2. Policies for improving FDI impacts on productivity and innovation

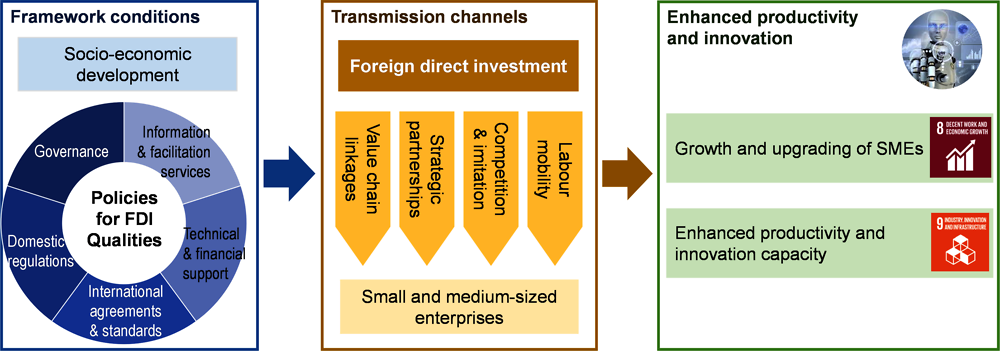

This chapter presents a Policy Toolkit to help governments channel foreign direct investment (FDI) into productivity-enhancing activities and promote productivity and innovation spillovers on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The chapter describes the various transmission channels through which FDI affects productivity and innovation as well as contextual factors determining the magnitude and direction of such impacts. It also provides a thorough overview of policies and institutions at the intersection of investment and other complementary policies that can enhance the impacts of FDI on productivity and innovation.

1. Provide strategic direction and ensure policy co-ordination and coherence on investment, innovation and SME development

Ensure that national development strategies and economic plans provide coherent and strategic directions on investment promotion, innovation and SME development objectives, and foster a whole-of-government approach to supporting productivity growth.

Mainstream investment considerations into industrial, innovation and SME policy strategies (and vice versa), and systematically consider the role that FDI can play in enhancing the productivity and competitiveness of the economy when adopting economic reform programmes.

Strengthen policy co-ordination at strategic and implementing levels by establishing inter-ministerial councils, task forces and working groups; encouraging collaboration between implementing agencies; setting up effective multi-level governance systems and involving subnational governments in whole-of-government policy-setting processes.

Periodically assess the impact of FDI and relevant policies on the productivity and innovation of the domestic economy and promote policy dialogue with foreign investors, local SMEs and other actors of the domestic research and innovation ecosystem to enhance the effectiveness of policy interventions.

2. Ensure that domestic and international regulations create a conducive business environment for FDI-driven productivity growth and innovation

Develop laws and regulations that support FDI-driven productivity growth by ensuring an open, transparent and non-discriminatory regulatory environment for investment in productive and knowledge-intensive activities, fostering competition and a level playing field, and providing strong protection of intellectual property rights (IPRs).

Simplify overly burdensome regulations that may undermine business capacity and incentives to engage in innovation and technology development while at the same time ensuring that efforts to reduce the regulatory burden on business do not lead to a “race to the bottom” in terms of social and environmental standards.

Ensure that labour market laws enable domestic firms, in particular SMEs, to retain and attract highly skilled workers through regulatory exemptions, incentives for job training of their employees, and measures to address labour shortages in FDI-intensive sectors.

Ensure that financial market laws and regulations facilitate access to finance for innovative and technology-intensive activities undertaken by foreign and domestic firms, by addressing financial stability risks, setting conducive framework conditions for the development of equity markets, and increasing the availability of alternative financing instruments.

Integrate innovation and SME policy considerations into international investment agreements (IIAs) to promote international co-operation and dialogue on technology transfer issues, while at the same time ensuring that IIAs reduce regulatory barriers to knowledge-intensive investment, foster competitive markets and strengthen domestic legal frameworks for intellectual property rights protection.

3. Stimulate knowledge-intensive investment and support the productive capacities and innovation potential of the domestic economy

Ensure that financial support to stimulate knowledge-intensive investment addresses well-identified market failures (e.g. information asymmetries, risks arising from engaging in innovation, high fixed costs of technology-intensive activities) and that the conditions and criteria for its granting are clearly defined, transparent and subject to regular reviews.

Use financial and technical support (e.g. supplier development programmes, skills development policies, technology extension services, financing, capacity building) to strengthen the absorptive capacities of domestic firms, in particular SMEs, and improve their chances of becoming suppliers and partners of foreign investors.

Promote quality infrastructure (e.g. ICT, transport and logistics, energy) through a national infrastructure plan, public investment in infrastructure development and public-private partnerships to support productive investment that creates linkages with the domestic economy.

Establish intermediary organisations and specialised facilities (e.g. technology transfer offices, collaborative laboratories, knowledge centres, business incubators, science and technology parks) to support business-to-business and science-to-business collaboration.

Implement comprehensive cluster development programmes that facilitate business linkages, foster cross-sectoral interactions and take into account place-based capabilities.

4. Facilitate knowledge and technology spillovers from FDI by eliminating information barriers and administrative hurdles

Implement investment promotion strategies that allow to identify, prioritise and attract productivity-enhancing and knowledge-intensive investment, including through intelligence gathering (e.g. market studies), sector-specific events (e.g. business fairs, country missions), and pro-active investor engagement (e.g. one-to-one meetings, campaigns, enquiry handling).

Provide comprehensive investment facilitation and aftercare services to foster greater embedding of foreign investors in local economies including by facilitating supplier linkages, strategic partnerships and collaboration with actors of the domestic entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystem.

Ensure that information pertaining to the host country’s innovation ecosystem and the productive capabilities of domestic firms is made readily available, or available upon request, to foreign investors.

Productivity reflects a country’s stage of economic development, and its resulting competitive edge and economic structure. As an economy develops, its structure typically shifts from agriculture, to light manufacturing, to heavier manufacturing, and eventually to high technology manufacturing and services, reflecting increasing levels of productivity and innovation capacity (OECD, 2014[1]). While productivity varies considerably across sectors, different value chain functions within sectors and the efficiency to conduct such activities involve varying levels of labour intensity and thus productivity levels (Box 2.1. for definitions of productivity and innovation in this policy toolkit).

Productivity and innovation figure prominently in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in SDG 8 (economic growth) and SDG 9 (industry and innovation). These goals encompass boosting overall competitiveness, reducing regional disparities, and raising productivity and innovation capacity of the typically more constrained small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Enhanced productivity and innovation are closely tied to better-paid and more stable jobs and greater human capital and skills (Chapter 3). Productivity and innovation capacity is also closely tied with the transition towards a low-carbon economy (Chapter 4). Productivity and innovation may thus support progress across a broader set of sustainability objectives (e.g. employment generation, green transition, skills development), although causality is likely to go in both directions (OECD, 2019[2]).

Productivity growth has decelerated globally as shown in recent OECD work on ‘The Future of Productivity’ (OECD, 2015[3]). The main source of the productivity slowdown is not so much a decline in innovation, but rather a drop in the pace at which innovations spread throughout the economy. Productivity growth of the globally most productive and innovative firms has remained robust in recent years but the gap between these highly productive and innovative firms and the rest has widened. For instance, although in some niche markets SMEs are more productive and innovative than large firms (Marchese et al., 2019[4]), in a number of countries a fat tail of low productivity micro and small firms usually co-exists with large multinational enterprises (MNEs), which are very productive and exposed to international competition.

SMEs are key actors for building more inclusive and sustainable growth, increasing economic resilience and improving social cohesion. Across the OECD, for instance, SMEs account for about 60% of employment and between 50% and 60% of value added and are the main drivers of productivity and innovation in many regions and cities where other global frontier innovators are absent (OECD, 2019[5]). Smaller firms face long-standing size-related barriers in dealing with stringent business conditions or accessing strategic resources such as finance, skills, knowledge, technology and infrastructure. SMEs are a very heterogeneous population whose performance in terms of productivity, wages paid and international competitiveness, vary considerably across sectors, regions and firms. Enterprise creation in the OECD has picked up over the last decade, especially in services, but newly created jobs are concentrated in low-productivity and low-wage sectors, and have increased over time, even if SMEs outperform large enterprises in the services sector in many countries (OECD, 2019[2]; 2021[6]). More lower-productivity jobs have resulted in more lower-paid jobs. SMEs, even the larger ones, typically pay employees around 20% less than large firms and the gap with foreign firms is even larger.

