1. Key policy insights

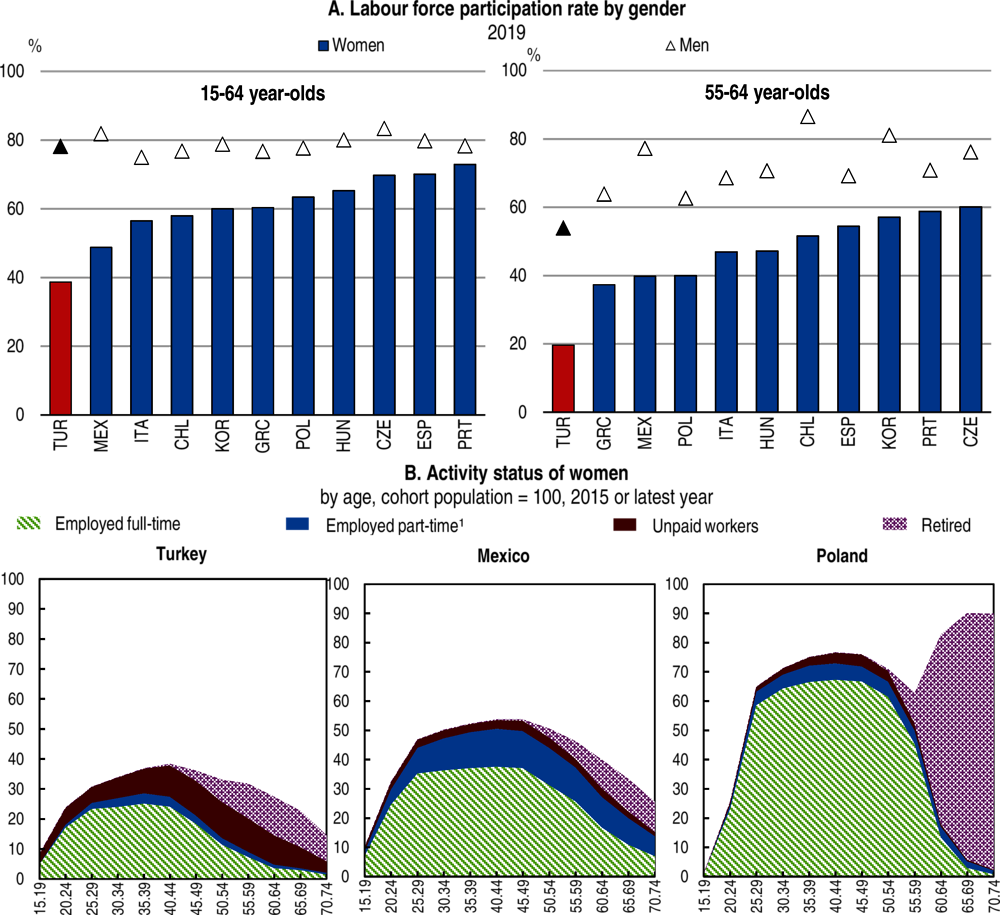

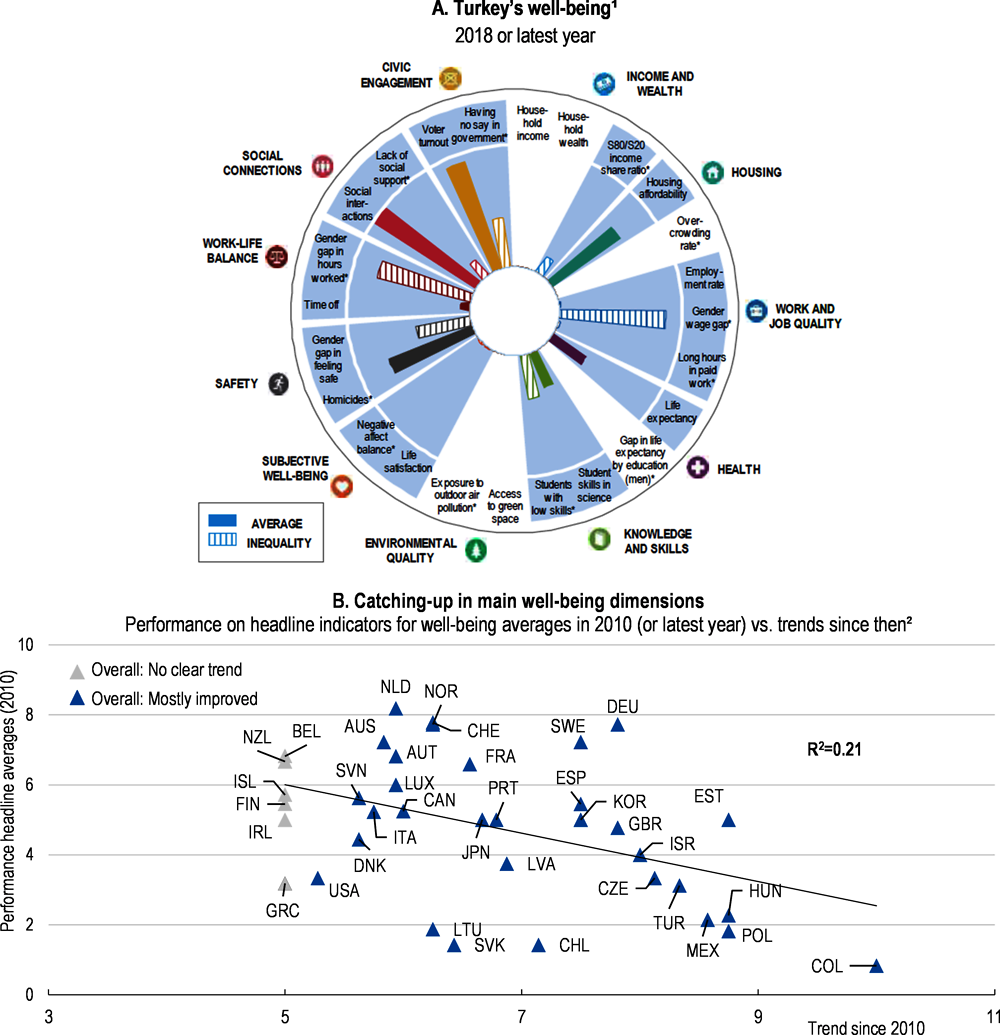

After only partly recovering from a sharp macroeconomic correction in the summer of 2018, Turkey was hit by the COVID-19 shock in spring 2020, slightly later than other countries in the region. While Turkey managed to contain the number of contagion cases relatively effectively in the initial phase, domestic containment measures and the drop in tourism had a severe effect on the economy. Activity contracted, employment fell from an already depressed level after the 2018 shock, and pressures mounted on well-being and social cohesion. Some population groups have suffered more, including informal workers, women, refugees and the youth.

Following the relaxation of containment measures in June and a strong government stimulus, activity rebounded strongly throughout the Summer. Quarter-on-quarter growth was very strong in the third quarter. However, this was followed by a sharp escalation of infections in the Fall, together with rising numbers of fatalities. Pressures on the health system increased again and new confinement measures were introduced from November. Given the elevated uncertainty about the global and local trajectory of the pandemic, and the rapidly increased debt burdens of households and businesses, the recovery is projected to be more gradual than after the previous macroeconomic shocks.

The dynamism of the Turkish business sector has been an asset during the crisis. It has adapted relatively rapidly to the new circumstances, catered to basic domestic needs, and seized new opportunities from international markets. Still, the path of the economy through the pandemic is strewn with strains. They encompass special macroeconomic challenges which arose from the high dependence of the growth pattern on domestic demand and foreign savings, while investor confidence in price stability and policy predictability could not be consolidated and risk premia and exchange rate volatility remained very high. Policy support during the pandemic should be provided in a transparent, predictable and stable macroeconomic framework and without further worsening the external deficit and inflationary pressures. Additional challenges arise from business sector structures, where many firms have small size, weak balance sheets, a narrow equity base, and limited capacity to weather a protracted slowdown and to resume long-term capital formation once a recovery takes hold.

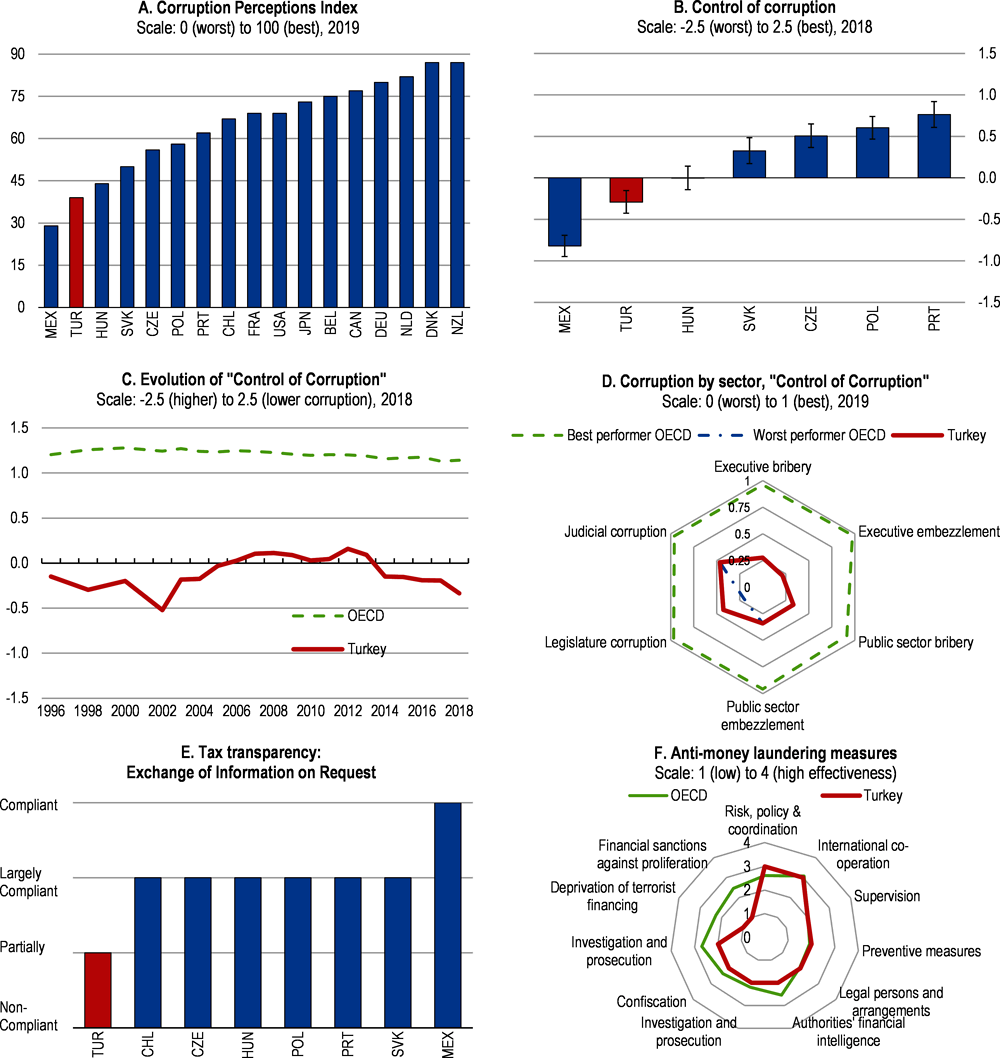

High productivity firms creating good quality jobs remain indeed a minority in the Turkish economy. The largest parts of the business sector still rely on informal or semi-formal practices in employment, corporate governance, financial transparency and regulatory and tax compliance. These appear to have regained ground after the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ensuring compliance by all businesses with laws and regulations, which should themselves be modernised, will be crucial for their gaining full access to state-of-the-art capital, know-how and technological resources from domestic and international markets, on the way out of the COVID-19 shock and beyond.

