Chapter 3. Infrastructure, financial development and natural resources in Ukraine

Given the state budget constraints and substantial investments required to modernise and expand existing infrastructure capacity, more private sector participation is necessary. However, despite a modernisation of Public Private Partnership (PPP) legislation in 2015, the use of PPPs is at an early stage in Ukraine. Among infrastructure sectors, electricity is the most advanced in regulatory reform, with full-scale liberalisation of the market scheduled in 2017. Significant private (foreign and domestic) investments in the sector are expected as major power plants are slated for privatisations. The banking sector is going through an unprecedented consolidation (54 banks, accounting for one fifth of banking assets, were classified as insolvent since January 2014). Remaining banks are being recapitalised and the regulatory framework is being strengthened.

Sound infrastructure development policies ensure that scarce resources are channelled to the most promising projects and address bottlenecks that limit private investment. Ukraine’s infrastructure, especially in transport, has been deteriorating following a long period of underinvestment and insufficient maintenance. High freight railway and port tariffs and the lack of reliability of transport services have seriously handicapped private sector development, especially for export-oriented firms. Ukraine has one of the lowest road network densities in Europe and a large part of the existing road network is obsolete and does not comply with European standards. The country also does not have adequate warehousing and storage facilities, which is partly due to the difficulties to acquire land and construction permits.

Little progress with regard to concessions, but reform ongoing

The Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine defines infrastructure concessions as contractual arrangements through which a private entity obtains the right from a government agency to provide a service under market conditions, using a public-sector asset. The arrangement allows asset ownership to remain in public hands, while the private operator is taking responsibility for new investments in addition to operation and maintenance.

Various governments have regarded concessions as one of the most attractive ways to implement large-scale, long-term infrastructure projects. For instance, Build-Operate-Transfer1 (BOT) agreements can be a valuable tool for modernising or extending transport infrastructure. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) can be a way to attract much-needed investment into local utilities (usually owned and managed by local governments and municipalities). However, the use of PPPs is at an early stage in Ukraine. As mentioned in Chaper 3 (Measures reported for transparency, section Concessions), the legislative framework refers to multiple legislative acts, including the 1999 Law On Concession2 and the 2010 Law On Public-Private Partnership.3

Nevertheless, sector-specific legislation exists. It includes the Motorway Concession Law,4 the Law On the Peculiarities of Concessions in the Energy Sector,5 the Law On the Peculiarities of Concessions of Municipal Property in Heating, Water collection and Distribution,6 and various regulations and ministerial resolutions. These multiple normative acts are contradictory in specific cases. In addition, under the PPP Law, the preparation of PPPs involves several different bodies since various decisions and approvals of responsible authorities at the local or state level are required. Because of this complexity, the existing PPP-type projects refer to the less-restrictive 1999 Law On Concession rather than to the framework of the 2010 PPP Law (International Finance Corporation, 2015). However, few international investors have translated a general interest in Ukrainian infrastructure into concrete actions (one exception is the German Port logistics group HHLA, see below section on “Transport and communications”).

The Parliament adopted a reform of the regulatory framework of PPPs in November 2015.7 This legislation substantially amends the previous PPP framework. Its aim is to simplify the procedures during PPP implementation,8 strengthen guarantees granted to private investors and modernise the PPP framework in line with international standards. Several provisions might make Ukrainian PPPs more attractive to foreign investors, such as the possibility to resort to international arbitration in case of PPP-related disputes, or the simplified foreign exchange regime for PPP participants. Other planned improvements to the PPP framework include amendments to the Budget code in order to introduce a mechanism of long-term budgetary commitments under PPP agreements and a revision of the methodology to calibrate concession payments drawing on international experience.

PPPs are long-term undertakings whose successful implementation greatly depends on the government’s success in improving the overall business climate and reducing legal, institutional and policy uncertainty. The development of PPPs is also sensitive to the regulation of specific sectors: for instance, in the field of local utilities, the development of PPPs relies on assurances at the national level about the direction of tariff policies, since the National Commission for State Regulation of Energy and Utilities (rather than local PPP partners, such as subnational governments) regulates tariffs. Moreover, successful PPPs involving subnational governments would require considerable capacity building (OECD, 2014).

The 2013 OECD Territorial review of Ukraine (OECD, 2014) identified specific steps that the authorities can take to foster the development of effective forms of PPPs:

-

Strengthen the dedicated PPP unit under the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. Such units exist in most OECD countries to ensure that the skills needed to handle third party-provision of public goods and services are clustered together within the government. The unit typically provides policy guidance, technical support and capacity-building. Given the need for capacity-building at the subnational level, programmes to train local and regional officials in PPP-relevant subjects (project finance, appraisal methodologies, etc.) could be established.

-

All national, regional and municipal PPP projects – including those in the planning phase – should be made as transparent as possible. A database of PPP projects should be maintained and be publicly accessible over the internet.

-

The review advises caution in rolling out PPP projects. At first, pilot projects should be undertaken and evaluated. Given the lack of practical PPP experience, it suggests to focus on projects where technical and other risks are relatively well understood, such as basic infrastructure.

PPPs are complex instruments, which require a number of capacities to be present in government. These involve setting up a robust system of assessing value for money using a prudent public sector comparator and transparent and consistent guidelines regarding non-quantifiable elements in the value for money judgement. The public authorities must also be able to classify, measure, and allocate risk to the party best able to manage it and to adhere to sound accounting and budgeting practices.

The starting point for assessing the desirability of a PPP is the public sector comparator, a comparison of the net present cost of bids for the PPP project against the most efficient form of delivery according to a traditionally procured public-sector reference project. The comparator takes into account the risks that are transferable to a probable private party, and those risks that will be retained by the government. Thus, the public sector comparator serves as a hypothetical risk-adjusted cost of public delivery of the project. The risk here is of manipulation in favour of PPPs, not least because much depends on the discount rate chosen or on the value attributed to a risk transferred. The evaluation, moreover, encompasses qualitative aspects that involve an element of judgement on the part of government. The question is what the government judges to be an optimal combination of quantity, quality, features and price (i.e. cost), expected (sometimes, but not always, calculated) over the whole of the project’s lifetime. It ultimately depends, then, on a combination of factors working together, such as risk transfer, output-based specifications, performance measurement and incentives, competition in and for the market, private sector management expertise and the benefits for end users and society as a whole.

The second challenge is risk management. To ensure that the private partner operates efficiently and in the public interest, a sufficient, but also appropriate, amount of risk needs to be transferred. In principle, risk should be carried by the party best able to manage it. In this context, “best” means the party able to manage the risk at least cost. This may mean the party best able to prevent a risk from materialising (ex ante risk management) or the party best able to deal with the results of realised risk (ex post risk management). However, not all risks can be managed and cases may exist where one or more parties to a contract are unable to manage a risk. To those parties, such unmanageable risks are exogenous risks (an example is uninsurable force majeure risk that affects all parties, while political and taxation risk is exogenous to the private party and endogenous to government).

The third key issue is affordability. A project is affordable if government expenditure associated with a project (whether or not it is a PPP) can be accommodated within the intertemporal budget constraint of the government. A PPP can make a project affordable if it results in increased efficiency that causes a project that did not fit into an intertemporal budget constraint of the government under traditional public procurement to do so with a PPP. It can be tempting to ignore the affordability issue where PPPs are off budget, but this is very unwise. Using PPPs also reduces spending flexibility, and thus potentially allocative efficiency, as spending is locked in for a number of years. Given that capital spending in national budgets are often accounted for as expenditure only when the investment outlay actually occurs, taking the PPP route allows a government to initiate the same amount of investments in one year while recording less expenditure for that same year. However, the obligation to pay over time will increase expenditures in the future, reducing the scope for new investment in coming years. Government spending might also be affected if the government provides implicit or explicit guarantees to the PPP project and thus incurs contingent liabilities. The system of government budgeting and accounting should provide a clear, transparent and true record of all PPP activities in such a way that there is no incentive take the PPP route based on its accounting treatment.

