Chapter 1. Education in Japan: Strengths and challenges

This chapter provides a brief description of Japan’s education system and the context in which it operates. Since the 1990s, the Japanese economy has been sluggish, and the ratio of debt to GDP has reached uncharted territory. The forecast of sharp demographic decline, the rapidly ageing population and the evolution of the skills required to flourish in a knowledge economy also present new challenges to Japan’s economy, society and educational institutions.

Japan’s unique education system relies on the concept of “the whole child” or holistic education, where schools not only develop academic knowledge, but also foster students’ social, emotional and physical development. International standardised assessments highlight the excellence of education and the high level of equity in Japan, but Japanese students exhibit a higher level of anxiety and a lower level of life satisfaction than their counterparts elsewhere in the OECD.

Building on its strengths, Japan has started to reform its education system to adapt to the globalised environment of the 21st century, increase well-being, broaden students’ skills and enhance its contribution to the economy and society.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction and background to the report

The Basic Act on Education specifies that the mission of the Japanese education system is to convey universal principles such as “full development of the personality” and “dignity of the individual.” It also states that the system should “help children to become independent individuals who combine well-balanced knowledge, morality and a healthy body” and will continue to work towards personal fulfilment, while respecting civic responsibility and actively participating in building the state and Japanese society. As such, Japan’s education system not only ensures that children will receive the necessary inputs for self-realisation, but it also helps to bond society by providing basic training ground for good citizenship (Boyle, 1992[1]).

Since the beginning of international standardised assessments of student achievement in the 1990s, Japan has demonstrated the excellence of its education system by regularly being among the top performers. But today’s rapidly changing socio-economic situation is posing new challenges to Japan in terms of academic achievement and civic responsibilities for shaping the future of Japanese society. Globalisation and modernisation have been changing the skills required in the workplace and in everyday life. With a shrinking and ageing population, Japan faces major demographic decline, which has led to significant changes in its industrial and employment structures. Japan’s high standards of equity in education have also been challenged, with widening income and social disparities across the population. Meanwhile, school bullying and student well-being have come into focus.

To respond to these challenges, the Japanese government (elected in 2012) created the Council for the Implementation of Education Rebuilding, a new institution aiming to place education at the centre of the roadmap to growth. Headed by the Prime Minister, the Council brings together experts from a wide variety of fields. It has formulated ten global recommendations, including policy recommendations for development of the Second Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (2013-2017).

In the Second Basic Plan, based on the report prepared by the Central Council for Education (an advisory board to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology - MEXT), the Cabinet set four policy directions for the reform package:

-

Developing social competencies for survival: independence and collaboration in a diversified and rapidly changing society.

-

Developing human resources for a brighter future: initiating and creating changes and new values through leadership in various fields in society.

-

Building safety nets for learning: a wide range of learning opportunities accessible to everyone.

-

Building bonds and establishing vibrant communities: a virtuous circle where society nurtures people and people create society.

These policy directions focus primarily on curriculum reform and school organisation. Other matters, such as lifelong learning and costs of tertiary education, are still under active policy consideration.

Building on the Council’s work and the current Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (2013-17), MEXT has been implementing policies such as increasing financial assistance to households for education, reorganising local education boards and strengthening self-governance in universities.

In 2015, MEXT announced a plan to enhance schools’ capacity by improving teacher quality, introducing specialists, promoting school-community partnerships and revising the National Curriculum Standards to be implemented from fiscal years 2020-22. MEXT and the Central Council of Education, an advisory board to MEXT, have also been discussing transition mechanisms from upper secondary education into university, aiming to transform upper secondary education, the university entrance selection process and university education (called Articulation Reforms).

In this context, the government plans to introduce the third Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (2018-22). Developed by the Central Council of Education, it defines a comprehensive and systematic implementation of education policy in Japan, focused on how the education system can help individuals prepare for 2030.

The Japanese government invited the OECD to conduct an analysis of the strengths and challenges of its education system, focusing on selected policy areas that are part of the third Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education and future education policy. The review’s objectives were to: 1) define practices to improve instruction in schools, including school partnerships with the community; and 2) assess the state of tertiary education and the means to revitalise it (examining the key features and the role of tertiary education and how lifelong learning can contribute to its revitalisation).

The OECD analysis focused on the following items of the Japanese current reform agenda:

-

A National Curriculum Reform (to be implemented from 2020-22), which will focus on using active learning to develop the competencies of students around the three stated pillars: 1) motivation to learn and apply learning to life; 2) acquisition of knowledge and technical skills; and 3) skills to think, make judgements and express oneself. New student assessments aligned with the new curriculum will be developed.

-

An integrated reform of the teacher training system, which includes development of comprehensive training for teachers throughout their career, along with reorganisation in schools to reduce non-teaching tasks for teachers, and continuous development of a school environment favourable to in-service training for teachers (e.g. Lesson Study).

-

Strengthening school-community partnerships, which includes involving communities in children’s education as partners to schools, and implementing a school management reform (the Community School programme and the Team Gakkou [school as a team] programme). Among the objectives of these reforms are: 1) maintaining the holistic approach to children’s education with support from the community; and 2) lightening the workload and responsibilities of teachers and schools, with greater engagement from parents and the community.

-

Ensuring financial support for those in need, which includes reducing the financial burden of education on families, especially at non-mandatory levels of education. Grant-type scholarships for tertiary students and subsidies to low-income families for early childhood education and care (ECEC) have recently been introduced as part of the reforms.

-

Improving access to tertiary education and adult learning, which includes development and promotion of new programmes for adults to foster lifelong learning in an ageing society. Plans to reform university entrance examination procedures have also been discussed.

OECD National Reviews of Education Policy aim to help Japan and other countries to better understand the challenges and potential responses resulting from the need for education systems to evolve as they seek to prepare students for the future, in light of current demographic, economic and social changes, the important contribution of lifelong learning and the impact of education funding structures on equity.

OECD National Reviews of Education Policy can cover a wide range of topics and sub-sectors tailored to the needs of the country. They are based on in-depth analysis of strengths and weaknesses, using various sources of available data, such as PISA, national statistics and research documents. The reviews draw on policy lessons from benchmarking countries and economies, with expert analysis of the key aspects of education policy and practice being investigated.

Reviews include one or more visits to the county by an OECD review team with specific expertise on the topic(s) being investigated (often with one or more international and/or local experts). An OECD Education Policy Review typically takes from eight months to a year, depending on its scope, and consists of six phases: 1) definition of the scope; 2) preparation of a background report by the country; 3) desk review and preliminary visit to the country; 4) main review visit by a team of experts; 5) drafting of the report; and 6) launch of the report.

The methodology aims to provide tailored analysis for effective policy design and implementation. It focuses on supporting specific reforms by tailoring comparative analysis and recommendations to the specific country context and by engaging and developing the capacity of key stakeholders throughout the process.

OECD National Reviews of Education Policy are conducted in OECD member and non-member countries, usually upon request of the country.

For more information:

Using OECD review methodology (Box 1.1), this report is part of the OECD’s efforts to strengthen the capacity for education reform across OECD member countries, partner countries and selected non-member countries and economies. Education Policy in Japan: Building Bridges Towards 2030 draws on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), as well as other comparative data from benchmarking education performers, research and analysis of key aspects of education policy in Japan, and two review visits to Japan. The OECD review team members also made extensive use of OECD’s internfernational knowledge base and Japanese educational research, statistical information and policy documents.

The report identifies the main strengths and challenges of Japan’s education system within the focus area of analysis, and provides a number of recommendations that can contribute to improving Japan’s future education policy design. In particular, to ensure that the current reforms take hold, it is important for Japan to recognise the present well-rounded (holistic) model of education, to build on its strengths, and to prioritise reforms that can help to Japan transition to 21st century skills and further enhance its education performance.

Japan’s socio-economic context

Geography and political system

Japan is an archipelago of 6 852 islands located in the Pacific Ocean, east of the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea, China, Korea and Russia. The country stretches from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Chinese Taipei in the south-west. The four main islands of the archipelago are Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu and Shikoku, which together make up about 97% of Japan's land area.

The world's tenth largest country, Japan has a population of 127 million and is highly homogenous, as Japanese make up 98.5% of the total population. About 73% of Japan is forested, mountainous and unsuitable for agricultural, industrial, or residential use. As a result, the habitable zones, mainly located in coastal areas, have extremely high population densities. Japan is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with 340 people per square kilometre (OECD, 2017[2]). Tokyo, the capital city, has the most populated metropolitan area among OECD countries, with approximately 36 million people.