This chapter reviews Turkey’s short- and medium-term general economic policy priorities. The subsequent chapter documents how structural change in the business sector can drive post-pandemic growth and social cohesion. The key messages of the Survey are:

After initial successes against the pandemic and a strong economic rebound, Turkey faces a second wave which is putting pressure on the health system, the recovery, the viability of many businesses, employment and social cohesion. This invites the continuation of a supportive policy stance.

Public finances continue to offer room for government support to households and businesses most in need, but this should be provided under a more transparent and predictable fiscal, quasi-fiscal, monetary and financial policy framework. Shortcomings in this framework hindered market confidence in the early phase of the pandemic, creating tensions in risk premia, capital movements and exchange rates which complicated policy responses to the crisis.

New demands and opportunities have emerged for structural change in the business sector. A reform package would help accelerate the ever more needed formalisation of business activities, re-capitalisation of balance sheets, strengthening of investment capacity and digital upgrading of firms of all sizes and sectors. Conditions are now more supportive for constructive social dialogue and participatory adjustments at firm level.

Targeted lockdowns and health policy initiatives were initially effective but there is a second wave

The pandemic hit Turkey in the second half of March and diffused at a fast rate. Yet, the number of cases and deaths remained relatively low by international comparison taking into account the size of the population (Figure 1.1). The number of COVID-19 cases peaked at the end of April. The health system faced the pandemic with a low number of physicians and hospital beds per capita (an average of 1.8 physicians and 2.9 hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants, against OECD averages of 3.4 and 4.7), but was well prepared to public health emergencies, thanks, notably, to a strong intensive care infrastructure (with 43.500 intensive care units for a population of 83.4 million). The authorities put in place targeted lockdowns and curfews dedicated to specific age groups, towns and neighbourhoods. International and domestic passenger traffic was entirely shut down. Sectors closed by administrative decision were narrow in international comparison, and not more than 40% of the population was formally confined - except during temporary curfews over weekends and public holidays. Despite this, many activities, particularly those requiring face-to-face interactions, slowed strongly as individuals chose to minimise their health risks.

Intense testing and tracing activities conducted in line with advice from a Scientific Advisory Board were enforced, although there is still room for convergence with international best practices in this area (Figure 1.1, Panel C). According to the OECD Health Policy Tracker, all public and private hospitals were declared ‘pandemic hospitals’ at the height of the crisis, all non-vital elected surgeries were postponed, more than 30 000 additional health professionals were recruited and two new specialised hospitals were constructed in Istanbul - in addition to the large city hospitals recently put in service in many provinces. The existing network of family doctors monitored daily all cases with symptoms (OECD, 2020c). All tests and treatments were financed by the social security administration. Health professionals showed an abnegation and commitment welcomed in all parts of the population (14% of all contagions concerned health workers by August). Masks were made obligatory in all public spaces, and were made available at low cost from the early stages of the pandemic. Saturation was avoided in intensive care units. As in other countries, medical professionals were met with some difficulties in accessing high quality protection gear in certain regions and hospitals (Turkish Medical Association, 2020a), but the number of cases and fatalities were reined in successfully in international comparison in this first phase. Covid-19 vaccine research activities are continuing in national universities and research centers. After a gradual re-opening of the economy from early June (the so-called “return to normal life” measures, which implied a relaxation of lockdowns, re-opening of public spaces, and easing restrictionis of domestic and international passenger transportation), and due to the population’s laxed attitude towards physical distancing, Turkey experienced a steady rise in new cases in summer months (Figure 1.1). The disease spread from densely-populated urban centres to smaller towns and villages. According to one estimate, the coefficient of contagion R0 fell below the critical threshold of 1 in big metropolitan centres by mid-July, but soared above 1 in less densely-populated regions, which was then followed by an upsurge of the coefficient across the entire country (EpiForecasts, 2020).

Available data confirm the vigour of the second wave. After an intermediary peak in mid-September, which proved to be temporary, symptomatic cases and fatalities soared from November, surpassing their April level by a strong margin. The Ministry of Health stated in October that “confirmed COVID-19 cases” were reported according to a narrower definition than recommended by the World Health Organisation, including cases with symptoms but excluding thoses without symptoms (Reuters, 2020a). The Ministry started to publish the number of all confirmed cases from 25 November (Reuters, 2020b). Fatalities continue to be reported according to local definitions. It is essential to uphold confidence in official information on the spread of the pandemic.

In response, a range of measures including changes in school opening plans, restrictions on public events and public space activities, and targeted confinements were introduced. Policies continue to focus on testing, tracing and tracking activities and stronger enforcement of physical distancing. Regional containment measures are managed by provincial authorities. The government introduced a national curfew on certain time slices of the week-ends starting from mid-November. It also extended the curfews already in force for people above 65 and for youth below 20 (with the exception of young workers) to longer time periods.

The new circumstances have serious implications for education. The opening of schools and universities, initially planned for end-September, was postponed for the large part of courses and classes (underpinning the pick-up in Turkey’s policy stringency indexes, Figure 1.1), amid authorities’ efforts to re-open them as quickly as possible. A decision to close them until the end of the year was nonetheless taken on 17 November and was extended to kindergarten on 1 December. The bulk of primary, secondary and tertiary education activities shifted to on-line learning. The impact of school closures on parents’ capacity to resume work, and, more fundamentally, for the quality of education for both school and university students raises important challenges as in all OECD countries (BBC News, 2020a).

Research by the Ministry of National Education (“Evaluation of Distance Learning Activities during the Pandemic”) documented the experience of students, teachers, school principals and parents with on-line education in 2020. More than 800.000 students were surveyed, 11% responded that they were lacking the necessary terminal equipment, 6.7% home or mobile internet access, and around 15% inadequate internet connection (parents’ replies confirmed these proportions). A smaller survey centred on internet access in the Istanbul region (before the creation of on-line support centers and the distribution of free tablet computers by the Ministry, see below) found that 40% of low-income families in the region had no internet access and 58% had no laptop computer (Istanbul Buyuksehir Belediyesi, 2020).

The Ministry took initiatives to mitigate disparities in education access and quality during the pandemic. This included the distribution of 500,000 tablet computers free of charge to disadvantaged children, together with free mobile internet access. Close to 13.900 digital education network support centres and 162 mobile support centers were created through the country, including in schools in disadvantaged areas where students from low-income families could engage in interactive and personalised computer-based learning (EBA, 2020). Guidelines for infection prevention and containment were published for schools and were enforced with trained inspectors. As in all OECD countries, gaps nevertheless emerged between teaching resources and methods between different types of schools. Public schools relied on dedicated television channels (three channels were activated) and on on-line education platforms and live classes. The Ministry agreed with GSM operators to provide cellular subscribers free access to on-line education platforms. The majority of parents found the technical infrastructure of on-line education effective, even if difficulties in internet access remained in certain areas, while 54% were satisfied with its planning. A number of private schools with strong material resources and class-size conditions could implement their own on-line teaching methods. Differences in on-line teaching practices and intensity emerged also between universities. These disparities, if they persist, risk amplifying the social gaps in the quality of education (OECD, 2019a). High-quality studies evaluating the impact of these different streams of on-line teaching on the academic proficiency of students may be required in the future to develop follow-up policies.

