Executive summary

Well-being is generally high, but not across the board

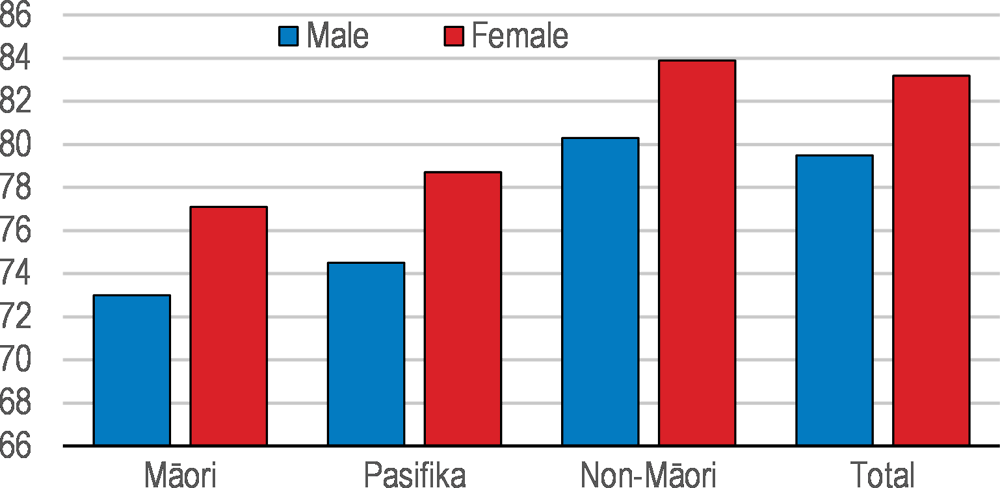

Current well-being in New Zealand is generally high, but some weaknesses have emerged. Performance is very good for employment and unemployment, perceived health, social support, air quality and life satisfaction but not so good for earnings and household income, housing affordability and the incidence of long working hours. The income distribution is more unequal than the OECD average, reflecting lower than average redistribution through taxes and transfers, and is more skewed towards high-income households. Education, health and housing outcomes vary strongly by socio-economic background and ethnicity – Māori and Pasifika tend to fare worse.

Improving the well-being of New Zealanders and their families is one of three strategic priorities for the government. Their broad programme includes amending legislation to embed well-being objective-setting and reporting; developing well-being frameworks and indicator sets; and using well-being evidence to inform budget priority-setting and decision-making, including by embedding well-being analysis in policy tools. Other strategic priorities are building a productive, sustainable and inclusive economy, and providing leadership.

