3. Skills, gender and family configuration in Latin America

School enrolment and educational attainment have increased substantially across the Latin America region, closing earlier gaps between boys and girls. Results from PISA find girls outperform boys in reading skills across all socio-economic groups. However, their better performance does not translate into better labour-market outcomes than their male peers. Latin American women have, on average, substantially less favourable labour-market outcomes and earnings than OECD women. Parental expectations and occupational choices condition women’s labour-market choices, earnings and opportunities for increasing skills in the workplace in Latin America. Early cohabitation (whether in marriage or not) and adolescent parenting are more prevalent among young women than young men in the region, placing them on a lower earnings trajectory that can lead to a lifetime disadvantage that cascades down to the next generation of girls.

This chapter analyses gender gaps in skills acquisition and proficiency. It is underpinned by a broad literature review covering gender gaps in education and reading and numeracy skills, the influence of family background on educational and major life outcomes, and the various gaps that emerge and widen over men and women’s working lives. The analysis also explores the effects of family configurations on skills accumulation, growth and labour-market outcomes. It examines gender differences in skills proficiency over the life cycle, the role of family background in acquiring skills, and how the relationship between skills and timing of new family formation determines social and economic outcomes for women and men. It shines a light on the challenges and opportunities to improve labour-market outcomes in Latin America. It focuses primarily on a descriptive analysis of different types of cross-sectional skills survey data to identify gaps and patterns. It applies some regression analyses to look at correlations between skills formation and proficiency with pivotal labour-market and life outcomes.

The chapter relies on data from the Programme of International Student Assessment (PISA), an international assessment that measures the reading, mathematics and science literacy of 15-year-olds every three years. PISA also contains key additional information about students’ socio-economic and cultural status, and parental attitudes. Since its start in 2000, it has incorporated 10 Latin American countries. The chapter also uses data from the first cycle of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), which collects information on the level and distribution of skills in adult populations, as well as the extent of skills use in different contexts. Data are available for OECD countries and partner economies, including four Latin American countries. Finally, the adult skills data are supplemented with data from the World Bank Skills Towards Employability and Productivity (STEP) Skills Measurement Program, which also measured the distribution of literacy skills in adult populations in urban areas in several developing economies, including Bolivia and Colombia in Latin America. Although the STEP surveys measure literacy on the same scale as PIAAC, allowing for a degree of comparability, the two cannot be considered entirely interchangeable (see Chapter 4 for more details). Annex Table 3.A.1 lists the countries covered by each dataset.

Human capital is a key determinant of success in the labour market. People can accumulate human capital through two main channels: first, through education or formal schooling, and second, at work, through on-the-job or off-the-job training. This section examines gender differences in reading skills during childhood and adulthood, as well as gender gaps in labour-market outcomes in Latin America.

Gender gaps in reading skills during childhood

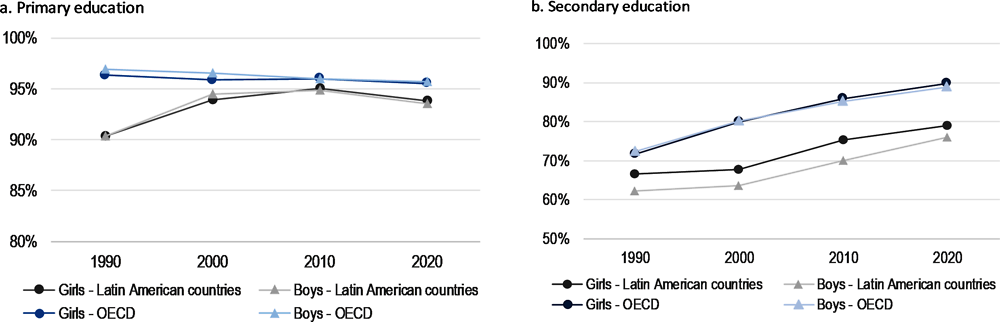

During the past 30 years, all countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have experienced a sharp increase in the number of boys and girls enrolled in primary and secondary education. Gender gaps in primary education have effectively been closed, and girls outnumber boys in secondary education. However, the region is still far below the average secondary enrolment rates observed in OECD countries (Figure 3.1).1

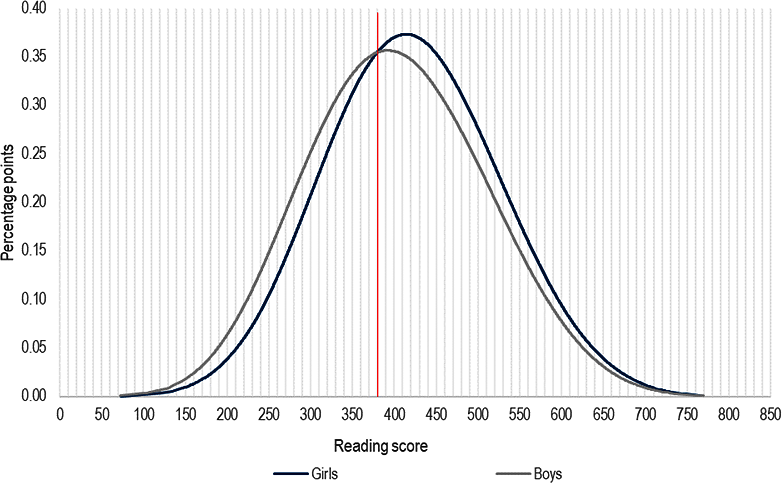

A comparison of PISA results between 2012 and 2018 shows that the gender gap in literacy skills has narrowed, although girls still outperform boys by an average of 18 points (Figure 3.2).2 In most Latin American countries, this narrowing of the gap in may be due to a combination of a decline in the average performance of girls and a minor improvement in the average performance of boys (OECD, 2019[4]). Among OECD countries, the narrowing seems to reflect a decline in girls’ average performance in reading.

Variation in performance distribution suggests that gender differences in literacy proficiency at the extreme ends are often more substantial than they are at the mean. In PISA 2018, the reading performance of boys has a larger standard deviation and a lower mean, which suggests that boys are more likely to score towards the bottom of the performance scale. Latin American boys tend to be over-represented among students who scored below 350 score points in literacy proficiency, while girls are more likely than boys to attain the highest scores (Figure 3.3).

There are large differences in the size of the gender gap in reading proficiency related to socio-economic background. Overall across LAC countries, advantaged students (those in the top quartile of the PISA index of economic, social, and cultural status in their country) scored on average 92.2 points higher in literacy than disadvantaged students (those in the bottom quartile of the index in their country).3 When comparing the average literacy performance of boys and girls within socio-economic groups, girls significantly outperformed boys, irrespective of their socio-economic status (Figure 3.4). The largest gender gaps are observed in the top quartiles in Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay.