Strong policy stimulus triggered a vigorous rebound which faced headwinds

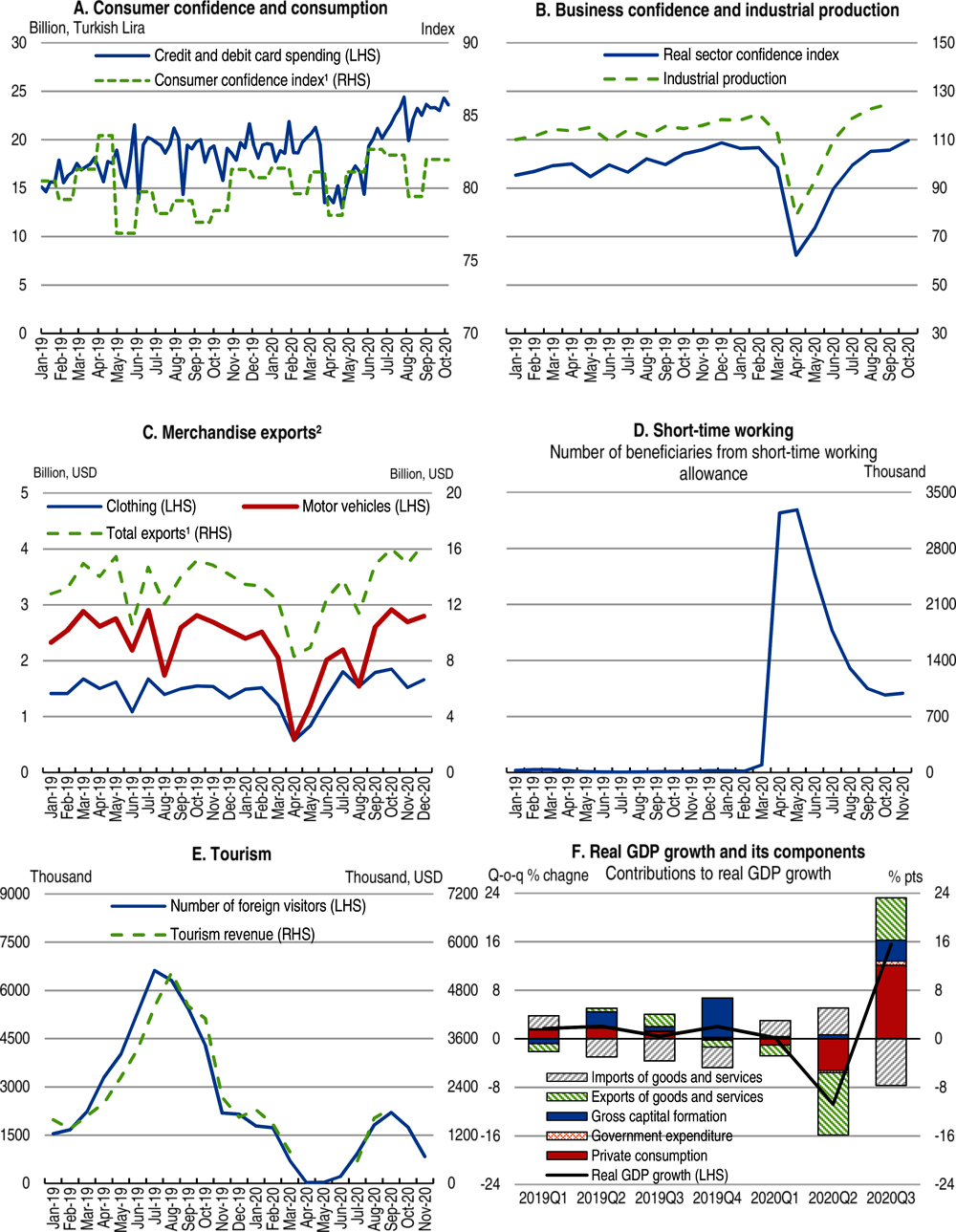

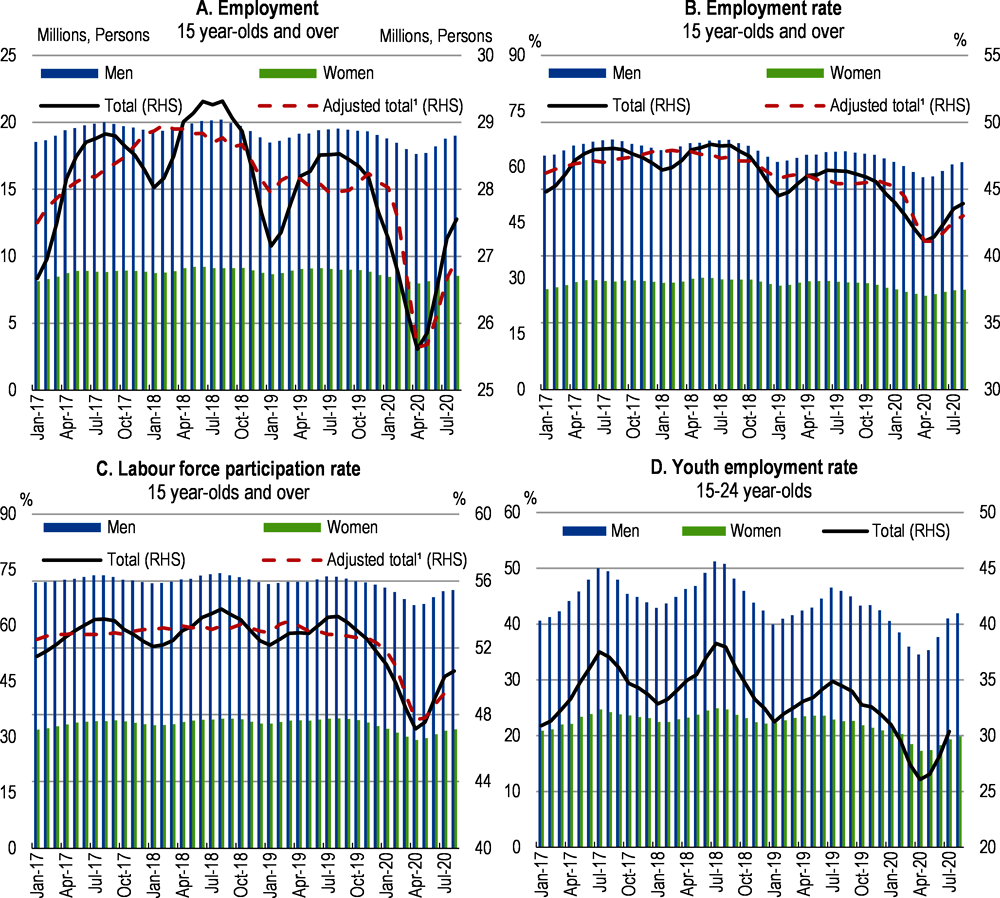

The impact of the pandemic on the economy unfolded later than in other countries but was sharp. Activity contracted strongly in April as people chose to limit their interactions, despite limited official restrictions, and external demand declined. Consumption, production and exports all shrank (Figure 1.2). Labour demand fell but the existing short-time work scheme and the new furlough arrangement for unpaid leaves helped to contain job losses in the formal sector. Output fell by 11% in the second quarter of 2020, before recovering strongly in the third quarter.

Informal workers and the self employed were hit the most, as many make their living from contact-intensive services such as retail trade, street catering and public transportation. The high share of these workers in total employment kept the potential for remote working low (at around 20%, against 30 to 40% in other OECD countries (OECD, 2020e)). These groups are not covered by employment-related social safety nets and received only ad hoc cash support. Aggregate household incomes and confidence took a strong hit, reflecting in a sharp fall of private consumption (by more than 25% in April over the previous month according to credit card expenditures). Tourism was hit particularly hard (Figure 1.2 Panel E). This sector employs 7% of all workers, generates demand for a wide range of upstream products and services, especially in certain regions, and accounts for 14% of total exports. Consequently, local and regional demand fell twice as rapidly in touristic regions as in others (Akcigit and Akgunduz, 2020). It is estimated that an expected two-thirds decline in tourism output may have reduced aggregate GDP by about 4% in 2020 (Mehr News Agency, 2020).

Policymakers reacted with a broad set of measures. In the first phase, the fiscal package was relatively limited. The “Economic Stability Shield Programme” announced on 16 March 2020 included 2.1% of GDP of fiscal commitments, including many temporary tax deferrals. The package contained 21 measures accompanied by broad financial and monetary supports (Box 1.1). Emergency aid to households helped avoid situations of extreme distress, but compensated only part of the losses in living standards. Turkey also introduced a series of trade restriction measures (Box 1.1).

Concessional credits to households and businesses played the central role in efforts to uphold demand. They were extended mainly by public banks, but also by private banks incentivised by government guarantees. This increased the share of quasi-fiscal (“below-the-line”) relative to fiscal (“above-the-line”) expenditures. According to the IMF Fiscal Monitor database on specific COVID-19 measures, this share in Turkey was the highest among all countries monitored (Gaspar and Gopinath, 2020).Three public banks were recapitalised.

On 18 March 2020, the authorities announced a TRY 100 billion (2.1% of GDP) Economic Stability Shield Programme. Complementary measures were added in the following months, and the total amount of measures reached TRY 503.4 billion (10.6% of GDP) as of mid-November. This Box reviews the main measures. Further details are available on OECD’s COVID-19 policy tracker (OECD, 2020c).

Social transfers

From mid-March, the minimum monthly old-age pension was raised from TRY 1.000 to 1.500 (USD 230 on the basis of exchange-rates at the time of announcement).

Families in need received a one-off cash transfer of TRY 1000 (USD 154) per family. By the end of October, 6.3 million families had received the allowance. This transfer was provided as additional support to households receiving other social aid.

Households in need but not eligible for the standard allowance applied for ad hoc support from a new National Solidarity Fund. Public enterprises and private firms were invited to contribute. Around 0.05% of GDP was re-distributed through this fund by September 2020.

Cash and in-kind support was also offered by municipalities. Several municipalities launched local schemes permitting to cancel public utility (water and natural gas) and grocery debts of insolvent households. Private benefactors anonymously closed their accounts payable. These schemes benefitted millions of families.

Concessional credits to businesses and households

In mid-March, the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BRSA): 1) asked banks to postpone their customers’ principal and interest payments for at least three months upon request; 2) extended the delay for classifying a loan as non-performing from 90 to 180 days (in keeping with international recommendations); 3) introduced forbearance measures for the measurement of banks’ Capital Adequacy Ratio; 4) increased the Loan-to-Value Ratio on mortgage loans.

From mid-March, three main public banks (Ziraat, Halkbank and Vakif) offered all businesses concessional working capital loans (at 36 months maturity, 6 month grace period and a low 7.5% interest rate), conditional on their preserving their current employment level.

Public banks offered tradesmen and craftsmen a concessional credit line (at 36 months maturity and 4.5% interest rate). A "craft-and-trade credit card" was also made available under an individual credit line of TRY 25.000 (USD 4.000 at the time of announcement).

Late March, principal and interest payments on SME Bank’s (Halkbank’s) subsidised credits to tradesmen and craftsmen were postponed for three months. Late April, principal and interest payments on Agricultural Bank’s subsidised credits to agricultural producers were postponed for six months.

Public banks started to offer to low-income households (earning less than TRY 5000 – USD 770 per month) “basic need support credits” of up to TRY 10.000 (USD 1.500), with up to 3 year maturity, at a concessional interest rate of 6%.

On 30 March, the Government Credit Guarantee Fund (KGF) increased its total limit for loan guarantees from TRY 25 billion to TRY 50 billion (USD 7.7 billion). It guaranteed general-purpose loans to individuals for the first time. As a result, total loan leveraging capacity of KGF reached TRY 500 billion (14% of 2019 GDP). The ensuing government guarantee liabilities are however capped at 1.4% of GDP.

In April, BRSA introduced an “Asset Ratio” applicable to most banks (except development banks and small banks) to stimulate their credits. Its formulae incited banks to fund new lending from non-deposit sources and/or invest in government bonds. By the end of May the ratio was revised to stimulate longer term loans. In August and September it was revised again to scale-down its expansionary impact. Its phasing out by 31 December 2020 was announced in November (see Box 1.4 for details on the operation of this ratio) .

Early May, the Sovereign Wealth Fund (TVF) injected TRY 21 billion (USD 2.8bn) of additional capital into three public banks enganged in COVID-19 measures (Ziraat, Halkbank and Vakifbank)

At the end of May, these public banks launched an additional set of concessional loan packages to support purchases of domestically produced cars, white goods and other consumer durables. These loans funded also house purchases and domestic holidays.

In June, BRSA increased the upper limit of instalment numbers for credit card purchases from airlines, travel agencies and hotels from 12 to 18 months to stimulate demand for domestic travel and tourism.

In June, the Central Bank (CBRT) introduced a new programme of "Advance Loans Against Investment Commitment". This finances investments that will “reduce imports, boost exports and support sustainable growth” via the recently re-structured Investment and Development Bank of Turkey. Loans are extended with a maximum maturity of 10 year and with an interest rate 150 basis points below the policy interest rate.

Late July, the SME bank (Halkbank) postponed for three months, all capital and interest reimbursements overdue by trademen and craftsmen.

