3. Workforce and process quality in early childhood education and care

This chapter discusses the relationship between the early childhood education and care (ECEC) workforce and process quality. Building on research findings, this chapter discusses how ECEC staff’s initial education, professional development, working conditions and leadership can enhance process quality and support children’s learning, development and well-being. This chapter provides an overview of the policies that affect the ECEC workforce through a range of indicators across OECD countries and jurisdictions. It also provides concrete examples of good practices that can enhance process quality and child development through these policies.

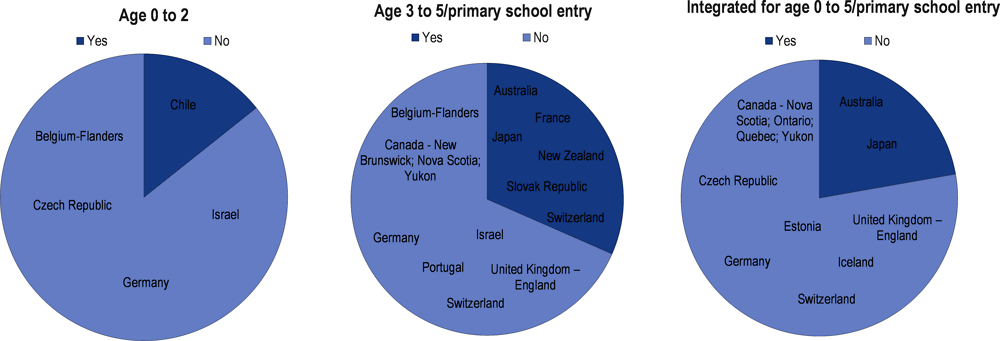

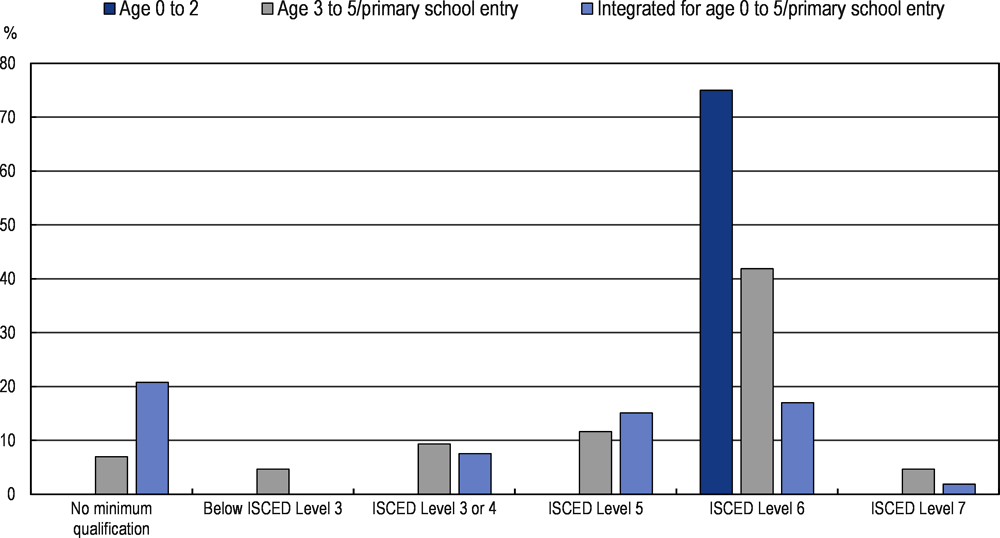

The most prevalent qualification required for teachers is a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED Level 6), although qualification requirements vary considerably among participating countries and jurisdictions. Compared to teachers’ qualifications, the qualifications of assistants are more homogeneous, the most prevalent qualification requirement being ISCED Level 3 (upper secondary education).

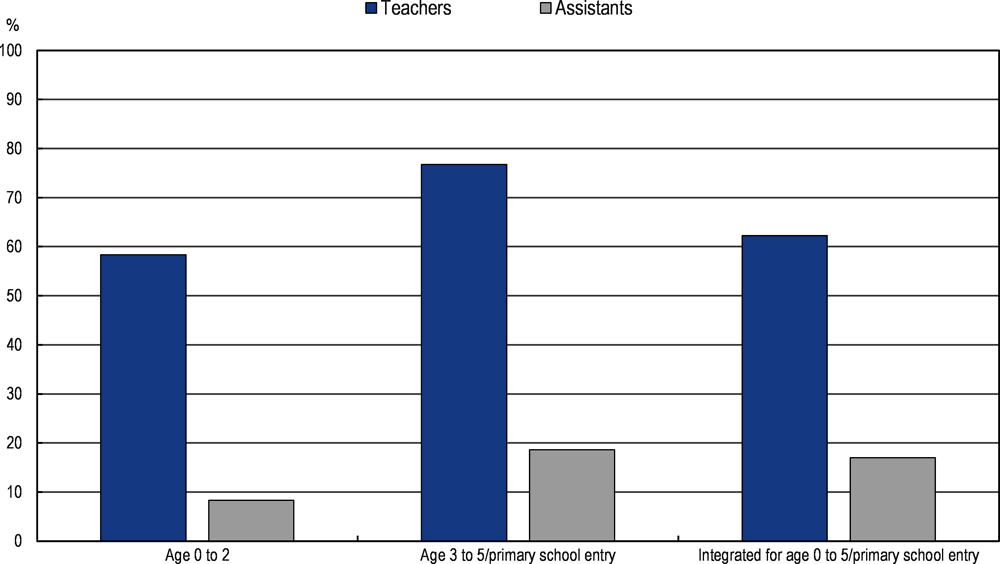

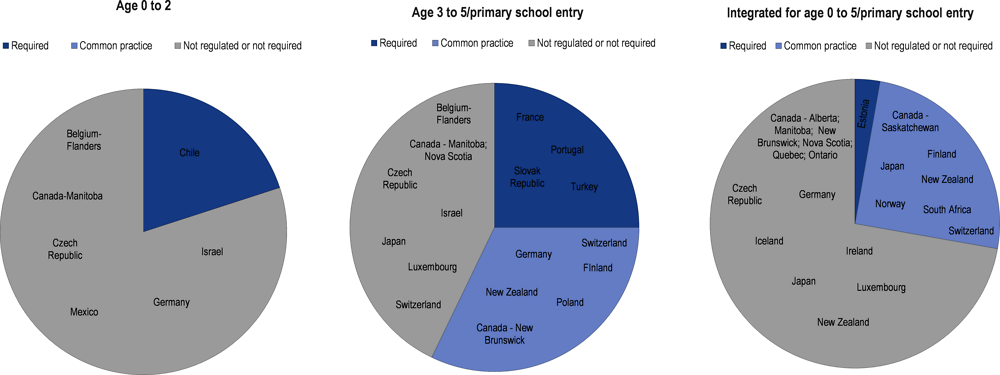

For early childhood education and care (ECEC) teachers, work-based learning during initial education is required for most settings covering children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry, as well as in most settings covering children aged 0 to 5/primary school entry, but not all. In settings for children aged 0 to 2, this is less frequent. For assistants, it is less common to require work-based learning in initial education.

The breadth of initial education of ECEC staff in terms of content areas varies sharply across countries and jurisdictions. This is true both for teachers and assistants. For assistants, initial education requirements in terms of content areas are less broad than for teachers. Most settings require teachers to have been trained in child development, playful learning aspects, and curriculum and pedagogy in general, although the implementation of the curriculum framework is less common. Linking ECEC and home-learning activities is one of the least covered topics.

While most participating countries and jurisdictions do not have accreditation of professional development activities and do not regulate the monitoring of quality, several countries have requirements for participation in professional development.

The assessment of staff professional development needs, and barriers to participation, in professional development is not a common practice in several participating countries and jurisdictions.

Allowing time for teachers to participate in professional development is a common or required practice in ECEC settings covering children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry, but is less frequent in settings for children aged 0 to 2. For assistants, time incentives to participate in professional development activities are not regulated or are not required in most participating countries and jurisdictions.

More generally, countries and jurisdictions differ in their regulations of time for activities to be performed without children, with some of them protecting time for a wide range of activities without children and others that do not. Regulations or practices that protect time are more common for teachers than for assistants across ECEC settings for all age groups. For teachers, protected time is higher in settings covering children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry.

