Chapter 3. Inclusive regional and rural development policies and governance

This chapter discusses the design and implementation of inclusive regional and rural development policies and governance for the Sami. It outlines the need to improve whole-of-government prioritisation and co ordination for Sami relations and engagement and the importance of developing more effective frameworks to manage land use issues (e.g. developing guidelines and cultural awareness to engage with Sami, and improving information about Sami land use for regulators).

Better linking the Sami with regional and rural development efforts fundamentally comes down to questions of governance – that is, how the Sami, their economy and their ambitions for development are visible and included in regional and rural development policies within a framework for multi-level governance relations. Improving these linkages requires navigating a complex institutional environment involving multiple actors; improving the understanding of the Sami economy and its potential; and creating a stronger platform for their own development ambitions to be heard, realised and connected to regional development policies and programmes.

Chapter 1 of this report has focused policy recommendations on the need for improved quality of data and information about the Sami economy to inform decision-making (this includes establishing better systems to collect data, investing in competencies, and clarifying responsibilities for data collection). Chapter 2 outlined the frameworks for regional and rural development in Sweden and discussed the need to consolidate and strengthen responsibilities for Sami economic development and to address issues that result in programme mismatches (e.g. incorporating specific Sami objectives and criteria, and reducing barriers to entry for micro-enterprises). Building on these two previous chapters, this chapter on governance focuses on two issues. First, the need to improve whole-of-government prioritisation and co-ordination for Sami relations and engagement. Second, the need to develop more effective frameworks to manage land use issues (e.g. developing guidelines and cultural awareness to engage with Sami, and improving information about Sami land use for regulators).

Better linking the Sami with regional and rural development efforts

A diversity of Sami voices and institutions – Implications for engagement

Better linking the Sami with regional and rural development efforts in northern Sweden requires an acknowledgement of the assets and opportunities of the Sami alongside recognition of their own development ambitions and business needs and how these fit – or not – within regional and rural development strategies and programmes. However, doing so is complicated by the fact that the Sami have a lack of visibility; there is often a low cultural awareness of the group within Swedish society (with some differences between the north and south of Sweden). Moreover, Sami society is very diverse. The Sami do not speak with one voice and hence, improving relations and including the Sami in regional economic development requires sensitivity to the capacity of Sami communities and organisations to effectively engage while navigating inherent power asymmetries in interactions with government and industry. One cannot say that there is one view of regional and economic development that encompasses the Sami perspective. There are various organisations and interests that each may have their own perspective on these issues and they are not always compatible. This complicates the governance process.

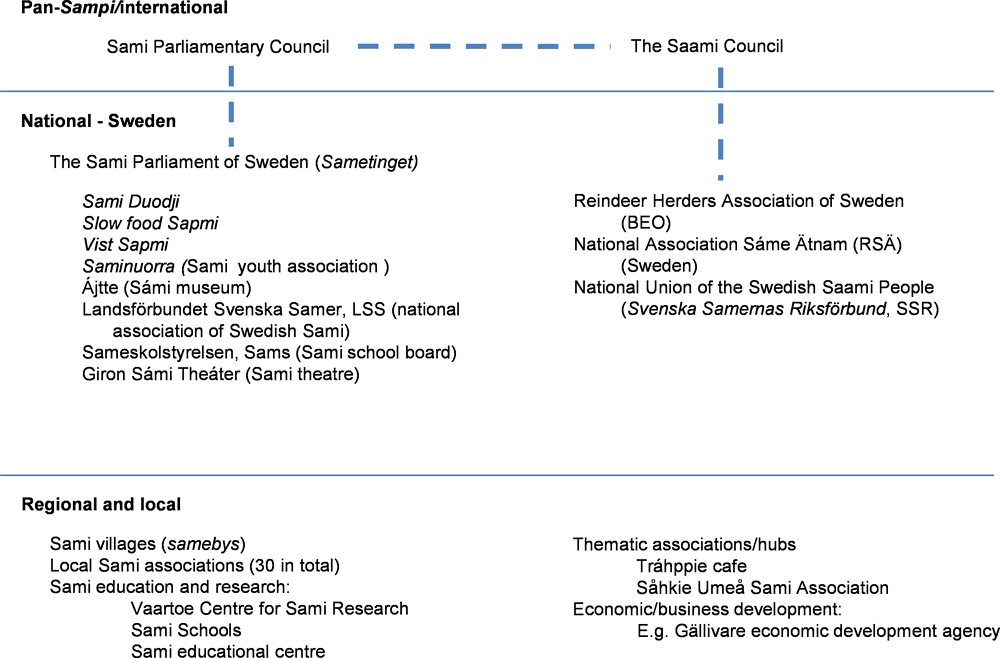

Sami identity is unique in that it is at once pan-Sapmi, extending across borders and different governance and policy contexts, and also very local – as illustrated by the multiple dialects of the Sami language and the institution of samebyar. Pan-Sapmi institutions include the Saami Council (est. 1956, formerly the Nordic Sami Council), which is an umbrella organisation for the Sami living in the Nordic countries. The Saami Council makes statements and suggestions on issues affecting Sami industries, rights, languages and culture. At the political level, there is the Sami Parliamentary Council (est. 1998) which comprises 21 members, appointed by the respective Sami parliaments from among the representatives elected to each of them.1 These pan-Sapmi organisations provide an important venue to discuss self-determination and through which to tackle issues of cross-border co-ordination which are important for the reindeer herding industry and hence, for regional development. These organisations engage with national governments and through the Nordic Council of Ministers and not generally at the level of regional governments.

Within Sweden, the Sami Parliament of Sweden (Sametinget) – as an elected political body – has a particularly important perspective on regional and rural development. It represents a diversity of voices and is at present composed of eight political parties. The Sametinget notes that it sees the Sami as largely governed by conditions outside the Sami community and wherein the business policy is a result of priorities and efforts decided by the state (including County Administrative Boards) and municipalities, with minimal Sami influence. Moreover, they remark that strategies for the inclusion of the Sami in regional development policy are not uniform – they differ considerably from region to region including across municipalities within a region. Where the Sami are included in discussions regarding regional development, the Sametinget argues that this is often done in an indirect manner as a way of enhancing the attractiveness of the tourism industry (Sametinget, 2018[1]). OECD analysis of how the Sami are included in the northern region’s strategic plans reinforces this point.

The Sami Parliament has regular contact with several central government authorities, five County Administrative Boards and a large number of northern municipalities. With the current workload and resource allocation, the Sami Parliament argues that it cannot fully fulfil its statutory role, neither at the official level nor at the political level and as such, has requested increased administrative appropriation. The Sami Parliament estimates that it will require another three full-time employees to better manage its affairs including its responsibility for international issues and business development, and to expand its influence in areas where there is currently no responsible manager such as education, Sami social care, cultural heritage and Sami health (Sametinget, 2018, p. 7[2]). In 2018, funds for the Sami Parliament were increased for cultural activities. It is important to note that there are ongoing debates about whether the Sami Parliament’s role as both a political body and agency of government undermine its efforts at self-determination – in contrast to the independence of these bodies in Finland and Norway (Box 3.1).

Sami rights to self-determination have been gradually recognised across the Nordic states with the creation of Sami parliaments – democratically elected Sami institutions that can represent Sami political interests both nationally and internationally – have been fundamental to realising this imperative. While Sami leaders seek recognition of the unqualified right of the Sami people to self-determination, in practical terms, the aim is to ensure Sami autonomy and self-government in matters relating to their internal affairs, including their own economic, social and cultural development (Henriksen, 2008[3]). This includes the right to exercise control over traditional Sami lands and natural resources. The constitutions and laws of Finland, Norway and Sweden recognise Sami rights in different ways and while Sami parliaments exist in all three states, their roles and responsibilities differ.

An umbrella organisation – the Sami Parliamentary Council – comprises 21 members appointed by the respective Sami parliaments from among the representatives elected to each of them. The Sami in Russia only have observer status in the Sami Parliamentary Council as they do not have their own parliament (Henriksen, 2008[3]).