In some cases, PPPs may be used to circumvent spending ceilings and fiscal rules. There are those that argue that this need not be a problem and that PPPs should be used to invest in times of fiscal restraint. The fiscal constraint argument for public-private partnerships is driven by pressures for governments to reduce public spending to meet political, legislated and/or treaty mandated fiscal targets. In parallel with this, many governments face an infrastructure deficit stemming from a variety of factors including a perceived bias against budgeting for capital expenditures in cash-based budgetary systems. However, when responding to fiscal constraints, governments should not ignore efficiency and affordability considerations. PPPs may also create future fiscal consequences if they violate the budgetary principle of unity, i.e. that all revenues and expenditures should be included in the budget at the same time. Potential projects should be compared against other competing projects and not considered in isolation to avoid giving priority to the consideration and approval of lower value projects.

Source: OECD (2014), OECD Territorial Reviews: Ukraine 2013, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204836-en.

Attracting investment in infrastructure is one of Ukraine’s key priorities but there are still legislative and other regulatory constraints on private sector participation

The State program document “Ukraine 2020: Strategy for national modernisation” identifies investment in infrastructure as one of the main policy directions of the Ukraine government. The issue is nevertheless complicated by the fact that infrastructure is often state-owned and requires substantial public investment. The authorities recognise that given budgetary constraints in the public sector, large-scale private sector participation is necessary to modernise and expand existing infrastructure capacity. The government is committed to address legislative and regulatory bottlenecks in the area of infrastructure concessions.

At the same time, from 2016 onwards the government will introduce a new mechanism to select and assess public investment projects. An interdepartmental commission (composed of government representatives and MPs from the Parliament’s budget committee) will be in charge of selecting public investment projects. For the first time in Ukraine, this mechanism will provide for an ex ante economic assessment of public investment projects based on cost benefit analysis and monitoring of the implementation of these projects. Depending on actual implementation, such mechanism may improve the selection of public investment projects in infrastructure.

Electricity generation, transmission and distribution

The electricity system suffers from various fragilities, including outdated thermal production facilities (only utilising 38% of their capacities), poor transmission lines, dependence on coal and nuclear (that contribute more than 80% of the total electricity generation of around 180 TWh), and few funds for maintenance and improvements. Despite receiving some of the highest subsidies in Europe, the share of renewable energy plants (below 10 MW) is currently at around 7% of total generation. The stagnation is due to several legislative barriers, such as a problematic local content requirement, a restrictive definition of biomass and unbalanced tariffs for various types of renewables, etc.9

Ukraine was the first country of the former Soviet Union to undergo extensive electricity sector reforms back in the mid-1990s: the government privatised some thermal generation and distribution companies in 1995, followed in 1999 and 2002 by the sale of controlling (50%) and blocking (25%) shareholdings in the Ukrainian energy distribution companies to private investors through open tenders.10 This allowed the creation of the largest private energy holding of Ukraine DTEK,11 a vertically integrated holding that controls several regional thermal electricity generation companies. In May 2015, several power plants and equity stakes in major electricity producers, including one of the largest thermal electricity producer Centrenergo, were slated for privatisation.12

A great deal of investment will be required for the electricity sector to support robust national economic growth going forward – but policy uncertainty and low tariffs for households (cross-subsidised by high industrial tariffs) threaten this goal. Investment in energy projects with private participation in 2010-12 equalled USD 1 811 million, compared with USD 16 827 million in Turkey.13

The 2013 Electricity Market Law has been designed to further liberalise markets, creating the conditions for bilateral contracts and wholesale exchanges that would allow customers to choose their suppliers.14 Different markets would operate depending on the customers (bilateral “over-the-counter” contracts, “day-ahead spot”, the balancing market, the ancillary services market, and the retail market).15 Before the full-scale liberalised electricity market becomes operational (on 1 July 2017), the electricity market will operate as the existing “Single Buyer” market, retail market and ancillary services market.

The success of the transition hinges on establishing and/or reorganising the entities that would be in charge of developing and implementing mechanisms for launching the market, such as the Market Operator, System Operator, Cost Imbalance Allocation Fund and others; and achieving legal and organisational unbundling (separation) of distribution activities from activities related to production, transmission and supply of electricity. No attempt was made, however, to create real, workable competition: the five large thermal generation companies created by the original reforms all remain either state-owned or controlled by the private holding DTEK, and the electricity generating companies using nuclear and hydroelectric technologies, respectively Energoatom and Ukrhydroenergo, are state-owned.16 Moreover, the law prohibits any privatisation of nuclear and hydropower power plants.17 Energoatom (which accounts for half of overall electricity production) and Ukrhydroenergo are on the list of strategic enterprises under Ukrainian government control18 (“State assets of strategic importance for the economy and national security”).

The National Commission for State Regulation of Energy and Utilities (NCSREU) was instituted in August 2014 following the dissolution of the National Commission of Ukraine for Electric Energy Regulation and the National Commission of Ukraine for State Regulation of Utility Services. NCSREU is an independent state collegial body that reports to Parliament and is controlled by the President. In addition to the powers of the two previously existing agencies, NCSREU gained new ones regarding implementation of interim emergency measures.19

Natural gas

Despite its untapped conventional and unconventional gas resources, Ukraine has experienced stagnating production in recent years.20 While the International Energy Agency considers that the country has potential to meet its gas consumption with domestic production by 2030 (IEA, 2012), dependency on Russian imports remains a heavy burden. The so-called “winter package” signed on 30 October 2014 ensured that Ukraine could purchase natural gas from Russia.21

Upon becoming a member of the European Energy Community, Ukraine undertook to unbundle transport, production and sale of energy resources. Under new legislation voted in April 2015, state gas conglomerate Naftogaz will be unbundled into separate production, transit, storage, and supply businesses.22 The Law provides free access to the Ukrainian gas transport system by any eligible party, secures non-discriminatory access to the gas market by all gas producers including biogas and gas from biomass, and allows gas consumers freedom of suppliers’ choice. Small distribution system operators which have less than 100 000 consumers will be exempt from the unbundling requirements. The law also allows open market access for traders. Various changes to the current feed-in tariff regime were made in mid-2015.23

The trunk pipeline transport system (Ukrtransgaz), a key conduit for Russian gas supplies to European markets, is excluded from privatisation.24 According to a report prepared by Ukrtransgaz analysts based on publicly available data, during 1996-2014 the Ukrainian gas transport system experienced 7.77 times fewer major disruptions per 1 000 km than the Russian one.25 In line with the Joint Declaration of March 2009 between the Ukraine, the EU, EIB, EBRD and World Bank, the EIB and EBRD signed in December 2014 the first two loans of EUR 150 million each for the upgrading of the main East-West pipeline. As regards to energy security, new interconnection points in the Slovak Republic and Poland have been operational since 2014, thus providing crucial additional supplies to Ukraine in addition to gas from Russia.

Transport and communications

Transport infrastructure is an additional bottleneck for improving aggregate productivity and regional competitiveness. The network consists of 22 thousand km of railways; 170 thousand km of roads; 2.2 thousand km of inland waterways; 13 seaports, four fishing ports and 11 river terminals; 21 airports (of which two state and 14 communal). The 2012 UEFA European Championship, which was co-hosted by Poland and Ukraine, triggered reconstruction works at Kyiv and Lviv airports, while new ones were built from scratch in Donetsk and Kharkiv. Nonetheless, according to the World Economic Forum 2015/16 Global Competitiveness Index, whereas Ukraine is ranked 54st out of 140 economies for electricity and telephone infrastructure, it is ranked 91th in its sub-index for transport infrastructure.

The World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index is a benchmarking tool in the area of trade logistics that allows for comparisons across 160 countries. Based on quantitative data and feedbacks from operators around the world, it demonstrates comparative performance (on a scale from 1 to 5) on six key dimensions of trade logistics.26 According to the index database, Ukraine’s overall rank has improved from 102nd in 2010 to 61st in 2014, an impressive gain in just four years. Ukraine has improved substantially in several key areas of logistics necessary for trade, including in the ease of arranging competitively priced shipments, competence and quality of logistics services such as transport operators, and the ability to track and trace consignments (Figure 3.1).