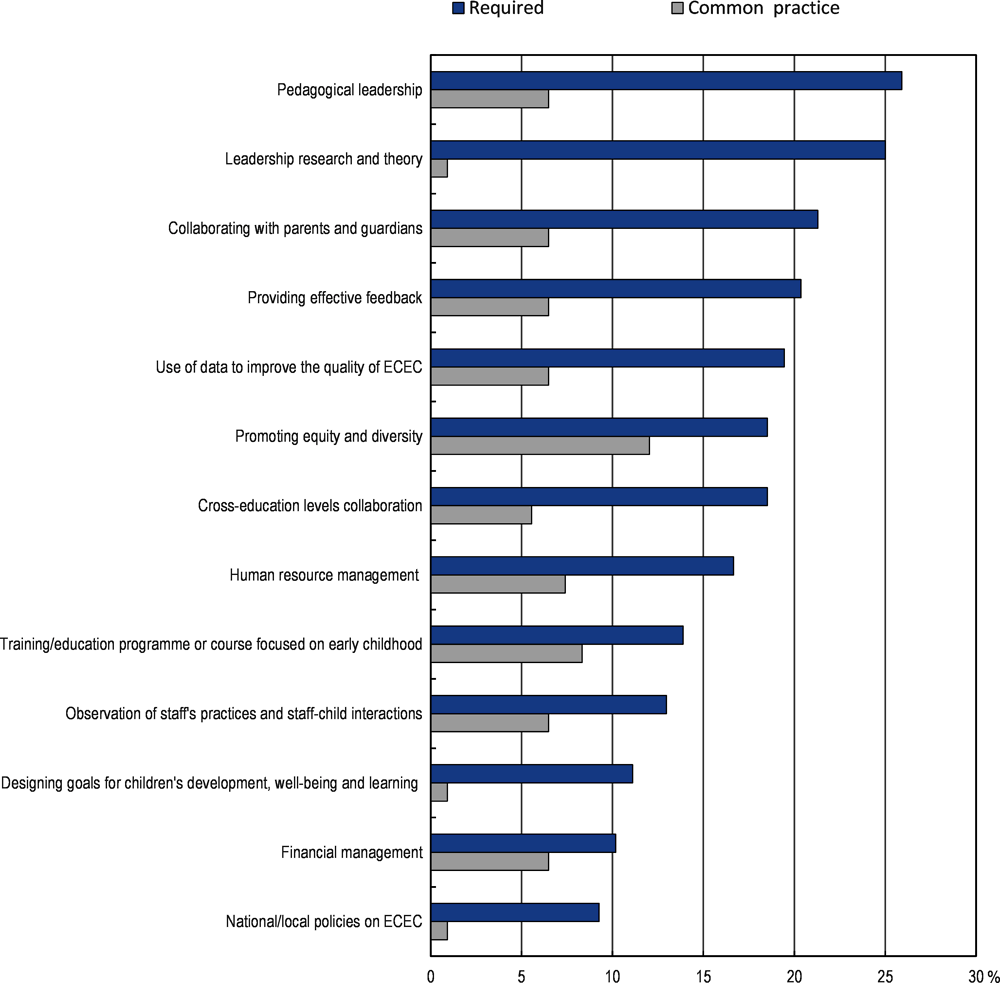

The most prevalent qualification required for ECEC centre leaders is tertiary education (ISCED Level 6). Several participating countries and jurisdictions have not reported information on the requirements for training programmes of leaders in terms of content, but for those who have, pedagogical leadership is widely covered.

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) professionals are key agents for assuring the quality of an ECEC system. ECEC professionals can profoundly shape children’s everyday interactions, which are likely to influence their learning, development and well-being. Among the vast array of features relevant for process quality - that is, the quality of interactions in ECEC settings - ECEC staff’s initial education has been identified as one of the strongest predictors of high process quality (Manning et al., 2019[1]). Similarly, professional development can help staff stay up to date on scientifically based strategies and knowledge, as well as feel supported and part of the team, which in turn contributes to high-quality practices. As such, preparing the ECEC workforce to work with children and ensuring that they can continuously engage in learning opportunities are at the very core of ECEC quality.

Working conditions, including salaries, contract status, and the organisational climate, are a second pillar for building and retaining a high-quality ECEC workforce (OECD, 2020[2]). Good working conditions can help sustain a positive working climate and support well-being, and thereby safeguard the capacity of the sector to retain highly motivated professionals. Relatedly, leaders in ECEC centres can play an important role in creating opportunities for improving working conditions and supporting professional development initiatives. Leaders can help build a respectful, trusting and safe environment necessary for skills improvement and teacher well-being (Ehrlich et al., 2019[3]; Ratner et al., 2018[4]).

This chapter details different dimensions of the ECEC workforce that research has highlighted as important for process quality. In addition, utilising data from the Quality beyond Regulations policy review, it presents a selection of key indicators related to workforce development in countries and jurisdictions that participated in the project and related data collection (Box 3.1). More indicators and figures on policies targeting the ECEC workforce can be found on the platform Starting Strong: Mapping quality in early childhood education and care, available at https://quality-ecec.oecd.org.

This chapter is based on findings on policies and regulations concerning the ECEC workforce from the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire for the reference year 2019, along with country background reports (see the Reader’s Guide for more information). Twenty-six countries, covering 41 jurisdictions, completed the policy questionnaire, and six countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg and Switzerland) provided background reports. Given the complex architecture of ECEC systems, the Quality beyond Regulations policy review collected information for each of the different curriculum frameworks (56 in total) and ECEC settings (121 in total) within the participating countries and jurisdictions.

Regarding workforce development, the questionnaire included questions on:

initial education and training (e.g. requirements in terms of level of education and content, accreditation responsibilities)

professional development (e.g. types of activities, content, incentives and assessment of needs)

working conditions (e.g. regulations on contractual status and wages).

Standardised age groups were assigned to the different curricula and settings to facilitate analysis and comparisons. The age groups were assigned as follows:

Age 0 to 2: If the majority of years of a setting or curriculum targets or covers children aged 0 to 2. This includes settings or curricula that start for children from birth (e.g. 12 weeks, 3 months, etc.) and end at age 2.

Age 3 to 5/primary school entry: If the majority of years of a setting or curriculum targets or covers children aged 3 to 5. This includes settings or curricula that start earlier than age 3 (e.g. 2.5 years) or later than age 3 (e.g. 4 years).

Integrated for age 0 to 5/primary school entry: If a setting or curriculum targets or covers children aged below and above the cut-off point of 3 years to a similar extent (e.g. 0 to 8 years).

Information was then aggregated across settings for indicators where information was the same or very similar within these standardised age groups (e.g. for a country with two settings in place for the same age group). No information for different settings was aggregated across different age groups.

Table A.A.2 in Annex A shows the list of settings for participating countries and jurisdictions included in this report.

The chapter focuses on staff who regularly work in a pedagogical way with children in ECEC settings. For comparability across countries and jurisdictions, staff have been classified as teachers or assistants, according to their overall roles in the ECEC centre.

The term “teachers” refers to the individuals with the most responsibility for a group of children at the class- or playroom-level. They may also be called pedagogues, educators, childcare practitioners or pedagogical staff.

The term “assistants” refers to ECEC staff whose role is to provide support to the teachers or lead staff member with a group of children.

The term “leader” refers to the person who has the most responsibility for administrative, managerial and/or pedagogical leadership at the ECEC centres.

Table A.A.3 in Annex C shows the categories of staff for participating countries and jurisdictions included in this report.

Within and across ECEC systems, there is a wide variety of settings. As mentioned above, 26 countries answered the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire and reported information on 121 settings, reflecting the complexity of the sector's organisation. Settings are often differentiated by age, whether they are centre-based or home-based, or whether they are specifically designed to serve specific groups of children. In order to enable comparisons within and across countries or jurisdictions, for the analyses conducted in this chapter, settings were classified into three groups:

settings serving mainly children aged 3 to 5 or until primary school entry

settings serving children from birth or aged 1 until entry into primary school, also called “integrated settings”.

Building on information from the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire and the six country background reports, this chapter provides insights into the main strengths and challenges faced by countries in building and retaining an ECEC workforce that can best support quality.

Initial education of ECEC staff is one of the most important determinants of quality in ECEC. It is also one of the main areas that can be regulated or changed through policies to improve the quality of ECEC provision. Initial education refers to the level and type of education required for ECEC staff to work in the sector. It includes the knowledge, skills and competencies recognised as important for working with young children (Manning et al., 2019[1]).

In addition to the qualification levels, specialised education in ECEC may be important for process quality in ECEC. Specialised training can help professionals build knowledge, skills and competencies, as well as provide pedagogical learning opportunities tailored to children’s developmental and socio-emotional needs. Studies examining the specific links between specialised training and interaction quality have pointed to the added value of focusing on ECEC in initial education programmes (Hu et al., 2019[5]; Schaack, Le and Setodji, 2017[6]; Wang, Hu and LoCasale-Crouch, 2020[7]; OECD, 2019[8]).

Researchers have tried to understand how initial education can shape ECEC staff practices with children (Romo-Escudero, LoCasale-Crouch and Turnbull, 2021[9]). Specifically, specialised training in ECEC can contribute to more complex and multifaceted knowledge about development, further supporting ECEC staff in more appropriately reading children’s cues and responding accordingly (Barros et al., 2018[10]; Schaack, Le and Setodji, 2017[6]). To be attuned and prepared to respond to child behaviours in real contexts, ECEC staff’s ability to notice behavioural markers of child development can be important, including noticing more salient markers, such as crying or vocalising, as well as more subtle ones, such as gestures and eye gaze (Romo-Escudero, LoCasale-Crouch and Turnbull, 2021[9]).

Initial education levels

Staff qualifications, that is, their level of education (e.g. secondary diploma, post-secondary diploma, university degree), are the most researched indicator and have the largest evidence base, with several studies pointing to positive links between higher qualifications and process quality (Manning et al., 2019[1]). Still, not all studies find a direct link between higher qualifications and higher process quality (von Suchodoletz et al., 2020[11]), suggesting the need to look above and beyond education levels and examine the content and delivery of initial education levels.

Highly qualified ECEC staff are better able to sustain enriching and stimulating interactions with children than staff with lower initial qualifications. These positive associations have been documented across regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, and countries, namely, Australia, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), Denmark, Germany, Norway, Portugal and the United States, for infant and toddler centre-based ECEC settings (Barros et al., 2018[10]; Bjørnestad et al., 2019[12]; Castle et al., 2016[13]), home-based settings (Eckhardt and Egert, 2020[14]; Schaack, Le and Setodji, 2017[6]) and pre-primary settings (Cadima, Aguiar and Barata, 2018[15]; Raikes et al., 2020[16]; Slot et al., 2018[17]).

Although the literature has primarily focused on teachers, assistants can also play an important role in assuring high levels of process quality (Sosinsky and Gilliam, 2011[18]). Studies examining the role of multiple staff members within a group have suggested that all staff, regardless of their roles, matter for process quality (Bjørnestad et al., 2019[12]; Barros et al., 2018[10]). Research also shows that the importance of assistants is recognised by teachers, who view them as extremely useful in supporting them in their multiple tasks and interacting with children (Sosinsky and Gilliam, 2011[18]).

