16. Japan

Support to agriculture

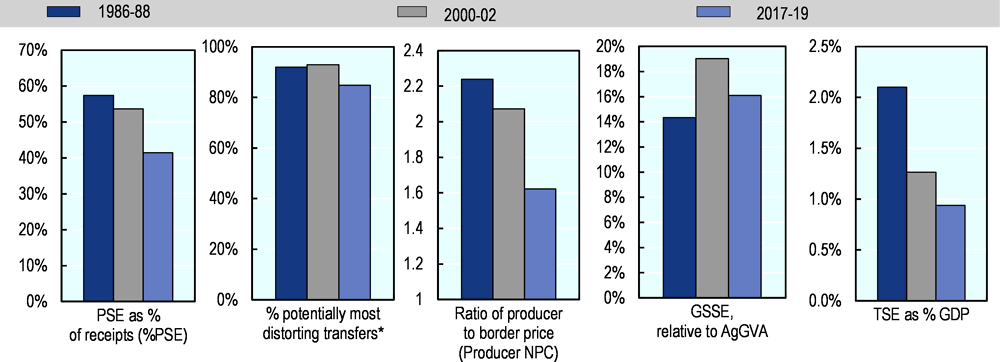

Over the past decade, Japan has reduced its support to agriculture, but more recently the change in support levels has been moderate. Support to producers (PSE) remains high as a share on gross farm receipts (41% in 2017-19) and is almost 2.4 times above the OECD average. The total support estimate to agriculture (TSE) represented 0.9% of Japan’s GDP in 2017-19, most of which went to direct support to producers (PSE).

Market price support (MPS) remains to be the main element of the PSE, accounting for about 80% in 2017-19. It is largely sustained by border measures, in particular for rice, pork and milk. Payments to producers decreased between 2018 and 2019. Budgetary support to producers is mostly delivered as payments based on area and income.

The share of expenditures for general services provided to agriculture (GSSE) relative to TSE is 20%, which is higher than the OECD average but has decreased since the 1990s. The majority of the GSSE financed the development and maintenance of agricultural infrastructure, representing more than four-fifths of the GSSE in 2017-19.

Main policy changes

The Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, which sets Japan's comprehensive agricultural policy direction for the next 10 years, was revised in March 2020. In response to challenges such as the decrease of farming population and the implementation of new large-scale trade agreements, the plan aims to strengthen the agricultural production base regardless of farm size or its hilly and mountainous condition. Emphasis is also placed on sustaining rural areas. Finally, the Basic Plan addresses responses related to the COVID-19.

A series of large-scale natural disasters, including typhoons and heavy rains, hit Japan in 2019, causing major damages to the agricultural sector. The damages in the agricultural, forestry and fisheries sectors are reported at JPY 460.2 billion (USD 4.2 billion). The government earmarked supplementary budget funds of JPY 105.4 billion (USD 1 billion) for the restoration of these sectors, mostly used for the recovery of agricultural facilities and farmland as well as landslides and road destruction in mountains.

Japan raised its consumption tax rate for most goods and services from 8% to 10% in October 2019. However, the consumption tax rate for food and beverages, other than liquor and eating-out services, is set at 8% in order to lessen the burden especially on lower income households.

The Japan-US Agreement came into effect on 1 January 2020. Under the agreement, Japan eliminates or lowers custom duties for certain US agricultural products and provides preferential US-specific quotas for others. The United States eliminates or reduces custom duties on 42 agricultural products.

Assessment and recommendations

Japan has made some progress towards agricultural policy reforms since the early 2000s and has implemented programmes that are steps towards a more market-oriented sector. But support to producers remains more than twice the OECD average as a percentage of gross farm receipts, and continues to be dominated by market price support (MPS), which is among the potentially most distorting form of support. Further improvements are possible to reduce MPS and eliminate measures impeding market signals.

The implementation of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement decreased the border measures for agricultural commodities imported under these agreements. With the bilateral agreement with the United States entering into force, some US agricultural products will benefit from improved market access. Increased competition in the domestic market may also contribute to structural change and further productivity growth in Japanese agriculture. But the exclusion from trade barrier reduction of certain key products such as rice limits the benefits to be reaped.

