10. Promoting investment for green growth

This chapter describes Thailand’s policy framework to support investment for green growth, providing an overview of the state of play and progress made in supporting green investment. It is structured around the questions on green growth and investment raised in the updated OECD Policy Framework for Investment and the OECD Policy Guidance for Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure. It also builds on the discussions on policy choices to support the transition to a low-emissions, climate-resilient economy in OECD (2017) Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth. The chapter reviews the current policy framework in place to promote green growth and climate change, including policies that help to improve the environmental quality of investments in general, and examines existing efforts to engage the private sector to scale up investment in renewable energy. It also highlights issues related to financing green projects in the country.

Green growth and green investment will be key to meeting the vision for Thailand 4.0, especially in the context of COVID-19 recovery. A green growth pathway allows Thailand to grow and develop while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide resources and environmental services for future generations, and that growth pathways remain resilient to global shocks such as climate change or future pandemics. A key step in pursuing green growth is to catalyse investment and innovation in environmentally sound technologies and infrastructure which helps to sustain growth, gives rise to new economic opportunities and promotes green jobs (OECD, 2011). In addition, with the increasing need for global action to address climate change, investment for green growth must promote a rapid transition to a low-emissions and climate resilient development pathway (OECD, 2017a). Investment for green growth includes, among other things, investment in infrastructure – such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, water purification and distribution systems, transport and housing – as well as in conservation and efficient usage of natural resources, and waste management (OECD, 2015b).

A green investment framework has much in common with a general policy framework for investment, but an investment-friendly policy framework does not necessarily result in green investment unless certain elements are also in place. These include: a strong governmental commitment at both the national and international levels to support green growth and to mobilise private investment for green growth; policies and regulations to provide a level playing field for more environment friendly investments, such as through the use of pricing instruments; policies to encourage more environmentally responsible business conduct (also see Chapter 9); an institutional capacity to design, implement and monitor policies to foster green growth objectives; and financial mechanisms for green investment (OECD, 2015a).

Thailand’s vision of transitioning its economy into an innovation and technology driven ‘Thailand 4.0’, especially through its ‘bio, circular and green (BCG)’ economy model will not be achievable without significant progress towards green growth. This is especially relevant in the context of post-COVID recovery, where Thailand must restart its economy and create local employment, while ensuring underlying growth drivers remain resilient to future shocks. The major gains made in growth and development in the last few decades were accompanied by the unstainable and unchecked use of resources, which in turn has hampered the country’s efforts to promote environmental sustainability. Rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and infrastructure development have exacerbated air and water pollution, with Bangkok recording hazardous levels of air pollution in the last two years. Thailand generates significant waste, and a lack of adequate waste management continues to result in plastics dumping and pollution in water bodies. Climate change exacerbates existing environmental issues, with Thailand highly vulnerable to changing temperature and rainfall patterns. Increasing greenhouse gas emissions from the use of fossil fuels will need to be checked.

Recognising these challenges, Thailand has made great strides in developing a comprehensive and consistent policy framework for green growth and environment and in promoting green investment. The BCG economic model puts green growth-related concepts at the heart of continued development. Green growth is reflected in Thailand’s development strategies, and consistent climate mitigation targets are in place. Thailand’s policy framework for environmental protection has a long history of implementation, and investment incentives have been put in place to promote investment in green sectors and activities. In the energy sector, Thailand is a regional success story in promoting private investment for renewable energy, and has used public finance strategically to mobilise commercial financing for green investments.

Thailand’s focus must be on implementing and strengthening the policies on green growth that are in place. Key to this will be ensuring that environmental objectives are systematically integrated across Thailand’s broader policy framework for investment. Some of the proposed actions can be addressed unilaterally by relevant agencies (short- and medium-term priorities), while others require longer term and inter-ministerial coordination.

Policy recommendations

Short- and medium-term policy priorities:

Consider scaling down or phasing out investment incentives for ‘non-green’ activities such as the manufacturing of non-biodegradable plastics or generation of electricity using fossil fuels. Providing incentives to both green and non-green activities reduces the ultimate effectiveness of efforts to promote green investment. For example, gains made by promoting investment in green sectors, such as the manufacturing of biodegradable plastics or generation of renewable energy, are negated by promoting investment in non-biodegradable plastic packaging or coal-fired power. A possible first step could include a mapping of green and ‘non-green’ activities building on emerging taxonomies for green finance.

Assess the applicability of creating targeted financing vehicles to mobilise financing for green investment beyond the energy sector, building on lessons learned from the Energy Efficiency Revolving Fund. Thailand has had success with using budget funds in specialised structures to encourage local banks to engage in green lending for energy, and such experience could be built on to promote green lending for waste, water, and transport projects.

Long-term policy priorities:

Establish a legal system for the application of Strategic Environmental Assessments, so that environmental considerations can be systematically integrated along with social and economic considerations in policy planning and decision making related to sectoral or geographical issues. This can also help avoid downstream conflict with local communities and other actors during the project environmental impact assessment stage. Risk-based responsible business conduct due diligence, according to international standards such as the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, should be actively encouraged and promoted.

Consider introducing pricing instruments, such as an environmental or ‘green’ tax, to put a price on pollution and incentivise efforts to increase the efficiency of resource use. Such instruments are considered key to green growth policies globally, and help to shift producer and consumer behaviour towards more environmentally beneficial activities. These taxes are prevalent across most OECD countries, with environmental tax revenues estimated to represent, on average, 2% of GDP across OECD member countries. Thailand should also continue its efforts to develop other pricing instruments by scaling up recent pilots to establish an emissions trading system.