Source: World Bank, Logistics Performance Index database (International LPI), 2014, http://lpi.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2015).

However, as visible on Figure 3.1, infrastructure and customs are the lowest-scoring components of Ukraine’s Logistics Performance Index. This suggests that investments in the maintenance and extension of transport infrastructure would substantially improve trade logistics. Similarly, an improvement of the efficiency and transparency of the State Customs service could positively affect trade logistics. Along this line, the government is preparing a reform of the State Customs Service, including a pilot project to delegate the management of certain regional customs departments to foreign companies specialised in customs management. On 4 November 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament also adopted a simplification of export-import procedures that should decrease the regulatory burden on businesses involved in international trade.27

The country’s reliance on agriculture and heavy industry translates into far more transport movements and volumes relative to its GDP than any other country in Europe (World Bank, 2014). This implies that transport costs make up a much larger part of the final price of many goods. Less than 10% of freight traffic (in ton kilometres) is by road, while rail and pipelines account almost equally for most freight volume. However, this is changing quickly. Due to steadily increasing commercial and passenger traffic, some strategic sections of the road network are functioning at peak capacities. Yet, substantial portions of the network need upgrading to European technical and safety standards, such as intersection improvements, road markings, and pedestrian facilities. Ukraine’s road safety record remains one of the worst in Europe in terms of road accidents and fatalities (above 20 traffic deaths per year per 100 000 people, compared to less than five in most EU countries).

Pursuant to the Plan on Priority Measures for European Integration of Ukraine, the Transport Strategy was approved in 2010.28 It aims at enhancing economic and social development through efficient (minimum cost), effective (maximum benefit) and sustainable (minimum environmental impact) transport; supporting balanced regional development; facilitating European integration; and enhancing the transit capacity of Ukraine. Proposed priority areas included rationalisation and rehabilitation of existing transport infrastructure; enhancement of Ukraine’s participation in Pan-European corridors; clarifying public service obligations; ensuring inter-modal competition; and institutional coordination to guarantee traffic safety, reliability and environmental protection. The Transport Strategy is now the key strategic document regulating the development of the transport industry until 2020. It sets out long- and medium-term perspectives, key challenges, objectives, principles and priorities of the development of the transport system of Ukraine with due consideration of the needs and interests of the economy and society.

The government reckons that 97% of roads are in poor condition.29 The State Road Agency of Ukraine (Ukravtodor) has been reformed and is pursuing public-private partnerships and concessions in order to quicken the development of modern highways and rehabilitate key national roads that are part of Trans-European networks. This is expected to lessen the burden on the national budget, both during construction and operation of the toll road. The State Road Agency also aims at introducing weight control systems in order to improve the roads durability along with international standards.

Rail transport is a state monopoly and the reform process has been very slow. In 2012, a law stipulated the transfer of all assets from the State Administration of Railways Transport (“Ukrzaliznytsya”) and other state-owned enterprises related to railways to a new Joint-Stock company (still called Ukrzaliznytsya).30 However, results proved very limited in practice.31

In June 2015, the Ministry of Infrastructure published on its website for debate a draft railroad law. It includes several fundamental measures to comply with European Union directives. In particular, it provides for equal access to infrastructures for private locomotive traction; differentiation of infrastructural, investment, locomotive, and railcar components in the tariffs; and establishment of the National Transport Regulation Commission (NTRC) under the control of the Cabinet of Ministers. As a result, a holding company is being established on the bases of Ukrainian Railways PJSC,32 with companies divided along the lines of business (infrastructure operator, freight, passenger, etc.). The infrastructure will remain in public ownership, and the state carrier will have the same rights as private ones. The development and modernisation of railway infrastructure will be carried out on a contractual basis between the infrastructure branch of Ukrainian Railways PJSC and the Ministry of Infrastructure.33 International experience shows the importance of separating the carrier and infrastructure operator functions of the state-owned incumbent, while ensuring that its public service obligations are funded adequately.

Ukrainian railways face huge financing needs to renovate rail infrastructure and rolling stock. The Ministry of Infrastructure is examining different options, including a joint venture with a private Ukrainian rail car company. It recognises that the railways must optimise costs through divestment of non-core assets and human resources reform. Another strategic goal is to simplify the freight tariff system (in the past, revenues from freight traffic partly compensated below-cost passenger tariffs) using a transparent cost-plus method.

In the field of air traffic and airports, Ukraine signed an open-sky agreement with the United States in July 2015 and started negotiations on a comprehensive EU-Ukraine aviation agreement. As a result, Ukraine would join the European Common Aviation Area34 and gradually harmonise its civil aviation regulations with EU standards. This would liberalise the aviation market between Ukraine and the EU and open the market for new players (including low-costs). Another priority of Ukraine is the attraction of private investments to improve airport infrastructure and the reconstruction of regional airports.

Seaports and infrastructure facilities have always been state-owned and operated, with commercial and management problems that have resulted in huge losses.35 The Law on Sea Ports (in effect since summer 2013) aims to reform the sector by separating the commercial activities of ports from strategic infrastructure facilities (such as aquatic areas, most hydraulic facilities, moorage walls, etc.) and administrative functions, that are to remain in state ownership and under the operational control of the Seaports Administration (a newly-established state department).36 Private investment in seaport infrastructure facilities is possible under concession agreements, joint operation agreements, lease agreements or other types of investment agreements. The separation of commercial activity from administrative regulation introduces a level playing field between state and private stevedoring companies. For instance, the government recently introduced a uniform tariff for all operators to provide equal access to seaports’ infrastructure.

The Strategy for Ukrainian Sea Ports Development until 2038 recognises the critical role of private investors,37 including in the provision of cargo handling services. In 2012, the government added 18 seaports to the “List of state-owned property that may be subject to concession”.38

Recently completed, launched and contemplated investment projects in Ukrainian ports include:

-

In autumn 2012 Cargill signed a protocol of intent with Yuzhnyi seaport to build a USD 90 million complex for storage and trans-shipment of grains and oilseed; the deal was stopped on 8 June 2015 when a court decided to return the land plot where the complex was to be constructed to insolvent Delta Bank.

-

In April 2014, the first stage of new container terminal in the Quarantine Mole of Odessa was commissioned and handled its first vessel in test mode. Construction started in April 2010 and the terminal will be jointly operated with Hamburg Port Consulting.

-

In February 2015 American private equity investment firm Siguler Guff & Company indirectly acquired 50% of the shares in the private enterprise Illichivsk Container Terminal. The investor intends to develop production volumes of the terminal and increase container capacity of Illichivsk seaport.

-

In June 2015, Soufflet Group signed an MoU to invest up to USD 100 million in Illichivsk port infrastructure.

-

Arcelor Mittal signed an MoU to invest in Oktyabrsk port.

Ukraine joined the 2000 European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Inland Waterways in November 2009. Cabotage (i.e. between Ukrainian ports, including as part of international transport) is reserved to vessels under the Ukrainian flag.39 However, if there is a permit issued by the State Inspectorate of Safety at Maritime and River Transport, it is possible to sail under the flag of another country. The entry of passenger-carrying crafts, sport boats, wind-driven ships and yachts is permitted under the flag of their country.40 According to Article 32 of the Merchant Marine code, only vessels owned by Ukrainian citizens or by a Ukrainian legal entity whose shareholders are all Ukrainian citizens can fly the Ukrainian flag. Foreign vessels hired by Ukrainian citizens under a bareboat charter arrangement can fly the Ukrainian flag for the duration of the arrangement.

Privatisation is expected in 2015 for the Airline Company “Horlytsya” and Aviation Enterprise “Universal Avia”. According to the European Commission, air transport of passengers and cargo between Ukraine and the EU has been growing steadily in recent years.41 The lifting of limitations to weekly flights between Ukraine and the EU and the signing of the comprehensive EU‐Ukraine aviation agreement would strengthen air transport connections, allow reciprocal majority ownership, and benefit users. To attain these objectives, Ukraine would have to align its legislation with EU aviation standards and enforce EU requirements in areas such as aviation safety, air traffic management, environment, economic regulation, competition, consumer protection and social aspects. The agreement, similar to those that the EU has already signed with the Western Balkans, Morocco, Georgia, Jordan, Moldova, and Israel, was initialled in November 2013.

