrats in the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB)2 early in the 1970s, little was done to move away from import substitution towards export promotion. The Ministry of Finance, the military and protected firms built a strong lobby against a policy shift. The strategy could be maintained for a relatively long time in Thailand given the extensive domestic market which delayed market saturation, rising world agricultural prices, and extensive inflows of foreign capital that softened the first oil shock and eased the balance of payments position.

Economic reforms and export-based growth (1980 – 96)

Towards the end of the 1970s a number of problems arose and meant that the import-substitution strategy could no longer be maintained. Declining terms of trade for agricultural products harmed the expansion of agricultural exports and increased pressure on the balance of payments. Furthermore, the second oil shock of 1979 and the discontinuation of US military aid put pressure on public sector finance and led to a rising public sector deficit. Thailand chose to continue pegging its currency to the US dollar after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system which proved costly for Thailand when the US dollar appreciated against other major currencies between 1978 and 1985. This resulted in rising interest rates, a sharp growth slowdown and consecutively a number of baht devaluations in the 1980s. This included the baht devaluation as a result of the Plaza Agreement 1985 which led to baht depreciation relative to the yen and deutsche mark due to its peg to the US dollar.

Along with the devaluations, the government moved towards an export promotion strategy. Protection was reduced by lowering tariffs, relaxing price controls and eliminating export taxes. Exports were further promoted by import duty exemptions on machinery and raw materials used for the production of exported goods. With 1977 Investment Promotion Act, BOI investment incentives were changed in order to favour export-oriented projects and the Bank of Thailand introduced special credit facilities for exporters. In general, macroeconomic policies became market-oriented with flexible exchange rates and few constraints on interest rates.

These depreciations and newly introduced export promotion policies made Thailand an attractive destination for export-oriented FDI after 1985. This was particularly the case for Japanese investments and those from some Newly Industrialised Economies, such as Chinese Taipei and Singapore, whose comparative advantage in low value added manufacturing disappeared in home markets. The government’s early efforts to provide broad-based basic education also paid off during this period. Thailand was particularly attractive for Japanese investors due to the large pool of workers with basic education and skills and competitive labour costs. Nonetheless, two thirds of workers were still employed in agriculture in the early 1990s.

With these policy changes, manufacturing exports started to expand rapidly, with light manufacturing such as garments and leather products increasing its share. Manufacturing exports exceeded agricultural exports from 1985, although agricultural production and exports remained important. Over time, labour-intensive industries such as electronics assembly, footwear, as well as higher technology goods such as computer accessories and motor parts also gained importance in exports. The growth and export boom did not benefit different parts of the country evenly, however, as industrialisation was concentrated in Bangkok and neighbouring provinces

The build up to the 1997 crisis and recovery (1997 – 2006)

The Thai economy was seriously affected by the 1996 export slowdown, resulting from sluggish world demand for electronic and other goods. The slowdown was particularly strong in Thailand due to structural weaknesses. The economic boom did not produce an increasingly skilled workforce that could compete with workers from countries like Chinese Taipei or South Korea. Investment in educational infrastructure was not sufficient to prepare workers for higher value added activities. In 1997, for example, only 17% of Thais finished high school and Thailand had only 260 engineers per 1 million compared to 2500 per million in South Korea (Hays, 2014). Rising wages in Thailand were not matched with increases in productivity and Thailand had difficulty moving towards skill-intensive activities that would correspond to relatively higher wage levels. This caused many firms, both Thai and subsidiaries of foreign firms, to relocate to lower cost locations in neighbouring countries.

A number of other factors resulted in the currency crisis which started in 1997. The credit boom in the early 1990s gave rise to a financial and real estate bubble that made the economy vulnerable to a shift in business sentiment. The shift materialised as a result of the export slowdown and the attempt of the authorities to defend the exchange rate through very high interest rates. Foreign exchange reserves dwindled, which led to a collapse of the baht in mid-1997 together with substantial capital flight, causing a deep recession. Similar events subsequently happened in other emerging Asian economies, becoming known as the Asian Financial Crisis.

