3. Norway’s comprehensive model of family policies

Comprehensive family policy helps both fathers and mothers to engage full-time in the labour market and can play an important role in families’ choices to have (more) children. Overall, the Norwegian family policy framework is a well-functioning system, which is rightfully seen as a good practice example in the OECD. However, also in Norway, family policies can be fine-tuned to improve coverage whilst also promoting a greater gender balance in its use. This chapter analyses the current state of Norway’s family policy framework of parental leave policies, family cash benefits, early childhood education and care provisions, as well as out-of-school-hours supports.

Norwegian families are supported by a wide range of family policies that offer generous paid parental leave as well as universal and affordable early childhood education and care. These supports help both fathers and mothers to participate full-time in the labour market and can be important in promoting families’ choice to have (more) children. Even though the Norwegian set of policies is one of the most comprehensive across the OECD, some families may not always have access to supports when they would like to do so or otherwise face barriers in practice. Also, men face different eligibility conditions when taking shareable parental leave than women, which may reduce their average leave-taking beyond the father’s quota. Overall, however, the Norwegian family policy system is working well and is rightfully seen as one of the “leaders” in family-policy in the OECD.

This chapter first provides an overview of Norway’s family stance and looks in some details at parental leave, cash for care, Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and out-of-school-hours (OSH) services. Throughout the chapter it refers to policy experiences across the OECD and the evidence in the literature on the impact of family policies on fertility behaviour. It also provides new evidence from cross-national econometric analysis on the impact of policy on the total fertility rate (TFR) and the mean age of mothers at the birth of their children (MAB).

3.1.1. Main findings

Norway provides a comprehensive family policy environment with well-paid parental leave and universal and affordable formal childcare. The aim of Norway’s family policy environment is not primarily to encourage fertility, but rather the assurance of safe economic and social conditions that support children’s development over the early life-course and contribute to overall well-being of families and support the reconciliation of work and family responsibilities of both parents.

Through a combination of paid parental leave and cash-for-care benefits, Norway provides comparatively long entitlements to care for young children at home. However, while parental leave is well-paid, replacing income up to a ceiling of NOK 55 740 (USD 5 636) per month, close to the average full-time wage, the cash-for-care benefit is paid at a lower rate of NOK 7 500 (USD 758) per month. Both parents have earmarked parental leave quotas, topped up with a sharable leave period. While there is high take-up among fathers, they rarely take leave beyond their quota. Fathers are also subject to stricter eligibility requirements for shareable leave, with entitlement only if the mother works or studies at a minimum of 75% of full-time hours. To further increase leave uptake by fathers, Norway could consider aligning the eligibility requirements for both parents to take shareable parental leave, so that mothers do not have to be in employment or study for fathers to use it. Alternatively, shareable parental leave could be phased out over time, while eventually granting each parent half of the entire leave at default with the option of transferring some of weeks to their partner, similar to approaches in Iceland and Finland.

Since large-scale increases in the availability of early childhood education and care (ECEC) places in the early 2000s, Norway provides universal and affordable childcare in their kindergartens with a statutory right to a place from age 1. Norway therefore has very high enrolment in ECEC, which is often positively related to fertility trends across the OECD. However, even though a statutory right should ensure a continuum of family-friendly supports throughout childhood in theory, in practice, there can be gaps. For example, depending on their birthday, children who are born between 1 December and 1 July are 13 to 20 months old before they become entitled to a kindergarten place, which leaves their parents to find alternative care solutions. One option to avoid this gap would be to grant the right to a kindergarten place at the end of the month children turn 1 for all children regardless of their birthday. This would contribute to phasing out the cash-for-care benefits, which are frequently used to cover for the time between paid parental leave and kindergarten enrolment. Such an approach is, for example, taken in Denmark, where children have the right to attend ECEC once they are 26 weeks old, this may not work for all children in practice, but the approach gives a clear policy signal on the prevailing rights of families.

A wide availability of discounts on parental fees for kindergartens makes the ECEC system affordable for most. While this is particularly helpful for low-income families and those with multiple children in ECEC, there is a significant gap in eligibility and take-up. This may have been related to difficult documentation procedures based on previous tax records that parents had to submit to municipalities. This process has recently been streamlined by allowing municipalities to directly obtain administrative records from the tax authorities to automatically grant eligible families discounts.

All Norwegian municipalities offer out-of-school hours services (OSH) which help families combine their family and career commitments once their children enter primary school. While take-up among the youngest school children is high, attendance drops sharply for children in higher grades of primary school. Older children lose appetite for attending OSH services, but relatively high fees may also play a role. For example, ECEC fees are lower for the second child of a family who participates in ECEC, but this discount does not apply to families with one child in ECEC and another attending OSH-services. The recent introduction of free 12 hours of OSH for first graders is a good step in making the system more affordable but could be extended to further grades as well, as done in some municipalities. The implementation of a national OSH-curriculum in August 2021 may also improve and streamline the quality and attractiveness of OSH-services in Norway.

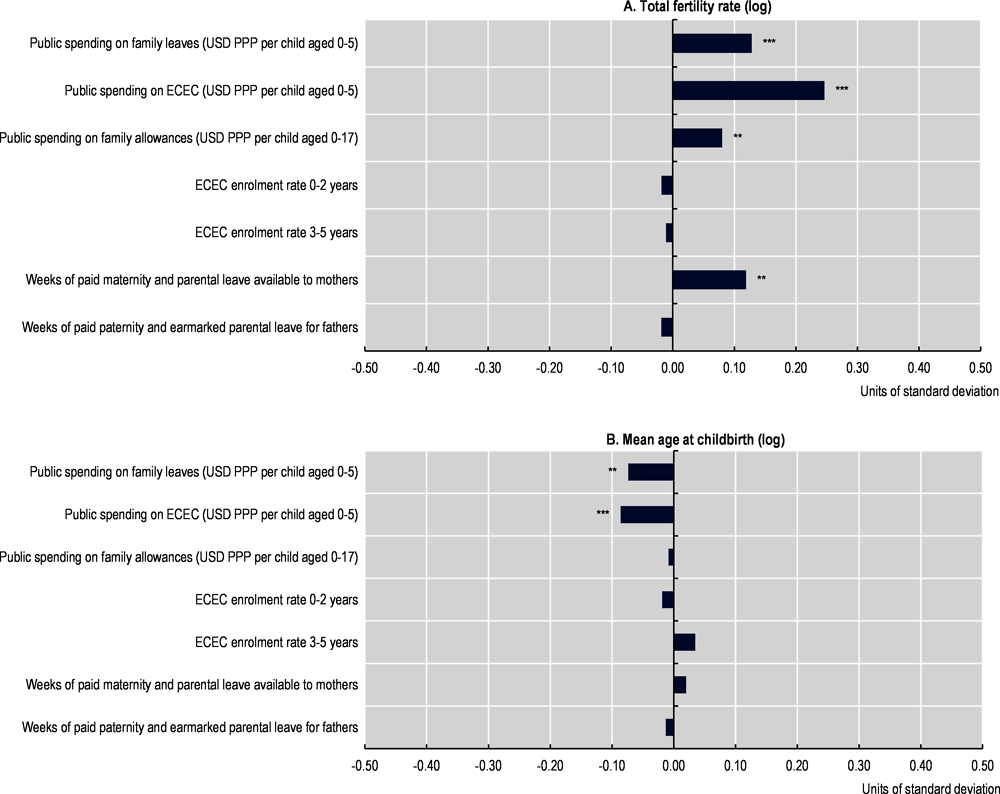

To explore what underlying drivers are associated with changes in fertility rates, this chapter also presents an OECD-wide regression that estimates the effect of changes in different aspects of the family policy framework in a specific country and its respective fertility outcomes. The results do not establish causal relationships but do suggest that fertility outcomes are associated with public expenditure on the provision of ECEC services and parental leave allowances. Increases in both expenditure categories are significantly associated with rising TFRs and decreases in the mean age of mothers at the birth of their children. At the same time, expansions of parental leave entitlements are also linked to changes in fertility outcomes, associating more leave available to mothers with higher TFRs. Increases in family allowances paid throughout childhood are positively associated with higher TFRs, but their effect is only weakly significant.

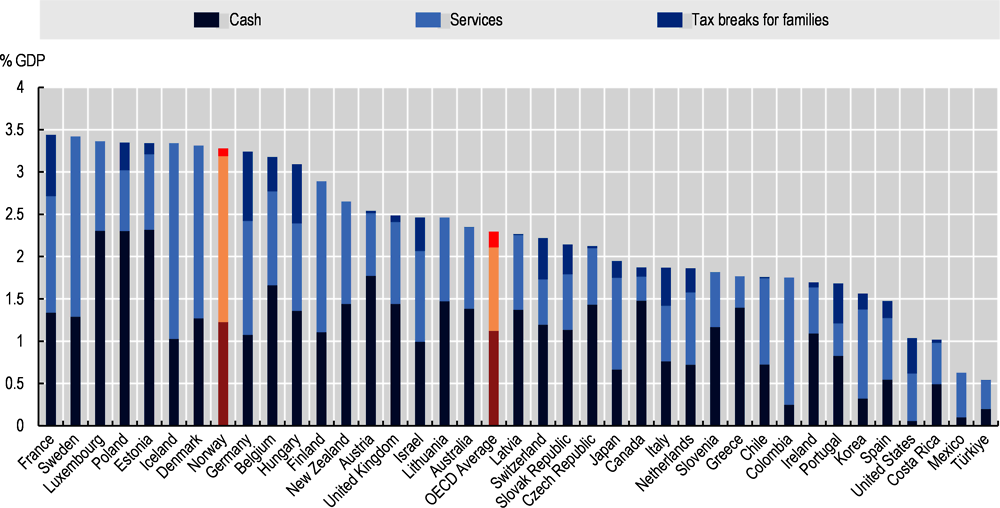

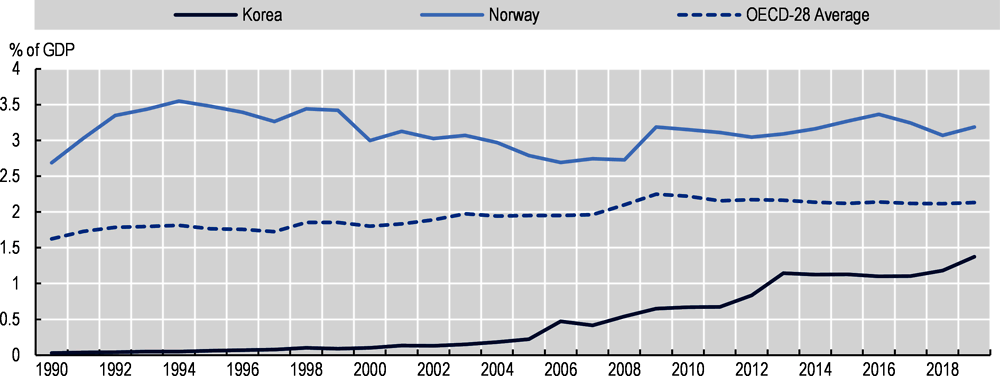

Together with its Scandinavian neighbours, Norway defines the Nordic model of family and gender-equality policy with wide-ranging public family supports for parents of young children. At about 3.3% of annual GDP in 2019, public spending on family benefits is Norway is among the highest in the OECD (Figure 3.1). However, Norwegian family policy is not necessarily driven by explicit aims around the increasing of birth rates. Instead, the primary motivation for extensive family policy support in Norway is supporting the reconciliation of work and family responsibilities of both parents and ensuring economic and social conditions that enhance the development of children over the early life-course and contributes to the overall well-being of families and children (OECD, 2018[1]; Lappegård, 2009[2]; Esping-Andersen, 1999[3]).