Japan is a constitutional monarchy, with the role of the Emperor limited to ceremonial duties. Power is held by the Prime Minister, while sovereignty is vested in the Japanese people, who elect members of the Diet, the legislative body of Japan. A bicameral body, the Diet consists of the House of Representatives, in which members are elected by popular vote every four years, and the House of Councillors, in which members are also elected by popular vote but serve six-year terms. Japan has been governed by the Liberal Democratic Party, either alone or as part of a coalition for around 40 years, with other parties in power in 1991-93 and 2009-12.

Japan is a unitary state. The central government delegates many functions to the local governments, but retains the overall right to control them, as provided in the Local Autonomy Law passed on 17 April 1947. Japan is divided into 47 prefectures in 8 regions. Each prefecture is overseen by an elected governor and subdivided into municipalities (1 719 in total). Roles usually fulfilled by prefectures include providing services such as education, public health, social welfare, urban planning, economic development, sanitation and environmental protection, transportation infrastructures and police. As a result, municipalities have significant capacity to decide what services they should prioritise, as long as they respect the parameters set by the central government. In fact, while local government expenditure accounts for 70% of overall government expenditure, the central government still controls local budgets, tax rates, and borrowing.

A sluggish economy

After China and the United States, Japan has the world’s third-largest economy, with gross domestic product (GDP) at USD 4 125 billion (OECD, 2017[2]). It is the world's fourth-largest exporter and importer of goods and also of services (WTO (World Trade Organisation), 2017[3]). However, since the early 1990s, Japan’s GDP per capita has gone down compared to the top half of OECD countries – to 81% of their level (Figure 1.1a). In 2015, Japan’s GDP per capita was USD 38 400, below the OECD average of USD 40 800 (OECD, 2017[2]).

Japan’s economy is concentrated on services, which amount to 72% of the total GDP, while industry contributes 27% of the total value added and the agricultural sector contributes 1%. Because it lacks natural resources to support its growing economy and large population, Japan has had to specialise in the export of goods where it has a comparative advantage, such as engineering-oriented, or R&D-led industrial products, in exchange for the import of raw materials and petroleum. Japan is among the top three importers of agricultural products in the world by volume (along with the European Union and the United States) to provide for its own domestic agricultural consumption (OECD/FAO, 2007[5]).

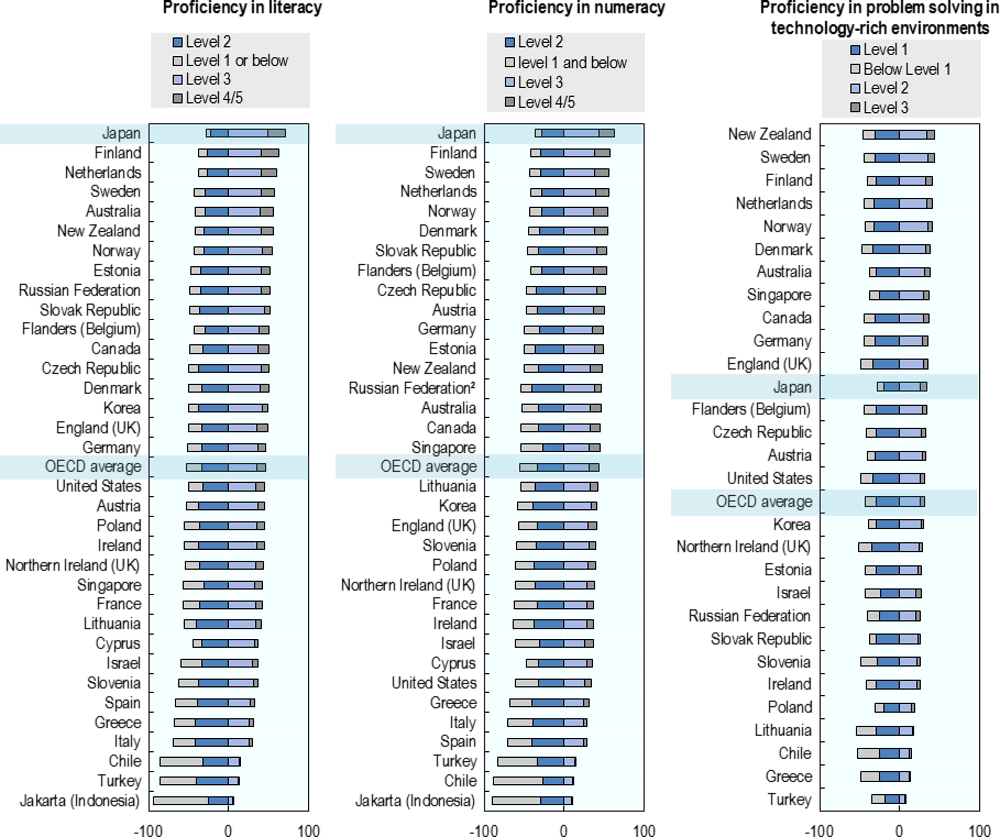

The Japanese labour market is tight.1 Japan’s ratio of job offers per applicant rose to 1.51 in June 2017, the highest since 1974 (Japan Macro Advisors, 2017[6]). Total employment as a share of the population aged 15-74 in Japan (68%) is one of the highest among all OECD countries, and the OECD projects even further increases in the employment rate during 2017. Correspondingly, the overall unemployment rate in Japan has fallen to 3.3% and the youth unemployment rate to 5.6%, among the lowest in the OECD (OECD, 2016[7]). Moreover, data from the OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) rank Japanese workers as the most proficient in numeracy and literacy in the world.

There may be room to improve resource allocation. Workers in Japan may be overqualified, since 31% of them state that they hold a qualification level above what is required for their job (compared to the OECD average of 21.7%). Estimates of the difference in wages between overqualified workers and their well-matched counterparts also show that they earn 19% less (compared to the OECD average of 14.5% less) (OECD, 2016[8]).

Despite high economic performance, Japan has had a sluggish economy for more than 20 years. At the start of the 1990s, the Japanese asset price bubble burst, throwing the Japanese economy into turmoil. The economic recovery that ensued did not restore Japan’s prosperity. The subprime crisis in 2008 triggered a recession, with a growth rate of -5.5% in Japan in 2009, causing Japan to sink even deeper into what is now called the “lost decades”. Japan’s GDP per capita, which almost matched the level of the top half of OECD countries in 1990, is now 19% below that (Figure 1.1a).

During that period, persistent deflation increased the debt ratio, while chronic deficits were maintaining this effect. Today, the gross debt stands at 216% of GDP (Figure 1.1b), and the public debt service is now the biggest item in the Japanese budget (24.3%). This leaves little leeway for government policy action. In response, the government launched a package of reforms to stimulate the economy, including monetary easing to tackle the liquidity trap, fiscal stimulus to boost consumption and policies to spur private investment and revive growth.

This background has contributed to rising inequalities, linked to the development of a dual labour market after the price asset bubble crisis. As declining growth shifted the Japanese lifetime employment model, labour law reforms gave firms incentives to explore alternative forms of human resources practices (Aoyagi and Ganelli, 2013[9]). Since the early 1990s, a rise in the share of non-regular workers (refers usually to workers who do not enjoy employment security: short-term contract, part-time work or indirect employment) in the workforce has fuelled the increase in inequality in income, strengthened the dualism of the labour market (regular versus non-regular workers), generated a working-poor population, and potentially leveraged the poverty rate (Jones, 2007[10]).

The share of non-regular workers rose from below 20% in the 1990s to almost 40% in 2017. Moreover, the share of the population living under the poverty threshold (i.e. with a disposable income of half of the national median), rose by 4 percentage points between 1985 and 2012 to reach 16%, which was in the second highest decile among OECD member countries (OECD, 2017[2]). In 2011, the richest 10% of the population in Japan earned 10.7 times as much as the poorest 10% (compared to the OECD average ratio of 9.5). These results highlight that a segment of the population in Japan is fragile and facing the risk of poverty. Unemployed people, part-time workers, homeless people and single-parent households, in particular single mothers, are especially at risk (Sekine, 2008[11]).

Rapidly ageing population

The demography of Japan is intertwined with the economic issues the country is facing. Japan’s population peaked in 2010, at just over 128 million, before beginning what is projected to be a sustained and increasingly steep decline to reach less than 100 million in 2050 (Figure 1.2). At the same time, the low fertility rate and the highest life expectancy among OECD countries have led to a progressive ageing of the population, with the share of the elderly rising from 5% in 1955 (one of the lowest percentages among OECD countries) to the highest in 2014, with more than 25% of the population who have retired (OECD, 2017[12]). A shrinking labour force undermines Japan’s growth potential and might slow its progress towards higher standards of living. Moreover, ageing of the population has induced the growth of public spending, fuelling deficits that are to some extent responsible for the high level of debt.