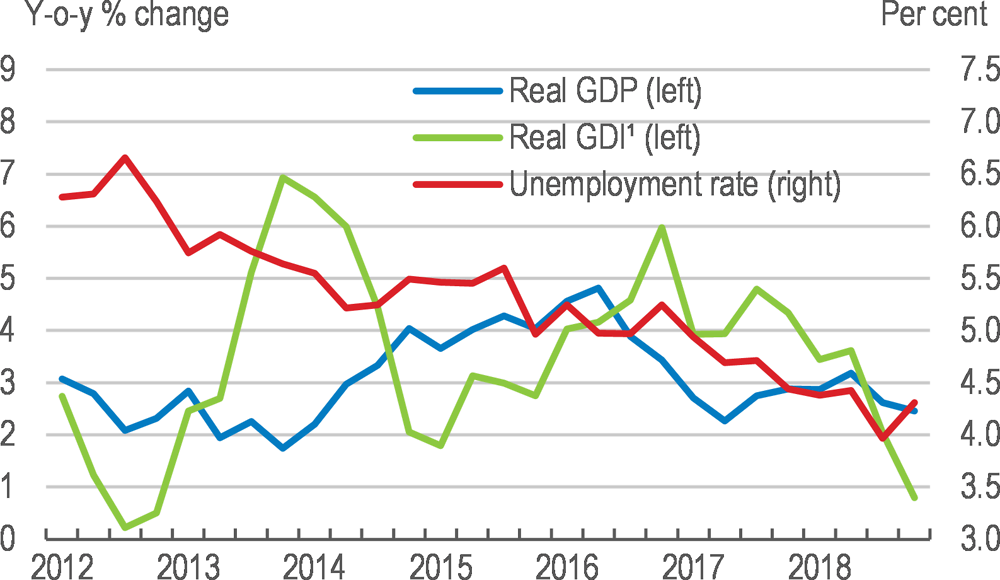

Economic growth has stabilised

Economic growth is an important driver of well-being through its positive contribution to jobs and income. Growth has stabilised at around 2½ per cent, just under 1% on a per capita basis. Private consumption growth has lost some strength since 2016, as migration inflows have fallen from their peak and wealth gains from house price appreciation have moderated. Low business confidence has contributed to weak business investment, despite capacity constraints. Terms of trade have come back slightly from a late 2017 peak and tourism demand remains strong, albeit slowing.

Macroeconomic policy is expansionary, but fiscal policy is set to become broadly neutral. The policy interest rate is at a record low of 1.5% and is not expected to increase before end-2020. Fiscal policy became expansionary in 2018 as a consequence of a pick-up in spending on infrastructure, health, education and transfer payments to students and families. The fiscal stance is projected to become broadly neutral in 2020 in the absence of further discretionary measures. New Zealand’s strong fiscal position contributes to well-being by preserving economic capital and supporting macroeconomic stability.

Economic growth is projected to remain close to potential. Lower immigration and house price inflation will continue to weigh on consumption, offset by minimum wage hikes and pay equity decisions. External demand is expected to grow more slowly, weighing on export growth.

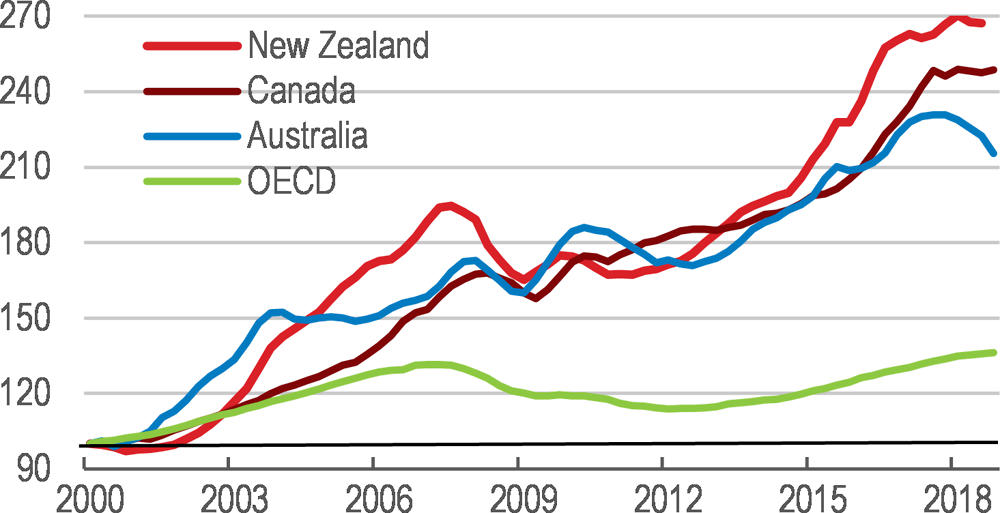

The main domestic risk is a housing market correction, though there is no evidence of oversupply. The effects of a contraction would be magnified by the elevated household debt levels resulting from sustained house price increases. Rising trade restrictions internationally could have substantial negative repercussions for New Zealand as a small open economy without a large domestic market and heavily exposed to international commodity prices.

Labour market reforms have been initiated

The minimum wage is high relative to the median and is being substantially increased, which is projected to more than double the share of hours worked at the minimum wage to 19%. This will increase wages for the low paid but, if effects resemble those in other OECD countries, may reduce youth, female and low-skilled employment. The increase is unlikely to have much effect on poverty because it is not well-targeted at low-income households.

The government plans to introduce Fair Pay Agreements (FPAs) − a process to enable parties that meet certain criteria to negotiate minimum terms and conditions that will apply across a sector or occupation − to increase workers’ bargaining power and wages. FPAs are likely to reduce wage inequality, but also productivity growth in sectors covered if significant freedom to determine terms and conditions of employment at the enterprise level is not retained.