Across the OECD, different emphases on underlying family policy objectives lead to differences in the design of family policy across countries. In some countries with elements of “pro-natalist” family policies – a proportional increase in cash and/or fiscal supports for families with 3 or more children, like Hungary (Box 3.1), families are also provided with financial support through universal cash benefits and tax breaks that are designed to facilitate one parent – often the mother – to care for children at home up to the third birthday.

In Norway, the aim of full labour market participation by fathers and mothers is facilitated through services and supports that promote the combination of work- and family responsibilities, including paid parental leave. Norway also recognises the right of fathers regarding their children and of children regarding their fathers and aims to facilitate a central role for both fathers and mothers in the household and the care for children (Ministry of Children and Families, 2017[4]). Upon expiry of paid leave, families have access to the system of family services, including an extensive Norwegian ECEC system.

Trust in the family policy system is high among the Norwegian population, with robust expectations regarding the stability of its generous support provisions. A large portion of the population is also highly supportive of policy interventions that support gender equality at home and in the labour market. As such, Norwegian family policy provides low barriers to parenthood (Ellingsæter and Pedersen, 2015[5]; Jakobsson and Kotsadam, 2010[6]).

Following low fertility rates since the early 2000s, Hungary has adapted a decidedly pro-natalist stance with wide-ranging family supports aimed at stimulating fertility, particularly higher-parity births. This has culminated in one of the highest expenditures on public family benefits across the OECD (3.09% of GDP in 2019) and appears to have stabilised falling fertility. The policy approach includes:

Infant care (CSED) and childcare fee (GYED): Parental leave benefits for parents paid until the child’s third birthday. Insured parents, receive two years of an earnings-related parental-leave benefit (GYED) followed by one year of a flat-rate benefit (GYES). GYED is paid up to a limit of HUF 234 360 (USD 584). GYED, which is also available for uninsured parents for three years, is a flat-rate benefit of HUF 28 500 (USD 71) – far less generous than GYED.

Family allowance (családi pótlék): A non-contributory, non-means-tested cash benefit available to all families, with payment dependent on family size. In 2022, parents with one child receive 12 200 HUF (USD 30.41) per child/month, while those with three or more children receive 16 000 HUF (USD 39.88) per child/month.

Housing benefit (CSOK): A benefit for the purchase or construction of housing dependent on the number of (planned) children in the family. It consists of a non-refundable subsidy ranging HUF 600 000 (USD 1 495) in the case of one (planned) child to HUF 10 million (USD 24 923) for three or more (planned) children. Families with two or more (planned) children are also eligible for an additional loan with reduced interest rates.

Tax base allowance (családi kedvezmény): A per-child non-refundable allowance deductible from taxable income, also increasing with family size. In 2022, families with one child receive a discount of HUF 66 670 (USD 166) on their tax base, while families with three children receive a discount of HUF 660 000 (USD 1 645). Through NÉTAK, mothers who have had four or more children are fully exempt from personal tax on work-related income.

Such strong family supports seem to have stopped the downward trend in fertility rates, but at substantial fiscal cost without countering the ongoing population declines. Among the various measures, grants towards homeownership seem to have had the biggest upward effect on birth rates (Szántó, 2021[7]; Szabo-Morvai, 2019[8]).

Source: Albert (2020[9]), OECD (2022[10]).

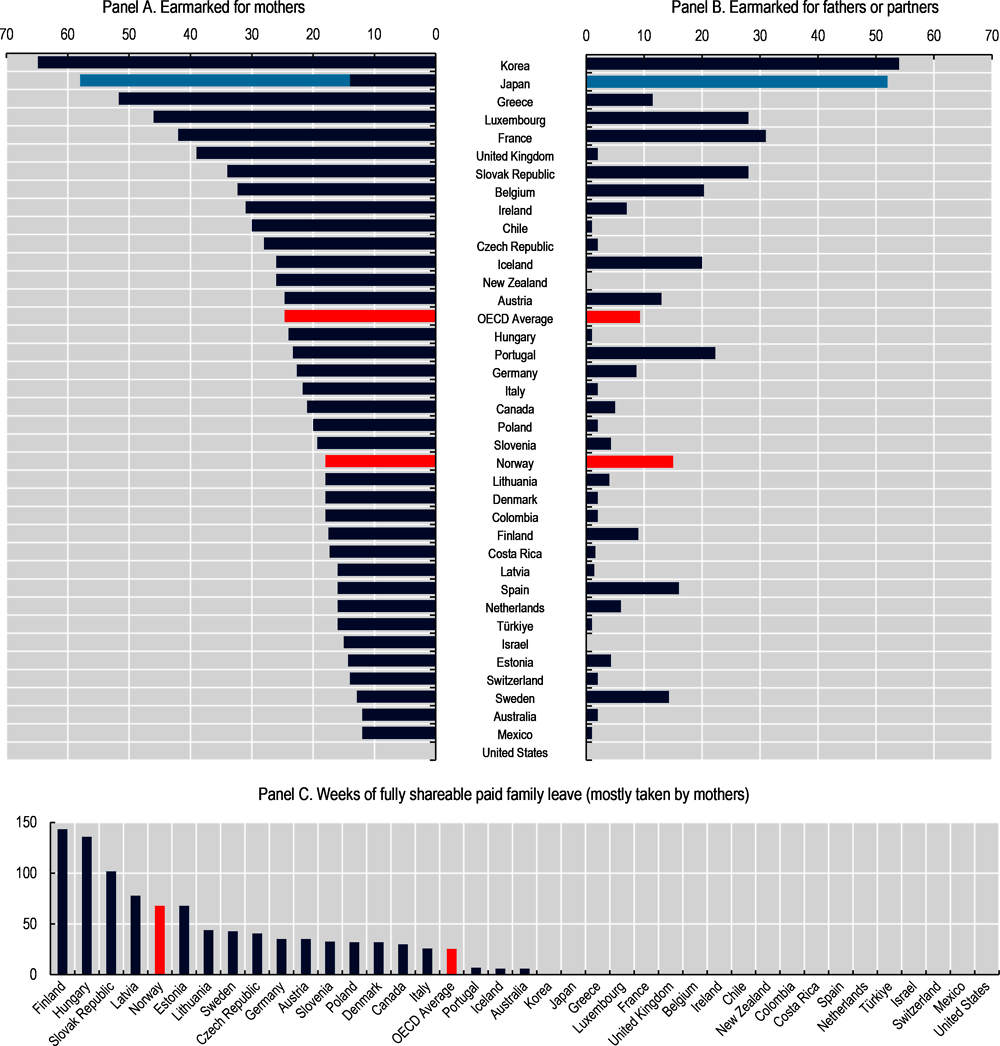

Through its paid parental leave (foreldrepengeperioden), Norway grants parents relatively well-paid employment-protected family leave entitlements of considerable length, made up of separate individual entitlements for fathers and mothers along with a shareable part of the parental leave period (the design of parental leave is a topic of considerable debate in Norway (Ellingsæter, 2020[11]) as elsewhere). Norway does not have a separate maternity leave entitlement, but like, for example, Iceland, Portugal and Sweden, it offers paid parental leave reserved for the exclusive use of the mother (Figure 3.2). This so-called maternal quota (mødrekvoten) grants three weeks of paid job-protected leave before birth and either 15 weeks (the “normal option”) or 19 weeks following birth (the “long option”). For health reasons, it is mandatory for mothers to take at least 6 weeks of leave following birth, while any kind of paid parental leave entitlement can be taken up to child’s third birthday after this period. In addition to paid parental leave, mothers who breastfeed are also entitled to a breastfeeding break from work of up to one hour per day for children under one year old, fully paid by their employer (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]).

Similar to maternity leave, there is no separate paid paternity leave programme, but fathers have the right to 2 weeks of unpaid, job-protected “daddy-days” (omsorgspermisjonen) after the birth of their child. Many fathers receive employer-provided paid leave benefits as agreed through collective or individual bargaining, but payment rates vary. Instead of statutory paternity leave, fathers – or same-sex partners – are entitled to the paternal quota (fedrekvoten) in parental leave, which offers the same post-birth right to paid parental leave as mothers (i.e. 15 or 19 weeks), and is subject to the same eligibility criteria. When it introduced this entitlement in 1993, initially for 4 weeks, Norway was the first country worldwide to offer fathers a non-transferable right to parental leave (Haas and Rostgaard, 2011[13]).

Parents are further entitled to a fully shareable period of paid parental leave (fellesperioden), which can last either 16 weeks under the normal option or for 18 weeks under the long option and can be shared by fathers and mothers (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]). In 2021, about 79% of parents used the long option, which is an increase by more than 20 percentage points compared to 2012 (Arbeids- og velferdsetaten, 2021[14]). After the first 6 weeks of leave, all parental leave can be used on a part-time basis combined with part-time employment (with agreement of the employer) or divided into smaller blocks of time (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]).