Attitudes towards learning are likely to explain gender differences in literacy skills. Evidence suggests a positive association between academic performance and enjoyment of reading (OECD, 2019[4]). In Latin America, PISA 2018 data show that girls enjoy reading more than boys: on average, 50.4% of 15-year-old girls and 30.6% of 15-year-old boys reported reading for enjoyment for more than 30 minutes of their time. In OECD countries the rates are 42.5% for girls and 26.4% for boys. This could partly explain why girls tend to perform better in reading assessments. Another important aspect of learning is time devoted to homework. According to PISA 2018, girls in the region tend to spend more time than boys doing homework, with 73.5% of girls and 64.7% of boys reporting that they had studied at home for more than one hour after school. In OECD countries, 83.4% of girls and 73.5% of boys reported devoting over an hour to homework.

Differences in attitudes towards competition and test endurance could provide further explanations for existing gender gaps in skills among children and adolescents. In the region, PISA data found that boys, on average, are more likely to express positive attitudes towards competition than girls. Boys tend to find enjoyment in situations that involve competition with others (68.8% of boys and 59.4% of girls) and try harder when they are in competition with other people (72.6% of boys and 63.1% of girls). Another factor behind the gender gap might be endurance. Borgonovi and Bicek (2016[5]) suggest that academic endurance, or the ability to maintain the baseline rate of successful test completion for the duration of a test, affects how well children perform on PISA. The authors found that boys seem to tire faster than girls, and that this gap in endurance is larger in reading than in mathematics and science.

This section has shown that despite the steady increase in primary and secondary school enrolment rates, children in the region lack adequate reading skills. Girls tend to fare better than boys in literacy proficiency, but their labour-market outcomes do not reflect this relative advantage. The next two sections explore gender differences in skills and labour-market outcomes for adults in the region.

Adult skills, gender and labour-market outcomes

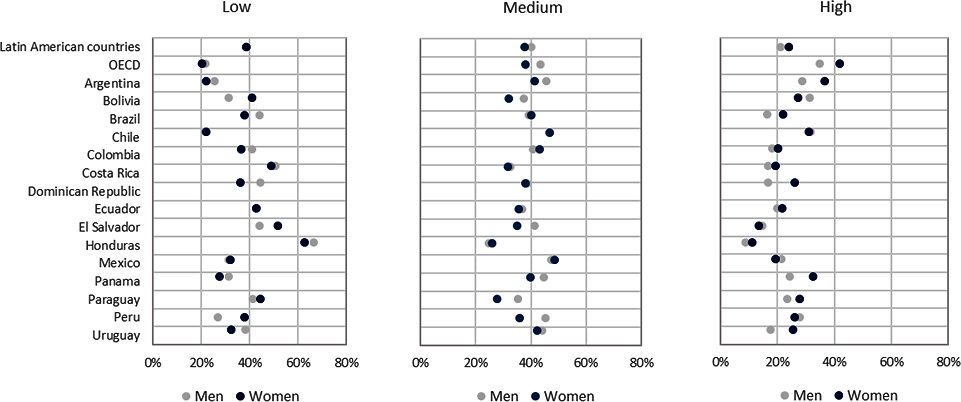

Educational attainment has increased in Latin America over the past decades, but the average share of low-qualified adults is still large compared to OECD countries. The average number of years of education attained by the adult population (ages 25 to 65) in the region increased from 7 years in 1990 to 9.5 years in 2020.4 During the same period, the region has experienced a sharp decrease in the share of low-educated adults (defined as those who attained 8 years or less of education), and an increase in medium-educated (with between 9 and 13 years of education) and high-educated adults (more than 13 years of education). Most Latin American countries, however, still have a larger share of low-educated adults and smaller shares of medium- and high-educated adults than OECD countries (Figure 3.5).

In most Latin American countries, the distribution of educational attainment is similar for men and women. Data from 2019 indicate that, on average across the region, 38.8% of men and 38.4% of women would be considered low-educated, while 40.0% of men and 37.6% of women were medium-educated. While the share of medium-educated women lies between 30% and 50% in most countries, the share of low-educated women ranges from 30% or less in Argentina, Chile and Panama, to 50% or more in El Salvador and Honduras. Although there are more high-educated women than men in most Latin American countries, the share is still below the average for OECD countries. For instance, 36.7% of working-age women in Argentina, 32.4% in Panama, and 31.0% in Chile have completed more than 13 years of education, whereas the average share for OECD countries is 42% (Figure 3.6).

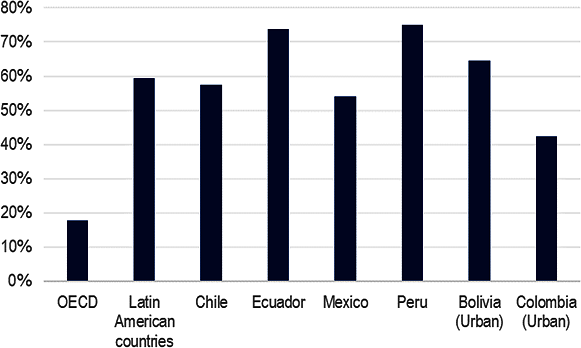

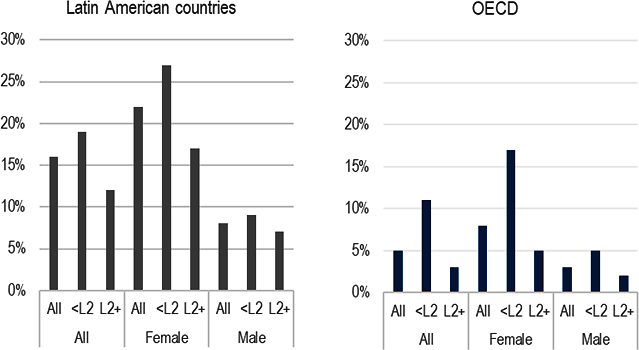

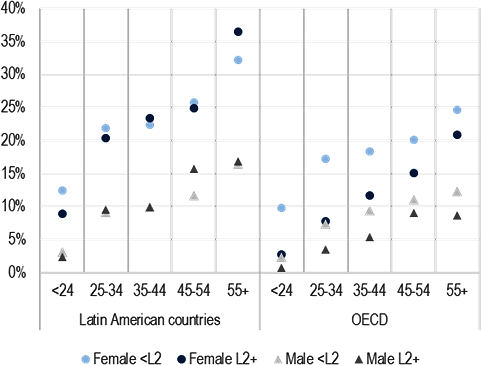

Despite their increased years of schooling, adults in Latin America lack basic reading5 skills, with little difference between men and women. Negative learning outcomes experienced in childhood and adolescence are likely to have translated into poor skill development as adults. Data from the first cycle of PIAAC for Chile, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru indicate that, on average, 59.5% of working-age adults (25-65-year-olds) have low levels of reading skills – i.e. scoring below Level 2.6 This is about 3.4 times more than the OECD average (Figure 3.7). Similarly, STEP data for Bolivia and Colombia show that, on average, 53.4% of working-age adults have low levels of reading skills. The results for men and women in the region are comparable, with 59.3% of men and 60.1% of women scoring below Level 2, in contrast with the OECD averages of 17.6% of men and 17.7% of women. Nor are there any substantial gender differences among different age groups (Figure 3.8). On average, 46.4% of women aged 25-29 are low performers, rising to 74.8% of 60-65-year-old women.