A Bill is before Parliament to facilitate pay equity negotiations to achieve equal pay for work of equal value. Enhanced gender pay equity will contribute to further reducing New Zealand’s small gender pay gap. Back pay could have negative financial effects on some SMEs but the likelihood and extent of any back pay is uncertain.

Changes are underway at the central bank

The government has completed the first phase of its review of the Reserve Bank Act, clarifying the role of the Bank to ‘promote the prosperity and well-being of New Zealanders’. The second phase is a good opportunity to introduce deposit insurance to protect depositors and support financial stability.

Separately, the Reserve Bank has proposed large hikes in bank capital requirements. High bank capital requirements reduce the costs from financial crises, but might also dampen economic activity through higher lending rates. On balance and notwithstanding considerable uncertainty, increases in bank capital are likely to have net benefits, but the impacts should be carefully monitored.

A well-being approach to policymaking is being implemented

Building on many years of work, the Treasury has recently updated its Living Standards Framework and released a Dashboard for measuring and reporting on well-being. The concepts and indicators included in the Dashboard are generally well-aligned with those measured in other countries, but there are gaps, including in some aspects of natural capital where New Zealand has experienced some downward trends or fares poorly. Work to address these gaps is ongoing, and a more comprehensive database (Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand) is being developed by Stats NZ.

Five priorities were agreed for the 2019 Budget using well-being evidence. All agencies seeking funding for new initiatives were expected to identify well-being impacts. The Treasury’s cost-benefit analysis tool has been updated to link impacts to well-being domains and can be used as a supporting tool for developing budget bids. Priority was given to initiatives that align with the budget priorities and show cross-agency and cross-portfolio collaboration.

The government is also considering options for embedding a well-being approach in legislation. The latest proposals for the Public Finance Act would require governments to set well-being objectives and report on them annually, while the Treasury would report on well-being every four years. This follows the passing of the Child Poverty Reduction Act in 2018, which put into law the requirement to have both measures of and targets for child poverty.

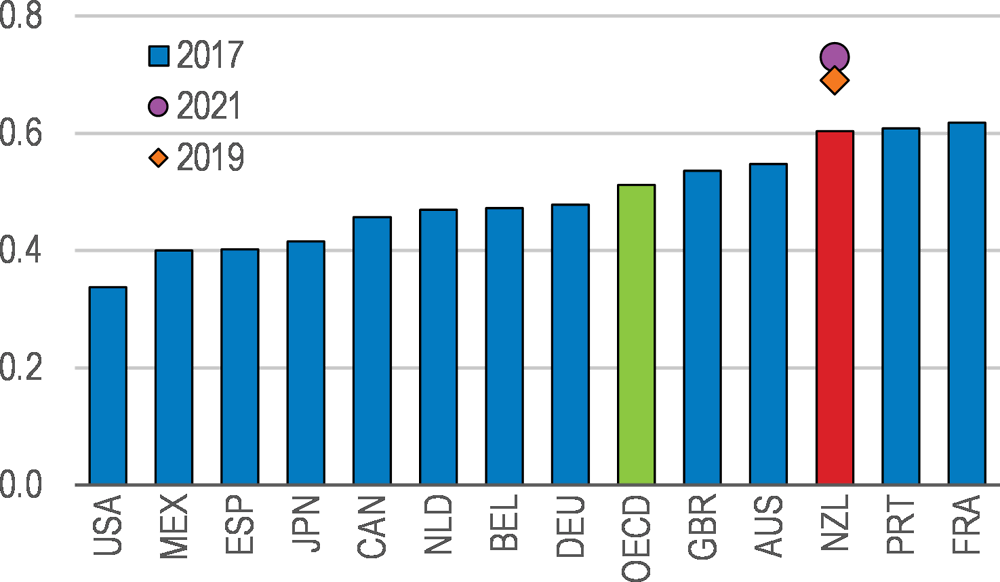

Water and climate change are key challenges for future well-being

New Zealand’s performance on resources for future well-being is mixed. The sustainability of well-being over time is assessed by the OECD through four stocks of resources or “capitals”: financial and physical, human, social and natural capital. Social capital is a clear strength in New Zealand, with high levels of trust and civic engagement and low perceptions of corruption. High skills levels contribute to human capital, although high and rising obesity rates threaten future health. Financial and physical capital suffers from low investment in R&D. Household wealth, while high on average, is skewed towards the wealthy, and household debt has risen alongside rapid increases in house prices.