The maternal and paternal quota, as well as the shareable period of paid parental leave, grants a total of 49 weeks of a parental benefit (foreldrepenge) at 100% of previous earnings, capped at 6 times the national insurance scheme basic amount1 (NOK 55 740 or USD 5 636 in 2022), for the normal option (about as much as average gross monthly earnings). In practice, many collective or individual agreements cover the difference between the cap and full replacement of previous income, including in the public sector. The “long option” grants a total of 59 weeks of parental benefit at 80% of previous earnings and is capped at the same monthly threshold as the normal option. The parental benefit is the same during the maternal and paternal quota as well as the shareable period, and only differs by the chosen duration (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]). Overall, the compensation during parental leave is relatively high in comparison to many other OECD countries (OECD Family Database). In addition to the parental benefit, both parents have the right to a full year of unpaid leave after their entitlement to paid parental leave ends (ulønnet permisjon), up to the child’s third birthday.

In comparison to other OECD countries, the Norwegian parental leave system stands out in terms of the length of shareable leave entitlements and those reserved for the exclusive use of fathers, while earmarked entitlements for mothers are shorter than elsewhere. Across the OECD, for example, mothers receive 25 weeks of reserved maternity and paid parented leave on average, which is 7 weeks longer than what the maternal quota offers under the normal option (Figure 3.2, Panel A). However, Norway’s paternal quota is almost twice as long as the average paternity and paid parental leave reserved for fathers across the OECD (Figure 3.2, Panel B), while the shareable paid parental and home care leave under the normal and highest-paid option is more than twice as long as on average across the OECD (Figure 3.2, Panel C).

Compared to other Nordic countries, Norway has longer overall entitlements to paid parental leave for fathers and mothers than in Iceland and Sweden (Denmark introduced 11 weeks of leave earmarked for fathers in August 2022). However, the duration of total entitlements is not as long as in Finland, where paid home-care leave can be taken until the child turns 3. Despite the comparatively long parental leave in Norway, previous reforms in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s that led to this entitlement have not had an effect on women’s likelihood to make it to the top in companies, and no impact on gender gaps in hours and pay (Corekcioglu, Francesconi and Kunze, 2022[15]).

3.3.1. Fathers have stricter eligibility requirements for parental leave taking than mothers

The general eligibility criteria for the maternal and paternal quota are the same – either parent must have been in employment for 6 of the last 10 months before expected birth while having earned at least half the national insurance scheme basic amount the previous year (NOK 54 892 or USD 5 550 in 2022). Mothers that do not fulfil the general eligibility criteria are entitled to a tax-free one-off payment at birth (NOK 90 300 or USD 9 403 in 2022), which concerns about a fifth of all mothers, mostly those with births at younger ages and those with a migration background (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]; Hasane, 2020[16]).

However, there are some differences regarding eligibility when it comes to the employment status of mothers’ and fathers’ partner. Fathers can only use their quota if the mother is also eligible for parental benefits, while for mothers there is no requirement on their partner’s eligibility status. Similarly, mothers can take the shareable paid parental leave period without any requirements on their partner’s employment status, but fathers can only use the shareable period of paid parental leave if the mother takes up work or studies at a minimum of 75% of full-time hours (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]). Therefore, about 13% of all fathers are not eligible for parental benefits (Kitterød, Halrynjo and Østbakken, 2017[17]). These differences in eligibility criteria for fathers and mothers, are justified with reference to the notion that leave taking by fathers can only improve the division of paid and unpaid work between both parents if fathers are at home on leave while mothers are at work (or study) at the same time (Norwegian Ministry of Children and Equality, 2016[18]).

Norway could align the eligibility criteria for parental leave for fathers and mothers, with potentially positive effects on paternal leave-taking, and the division of childcare among parents.2

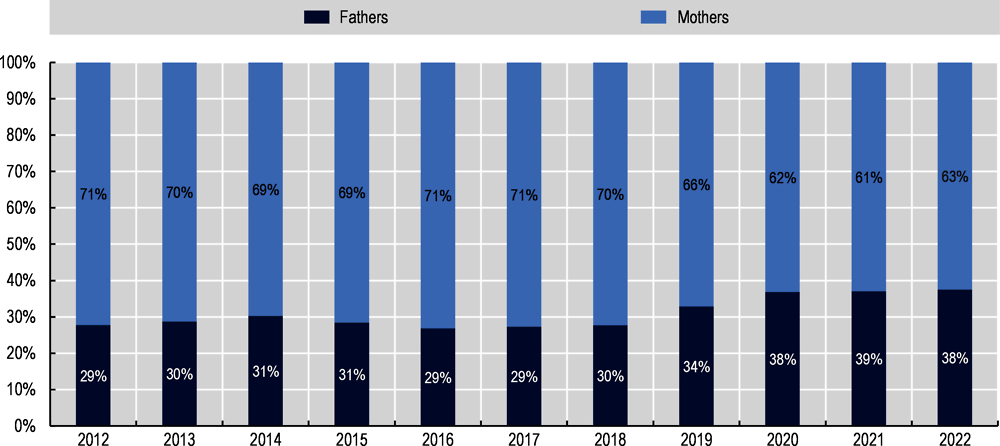

3.3.2. Many fathers take leave, with positive effects for the whole family

Since the introduction of the paternal quota in 1993, Norwegian fathers have substantially increased their use of leave, but their usage is highly dependent on the length of their quota (Kvande, 2022[19]). For example, fathers took out almost 38% of leave days in 2022, which is reasonably close to the share of parental leave entitlements that is reserved for them. Indeed, as 90% of fathers took parental leave, 70% did so for precisely the length of the paternal quota (Shou, 2017[20]; Rudlende and Bryghaug, 2017[21]; Kitterød, Halrynjo and Østbakken, 2017[17]). Recent changes in the paternal quota also had a direct impact on the distribution of leave taken. For example, after several reforms that increased the quota over the years, it was reduced from 14 weeks to 10 weeks in July 2014, which led to a decrease in fathers’ share of leave taken in the following years. An increase to 15 weeks in July 2018 (under the normal option) led to a subsequent rise in the share of leave days taken by fathers (Figure 3.3).

There is scope to scope to encourage more equal sharing of leave entitlements among parents in Norway. For example, the shareable part of paid parental leave could be phased out over time, by simultaneously increasing both the paternal and maternal quota by a transferable right that eventually reaches additional 9 weeks of leave (under the normal option). This would keep the non-transferrable right for both parents at the same level and still allow for a similar division of leave as today but may create a new default norm of equal leave taking for fathers and mothers.

Such a system where each parent gets the same amount of allocated paid leave entitlement is, for example, in place in Iceland, where 6 months of paid leave are reserved for fathers and mothers each, with 6 weeks of the individual entitlement transferable to the partner (Eydal and Gíslason, 2021[22]). Finland recently also introduced similar individual entitlements with a transferable portion. Since September 2022, both parents are entitled to 6.4 months of leave, of which 2.5 months can be transferred to the other partner (Finnish Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, 2022[23]).

Periods of parental leave that are reserved for fathers have shown to be an important contributor to family well-being and the ability to combine household and care responsibilities with careers on the labour market. For example, international evidence suggests that fathers’ leave taking can increase the relative income of mothers and lead to a more equal division of unpaid house- and care work in couple households an effect which persists well beyond the years of actual leave-taking (Patnaik, 2019[24]; Tamm, 2019[25]; Druedahl, Ejrnæs and Jørgensen, 2019[26]; Knoester, Petts and Pragg, 2019[27]). This increased involvement additionally improves the communication and closeness between children and fathers (Petts, Knoester and Waldfogel, 2019[28]). Recent evidence suggests that the availability of reserved leave for fathers increases the overall life satisfaction for both parents, but particularly for mothers (Korsgren and van Lent, 2022[29]). At the same time, Norwegian employers generally have a favourable view of the paternal quota (Brandth and Kvande, 2019[30]). However, there is little evidence on whether employers are supportive of fathers that take leave beyond the paternal quota. Such support would be essential to reduce the remaining discrepancies in leave uptake and the time dedicated to childcare and unpaid work in the household in general, as well as to eradicate the disproportionate earnings and employment penalties that mothers face relative to fathers once becoming a parent (for example, Kleven et al. (2019[31])).

There is mixed evidence on the effect of leave use among fathers in Norway on fertility rates (Duvander et al., 2019[32]; Duvander, Lappegård and Andersson, 2010[33]; Bergsvik, Fauske and Hart, 2020[34]; Duvander, Lappegard and Johansson, 2020[35]). However, a more equal division of paid- and unpaid work could dampen the worries over negative effects of births on career and leisure, which is already one of the biggest concerns among childless Norwegians (Cools and Strøm, 2020[36]) (more on the link between parental leave and fertility in Section 3.7.3).

If their child is not attending publicly funded ECEC services, parents with a child between the age of 1 and 2 can receive a “cash-for-care” benefit (kontantstøtte). Norway introduced the benefit scheme in 1998 – prior to a large-scale expansion of the ECEC sector (see more in Section 3.5 below) – intending to give parents the freedom of choice between kindergarten and spending more time with their children, while also supporting those unable to find a kindergarten spot. The benefit initially paid NOK 3 000 (USD 304) per month to parents of children aged one not attending kindergarten but was temporarily extended to those aged 1 or 2 in 1999 and 2012. Today, parents of children aged 1 who do not attend kindergarten can receive NOK 7 500 (USD 758) per month, which is substantially lower than the parental leave benefit. The cash-for-care benefit is paid up to and including the month the child starts kindergarten and can also be paid at reduced amounts for part-time kindergarten attendance (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]; Bungum and Kvande, 2013[37]).