Develop a roadmap to support greening of the national financial system, including the tracking and disclosure of ESG risks and impacts (see also Chapter 9). Building on the new roadmap on sustainable capital markets, Thailand should continue to invest in building a cohesive framework, through its sustainable finance taskforce and working group, bringing together the financial sector, the insurance sector and listed companies, to encourage more targeted performance on green finance and the SDGs. While efforts to establish a system for green bonds are beginning to pay off, a national standard or taxonomy, based on the ASEAN Green Bond Framework and national guidelines, could add further transparency for issuers and investors. Lessons can be learned from the EU Action Plan on Sustainable Finance which lays out a roadmap for greening EU’s financial system, including a taxonomy, labelling for financial products and measures to increase the transparency of reporting. Another example is China’s guidelines for establishing a national green finance system, which includes a classification of eligible activities and promotes clear reporting of green credits, among other measures. OECD tools for responsible business conduct in the financial sector can be useful for these efforts.

Growth has come at the cost of growing emissions and pollution

While Thailand’s economic growth has slowed in the last decade, the country has made strides in reducing poverty and promoting socio-economic development. People living in poverty fell from 67% in the mid-1980s to 10.4% in 2014, with close to 27 million people estimated to have moved out of poverty during this period (World Bank, 2018). Major improvements have been made in accessibility of water and sanitation services, as well as in promoting connectivity across the country. However, as for neighbouring ASEAN countries, growth and development has come at the cost of environmental performance and if left unabated, Thailand’s environmental concerns will affect its efforts to promote sustainable development going forward.

Rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and infrastructure development have exacerbated air and water pollution. Thailand’s urban population has grown from 31% in 2000 to 49% of the total population in 2019, with roughly a fifth of its population residing in and around the Bangkok in 2014 (OECD, 2015a). Air pollution has been increasing year on year, with hazardous pollution in Bangkok in 2018 and 2019 resulting in a closure of businesses and schools.1 Major air pollutants in big cities of Thailand are PM2.5, PM10 and Ozone. In 2018, the level of PM2.5 in Bangkok and PM10 in Saraburi sometimes exceeded the national standards while the ozone level in Songkhla increased. Transport is a major source of pollution in urban areas – the number of vehicles registered in Bangkok, for example, almost doubled from 4.5 million to 9.4 million between 2000 and 2016 (OECD, 2018a). Other major sources of poor air in urban areas include particulate matter from construction of buildings as well as industry (e.g. cement, stone quarries etc.), while in rural areas forest fires and agricultural burning contribute extensively to haze.

Unstainable resource use practices also exacerbate water and land pollution and threaten ecosystem health. Thailand generates more municipal solid waste than in many comparator countries (Figure 10.1), and a lack of proper waste management and disposal is a major cause of pollution. In 2018, an estimated 27% of municipal solid waste was disposed of improperly, through illegal burning or dumping on land and in water bodies (Pollution Control Department, 2019). Marine plastic pollution has affected the quality of Thailand’s beaches and coastline, and moreover, Thailand is one of five countries responsible for over half of all land-based plastics in the ocean globally (McKinsey and Ocean Conservancy, 2015). Another persisting environmental challenge is a loss of biodiversity, despite Thailand having made major strides in improving forest cover. Many of the country’s species face extinction, largely driven by land use change, illegal trafficking of wildlife and pollution.

Thailand remains especially vulnerable to climate change

Alongside regional neighbours Myanmar, Viet Nam and Philippines, Thailand is highly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. The Global Climate Risk Index ranks Thailand as eighth out of the ten most affected countries in the world to extreme weather-related events between 1999 and 2018, with resulting losses estimated at almost 1% of GDP, per year, over the same period (Eckstein et al., 2019). A historical increase in average annual temperatures and rainfall has been seen in the country over the last decade, and future projections show these will only continue (World Bank, 2020). Annual temperatures are expected to increase by between 1.4 to 1.6°C by the 2060s, and average annual rainfall by between 28% and 74% by the 2090s. The agriculture sector is expected to bear the brunt of the impact, affecting the livelihoods of farmers and rural communities. Expected sea level rise is of concern considering the location of Bangkok and key industries along the exposed coastline of the country. Recognising these challenges, investment in climate change adaptation should be a priority for public investment in climate change.

At the same time, Thailand’s must continue to transition to a low-carbon development pathway, and equal efforts are needed to invest in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Net greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels and land use change have remained relatively stable over the last decade, as Thailand’s efforts to promote reforestation and improve carbon sinks have largely offset increasing emissions. However, in absolute terms, greenhouse gas emissions from the use of fossil fuels have risen alongside growth and development. Per capita CO2 emissions from the use of fossil fuels have increased by almost 60% between 2000 and 2018 (Figure 10.2). At the same time, the CO2 intensity of Thailand’s economy has also improved significantly.

Investing in green growth is key to achieving the vision of Thailand 4.0

The vision of ‘Thailand 4.0’ is an economic growth model that supports continuing growth and development, while promoting greater economic efficiency and modernisation. Greening growth to reduce the unsustainable use of resources and pollution and addressing climate change will be key to this vision. Infrastructure development, especially in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), is a flagship of the Thailand 4.0 framework. Thailand currently faces an overall gap in infrastructure investment. Cumulative infrastructure investment needs for the country are estimated at USD 494 billion between 2016 and 2040, and considering current investment levels, Thailand faces a shortfall of USD 100 billion over the same period (Oxford Economics, 2017). Green investment from public and private sources will need to be scaled up, especially for green infrastructure.

