New Zealand

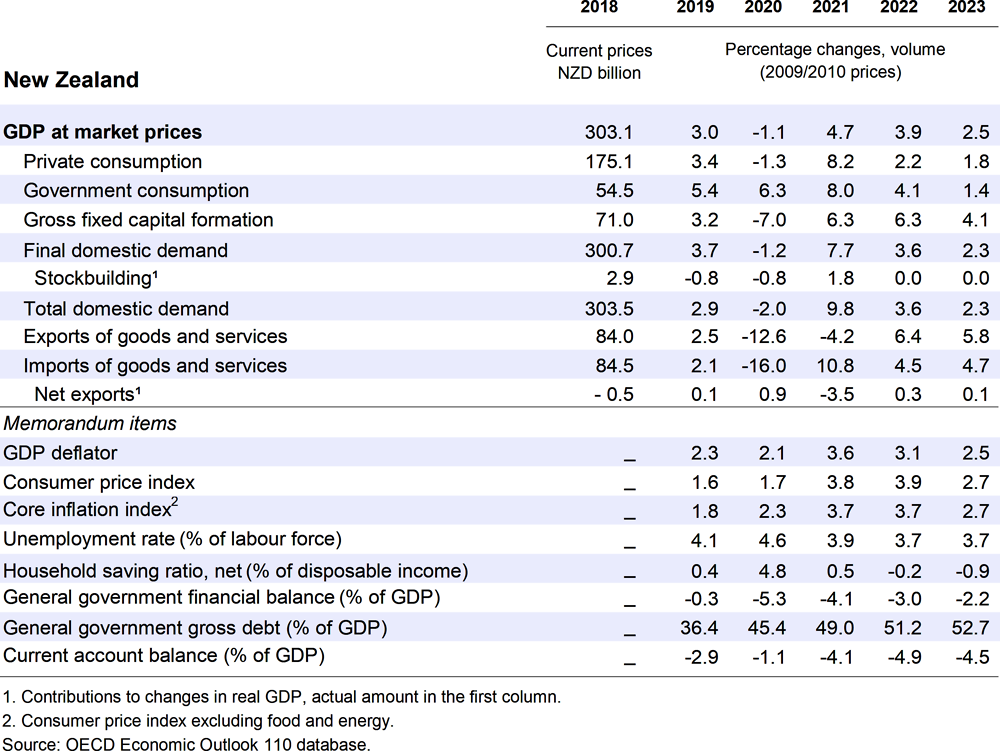

Economic growth should reach 4.7% in 2021, reflecting the bounce-back from the disruption caused by the pandemic, but will slow to 3.9% in 2022 and 2.5% in 2023 as macroeconomic policies tighten and capacity constraints are alleviated only gradually after the border begins to re-open in early 2022. Inflationary pressure will remain strong, as the economy continues to run above capacity and the labour market remains very tight, boosting wages. Growth may slow more markedly if vaccination delays among some population groups were to push back border re-opening.

Successful COVID-19 containment and border re-opening require vaccinating population groups that lag behind and boosting the medical sector’s capacity to cope with a higher occurrence of acute infection cases. Macroeconomic policies should be tightened faster if high inflation persists. Housing policy reforms concerning planning, infrastructure and social housing are needed to increase supply of more affordable housing.

As New Zealand prepares to re-open, its economy is overheating

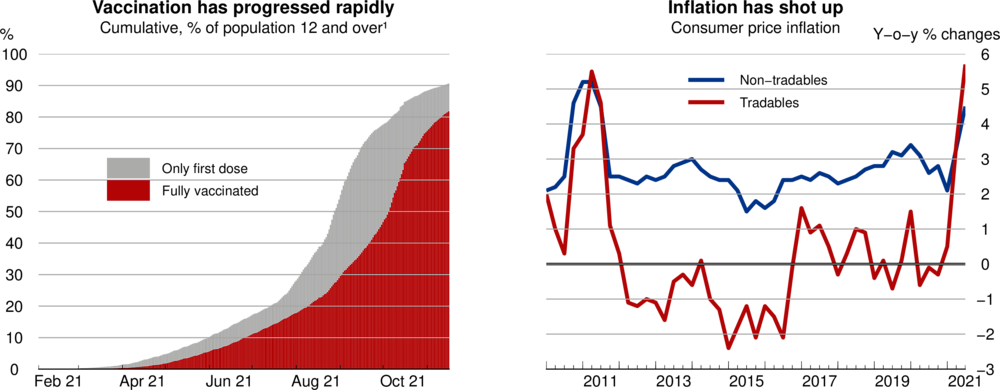

New Zealand’s COVID-19 strategy has shifted from elimination to minimisation of community infection cases and protection, including swift vaccination of its population. The response framework that relied on lockdowns was replaced at the beginning of December by a new framework that allows businesses requiring vaccination certificates to operate with few or no restrictions under moderate community infection and pressure on the healthcare system. The government also reduced the number of days that vaccinated travellers entering New Zealand must spend in Managed Isolation and Quarantine (MIQ) facilities and announced that self-isolation for seven days would replace MIQ stays for fully vaccinated New Zealand citizens and residents from early 2022 and fully vaccinated foreign nationals from 30 April. Over 80% of the eligible population has been fully vaccinated so far, but a delay in take-up among some population groups has been a challenge. The government has mandated workers in health, educational and correctional sectors as well as border workers to get vaccinated. It has also introduced electronic vaccination certificates for accessing large events, enclosed public spaces and international travel.