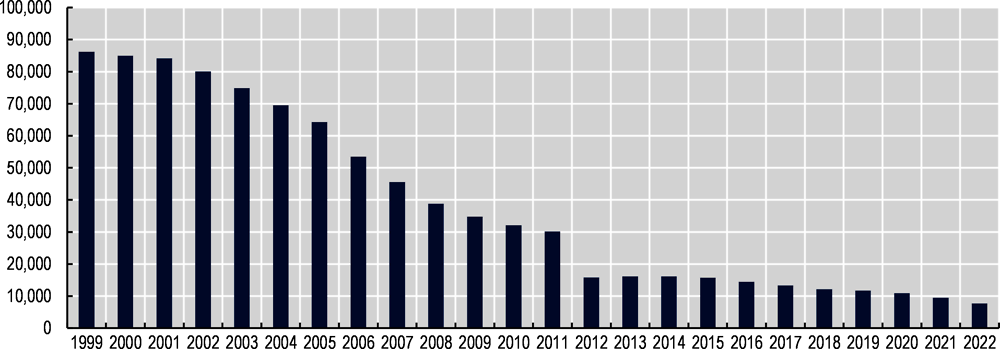

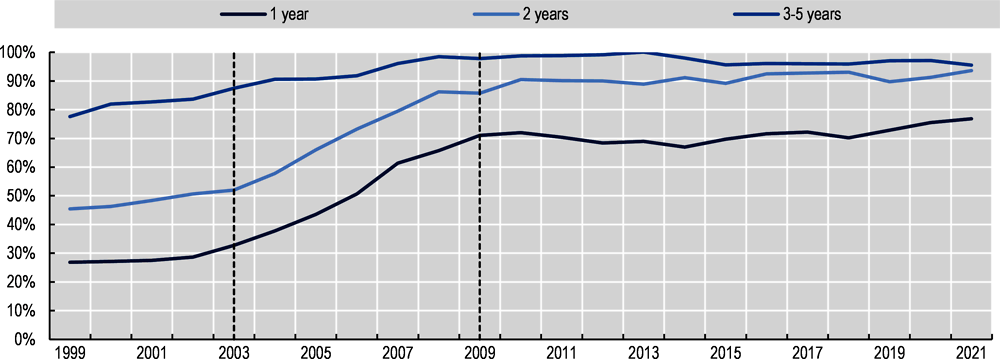

The cash-for-care benefit has been subject to much public and political debate over the last two decades. While the benefit was initially popular, used by 91% of all eligible parents, it has since lost much of its appeal following the expansion of the ECEC sector since 2003, so that in 2022 only about 15% of all eligible parents received it (Figure 3.4). Evolving from being an alternative to ECEC for children, today the cash-for-care benefit is mainly used to cover the potential gap between the end of paid parental leave and entering kindergarten (Bungum and Kvande, 2021[12]; 2013[37]).

In terms of fertility rates, it has been found that the cash-for-care benefit slowed the progression to second births and decreased births among employed mothers with upper secondary education (a more detailed discussion on the link between fertility and cash benefits can be found in Section 3.7). This may be explained by interactions of the cash-for-care benefit scheme with the Norwegian parental leave framework, as mothers first have to return to work for a minimum of six months before becoming eligible again to parental leave (Andersen, Drange and Lappegård, 2018[38]).

Ever since its introduction, the cash-for-care benefit has been seen as an obstacle to gender equality and has thus been heavily debated in Norway. One main criticism concerned its initial effect on the relative price between public childcare and care at home, which contributed to a decline of female labour force participation when the benefit was introduced. This effect was particularly strong for low-income workers, including many non-western immigrant mothers – a 5-year residency requirement was introduced in July 2017 (Arntsen, Lima and Rudlende, 2019[39]; Hardoy and Schøne, 2010[40]). Similar effects on female labour force participation have been observed following the introduction of a substantial child benefit in Poland (Box 3.2).

The post-1989 economic transition of Poland, contributed to a drop in the TFR to around 1.2 children per women in the early 2000s. To counter this trend and to reduce future demographic pressures, Poland introduced a range of policies aimed at making it easier for families to have children, resulting in public spending on family benefits increasing to 3.35% of GDP in 2019, well above the OECD-average of 2.29% of GDP. The system comprises a range of policies, in part explicitly incentivizing higher-parity births:

Parental leave (urlop rodzicielski): A family entitlement to 32 weeks of parental leave, paid at different replacement rates between 60 and 100% of previous earnings.

Basic family allowance (Zasiłek rodzinny): A child benefit of between PLN 95 (USD 20) to PLN 135 (USD 29) per child, dependent on the age of the child and paid for children up to the age of 24.

500+ programme (Rodzina 500+): A tax-free benefit paying PLN 500 (USD 106) for each child up to the age of 18. Initially only paid for all second births and above, it was extended to cover all families in 2019.

Supplementary family allowance (dodatek z tytułu wychowywania dziecka w rodzinie wielodzietnej): A supplement of PLN 95 (USD 20) paid for the third and subsequent children entitled to family allowance.

Despite spending large sums on family benefits, this did not lead to a major increase in birth-rates. For example, the tax-free cash benefit for all second births and above offered through the Polish 500+ programme from 2016, has led to marginally increasing births in the year after its introduction. However, since 2017, the Polish TFR has not increased. At the same time, the reform has reduced financial incentives to work for mothers with young children, particularly those with limited earnings. With negative effects on maternal labour supply, the reform may therefore limit gender equality in the labour market and reduce the tax base of the Polish economy (Magda, Kiełczewska and Brandt, 2020[41]; Bargu and Morgandi, 2018[42]).

Poland has recently launched a new Demographic Strategy 2040, which aims to lift TFRs closer to replacement level. This strategy is focused on three goals: strengthening the family, removing barriers for parents wishing to have children and improving the quality of governance and implementation of policies. Whether it will be effective in lifting the TFR remains to be seen, yet a return to replacement level fertility is unlikely.

Source: Bargu and Morgandi (2018[42]), Magda, Kiełczewska and Brandt (2020[41]), Hoorens et al. (2011[43]), Ekert (2022[44]), Ministry of Family and Social Policy (2022[45]).

Since 1 August 2022, the cash-for-care benefit is no longer granted in the month the child starts kindergarten. This new policy is estimated to reduce public expenditure by about NOK 102 million (USD 10.31 million) in 2022 and NOK 152 million (USD 15.37 million) in 2023. In addition, the government is considering a replacement of the cash benefit for children between 18 and 24 months with a toddler benefit (småbarnstøtte), paid only to those who have applied for, but not received, a kindergarten place (Finansdepartementet, 2021[46]).

France has long-standing pro-natalist elements in its policy framework, i.e. the “code de la famille”, first launched in 1939 amid worries of population decline, and still in place in updated form today. The system includes parental leave and parental allowance policies, subsidised childcare and other measures to encourage high labour market participation of both mothers and fathers. Some policies in France, however, explicitly incentivise families to have more than two children (famille nombreuse). As a result of this comprehensive family policy framework, France had the largest expenditure on family benefits in the OECD, amounting to 3.44% of GDP in 2019. While, in recent years, policy focus has shifted more and more toward ECEC provision to help parents balance work and family life, France nevertheless continues to incentivise higher-order births through a range of family benefits:

Childcare allowance (PreParE): Parents of a single child receive six months of childcare allowances per parent during parental leave, payable at between EUR 149 and EUR 398 per month, depending on income and employment situation. Parents with two or more dependent children under the age of 20 can receive the childcare allowance for a total of 36 months, with a maximum of 24 months to any one parent. Lower income families also receive a supplementary early childhood allowance (Allocation de base, PAJE) of up to EUR 171.

Family allowance (allocation familiale): Parents with two or more dependent children under the age of 20 can receive a means-tested family allowance, which increases with the number of children and is further increased for each child over the age of 14 years (for two children only for the eldest). Depending on household income and age of the children, a family with 3 children can for example receive between EUR 80 and EUR 530 in monthly benefits.

Supplementary family allowance (complément familial): Parents with at least 3 children above the age of 3 also receive a means-tested supplementary family allowance between EUR 182 and EUR 273 per month.

Family quotient (quotient familial): The net taxable income of a married household (or those in registered partnerships) is divided by a certain number of tax shares that depend on the size of the family. Joint households without children divide their net taxable income by 2, whereas those with 1 child do so by 2.5 and those with 2 children by 3, while families with 3 or more children receive one additional tax share per child.

France has one of the highest fertility rates in the European Union and the OECD. While there is a lack of comprehensive studies that measure the casual effect of family policy on fertility rates in France, it seems to have created favourable sentiments toward families with two or three children and a decreased likelihood to stay childless (Thevenon, 2010[47]). Overall, financially incentives for childbirth seem to have contributed to sustaining birth rates (Laroque and Salanié, 2013[48]). Recent evidence also suggests that the supplementary childhood allowance contributes to earlier childbirth, so that a restriction of eligibility criteria for the supplementary early childhood allowance (PAJE) exerted a downward effect on the TFR, part of which may be due postponement of births (El-Mallakh, 2021[49]).

Source: Thévenon (2010[47]), Boyer and Fagnani (2021[50]), République Française (2021[51]).

In addition to parental leave and cash-for-care benefits, Norway also pays a monthly child benefit until the child turns 18 (Barnetrygd). The child benefit can be paid either to the father or mother or split equally between them if they live together. It amounts to NOK 1 676 (USD 169) per child for under 6-year-olds and NOK 1 054 (USD 107) per child for over 6-year-olds. Parents with sole custody of their children may also be entitled to an extended child benefit (utvidet barnetrygd) of an additional NOK 1 054 (USD 107). While the Norwegian cash benefit system is comprehensive, it does not directly incentivise higher-parity births, such as the French family benefit system (Box 3.3).

After the entitlement to paid parental leave runs out, employed parents can use ECEC services for their children, to help them combine a return to full- or part-time work with the child’s need for care. Under the Kindergarten Framework Plan, Norwegian kindergartens aim to address children’s need for care, play and development, while also promoting learning, community, and communication (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2017[52]). The availability of ECEC services has important positive links to fertility (Section 3.7), especially on higher order births, while the affordability of these services appears to have positive links to first births (Bergsvik, Fauske and Hart, 2020[34]).

3.5.1. Many children attend kindergarten from the age of one

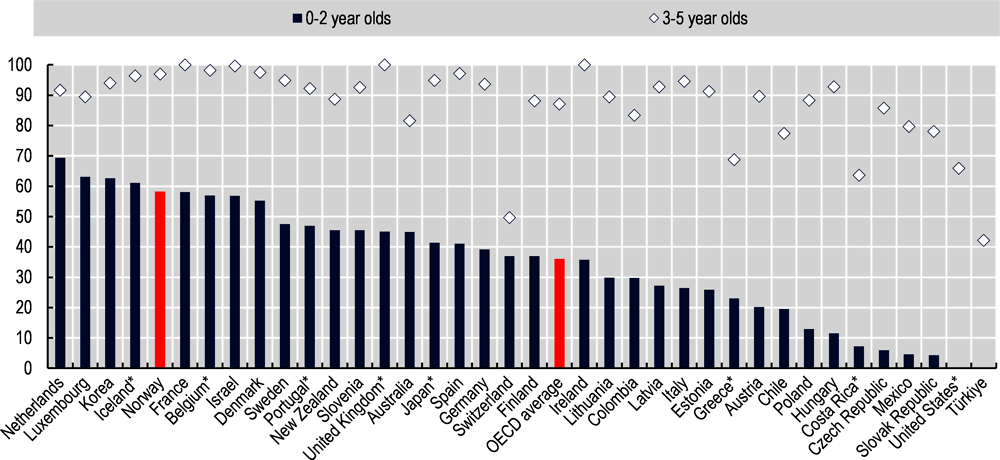

In contrast to many other OECD countries, Norwegian ECEC is a unitary system in which a single entity, the kindergarten (barnehage), provides predominately centre-based childcare services to children from age zero up to school start in the year they turn six.3 Kindergartens usually operate for 9 to 10 hours a day between Mondays to Fridays, while children can attend full- or part-time. Kindergarten attendance is not compulsory, but a combination of wide-spread availability and comparatively low prices ensure high attendance rates, which is among the largest in the OECD for under 3-year-olds and almost universal among 3 to 5-year-olds (Figure 3.5) (Trætteberg et al. (2021[53]), OECD Family Database).