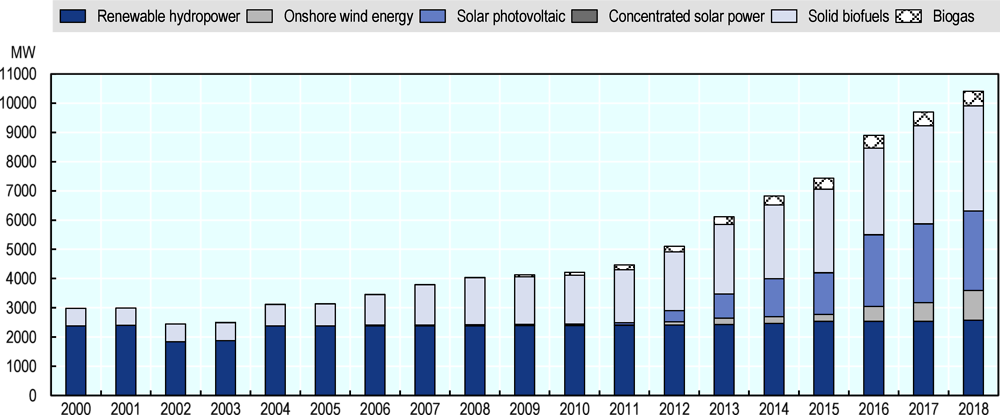

The need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution, increase the efficiency of resource use and support the management of natural capital all provide potential opportunities for investment. Renewable energy, for example, has attracted significant interest from private investors in recent years. Installed power generation from renewable energy sources like wind, solar, biomass etc. has tripled in the last two decades, increasing from 2986 MW in 2000 to 10,410 MW in 2018 (Figure 10.3) (IRENA, 2019). There is still significant potential to scale up green investment for renewables, with an estimated USD 1.3 billion annual investment needed by 2036 to deliver on the government’s renewable energy targets (IRENA, 2017). Increasing energy demand presents another opportunity to scale up investments in energy efficiency in buildings and industry. Final energy consumption in Thailand grew at 5% per year between 1990 and 2015, and is projected to continue growing at just under 3% per year up to 2040 (Padrem, 2019). The sectors with the highest potential to achieve energy savings are transport and industry.

A strong government commitment to support green growth, underpinned by a coherent policy framework and clear targets, provides investors with encouraging signals regarding the government’s ambitions for green growth. Setting clear, long term, and legally binding policy and regulatory frameworks to mainstream and encourage green growth are key to attracting private investment. Such frameworks are critically important to mitigate the risks related in investment in green infrastructure and new technologies. Such a framework should include a comprehensive and coherent framework of policies related to the environment and green growth, integrating of environmental targets and ambitions into sector policies and plans, and engagement and commitments towards multilateral environmental agreements.

Green growth and climate change policy framework

Thailand’s development plans emphasise green growth

Thailand has put in place a comprehensive policy and regulatory framework to promote green growth and environmental sustainability. The cornerstone of efforts in this area are Thailand’s long-term (20-year) Policy and Prospective Plan for Enhancement and Conservation of National Environment Quality 2017-37 and its medium-term (5-year) Environment Quality Management Plan (EQMP) 2017–22. The 2017-22 Plan specifies a vision to have ‘good environment quality’ as a step towards green growth.

The importance of green growth is also well reflected in the 20-year National Strategy (2018-2037) with its national slogan ‘Security, Prosperity, Sustainability’. The strategy promotes the idea of ‘Thailand 4.0’ and is an effort to move future growth from heavy and light industry to industries dependent on innovation and digital technologies (see Chapter 2 for an overview). Promoting environmental protection is one of four objectives of this strategy, with an emphasis on promoting low-carbon development and smart cities. The government’s ‘bio, circular and green (BCG)’ economy model includes a clear focus on green growth and environmental sustainability, building on the long established ‘Sufficiency Economy’ principles that have guided development strategies in the past.

Green growth is also clearly mentioned in the 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017-22) where one of five objectives of the plan is to ‘preserve and restore natural resources and environmental quality in order to support green growth’. Under the 12th Plan, the Strategy for Environmentally-friendly Growth for Sustainable Development outlines the government’s overarching plans on the environment and is the cornerstone of efforts to promote green growth. Recognising both the progress made – such as in reducing deforestation – and continuing environmental challenges, the strategy outlines four areas of focus for the country in 2017-22. These include conservation of natural resources and biodiversity, management of water resources, reducing environmental pollution and managing waste, and addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation. Key targets in the strategy include forest cover (to ensure that forest cover is 40% of land area), waste management (at least 75% of waste generate by communities properly treated or reused), on water and air quality (air quality in haze crisis zones to fall within national pollution standards) and on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Promoting private investment and encouraging environmentally friendly businesses are emphasised throughout the strategy. For example, the sustainable use of biodiversity by promoting value creation from biodiversity resources is emphasised alongside conservation. Similarly, there is a focus on green labelling and on fiscal reform to promote environmental protection. Green growth is also encouraged through Thailand’s Sustainable Consumption and Production Roadmap 2017-2036 which includes actions to strengthen the sustainability of Thai production (for example, by promoting resource use efficiency across companies and communities) as well as consumption (for example, by promoting green labelling, green public procurement etc.).

Despite a consistent overarching framework in place to promote environmental sustainability and green growth, a more systematic consideration of alignment of development plans and policies with environmental objectives is needed. For example, incentives to promote car ownership could undermine the ambitions on reducing air pollution in the 12th Plan (Sondergaard et al., 2016). Similarly, while promoting projects in the EEC, a strategic environmental assessment could prevent conflict at the project level. Currently, the Board of Investment (BOI) already has in place screening processes when considering investment projects. For example, investors are required to provide a preliminary assessment of environmental impact when submitting a proposal, and are encouraged to use new machinery or equipment, or justify the use of used equipment. Such criteria and processes could be built on to support further greening of the EEC.

Consistent climate targets define Thailand’s mitigation ambition

Thailand’s policy framework for climate change is centred around its Climate Change Master Plan (2015-2050) which has been integrated into national plans such as the 20-year National Strategy, the National reform Plans and the 12th Plan. Mitigation and adaptation actions are emphasised equally. Through these plans, Thailand committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from energy and transport sectors by 7% by 2020 against a Business As Usual (BAU) scenario, and in 2018, it was reported that this target had been met early (Office of Natural Resource and Environmental Policy and Planning, 2017). In its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) submitted to the UNFCCC in 2015, Thailand committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions reductions by 20% by 2030, or 25% by 2030 with adequate international support and technology transfer. This target will be implemented through an NDC Mitigation Roadmap and specific plans for transport, energy, waste and industry sectors. Thailand has also made headway in promoting climate change adaptation through its National Adaptation Plan, and sectoral plans in target sectors (e.g. health, agriculture). Compared to neighbouring ASEAN countries (Table 10.1), Thailand has adopted an ambitious greenhouse gas reduction target based on voluntary national actions (i.e. not conditional on external support).

