2. Career readiness in Latin America and the Caribbean

Despite a remarkable recent increase in attainment levels by young people in Latin America, they are still struggling in the labour market and young adults are much more likely to be unemployed than those aged 25. PISA data from 10 LAC countries show that teenagers in secondary education are struggling to form clear expectations about their future careers. Their expectations about occupations are highly concentrated in a small number of largely professional jobs and are poorly aligned with actual patterns of labour-market demand. Teenagers in LAC countries are less likely than OECD’s to be offered the chance to explore potential options through important activities that allow students to engage directly with the world of work, such as job fairs, workplace visits or internships. Looking across the data, it is girls and students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds who typically have most to gain from more effective career guidance.

This chapter focuses on how well young people (aged 15-24) living in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) countries are being prepared by their schools for their adult working lives. It does so in the context of continuing concerns over the success of young people in the competition for work, despite their joining the labour market more highly qualified than preceding generations. This chapter considers the non-academic skills that help students prepare for a successful transition into employment in light of patterns of labour-market demand and to develop the experience, social networks and understanding that provide important advantages in the competition for work. It also draws on comparisons with Portugal and Spain, because of historical ties to the region, and averages from OECD countries with available data. The chapter assesses the effectiveness of LAC countries in preparing youth for their working lives, drawing on international analysis of longitudinal datasets which highlight common positive relationships between teenage career-related attitudes and experiences and later labour-market outcomes (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). Through this comparative exercise, patterns emerge with regard to both the strengths and weaknesses of provision in Latin America and the Caribbean, leading to recommendations for more effective practice.

Every three years since 2000, the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has gathered information from representative samples of teenagers aged 15-16 around the world. The 2018 round of PISA surveyed more than 600 000 students from 79 countries and economies, including 10 from LAC: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Uruguay (OECD, n.d.[2]). Students completed a series of academic assessments in reading, mathematics and science and responded to the Student Questionnaire which includes questions on their social background and educational and occupational expectations. A smaller number of countries opted into two further questionnaires providing information of relevance to students’ readiness for labour-market entry, the Educational Career Questionnaire and the Financial Literacy Questionnaire (Table 2.1 shows which LAC countries were covered by which questionnaires).

In addition, this chapter draws heavily on findings from the OECD Career Readiness project (OECD, n.d.[3]). This study examined longitudinal datasets in 10 countries (Australia, Canada, the People’s Republic of China, Denmark, Germany, Korea, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States and Uruguay) to identify common predictors of better adult employment outcomes linked to teenage engagement in career-related activities, experiences and attitudes. As discussed below, many of the predictors identified allow for the comparative assessment of teenage career readiness using relevant PISA data.

Educational attainment and labour-market preparedness

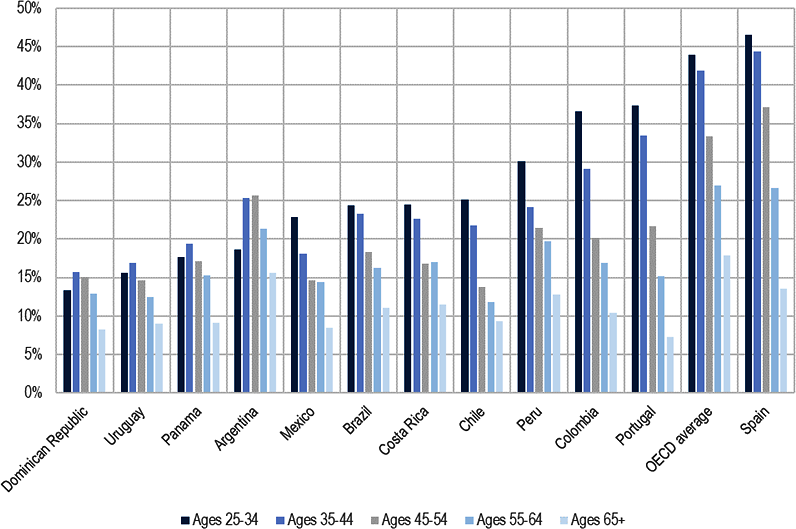

Around the world, the last two generations have seen a remarkable increase in the levels of education achieved by young people. They are proceeding to, and completing, upper secondary education and then moving on to tertiary education in record numbers. LAC countries are, in general, no exception to this phenomenon. In Mexico, for example, the proportion of young people completing upper secondary education increased from 39% in 2005 to 66% in 2019; in Chile it rose from 81% to 90% over a similar period. In Colombia, such upper secondary success rates rose from 68% in 2013 to 77% in 2019 (OECD, 2021[4]). Although the trend at tertiary level is not as pronounced as in Portugal and Spain, younger adults in LAC countries are generally more likely to have attained tertiary qualifications than their older peers (Figure 2.1).

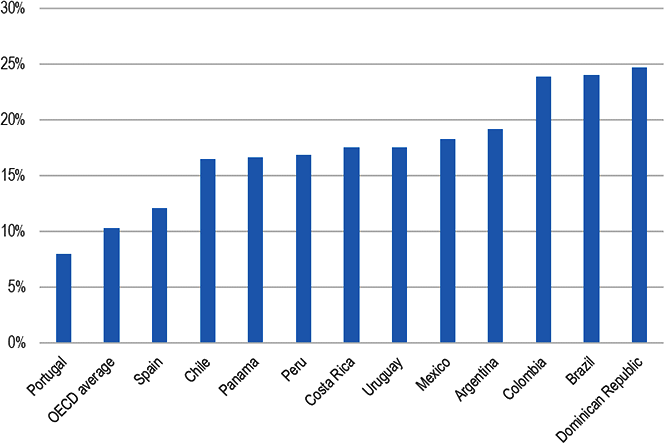

However, despite apparently growing levels of human capital, as captured by academic qualifications, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, up to one in three 15-24 year-olds were not in employment, education or training (NEET) in LAC countries. Such NEET rates are substantially higher than in Portugal and Spain (Figure 2.2).

Comparing youth and adult unemployment

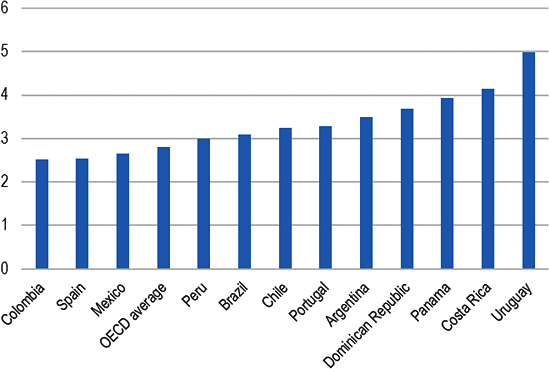

While high NEET and youth unemployment rates raise concerns in themselves, they provide a blunt tool for measuring the relative attractiveness of young people to employers: joblessness may be high for all workers. An alternative way of assessing the relative challenges facing young people in the competition for work is to look at the ratio of youth to adult unemployment. This ratio describes how many times higher unemployment rates are for young people (aged under 25) in than for older workers and therefore indicates the extent of employer preference for older workers, not just the state of the labour market overall. While young people always face additional challenges when they enter the labour market (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]), the extent to which they can overcome them varies considerably between countries. Across Latin America and the Caribbean, the International Labour Organization (ILO) calculated the ratio of youth to adult unemployment in 2019 at around 3, ranging from 2.5 times higher in Colombia to 5 times higher in Uruguay (Figure 2.3). In some global regions, the ratio is much higher, reaching averages of above six in Southeast Asia and the Pacific and in Southern Asia. In Europe however, youth unemployment is commonly twice the level of adult unemployment (ILO, 2020[8]).

The ratio reflects several factors within an economy. For example, where it is more difficult for employers to dismiss workers or where employers have poor understanding or confidence in educational qualifications, they can be expected to be more conservative in their hiring practices, placing greater emphasis on prior experience (Breen, 2005[9]). Moreover, where national minimum wages are set at levels that align poorly with the anticipated productivity of new workers, employers may decide against the risk of hiring young people (Brown, Gilroy and Kohen, 1983[10]). However, the ratio also provides insight into the effectiveness of education systems in preparing young people for the competition for work. In Switzerland and Germany for example, countries with strong vocational education systems, the ratio is very low (around 1.5). In these countries, mass participation apprenticeship programmes give young people the opportunity to address factors which may reduce their attractiveness to potential recruiters: they can gain work-based experience, develop connections with potential employers and build a first-hand understanding of work culture and recruitment practices (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]; Pastore, 2018[11]).

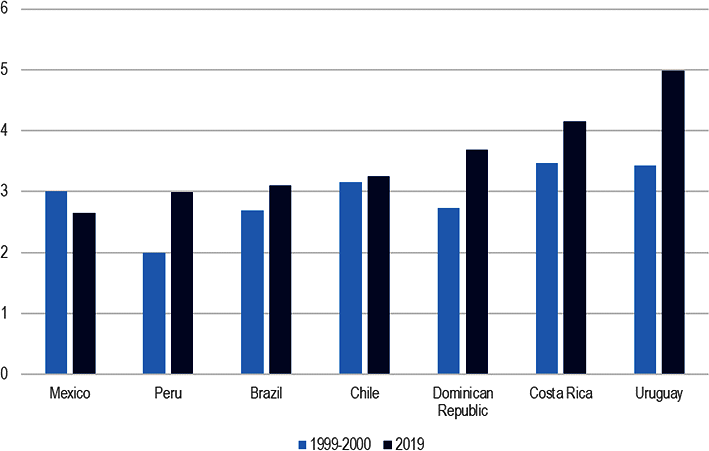

While it might be expected that the ratio of youth to adult unemployment would have narrowed over the last 20 years as youth have entered the labour market more highly qualified, this is generally not the case in LAC countries (Figure 2.4). Of the countries considered in this chapter, for which data are available, only Mexico has seen the ratio fall since the turn of the century. The youth labour-market participation rate in LAC countries has been declining modestly but persistently over the last generation, falling from 54% in 2000 to 49% in 2020 (ILO, 2020[8]). NEET rates have also moved slightly upwards over the last 20 years, from 20.1% in 2000 to 21.7% in 2020. Young people in LAC countries are also more likely than their older peers to work informally (ILO, 2020[8]).