Other measures of the skills of the labour force in the region raise concerns. The latest version of the World Bank Enterprise Survey data shows that about one-third of firms (28.6%) in Latin America identified an inadequately trained workforce as a constraint to their activity. Of particular concern is the shortage of high-skilled workers in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, which is likely driven by deficiencies in learning during secondary school and inadequate university training, as well as a lack of self-confidence in mathematical abilities, particularly among women (Fiszbein, Cosentino and Cumsille, 2016[10]).

Literacy skills also vary according to labour-market status. PIAAC data indicate that, on average, about 42.4% of employed adults in the Latin American sample have a high proficiency level in reading (at or above Level 2), which is about 43 percentage points below the OECD average of 85.9%. Unemployed and inactive adults in the region tend to be less proficient: 41.1% of unemployed individuals, and 34.9% of inactive ones, were in the high-level category on average. The data also reveal some small gender differences. On average, 43.5% of employed women and 41.7% of employed men have high literacy skills but the gender gap is reversed for inactive adults, with 34.4% of inactive women and 36.9% of inactive men having high skills (Figure 3.9).

The skills of informal workers are equally important. The informal sector is large in Latin America and poor education and skills have been identified as one of the underlying reasons for labour informality in the region (World Bank, 2019[11]).7 The skills profile of informal workers tends to be low: on average, 50% of informal workers in Bolivia and Colombia scored below Level 2 in the reading skills measure of STEP 2011.8 Women fare slightly worse than men by this metric: 69% of women and 67% of men working in the informal sector in Bolivia have a low level of reading proficiency. In Colombia the figures were 47% of women and 43% of men.

Workers with greater literacy proficiency earn more on average, but the PIAAC data reveal gender differences in the distribution of earnings (Figure 3.10). In OECD countries, the top 25% of best-paid women scoring at Level 2 or above earn, on average, about 22% less than the top-paid men scoring at the same level. In marked contrast, in Latin America, higher-skilled women at the top of the earnings distribution earn about the same as similarly skilled men. This overall average disguises different patterns in countries within the region. In Chile, among those scoring at Level 2 and above, the top 25% of best-paid women earn about 15% less than top-earning men. The pay gap is substantially larger in urban Bolivia (where they earn 40% less) and urban Colombia (37% less). In contrast, top-earning, higher-skilled women in Mexico earn 6.4% more than their male peers.

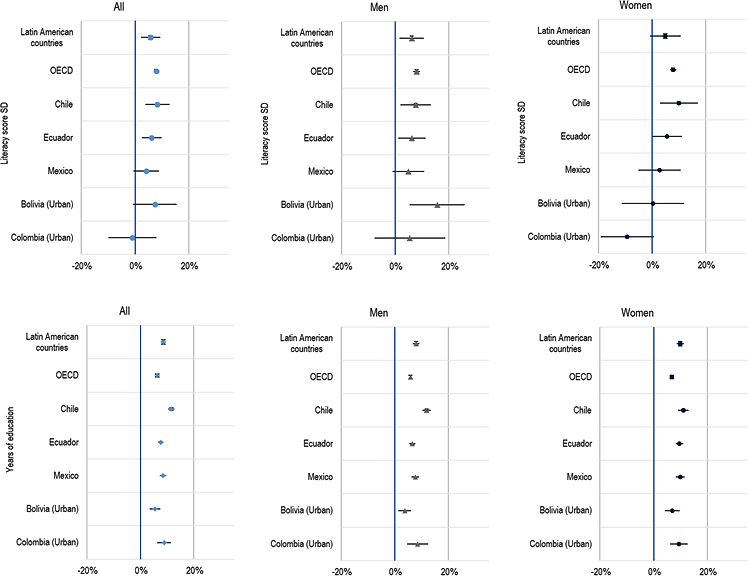

The earning returns to reading skills are 5.8% in Latin American countries, after adjusting for years of education and potential experience (Figure 3.11). On average, the returns to reading skills in the region are lower than in OECD countries, where they could reach 7.9%. The effect of skills on earnings appears to be lower for Latin American women (5%) than for men (6.1%. Although the estimations using the PIAAC data are interpreted as associations rather than causal effects, they suggest that, for women, the increase in earnings associated with a one-standard-deviation increase in reading proficiency ranges from 5.7% in Ecuador to 10% in Chile.9 For men, the increase in earnings ranges from 6.2% in Ecuador to 15.6% in urban Bolivia. The effect of reading skills proficiency on workers’ earnings in Mexico and urban Colombia is likely to be null.

Although girls do better than boys in reading and almost as well in mathematics during their formative years, gender gaps in labour-market outcomes may be partly due to women’s choices of careers. The unequal representation of women in the labour market may reflect significant gender differences in career aspirations among adolescents. On average, across Latin America, PISA 2018 data found that 33.5% of 15-year-old students expected to work in a science-related occupation by the age of around 30 (see Chapter 2 for more details on 15-year-old students’ career aspirations in the region). Although a slightly larger proportion of girls in the region (34.6%) expected to work in STEM than boys (32.4%), Latin American women are under-represented in STEM fields (López-Bassols et al., 2018[12]). PIAAC data also provide evidence of gender differences in occupation in the region. In the high-skilled occupations, there are slightly more men (52.45%) than women (47.55%), whereas the opposite is true in medium-skilled occupations, where women account for 59% of the labour force.10 An analysis by occupation11 finds striking over-representation of men among science and engineering professionals, 70.2% of whom are men. In contrast, women are over-represented among health professionals (71.4% women) and teaching professionals (62.5% women).12

The first cycle of PIAAC also provides information on the qualifications that workers consider necessary to do their jobs.13 Comparing workers’ actual qualifications with self-reported qualification requirements, measured in years of education, suggests 53.8% of workers in the region have the right level of qualification for their jobs, about 3 percentage points above the OECD average. On average, about one-quarter of workers in the region have lower educational attainment than required by their jobs, with a similar share who are overqualified. Mismatches vary by country, however, with the share of underqualified workers ranging from 18.2% in Peru to 28.2% in Ecuador. Men are more likely to be underqualified: across the region 24.9% of men have lower educational attainment than required for their jobs, compared to 20.5% of women (Figure 3.12). The prevalence of underqualification among men might reflect both the rapid growth in educational attainment among women and that firms are now demanding higher qualifications than before.

The level of human capital that individuals accumulate is associated with the conditions of the families they are born into. Family effects and their relationship with human capital, particularly education, have been thoroughly studied. The Coleman Report (1966[13]) compiled the efforts of the US Education Commission to provide, for the first time, a comprehensive set of evidence based on a wide sample of families. Before that, education policies were usually designed with a focus on improving inputs for better achievements: better school infrastructure, varying class sizes and better teachers, for example (Egalite, 2016[14]). Afterwards, more attention was paid to the relation between human capital formation and household dynamics. Since then, there has been a huge refinement in the study of the transmission channels through which families affect future generations’ lives. One of the main findings, which is now a current consensus, is that family effects account for 45-50% of the variation in years of schooling (Salvanes and Bjorklund, 2010[15]).