Pricing instruments, such as environmental taxes, could help put a price on pollution

Pricing-related policy instruments – such as environmental taxes – are key to promoting green growth as they drive broad actions to reduce environmental damage and provide incentives to increase efficiency, promote green investment and encourage innovation (OECD, 2015c). Environmental taxes ensure that market prices reflect costs related to environmental damages and helps to shift producer and consumer behaviour towards more environmentally beneficial activities. Environmentally related taxes are relatively common across OECD, with revenues from these taxes estimated to represent, on average, 2% of GDP (OECD, 2015c and 2017b). In some countries, such as Denmark and the Netherlands, this share is higher, over 3.5% of GDP. Within Southeast Asia, Viet Nam is one of the first countries in the region to introduce an environmental tax. Established in 2010, the Environment Pollution Tax includes taxes on fossil fuels as well as other environmentally harmful goods such as pesticides and herbicides, HCFCs and plastic bags (OECD, 2018c).

Thailand has made efforts to consider the role of environmental taxes, but to date these have not been implemented on a large scale. The Excise Department proposed a ‘green tax’ approach to base taxes on the ‘polluter pays’ principles in 20112. This would encourage tax rates to be based on environmental costs, for example, on the efficiency of machinery or emissions levels of cars. More recently, there has been discussion on the need for a tax on e-waste to reduce pollution.

Pilot carbon pricing mechanisms must be scaled up

Carbon pricing is Thailand’s primary channel to encourage private investment in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Thailand has engaged in international carbon market mechanisms, through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as well as international voluntary carbon markets. As of January 2020, 154 CDM have developed by private actors in the country (UNEP DTU, 2020). Thailand has also initiated efforts to establish domestic carbon market mechanisms. The Thailand Voluntary Emission Trading Scheme was developed between 2013 and 2016, through the establishment of monitoring systems and implementation of two successive pilot phases. The first pilot phase was initiated in 2014 across the power and petrochemical sectors, involving eleven power plants and seven petrochemical plants (Smits, 2017). The second pilot phase is testing the registry and trading platform (ICAP, 2019). Based on these pilots, a roadmap and legal framework are being developed for consideration by the government.

The Thailand Carbon Offsetting Program was also established to enable organisations and individuals to offset their carbon emissions by purchasing carbon credits from the voluntary market. The progress being made in testing and developing carbon market mechanisms in Thailand is encouraging, although most schemes are still in an early stage of implementation or require participation on a voluntary basis. Further efforts will need to take account of recent guidelines adopted under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Efforts to develop a legal framework and make such schemes obligatory, especially for high emissions sectors, will be key to their scale up.

Policy framework for environmental protection

Thailand has an established regulatory system for environmental impact assessment of projects which has been in place for over four decades. According to the Enhancement and Conservation of the National Environmental Quality Act (NEQA) B.E. 2535 (1992) and the NEQA (No. 2), B.E. 2561 (2018), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) or Environment and Health Impact Assessments (EHIA) are required for an investment depending on its type and size, as determined by law.

EIAs and EHIAs are carried out by consultants registered with the Office of Natural Resources Policy and Planning (ONEP), and are reviewed by an expert committee appointed by the National Environment Board. Once approved, relevant permits are granted.

Despite its long history, the EIA system in Thailand – like in other countries in the region – faces ongoing challenges, especially related to the mitigation and monitoring measures identified in EIAs. In addition, public participation, throughout the EIA process can be further strengthened (Sondergaard et al., 2016). The NEQA B.E. 2561 (2018) responds to this by enhancing monitoring provisions for EIA and EHIA. For example, NEQA B.E. 2561 (2018) increases the role of permitting agencies and provincial MNRE offices in monitoring EIAs mitigation measures and imposes a fine (not exceeding THB 1 million) if EIA monitoring reports are not submitted by project owners.

Thailand has also taken steps to develop a framework for the application of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). SEAs have been conducted sporadically for policies and plans in the country since 2005 and are a useful process to integrate environmental objectives across development programmes in sector-level plans and policies. Limitations of the EIA process in identifying cumulative environmental impacts across multiple projects, or those arising as a result of development planning at a regional level, have increased the awareness of the role of SEA in Thailand. A current gap, however, is that SEAs are not yet a legal requirement though SEA regulations are being drafted by the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC).

Thailand’s international commitments on green growth

Thailand participates in and has ratified most major multilateral environmental agreements (Table 10.2), including the three Rio Conventions: the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2003, UN Convention to Combat Desertification in 2001, and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1994. Thailand ratified the Paris Agreement under the UNFCCC in 2016, and submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution to the convention in 2015.

Investment incentives to promote green industries

Thailand, like neighbouring Malaysia and Viet Nam, provides investment incentives to promote green growth and green investment. Thailand uses incentives to promote new green businesses and projects, as well as to encourage ‘non-green’ projects to take up more efficient technologies and improve environmental performance.

Under the 2015-21 investment promotion strategy, promoting activities that are ‘environmentally-friendly, save energy or use alternative energy’ is one of the objectives of the government (BOI, 2019). Green sectors actively promoted by BOI through the strategy include renewable energy and biodegradable plastics. Incentives include tax-based incentives, such as an exemption on corporate income tax or import duties, and non-tax-based incentives, such as waiving restrictions on foreign ownership and granting permission to bring in skilled foreign workers (Table 10.3). BOI also grants additional tax-based incentives if projects are in certain provinces or industrial areas, as part of its efforts to promote decentralisation and industrial development.

