5. India’s pathway to universal electrification

Progress is needed in expanding access to electricity for human and economic development

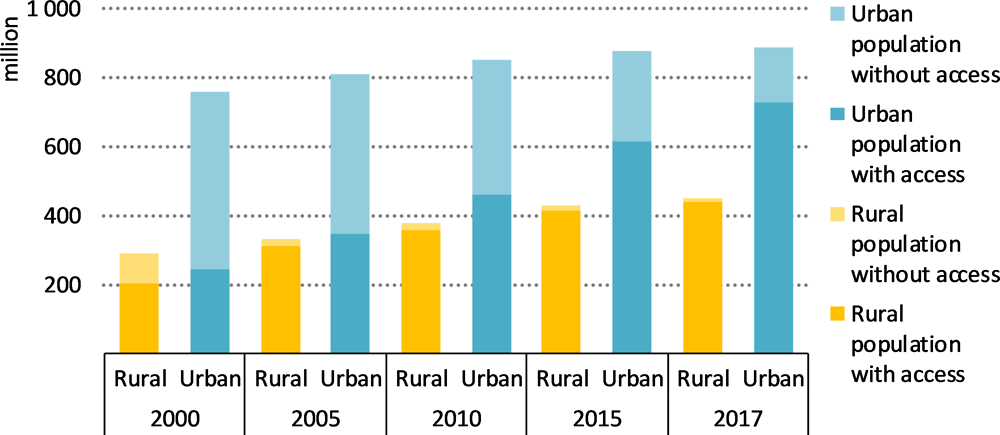

Today, almost 1 billion people live without access to electricity, and close to 2.7 billion people live without access to clean cooking facilities.1 These two modern energy services make up target 7.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services by 2030. Energy has long been recognised as essential for humanity to develop and thrive, but the adoption of SDG 7 by 193 countries in 2015 marked a new level of political recognition. Energy is at the heart of many other SDGs, including those related to gender equality, poverty reduction, improvements in health, and climate change.

Between 2000 and 2017, India achieved unprecedented improvements in electricity access. The national electrification rate progressed from around 40% to 87%, bringing significant social and economic benefits. Electric lighting is replacing candles, kerosene and other polluting fuels, not only saving money (and providing more light) but also seriously improving health. Electricity increases productive hours in households, leading to positive outcomes on education and economic well-being. Reliable electricity also spurs innovation and powers micro-business ventures.

Expanding access to electricity to all villages through co-ordinated government action

Universal household electricity access was a central political commitment in India’s 2014 national elections, and the government aimed to electrify all villages by May 2018, followed by all households by 2022. On 28 April 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India had achieved its goal of providing electricity to every village, and reset the universal household electricity access objective to the end of 2018. This is one of the greatest achievements in the history of energy. Since 2000, around half a billion people have gained access to electricity in India, with political effort over the last five years significantly accelerating progress.

The Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana scheme2 is a prime example of co-ordinated government action. This scheme focused on strengthening and extending distribution networks by co-funding construction with the electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs). In 2015, the government announced the Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana scheme, which allows state governments, who own the DISCOMs, to take over 75% of their debt and pay back lenders by selling bonds. DISCOMs are to repay the remaining 25% through the issuance of bonds, in exchange for improvements in operational targets. Over 99% of people who have gained access in India since 2000 have done so as a result of grid extension. The government has more recently been building mini-grids and stand-alone solar home systems to deliver access to some of the hardest-to-reach homes.

To keep track of progress, the government created an on-line dashboard where real-time information is made available on the advances of village and household electrification. Data is also disaggregated at the state level to encourage healthy competition between jurisdictions.

Political leadership, institutional capacity, and careful planning and monitoring

India’s experience shows the need for committed political leadership, backed by institutions with the capacity and mandate to deliver electrification. This commitment and effort started from the top government representatives, and ultimately involved officials within operators and individual states. Detailed plans for delivering universal electricity access were designed within each state.

Involving numerous actors also requires transparent monitoring and tracking against targets – one cannot manage what one cannot measure. The Indian government’s strong emphasis on this principle was an essential element of the programme’s success. This underlines the importance of the IEA’s commitment to providing such data in a transparent way, as the agency has been doing since 2002.

What next?

Global progress on electricity access remains uneven. India has made historic progress, and China achieved universal electricity access in 2015. Meanwhile, the electrification rate in sub-Saharan Africa has increased to 43% in 2017, but over 600 million people remain without electricity. Looking forward, providing electricity for all by 2030 would require an annual investment of USD 51 billion per year, almost twice the level mobilised under current and planned policies. Electricity for all by 2030 is achievable, and Africa must be at the heart of the process.

To support this goal, collecting and reporting sound data on energy access, which is one of the primary commitments of the IEA, is essential. This allows governments to keep track on progress towards SDG 7.1, and to highlight successes such as the one seen in India. In parallel, improving local capacity to autonomously monitor and track energy access progresses, in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, will support the development of effective and transparent national programmes.

India is also taking its electrification lessons on board as it tackles access to clean cooking facilities. Globally, nearly 2.7 billion people primarily rely on polluting fuels for cooking, resulting in 2.6 million annual premature deaths. While an estimated 675 million people in India still primarily rely on the traditional use of biomass for cooking, progress is emerging, as the government has given free liquid petroleum gas connections to over 50 million households living below the poverty line. It recently increased the ambition of the target from 50 million to 80 million households by 2020.

Reference

[1] International Energy Agency (2018), World Energy Outlook 2018, https://webstore.iea.org/world-energy-outlook-2018.

Notes

← 1. Clean cooking facilities are cooking facilities that are considered safer, more efficient and more environmentally sustainable than the traditional facilities that make use of solid biomass (such as a three-stone fire). This refers primarily to improved solid biomass cookstoves, biogas systems, liquefied petroleum gas stoves, ethanol and solar stoves.”