Understanding why LAC youth struggle in the competition for work

There are a number of possible explanations why greater educational success is not translating into better employment. These results may raise questions about the quality of educational provision and the true extent to which qualifications and additional years of education are capturing increases in knowledge and skills (OECD, 2017[13]). Relatedly, the continuing challenge of youth employment may relate to mismatches between the supply of narrowly developed skills and the demand for them. In their responses to global surveys, employers from Latin American countries are more likely than their counterparts in other regions to state that a workforce with the wrong skills (either too highly educated, not educated enough or lacking the right kinds of skills) is a major constraint on their operations (OECD, 2021[14]). Informality in the labour market, which is marked in many LAC countries, may also make it more difficult for young people to find attractive employment that reflects their qualifications and skills after leaving education (ILO, 2015[15]; OECD, 2017[13]).

The rest of this chapter, however, explores the question from a different perspective and asks whether educational institutions in LAC countries are preparing young people effectively for the non-academic dimensions of the competition for employment. It explores data relevant to the engagement of young people in the labour market while they are still in school, as well as what schools have been doing to prepare young people for their working lives through career guidance programmes.

Occupational uncertainty

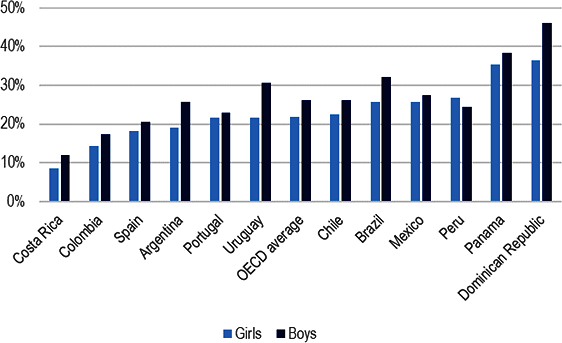

The OECD PISA 2018 survey asks students to name the kind of job they expect to have when they are about 30 years old. Students who can name an expected field of employment can be designated as “career certain” whilst their peers who cannot name an occupation, or whose thinking is seen as too vague to allow for identification, are classified as “uncertain” by researchers (Covacevich et al., 2021[16]). The results for LAC countries show considerable variation in the extent of such career uncertainty (Figure 2.5). In the Dominican Republic, 46% of boys and 36% of girls were unable to name an occupational expectation. At the other end of the spectrum, only one in ten young people in Costa Rica can be labelled as uncertain. Across most LAC countries, as across the OECD, boys are on average more likely to be uncertain than girls. Considered alongside data presented below on teenage career concentration, many young people across the LAC region can be seen to be thinking about their careers in ways that raise concerns; they are struggling to visualise their future in work even as they are facing key decisions about their secondary education and beyond.

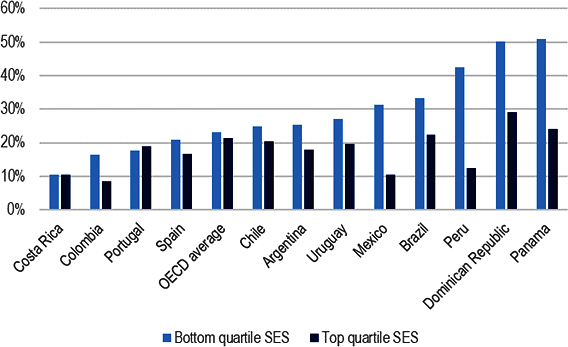

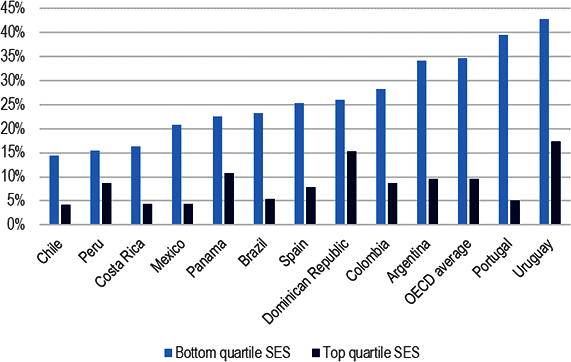

Career uncertainty is particularly high in a number of countries among youth from the most disadvantaged quartile of socio-economic backgrounds (Figure 2.6). In PISA, a student’s socio-economic status is estimated by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS), a composite measure that combines into a single score the financial, social, cultural and human capital resources available to that student. In practice, it is derived from several variables related to students’ family background that are then grouped into three components: parents’ education, parents’ occupations and an index summarising a number of household possessions that can be taken as proxies for material wealth or cultural capital, such as possession of a car, the existence of a quiet room to work in, access to the Internet, the number of books and other educational resources available in the home (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). In Peru and Mexico, the most disadvantaged quartile of students – based on this index – are more than three times more likely than their more advantaged peers to be uncertain about their career plans. In Panama and the Dominican Republic, half of the most socially disadvantaged students are unable to identify a potential future career.

Occupational ambitions

Where students could name an expected occupation, their answers were coded by analysts against the 2008 version of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) (ILO, 2012[18]). ISCO groups jobs into 10 major groups and then further categorises them into increasingly precise levels (2, 3 and 4 digit level). Importantly, the question in the PISA survey asks students about their occupational expectations, rather than aspirations: the job they expect, rather than hope, to secure. Consequently, the responses can be expected to include some degree of realism in the assessments of the young participants.

The occupational expectations in LAC countries among both girls and boys are typically more concentrated than the OECD average, as well as those in Portugal and Spain. Figure 2.7 shows the percentage of girls and boys who say that they expect to work in one of the 10 most popular occupational choices among their fellow girls or fellow boys. For both girls and boys, the occupational expectations in LAC countries are typically more concentrated than OECD averages and in Portugal and Spain. Expectations were most concentrated in the Dominican Republic where, among students who expressed an expectation, 74% of girls and 72% of boys anticipated working in one of just ten jobs by 30. Annex Table 2.A.1 lists the most popular occupational expectations for boys and girls in 10 LAC countries.

With the exception of Mexico, girls’ occupational expectations are more highly concentrated than boys’ expectations. On average across the 10 LAC countries for which data are available, 64% of girls naming an occupational expectation anticipate working in one of the top ten jobs. For boys, the figure is slightly lower at 62%. This gender difference aligns with findings in most OECD countries and may reflect the composition of labour markets where girls’ choices are constrained due to patterns of labour-market segmentation and discrimination. However, one striking finding from the data is that girls in LAC countries are more likely to name jobs that are typically dominated by men. In the LAC countries, girls expect to be working as accountants, sportspeople, members of the armed forces, chefs, pilots and especially engineers (Annex Table 2.A.1). None of these professions are found among the top ten occupations identified by girls on average across the OECD countries (Mann et al., 2020[19]).

The importance of occupational expectations

The PISA question on the occupational expectations of young people provides insight into the effectiveness of labour-market signalling in LAC countries (Muller, 2005[20]). An early sense of vocational identity can be positive for young people, helping them to achieve their occupational plans (Schoon and Parsons, 2002[21]). However, collectively the data on the occupational expectations of youth in LAC countries raise concerns in relation to longitudinal analyses and in comparison with actual patterns of employer demand.

The consequences of highly concentrated occupational expectations

As discussed above, young people in LAC anticipate working in very narrow parts of the labour market. For example, in Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica, more than one-fifth of girls expect to be a doctor by the age of 30; in the Dominican Republic the share is one-quarter, with a further 20% expecting to work either as a teacher or engineer (Annex Table 2.A.1). A small number of recent studies have looked at the potential long-term consequences of high degrees of concentration in teenage occupational expectations. They explore the hypothesis that students naming more original career expectations may have devoted great consideration to their plans for the future, resisting the influence of peer thinking and potentially preparing for job roles where there they will encounter lower levels of competition (Percy and Schoon, 2021[22]). OECD analysis of longitudinal data from Australia, Canada, Denmark and Switzerland explored whether there were labour-market penalties (typically at the age of 25) linked to those teenagers with more popular career expectations (among the 10 most popular expectations by gender) compared to those with more original expectations (all other stated expectations). In Switzerland, no relationship was found. In Australia and Denmark there were positive relationships between more original teenage career expectations and higher earnings in adulthood for students in some circumstances (Covacevich et al., 2021[16]). Forthcoming longitudinal analysis from the United Kingdom suggests that girls can expect to benefit from more original teenage job plans (Percy and Schoon, 2021[22]). In Canada, however, a negative significant relationship has been found between greater originality in career plans and employment outcomes (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). Consequently, while data are currently limited and inconclusive, they do point towards there being some penalties for at least some students linked to what can be described as a lack of originality in occupational expectations.

Mismatched occupational expectations and labour-market composition

International studies highlight the frequency of gaps between teenage career aspirations and actual patterns of labour-market demand (OECD, 2017[23]). Overwhelmingly, youth around the world expect to be working in managerial or professional occupations by the age of 30 (ISCO major groups 1 and 2). At an individual level, the international literature has shown that such teenage ambition is related to better employment outcomes in young adulthood – more ambitious teenagers can typically expect better employment outcomes than their less ambitious peers leaving education with similar levels of academic achievement (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). However, more broadly, highly concentrated and mismatched patterns of career ambition raise concerns over the efficacy of labour-market signalling.

There are considerable discrepancies between the occupational expectations among LAC 15-year-olds, as recorded in PISA 2018, and ILO data on the distribution of the actual labour force. In LAC, the trend for concentrated career ambitions is particularly strong and is focused mainly on ISCO major group 2 (professionals). This group includes sub-groups covering science and teaching professionals; health professionals; teaching professionals; business and administration professionals; information and communications technology professionals; and legal, cultural and social professionals (ILO, 2012[18]). Students in the LAC countries taking part in PISA 2018 had a greater interest in these careers than on average in OECD countries (excluding LAC members). In non-LAC OECD countries, on average, 47% of boys and 65% of girls anticipate a career within ISCO major group 2 by the age of 30. In the 10 LAC countries for which data are available from PISA 2018, the average was 65% of boys and 78% of girls. Yet, within LAC labour markets, relatively few people work in such occupations. On average across these 10 countries, 7.7% of men and 13.7% of women worked in the professional occupations listed in ISCO major group 2 in 2019, compared with 18.8% of men and 26.2% of women across OECD countries (ILO, n.d.[24]).