Innovation is key to boost productivity, and digitalisation offers SMEs new opportunities to take part in the next production revolution. Emerging digital technologies, such as big data analytics, artificial intelligence and 3D printing, enable greater product differentiation and mass customisation, better integrated supply chain systems and, overall, new digitally enhanced business models that leverage shorter distance and time to markets (OECD, 2019[7]). This is likely to benefit smaller and more responsive businesses. Digitalisation also supports open sourcing and open innovation, with large – and foreign – firms contributing to the transformation of business ecosystems through business accelerators and innovation labs that provide start-ups, innovative SMEs and R&D organisations with access to resources and markets. Digitalisation creates a range of innovative financial services for SMEs and eases SME access to skills through better job recruitment sites, outsourcing and online task hiring, or by connecting them with knowledge partners.

Digitalisation can also help SMEs integrate in global value chains (GVCs). Digitalisation has created effective mechanisms to reduce size disadvantages in international trade, such as by reducing the absolute costs associated with transport and border operations. In addition, the fragmentation of production worldwide has provided smaller businesses with significant scope for competing in specialised GVC segments and scaling up activities abroad, while capturing international knowledge spillovers and capitalising on more robust growth in emerging markets. In fact, wage gaps with large foreign firms are smaller for exporting SMEs and for highly productive SMEs, particularly those at the frontier of the digital revolution (OECD, 2021[8]).

This policy toolkit defines productivity in terms of value added per unit of labour (labour productivity), where labour is measured as total hours worked or number of employees (OECD, 2019[2]). It is important to stress that labour productivity is an incomplete gauge of efficiency. Labour productivity can rise due to increased capital spending (e.g. giving workers more machines), but does not mean all factors of production are being used more efficiently (e.g. using better machines). Labour productivity measures in services come with caveats as measures of output are often in terms of costs of labour and thus value added is difficult to measure (Triplett and Bosworth, 2008[9]). Total factor productivity or measures of return on capital (e.g. incremental capital-output ratios) would better capture efficiency improvements for capital-intensive industries like mining.

Innovation is defined as the implementation of a new or improved product (good or service) or business process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the firm’s previous products or business processes and that has been introduced on the market or brought into use by the firm (OECD/Eurostat, 2018[10]). Innovation activities include all developmental, financial and commercial activities undertaken by a firm that are intended to result in an innovation. Patented intellectual property is sometimes used as an indicator for innovation output, although not all innovations are protected with patents. A broad set of tangible and intangible assets with embedded knowledge – ranging from human and organisational capital, existing technologies to R&D – need to be accumulated and combined to yield innovation outputs (Cirera and Maloney, 2017[11]). This Policy Toolkit makes predominantly reference to two measures of innovation: process innovation and R&D intensity, or R&D per unit of value added (OECD, 2019[2]).

FDI can contribute to enhanced productivity and innovation through the activities of foreign firms (direct impact) and via knowledge and technology spillovers that arise from market interactions with domestic firms (indirect impact). The impacts of FDI may not materialise automatically, and depend on a number of economic, market and firm-specific factors. These framework conditions underpin the channels through which FDI affects domestic productivity and innovation and shape the magnitude and direction of spillovers in the host economy (Figure 2.1). Examining the performance of transmission channels and their framework conditions can shed light on the trends and complexities of the relationship between FDI and productivity, triggering dialogue and facilitating the identification of policy priorities and possible trade-offs. Annex Table 2.A.1 provides a detailed checklist of questions for governments to self-assess the impacts of FDI on productivity and innovation.

2.2.1. FDI can contribute directly to productivity enhancement

Foreign firms’ direct impact relates to their own activities and how they contribute to aggregate and sectoral productivity and innovation (Cadestin et al., 2018[12]). FDI directly relates to improved productivity and innovation at the industry or aggregate level if foreign firm activity is concentrated in sectors that are typically more productive and innovative. The opposite holds if FDI is concentrated in low-value added, less innovative, sectors. Thus, FDI can shift the sectoral composition towards more or less productive or innovative activities.

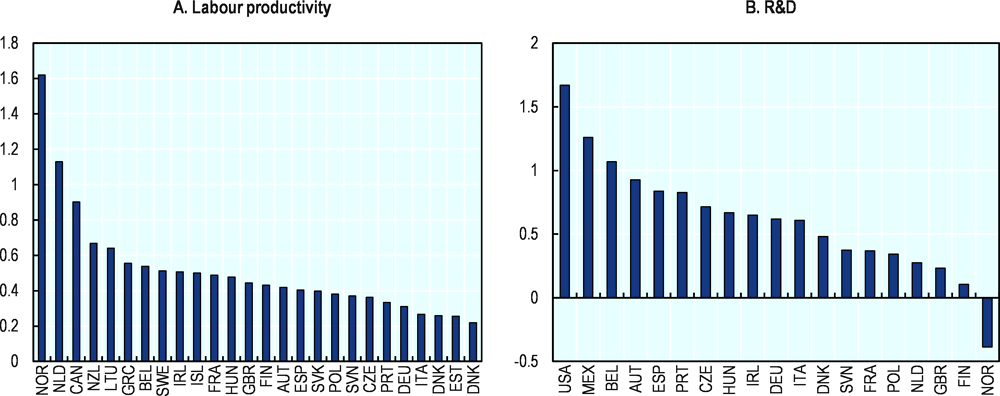

The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators suggest that, in OECD economies, sectors receiving more FDI tend to have higher labour productivity and R&D intensity levels. They also experience higher growth in labour productivity than other sectors (Figure 2.2.). The extent of FDI concentration in highly productive sectors varies across OECD countries, but tends to be greater in those with large natural resources industries (e.g. Norway, the Netherlands, Canada) where highly profitable and capital-intensive mining and extraction activities attract significant foreign MNE activity (OECD, 2019[2]). In some OECD countries, R&D-intensive manufacturing (e.g. computer equipment and electronics, chemicals, machinery) and services sectors (e.g. logistics, finance, and communications) are also associated with higher FDI activity. In the US, these high-tech and R&D-intensive sectors account for more than 50% of greenfield FDI. Expanding the analysis to developing countries reveals a rather mixed picture; foreign manufacturers do not always operate in sectors with higher average labour productivity or sectors in which process innovation is more common. This is mainly due to the large concentration of FDI in labour-intensive industries, such as food processing and garments, where the intensity of innovation is expected to be lower than in capital-intensive manufacturing.

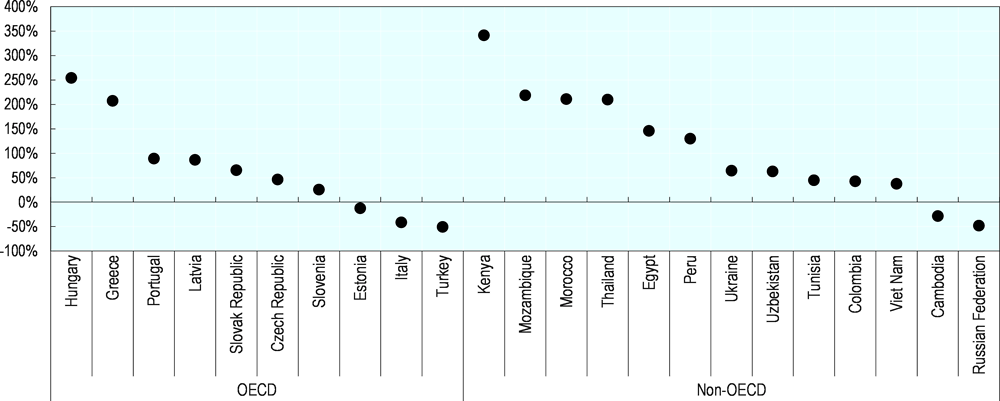

Besides the fact that foreign investors tend to invest in sectors that are typically more technology intensive, FDI’s direct impact on productivity growth is also the result of foreign firms being on average more productive than domestic firms (Figure 2.3). Accordingly, FDI can raise overall productivity even in low value-added sectors if it is more productive than local firms are. The FDI Qualities Indicators show that productivity gaps between foreign and domestic firms exhibit considerable variation across OECD and developing economies, with substantial gaps in some countries and negligible gaps in others (Figure 2.3). A recent study for the United Kingdom shows that foreign firms are around twice as productive as domestic companies are (Batten and Jacobs, 2017[13]). This is linked to foreign affiliates operating on a larger scale and having stronger access to technology, better managerial skills and more adequate resources for capital investment than domestic firms (Javorcik, 2004[14]; 2020[15]). Size also matters, since foreign affiliates are larger than the average domestic enterprise and can therefore harness economies of scale, including through their relationship with the parent company, which are not available to domestic companies (Alfaro and Chen, 2012[16]; Desai, Foley and Forbes, 2007[17]).