BOI also provides investment incentives to green existing businesses and activities. For example, projects or businesses can get an exemption on import taxes for machinery as well as a three-year corporate income tax holiday if they invest in upgrades to reduce energy consumption, use renewable energy or reduce other environmental impact such as waste or wastewater (BOI, 2019; Bamrungsuntorn, 2019). Another incentive to green business behaviour is a relatively new decision to offer tax deductions in a bid to reduce plastic pollution (Rödl & Partner, 2019). Businesses will be allowed to claim corporate income tax deductions on expenses towards biodegradable plastics between 2019 and 2021.

Investment incentives are also offered to ‘non-green’ activities in targeted sectors, which raises questions about their overall effectiveness in reducing environmental impact. For example, similar – albeit lower – incentives are offered to non-renewable energy related projects, including to clean coal. For plastics, the manufacturing of bio-plastics receive the most favourable incentives, however, similar incentives are also available for non-biodegradable plastics and products3.

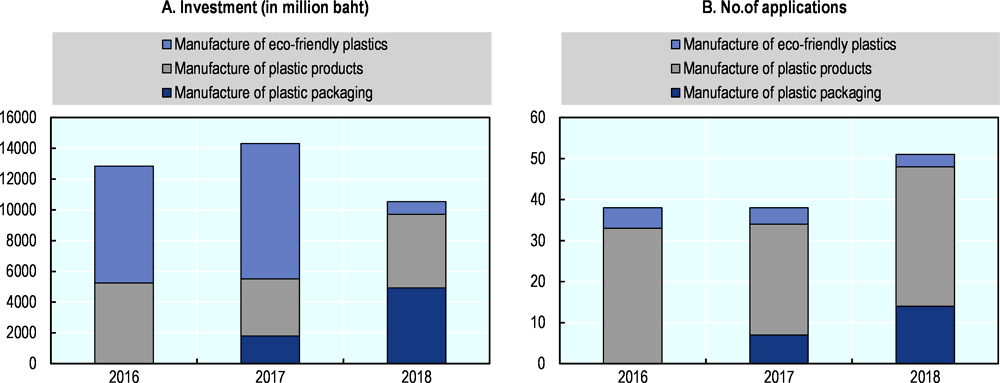

Investment incentives are key for investors in green businesses, similar to investors in other sectors. As discussed in Chapter 5, investment incentives in Thailand have played some role in encouraging foreign businesses to invest or maintain their investment in Thailand. The 2015-21 investment promotion strategy (alongside other policies) has helped to spur investment in both renewable energy and bioplastics (Figure 10.3 and 10.4), with many investments in waste-to-energy4 and renewable energy applying to BOI since the strategy came into place. However, in the same timeframe, investments in ‘non-green’ energy and plastics have also been made. In the latter case, application for investments in non-biodegradable plastics is much higher than those in eco-friendly plastic manufacturing. Rethinking the promotion of non-green sectors alongside green sectors, and a greater alignment of environmental objectives across future investment promotion will be important. A greater use of cost-based incentives for green sectors could also be considered (see Chapter 5).

Promoting investment in clean energy

Thailand’s promotion of renewable energy is a regional success story

Thailand has made major achievements in promoting renewable energy in the last decade (Figure 10.5), and has the highest penetration of renewable energy, from solar, wind and other sources, in Southeast Asia (IEA, 2018). In 2017, biomass and waste, solar and wind made up 8%, 7% and 2% of electricity generating capacity, respectively (BNEF, 2019). In terms of actual generation, renewables made up 8.7% in 2018 (EPPO, 2020). Among other factors, strong signalling from the government, coupled with financing support mechanisms through Feed-in-Tariffs and targeted investment incentives have contributed to Thailand’s success in scaling up renewables.

The signal for investors of Thailand’s ambitions on energy efficiency and renewable energy comes from the Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint 2015-2036 (IRENA, 2017). A result of the government’s efforts to harmonise energy policies, the blueprint ties together five major energy sector plans including the Power Development, the Energy Efficiency Plan, the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), the Oil Plan, and the Gas Plan. The plans include targets on energy efficiency (to reduce energy intensity by 30% by 2036 from 2010 levels) and on renewable energy. In the 2015 AEDP Thailand committed to increasing the share of renewable energy to 30% of energy consumption by 2036, and increasing the share of renewables-based power to 36% in generation capacity and to 20% in generation by 2037. A revised version of the AEDP, circulated in 2019, has increased the ambition of the renewable energy target, aiming to increase renewables to 33% of power generation by 2037 (Sangiem, 2019).

In addition to investment incentives for renewable energy provided by the BOI, Thailand has implemented various subsidy schemes to kick-start the renewable energy market. An ‘adder’ scheme was introduced in 2007 which provided power producers with a supplemental premium over the base cost of electricity they would receive (Norton Rose Fulbright, 2019). In 2014, the scheme was replaced with a Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) scheme, and in 2017-18 the government introduced competitive bidding for projects (IRENA, 2017). The system was run as a reverse auction where project proponents compete based on pricing, with the FiT set as the ceiling price. The FiT covers several sources including community ground- mounted and rooftop solar, waste-to-energy plants, biomass, biogas and wind. While utility scale solar was supported in previous years, with reducing technology prices for solar energy across Asia and the success of previous solar support schemes, the government has now withdrawn tariff support for this (BNEF, 2019). Rooftop and community solar projects, however, are still supported. In addition, the government has introduced a net-metering scheme in 2019 for residential solar applications.

Overall energy planning needs to carefully consider dependence on fossil fuels

Alongside increasing ambition on renewable energy, Thailand’s Power Development Plan (PDP) also includes a small, but substantial share of coal-fired power in the country’s energy mix. The PDP 2015 forecasts an increasing share of coal into the future, since then concerns have been raised about energy security due to the resulting dependence on coal imports, and there has been significant local opposition during the planning stages of the new coal power plants included in the plan. As a result, the recently revised PDP 2018 was published in mid-2019, with lower estimates for coal-fired power. Coal is now forecasted to make up 12% of Thailand’s power generation capacity in 2037.5 While reducing coal dependence is a welcome step, PDP 2018 continues to forecast that most of Thailand’s electricity demand will be met by natural gas. The role of natural gas as a ‘transition fuel’ across emerging Asia is well understood and accepted but, considering the urgency of meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, locking-in two decades of fossil fuel-based power poses a risk.