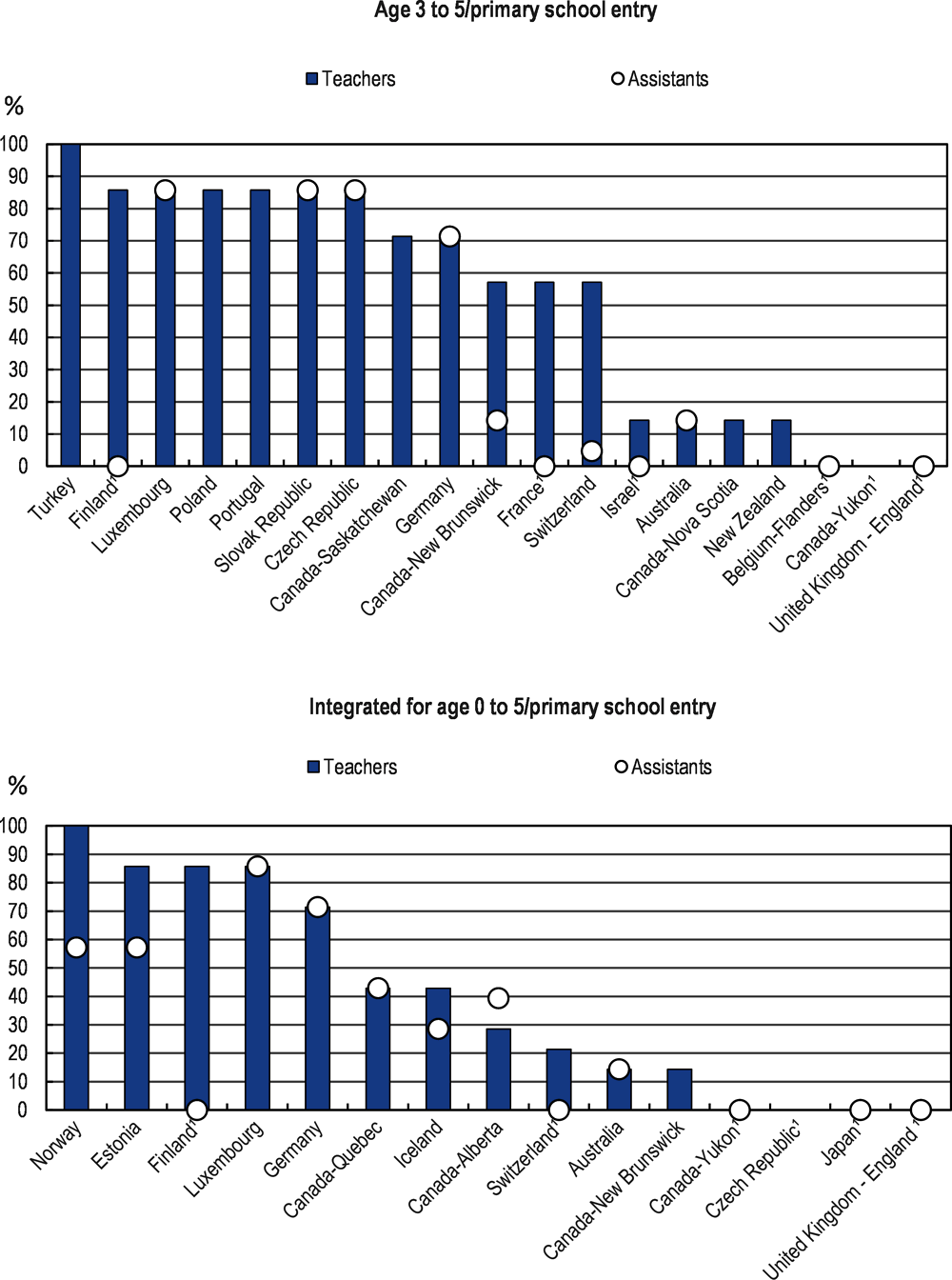

Data from the OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) show that across participating countries, a majority of staff report having at least some post-secondary education (International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED] Level 4 or above) (Figure 3.1). However, the educational profiles of staff vary substantially across countries. The overall educational attainment data hides differences between categories of staff, with teachers often having a bachelor’s degree or equivalent or higher, and some of the assistants not having an ISCED Level 4. Whether staff are trained specifically to work with children, which is also important for ECEC quality, is somewhat separate from their level of educational attainment. For example, in Germany and Japan, where junior college or vocational education and training programmes are most common for ECEC staff, nearly all staff are trained specifically to work with children, while in Turkey, where education at the level of a bachelor’s degree or equivalent or higher is most typical for ECEC staff, more than one-quarter of staff do not have training specifically to work with children.

Setting education requirements is a way to ensure that ECEC staff have at least a certain level of education, though it may take time for the whole workforce to reach this level. The most prevalent qualification requirement for teachers across countries and jurisdictions participating in the Quality beyond Regulations policy review varies between ISCED Level 5 and ISCED Level 7, with the exception of the Slovak Republic (ISCED Level 3) (Table 3.1).1 For the majority of countries with available data, a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED Level 6) is the most prevalent qualification requirement. France, Poland and Portugal are the countries with the highest level of qualification requirements, which is a master’s degree or equivalent (ISCED Level 7).

In comparison to teachers’ education requirements, requirements for assistants are more homogeneous across countries. For most countries with available data, the most prevalent qualification required for assistants is ISCED Level 3 (upper secondary education), with one exception being Mexico, which requires ISCED Level 2 and further training. In half of these countries, Chile, France, Germany and Slovenia, the requirement for assistants is a vocational education programme.

Learning from countries: Increasing the number of qualified staff

Several countries have employed a range of strategies to increase the number of qualified teachers over time, such as setting higher standards, incentive mechanisms, or offering workplace education opportunities for staff working in ECEC.

In Australia, since 2012, higher workforce requirements have been progressively introduced. Centre-based services with children in pre-primary education are required to employ at least a qualified teacher, and additional requirements (two qualified teachers) hold for some large settings. Furthermore, requirements cover both teachers and assistants: half of the staff must hold or be working towards at least a short-cycle tertiary qualification (ISCED Level 5), and the other half must hold or be working towards at least a post-secondary qualification at ISCED Level 4. In line with increasing regulatory requirements, the qualification of the ECEC workforce in Australia has increased over recent years.

In Canada, many provinces and territories have recently set new standards for initial education. For example, in the province of Nova Scotia, the curricula of post-secondary programmes have been updated to meet the adopted new standard on learning outcomes. The province also introduced a process of recognition of prior learning to provide individuals working for ten years or more in the ECEC field the opportunity to demonstrate they have acquired the necessary knowledge and skills to obtain an ECEC qualification.

In Ireland, new qualification requirements have been introduced in past years, as well as incentives for centres to hire ECEC staff with higher qualifications. Teachers (so-called “room leaders” in the Early Childhood Care and Education programme) are now required to have an ISCED Level 5 diploma at the minimum, but centres with teachers who hold a university degree (ISCED Level 6) in early childhood receive higher funding. The proportion of settings in the Early Childhood Care and Education programme with graduate teachers has increased in the last decade, rising from 20% in 2012/13 to over 50% in 2018/19. For all staff who work directly with children, the minimum requirement is a major award in ECEC at ISCED Level 4.

In addition to incentives or regulations to raise the education level of the ECEC workforce, defining standards for initial education, such as on its content or inclusion of a practical component, can be an effective means of ensuring quality and consistency across programmes (Box 3.2).

In Australia, the Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority determines the qualifications required for staff included in mandated staff-to-child ratios, including educational level, early years focus, practicum and curriculum content. Approved qualifications for teachers must have an appropriate pedagogical focus and provide professional experience with children aged birth to five. For vocational qualifications, the programmes must comply with national quality standards for training and assessment. Standards are developed through a collaborative process with the sector and industry groups.

In Ireland, Professional Awards Criteria and Guidelines for initial education programmes for teachers (at ISCED Level 6) were developed in 2017 and 2018 to improve the quality and consistency of degree programmes. The development of these criteria included consultation of higher education specialists and practitioners. The adherence of the programmes to the criteria is being assessed in 2021. For major awards at ISCED Levels 4-6, additional descriptors that define standards of knowledge, skills, and competencies will be incorporated, beginning in September 2021.

In Japan, there are national standards for the core curriculum for initial education programmes, including standards regarding subjects and required credits. The national standards are developed and improved with the involvement of scholars in the field of ECEC, officials of administrative facilities, ECEC staff and relevant professional associations. The core curriculum for initial education programmes aims to ensure consistency across programmes nationwide and to support quality.

In Canada, most provinces and territories’ governments (7 out 13) provide standards for initial education programmes. For example, in Ontario, initial education institutions must be approved by Ontario's College of Early Childhood Educators so that graduates are recognised as qualified staff. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the standards define minimum requirements on content, length and practicum placements. New Brunswick adopted standards for initial education in 2018. In Quebec, to be considered as “qualified”, staff must have completed a specific programme (Diploma of Collegial Studies in Early Childhood Education) that includes a general education component and a training component specific to early childhood. These programmes have to be approved by the Quebec Department of Education and Higher learning.

Integrating work-based learning into initial education

Work-based learning during initial education for ECEC professionals is associated with quality in ECEC. The international literature has long highlighted the important role played by work-based training for sustaining situated and contextual-based learning (Balduzzi and Lazzari, 2015[20]; Flämig, König and Spiekermann, 2015[21]). A common characteristic of work-based learning is the combination of theory and practice, supporting the development of knowledge and skills that are at the core of the ECEC profession (Ärlemalm-Hagsér, 2017[22]; Oberhuemer, 2015[23]; Lohmander, 2015[24]). Extended placement periods in ECEC settings during initial preparation may allow prospective staff to live the culture of practice, and to combine theoretical and experiential learning, helping them to critically reflect on their own practice (Balduzzi and Lazzari, 2015[20]). As prospective staff engage in hands-on activities and deal with challenges of everyday practice, they are provided with opportunities to build and apply new knowledge in real-life situations (Kaarby and Lindboe, 2016[25]). Additionally, observing teacher-child interactions within real-life situations has been shown to foster sensitive and rich interactions with children (Romo-Escudero, LoCasale-Crouch and Turnbull, 2021[9]; Fukkink et al., 2019[26]).