Finland

Sami rights in Finland are defined around geographic parameters; they apply only to the three northernmost municipalities in Finland (Enontekiö, Inari and Utsjoki) and to the Sami reindeer-herding district Lapin Paliskunta in the municipality of Sodankylä. Under the Finish Sami Act, the relevant authorities are required to provide the Sami Parliament with the opportunity to be heard and to negotiate on any specific questions falling within the scope of Section 9 of the Sami Act. However, this is in practice treated as a duty to consult the Sami Parliament; negotiations seldom take place. In practical terms, the Sami Parliament in Finland remains an advisory body with limited authority and decision-making power. Its political activities are also restricted by budgetary constraints.

Norway

Norway has constitutional guarantees for Sami rights and the state is obliged to create the conditions necessary for the Sami to protect and develop their language, their culture and their society. The Sami Parliament (est. 1989) is regarded as an important part of the implementation of these rights and its mandate includes all questions that the Parliament considers to relate to the Sami and has the authority to make decisions when this follows from legislative or administrative provisions. However, the Sami Parliament is formally still an advisory body, with limited decision-making powers.

Norway has an administrative area for the Sami language (applies to seven municipalities) where Sami and Norwegian languages have equal status as national languages. The 2005 Finnmark Act recognises that the Sami have ownership and usufruct rights to lands in Finnmark County. Around 95% of the land in Finnmark County (about 46 000 km2, an area approximately the size of Denmark) was transferred from state ownership to a new entity called the Finnmark Estate – a joint body of the Sami Parliament and the County Council of Finnmark. The act contributes to the implementation of the natural resource dimension of Sami self-determination. The status of Sami rights to land in other counties remains unresolved.

Sweden

Like Finland and Norway, the Swedish national parliament has adopted a Sami Parliament Act that provides for the establishment of the Sami Parliament. The Sami Parliament is tasked by the act to promote a dynamic Sami culture and is mandated to make decisions about the distribution of state funds from the Sami Fund for Sami culture and organisations, and to other state funds that are placed at the collective disposal of the Sami. The Sami Parliament is also mandated to appoint a board for the state agency the Sami School Boards, direct Sami linguistic work, participate in social planning and ensure Sami interests and needs are taken into consideration, including reindeer husbandry interests in the use of land and water. As such, unlike in Finland and Norway, the Sami Parliament in Sweden is both an elected body and state authority focused on administrative tasks. Sweden’s Sami Parliament describes itself as “an advisory board and expert on Sami issues” (Sami Parliament of Sweden, 2018[4]). The Swedish Parliament recognised the Sami as an Indigenous people in 1977 and in 1999, further recognised the Sami as one of Sweden’s five national minorities. The instrument of government also stipulates that restrictions in the right to practice business activities or pursue a profession can only be made to protect important public interests and never for the sole purpose of financially benefiting certain persons or companies. In 2011, the Swedish Constitution was amended to give explicit recognition to the Sami people, the instrument of government stipulates that the opportunities for the Sami people to preserve and develop a cultural and social life of their own shall be promoted. Interpretation of Indigenous rights in Sweden largely relates to the right to reindeer herding and hunting and fishing if a member of a sameby and, regarding national minority rights, access to some services and education in the Sami language.

Elections to the Sami Parliament in Sweden are held every fourth year. There are 31 Members of Parliament in the Sami Parliament’s highest decision-making body, the Plenary Assembly. In addition, around 50 agency officials carry out daily agency tasks.

Within Sweden, other than the Sametinget, there are four stakeholder organisations at the national level: the National Union of the Swedish Saami People which is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) focused on the reindeer husbandry area and Sami business-community issues (Svenska Samernas Riksförbund/Sámiid Riikkasearvi, SSR); the Reindeer Herders Association of Sweden which is a federation of Sami reindeer owners (Renägarförbundet/ Boazoeaiggádiid oktavuohta RÄF/BEO), the National Association Same Ätnam which was founded to strengthen Sami culture and a national youth organisation, Saminuorra. Each lobby for their respective interests. These are relatively small organisations and have limited resources and staff. Youth (especially young women) are leaving the Sami traditional occupations. When discussing measures to strengthen Sami economic development, it is hence crucial to involve this group through, for example, engagement with youth organisations such as Sáminuorra.

While the Sami Parliament reports finding it challenging to interact with all of various funds/programmes and to co-ordinate these resources, this is even more so the case for groups such as sameby, which are small and which are asked to engage on complex land use issues, often directly with large firms (Box 3.2). In effect, Sami organisations often face a capacity issue which impacts their ability to take part in the policy process at the national down to the local levels. Also, as a relatively small community across a large geographic area, efforts at inclusion in regional and rural development come up against some specific obstacles. Sami can have large distances to travel in order to meet up and discuss issues that are impacting them and their interests extend across a large geography and multiple issues.