In 2021, roughly similar numbers of children attended private (49.7%) and municipal or other public (50.3%) kindergarten (Statistics Norway, 2023[54]). Both types of kindergarten receive similar funding, with more financing for younger children, which require a lower child-to-staff ratio than the older ones. Municipal funding covers about 80% of the running costs, with the remainder financed by parental fees and a small part contributed by earmarked government subsidies and other grants from municipalities and centre owners (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2021[55]; Trætteberg et al., 2021[53]).

The staff in Norwegian kindergarten consists of about 40% qualified kindergarten teachers and 20% childcare and youth workers, while the rest is made up of other professions. Regulations require that there is a minimum of one core staff member for every 3 children under the age of 3 and one for every 6 children over the age of 3. For the latter, there also needs to be at least one qualified kindergarten teacher for every 14 children. There is a slightly larger staff density in public (5.7 children per staff member) than in private (6.0 children per staff member) kindergartens (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2021[55]; Trætteberg et al., 2021[53]).

The high attendance rate in Norwegian kindergarten, especially for children aged 1-2 years, is a result of a broad political consensus that led to significant changes to the financial and legal framework of the ECEC sector in 2003. To meet the growing demand and consolidate the sector, the so-called Kindergarten Agreement (Barnehageforliket) substantially increased access and affordability of the ECEC in Norway. Previously, demand for kindergarten places far exceeded supply, while childcare fees varied considerably and were especially expensive in private kindergarten. Many families had to rely on alternative childcare solutions, such as childminders or the help of family members, and kindergarten enrolment rates for the youngest children were low (Figure 3.6) (Trætteberg et al., 2021[53]; Norwegian Ministry of Children and Family Affairs, 2015[56]).

With the Kindergarten Agreement, municipalities received increased financing for the sector, which tripled state funding between 2003 and 2011, so that universal provision of kindergarten places under reduced parental fees was made possible – the parental fees were capped at a specified maximum. At the same time, municipalities were obliged to provide per-child funding for private kindergarten, which were made subject to the same regulated parental fees. The agreement also introduced an individual statutory right to a kindergarten place for all children aged 1-5, which came into effect in 2009. Initially, it granted the right to a kindergarten place from August to all children turning one before September of the same year. However, this right has since been extended with amendments to the Kindergarten Act in 2016 and 2017. Since then, those turning one between September and November have such a right by the end of their birthday month, while children turning one in December still have to wait until the following August to enter kindergarten (see below) (Trætteberg et al., 2021[53]; OECD, 2015[57]).

Following the Kindergarten Agreement, the supply of kindergarten spaces critically increased since 2003. Overall, the expansion mainly increased the enrolment of children in kindergarten (+46% between 2000 and 2010), while the number of kindergarten centres grew much more muted over the same period (+13%) (Statistics Norway, 2023[54]). Especially for the youngest children enrolment rates increased substantially between 2003 and 2009, when the statutory right for a kindergarten place came into effect. For example, while in 2002 about 29% of children aged 1 were enrolled in a kindergarten, about 71% were so in 2009 (Figure 3.6).

The increased access to high-quality and affordable childcare and the expansion of the ECEC sector in Norway has not only increased the involvement of fathers in childcare – noticeable reduction in the inequality of paid and unpaid workloads between fathers and mothers – it has also positively influenced fertility (Rindfuss et al., 2007[58]; Kitterød and Rønsen, 2017[59]). For example, it has led to a younger age it first birth, while also substantially increasing fertility across all birth parities. Estimates of Rindfuss et al. (2010[60]) even suggest that going from zero available kindergarten places to affordable childcare slots for 60% of pre-school children increases the TFR of an average woman by between 0.5 and 0.7. Such positive effects of affordable ECEC provision are also found in some other countries (Section 3.7), but in Korea – where spending on the ECEC sector increased more than tenfold between 2000 and 2014 – it has not been able to reverse strong downward trends in fertility (Box 3.4).

Over the past six decades, Korea has experienced a sharp decline in birth rates. After crossing below a total fertility rate (TFR) of 1.5 in the early 2000s, Korea recorded the lowest TFR among all OECD countries today (0.81 in 2021). This contributes to Korea being the fastest ageing OECD country, with a dramatic increase in median age from 43 in 2018 to 56 in 2050.

To respond to declining fertility rates and an ageing population, Korea has rapidly expanded their expenditure on public family support – predominantly in-kind, since the early 2000s. The most significant approach was the development of a comprehensive system of public and private formal day-care and kindergarten support for young children. ECEC attendance in Korea is now on par with the Norway and other Nordic countries (Figure 3.5). Other key family policy developments include the introduction of an individual entitlement to paid parental leave in 2008. Today, eligible parents can take up to 12 months paid parental leave each until the child’s eighth birthday (or until they enter the second year of primary education) – the payment rate is earnings-related.

As a result of the expansion of Korean family supports, public expenditure on family benefits increased more than tenfold between 2000 and 2014, from approximately 0.1% to about 1.1% of Korean GDP (Figure 3.8), most of which is spent on the ECEC sector. While this is lower than in Norway and the OECD on average, it marks an important shift in Korean family policy.

Despite this massive expansion of ECEC and family supports in general, Korea has not been able to reverse its downward trend in birth rates. Part of this may be explained by the difficulties to reconcile work and family life, for example, because very long working hours. Other potential factors include changing societal norms and notions on gender roles, labour market dualism and the large number of parents that are reluctant to use or are ineligible for paid leave around childbirth, as well as the relatively high cost in Korea of raising children in cash and time – as related to private education.

Source: OECD (2019[61]; 2019[62]), Kostat (Kostat, 2022[63]).

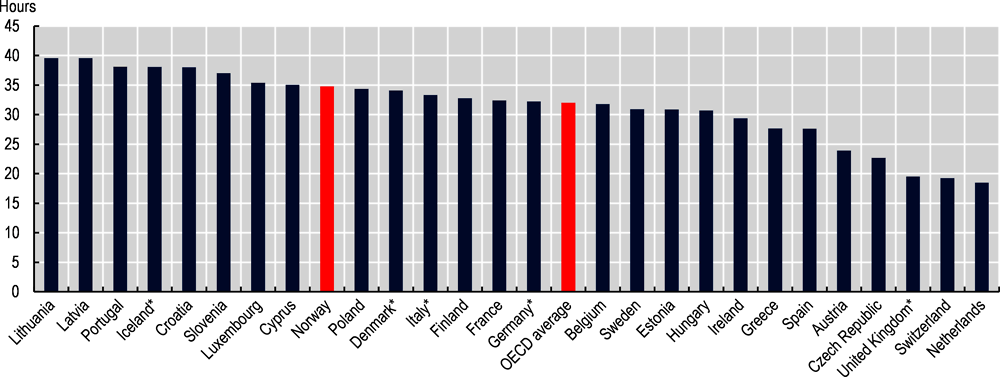

Compared most other OECD countries, Norwegian children attend kindergarten for long hours. While the OECD average weekly hours in ECEC services was 30.6 hours for children aged zero to two in 2019, Norwegian children of this age group attended kindergarten for an average of 34.6 hours (

Figure 3.7). This is facilitated by the long opening hours of kindergarten in Norway, which typically operate for 10 hours between 7:00 or 7:30 and 17:00 or 17:30. A low and decreasing number of Norwegian children at all kindergarten ages are also enrolled on a part-time basis, especially when their mother has some flexible working arrangements and the number of siblings is low (Moafi, 2017[64]).

3.5.2. Childcare is affordable

Besides the expansion of childcare places, the Kindergarten Agreement also set a maximum price for kindergarten attendance, regardless of whether children attend public or private facilities. As of 1 August 2022, the maximum fee is set at NOK 3 050 (USD 308) to reach the original price level set at the time of the Kindergarten Agreement in 2003. Kindergartens can require a payment for meals, which varies across municipalities and is currently set at NOK 190 (USD 19.21) per month in Oslo, for example (Government of Norway, 2021[65]).

A variety of discounts on the kindergarten fees are granted depending on parents’ income level. For example, since 2015, childcare fees are capped at a maximum of 6% of gross household income. If parents have more than one child attending kindergarten in the same municipality (not necessarily the same kindergarten), they receive a reduction in kindergarten fees (søskenmoderasjon) of a minimum of 30% for the second child and a minimum 50% reduction for any additional child. Families earning less than NOK 583 650 (USD 59 011) are entitled to 20 hours of free “core time” (kjernetid) in kindergartens for their children aged between 2 and 5 years old (Government of Norway, 2021[65]). Single parents can receive an additional benefit for formal centre-based care (stønad til barnetilsyn) that covers up to 64 percent of the expenses for childcare up to a maximum ceiling that depends on the number of children in childcare (Arbeids- og velferdsetaten, 2022[66]).