TALIS Starting Strong has looked into key features of initial education programmes across a number of countries, finding that initial education programmes that included practical placements in real work settings also covered more areas than staff programmes that did not have such a practical dimension (OECD, 2020[2]). These findings suggest that work-based learning can not only contribute to bridging theory and practice in ECEC, but also to broadening their curricular contents.

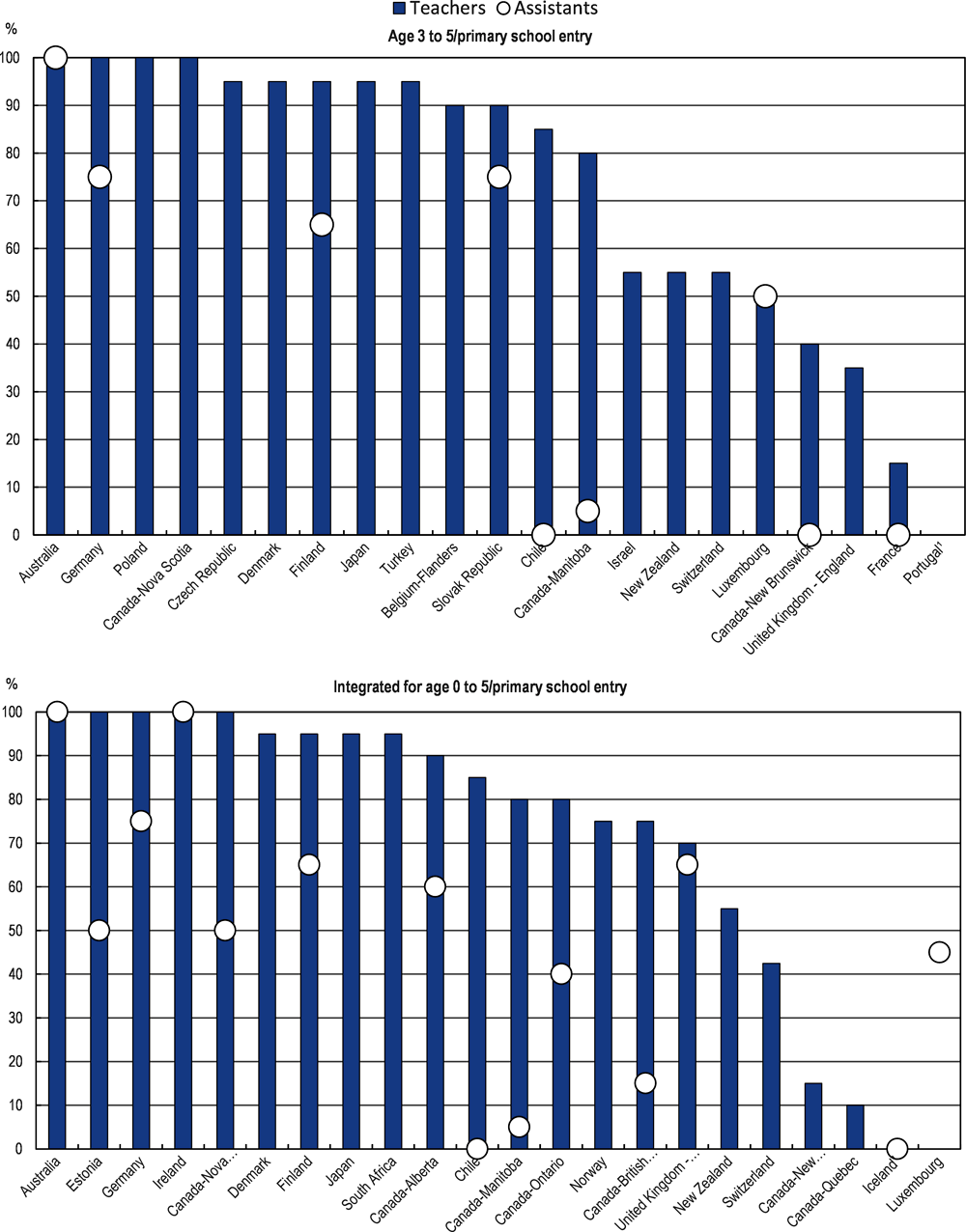

Despite the international recognition of the importance of work-based learning for prospective ECEC professionals, studies that investigate the content and delivery of initial preparation programmes are still relatively scarce. The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked whether a practicum is a required content of initial training for teachers and assistants. Results show that a practicum is required in most settings covering children aged 3 to 5, as well as in most of those for ages 0 to 5, but they are less frequent in settings for children aged 0 to 2 (Figure 3.2, Table C.3.1). On the other hand, it is far less common to include a practicum in initial education for assistants.

Learning from countries: Integration of work-based learning into initial education

In Australia, initial education programmes both for teachers and assistants include workplace-based learning to ensure that students acquire professional experience within an ECEC service. Students are required to develop and demonstrate their skills in real settings, through a strong co-operation between initial education institutions and ECEC settings. In addition to providing regular placement opportunities for students, ECEC settings also provide feedback and input into the development of initial education materials.

In Ireland, since 2017, the initial education programmes for staff are required to offer supervised practice placements, with a minimum of 35% of the overall duration of the course. Practice placements include a variety of settings to cover the full 0 to 6 age range. A survey conducted in 2015 to assess the satisfaction of staff with their initial training found that many of them felt there was a need for greater standardisation of the practicum to address its duration, content, supervision and assessment. This finding fed the development of guidelines for initial preparation. The Professional Award-type Descriptors for ISCED Levels 4 and 5, entering into force in 2021, will require participants to undertake a minimum of 150 hours per annum of professional practice, covering the work with both children aged 0 to 2 and older children. The workplace-based learning is designed to offer a variety of learning opportunities, including observation and self-assessment and application of theory and knowledge to practice.

Breadth of the content of initial education programmes

Working with young children requires specialised skills and content knowledge on a variety of subject and development areas. Building a robust base of knowledge across a variety of subjects is key for ECEC professionals to successfully cope with the practice challenges. Findings from TALIS Starting Strong show that the breadth of training of ECEC staff is positively associated with attitudes and practices related to process quality (OECD, 2020[2]). In all participating countries, pre-primary staff who covered more areas in both their initial and recent training report adapting their practices more to children’s needs and interests. Staff sense of self-efficacy for supporting child development and learning is also higher among staff who covered a greater number of areas in their training (OECD, 2020[2]).

The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked countries whether it is a requirement or common practice for teachers to cover specific content in order to obtain the minimum qualification in key areas such as child development, child health, curriculum and pedagogy, playful learning, classroom management, diversity, transitions and family and community engagement.

At least 80% of the content areas considered in the questionnaire are required to be included in teachers’ initial education and training programmes in the majority of participating countries and jurisdictions (12 out of 19) that set content requirements in ECEC settings for children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry. Australia, Germany, Poland and Canada (Nova Scotia) reach 100%. Belgium (Flanders), the Czech Republic, Denmark, Japan, the Slovak Republic and Turkey reach or surpass 90% coverage. Israel, Luxembourg and New Zealand cover approximately 50% of the content. In the remaining countries and jurisdictions, teachers’ initial education and training programmes cover less than half of the content (Figure 3.3). There are several reasons for this lower coverage. In some countries, there is no requirement on the content of initial training, but it is common practice to include several of these areas (e.g. Portugal). In Luxembourg, initial training programmes for teachers are not specific to ECEC, and therefore, there is no requirement to cover these areas. Some countries have included a wide range of settings in their responses to the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire, such as settings for after-school activities (e.g. Luxembourg and Switzerland) that are not considered to have an education objective by other countries, which also contributes to differences in requirements of initial education and training programmes for staff. Concerning assistants, Australia requires coverage of 100% of the contents, but other countries with available data require a less broad coverage of areas than for teachers.

Similarly, in settings for children aged 0 to 5/primary school entry, at least 80% of the content areas are included in teachers’ initial education and training programmes in the majority of participating countries and jurisdictions that set content requirements (14 out of 19). Regarding assistants, Australia and Ireland require coverage of 100% of the content, and other countries have a smaller content coverage.

In settings for children aged 0 to 2, in all countries and jurisdictions with available data that set content requirements, at least 70% of the considered content areas are covered in teachers’ initial education programmes for teachers and a smaller percentage for assistants (Figure C.3.1).

Most initial education programmes in participating countries and jurisdictions include aspects related to child development, be it as a requirement or a common practice (Figure 3.4). Most training programmes for teachers include playful learning aspects, such as facilitating play, and facilitating creativity and problem solving. Regarding curriculum and pedagogy, it is frequent to find initial education programmes covering learning theories, facilitating learning in arts, literacy and oral language, science and technology, and mathematics/numeracy, but less common on aspects related to implementing the curriculum framework. Regarding diversity issues, most training programmes for teachers include working with children from diverse backgrounds and with children with special needs, but it less common that programmes address issues related to dual or second-language learners. Areas such as working with parents from diverse backgrounds are commonly covered across settings, while linking ECEC and home-learning activities is one of the least covered topics.