The continued support provided for crop diversification is likely to help reduce abandonment of paddy fields. However, other policies should be aligned with the ambition to reallocate rice area to other crops, implying in particular a reduction of high market price support for rice.

Large scale natural disasters continued to occur in 2019, causing significant income loss to the agricultural sector. The funds needed to restore damaged infrastructure, both at regional and farm level, put substantial pressure on the national and local public budgets. Having a safety-net for farmers, such as a revenue insurance programme, is one step towards mitigating the risk and damage. However, as climate-related disasters are expected to become more frequent and intense, the government should strengthen efforts to prepare comprehensive programmes to build the sector’s resilience.

There is significant room to improve the environmental performance of agriculture. Japan has one of the highest nutrient surpluses among OECD countries. Moreover, though GHG emissions from agriculture were the lowest among OECD countries, the sector accounts for more than three-quarters of total methane emissions and half of the national nitrous oxide emissions. Japan has set a Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) target of 26% emissions below 2013 by 2030 but no specific target for the agricultural sector. Several environmental programmes have been implemented but agricultural policy programmes should provide consistent incentives to adopt sustainable production practices. An integrated agri-environmental policy framework with quantitative targets in which all farmers commit to improving their environmental performance should be developed.

Although the share of expenditures for general services provided to agriculture relative to total support is higher than the OECD average, the level has decreased since the 1990s. Moreover, most of these expenditures were programmed for infrastructure development and maintenance. Further progress is needed in supporting agricultural knowledge and innovation to enhance the sector’s productivity and sustainability.

Policy responses in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak

Agricultural policies

Japan1 announced a JPY 108.2 trillion (USD 992 billion) stimulus package in April 2020, equivalent to about 20% of its GDP. The package includes the following measures for the agriculture and food sector.

Agricultural producers who have difficulty continuing their business operation benefit from access to increased loan limits, interest concessions and low interest credit of long-term funds financed by the Japan Finance Corporation.

To mitigate the impact of reduced milk consumption due to schools being closed, JPY 2.3 billion (USD 21.5 million) programme supports dairy farmers and processors for excess milk diverted to further processing and non-fat dry milk diverted to animal feed.

Producers and vendors who were planning to deliver their food and agricultural products for school meals could receive supports to find alternative sales channels. Producers and vendors could also donate these remaining products to food banks with transportation costs compensated.

The government provides a subsidy to employers within the agriculture and food sector who grant special paid leave in addition to statutory annual paid leave to their employees, whether on fixed-term or permanent contracts, when they need to take leave to care for their children whose school or childcare provider is temporarily closed as a COVID-19 emergency response.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) extended the premium payment deadlines for agricultural mutual aid and revenue insurance programme.

Measures for COVID-19 were included in the Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Area (the Basic Plan), which Japan revised in March 2020. The Basic Plan, which sets Japan's comprehensive agricultural policy direction for the next 10 years, addresses stimulating demand for domestic agricultural products, securing agricultural labour, and providing relevant information to consumers on food supply.

Agro-food supply chain policies

As short-term demand for domestic agricultural products (e.g. beef, dairy, vegetables, cut-flowers) continues to fall, MAFF has attempted to stimulate demand for agricultural products through press conferences, websites and social media.

MAFF published basic operation guidelines for farmers and food business operators in case of workers becoming infected by COVID-19. The guidelines were made available online.

Consumer policies

The government has monitored food supply chains for any food shortages. MAFF provides information on food availability to the public and also ensures that staple food (rice and wheat) has been stocked. The government has also called on citizens to avoid panic buying.

Support to producers (%PSE) has declined gradually over the long term. During 2017-19, it represented around 41% of gross farm receipts (Figure 16.1). This is down from 57% thirty years ago (1986-88) but remains 2.4 times higher than the OECD average. The share of potentially most distorting support (mainly MPS) has decreased only moderately and still accounts for about 80% of the PSE, meaning it continues to be the main element of that support. Producer support increased slightly in 2019 as larger MPS more than offset some reductions in budgetary support. On average, price gaps widened as lower border prices were not transmitted to domestic prices (Figure 16.2). Prices received by producers were on average 62% higher than world market prices in 2017-19. The level of support varies by commodities but MPS is often the main component of support based on individual commodities (Single Commodity Transfers, SCT). The highest price gap and thus the highest share of SCT in commodity gross farm receipts are seen in rice, followed by barley, grapes, sugar, milk, and cabbage (all above 50%) (Figure 16.3). Expenditures for GSSE were equivalent to 16% of agriculture value added in 2017-19 and were mainly used on the development and maintenance of irrigation and drainage facilities as well as natural disaster prevention. Total Support to Agriculture (TSE) as a share of GDP was 0.9 %, and has declined over time from 2.1% in 1987-89.

