13. India

Support to agriculture

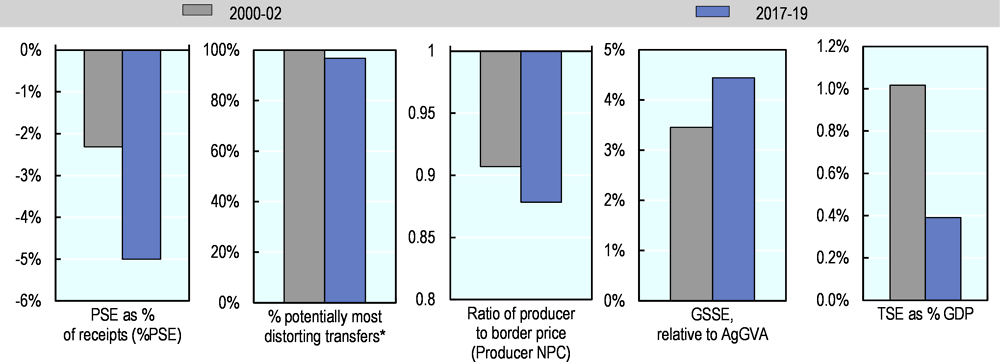

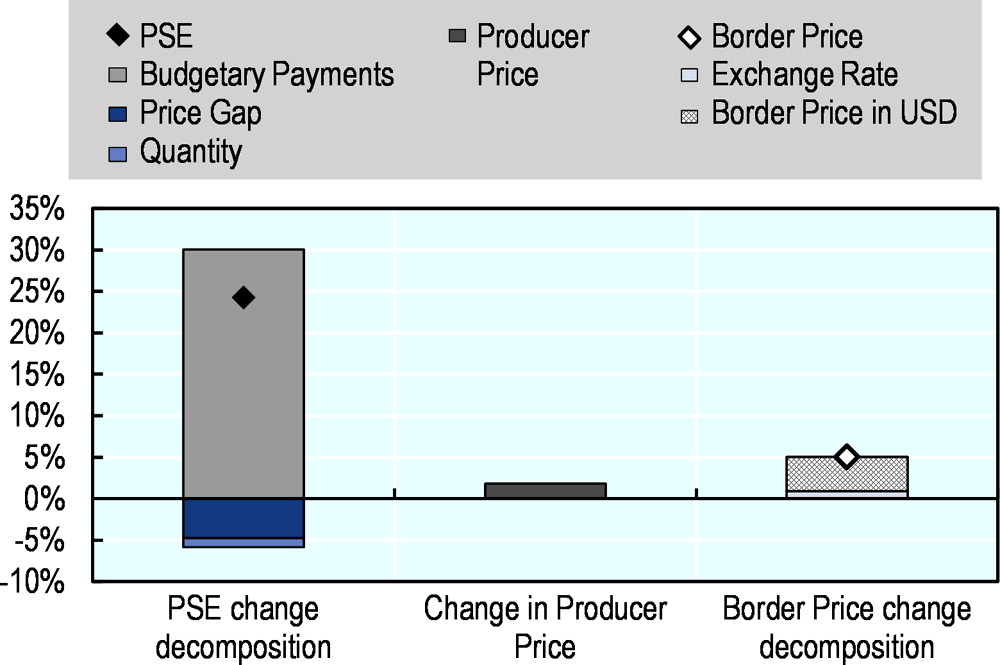

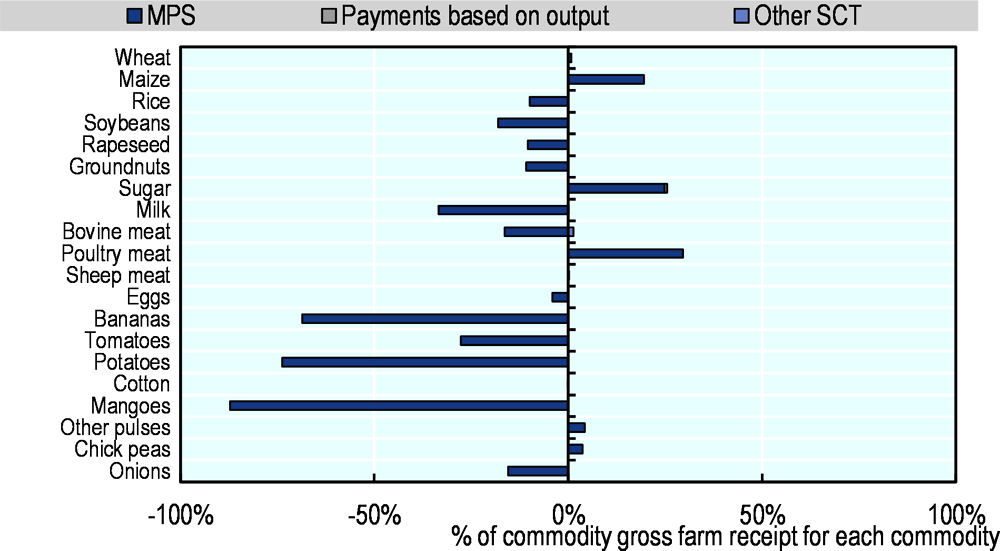

Support to producers in India is composed of budgetary spending corresponding to 7.8% of gross farm receipts, positive market price support (MPS) of +2.0% of gross farm receipts among those commodities which are supported, and negative MPS of -14.8% among those which are implicitly taxed. Overall, this leads to negative net support of -5.0% of gross farm receipts (%PSE) in 2017-19. The negative value of the PSE reflects that domestic producers, overall, continue to be implicitly taxed, as budgetary payments to farmers do not offset the price-depressing effect of complex domestic regulations and trade policy measures. Budgetary transfers to agricultural producers are dominated by subsidies for variable input use, such as fertilisers, electricity, and irrigation water. In turn, public expenditures financing general services to the sector (GSSE), principally for infrastructure-related investments, correspond to just half of the subsidies for variable input use. Total budgetary support (TBSE) is estimated at 2.5% of GDP in 2017-19.

Mirroring the farm price-depressing effect on producers, the policies provide implicit support to consumers. Policies that affect farm prices, along with food subsidies under the Targeted Public Distribution System, reduced consumption expenditure by 21.4% (%CSE) on average across all commodities in 2017-19.

Main policy changes

Minimum support prices (MSPs) were increased in July 2019 for all kharif crops (summer planted) and in October 2019 for all rabi crops (winter planted).

The application of the direct income transfer scheme Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) – providing an annual payment of INR 6 000 (USD 84) per farm household – was extended from small-scale farmers (with landholdings up to 2 hectares) to all farmers with land titles. Investments in Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) were also stepped up in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 Union Budgets, including through new schemes in specific sectors such as vegetables (tomatoes, onions, potatoes) and dairy.

After an increase in both fertiliser and food subsidies in the 2019-20 Union Budget, the budgetary allocations for these were lowered in the 2020-21 Union Budget by 10.8% and 37%, respectively.

In September 2019, export restrictions – including minimum export prices followed by an export ban – were introduced on onions. In addition, the central government introduced limits on stocks held by private traders.

Assessment and recommendations

The measurement of support related to agricultural policies (PSE) highlights one of the fundamental issues in Indian agriculture: that for many products and over most of the period reviewed Indian farmers have been receiving prices that are lower than the prices prevailing on international markets. The central government should continue the initiatives to reduce domestic marketing inefficiencies and work closer with states and Union Territories (UTs) to thoroughly reform regulations and to foster more efficient and competitive markets, including through initiatives such as the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM). Marketing provisions should be adopted in a harmonised and consistent way across states and should be synchronised with any Minimum Support Price (MSP) system reforms through coherent plans.