In mid-October, Turkish Banks Association launched a new credit line for tourism firms and their suppliers (“Tourism Support Package”) to finance the wages, rents, and other fixed costs of these enterprises. TRY 10 billlion is made available, to be distributed by 15 banks undergovernment guarantee.

A similar package was introduced in mid-October for SMEs, to help finance their wages, rents and other fixed costs (“Micro Enterprises Support Package”). An envelope of TRY 10 billion will be distributed by three public banks under government guarantee (Ziraat Bank, Halk Bank and Vakifbank).

Monetary support to activity

In mid-March, Turkey’s Central Bank (CBRT) lowered its main policy rate (the one-week repo rate) from 10.75% to 9.75%. It reduced it further to 8.75% on 22 April and to 8.25% on 21 May.

At the end of March, CBRT offered direct liquidity support through 1) an extension of its limits for open market operations on government securities, 2) an extension of the securities accepted as collateral in transactions with banks, 3) an extension of liquidity facilities for banks “for uninterrupted credit flows to businesses”, and 4) an extension of the volume and maturity of its traditional export credits - 70% of this extension is earmarked for SMEs.

In mid-April, CBRT increased its limit for open market operations on government securities from 5% to 10% of its balance sheet.

Early June, it earmarked one third of its total export credit portfolio for long-term investment credits.

Turkish Eximbank extended the repayment terms of its existing rediscount credits for exporters by three to six months.

A new Inventory Financing Package by Turkish Eximbank offered low-interest loans to exporters “whose stocks increased due to low demand and canceled orders”.

The maximum specified maturity limit of rediscount credits for exporters were further extended.

Preserving employment links

Eligibility conditions for the existing Short-Time Working Scheme (which compensates 60% of the earnings lost due to shorter work hours) were eased. The requirement of 600 days of contribution was reduced to 450 days, and the need for a valid employment contract in the last 120 days was reduced to 60 days. To be eligible firms should commit not to reduce their employment level. By early November, 3.6 million beneficiaries were paid 21.8 billion TRY under this scheme (Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services of Turkey, 2020). The application period of this scheme was subsequently extended to 31 December 2020.

The compensatory working period (the re-balancing period for overtime work) was increased from two to four months.

In mid-April, the Parliament adopted a new law on unpaid leaves (furloughs). A fixed monthly allowance of TRY 1170 (USD 170, the floor of unemployment insurance compensation) is granted to furloughed workers. Employers were given discretion in authorising unpaid leaves, in turn they were prohibited from firing any workers during the period the law was in force (it is in force until 17 January 2021 and The President is authorised to prolong it to until 31 July 2021). The workers affected bear nonetheless an income loss compared to their regular earnings. By end-October, 2.1 million beneficiaries were paid around TRY 5.1 billion under this scheme.

From mid-July, a ‘normalisation incentive’ was offered to firms exiting the short-time working scheme. They were exempt from employer and employee social security contributions for six months. By early November, , work contracts of 2.1 million employees were ‘normalised’ via this arrangement. The implementation period of was subsequently extended to 30 June 2021.

Trade Protection

From mid-April, additional customs duties of 2 to 50% were applied to a range of goods, with the goal of “supporting domestic industries adversely affected by the COVID-19 shock”. Resulting net duty rates do not exceed Turkey’s notified World Trade Organisation bound rates. They were to be cut by October, this was subsequently postponed to end-2020.

The list of the products was widened in steps. Around 5000 product groups in total were included (including game consoles, home textiles, white goods, consumer durables, construction materials, industrial machinery, harvesting machinery, textile machinery, sugar confectionery, cocoa powder, chocolate, biscuits, etc.). Surcharge rates gravitate around 17%.

Imports from countries with which Turkey has free trade agreements (FTAs) were exempted. This concerns notably imports from the EU. About 57% of the products subject to surcharges are imported from the EU and other FTA countries, 43% of them are imported from other countries and are affected (including imports from China, India, Japan, Russia and the United States).

Activity rebounded and gained momentum through summer. Credit card spending recovered its pre-shock level in July. House, car and other consumer durable sales, fostered by loan packages, grew sharply. House sales rose to 125% of their level of a year ago, with house prices up by 25%, and even larger increases in certain regions (CBRT, 2020a). The seasonally adjusted PMI index - the reference indicator of business sentiment in Turkey- jumped from a depressed score of 33.4 in April to 56.9 in July (its highest level since March 2011), before declining to 52.8 in September and rebounding to 53.9 in October. Short-time work applications fell, and job vacancy announcements increased. Despite the fall of energy prices, and a still large output gap, inflation responded to domestic demand, stayed close to 12% until October and soared to 14% in November and 14.60% in December.

Exports, despite the weakness of traditional markets in Europe, improved faster than expected. Merchandise exports rebounded by 34% q-o-q in the third quarter of 2020 and reached an all-times high in December. The depreciation of the Lira and the diversification of markets by manufacturers helped. The rebound of industrial activity in Germany - Turkey’s main international value chain customer - played a positive role. Among the main export items, motor vehicles recovered by mid-summer, with also strong growth for textiles and clothing, chemicals and steel products. Manufacturers were active in pandemic-related markets: exports of masks, protective gears and health equipments (including a respiratory assistance device developed by a joint-venture of domestic firms) increased by a total of 530 % in the first half of the year over the same period of 2019.

The upturn was more subdued in services. The traditionally strong correlation between manufacturing and service confidence indexes was broken (Sameks, 2020). Public space activities, including restaurants, leisure services and public transportation stayed frail. E-commerce partially substituted to traditional retail trade. Nearly 40% of Turks were estimated to be using e-commerce at the height of the crisis in April, while the share of on-line sales in total retail sales had approached only 7% at the end of 2019 (Webbrazzi, 2020a and 2020b). The retail franchising association (BMD) reported that nearly 60% of its members achieved a 100% increase in their e-sales between September 2019 and September 2020, but less than one third of them could match their ‘brick-and-mortar’ sale levels of the year ago by the same date (P.A. Turkey, 2020).

Tourism remained very weak, as international visitor numbers fell by 91% over a year ago in July and by 76% in August. Some recovery in domestic tourism, together with Germany, the United Kingdom and Russia freeing up their tourist flows to certain regions of Turkey in August triggered an uptick. However, the United Kingdom reversed their liberalisation decision in late September after the controversy on the accuracy of case reporting, while reservations from Russia (the largest tourism market in terms of visitor numbers) continued to increase (Figure 1.2 Panel E). A study suggested that tourism sector revenues (value added) could fall from USD 34.5 billion in 2019 to USD 15 billion in 2020, before recovering to around USD 25 billion in 2021 (Ernst & Young, 2020a and 2020b).

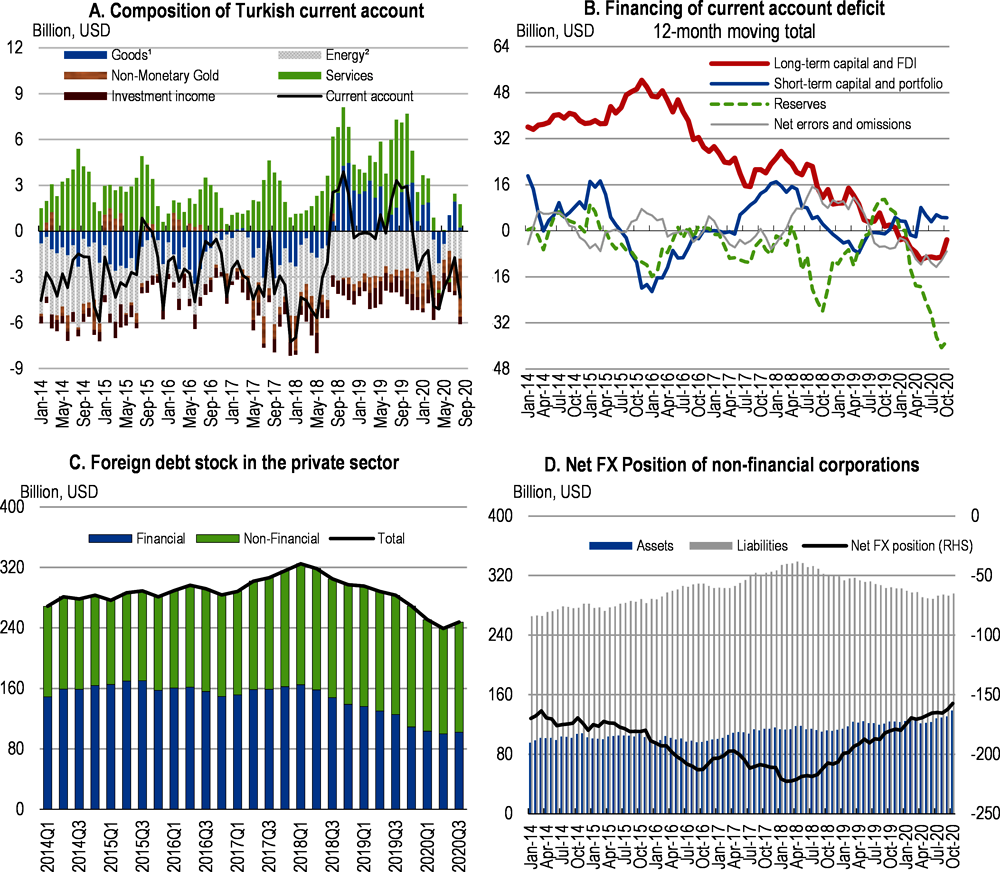

Balance-of-payment strains have been significant

Turkey faced pressures on its already strained external accounts (following, notably, the 2018 financial turmoil as discussed in the thematic chapter) during the COVID-19 crisis. The worsening of the trade balance in the first half of the year was amplified by a surge in gold imports (the favourite saving vehicle of Turkish households in uncertain times) and was compounded by an increase in the interest costs of external debt. The current account deficit to GDP ratio reached 5.1% of GDP in the first quarter of 2020, 8.2% in the second quarter and 4.7% in the third quarter (Figure 1.3).

A deterioration in the financial account compounded the current account deficit. Capital outflows during the crisis were larger than in other emerging countries and lasted longer. Furthermore, foreign capital did not flow back as it did to other emerging markets. This was due, according to available indicators (including risk premia), to a weakening of investor confidence. At the same time, domestic non-financial businesses and banks continued to reduce their external debt as they were doing since the 2018 turmoil. This improved their balance sheets but reduced capital inflows (Figure 1.3 Panels C and D). Finally, the “net errors and omissions” item, which traditionally captures movements in Turkish savings parked abroad and tends to offset foreign financing shortfalls, moved this time in reverse direction. The resulting exchange-rate depreciation was sharp despite policymakers’ efforts to contain it (Figure 1.12 below).