Telecommunications

Ukraine’s telecom liberalisation has been limited (fixed-line services remain a monopoly) and relatively slow: the privatisation of Ukrtelecom was launched in 2000,42 operational activities and the regulatory function were separated in 2005, and the sell-off was only completed in 2011. Trimob LLC, a subsidiary of Ukrtelecom, has long held the only 3G license, with service limited to a few largest cities and consumers mainly using low-tech 2G technology. In February 2015, three 3G licenses were auctioned to MTS, Kyivstar, and Astelit (operating under “the life:)” trademark). These operators are now expanding their 3G network across the country. Lack of available spectrum has prevented the awarding of 4G licenses.43

The legislation includes regulatory principles such as universal service, independence of the regulatory authority, transparency, interconnection, and fair competition. It provides for market opening in three areas: mobile services, internet services, and private networks. This allows telecommunications services providers, on a non-discriminatory basis, to effectively compete to directly supply services to customers. There are no foreign ownership limits or restrictions on types of services for operators, but the operating license strictly determines types of services that the operator can provide.44

Through the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement, Ukraine is expected to ensure a competitive market, transparent functioning of competent state agencies, protection of market players against discrimination, and effective allocation and use of frequencies and national numbering resources. In addition, Ukraine has to ensure that relevant national laws and regulations in the telecom sector, among others, are gradually made compatible with the existing EU laws and regulations. The Coalition Agreement adopted after the parliamentary elections in October 2014 includes commitments to ensure the launch of telecommunication networks of the 4th and 5th generations in 2015. Another ambitious initiative taken by the new parliamentary majority is the implementation of nationwide broadband Internet. The government is planning to introduce spectrum reframing, technological neutrality implementation, and mobile number portability.

The main regulator – the National Commission for State Regulation of Communications and Informatisation (NCCIR), established in January 2005 – is responsible for issuing licences and the allocation of radio frequencies, and for regulating IT and postal services.

The Law “On amendments to certain acts of Ukraine regarding delineation of the State bodies’ powers in sectors of natural monopolies and in communications sector in part of provisions regarding analysis of telecommunications services markets” came into force in December 2012. It aims at helping NCCIR in its analysis of relevant markets, identification of operators holding significant market power, and designation of efficient remedies. The elaboration of other new regulations and methodologies is in progress. Several draft regulations have been issued, covering the joint use of infrastructure of telecommunications networks, identification and analysis of relevant markets of electronic communications services, and license terms for using radio frequency resources. In addition, the draft Law on “Amendments to the Laws of Ukraine on providing measures to ensure the transparency of media ownership and implementation of the state policy principles in the field of television and radio broadcasting” aims at alignment with the EU’s Audiovisual Media Services Directive and the additional definitions in the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, as per the commitments made by Ukraine under the Association Agreement.45

Financial sector development

Banking is the backbone of the Ukrainian financial sector, accounting for 95% of total assets in 2012. Non-bank financial institutions on the other hand are relatively underdeveloped, with insurance companies representing 4.5% of financial sector assets in 2012. Micro finance is extended through local credit unions, while factoring and particularly leasing services are mostly offered by large banks and companies affiliated with them. Compared to its peers in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, the leasing sector is well-developed in Ukraine (the cumulated value of new leasing contracts amounted to approximately 2% of GDP in 2013). However, in 2014 the leasing market shrank and registered a 78% year-on-year decrease in the amounts of new leasing contracts (EBRD et al., 2015).

An important development is the planned consolidation of State Regulation of Financial services (through the liquidation of the Commission for Regulation of Financial Services Markets). According to Draft law 2414,46 still under discussion in Parliament, only two entities will be responsible for the control and supervision of the financial sector: the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) and the National Securities and Stock Market Commission (NSSMC). After adoption of Draft Law 2414, the NBU would regulate insurance companies, credit unions and leasing companies, while the regulation of private pension funds would be transferred to the NCSSM.

Banking

The banking sector has been plagued by different problems in recent years, which have not impeded its rapid development but have exposed its underlying fragility (Barisitz and Fungáčová, 2015). Considering its lower middle-income status, Ukraine has a rather high bank-assets-to-GDP ratio (86% in 2014) which suggests overleveraging (Raiffeisen Research, 2015). Following a prolonged boom, credit institutions were hit by the 2008-09 crisis and again in 2014 from geopolitical tensions, deep recession and the plunge of the Hryvnia. The exchange rate risk is in fact high: in July 2015, an estimated 53% of all credits were denominated in foreign currency.47 Lack of trust in banks translated in a 37.7% fall in deposits in real terms in 2014.48 Household deposits suffered an even deeper contraction, falling by 46% in 2014, partly due to limited trust in the Deposit Guarantee Fund (DGF), with a delay of several months. Deposits’ loss accounted for about 15% of total banking sector assets. According to NBU data, the first semester of 2015 saw a further erosion of bank deposits, especially those in foreign-currency.

Among 163 banks registered in Ukraine at the end of 2014, PrivatBank (the largest) and two state-owned banks (the Ukrainian Export-Import Bank: Ukreximbank and the State Saving Bank: Oschadsbank) represented 35% of total assets (USD 68 billion). However, the Ukrainian banking sector is rather fragmented compared to peers in Eastern Europe.49 A large number of credit institutions are so-called “pocket banks” or “agent banks”, i.e. extended financial departments of domestic financial and industrial groups. They tend to distribute credit mainly within their groups, thanks to lax supervision over related party transactions and opaque ownership structures.

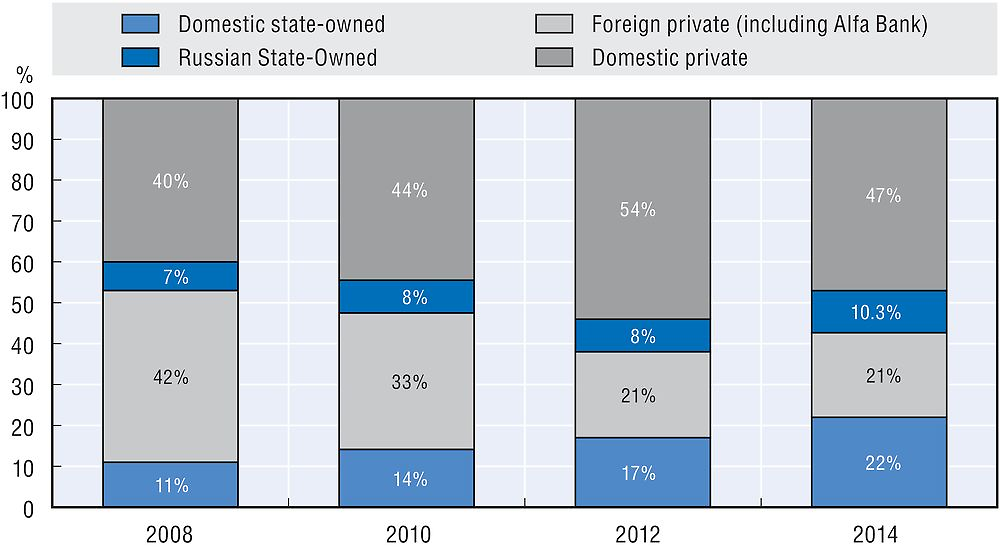

Since Ukraine’s WTO accession, foreign credit institutions have the same rights and obligations as Ukrainian banks.50 Ukraine benefited from an influx of foreign capital into its banking sector before the 2008-09 crisis. Private foreign banks (many of them from the European Union) introduced higher service standards and more diversified products (World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2014). In the aftermath of the 2008-09 crisis, some foreign banks exited the market51; other institutions engaged in deleveraging and are still decreasing the size of their balance sheets. As a result, the share of private foreign banks in total banking sector assets fell from 33% in 2010 to 21% in 2014 (Figure 3.2 below). In contrast to other foreign banks, Russian banks (all of them state-owned, except for Alfa Bank) stabilised their share of the Ukrainian banking market (13% of total assets in 2014, up from 12% in 2010). Because of market consolidation, the number of foreign banks has been decreasing along with the overall number of banks (see Table 3.1 above).