2.2.2. FDI can involve productivity and innovation spillovers on host economy firms

Due to foreign firms’ performance premium relative to domestic firms, policy makers often expect FDI to generate knowledge and technology spillovers that will result in increased productivity of domestic firms, especially SMEs (Caves, 2007[18]; Blomstrom and Kokko, 1998[19]). Domestic firms can benefit from knowledge and technology spillovers through various transmission channels – such as value chain linkages, strategic partnerships, competition and imitation effects, and labour mobility. These channels are themselves enabled through specific contextual factors, notably the characteristics of FDI, capabilities of domestic firms as well as broader policy and non-policy framework conditions (Gorg and Strobl, 2001[20]; Crespo and Fontoura, 2007[21]; Smeets, 2008[22]; OECD, 2022[23]).

Value chain linkages and strategic partnerships involve knowledge spillovers from foreign MNEs to their suppliers, customers and partners

Value chain relationships include supply chain linkages both upstream and downstream that involve the spillover of knowledge from foreign affiliates of multinational enterprises (MNEs) to domestic suppliers and customers; and strategic partnerships, which involve formal collaborations beyond buyer-supplier relationships, for example in the area of R&D or workforce/managerial skills upgrading.

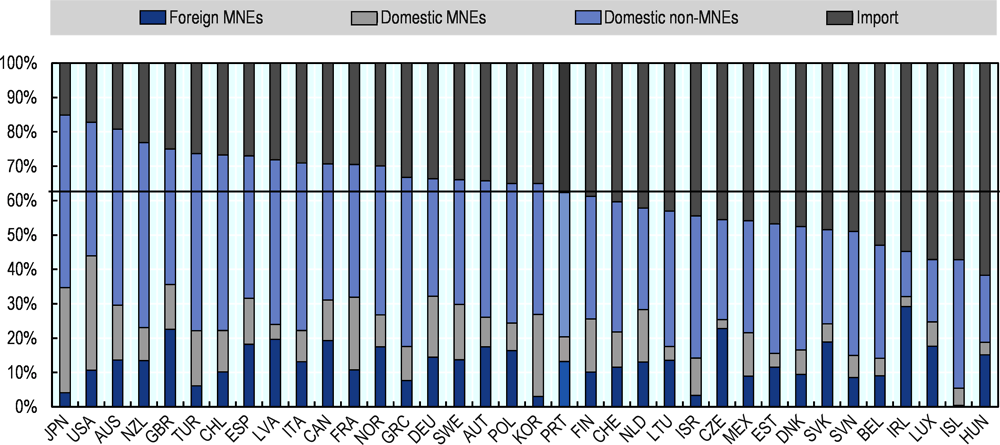

Backward linkages help domestic companies extend their market for selling (Figure 2.4) and raise the quality and competitiveness of their outputs. They generate knowledge spillovers when MNEs require better-quality inputs from local suppliers and are, therefore, willing to share knowledge and technology with them to encourage their adoption of better practices (OECD, 2022[23]). A recent study of New Zealand, for example, found that small firms do benefit from economies of scale when they supply foreign MNEs and, thereby catch up technologically with foreign firms (Doan, Maré and Iyer, 2014[24]). For such technology spillovers to happen, domestic firms require a certain level of absorptive capacity often defined in terms of technological proximity with foreign firms (see next sub-section). FDI spillovers are more commonly found in these vertical supply relationships than in the relationship between foreign MNEs and potential local competitors (horizontal spillovers), as rivalry is more naturally embedded in the latter (Rojec and Knell, 2017[25]; Javorcik, 2004[14]; Blalock and Gertler, 2008[26]) (see section on competition and imitation effects). Finally, having strong linkages with domestic firms can embed foreign affiliates more deeply into the economy, making it less likely that they will move operations elsewhere (OECD, 2022[23]).

Affiliates of foreign MNEs operate in host countries as buyers of intermediate goods and as suppliers to domestic companies (forward linkages). Forward linkages between MNEs and local buyers have a positive impact on local enterprise productivity mostly through the acquisition of better quality inputs, which were not locally available before (Criscuolo and Timmis, 2017[27]). In addition, many MNEs, especially in industrial sectors such as machinery, often offer training to their customers on the use of their products as well as information on international quality standards (Jindra, 2006[28]).

The emergence of GVCs has brought new types of FDI-SME partnerships, especially in high technology and knowledge-intensive industries, which are based on the transfer of technology and the development of cross-border R&D projects. These strategic partnerships can take many forms, including joint ventures, licensing agreements, contract manufacturing, research collaborations as well as R&D and technology alliances (Andrenelli et al., 2019[29]; OECD, 2008[30]). Strategic partnerships are the result of a shift towards an open mode of innovation, which, as noted above, has made innovation more accessible to SMEs (OECD, 2019[5]). Open innovation has increasingly been seen as a way for accelerating internal innovation and expanding the markets for external use of innovation (Chesbrough, 2003[31]). Large firms have increasingly taken part in the open innovation transformation by developing strategic partnerships with smaller enterprises or by setting up innovation labs and accelerators where start-ups and other small firms can nurture new business ideas and business models. Foreign MNEs, in particular, often seek talent and specialised knowledge in local SME and start-up ecosystems.

A recent study based on firm-level data of OECD and developing economies finds that productivity spillovers from strategic partnerships, such as manufacturing/marketing agreements and joint ventures, depend on firm-level characteristics, such as firm size, (foreign) ownership, internationally recognised certifications and staff training. Larger and foreign-owned firms as well as firms that have internationally recognised certifications and engage in staff training are more likely to improve their productivity when foreign MNEs engage in partnerships. This is consistent with studies showing that knowledge and technology spillovers from foreign MNEs depend on SME absorptive capacities (see below).

The movement of skilled workers from foreign MNEs to domestic firms can bring new knowledge and skills to local economies

Labour mobility can be an important source of knowledge spillovers in the context of FDI, notably through the movement of MNE workers to domestic firms – either through temporary arrangements such as detachments and long-term arrangements such as open-ended contracts – or through the creation by MNE workers of start-ups (i.e. corporate spin-offs).

Existing evidence suggests that firms established by MNE managers are more productive than other local firms are (Görg and Strobl, 2005[32]). Similarly, evidence from manufacturing in Norway suggests that workers who moved from foreign-owned to domestic firms retain part of their knowledge and contribute 20% more to the productivity of their firm than workers without foreign firm experience (Balsvik, 2011[33]). Recent OECD research on Ireland shows that over the period 2009-2015 more than one in four employees at foreign-owned companies either moved to a domestic firm or became self-employed. In addition, more than one in three start-up founders had previously worked at a foreign-owned company (OECD, 2020[34]). Labour mobility within Ireland is also very common among highly skilled researchers who have produced patents. One out of two patent inventors changed employer at least once during the period 2006-2016. As most inventors are based in foreign-owned companies, FDI spillovers related to inventor mobility play an important role in Ireland (OECD, 2020[34]).

On the other hand, research on Portugal provides a more sceptical perspective on potential productivity spillovers on domestic firms resulting from the mobility of workers from foreign to domestic firms (Martins, 2011[35]). Domestic firms in Portugal tend to hire ‘below-average’ workers from foreign firms who take, on average, pay cuts (which is consistent with involuntary mobility). It suggests that worker mobility is unlikely to be a major source of productivity spillovers from foreign to domestic firms. However, movements from domestic to foreign firms translate into considerable pay increases in Portugal but also in other EU Member States (Becker et al., 2020[36]). This pay increase is consistent with a generally greater ‘generosity’ in the remuneration practices of foreign firms vis-à-vis their domestic counterparts (see Chapter 3). As foreign firms attract some of the best workers in domestic firms where they experience a wage increase and acquire new knowledge, productivity spillovers from worker mobility may also (or rather) occur from domestic to foreign firms.