The recovery will be uneven and there are important risks

After a strong upturn in the third quarter of 2020, the recovery is expected to slowdown in the last quarter. Turkey’s output is projected to contract by around -0.2% in 2020. Uncertainty is high on the trajectory of the second wave of the pandemic, on its economic impact, and on future policy developments. Headwinds from the international environment, modest coverage of Turkey’s social safety net and low level of cash transfers, combined with firms’ and households’ increased debt levels, are projected to make the recovery more gradual than in previous post-shock upturns (Table 1.1).

The “New Economy Programme 2021-2023”, published at the end of September, had projected a slightly positive GDP growth of 0.3% in 2020, followed by 5.8% growth in 2021 and 5% growth in 2022 and 2023 (it had mentioned a risk variant for 2020 and 2021, with respectively a -1.5% GDP contraction on the first year and 3.7% growth on the second). The V-shaped baseline was obtained despite a tightening of the fiscal stance starting from the last quarter of 2020, and without additional monetary policy support, thanks to strong projected investment and export growth. Household consumption was expected to recover more gradually.

The New Economy Programme aimed at addressing a number of shortcomings in the business environment, in the entrepreuneurial eco-system, in Turkey’s digital skills and in the flexibility of the labour market. It sought to foster e-trade, to attract more foreign direct investment and to enhance environmental sustainability - specifically by converging with the European Union’s Green Deal. It aimed at increasing Turkey’s share in global value chains. At the same time, it stated that public procurement, the tax system, government-owned financial institutions and business incentives would be mobilised “to reduce import dependence and the imported content of domestic production”. Associated with the trade protection measures introduced during the COVID-19 crisis (which increased Turkish businesses’ cost of participation in global value chains - Dusundere and Koyuncu, 2020 and Akman, 2020) this commitment to reducing import dependence may conflict with the stated goal of deeper international integration of the Turkish economy. These policies can back domestic production and employment in the short-term, but they risk eroding the momentum of integration in global production networks, including in the European single market (Irwin, 2020).

New financial policy measures were introduced along the New Economy Programme. They relaxed partly the restrictions imposed on the operation of financial markets during the COVID-19 shock. First, the “asset ratio” for banks, which compelled them to expand their credits and investments in government securities, was scaled down (subsequently, following additional economic policy measures in November, its phasing out was decided from end-2020). Second, the exchange-transactions tax which penalised currency conversions was reduced. Third, the withholding tax on bank deposits was curtailed. Finally, the regulatory cap which restricted bank’s swap agreements with foreign counterparts was partly relaxed (see Box 1.5 below for more details). These measures were seen as positive steps by domestic and international investors, towards a more conventional operation of financial markets.

Macroeconomic developments ahead will be highly sensitive to the sentiment of domestic and international investors concerning the quality and predictability of fiscal, monetary and financial policy frameworks. The borrowing needs of businesses and households, and, increasingly, of the public sector increase vulnerability to any adverse developments in risk premia and exchange rates.

External funding needs will encompass the financing of the current account, the rolling-over of maturing debt and the need to offset capital outflows. Direct financing needs (net of capital movements) are projected to reach 29.2% of GDP between October 2020 and October 2021. The renewal of maturing trade credits (estimated at USD 54.2 billion) and of the deposits of non-residents (USD 68.7 billion) should be smooth, but rolling-over bank, non-financial business and government debt (USD 58.1 billion) could be costly and demanding. Supportive international financial conditions are expected to facilitae external financing in the short-term, absent new tensions, but high risk premia will put pressure on the long-term sustainability of external debt (as discussed in more detail below).

The macroeconomic outlook is exposed to geopolitical risks. Turkey depends strongly on external trade and on value chain interactions with trade partners, which expose the economy to both downside and upside risks from geo-political developments. Interactions and relations with the EU (48% of Turkish exports in 2019), Near- and Middle-Eastern countries (19% of Turkish exports), the United States (5%%) and Russia (2.2%) are implicated. The opportunities arising from the restructuring of global value chains may be affected. On the other hand, improvements in co-operation prospects with the EU, UK, US and region’s countries could generate new opportunities for Turkish businesses. This applies in particular to the modernisation of the customs union agreement with the EU (Adar et al., 2020).

The Brexit process will have noticeable implications for Turkey, as it is a large exporter to the UK (6 % of Turkish merchandise exports in 2019). A Trade Working Group between the two countries is working on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) to preserve the existing preferential trade conditions to the extent possible. Without such an FTA, key exports such as automotive, machinery, electronics -about 75% of all Turkish exports to the UK- would face tariff increases of 2 to 18%.

Turkey hosts the largest refugee population in the OECD (3.6 million) and this group is particularly affected by the COVID-19 crisis. They face higher health risks due to their living conditions (Deutsche Welle, 2020a). They are also estimated to have faced large employment losses as the majority work informally (Euronews, 2020b). Turkish authorities face therefore additional public health, social and fiscal challenges. Further refugee inflows may occur. Defense- and security-related spending is large, requiring its integration in the medium-term public finance framework. There are also, regrettably, natural disaster risks in the background. Table 1.2 outlines some exceptional events which could lead to additional changes in the outlook. A section below on well-being and social cohesion discusses some of them in more detail.

Policy priorities for containing the pandemic and supporting the recovery

Containing and managing the second wave of the pandemic is obviously key for economic recovery. OECD cross-country insights confirm that good policies pay and various model simulations indicate that, even in the absence of a general application of a vaccine, additional contagions can be reduced. After long-lasting solicitations, the resilience of the hospital system and of health professionals became a challenge in the second wave. Medical associations speak of growing tensions (Ankara Tabip Odasi, 2020), and according to their estimations (not confirmed by the Ministry of Health) there has been a rise in the number of health professionals withdrawing, resigning or on long-term sick leave (BBC News, 2020b). The Ministry of Health declared at the end of October that future resignations of public health personnel will not be accepted (Turkish Medical Association, 2020b) and announced the recruitment of 12.000 additional health professionals to support the existing staff and infrastructure. The testing, tracing and tracking system continues to function intensely (with more than 19.000 teams working full-time throughout the country) but there are concerns about its being overwhelmed by the resurgence of cases. Further efforts will be needed to preserve the preparedness and capacities of the public health infrastructure.

The “return to normal life” measures should be backed with stricter enforcement of physical distancing. Policymakers gained precious experience in fine-tuning lockdowns, selectively confining vulnerable groups, and isolating clusters. The results obtained so far should be re-assessed to identify the most effective procedures. As in all OECD countries, special attention should continue to be paid to the quality and accuracy of tests (OECD, 2020d). The number of cases and fatalities should be monitored and communicated according to international standards.

While a one-size-fits-all support strategy was justified during the first phase of confinements, policy support should now be adapted to the varying conditions of sectors, workers, households, and companies in the second wave. The economy will need to operate under partial confinement for some time as long as an effective vaccine is not widely applied. The reallocation of workers and capital resources to viable activities should be facilitated. Measures which postpone the liquidity strains in the business sector as a whole should be replaced gradually with supports to the post-shock investment capacity of promising firms and activities. The recommended priorities for Turkey’s support policies in the short run include:

Firms and workers in viable activities prevented from operating normally should continue to be supported. This should notably include the large enterprises with high fixed costs in the tourism, hospitality and entertainment sectors, which are crucial for Turkey. All firms receiving public support should be encouraged to prepare for post-pandemic economic conditions, including through re-training of workers and greening of activities.

The gap in employment-related social protection between formal and informal workers should be reduced. For vulnerable families who are not covered by employment-related protections, temporary but predictable allowances rather than irregular one-off transfers should be put in place.

Part of the subsidised and guaranteed loans to households and firms can be replaced with targeted and temporary transfers. For example, the one-off subsidy of TRY 1,000 to the 6 million households at risk of poverty during the COVID-19 crisis can be converted into a temporary but recurrent allowance for a limited period.

For young workers and graduates joining the labour market, further apprenticeship and internship programmes adapted to the post-COVID world should be put in place. Enterprises which benefit from government aids should be encouraged to implement such programmes. A temporary exemption of employer and employee social security costs could be granted to all young workers (in addition to the already existing “easy employer” scheme, which cuts social security contributions for firms employing young workers for less than 10 days per month).

Additional policy measures should ensure that working-age recipients of unemployment benefits and other social help actively look for jobs, and participate effectively to the re-training programmes on offer.

Re-balancing demand and securing external sustainability

To shift to a sustainable growth path after the COVID-19 shock, Turkish economy needs to address its central structural imbalance. Growth is excessively driven by domestic consumption. Every time the economy operates closer to full employment, the current account deficit widens. The resulting dependence on foreign savings has entrenched under generally benign international funding conditions after the global financial crisis. Dynamic growth of domestic consumption under such circumstances typically fuels domestic price pressures, feeding into inflation inertia, triggering episodes of real exchange rate appreciation, and weakening external competitiveness. There have been periodical corrections through balance of payment strains, and related exchange-rate depreciation shocks, most recently in 2018, but they have not delivered durable adjustments. The impact of the 2020 depreciation remains still uncertain.

Policymakers have tried to re-balance the economy periodically but could not surmount the underyling structural challenge. Policy measures aimed at curbing household consumption, lifting-up household savings, and stimulating exports started to pay off (Figure 1.4). However, the re-orientation of the supply side of the economy towards exports has remained too slow and the aggregate supply potential could not expand at a pace fast enough to absorb the trend increase in the labour force (Figure 1.4 Panel D). This dilemma impelled policymakers to periodically revert to domestic demand stimulation, as they have done again after the 2018 shock and during the COVID-19 crisis.