Content requirements of initial education for assistants are, in comparison to teachers, less broad, with programmes having less than 20% of the considered areas being required and 30% of them being required or common practice. Some of the most commonly covered areas, either through requirement or common practice, are child health and playgroup or group management. In contrast, the least covered areas include learning theories, facilitating learning in science and technology and working with dual or second-language learners. These differences in initial programmes between teachers and assistants reflect differences in roles and responsibilities.

Preparing teachers to work with children with varying needs, interests and cultural backgrounds is important to foster inclusion and equity in ECEC, but it is not systematically covered in initial education programmes. As demands increase on ECEC staff to address diversity, this is an area of training increasingly prioritised in some countries (Box 3.3).

In Australia, teachers are prepared to promote equity and respect for diversity through initial education, with required contents covering several related topics, such as culture, diversity and inclusion, English as an additional language, multicultural education, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives, and socially inclusive practices. There are also several resources to support the inclusion of children from minority backgrounds. For example, in the state of Victoria, a practice guide has been published, “Supporting Bilingualism, Multilingualism and Language Learning in the Early Years”, that offers scenarios designed to help staff incorporate children’s family languages into daily practice. Additionally, a professional development package is available to support staff in implementing the curriculum framework in remote Indigenous settings. The resource targets staff who speak English as an additional language and is designed to encourage thinking and discussions about how to develop practices aligned with the core curriculum framework.

In Luxembourg, the ECEC system is characterised by its linguistic and cultural diversity, with most children exposed to more than one language from a very early age. A multilingual ECEC education programme for children aged 1 to 4 was introduced in 2017 to help them develop their language skills and be better prepared for a multilingual society and school system. The aims are to ensure an early introduction to the Luxembourgish and French languages, promote the appreciation and inclusion of all family languages, and support collaboration with families and local social and cultural services. ECEC teachers and assistants providing multilingual education receive initial and ongoing training specifically focused on multilingualism. Regular exchange meetings of the pedagogical officers are also organised, where participants can exchange ideas regarding multilingualism. In addition, staff are required to receive a minimum of eight hours of professional development in the field of multilingualism every two years.

In Canada, in many provinces and territories, initial education and professional development programmes are provided to support staff to respect and value diversity, and to recognise the unique needs of linguistic minorities and Indigenous communities. It is also mandatory for initial education programmes to cover working with parents from diverse backgrounds (e.g. in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Ontario). Candidates learn about families’ unique characteristics and are trained to implement family-centred approaches. Additionally, there are several professional development opportunities. For example, Nunavut has developed a centre-embedded professional development programme designed to support the implementation of culturally relevant practices of the Inuit culture. The programme is delivered by experts in Inuit culture and provides staff with opportunities for work-based learning and exchanges with Inuit community members. In Alberta, the programme, Getting Ready for Inclusion Today, provides professional development courses along with coaching to support staff in implementing inclusive practices. In New Brunswick, working with parents from diverse backgrounds is a mandatory component of professional development.

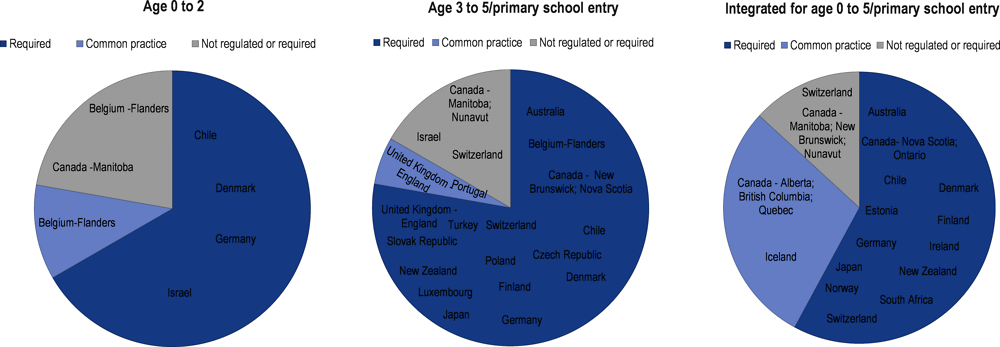

Aligning staff initial education with ECEC curriculum frameworks

Preparing staff to implement and use a curriculum as part of initial education programmes is crucial to ensuring good curriculum implementation and appropriate pedagogical practices. Across participating countries and jurisdictions, curriculum framework implementation in initial education programmes is largely required for teachers across ECEC settings for all age groups (Figure 3.5). Regarding assistants, the majority of countries and jurisdictions either require it or indicate it as common practice (Figure C.3.2). Still, there are some countries and jurisdictions for which the integration of curriculum framework implementation into ECEC staff initial education programmes is not regulated or required.

Learning from countries: Incorporating curriculum frameworks in ECEC staff’s initial education

In Australia, the curriculum is one of the core contents addressed by initial education programmes for all teachers and assistants. The approved programmes in the ECEC sector are required to offer opportunities for students to learn and understand the ECEC curriculum.

In Canada, in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec, the curriculum framework is also a required or common practice component of initial education. In some jurisdictions (Newfoundland and Labrador and Alberta), specific professional development courses were provided to ECEC faculty to prepare them to integrate the curriculum framework into the initial education programmes. In Ontario, the initial education programmes for assistants also commonly cover the curriculum framework.

In Ireland, the curriculum framework is not systematically incorporated into the initial professional education programmes of all staff. However, programmes starting in 2021 are required to cover curriculum framework implementation, planning, and assessment. Initial education will cover pedagogical practice aligned with the framework, such as enquiry-based, inclusion, developmentally appropriate practice, and children’s individual needs.

In Switzerland, too, the ECEC curriculum is part of the contents covered by the initial education programmes. The programmes include learning opportunities related to pedagogy and all curriculum areas. The initial education institutions were important partners in developing the curriculum, strengthening the connections between curriculum implementation and initial education.

Professional development is pivotal for ECEC staff to extend and update their knowledge and develop new skills (Hamre, Partee and Mulcahy, 2017[27]). Ensuring that ECEC staff can engage in diverse and stimulating professional development opportunities is key to assuring the continuity of a high-quality teaching workforce.

Professional development refers to the development of staff knowledge and skills, both through structured trainings and informal means, such as collaboration with colleagues and learning on the job. Structured professional development opportunities, either formal if they lead to qualifications, or non-formal if they do not, include courses, workshops, lectures, coaching or consultation involving experts’ feedback. Recent meta-analyses of studies with robust designs have suggested that teachers’ participation in professional development initiatives enhances process quality in ECEC settings, namely through the enhancement of teachers’ abilities to create close, warm and responsive relationships with children, to prevent and manage behaviour and to stimulate children’s thinking, reasoning and language development (Eckhardt and Egert, 2020[14]; Egert, Dederer and Fukkink, 2020[28]; Markussen-Brown et al., 2017[29]; Werner et al., 2016[30]).

Several professional development programmes have been shown to improve teachers’ interactions with children (Early et al., 2017[31]; Landry et al., 2014[32]; Williford et al., 2017[33]). In addition, several studies have shown that there is an impact or association between professional development and teacher well-being, self-efficacy, autonomy, reduced burnout, and a reduction in the odds of mid-year job turnover (Davis, Barrueco and Perry, 2020[34]; Wolf et al., 2018[35]). Professional development can also counteract negative influences of the work environment (Peleman et al., 2018[36]). Recent evidence has also shown that participating in professional development opportunities can buffer the negative effect of teachers’ burnout, stress and displeasure with their career (Sandilos et al., 2018[37]; Sandilos, Goble and Schwartz, 2020[38]), with some research suggesting that teachers with lower levels of education can benefit the most from participating in professional development courses (Barros et al., 2018[10]; Early et al., 2017[31]).

The design, content and delivery of professional development

Features of professional development programmes, such as their duration, delivery format, didactical elements and content focus, are important to understand in terms of their effects on process quality. There is a wide variety of professional development programmes, with several key variables highlighted as influencing process quality (Egert, Dederer and Fukkink, 2020[28]; Peleman et al., 2018[36]; Werner et al., 2016[30]). Important features include responsiveness to the context, a practical component, opportunities for reflection in real situations, and the inclusion of feedback or individual guidance.

Centre-embedded professional development initiatives can help meet the local needs of professionals (Peleman et al., 2018[36]) and enhance their relevance for professionals’ everyday experiences. Embedding professional development in real contexts can better reflect professionals’ specific resources, knowledge and beliefs, valuing their diverse competencies and expertise, and better promoting context-specific planning and improvement (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Peleman et al., 2018[36]; Jensen and Iannone, 2018[40]). Professional development interventions can also have positive effects when they involve dynamic learning approaches, with a focus on learning in practice and with professionals actively involved in the process (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Peleman et al., 2018[36]).

The inclusion of opportunities for teacher’s self-reflection and self-assessment has also been found to be particularly effective, especially for teachers’ abilities to support children’s thinking and reasoning (Egert, Dederer and Fukkink, 2020[28]). The critical reflection on day-to-day practices can help professionals to integrate practice into theories and goals, increasing their pedagogical awareness and professional understandings, which, in turn, can strengthen educational practices that are responsive to children’s needs, potentialities and learning strategies (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Peleman et al., 2018[36]).

Programmes that combine several components (namely a workshop, coursework and individual support) seem to be more effective than programmes that do not, suggesting that combining workshops, courses, and on-site support may enhance quality improvement by offering a variety of individual learning opportunities (Egert, Dederer and Fukkink, 2020[28]; Markussen-Brown et al., 2017[29]). The inclusion of individual support with a feedback component through coaching or mentoring seems crucial (Connors, 2019[41]; Egert, Fukkink and Eckhardt, 2018[42]; Markussen-Brown et al., 2017[29]). Research has also pointed to the importance of the relationship between mentors/consultants and teachers, with better consultant-consultee relationships predicting teacher-child closeness and positive classroom climate (Davis, Barrueco and Perry, 2020[34]). However, centre-embedded models of professional development, such as peer observation or mentoring, remain less common than off-site training activities (OECD, 2020[2]).