Competition with foreign MNEs and imitation of their business practices provide significant learning and upgrading opportunities for domestic firms

The entry of foreign firms heightens the level of competition on domestic companies, putting pressure on them to become more innovative and productive – not least to retain skilled workers (Becker et al., 2020[36]). The new standards set by foreign firms – in terms of product design, quality control or speed of delivery – can stimulate technical change, the introduction of new products, and the adoption of new management practices in local companies, all of which are possible sources of productivity growth. Foreign firms can also become a source of emulation for local companies, for example by showing better ways to run a business. Imitation and tacit learning can therefore become a channel to strengthen firm productivity at the local level.

However, if local companies are not quick to adapt, competition from foreign companies may also result in the exit of some domestic firms. Increased competition for talent may also make it more difficult for local companies to recruit skilled workers (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[37]). These effects are more likely to happen to local companies operating in the same sector or value chain of the foreign company. This is the main reason why horizontal spillovers from FDI are so rare and, when they happen, they mostly involve larger domestic companies (Gorodnichenko, Svejnar and Terrell, 2014[38]; Farole and Winkler, 2014[39]; Crespo and Fontoura, 2007[21]).

2.2.3. Magnitude and direction of FDI impacts depend on contextual factors

The magnitude and direction of FDI impacts depend on contextual factors, including the structure of the economy, the type of FDI that a country attracts, the capacity of domestic firms, in particular SMEs, to absorb knowledge from foreign firms, and economic geography factors.

The industrial structure, specialisation and internationalisation of the domestic economy influence the potential to benefit from FDI’s presence

The industrial structure, economic specialisation and technological sophistication of the host country are primary determinants of FDI inflows. Differences in the comparative advantage of economies result in differing FDI profiles, with some countries attracting more knowledge-intensive investment than others do. Economies driven by sectors with higher average productivity levels and technological intensity are expected to have greater potential to absorb and utilise the knowledge and technology brought by foreign MNEs. Countries with more advanced industrial structures tend to attract FDI in higher value added activities, involving more productive and technology-intensive activities that allow them to further advance the industrialisation process (Benfratello and Sembenelli, 2006[40]; Criscuolo and Martin, 2003[41]). Conversely, countries at early stages of the industrialisation process may benefit more from investments in lower value added sectors where local producers, often SMEs, have a comparative advantage, allowing them to move up the value chain within those sectors into activities that are more complex.

Economic specialisations may differ even within countries, leading to different FDI impacts across regions. Specialisation patterns are often driven by natural endowments and regional assets that cannot be changed or can only be changed in the long run, such as geographic location, natural resources, urban or rural settings and demographics (OECD, 2007[42]). They are often the outcome of natural configurations, market dynamics and past economic and policy choices. For instance, metropolitan regions tend to have greater endowments of human and physical capital, including more favourable demographic structure, higher intensity of skills, and better infrastructure facilities. This leads to a high concentration of knowledge-intensive FDI in urban areas and therefore greater potential for market interactions with domestic firms compared to rural areas. Within OECD countries, there are rural regions that have higher rates of growth than urban regions (OECD, 2009[43]). These regions have found ways to exploit their resource endowment in an efficient manner – for instance through specialisation that takes into account place-based capabilities. Regional economies can, therefore, attract productivity-enhancing FDI with strong spillover potential based on location-specific comparative advantages.

Beyond economic specialisations, the exposure of an economy to international markets also matters for FDI impacts on productivity and innovation. Integration into GVCs is an important driver of aggregate productivity growth and can have important consequences on the ability (and incentives) of firms to exploit the knowledge transmitted through international production networks (Gal and Witheridge, 2019[44]). Domestic firms that are exposed to international markets (through forward and backward GVC participation) may be better equipped to develop linkages and partnerships with foreign investors.

The magnitude of knowledge spillovers often depends on the characteristics of FDI

There is emerging evidence that FDI concentration in high technology manufacturing is particularly beneficial for local SMEs. For example, in three Eastern European countries (i.e. Bulgaria, Poland and Romania), a recent study found that horizontal FDI spillovers (e.g. as a result of imitation and competition effects) are observed in labour-intensive sectors, while vertical FDI spillovers (e.g. related to buy and supply linkages) are mostly observed in high technology sectors (Nicolini and Resmini, 2010[45]). In the context of the United States, FDI spillovers are particularly strong in high technology sectors, while they are largely absent in low technology sectors (Keller and Yeaple, 2009[46]). Furthermore, low-productivity small firms benefit more from FDI spillovers than high-productivity larger firms do. FDI can however be isolated from the rest of the economy in high technology manufacturing. For example, Israel has succeeded in attracting many ICT R&D labs from large US-based MNEs (e.g. Intel, IBM, etc.); however, these labs are often self-contained and have developed limited relationships with the rest of the economy (OECD, 2016[47]; OECD, 2019[5]).

The type of FDI – greenfield investment or mergers/acquisitions – that a country attracts has implications on the extent of FDI linkages with the local economy. A greenfield investment is more likely to involve the implementation of a new technology in the host country and is therefore accompanied by a direct transfer of knowledge and technology from the parent firm to the new affiliate (Farole and Winkler, 2014[48]). On the other hand, the acquisition of a domestic firm allows foreign investors to primarily access the host country’s technology as well as the already established business networks and knowledge sharing relationships possessed by the acquired firm. In this case, the deployment of the foreign investor’s technology would be implemented more gradually, thus making knowledge spillovers to domestic firms less likely in the short term but may still occur in the longer term (Crespo and Fontoura, 2007[21]; Braconier, Ekholm and Knarvik, 2001[49]; Branstetter, Fisman and Foley, 2006[50]).

The degree and structure of foreign ownership is also an important factor affecting the strength of linkages between domestic and foreign firms. Empirical evidence shows that MNEs with fully foreign-owned affiliates exert greater control upon the technologies they transfer to their foreign locations and seek to avoid knowledge and technology leakages, thereby limiting the potential for FDI spillovers (Konwar et al., 2015[51]). In contrast, MNEs with more domestic participation may have greater potential for linkages with the local economy due to better knowledge of, and well-established relations with, domestic supplier networks (Farole and Winkler, 2014[39]). This is particularly the case for joint venture agreements, which have been found to have positive horizontal spillovers on local firms (Abraham, Konings and Slootmaekers, 2010[52]). However, as highlighted in the following sections, restrictions on foreign ownership as a means to achieve knowledge spillovers should be generally avoided as they have been found to deter FDI, especially when intellectual property rights are not protected (OECD, 2021[53]).

Turning to the motives of investments, foreign investors may enter a country to expand sales in a new, often large, market (i.e. market-seeking); to tap into natural resources (resource-seeking), which is often the case in commodity sectors and agribusiness; or to achieve efficiency (efficiency-seeking), either by reducing costs (e.g. labour costs) or by seizing new local assets in the form of technology, innovation and related skills. In general, FDI motives are often interlinked, so that they cannot be fully separated but rather emerge in combination.

Domestic firms with strong absorptive capacities are better positioned to integrate new knowledge and technologies into their production processes

Global production networks and the presence of foreign MNEs provide domestic firms with an important opportunity to increase their productivity and acquire new knowledge. Technology transfers are more effective when domestic firms possess previously accumulated knowledge and innovative capabilities. This set of knowledge and capabilities is generally identified by the literature as absorptive capacity (OECD, 2022[23]). More specifically, absorptive capacity is defined as the ability of the firm to acquire, assimilate and exploit the available information, knowledge and technology that comes through interaction with other firms (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990[54]; Todorova and Durisin, 2007[55]). It largely depends on the financial, human and knowledge-based capital of companies and their ability to access the strategic resources they need to adapt to market conditions, become more productive and innovate (i.e. access to finance, skills and innovation assets, including technology, data and networks).