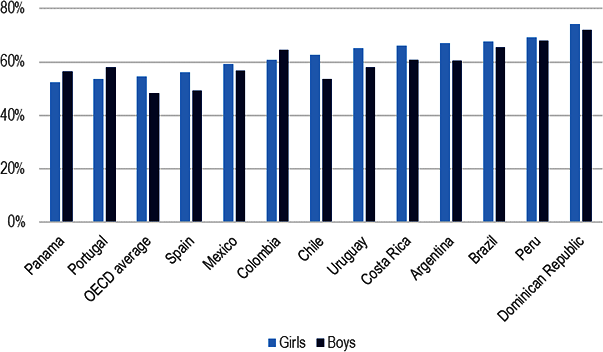

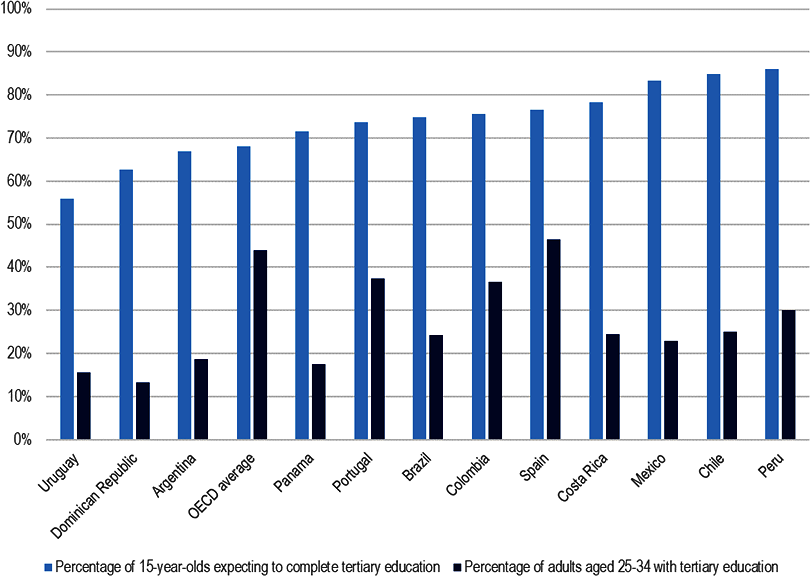

Unsurprisingly, large proportions of LAC youth also anticipate completing tertiary education. Across the 10 LAC countries for which PISA 2018 data are available, 74% of students expect to complete tertiary education on average. Expectations are particularly high among girls: in Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Peru and Mexico, between 80% and 90% of girls say that they will achieve a university-level education. Most students are unlikely to achieve such educational ambitions, however. On the eve of the pandemic, fewer than one-quarter (23.5%) of 25-34 year-olds in these 10 countries had obtained a tertiary level qualification (Figure 2.8).

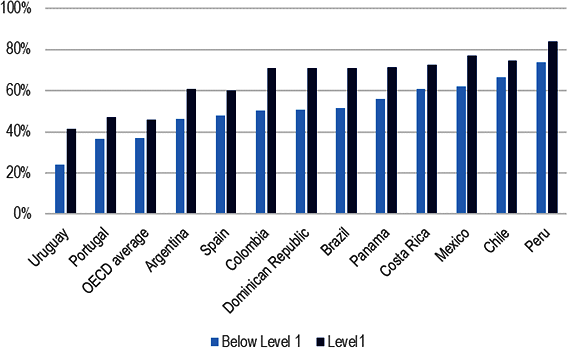

In contrast with OECD countries, levels of educational ambition do not vary that greatly by socio-economic background. Among LAC students with higher scores in the PISA academic assessments – suggesting they have the ability to succeed in tertiary education – a high proportion of students from all backgrounds plan to attain that level. While this is a positive phenomenon, the data for less well-performing students raise further concerns about the level of educational ambition in LAC countries. Many of the lowest achievers also aspire to tertiary education, suggesting confusion about the academic ability required to benefit from higher education. As Figure 2.9 shows, high proportions of youth in LAC countries with very weak literacy skills (below Level 2) expect to pursue tertiary education. In the PISA assessment, students who do not attain Level 2 proficiency in reading often have difficulty when confronted with written material that is unfamiliar, or that is of moderate length and complexity. They usually need to be prompted with cues or instructions before they can engage with the text. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals have identified Level 2 as the “minimum level of proficiency” that all children should acquire by the end of secondary education (OECD, 2019[25]).

Many young people from LAC countries also anticipate working in jobs that commonly require university attendance, but do not plan to pursue tertiary education (Figure 2.10). Such students can be characterised as having misaligned ambitions and longitudinal data point towards such students performing more poorly in the early labour market than would be expected given their personal, social and academic characteristics (Covacevich et al., 2021[16]; Covacevich et al., 2021[1]; Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). Such misalignment is especially common among students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds. These students face especially high risks of poorer outcomes than might otherwise be expected from their academic attainment.

In contrast, students in LAC countries are less interested in working in skilled or semi-skilled occupations. There are three major ISCO groups related to skilled and semi-skilled employment, which in many countries is commonly entered through programmes of vocational education and training (VET):

In LAC countries, as well as in Portugal and Spain, the proportions of students expressing an interest in these careers are low – 1% to 7% (Figure 2.11). In the 10 countries for which data are available, on average 6% of boys anticipate working in an ISCO 6, 7 or 8 occupation, compared to 26% of boys in Germany, 25% in Switzerland, 10% in Portugal, 8% in Spain and an OECD average (all countries) of 17%. On average, in the LAC countries which are the focus of this chapter, 39% of adult men work in such professions (ILO, n.d.[24]). The levels of interest in such professions among girls are especially low. Only in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Panama is it possible to detect any interest from girls in skilled and semi-skilled employment, and even here fewer than 2% of girls expect to work in such jobs.

Employment penalties of labour-market mismatches

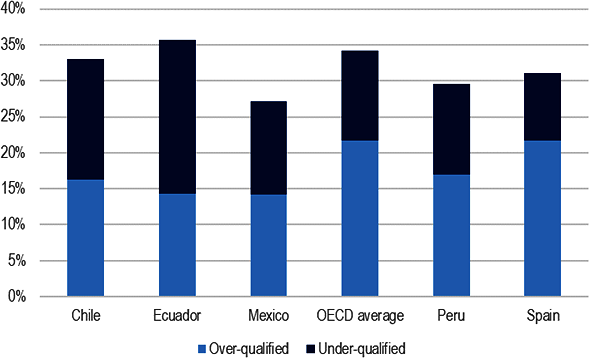

One potential consequence of teenage occupational expectations bearing little relation to the actual patterns of labour-market demand, is that their future employment could align poorly with their educational qualifications. OECD data from the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) illustrate the long-term penalties associated with mismatches between the educational profile of young adults and the jobs they do (OECD, 2016[26]). PIAAC provides data on two types of mismatch: by level of qualification and by field of study. Looking at the labour-market experiences of 16-34 year-olds, mismatch by level of qualification is common in the four Latin American countries taking part in PIAAC, as it is across the OECD (Figure 2.12).

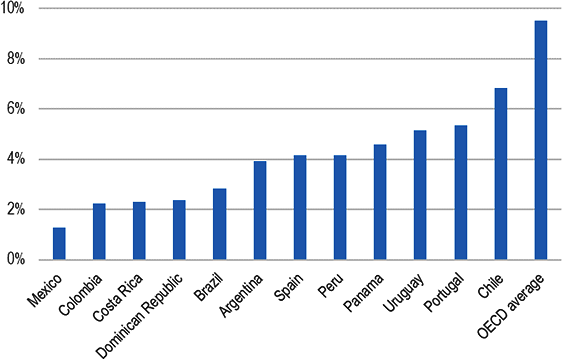

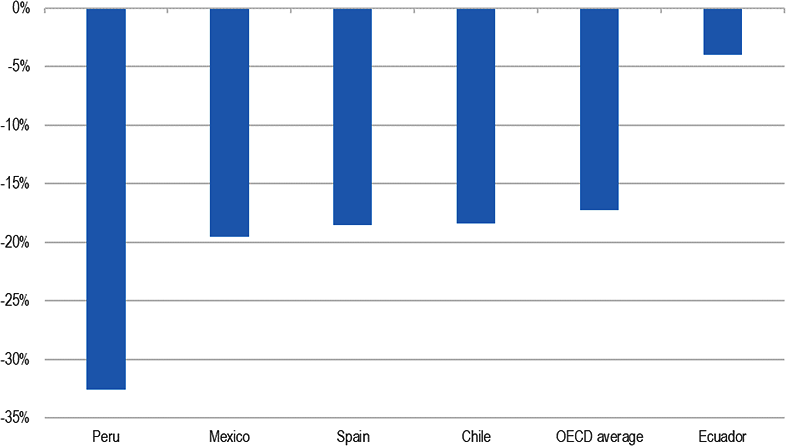

PIAAC data show, moreover, that young adults (aged 16-34) who are overqualified for their jobs can expect to be penalised in the labour market (Figure 2.13). They can expect to earn less than peers who are working in comparable jobs, but whose qualifications are well matched. The scale of the penalty rises from 4% in Ecuador to 33% in Peru. The penalties are weaker for mismatches in the field of study. As is the case across the OECD, there is no strong trend in earning variations in those LAC countries for which data are available.