The economy recovered in the early 2000s as a result of a number of structural reforms and an accelerating global economy. The policy approach included two main strategies. On the one hand, the government promoted exports and FDI, with additional tax breaks to attract foreign investors, elimination of local content requirements and allowing full foreign participation in most manufacturing sectors, and the funding of key infrastructure projects such as Bangkok’s new airport (Nikomborirak, 2004). As Thailand’s comparative advantage in low cost, low value added manufacturing was fading with the rise of China, the objective was to focus on areas where Thailand had a comparative advantage, including in trade, food and tourism. On the other hand, economic self-reliance and increased consumption at home were fostered, including in less developed rural regions (‘philosophy of sufficiency economy’). The government stimulated the economy with cheap credit, heavy government spending and subsidised energy, although fuel subsides were phased out after 2005. Taxes were reduced to induce more spending, and farmers were given above market prices for their crops. At the same time, and in order to prevent another crisis, more restrictions on foreign investors were imposed in some sectors, real estate developers were prevented from borrowing money from banks to buy land, and new laws controlled an overheating of stock markets. A national asset management company was established which took over bad loans from banks (Hays, 2014).

Moderate growth with political uncertainty and economic crises (2006 – 20)

Thailand has seen frequent political changes in recent years but with only limited apparent impact on the economy which has continued growing throughout the past two decades, albeit at lower levels than before the 1997 crisis, with growth sustained even during the global economic crisis 2008-09 and the massive flooding in 2011. The emerging global economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to bring this long period of growth to a sudden halt. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the economy is predicted to contract by approximately 7% in 2020, where exports and FDI are expected to slow yet more (OECD, 2020d). The policy approach deepened its emphasis on inclusive and regional growth independent of the government in place. The policy tools used to support the poor also remained similar to previous periods, including cash hand-outs and rice subsidies until recently. In the early 2010s, significant spending in terms of subsidies to the poor along with mega infrastructure projects in transport, ports, energy and telecommunications increased public debt. Shortcomings in education and skills at all levels have not been resolved. Thailand needs to urgently address this issue, or it will be difficult to make significant progress in breaking out of the so-called ‘middle-income trap’ which challenges many middle-income developing countries.

Responding to the ongoing crisis, the government has introduced firm measures to address economic challenges for individuals, businesses and the economy more broadly, which total approximately 15% of GDP, among the highest in Asia (Ariyapruchya et al., 2020). These packages include soft loans and relaxed loan repayments, reduced social security contributions, and tax deductions for SMEs linked to employment retention. Other significant measures include a cash transfer of THB 5 000 per month for six months for informal workers not covered by the Social Security Fund as well as corporate income tax exemptions for five to eight years with a 50% corporate tax deduction for the following five years for companies that invest at least THB 500 million on approved large-scale projects in 2020 (Box 2.1).

Third stimulus package of THB 1.9 trillion (USD 58.5 billion) aiming to help people and business as well as providing financial aid to farmers.

Second stimulus package of THB 117 billion (USD 3.6 billion), including living subsidy of THB 5000 for six months, additional emergency loan, delay in income tax declaration, tax deduction on health insurance, tax exemption for medical personnel, soft loan of THB 3 million (USD 31 000), grace period for tax payment, THB 10 billion (USD 303 million) in soft loan to tourism sector.

First stimulus package of THB 100 billion (USD 3.03 billion), including financial aid to SMEs, tax benefits, cash handout, soft loans to support low-income, farmers and SMEs.

Reduction of policy rate from 1.25% to 1.00% in February, to 0.75% in March and to 0.5% in May.

Measures to support market liquidity and providing liquidity backstop for market-based finance, include through Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility, Corporate Bond Stablilization Fund, and Government Bonds

Measures to assist SMEs and households, including for example loan repayment measures to assist borrowers, a loan payment holiday of 6 months for all SMEs with credit line not exceeding THB 100 million, and soft loans to support liquidity for SMEs.

Board of Investment (BOI) exemption on corporate income taxes for five to eight years, with a 50% corporate tax deduction for the following five years for companies that invest at least 500 million baht on approved large-scale projects in 2020; BOI additional benefits for companies that invest in the grassroots economy.

Salary maintenance (45-50% up to THB 15 000); reduction in social security contribution from 5% to 4% and grace period for social security payment to July.