India is an important agro-food exporter in a number of commodities. The Agricultural Export Policy (AEP) framework adopted in 2018 has set an important step towards reducing uncertainty and transaction costs throughout supply chains by engaging to avoid the application of export restrictions for organic and processed agricultural products. However, the recent application of export restrictions on onions directly affected India’s reliability as a supplier and exacerbated farm revenue losses – an extension of the AEP to avoid applying export restrictions on any agro-food products should therefore be considered to create a stable and predictable market environment.

Reducing tariffs and relaxing other import restrictions is also key for a predictable market environment and for exploiting into the potential of imports to contribute to diversification of diets and improve food security across all its dimensions. Together with domestic marketing reforms, moving away from export and import restrictions has the potential to provide farmers and private traders with improved incentives to invest in supply chains.

The large share of employment in agriculture compared to its GDP contribution reflects the persistent productivity gap with other sectors, which translates into low farm incomes. In the short to medium-term, direct cash transfers targeting the incomes of poorest farmers can support their livelihoods in current market conditions. In the long-term, significant structural adjustments need to occur in India involving the transition of farm labour to other activities and a process of consolidation towards farm operations sufficiently large to benefit from economies of scale. In this sense, continued reforms in land regulations need to be complemented by investments in key public services to the sector (such as education, training, infrastructure) and the broader enabling environment (including financial services).

India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) include an economy-wide emission intensity reduction target, but no sector-specific targets have been set. Policy efforts for mitigating GHG emissions have concentrated around pilot projects for lower methane emission rice production, increased fertiliser efficiency, and soil health improvement. Generating savings by continuing to scale back variable input subsidies can be used to train farmers in an efficient and sustainable use of such inputs, by ensuring extension systems focus more on climate change, sustainability, and digital skills. Continued investments in the agricultural knowledge system and knowledge transfer through FPOs are important to ensure sustained and sustainable productivity growth.

India has made significant progress in recent years in eliminating waste and inefficiencies in the food distribution system and these efforts should continue. The Government of India should continue the experimental replacement of physical grain distributions by direct cash transfers, and expand and adjust in light of experiences gained.

Policy responses in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak

Agricultural policies

In order to limit disruptions in farm operations, the government relaxed lockdown norms for agriculture-related activities under the nation-wide lockdown in the context of COVID-19. This concerns farm work in the field, agencies engaged in the procurement of agriculture products, mandis markets operating under the Agricultural Product Marketing Committee (APMC) or notified by state and Union Territories (UTs) governments, Custom Hiring Centres (CHCs) for farm machinery, as well as packaging facilities for fertilisers, pesticides, or seeds (Times of India, 2020[1]).

The government decided in March 2020 to frontload to the first week of April the first instalment of INR 2 000 (USD 26) within the direct income transfer scheme Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) covering all farmers with land titles (Outlook India, 2020[2]).

The central government will grant the 3% prompt repayment incentive (PRI) to all farmers for all short-term crop loans of maximum INR 300 000 (USD 3 938) which are due up to 31 May 2020, even if farmers fail to repay loans until this date (Government of India, 2020[3]).

On 11 April 2020, the government announced that the procurement of wheat will be carried out in three stages from mid-April to the end of June 2020 in order to reduce congestion in markets. The central government has advised state governments to increase the number of procurement centres and find additional platforms for procurement in addition to APMC mandis markets, as well as to issue tokens to farmers that can ensure an orderly activity in markets (Times of India, 2020[4]).

In April 2020, the government encouraged farmers to use the federally-developed application Kisan Suvidha in order to obtain information on weather or market prices during lockdown (Hindustan Times, 2020[5]).

Agro-food supply chain policies

On 24 March 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare (MAFW) launched new features of the electronic National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) platform in order to reduce the need to physically travel to APMC mandis markets for selling crops. The new features include: (i) a warehouse-based trading module to facilitate trade directly from warehouses based on e-Negotiable Warehouse Receipts (e-NWR); and (ii) a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) trading module whereby FPOs can trade their produce from their respective collection centre without bringing the produce to APMC markets (Government of India, 2020[6]).

Several measures were aimed at limiting transportation disruptions and delays in supply chains. On 25 March 2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a notice information to states and UTs that transportation of animal feed and fodder was considered an essential service and would thus be exempted from any inter-state restriction under the 2005 Disaster Management Act (Government of India, 2020[7]). The relaxed norms for agriculture-related activities under the lockdown also allow for the inter-state movement of harvesting and sowing machinery (Times of India, 2020[1]). In addition, Indian Railways set up special railway parcel trains for the transportation of essential items, including food products, in small parcel sizes (Government of India, 2020[8]).

Several states – such as Delhi, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Telangana, and West Bengal – issued curfew passes and created task forces headed by senior policemen to ensure smooth inter-state movement of goods (The Straits Times, 2020[9]).

The Ministry of Shipping issued specific guidelines to main ports applying from 22 March to 14 April 2020 on exemptions and reductions of penalties, demurrages charges, and other port fees for traders in relation to any potential delay in cargo port operations (Government of India, 2020[10]). At the same time, port protocols have been adjusted, ranging from quarantine measures to additional documentation requirements and examinations, while at the end of March 2020 ports were advised by the Ministry of Shipping that they may consider the COVID-19 pandemic as grounds for invoking ‘force majeure’, a clause absolving companies from meeting their contractual commitments for reasons beyond their control (Bloomberg, 2020[11]).

Central and state level governments have been making efforts to maintain the operation of distribution channels for fruit and vegetables. During the last week of March 2020, almost 1 900 vegetable mandis markets retook their operations in order to ensure a smooth supply of fruit and vegetables (Economic Times, 2020[12]). States such as Odisha have set up “vegetable counters” as an alternative channel of distribution in addition to providing support to small farmers for selling their produce in district and urban centres (Deccan Herald, 2020[13]).

India’s National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) urged all milk co-operatives to ensure supply of milk and milk products, against the background of co-operatives such as the Karnataka Cooperative Milk Federation stopping sales of milk to neighbouring states (Dairy Global, 2020[14]).

Consumer policies

On 18 March 2020, the government of India decided to distribute a six-month quota of subsidised food grains in one-go to beneficiaries under the PDS, with the objective to prevent eventual panic buying under the COVID-19 lockdown and potential price increases (Economic Times, 2020[15]). In addition, on 25 March 2020, the central government increased the monthly allocation of subsidised food grains by 2 kg to 7 kg per person, aiming to ensure a sufficient supply of food grains during the COVID-19 lockdown (Economic Times, 2020[16]). Then, on 26 March 2020, the government approved the free distribution of an additional 5 kg of food grains per person and 1 kg of pulses per household (according to regional preferences) for three months under the COVID-19 economic package PM Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana targeting urban and rural poor, including migrant workers (Government of India, 2020[17]) (Economic Times, 2020[18]).

In addition, specific state- or UT-level initiatives also target distribution of grains and other food products. Some of these include the following (IFPRI, 2020[19]):

States including Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Manipur, Odisha, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal are providing additional quantities of wheat and rice (between 1 kg and 10 kg per month for varying periods and for different categories of households).

States including Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Odisha, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu are also providing other agro-food products like pulses, oil, salt, or sugar.

Other

Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent national lockdown, the central government decided on 27 March 2020 to extend the current Foreign Trade Policy 2015-20 for six more months until 30 September 2020, as it was due to expire at the end of March and be replaced by the Foreign Trade Policy 2020-25. Consequently, all the existing schemes under the current policy will be extended over this period (Business Standard, 2020[20]).