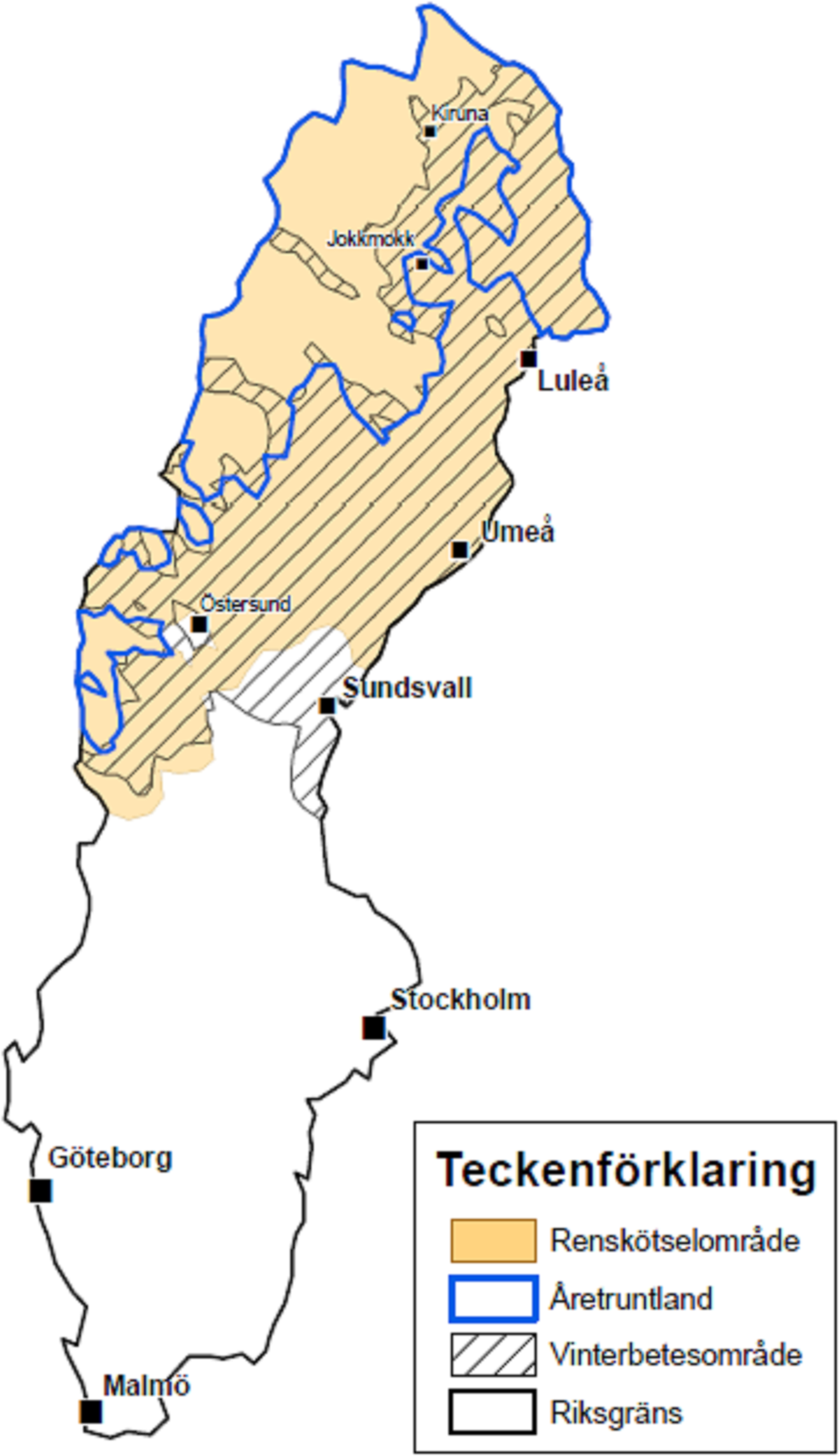

Vision of community development – Sustainable, ecological and culturally-led

A Sami village or community (sameby in Swedish) is an economic and administrative association created to organise reindeer husbandry within its geographic area. As such, it is not a community in the sense that all members live in proximity to one another. In the Swedish part of Sapmi there are 51 Sami communities covering half of the surface of Sweden – which corresponds to the area where reindeer herding is permitted by law and to where land use rights correspond. Idre Sameby in the County of Dalarna is the most southern sameby and one of Sweden’s smaller co-operatives with 4 operating units and a total of 13 reindeer herders. In the southern reindeer herding areas, more Sami tend to have livelihoods exclusively focused in herding than in the North because larger herds can be supported.

The community’s vision for development is based on delivering high-quality products which are grounded in sustainable ecological practices and that have a minimal impact on nature. The samebyar business development is focused on reindeer herding and meat processing (through the sameby-owned slaughterhouse); Sami crafts; the management of landmarks and cultural sites; and hunting and fishing activities and tourism. Idre sameby is unique in that, while few samebyar have their own meat processing facilities, Idre has invested in own slaughterhouse since 1984. The slaughterhouse today is EU approved for both industrial and traditional processing and holds training courses in traditional methods. The facility also holds courses for crafts (duodji). Regulatory changes in the past three years have presented an obstacle for the facility. As of 2016, animal handling regulatory inspections are now carried out by a national inspector (formally they could be carried out by the local Swedish Food Security Agency) and the costs of training have increased. The sameby aims to develop the slaughterhouse as an educational centre for traditional food and slaughtering methods – one that can be used by both Sami, as well as non-Sami hunters.

Business development by sameby members

Sameby members are able to run businesses as individuals; however, the sameby itself is prohibited from taking on other economic activities beyond reindeer herding (as outlined in the Sami village 1971 Act). There are growing constraints on the reindeer herding industry that are making it more difficult to operate; this includes predators to reindeer, climate change impacts and competing land uses which limit pasture land. As such, sameby members – as individuals – may have additional businesses. For Idre sameby members this includes tourism companies which sell cured meat, crafts and offer cultural activities and nature-based tourism. Business owners in the sameby report struggling to reach a broader market. Some members acting as individual entrepreneurs have formed a partnership with the Idre Sapmi Lodge Economic Association which is an entity separated from the sameby. The sameby is a partner and has 3 seats on the board of this Association.

Sameby members have been involved in creating an organisation and event to promote Sami food – part of the Slow Food movement. They report difficulty acing loans in support of these activities. While this work is partly funded through the Sami Parliament and European Union (EU) funding (mostly rural development programmes), programmes such as InterReg Nord have been deemed to administratively onerous and complex to access with stringent reporting requirements. Members are also involved in Visit Sapmi – a programme to educate Sami entrepreneurs about the tourism industry.

Main development and business challenges

The main development and business challenges reported by sameby members echo many of those identified in the Sami Parliament’s SWOT (strength, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis of the Rural Development Programme. Idre sameby members report multiple challenges to their reindeer herding businesses including land encroachment and predators. They express an interest in having information from the national environmental protection agency and to be involved in nature conservation in order to channel tourism activities in a way that respects grazing and to engage in such issues as predators, grazing, and the types of pine in forests. They further report that it is often difficult to access financing for their businesses due to a lack of collateral and that EU funded projects are challenged by a lack of expertise in some areas and a lack of paid staff. While business partnerships are identified as a key way to develop and grow Sami businesses, it is unclear how these can be usefully developed given that the sameby itself cannot pursue economic activities beyond reindeer herding. There is a need for education and training on traditional slaughtering, food preparation, etc. including a need for flexibility from national food inspection and continuous support from Sami Parliament.

Source: Idre Sameby (2018[5]), Samisk Förvaltning, http://www.idresameby.se/index.php?p=f&c=a (accessed on 01 April 2018).

Towards more effective engagement

The multi-level governance framework and policies for both regional and rural development in Sweden shape outcomes for Sami businesses and livelihoods. Within this, the national government plays a major role in structuring policies and programmes at the regional and local levels. Most fundamentally, the way in which the rights framework related to Sami indigeneity are defined and instrumentalised shapes policies and programmes at all levels of government. As has been discussed, it, for example, creates a cleavage between those Sami who are members of samebyar and who practice reindeer herding and those who do not, and for samebyar, places limits on their economic activities outside of reindeer herding as a collective. This is a complex policy landscape and the manner in which the diverse Sami community is included and represented in regional development efforts is not consistent or clear. There are different practices across various sectoral policy areas – particularly as related to land use and access to grazing lands.

Regional reforms in Sweden have changed the landscape of regional economic development. While this offers new opportunities for engagement and inclusion of the Sami in decision making in northern Sweden, at the same time, many of the issues that impact the Sami have not been regionalised and remain the purview of the national government. Sectoral policies – particularly those that relate to how land is used – often have a major impact on the Sami reindeer herding industry; and yet, the manner in which they are connected at the regional and local levels is not always clear. Moreover, while the unique assets of the Sami for northern development are recognised at a general level, regional strategies for development do not have clear mechanisms (policies/programmes) through which to support these assets and promote their development and there are limited incentives for the regional level to engage with the Sami.

A greater understanding and awareness about Sami society and livelihoods is needed. Sami society is characterised by many local and small-scale institutions (samebyar, community associations, educational, arts and cultural institutions) that provide an important function in the reproduction of Sami language and culture, kinship relations, and identity. However, these institutions tend to lack capacity and scale to meaningfully engage in (and influence) decision-making and attract and organise resources to promote cultural activities and exchange, and economic development. The Sami Parliament and other national organisations do play an important role at a national level; however, this tends to be framed in terms of culture and language (and not economic development), and connections with the municipal and regional levels are weak.

More inclusive regional and local governance practices also require the strengthening of Sami institutions and better engagement mechanisms. International bodies have joined the call for reform; the United Nations Committee on Human Rights has recommended Sweden do more closely involve Sami in decision making on issues that impact them as has the Council of Europe (Hagsgård, 2016[6]). The nature of how the Sami are included in decision making in many cases requires stronger guidance and greater formalisation to connect it to regional and local development efforts in a meaningful way. Those Sami groups who do engage need to see that their efforts have an impact.

Engagement takes many forms – from information to consultation and at the most involved level, co-decision making. More structured engagement processes where there is a real impact on outcomes for those involved will help to build trust among actors. Where differences occur, an open and transparent way to manage conflict is needed. In general, the need for more rigour around how engagement with the Sami in Sweden has been acknowledged and there are ongoing efforts to develop more robust guidelines (for example, the Ministry of Culture). This is very promising and should be supported by capacity building efforts with Sami communities, and in relation to cross-cultural sensitivity within public sector organisations (see Box 3.3 for an example).

Sami representatives may lack, for example, the time, money and knowledge of legal and regulatory processes to be best able to voice Sami interests and needs. Public sector agencies may lack the cultural understanding to effectively engage with Indigenous communities. This is an area of concern shared in Australia and Canada. Australia and Canada have made substantial investments to improve the quality of engagement through initiatives to build capacity and cross-cultural understanding. This could be as simple as providing a stipend to help Indigenous peoples with the cost of attending consultation meetings. Other examples include:

-

Indigenous Services Canada – Professional and Institutional Development Program. Funds projects that develop the capacity of communities to perform ten core functions of governance, such as: leadership; membership; law-making; community involvement; external relations; planning and risk management; financial management; human resources management; information management/information technology; and basic administration.