Family background and skills development

There are multiple channels by which inequality transmits from one generation to the next. One is socio-economic status, which is associated with the performance of children in reading assessments, as we will show below. Another is parental education. Better-educated parents are more aware of the value of more years of schooling and a better quality of education. Even after controlling for income level, their children are usually more educated (Salvanes and Bjorklund, 2010[15]). The influence of parental education can be long-lasting, especially in the labour market. Evidence suggests that parental education accounts for more social mobility than parental income itself (Winthrop, Barton and McGivney, 2018[16]). This relationship is, however, highly dependent on countries’ education systems (Scandurra and Calero, 2017[17]). This section explores the extent to which parental education may affect the returns to reading skills in the labour market in the region.

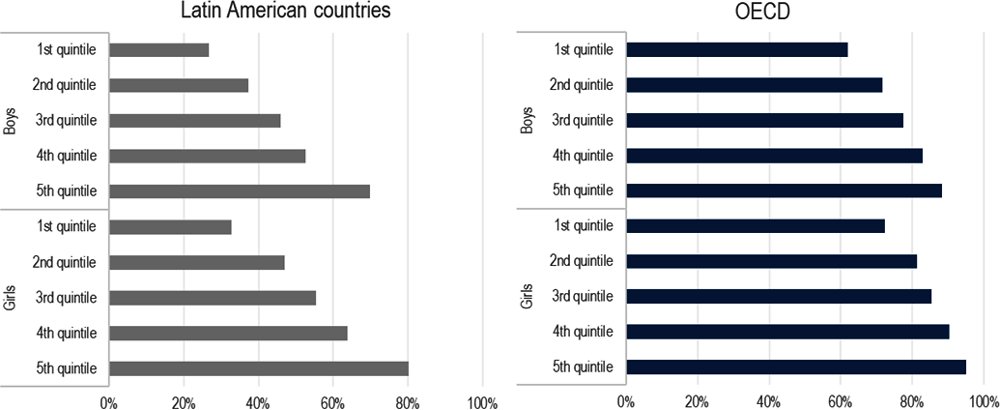

There is a socio-economic gradient in reading proficiency in Latin America. Figure 3.13 displays the relationship between socio-economic status, based on the ESCS index, and proficiency in reading. In the Latin American countries with data available, the higher socio-economic quintiles tend to concentrate the largest number of both girls and boys with greater reading performance. OECD countries display a somewhat less unequal picture, since larger numbers of top performers can be found even among the lowest quintiles of the socio-economic distribution, irrespective of their gender.

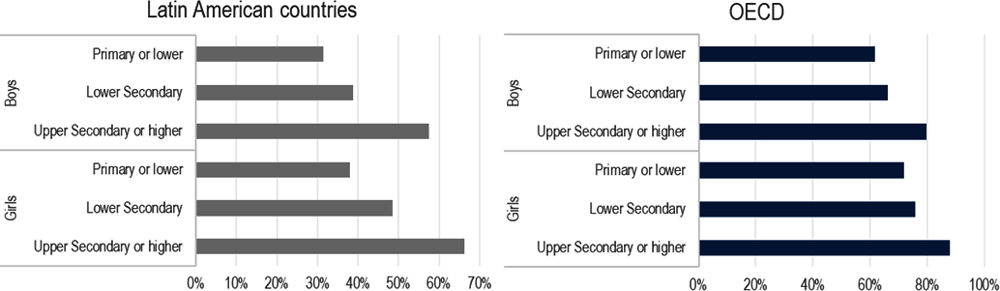

Parental education is also likely to influence reading proficiency and educational attainment in Latin America. PISA data reveal substantial gaps in reading skills between children whose mothers had high levels of education (upper secondary or above), and those with low levels of education (lower secondary or below).14 Figure 3.14 shows that 37.9% of girls in the region whose mothers had only primary education or below, and 48.5% of those whose mothers had completed lower secondary education, scored at or above Level 2 in reading tests, compared to 66.2% of girls whose mothers completed upper secondary or tertiary education. A similar pattern is found among children in all the participating Latin American countries, irrespective of gender. Similarly, PIAAC data indicate that, among Latin American women whose mothers had at least some tertiary education, 38.5% completed upper secondary education and 44.7% completed tertiary education (Figure 3.15). Among women with less educated mothers, in contrast, 30.0% completed upper secondary and 16.3% tertiary education, with similar differences for men. The most striking difference between OECD countries and Latin America is observed among men and women with less educated mothers: these Latin Americans are four times more likely to complete no more than primary education.

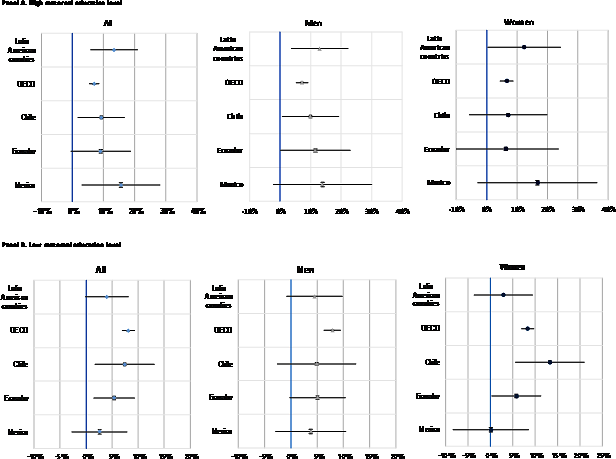

The influence of parental education also seems to extend to the labour-market outcomes of their children. The returns to reading skills tend to increase with the education level of workers’ mothers, and are larger for Latin American men than for women. The estimation of Mincer equations using PIAAC data suggests that average returns to skills for workers with high-educated mothers (who achieved upper secondary or more) range from 9.1% in Ecuador to 15.6% in Mexico, two or more percentage points higher than the estimates for workers with mothers who attained a lower secondary education or less (Figure 3.16, Panels A and B). Pooled estimates for the region indicate that average returns might be substantially larger for workers with high-educated mothers, at 13.4%, compared to 4.0% for workers with low-educated mothers, in line with the estimates for OECD countries. Within-country comparisons suggest that in Chile and Ecuador the returns to reading skills for workers with high-educated mothers are likely to be larger for men than for women, while the opposite is observed in Mexico. For men with high-educated mothers, returns range from 10.0% in Chile to 13.9% in Mexico, whereas for women they range from 6.3% in Ecuador to 16.7% in Mexico.

Expectations and skills development

High parental expectations are associated with higher reading skills in the region. PISA data suggest that across all of Latin America, the majority of parents want their children to achieve tertiary education: 85% of parents of boys, and 89% of parents of girls wish their children to get a university degree or more. In contrast, in OECD countries only 67% of parents of boys and 73% of parents of girls hope their children will complete tertiary education. Although these expectations seem somewhat unrealistic for Latin Americans, given the actual educational achievement figures described earlier in this chapter, they might act to some degree as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Across the region, parents’ hopes for the maximum educational attainment their children will achieve are positively associated with reading skills: children whose parents expect them to achieve no more than a lower secondary education had lower reading scores in PISA (Figure 3.17). Further analysis by gender suggests that girls who are expected to complete tertiary education tend to obtain higher reading scores than boys with similar expectations. In Latin America, this group of girls scored 15.8 points higher than their male peers in PISA tests, on average. These patterns seem consistent with those observed in OECD countries.