Support to producers (%PSE) remained negative throughout the last two decades, but fluctuated markedly over this period. It averaged -5% in 2017-19. A positive MPS for wheat, maize, sugar, chick peas, other pulses and poultry meat, together with large input subsidies, only partly compensate the large negative MPS for the majority of exported products in 2017-19, worth 14.8% of gross farm receipts. Policies for these commodities over the period covered – whether impeding exports or depressing producer prices through domestic marketing regulations – led to prices received on average by farmers 12% lower than reference prices in 2017-19 (Figure 13.1). Virtually all gross producer transfers (whether positive or negative, i.e. expressed in absolute terms) are implemented in forms that are potentially most production and trade distorting, a consistent pattern since 2000-02. Absolute levels of producer support increased year-on-year (i.e. became less negative), driven by higher budgetary allocations to the direct income transfer programme PM-KISAN (Figure 13.2). Single commodity transfers (SCTs) mirror the MPS pattern, with most commodities being implicitly taxed in the range between 0.2% and 87% of commodity receipts (Figure 13.3). At 4.4% in 2017-19, expenditure for general services (GSSE) relative to agriculture value added increased compared to 2000-02, contributing to an overall positive total support estimate (TSE) of 0.4% of GDP.

Contextual information

India is the seventh largest country by land area and the second most populous after the People’s Republic of China with over 1.3 billion people (Table 13.2). While the share of urban population continued to increase over the past decade, about two-thirds of the population still live in rural areas. At just 0.15 ha per capita, agricultural land is very scarce.

Agriculture accounts for an estimated 43.9% of employment, but its 14.6% share in GDP indicates that labour productivity remains significantly lower than in the rest of the economy. The productivity gap is also reflected in the evolution of farm incomes, which correspond to less than one-third of non-agricultural income. The share of value added from agriculture has been gradually reduced, but mostly in favour of services rather than manufacturing. Services led economic growth over the last 15 years, playing a more important role in India’s economic development than in most other major emerging economies.

Indian agriculture is continuing to diversify towards livestock and away from grain crops. While grains and milk remain dominant, there has been a gradual change in the composition of production to other crops – such as sugar cane, cotton, fruit and vegetables – as well as certain meat sub-sectors. Livestock output growth has been faster and less volatile than crop production. The sector continues to be dominated by a large number of small-scale farmers, as the national average operational holding size has been in steady decline.

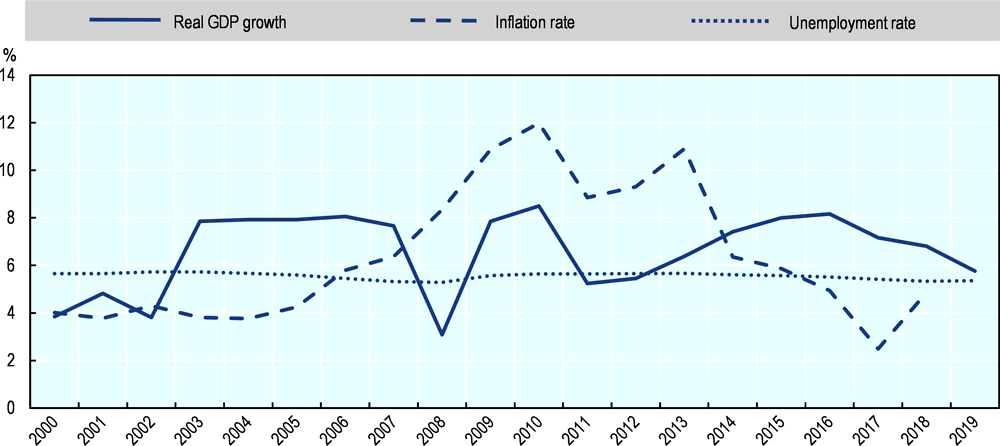

Real GDP growth has been decelerating since 2016 and reached 5.8% in 2019, highlighting remaining structural bottlenecks in areas such as labour markets or the business environment. In this sense, the low unemployment figures (average of 5.4% in 2017-19) hide significant degrees of informal employment. Against the background of higher prices for selected food items, inflation increased to 4.9% in 2018-19 (Figure 13.4).

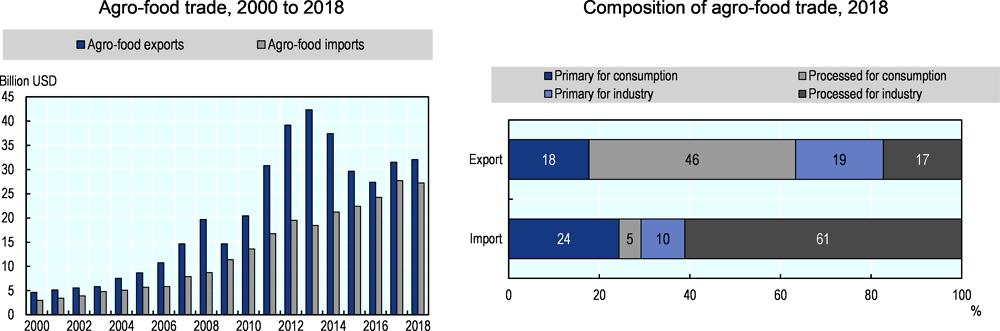

India has consistently been a net agro-food exporter over the last two decades, but agro-food imports have been increasing since 2007, while exports trends have declined from the peak of 2013. Products for direct consumption – of low value, raw or semi-processed, and marketed in bulk – dominate agro-food exports, representing 64% of the total in 2018. Processed products for further processing by domestic industry are the main import category, accounting for 61% of total agro-food imports (Figure 13.5).

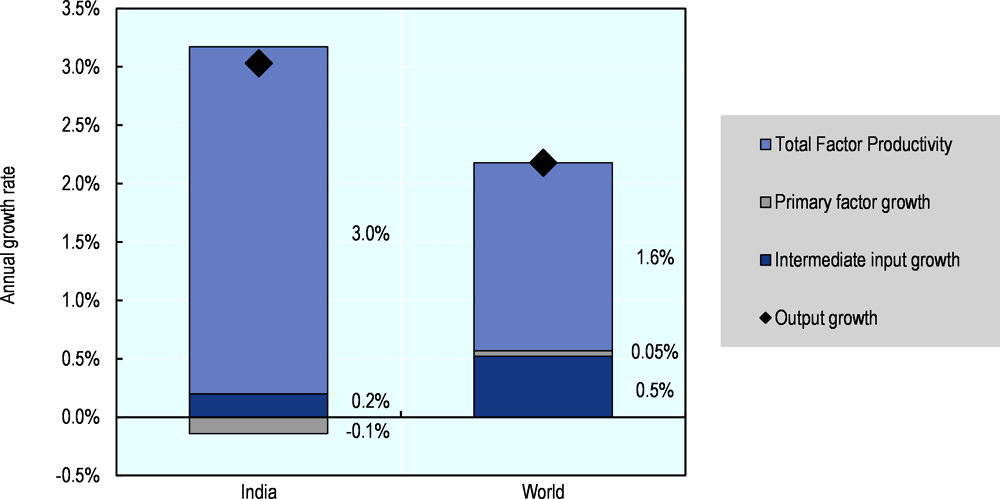

Agricultural output growth in India averaged 3% in 2006-15, more than one-third above the world average (Figure 13.6). This has been driven mainly by an important increase in total factor productivity (TFP) at 3% per year, backed by technological progress in the form of improved seeds and better infrastructure (including irrigation coverage, road density, and electricity supply).

However, the sustained growth in agricultural output has been exerting mounting pressures on natural resources, particularly land and water. This is reflected in the nutrient surplus intensities at the national level, which are much higher than the average for OECD countries. The share of agriculture in total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is also higher than the OECD average, but is in direct link as well to the size of the agricultural sector in the Indian economy. Livestock rearing is the main source of GHGs (Table 13.3).