New Zealand’s natural capital is under threat. Increasing diffuse sources of pollution have reduced water quality in many areas, in particular due to the expansion of dairy farming. While New Zealand has abundant freshwater overall, water scarcity is a growing concern in key agricultural areas. Pricing and permit trading should be expanded (subject to agreeing iwi (tribal)/Māori rights) to achieve water quality and quantity objectives efficiently.

The government is drafting a Zero Carbon Bill that will set an emissions reduction target for 2050 but gross GHG emissions are projected to exceed the 2030 Paris Agreement commitment. New Zealand has one of the highest emissions per capita in the OECD (almost half of which are biological emissions from agriculture) and they have fallen little since 2010. The price of emissions needs to be consistent with New Zealand’s intended transition to a low-emissions economy. A date for the inclusion of biological emissions from agriculture should be announced or alternative pricing and regulatory measures taken to enable the industry to adapt to lower emissions levels.

Immigration’s contribution to well-being should be enhanced

Immigration increases economic well-being of both immigrants and most of the NZ-born, although associated increases in housing costs, congestion and pollution have had negative effects. Immigration has small positive effects on per capita incomes and does not reduce wage rates or employment on average for the NZ-born. However, temporary migration has small negative impacts on new hires of some groups of people, notably social welfare beneficiaries living outside the (16) most urbanised areas. Immigrants initially earn less than the comparable native-born and the gap closes slowly. Nevertheless, immigrants have similar well-being outcomes to the native-born, which are generally high.

Immigration policy has been changed to target immigrants with better labour market prospects. Changes were made in 2017 to temporary migration programmes, which are a conduit to permanent residence, and to the points system for skilled immigration to increase skills requirements. Planned changes to employer-assisted temporary work visas will reduce employers’ reliance on low-skilled migration and, together with education and welfare reforms, improve job prospects for some lower-skilled New Zealanders.

Improving settlement programmes would enhance integration. Programmes that connect job-seeking immigrants and employers should be complemented by mentoring programmes, which help immigrants overcome under-representation in high-quality jobs by developing professional networks, and bridge programmes, which help with post-secondary credentials recognition in regulated occupations.

Some migrants on temporary work visas are vulnerable to exploitation and some have been exploited. They cannot easily leave their employer without seeking a variation of conditions for their visa. A review is underway to identify effective and sustainable solutions.

More needs to be done on housing

More needs to be done to increase housing supply and improve affordability. A raft of measures are in train to enable additional housing supply, including government delivery of new affordable housing through KiwiBuild. Even so, strict regulatory containment policies still impede densification and should be replaced with rules that better align with desired outcomes. Infrastructure funding pressures faced by local governments hinder development. They could be relieved through sharing in a tax base linked to local economic activity, more user charging for roads and water, and removing barriers to use of targeted local taxes on property value increases from changes in land use regulation or from infrastructure investment. Re-focusing KiwiBuild towards enabling the supply of land would direct government efforts towards key bottlenecks and allocate risks to developers where they are better placed to manage them. Subsidising construction of affordable rental housing, as in several other OECD countries, would be another way to support affordability.

Reforms are also needed to assist low-income renters, whose well-being has suffered most from declining affordability. Proposed reforms would go some way to rectifying low security of tenure for renters but should go further to prevent landlords from using rent increases that are disconnected from market developments as a means of eviction. Social housing supply is low by international comparison and there are poor outcomes for at-risk groups, including overcrowding, low quality housing and high homelessness. The waiting list for social housing has more than doubled in the past two years and larger increases in supply than those currently underway are needed. In part this could be achieved by reallocating funding from KiwiBuild, which would help better target those in need.