The rapid ageing of the Japanese population is a direct challenge to the economy. One way to target this is to invest in family-friendly or welfare policies that support increased births or immigration. While foreign-born individuals as a percentage of the total population reached an average of 13% across OECD countries by 2015, the proportion in Japan was less than 2% (among the smallest across the OECD) (OECD, 2017[13]). Permanent migration to Japan relative to the total population represented 0.06% in 2015, below the OECD average of 0.71% (Figure 1.3). In PISA 2015, only 0.2% of 15-year-old students in Japan have an immigrant background, compared to 5% of students across OECD countries (OECD, 2016[14]).

A cohesive society

Japan is a relatively homogenous society. The Japanese ideal has traditionally been embodied in the unity of people, language, and culture (Weiner, 2009[15]). More recently, Japan has started to consider diversity more openly. For instance, ethnic clubs in schools have begun to open to encourage pupils with different backgrounds to “maintain and nurture their ethnic identity” (Creighton, 2014[16]).

Feudalism and neo-Confucianism left a legacy of a highly stratified and ordered society in Japan. The hierarchical caste system (in decreasing importance: samurai, farmers, craftsmen and merchants) was formally established at the start of the Edo period (1603) and disappeared with the Meiji restoration (1869). While Japan was progressively opening to the world, the Meiji government established a bilateral system of education to compete with western countries (mandatory primary education for the masses, and secondary and tertiary education for the elite). Since then, the number of schools, enrolments and the length of studies have continued to grow. In the 1960s, when many farmers’ sons obtained upper secondary and college degrees and enjoyed upward mobility into white-collar jobs, their educational credentials became an indicator of a lifetime achievement and of a new social status. The historical vertical differentiation of society inherited from the Edo period has been progressively replaced by a “credential society” (gakureki shakai), in which upper secondary schools and universities are academically stratified, and graduation from a particular institution is a measure of academic achievement conferring prestige and social ranking. (Ishikida, 2005[17]).

The concept of social peace and group identity is pervasive in Japanese education and society in general. The socialisation process in Japanese primary schools mimics the distinctive features of Japanese law, government and management (Rohlen, 1989[18]). Teachers develop group behaviour among pupils, without exerting strong authority. As in civil society, authority tries to shift responsibility downward to lower-level groups. This results in a great sense of order within the group, and prepares children for group participation and bonding, which are required in the Japanese society at every level. Some experts have suggested that the Japanese concepts of attachment and group behaviour as part of social order could explain why Japan is a more ordered society than China or South Korea, for instance, which share the same Confucianist roots (Hechter and Kanazawa, 1993[19]).

Education governance and curriculum

Trickle-down policy-making process

The Basic Act on Education (revised in December 2006), stipulates that the government shall formulate a basic plan (Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education) to comprehensively and systematically advance policies to promote education. It also specifies that local governments shall also endeavour to formulate a basic plan suited to their local circumstances by referring to the national Basic Plan.2

The government mandates the Central Council for Education to prepare the Basic Plan. A special Committee is formed for that purpose. The plan has to be ultimately validated by the Cabinet of Japan, the executive branch of the Government of Japan, composed of the prime minister and other ministers. The first Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education 2008-12 was endorsed by the Cabinet in 2008.

The Council for the Implementation of Education Rebuilding was created after the election of Shinzō Abe in 2012. The Central Council drafted the Second Plan for 2013-17, taking into account some recommendations formulated by the Council, and it was endorsed by the Cabinet in 2013 (Figure 1.4). This OECD review has been undertaken in parallel to discussions for the development of the third Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education 2018-22.

According to the Basic Act on Education, the national government comprehensively formulates and implements educational measures to provide equal opportunities in education and to maintain and increase educational standards. In general, the Basic Plan first assesses the current status of education in Japan and the challenges facing the education system. It then offers different policy directions and diverse measures to be implemented for each of them. For instance, in the Second Plan, one of the measures to achieve the policy direction “developing social competencies for survival” was the “improvement of the educational content and methods to cultivate solid academic abilities”. There is also provision for unexpected circumstances. For example, the Second Plan details exceptional measures for “recovery and reconstruction assistance for the Great East Japan Earthquake”.

The Act requires local governments (47 prefectures and their respective municipalities) to formulate and implement educational measures corresponding to their regional context. Among the main bodies that help shape national education policies:

-

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Science and Technology (MEXT) regulates the education system from ECEC (kindergartens only) to upper secondary education levels (e.g. setting National Curriculum Standards, defining teacher certification programmes and official requirements for setting up schools). The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare is in charge of ECEC (day-care centres) and vocational education and training.

-

The Central Council for Education, composed of education experts and representatives from various stakeholder groups (e.g. parents and representatives from different fields, such as economy, sports, culture and media), prepares reports on educational issues at the request of the Minister of Education.

-

MEXT is responsible for tertiary education. It regulates the standards for establishing universities. Public and private universities are required to conduct self-evaluations and undergo accreditation processes by evaluation and accreditation organisations certified by MEXT at least every seven years (at least every five years for professional graduate schools).

Overall, the national government has to maintain and improve the level of national education by presenting strategic objectives as national standards, formulating the framework of the education systems, and maintaining the infrastructure. At the local level, governments are expected to take action respecting the national guidelines in order to deliver education. Figure 1.5 shows the hierarchy of the different local institutions. For instance, the prefectures and municipalities endorse important responsibilities in terms of policy and delivery of education at the local level:

-

The 47 prefectures are in charge of upper secondary education and responsible for the handling of teaching materials. The prefecture governor is responsible for the education budget and private education from ECEC to upper secondary education.

-

The 1 719 municipalities are responsible for mandatory (school-level) education. A board of education in each municipality is in charge of establishing and managing public mandatory schools. The mayor of the municipality is responsible for the education budget.

-

Both boards of education from prefectures and municipalities can help schools understand and comply with the National Curriculum Standards by providing additional material. Boards of Education set rules concerning basic school administration and evaluate schools. To do so, they send supervisors to schools (usually former school leaders), who are expected to provide external guidance on school management, curriculum and teaching.

-

Other education stakeholders include teacher unions, the juku3 institutions and civil society.

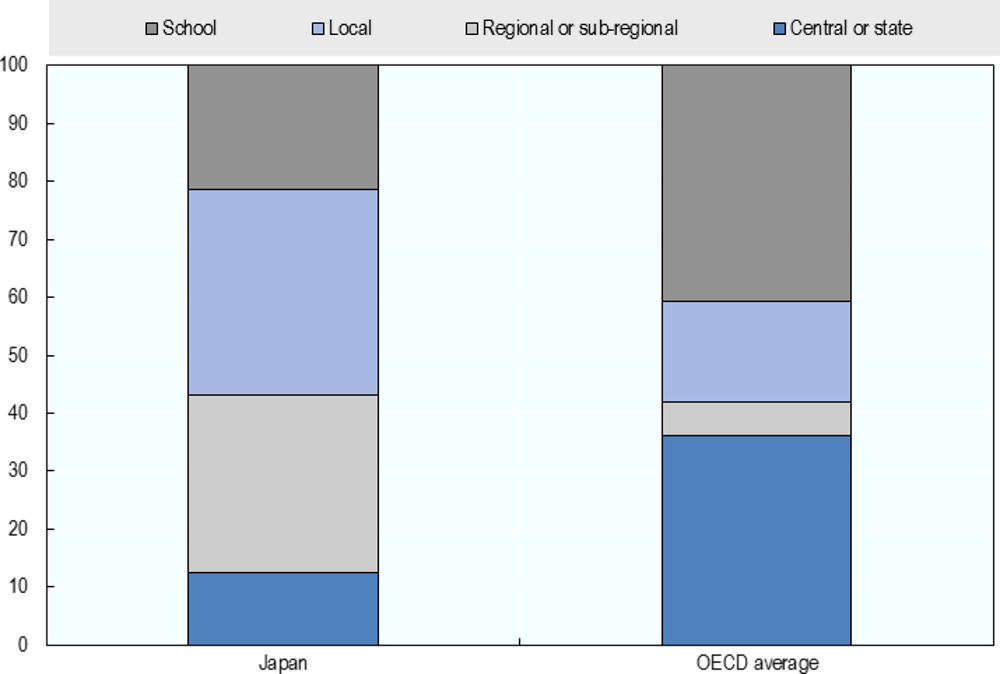

Prefectures and municipalities make most education decisions on school management and allocation of teachers to schools. In Japan, 66% of decisions are taken at the local or regional level, compared to the OECD average of 23% (Figure 1.6).