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Over the past several decades, agricultural policies have sought to achieve food security, often interpreted in India as self-sufficiency: seeking to ensure that farmers receive “remunerative” prices, while at the same time safeguarding the interest of consumers by making food available at affordable prices. The set of policies directly relating to agriculture and food in India consist of six major categories: i) managing the prices and marketing channels for many farm products; ii) making variable farm inputs available at government-subsidised prices; iii) providing general services for the agriculture sector as a whole; iv) making certain food staples available to selected groups of the population at government-subsidised prices; v) regulating border transactions through trade policy; and vi) more recently, a farmer welfare focus through the income support scheme PM-KISAN. In addition, environmental measures concerning agriculture have been gaining prominence (OECD/ICRIER, 2018[21]; ICRIER, 2020[22]; Gulati, Kapur and Bouton, 2020[23]).

In India, states have constitutional responsibility for many aspects of agriculture, but the central government plays an important role by developing national approaches to policy and providing the necessary funds for implementation at the state level. The broad policy guidelines are currently set within a framework of three-year action agendas, prepared by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog, a policy think tank of the government of India).1 The central government (Union Cabinet) is responsible for some key policy areas, notably for international trade policies and for overseeing the implementation of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) of 2013. In 2016, the central government set the target of doubling farmers’ income by 2022-23, identifying seven sources of income growth key to driving the design and implementation of agricultural policies: improvement in crop and livestock productivity; resource use efficiency; increase in the cropping intensity; diversification towards high-value crops; improvement in real prices received by farmers; and shift from farm to non-farm occupations.

Policies that govern the marketing of agricultural commodities in India – from the producer level to downstream levels in the food chain – include the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) and the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts. Through these acts, producer prices are affected by regulations influencing pricing, procuring, stocking, and trading of commodities. Differences exist among states in the status of their respective APMC Acts and in how these acts are implemented. The electronic portal (electronic National Agricultural Market, e-NAM) initiated in 2016, and the 2017 model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act – shared with state governments as a recommendation for adoption – aim to gradually encourage a single national agricultural market. Agriculture marketing also covers the futures market governed by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), with the largest value of agricultural commodity trade taking place through the National Commodity Derivative Exchange (NCDEX). In addition, the Negotiable Warehouse Receipt System (NWRS) – established under the Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA) – aims to support farmers with storing produce in warehouses.

Based on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the central government establishes a set of minimum support prices (MSPs) for 24 crops each year. The CACP recommends the MSPs based on the costs of production at two levels: the costs of variable inputs such as seeds, manure, chemicals, fuel, irrigation, rent paid for leased land as well as interest on working capital (A2) and the estimated value of family labour (FL). The CACP does not include in its recommendation the imputed rent of owned land and the imputed interest on owned capital (C2). State governments can also provide a bonus payable above and over the MSP for some crops. The national and state-level agencies operating on behalf of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) buy wheat, rice and coarse grains through open-ended procurement at MSP. A number of other agencies can buy pulses, oilseeds and cotton at MSP - including through the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Yojna (PM-AASHA) programme introduced in 2018 – and some perishable agricultural and horticultural commodities without MSP are also procured. However, procurement under the price support scheme has been effectively operating mainly for wheat, rice and cotton and only in a few states.

The only payments based on output concern the sugar sector and were introduced in 2018. The payments support sugar mills to clear sugar cane arrears and are directly paid to sugar cane farmers.

On the input side, major policies enable agricultural producers to obtain farm inputs at low prices. The largest input subsidies are provided through policies governing the supply of fertilisers, electricity, and water. Other inputs are also supplied at subsidised prices, including seeds, machinery, credit, and crop insurance. In recent years, state-level loan debt waivers increased significantly, with local governments compensating lending institutions for forgiving debt to farmers. About two-thirds of agricultural loans are from financial institutions such as commercial banks, with the rest stemming from non-institutional sources (e.g. moneylenders) (Reserve Bank of India, 2019[24]).

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme provides an annual direct income transfer of INR 6 000 (USD 84) to all farmers with land titles. The unconditional payment does not require farmers to produce and targets farmers’ broad needs, which can include everything from the purchase of inputs to any other non-farming related needs.

In the area of general services, expenditures are dominated by the development and maintenance of infrastructure, particularly related to irrigation. Public expenditures for public stockholding and related to the agricultural knowledge and innovation system are also significant.

Public distribution of food grains operates under the joint responsibility of the central and state governments. The Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) operates under the NFSA in all states and Union Territories (UTs). A set of Other Welfare Schemes (OWS) also operate under the NFSA. The central government allocates food grains to the state governments and the FCI transports food grains from surplus states to deficit states. The state governments are then responsible for distributing the food grain entitlements, i.e. allocating supplies within the state, identifying eligible families, issuing ration cards, and distributing food grains mainly through Fair Price Shops.

India’s Foreign Trade Policy – formulated and implemented by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) – is announced every five years, but it is reviewed and adjusted annually in consultation with relevant agencies. The current policy applies until 2020. India’s Basic Customs Duty (BCD) (also known as the “statutory rate”) is agreed at the time of approving the annual budget.

India has managed for several decades its agricultural exports through a combination of export restrictions, including export prohibitions, export licensing requirements, export quotas, export duties, minimum export prices, and state trading requirements. The application or elimination of such restrictions could be changed several times per year, taking into account concerns about domestic supplies and prices.

Regarding export subsidisation in agriculture, the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) – under the responsibility of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) – has in recent years provided financial assistance to exporters in the form of transport support.2

The Agriculture Export Policy framework – approved in December 2018 – has as main objectives doubling agricultural exports by 2022-23 and boosting the value added of agricultural exports. The policy document also includes three main areas for action that could support the above objectives under “a stable trade policy regime”. First, ensuring that processed agricultural products and organic products would not be subject to export restrictions. Second, initiating consultations among stakeholders and Ministries in order to identify the “essential” food security commodities on which export restrictions could still be applied under specific market conditions. Third, reducing import barriers applied to agricultural products for processing and re-exporting.

India ratified the Paris Agreement on Climate Change on 2 October 2016, with its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) submitted a year earlier becoming its NDC. The NDC includes a commitment to reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 33-35% by 2030 below 2005 levels, but specifies that this commitment does not bind India to any sector specific mitigation obligation or action (Climate Action Tracker, 2018[25]).

With regard to agriculture, India’s NDC has a strong focus on climate change adaptation, as addressed in several of the central government’s main programmes for agriculture (entitled “missions”). These include, among others, the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture; the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana mission promoting organic farming practices; the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana mission promoting efficient irrigation practices; or the National Mission on Agricultural Extension & Technology.

Domestic policy developments in 2019-20

Developments in the policy and legal frameworks

The 2019-20 Union Budget (of July 2019) and the 2020-21 Union Budget (of February 2020) both aimed paving the way towards achieving the central government’s objective of doubling farmers’ income by 2022-23 particularly through the increased allocations to the direct income transfer scheme PM-KISAN (see also section on payments to producers) (Gulati, 2019[26]; PRS India, 2019[27]). The trends in budgetary allocations for fertiliser and food subsidies are at opposite ends under the two budgets. While allocations for fertiliser and food subsidies increased between 2018 and 2019, both fertiliser and food subsidies were lowered for financial year (FY) 2020-21 (by 10.8% and 37%, respectively) (Economic Times, 2020[28]; The Print, 2020[29]). In the 2020-21 budget the central government has nevertheless been deferring important amounts of both fertiliser and food subsidies. First, a significant part of the allocation due to the fertiliser industry as per the provisions of the fertiliser subsidy scheme was not committed. Second, the central government has also not allocated for the entire food subsidy expense incurred by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) in a year for procurement, storage, transportation and distribution of wheat and rice to states. The FCI has thus been covering the gap through various types of loans from sources such as the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) or shorts term loans, bonds, and cash credit limits from banks3 (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

In July 2019, the Prime Minister set up a High Powered Committee of Chief Ministers for the “Transformation of Indian Agriculture”. The current tasks of the Committee include identifying: i) approaches to reforming agricultural marketing regulations at the level of each state; ii) adjustments to the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) to attract private investments in agricultural marketing and infrastructure; and iii) mechanisms for linking marketing reforms with the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM) (Government of India, 2019[30]). Through the 2020-21 Union Budget, the Ministry of Finance outlined a new 16-point agenda for Indian agriculture, primarily focused on improving the cold storage chain and agri-warehousing as well as encouraging states to adopt the agri-marketing model act (LiveMint, 2020[31]).