Contextual information

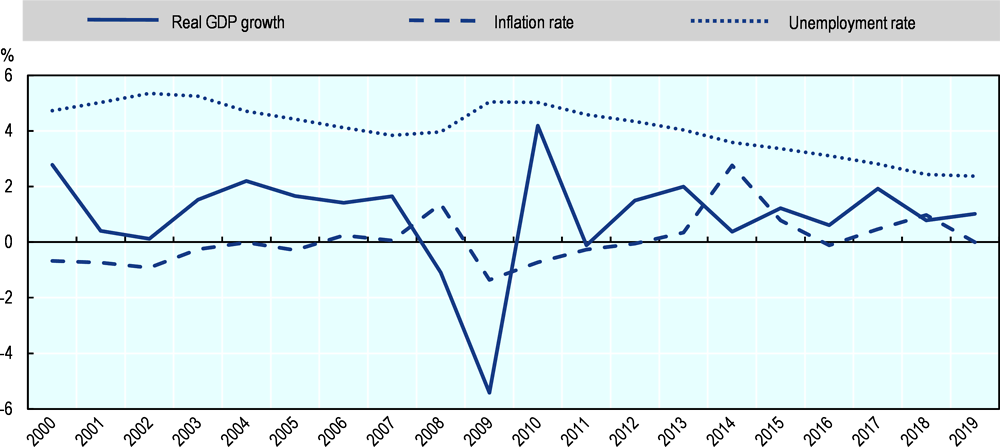

Japan is the world’s third largest economy after the United States and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) with relatively small land area and high population density. The country has experienced slow economic growth and a low inflation rate for most of the past decade, but the unemployment rate is one of the lowest in OECD countries (Figure 16.4). Agriculture constitutes a small share in the economy (1.2% of GDP and 3.2% of employment in 2018) (Table 16.2). The agricultural output had a long downward trend but has been gradually increasing since 2014.

Due largely to the country’s mountainous topography, the agricultural area only represents 11.8% of total land, more than half of which is rice paddy fields (MAFF, 2019[1]). The average farm size remains much smaller than that in other OECD countries, but increased from 1.1 hectares to 2.5 hectares between 1987 and 2019 (MAFF, 2020[2]).

The average age of farmers is 66.8 years and more than 80% of farmers in Japan are over 60 years old (MAFF, 2019[3]). In 2015, farms with more than JPY 30 million (USD 0.25 million) of sales accounted for 3% of all farms, but for 53% of total output (OECD, 2019[4]).

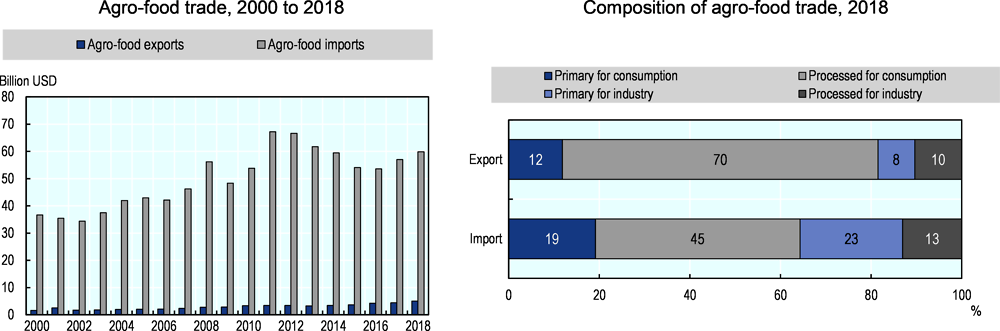

The food self-sufficiency rate was 37% in 2018 on a calorie basis (MAFF, 2019[5]), the lowest in recorded history, meaning that more than 60% of Japanese calorie supply depended on imports. Japan is one of the world’s largest importers of agro-food products and the United States is the biggest source of agricultural imports (FAO, 2020[6]). Forty-five per cent of imports are processed products for consumption (Figure 16.5).