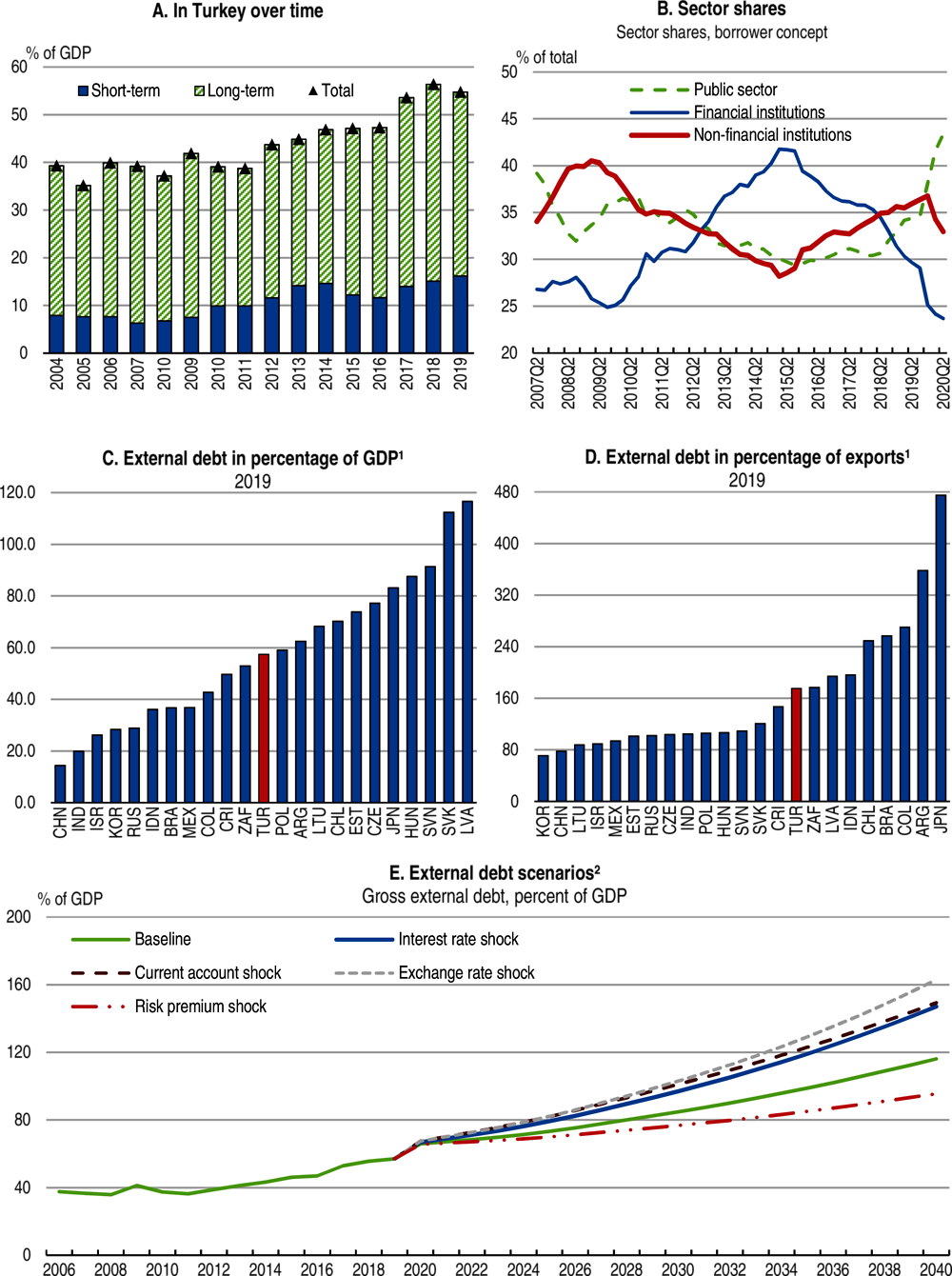

This growth pattern has led to a steady deterioration in Turkey’s net international investment position (with a pause between 2018 and 2020, due to the cyclical impact of growth shocks and to the deleveraging efforts of the private sector). Beyond cyclical effects, the gross external debt stock is on an upward trend. Absent structural change, the external debt-to-GDP ratio will remain a concern for the sustainability of growth (Figure 1.5). As discussed in the thematic chapter, improving productivity and international competitiveness will be crucial for reverting to a sustainable growth trajectory. Fuller use can then be made of the economy’s resources, more and better jobs can be created, and people’s living standards can be raised without falling into stop-and-go cycles.

External sustainability can also be improved by reducing international investors’ risk perceptions. Turkey’s risk premium has risen since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis from an already high level - before declining at the end of 2020. While it had improved thanks to fundamental institutional reforms in the 2000s, permitting an outstanding decline in the economy’s funding costs (Gönenç et al., 2010), risk premia had increased again in the 2010s as policy and institutional uncertainties augmented (Box 1.2). In mid-October 2020, Turkey’s 10-year government borrowing costs in USD reached 6.8% against 5.2% for South Africa, 3.6% for Brasil, 2.8% for Poland and 2.7% for Mexico. Reducing policy and institutional uncertainties would ease investors’ risk perceptions, lessen external funding costs, stimulate non-debt capital inflows and enhance external debt sustainability (Box 1.2).

The discovery of natural gas reserves on Turkey’s Black Sea coast in August 2020 (estimated at 400 cubic meters) may positively affect structural external balances - independently from events in the Eastern Mediterranean. Yearly energy imports equal roughly the structural trade deficit. Natural gas imports gravitate around 45 billion cubic metres, corresponding to nearly 2% of annual GDP (depending on energy prices and on the business cycle). The contribution of the new gas reserve would depend on the pace of exploitation. The authorities estimate that exploitation can start in 2023 and that the energy bill can be reduced by 0.3-0.4% of GDP starting from that year. There are reports that additional reserves may be discovered.

Turkey’s risk premia and external financing costs are very high in international comparison, for both credits and equities (Figure 1.6).

GDP growth, price stability, and the quality of governance institutions are key determinants of Turkey’s risk premia (Gül, 2020a). Technological progress in the business sector helps reduce the risk premium as investigated in earlier OECD Surveys (OECD, 2018; Özmen, 2019). Statistical analyses confirm that high risk premia pass through to lending rates and capital costs (Gül, 2020b).

High risk premia reflect on stock prices, by increasing the discount rate of investors. This is one of the drivers of the differentiation of the price/earnings ratios of listed firms. Panel B of Figure 1.6 provides a proxy of international differences in equity capital costs. In October 2020, the top 100 Turkish firms were trading at a 54% discount from emerging market peers, hinting at very high risk premia (Oyak Yatirim, 2020).

If Turkey could reduce its risk premia to the levels observed in the 2000s, external and internal debt sustainability would improve (Figure 1.5, Panel E and Figure 1.10). More stable funding costs would reduce the risks of balance of payment crises, decrease credit and equity capital costs, and stimulate investment and growth.

Moving to a more transparent and predictable fiscal framework

Turkey went into the COVID-19 crisis with a public deficit of 2.9% of GDP in 2019 and, despite the low level of public debt, extensive off-balance sheet commitments (Figure 1.9). This resulted from the massive government stimulus provided in 2019. At the beginning of 2020, staff expenditures had significantly grown due to job creation in the public sector. Higher borrowing costs had also lifted interest expenditures. In contrast, COVID-19-related on-budget costs had remained relatively limited in the first wave of the pandemic. According to the IMF Fiscal Monitor database, COVID-19-related spending and foregone revenues amounted to about 0.2% of GDP by mid-June 2020. The government has estimated these direct budget costs at 0.7% of GDP by the end of July (including the costs of the short-term working arrangement, the unpaid leave scheme, the additional unemployment insurance payments, and the one-off social support for the families in need).

The mainstay of Turkey’s COVID-19 support policies in the first wave was quasi-fiscal, not directly affecting the net lending of the government (see Box 1.1). Public bank loans and government loan guarantees, and, to a smaller extent, equity injections in financial and non-financial firms formed the backbone of government actions (Figure 1.7). Such ‘below-the-line’ supports amounted to 9.1% of GDP in the first five months of 2020 according to the IMF Fiscal Monitor database, going well beyond the emerging market ‘below-the-line’ average of 2% of GDP.

This distinct support system had distinct impacts on Turkey’s public finances, business and household balance sheets and on the financial system as a whole:

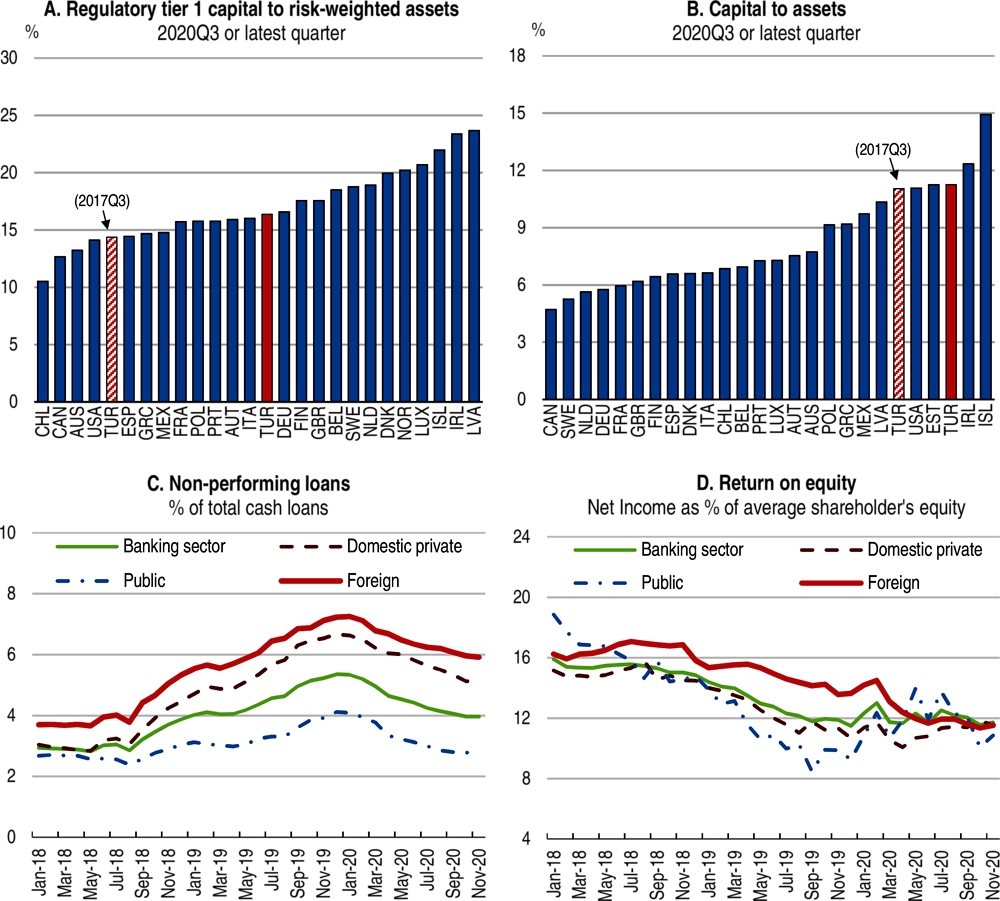

Ultimate impact on public finances. A sizeable share of the quasi-fiscal support offered during the first wave of the COVID-19 shock may turn into explicit fiscal costs. This is expected to result from the social security debt accumulated in the health system (Ministry of Development, 2018), which increased during the pandemic, and from loan defaults and calls on government guarantees. Even if Turkish banks entered the pandemic with, in principle, robust capital structures (Figure 1.8), the system’s non-performing loan (NPL) ratio increased from below 3% in early 2018 to 5.3% in January 2020 (a still low level given the severity of the 2018 shock in international comparison - Ari et al., 2020). It then declined to 4.1% by the end of August 2020, reflecting the fast expansion of new loans, the re-scheduling of existing loans under policy guidance, and the relaxation of loan classification methodologies along international recommendations (there is international consensus on the need to avoid classifying loans as non-performing after the standard 90 days delinquency during the pandemic). In its Financial Stability Report in November 2020, the central bank documented that while non-performing loan ratios improved in Turkish banks between 2019 and 2020 as a result of these restructurings and reclassifications, “loans under close scrutiny” account for around 10% of credit portfolios (CBRT, 2020b). Traditionally, 15% of these loans tend to turn non-performing but this proportion may worsen under demanding circumstances.