A group of seven ministers was set up in December 2019 to review the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) crop insurance scheme introduced by the central government in 2016 (Economic Times, 2019[32]). The states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal exited from the central scheme due to low claim ratios (i.e. claims paid against the premiums) and launched their own crop insurance scheme in 2019. Several insurance companies also left the scheme claiming very high costs of reinsurance and a sharp increase in claims caused by recent weather events (Economic Times, 2019[33]; LiveMint, 2019[34]).

Institutional rearrangements

A new Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying was created in May 2019 from the department with the same name under the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (MAFW). The separate ministry was set up with the objective to reflect the increasing importance of the livestock and fisheries sub-sectors in the value of agricultural production, but also to better address issues such as low productivity or animal health (The Indian Express, 2019[35]).

Domestic price support policies

On 3 July 2019, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) approved increases in minimum support prices (MSPs) for all kharif crops (summer planted). This included a raise by 3.5% (INR 60) to INR 1 760 per quintal (USD 248 per tonne) for maize; by 3.6% (INR 65) to INR 1 815 per quintal (USD 256 per tonne) for non-basmati rice; by 2% (INR 105) to INR 5 255 per quintal (USD 741 per tonne) for cotton; and by 2.2% (INR 125) to INR 5 800 per quintal (USD 819 per tonne) for pulses such as pigeon pea (tur). According to the CCEA’s estimates, the MSPs introduced for kharif crops provide a return that is at least 50% above the all-India weighted average cost of production for the respective crops (CACP, 2020[36]).

The increase in kharif crops MSPs was followed by an increase in the MSPs for rabi crops (winter planted) that is to be harvested and marketed during the 2020-21 marketing year, announced by the CCEA on 23 October 2019. With the exception of safflower, the CCEA estimates that the proposed 2019 MSPs increases for rabi crops provide returns more than 50% higher of the all-India weighted average cost of production for the respective crops. For example, the CCEA announcement introduced an increase by 4.4% (INR 85) to INR 1 925 per quintal (USD 272 per tonne) for wheat (return over weighted average cost of 109%); by 5.2% (INR 255) to INR 4 875 per quintal (USD 647 per tonne) for chick peas (gram) (74%); by 6.8% (INR 325) to INR 4 800 (USD 637 per tonne) for lentils (76%); and by 5.3% (INR 225) to INR 4 425 per quintal (USD 588 per tonne) for rapeseed and mustard (90%) (CACP, 2020[36]).

In July 2019, the CCEA decided to maintain the Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for sugar cane unchanged at INR 275 per quintal (USD 39 per tonne) for the marketing year 2019-20. The CCEA also approved a premium of INR 2.75 per quintal (USD 0.4 per tonne) for higher productivity4 (The Hindu Business Line, 2019[37]; GAIN-IN0091, 2019[38]). In parallel, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution increased in February 2019 the minimum selling price for sugar from INR 29 (USD 0.41) per kg to INR 31 (USD 0.44) per kg (MCAFPD, 2019[39]).

Stockholding policies

On 31 July 2019, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution announced that the annual sugar buffer stock would be 4 million tonnes for the period August 2019 to July 2020, 1 million tonnes higher than in 2018-19. As in 2018, instead of buying sugar from mills, the government would finance the cost of storage at mill-owned warehouses (The Hindu Business Line, 2019[37]; GAIN-IN0091, 2019[38]).

Due to the increase in the MSPs, the FCI announced an increase in the reserve price for wheat from government stocks auctioned to private traders under the open market sale scheme (OMSS). On 30 April 2019, the FCI announced the reserve price for wheat for sale under OMSS for the first quarter of the 2019-20 marketing year at INR 20 800 (USD 301) per tonne, with an increment of INR 550 (USD 8) per tonne in the subsequent three quarters (GAIN-IN0095, 2019[40]).

Input subsidies

The only state announcing an additional farm loan waiver scheme in 2019 was Maharashtra (Mahatma Jyotirao Phule loan waiver), waiving up to INR 0.2 million (USD 2 700) for about 8.9 million farmers holding non-defaulting loans, in addition to the INR 254.8 billion (USD 3.4 billion) programme already introduced in 2017. According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), several other states disbursed outstanding payments in 2019 under the programmes initiated since 2014: Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, with an estimated total of INR 369 billion (USD 5.2 billion) allocated for loan waivers in 2019-20. However, available estimates indicate that by March 2020 the selected states only allotted two-thirds of the overall amounts announced at the outset of the programmes (Reserve Bank of India, 2019[24]).

Payments to producers

The 2020-21 Union Budget allocated INR 750 billion (USD 10.6 billion) for the direct income transfer scheme Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) in FY 2020-21. The scheme was introduced through the 2019-20 interim Union Budget in February 2019. Initially covering small-scale farmers operating a land area up to 2 hectares, the PM-KISAN scheme has been extended to all farmers with land titles (ICRIER, 2020[22]; MAFW, 2020[41]; Economic Times, 2019[42]).

Other support to producers

The central government prioritised in 2019 the strengthening of farm producer associations (FPOs). In this sense, the 2019-20 Union Budget of July 2019 provided support for the creation of 10 000 new farm producer organisations, 80 livelihood business incubators (LBIs), and 20 technology business incubators (TBIs) assisting 75 000 entrepreneurs in the agro-food sector in rural areas (Ministry of Finance, 2019[43]). In addition, the budget allocation for the specific scheme supporting dairy cooperatives and FPOs in the dairy sector was increased thirtyfold (ICRIER, 2020[22]). In early 2019, the central government also designated 24 “production clusters”5 for tomatoes, onions and potatoes (TOP) under the scheme “Operation Greens”, launched by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MOFPI) at the end of 2018 to stabilise the supply and prices of TOP by promoting farmer producers organisations, agri-logistics, processing facilities and management skills. Under this programme, the Ministry is setting up a “trade map” for these three vegetables that would cover varieties, price trends, buyers, sellers and processors across the identified states to help link farmers with domestic and international markets (Times of India, 2019[44]).

The 2019-20 Union Budget introduced the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Pension Yojana programme, a voluntary and contributory pension scheme for small-scale farmers. The scheme is to provide a minimum monthly pension of INR 3 000 (USD 42) on attainment of 60 years of age, with an entry age of 18 to 40 years. The government of India co-finances the scheme6 with an approved budget of INR 108 billion (USD 1.4 billion) until March 2022, by then aiming to cover 50 million farmers (Ministry of Finance, 2019[43]).

The National Mission for Vegetable Oils was set up in May 2019 and aims to increase the domestic production of oilseeds. Support is to focus on farm inputs, higher minimum support prices for oilseeds, and increased procurement through state-run agencies (Cogedis, 2019[45]).

The Dairy Processing and Infrastructure Development Fund (DPIDF) scheme introduced in 2019 focuses on setting up chilling and processing infrastructure as well as milk adulteration electronic testing equipment. The scheme is co-funded by the government of India together with the National Bank of Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB), and the National Cooperative Development Corporation (NCDC) (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

The Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund (AHIDF) scheme introduced in 2019 focuses on setting up processing infrastructure in the livestock sector. The government of India supports the implementation of the scheme through NABARD for interest subvention (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

The government has also extended the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme – which has been providing subsidised interest rates for short-term formal credit to crop farmers – to farmers in the livestock and fisheries sectors (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

The National Animal Disease Control Programme for Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and Brucellosis, introduced in 2019, is a scheme fully funded by the union government that supports the vaccination of cattle, sheep and pigs as well as primary vaccination in calves (4-5 months of age) by 2025. The scheme covers the set-up of cold chain infrastructure for vaccines as well as extension services (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

The 2020-21 Union Budget introduced two new schemes supporting the cold chain and marketing of agro-food perishable goods. These include the Kisan Rail (‘Farmer rail’) that is to be funded by public-private partnerships – under the co-ordination of the Ministry of Railways – for transporting agro-food products by rail, and Krishi Udaan (‘Farmer flight’) that is to be co-ordinated by the Ministry of Civil Aviation for transporting such goods by plane domestically and internationally (The Print, 2020[29]).