The share of agricultural exports in total exports, on the other hand, constitutes only 0.7%. Most Japanese agricultural exports are directed at final consumers (Figure 16.5). Processed food products such as alcohol and beverages, snacks, sauces and seasonings account for the majority of Japan’s agro-food exports. Among the unprocessed products, apples and beef are the most exported products.

Output growth was negative during 2007-16, as the decline in primary factor growth (land and labour) was larger than the increase in total factor productivity (Figure 16.6). This can be explained by the abandonment of farmland and conversion to non-farm uses (e.g. residential or commercial uses), causing agricultural land area to decrease by 27.6% in the past 60 years (MAFF, 2019[7]).Moreover, the number of commercial farm households is 1.13 million, decreased by more than 50% since 1990.

Japan’s nitrogen and phosphorus balances are among the highest in OECD countries (Table 16.3). The nitrogen balance in 2018 was 179.3 kg per hectare, increasing from 2000, derived from a high degree of fertiliser use and livestock production, combined with a low share of pastureland (Shindo, 2012[8]). The phosphorus balance in 2018 is 57.3 kg per hectare in comparison to 2.3 kg per hectare for the OECD average, and it is in part linked to soil-type related fertilisation needs identified in the past. That is, the reaction of soil in Japan, particularly Andosols, with inorganic phosphate render the phosphate almost insoluble and unavailable for uptake by plants, requiring more intensive phosphorus use by the agricultural sector (FAO, 2015[9]).

In line with its small role in the economy, agriculture’s share in total energy use, 1.2% in 2018, is well below the OECD average. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from agriculture were 2.6% of the total emissions in Japan — the lowest among OECD countries. However, breaking down the type of GHGs in Japan, in 2017, the agricultural sector is responsible for more than three-quarters of total methane emissions, mainly coming from livestock enteric fermentation and rice cultivation. Almost half of the national Nitrous Oxide (N2O) emissions are from manure and fertiliser application (GIO, 2019[10]).

The volume of agricultural water use remains stable for the past few decades. In 2018, the Japanese agricultural sector used 67.6% of water of which 94% was directed for paddy field irrigation (MLIT, 2019[11]).

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Japan maintains a system of high border protection and domestic price support for key agricultural products. In general, Japanese tariffs on agricultural products are higher than those on non-agricultural products. On average, they amounted to 15.7% in 2018,2 compared to 2.5% for non-agricultural products. However, agricultural tariffs vary considerably among products with over 35.7% of tariff lines duty free and 2.9% above 100% (ad valorem equivalent); 13.2% of agricultural tariff lines are non-ad valorem (WTO, 2019[12]). Tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) with high out-of-quota tariffs are applied to some commodities such as rice, wheat, barley and dairy products.

Rice import is conducted through state trading fulfilling Japan’s minimum-access commitment under the WTO Agreement on Agriculture. A TRQ of 682 200 tonnes (milled) is applied. The maximum mark-up (price differences collected by the government when importing and selling) for rice imports is set at JPY 292 (USD 2.7) per kg and the out-of-quota tariff-rate is JPY 341 (USD 3.0) per kg.

A crop diversification payment is paid to farmers who switch their use of paddy fields from table rice production to other crops (wheat, soybeans, rice for feed and flour). This payment is area based (output is also considered for rice for feed and flour). In addition, a payment is provided to municipal government making unique efforts such as using high-yield variety rice for feed and flour, or cultivating buckwheat or rapeseed.

The direct support payment is provided for upland crops (wheat, barley, soybean, sugar beet, starch potato, buckwheat and rapeseed) based on area and output. The area-based payments are based on current planting, while the output-based payments are based on the volume of sales and the quality. Subsidy rates for both payments vary by quality and variety.

The revenue based payment is available for certain crops (rice, wheat, barley, soybean, sugar beet and starch potato) in case the revenue drops below the past average revenue, 90% of the difference between the current revenue and the past average is compensated by the government (75%) and the farmers’ reserve fund (25%).