Source: Based on inputs from the Bank of Thailand in June 2020, OECD (2020b) as of 21 April 2020. OECD (2020c) provides more details on measures targeted to SMEs, as of 20 April 2020; Parpart, E. (2020) provides a more comprehensive list, as of 27 March. See Chapter 5 for further details on BOI measures related to COVID-19.

Towards a value-based and innovation-driven economy

Thailand’s economic and social development since the 1960s has been based on 5-year development plans under the NESDC. A new Constitution was promulgated in 2017. It calls on the state to develop a long-term national strategy as a goal for sustainable national development to be used as the framework for future 5-year development plans and more targeted strategies and laws, implemented by specific line ministries. A key objective of the national strategy is to ensure continuity of economic and social policies for Thailand’s future, independent of specific governments in place. The National Strategic Committee has been established in order to draft the 20-year national strategy (2018-37).3

The 20-year national strategy (2018-37) to raise Thailand from an upper middle-income to a high-income country by 2037 was approved by the National Legislative Assembly in 2018 (Sattaburuth, 2018). Its vision is to achieve prosperity, security and sustainability along Thailand’s deeply embedded ‘sufficiency economy philosophy’ – introduced in the 9th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2002-06). Specific objectives aim to ensure national security, enhance competitiveness and upgrade Thailand’s economic potential, improve human resources at all levels, enable economic opportunities and an equitable society, and foster environmental-friendly development (Vimolsiri, 2017). All government agencies must comply with the strategy and align master plans and budget allocations accordingly. Compliance is monitored by the National Strategy Committee, and the strategy will be reviewed every 5 years. The 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017-21) translates the broad vision of the 20-year strategy into more concrete goals and reforms (NESDC, 2016).

In line with the legal and institutional framework under the 20-year strategy and the most recent 5-year development plan, the government has introduced the ‘Thailand 4.0’ development concept. Thailand 4.0 is a short-cut to Thailand’s vision to become a value-based and innovation-driven economy and move away from producing commodities to promoting technology, creativity and innovation in focused industries and increasingly in services. It is Thailand’s ambition of continuous development starting from ‘Thailand 1.0,’ which focused on the agricultural sector, to light industries with ‘Thailand 2.0,’ where Thailand benefited from low labour costs, through to ‘Thailand 3.0,’ which focused on more complex industries, attracted foreign investment and made Thailand a production hub for exports.

The Thailand 4.0 plan focuses on ten target industries, which can be divided into two groups.4 The first group focuses on five existing industrial sectors with the aim to add value through advanced technologies: agriculture and biotechnology; smart electronics; affluent medical and wellness tourism; next-generation automotive; and food for the future. The second group includes five additional growth engines: biofuels and biochemical; digital economy; medical and healthcare; automation and robotics; and aviation and logistics.

Thailand’s vision will not be achievable without progress towards environmental sustainability and socially inclusive growth benefiting all parts of society and regions, consistent with Thailand’s long-standing ‘Sufficiency Economy Philosophy’ prioritising economic self-reliance for all. Thailand therefore introduced the Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) economy model in 2019. It involves a strategy and reform agenda on how to achieve the Thailand 4.0 vision and long-term objectives related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While the potentially deep global economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic could slow the speed of progress towards Thailand’s ambitions, the focus on an inclusive and sustainable development pathway needs to be upheld during the crisis as well as its recovery.

Regional efforts to boost connectivity, trade and investment are key ingredients for Thailand’s ability to implement its ambitious national development plans. The ASEAN Economic Community has been a catalyst for, and will continue to support, intra-regional investment. China’s Belt and Road Initiative aims to build new roads, railways and ports across ASEAN (OECD-UNIDO, 2019). Increasingly strong political ties with China and concrete infrastructure development plans could help Thailand become a regional logistics hub and lower related costs. Strong cooperation with China is also strengthening Thailand’s role in the implementation of the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 (ASEAN, 2016). Furthermore, the Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) – a free trade agreement between the ten ASEAN member states and the five Asia-Pacific states with which ASEAN has existing free trade agreements (Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand) – was signed in November 2020. International cooperation on trade and investment are key for a successful crisis recovery and continue to be important for sustainable development in Thailand.