In addition to structured professional development, team collaboration and regular professional exchanges can improve feelings of support and belonging and be a valuable means to implement and transfer newly acquired knowledge (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Resa et al., 2018[43]). Research has shown that regular exchanges within the team are positively related to process quality (Resa et al., 2018[43]). It is possible that regular team meetings, such as discussing, asking for advice and receiving guidance, contribute to the emergence of a collaborative team culture and a good team climate that ultimately supports the daily implementation of newly acquired knowledge and skills (Jensen and Iannone, 2018[40]; Vangrieken et al., 2017[44]). Moreover, preschool teachers appear to consider that they learn the most when collaboration networks between staff are a core practice in their centres (Yin et al., 2019[45]).

As for initial education programmes, the breadth and focus of professional development can matter for process quality. Results from TALIS Starting Strong have indicated that teachers who were involved in a larger number of topics of professional development reported providing more individual support to children through adaptive practices, which is indicative of higher process quality (OECD, 2020[2]). Professional development serves mainly to deepen or update areas already included in initial education. In particular, staff trained specifically to work with a diversity of children are more likely to adapt their practices to children’s needs and interests, while ECEC staff show moderate confidence in their ability to work with a diversity of children. There is room to develop quality professional development programmes on working with children from diverse backgrounds (see Box 3.3).

Professional development can also be crucial for the implementation of a curriculum framework and the alignment between curriculum and pedagogical practices, especially when a curriculum framework is changed (see Chapter 2). In several countries, various professional development programmes have been put into place that aim to support ECEC staff in implementing the curriculum (Box 3.4).

In Australia, it is common to provide professional development on curriculum implementation. For example, the state of Victoria supports the implementation of the curriculum framework through practice guides, literature reviews and a range of other resources and professional learning opportunities.

In Ireland, from 2011 to 2013, a nationwide initiative including on-site mentoring visits, cluster group meetings and seminars, helped to support the implementation of the curriculum framework in areas such as raising awareness of the role of children as active learners, the role of parents, and creating high-quality interactions. A more recent professional development programme aims to support staff understanding and implementing the curriculum framework through workshops, on-site support visits by a mentor and practice tasks for staff. Other professional development resources and materials aligned with the national curriculum framework were developed by expert groups, including self-evaluation tools, guides for action planning and examples of pedagogical strategies (e.g. mathematics in everyday experiences). Mentoring supports that use a curriculum framework practice guide, video observations, feedback and staff meetings are also available.

In Canada, it is common to provide professional development on curriculum implementation, particularly when the framework is somewhat recent. In Nova Scotia, for example, mandated professional development provides learning opportunities for reflection, discussion and application of principles and practices promoted in Nova Scotia’s curriculum framework. In 2015, New Brunswick embedded a mandatory professional development programme specifically focused on the curriculum framework for all staff employed in licensed ECEC settings. Additionally, pedagogical workshops, local communities of practice and several resources have been put in place.

Learning from countries: Delivery modes of professional development

In Australia, it is common to offer centre-embedded professional development. To assist settings in the implementation and development of professional development programmes, there is a range of resources and materials provided by the authorities. In the state of Victoria, for instance, additional funding is allocated to ECEC pre-primary centres depending on children’s socio-economic background. Funding can be used by ECEC centres for a range of validated programmes that include training for staff on cultural inclusion and trauma-informed practices.

In Canada, in many provinces and territories, early childhood consultants support ECEC settings in quality improvement, especially settings that receive public funding and adopt the quality standards. A variety of intervention models are used, including the use of standardised quality assessment tools to guide assessment and intervention. In Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Alberta, it is mandatory for designated ECEC settings to participate in these consultation programmes. In Quebec, most ECEC settings have access to consultants to enhance the provision quality, who provide a range of supports in order to support the quality of services, such as facilitation of meetings, support to engage with parents and the community, and help on the development of pedagogical tools and design of learning environments. In Ontario, pedagogical networks have been reinforced, and several professional learning resources accessible on line have been developed to respond to the needs of the ECEC sector. In British Columbia, resources have been created for staff interested in self-guided professional development, such as videos and newsletters. In Manitoba, an open-access online platform, functioning as a living textbook with a series of early childhood development modules, supports professional development and complements formal education and training programmes.

In Japan, it is also common for staff to regularly participate in centre-embedded professional development or training provided by respective local governments, universities and ECEC-related organisations through a range of delivery modes, such as guided observation of children, self-reflection and peer learning.

In Luxembourg, because initial education does not focus exclusively on ECEC, professional development is particularly important to support staff in implementing the national curriculum framework. Many different institutions offer a wide range of courses. Centre-embedded professional development has increased over the years, involving the entire staff of the setting. Although most of the professional development is face-to-face, there are also, for example, online courses. It is also common to facilitate exchanges between staff from other sites and promote on-site visits.

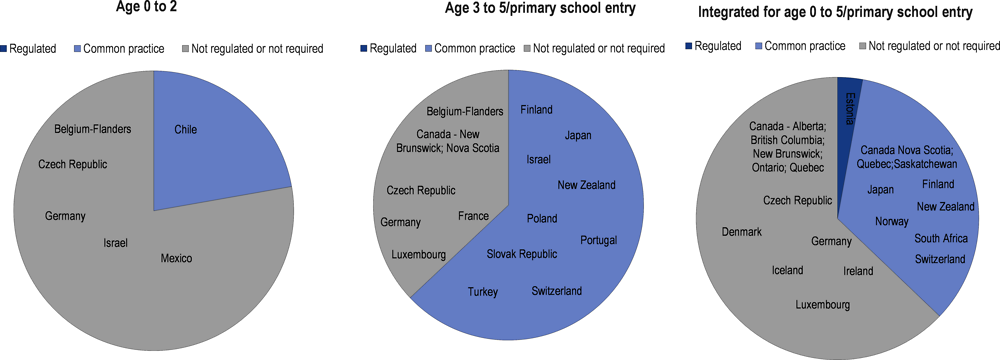

Formal recognition of participation in training and assessing the quality of professional development

The recognition and accreditation of professional development activities can be a valuable means to ensure quality, as it usually involves standards in terms of content, pedagogical strategies and instructor qualifications. Recognised professional development activities can also lead to certificates or diplomas that can bring opportunities for career progression. The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked countries and jurisdictions whether there were regulations for formal recognition and accreditation of professional development activities.

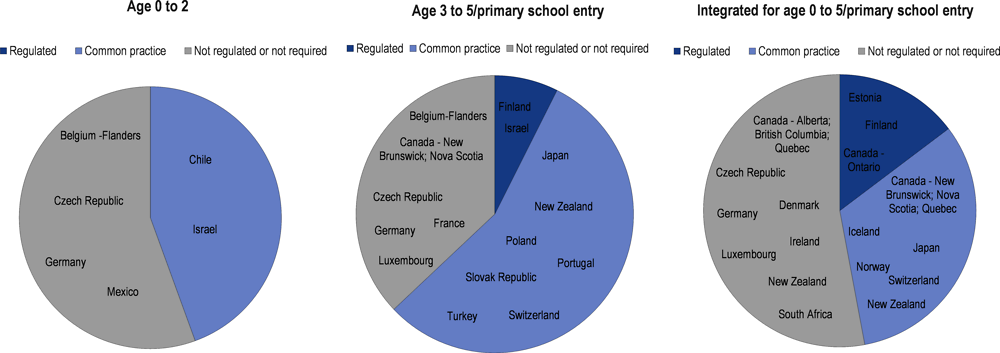

Regarding settings for children aged 0 to 2 years, no countries or jurisdictions require formal recognition and accreditation of professional development activities for teachers, although in two (out of eight), this is common practice (Figure 3.6). For assistants, a requirement is in place in one country, Chile, while in the remaining three countries and jurisdictions, there is no regulation or requirement (Figure C.3.3).

Regarding settings for children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry, formal recognition and accreditation of professional development activities for teachers are required in 3 out of 17 countries/jurisdictions, namely Israel, Portugal and Turkey. For example, Portugal provides formal accreditation of professional development activities for teachers working in the public sector through a national agency. Turkey also regulates formal accreditation of professional development. Concerning assistants, formal recognition or accreditation are common practice in New Zealand and the Slovak Republic.

Regarding settings for children aged 0 to 5/primary school entry, formal recognition and accreditation of professional development activities for teachers are required in 2 out of 19 countries/jurisdictions, namely Canada and Estonia. For assistants, in Canada (British Columbia) and in one setting in New Zealand, it is regulated. For example, British Columbia requires that all ECEC assistants continue to work towards their ECEC credential by completing a minimum of one course in a recognised early childhood development programme within their five-year certificate period. The accreditation of the programmes is at the central level.

The Quality beyond Regulations questionnaire also asked whether there were regulations or it is common practice to assess the quality of professional development. Assessment of the quality of professional development is mainly not regulated, but it is common practice for teachers in a number of participating countries and jurisdictions for settings for children aged 3 to 5 or 0 to 5/primary school entry, but less so for settings for children under the age of 3 (Figure 3.7). The quality assessment of professional development for assistants is, in general, less prevalent than for teachers (Figure C.3.4).

Learning from countries: Requirements to participate in professional development

While most participating countries and jurisdictions do not regulate the recognition and accreditation of professional development activities or the assessment of quality, several of them have requirements to participate in ongoing professional development activities. Countries may set a minimum of hours of participation in professional development or specific contents and topics, as, for instance, when a new curriculum is being introduced.

In nine provinces of Canada, there are minimum requirements for professional development. For example, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and British Columbia, ECEC staff are required to attend professional development to renew their certifications. In New Brunswick, new staff working in licensed ECEC settings must attend professional development specific to implementing the curriculum framework. In Quebec, home-based ECEC providers are required to complete six hours of professional development annually, with an additional requirement that half of the required hours focuses on child development and on the curriculum framework.