Support to processors

In March 2019, CCEA announced subsidised interest rates amounting to INR 27.9 billion (USD 370 million) for loans to sugar mills under the new scheme providing financial assistance for the enhancement of ethanol production capacity (ICRIER, 2020[22]). In November 2019, the Union Cabinet extended the 18-month moratorium period (i.e. the time period during the loan term when the borrower is not required to make any repayment) by six more months for all existing loans to sugar mills supporting them to clear cane arrears with farmers and set up ethanol processing facilities (India Today, 2019[46]).

Agri-environmental linkages

The 2019-20 Union Budget allocated 0.1% of the agriculture budget for further pilots of ‘Zero Budget Natural Farming’ (ZBNF) across different parts of India that would allow gathering information on its viability and assessing the opportunities for scaling up its application. ZBNF is a method of chemical-free agricultural production drawing from traditional Indian practices,7 but there is a lack of evidence on the impacts of ZBNF across different Indian agro-ecological zones. In the 2020-21 Union Budget, envisaged steps on ZBNF are not defined, while the existing soil, water and organic farming schemes which would be equipped to respond to agri-environmental challenges and could be scaled up receive insufficient push forward (Ministry of Finance, 2019[43]; The Hindu, 2019[47]).

In spite of a proposal by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MEFCC) Expert Committee to include farmers with landholdings above five hectares and to introduce a “water credit” for users who conserve groundwater above a certain threshold, the agriculture sector was excluded from the levy of a Groundwater Conservation Fee (GWCF) introduced on 1 June 2019, to be paid by industry and domestic users for consumption beyond a certain limit (The Hindu Business Line, 2019[48]; The Times of India, 2019[49]). The MAFW has nevertheless presented in early January 2020 a five-year action plan aimed at lowering rice procurement from areas where rice cultivation contributed to severe groundwater levels depletion (The Print, 2020[50]).

Food subsidy and other support to consumers

In October 2020, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution set a deadline of 30 June 2020 for the full implementation of the “One nation, one ration card” programme under the Public Distribution System. This aims to address the problem of migrant beneficiaries who often cannot access the subsidised food grain quota due to the change in residence for employment purposes (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

The central government introduced the distribution of pulses to states/Union Territories (UTs) under the existing welfare schemes. The scheme would dispose pulses procured at MSP under PSS with a subsidy of INR 15 (USD 0.2) per kg over the issue price. The scheme is to be in place for either 12 months from the date of the first supply or until the present stock of 3.5 million tonnes is completely disposed of, whichever occurs earlier. The distribution of stocks shall be for utilisation under various welfare schemes such as mid-day meal, Integrated Child development services, Public Distribution System, etc. (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

Changes in food safety and labelling regulations

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) introduced new regulations in June 2019 with respect to specific labelling requirements. These concern more specifically the listing on food products of nutritional information, food ingredients and food additives (FSSAI, 2019[51]).

In August 2019, the FSSAI introduced amendments for a number of sections of the 2018 draft Food Safety and Standards (Licensing and Registration of Food Businesses) Regulations. Through some of the key amendments, the FSSAI aims to bring e-commerce food business operators (FBOs) under the purview of the licensing regulations. Other amendments introduced include the rationalisation of the fee structure charged for licences and registrations, as well as the simplification of the application processes for registration and licensing (FSSAI, 2019[52]).

Trade policy developments in 2019-20

Changes to tariff measures and other taxes on imports

On 26 April 2019, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) issued a Notification raising the most favoured nation (MFN) tariff for wheat from 30% to 40% (Ministry of Finance, 2019[53]). On 15 June 2019, the MOF raised the MFN tariff for lentils (masur) from 33% to 50% (Ministry of Finance, 2019[54]).

On 4 September 2019, and for a period of 180 days, the government of India introduced a 5% safeguard duty on palm oil originating in Malaysia and imported under the India-Malaysia Economic Comprehensive Agreement. The government notification refers to an increase in imports having “led to idling of significant capacities of the domestic industry during the period of [safeguard] investigation” (Ministry of Finance, 2019[55]).

On 15 June 2019, the MOF announced the implementation of the previously postponed increase in tariffs for 28 goods imported from the United States. In addition to non-agricultural products, these include shelled and in-shell almonds, in-shell walnuts, fresh apples and pulses, for which applied tariffs vary between 70% and 120% (Ministry of Finance, 2019[56]; LiveMint, 2019[57]).

In August 2019, the MAFW proposed the introduction of an additional 5% tax on edible oils imports that would finance a new Oilseeds Development Fund to support oilseeds producers, including through the National Mission for Vegetable Oils (see also section on “Other support to producers”) (Live Mint, 2019[58]).

Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs)

On 9 July 2019, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI) announced an additional Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) of 0.4 million tonnes of feed grade maize for poultry producers (MOCI, 2019[59]).

Export measures

Driven by a doubling of onion retail prices between July and September 2019 after severe floods in the states of Maharashtra and Karnataka, in mid-September 2019 the government of India initially introduced a minimum export price (MEP)8 for onions at USD 850 Free on Board (FOB) per tonne, followed at the end of September 2019 by an export ban on onions applied until 15 March 2020. In addition, the central government introduced limits on stocks held by private traders: retail traders across India were allowed to keep a maximum of 10 quintals (10 tonnes) in stocks, while wholesale traders were allowed to keep up to 500 quintals (50 tonnes) of onions (ICRIER, 2020[22]; Gulati and Wardhan, 2019[60]; Economic Times, 2019[61]; Economic Times, 2019[62]).

The CCEA approved on 28 August 2019 a sugar export subsidy of INR 10 448 (USD 141) per tonne to sugar mills starting in October 2019. The subsidy would support sugar mills liquidate surplus and clear sugar cane arrears to farmers. The subsidy is transferred directly to the farmers’ accounts on behalf of the mills against cane price dues, while mills have to provide transactions details to the government for transferring the money in proportion to the cane bought from farmers. The total budget allocated for the programme in marketing year 2019-20 is INR 62.7 billion (USD 876.7 million) (Economic Times, 2019[63]). The maximum admissible export quantity (MAEQ) allocated for sugar mills for the 2019-20 marketing season is of 6 million tonnes (ICRIER, 2020[22]).

On 31 October 2019, the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled that the export subsidy programme Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) violated provisions under the WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM). The ruling mainly concerned manufacturing goods. However, under the 2015-20 MEIS the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) had introduced a 7% export subsidy for chickpeas (between April and June 2018) and a 5% export subsidy for non-basmati rice (between November 2018 and March 2019) based on the FOB value of the products. While India appealed the WTO ruling in November 2019, the Indian Ministry of Finance had already announced in August 2019 that it would replace the MEIS with the Scheme for Remission of Duties or Taxes on Export Product (RoDTEP). Its entry into force was approved in March 2020, but the RoDTEP rates will be decided following specific industry consultations until the end of 2020, while MEIS is being phased out (Economic Times, 2020[64]) (Economic Times, 2019[65]; The Hindu Business Line, 2019[66]).

Eight states9 finalised action plans for the implementation of the Agriculture Export Policy (AEP) framework adopted by the government of India in December 2018. The eight state-level action plans finalised so far focus primarily on the exports-enhancing dimension of AEP through roadmaps for production clusters development, capacity building, and infrastructure and logistics. State-level monitoring committees were formed to oversee the implementation of AEP (Business Standard, 2020[67]).