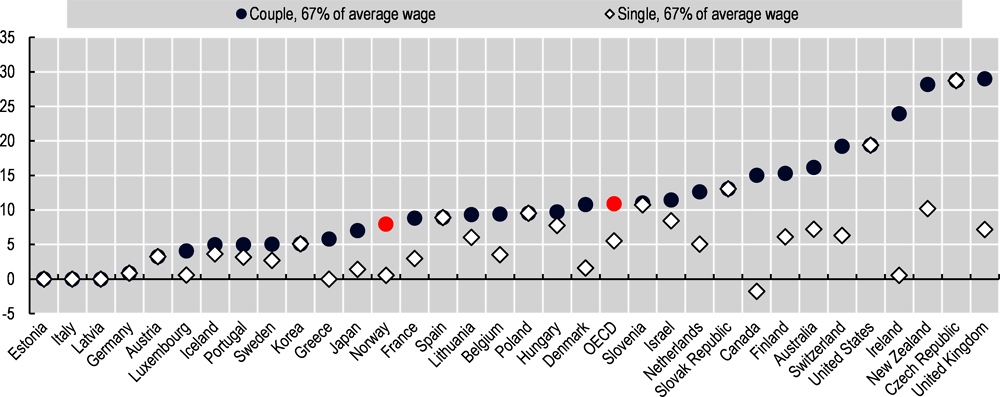

The cap on fees and other discount schemes have helped to keep the costs of participation in ECEC down to parents. In Norway, out-of-pocket childcare costs for a family with two children with two low-wage earners is only 8% of the average wage (where low-wage refers to earning two-thirds of the average wage). This figure can be compared with the slightly higher out-of-pocket cost of 11% of average wage on average OECD-wide. For a single parent low-wage earner with two children, the out-of-pocket cost is 1% of average wage in Norway and 6% on average across the OECD (Figure 3.9) (OECD, 2020[67]).

Support for ECEC expenses have helped many families financially. The supports themselves are estimated to have led to a 4% increase in disposable income for low-income families through the 6% cap on parental fees, while the free core time has resulted in a 7% increase in disposable income for these families. However, not everyone entitled to discounts on the fees for kindergarten attendance receives a discount. While the number of families receiving discounts is increasing over time, many of families who are entitled are not reached (Østbakken, 2019[68]). For example, in 2017, only about 60% of the children who are entitled to free core time received the relevant fee-reduction. Such “non-claims” of discounts may be the result of complicated application procedures and documentation requirements, particularly for recent immigrants to Norway (Trætteberg and Lidén, 2018[69]; Østbakken, 2019[68]). A recent simplification and streamlining of the process could make it easier for families to claim the discounts, as since August 2022, municipalities can directly collect information about the parent’s income from the tax authorities, rather than requiring documentation from the parents themselves (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2022[70]).

Overall, the expansion of the ECEC sector, with the statutory right to a kindergarten place and the regulation of kindergarten fees, has led to improved attendance – children from low-income families in particular increased their enrolment rates disproportionately since 2003 (Dearing et al., 2018[71]; Ellingsæter, Kitterød and Lyngstad, 2016[72]). An earlier expansion of subsidised childcare in 1975, granting ECEC eligibility to all 3-6 year-olds independent of their parents employment and marital status, also contributed to increased earnings among children of low-income parents in the long-term and increased intergenerational income mobility (Havnes and Mogstad, 2015[73]). The availability of discounts on the kindergarten fees also had a positive impact on subsequent school performance. For example, free core time (see above) was introduced in Oslo in 2006, and children who received it improved their reading performance by grade 8, with stronger effects for boys and in families with low incomes or mothers outside of the labour force (Drange, 2021[74]). Altogether, the wide-scale reforms of the ECEC sector have changed the attitudes of Norwegian parents, so that the majority now considers it the best care children can receive from as early as between age 1 and 2 (Ellingsæter, Kitterød and Lyngstad, 2016[72]).

3.5.3. Kindergarten age thresholds leave some in need for alternative care

Because of the age-threshold for kindergarten eligibility, some families are left without a kindergarten place once their entitlement to paid parental leave ends. Children who turn one between January and July are entitled to a kindergarten place in August of that year and those who turn one between August and November have a statutory right to a place in the month they turn one. However, children who turn one in December have to wait until the following August. This has raised some concerns regarding equal opportunities and child development, as it is argued that delayed childcare enrolment for the youngest can impact language- and mathematics performance at age 6-7, particularly for children from disadvantaged families (Drange and Havnes, 2019[75]; Drange, 2019[76]).

Families with a gap between paid parental leave entitlement and the right to a kindergarten place have to find alternative solutions, for example, the uptake of unpaid leave, extended parental leave at reduced pay, or the employment of a nanny (dagmamma) (for example, Østbakken, Halrynjo and Kitterød (2018[77]), Ellingsæter (2020[78]) and Moafi (2017[64])). The reduced income or the additional expenses under these arrangements are often paid through the cash-for-care benefit.

Nevertheless, parents can still apply to a kindergarten place even if their child is below the age of one. Subject to availability, priority is given to children of single parents, siblings of children already in the kindergarten as well as foster children or those with special needs. This leads to an enrolment of about 5% of children below the age of one a kindergarten in 2021 (Statistics Norway, 2023[54]). However, it often means that these children do not attend kindergarten in the close vicinity of their home.

One potential avenue to avoid the unequal waiting period – and current fertility trends will diminish demand – would be to grant the right to a kindergarten place at the end of the month children turn one not only to those born between September and November but also to children born in the December to August period. This would minimise the problems with late eligibility to kindergartens and likely reduce the reliance on unpaid leave, costly nannies and other alternative childcare arrangements. The vast majority of municipalities – a little more than 9 out of 10 – support such a further extension of the statutory right to a kindergarten place (Naper et al., 2021[79]).

Such an entitlement is, for example, granted in Denmark, Germany, and Sweden. In Denmark, the Act on Day Care of 2001 grants the statutory right to a place in a day-care facility from the age of 26 weeks regardless of their birth-month, while municipalities face financial sanctions should they not be able to provide such a place (Eurydice, 2019[80]). This has resulted in very high enrolment rates at the youngest ages – about 18% below the age of 1 attend centre-based childcare, while 90% of children between the ages 1 and 2 do so (Blaakilde and Siren, 2021[81]). These policies have had a positive impact on the education outcomes of children in disadvantaged families, while at the same time enabling mothers to engage on the labour market (Heckman and Landersø, 2021[82]; Lind, 2021[83]). The Education Act of 2010 in Sweden, grants working parents a place in centre-based preschool once their child turns one, which has to be offered within 4 months after their application. Since 2013, Germany offers parents a right to a place in centre-based or home-based care for children from their first birthday (Eurydice, 2019[80]). However, Germany is currently still struggling to meet the high demand for childcare places, so that 13% of parents that want to place their child in day-care are unable to find a place, particularly affecting those from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds (Jessen and Spieß, 2019[84]).

A seamless transition from paid parental leave through a right to a kindergarten spot at age one could facilitate a phase-out of the cash-for-benefit scheme (kontantstøtte) which has been criticised for its dampening effects on gender equality within households. Today, it is often used to cover for the time after paid parental leave and before children enter kindergarten (Arntsen, Lima and Rudlende, 2019[39]). The money saved from phasing the cash-for-care benefit out could be steered towards kindergarten.

Children in Norway enter school in the calendar year they turn 6, with compulsory schooling for ten years over two distinct stages in primary school (grades 1 to 7) and lower secondary school (grades 8 to 10). A school year typically runs from mid-August to late June and primary school children start their school day at 08:15 and typically end it before 14:00. As such, normal school hours are generally incompatible with a full-time working week for both parents. Similar situations in many OECD countries have led to the development of more or less comprehensive out-of-school-hours (OSH) service systems across, particularly since the early 2000s and as well in Norway (Fukkink and Boogaard, 2020[85]; Plantenga and Remery, 2017[86]).

Since 1999, all Norwegian municipalities have to offer voluntary day-care facilities (skolefritidsordningen or SFO) before- and after school hours to cover the time parents of primary school children may be engaged in work. The facilities are typically open outside of school hours until 17:00 and can be used on a full- or part-time basis, thus offering parents flexibility when it comes to engagement on the labour market. For children with special needs, SFO is available up to grade 7 (Eurydice, 2022[87]). Since 2010, Norwegian schools offer free voluntary homework assistance in co-operation with the SFOs, for children from grades 1 to 4. In 2014, this offer was further extended to cover children in all grades of compulsory schooling, thus up till grade 10 (OECD, 2020[88]).

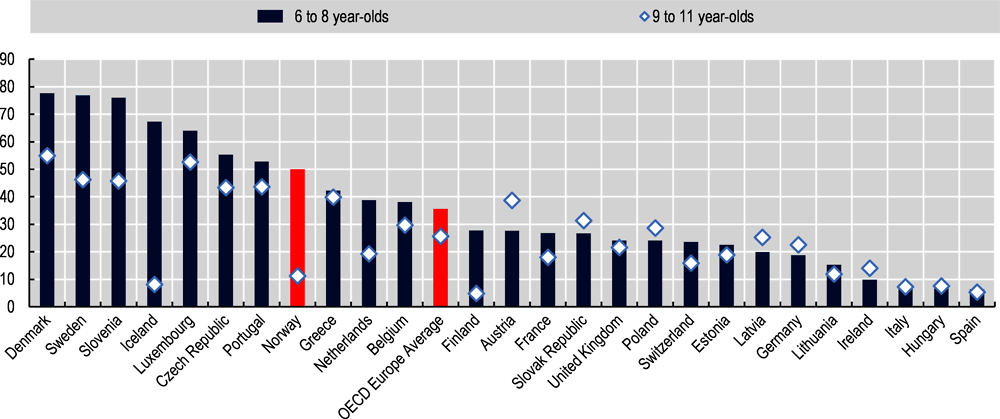

From an international perspective, enrolment in Norwegian SFO is fairly widespread, with half of all 6 to 8-year-old children attending in 2019 (50%), while on average across European OECD countries about every third child attends centre-based out-of-school-hours services. There is a sharp drop in attendance among Norwegian children aged between 9 and 11 years – only about 11% of these children attend SFO, while across European OECD countries it is more than twice as much (26%). Attendance across ages is substantially lower in Norway than in neighbouring Denmark and Sweden – where attendance also falls away with age – but very similar to Iceland and notably higher than in Finland (Figure 3.10).

The comparatively low attendance rate in SFO for older children can, in part, be explained by the relatively high prices, especially in comparison to the Norwegian ECEC-system which covers longer weekly hours. About one-third of parents who do not have their child in SFO state that price is a reason. Fees for SFO attendance vary by municipality. In the school year of 2019-20, the average monthly fee was about NOK 2 500 (USD 253) for a full-time SFO, while part-time SFO was slightly cheaper at NOK 1 500 (USD 152). However, some municipalities charge over NOK 3 000 (USD 303) a month for a full-time place, while about a third of all municipalities offer at least some free SFO places (e.g. to attract families). Other reasons for non-attendance include children of this age not wanting to be in SFO and a lack of transport, which is only provided for school hours (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2020[89]; Wendelborg et al., 2018[90]).