The loan classifications that the banking regulator (BRSA) has been implementing since 2019 and according to the latest international standards (IFRS 9) will permit a more refined monitoring of loan quality. The BRSA and The Banks Association of Turkey (TBA) are publishing detailed financial information on bank balance sheets on their websites (on a sectoral basis on the BRSA website and on individual banks on the TBA website) and these reports, with the help of internationally comparable classifications, will enable more refined data driven analyses of bank balance sheets by third-parties in the future. The quarterly external audit reports are also publicly available. Nevertheless there were qualms about the asset quality of some Turkish banks before the pandemic (IMF, 2019; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2020). They were related to the suspected evergreening of bad loans in recent years (IMF, 2019).

The challenge concerning loan quality was amplified after the COVID-19 shock. The policy-stimulated credit growth in 2020, due to its exceptional pace, is expected to have reduced loan quality. The volume of public and private credits increased sharply between March and August 2020 (Figure 1.7). The guarantee provision capacity of the Credit Guarantee Fund was doubled in March 2020 (from TRY 250 billion to TRY 500 billion) and actual loan guarantees increased by 52% between June 2019 and June 2020. A significant share of these loans and guarantees were granted to households, firms and self-employed under financial constraints, which may be expected to continue to face strains during the second wave of the pandemic. While the budgetary impact of the loans extended by the Credit Guarantee Fund is limited to 10% of the outstanding loan amount, and both public and private banks classify and provision for their risky loans under the same standards, current indicators of loan quality, including the non-performing loan ratios, may fall short of highlighting sizeable future contingencies. The potential cost of loan defaults to public banks for public finances should be estimated, including under adverse scenarios.

The recommended Fiscal Policy Report can present this information. The banking regulator as well as independent third-party analysts can contribute to prospective analyses. OECD recommends the publication of asset quality reviews for individual banks and for the banking system as a whole (OECD, 2020n; European Banking Authority, 2020). Turkey is one of the few OECD countries not releasing stress test results for individual banks, out of concern for undue market impacts under limited financial literacy. Even though there is no general requirement with respect to Basel standards on publishing individual banks’ stress tests, disclosures can increase domestic and international confidence in the resilience of the banking sector (BIS, 2018). Cross-country research suggests that such disclosures are welfare-enhancing (OECD, 2020n).

Faced with macroeconomic sustainability concerns in markets, Turkish policymakers scaled down their quasi-fiscal activism from late August. Loan growth moderated, but stayed above historical trends until the very end of the year (Figure 1. 7). Loan conditions were tightened. Interest rates on public banks’ housing credits were, for example, raised from 8.4% in June to 11.3% by mid-summer and to 16-24% by the end of September. Rates on so-called “emergency loans” for households increased from around 15% in June to between 20-30% at the end of September. The banking regulator reduced its regulatory “asset ratio” in two steps, in August and September, to reduce its expansionary impact and, ultimately, phased it out from 31 December 2020.

Debt burdens for businesses and households. Despite starting from a comparatively moderate level in international comparison, total debt accumulation since the onset of the pandemic amplified the risks of debt overhang in many businesses, and of excessive debt leverage in many households. Business debt as a share of GDP had soared before the pandemic, from 35% in 2009 to 69% in 2018 – one of the sharpest increases in the world. It settled at 66% in 2019, after active de-leveraging by businesses following the 2018 financial turmoil and mounted again through 2020. In keeping with the balance sheet analyses of the 2018 OECD Economic Survey of Turkey, young start-ups and medium-sized firms should face the highest risks of debt overhang. Industrial investment will suffer, notably in capital-intensive activities with high digitalisation needs such as tourism (Dünya, 2020) and retail trade. Business bankruptcies, which were adjourned between March and June 2020 will unavoidably grow. They increased by 10% over a year ago in August and an international study projected them to increase by more than 30% in 2021 - alongside a cross-country surge of 35% (KPGM, 2020). Turkey’s high risk premia is affecting adversely the feasibility and cost of financial restructurings.

Household debt was, at first sight, at benign levels in international comparison before the COVID-19 shock – at around 15% of GDP. It will increase during the pandemic as a result of loan-centred supports. It already increased by 33% between January 2019 and September 2020. The OECD Secretariat estimates that it may have reached 20% of GDP by the end of 2020 and a private forecaster projects it at 25% in 2022 (Trading Economics, 2020). This pace of expansion of credits is a source of risk for their quality (Alessi and Detken, 2018). The allocation of credits between different types of households will bear on their macroeconomic and social impact. Low-income households (for whom credits are the main source of income replacement to finance basic needs) will be constrained by excessive leverage. In contrast, households sheltered by social safety nets can use the subsidised loan packages for more discretionary purchases and can continue to borrow.

Systemic impacts on the financial system. The underlying developments in the financial system were accelerated by the COVID-19 shock. The share of government-owned financial institutions expanded, furthering a development that started in 2018. Guidances and regulations related to capital allocation, including those introduced as macro-prudential tools, have expanded. This included a constraining “asset ratio” for banks which penalised them if their pace of credit extension and security purchases fell below targeted rates (BRSA, 2020a). In the context of the monetary and financial policies introduced from November 2020 this regulation is repealed from 31 December 2020.

Banking has a central role in the Turkish economy (the correlation between credits and the business cycle is the highest among all countries reviewed by the Institute of International Finance in 2019). Fundamental reforms during the 2000s made commercial banks competitive, well capitalised and well regulated. However, one structural flaw was the tendency of commercial banks to engage in pro-cyclical lending as in other OECD countries (Huizinga and Laeven, 2019; Çolak et al., 2019). Whereas Turkey’s public banks are subject to the same legislation as private banks, and are in principle run under the same corporate governance rules, they undertook active countercyclical policies after the 2018 financial turmoil and during the pandemic. This has been visible in the divergence of their lending behaviour from private commercial banks during these downturns (Figure 1.7).

The establishment of a Sovereign Wealth Fund (Türkiye Varlık Fonu - TVF), with the aim of “providing resources for Turkey’s strategic investments” mirrors the same approach in equity financing (Box 1.3). In September 2020, the President also announced an intention to use the retirement savings accumulated in the 2nd pillar pension system (BES, worth approximately 3.5% of GDP as of September 2020 ) “as long-term and low-cost funding sources for the real economy”. No further details were made public. The BES system is currently managed by a competitive pension fund management industry (OECD, 2019c).

Government-owned banks generated 72% of the net credit increase in 2019, and more than 60% in the first half of 2020. Their weight in financial intermediation raises new challenges. While banking regulations are line with international good practices, and Turkey complies with Basel rules, extensive reliance on public banks raises risks. A recent analysis of government-owned banks’ lending found that it is strongly affected by Turkey’s national political cycle as well as local political circumstances (Bircan and Saka, 2019). Once the most acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic is over, a transparent environment should be restored between different types of financial institutions. Public banks’ corporate governance practices, their competiton conditions with private banks, and the financing of their public service obligations should be closely examined in the light of international good practices (OECD, 2015c). Banking regulators should involve the Turkish Competitiion Authority to ensure a level playing field between public and private banks - as well as between public and private borrowers in access to finance. Such efforts would improve the pricing of risks and the efficiency of credit allocation.

Quasi-fiscal channels helped minimise the burden of the pandemic on public finances in the first wave, facilitated the distribution of liquidities, and rendered part of the transfers reimbursable. At the same time, the transparency of the support package, its targeting to businesses and households most in need, and its consolidation in a coherent macroeconomic framework was made more difficult. To support the recovery:

Fiscal policy should replace concessional credits to eligible households and businesses with reduced prospects to reimburse their loans, by direct temporary transfers. Fiscal room is available for such a re-balancing of support channels.

Fiscal tightening should resume only gradually, once the recovery is firmly underway.

The contingent liabilities that public bank loans and government loan guarantees raise for public finances (not only the guarantees underwritten by the Treasury) should be transparently gauged.

As long as the pandemic is not under control, all room available for fiscal support should be preserved for helping the health system and the households and businesses in need. Lesser priority plans should be postponed, to preserve room for rapid fiscal response to changing needs.

Turkey’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (TVF) was created with a special law in 2016. It became part of the Presidency in 2018, the President becoming its Chairman of the Board and the Minister of Treasury and Finance its Deputy Chairman. Its board composition, its special legal status and its strategic mandate make it a unique entity. It aims at “developing and increasing the value of Turkey’s strategic assets, at providing equity for Turkey’s strategic investments, at financing large infrastructural projects, at deepening the local capital markets, at stimulating employment, and at supporting Turkey’s international economic objectives” (TVF, 2020). It is expected to “help reduce Turkey’s chronic current account deficit by investing in petrochemical, mining and energy sectors”.

As of October 2020 the Fund was led by Mr.Z. Sonmez, the former Turkey head of Malaysia’s national wealth fund Khazanah, who described TVF as “an Asian style asset-based development fund inspired by Singapore’s Temasek and Malaysia’s Khazanah”.

A large set of government assets were transferred to TVF. Its portfolio comprises listed and non-listed firms in various sectors, including financial services, energy and mining, transportation and logistics, technology and telecommunications, agriculture and food - including Turkish Airlines, Turkish Petroleum, Ziraat Bank and Turkish Post. According to its consolidated financial statements at the end of 2019 its total assets reached TRY 1.46 trillion (US $ 245 billion at that date) and its net equity TRY 234.54 billion (USD 39 billion).

TVF has access to a variety of funding sources, including cash and assets that may be transferred from other public institutions; dividend, rental and royalty income from the assets it owns; and direct funding from local and international financial markets.

It was granted immunity from a range of laws and regulations including the Law on the Court of Accounts (it is not audited by the Court of Accounts) and the Law on the Protection of Competition. This could reduce competition in the markets and activities where TVF intervenes. It is also exempt from certain taxes and charges including the stamp duty, income and corporate taxes, tax deductions and from the fees of the Borsa Istanbul. Under Turkey’s Banking Law (No. 5411) the loans to be made available to risk groups defined in the Banking Law cannot exceed twenty-five percent of their own equities. However, according to an amendment in this Law in February 2020, TVF is exempted from this limitation as it is not included in the designated risk groups.

TVF’s 2018 and 2019 financial statements were audited according to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). It is a member of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds and has committed to comply with its ‘Santiago Principles’ (SWF, 2008). TVF could also draw on OECD’s “Guidance on Sovereign Wealth Funds” (OECD, 2008). This guidance contains principles and safeguards to help countries with both such funds and those receiving their investments to facilitate their operation in a transparent and open framework.