The population of Japanese municipalities is spread out, with many villages and towns located in rural areas and on small islands. These rural municipalities sometimes do not have sufficient financial resources to hire teachers and may struggle to attract them to their schools (OECD, 2015[22]). In such cases, the national law transfers the authority for teacher affairs in mandatory education from smaller municipalities to prefectures (through the prefectural boards) or to cities designated by government ordinance (cities large enough to exert the role of a small prefecture).

Prefectural boards of education have the authority to recruit and train teachers, and to allocate them to schools based on municipalities’ reports and principals’ opinions. The boards of education in each municipality supervise issues related to everyday delivery of teacher public services. The share of decisions taken at prefecture level in public lower secondary education in Japan is 31%, well above the OECD average of 5%. Prefectures take 65% of decisions in resource management and 58% of decisions in personnel management (compared to the OECD average of 8% for both).

In tertiary education, decision-making is shared between the government and the tertiary education institutions. MEXT regulates the standards for establishing universities and sets six-year mid-term objectives for each of the national university corporations, which then set their mid-term plans based on these objectives. MEXT also certifies accreditation organisations. Public and private universities are required to conduct self-evaluations and undergo evaluation by those accreditation organisations at least every seven years (OECD, 2015[22]). Overall, MEXT’s position is that it should retain its authority over certain aspects of operations of national universities (such as defining the student enrolment cap and level of fees and controlling any major academic reorganisations at department or programme level) on the grounds that they are run with public funds and play important public roles (Newby et al., 2009[24]).

An education system that is centralised in some ways, but decentralised where it matters

As stated in a previous report (OECD, 2012[21]), the Japanese education system is not as centralised as it seems at first. The government authority (MEXT) is responsible for developing and implementing national education policy, distributing public resources for education at the national, prefectural, and municipal levels, and guiding national curriculum standards, textbook development, and teacher training. At the regional level, each of the country’s 47 prefectures has its own board of education responsible for co-ordinating education in its geographic area, according to its Local Basic Plan for Education (Figure 1.4).

Prefectural boards of education are mainly in charge of regulating the number of institutions: they have the power to establish and close schools. They also certify teachers, control the quality of teaching and are in charge of offering support measures necessary for implementing projects in cities and towns and for the appropriate operational management of the facilities (providing instruction, advice and aids, dispatching supervisors to the municipal schools, etc.).

At the municipal level, each of the approximately 1 700 municipalities in Japan has its own board of education responsible for selecting school textbooks. However, school principals also seem to participate in this selection to some extent (Table 1.1). The way the curriculum is taught rests almost exclusively with teachers, who also have authority over instruction and actual classroom practice.

According to PISA data, Japan can be characterised as providing below-average school and local autonomy in decisions relating to resource allocation (Figure 1.7). In contrast, Japan grants significant autonomy to schools in curriculum and assessment policies. This reflects the way in which education governance is structured in Japan: the central government largely guides financing; prefectures largely guide teacher selection and evaluation; municipalities have authority over textbooks; schools set general student assessment approaches; and teachers have significant freedom to innovate in classroom practice.

This distribution of roles might be one factor leading to Japanese academic success. PISA results suggest that school autonomy in content is more closely related to educational performance than responsibility for making decisions concerning resource allocation. For example, school systems like Japan’s, that provide schools with greater discretion in making decisions on student-assessment policies, courses offered, course content and textbooks used (Table 1.1), tend to perform at higher levels in PISA (OECD, 2012[21]; OECD, 2016[26]). Further evidence also shows that while autonomy in content makes a difference, this depends on the capacity and quality of those working in schools to be able to use such autonomy effectively (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2014[27]).

Curriculum revised every ten years

MEXT determines the National Curriculum Standards, a broad set of standards for all schools from kindergarten to upper secondary schools. The National Curriculum Standards provide curriculum guidelines and structure education programmes to ensure that they comply with a fixed standard of education throughout the country. The National Curriculum Standards have generally been revised once every ten years or so since 1951.

At the beginning of the 2000s, the revision of the National Curriculum Standards imposed a large reduction of learning content, full implementation of a five-day school week (reduced from six days) and the introduction of the period for integrated studies, all in an attempt to reinforce a more “relaxed education” (yutori kyōiku) policy. The subsequent revision of the National Curriculum Standards, announced in 2008 and implemented from 2009 to 2011, was developed in response to the argument that the implementation of “relaxed education” had contributed to a decline of academic standards, as shown by tests run by the Mathematical Society of Japan in top Japanese universities and at the primary and lower secondary level, and later by 2003 PISA results (NIER (National Institute for Educational Policy Research), 2011[28]).

The latest revision of the National Curriculum Standards was discussed by the Central Council for Education starting in 2014, and the National Curriculum Standards for primary and lower secondary school were announced in March 2017. They are to take effect progressively: in April 2020 in primary school, in April 2021 in lower secondary school, and in 2022 in upper secondary school. The new National Curriculum Standards will introduce school curriculum management and enhanced use of active learning (defined as proactive, interactive and authentic learning). It will also aim to develop “curriculum open to society” by fostering students’ competencies relevant to society and promoting partnerships between schools and communities.

The objectives defined for the revision of the National Curriculum Standards are:

-

to nurture competencies needed to live independently in the rapidly changing and unpredictable future society and to participate in shaping a society (a “curriculum open to society”),

-

to improve the quality of understanding and nurture academic competencies, while maintaining the framework and educational content of the current National Curriculum Standards,

-

to nurture richness of mind and sound body through enhancement of moral education, experiential learning and physical education.

The revision of the National Curriculum Standards, as of March 2017, will follow four main directions:

-

Adhering to the objectives set out above.

-

Improving lessons through proactive, interactive and authentic learning: This type of pedagogical approach should be generalised to improve the quality of the learning process, to achieve high-quality understanding and develop the qualities and abilities of all students.

-

Curriculum management by each school: Each school will manage its curriculum to improve the quality of educational activities and maximise the effect of learning, by determining educational content, allocating time adequately, securing necessary human and physical resources, etc.

-

Educational content for primary and lower secondary education: The new National Curriculum Standards will enhance Japanese language learning, information and communication technologies (ICT) learning, mathematics and science education, education on Japanese tradition and culture, experiential learning activities and foreign language education, moral education and education for students with special educational needs. “Foreign language activities” will be introduced as a mandatory subject in the third and fourth grades in primary education.

Japan’s education system

Structure of the school system

In Japan, three different kinds of institutions offer pre-mandatory education: kindergartens, nursery schools, and centres for ECEC. Kindergartens, the core component of Japanese early education, accept any child from age three to age six (the age of primary school admission). Nursery schools provide day care for children from zero to six years old, while centres for ECEC have the characteristics of both kindergartens and nursery schools. Around 96% of four-year-olds were enrolled in pre-primary education in Japan in 2014 (OECD, 2016[29]).

School education in Japan is designed as a comprehensive single-track school system based on the US model. Japanese students attend primary school (shōgakkō) for six years before attending lower secondary school (chūgakkō). This mandatory education is free of charge, open to all local residents and contributes to the social fabric of the community. Most important, the Japanese hold strong beliefs concerning children’s ability to learn. Every student is expected to succeed, subject to the right amount of effort, perseverance and self-discipline. By teaching these behavioural habits early, primary school education is seen in Japan as fundamental in shaping a positive attitude toward lifelong education (Dolan and Worden, 1992[30]). Table 1.2 gives details of the composition of pre-primary, primary and secondary education.

The Ordinance for Enforcement of the School Education Law stipulates the annual standard school hours for each subject (this is also specified in the National Curriculum Standards), while the organisation of the teaching time is decided in each school. In primary and lower secondary education, the set of subjects taught in schools is uniform across Japan. The organisation of the class is detailed in Table 1.3 and Table 1.4. Along traditional subjects such as Japanese or Arithmetic, the Period for Integrated Studies’ aims to enable students to think in their own way about life through cross-disciplinary studies and inquiry studies. Students are expected to acquire the abilities to learn and think on their own, to make proactive decisions, and to solve problems. The uniform organisation of education at primary and lower secondary levels embodies the Japanese notion of equal opportunity of education.