Empirical evidence shows that the absorptive capacity of domestic firms is an important determinant of knowledge spillovers. Domestic suppliers with better technical capabilities tend to develop more knowledge-intensive types of linkages with foreign firms (Saliola and Zanfei, 2009[56]). FDI is also found to have a positive effect on domestic productivity growth when the technology gap between domestic and foreign firms is not too large (Nicolini and Resmini, 2010[45]). The absorptive capacity is typically measured in terms of performance gaps (e.g. productivity gaps) between foreign and domestic companies as illustrated in Figure 2.3 (OECD, 2019[2]; Gal and Witheridge, 2019[44]; Farole and Winkler, 2014[48]).

However, domestic firms vary in terms of size, business model, performance and ability to access and make use of the necessary strategic resources for their growth and upgrading. This heterogeneity means that different types of firms have different chances to enter into knowledge-sharing relationships with foreign MNEs. For instance, SMEs typically have greater difficulty in attracting skilled workers, face internal and external barriers in accessing finance, and often struggle to find the technology, information and networks that would enable them to participate in innovative activities with foreign MNEs (OECD, 2019[5]; 2020[57]; 2021[58]). Given that SMEs account for almost all enterprises in both OECD and developing economies, strengthening their absorptive capacities is key to enhancing FDI’s spillover potential for domestic productivity and innovation (OECD, 2022[23]).

Recent OECD work on FDI-SME linkages and spillovers in Portugal and the Slovak Republic shows that cross-country differences in SME productivity and innovation performance can explain differences in the sourcing strategies of foreign MNEs. In Portugal, foreign investors source extensively from the domestic market, reflecting the fact that SMEs are relatively more innovative and digitally savvy than those in many other OECD economies (OECD, 2022[59]). In contrast, foreign investors in the Slovak Republic rely mainly on imports for the sourcing of inputs, which could be linked to the poor productivity performance and innovation capacity of the Slovak SME population.

Economic geography factors shape agglomeration and network dynamics, which are key for domestic firms to benefit from FDI’s presence

Economic geography factors generate spatial and agglomeration effects. The localised nature of FDI means that geographical and cultural proximity between foreign and domestic firms affects the likelihood of knowledge spillovers, which often involve tacit knowledge, and whose strength decays with distance (Audretsch and Feldman, 1996[60]). Recent work confirms that when there are productivity spillovers from FDI, these are concentrated in the same region of the investment (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[37]; Girma, Görg and Pisu, 2008[61]). When deciding where to invest, foreign firms are considering the specific factor endowment of a region – rather than just of the country. SME activity and performance are also unevenly distributed within countries, with high concentration of R&D and innovation activities and investments in few regions, and large cross-regional disparities in SME productivity (OECD, 2016[62]).

Agglomeration effects, notably through the presence of local industrial clusters, have been also reported to affect the volume of FDI and its potential for knowledge spillovers. Clusters embed characteristics such as industrial specialisation (through specialised skilled workers and suppliers) and geographical proximity that make knowledge spillovers more likely to happen, including from MNE operations. For the same reasons, MNEs can also expect to benefit from investing in local clusters, notably through the sourcing of local knowledge and technology. Evidence from the United Kingdom, Italy, Poland and Romania shows that firms located in clusters benefit from FDI, both in the same sector of the foreign affiliate and in other sectors. However, these benefits do not materialise for companies located outside the clusters (De Propris and Driffield, 2005[63]; Menghinello, De Propris and Driffield, 2010[64]; Franco and Kozovska, 2008[65]).

Productivity and innovation impacts of FDI may not materialise automatically. Besides economic and market conditions, public policies and institutional arrangements play an important role in fostering positive FDI impacts. Policies and institutions are also essential to avoid negative implications that may result from the presence of foreign firms, such as crowding out of local SMEs and jobs (see Chapter 3). Most public policies do not specifically target foreign firms; they treat foreign and domestic investors alike. Yet, the extent to which they affect the two groups, and with that their outcomes on sustainable development, can vary. Laws, regulations and public support schemes directly affect foreign firms’ choice of location, incentivise specific types of foreign firms to invest and keep away others.

The OECD Policy Framework for Investment (PFI) provides guidance on investment climate reforms that are concurrent with enabling investment for productivity growth (OECD, 2015[66]). Yet, ensuring that FDI leads to higher productivity levels and supports the competitiveness and innovation of domestic firms, in particular SMEs, requires more tailored policy considerations and increased focus on complementary policies outside the PFI, including industrial, innovation, SME and entrepreneurship policies. Given the important role that FDI can play in meeting territorial development objectives and alleviating (or sometimes exacerbating) regional disparities in economic growth and competitiveness, regional development policies are also key in shaping the economic geography of FDI impacts on productivity and innovation.

Interest in industrial policies has grown over the past decade as both OECD and developing economies are looking at how to strengthen their domestic industrial capacities, advance technological development, address the structural productivity slowdown and improve their global positioning in higher value-added segments of production (OECD, 2016[67]). There is a growing consensus that the risks associated with selective industrial policy and the influence of vested interests could be minimised. New industrial policies are increasingly focusing on market failure-correcting interventions that help build systems, create networks, develop institutions and align strategic priorities (Warwick, 2013[68]). OECD work on the role that industrial policies (including innovation and general business framework policies) can play in advancing the SDGs demonstrates that a diverse set of policy instruments (e.g. rewards and incentives, government assistance policies, compliance instruments), adequate business framework conditions, and enhanced focus on SMEs, innovative startups and local entrepreneurial ecosystems are needed to improve domestic productive capacities (OECD, 2021[69]).

This Policy Toolkit aims to provide a thorough assessment of policy initiatives, from national strategies and regulations to financial incentives and technical assistance programmes, at the intersection of these policy areas to help policy makers enhance the impacts of FDI on productivity and innovation (Table 2.1). It explains what institutional settings, regulatory conditions, policies and programmes are important ingredients of a policy mix that enables positive FDI impacts – both directly and through spillovers. The policy guidance provided in the following sections also incorporates OECD research on the contribution of FDI-SME linkages and spillovers to the productivity of local economies, based on evidence from policy approaches implemented in EU countries and regions (OECD, 2022[23]). The Policy Toolkit is structured around four broad principles and the policy instruments that support these principles (Table 2.1). Annex Table 2.A.2 provides a detailed checklist of questions for governments to self-assess their policy frameworks.

2.3.1. Provide strategic direction and ensure policy co-ordination and coherence on investment, innovation and SME development

Ensure that national strategies can foster policy coherence and a whole-of-government approach to investment promotion, innovation and SME development

The institutional framework that governs the investment, innovation and SME development policy areas differs from country to country. Different governance arrangements are feasible as long as appropriate reporting mechanisms and communication channels are in place to ensure policy alignment among different institutions and tiers of government. To this end, clear responsibility and accountability among government institutions is a pre-condition for designing and implementing coherent and effective policies that strengthen the impact of FDI on productivity and innovation.

National strategies and action plans can be important instruments for policy coherence as they are crosscutting in nature and often require whole-of-government responses to ensure their effective implementation. Establishing a clear, overarching and comprehensive strategic framework for investment promotion policy allows to create an integrated vision across government and set out long-term strategic objectives, quantifiable targets, policy pillars, related programme actions and clearly defined roles for all the institutions involved in its implementation. Such a long-term and country-wide vision for inward investment attraction should sufficiently consider FDI’s contribution to productivity growth, innovation promotion and SME development, and identify specific policy priorities, short-term and long-term targets, and policy interventions to achieve these objectives.

It is also critical that investment promotion strategies are not developed in silos, but are sufficiently aligned with and include cross-references to national strategies addressing innovation, SME and industrial policy issues. Many OECD countries have dedicated national strategies on these policy areas, while others mainstream relevant policy priorities in economic reform programmes, sectoral action plans and national development strategies. As part of their policy response to the supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, both Ireland and the Czech Republic have recently developed dedicated SME and entrepreneurship strategies, focusing on strengthening their productivity, internationalisation and innovation including through linkages with foreign MNEs (OECD, 2021[8]). Conversely, many investment and innovation promotion strategies increasingly consider the role that FDI can play in strengthening the domestic R&D ecosystem. The national investment strategies of Norway, Spain, Slovenia and the UK include specific measures aimed at supporting the upgrading of SMEs in GVCs, while the Czech Republic’s National Research, Development and Innovation Policy Strategy (2016-20) foresees business support measures to help SMEs become more involved in international R&D collaborations (OECD, 2019[5]).