Role of investment promotion and related policies

Investment promotion and facilitation policy plays an essential role in turning the ten target industries into Thailand’s growth engines of the future. The current investment promotion scheme of the Board of Investment (BOI) runs from 2015 to 2021 and aims to enhance Thailand’s competitiveness, overcome the middle-income trap and achieve sustainable growth; all in line with greater ambitions related to Thailand 4.0 and the 20-year strategy. Since 2015, the scheme has been augmented and more specifically tailored to higher level plans and strategies and the promotion of the 10 target sectors. Most recently, the BOI adjusted and expanded its services to support firms during the COVID-19 crisis (e.g. additional tax incentives) and attract investment into the health sector (Chapter 5).

Investment promotion policy focuses on four overarching objectives (described below and in detail in Chapter 5), and activities are complemented and to some extent coordinated with those of other ministries and state agencies (e.g. Ministry of Finance; Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, MHESI; Eastern Special Development Zone Policy Office; Industrial Estate Authority; Ministry of Industry; and Office of Small and Medium Enterprises Promotion).

Promoting technology development and innovation

Thailand’s investment promotion policy aims to attract investment into research and development (R&D) projects in the 10 target sectors and particularly in the area of four core technologies in which Thailand is considered to have the potential to enhance the country’s overall competitiveness, namely biotechnology, nanotechnology, advanced material technology and digital technology (Chapter 5). Projects must involve a component on technology transfer by cooperating with educational and research institutions, for example via programmes of the National Science and Technology Development Agency or the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research, under MHESI. Technology-based projects can receive a corporate income tax exemption of up to 13 years from the BOI. If considered as high-impact investments under the newly enacted Competitiveness Enhancement Act 2017, tax exemptions may be granted for up to 15 years. Beyond programmes of the BOI and MHESI, other government agencies – such as the Revenue Department – are also providing support and incentives to improve innovation capacity.

Fostering productivity-enhancement

The BOI provides tax exemptions to enhance investments into specific productivity-enhancing activities within the ten target industries and services. More generous tax exemptions are provided for higher levels of technology and value creation within the supply chain. At the same time, the foreign investment regime remains rather restrictive in a number of services, despite the fact that Thailand 4.0 focuses on developing advanced services and services also play an important role in enabling higher value chain activities in manufacturing (Chapter 6).

Thailand’s productivity ambitions can only be attained if public policies help to level the playing field for all types of firms. For example, all firms – independent of whether or not they are BOI promoted – should benefit from import duty reductions and may benefit from merit- or performance-based support (see policy directions provided in Chapter 5). It is of utmost importance to put the emphasis on SME upgrading, even if upgrading does not involve technology frontier-type of activities. BOI promoted firms may receive performance-based tax exemptions if they engage in developing and training local suppliers. SMEs themselves may receive specific information and technical support from the BOI, as well as from a number of other state agencies involved in the promotion and support of local firms and SMEs (e.g. the Ministry of Industry, or the Office of Small and Medium Enterprise Promotion).

Improving human capital

An important constraint for Thailand to become a knowledge-based and innovation-driven economy is its persistent gap in adequate skills, both vocational and higher level skills (Chapter 3). The Office of the Vocational Education Commission, along with programmes of the BOI and MHESI, have recently boosted efforts and programmes to increase both the quantity and quality of vocational skills and make technical training more attractive to Thai students. These programmes are increasingly developed and coordinated with the private sector and educational institutions. They often require students to combine practical training in companies with classroom education; an example is the Work-integrated Learning programme, introduced in 2012 by the National Science Technology and Innovation Policy Office.

With respect to higher level skills (e.g. researchers and engineers), the creation of the MHESI in 2019 and its determined reform agenda – including related to enhanced coordination and joint initiatives of government agencies, educational and research institutions, industry and the local community – is an essential step to address the skills and innovation challenge. The Thai government is also inclined to attract foreign talent to develop the ten target industries. For that purpose, the SMART visa programme has been designed to attract foreign science and technology experts, senior executives, investors and start-ups (see further discussion below and in Chapter 5). While this programme is useful to address an immediate challenge, broader alignment and reforms are required to facilitate entry of foreign workers and to produce required skills within Thailand.