-

Justice Canada – Capacity Building Fund. Designed to support capacity-building efforts in Indigenous communities, particularly as they relate to building increased knowledge and skills for the establishment and management of community-based justice programmes.

-

Indigenous Cultural Awareness Training – Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Ltd. This provides training for public, private and non-profit organisations in regards to cultural awareness perspectives, Indigenous history, Indigenous culture and value systems, and racism and stereotypes.

The counties or municipalities often call for consultations with Sami representatives for which the Sami community can be represented as private persons or organisations often in what are one-off consultations. There is an opportunity to make these discussions more strategic by having annual dialogues and agreements on issues of mutual importance. This could be conducted between the Sami Parliament and other Sami organisations, and involve all northern counties or be conducted separately with each of them. This would help provide a focus point for Sami affairs and representation and perhaps enable discussions about broader development issues as opposed to individual projects and initiatives. Another possibility is for there to be a secretariat close to Sami communities – with samebyar joining together to form a board with a chief executive officer that could provide a collective voice for multiple samebyar and build expertise in different areas to address common issues.

Policy options to improve engagement with Sami society in the context of regional and rural development are:

-

Establish an annual dialogue and agreement between the Sami Parliament and the northern counties (County Administrative Boards [CABs] and regions) to govern strategic co-operation in areas such as economic development, culture and language, land management, and health and education services.

-

Implement a framework and tools for the duty of public bodies (CABs, regions, municipalities) to consult with the Sami, and complement this with initiatives to build governance capacity and cross-cultural understanding.

-

Assess the resourcing implications of the duty to consult on the administrative capacities of the Sami Parliament to ensure it is effectively implemented.

-

Growing competencies for regional planning offer a unique opportunity for regions to adopt a strong spatial vision for development. This spatial vision should include the Sami. The Sami Parliament in Sweden has expressed an interest in a regional co-operation agreement of the type that is used in Norway which could be used to consider land use issues from this integrated perspective.

Land management and regional development

The question of how land is used, how land rights and consultations on new developments are structured and who is and should be involved in this process are among the most challenging issues to address in terms of how the Sami are included in regional and rural development. An analysis by the Sami Parliament of the threats faced by Sami in relation to their traditional lands and Sami society more generally puts the issue of rights to land and natural resources front and centre (Sametinget, 2015[7]). The Sami Parliament has expressed the view that a lack of self-determination over land rights including the application of the principle of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) is hindering their development. Other top threats identified all also related to land use and the environment: these include the commercial use of land for resource exploitation and extractive industries is seen as a threat to traditional livelihoods; the impact of increased recreational activities and tourism; the management of nature reserves and national parks which can restrict reindeer movement; a growth in the large carnivore population and; climate change. This is one of the most visible issues involving the Sami in the north. In media reporting in Sweden, the Sami are most often reported on in relation to reindeer herding activities and within this, related to land use conflicts (Tyler et al., 2007[8]). Sweden does not provide the means for Sami communities to meaningfully engage and influence early-on in planning and impact assessment, e.g. via community-led studies or co-management (Larsen, 2017[9]).

For the reindeer herding industry to continue and to thrive, access to grazing lands that are appropriate for the reindeer and that can sustain them (e.g. that support lichen) is critical. However, land use issues extend much beyond this; they are connected to broader visions of the region’s development including how the tourism industry should be pursued; whether land is meant for protection and preservation or use, and if so, of what kind; and the extent to which the region should pursue mining, forestry and other natural resources-based industries as a path to development. There are also ongoing debates as to the extent to which local communities adequately see the benefits of extractive industries and natural resources development.

These debates are fundamentally about the future of Sweden’s northern regions. The northern economies have long been driven by its abundant natural resources, including its rivers which have been harnessed for hydroelectricity and which have spurred Sweden’s industrial development. Forestry and mineral extraction have been developed which have also driven investments in infrastructure. Value-adding has evolved in relation to scientific research and technical services linked to these activities. But this development model has also brought limited direct employment to rural areas, and costs in terms of environmental damage and loss of biodiversity. These are important debates within society and among the Sami, and as will be discussed in Chapter 3, current models of governance and consultation are largely not adequate in addressing them. The remainder of this section discusses land use policies and regional development.

Sami land rights and the regulation of reindeer herding

As discussed in Chapter 1, reindeer husbandry is an industry under stress. Industrialisation and the cumulative effects of forestry, wind and hydropower, mining, and infrastructure development have, among other management problems, resulted in an extensive reduction of the availability of winter grazing land (lichen-abundant forest) and access to migratory paths (Buchanan, Reed and Lidestav, 2016[10]). Beyond this, chronic wasting disease among reindeer has placed limits on their transport between different areas – e.g. from Sweden to Norway.2 Due to the implementation of the EU habitat policy directives, the hunting of large carnivores has been limited and their numbers have increased as a result (European Commission, 2018[11]). This has had led to declines in herd size, for which compensation is provided. Taken together, these various impacts have required reindeer herders to be adaptable to changing conditions. From an economic point of view, the demand for land allocated to reindeer husbandry is greater than supply and production can only be expanded within ecological limits.

While Sami land rights were recognised from the 1600s (tax land), Sweden’s 1971 Reindeer Husbandry Act does not specifically address land rights issues. The Swedish system is based on the notion that different land uses can coexist and that conflicts can be solved locally. Natural resources development and Sami reindeer husbandry co-exist as activities of national interest. However, in practice, there is competition for the same resources and the tools with which to resolve such conflicts are inadequate. Today, the legislative framework recognises Sami land rights as a right to use and only for those who are practising reindeer husbandry. In terms of competing uses for land, they are treated as one of many stakeholders. There is no right of refusal for developments by the Sami on the lands that they use for reindeer husbandry. Sami are typically consulted when large development projects are being proposed on sameby lands; however, the methods of this consultation differ. In several cases, policy changes related to Sami land rights are being realised through court cases, such as the legal case of the sameby of Girjas over its right to determine hunting and fishing in its territory.3 The 1971 Reindeer Husbandry Act also formalised that reindeer herding is an industry which has created some tensions as it is also seen by the Sami as a form of cultural expression.

Ideal types are simplified models. They express pure typologies, which rarely exist in the world. That is, within countries more than one type can co-exist and there may be alternatives to them. There is nonetheless conceptual relevance in such simplification. The possible arrangements for Indigenous land use management can be divided into three ideal types, according to the degree of autonomy granted to the Indigenous community:

-

Self-governance of Indigenous land: The Indigenous group has been empowered by the state to have a level of autonomy over the management of Indigenous lands and natural resources located within it. This conditional autonomy may derive from the self-government capacity of the group, attributed by a treaty or agreement that addresses nation-to-nation relations. Alternatively, it may arise from specific agreements that hand over regulatory authority over environmental issues from the government to the Indigenous group.

-

Joint land management model: In this model of joint, shared or co-operative management, also referred to as co-management, the Indigenous group shares the responsibility and the authority over land issues with government authorities. It may arise from the creation of specific institutions, such as natural resources boards and land councils, which are equally composed of Indigenous and non-Indigenous representatives. It may also come from the creation of protected areas, such as parks or natural reserves, with a management model defined as shared. It can eventually be that the government has the authority over natural resources but the Indigenous group participates in the decision-making process of issuing licenses and permits.

-

Co-existence: In this model, Indigenous groups are considered an interested party in land management issues that affect their designated lands. Their lands may be affected directly, or indirectly, for instance, if a project does not occur in their lands but its impacts extend over them. Without autonomy to decide over such issues, they can nonetheless be part of decision-making processes. They may be consulted in administrative procedures, such as environmental licensing, and influence the elaboration of laws, plans and other policy documents. Sami reindeer herders operate under a co-existence model, with the exception of joint land management in such cases as the Laponia World Heritage Site.

Sweden’s County Administrative Boards (CAB) regulate reindeer herding. The CAB is responsible for protecting reindeer herding as a public interest; ensuring correspondence with the planning act and environmental act, and managing fishing and hunting land use issues and the enumeration of reindeer. The CAB has a wildlife delegation focused on predators and on moose and a delegation on reindeer herding where there are representatives of samebyar and three representatives from the public. In instances where there is a conflict between land users (e.g. between mining activities and reindeer herding), the CAB adjudicates.