Ensure effective policy co-ordination and multi-level governance in the design and implementation of investment promotion, innovation and SME policies

Actions to improve the impact of FDI on productivity and innovation need to be aligned with the objectives and priorities set by government across different policy areas. This often entails co-operating with a number of government institutions at national and subnational levels. Although co-ordination is a fundamental and longstanding problem for public administration, much of the success or failure of attempts to co-ordinate appear to depend upon country contexts, including the complexity of the institutional setting and the co-ordination instruments at play. In many OECD and developing economies, the institutional framework governing investment promotion, innovation and SME policies is structured along lines reflecting different policy domains. In Belgium, Portugal and Canada, for instance, several implementing agencies operate across the three policy areas under the supervision of different ministries. Such institutional settings may induce more complex governance systems – i.e. higher risks of information asymmetry, transaction costs and trade-offs – and require strong inter-institutional co-ordination mechanisms to overcome potential policy silos. In contrast, other governments (e.g. Croatia, Finland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Slovenia) target the entire FDI-SME-innovation ecosystem through a single government entity to facilitate co-ordination and synergies among different policy domains.

Irrespective of the complexity of the institutional setting, the set-up of effective inter-institutional co-ordination mechanisms at the strategic and policy implementation level is key. Instruments of co-ordination can be formal or informal; based on regulation, incentives, norms and information sharing; top-down relying on the authority of a lead government body, or bottom-up and emergent. For instance, high-level government councils can bring together line ministries responsible for investment, SME, innovation and industrial policy issues, implementing agencies and regional and local governments to identify priority areas where cross-ministerial policy planning and decision-making is necessary. In many countries, some of these councils are also responsible for the co-ordination of national strategies while others have been given broader mandates to foster policy dialogue, convene stakeholders and issue opinions on legislative initiatives.

At the policy implementation level, the establishment of inter-agency working groups, committees and task forces can help policy makers pull resources from different parts of government to effectively advance specific policy agendas. Inter-agency joint programming can also facilitate the implementation of crosscutting measures that span several policy areas, in particular in countries with highly fragmented institutional settings (e.g. large number of public institutions involved in policy design and implementation). In these country contexts, the Centre of Government, i.e. the office serving the highest level of the executive branch of government (e.g. presidents, prime ministers), can also play an important role in bridging bureaucratic boundaries across ministries and improving the enforcement of policy decisions. Finally, informal channels of communication between officials or job circulation of civil servants can play an important role in improving co-ordination and often suggest a relatively well-developed culture of inter-agency trust and communication.

Beyond horizontal co-ordination, effective multi-level governance is also key to ensuring policy effectiveness. Given the localised nature of foreign MNEs’ operations and the economic geography factors affecting FDI spillovers, policies aimed at strengthening FDI impacts on productivity and innovation require synergies among various levels of government and complementary expertise from regional and local actors. Responsibilities assigned to different tiers of government should therefore be clearly defined to reduce potential duplication and overlaps. Subnational governments (e.g. regional authorities, municipalities, regional development agencies) have better knowledge of local market needs and greater potential to interact with local business enterprises, foreign or domestic. Their active involvement in the design and implementation of investment promotion, innovation and SME support policies can help unlock the growth potential of the territories where these are implemented by drawing on the knowledge and expertise of local actors and linking investment promotion and SME development priorities to regional and local development strategies.

Assess the impact of FDI and relevant policies on the productivity and innovation of the domestic economy and promote policy dialogue to enhance the effectiveness of policy interventions

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) practices have been at the centre of governance frameworks as a result of the emergence of multi-dimensional policy issues and the increasing expectations over the effectiveness of public policy. The systematic collection of disaggregated data for the assessment of FDI impacts on productivity and innovation can help governments assess the economic and market conditions that underpin FDI-driven productivity growth, identify market failures and possible policy responses. The OECD FDI Qualities Indicators allow policy makers to make the necessary link between investment and host economy impacts, and assess how FDI supports national policy objectives with regard to productivity, innovation, SME growth and upgrading (OECD, 2019[2]).

Furthermore, a comprehensive framework for evaluating the impact of policies on foreign direct investors, local SMEs and other actors of the domestic research and innovation ecosystem (e.g. R&D organisations, technology parks, applied research centres, collaborative laboratories, universities) could play a crucial role as an “early warning mechanism” to identify potential policy gaps and take corrective action. For line ministries and implementing agencies responsible for investment promotion, it is critical that impacts on innovation, R&D and the capacities of domestic firms are sufficiently considered when measuring success in reaching the policy objectives of related investment promotion measures. In fact, 53% of OECD IPAs and 60% of MENA IPAs use innovation and R&D-related performance indicators when measuring the impact of their policy actions in the economy (OECD, 2018[70]). Policy impacts on the capacities of domestic firms are also evaluated by 22% of OECD IPAs and 60% of MENA IPAs.

For many OECD and developing countries, the development of better systems to track and collect reliable statistical data based on international standards is a pre-requisite to the development of more robust outcome indicators, including on productivity and innovation. The use of qualitative evaluation methodologies (e.g. surveys, benchmarking, consultations), and the establishment of data tracking tools and feedback processes can ensure that relevant and reliable data on the impact of policy interventions are available. Co-ordination and collaboration between investment promotion, innovation and SME agencies can facilitate the exchange of data, experiences and expertise. Apart from the use of quantifiable outcome-based performance indicators, a reliable assessment of policy impacts also requires strong internal capacity to plan, prepare and execute ex ante and ex post evaluations. Setting up dedicated evaluation units within implementing agencies and involving specialised staff with technical knowledge of M&E principles and implementation tools could strengthen internal competences and improve the effectiveness of their programmes.

Active engagement and consultation with foreign direct investors, local SMEs and R&D organisations is necessary for the effective implementation of relevant policies. Through their interactions with the private sector, public institutions are able to understand the challenges and expectations of foreign and domestic firms, receive feedback on the relevance of their policy programmes, and enrich policy making processes with insights from various stakeholders of the domestic research and innovation ecosystem. Mechanisms for regular public-private dialogue within specific sectors and supply chains should be combined with bottom-up communication processes to ensure that local level market needs and perspectives are fed into higher-level policy processes.

2.3.2. Ensure that domestic and international regulations create a conducive business environment for FDI-driven productivity growth and innovation

Ensure an open, transparent and non-discriminatory regulatory environment for productive and knowledge-intensive investment

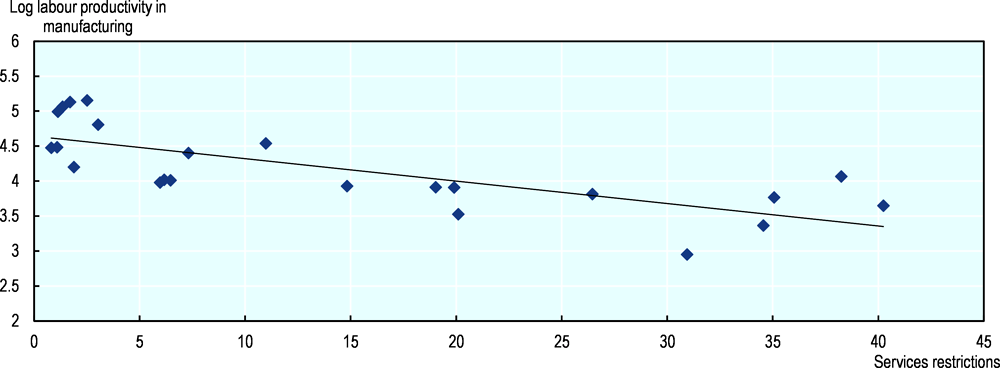

An open and non-discriminatory regulatory environment can increase the amount and spillover potential of FDI and strengthen the absorptive capacities of domestic firms, in particular SMEs (Figure 2.5). Fewer restrictions for investments in more productive, innovative and knowledge-intensive sectors can increase the direct impact that foreign firms have through their own activities on sectoral and aggregate productivity growth. Openness to FDI may not only affect productivity in industries that get market access, but also those in downstream sectors that benefit from potentially better access to high quality inputs and services domestically. Recent OECD work on Southeast Asia shows that liberalising FDI in services is positively associated with productivity in downstream manufacturing industries, where SMEs benefit in particular (OECD, 2019[71]).