Developing targeted areas with a focus on Eastern Economic Corridor

In recent years, a number of area-based schemes have been introduced to advance Thailand’s economic development towards higher value added activities and expand socio-economic development to regional and local levels.

The BOI used a cluster-based policy in 2015-17 to promote business clusters that operate within concentrated geographic areas and function through interconnected businesses and related institutions. Cluster development was supported by government agencies in wide-ranging aspects, including human resources and technological developments, infrastructure development and logistics system, tax incentives and non-tax incentives, financial support, and amendments of rules and regulations to facilitate investment. It covered a broad range of provinces across Thailand and was grouped into so-called super-clusters (e.g. in automotive, electronics, petrochemicals, digital) that were relatively more supported, as well as other clusters (e.g. textiles and garments, and agro-processing). Investment uptake was relatively low under this policy (Rattanakhamfu, 2018).

With the introduction of the Thailand 4.0 narrative, area-based policies moved away from wide ranging cluster development across Thailand towards a geographically much more concentrated strategy, namely the EEC. The EEC strategy was introduced in 2016 and the EEC Act came into force in 2018. EEC receives high-level political endorsement: The EEC Policy Committee is chaired by the Prime Minister and the EEC Office is now an independent state agency with links to the Ministry of Industry. The EEC covers three neighbouring provinces Chachoengsao, Chonburi, and Rayong which are already key industrial hubs in Thailand and considered as the centre of the east-west economic corridor, boasting connectivity with the Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Viet Nam, and South China. In contrast to objectives for broad-based and regional development across Thailand, the EEC strategy aims to promote mainly investments in targeted core technologies, high-impact and strategic investments in line with the Thailand 4.0 and BOI policy. These include important infrastructure projects such as the dual-track railway, high-speed train, extensions of ports and upgrading of the U-Tapao international airport. The EEC strategy is supplemented by numerous ministerial projects, such as the EECi Innovation hub that fosters international innovation collaboration in target sectors and is governed by MHESI.

Thailand continues to promote inclusive growth through additional area-based policies, including the Border Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Development Policy, as well as promotional efforts in border provinces in Southern Thailand and in the 20 poorest provinces in the East and North of Thailand. In this context, the development of Border SEZs has received particular attention as a potential driver of regional development and was initiated in 2015, with a first phase in five provinces (Tak, Mukdahan, Sakaeo, Trat, and Songkhla) and a second phase in five additional provinces (Nong Khai, Narathiwat, Chiang Rai, Nakhon Phanom, and Kanchanaburi). Border SEZs are governed by the National Committee on SEZ Development (NC-SEZ) which is chaired by a member of the government, coordinated by NESDC and includes members from a number of line ministries. Targeted activities in SEZs include labour-intensive, light manufacturing (e.g. furniture, garments, agro-processing, plastic products), advanced manufacturing (e.g. medical devices, automobile parts, electronics) as well as logistics and tourism services. Investment projects in targeted activities may receive tax incentives from the BOI, or other tax reductions and non-tax incentives from the Revenue and Customs Departments. Special financial facilities for investment are available; and SME investors may benefit from additional benefits (such as lower minimal investment requirements) (NESDC, 2018; TDRI, 2015).

Broad-based economic and sustainable development across all regions is also being reinforced with the newly introduced BCG economic model. These efforts need to further ensure that protecting local communities’ rights (e.g. over land acquisitions) is guaranteed and industrial practices are environmentally sustainable (Chapter 10).

References

Anuroj, B. (2018), Thailand 4.0 – a new value-based economy, Thailand Board of Investment.

Ariyapruchya, K.; Nair, A.; Yang, J. and Moroz, E. H. (2020), The Thai economy: COVID-19, poverty, and social protection.