In Japan, required professional development includes training for newly appointed and mid-career teachers in public pre-primary settings. In 2009, the system for renewing educational personnel certificates was introduced with the goal to update pre-primary teachers’ knowledge and skills. Under this system, pre-primary teachers attend regulated courses and lectures provided by universities and other training institutions once every ten years to renew their certificates.

In Luxembourg, the introduction of compulsory hours of professional development has aimed to ensure that professional development is aligned with the curriculum framework. Goals and contents of professional development programmes are required to align with the curriculum.

In Switzerland, required professional development is used to introduce new topics and subject areas, namely, to implement a new curriculum (see Chapter 2), according to priorities set by cantons and local authorities. These courses are often subsidised or are free of charge.

Setting the conditions for participation in professional development activities

Participation in professional development is influenced by several conditions, such as funding opportunities and the use of incentives (Schilder, Broadstone and Leavell, 2019[46]). Work environment features, such as a positive organisational climate, agency in decision making, and time for professional development, are likely critical to staff participation in professional development (Bayly et al., 2020[47]; Bove et al., 2018[39]; Connors, 2019[41]). A respectful and trusting environment can be important for professionals to make the most out of professional development (Bayly et al., 2020[47]). Resources and time to fit the professional development programme into their schedules can impact responsiveness and the effectiveness of professional development interventions (Bayly et al., 2020[47]). Without financial support and incentives (Mowrey and King, 2019[48]), or without releasing time or using inflexible schedules, it can be hard for staff to engage in professional development. According to findings from TALIS Starting Strong, the three main barriers to participating in professional development across participating countries are: not enough staff to compensate for absences when attending training; cost; and conflicts with work schedules (OECD, 2020[2]).

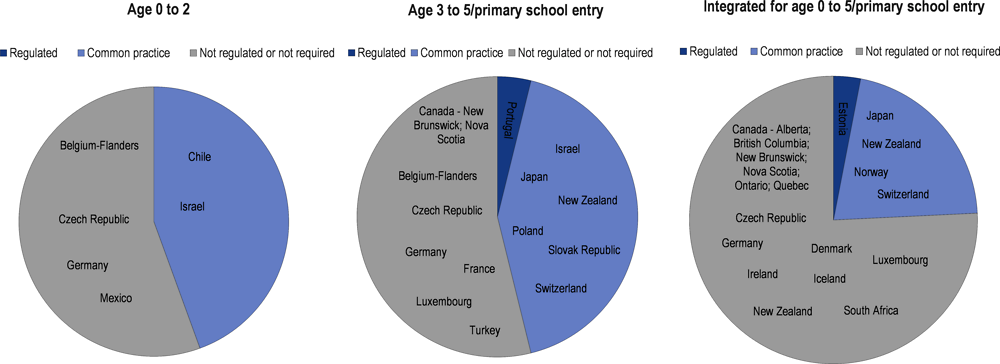

Granting release time during regular working hours for professional development activities can encourage greater engagement in professional development activities (OECD, 2020[2]). Across settings for children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry, releasing time for teachers to attend professional development is a common or required practice in most participating countries and jurisdictions. It is less frequent in settings for children aged 0 to 2 and 0 to 5/primary school entry (Figure 3.8). Teachers in France, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Turkey are supported by time entitlements. For assistants, time incentives to participate in professional development activities are not regulated or required in the majority of participating countries and jurisdictions (Figure C.3.5).

Learning from countries: Providing financial incentives to support participation in professional development

Offering adequate financial support can be crucial to support staff in their investments in professional development (OECD, 2020[2]). This support can be, for example, covering the costs related to professional development. Developing flexible, professional programmes that enable working and training at the same time can also facilitate participation (OECD, 2020[2]).

In Canada, provinces’ and territories’ governments provide several types of support for participation in professional development, which may be financial, in-kind, or funding to ECEC settings. For example, in British Columbia, professional development funding is available to support both teachers and assistants who are experiencing barriers to maintaining the required professional development hours to ensure their credentials. Funding is available for, but not limited to, tuition, books, tutoring, travel and occasional childcare costs. In Manitoba, a workplace pre-service training model has been introduced for teachers employed in the regulated ECEC sector. The setting receives funding so that the candidate can attend the training for 2-3 days per week and continue to receive their regular wages. The programme has helped to retain qualified staff in centres. In Quebec, licensed ECEC settings receive a subsidy to determine the type of professional development aligned with staff needs. Alberta offers several grants to both teachers and assistants so that they can attend approved conferences and workshops.

In Japan, it is common for staff to receive reimbursement and coverage of costs associated with official professional development.

Assessing professional development needs and barriers to participation

The aim of assessing professional development programmes is to determine their effectiveness and relevance. As programmes are designed for staff with different types of initial preparation, working in different roles and with different levels of experience, assessment of the programmes is important to ensure that coherent pathways for skills development are offered (OECD, 2020[2]). In addition, designing such pathways calls for the assessment of staff needs and the barriers to participation in professional development.

Experts have long emphasised that one key aspect for the effectiveness of professional development interventions is the alignment between professional development and professionals’ needs and interests (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Peleman et al., 2018[36]). Professional development that targets staff needs can be pivotal for making it meaningful and relevant for participants. Several studies have shown, in fact, that teachers find it important for professional development programmes to address their needs, advocating for training opportunities relevant to their everyday practices (Barnes, Guin and Allen, 2018[49]; Linder et al., 2016[50]). However, analyses using the TALIS Starting Strong data found a positive relationship between receiving training and perceived needs for further professional development (OECD, 2020[2]). This might reflect the effectiveness of training in stimulating the interest of staff to improve their knowledge and skills in this area, including by increasing awareness about the complexity of the topics. Better understanding staff needs and interests, while also aligning the supply of professional development with policy objectives, can be a starting point to develop professional development that is both meaningful and stimulating.

The delivery of professional development also needs to address some of the barriers to participation. Proposing programmes that are meaningful to staff is important, but other barriers, such as programmes’ geographical location and costs, beyond the need to find time, also play a big role (Linder et al., 2016[50]). Like needs and interests, barriers to professional development can be diverse; they can relate to logistics, working conditions, personal factors, or a combination of all of the above. Assessing barriers regularly and in the specific context can be another important step to developing professional development initiatives likely to engage staff.

The Quality beyond Regulations questionnaire asked whether, for both teachers and assistants, the assessments of needs, barriers to participation and quality of professional development are required, common practice or not regulated. The assessment of staff professional developmental needs is not often regulated across participating countries and jurisdictions. It is, however, common practice for teachers in a number of countries and jurisdictions, particularly for those working in settings with children aged 3 to 5/primary school entry (Figure 3.9). This is less the case for assistants (Figure C.3.6).

Similarly, the assessment of barriers to participation in professional development is mainly not regulated or not required (Figure 3.10). It is common practice in a small number of countries for teachers. For assistants, barriers to participation in professional development is mainly not regulated and very rarely common practice (Figure C.3.7).

Learning from countries: Monitoring tools for assessing professional development needs

Relying on different sources of information can ensure that relevant professional development opportunities are available to meet staff needs, although different approaches may need to be co-ordinated. Assessment of staff needs can be done at the level of the ECEC setting, at a national or regional level and more generally through monitoring systems targeting ECEC settings and staff.

In Ireland, regulatory and inspection systems have been progressively changed to strengthen quality assurance, including on issues related to professional development. Education-focused inspections were introduced for pre-primary education settings, which among other things, assess the need for professional development in many areas. Inspectorates help to identify challenges and areas of need and make specific recommendations to support quality improvement through professional development. Agreements are in place with the national quality development service to provide support to ECEC settings. In addition, regular updates on regulatory compliance are provided to initial education institutions. At the national level, national agencies monitor professional development programmes related to the curriculum framework.

In Luxembourg, based on staff self-assessment needs and joint discussions, ECEC leaders are responsible for defining the training courses that are important and necessary. In the last three years, for example, the number of centre-embedded professional development courses has increased significantly as a result of self-assessment processes. In addition, because of assessed needs in curriculum implementation, professional development opportunities have grown for an increased number of subject areas. At the regional level, visits by regional officers are carried out to monitor the implementation of the national curriculum framework and to make recommendations related to professional development.

In Switzerland, staff and leaders in each setting select topics for professional development according to their self-assessed needs. Regular exchanges between experts and staff, facilitated by professional associations, also contribute to assessing professional development needs in the field. For instance, based on professional exchanges and identified needs, an ECEC association has introduced new professional development courses. Additionally, at the regional level, inspection visits may identify professional development needs that drive new professional development initiatives in the canton or commune. The city of Zurich, for example, based on identified needs, has developed a professional development programme for both teachers and assistants that includes topics related to the curriculum, in addition to cross-sectional topics, such as infant education and care, educationally-oriented work and collaboration with parents.

Staff working conditions have an impact on staff well-being, in particular on their emotional well-being, which in turn has an effect on their practices with children and their performance at work. Overall, staff working conditions and well-being can be important drivers of process quality. The importance of staff working conditions for process quality is now well established in the scientific literature and across a wide variety of contexts. In a nutshell, the evidence shows that better working conditions, such as salaries, a positive organisational climate and well-being at work, go hand in hand with higher process quality (Penttinen et al., 2020[51]; Hu et al., 2017[52]; Hu et al., 2017[53]; Shim and Lim, 2019[54]).