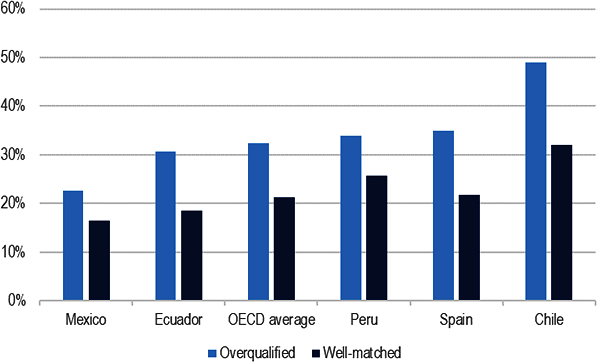

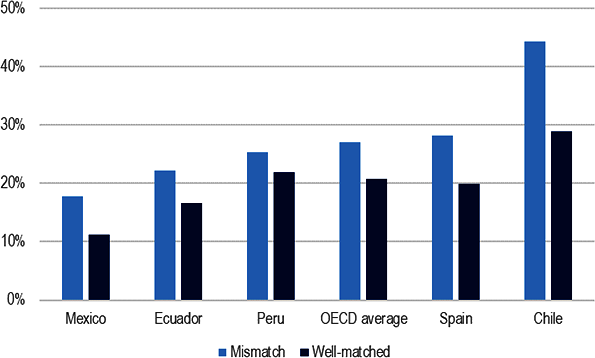

In terms of job satisfaction, there is a clear pattern in both LAC countries and across the OECD. Young adults who are overqualified for their occupation are much less likely to agree that they are satisfied or very satisfied with their job (Figure 2.14). Similarly, those who work in an occupation connected with their field of study are more consistently likely to agree that they are satisfied with their jobs (Figure 2.15).

The PISA data reflect the occupational expectations of young people aged between 15 and 16. In many educational systems, young people of this age will shortly have the opportunity to specialise in their studies (with consequences for their tertiary education choices) or to enter the labour market. Ensuring that 15-year-olds understand the educational requirements of their chosen or expected careers will be a key factor in their labour-market transition. Upper secondary education in Mexico, as in other LAC countries, has a high dropout rate driven by several factors, including insufficient access to career information and guidance (OECD, 2017[13]).

Provision of career guidance in LAC secondary schools

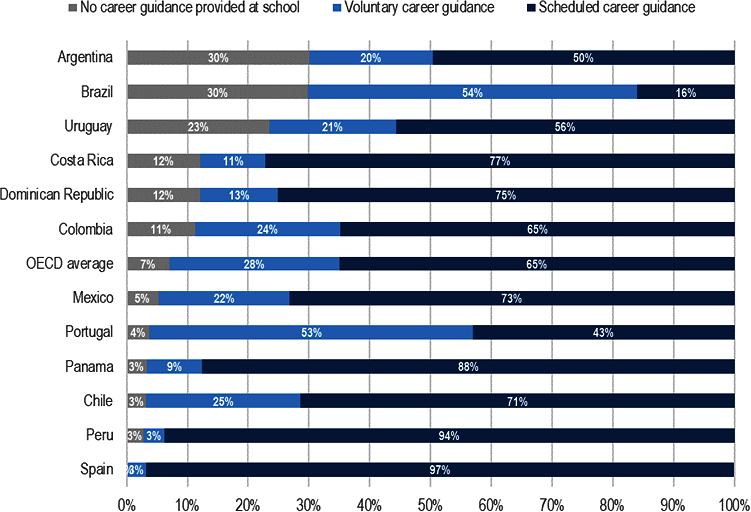

The PISA 2018 study asks the principals of schools whose students are taking part in the survey about the delivery of career guidance. Principals are asked whether guidance is made available to students within the school and, if so, whether it has to be sought out voluntarily by students or is formally scheduled into their time. Across OECD countries, on average, only 7% of schools do not provide career guidance, while it is compulsory for students to take part in scheduled career guidance in 65% of schools (Figure 2.16).

As Figure 2.16 shows, there is considerable variation among the LAC countries taking part in PISA 2018. In Argentina and Brazil, nearly one-third of schools do not offer career guidance. Where guidance is available, it is often not scheduled into the curriculum, and such optional guidance raises concerns. Students’ attitudes to careers are heavily shaped by often unspoken assumptions and expectations linked to social backgrounds (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]; Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[28]). Effective careers guidance systems challenge such thinking by requiring student engagement (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). Consequently, optional access to guidance can be expected to be less effective in challenging inequalities than compulsory provision. Furthermore, even where guidance is available within school, the quality of provision may be insufficient (OECD, 2017[13]).

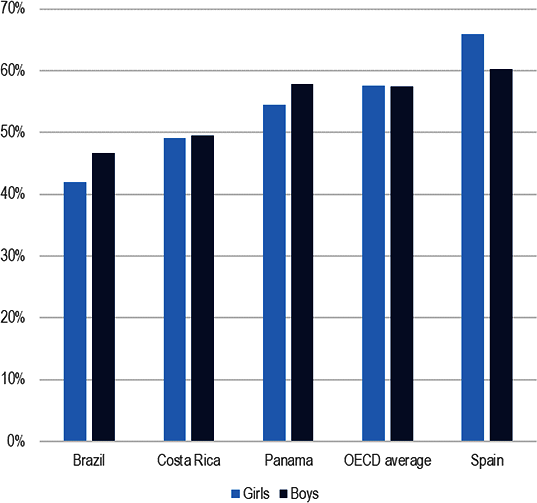

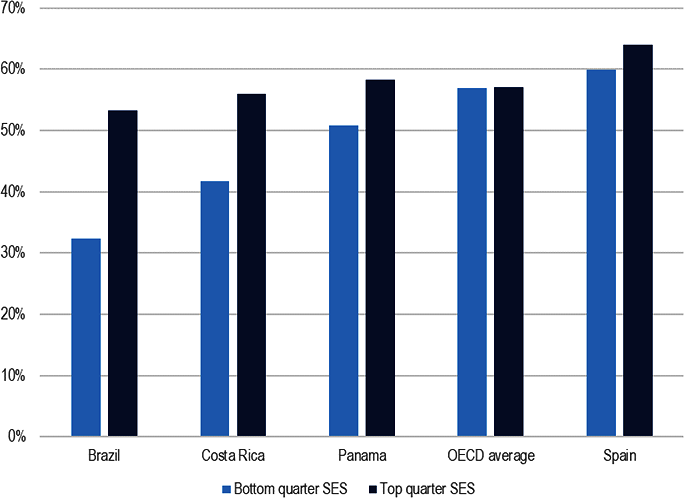

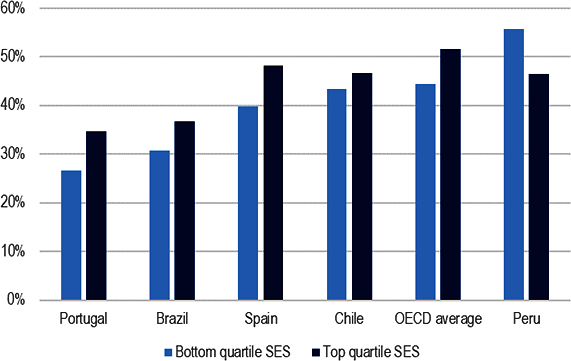

Among the countries for which data are available, students in LAC countries are less likely than their peers in Spain and OECD countries to have spoken with a guidance counsellor by the age of 15. In the three LAC countries for which PISA 2018 data are available, only Panama has comparable levels of engagement with career advisers to the OECD average of 57%. In Brazil and Costa Rica, fewer than 50% of students report that they had spoken with a career adviser either in or outside school. In all three countries, boys are marginally more likely than girls to report having spoken with an adviser (Figure 2.17). Differences in access to such provision related to socio-economic status (SES) are even more pronounced (Figure 2.18). Students from the lowest SES quartile in Brazil are 66% less likely than their most advantaged peers to have spoken to an adviser, compared to 14% in Panama and 33% in Costa Rica 33%. Notably, students across the OECD who do report speaking with a guidance counsellor are more than twice as likely to speak to one within their school than outside it, whereas students in Brazil, Costa Rica and Panama are only slightly more likely to speak with an internal adviser than an external one.

Exploring potential futures in work

Influential theories of career development (Holland, 1959[29]; Bandura, 1986[30]; Super, 1975[31]) consistently focus on the need for young people to learn more about themselves, the world of work and potential pathways into it if they are to optimise their transitions through education and ultimately into employment. Such exploration builds a sense of confidence in identifying and progressing towards ambitions that are stretching but also reflect their personal interests and abilities. Analysis of OECD PISA data show that teenage career thinking is heavily influenced by gender, socio-economic background and migrant status (Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[28]). Through reflective exercises, students can question their assumptions and expectations. As they learn more about themselves, they can become better placed to broaden their interests and form realistic and stable self-conceptions that will underpin their progression towards more successful and emotionally satisfying engagement with the labour market.

Engaging with employers and people in work within school guidance

During these processes of labour-market exploration, it is now widely agreed that career guidance provision can only be effective if it is enriched by the engagement of employers and people in work (Box 2.1) (Cedefop; ETF; EC, 2021[32]; Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[28]).

Employers and people in work often collaborate with schools to enrich their career guidance. They do so through such activities as work placements (or internships), career talks, jobs fairs, workplace visits, job shadowing, mentoring, interview practice, CV workshops and enterprise competitions. Studies of such engagements highlight how they present students with opportunities to gain information and experiences of value which can not easily be replicated in schools without such engagement (Mann, Stanley and Archer, 2014[33]; Mann, Huddleston and Kashefpakdel, 2019[34]). The value of the engagement stems from both the actual and perceived authenticity of the interactions. Interactions can enhance students’ human capital (providing work-related experience of value to later employers), social capital (access to people who can help in transitions through providing advice, recommendations and potentially jobs) and cultural capital (enabling a confident and clear vision for progression) (Stanley and Mann, 2014[35]; Mann, Rehill and Kashefpakdel, 2018[36]; Jones, Mann and Morris, 2016[37]; OECD, 2021[38]).

A 2018 review of the international literature on employer engagement in guidance activities suggests that students can expect the diversity, intensity and their satisfaction with the activities to be enhanced (Mann, Rehill and Kashefpakdel, 2018[36]).

Diversity: where students undertake a range of different activities, they can be expected to have the opportunity to secure a wider range of potential benefits.

Intensity: where students repeat activities (with different content), notably career talks, they are more likely to gain new and useful information.

Satisfaction: where students (as teenagers) agree that guidance activities were useful to them, it is more likely that they consciously gained something of value to them.