The Livestock Stabilization Programme for Beef, known as Beef Cattle Marukin, provides support payments to beef cattle producers when the standard sales price falls below the standard production cost. The payments cover 90% of the difference between costs and sales prices. A quarter of the grant payments is paid from the fund filled by cattle producers. A similar programme is applied for hog producers. Additionally, the compensation is paid to producers of milk used for processing.

The revenue insurance programme launched in January 2019 provides a safety net for farmers. The programme is revenue-based and compensates the loss of farm revenue stemming from various factors including market and natural causalities, relative to a benchmark based on the previous five years’ revenues. Government supports 50% of the insurance premium and 75% of the reserve fund.

Commodity insurance mainly covers yield losses and damage of production equipment due to natural disasters, but degradation of crop quality is also insured for some commodities (rice, wheat, barley, and fruit). This voluntary programme is available for a range of commodities (rice, wheat, barley, livestock animal, fruit, and field crops). Government support covers around 50% of the insurance premium. In principle, farmers can participate in either revenue insurance programme or commodity insurance to avoid duplicated payments by the government programmes.

To foster well-qualified agricultural entities, the government has set up a certified farmer programme. The programme grants certified status to farmers (both individuals and corporations) with a management plan approved by national or local municipal authorities. The certified farmers receive several benefits such as income support payments and tax breaks.

To attract younger farmers, Japan offers three types of support programmes. First, a payment is available to new young farmers during a training period (maximum of two years). Second, another payment is granted during the initial operation period (maximum of five years). Up to JPY 1.5 million (USD 13 756) is paid annually to eligible trainees and farmers. Third, the government also provides funding for a maximum of JPY 1.2 million (USD 11 005) to subsidise the training cost of young farmers for a maximum period of two years for agricultural co-operation.

The Farmland Banks3 were established in 2014 to facilitate the consolidation of farmland. These intermediary institutions are found in each prefecture, and some manage large areas of farmland in their regions. The Farmland Banks improve farmland conditions and infrastructure if necessary, and then lease the consolidated farmland to business farmers (e.g. corporations, large-scale family farmers, new farmers). Subsidies are provided to land owners and regional authorities that lease farmland under their responsibility to the Farmland Banks.

Public investment has long been one of the core policies to be implemented for improving rural infrastructure, such as farmland (e.g. enlargement of land plot), agricultural roads, and irrigation and drainage facilities. The government also invests in the prevention and restoration of farm infrastructure from natural disaster, as well as public health facilities construction in rural areas.

Hilly and mountainous areas represent about 40% of total agricultural land and of total agricultural output in Japan. Direct payments are provided to farmers in these areas with the aim to compensate for the production disadvantage (e.g. steep slope and smaller cultivation area), avert the abandonment of agricultural land, and contribute to environmental protection and landscape preservation.

Direct payments for environmentally-friendly agriculture are provided to farmers who conduct activities which are effective in preventing global warming or conserving biodiversity together with reducing the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides by more than half relative to conventional farming practices in the region. Examples of supported activities include cover crop planting, compost application and organic farming. Farmers are required to comply with Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) to receive the payments.

Having ratified the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, Japan plans to decrease GHG emissions from the agricultural sector in several ways: reducing fuel consumption for horticultural facilities and agricultural machinery to reduce CO2 emissions, disseminating water management methods for paddy fields to lower methane emissions, and improving fertiliser use efficiency to reduce N2O. On climate change adaptation, the agricultural adaptation plan, with a road map until 2025, looks at managing climate risk (e.g. new variety development, infrastructure against increasing natural disasters) but also envisions taking advantage of positive opportunities that may arise.

Japan has seventeen Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) in force, covering Singapore, Mexico, Malaysia, Chile, Thailand, Indonesia, Brunei Darussalam, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Philippines, Switzerland, Viet Nam, India, Peru, Australia, Mongolia, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the European Union.4 These EPAs have accelerated structural reforms in the agricultural sector to counter market competitions. Such efforts include the implementation of “the Comprehensive TPP related Policy Framework”, which provides various programmes to increase productivity of the sector. Japan is engaged in several other EPA negotiations including with Colombia and Turkey, and plurilateral negotiations such as the FTA among China, Japan and Korea, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Domestic policy developments in 2019-20

The Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, which sets Japan’s agricultural policy direction for the next 10 years, was revised in March 2020. Facing a multitude of challenges such as the decrease of farming population and the new trade environments by the implementation of large-scale trade agreements, the plan aims to strengthen the agricultural production base regardless of farm size or its hilly and mountainous condition. The emphasis is also placed on sustaining rural areas. The Basic Plan maintains its goal of increasing the country’s calorie-based food self-sufficiency rate to 45% by fiscal year 2030. Additionally, the Basic Plan addresses responses related to the COVID-19, such as boosting domestic demands for agricultural products and providing necessary information to consumers.