FDI spillovers also tend to be larger in countries that are more open towards trade (Meyer and Sinani, 2009[72]; Havranek and Irsova, 2011[73]; Du, Harrison and Jefferson, 2011[74]). A study on Thailand’s manufacturing sector, found that technology spillovers from FDI to the domestic economy happen predominantly in sectors with low trade restrictions, while evidence from China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) suggests that vertical backward spillovers increased after its accession when tariffs were lowered and domestic content restrictions relaxed (Du, Harrison and Jefferson, 2011[74]). Trade openness can also shape the absorptive capacity of domestic firms, which are more exposed to international competition in an open trade regime, and therefore more likely to access new markets, participate in GVCs, and produce intermediate goods required by foreign investors (Havranek and Irsova, 2011[73]).

FDI-driven productivity growth and innovation may not automatically materialise just because a country is able to attract FDI (Alfaro, 2017[75]). Competition rules that ensure a level playing field for foreign and domestic firms facilitate the entry of foreign investors and, at the same time, incentivise domestic firms to become more productive, innovate and improve the quality of their products (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[37]). Firms exposed to stronger competition might also be better prepared to imitate good practices from foreign firms. As described in Section 2.2, competition and imitation effects are an important channel through which knowledge and technology spillovers from FDI take place in the host economy. In this context, it is important to assess the degree to which laws and policies promote or inhibit competition in areas of the product and services markets where competition is viable.

Policies that ensure intellectual property rights (IPR) protection are also important as they guarantee the appropriability of knowledge and innovation benefits, and determine the qualities of FDI that can be attracted. Empirical evidence suggests that where rights are strong, foreign firms are not only more likely to invest but are also more likely to engage in local R&D and more willing to share new technologies with local partners through joint ventures and licensing agreements (OECD, 2015[66]). Branstetter et al. (Branstetter, Fisman and Foley, 2006[50]) find that US MNEs respond to changes in IPR regimes abroad by increasing technology transfer to their affiliates in countries that undertake reforms to strengthen IPRs. Similarly, Javorcik (2004[14]) finds that, in Central and Eastern Europe, the strength of patent laws as well as the overall level of IPR protection increases the likelihood of attracting FDI in several high technology sectors where IPRs play an important role. Foreign investors are also found to be more likely to engage in local production, as opposed to focusing solely on setting up distribution networks, in countries with stronger IPR regimes, increasing therefore the potential for more linkages with the local economy.

Several countries have chosen to introduce local content requirements (LCRs) to induce foreign firms to use domestically manufactured goods or domestically supplied services in exchange for market access in certain strategic sectors. Recent OECD work shows that, while LCRs may help governments achieve certain short-term objectives in targeted industries (e.g. potential learning and technological spillovers, economies of scale), they undermine long-term competitiveness and may prove to be detrimental for FDI attraction and productivity growth in the long run (Stone, Messent and Flaig, 2015[76]). LCRs may restrain competition from imports, which might contribute to higher production costs and ultimately higher prices to downstream industries and consumers. The literature on the potential effects of LCRs also points to potential market distortions and inefficiencies arising from a suboptimal allocation of resources. They may undermine the original goals for imposing LCRs. Targeted incentives that generate less negative economy-wide effects and do not impede market access may be preferable to incentivise linkages between FDI and domestic firms (see section on financial support and technical assistance).

Consider the impact of laws and regulations on business capacity and incentives to engage in innovation and technology development

Firm size is a determinant of absorptive capacity and a critical factor shaping a firm’s ability to move towards high value added, knowledge-based production. OECD and developing economies are often dominated by SMEs with low productivity, which may find it difficult to grow and obtain a critical scale that would allow them to join GVCs, participate in innovation activities and become suppliers and partners of foreign firms. Overly burdensome regulations often perpetuate informality, particularly of smaller and less productive firms, which have less capacity to screen the regulatory landscape and allocate the necessary resources to address legal and regulatory requirements (OECD, 2018[77]). It is important that a conducive business environment is created and regulatory hurdles removed to enable small businesses to expand. These include areas such as the ease of registering a business, dealing with reporting and tax compliance requirements, trading across borders, resolving insolvency and dealing with licence and permit systems.

Stringent regulations can also deter innovation by imposing high compliance costs that reduce the attractiveness of R&D and limit the capacity of domestic entrepreneurs and foreign firms to experiment with alternative business and production models (Davidson, Kauffmann and de Liedekerke, 2021[78]). One option for encouraging FDI-driven productivity growth and innovation is to develop laws and regulations that are sufficiently flexible and forward-looking to anticipate and adapt to fast-changing technologies. This is particularly the case for regulations addressing issues related to digital innovation (e.g. use of AI applications, robotics, Internet of Things). Related technological standards should be also updated regularly to catch up with the latest market developments. Finally, regulatory impact assessment (RIA) tools and processes should move beyond assessing the economic impacts of regulations (e.g. impacts on competition, economic growth, etc.) to also cover impacts on SME competitiveness, innovation and the internationalisation of the economy.

In many countries, the simplification of the regulatory framework is often combined with targeted easing of the regulatory burden for certain types of investment. This usually comes in the form of special investment regimes granted to FDI projects that are deemed to be of strategic importance for the host economy, giving access to expedited administrative and licensing procedures. These special regimes are usually predicated on certain conditions such as creating a number of jobs, investing in knowledge-intensive and productivity-enhancing sectors, or benefitting specific geographic areas. In Portugal, for instance, the government has introduced several special regulatory regimes allowing investors to benefit from simplified licensing procedures, conditional to introducing innovative and technology-based production processes in co-operation with domestic R&D institutions (OECD, 2022[59]). Many developing countries have also established special economic zones (SEZs) as a tool to attract FDI that creates linkages with the local economy.

Evidence on the effectiveness of these regulatory measures has been mixed. Anecdotal evidence on their impacts, in particular of the SEZs, shows that they have often failed to sustain innovation and competitiveness over time, delivering little technological upgrading or new firm creation. In many instances, SEZs have been criticised for negative social and environmental impacts as a result of excessive competition between regions and a misuse of resources and land where the SEZs are located (Farole and Akinci, 2011[79]; OECD, 2018[80]). In principle, regulatory concessions should not be used as a substitute for improving the general investment climate but instead be embedded in broader national development strategies. Accompanying measures need to be in place to generate productivity spillovers on the rest of the economy, including supplier development programmes, business matchmaking services, and initiatives to engage the private sector and local education institutions in cluster building activities.

It is also critical that policy efforts to reduce the regulatory burden on business do not lead to a “race to the bottom” in terms of social and environmental standards (see chapters 3, 4 and 5). This becomes even more crucial for industries driven by digital innovation, which rely on alternative business models and often lead to new and more precarious forms of employment or weakened social protection conditions (OECD, 2020[81]). In fact, regulation should mitigate the potential socio-economic risks arising from the adoption of new, innovative and digitally enabled business models while at the same time ensuring that regulatory responses are proportional, set out some level of certainty and predictability, and do not stifle the innovation potential of the economy.

Ensure that labour market regulations facilitate FDI spillovers through labour mobility

Labour market regulations shape FDI impacts on productivity and innovation by affecting the potential for knowledge and technology spillovers through labour mobility (see section 2.2) and the availability of skills in the local labour force. Recent evidence from EU countries shows that less rigid labour markets with strong absorptive capacities are better positioned to moderate any adverse labour market effects of FDI, in particular the crowding out of employees in domestic firms, which occurs when foreign and domestic firms compete for the same scarce labour resources (Becker et al., 2020[36]). In contrast, the benefits for a local economy from FDI are lowest where there exist a combination of stringent employment protection legislation and low absorptive capacities. This is because foreign firms seek to attract local talent by offering higher wages that less productive domestic firms are unable to match. Increased wage disparities coupled with rigid labour market conditions limit the ability of domestic firms to retain and attract skilled workers, holding back labour mobility and the potential for knowledge spillovers that this entails.