Samebyar have annual meetings and decisions can be appealed; the Sami Parliament is the first instance where opinions are tried before going to court. However, in contrast to experiences in Norway, there are fewer resources and there is more limited capacity to co-ordinate interests between Sami communities and the Sami Parliament.

In terms of forestry practices, there is more of a direct relationship between forestry companies and the Sami involving different types of certification. Some certification aims to protect the ecology as much as possible to be compatible with reindeer herding. In 2012, half of all productive forestlands in Sweden were privately owned; the distribution of private forest ownership differs across northern Sweden. It is highest in Jämtlands (Box 3.5). The property rights of forest owners and reindeer herding rights are parallel to one another. All large forest owners (more than 500 hectares) are required to consult with the relevant sameby prior to forest felling and in mountainous areas, forestry firms are required to apply for a permit to fell.

There is no impact assessment requirement and no possibility to appeal forestry plans. Given this, within the forestry industry, relations with the Sami depend to a large extent on goodwill and there are many positive examples of this. Samebyar have worked with the forestry industry to develop good practices. They have developed guidelines on how to handle notifications in reindeer herding area. There is also a joint project between the Swedish forestry industry and the National Association of the Swedish Sami (Svenska Samernas Riksförbund, SSR) called Forest and Reindeers Training which was developed in order to increase knowledge and mutual understanding between the groups. While the role that forestry has played in causing a significant decline in the area of lichen-abundant forests is debated, the industry’s practices do play an important role in reversing the trend and improving ground lichen conditions (Sandström et al., 2016[12]). While there are many examples of good relations, there are also cases of conflict and, where conflict does occur, there are limited means to resolve them since the process is left to informality. The process works well until it does not.

In 2012, half of all productive forestlands in Sweden were owned by individuals; a quarter by private-sector companies/corporations; 15% by state-owned companies and others (Skogsstyrelsen, 2014[13]).4 Of the three northern counties where reindeer herding activities are most common (Jämtlands, Västerbottens and Norrbotten), forest ownership differs considerably. In Jämtlands County, the majority of productive forest land is held by private sector companies and individual owners in almost equal share. Meanwhile, in Västerbottens County, individual companies are the largest forestry owners followed by “other” owners such as State agencies, the Church of Sweden or local and county councils. In Norrbotten County, ownership by these governmental and non-profit authorities (i.e. other owners) dominates.

The need for clarity on rights to consultation and increased capacity for the Sami to be effective partners in engagement

Stronger and more consistent parameters around how and when consultation should occur and with whom are needed. This is important not just for the Sami but for the industries pursuing development in the north for whom it is unclear who they should consult with and how. Long delays in the permitting processes are reported. Within the environmental impact assessment permitting processes for mine exploration and development, the responsibility for dialogue with local communities, including the Sami, is placed upon the companies and the principles of free, prior and informed consent are not always well respected (Lawrence and Moritz, 2018[14]).5 The CAB has also a responsibility to survey the general interest of reindeer herding. There is no official national government policy, guidance or tools on how mining firms should engage with the Sami as yet in terms of practices of engagement. From an international law perspective, reindeer herders are also rights holders as well as being stakeholders; however, free, prior and informed consent is not required in Sweden at the moment for mining companies. As such, practices can differ considerably.

During the mining exploration phase, working plans are developed which present an opportunity for first dialogue. If a project proceeds and is granted a permit, some firms may sign an agreement with the relevant sameby regarding how land will be used (these are not typically very detailed agreements).6 There are different working practices within the industry on how to engage with the sameby. In recognition of the amount of time and effort that such engagement takes, some companies offer compensation for costs incurred (e.g. paying for peoples’ time to properly engage with them). Some mining communities work on reindeer herding studies in order to understand the impacts on reindeer herding. Prevention and compensatory frameworks are a working practice in the industry. Land use plans can help to facilitate dialogue with government and industry – for example, the sustainability land use plan for Maskaure Sameby which is used in talks with government officials and industry.

Those Sami who are not part of the Sami parliament and/or a sameby member have no rights in these procedures. The Sami Parliament gets to present a statement. In addition, samebyar are recognised as stakeholders according to legislation and preparatory works. Other Sami outside the samebyar are only considered parties/stakeholders if they can show (through property register or similar) that they own property or hold special rights to property within the exploration area (that is on the same conditions as other non-Sami rights holders). The Swedish model is largely based on the idea of reindeer husbandry as a business consulting with another business (e.g. mining and forestry). However, mining companies and Sami communities can have diametrically opposed views of their values and interests (Lawrence and Larsen, 2017[15]).

A recent report by the County Board of Norrbotten has found that after extensive consultations with Sami communities and mining companies, mounting conflicts observed in recent years cannot be resolved through micro-scale dialogue between these parties and that the key task is for the government to legislate on unresolved questions regarding Sami land rights. Only with greater legal certainty and a more level playing field can the parties engage in constructive negotiations (Länsstyrelsen i Norrbottens län och Sweco, 2016[16]).

The number of valid exploration permits for mining has declined over the past decade

The largest mining companies in Sweden are LKAB and Boliden, which together account for approximately 70% of exploration expenditure in Sweden. Most of the exploration carried out in 2016 was brown field exploration, i.e. exploration in, or close to, existing mining sites. At present, the number of approved exploration permits is roughly the same as the number of exploration permits that are expiring. A rule of thumb is that around 1:1000 exploration permits leads to the opening of a mine. The number of valid exploration permits in Sweden over the past 10 years has gone from approximately 1 300 in 2008 to approximately 600 today. The majority of these exploration permits can be found in the counties of Norrbotten- and Västerbotten and an area in mid-Sweden called Bergslagen. Statistics for reindeer herding areas specifically are not available.

Out of all valid exploration permits in Sweden over the past 10 years, just 42 have been granted approval as exploitation concessions. During the same period, the Mining Inspectorate rejected seven applications for exploitation concessions. Most of the applications for exploitation concessions are extensions of older existing mines.

The environmental permitting process can take between 2-10 years

The length of time that it takes to obtain an environmental permit for mining activities can differ significantly depending on the nature of the operations -- anywhere from two to ten years. The vast majority of permits in the past decade have been extensions of existing operations or restarts of previously abandoned mines. Environmental permits for temporary or time-limited increases in production in existing operations tend to have shorter lead times while cases concerning new mines tend to have longer lead times.

Source: Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, Sweden, 17 April 2018; Bergverksstatistik 2017. Statistics of the Swedish Mining Industry 2017; Geological Survey of Sweden. Periodiska publikationer 2018:1.

Mineral and metals extraction is regulated by the Minerals Act under which there are three main permitting processes before a mining operation can start.

-

1. An exploration permit (undersökningstillstånd) gives access to the land and an exclusive right to explore within the permit area. It does not entitle the holder to undertake exploration work in contravention of any environmental regulations that apply to the area. Thus, no actual exploration work can be carried out without a valid plan for operations. The plan for operations is presented by the permit holder to the landowner or holder of special rights. The sameby are considered holders of such special rights in the Minerals Act. Landowners or reindeer husbandry have the possibility to object to the plan of operations. If the permit holder does not change the plan of operations according to the objections, the landowners or the sameby can request that the Chief Mining Inspector settles the plan. The Chief Mining Inspector then has the possibility to add restrictions to the plan of operation to safeguard e.g. ongoing actives in the area.

-

2. An exploitation concession gives the holder of the permit right to the mineral covered by the permit for up to 25 years. However, the permit does not allow any mining operations to commence. During this process consultation with the sameby is the same as for landowners. In the Environmental Code, some areas have been declared as national interests for reindeer husbandry. In those areas, the protection from exploitation is even stronger according to the Environmental Code. However, the same area may be of national interest due to its deposits of minerals. In case of a conflict between inconsistent national interests, preference shall be given to the purpose that in the most appropriate way promotes a long-term use of land, water and the physical environment in general, when an exploitation concession is being considered. The assessment shall include ecological, social, cultural and socio-economic considerations. When an application for an exploitation permit is examined, the full scale of the mining operation is not yet known. The design of the mining plant is not final at this stage and it is thus not possible to correctly assess the full impact of the planned operations on the activities and the environment outside the area covered by the exploitation permit. This is considered in the next stage, the process of environmental permit.