Across all of the sectors, Japan accelerates the practical application of labour-saving technology using artificial intelligence and robots to resolve the growing labour shortage. The agricultural sector also benefits from advances in these technologies. Aiming to enable almost all business-oriented farmers to utilise data in their workflow by 2025, the government began supporting the incorporation of current leading technologies into agricultural production. With the involvement of producers, municipal governments, the national agriculture research institute, and private sector actors, 121 production sites conduct this smart agriculture project.

In 2019, the government formulated a new programme to promote the implementation of new technologies at agricultural production sites, aiming to further advance the utilisation of smart agriculture technologies. In particular, the programme conducts research and development (R&D) on smart agriculture technologies in various farming fields and builds a consultation system for farmers on smart agriculture so that these technologies can be sufficiently implemented.

The Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Products and Food Export Facilitation Act came into force in April 2020. With the new Act, the government aims to facilitate the exports of agricultural, food, forestry and fishery products. Previously, multiple ministries oversaw export policies for these products – e.g. the Ministry of Health, and Labour and Welfare issued a sanitary certificate necessary for export, while the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) negotiated food safety requirements set by import countries. The new Act streamlines and centralises the management of the operations related to these exports at the headquarters established within MAFF. The new structure seeks to clarify the responsibilities within government agencies and expedite the administrative process of export.

A series of large-scale natural disasters hit Japan in 2019. Typhoons, heavy rains, flooding, landslides, and earthquakes all caused major damages to the agricultural sector. The damages in the agricultural, forestry and fisheries sectors from these disasters are reported at JPY 460.2 billion (USD 4.2 billion). The government earmarked supplementary budgets of JPY 105.4 billion (USD 1 billion) for the restoration of these sectors, mostly used for the recovery of farmland and agricultural facilities as well as landslides and road destructions in the mountains.

Japan amended the Fertilizer Regulation Act in 2019. This amendment allows the production and sales of fertilisers that combine chemical fertilisers with compost of livestock manure or soil improvement additives. It also provides standards for raw materials to be used for producing fertilisers. These standards promote the utilisation of industrial by-products and compost in fertilisers, and also aim to improve the safety of these fertilisers. Furthermore, while previous labelling standards were focusing only on indicating raw materials and the nutrient contents, the amendment provides for additional labelling standards on the effects and features of fertilisers. The amended act aims to enable farmers to attain efficient management of soil and to contribute to the improvement of soil fertility.

The Act on the Promotion of Food Loss and Waste Reduction came into force on 1 October 2019. The main purpose of the Act is to promote food loss and waste reduction as a national movement through the collaboration of various entities, including the national and local governments, businesses, and consumers. The Act prescribes the responsibilities of the national and local governments to raise public awareness on food loss and waste, and support food-related business operators and related entities. In particular, the Act obligates the national government to establish a basic policy (by Cabinet decision) on reducing food loss and waste, and local governments are obliged to make their best efforts to establish their basic plans, based on the basic policy. In addition, the Act declares October as a promotion month for reducing food loss and waste to enhance understanding and interest among the public.

In October 2019, Japan raised its consumption tax for the first time in five and a half years. The tax rate was increased from 8% to 10% to secure stable revenue for the national social security system that benefits. For the first time, the government also introduced a reduced tax rate system. While most goods and services are subject to the increased tax rate, the consumption tax rate for food and beverages other than liquor and eating-out services, is set at 8% in order to lessen the burden especially on lower income households.

Trade policy developments in 2019-20

Japan’s tariff-rate-quotas continued to be under-filled in fiscal year (FY) 2019 (April 2019-March 2020) for some products, including butter and butter oil, prepared whey for infant formula, and skimmed milk powder for school lunches. Japan issued special safeguard measures in FY 2019 for some products, including butter and inulin. Japan decided to import up to 20 000 tonnes of butter under state trading in FY 2020 in order to meet domestic demand.