Financial policies and instruments are key to promoting green investment as they can help increase access to finance, mitigate the risks associated with new green technologies and demonstrate their viability, and reduce the cost of capital associated with green investments to increase their viability (Corfee-Morlot et al., 2012). Policies to promote green finance must include measures to ‘green’ the national financial system by encouraging financial institutions to consider environment, social and governance (ESG) issues and to track and report on climate risks in their portfolios (OECD/UNEP/World Bank, 2018).Enabling the development of green finance instruments – e.g. green bonds – is also important to enable a flow of financing for green projects. In this regard, using public finance – whether from the government or other development actors – is critical to mobilise private investment from foreign and domestic sources (OECD 2018b).

Thailand can build on success in promoting good corporate governance to develop a roadmap for green finance

Thailand has taken several steps to promote responsible business conduct and sustainability in the financial sector, as described in Chapter 9, with all the major regulatory actors – Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET), and several major banks and investors – having related initiatives in place. The focus so far has been on good corporate governance, and the SEC’s Corporate Governance Code 2017 and Investment Governance Code 2017 both encourage responsible business and sustainable investment practices. The uptake of these has been good, with an estimated 99% of listed companies reporting, to some extent, on sustainability as part of annual report disclosure requirements, and around 88 companies referring to SDGs in their reporting (Suwanmongkol, 2019). As a result of these efforts, Thai companies are recognised for sustainability performance, with 20 companies listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index in 2019, and several recognised as industry leaders.6

Building on this success, Thailand has invested and should continue putting effort in building a cohesive framework through its sustainable finance task force and working group bringing together the financial sector, the insurance sector and listed companies, to encourage more targeted performance on green finance and the SDGs. In addition to recognising the importance of ESG in annual reports and voluntary reporting, ESG criteria should be integrated into board terms of reference, into the assessment of clients and transactions, and into portfolio level risk assessment. Currently, these processes are at an early stage in Thai commercial banks (Chen Ted, Stampe and Tan, 2019). A positive step in this area is the SEC’s roadmap on sustainable capital markets, established at the end of 2019 (Box 10.1), and their plans to include information on carbon emissions as part of disclosure for listed companies, which in turn will be supported through capacity building conducted in collaboration with the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Organisation.

Similarly, Thailand must continue to take active steps to promote green bonds in the region. Building on the ASEAN Green Bond Framework, Indonesia and Malaysia have developed their own green finance standards and guidelines, which have resulted in increasing issuances of green bonds and green Islamic finance (i.e. through sukuks). ASEAN green bonds make up only a fraction of global issuance, but have been rising year on year, with Indonesia responsible for 39% of ASEAN issuances (Frandon-Martinez and Filkova, 2019).

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been working to shift the focus of capital markets development beyond corporate governance to broader sustainability. In 2019, the SEC introduced a roadmap for enhancing the sustainability of Thailand’s capital markets in their strategic plan for 2020-2022. The roadmap includes activities targeting the key stakeholders in Thailand’s capital markets, and includes the following priorities:

For issuers, SEC is revising disclosure requirements for listed companies and companies seeking to go public. From 31st December 2021, companies will need to submit a new ‘One report’ combining an Annual Registration Statement and annual report. The ‘One report’ will include information on human rights policy and practices, carbon emissions and provident funds.

For investors, efforts will be made to continue to promote the implementation of the Investment Governance Code (I code) by issuing self-assessment forms and guidelines for asset managers, and by supporting listed companies to use ESG-criteria when choosing fund managers.

For reviewers, international collaboration will be sought to develop capacity of local reviewer entities.

On financial products, guidelines will be issued to encourage green Real Estate Investment Trusts and infrastructure funds to encourage investments in assets, beyond renewable energy, to span more broadly across infrastructure sectors including real estate.

In addition to the areas above, the roadmap includes activities to build the information system on sustainable finance instruments, to increase cooperation among the main finance-related government agencies and the private sector, and to promote international cooperation.

Source: SEC

Although green bond issuances are at an early stage in Thailand, these have grown rapidly in the last two years, with USD 1.25 billion in green, sustainability and social bonds issued in 2019, according to SEC. The government has recently launched its first sustainability bond, also the first of its kind in ASEAN, with a volume of USD 1 billion dedicated to the Mass transit project and COVID-19 relief package. There were also bond issuances of USD 400 million from a state-owned enterprise, of which USD 188 million are green bonds from the Bank for Agriculture Cooperatives and USD 212 million are social bonds from the National Housing Authority. The green bond market has a huge potential to grow as Thailand has a number of potential renewable energy projects (e.g. wind, and solar) in the pipeline that qualify for green bonds.

This momentum has in part been due to the SEC’s efforts to promote green bonds by issuing guidelines on green, social and sustainability bonds in 2018 and 2019 which allow issuers to use any internationally accepted green, social or sustainability bond standards. SEC has also supported ‘bootcamps’ with potential issuers, underwriters and investors. Efforts have also been made to offset the additional monitoring and verification costs associated with issuing green bonds. For example, SEC has introduced waivers for approval and filing fees until mid-2021, and the Thai Bond Market Association has reduced bond registration fees.

Scaling up Thailand’s sustainable finance industry will require clear and transparent policies, especially definitions of what could be considered ‘green’ or not, building on existing international standards that are already being used by issuers and investors. Lessons can be learned from the EU Action Plan on Sustainable Finance and China’s efforts to build a national green finance system, both of which set out clear classification systems on green finance. Considering the nascent stage of Thailand’s green finance industry, a phased approach to identifying and developing such a classification system may help encourage issuances in the short term. For example, an initial step can be to demarcate sub-sectors that would automatically qualify as green and others where more additional criteria could qualify. At an advanced stage, a threshold-based system, like the one proposed in the EU Taxonomy on Sustainable Finance, could be considered at a sub-sector level.