Source: Based on Raiffeisen Research (2015), Central and Eastern Europe banking sector report, Vienna, www.rbinternational.com/eBusiness/services/resources/media/829189266947841370829189181316930732_ 829602947997338151_829603177241218127-1078945710712239641-1-2-EN.pdf; World Bank and International Finance Corporation (2014), World Bank and International Finance Corporation (2014), Ukraine – Opportunities and challenges for private sector development, Washington, wwwds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/-WDSP/IB/2014/01/13/000456288_20140113092348/Rendered/PDF/ACS47780revised0ESW00OUO090.pdf.

Short maturity is a problem that reflects the lack of stable local currency funding. In 2014, half of local currency corporate loans was extended for less than one year, and only 12% had maturities of five years or more. Even though corporate loans dominate the loan portfolio of the Ukrainian banking system, large businesses can also access long-term funding on foreign markets. An additional problem is insufficient information regarding borrower’s creditworthiness: Despite recent progress, Ukraine’s credit information system remains incomplete and fragmented. Judicial proceedings for contract enforcement are long, costly and unpredictable. Because of this risky lending environment, borrowers face higher interest rates and banks adopt very conservative credit allocation patterns (World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2014).

In 2012, Ukraine had the highest share (76%) of companies reporting credit constraints in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, up from only 50% in 2008.52 This deterioration reflects the degradation of financing conditions over the period. In 2013, only 19% of firms used bank credits, ten percentage points lower than in the Eastern Europe and Caucasus region (EBRD et al., 2015).

The credit constraint seems particularly stringent for SMEs: SME loans financing dropped by an estimated 30-40% since 2012. Firm-level data from the business environment and enterprise performance survey53 (BEEPS V) suggest that access to credit is particularly problematic for medium-size enterprises (from 50 to 250 employees). High rates on non-performing loans (NPLs) among SMEs have triggered stricter bank filters. High interest rates are a major obstacle to access to bank finance: in 2013, 36% of firms who did not apply for a loan reported it as the main obstacle, the highest level in the Eastern Europe and Caucasus region. SMEs do not make use of government support for SME bank financing (interest rate subsidies or partial compensation of loan payments) outside of the agricultural sector. Even in Agriculture, the amounts provided are relatively small (EBRD et al., 2015). Box 3.2 provides for a brief comparative assessment of legal, regulatory and policy aspects of access to finance by SMEs.

The government’s microloan entity, the Ukrainian Fund for Entrepreneurship Support, is an instrument to facilitate access to finance by SMEs. However, it did not provide any financing in 2014 and is currently being audited. The establishment of a general credit guarantee scheme with private sector participation is currently under consideration (EBRD et al., 2015).

The SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2016 – Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, includes a comparative assessment of legal, regulatory and policy aspects of access to finance by SMEs (Dimension 6 of the Index), such as the protection of creditor’s rights and the framework for taking collateral. A legal and regulatory framework that enables the collection and distribution of credit information on borrowers (through functioning credit information reporting systems) and ensures the ability of banks to take security and enforce it effectively (functioning registries for security interests, etc.) can play an important role in decreasing lending risks.

Even though there is still much room for progress, the Index report acknowledges some regulatory improvements in recent years:

-

Since the establishment of a unified cadastre (land registry) in 2012, its geographical coverage and online availability have been continuously improved, though neither are fully comprehensive at this point in time. Moreover, the current moratorium on the sale of agricultural land means that this type of land cannot be used as collateral. Regarding security interests, the Ukrainian State Register of Encumbrances over Movable Property does register movable assets, but is neither regulated nor fully accessible online for the general public.

-

The coverage of private credit information bureaus has significantly increased over the past three years. In 2012, 17% of the adult population was covered, while in 2015 coverage is up to 48%, with a legally secured right to access one’s credit history once a year for free. Ukraine does not have a public information bureau (credit registry), even though the NBU plans to create one in 2016 (see below).

The report also points out two persisting challenges:

-

Despite the existing legal framework for protecting secured creditors, enforcement of collateral through the court system is slow and inefficient, in part due to corruption. A 2013 legal provision allows secured creditors to be paid out of queue, though in practice only 8.6% of creditors’ claims were met in 2014 (8.9% in 2012).

-

Regarding banking regulations, while capital adequacy rules have been largely implemented, most other Basel II recommendations have not. Since 2012, the legal framework on capital markets remains unchanged, as well as the number of listed companies on the main stock exchanges.

The table below provides the assessment of policy dimensions relevant for the legal and regulatory dimensions of access to finance for SMEs. Indicators are structured around five levels of policy reforms, with 1 being the weakest and 5 being the strongest. They measure both the regulatory framework in place and its effective implementation.

Non-performing loans (NPLs) have become an almost unsurmountable problem. According to the NBU definition (which includes doubtful and loss loans, as recorded in the balance sheets), NPLs as a share of total loans increased from 12.9% at end-2013 to 24.1% in May 2015. The IMF also includes substandard loans (most of them in foreign currency) and shows a similar trend although at higher levels (from 23.5% at end-2013 to 44.3% in May 2015). Profitability has suffered dramatically: according to IMF estimates, the return on equity (ROE) of the overall banking system is -30.5% in 2014 (IMF, 2015). The situation worsened in 2015: in the first four months, Ukrainian banks (mostly those in liquidation or under administration) reported losses of UAH 83 billion or USD 3.9 billion (versus UAH 53 billion or USD 2.5 billion in 2014 and profits of UAH 1 billion or USD 47 million in 2013).54

Degrading asset quality and the liquidity crunch due to deposit outflows have combined to cause the number of insolvent banks to reach record levels. Since January 2014, the NBU has classified 54 banks (out of 180 registered banks at that time, see Table 3.1 above) as insolvent, accounting for more than one fifth of the system’s total assets. In 2014, despite massive liquidity support to solvent banks by the NBU, total credit outstanding contracted by 31% in real terms (Barisitz and Fungáčová, 2015).55 With more banks expected to exit the market, the current crisis episode should result in some consolidation of the banking system.

In the framework of the IMF arrangement under the Extend Fund Facility (further “IMF Program”), Ukraine is undertaking significant financial sector reforms:

-

Bank recapitalisation and statutory capital requirements. As part of Ukraine’s IMF program, diagnostic studies and asset quality reviews (“stress-tests”) of banks were undertaken in 2014. As a result, 13 banks raised their capital by UAH 45.6 billion or USD 2.1 billion (2.3% of GDP), while five did not and were subsequently dismantled (IMF, 2015). Indeed, the recent Bank restructuring law requires banks to carry out capitalisation and/or restructuring to ensure compliance with the capital adequacy requirements resulting from these diagnostics. A new wave of diagnostic studies is underway concerning the largest 20 banks, which have to submit credible recapitalisation plans detailing capital injections up to 2018. In the case of foreign-owned banks, recapitalisation by their owners is expected, with possible involvement of international financial institutions. Furthermore, the NBU increased the minimal statutory capital requirement for banks to UAH 500 million or USD 23 million (a fourfold increase from the previous level) and set up a compulsory schedule (until 2024) for credit institutions to progressively increase their statutory capital.

-

Bank resolution and deposit insurance. Since January 2014, the financial resources of the Deposit Guarantee Fund (DGF) have come under pressure, obliging the government to provide extensive financial support.56 With assistance from the World Bank, Ukraine drafted and adopted new legislation to enhance its deposit guarantee and bank resolution frameworks, and to strengthen the DGF’s capacities.57 It aims at improving asset recovery from failed banks: for instance, the timeframe to complete bank liquidation has been increased from three to five years, while the period of administration will be reduced to one month in 2016. Finally, bank managers will face criminal responsibility in case of fraud regarding depositors’ database. Overall, this enhanced framework, provided full implementation, is expected to facilitate the clean-up of the banking sector from insolvent banks and to speed up depositor pay out (IMF, 2015).