Recent OECD analysis of longitudinal datasets in multiple countries identifies a range of development activities that can be linked with better employment outcomes (for example, wage premiums, typically of 5-10%) that can either only be delivered with the support of employers and people in work (career talks with guest speakers/job fairs, workplace visits, work placements, volunteering in the community) or are considerably enhanced through their participation (recruitment skills activities, occupationally-focused short programmes) (OECD, 2022[39]). Models for enabling employers and people in work to engage with schools include the development of focused centres (such as the New Brunswick Centres for Excellence in Canada which enable connections between schools and high priority economic areas such as energy and health) and online resources (such as Inspiring the Future in the United Kingdom and New Zealand) which use online technology to connect school staff and employee volunteers directly (Government of New Brunswick, 2022[40]; Education and Employers, n.d.[41]).

One common way employers and people in work support the career guidance of young people in secondary education is by talking to them directly about their jobs, careers and workplaces. Career talks with guest speakers and job fairs are common activities designed to help students explore potential career options. Studies in the United Kingdom have explored the relationship between teenage participation in guidance activities that engage employers and employment outcomes in adulthood. For example, Kashefpakdel and Percy (2017[42]) use longitudinal data to highlight substantial wage premiums at age 26 linked to teenage involvement in school-managed career talks at ages 14 to 16. Studies by Mann and colleagues (Mann and Percy, 2014[43]; Percy and Mann, 2014[44]; Mann et al., 2017[45]) using cross-sectional data from surveys of 19-24 year-olds found significant relationships between more positive adult employment outcomes and the volume of (recalled) teenage engagement with employers through guidance activities.

Recent OECD analysis has identified positive associations between teenage participation in job fairs and career talks and better employment outcomes in Australia, Canada and Uruguay (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). In addition, longitudinal analysis of UK data (Kashefpakdel and Percy, 2017[42]) identified positive outcomes linked to multiple (five or more) career talks undertaken at age 14-15. In Uruguay, students who had participated in career talks whilst at school by the age of 15 were less likely to be NEET 10 years later after having controlled for a range of background variables.

Career talks and job fairs aim to provide students with new and useful information relevant to their career visualisation and planning. This can be seen as a form of social capital, described by US sociologist Mark Granovetter in his influential study on the “strength of weak ties” as access to non-redundant, trusted information (Granovetter, 1973[46]; Mann, Kashefpakdel and Percy, 2019[47]; Raffo and Reeves, 2000[48]). Through personal interactions, young people can engage with people who they are inclined to find trustworthy and who have access to knowledge and experiences of value. As each interaction is likely to provide access to information about different types of jobs and pathways into them, multiple interactions are more likely to generate access to new and useful information (Kashefpakdel and Percy, 2017[42]). Surveys of experienced guidance practitioners highlight the importance of schools providing students with the opportunity to interact with people in work on numerous occasions, with their value enhanced where students perceive interactions to be relevant and feel authentic (Rehill, Kashefpakdel and Mann, 2017[49]).

Colegio Legamar in Madrid, Spain is a private, non-denominational educational institution that covers early childhood, primary, lower and upper secondary education (ages 1-18). Since 2017, the school has organised and hosted monthly career talks for students aged 15-18, highlighting occupations related to academic subjects studied within the Spanish Baccalaureat, an upper secondary academic qualification.

Each session lasts for an hour and a half, and features three volunteer professionals. Each volunteer is given 15 minutes to speak about their occupation. After all the volunteers have spoken, they engage in a 45-minute Q&A discussion with the students.

The volunteers are selected mostly (and preferably) from the school’s alumni network of former students, but may also be drawn from other networks, including relatives of the students. Where possible, the volunteers defy gender stereotypes in their occupational choice. This includes female engineers, architects and police officers, as well as male early childhood teachers, nurses, pharmacists and tour guides. In addition, an effort is made to ensure that volunteers attended a range of different higher education and vocational institutions. This allows students to be exposed to and compare between the offerings of different institutions, including their operations, the type of scholarships they offer, and the agreements they have with companies.

OECD (n.d.[50]), Career Talks at Colegio Legamar, www.oecd.org/education/career-readiness/examples-of-practice/collapsecontents/spain-career-talks.pdf.

Students receive career information from employers and people in work through three common mechanisms: career talks (see Box 2.2 for an example), job fairs and career carousels. Of these, the third format – where guest speakers speak to small groups of students in turn – is likely to be most effective in helping students gain new and useful information. In a career talk with a guest speaker, students may adopt a passive role and disengage if they do not immediately see the relevance of the profession. Job fairs allow students to connect with a wide range of people from different work backgrounds but if they are not well managed, students may fail to engage due to a lack of confidence, peer pressure and pre-existing assumptions. In a career carousel, guest speakers might speak with 5-6 small groups of students in the course of an hour. In such circumstances, it is harder for students to disengage and the structure ensures that they will have multiple opportunities to engage with people from different occupational backgrounds (Rehill, Kashefpakdel and Mann, 2017[49]).

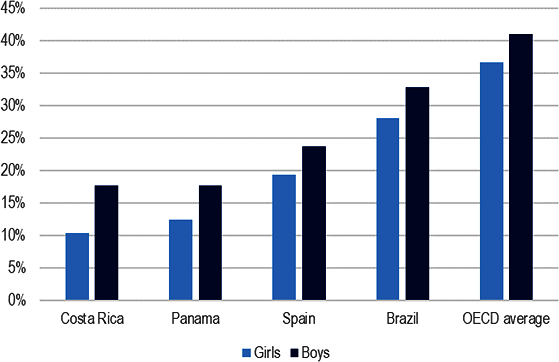

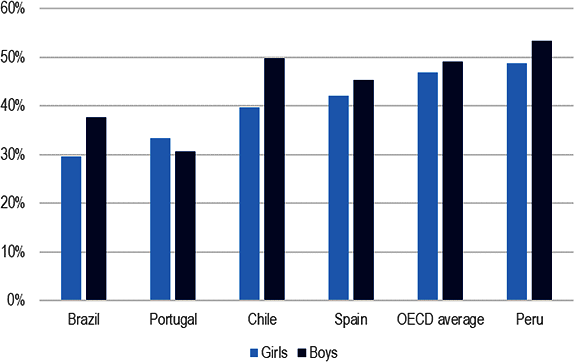

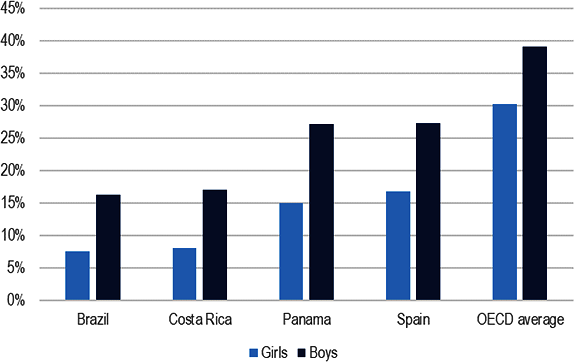

In PISA 2018, students from 32 countries were asked whether they had taken part in a job fair by age 15. Across participating OECD countries, around two in five students reported that they had (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). In the LAC countries with data available, participation rates were lower. Boys were more likely than girls to report participating in such an event. Participation rates in Costa Rica (where 10% of girls and 18% of boys reported attending a job fair) and in Panama (12% of girls and 18% of boys) are among the lowest recorded in the PISA survey (Figure 2.19).

Further analysis of the data shows a particularly strong relationship between socio-economic status and the likelihood of participation in a job fair among LAC youth. In Brazil, 43% of students from the highest SES quartile have attended a job fair by the age of 15, more than twice the share as among their peers from the lowest quartile (19%). In Costa Rica, more advantaged students are 86% more likely to have participated in a job fair. In Panama, the figure is 41%.

Workplace visits and job shadowing

A further means of helping students gain new and useful information about their career plans is through programmes of workplace visits and/or job shadowing. In the former, groups of students visit workplaces to gain a general overview of an enterprise and its economic sector, to become familiar with workplace cultures and to receive career information, often from multiple working professionals. Workplace visits typically last a few hours but may take a whole day. They can include group exercises, workshops, networking events, presentations, Q&A sessions and site tours (Buzzeo and Cifci, 2017[51]; OECD, 2022[52]). Job shadowing can be seen as a more focused and more intimate form of workplace visit. Typically involving a single student or a very small group, job shadowing enables young people to observe one or more professionals at work. It allows for a more focused insight into work roles that are commonly more closely linked to career aspirations than is the case with workplace visits (OECD, 2022[52]). Job shadowing can also include programmes where parents bring their children with them to work for a day or half day (Box 2.3).

A common way of enabling students, often aged around 14, to visit workplaces and to observe people in work is on annual days where parents are encouraged to bring their children with them to work. Participation in such days is especially widespread in Canada and the United States. Students typically visit a parent’s workplace for a half day or full day to become more familiar with the jobs that their parents (and often their colleagues) do. The day is also used as an opportunity for children (particularly those whose parents are unable to facilitate a workplace visit) to engage in job shadowing in other workplaces.

Challenging gender stereotypes through job shadowing

In order to challenge barriers to more equal participation in the labour market by men and women, Germany has pioneered Girls’ Days and Boys’ Days. Every year, tens of thousands of students aged 10-18 spend a day in workplaces exploring professions where their gender is under-represented. The initiative is an opportunity for girls and boys to critically investigate the reality of what it would be to work in such an occupation. Such days are now held in many other countries, including Spain.

For both programmes, the beneficial effects are maximised through preparation and reflection in class.

Sources: OECD (n.d.[53]), Canada: Take Our Kids to Work Day, www.oecd.org/education/career-readiness/examples-of-practice/collapsecontents/canada-take-our-kids-to-work-day.pdf; Girls’ Day (n.d.[54]), Future prospects for girls, www.girls-day.de/fakten-zum-girls-day/das-ist-der-girls-day/ein-zukunftstag-fuer-maedchen/english; Boys’ Day (n.d.[55]), Why offering a future day for boys?, www.boys-day.de/footer/english-information. See also OECD (2022[52]).