Children’s hopes and expectations are just as important as their parents’. Girls and boys who set themselves higher expectations of educational achievement tend to have better reading performance. In Latin America, a larger proportion of girls than boys expect to achieve tertiary education (87% compared to 78%). The shares are larger than for OECD countries, where just 82% of girls and 74% of boys have similar expectations. In some countries, like Chile, as many as 92% of girls expect to achieve tertiary education. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that children’s expectations are more granular: boys are more likely to see themselves as engineers or scientists, while girls see themselves as health workers (Bos et al., 2016[18]). These expectations are also correlated with PISA reading scores: on average, children in Latin America who expect to complete tertiary education score 73.4 points more than those expecting to complete upper secondary (Figure 3.18). This holds especially true for girls: girls who hope to complete tertiary education score, on average, 10.4 points more than similarly ambitious boys in Chile, and 6.8 points more in Mexico.

Differences in performance in school have implications for many of the decisions taken by men and women during their adult life. This section examines the relationship between enrolment in education and reading skills and a number of dimensions of family formation and composition. These include the decision to live with a partner, whether and when to become a parent (and adolescent pregnancy in particular), family structure, and solo parenthood.

Reading skills and cohabitation

Marrying or deciding to live with someone is an important step in the lives of most adults. This section explores the relationship between cohabitation (understood as living with a partner irrespective of marital status) and education and reading proficiency levels, while analysing differences by age, gender and educational status.

In Latin America, adults with the least education and lowest reading skills have the highest rates of cohabitation. For instance, while 68% of adults in the region with only a primary education or less live with a partner, less than 55% of those who have achieved secondary education, or more, do so. The same pattern holds for reading levels: while 61% of those with reading proficiency less than Level 2 (the minimum level required for quality jobs) live with a partner, only 49% of those with higher reading proficiency do (Table 3.1). Peru stands out as the country with the largest differences between those who have low reading proficiency and the rest: 20 percentage points for all, and 22 percentage points for women. Although Latin American countries have lower rates of cohabitation than those in the OECD, a similar pattern holds for most OECD countries and the United States (Fry and Cohn, 2011[19]).

The higher levels of cohabitation amongst those with low reading skills are driven by the young, especially young women. As Table 3.1 shows, among those aged 55 or more, the difference in cohabitation rates in Latin America between those with low reading proficiency and the rest is only 3 percentage points (69% compared to 66%), while this difference rises to 14 percentage points for those aged 16-24 (29% compared to 15%). The rate of cohabitation for young women with low reading skills is strikingly high for that age group, with one in three living with a partner. In contrast, among older men (aged 55 or more), cohabitation is more common for those with better reading skills: 78% of those with high reading levels cohabit, compared to 76% of those with lower scores. This difference is particularly strong in Colombia (9 percentage points) and Ecuador (7 percentage points), and less so in Mexico and Bolivia (3 percentage points). This pattern holds for the OECD in general. In contrast, in Chile and Peru, older men with low reading levels have higher cohabitation rates than their higher-skilled peers.

For young individuals, schooling seems to delay the process of moving in together. As Figure 3.19 shows, both in Latin America and in the OECD, students of all ages are significantly less likely to live with a partner than those who are not studying. Consistent with the findings above, for both students and non-students, living with a partner is more common amongst young women than young men.

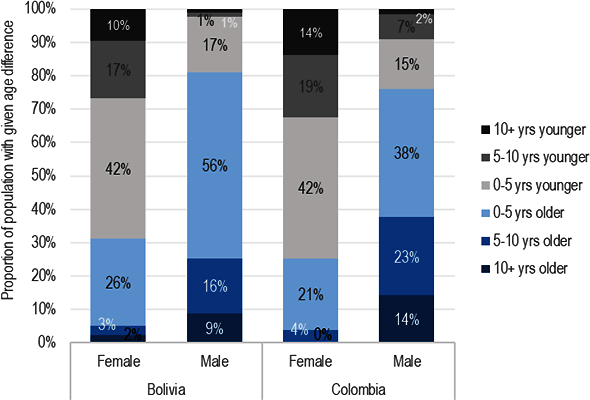

The pattern of women starting to cohabitate much earlier in life than men can be explained by the fact that men tend to live with younger partners. As can be seen in Figure 3.20, in Colombia, 76% of men and 25% of women are older than their partners. A similar pattern holds in Bolivia, where 81% of men and only 31% of women are older than their partners. Although the data only cover urban areas of Colombia and Bolivia, the pattern of women being younger than their male partners has been widely analysed across religions and regions (Pew Research Center, 2019[20]) and has been documented for OECD countries (Jonas and Thorn, 2018[21]). In OECD countries, including the United States, some researchers have found that men are more likely than women to start living with a new partner after a divorce or separation or the death of their spouse or partner (Jonas and Thorn, 2018[21]; Cornell, 1989[22]).

Living with a partner yields economic benefits for those with more education. Since women tend to move in with a partner at a younger age, and after completing fewer years of education, they do not reap the benefits of cohabitation as much as men. Using data for the United States, Fry and Cohn (2011[19]) find that while on average college-educated cohabiters (either married or not) are better off than college graduates without partners, those without college degrees who cohabit are not better off economically than those without college degrees who do not have a partner. Lefgren and McIntyre (2006[23]) also find that women’s educational attainment is strongly related to their husband’s income and marital status and that “women’s education may have a positive causal effect on husband’s earnings, though not on the probability of marriage”.

Reading skills and parenthood

Having a child – and the age when individuals have their first child – has a significant impact on the responsibilities and the dynamics of a household. The age at which they become parents, and the number of children they have, are both defining elements in a person’s life. The consequences are especially strong when a girl becomes pregnant in adolescence, as it is not uncommon for teenage mothers to leave school, voluntarily or involuntarily, leading to employment that tends to be unstable and poorly remunerated and too often traps young women into a vicious cycle of poverty. This section explores the relationship between parenthood and education and reading levels, analysing differences by age, gender and education status.