Public finance has helped to spur green investment through blended finance solutions

Public finance plays an important role in spurring green investment in Thailand. Two on-budget funds, the ENCON fund and the ESCO fund, have been important precursors to action on energy conservation and efficiency, and have also helped Thai banks to develop green lending. The Energy Efficiency Revolving Fund, under the ENCON fund, provided credit lines to 11 commercial banks between 2003 and 2012 to enable on-lending to clients to support energy efficiency projects (Grüning et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Initially, the fund was able to leverage funds from banks at a ratio of 1:1, but by 2012 this increased to 1:3 as banks became more familiar with energy efficiency lending.

Similarly, the initial deployment and scale up of solar and wind energy in Thailand was driven by investment and support from the public sector. In addition to investment incentives and tariff support mechanisms, the availability of development finance to support commercial project developers with long term financing helped to kick-start the market. An analysis of the Clean Technology Fund’s role in the Thai solar and wind markets showed that a relatively small volume of concessional climate finance was able to address bottlenecks (BNEF, 2019). An estimated USD 5 billion was invested in solar and USD 3 billion between 2008 and 2017 in Thailand, with the lion’s share of investment coming from project developers and commercial banks. Despite a modest share of overall investment7 (Figure 10.6), financing from CTF and multilateral development banks enabled commercial banks to offer longer tenor loans. This was important because, at the time commercial banks were wary of lending beyond the timespan of the government’s subsidy programme (which ran for 10 years). By blending concessional CTF financing with MDB and commercial banks finance enabled the latter to finance and improve the debt-to-equity ratios of the projects. MDB financing was also able to support newer and smaller developers who did not have an existing track record with commercial banks (BNEF, 2019).

Domestic and international public climate finance supports policy and capacity gaps

Targeted public climate finance is an important source of funding for climate action. Climate finance – whether domestic or international – supports the enabling environment (i.e. policies and institutions), directly finances climate projects and mobilises other sources of financing. Government budgets are the largest source of financing for development more broadly in Thailand, including for climate change. Between 2009 and 2011, approximately 2.7% of the government budget was spent on climate change related projects (UNDP/ODI, 2012). The government has been strengthening management of climate-related budget expenditure, by developing and piloting the use of climate change budgeting analysis (CCBA) (UNDP, 2017).The analysis, once institutionalised, will help the government to better identify spending on climate change and its impact.

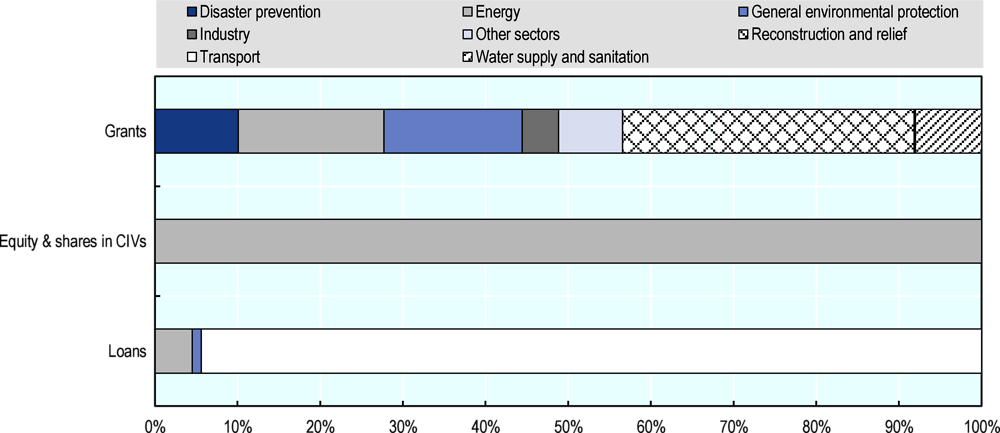

International public climate finance plays a smaller role in Thailand than in other countries in the region, with many donors transitioning to providing technical assistance and policy support after the reclassification of Thailand’s status as an upper-middle income country (UNDP, 2017). According to OECD Development Assistance Committee statistics, between 2012 and 2017, USD 2.3 billion in climate-related development finance was committed towards projects in Thailand. Most of this financing (USD 1.9 billion) was in the form of loans from the Japanese International Cooperation Agency towards the expansion of Bangkok’s metro rail system. Within the same period, approximately USD 217 million in grants were committed towards technical assistance and support for post-disaster relief and rehabilitation (Figure 10.7). Some examples of this include Germany’s support towards climate policy development and implementation, through the German International Climate Initiative, and support from Australia to develop Thailand’s national greenhouse gas inventory.

The volume of climate-related development finance that Thailand will be able to access is likely to remain limited, although the use of these funds can be maximised to support specific policy reforms and institutional capacity building. These can also help to make the case for government spending on green investment, both directly and through specialised vehicles to promote greater private financing for green growth.

References

Bamrungsuntorn, W (2019), Thailand’s Incentives for Renewable Energy Investment 2019, http://warutb.com/2019/05/22/thailands-incentives-for-renewable-energy-projects/.

BNEF (2019), The Clean Technology Fund and Concessional Finance: Lessons Learned and Strategies Moving Forward, https://data.bloomberglp.com/professional/sites/24/BNEF_The-Clean-Technology-Fund-and-Concessional-Finance-2019-Report.pdf.

BOI (2019), A Guide to the Board of Investment, Board of Investment, Bangkok, www.boi.go.th.

Chen Ted, K., J. Stampe and N. Tan (2019), Sustainable Banking in ASEAN: Update 2019, Gland, https://mobil.wwf.de/fileadmin/fm-wwf/Publikationen-PDF/WWF-Sustainable-Finance-Report-Update-2019.pdf.