The Japan–European Union Economic Partnership Agreement entered into force on 1 February 2019 after more than four years of negotiations. The agreement substantially reduces tariffs and trade barriers for both parties. Overall, Japan eliminates duties on about 94%5 of imports from the European Union and the European Union liberalises 99% of tariff lines once fully in place after 21 years. The agreement is set to eliminate tariffs on about 82% of the EU’s agro-food products exported to Japan. Duties on most remaining products are to be reduced over time, while Japan has opened TRQs for others. EU’s tariffs on beef, tea, alcoholic beverages and other priority products from Japan are to be eliminated, most upon the agreement’s entry into force. Tariffs for rice remained unchanged for both parties. Aside from market access, the agreement establishes rules on the protection of more than 50 Japanese Geographical Indications (GIs) for wines, spirits and agricultural products in the EU, and 200 EU GIs in Japan.

About five months into the negotiations, Japan and the United States reached a bilateral trade agreement in September 2019 and the agreement entered into force in January 2020. Under the Trade Agreement between Japan and the United States of America, Japan sets to eliminate or reduce customs duties and mark-ups on main agricultural imports from the United States including beef, pork and wheat, while maintaining tariffs for its rice. The United States eliminates or reduces customs duties on 42 agricultural products such as cut flowers and yams (nagaimo) which Japan has an interest to export into the United States.

Specifically, Japan provides staged tariff reductions on US beef from 38.5% to 9% in fifteen years. On pork, Japan eliminates the 4.3% ad valorem duty, and reduces the specific duty (from JPY 482 to JPY 50 (USD 4.4 to USD 0.5) per kilo) both over nine years. The mark-up (price differences collected by the government when importing and selling) on US wheat is reduced by 45% by 2026, and a US specific quota is set at 120 000 tonnes increased to 150 000 tonnes in five years. The agreement provides for the use of safeguards for surges in imports of beef, pork, processed pork, whey, oranges and race horses.

References

[6] FAO (2020), FAOSTAT (major import partners), http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TM (accessed on 3 April 2020).

[9] FAO (2015), World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, update 2015 International soil classificationn system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. World Soil Resources Reports No. 106, http://www.fao.org/3/i3794en/I3794en.pdf.

[10] GIO (2019), Japan’s GHG emissions data (FY1990ー2017, Final figures), http://www-gio.nies.go.jp/aboutghg/nir/nir-j.html#b.

[2] MAFF (2020), Agricultural structure statistics 2019, https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/noukou/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[13] MAFF (2020), Information on Covid-19, https://www.maff.go.jp/j/saigai/n_coronavirus/index.html.

[7] MAFF (2019), agricultural land (cultivated and planted) statistics, https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00500215&tstat=000001013427&cycle=7&year=20180&month=0&tclass1=000001032270&tclass2=000001032271&tclass3=000001125355.

[3] MAFF (2019), Agricultural Structure Statistics 2019 (Japanese), https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/noukou/index.html#r.

[1] MAFF (2019), Arable land area as of 15 July 2019, https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/sakumotu/menseki/index.html#r.

[5] MAFF (2019), The food self-sufficiency rate FY 2018 (Japanese), https://www.maff.go.jp/j/press/kanbo/anpo/attach/pdf/190806-2.pdf.

[11] MLIT (2019), Water resources in Japan, http://www.mlit.go.jp/mizukokudo/mizsei/mizukokudo_mizsei_tk2_000014.html.

[4] OECD (2019), Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Japan, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/92b8dff7-en.

[8] Shindo, J. (2012), “Changes in the nitrogen balance in agricultural land in Japan and 12 other Asian Countries based on a nitrogen-flow model”, Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, Vol. 94/1, pp. 47-61, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-012-9525-x.

[12] WTO (2019), World Tariff Profiles 2019, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tariff_profiles19_e.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Source of the information on policy responses relative to the COVID-19 outbreak: (MAFF, 2020[13]).

← 2. Simple average MFN applied.

← 3. Public Corporations for Farmland Consolidation to Core Farmers through Renting and Subleasing.

← 4. Order according to the effectuation date of agreements.

← 5. Based on the number of liberalised tariff lines.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/928181a8-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.