-

Reform of the National Bank of Ukraine. In June 2015, Parliament adopted amendments to the NBU law in order to improve its governance and strengthen its financial autonomy from the executive.58 For instance, as of 2016 the preservation of a minimal level of reserves will be prioritised over profit transfers to the government. The government also plans to enhance the supervisory capacity of the NBU through new discretionary powers in the field of bank regulation (IMF, 2015).

-

Unified credit registry. The establishment of a unified credit registry at the NBU was being discussed in Parliament in October 2015.59 It would likely significantly improve Ukraine’s credit information system,60 since the transfer of information by banks would be mandatory and the registry would thus cover 100% of legal entities and individuals. The unified registry would also strengthen the supervision capacity of the NBU, by providing the regulator with exhaustive data on the concentration of credit risks and related party lending. International organisations have been advocating for the creation of such a unified registry of credit history (see, for instance, World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2014).

-

NPL Resolution Framework. In the framework of the IMF programme, the government is also committed to strengthen the corporate insolvency and credit enforcement regimes and to remove tax impediments to insolvency and debt restructuring activities. A coordinated out-of-court restructuring arrangement for corporate debt is also being designed (IMF, 2015). These reforms are essential to facilitate the resolution of NPLs, since exposure from the 2008-09 crisis is still burdening banks due to insufficient write-offs (Raiffeisen Research, 2015).

-

Related-party lending and ownership disclosure. New banking regulations introduced in 2015 aim at making the shareholding structure more transparent and enhance the liability of related persons.61 The law expands the list of persons related to a bank, sets out new rules and restrictions on transactions with related persons, and increases civil, administrative and criminal liability of persons related to a bank. Banks will have to unwind above-the-limit loans to related parties. A review process of related party lending has also started, supported by independent accounting firms, and a dedicated unit is being created within the NBU to identify and monitor loans to related parties in all banks. The new regulatory framework also requires banks to disclose key stakeholders (defined as any individual owning shares in a legal entity or any person holding 2% or more of the shares in a legal entity with the peculiarities as set forth by the article 2 of the Law of Ukraine “On Banks and Banking”) in their ownership chain.

Despite this ongoing progress in financial sector reform, the Parliament adopted in July a controversial law on mandatory conversion of retail foreign-exchange loans that could entail substantial losses for banks (IMF, 2015).62 However, this legislation has not come into force and may face subsequent revision.

Insurance

The insurance market in Ukraine, despite a few years of rapid development up to 2008, is significantly behind other Eastern European markets in terms of size.63 Gross insurance assets accounted for only 4.5% of GDP in 2014. While risk insurance has been dynamic, driven by motor and property insurance, life insurance is still in its infancy (it represents 8% of the 2014 gross collected premiums). Like their banking counterparts, Ukrainian insurance companies suffered from the economic downturn in 2014, which led to a decline of collected gross premiums (-6.6%) in a context of growing claims and degrading asset liquidity. In particular, since bank deposits account for more than 20% of insurers’ assets, the rise of bank insolvencies in 2014 exposed insurers to increased liquidity risks.

Insurance activities are subject to licensing and regulated by the 1996 Law “On Insurance”,64 which stipulates that insurance services can be provided by a Ukrainian legal entity in the form of a joint-stock company, a general partnership, a limited partnership or an additional responsibility company.65 Such legal entity must have registered with the State Register of Financial Institutions and obtained an insurance license. The National Commission for the regulation of financial services (hereafter–the National Commission), which is the regulator of the insurance market in Ukraine, delivers insurance licenses.

The charter capital of an insurer must be at least equal to the Hryvnia equivalent of EUR 1 million (USD 1.13 million). The requirement is higher regarding life insurers, whose charter capital must be higher than EUR 10 million (USD 11.3 million).66 Upon registration, an insurer must comply with various requirements regarding the existence of qualified staff, adequate office premises and technical equipment. The regulator imposes additional conditions regarding the qualifications of key personnel (general manager, deputy general manager, chief accountant and actuary) and key documents, for instance a bank or auditor certificate confirming the amount of paid capital. In addition, insurance companies must register their insurance conditions (description of all their insurance products) and any amendments thereto with the regulator. The National Commission monitors the financial situation of insurers through compulsory quarterly financial reporting and is authorised to carry out on-site inspections in order to ensure compliance with prudential solvency and integrity requirements. All these regulations apply irrespective of the national origin of investors.

There is full competition between national and foreign enterprises, subject to the fulfilment of the applicable legal requirements on a non-discriminatory basis. From May 2013 onwards, Ukrainian legislation allows non-resident insurers to set up branches in Ukraine: the licensing conditions and procedures are similar to those for resident insurers67 (a guarantee deposit in a resident Ukrainian bank replaces the charter capital). Under certain conditions,68 direct insurance from abroad is authorised concerning reinsurance transactions, as well as in the fields of overseas transport, commercial aviation and space shifts, and freight and cargo.

The number of market participants has been slowly decreasing for several years, as the result of the withdrawal of insurance licenses. At the end of March 2015, 385 insurance companies operated in Ukraine (330 in risk insurance and only 55 in life insurance). The small life insurance market, where the largest 10 companies accounted for more than 90% of overall gross premiums in 2014, is much more concentrated than the risk insurance market.

Foreign insurers, many of them from the European Union and Russia, are well represented in the Ukrainian insurance market. Several multinational insurance groups such as the Vienna insurance group, Axa, Allianz and UNIQA operate in the country. Out of the 15 largest insurers by gross premiums collected in 2014, eight are affiliates of foreign insurance companies.69

The relatively poor institutional and regulatory framework is one of the key constraints weighing on the development of the insurance sector and other non-bank financial institutions. Despite recent improvements, such as new requirements regarding the risk management system of insurers, the quality of insurance legislation and supervision remains inadequate (EBRD, 2011). The lack of capacity of the National Commission to enforce sound prudential rules is widely acknowledged (World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2014). A moratorium on inspections of SMEs currently prevents the National Commission from carrying out on-site inspections of many insurance companies.

To address these issues, the regulatory framework of the insurance market will be significantly amended. A new law on insurance70 is being prepared and should be adopted by the end of 2015. The draft law draws upon relevant EU norms71 and IAIS (International Association of Insurance supervisors) standards and principles to modernise insurance market regulations. Its implementation should significantly improve supervision and strengthen prudential and transparency requirements (for instance, solvency requirements will depend on asset quality). The draft law also gives new powers to the insurance regulator to safeguard the interest of policyholders of financially weak insurance companies. Moreover, upon adoption by Parliament of Draft Law 2414,72 the National Commission will transfer most of its attributions to the National Bank of Ukraine (already in charge of banking supervision). The purpose of this reform is to strengthen supervision and enforcement of prudential rules and avoid regulatory fragmentation. The NBU will then become the regulator of the insurance market.

Other financial intermediaries such as credit unions, private pension funds, and investment companies are less developed. With a rapidly aging population, a comprehensive reform is being considered (adoption in Parliament is expected by December 2015) to strengthen the financial viability of the pension system. It combines adjustments to the existing mandatory pay-as-you-go system (“the first pillar”) to reduce its structural deficit and the introduction of a second, mandatory and fully-funded pension pillar in 2017 (IMF, 2015). A third pillar, based on voluntary contributions to insurance companies or private pension funds, already exists, although the volume of contributions is insignificant.