Corfee-Morlot, J., V. Marchal, C. Kauffmann, C. Kennedy, F. Stewart, C. Kaminker and G. Ang (2012), “Towards a Green Investment Policy Framework: The Case of Low-Carbon, Climate-Resilient Infrastructure.” OECD Environment Working Papers, 48, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k8zth7s6s6d-en.

Eckstein, D., V. Künzel, L. Schäfer and M. Winges (2019), Globla Climate Risk Index 2020: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events?, Germanwatch e.V, Bonn, www.germanwatch.org.

EPPO (2020), Thailand Energy Statistics (database), Bangkok, http://www.eppo.go.th/index.php/en/en-energystatistics/.

Frandon-Martinez, C. and M. Filkova (2019), ASEAN Green Finance: State of the Market 2018, Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Grüning, C., C. Menzel, T. Panofen and L. S. Shuford (2012), Case Study: The Thai Energy Efficiency Revolving Fund, Frankfurt.

ICAP (2019), Emissions Trading Systems Detailed Information: Thailand, International Carbon Action Partnership, Berlin.

IEA (2018), Thailand Renewable Grid Integration Assessment, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://webstore.iea.org/partner-country-series-thailand-renewable-grid-integration-assessment.

IEA (2019), Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2019, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264285576-en.

IRENA (2017), Renewable Energy Outlook: Thailand, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-092401-4.50007-4.

IRENA (2019), Renewable Energy Statistics 2019 (database), International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

McKinsey, and Ocean Conservancy (2015), Stemming the Tide: Land-Base Strategies for a Plastic-Free Ocean, McKinsey, and Ocean Conservancy.

Norton Rose Fulbright (2019), Renewable Energy Snapshot: Thailand, Norton Rose Fulbright, https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/2f5545da/asia-renewables-snapshot-thailand.

OECD (2011), Towards Green Growth, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264111318-en.

OECD (2015a), Green Growth in Bangkok, Thailand, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264237087-en.

OECD (2015b), Policy Framework for Investment, 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en.

OECD (2015c), Towards Green Growth?: Tracking Progress, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264234437-en.

OECD (2017a), "Mobilising financing for the transition", in Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273528-9-en.

OECD (2017b), Green Growth Indicators 2017, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268586-en.

OECD (2018a), Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand (Volume 1): Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293311-en.

OECD (2018b), Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-en.

OECD (2018c), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Viet Nam 2018, OECD Investment Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264282957-en.

OECD/The World Bank/UN Environment (2018), Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308114-en.

Office of Natural Resource and Environmental Policy and Planning (2017), Second Biennial Update Report of Thailand, Office of Natural Resource and Environmental Policy and Planning, Bangkok.

Oxford Economics (2017), Global Infrastructure Outlook, Global Infrastructure Hub, https://outlook.gihub.org/.

Padrem, S. (2019), “Thailand Country Report”, in Energy Outlook and Energy Saving Potential in East Asia 2019, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

Pollution Control Department (2019), Thailand State of Pollution 2018, Pollution Control Department, Bangkok.

Rödl & Partner (2019), For the Sake of Tomorrow: Thailand´s Combat against Littering, Rödl & Partner, https://www.roedl.com/insights/plastic-waste-cit-tax-incentive-thailand.

Sangiem, T. (2019), “Energy Ministry Increases Renewable Energy Ratio”, National News Bureau of Thailand, July 4, 2019, https://thainews.prd.go.th/en/news/detail/TCATG190704144632219.

Smits, M. (2017), “The New (Fragmented) Geography of Carbon Market Mechanisms: Governance Challenges from Thailand and Vietnam”, Global Environmental Politics, https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP.

Sondergaard, L. M., X. Luo, T. Jithitikulchai, C. Poggi, D. Lathapipat, S. Kuriakose, M. E. Sanchez Martin (2016), Thailand - Systematic Country Diagnostic : Getting Back on Track - Reviving Growth and Securing Prosperity for All, World Bank, Washington D.C. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/855161479736248522/Thailand-Systematic-country-diagnostic-getting-back-on-track-reviving-growth-and-securing-prosperity-for-all.

Suwanmongkol, R. (2019), Thailand’s Capital Market: Our Journey to Sustainability, Presentation at Responsible Business and Human Rights Forum, 11 June 2019.

Titiwetaya, Y. (2018), The Coal Situation in Thailand and Strategic Environmental Assessment, Heinrich Boll Stiftung: Southeast Asia, https://th.boell.org/en/2018/05/11/coal-situation-thailand-and-strategic-environmental-assessment.

UNDP/ODI (2012), Thailand Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review, UNDP/ODI, Bangkok.

UNDP (2017), Development Finance Assessment Snapshot Thailand, UNDP, Bangkok.

Wang, X., R. Stern, D. Limaye, W. Mostert and Y. Zhang (2013), Unlocking Commercial Financing for Clean Energy in East Asia Energy and Mining, World Bank, Washington D.C., http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/212781468037508882/pdf/Unlocking-commercial-financing-for-clean-energy-in-East-Asia.pdf.

World Bank (2018), Thailand - World Bank Group Country Partnership Framework 2019-22, World Bank, Bangkok.

World Bank (2020), World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal Thailand, World Bank, Bangkok, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/thailand.

Notes

← 1. See https://edition.cnn.com/2019/01/30/health/thailand-air-pollution-intl/index.html.

← 2. http://www.greenfiscalpolicy.org/countries/thailand-country-profile/

← 3. Manufacturing of plastic products for consumer goods and manufacturing of specialty plastic packaging are classified as A2 and A3, with similar conditions as for bioplastics, however manufacturing of plastic products for consumer goods must be located in SEZs to avail of the incentives.

← 4. It should be noted that waste-to-energy plants are exempted from submitting EIAs except in certain cases (e.g. watershed areas, protected and conservation areas, Ramsar sites and high air pollution areas).

← 5. See https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL3N22C2O8

← 6. See analysis by The Nation here https://www.nationthailand.com/business/30376291

← 7. CTF and multilateral development banks (MDBs) provided an estimated at USD 141 million for solar and USD 94 million for wind projects over the same period.