-

3. In the application for an environmental permit, the same procedures and regulations apply for mining operations as for all other industrial operations that may affect the environment. This is the most substantial and time-consuming part of the process. This process sets the conditions under which the mine may operate. At this stage, the final design of the mining operation is decided and the full impact on activities and environment outside the mining plant is evaluated and regulated. A permit will define the conditions for the design, building, operation and closure of a mining installation. Such an application shall be supported by a comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment, in which formal consultations with stakeholders will be practised.

During all of these three steps, consultation with Sami sameby is the same as with landowners and with owners of other special rights than reindeer husbandry. During the consultations, sameby have the possibility to raise objections to the planned operations and request that the permits are subjected to special conditions to limit the impact on the reindeer herding in the area. As of 1 August 2014, the Minerals Act has been modified so that, if requested, the plan of operations (which is necessary before any exploration can start) must be provided in Sami language. In addition, a valid plan of operations must be sent to the Sami Parliament. The Environmental Code contains regulations for the protection of areas of national interest for reindeer herding and for mineral extraction. When there are competing claims for a particular area, regulations in the Code specify how to give preference for one use over the other.

An exploration does not automatically lead to a significant impact on the natural environment. Exploration can be something as simple as flying over the ground to carry out airborne geophysical surveys. When a right to exploration is issued by the Chief Mining Inspector, there is an opportunity to condition the permit in order to minimise the impact on reindeer herding. Only some exploration permits will result in new mines. The number of active metal mines in Sweden has since the year 2000 remained relatively constant at around fifteen.

Samebyar receive intrusion compensations according to the Mineral Act for mining activities carried out within their areas. This compensation aims to cover losses and damages suffered due to these activities. In discussions with reindeer communities and husbandry companies, surveying agencies put a value on land and land used for reindeer herding a pasture is not as high as the value of land that can be taken out when starting a mine or business. Correspondingly, compensations lower for pastureland. For samebyar, this framing is focused on development in economic terms only and does not place intrinsic value on reindeer herding as central to cultural reproduction for the Sami.

Source: Questionnaire for Linking Indigenous People with Regional Development in Sweden.

Sweden is presently conducting an ongoing examination into whether environmentally hazardous activities within the environmental permitting process are designed in a way that promotes investments that drive technology and method development against reduced negative environmental impact. However, a broader review of the environmental permitting process is warranted. One of the major issues that needs to be addressed is the timeframe for receiving permits related to mining (exploration and development). The Saami Council has expressed concerns that the revisions to how environmentally hazardous activities are treated within the environmental permitting process it will make it easier to get a permit and that it will diminish the environmental assessment process. They have also raised concerns about the costs samebyar bear when they are asked to consult on a wide range of issues. Similar issues have been raised in Finland regarding mining developments and guidelines on reindeer herding have outlined modes of consultation.

Countries such as Canada have early engagement, upstream planning, and regional planning as part of their environmental permitting processes, while in Sweden the stakeholders often meet in regards to individual projects, as required by law. The Environmental Assessment process in Canada is often used as a channel to express rights-based claims, in the absence of other channels to express grievances, and to discuss development plans and strategies, in the absence of Indigenous participation in broader strategic planning processes. That is, instead of discussing the specific project, it provides an opportunity to discuss broader issues related to development. One potential best practice in this regard is The Norwegian Minerals Act (2009) which has established a formalised mechanism for the Sami Parliament to participate in environmental review processes, including those linked to the government’s strategic plans and policies, strengthening the efficacy of the Sami’s involvement in Environmental Assessments (EA) and promoting the legitimacy of EA processes (Noble et al., 2015[17]).

The absence of Sami rights to the ownership of land coupled with co-existence of Sami rights related to reindeer herding along with minerals extraction as issues of national interest generates uncertainty and conflict for all parties in northern Sweden. In the absence of legislation that clarifies unresolved questions regarding Sami land rights, there are several actions can help to better structure the engagement process with the Sami for natural resources exploration and development:

-

Develop clear and consistent guidelines for the mining, forestry and energy industries together with the Sami Parliament and other Sami stakeholders on how the engagement process should proceed and who should be involved in the process, including parameters around what type of information is provided to communities at each step of the process.

-

Ensure upstream engagement and rules around how and when notifications should proceed and the nature of the engagement (format, etc.) within the framework of the Minerals Act and Environmental Code.

-

Strengthen the capacity of samebyar to be effective partners for engagement; this may entail financial resources alongside some greater overall institutional and analytical capacity to manage demands for consultation.

Specific legal instruments have been developed in Australia and Canada that enable negotiation about benefits from resource extraction for Indigenous communities. In the case of Canada, a number of shortcomings have been identified in their Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs), which include: lack of transparency that limits sharing of best practices and evaluation of outcomes, unequal distribution of benefits to community elites, and how some elements can be realised if they are dependent on public investment in infrastructure and services (e.g. access to education and training).

Australia – Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUA), entered between people who hold “native” title over a particular area and a mining developer. ILUAs can cover topics such as native title holders agreeing to a future development; how native title rights coexist with the rights of other people; access to an area; extinguishment of native title; compensation; employment and economic opportunities for native title groups; and cultural heritage. This instrument was created to give a transparent and flexible way to address the potential conflict between people who hold native title and resource development. These agreements are usually processed, notified and registered in a period of less than six months, and are an alternative to making a native title determination through a judicial process.

One example of ILUA is the agreement signed in 2001 between the Weipa bauxite mine (Rio Tinto Alcan), the Aboriginal community, four Shire Councils, the Queensland state government and the Cape York Land Council. The Agreement led to the creation of the Western Cape Communities Trust (WCCT), which lays emphasis on local capacity building and business development. The mining firm has also committed to undertake various employment, training and infrastructure initiatives.

Canada – Impact and Benefit Agreements

In Canada, the Crown has a legal duty to negotiate with Indigenous peoples on traditional lands who are affected by development. IBAs have evolved as a contractual instrument to negotiate benefits for Indigenous peoples related to resource developments. Prior to 2005, IBAs focused primarily on benefits relating to jobs, training and procurement opportunities. Since 2005, IBAs have increasingly emphasised economic benefits and financial issues such as royalties and direct payments. They can now contain provisions related to labour (e.g. agreed targets for Indigenous employment and training), economic development (e.g. procurement opportunities), community (e.g. social programmes and community infrastructure), environmental protection, financial (monetary compensation and monitoring arrangements), and commercial (e.g. dispute resolution). These contracts are usually confidential.

Source: OECD (2017[18]), Local Content Policies in Mineral-Exporting Countries, Working Party of the OECD Trade Committee.

Learning from the Laponia governance model

Municipalities and regions in northern Sweden have shown interest in the Laponia governance model and how it could be applied outside of the context of a World Heritage site. Laponia is a large mountainous area in northern Sweden which was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996. The World Heritage comprises an area of 9 400 km² in northernmost Sweden, including some of the largest national parks and protected areas in the country, and the most important cornerstones are nature, the Sami culture and reindeer industry and the historical heritage. Prior to being a World Heritage site, Laponia was a national park and nature reserve wherein Sami reindeer herders work with the County Administrative Board on land use issues including predatory inventory.7

Today Laponia is managed through a decentralised governance model at the local level and is often noted as a best practice in terms of how to meaningfully include Sami in land management practices in order to tackle such issues as land conservation and managing tourism alongside reindeer husbandry. The Laponia regulation provides a framework for the management of the UNESCO World Heritage site, Laponia. Management of the site is governed by the Laponiatjuottjudus, a locally based organisation with its headquarters in Jåhkåmåhkke/Jokkmokk. Laponiatjuottjudus includes representatives from eight Sami communities, the municipalities of Jokkmokk and Gällivare, the County Administrative Board in Norrbotten County and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. In the Board, the Sami representatives are in majority and all decisions are taken by consensus.