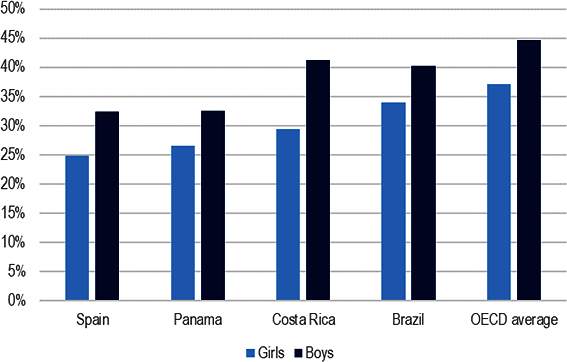

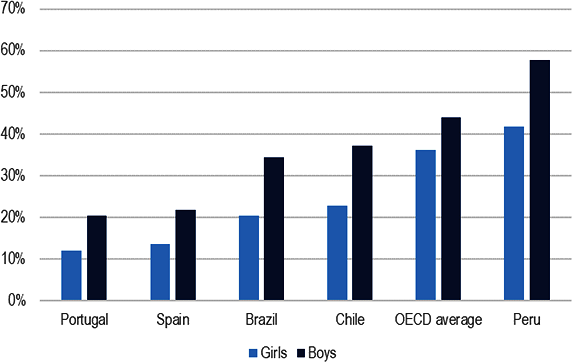

Historically, research literature on the long-term benefits of job shadowing and workplace visits has been very limited (OECD, 2022[52]). OECD analysis of longitudinal data found positive relations between such activities and better employment outcomes in Australia, Canada, Korea and the United States (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). Across the OECD countries for which data are available, two in five students report having participated in a workplace visit or job shadowing by the age of 15 on average. In the three LAC countries for which data are available, participation levels were lower, but higher than in Spain. In general across all OECD countries, boys are more likely than girls to have participated in such careers activity and this pattern is also replicated in the three LAC countries (Figure 2.20).

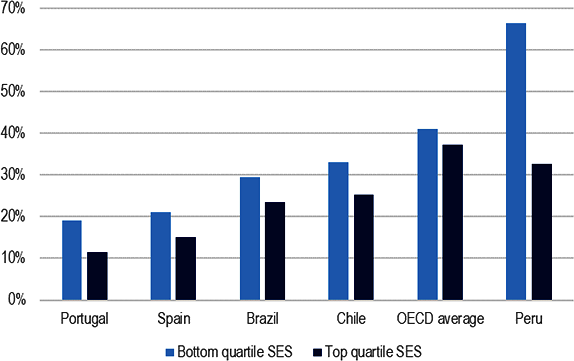

As with job fairs, one striking divide in the PISA data on such participation relates to the socio-economic status of students. In OECD countries, the gaps between students in the highest and lowest SES quartiles are modest, but in the three LAC countries for which data are available, the differences are more substantial. In Brazil, high SES students are 80% more likely to report visiting a workplace than their low SES peers (47% compared to 26%). In Panama, more advantaged students are 47% more likely to have participated in the activity and in Costa Rica the figure is 25%.

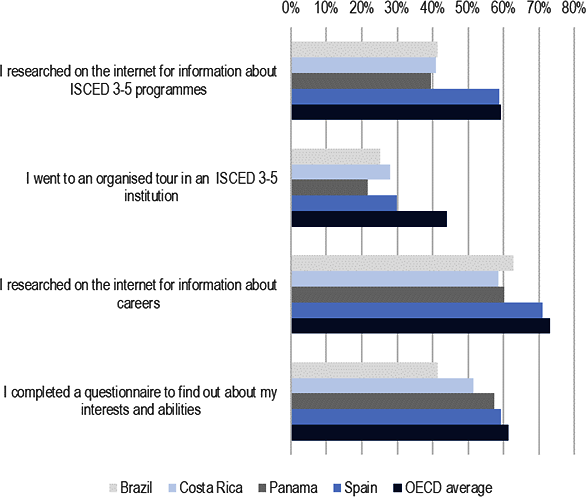

Schools also enable students to explore their potential career interests through various guidance activities. PISA 2018 includes questions on four common student activities: researching careers and continuing programmes of education on the Internet, taking part in an organised tour of a tertiary institution, and completing a questionnaire on career interests. As Figure 2.21 shows, young people in the three LAC countries for which data are available are less likely than their peers across the OECD or in Spain to have participated in any of these activities by the age of 15. Gender variations in participation in all four of these activities are modest but there are strong variations by SES in all three LAC countries. In Brazil, for example, students from the lowest SES quartile are 97% less likely to have completed a career questionnaire, 79% less likely to have visited a post-secondary educational institution, 67% less likely to have researched careers on the Internet and 111% less likely to have researched post-secondary educational programmes on the Internet than their more advantaged peers.

Experiencing potential futures in work

Schools have important roles to play in helping young people to explore the labour market and visualise potential futures in work (OECD, 2017[23]; Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). More effective career preparation also involves encouraging and enabling students to gain first-hand experiences of the working world while they are still in secondary education. European data show that young adults who experienced work either through internships or other forms of work-based learning managed by their schools, or through independent part-time working, are routinely more likely to be in employment than peers (Musset, 2019[57]). These experiences might be managed through educational institutions (internships or work placements), through private endeavour (part-time jobs organised through private endeavours), or volunteering in the community managed via either schools or private endeavours. Such workplace engagement serves three primary purposes linked to the human, social and cultural capital accumulation of young people (Jones et al., 2019[58]; Musset, 2019[57]).

First, students can gain work-related experience and skills (human capital) of potentially significant value to future employers seeking reassurance that a young person will be a good fit for an entry-level position. By undertaking workplace tasks, teenagers can develop a range of potential skills, including technical skills (such as the use of workplace equipment) and soft or employability skills that relate to how a task is effectively completed. Teenagers are frequently presented with the opportunity to interact with other employees and customers, undertaking positions of responsibility which provide valuable learning opportunities. For example, analysis of PISA 2018 data shows that students who had worked part-time, volunteered or taken part in internships are significantly more likely to agree that they can adapt well to unfamiliar situations (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]).

Second, their workplace engagements enable students to meet people who may be of help in their transition into full-time work (social capital). Employers are well placed to provide offers of full-time employment (after completion of secondary education), offer advice on continuing pathways in education and training, and supply references and recommendations to young people for jobs elsewhere.

Finally, their first-hand experiences introduce young people to distinctive work cultures (cultural capital). They can gain insight into subtle codes of personal presentation and behaviour that relate to different occupational areas and learn what potential recruiters most value in terms of qualifications and experience that they can further develop while they are still in education. They have opportunity to learn what researchers drawing on the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu describe as the “rules of the game” as they consider different professions (OECD, 2021[38]; Côté, 2002[59]; Archer et al., 2012[60]; Raffo and Reeves, 2000[48]).

Part-time employment

Of the three means through which teenagers can secure first-hand work experiences, the strongest international evidence for better employment outcomes is in relation to part-time work. The great majority of the many longitudinal studies that have explored the relationship between teenage part-time work and better later employment outcomes have found evidence of a positive relationship (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]; Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). However, it should be noted that such studies relate to a small number of OECD countries.

PISA 2018 includes data on part-time teenage work from three LAC countries: Brazil, Chile and Peru (Figure 2.22 and Figure 2.23). In Brazil and Chile, around one-quarter of 15-year-olds reported working in a relatively formal job, compared to an OECD average of 40%. In Peru, around half of students said they worked. In all three countries, higher levels of participation in part-time working are strongly associated with gender, socio-economic status and geographic location: boys, and students from lower SES backgrounds or rural areas are more likely to combine employment with their full-time studies (OECD, 2021[61]). This pattern of teenage working may suggest limits to the efficacy of part-time working in Latin America, where informal labour markets and high levels of inequality might be expected to increase the need for students to contribute financially to their household from a young age. Longitudinal analysis from OECD countries suggests that working excessive part-time hours (typically more than 10 hours a week) can be detrimental to the academic achievement of youth, counteracting the benefits gained from increased workplace experience (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]). PISA includes no details on the duration of hours worked. In such circumstances, school-mediated opportunities to engage directly in the working world through volunteering and internships might be expected to offer more effective means of ensuring female participation and improving the quality of the experience, particularly if opportunities relate more closely to areas of personal career interest.

Volunteering

An alternative means of giving students the opportunity to gain first-hand experience of the working world is through volunteering in the community. When students undertake such roles, they often undertake tasks employees would normally be paid for and work alongside paid professionals. Volunteering is widely – but not always (Sikora and Green, 2020[62]) – seen as a comparable mechanism for skills development to part-time work (National Youth Agency, 2008[63]; Ockenden and Stuart, 2014[64]; Walsh and Black, 2015[65]; Sikora and Green, 2020[62]). A series of studies over the last decade have identified statistically significant positive labour-market outcomes linked to teenage volunteering (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). In the United States, positive associations have been found between teenage volunteering and higher than anticipated earnings in adulthood, years of education, good mental health and life satisfaction (Chan, Ou and Reynolds, 2014[66]; Ballard, Hoyt and Pachucki, 2018[67]; Kim and Morgül, 2017[68]). Using longitudinal data from Australia, Sikora and Green (2020[62]) found a significant relationship between formal teenage volunteering outside of study time and adult occupational status, calculating the impact of teenage volunteering on enhanced occupational status to be one-quarter of the size of that of completing higher education (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]).

One important study from the United States asked students whether they chose to volunteer or were required to do so by their school. The study provides a deeper control mechanism linked to psychological disposition. It might be expected that students who are more extraverted and confident would be more likely to choose to volunteer, particularly in the community. Such psychological characteristics might help explain better labour-market outcomes in young adulthood. However, Kim and Morgül (2017[68]) found no difference in the character of later employment benefits linked to whether students chose, or were required, to volunteer. This suggests that it is the nature of the experience that can be expected to help students prepare for their ultimate transition into the labour market.

According to PISA 2018, teenage volunteering levels in Chile and Peru are comparable to the OECD average but they are substantially lower in Brazil. Girls seem to participate less frequently than boys (Figure 2.24). In Chile, they are 25% less likely to have volunteered by the age of 15. Young people from higher SES backgrounds are also more likely to have volunteered than students from the most socially disadvantaged quartile (Figure 2.25).