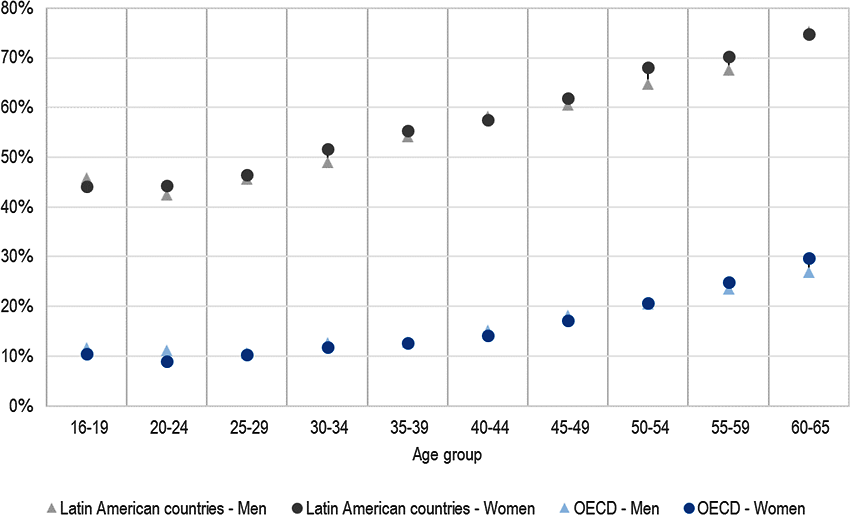

As expected, in both Latin American and OECD countries, for almost all age groups and countries, women of reproductive age are more likely to report being a parent than men.15 The probability of being a parent significantly increases with age, plateauing at around 40 (Figure 3.21). This is consistent with the fact that women’s fertility naturally declines with age. Data show that being a parent is more common in LAC countries than in the OECD, and the differences are especially wide for the younger cohorts: 12 percentage points for those under 25, 21 percentage points for 25-34-year-olds, and 9 percentage points for 35-44-year-olds). After the age of 45, more than four in every five people in both the OECD and LAC have children.

Reading proficiency levels are correlated with delayed parenthood, as is educational attainment. The relationship between reading, enrolment and parenthood might be caused by those studying deciding to wait until the end of their studies to have children, by which time they have developed greater reading skills. Singh’s (1998[24]) study in 43 developing countries finds that higher educational attainment is associated with lower rates of adolescent childbearing. For Latin America, Heaton et al. (2002[25]) have shown that education delays the transitions between initiation of intercourse, partnerships and giving birth, and in particular how secondary levels of schooling are associated with lower early marriage and parenthood.

This is confirmed by our data: as can be seen in Figure 3.22, parenting started earlier amongst those with low reading skills, and in Latin America this is especially the case for women. For instance, while 6% of young women aged 19 with low reading skills have become mothers in OECD countries, the figure is 27.8% among 19-year-old women with low reading skills in Latin America. The difference between the two groups of countries can be seen by the fact that 19-year-old women with high literacy skills in Latin American are as likely to be mothers as 19-year-old women with low literacy skills in the OECD. The difference widens over time: among women aged 25, 47% of those with high reading levels in the OECD are mothers compared to 78.5% of those with low reading skills in Latin America. The same pattern is observed in men although the differences are not as stark: just 3% of boys aged 19 with high literacy levels are parents in the OECD compared to close to 10% of those in Latin America. By around the age of 34, the gap has closed, with more than 90% of men and women being parents, regardless of literacy levels or region. These findings are consistent with the literature that finds that education delays marriage and parenthood for men and women (Teachman and Polonko, 1988[26]), and observations by Jonas and Thorn (2018[21]) in the OECD.

As Figure 3.23 shows, there are strikingly higher rates of teenage pregnancy in LAC countries than in OECD countries, especially for women with low literacy proficiency. In Latin America, one in every six adults became a parent in their adolescent years, but only one in every twenty did so in the OECD. This is in line with data from Latin America and the Caribbean which show persistently high rates of adolescent pregnancies (UNFPA, 2013[27]). Low reading skills appears to be an important mediator of adolescent pregnancy, with nearly 7 percentage points between those with low reading levels – scoring below Level 2 – and the rest. This is consistent with findings of Jonas and Thorn (2018[21]) for the OECD. Teenage parenthood is also substantially more common among women than men: in LAC countries, 22% of women became parents in their teens, but only 8% of men. This could be due to a number of factors including a heightened presence of sexual and gender-based violence against girls and women in Latin America. Urban areas of Bolivia and Colombia stand out as places where adolescent pregnancy is less common, with adolescent parenthood rates among men which are comparable to OECD countries (Table 3.2).

For young adults, educational enrolment is associated with a delayed start of parenthood. As can be seen in Table 3.3, the percentage of young adults who are parents is significantly lower among those enrolled in education. For instance, 16% of 16-19-year-olds who are not in education are parents, compared to 2% of those who are. The difference is particularly high for girls: 25% of those who are not enrolled are parents, compared with only 3% of those who are enrolled. The same patterns hold for OECD countries, although, as discussed earlier, parenthood levels overall are lower for younger age groups. Rates also vary between countries, ranging from 24% of out-of-school 16-19-year-olds being parents in Chile to 11% in urban Colombia, almost equal to the OECD average. While 39% of girls aged 16-19 who are out of school are parents in urban Bolivia, the figure is only 16% in urban Colombia – and around 4% in Germany and Singapore. It should be noted that the direction of the association between pregnancy and school enrolment is not clear: early pregnancy can be both the cause and the consequence of dropping out of education (Birchall, 2018[28]). Research in Paraguay and Peru has found that adolescents who face challenges in school and who have low aspirations in life are more likely to become pregnant (Näslund-Hadley and Binstock, 2011[29]).

As might be expected, not living with a partner is also associated with later parenthood. As can be seen in Table 3.4, the percentage of young adults who are parents is significantly lower among those who are not cohabiting. While more than half of 16-19-year-olds who cohabit in Latin America are parents, this falls to only 2% of those who do not. The percentage is higher for women: 65% of the cohabiters are parents, compared to 4% of those who do not live with a partner. Within the region, urban Bolivia and Chile are exceptional in that over 80% of those aged 16-19 who cohabit are parents (86% in urban Bolivia and 83% in Chile). In Bolivia, this is driven by teenage girls (93% of those aged 16-19 who cohabit are parents) while in Chile it is driven mostly by teenage boys (97% of those aged 16-19 who cohabit are parents). For those cohabiting in their 20s, the likelihood of being a parent does not rise very much with age. However, among those who do not cohabit, women become significantly more likely to be a parent (among 20-24-year-olds, 26% of women do not cohabit and are parents compared to 6% of men; among 25-29-year-olds the shares are 44% of women and 19% of men). This pattern also holds in OECD countries, but at a much lower scale. As with enrolment, cohabiting could be either the cause or the result of pregnancy at early ages. On the one hand, it is likely that the social stigma of being pregnant without a partner leads to social pressures to marry or cohabit. On the other hand, the onset of sexual relations and pregnancy tends to be accelerated when couples live together (Näslund-Hadley and Binstock, 2010[30]).

Reading skills and family structure

Average household sizes are gradually declining almost everywhere (Bradbury, Peterson and Liu, 2014[31]). Households remain slightly larger in Latin America than in the OECD, with the difference being greater among those with low reading skills. As Table 3.5 shows, the average number of children per household is 2.8 in the Latin American countries in the sample, and 2.2 amongst the OECD countries. Within Latin America, those with low reading skills had close to 3 children per household, while those with higher skills had close to 2.3. The differences in the number of children by gender are very small.