After three years at lower secondary school, students attend upper secondary school (kōtōgakkō) for another three years. Although this stage is not mandatory, 97% of the population graduates from upper secondary (the third highest rate among OECD countries) (OECD, 2016[29]) and thus qualify to access tertiary education (Figure 1.8).

In upper secondary education, students need 74 or more credits in order to graduate. Only 31 credits should come from compulsory subjects, which are the following:

-

Integrated Japanese language

-

Either world history A or world history B

-

One subject out of Japanese history A, Japanese history B, geography A and geography B

-

Contemporary society, or ethics, politics and economy

-

Mathematics I

-

Science and our daily life, and one subject out of basic physics, basic chemistry, basic biology and basic earth science or three subjects out of basic physics, basic chemistry, basic biology and basic earth science

-

Physical education and health

-

One subject out of music I, art and design I, crafts production I and calligraphy I

-

English communication I

-

One subject out of basic home economics, integrated home economics and design for living

-

One subject out of information study for participating community and information study by scientific approach

The remaining of credits is obtained by studying elective courses included in fields such as Japanese Language, Civics, Mathematics, Science, Art or Foreign Language. Since the proportion of time spent on compulsory subjects is around 30%, there is room in upper secondary education for students to stand out (Nakayasu, 2016[31]).

In Japan, the different kinds of tertiary education institutions are highly stratified, and each plays a well-defined role. Strictly speaking, only universities and junior colleges provide post-secondary education, but other institutions complete the picture:

-

Universities aim to develop students’ academic knowledge as well as specialised skills based on scientific research. Entrance to public universities is determined by a standardised national test (the National Centre for University Entrance Examination) and special examinations administered by the individual universities. The university track follows a classic scheme: bachelor’s degree (four years), master’s degree (two years) and doctorate (three to five years).

-

Junior colleges provide mainly professionally oriented short-cycle degrees. They offer a two-year specialisation programme in fields such as education (childcare, pre-primary school teaching), home economics, gardening or nursing (three years). Junior college students were usually female, as the sector tended to cater to their traditional role in society. However, these institutions are now declining, because the number of female students entering universities has increased significantly, while the overall number of students has been falling due to demographic trends. There were 6 000 students in junior colleges in 2015, compared to 23 000 in 1995 (MEXT, 2016[20]).

-

Colleges of technology offer both theoretical and practical training in skills of immediate use to employers, mostly in the field of engineering. Lower secondary graduates can apply to this five-year programme, while upper secondary graduates can enter it directly in the fourth year. Successful students are considered to be practical technicians with an “Associate” credential.

-

Specialised (or professional) training colleges offer one-year to three-year employment-related programmes at either upper-secondary or post-secondary level to meet immediate workforce needs.

-

Junior colleges and colleges of technology deliver an associate degree. Specialised training colleges deliver a diploma in two to three years, or an advanced diploma in four years. All three of these institutions deliver diplomas at the ISCED 5 level.

School management: distributed leadership

In Japan, as in most OECD countries, school leaders are experienced former teachers who have met some additional training requirements. Teachers wanting to become a school leader have to enter a Professional Graduate School in Education to build on their applied knowledge and develop a theoretical background. This graduate school delivers a master’s degree in teaching to become a “School Leader (mid-career core teaching staff)”. School leaders are then expected to master leadership theories and exhibit practical and applied skills needed to fulfil their leadership role in the school as well as bringing local communities closer.

There have been changes in the career structure of teachers in Japan (Box 1.2). Since the revision of the School Education Act in 2007, three new positions have been introduced to promote effective school administration: senior vice-principal, senior teacher and advanced skills teacher. A narrow definition of school leaders includes only upper-level management (school principal, senior vice-principals and vice-principals), while broader definitions also include mid-level leaders, such as senior teachers and head teachers (Yamamoto, Enomoto and Yamaguchi, 2016[33]).

The roles of senior teacher, advanced skills teacher and senior vice-principal are optional in school. The senior vice-principal is part of management and accessing this position requires passing an examination at the prefecture level (Box 1.2). As the senior teacher will undertake tasks close to management, some examination at the prefecture level is also required to become a senior teacher. Advanced skilled teachers and senior teachers are selected by the prefectural Board of Education after recommendations from the Board of Education of the city, town, or village (in case of ordinance-designated cities, they are directly selected by the Board of Education of the cities themselves).

The Boards of Education (BOEs) of prefectures and ordinance-designated cities are responsible for hiring teachers to work in schools in their jurisdiction. Teachers are employed by the BOE and assigned to teach in schools in its jurisdiction. They are typically transferred to different schools every few years.

New teachers usually start their teaching career as homeroom teachers and/or as subject teachers in specialised area(s). After they have gained more classroom teaching experience, those teachers take on the role of chief teacher of a grade, responsible for managing a group of teachers. They are then promoted to senior teachers, who work to support principals and (senior) vice principals. After this stage, teachers must pass the managerial class examinations in order to be promoted to head teacher, (senior) vice-principal and principal. Some teachers are also transferred to BOEs to become teacher supervisors, who advise schools and co-ordinate training for teachers and school leaders.

Source: MEXT (2016[20]), OECD-Japan Education Policy Review: Country Background Report.

Boards of education usually allocate senior teachers and senior vice-principals to school with difficulties or a large number of students, and advanced skilled teachers to school with young teaching staff. The senior vice-principal supports the principal in the effective operations of the school. Both the senior teacher and the advanced skilled teacher teaches students, but the senior teacher also supports the principal in the effective running of the school, while the advanced skilled teacher advises other teachers and staff in order to improve education guidance for students.

Leadership in-service training is provided through several different options:

-

At the local level: Since local boards of education are responsible for educational training, the ministry has provided since 2003 a sample of training for school leaders focused on organisational management that has been distributed to local boards of education and other interested parties (Yamamoto, Enomoto and Yamaguchi, 2016[33]).

-

At the national level:

-

The National Centre for Teachers’ Development (NCTD) provides national training programmes for leaders at different levels. Leadership programmes focus on school administration training and training for future trainers on school organisational management (National Center for Teachers' Development, 2015[34]). The school administration training programmes are designed for specific positions and experiences, such as principal, vice-principal and mid-level teachers.

-

The NCTD, in co-operation with MEXT, also provides training programmes for selected school leaders nominated by the BOEs of local governments, who are expected to play a central role in their region (National Center for Teachers' Development, 2015[34]; Yamamoto, Enomoto and Yamaguchi, 2016[33]).

-

Given this management-oriented training, and the strong engagement of teachers and collaborative practices, the role of principals in Japan is more of an administrative nature, focusing on determining schedules, managing teachers and other functions that may be required to support teaching and learning practices by teachers. Teachers work together collectively on classroom issues, and school leaders adopt a supportive role on organisational issues. This distributed approach to leadership means that the individual principal does not exercise the main pedagogical role in schools, as it is a collective distributed task among teachers. Therefore school leaders in Japan do not appear high in international comparisons of instructional leadership indicators.

Data from PISA 2015 shows that Japanese school principals scored below the OECD average in the index of instructional and curriculum leadership (OECD, 2016[26]). As set out in the Basic Act on Education and the School Education Law, at the national level, the government specifies the goals to achieve and formulates the National Curriculum Standards that schools refer to while developing their curriculum.

Leadership in schools in Japan is spread across different leadership administrators and teachers, who have the freedom to develop their own curriculum according to the government’s directives (Pont, Nusche and Moorman, 2008[35]). Effective practices are discussed during design of the curriculum, and school leaders, as former teachers, can play an active role. However, this role appears to be limited, as shown by data from PISA and the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS). In both PISA and TALIS, Japan scored among the lowest in related indicators. The index of engagement in instructional leadership in lower secondary education by principals was lower than the TALIS average (OECD, 2014[36]).

But principals do provide feedback to teachers. About 75% of Japanese teachers reported receiving feedback from their school leader (above the TALIS average of 54%). School leaders in Japan are more likely than the OECD average to make decisions about student retention or promotion and to make judgements about teachers’ effectiveness (OECD, 2015[22]). Despite their former careers in teaching, school leaders in Japan focus on ensuring effective organisational management, such as the proper functioning of the school, while teachers are in charge of instructional and pedagogical issues.

Vertical and horizontal stratification in secondary education

In contrast to differentiated school systems, such as those in Austria and Germany which stream their students into separate tracks as early as age 10, Japan has a comprehensive school system and sorts students into different programs at age 15 when they are entering Grade 10 (compared to the OECD average of 14.3 years old). Vertical stratification is defined as the extent to which students of a similar age are enrolled at different grade levels. In PISA, 100% of 15-year-old students from Japan are enrolled in Grade 10 (as in Iceland and Norway). This makes vertical stratification non-existent in these countries, with no grade repetition by students (OECD, 2013[25]).