Internships

A third means through which students can gain first-hand experiences of the world of work is through work placements or internships, which involve going into a workplace and undertaking tasks that employees are normally paid to undertake. These commonly last 1-2 weeks for students in general education but longer for students in vocational programmes (Musset, 2019[57]). While data from longitudinal studies are currently too limited to confirm whether work placements predict better adult employment outcomes internationally, a number of studies suggest that they can be valuable to students if delivered well (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]; Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]).

In the three Latin American countries for which data are available, participation rates in internships are below the average for participating OECD countries (Figure 2.26). Typically, just one in five 15-year-olds in these countries have spent much time in an internship. The lack of participation among girls is particularly acute. In Brazil and Costa Rica, only 8% of girls have had such first-hand experiences of work through their school by the age of 15. In Panama, the proportion is 15%. Perhaps surprisingly, given the PISA data discussed above, participation rates vary relatively little by students’ SES background, however.

An important advantage of school-managed work placements is the opportunity for a short internship to be undertaken within an occupational area of interest. Unfortunately, this is often not the case even in countries where high proportions of young people undertake work placements (Fullarton, 1999[69]). Careful planning and reflection are required to ensure that young people gain value from their internships, as long-term benefits cannot be taken for granted (Jones et al., 2019[58]). Moreover, risks of social reproduction, entrenching inequity, arise when students are asked to find their own placement (Le Gallais and Hatcher, 2014[70]) particularly where they are expected to make use of family-based social networks. Schools can mitigate risks by ensuring guidance counsellors work closely with students to identify work placements following periods of extended career exploration (Le Gallais and Hatcher, 2014[70]). Students need an informed understanding of their career interests to secure the maximum benefit, so effective systems need to provide young people with plentiful opportunities to explore their own interests before undertaking an internship (Mann, Denis and Percy, 2020[7]; Turner, 2020[71]). In New Zealand, for example, some schools adopt a model of growing and deepening engagement in the world of work (OECD, n.d.[72]). At ages 10 to 14, students engage in activities such as career talks and workplace visits to become familiar with the working world prior to periods of more intense exploration, including job shadowing. These lead in turn to first-hand experiences of work through internships and direct interactions with employers, primarily around ages 16-18. In both New Zealand and some Canadian provinces, students can earn credits from their work placements that contribute towards their final graduation (Musset, 2019[57]).

The development of personal agency through career guidance

As PISA 2018 reveals, in Latin America and the Caribbean as elsewhere in the world, young people do not lack aspiration (Mann et al., 2020[19]). However, young people vary considerably in how much access they have to resources which will allow them to make informed and confident decisions, gain a realistic appreciation of the efforts required to achieve their aspirations, and secure the experience that will enable them to make progress with their ambitions (Archer, 2014[73]; Blustein, 2019[74]; Bok, 2010[75]; Gardiner and Goedhuys, 2020[76]; Smith, 2011[77]).

Indian sociologist Arjun Appadurai considers aspiration as a personalised cultural resource developed within a specific social context (Appadurai, 2004[78]; Hart, 2016[79]). Developed within studies of social mobility in low-income countries, where it is particularly influential (Bernard et al., 2014[80]; Chiapa, 2012[81]; Gardiner and Goedhuys, 2020[76]), this approach conceives career aspirations to be a consequence, rather than a cause, of poverty and inequality (Dalton, Ghosal and Mani, 2016[82]). The concept draws on social capital theory which highlights the importance of social relationships in enabling access to economic opportunities (Granovetter, 1995[83]) and bears a close relation to the idea of critical consciousness defined by Blustein (2019[74]) as the capacity to reflect on, and the commitment to address, the causes of social inequality. As Heberle (2020[84]) notes in a recent review of US academic literature, positive relationships have been found in a series of cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative studies between critical beliefs and actions related to social inequality and injustice, and better than expected career-related attitudes and outcomes, including earnings at age 26 (Diemer, 2008[85]). In essence, the better young people understand the reality of the labour market and how it operates, the better placed they are to reach better outcomes. With the support of their schools, families and others, they can develop and deploy a stronger sense of personal agency, guiding a smoother transition into the career they want.

Several aspects of teenage students’ attitudes towards their future careers are associated with lower unemployment, higher wages and greater job satisfaction in international longitudinal data. These include greater career certainty, career ambition (expecting to work in an ISCO group 1 or 2 job), career alignment (expecting to attain the typical level of education needed to start their expected occupation) and instrumental motivation (confidence that secondary schooling will help them in their search for desirable employment) (Covacevich et al., 2021[16]; Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). Having clear and ambitious visions for the future, informed by understanding of how education can help achieve those goals, speaks to students’ personal agency. Analysis of data from PISA 2018, controlling for gender, socio-economic status and reading scores, found statistically significant relationships across all OECD countries with data available between the more beneficial forms of career thinking and engagement with a range of guidance activities (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). A similar picture is found in the LAC countries for which data are available, albeit to a lesser extent. This suggests that guidance provision in LAC countries tends to be less effective than is the case across OECD countries.

As discussed above, PISA 2018 data suggest that many young people in LAC countries, particularly girls and those from more disadvantaged social backgrounds, could benefit from greater access to career-related exploration and experiences to enhance their career thinking. This chapter highlights three primary challenges for LAC countries: engaging students with employers and people in work; enhancing guidance programmes to enable a culture of continued critical reflection; and prioritising the needs of the most disadvantaged, including girls and students from low SES backgrounds.

Young people entering the labour market need to draw on their first-hand experiences of work, social networks and cultural familiarity to create the human, social and cultural capital that can help them make an effective transition to the world of work. In education systems, such preparation is delivered through career guidance programmes. Unfortunately, in many LAC countries, schools do not provide career guidance or it is not a compulsory part of the curriculum. Students are less likely to participate in those areas of career guidance most strongly linked with better outcomes than their peers across the OECD, including in Portugal and Spain. Only a small minority have attended job fairs and career talks, or workplace visits, including job shadowing. This is particularly important because LAC students also typically experience lower levels of part-time working, volunteering or school-managed work placements than is the norm across OECD countries.

Employer engagement plays an essential role in ensuring the efficacy of career guidance. By connecting directly with people in work, young people have the opportunity to secure new and trustworthy information about the labour market, develop useful social contacts and gain valuable insights into distinctive work cultures. Looking across the available data for LAC countries, the priority should be to deliver coherent career guidance programmes that are strongly enriched by first-hand contact with employers and people in work. Effective guidance programmes enable young people to visualise and plan their futures, creating a sense of personal agency that allows them to reap the greatest benefit from increasing years of education and training. A culture of critical reflection, through discussion and use of resources such as psychometric testing and reflection on labour-market encounters, will help students develop career aspirations that are both ambitious and pragmatic.

There are many international examples of approaches to bring elements of work-related learning into the classroom in order to create a culture of critical career investigation. In some French schools, for example, students are tasked with researching careers related to a topic of study in their science projects, investigating working conditions, salaries and typical entry requirements (OECD, n.d.[86]). In Australia, programmes encourage students to research professions based on their own interests and then relate them to subjects of study (OECD, n.d.[87]). In the United States, some schools use psychometric testing to develop students’ understanding of their personal preferences. They are then helped to see how different jobs value different psychological dispositions and how they relate to academic provision (OECD, n.d.[88]). In Australia, Canada and the United States, many schools offer occupationally-focused short programmes that help students to explore and prepare for potential careers in vocational areas such as healthcare, manufacturing and information technology (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]). Offered alongside general education, such programmes are often available to students aged 16-18 over 1-2 days a week and are typically rich in work-related and work-based learning. Longitudinal analysis shows that participation can commonly be related to better labour-market outcomes (Covacevich et al., 2021[1]).

There are strong patterns in the LAC data showing how gender and SES shape students’ career preparation. For example, girls are consistently less likely than boys to have had the opportunity to gain work experience while still in school. Students from less advantaged backgrounds frequently demonstrate career thinking associated with poorer employment outcomes than would be expected given educational performance. They are also less likely to participate in the most effective career guidance activities. This is especially concerning for students who are not expected to pursue tertiary education but go straight into the labour market after leaving school. Consequently, patterns of systemic disadvantage linked to gender and SES should be priorities for educational reform programmes to address (OECD, 2021[89]; Covacevich et al., 2021[1]).

The Gatsby Benchmarks were developed by the Gatsby Foundation in 2013 and were introduced as a requirement of English schools serving young people aged 12-18 in 2018 (Department for Education, 2021[90]; Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2018[91]). They describe eight core attributes of career guidance based on the international research which was then available and have since attracted considerable interest as a model for structuring career guidance at secondary schools.

1. A stable careers programme. Every school and college should have an embedded programme of career education and guidance that is known and understood by students, parents, teachers, governors/trustees, employers and other agencies.

2. Learning from career and labour market information. Every student, and their parents (where appropriate), should have access to good quality information about future study options and labour-market opportunities. They will need the support of an informed adviser to make the best use of available information.

3. Addressing the needs of each pupil. Young people have different career guidance needs at different stages. Opportunities for advice and support need to be tailored to the needs of each pupil. A school’s or college’s careers programme should embed equality and diversity considerations throughout.

4. Linking curriculum learning to careers. All subject staff should link the curriculum with careers, even on courses that are not specifically occupation-led. For example, science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subject staff should highlight the relevance of STEM subjects for a wide range of career paths. Study programmes should also reflect the importance of numeracy and literacy as a key expectation from employers.

5. Encounters with employers and employees. Every student should have multiple opportunities to learn from employers about work, employment and the skills that are valued in the workplace. This can be through a range of enrichment activities including visiting speakers, mentoring and enterprise schemes, and should include students’ own part-time employment where it exists.

6. Experiences of workplaces. Every student should have first-hand experiences of the workplace through work visits, job shadowing or work placements to help their exploration of career opportunities and expand their networks.

7. Encounters with further and higher education. All students should understand the full range of learning opportunities that are available to them. This includes both technical and academic routes and learning in schools, colleges, universities and in the workplace.