Asadullah, M. N. and Bhula-or R. (2020), Why COVID-19 will worsen inequality in Thailand, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/why-covid-19-will-worsen-inequality-in-thailand/

ASEAN (2016), ASEAN Master Plan on Connectivity 2025, http://asean.org/storage/2016/09/MasterPlan-on-ASEAN-Connectivity-20251.pdf

Baker and Phongpaichit (2014), A History of Thailand: third edition, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Bank of Thailand (2020), Monetary Policy Report March 2020 issue, https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/MonetaryPolicy/MonetPolicyComittee/MPR/DocLib/PressMPR_March2563_vp5sp02.pdf#search/project-syndicate.org/_blank

Hays, J. (2014), Economic history of Thailand: Post-war boom and the Thaksin and post-Thaksin years, http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Thailand/sub5_8g/entry-3310.html

HRW (2018), Hidden chains: Rights abuses and forced labor in Thailand’s fishing industry, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/01/23/hidden-chains/rights-abuses-and-forced-labor-thailands-fishing-industry

Jones, C., & Pimdee, P. (2017), “Innovative ideas: Thailand 4.0 and the fourth industrial revolution”, Asian International Journal of Social Sciences, 17(1), 4 – 35, https://doi.org/10.29139/aijss.20170101

Maliszewska, M; Mattoo, A.; and van der Mensbrugghe, D. (2020), “The Potential Impact of COVID-19 on GDP and Trade: A Preliminary Assessment”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 9211.

MOE (2016), “Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint”, EPPO Journal Special Issue 2016, Energy Policy and Planning Office, Ministry of Energy, Bangkok.

NESDC (2018), Border SEZ Development Policy, NESDC.

NESDC (2016), The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan, Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, the Office of the Prime Minister, Bangkok, http://www.nesdb.go.th/nesdb_en/download/article/Social%20Press_ Eng_Q4-2559.pdf

Nikomborirak, D. (2004), An Assessment of the Investment Regime: Thailand Country Report, Submitted to: The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Thailand Development Research Institute.

OECD (2020a), FDI flows in the times of COVID-19, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/foreign-direct-investment-flows-in-the-time-of-covid-19-a2fa20c4/

OECD (2020b), Covid-19 crisis response in ASEAN Member States, Tackling Coronavirus (Covid-19), https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=129_129949-ehsuoqs87y&title=COVID-19-Crisis-Response-in-ASEAN-Member-States

OECD (2020c), SME Policy Responses, Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119680-di6h3qgi4x&title=Covid-19_SME_Policy_Responses

OECD (2020d), OECD Economic Surveys: Thailand 2020: Economic Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ad2e50fa-en.

OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293311-en

OECD (1999), Foreign Direct Investment and Recovery in Southeast Asia, OECD Proceedings, http://www.oecd.org/investment/investmentfordevelopment/40818364.pdf

OECD-UNIDO (2019), Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in Global Value Chains: Engabling linkages with foreign investors, https://www.oecd.org/investment/Integrating-Southeast-Asian-SMEs-in-global-value-chains.pdf

ONEP (2015), Thailand’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Bangkok, https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/Pages/Home.aspx

Parpart, E. (2020), A comprehensive list of government economic support measures for individuals, businesses and the economy, https://www.thaienquirer.com/10125/a-comprehensive-list-of-government-economic-support-measures-for-individuals-businesses-and-the-economy/

Rattanakhamfu, S. (2018), EEC and Thailand 4.0, Presentation of September 7, 2018, TDRI.

Sattaburuth, A. (2018), NLA approves 20-year national strategy, Bangkok Post, 6 July 2018.

TDRI (2015), New BOI policy & special economic development zones, Presentation of 14 May, 2015, TDRI.

Vimolsiri, P. (2017), Thailand 20 Year Strategic Plan and Reform, National Economic and Social Development Council.

Notes

← 1. https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm

← 2. The NESDB has been renamed to National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) in 2018.

← 3. The Committee includes the prime minister; speakers of the House and the Senate; a deputy prime minister or minister; the Defence permanent secretary; chiefs of the armed forces; the secretary general of the National Security Council; the chairman of the NESDC; heads of the Board of Trade, Federation of Thai Industries, Tourism Council of Thailand and Thai Bankers Association.

← 4. The target industries are often called S-curve sectors, reflecting the speed of adoption of an innovation, where innovation leads to increasing growth at the beginning, then growth turns to maturity and declines subsequently (Jones and Pimdee, 2017).