Martin and Juarez (1995[32]) had previously documented important differences in household sizes amongst women with different educational levels in Latin America. Interestingly, they highlight that, despite the differentials in actual fertility, desired family size does not vary widely with educational level. Women with lower levels of education have lower contraceptive use, lower socio-economic status, and less knowledge and more fatalistic attitudes towards reproduction. They find that these cognitive, economic and attitudinal differences mediate the influence of schooling on reproductive behaviour and partly explain the fertility gap. In the OECD, the correlation between reading levels and number of children can be explained by the fact that more literate adults tend to have higher educational attainment, which in turn implies living with their partners and forming a family later than those with lower skills. In the OECD, Jonas and Thorn (2018[21]) found that after controlling for respondents’ educational attainment, the strength of the link between reading proficiency and number of children is negligible.

As can be seen in Figure 3.24, in OECD countries, parenthood starts at a later age for those with higher reading levels, regardless of their gender. In Latin American countries, the difference in the average age of first parenthood between those with high and low reading levels seems to be smaller. Although surprising, the small association between reading and age of first child has been observed before. For instance, Parikh and Gupta (2001[33]) also found that, in India, although literacy is a critical precondition to decreased fertility, it only reduced fertility in small percentage terms. Fort and colleagues (2016[34]) studied compulsory schooling reforms in England and continental Europe between 1936 and 1975. They found a negative relationship between education and fertility in England, but no relationship between education and the number of children in the rest of Continental Europe.

Reading skills and solo parenthood

Single- or solo-parent households are those headed by one parent who is responsible for one or more children. In these households, adults care for dependent children for whom they are financially responsible and have sole or shared custody. This increasingly common family arrangement too often has implications on the availability and allocation of time for family care activities. For instance, solo parents may have a more challenging time balancing work and household care activities, especially in the absence of reliable childcare opportunities. A single-family income might increase pressure to work and limit parents’ time to help children with homework and the like. Also, some solo parents may have to work longer hours to make ends meet, making it difficult to pursue professional growth and development opportunities. Unfortunately, the PIAAC and STEP surveys do not include data on family configuration and custody agreements, or how much control parents had had over their family structure, including whether they had chosen to be solo parents.

Like parenthood more generally, solo parenthood increases with age and is more common among women in both Latin America and the OECD. As can be seen in Figure 3.25, the difference in rates between genders is greater in Latin America than in the OECD. Urban Colombia has strikingly high differences in single parenthood between men and women: while 37% of 35-44-year-old women are single parents, the figure is only 2% for 35-44-year-old men. The pattern holds for other age brackets too: 9% of Colombian women and 0% of men are single parents among those aged 24 and under; 19% of women and 7% of men among 25-35-year-olds; 39% of women and 8% of men among 45-55-year-olds; and 35% of women and 12% of men among those aged over 55.

While solo parenting is less common amongst those with higher reading proficiency in the OECD, the pattern is less clear in Latin America. For instance, in Latin America 17% of those with literacy scores below Level 2 are solo parents compared with 14% of those with higher scores; in OECD countries these values are 14% and 8% respectively. Further, in Latin America, single parenting is more common amongst the less proficient below the age of 35, but more common among the more proficient after 45. This is not the case for the OECD, where solo parenting is more common among those with lower literacy levels regardless of age and gender. In both Latin American and OECD countries, however, the larger percentage of female single parents is associated with the fact that women with low reading skills tend to become parents earlier than those with higher skills (Jonas and Thorn, 2018[21]).

Latin America has made substantial progress in closing gender gaps in school enrolment and basic reading proficiency. Data from the PISA surveys show girls performing at a par with or slightly above boys in reading performance. Socio-economic status is associated with skills proficiency, with students from low-income households scoring lower in reading compared to more affluent households. Girls’ relative advantage in reading performance holds steady even in low-income households. Data from the PISA surveys serve to disentangle some of the factors that may be prompting girls’ better performance, including enjoyment of studying and reading. Moreover, the analysis confirms long-standing evidence on the positive impact that parental education and expectations have on their offspring’s own expectations and outcomes.

Interestingly, girls’ relative skills advantage at age 15, and their self-reported high expectations about their education and labour market aspirations, are not reflected in labour-market outcomes. Although data from the PIAAC and STEP skills measurement surveys show that an equally large proportion of adult men and women are not able to meet basic reading skill standards, women fare relatively worse in the labour market, particularly in earnings, in nearly all countries and at all levels. Young women go through an educational and occupational sorting that leads them to sectors and occupations that are less lucrative than those chosen by men. Although this is a function of a combination of variables, including economic, social, cultural, information and societal biases, as well as gender violence, to name a few, this chapter finds that adolescent pregnancy and early unions may be important factors holding young women back from fulfilling their educational and professional aspirations.

Moving forward, it will be vital to identify targeted programmes to support young women as they make their education choices and transition into the labour market, as well as those from disadvantaged and vulnerable households. While it is important to sustain the improvements in girls’ and young women’s skills, on its own, the data in this paper suggest that will not be enough to change the narrative for women. There is still potential to shift societal mindsets about women’s limited roles in society, ban early unions, curb adolescent pregnancy, and eliminate gender-based violence against girls and women, especially in education and labour-market spaces.

References

[28] Birchall, J. (2018), Early marriage, pregnancy and girl child school dropout, Institute of Development Studies, https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14285/470_Early_Marriage_Pregnancy_and_School_Dropout.pdf.

[5] Borgonovi, F. and P. Biecek (2016), “An international comparison of students’ ability to endure fatigue and maintain motivation during a low-stakes tests”, Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 49, pp. 128-237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.001.

[18] Bos, M. et al. (2016), “¿Como se desempeñan los hombres y las mujeres? (How do boys and girls perform?)”, América Latina y el Caribe en PISA 2015 (Latin America and the Caribbean in PISA 2015), Inter-American Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/es/publicacion/17230/america-latina-y-el-caribe-en-pisa-2015-como-se-desempenan-los-hombres-y-las.

[31] Bradbury, M., M. Peterson and J. Liu (2014), “Long-term dynamics of household size and their environmental implications”, Population and Environment, Vol. 36, pp. 73-84, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0203-6.

[13] Coleman, J. and E. al. (1966), Equality of Educational Opportunity, National Center for Educational Statistics.

[22] Cornell, L. (1989), “Gender differences in remarriage after divorce in Japan and the United States”, Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 51/2, pp. 457-463, https://doi.org/10.2307/352507.

[14] Egalite, A. (2016), “How family background influences student achievement: Can schools narrow the gap”, Education Next, Vol. 16/2, https://www.educationnext.org/how-family-background-influences-student-achievement/.

[10] Fiszbein, A., C. Cosentino and B. Cumsille (2016), The Skills Development Challenge in Latin America: Diagnosing the Problems and Identifying Public Policy Solutions, Inter-American Dialogue and Mathematica Policy Research, Washington, DC, https://www.mathematica.org/publications/the-skills-development-challenge-in-latin-america-diagnosing-the-problems-and-identifying-public.

[34] Fort, M., N. Schneeweis and R. Winter-Ebmer (2016), “Is education always reducing fertility? Evidence from compulsory school reforms”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 126/595, pp. 1823-1855, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12394.

[19] Fry, R. and D. Cohn (2011), “Living together: The economics of cohabitation”, Social & Demographic Trends, Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2011/06/pew-social-trends-cohabitation-06-2011.pdf.