Natural resources

Despite being one of the world’s leading producers of manganese ore, titanium ores, and titanium sponge, Ukraine has failed to remain competitive in metallurgy because of high energy requirements, insufficient new investments, and the often differing interests of the government and the owners of privately owned industrial facilities (Safirova, 2012). The subsoil remains the exclusive property of the State and an authorisation is mandatory for its use.73 The subsoil rights have to be granted on a competitive basis, i.e. through tenders or auctions; but an applicant has to obtain the approval of the corresponding local elected body, usually at the oblast level, before being allowed to participate in an auction. The corresponding elected bodies customarily consider such petitions during their biannual sessions, a procedure which significantly slows the government’s ability to conduct auctions. To simplify the process, in August 2012 the central government proposed to delegate the issuance of approvals to local governments, which can process the approvals more quickly. To implement those changes, the Ukraine Parliament would need to approve relevant amendments to the Mining Code and the Code on Regional and Local Administrations. Special licenses are usually required for mineral resources that have been determined to be of national importance.

A new version of the Code was approved by Cabinet in April 2014. Its purpose, as mentioned in the explanatory note, is to modernise and harmonise all subsoil legislation, modify the right to use subsoil, and reduce the number of approvals and other bureaucratic procedures, in particular for water use. It also states that the subsoil use agreement should contain all the technical, economic, social, environmental and other obligations of the parties and permit to transfer subsoil use rights, terms and conditions for subsoil production and distribution.

The Law on Production-Sharing Agreements (PSAs) was promulgated in 1999. PSAs benefits include: freedom of contract and extension of rights of a subsoil user; prolongation of subsoil use term, non-interrupted special permits for exploration and production; government assistance in obtaining permits; pricing and disposal of hydrocarbons; investment protection and dispute resolution in international arbitration. According to the Tax Code, parties to a PSA are exempt from paying taxes other than corporate profits tax, value-added tax, personal income tax, a single charge for mandatory state social security in respect of Ukrainian employees and foreign individuals employed in Ukraine, state charges and duties for receipt of state services (if any) and charges for subsoil use.

The PSA Law also established the PSA Interagency Commission comprised of “the central body of executive power in the sphere of geological study and rational use of subsoil”, which at present is the State Service for Geology and Subsoil of Ukraine (“Derzhgeonadra”) and the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources (“Ministry of Ecology”). An ExxonMobil-led consortium concluded the only PSA agreement so far to tap a Black Sea natural gas field. Internal coordination was also weakened by the decision to abolish the Commission in December 2012. The Law “On Amendments to the Law of Ukraine ’On Production-Sharing Agreements Concerning the State Regulation of the Conclusion and Performance of the Agreements’” restored the PSA Commission as the government institution formally responsible for all PSA issues.74

Since July 2013, Ukraine has also been a candidate country for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). A new law was approved in 2015 to introduce European financial reporting standards in this regard.75 Subsoil users are now expected to disclose information on taxes and royalties paid and on commercial activities related to mining operations in Ukraine. According to the Law, the Cabinet of Ministers must develop the relevant procedure before 12 September 2015. The government should consider adhering to the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas.

References

Barisitz, S. and Z. Fungáčová (2015), “Ukraine: struggling banking sector and substantial political and economic uncertainty”, BOFIT Policy Brief 2015, No. 3, www.suomenpankki.fi/bofit/tutkimus/tutkimusjulkaisut/policy_brief/Documents/2015/bpb0315.pdf.

Deloitte (2015), Central Europe Top 500 rating, Deloitte Central Europe, Warsaw, http://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/central-europe-top500-2014.html.

Differ Group (2012), “The Ukrainian electricity system – a brief overview”, Differ analysis serie, www.differgroup.com/Portals/53/images/Ukraine_overall_final.pdf.

EBRD (2011), Strategy for Ukraine (2011-2014), Approved by the Board of Directors in April 2011, www.ebrd.com/downloads/country/strategy/ukraine_country_strategy_ 2011_2014.pdf.

EBRD, ETF, EU and OECD (2015), SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2016, Paris, OECD Publishing, Forthcoming.

International Energy Agency (2012), “Energy Policies beyond IEA countries: Ukraine 2012”, Energy Policies beyond IEA countries, Paris, www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication-/Ukraine2012_free.pdf.

International Finance Corporation (2015), Unlocking the Potential for Private Sector Participation in District Heating, Washington, www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/8fb84a00496e1a08a2c9f2cda2aea-2d1/WB+IFC+Private+Sector_web.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

International Monetary Fund (2015), First review of Ukraine’s extended arrangement under the ETF Facility (Staff report and Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies in appendix), IMF Country report No. 15/218, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15218.pdf.

OECD (2014), OECD Territorial Reviews: Ukraine 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204836-en.

Raiffeisen Research (2015), Central and Eastern Europe banking sector report, Vienna, www.rbinternational.com/eBusiness/services/resources/media/829189266947841370829189181316930732_829602947997338151_829603177241218127-1078945710712239641-1-2-EN.pdf.

Safirova (2012), “The Mineral Industry of Ukraine”, 2012 Minerals Yearbook, US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/country/2012/myb3-2012-up.pdf.

World Bank and International Finance Corporation (2014), Ukraine – Opportunities and challenges for private sector development, Washington, wwwds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/-WDSP/IB/2014/01/13/000456288_20140113092348/Rendered/PDF/ACS47780revised0ESW00OUO090.pdf.

Notes

← 1. In the Build-Operate-Transfer Model (BOP), the private partner may design, build and operate an asset before transferring it back to the government when the operating contract ends, or at some other pre-specified time. See OECD (2011).

← 2. Law No. 997-XIV “On Concessions” (16 July 1999).

← 3. Law No. 2404-VI “On Public-Private Partnership” (1 July 2010).

← 4. Law No. 662-IV “On Concessions for Construction and Operation of Motor Roads” (3 April 2003).

← 5. Law No. 3687-VI “On the Peculiarities of Concessions of municipal property in heating, water collection and distribution” (8 July 2011), as amended.

← 6. Law No. 2624-VI “On the Peculiarities of Concessions of municipal property in heating, water collection and distribution” (21 November 2010).

← 7. The Parliament adopted Draft law No. 1058 “On Amendments to some Legislative Acts of Ukraine on the removal of regulatory barriers for development of public-private partnership in Ukraine and stimulation investment” (27 November 2014) on 24 November 2015.

← 8. For instance, the acquisitions of goods and services as part of PPP arrangements would no longer be subject to public procurement procedures.

← 9. At around 23 EUR cents per kWh, the average price received by renewable energy producers is around eight times higher than the non-renewable wholesale price. Solar powerproducers receive the largest subsidy at around 47 EUR cents per kWh. See Differ (2012).

← 10. In April 2015 the Ukraine prosecutor’s office announced it would seek to cancel what it described as three “rigged” privatisations of electricity utilities conducted under the regime of Viktor Yanukovych.

← 11. DTEK, whose power stations generate around 25% the national electricity production, is owned by the Ukrainian magnate Rinat Akhmetov (holding “System Capital Management”).

← 12. Resolution No. 271 “On Conducting a Transparent and Competitive Privatization in 2015” (12 May 2015).

← 13. See World Bank, Private Participation in Infrastructure Project Database, http://ppi.worldbank.org, accessed 1 July 2015.

← 14. Law No. 663 “On Basic Principles of the Electricity Market Functioning” (24 October 2013).

← 15. The balancing market serves to increase or decrease the load so as to ensure secure and reliable operation of the energy system; the ancillary market serves to maintain reserve capacity, frequency and quality of electricity supply as well as to ensure security and reliability of the energy system.

← 16. See Russell Pittman (2015), “Restructuring Ukraine’s Electricity Sector: What Are We Trying to Accomplish?”, Vox Ukraine, 7 February.

← 17. Law No. 2544-XII “OnPrivatisation of State Property” of 4 March 1992, Article 5.

← 18. Resolution No. 83/2015 of the Cabinet of Ministers (4 March 2015).

← 19. Governmental Order No. 915-r.

← 20. In 2000-13, the CAGR for production was 0.2%, while that for the production/consumption ratio was 3.3%, the second-highest in Europe after Bulgaria [see ENI (2014), World Oil and Gas Review].

← 21. Naftogaz has paid USD3.1 billion to Gazprom with regard to the November/December 2013 and April – June 2014 invoices, leaving the final clearance of accounts to the Stockholm arbitration procedure.