The economy grew strongly in the first half of 2021, driven by robust private consumption, investment and commodity exports. The quarantine-free travel arrangement with Australia initiated in April 2021 also boosted service exports, but was suspended in June. Employment soared in the year to the third quarter, lifting the employment rate to a record high and cutting the unemployment rate to 3.4%, the lowest since 2007. Consumer price inflation shot up to 4.9% in the year to the third quarter, driven by an increase in housing-related costs and high oil prices and transportation costs. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s preferred estimate of core inflation rose to 2.7%, close to the upper bound of its inflation target band (1% to 3%). The economy is likely to have contracted more than 5% in the third quarter owing to the lockdown of Auckland and nearby regions and suspension of the travel arrangement. However, a rebound is expected in the fourth quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022 as confinement measures ease. Business confidence remains robust and hiring intentions are the highest since 1995.

Macroeconomic policies are being tightened

The Reserve Bank has started withdrawing some of the highly expansionary monetary stimulus that contributed to the swift economic recovery, but also fuelled house price inflation, which reached 30% in the year to the second quarter of 2021. The Reserve Bank increased its policy rate by two successive 25 basis point steps in October and November, to 0.75%, and is projected to raise it to 2% by early 2023. The Large Scale Asset Purchase programme was halted in July, after purchasing government bonds amounting to 16% of GDP. The Reserve Bank also tightened macro-prudential policy to contain the impacts of house price inflation on the economy. It reinstated loan-to-value ratio restrictions for mortgage lending in March 2021 and tightened them for investors in May and for owner-occupiers in November. It is also considering introducing debt serviceability restrictions to reduce the risk of borrowers being unable to service their debts. The fiscal stance is likely to have been neutral in 2021, as some of the operational expenditure meant to have occurred in fiscal year 2020 was shifted to 2021 and tax expenditure measures introduced in 2020 as part of the COVID-19 response came into force. The fiscal stance will be contractionary in 2022 and 2023, as COVID-19-related spending is phased out. Nevertheless, some fiscal stimulus will be provided by large infrastructure investments in the pipeline, such as “shovel-ready” projects amounting to 0.8% of GDP that are being rolled out until 2022. The NZD 12 billion New Zealand Upgrade Programme and the NZD 3.8 billion of housing-related infrastructure investment (together amounting to about 5% of GDP) will also be implemented over a longer period. The fiscal stance should be tightened more rapidly to avoid concentrating the burden of macroeconomic stabilisation on monetary policy.

Economic growth will moderate but remain robust

House price inflation that boosted private consumption through its wealth effect will moderate, due to tighter lending regulations, higher mortgage lending rates and the increase in housing supply implied by the record high issuance of residential building consents. Private consumption will nevertheless be supported by strong earnings growth. The progressive easing of border restrictions from early 2022 will alleviate labour shortages only gradually, in part owing to more restrictive immigration policies. It will allow the tourism sector, which accounted for 20% of exports prior to the pandemic, to recover, and boost investment by removing uncertainties and costs associated with international business. Aside from a delay in border re-opening, a sharp economic slowdown in China would hold back growth by reducing exports and food commodity prices. Conversely, larger than foreseen inflows of migrant workers would alleviate labour shortages and allow the economy to grow faster. The annual consumer price inflation rate is projected to remain above 4% until mid-2022, after which it will gradually decline as temporary effects from high fuel prices and supply chain disruptions pass.

Public health and housing reforms are needed to sustain economic growth and improve well-being

The number of intensive-care beds and ventilators and qualified personnel to operate them should be increased in order to cope with community infection. Urban planning reforms and measures to reduce financial barriers to increasing the supply of urban infrastructure are boosting housing supply but need to be taken further. Urban planning regulations should be reformed to require city councils in the five largest cities to allow medium-density housing on all residential land without having to go through a resource consenting process. Furthermore, city councils’ ability to restrict high-density housing in city centres and close to transport hubs should be curtailed. To increase investment in housing-related infrastructure, the government should identify and remove unwarranted barriers to Special Purpose Vehicles for financing such infrastructure and strengthen city councils’ incentives to accommodate growth. Substantially increasing the supply of social housing would improve housing affordability for low-income households and reduce child poverty.