To reduce the financial pressure on parents who want to place their children in SFO, there are several discounts and support schemes available. For example, since 2020 municipalities are required to offer a reduction in parental payment that caps the fee at a maximum of 6% of the gross household income. This applied initially to 1st and 2nd graders, but since August 2021, it also covers children 3rd and 4th grade. For children with special needs between grades 5 and 7, SFO is free (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2020[91]). From August 2022, first graders have been entitled to 12 hours of free core time in SFO per week (Kommunal- og distriktsdepartementet, 2022[92]). In some municipalities, for example Oslo, 12 hours of free core time in SFO per week are granted for all children in grades 1 to 4 in the school year 2022/2023, and some other municipalities offer reductions in SFO fees if parents have multiple children attending, similar to the søskenmoderasjon reduction in kindergarten (see above).

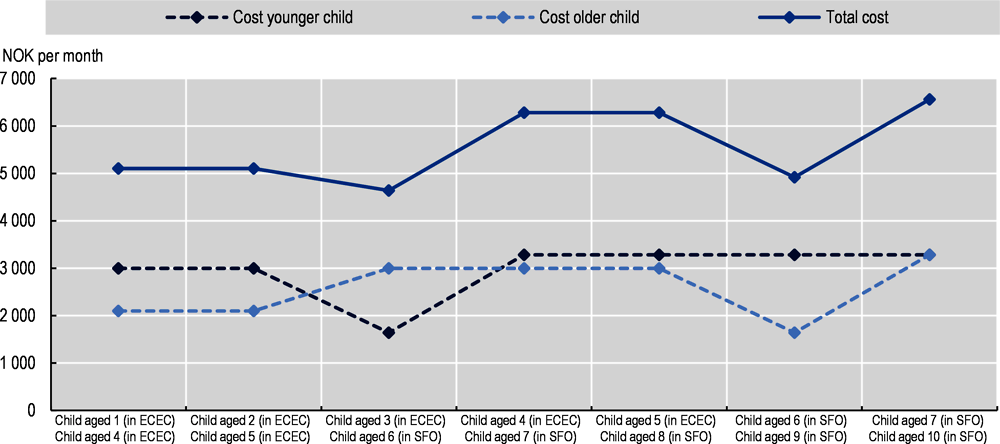

Despite available support schemes, SFO can often be as expensive as the fees paid for kindergarten attendance, especially as some support measures are not streamlined between kindergarten and SFO. If parents receive a reduction on their fees while two children attend kindergarten, they lose it once the oldest enters school and attends SFO facilities. This is does not have a large effect on aggregate costs for parents while children receive free core time in SFO, but in some municipalities parents can face somewhat higher total fees when this measure is no longer granted. For example, the municipality of Trondheim has relatively high full-time SFO fees of NOK 3 280, which means that once the oldest child of a hypothetical two-child family enters the 2nd grade and loses the right to free core time, the aggregate fees paid for kindergarten and SFO are almost 25% higher than when both are in kindergarten (Figure 3.11). While this does not represent a critical barrier to employment – nor is it a substantial “discount cliff” – but it could be beneficial for the financial stability of families to streamline the discount schemes not only nationally, but also across kindergarten and SFOs.

Free centre-based out-of-school-hours care is, for example, offered in Slovenia, where children from 1st to 5th grade can voluntarily attend the extended stay programme (Razširjeni programme). The programme is typically organised from after school until 17:00, while 1st graders can also attend morning care from 06:00. Aside from providing room for study and homework, the programme is organised under a national curriculum that aims to provide extra-curricular activities that foster healthy and holistic personal development based on children’s individual abilities, interests, and talents. The expenses of these programmes are entirely covered by the state (Euredyce, 2022[93]; Zavod rs za šolstvo, 2021[94]). As a result, centre-based out-of-school-hours care attendance for all ages between 6 and 11 in Slovenia is among the highest in the OECD (Figure 3.10).

In Norway, SFO was introduced without a unified national curriculum and framework plan, which has led to considerable variation in the SFOs quality, organisation, content, and objectives across municipalities. While some SFOs are have developed comprehensive pedagogical plans and curricula that offer free play and learning support in co-ordination with school content, others operate more as a place for the supervision of children while they wait until their parents return from work. Such a variation in quality and content could help explain why some children do not want to attend SFO (Wendelborg et al., 2018[90]). However, from August 2021 a new framework plan that provides unified guidelines for quality development and planning work across Norway has been introduced, which may elevate and streamline the quality and content of SFOs across Norway.

The framework plan specifies that SFOs have to operate under the same values as kindergartens and schools to facilitate a better transition between kindergarten, school and after-school services Utdanningsdirektoratet (2021[95]), and Wendelborg et al. (2018[90]). At the same time, the guidelines require SFOs to provide health-promoting content around indoor and outdoor play, as well as culture and leisure activities adapted to the children’s age. While each SFO can adjust their content to the school, there is no explicit requirement for this, and the main emphasis is put on free play and other child-led activities. In contrast to the practice in most Norwegian SFOs so far, the new framework spells out the inclusion of minority language and immigrant children as a core pillar, so that diversity in culture, language and forms of expression can be included and fostered in play and activity.

Family policy provides varying degrees of support for families over the early life-course of their child(ren). Policies in Norway provide a continuum of supports – parental leave, ECEC services, schools and OSH-services. Nevertheless, despite the comprehensive family policy framework, Norway and many other OECD countries, have recently experienced declining TFRs.

This section presents the results of an OECD-wide regression that estimates the within-country over-time association between different aspects of the family policy framework and fertility rates as well as the mean age of mothers at childbirth (Figure 3.12). As in other chapters of this report, the resulting coefficients should be interpreted as an association between policies in a specific country and its respective fertility outcomes. The results do not provide evidence of a causal relationship between family policy and fertility, but nonetheless provide insights on which policies may be more likely to affect birth rates than others. Based on data availability, all regressions refer to the period 2002-18. A more detailed methodology is available in Annex 1.B.

3.7.1. The link between family leaves and fertility is often positive

The availability of paid maternity-, paternity- and parental leaves can support fertility, as it allows to take the necessary leave of absence from work to care for a young child. The precise effects of these leaves on fertility are, highly context dependent, particularly for fathers’ leave (see below). Figure 3.12 shows a significant association between increases in the length of paid leave available to mothers and increases in the TFR, but not with their mean age at childbirth. Increases in paid weeks of paternity and parental leave reserved for fathers, are not associated with fertility rates, nor with small decreases in the mean age of mothers at childbirth. There is a strong and significant positive effect of increases in the per-child expenditure on family leave benefits on fertility and a significant negative effect on the mean age at childbirth.

In the literature, the effect of parental leave on fertility is difficult to capture. As pointed out by Bergsvik, Fauske and Hart (2020[34]), the effects of changes in parental leave entitlements are difficult to evaluate as the links with fertility rates are highly dependent on the country’s context as well as the extent of the change in the studied reforms. In general, however, there seem to be positive effects of parental leave reforms on subsequent fertility rates (Thomas et al. (2022[96])). For example, second births among Austrian mothers increased when parental leave was increased from one year to two years in 1990 (Lalive and Zweimüller, 2009[97]). For the Nordic countries, some studies find timing effects after parental leave reforms, while no general effects of parental or paternity leave extensions on fertility rates are apparent (Cools, Fiva and Kirkebøen, 2015[98]; Hart, Andersen and Drange, 2019[99]; Liu and Skansy, 2010[100]; Duvander, Lappegard and Johansson, 2020[35]). In Norway, several reforms that increased parental leave entitlements between 1987 and 1992 had only marginal effects on fertility over the 14 years after the reforms (Dahl et al., 2016[101]).

In terms of parental leave use by fathers, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish families in which fathers take parental leave are more likely to have a second child, although the results for the likelihood to have a third child are inconclusive (Duvander et al., 2019[32]; Duvander, Lappegård and Andersson, 2010[33]). In Spain however, the introduction of two weeks of paid paternity leave resulted in delayed subsequent fertility (Farré and González, 2019[102]), while in Korea, fathers who took family leave were less likely to want another child relative to those who are just about to start their leave (Lee, 2022[103]). In Norway, an extended father’s quota had no effect on subsequent fertility (Hart, Andersen and Drange, 2022[104]).

3.7.2. ECEC services have a positive association with fertility rates

ECEC services help both parents combine work and family commitments, until children go to primary school. The availability and affordability of ECEC services may affect decisions around (the timing of) becoming a parent or extending the family. However, the aggregate enrolment in public childcare facilities is not clearly associated with TFRs or the average age of mothers at childbirth (Figure 3.12). However, increases in public spending on childcare services – which includes, the direct financing or subsidisation of ECEC facilities – strong and significant positive link with the TFR and a significant negative link with the mean age at childbirth. Overall, this appears to suggest that the quality and affordability of ECEC – both of which are captured in the public expenditure on in-kind family benefits, alongside expenditure related to ECEC capacity – are important factors for the transition to parenthood at earlier ages.

In the literature, a positive impact of ECEC provision on fertility is found in quasi-experiments in Norway (Rindfuss et al., 2010[60]; Rindfuss et al., 2007[58]), Sweden (Mörk, Sjögren and Svaleryd, 2011[105]), Germany (Bauernschuster, Hener and Rainer, 2015[106]), Japan (Fukai, 2017[107]) and Belgium (Wood and Neels, 2019[108]). Some of these studies highlight that the effect of ECEC is strongest for second and third births, which may be the reason why benefits in kind are not significantly associated with the mean age at first birth. However, particularly for dual-earner households, ECEC may also have a noticeable effect on first births (Bergsvik, Fauske and Hart, 2020[34]) Individual country experiences can be different, as for example illustrated by the experience in Korea (Box 3.4).