In developing Laponia as a protected area and World Heritage site, a key issue that needed to be addressed was how to integrate the reindeer husbandry act in the Laponia area. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were many discussions and conflicts between Sami reindeer herders and the Swedish state regarding this issue and out of these, it became clear that a different type of governance model for the area was needed for this unique site. Over the duration of five years (2006-11), a co-management model was developed. During the process, the parties could agree on a new regulatory framework, wherein the rights according to the reindeer husbandry act were applied in full. Municipalities accepted this arrangement pending consensus on the board; on issues where board consensus has not been possible, working groups are drawn on to help overcome conflicts. The management of Laponia has been open to traditional knowledge and Sami elders are invited to discuss how they use the land with the Laponia. There are efforts to develop a common view of how to manage the area.

However, even within this co-management model, some issues related to the capacity of the Sami to actively participate in decision-making remain. For example, Laponia is able to access funds for protected areas; however, the financing of work on reindeer herding is not permitted in the grants that are now provided from the national government. A landscape map has not been conducted because the office does not have the competence. Such mapping could be used to work with samebyar in order to identify strategic places and provide permission to tourist agencies. In parts of Laponia, rights for reindeer herding are deemed well applied, while in other areas, conflicts remain. There are for instance tensions between the intrinsic value of Sami influence and the instrumental value of Sami reindeer-herding communities (Reimerson, 2016[19]).

The Laponia model is a best practice for co-management in Sweden. The Laponia model has been described “as a victory for Sami political struggle for land rights and influence, and as an important step in the Sami people’s decolonisation process” (Reimerson, 2016[19]; Samer, 2010[20]). This model is currently being reviewed and some parties have expressed the unwillingness to continue it with such a strong Sami mandate in the future. This would be a mistake. Laponia’s co-management model has meaningfully included Sami in decision making and while operational issues remain (such as the need of enhancing capacity for Sami to engage), it is a model that should be strengthened and emulated in other areas

The need for enhanced regional spatial planning and an integrated perspective

Reindeer husbandry activities are part of the national framework for land use planning but aspects of land use management practices which are important for reindeer herding are embedded in sectoral policies which can be siloed (e.g. across tourism, large predators, transportation and energy investments). While there are certain rules regarding planning and reindeer herding in the Environmental Code, there is no integrated planning perspective that relates to the goals of reindeer husbandry – regional or sameby land use planning. This results in an “absence of cumulative effects assessment, lack of defined threshold values for significance determination, absence of effective landscape/regional planning tools, independence in impact analyses, and unrealistic administrative work-loads on Sami communities” (Larsen et al., 2017[21]).

Sweden’s planning system is characterised by a “municipal planning monopoly” (Pettersson and Frisk, 2016[22]). Municipalities prepare Comprehensive Plans and Detailed Plans and issue building permits based on those plans and other relevant regulations. In order to make their comprehensive plans more strategic, municipalities are supposed to consider a regional perspective. In support of this, County Administrative Boards represent the national government’s interests in the planning process; provide municipalities with data and advice; and co-ordinate in the case of conflicts between municipalities. Municipal land use planning is not the most relevant unit through which to consider the interactions with reindeer husbandry. There are demarcated areas for reindeer husbandry identified in the zoning law and where there is an encroachment on these lands, compensation is granted.

Currently, there are no rules or incentives to facilitate the development of strategic spatial plans at a regional scale and mechanisms to link infrastructure and land-use planning are also weak (OECD, 2017[23]).8 Each state agency has their own sectoral plans and the CABs have responsibility for understanding their application in the region. County Councils are also required to consider sectoral elements in their own plans. The CAB tries to uphold a dialogue with relevant stakeholders to balance national and local interests during the permitting process for new development. The local municipality does not have the opportunity to review or state an opinion in relation to what is defined as national interest. In general, new developments are addressed on a case-by-case basis through the administrative permitting process is an administrative process. This is not a venue through which to discuss the strategic vision for the region.

There is clearly a need for an integrated perspective across spatial and land use planning and sectoral dimensions – transportation, infrastructure, and critically, natural resources and extractive industries (energy, mining, forestry). The land use needs of Sami communities should be considered within land use and management impact analysis and this should be done in all sectoral permitting processes. The weight of Sami perspectives within the permit decision making processes is often weak and/or treated in an inconsistent manner. It can be a struggle for people to see the connection between land use issues and reindeer husbandry – issues of succession and so on all impact economic outcomes. These laws have a concrete consequence in communities. There is no compensation for forestry encroachment or for encroachment of rights; however, compensation is paid when reindeer herding rights are suspended. In the mountainous area, landowners are required to apply for a permit to fell. If a permit is given, the Swedish forest agency decide upon considerations to be taken to the reindeer husbandry if the forest operations have a large impact on the reindeer husbandry. There is some compensation for environmental damage (50% to Sami funds and 50% to the Sami village).9 The regional level has a very limited impact on these issues and it is hard to build co-operation between regional and Sami interested because they rarely meet on these levels.

There have been growing calls for enhanced regional planning in Sweden and several recent reforms have sought to improve the co-ordination between different levels. In 2011, changes to the Planning and Building Act introduced new requirements for comprehensive plans to incorporate national and regional objectives. In 2013, the government established a committee to further investigate the need for regional spatial planning and to improve the co-ordination of planning at the regional level. Furthermore, Sweden’s national strategy for sustainable regional growth and attractiveness 2015-20 emphasises the need to better co-ordinate local comprehensive planning and regional development efforts. The strategy states that by 2020 each county should have integrated a spatial perspective in its regional development policies.

One important resource to help develop an integrated perspective on land use which incorporates the Sami perspective is reindeer management plans. Figure 3.2 depicts the reindeer herding area in general (not detailed). Samebyar began establishing reindeer management plans in the 2000s. Reindeer management plans describe how the Sami use land for reindeer herding and are used to inform others of these activities in order to co-ordinate multiple land uses and manage any conflicts. The maps depict grazing grounds, migration routes, rest area grazing, difficult passages and installations and describe of external factors on how the lands can be used in future reindeer husbandry (Sametinget, 2018[24]). This is often combined with GPS data on reindeer migratory movements. This mapping work is carried out by reindeer herding districts and is used in consultation on such matters as:

-

Forestry, mining, and energy developments (e.g. wind power and hydropower).

-

The protection of cultural environments.

-

Mountain use issues (e.g. snowmobile and hunting) and the impacts of outdoor recreation (tourism).

-

Predator issues.

-

Road planning, infrastructure development.

-

Municipal comprehensive plans, environmental impact assessments, nuclear fuel and waste management, and other planning.

-

Rights to reindeer husbandry disputes (Sametinget, 2018[24]).

Reindeer management plans are produced by samebyar and the data contained therein is owned by them. They are provided to state authorities on a voluntary basis. The Government of Sweden provides financial support to the Sami Parliament to update Reindeer Management Plans. The development of these plans is quite complex and work intensively for the herding communities. As such, smaller samebyar may find it more difficult to develop them.

Samebyar can be hesitant to share their detailed data on how land is used by their herders because it can be misconstrued; reindeer herding needs to be extremely adaptable to changing conditions and data from one or even several years does not necessarily represent future use. Furthermore, while this data captures the movement of reindeer herds, it does not capture the depth of traditional knowledge which is not mapped and yet equally important to understanding the industry and how land is used. If land use is viewed as static by industry or governments, this could lead to a loss of rights related to its use. It is thus important to consider from the perspective of the Sami how data can be interpreted and what restrictions and possibilities there should be in terms of access and use. A Sami lens on how data is constructed, collected and used is thus critical see discussion in Box 1.9 on Indigenous data sovereignty).

Regional spatial planning that is better integrated, and more inclusive of the Sami, can be achieved by:

-

Incorporate Reindeer Management Plans into strategic spatial and land use planning, and permitting decision-making.

-

Allocating a competency to the body responsible for regional development to produce a regional spatial plan and ensure it is integrated with planning for future natural resource use, and Sami land use.