[25] Heaton, T., R. Forste and S. Otterstrom (2002), “Family transitions in Latin America: First intercourse, first union and first birth”, International Journal of Population Geography, Vol. 8/1, pp. 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.234.

[35] ILO (2021), “ILO (2021) Employment and informality in Latin America and the Caribbean: an insufficient and unequal recovery”, Technical Note: Labour Overview Series: Latin America and the Caribbean 2021, International Labour Organization, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/---sro-port_of_spain/documents/genericdocument/wcms_819029.pdf.

[21] Jonas, N. and W. Thorn (2018), “Literacy skills and family configurations”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 192, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/509d788a-en.

[23] Lefgren, L. and F. McIntyre (2006), “The relationship between women’s education and marriage outcomes”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 24/4, pp. 787-830, https://doi.org/10.1086/506486.

[12] López-Bassols, V. et al. (2018), Las brechas de género en ciencia, tecnología e innovación en América Latina y el Caribe: resultados de una recolección piloto y propuesta metodológica para la medición [Gender gaps in science, technology and innovation in Latin America and the Caribbean], Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.18235/0001082.

[36] Lundberg, S. (2013), “The college type: Personality and educational inequality”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 31/3, pp. 421-441.

[32] Martin, T. and F. Juarez (1995), “The impact of women’s education on fertility in Latin America: Searching for explanations”, International Family Planning Perspectives, Vol. 21/2, pp. 52-57, https://doi.org/10.2307/2133523.

[29] Näslund-Hadley, E. and G. Binstock (2011), El fracaso educativo: Embarazos para no ir a la clase (Educational Failure: Pregnancies to skip school), Inter-American Development Bank, https://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=36225399.

[30] Näslund-Hadley, E. and G. Binstock (2010), “The miseducation of Latin American girls: Poor schooling makes pregnancy a rational choice”, Technical Notes, No. 204, Inter-American Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/10920/miseducation-latin-american-girls-poor-schooling-makes-pregnancy-rational-choice.

[3] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Database, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[4] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

[39] OECD (2016), “Overview: Why skills matter”, in Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-4-en.

[38] OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

[2] OECD (2013), PISA 2012 Database, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/pisa2012database-downloadabledata.htm.

[7] OECD (n.d.), OECD Statistics, OECD, https://stats.oecd.org/.

[8] OECD (n.d.), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/data/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

[33] Parikh, K. and C. Gupta (2001), “How effective is female literacy in reducing fertility?”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 36/35, pp. 3391-3398, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4411060.

[20] Pew Research Center (2019), Religion and Living Arrangements Around the World, Pew Research Center website, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2019/12/12/religion-and-living-arrangements-around-the-world/.

[15] Salvanes, K. and A. Bjorklund (2010), “Education and family background: Mechanisms and policy”, Discussion Paper, No. 14, NHH Department of Economics, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1620398.

[17] Scandurra, R. and J. Calero (2017), “Modeling adult skills in OECD countries”, British Educational Research Journal, Vol. 43/4, pp. 781-804, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3290.

[6] SEDLAC (2022), Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean, CEDLAS and the World Bank, https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/en/estadisticas/sedlac/.

[24] Singh, S. (1998), “Adolescent childbearing in developing countries: A global review”, Studies in Family Planning, Vol. 29/2, pp. 117-136.

[26] Teachman, J. and K. Polonko (1988), “Marriage, parenthood, and the college enrollment of men and women”, Social Forces, Vol. 67/2, pp. 512-523.

[27] UNFPA (2013), Maternidad en la Niñez: Enfrentar el Reto del Embarazo en Adolescentes [Childbearing: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy], United Nations Population Fund, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/ES-SWOP2013.pdf.

[16] Winthrop, R., A. Barton and E. McGivney (2018), Leapfrogging Inequality: Remaking Education to Help Young People Thrive, Brookings Institution Press.

[11] World Bank (2019), Global Economic Prospects: Darkening Skies, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/307751546982400534/Global-Economic-Prospects-Darkening-Skies.

[37] World Bank (2015), STEP Skills Measurement Household Survey 2013 (Wave 2): Documentation, World Bank Microdata Library, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2226/related-materials.

[9] World Bank (n.d.), STEP Skills Measurement Program, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/step.

[1] World Bank (n.d.), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Notes

← 1. In this chapter, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico were not included in the statistics for OECD countries.

← 2. PISA results are scaled to fit approximately normal distributions, with means around 500 score points and standard deviations around 100 score points. In statistical terms, a one-point difference on the PISA scale therefore corresponds to an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.01 and a 10-point difference to an effect size of 0.10.

← 3. The economic, social and cultural status index (ESCS) is a composite measure that combines into a single score the financial, social, cultural and human capital resources available to students (OECD, 2019[4]).

← 4. The statistics for Latin America were calculated using the average number of years of education in the pooled data.

← 5. Reading literacy is defined as the ability to understand, evaluate, use and engage with written texts to participate in society, achieve one’s goals, and develop one’s knowledge and potential” (OECD, 2016[39]).

← 6. At Level 2 respondents are required to make matches between the text and information and may require paraphrase or low-level inferences. Some competing pieces of information may be present. Some tasks require the respondent to cycle through or integrate two or more pieces of information based on criteria, compare or reason about information requested in the question, or navigate within digital texts to access and identify information from various parts of a document. Refer to PIAAC and STEP documentation prepared by the Education Testing Service for more details on the classification of reading scores using PIAAC and STEP data (World Bank, 2015[37]).

← 7. The International Labour Organization estimates that the average informality rate between 2017 and 2019 is around 50% in Latin America. Informality is defined as a lack of access to social protection because of the labour relationship (ILO, 2021[35]).

← 8. STEP defines informal workers as 1) individuals who are currently working and reported not having social security or benefits; 2) individuals who reported being unpaid workers on family businesses; or 3) individuals who reported being self-employed and were the sole employee of their business.

← 9. Since the reading skill measure is standardised to (0,1), the parameter of interest can be interpreted as the percentage increase in earnings associated with a one-standard-deviation increase in measured skills.

← 10. PIAAC uses the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Groups 7-9 are low-skilled occupations, groups 4 and 5 are medium-skilled, and groups 1-3 high-skilled.

← 11. Occupations are defined by two-digit ISCO groups.

← 12. Science and engineering, health, and teaching professionals are identified as ISCO codes 21, 22 and 23, respectively.

← 13. We follow OECD (2016[38]) and define qualification mismatch as the difference in the educational attainment that the person has and that that is required by their job. In PIAAC workers are asked what the usual qualifications would be, if any, “that someone would need to get (their) type of job if applying today”. The answer to this question is used as each worker’s qualification requirements and then compared to their actual qualifications to identify mismatch. Thus, a worker is classified as overqualified when the difference between his or her qualification level and the qualification level required in his or her job is positive. A worker is classified as underqualified when the difference between his or her qualification level and the qualification level required in his or her job is negative.

← 14. Mother’s level of education is a measure of family background correlated with both father’s education and family income (Lundberg, 2013[36]).

← 15. The only exceptions are those aged over 55 in Peru and in Singapore.