Under the AEP, the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) set up a Farmer Connect Portal to provide a platform linking Farm Producer Organisations (FPOs) to exporters. In addition, a Memorandum of Understanding was concluded with the National Cooperative Development Corporation to provide co-operatives with an active role in implementing the AEP (Business Standard, 2020[67]).

References

[11] Bloomberg (2020), Indian Ports In Confusion as Virus Lockdown Hits Operations, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-25/indian-ports-declare-force-majeure-amid-national-virus-lockdown (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[20] Business Standard (2020), Foreign Trade Policy and Schemes to Be Extended for 6 Months, https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/foreign-trade-policy-schemes-to-be-extended-by-6-months-till-sept-30-120032701005_1.html (accessed on 31 March 2020).

[67] Business Standard (2020), To Double Exports, 8 States Finalise Action Plan for Agri-Export Policy, https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/8-states-finalise-action-plan-for-agri-export-policy-govt-120010500401_1.html (accessed on 15 January 2020).

[36] CACP (2020), Minimum Support Prices Recommended by CACP and Fixed by Government, https://cacp.dacnet.nic.in/ViewContents.aspx?Input=1&PageId=36&KeyId=0 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

[25] Climate Action Tracker (2018), Countries: India, http://climateactiontracker.org/countries/india.html (accessed on 15 January 2019).

[45] Cogedis (2019), Government to Launch New National Mission for Vegetable Oils to Stem Imports, http://www.cogencis.com/newssection/govt-to-launch-new-national-mission-for-vegetable-oils-to-stem-import/ (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[14] Dairy Global (2020), India’s Dairy Co-ops Urged to Ensure Milk Supply, https://www.dairyglobal.net/Milking/Articles/2020/4/Indias-dairy-cooperatives-urged-to-ensure-supply-of-milk-565060E/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

[13] Deccan Herald (2020), Coronavirus: Self-help Groups in Odisha, https://www.deccanherald.com/national/east-and-northeast/coronavirus-self-help-groups-in-odisha-manufacture-distribute-1-million-masks-821618.html (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[12] Economic Times (2020), About 1 600 Fruit and Vegetables Mandis Functioning: 300 More to Operate, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/india-lockdown-about-1600-fruit-vegetable-mandis-functioning-300-more-to-operate-from-friday-says-agri-min/articleshow/74833470.cms (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[64] Economic Times (2020), Cabinet Approves RoDTEP Scheme to Reimburse Taxes, Duties Paid by Exporters, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/cabinet-approves-rodtep-scheme-to-reimburse-taxes-duties-paid-by-exporters/articleshow/74612562.cms (accessed on 31 March 2020).

[16] Economic Times (2020), Cabinet Nod for Supply of 2 kg Extra Subsidised Foodgrains Via Ration Shops, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/cabinet-nod-for-supply-of-2kg-extra-subsidised-foodgrains-via-ration-shops/articleshow/74811711.cms (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[28] Economic Times (2020), Farm Leaders Disappointed With No Increase in PM Kisan Pay Out in Budget 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/farm-leaders-disappointed-with-no-increase-in-pm-kisan-pay-out-in-budget-2020/articleshow/73849055.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 10 February 2020).

[18] Economic Times (2020), Government to Give Extra 5 kg Grains, 1 kg Pulses for Free Under PDS for Next 3 Months, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/govt-to-provide-5-kg-grains-1-kg-pulses-for-free-over-next-3-months-fm/articleshow/74827003.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[15] Economic Times (2020), PDS Beneficiaries Can Lift 6-month Quota of Grains in One Go, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/pds-beneficiaries-can-lift-6-month-quota-of-grains-in-one-go-ram-vilas-paswan-amid-coronavirus-concerns/articleshow/74695460.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[62] Economic Times (2019), A Problem of Plenty: India’s Onion Mess, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/a-problem-of-plenty-indias-onion-mess/articleshow/71546979.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 6 January 2020).

[61] Economic Times (2019), Government Bans Onions Exports With Immediate Effects, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/government-bans-onion-exports-with-immediate-effect/articleshow/71359514.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[42] Economic Times (2019), Government Notifies Extension of PM-KISAN Scheme to All Farmers, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/government-notifies-extension-of-pm-kisan-scheme-to-all-farmers/articleshow/69702953.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[32] Economic Times (2019), Group of Ministers Set Up to Review Crop Insurance Scheme, https://m.economictimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/group-of-ministers-set-up-to-review-crop-insurance-scheme/articleshow/73003204.cms (accessed on 15 january 2020).

[65] Economic Times (2019), India Loses Export Incentive Case Filed by US at WTO, to Appeal Against the Ruling, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/wto-panel-rules-india-export-subsidies-illegal-upholds-u-s-case/articleshow/71841672.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 5 January 2020).

[33] Economic Times (2019), IRDA Rejects Risk Pool Proposal for Crop Insurance, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/irda-rejects-risk-pool-proposal-for-crop-insurance/articleshow/72575254.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 20 January 2020).

[63] Economic Times (2019), Sugar Industry Gets Rs 6,268 crore Export Subsidy, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/sugar-industry-gets-rs-6268-crore-export-subsidy/articleshow/70885051.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 15 December 2019).

[52] FSSAI (2019), Food Safety and Standards Regulations, https://www.fssai.gov.in/cms/food-safety-and-standards-regulations.php (accessed on 15 December 2019).

[51] FSSAI (2019), FSSAI’s New Labelling and Display Regulations, https://fssai.gov.in/upload/press_release/2019/06/5d144d6a64d6dPress_Release_Labelling_Regulations_27_06_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[38] GAIN-IN0091 (2019), Sugar Semi-annual.

[40] GAIN-IN0095 (2019), Grain and Feed Quarterly Update.

[6] Government of India (2020), Finance Minister Announces Several Relief Measures, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1607942 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[3] Government of India (2020), Government Gives Benefits to Farmers on Crop Loan Repayments Due to Covid-19 Lockdown, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200815 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[8] Government of India (2020), Indian Railways to Run Special Parcel Trains for Carriage of Essential Items in Small Parcel Sizes, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200787 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[10] Government of India (2020), Ministry of Shipping issues Direction to All Major Ports, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200867 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[17] Government of India (2020), Rs 1.70 Lakh Crore Relief Package under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana for the Poor, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608345 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[7] Government of India (2020), Transportation/Interstate Movement of Animal Feed, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200793 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[30] Government of India (2019), High Powered Committee of Chief Ministers Constituted for ’Transformation for Indian Agriculture’, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=191070 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

[26] Gulati, A. (2019), With Little Allocation for Agriculture, Budget Sends a Worrying Signal, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/not-for-the-farmer-budget-2019-nirmala-sitharaman-5817671/.

[68] Gulati, A. and P. Banerjee (2020), “Goal Setting for Indian Agriculture”, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. 55/9.

[23] Gulati, A., D. Kapur and M. Bouton (2020), Reforming Indian Agriculture.

[60] Gulati, A. and H. Wardhan (2019), How Government Can Control Sudden Spike in Prices of Onion and Tomato, https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/how-govt-can-control-sudden-spike-in-prices-of-onion-and-tomato/1734377/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

[5] Hindustan Times (2020), High-tech Farm Management System, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/high-tech-farm-management-system-on-anvil/story-6ecxcbGQZxm37uDYI7mozN.html (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[22] ICRIER (2020), Background Analysis for the 2020 Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation Report.