Towards a comprehensive national Sami policy

The preceding discussion has outlined the policy environment for Sami affairs and the manner in which the Sami are connected to regional development. Throughout, it has been stressed that policies directed to the Sami are limited to a subset of issues related to the manner in which rights frameworks are structured. There are policy siloes that make it difficult to have a comprehensive understanding of the manner in which the Sami are engaged and how policies are directed to them. Moreover, the absence of a comprehensive framework for many issues – notably, how the Sami should participate in decision making regarding land use issues – has led to these decisions being pushed to the local level in an inconsistent manner where there are clear power asymmetries in terms of how any conflicts of interest are resolved. Amidst this policy environment, samebyar and the Sami Parliament are identified as the main partners for policy engagement, albeit they may speak with diverse voices. These actors feel under an increasing amount of pressure to engage with different levels of government and industry on a wide range of issues. However, they have limited capacity to meaningfully participate in the host of engagement activities and the informality of how they are often included in decision making leads not only to engagement fatigue but to scepticism as to the value of these endeavours.

This situation is not sustainable. In recognition of this, the national government is working on developing guidelines for consultation with Sami on culture-related issues, but this is not enough. A comprehensive national Sami policy is also needed. As noted in Chapter 1, there is no collection of Sami legislation in one place which makes it hard to provide an overview of Sami rights and to understand how the Sami should participate in decision making. It also means that there is no single point in the ministries accountable for all decisions about Sami affairs or for monitoring a cohesive Sami perspective on different decisions in other sectoral policies affecting Sami affairs. A first step to evolving a comprehensive framework for Sami affairs is to take stock of the range of policies that impact the Sami in order to gauge their impact, how they could be better co-ordinated and how Sami individuals and communities could be more effectively engaged in decisions that impact them. Such policy assessment requires improved data on Sami economic activities and well-being (see Chapter 1 for discussion) and should directly address the manner in which regional and municipal governments should support Sami social and economic development.

The current policy environment is fundamentally a reflection of how Sami rights are identified and the distinction made between those who are members of a reindeer herding community and the broader Sami community which are recognised in law as a national minority. This rights framework has on the one hand frozen the activities of samebyar by placing limits on their economic activities while at the same time creating a division within Sami identity in terms of those who are members in samebyar and those who are not. Thus, in the medium to longer term, Sweden should consider how this rights framework could evolve to meet the contemporary needs of Sami people and to better support their unique cultural identity and self-determination. Opening up rights frameworks to reform is extremely political and undoubtedly a long and challenging process. However, there is growing recognition in many countries that their evolution is critical in order to improve relations and support Indigenous development.

Policy options to improve the policy framework for the Sami in Sweden are:

-

The Government of Sweden, in partnership with the Sami Parliament and Sami institutions, move toward the development of a National Sami Policy that can:

-

1. Identify future priorities for the development of Sami society.

-

2. Assess the current policy framework in an integrated way and identify actions to improve it.

-

3. Clarify responsibilities for Sami society between different agencies and levels of government.

-

4. Establish mechanisms to build the capacity of the Sami Parliament (such as MOUs to govern data, information and resource sharing).

-

5. Establish agreed mechanisms for co-ordination and dialogue between different levels of government.

-

-

Establish an annual strategic dialogue between the Swedish Government and the Sami Parliament to assess progress in the implementation of this policy, and to identify priorities for future action.

References

[10] Buchanan, A., M. Reed and G. Lidestav (2016), “What’s counted as a reindeer herder? Gender and the adaptive capacity of Sami reindeer herding communities in Sweden”, Ambio, Vol. 45/S3, pp. 352-362, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0834-1.

[11] European Commission (2018), Large Carnivores: Conservation and Environment, 2018, http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/carnivores/index_en.htm (accessed on 04 April 2018).

[6] Hagsgård, M. (2016), Renskötselrätten och de Allmänna Intressena av Samisk Kultur och Renskötsel i Nationalparker och Naturreservat - En Rapport till Naturvårdsverket [Reindeer husbandry and the general interests of Sami culture and reindeer husbandry in National Parks], Rättsutredning, Stockholm, http://www.naturvardsverket.se/upload/miljoarbete-i-samhallet/miljoarbete-i-sverige/uppdelat-efter-omrade/Skydd%20av%20natur/Rapport%20om%20f%c3%b6rh%c3%a5llandet%20mellan%20rensk%c3%b6tselr%c3%a4tten%20och%20f%c3%b6reskriftsr%c3%a4tten,%20Marie%20B.%20Ha (accessed on 27 February 2018).

[3] Henriksen, J. (2008), “The continuous process of recognition and implementation of the Sami people's right to self-determination”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 21/1, pp. 27-40, https://doi.org/10.1080/09557570701828402.

[5] Idre Sameby (2018), Samisk Förvaltning [Sami Administration], 2018, http://www.idresameby.se/index.php?p=f&c=a (accessed on 01 April 2018).

[16] Länsstyrelsen i Norrbottens län och Sweco (2016), Ökad Samverkan Mellan Rennäring och Gruvnäring [Increased collaboration between reindeer herding and mining], Länsstyrelsen i Norrbottens län och Sweco, http://www.lansstyrelsen.se/Norrbotten/Sv/publikationer/2016/Pages/okad-samverkan.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2018).

[9] Larsen, R. (2017), “Impact assessment and indigenous self-determination: A scalar framework of participation options”, Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, pp. 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2017.1390874.

[21] Larsen, R. et al. (2017), “Sami-state collaboration in the governance of cumulative effects assessment: A critical action research approach”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, Vol. 64, pp. 67-76, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EIAR.2017.03.003.

[15] Lawrence, R. and R. Larsen (2017), “The politics of planning: Assessing the impacts of mining on Sami lands”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 38/5, pp. 1164-1180, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1257909.

[14] Lawrence, R. and S. Moritz (2018), “Mining industry perspectives on indigenous rights: Corporate complacency and political uncertainty”, The Extractive Industries and Society, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EXIS.2018.05.008.

[25] Library of Congress (2018), Sweden: Appellate Court Grants Sami Village “Better Right” to Hunting Rights, but Not Control over Them, Global Legal Monitor, https://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/sweden-appellate-court-grants-sami-village-better-right-to-hunting-rights-but-not-control-over-them/ (accessed on 17 September 2018).

[17] Noble, B. et al. (2015), Toward an EA Process that Works for Aboriginal Communities and Developers Advisory Council, https://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/Noble-EAs-Final.pdf (accessed on 05 April 2018).

[18] OECD (2017), Local content policies in mineral-exporting countries, OECD Trade Policy Papers, https://doi.org/10.1787/18166873.

[23] OECD (2017), OECD Territorial Reviews: Sweden 2017: Monitoring Progress in Multi-level Governance and Rural Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268883-en.

[22] Pettersson, F. and H. Frisk (2016), “Soft space regional planning as an approach for integrated transport and land use planning in Sweden – Challenges and ways forward”, Urban, Planning and Transport Research, Vol. 4/1, pp. 64-82, https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2016.1156020.

[19] Reimerson, E. (2016), “Sami space for agency in the management of the Laponia World Heritage site”, Local Environment, Vol. 21/7, pp. 808-826, https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1032230.

[20] Samer (2010), Samiskt Ansvar för Laponia [Sami Responsibility for Laponia], http://www.samer.se/GetDoc?meta_id=3209 (accessed on 03 September 2018).

[2] Sametinget (2018), Budgetunderlag 2018-2020 [Budget 2018-2020], https://www.sametinget.se/116048 (accessed on 26 March 2018).

[1] Sametinget (2018), Näringspolitik [Economic policy], https://www.sametinget.se/1058 (accessed on 28 February 2018).

[24] Sametinget (2018), Reindeer Management Plans, Sametinget, https://www.sametinget.se/118168 (accessed on 06 March 2018).

[7] Sametinget (2015), Sametinget Handlingsplan för Landsbygdsprogrammet [Sami action plan for rural development], https://www.sametinget.se/94731 (accessed on 15 March 2018).