Once the recovery takes hold, the medium-to-long term sustainability of public finances should be improved. OECD’s public debt projections presented in Figure 1.10, which take into account the costs of the COVID-19 shock, show that the prudent ‘fiscal policy debt limit’ estimated at 35-40% of GDP (see below) is already breached, and will be difficult to restore in the period ahead. Under unchanged policies, the public debt/GDP ratio is projected to increase strongly. Ageing-related spending as a result of the closure of Turkey’s demographic window around 2025-2030 is expected to bear on debt dynamics.

Recent changes in the composition of government debt, including its lower average maturity and the higher share of floating rate and foreign currency borrowings increased vulnerability to adverse developments in exchange and interest rates (Ministry of Treasury and Finance, 2020). In November 2020, the authorities announced an intention to increase again the share of long-term Turkish Lira borrowings. The outlook may turn more straining if the contingent liabilities accumulated during the COVID-19 shock move on balance sheet. This risk is not taken into account in the projections of Figure 1.10. Public debt dynamics could in contrast improve if Turkey’s trend growth rate is lifted-up and if risk premia and real interest rates are reduced thanks to the reforms recommended in this Survey (Figure 1.10).

Turkey’s room for fiscal manoeuvre would increase if its status on financial markets were upgraded. This would create fiscal space in the event of a renewed worsening of the pandemic, and would allow time to strengthen the public finances once the recovery is on track. An estimate based on past responses of Turkey’s risk premia to alternative public debt trajectories suggests that the public debt-to-GDP ratio should stay below the 50-55% band in order to cope with persisting exchange and interest rate risks. Once the public debt ratio reaches the 30-40% band, the countercyclical impact of fiscal stimuli starts to weaken, due to adverse impacts on risk premia and market interest rates (fiscal policy debt limit as discussed in Özatay, 2019). Such thresholds will vary in the post-pandemic world as a result of changes in global public finance benchmarks, but these considerations should be taken into account in the long-term planning of fiscal policy.

The reduction of general government debt from around 76% of GDP in 2001 to around 38% in 2008 – which positively decoupled Turkey from several other OECD countries – was a major achievement of Turkish macroeconomic policy (OECD, 2010). It triggered a massive fall in Turkey’s risk premia and created much welcome room for countercyclical fiscal policy. This room was effectively utilised following the global financial crisis, and more aggressively in the recent period, both after the 2018 and COVID-19 shocks.

Strengthening fiscal institutions would help improve the management of public finances and market credibility in the current circumstances (Box 1.4). Four goals matter most:

General government accounts should be reported according to international national accounting standards. These should be used as the central planning and communication instrument of fiscal policy. Government accounts are currently published by different agencies (including the Ministry of Treasury and Finance, the Strategy and Budget Unit of the Presidency, and Turkstat) using the same basic data (from the General Directorate of Accounting of the Ministry of Finance) but along their specific methodologies. There are only slight differences between these methodologies and each one has its respective utility, but the planning and communication of fiscal policy should be unified around a common set of international national accounting standards. This would facilitate the timely generation of general government accounts, their international comparability and their monitoring and analysis on a cyclically-adjusted basis. Central budget outcomes (significantly narrower than general government outcomes) should be focused at principally for high frequency indicators.

A Fiscal Policy Report, on the model of the Central Bank’s Inflation and Financial Stability reports, based on quarterly general government accounts, should review the totality of the above-the-line and below-the-line public revenues and expenditures, and below-the-line contingent liabilities.

Once the exceptional public finance conditions of the COVID-19 shock are behind, a fiscal rule should be re-introduced under the surveillance of an independent Fiscal Council, as in many other OECD countries. The rule developed in 2010 (but then not implemented) remains well adapted to Turkey’s circumstances (see Box 1.4).

A tax reform is compelling on both economic and social grounds. A key priority should be reducing labour taxes as discussed later in this chapter. Social protection should be financed from more employment-friendly sources. The recurrent tax amnesties should be discontinued. The recent digital taxes should be re-examined in the light of ongoing international co-operation (OECD, 2019h).

Building confidence in the long-term sustainability of public finances is essential. This should implicate both general government finances and quasi-fiscal and contingent liabilities. The 2005 Law on Public Financial Management and Control (Law 5018) should be fully enforced to this effect. This legislation defined a comprehensive fiscal policy framework (Yilmaz and Tosun, 2010). It prescribed a programme-based spending framework, area specific funding ceilings, performance benchmarks, and a good financial control and audit system. It vested the Court of Accounts and the Parliamentary Budget and Planning Commission with the task of monitoring the actual fiscal position, including off-budget liabilities.

Three streams of off-budget liabilities deserve special attention in Turkey:

The contingent liabilities of public financial institutions, including government-owned banks (Ziraat, Halkbank and Vakifbank), the Eximbank, the Development and Investment Bank, the Sovereign Wealth Fund and the Credit Guarantee Fund. The liabilities of these institutions expanded strongly following the August 2018 financial turmoil and the COVID-19 crisis.

The contingent liabilities of public-private partnerships (PPPs). Turkish PPPs reached the highest average investment size per project among all emerging countries – they are estimated at almost USD 600 million per project by the World Bank. On the other hand, according to the Turkish Presidency Strategy and Budget Unit database, the average investment size of PPPs is slightly above USD 300 million. More than 250 PPP projects in a wide range of activities were operational in 2020 (Table 1.3). Yearly disbursements for realised liabilities are published, but a prospective analysis of the obligations that may arise in the future is not available. These obligations will depend on commercial and financial contingencies – such as those currently experienced in airports. They may reach very high levels.

Public pensions. Pensions are not included in public debt in a conventional sense. They represent nonetheless a substantial liability for public finances and should be properly assessed in efforts to secure their sustainability. The closure of Turkey’s demographic window around 2025-2030 is an important challenge (OECD, 2018a). Low average retirement ages, low contributor/beneficiary ratios, and the uncertainties concerning the indexation of future pension benefits create financial risks. Scenarios for long-term financial balances of public pensions should be regularly published in the recommended Fiscal Policy Report.

A formal fiscal rule adapted to Turkey’s circumstances, as was designed in 2010, should also be put on the agenda. This design was backed by the OECD at its inception (OECD, 2010). It was a “growth-based balance rule”, setting a ceiling for the annual general government deficit, which would be a function of: i) the general government deficit in the previous year; ii) the deviation of the previous year’s deficit from the long-term deficit target; and iii) the deviation of the GDP growth of the current year from the trend growth rate.

The objective of the 2010 fiscal rule was to maintain the public debt/GDP ratio at around 30% in the long-term. Policymakers were given three “windows” in the course of each year to adapt fiscal policies to the requirements of the rule: i) in the spring of the year t – 1, when preparing the medium-term economic framework of the year t; ii) in the fall of the year t – 1 when finalising the budget for the Parliament; and iii) in the spring of the year t, when the growth and fiscal outlook become more precise.

If a fiscal rule of this type, which is well-adapted to Turkey’s circumstances is implemented, an independent Fiscal Council can be vested with its monitoring and implementation as in other OECD countries.

Stabilising inflation and increasing monetary policy credibility

The COVID-19 shock amplified the longstanding challenges of Turkey’s monetary policy (OECD, 2018a). Inflation is high, stuck at a level well above the official target of 5% and its responsiveness to the cyclical position of the economy is low (Figure 1.11). In the face of the high output and employment cost of disinflation, and under the appeals of the executive authority, the central bank has long been perceived by international investors as prioritising growth and employment over price stability (Goldman Sachs, 2020; Citibank, 2020). Furthermore, during periods of decline in risk appetite in international markets, capital outflows tend to lead Turkish authorities to try to contain exchange rate depreciation through direct and indirect interventions. This tends to generate tensions with Turkey’s officialy open capital account, currency convertibility and floating exchange-rate regimes – compounding investor uncertainties. The COVID-19 shock has amplified this policy conundrum:

Increases in inflation. Inflation and inflation expectations augmented after the COVID-19 shock from an already high level (Figure 1.11). Additional price pressures resulted from exchange rate depreciation, cost increases in value chains, changes in work organisations, and, in certain markets such as housing and motor vehicles, from credit-fuelled demand. Inflation expectations picked up and remained significantly above the official inflation target as well as the official inflation projection (that the central bank asserts as “an interim target when inflation deviates significantly from target”- CBRT, 2019a). The central bank lifted its end-year inflation projection from 7.4% in April 2020 to 8.9% in July and 12.1% in October. Market expectations reached 12.5% in November, whereas actual inflation reached 14% in November and 14.6% in December, heralding a further worsening in expectations.

Monetary stimulus through new channels. In response to the COVID-19 shock, the Central Bank announced various “Measures Against the Economic and Financial Impacts of the Coronavirus” (Box 1.1). It slashed its policy rate to 8.25% in May and pulled down the real policy rate to negative territory (both on an ex-post and ex-ante basis). It launched quantitative supports as in other emerging countries (Benigno et al., 2020), offering additional liquidity windows for banks, larger rediscount facilities for businesses, and higher ceilings for government securities in its portfolio. As a result, the monetary base, the size of the central bank’s balance sheet and total money supply have all expanded (Figure 1.11, Panels E and F). By August, the expansion of money supply (M1) was the fastest among emerging countries and reached an annual increase of 70% -- against an emerging countries median of 11%. These developments increased uncertainties about the viability of the official inflation target.

Faced with an acceleration of capital outflows and exchange rate depreciation through Summer, the Central Bank took tightening steps. It started to tighten liquidity in August, raised the policy interest rate by 200 basis points to 10.25% at the end of September, and a further 475 basis points to 15% in mid-November. Between these two increases, it refrained from lifting up the policy rate directly, and tightened liquidity indirectly by offering funding through higher cost channels. This increased its effective funding rate to 13.40% by the end of October, but, despite this significant tightening, the divergence between official and effective monetary stances was interpreted by markets as a sign of political constraints to the independence of the Central Bank. These constraints had increased after legislative changes in 2019 which shortened the tenure of the top management of the Bank and facilitated conditions for its removal (actually permitting the removal of one governor in mid-2019). All in all, developments during the COVID-19 crisis increased market uncertainties over the future course of monetary policy, fuelled risk premia and accelerated exchange rate depreciation until November 2020. Against this backdrop, the appointment of a new governor in November 2020, with the Bank re-iterating price stability as its fundamental objective, associated with a consequential increase in the policy interest rate and its re-confirmation as the main channel of liquidity provision improved investor expectations. Risk premia and exchange rates eased.

Both policy and effective funding rates had stayed in negative territory in real terms (on an ex post as well as ex ante basis, as discounted by current and expected inflation) during most of 2020. They turned positive only in November. If expectations do not converge with the Bank’s inflation target and projections in the period ahead, and if risk premia and exchange rates are not durably appeased, the real rate would need to be lifted up further. It would need to be kept firmly and consistently in positive territory to regain credibility for monetary policy.