[19] IFPRI (2020), How India’s Food-Based Safety Net is Responding to the COVID-19 Lockdown, https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-indias-food-based-safety-net-responding-covid-19-lockdown (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[46] India Today (2019), Government Extends Moratorium Period by 6 Months on Soft Loan to Sugar Mills, https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/govt-extends-moratorium-by-6-months-on-rs-15-000-crore-soft-loan-to-sugar-mills-1618554-2019-11-13 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[58] Live Mint (2019), How India Plans to Reduce Its Edible Oil Import Dependency, https://www.livemint.com/industry/agriculture/how-india-plans-to-reduce-its-edible-oil-import-dependency-1567748829520.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[31] LiveMint (2020), Budget 2020: Full Text of Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget Speech, https://www.livemint.com/budget/news/budget-2020-full-text-of-nirmala-sitharaman-s-budget-speech-11580547114996.html (accessed on 10 Feburary 2020).

[34] LiveMint (2019), Crop Insurance Flaws Fuel Farm Distress, https://www.livemint.com/news/world/crop-insurance-flaws-fuel-farm-distress-11574185759756.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

[57] LiveMint (2019), India’s Retaliatory Tariffs on 28 U.S. Products Come Into Effect, https://www.livemint.com/politics/policy/india-imposes-tariffs-on-28-us-goods-as-global-trade-war-heats-up-1560616982719.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

[41] MAFW (2020), PM-KISAN, https://www.pmkisan.gov.in/ (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[39] MCAFPD (2019), Government Hikes Minimum Selling Price of Sugar for 2019-20, https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1564670 (accessed on 6 January 2020).

[43] Ministry of Finance (2019), Economic Survey 2018-2019.

[55] Ministry of Finance (2019), Notification No. 29/2019 - Customs, http://www.cbic.gov.in/resources//htdocs-cbec/customs/cs-act/notifications/notfns-2019/cs-tarr2019/cs29-2019.pdf;jsessionid=450082A946E0C4E7454B971D4239675E (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[53] Ministry of Finance (2019), Notification No.13/2019 - Customs, http://www.cbic.gov.in/resources//htdocs-cbec/customs/cs-act/notifications/notfns-2019/cs-tarr2019/cs13-2019.pdf;jsessionid=2E2680404ABB35A6DDA161530077F512 (accessed on 18 December 2019).

[54] Ministry of Finance (2019), Notification No.16/2019 - Customs, http://www.cbic.gov.in/resources//htdocs-cbec/customs/cs-act/notifications/notfns-2019/cs-tarr2019/cs16-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).

[56] Ministry of Finance (2019), Notification No.17/2019 - Customs, http://www.cbic.gov.in/resources//htdocs-cbec/customs/cs-act/notifications/notfns-2019/cs-tarr2019/cs17-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).

[59] MOCI (2019), Trade Notice No. 33/2019, http://dgft.gov.in/sites/default/files/scan0015.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[21] OECD/ICRIER (2018), Agricultural Policies in India, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302334-en.

[2] Outlook India (2020), Government to Transfer INR 2 000 Under PM-KISAN, https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/govt-to-transfer-rs-2000-under-pmkisan-scheme-to-869-cr-farmers-in-april-1st-week/1780614 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

[27] PRS India (2019), Union Budget 2019-20 Analysis, https://prsindia.org/parliamenttrack/budgets/union-budget-2019-20-analysis (accessed on 21 January 2020).

[24] Reserve Bank of India (2019), Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit, https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=942 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

[47] The Hindu (2019), What is Zero Budget Natural Farming?, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/agriculture/what-is-zero-budget-natural-farming/article28733122.ece (accessed on 15 January 2020).

[37] The Hindu Business Line (2019), Cabinet Retains Sugarcane FRP at INR 275 a Quintal, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/govt-keeps-sugarcane-price-unchanged-at-rs-275quintal-for-2019-20/article28700196.ece (accessed on 10 December 2019).

[66] The Hindu Business Line (2019), Centre May Retain Export Scheme MEIS Till March 2020, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/policy/centre-considers-option-of-continuing-popular-meis-scheme-for-entire-fiscal/article29758344.ece (accessed on 5 January 2020).

[48] The Hindu Business Line (2019), it’s Time to Overhaul Water Pricing Norms, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/its-time-to-overhaul-water-pricing-norms/article27071838.ece (accessed on 15 January 2020).

[35] The Indian Express (2019), Livestock Sector: A New ministry promises a new beginning, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/livestock-sector-a-new-ministry-promises-a-new-beginning-5849379/ (accessed on 20 December 2019).

[29] The Print (2020), A 16-point Agenda to Double Farmer Income & Boost Agriculture, but Only 3% Jump in Outlay, https://theprint.in/india/budget-2020-16-point-agenda-double-farmer-income-3-jump-agriculture-outlay/358484/ (accessed on 5 February 2020).

[50] The Print (2020), Nudge Didn’t Work, Agriculture Ministry Now Has a Plan to Force Paddy Farmers to Diversify, https://theprint.in/india/governance/nudge-didnt-work-agriculture-ministry-now-has-a-plan-to-force-paddy-farmers-to-diversify/344974/ (accessed on 16 January 2020).

[9] The Straits Times (2020), Supply Chaos and Fears of Food Shortages in India Amid Coronavirus Lockdown, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/supply-chaos-and-fears-of-food-shortages-in-india-amid-coronavirus-lockdown (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[49] The Times of India (2019), Government Proposes ’Water Fee’ Strict Regulations to Conserve Groundwater, https://weather.com/en-IN/india/news/news/2019-07-25-government-proposes-water-fee-strict-regulations-conserve-groundwater (accessed on 20 January 2020).

[4] Times of India (2020), Every Grain Will Be Procured, Center Assures Farmers, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/not-a-single-grain-produced-by-farmers-to-be-left-without-being-procured-says-agri-minister/articleshow/75087196.cms (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[1] Times of India (2020), Govt Relaxes Norms for Agriculture and Farming Sector, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/coronavirus-lockdown-govt-relaxes-norms-for-agriculture-and-farming-sector/articleshow/74983439.cms (accessed on 10 April 2020).

[44] Times of India (2019), 24 Clusters of Tomatoes, Onions and Potatoes in 2019 to Enhance Farm Income, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/24-clusters-for-tomatoes-onions-and-potatoes-in-2019-to-enhance-farm-income/articleshow/67330871.cms (accessed on 15 January 2020).

Notes

← 1. These replaced the former five-year plans prepared by the erstwhile Planning Commission of India (the 12th Five Year Plan 2012-17 was the last of these plans).

← 2. A Ministerial Decision on Export Competition at the WTO Ministerial Conference held in Nairobi in 2015 has put an end to the subsidisation of agricultural exports, which for India would occur at the end of 2023 (https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/l980_e.htm).

← 3. As per the Union Budget 2020-21, the cumulative loans from all sources at the end of 2019-20 stand at INR 33 trillion (Gulati and Banerjee, 2020[68]).

← 4. INR 2.75 per quintal (USD 0.39 per tonne) for every 0.1% increase above the basic 10% recovery rate (i.e. defined by the CCEA as the amount of sugar produced by crushing a given amount of sugarcane by weight).

← 5. Here, a ‘production cluster’ represents a geographic concentration of small-scale farmers joined through an association in order to receive financial support under the programme.

← 6. Participating farmers are to contribute between INR 55 to INR 200 (USD 0.8 to USD 2.8) depending on the age of entry.

← 7. ZBNF was originally promoted by Subhash Palekar, who developed it in the mid-1990s as an alternative to the Green Revolution’s methods driven by chemical fertilisers and pesticides and intensive irrigation. He argued that the rising cost of these inputs was a leading cause of farmer indebtedness and suicide, while the impact of chemicals on the environment was devastating. He thus considered that without the need to spend money on these inputs – or take loans to buy them – the cost of production could be reduced and farming transformed into a ‘zero budget’ exercise.

← 8. This represents the price below which exporters are not allowed to export a specific commodity. It is set taking into consideration concerns about the domestic prices and supply of that specific commodity.

← 9. Assam, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Nagaland, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/928181a8-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.