8. Personal guidance. Every student should have opportunities for guidance interviews with a career adviser, who could be internal (a member of school staff) or external, provided they are trained to an appropriate level. These should be available for all students whenever significant study or career choices are being made. They should be expected for all students but should be timed to meet their individual needs.

Education systems in Latin America and the Caribbean would benefit from expanding the provision of career guidance activities that enable all students to explore and experience potential futures in the labour market, enabling and encouraging them to continue to reflect on their future ambitions. Over recent years, countries around the world have enhanced guidance provisions in recognition that growing levels of academic achievement have often failed to systematically improve the competitiveness of young people in the search for attractive employment (Cedefop; ETF; EC, 2021[32]). At an institutional level, schools are finding ways of integrating guidance provision into the wider curriculum (Box 2.4). One influential policy model for articulating what is expected of educational institutions is the Gatsby Benchmarks which set clear expectations of all secondary schools (Box 2.5). Policy makers can also ask questions of schools based on the most recent analysis of international longitudinal research (OECD, 2021[92]). Effective provision regularly asks students about their occupational and educational ambitions, encouraging and enabling them to reflect on their responses, and the related academic requirements, with guidance counsellors. As they leave secondary school, young people should be helped to develop transition plans that will enable them to reach their ambitions.

For governments, the longitudinal data have provided a substantial new rationale for ensuring the provision of high-quality guidance. The evidence is that teenagers who explore, experience and think about their potential future careers commonly experience lower rates of youth unemployment and higher wages in adulthood, addressing the need for a more efficient distribution of skills within an economy. Consequently, career guidance can be seen as a low-cost preventative measure with high confidence in long-term returns on investment.

References

[78] Appadurai, A. (2004), “The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition”, in Rao, V. and M. Walton (eds.), Culture and Public Action, Stanford University Press.

[73] Archer, L. (2014), “Conceptualising aspiration”, in Mann, A., J. Stanley and L. Archer (eds.), Understanding Employer Engagement in Education, Routledge.

[60] Archer, L. et al. (2012), “Science aspirations, capital, and family habitus: How families shape children’s engagement and identification with science”, American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 49/5, pp. 881-908, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23319630.

[67] Ballard, P., L. Hoyt and M. Pachucki (2018), “Impacts of adolescent and young adult civic engagement on health and socioeconomic status in adulthood”, Child Development, Vol. 90/4, pp. 1138-1154, https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12998.

[30] Bandura, A. (1986), Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, Prentice Hall.

[80] Bernard, T. et al. (2014), “The future in mind: Aspirations and forward-looking behaviour in rural Ethiopia”, CSAE Working Paper Series, Centre for the Study of African Economies.

[74] Blustein, D. (2019), The Importance of Work in an Age of Uncertainty: the Eroding Work Experience in America, Oxford University Press.

[75] Bok, J. (2010), “The capacity to aspire to higher education: ‘It’s like making them do a play without a script”, Critical Studies in Education, Vol. 51/2, pp. 163-178, https://doi.org/10.1080/17508481003731042.

[55] Boys’ Day (n.d.), Why offering a future day for boys?, Boys’ Day website, https://www.boys-day.de/footer/english-information.

[9] Breen, R. (2005), “Explaining cross-national variation in youth unemployment: Market and institutional factors”, European Sociological Review, Vol. 21/2, pp. 125-134, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci008.

[10] Brown, C., C. Gilroy and A. Kohen (1983), “Time series evidence of the effect of the minimum wage on youth employment and uemployment”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 18/1, pp. 3-31, https://doi.org/10.3386/w0790.

[51] Buzzeo, J. and M. Cifci (2017), Work Experience, Job Shadowing and Workplace Visits. What Works?, The Careers & Enterprise Company, https://resources.careersandenterprise.co.uk/resources/work-experience-job-shadowing-and-workplace-visits-what-works.

[32] Cedefop; ETF; EC (2021), Investing in Career Guidance: Revised Edition, Inter-Agency Working Group on Career Guidance, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications/2230.

[66] Chan, W., S. Ou and A. Reynolds (2014), “Adolescent civic engagement and adult outcomes: An examination among urban racial minorities”, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Vol. 43, pp. 1829-1843, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0136-5.

[81] Chiapa, C. (2012), “The effect of social programs and exposure to professionals on the educational aspirations of the poor”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 31/5, pp. 778-798, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.05.006.

[59] Côté, J. (2002), “The role of identity capital in the transition to adulthood: The individualization thesis examined”, Journal of Youth Studies, Vol. 5/2, pp. 117-134, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260220134403.

[16] Covacevich, C. et al. (2021), “Thinking about the future: Career readiness insights from national longitudinal surveys and from practice”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 248, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/02a419de-en.

[1] Covacevich, C. et al. (2021), “Indicators of teenage career readiness: An analysis of longitudinal data from eight countries”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 258, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cec854f8-en.

[82] Dalton, P., S. Ghosal and A. Mani (2016), “Poverty and aspirations failure”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 126/590, pp. 165-188, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12210.

[90] Department for Education (2021), Careers Guidance and Access for Education and Training Providers: Statutory Guidance for Schools and Guidance for Further Education Colleges and Sixth Form Colleges, United Kingdom Department for Education, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/careers-guidance-provision-for-young-people-in-schools.

[85] Diemer, M. (2008), “Pathways to occupational attainment among poor youth of color: The role of sociopolitical development”, The Counseling Psychologist, Vol. 37/1, pp. 6-35, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000007309858.

[41] Education and Employers (n.d.), Inspiring the Future website, https://www.inspiringthefuture.org/.

[69] Fullarton, S. (1999), “Work experience and work placements in secondary school education”, LSAY Research Reports, No. 10, Australian Council for Education Research, https://research.acer.edu.au/lsay_research/70/.

[76] Gardiner, D. and M. Goedhuys (2020), “Youth aspirations and the future of work: A review of the literature and evidence”, ILO Working Paper, No. 8, International Labour Organization, https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_755248/lang--en/index.htm.

[91] Gatsby Charitable Foundation (2018), Good Career Guidance, Gatsby Charitable Foundation.

[54] Girls’ Day (n.d.), Girls’ Day - Future prospects for girls, Girls’ Day website, https://www.girls-day.de/fakten-zum-girls-day/das-ist-der-girls-day/ein-zukunftstag-fuer-maedchen/english.

[40] Government of New Brunswick (2022), Centres of Excellence website, https://centresofexcellencenb.ca/.

[83] Granovetter, M. (1995), Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers, University of Chicago Press.

[46] Granovetter, M. (1973), “The strength of weak ties”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78/6, pp. 1360-1380, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392.

[79] Hart, C. (2016), “How do aspirations matter?”, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, Vol. 17/3, pp. 324-341, https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2016.1199540.

[84] Heberle, A., L. Rapa and F. Farago (2020), “Critical consciousness in children and adolescents: A systematic review, critical assessment, and recommendations for future research”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 146/6, pp. 525-551, https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000230.

[29] Holland, J. (1959), “A theory of vocational choice”, Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 6/1, pp. 35-45, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040767.

[6] ILO (2022), Share of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) by sex (%) - Annual, ILOSTAT database, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data (accessed on 2 June 2022).

[12] ILO (2022), Unemployment rate by sex and age (%) - Annual, ILOSTAT database, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

[5] ILO (2022), Working-age population by sex, age and education (thousands), ILOSTAT database, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data (accessed on 2 June 2022).

[8] ILO (2020), Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the Future of Jobs, International Labour Organization, https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_737648/lang--en/index.htm.

[15] ILO (2015), Promoting Formal Employment Among Youth: Innovative Experiences in Latin America and the Caribbean, International Labour Organization, https://www.ilo.org/americas/publicaciones/WCMS_361990/lang--en/index.htm.

[18] ILO (2012), International Standard Classification of Occupations: ISCO-08, International Labour Organization, Geneva, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/index.htm (accessed on 8 February 2018).

[24] ILO (n.d.), Employment by sex and occupation - Annual, International Labour Organization, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[58] Jones, S. et al. (2019), “’My brother’s football teammate’s dad was a pathologist’: Serendipity and employer engagement in medical careers”, in Mann, A., P. Huddleston and E. Kashefpakdel (eds.), Essays on Employer Engagement in Education, Routledge.

[37] Jones, S., A. Mann and K. Morris (2016), “The ‘employer engagement cycle’ in secondary education: Analysing the testimonies of young British adults”, Journal of Education and Work, Vol. 29/7, pp. 834-856, https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1074665.

[42] Kashefpakdel, E. and C. Percy (2017), “Career education that works: An economic analysis using the British Cohort Study”, Journal of Education and Work, Vol. 30/3, pp. 217-234, https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2016.1177636.

[68] Kim, J. and K. Morgül (2017), “Long-term consequences of youth volunteering: Voluntary versus involuntary service”, Social Science Research, Vol. 67, pp. 160-175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.05.002.

[70] Le Gallais, T. and R. Hatcher (2014), “How school work experience policies can widen student horizons or reproduce social inequality”, in Mann, A., J. Stanley and L. Archer (eds.), Understanding Employer Engagement in Education Theories and evidence, Routledge, https://www.routledge.com/Understanding-Employer-Engagement-in-Education-Theories-and-evidence/Mann-Stanley-Archer/p/book/.

[7] Mann, A., V. Denis and C. Percy (2020), “Career ready? : How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era of COVID-19”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 241, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e1503534-en.

[19] Mann, A. et al. (2020), Dream Jobs? Teenagers’ Career Aspirations and the Future of Work, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/education/career-readiness/Dream%20Jobs%20Teenagers'%20Career%20Aspirations%20and%20the%20Future%20of%20Work.pdf.

[34] Mann, A., P. Huddleston and E. Kashefpakdel (2019), Essays on Employer Engagement in Education, Routledge.

[47] Mann, A., E. Kashefpakdel and C. Percy (2019), “Socialised social capital? The capacity of schools to use careers provision to compensate for social capital deficiencies among teenagers”, in Mann, A., P. Huddleston and E. Kashefpakdel (eds.), Essays on Employer Engagement in Education, Routledge.