← 22. Law No. 2250 “On Natural Gas Market” (9 May 2015). The Energy Community Secretariat assisted in preparing the initial draft that mainly reflects the Third Energy Package requirements.

← 23. Law No. 2010-d “On Introduction of Changes to Certain Laws of Ukraine with respect to Securing Competitive Conditions for the Production of Electricity from Alternative Energy Sources” (19 May 2015).

← 24. The relatively small section of the Ukraine Power System – Burstyn Island – is synchronized with EU’s ENTSO-E which is separated from the rest of the transmission system of Ukraine that operates in synchronous parallel mode with the United Power System (UPS) of the Russian Federation.

← 25. See Press release of Naftogaz Ukraine (18 June 2014), Datashows Ukraine’s gas transit system is almost 8 times more reliable than Russia’s, www.naftogaz.com/www/3/nakweben.nsf/0/-98A90DDFBDED941BC2257CFB0069E841.

← 26. For further details and the complete database, please refer to the LPI Index webpage, available at: http://lpi.worldbank.org/international/global.

← 27. See Draft Law No. 69 (20 November 2015).

← 28. The Ministry of Transport and Communication solicited inputs from the general public, the Association of Taxi Dispatchers and Drivers, and numerous non-government organisations, including the Kyiv Cyclists’ Association.

← 29. Source: Minister of Infrastructure of Ukraine, as quoted by RBC Ukraine.

← 30. Law 4442-VI “On the Specifics of Establishment of Public Joint Stock Company of Public Railway Transport” (23 February 2012) and Law 5099-VI “On Amendments to the Law of Ukraine ’On Railroad Transport’” (5 July 2015).

← 31. Ukrzaliznytsia Joint-Stock Company reportedly lost UAH 9.3 billion (USD 440 million) in 2014, primarily on account of tariffs raises that were insufficient to balance the increase in the prices of energy and other inputs. Further losses amounting to UAH 1 billion (USD 50 million) resulted from the lack of compensation for transportation of government-subsidizedpassengers. Capital expenditures are far from sufficient to maintain the network and the equipment. See Centre for Transport Strategies, “Interview with the New Acting Head of Ukrzaliznytsia: Private Traction Will Emerge Whether We Desire it or Not”, 21 August 2015, http://en.cfts.org.ua/articles/interview_with_the_new_acting_head_of_ukrzaliznytsia_private_traction_will_ emerge_whether_we_desire_it_or_not.

← 32. In September 2015, the Cabinet of Ministers published the charter of the new railways holding company. See Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers No. 735 (2 September 2015).

← 33. For more details, see “Why the American Model is Unacceptable for the Ukrainian Railway Reform”, Svitlana Zabolotska, Vox Ukraine. Available at http://voxukraine.org/2015/09/14/why-the-american-model-is-unacceptable-for-the-ukrainian-railway-reform-eng/.

← 34. The European Common Aviation Area (CAA) is an arrangement to allow gradual market opening between the EU and its neighbours, which is intrinsically linked with regulatory convergence through the gradual implementation of EU aviation rules.Western Balkan Countries, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Moldova and Morocco have already joined the CAA. For further details: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/air/international_aviation/external_aviation_policy/neighbourhood_en.htm.

← 35. During the Soviet period, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic accessed the Black and Azov Sea routes through its seaports, which were strategic territories subject to a special regime controlled directly from Moscow.

← 36. Law No. 4709-VI “On Sea Ports of Ukraine” (17 May 2012).

← 37. Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers (11 July 2013).

← 38. Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers (24 November 2012).

← 39. Merchant Marine Code of Ukraine, Article 131 (4 July 2013).

← 40. Resolution No. 155 “On opening river ports for the call of foreign non-military vessels” (29 February 2012).

← 41. European Commission - Fact Sheet, “European Commission support for Ukraine” (27 April 2015).

← 42. See Law No. 1869 “On Particularities of Privatization of the Open Joint Stock Company Ukrtelecom” (13 July 2000), which offered investors up to 43% stock. The law was terminated on 5 July 2005 and just three weeks later, on 25 July 2005, Ukrtelecom once againappeared on the priority list of enterprises slated for privatization.

← 43. The spectrum required for offering 4G services is currently only available to state security and defence authorities – so-called ”special users.”

← 44. Among the major private ISPs are Volia, Triolan, Vega and Datagroup, all of them Ukrainian-owned.

← 45. No. 1831 (29 May 2015). For a thorough analysis, see Council of Europe (2015), Opinion of DGI (Directorate of Information Society and Action Against Crime, Information Society Department, Media and Internet Governance Division), DGI(2015)15.

← 46. Draft law No. 2414a registered on July 20, 2015, accessed on 2 September 2015. The President of Ukraine introduced this draft law.

← 47. NBU Data. The share of foreign currency was 34% at the end of 2013 and went up because of the fall of the hryvnia.

← 48. Figures are exchange-rate adjusted to account for the depreciation of the hryvnia (Barisitz and Fungáčová, 2015, p. 11).

← 49. Even though the current crisis is causing overall market consolidation, the share of the five largest banks amounted to only 43% of total assets at the end of 2014 (Raiffeisen Research, 2015).

← 50. NBU permission is still required for establishing a commercial bank with foreign participation or for converting an existing commercial bank into a bank with foreign participation.

← 51. In 2012-13, Commerzbank (Germany), Swedbankand SEB (Sweden), and Erste (Austria) sold their subsidiaries to Ukrainian investors.

← 52. Credit constrained firms reported needing a bank loan, but either decided not to apply for one or had their loan application rejected. The Eastern Europe and Caucasus region comprises Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

← 53. Data from BEEPS V (2011-2014), the fifth wave of the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey, administered by the EBRD and the World Bank (dataset available at http://ebrd-beeps.com/).

← 54. “Lack of confidence in Ukraine’s economy hinders banks”, Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, 1 June 2015.

← 55. Exchange rate adjusted.

← 56. In 2014 alone, the government borrowed UAH 10 billion or USD 470 million (0.6% of GDP) to support the DGF and secure pay-outs to insured depositors. According to its Deputy Director, the DGF managed UAH 320 billion ( USD 15 billion) in assets from failed banks in July 2015.

← 57. Notably Law No. 629-XIX “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts regarding the improvement of the deposit guarantee system for individuals and dissolving insolvent banks” (16 July 2015).

← 58. Law No. 541-VIII “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts regarding the enhancement of the institutional capacity of the National Bank of Ukraine” (18 June 2015).

← 59. Draft law No. 3111 registered on 16 September 2015, accessed on 7 October 2015.

← 60. Up to now, banks rely on several credit history bureaus with partial coverage, and banks report data on borrowers to them on a voluntary basis. This creates high risks and high transaction costs, passed along to borrowers in the form of higher interest rates and rejections of good quality credit applications by banks.

← 61. Law No. 218-VIII “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine Regarding Responsibility of Persons Related to a Bank” (2 March 2015).

← 62. Draft law No. 1558-1 “On the restructuration of foreign-exchange loans”, adopted by the Ukrainian parliament on 2nd July, 2015, requires banks to convert retail foreign-exchange loans into hryvnia at the exchange rate applicable when the loan was issued. As of January 2016, the President has still not signed the bill into law.

← 63. The 2015 Deloitte rating of the top 50 insurance companies (ranked by gross premiums collected in 2014) in Central Europe does not include any Ukrainian company, reflecting both market fragmentation and the small size of the Ukrainian insurance market. See Deloitte (2015).

← 64. Law No. 85/96 “On Insurance” (7 March 1996, as amended).

← 65. The draft Law “On Insurance” discussed in Parliament at the end of 2015 would require all insurance companies to register as joint-stock companies, which are subject to higher transparency requirements (publication of financial accounts and of the identity of largeshareholders).

← 66. The Insurance Law No. 85/96 of 7 March 1996, as ammended sets minimum capital requirements denominated in euros.

← 67. A foreign insurer must also respect additional conditions to open a branch in Ukraine: for instance, its country of registration must have signed a double taxation treaty with Ukraine and its financial solvency rating must satisfy a minimal threshold defined by the National Commission.