3.7.3. Cash benefits usually only have temporary and transitory effects on fertility

Theoretically, cash transfers for families with children, such as family or child allowances, reduce the (opportunity-) costs of childbirth and could therefore increase fertility rates, but negative substitution effects, such as investing more in children already born, may suppress such positive associations (Bergsvik, Fauske and Hart, 2020[34]). Although studying their effects on fertility is complicated by a lack of natural experiments, most research indicates that cash transfers for families with children have no or only moderately positive effects on fertility (Skirbekk, 2022[110]). Figure 3.12 shows that increases in family allowances are linked to rising fertility, potentially by making the transition to parenthood easier and more affordable. It is important to note that family allowances in this context refer to child benefits that are paid to the family throughout childhood (e.g. the Norwegian Barnetrygd until the child turns 18), rather than so-called “baby-bonuses” that are paid once upon birth.

In the literature, the impact of cash transfers varies widely based on the country studied and has mostly focused on the direct effect of “baby-bonuses” as they are designed as a direct incentive for childbirth Research on the Australian Baby Bonus, for example, demonstrates that such cash transfers have played a small but statistically significant role in increasing the fertility rate, with the strongest positive effect on immigrant women with low educational attainment (Bonner and Sarkar, 2020[111]; Parr and Guest, 2011[112]). In the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, a baby bonus increased higher-order births, especially for lower educated mothers (Boccuzzo et al., 2007[113]).

Any positive effects of family cash benefits on fertility are, however, generally only temporary and transitory in nature. For example, Swiss lump-sum birth allowances, rolled out in a number of different cantons over time, temporarily increased the TFR by 5.5%, but this effect faded quickly (Chuard and Chuard-Keller, 2021[114]). In Spain, the implementation of a lump-sum universal child transfer led to an increase in 3% in the TFR, but a cancelation of the programme in 2010 led to a decrease in the TFR of 6%, outweighing the increase that existed while the programme was active (González and Trommlerová, 2021[115]). Similarly in France, a restriction of the eligibility criteria for early childhood allowances (PAJE) led to declining fertility through postponement of births to later ages (El-Mallakh, 2021[49]). Hungary has spent large sums on incentivising higher-parity births through various cash benefits, and these have may contributed to a stabilisation of birth rates rather than the desired increase which would stop the ongoing population decline (Box 3.1). The Polish 500+ child benefit also failed to raise fertility rates noticeably, while at the same time weakening financial incentives to work for mothers with young children (Box 3.2). In Norway, the cash-for-care benefit, has slowed the progression to second births, while fertility declined among employed mothers with upper secondary education. However, this effect may be driven by interactions with the employment-history eligibility requirements of the parental leave system (Section 3.4).

References

[9] Albert, F. (2020), Hungary: Tax exemption for mothers of four or more children, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=22505&langId=en.

[38] Andersen, S., N. Drange and T. Lappegård (2018), “Can a cash transfer to families change fertility behaviour?”, Demographic Research, Vol. 38/1, https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.33.

[66] Arbeids- og velferdsetaten (2022), Stønad til barnetilsyn for enslig mor eller far, https://www.nav.no/barnetilsyn-enslig.

[14] Arbeids- og velferdsetaten (2021), Foreldrepenger, engangsstønad og svangerskapspenger, https://www.nav.no/no/nav-og-samfunn/statistikk/familie-statistikk/foreldrepenger-engangsstonad-og-svangerskapspenger.

[39] Arntsen, L., I. Lima and L. Rudlende (2019), Hvem mottar kontantstøtte og hvordan bruker de den?, https://www.nav.no/no/nav-og-samfunn/kunnskap/analyser-fra-nav/arbeid-og-velferd/arbeid-og-velferd/hvem-mottar-kontantstotte-og-hvordan-bruker-de-den.

[116] Azmat, G. and L. González (2010), “Targeting fertility and female participation through the income tax”, Labour Economics, Vol. 17/3, pp. 487-502, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.09.006.

[42] Bargu, A. and M. Morgandi (2018), “Can Mothers Afford to Work in Poland?: Labor Supply Incentives of Social Benefits and Childcare Costs”, Policy Research Working Paper, Vol. 8295, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29158/WPS8295.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[106] Bauernschuster, S., T. Hener and H. Rainer (2015), “Children of a (Policy) Revolution: The Introduction of Universal Child Care and Its Effect on Fertility”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 14/4, pp. 975-1005, https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12158.

[34] Bergsvik, J., A. Fauske and R. Hart (2020), “Effects of policy on fertility. A systematic review of (quasi)experiments”, Statistics Norway Discussion Papers, Vol. 922, https://www.ssb.no/en/forskning/discussion-papers/_attachment/412670.

[81] Blaakilde, A. and A. Siren (2021), Intergenerational families in Denmark, Information Age Publishing.

[113] Boccuzzo, G. et al. (2007), “The impact of the bonus at birth on reproductive behaviour in a lowest-low fertility context: Friuli-venezia giulia (Italy), 1989-2005”, Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, Vol. 6/1, https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2008s125.

[111] Bonner, S. and D. Sarkar (2020), “Who responds to fertility-boosting incentives? Evidence from pro-natal policies in Australia”, Demographic Research, Vol. 42, pp. 513-548, https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2020.42.18.

[30] Brandth, B. and E. Kvande (2019), “Workplace support of fathers’ parental leave use in Norway”, Community, Work & Family, Vol. 22/1, pp. 43-57, https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1472067.

[37] Bungum, B. and E. Kvande (2013), “The rise and fall of cash for care in Norway: changes in the use of child-care policies”, Nordic Journal of Social Research, Vol. 4, https://doi.org/10.7577/njsr.2065.

[114] Chuard, C. and P. Chuard-Keller (2021), “Baby bonus in Switzerland: Effects on fertility, newborn health, and birth-scheduling”, Health Economics (United Kingdom), Vol. 30/9, https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4366.

[98] Cools, S., J. Fiva and L. Kirkebøen (2015), “Causal Effects of Paternity Leave on Children and Parents”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 117/3, https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12113.

[36] Cools, S. and M. Strøm (2020), Ønsker om barn – en spørreundersøkelse om fertilitet, arbeidsliv og familiepolitikk, https://samfunnsforskning.brage.unit.no/samfunnsforskning-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2645776/%C3%98nsker_om_barn.pdf?sequence=2.

[15] Corekcioglu, G., M. Francesconi and A. Kunze (2022), “Expansions in Paid Parental Leave and Mothers’ Economic Progress”, mimeo.

[101] Dahl, G. et al. (2016), “What is the case for paid maternity leave?”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 98/4, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00602.

[71] Dearing, E. et al. (2018), “Estimating the Consequences of Norway’s National Scale-Up of Early Childhood Education and Care (Beginning in Infancy) for Early Language Skills”, AERA Open, Vol. 4/1, p. 233285841875659, https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858418756598.

[74] Drange, N. (2021), Gratis kjernetid i barnehage i Oslo. Rapport 3: Oppfølging av barna på åttende trinn. SSB-rapport 30/2021, https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/finn-forskning/rapporter/gratis-kjernetid-i-barnehage-i-oslo-delrapport-3/.

[76] Drange, N. (2019), Child Care, Education and Equal Opportunity, Universitetsforlaget, https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215031415-2019-09.

[75] Drange, N. and T. Havnes (2019), “Early Childcare and Cognitive Development: Evidence from an Assignment Lottery”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 37/2, pp. 581-620, https://doi.org/10.1086/700193.

[26] Druedahl, J., M. Ejrnæs and T. Jørgensen (2019), “Earmarked paternity leave and the relative income within couples”, Economics Letters, Vol. 180, pp. 85-88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2019.04.018.

[32] Duvander, A. et al. (2019), “Parental leave policies and continued childbearing in Iceland, Norway, and Sweden”, Demographic Research, Vol. 40, pp. 1501-1528, https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2019.40.51.

[33] Duvander, A., T. Lappegård and G. Andersson (2010), “Family policy and fertility: fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden”, Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 20/1, pp. 45-57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928709352541.

[35] Duvander, A., T. Lappegard and M. Johansson (2020), “Impact of a Reform Towards Shared Parental Leave on Continued Fertility in Norway and Sweden”, Population Research and Policy Review, Vol. 39/6, pp. 1205-1229, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09574-y.

[117] EFTA Court (2019), Judgement of the Court: Case E-1/18, https://eftacourt.int/download/1-18-judgment/?wpdmdl=6387.

[44] Ekert, M. (2022), “Subject: Econometric analysis of the “family 500+” program – a study of the impact of the social benefit on the fertility of poles”, https://doi.org/10.19253/reme.2022.01.001.

[11] Ellingsæter, A. (2020), “Conflicting Policy Feedback: Enduring Tensions over Father Quotas in Norway”, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, Vol. 28/4, pp. 999-1024, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa027.

[78] Ellingsæter, A. (2020), “Fedrekvotepolitikkens dynamikk”, Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, Vol. 61/4, pp. 323-342, https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291x-2020-04-01.

[72] Ellingsæter, A., R. Kitterød and J. Lyngstad (2016), “Universalising Childcare, Changing Mothers’ Attitudes: Policy Feedback in Norway”, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 46/1, pp. 149-173, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047279416000349.

[5] Ellingsæter, A. and E. Pedersen (2015), “Institutional Trust: Family Policy and Fertility in Norway”, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, Vol. 23/1, pp. 119-141, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxv003.

[49] El-Mallakh, N. (2021), “Fertility, Family Policy, and Labor Supply: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from France”, SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3969868.

[3] Esping-Andersen, G. (1999), Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/0198742002.001.0001.

[93] Euredyce (2022), Slovenia: Single-structure primary and lower secondary education, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/organisation-single-structure-education-35_en.

[87] Eurydice (2022), Norway: Single-structure primary and lower secondary education, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/single-structure-education-integrated-primary-and-lower-secondary-education-20_en.

[80] Eurydice (2019), Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe – 2019 Edition, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/sites/default/files/ec0319375enn_0.pdf.

[102] Farré, L. and L. González (2019), “Does paternity leave reduce fertility?”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 172, pp. 52-66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.12.002.

[46] Finansdepartementet (2021), Prop. 1 S Tillegg 1 (2021 –2022) Proposisjon til Stortinget (forslag stortingsvedtak): Endring av Prop. 1 S (2021–2022) Statsbudsjettet 2022, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/6632aef843a74d519a6a008cb9ac1504/no/pdfs/prp202120220001t01dddpdfs.pdf.

[23] Finnish Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment (2022), Family leave reform enters into force in August 2022, https://tem.fi/en/-//1271139/family-leave-reform-enters-into-force-in-august-2022.

[107] Fukai, T. (2017), “Childcare availability and fertility: Evidence from municipalities in Japan”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, Vol. 43, pp. 1-18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2016.11.003.