These findings highlight the need to examine labour market regulations and their role in FDI-driven productivity growth by looking at how they relate to other drivers of FDI impacts, namely domestic SME performance and the availability (or lack) of skills in the local labour force. Spillovers from labour mobility cannot be fully leveraged unless structural challenges related to the absorptive capacities of domestic firms, in particular SMEs, are addressed, and the complexity of hiring regulations reduced (and with that the disproportionate impact they may have on small businesses). Targeted measures that allow micro and small firms to be exempted from certain procedural requirements or other hiring restrictions of the labour legislation can facilitate the movement of highly skilled workers from foreign affiliates to the domestic entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Encouraging the uptake of permanent employment can also have a positive impact on domestic firms’ willingness to invest in job training of their employees, which is an important component of a firm’s absorptive capacity. Evidence on the role of employment protection regulations in shaping the incentives of firms to invest in formal training shows that enforcing stricter hiring regulations for temporary contracts and less rigid regulations for dismissals of permanent workers is associated with higher investment by firms in the human capital of their employees (Almeida and Aterido, 2011[82]). Similarly, a stricter enforcement of employment protection regulation is found to have a positive impact on firms’ willingness to upskill their employees. This is mainly because firms have greater incentive to invest in firm-specific knowledge and skills for employees who stay longer on the job and seek to exploit the career advancement opportunities provided by the firm (OECD, 2020[83]). Chapter 3 provides a detailed analysis of the positive impacts that labour market regulations can have on human capital formation.

Linked to the need for a skilled labour force is the increasing number of governments that introduce regulatory incentives to encourage workforce skills development and facilitate the immigration of business talent as a way to help domestic economies address labour shortages. Some OECD countries have introduced statutory rights for employees for training leave – however, their take-up is generally not high with less than 2% of employees benefitting from such measures (OECD, 2019[5]). In recent years, there has been also an increase of entrepreneur visa programmes (e.g. Startup Visa, Tech Visa), which seek to attract innovative entrepreneurs and highly skilled workers by allowing them to obtain residence and employment rights. For the visa to be granted, entrepreneurs usually have to demonstrate solid business and financial plans and undertake innovative activities in knowledge-intensive sectors. The impact of these schemes on the productivity and innovation of domestic economies is not clear yet, but other factors such as labour market conditions, the presence of a thriving startup ecosystem, and the quality of the business environment are thought to be key determinants.

Ensure that financial market laws and regulations facilitate access to finance for innovative and technology-intensive activities

Well-functioning financial markets can facilitate FDI spillovers by enabling SMEs to access supply chain finance and secure investments for entrepreneurial activity. Studies find that well-developed financial markets can strengthen the absorptive capacity of domestic firms and provide the liquidity that SMEs need to export, develop new products and invest in technology upgrading (Farole and Winkler, 2014[48]). For many SMEs, the high fixed costs of establishing a distribution network and adjusting their products for overseas standards, often require external finance (OECD, 2020[57]). Similarly, access to finance is an important condition for foreign firms that seek to finance collaborative technology-based projects or enter into partnerships with domestic firms (for instance, through joint ventures).

Financial stability risks (e.g. low bank profitability, high sovereign and corporate debt) and structural market deficiencies (e.g. underdeveloped equity markets and credit rating systems, insufficient market liquidity, weak contract enforcement, inefficiencies in the judicial system, etc.) are often the most common causes that hold back the necessary capital that foreign and domestic firms need to expand their operations. Governments can play an important role in improving access to credit by creating a regulatory environment that provides flexible collateral options and transparent legal recourse in cases of default, and by establishing easily accessible financial support schemes (OECD, 2019[5]). Regulatory reforms that facilitate market-based long-term debt financing, increase the availability of alternative financing instruments, and promote access to equity capital through the stock market can help free up capital for innovative business projects. Raising awareness about alternative forms of financing such as crowdfunding, venture capital and business angels, and encouraging firms to source finance from equity markets can also further stimulate innovative business activities.

Integrate innovation and SME policy considerations into international investment agreements

Most investment treaties in force today do not contain provisions that seek expressly to promote productivity and innovation. Rather, they have tended to focus almost exclusively on providing legal protections to investors. Recent international investment agreements (IIAs) concluded in the past decade, especially free trade agreements (FTAs) that address investment issues, have covered broader policy areas beyond investment protection that pertain to fostering international co-operation on science, technology and innovation (STI) policy and strengthening the capacities of SMEs to engage in international trade and investment.

Recent IIAs address regulatory issues affecting host country SMEs by envisaging international co-operation and dialogue to promote investment opportunities for SMEs in the economies of the treaty parties (Clicteur et al., 2021[84]). SME-specific provisions may take the form of standalone chapters, or be mainstreamed across FTA chapters dealing with e-commerce, trade facilitation, procurement, investment and trade in services (Box 2.2). The degree of commitment that they require varies; from general principles emphasising the importance of SMEs in international trade and investment, to binding agreements on simplified administrative procedures for SMEs trading or investing abroad, and commitments to the establishment of dedicated SME Committees to ensure co-operation and information sharing among treaty signatories (UKTPO, 2020[85]; Lodrant and Cernat, 2017[86]). These initiatives may help SMEs to overcome a lack of familiarity with foreign markets as well as logistical, managerial and other challenges when trading or investing abroad. By facilitating the internationalisation of host country SMEs, these provisions can also increase the exposure of SMEs to international competition and improve their capacities to become suppliers and partners of foreign firms, including foreign direct investors located in their own countries.

The inclusion of STI provisions in bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and regional trade agreements (RTAs) is another channel through which governments often seek to signal their readiness to attract FDI in high-technology areas, promote international co-operation on technology transfer issues and strengthen domestic innovation capabilities. Provisions on intellectual property rights (IPRs) are the most commonly found STI provisions in IIAs (Stone, Kim and Engen, 2017[87]). They often include general principles stressing the importance of IPRs for innovation and economic growth; binding commitments on specific IP issues (e.g. minimum standards for IP protection, use and enforcement of IPRs, settlement of IP disputes); and bilateral or multilateral co-operation provisions. The economy-wide effects of including IPR provisions in RTAs or BITs have seldom been quantified, but it is widely accepted that they can support innovation in the treaty party economies to the extent that they lead to improvements in domestic laws in these areas (WTO, 2014[88]). New IIAs concluded over the past few years have been also increasingly incorporating more general provisions on the digital economy (e.g. data protection, cybersecurity, data localisation and online consumer protection rules) as well as STI co-operation (Stone, Kim and Engen, 2017[87]). The latter usually seek to facilitate the exchange of information on cross-border innovation programmes, the joint conduct of R&D projects; the exchange of country visits of specialised delegations, industry representatives, universities and research centres; and the promotion of public-private sector partnerships for the development of innovative products and services (Box 2.2).

Another feature of some recent IIAs that can affect productivity and innovation is disciplines on performance requirements. These provisions, inspired by the WTO TRIMs Agreement, prohibit treaty parties from imposing mandatory performance requirements on incoming foreign investors such as forced technology transfers, local content or R&D quotas. As outlined in the previous section, performance requirements have been found to deter FDI inflows and undermine the long-term competitiveness of the domestic economy. Some IIAs adopt a more nuanced approach by creating express exceptions or reservations in some areas (e.g. allowing governments to impose technology transfers on foreign investors as part of investment screening review processes) or allowing governments to attach certain conditions to non-mandatory advantages offered under domestic law (e.g. incentive schemes, tax breaks, subsidies, etc.) that would require foreign investors to perform in some way to benefit the domestic economy (e.g. locate production, train or employ workers, carry out R&D locally, etc.). The impacts of such policies need to be carefully weighed and examined alongside other factors that drive FDI spillovers such as the productive capacities of domestic firms and the availability (or lack) of skills in the local labour market.

Some recent IIAs also contain government commitments on market access, investment facilitation and promoting fair competition that may generate tangible impacts for productivity and innovation. Through the elimination of regulatory barriers to investment based on nationality, IIAs can stimulate more potential FDI primarily based on market considerations, which in turn can generate many benefits for host economies as described above. Greater openness to foreign competition can lead to new competition for local SMEs, which may stimulate greater productivity or lead to crowding-out effects depending on the maturity of the domestic market. In addition to market access barriers, businesses can face myriad other obstacles to effective entry and success of FDI in foreign markets. Recent IIAs have sought to alleviate these barriers through rules to address problems such as transfers and visas for personnel, clarity on different environmental and technical standards, a lack of transparency in regulatory procedures, or logistics issues.

The EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)