Conversely, a highly vertically-differentiated school system tackles heterogeneity among students. Vertical differentiation occurs when applicants to schools agree upon the level of quality for each institution, resulting in a clearly established hierarchy of educational institutions. Upper secondary schools in Japan are ranked predominantly by the prestige they gain based on the percentage of their students who enter top universities after passing the difficult entrance examinations. To maintain the rank of their institution, upper secondary schools organise their own entrance examinations and rely more than other OECD countries on screening applicants. For instance, the “percentage of students in schools whose principals reported that students’ records of academic performance (including placement tests) are always considered for admittance” is 92.3% in Japan, the highest rate among OECD countries (OECD, 2013[25]).

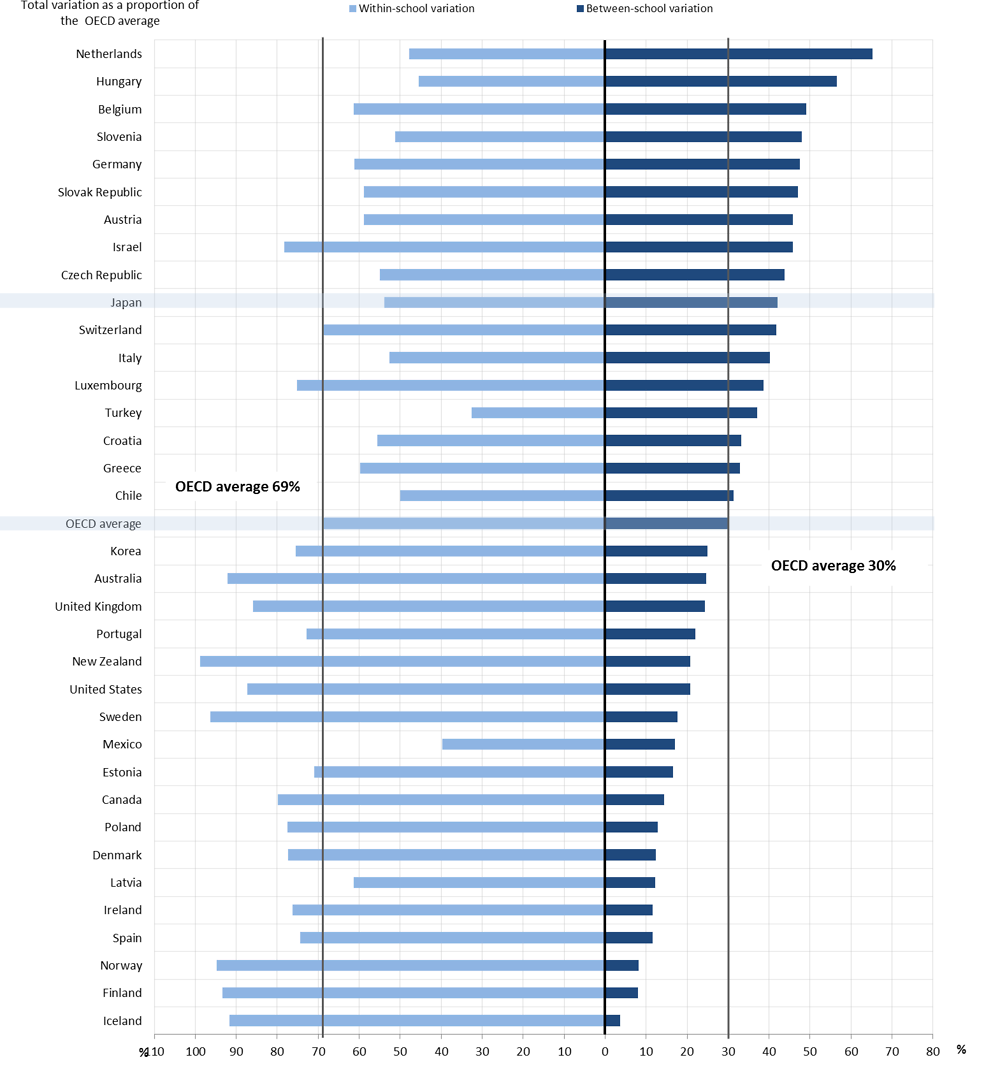

The direct consequence of vertical differentiation is reduced variation within schools and increased variation between schools. Japan exhibits significant variation in student performance: 42% between-school variation (above the OECD average) and 54% within-school variation (below the OECD average) (Figure 1.9). Therefore, the index of academic inclusion5 across schools for Japan is 56, 14 points below the OECD average (an index of 100 indicates that all schools are performing the same even if their students perform differently) (OECD, 2016[14]).

Within schools, the heterogeneity level of students is tackled with a mild ability-group learning strategy, which amounts to horizontal stratification. In Japan, the “percentage of students in schools where students are grouped by ability into different classes” is 10.1% for “all subjects” (compared to the OECD average of 7.8%) and 43.5% “for some subjects” (compared to the OECD average of 38%) (OECD, 2016[26]).

High student performance that comes at a cost

While already having demonstrated educational success, Japan has embarked on a major reform of the education system, revolving around a reform of the school curriculum. This ambitious plan aims to encompass policy measures to adapt teaching and learning to the competencies required for the 21st century. By doing so, Japan could also improve in lower-performing dimensions, such as students’ ability to think critically and student well-being.

Strong academic achievement and equity, with some limitations in the ICT environment

Japanese students are among the highest performers in PISA across OECD countries. With an average score of 538 points in science in PISA 2015, students in Japan are outperformed only by students in Singapore (556 points), and they perform similarly to students in Estonia and Chinese Taipei (Figure 1.10). Japanese students’ average reading score (516 points) is comparable with that of students in Germany and Korea, but students in Canada, Finland, Hong Kong (China) and Singapore outperform Japanese students in reading by 10 score points or more. Japanese students attain the same mathematics score (532 points, on average) as students in Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong (China) and Korea, but they are outperformed by students in Hong Kong (China), Macao (China), Singapore and Chinese Taipei (OECD, 2016[14]).

Across most countries, socio-economically disadvantaged students not only score lower, they also have lower levels of engagement, drive, motivation and self-belief. Japan, along with Canada, Estonia and Finland, achieves high levels of performance and equity in education outcomes as assessed in PISA 2015, with 10% or less of the variation in student performance attributed to differences in students’ socio-economic status (Figure 1.10). Across OECD countries, 13% of the variation is attributable to socio-economic status. Moreover, some 29% of disadvantaged students (those in the bottom quarter of the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status in each country) across OECD countries are “resilient”, meaning that they manage to perform better than expected on the basis of socio-economic status and perform among the top 25% of students around the world. In Japan, the percentage of resilient students has grown by 8 percentage points since 2006, so that nearly one in two disadvantaged students (49%) is considered resilient.

Similarly, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) demonstrates high performance. Among 49 surveyed countries, Japan ranks in the first decile in mathematics and science in Grades 4 and 8. Trends in these two fields are rising, with an increase in Grade 4, for instance, from 567 points in 1995 to 593 points in 2015 in mathematics, and from 553 to 569 in science (Mullis et al., 2016[37]).

In the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), as noted earlier, adults in Japan demonstrated the highest levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy among adults in all countries participating in the survey. Japan also had by far the smallest share of adults scoring at Level 1 or below in both proficiency domains (Figure 1.11).

In contrast, PIAAC results show that 21% of adults in Japan had no computer experience or failed the ICT core assessment (compared to the OECD average of 14.2%), meaning that they lacked the most elementary computer skills. This share rises with age, showing that the older population is even less familiar with ICT (21.2% for the 45-54 age group, 40.9% for 55-64 year-olds, the fourth-highest among participating countries).

The younger group (those aged 16-24), is more proficient in computer literacy than their elders, but still lags behind other countries, since 12.1% of them failed the ICT core test or had no computer experience (4.3% in average in OECD countries). Moreover, the share of Japanese 16-24 year-olds proficient at higher levels (Levels 2 and 3) is 5 percentage points below the OECD average and 17.5 percentage points behind the top performer, Korea (OECD, 2013[38]).

Japan also struggles with the effect of its university entrance exams on the whole education system. Since accessing top universities in Japan not only makes students more likely to win a secure job on graduation but also heightens social recognition, students are under pressure to win entrance to those universities. As reported in The Economist (1997[39]), this high-stakes exam has led the education system to focus on “rote learning” and “teaching to the test”, while incentivising students to attend academic jukus (after school courses). The Council of Education noted in a report back in May 1997 that cramming hours were stifling creativity and critical thinking.

During the review visit, the OECD team had several discussions with stakeholders on the issue of developing specific dimensions of cognitive skills such as critical thinking. TALIS data show that around 16% of teachers in Japan reported feeling capable of helping their students to think critically (compared to the TALIS average of 80%) (OECD, 2014[36]). Data from the Survey of Adult Skills also show that while younger Japanese (16-24 year-olds) displayed higher levels of proficiency than their older compatriots in problem-solving, their performance was lower than in relation other countries (OECD, 2013[38]).

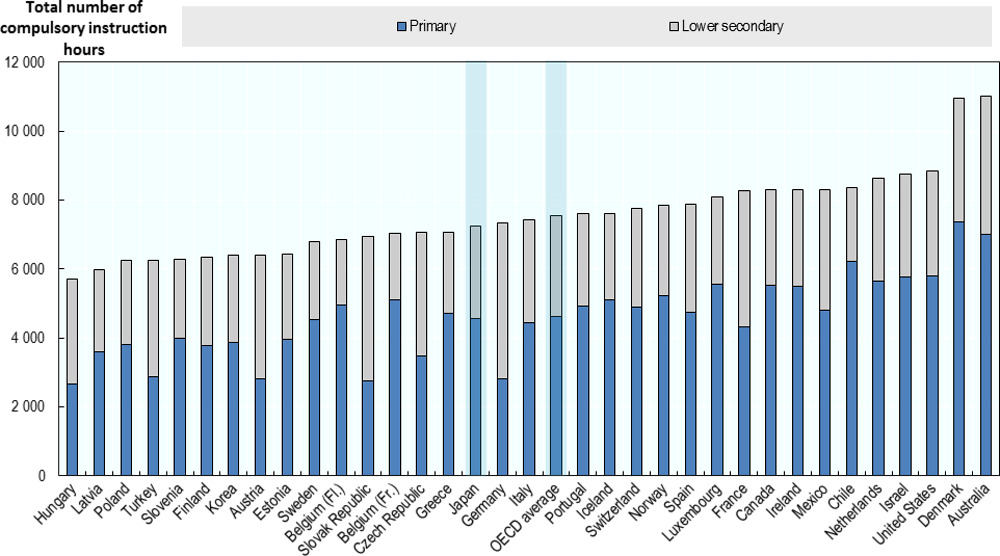

Mandatory learning time in school

Students in Japan are currently expected to receive a total of 7 260 hours of instruction during their mandatory primary and lower secondary education. This is slightly less than the OECD average of 7 540 hours (Figure 1.12).

During the last revision of the curriculum (in 2011 for primary and in 2012 for lower secondary education), the intended number of hours of schooling in Japan has increased, particularly compared to the early 2000s (Figure 1.13). In the 1990s, concerns about the system's strong focus on examinations and disciplinary problems in schools (including widespread bullying) prompted moves to encourage greater individual creativity, and the so-called “relaxed education” (yutori kyoiku) reform was introduced in the early 2000s. The reform included cutting the school curriculum content by 30% and reducing the school week from six days to five. The goal was to increase students’ experiences outside schools in order to improve their social competencies, for example during activities in nature and society. As a result, the number of study hours was significantly reduced.

Around the same time, the PISA 2003 reading test shifted the emphasis from reproduction of subject content to solving problems in new contexts. Between 2000 and 2003, the overall performance of Japanese students on PISA dropped from 522 points to 498 points, causing what has been called “PISA shock”. This sparked a national debate on education policy, especially on the effectiveness of the 2002 revision of the National Curriculum Standards, which had significantly reduced the curriculum content and lesson hours in primary and lower secondary education.

After 2004, the “relaxed education” was adjusted to take account of successive PISA results and public reaction to the earlier reforms, with new measures to that ensure students get solid grounding in basic knowledge. The revised national curriculum announced in 2008 and 2009 aimed to balance the building of a solid knowledge base with nurturing of students’ skills to think, make judgements and express themselves. Primary school textbooks have been expanded by almost a quarter and lesson times lengthened by one or two hours per week in primary and lower secondary schools to cover the longer curriculum (Figure 1.13).

Pervasive shadow education

Japanese students attend a slightly lower number of mandatory schooling hours than the average in OECD countries. However, according to PISA 2012, 70% of 15-year-olds reported attending after-school lessons in mathematics (along with 58% in Japanese and 54% in science). This share of after-school mathematics was the highest among OECD countries and is significantly higher than the OECD average of 38%. In particular, socio-economically advantaged students are more likely to attend after-school lessons in mathematics (83%) than disadvantaged students (55%). The difference between the two groups in Japan is also among the largest across OECD, along with Korea and Greece (OECD, 2013[25]).

A survey organised by MEXT shows that more than half (around 60% depending on the year) of students in their last year of lower secondary school attend jukus, as most students at this level prepare for entrance examinations to upper secondary schools (MEXT, 2016[42]). In fact, the closer students get to university entrance examinations, the more likely they are to attend jukus. In a report on children’s educational activity outside of schools, MEXT showed that the share of students attending jukus increases steadily, from 16% in the first year of primary school to 65% in the last year of lower secondary education, while the share of students engaged in extra activities drops from around 70% in primary school to around 30% in lower secondary education (MEXT, 2008[43]). During the fiscal year 2016, surveyed Japanese households reported spending JPY 246 000 on supplementary learning for lower secondary in public schools and JPY 195 000 in private schools (MEXT, 2016[44]).

Juku attendance started escalating in the 1970s, when a steep increase in the educational aspirations of the Japanese population was not matched by the level of education supplied by the government. Because the number of candidates far exceeded the available places, parents turned to private providers offering educational support, the juku industry (private after-hours tutoring schools). According to a detailed literature review (Entrich, 2015[45]), there is a strong popular belief in Japan that investment in shadow education (out-of-school private tutoring) leads to a tertiary education level and access to high-ranking institutions. This led to academic research, which established that investing in shadow education fosters educational inequalities (Seiyama, 1981[46]; Seiyama and Noguchi, 1984[47]; Konakayama and Matsui, 2008[48]). However, Japanese schools appear to deliver equitable results (Figure 1.11), since students’ socio-economic status explains only 10% of the variation in science performance, below the OECD average of 13% (OECD, 2016[14]).

In Japan, standardised exams that determine entrance to upper secondary school or university signal the social status of a family. Families’ investments in jukus therefore peak in Grade 9 the last year of lower secondary, when students prepare entrance examinations to access selective upper secondary schools, which are seen as potential gateways to top universities (MEXT, 2016[49]). Further evidence indicates that shadow education is also pervasive at other levels in education.

To access university, students must go through “examination hell”, where the intensity of the competition is crystallised by the saying “four pass, five fail”, meaning that students who sleep four hours a night should succeed, but those who sleep five hours will likely fail (Stevenson and Baker, 1992[50]). A majority of students in upper secondary school also take extra classes at jukus to prepare for the all-important university entrance examinations (Clark, 2005[51]). Although the competition for access to upper secondary school and university is believed to have decreased lately, due to low birth rates, attendance at jukus is not declining (MEXT, 2016[49]).

Lower levels of student well-being and higher level of anxiety

In the Japan Times, Kyodo (2015[52]) echoes a report from the Cabinet Office stating that youngsters have a higher propensity to commit suicide when they are due to go back to school after a long vacation, around the end of spring and summer holidays. The highly competitive school environment, the repeated standardised tests (the “exam race”) and bullying (see below) may generate high levels of stress for students. The cost of the academic success of Japan may lie in a lower level of child well-being.

In Japan, 61% of students feel satisfied with their life, 10 percentage points below the OECD average, according to 2015 PISA data. While Japanese students perform the highest in science, their average life satisfaction index is significantly below the OECD average (Figure 1.14).

Japanese students also report school-work-related anxiety in the highest quartile of an index that measures anxiety, while their index of achievement motivation is the second lowest among OECD countries. The students’ sense of belonging at school is around the OECD average (OECD, 2017[53]). There is a positive correlation across education systems between the index of school-work anxiety and the index of achievement motivation (Figure 1.15). However, Japan appears as an outlier on this representation, since Japanese students combine high levels of anxiety with low levels of motivation.

Japan presents a below-average index of exposure to bullying in PISA 2015, although 22% of student reported being bullied at least a few times a month (above the OECD average of 18.7%). The fact that, in Japan, students interviewed for PISA are in upper secondary (rather than lower secondary) could play a role in the relatively low ranking of Japan among other countries in terms of bullying. According to a MEXT survey, the number of reported cases of bullying at primary, lower and upper secondary schools rose to 225 132 in academic year 2015, from 188 072 cases in the previous year (an increase of 20%) (MEXT, 2017[54]). These results do not necessarily highlight an upward trend but may be the result of a new law introduced in 2013, by which schools are legally compelled to detect bullying early and take measures to prevent it (Act for the Promotion of Measures to Prevent Bullying).

In PISA 2012, students in Japan reported lower confidence about their ability to solve a set of pure and applied mathematics problems than the average across OECD countries, although they have shown improvement since 2003. Japanese students reported less pleasure and interest in learning mathematics, less openness to problem-solving and more anxiety in learning mathematics than the OECD average, even if their pleasure and interest in learning mathematics have increased over time (OECD, 2014[55]).

Compared to 2006, fewer Japanese students in 2015 reported that they enjoy learning science, but more students reported that learning science is useful for their future plans. Students in Japan reported almost the same level of motivation to learn science as the OECD average. And while Japanese students in 2015 reported a greater sense of self-efficacy in science than their counterparts in 2006, they are still below the OECD average in this respect (OECD, 2016[14]).

According to TIMSS, Japanese students from Grades 4 and 8 are among the three countries whose students least like learning mathematics (with Korea and Chinese Taipei in Grade 4, and with Korea and Slovenia in Grade 8). Japanese students in Grade 4 are slightly below the OECD average in terms of appreciating learning science, but they once again rank last when reaching Grade 8 (with Korea and Chinese Taipei).

A report published by MEXT in 2011 reveals that Japanese upper secondary education students have markedly lower self-esteem and self-confidence than students in America and in other Asian countries. On standard questions such as: “Do you value yourself as a person”, only 36.1% of students answered “Agree” or “Somewhat agree”, compared to 89.1% in the United States, 87.7% in China and 75.1% in South Korea. Similarly, only 15.4% of students in Japan “believe they are a capable person”, while 84.5% of students do so in the United States, as do 67% in China and 46.8% in South Korea (MEXT, 2011[56]).

Schools as learning environments

Part of the success of Japanese students stems from the holistic approach of education in schools. Parents’ engagement with and bonds to communities make school life rich and diverse for students and contribute to the completeness of the curriculum. Moreover, the evaluation and assessment process of school performance drives schools to improve constantly and guarantees an environment especially conducive to learning.

The unique Japanese model of holistic education

The Japanese model revolves around the concept of “whole child education” (cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development of students), where other systems might focus only on two or three dimensions of child development. To achieve this, the Japanese curriculum is infused with Tokkatsu, a concept encompassing non-cognitive aspects of education that aims to develop emotional intelligence. In particular, Tokkatsu are educational activities in which the school and classrooms are considered as “societies”. Through group activities, independent and practical attitudes are cultivated in children to enable them to build better group life and to develop personally. Key principles behind Tokkatsu include encouraging child-initiated activities, self-motivation, collaborative learning and learning by doing.

During their visit, the OECD review team observed that teaching in Japan is not limited to academic content, but also tackles a broad range of activities. For instance, teachers supervise students as they clean the school, help serve school lunch or engage in extracurricular activities. They also supervise field trips and excursions, and engage with the parents by initiating discussions and organising visits at their home. Primary school teachers may teach the same group of students for 2 or more years, and teachers from lower secondary are responsible for a homeroom class that remains together until high-school entrance. Repeated and diverse interactions develop trust between teachers and students, in contrast to systems where teachers focus on teaching activities only. Schools in Japan are thus the breeding ground for social and emotional development and provide students with initial training to become good citizens.

Parental involvement in education in Japan strengthens the school’s influence. Compared to their OECD counterparts Japanese parents particularly stand out in two areas: discussing their child’s progress on the initiative of a teacher and discussing their child’s behaviour on the initiative of a teacher (Figure 1.16). For instance, the homeroom teacher establishes relationships with students’ parents, which facilitates open lines of communication about the student’s academic progress. According to Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1995[57]): “In most circumstances, parental involvement is most characterised as a powerful enabling and enhancing variable in children’s education success, rather than as either a necessary or a sufficient condition in itself for that success. Its absence eliminates opportunities for the enhancement of children’s education; its presence creates those opportunities.” The excellent school-home communication established by Japanese teachers incentivises parents to support the teacher’s position at home and contributes to Japanese education success.

Teachers in Japan: A highly productive but fragile population

The teaching profession in Japan is highly competitive, especially outside large cities, which helps drive the quality and status of the profession. To start teaching, teachers in Japan must comply with several prerequisites (see Box 1.3). First, candidates to initial teacher education (ITE) must perform well in the national university examination, and there are often additional criteria for those entering ITE through faculties of education.

Initial teacher education in Japan, which is similar to programmes offered in other countries in terms of selection criteria, duration and content, generally lasts four years. This includes a short mandatory teaching practicum, though the duration of teaching practicum is often longer for candidate teachers in faculties of education.

After completing ITE, teacher candidates must apply to their local boards of education, which issue teaching certificates, then pass multiple-stage competitive employment examinations to be eligible for a permanent teaching position in a public school. When entering the profession, they follow a 1-year formal induction programmes while engaging in teaching and other educational activities (OECD, 2015[22]).

The Lesson Study, a widespread method in primary school in Japan, used in particular in mathematics lessons, incites teachers to work together to identify specific teaching issues, spread good practices and update their knowledge. Usually, teachers work together to prepare a specific lesson on a topic where students have struggled, and nurture their reflexion with leading-edge academic literature. Then, one teacher teaches the lesson to students, while other teachers (sometimes even from other schools) observe and learn the new pedagogical approach.

Professional development in Japan tends to both extend and renew teachers’ practice, skills and beliefs. The Lesson Study not only improves teaching practices over time, but also strengthens co-operation between teachers and potentially fosters the development of an inter-school network of teachers. In addition, in 2009, Japan introduced the Teaching Certificate Renewal License. Under this system, teachers must renew their teaching certificates by participating in at least 30 hours of professional development programmes every 10 years to improve their knowledge and practices.

Japanese teachers have among the highest total statutory working time in OECD countries, with 1 891 hours per year from pre-primary to upper secondary (compared to OECD averages around of 1 615 hours depending on the education level) (OECD, 2017[58]). Their work covers a wide variety of school activities, including eight hours for extracurricular activities per week, well above the TALIS average of two hours (OECD, 2014[36]). Despite this heavy load, teachers’ salaries in Japan are only around the average of OECD countries. For instance, a starting secondary teacher in Japan earns USD 3 000 less annually than the OECD average, but USD 4 000 more when he/she reaches 15 years of experience (Figure 1.17).

Teachers in Japan are largely responsible for how the curriculum is taught and have authority over instruction and classroom practice (OECD, 2012[21]). However, they report lower-than-average levels of self-efficacy in some domains. Around 16% of teachers in Japan reported feeling capable of helping their students to think critically (compared to the TALIS average of 80%) (OECD, 2014[36]). In addition, about one-quarter (24%) of Japanese teachers reported that they do not feel prepared to teach the content, pedagogy and practical components of the subjects they teach (above the TALIS average of 7%).

They also report more often than their counterparts in other countries that work schedule conflicts were a barrier to participation in professional development activities (86.4%, compared to the TALIS average of 50.6%). Only 28% of teachers in Japan believe that the teaching profession is valued in society (compared to the TALIS average of 31%), and 58% of Japanese teachers would choose to work as teachers if they could decide again (compared to the TALIS average of 78%) (OECD, 2014[36]).

Universities and university departments with teacher preparation programmes/courses provide pre-service training for candidates for the teaching profession. In order to become candidates, individuals need to pass entrance examinations and be enrolled as students at universities with teacher-preparation programmes. Candidates who seek to become teachers need to complete all required teacher-preparation courses and a practicum, in addition to an associate or a bachelor’s degree.

In Japan, ITE is provided by universities through the “Open System” - this means universities can provide ITE if they meet certain requirements, even if they do not specialise in teacher education - or by departments of education in universities, which specialise in ITE. As of 2014, 228 universities and departments (52 national universities, 4 public universities, and 172 private universities) have been approved to offer ITE programmes for primary school teachers, and 520 (70 national universities, 41 public universities and 409 private universities) have been approved for lower secondary teachers.