Working conditions include various aspects, such as earnings, job security and career prospects, workload, and the quality of the working environment at the ECEC centre. Working conditions contribute to the demands employees are exposed to (i.e. workload, number of children in the group or classroom) and the resources they have at their disposal (i.e. professional autonomy, training) or the rewards they receive for their efforts (i.e. salaries, career progression) (OECD, 2020[2]). A lack of reciprocity between effort and resources or reward can lead to stress, while good alignment between the two contributes to staff well-being (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007[55]; Bakker and Demerouti, 2016[56]). Research shows that ECEC staff’s emotional well-being is related to the quality of their interactions with children (de Schipper et al., 2008). Furthermore, working conditions and well-being determine the quality of the job (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[57]), which might, in turn, be a reason for candidates to join the sector, and for existing staff to stay or leave, finally determining the capacity of the sector to retain high-quality staff.

Earning and contractual status

Salaries are one crucial component of working conditions. Research provides supporting evidence that salary is important for attracting and retaining ECEC staff. Several studies also find a relationship between salaries and the quality of staff’s interactions with children, with better-paid staff having more sensitive interactions with children and fewer detached ones (Cassidy et al., 2017[58]; Hu et al., 2017[52]). This relationship has also been found in the case of home-based settings (Eckhardt and Egert, 2020[14]). On top of the salary itself, it seems that teachers’ perceptions regarding the fairness of their wage are also positively correlated with process quality (Cassidy et al., 2017[58]).

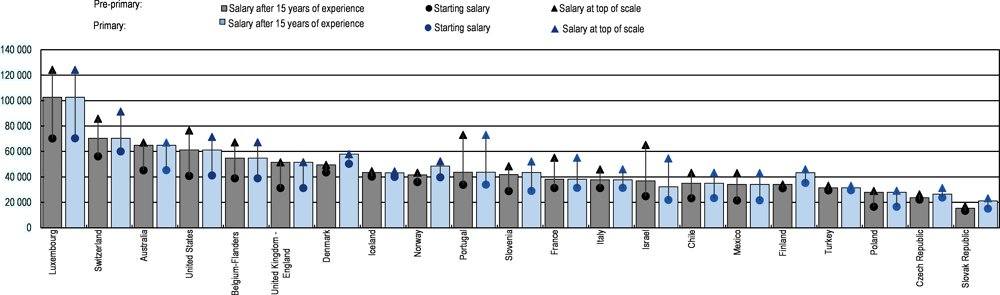

Results from TALIS Starting Strong further show that staff’s low satisfaction with salaries associates with stress and disengagement with work (OECD, 2020[2]). In public institutions, the statutory salaries of pre-primary teachers are similar to those of primary teachers in many OECD countries, but not all of them (Figure 3.11). However, these data do not provide the full picture of salaries in the sector. Assistants’ salaries can be low and not necessarily regulated, and there may also be differences in salaries between the private and public sectors. Finally, there is a lack of comparable data across countries on salaries of staff working with children under the age of three.

Job security, understood as a high probability to maintain employment, is an important reward for staff work (OECD, 2020[2]) and is a major determinant of individual well-being (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[57]). Job security can help attract new staff to the sector. The contractual status and, in particular, having permanent employment, contribute to job security. Permanent contracts can help retain existing staff in the sector or in ECEC centres, preventing staff turnover, which is a common challenge in the ECEC sector (OECD, 2019[8]; 2020[2]). When ECEC jobs are stepping stones towards other education or social jobs, the ECEC sector can benefit from good candidates but might encounter difficulties in ensuring stable, high-quality services because of high turnover. This issue can be addressed, to some extent, by employment with permanent contracts.

The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked countries and jurisdictions about policy measures in place concerning staff contract types. In the vast majority of settings, there are no policy measures or regulations related to the contractual conditions for teachers and assistants (Figure C.3.8). These measures are in place in approximately 15% of settings for children aged 0 to 2 and 0 to 5, and in less than 25% of settings for children aged 3 to 5. However, ECEC staff may fall under general labour market conditions that are not necessarily reflected in the Quality beyond Regulations questionnaire. Data from TALIS Starting Strong show that among participating countries, between 70% in Chile to 90% of ECEC staff in Norway have a permanent contract (OECD, 2019[8]).

Career progression opportunities

Opportunities for career progression are another important aspect of working conditions that are likely to affect the attraction and retention of the workforce. Career progression can help staff remain engaged with the profession and feel that their efforts are rewarded, which can improve job satisfaction and work-related well-being (OECD, 2020[2]). However, in the ECEC sector, as in the school sector, traditional careers are often “flat”, with few opportunities for advancement or diversification, and staff who would like to progress in their career might choose to leave the job. Progression can involve salary increase, new responsibilities through changing roles, such as changes from assistants to teachers or teachers to leaders, or specialisation in certain tasks along the professional career.

In many countries, salaries after 15 years are very similar to those at the beginning of an ECEC professional’s career. There are possibilities, however, for salary progression in some of the settings in Belgium (Flanders), Israel, Luxembourg, Portugal, Switzerland and the United States (see Figure 3.11). Policies can support career progressions by setting measures and regulations for promotions and increased responsibilities adapted to the organisation of the ECEC sector and its different roles.

The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked whether countries and jurisdictions have measures or regulations to support promotions or wage increases associated with staff performance. In most settings, participating countries and jurisdictions reported that there were no measures to support promotions for teachers, and even less so for assistants (Figure 3.12, Figure C.3.9). Countries may, however, not have reported on measures covering the whole education workforce or the public sector, and not specifically for ECEC staff. Regarding teachers, Australia, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Switzerland have measures to support career progression schemes in some of the settings. Regarding assistants, such measures are in place in some of the settings in Australia, Chile, France, Portugal and the Slovak Republic.

Learning from countries: Measures to support promotions or wage increases

In Australia, teachers and assistants can progress in their careers through salary increases based on their work performance and length of service. Regulations on working conditions and salaries are set either nationally or based on state requirements.

In Finland, career progression is under the responsibility of municipalities that set systems for salary increases based on staff performance.

In France, teachers can reach higher positions and leading roles, such as school directors or educational advisers. Staff can also progress to specialised teaching roles, for instance, for working with children with additional needs.

In Japan and Switzerland, teachers and leaders in the public sector can be promoted or have an increase in salary according to their work performance.

The recognition of skills acquired on the job through formal systems can also facilitate career progression (OECD, 2020[2]). For instance, in Canada, in Nova Scotia, a recognition-of-prior-learning process for staff is in place. The initiative has developed a competency profile that specifies the expected skills and knowledge staff should demonstrate, and the assessment is based on exams and scenario-based interviews. In Quebec, there are also opportunities for formal recognition of prior qualifications, especially for staff having acquired some experience outside Quebec in order to address labour shortages.

Allocated time to perform various tasks

The quality of a working environment also includes non-economic aspects of jobs, such as the nature and content of the tasks at hand and working-time arrangements (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[57]). A heavy workload with multiple ongoing tasks that demand persistent physical, psychological or emotional efforts can lead to less engagement and commitment, with detrimental effects on classroom practices (Ansari et al., 2020[59]). There is empirical evidence suggesting that excessive demands and work overload (i.e. high demand, not enough time, short of assistance) are negatively associated with process quality (Aboagye et al., 2020[60]; Aboagye et al., 2020[61]; Chen, Phillips and Izci, 2018[62]).

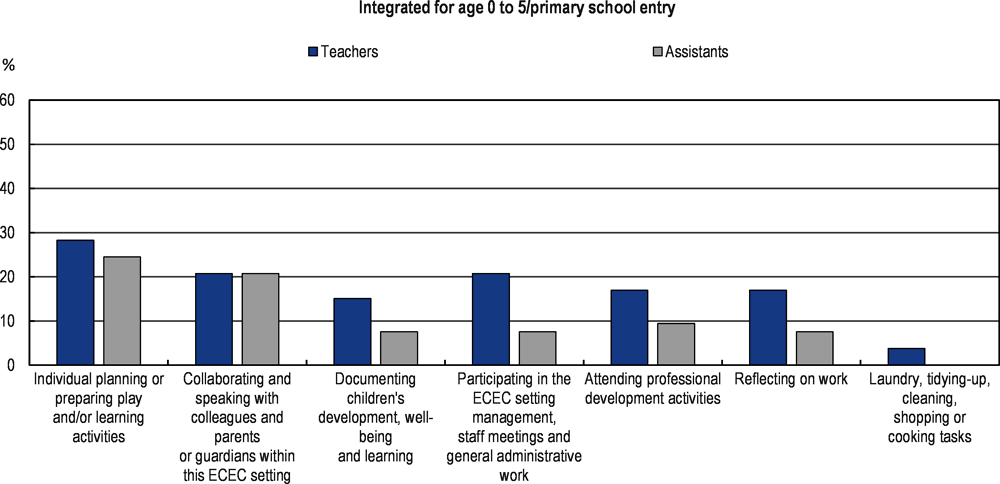

In the ECEC sector, staff’s work includes a variety of responsibilities and activities that go beyond working directly with children, including individual planning or preparing play and learning activities; collaborating and speaking with colleagues and parents or guardians; documenting children’s development, well-being and learning; attending professional development activities; and administrative tasks. The allocation of hours to different tasks to ensure that staff can devote sufficient time to each one, including tasks without children, is important for staff well-being (OECD, 2020[2]).

The Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire asked countries and jurisdictions whether staff are given protected time to carry out seven different types of tasks to be performed without children. Teachers, across settings for all age groups, are more likely to have protected time than assistants for all tasks assessed, with the differences being substantial in most tasks (Figure 3.13). For teachers, protected time is more frequent in settings for children aged 3 to 5, with 40-50% of them having protected time for the majority of tasks, and less so in settings for children aged 0 to 5, with 30% of teachers or less having protected time for the various tasks. Among the activities considered, there is not much variation, except for laundry and cleaning, which is rarely accompanied with protected time, even for settings for children aged 0 to 2 (Figure C.3.10).

Countries and jurisdictions differ in their regulations with regard to protecting time for activities to be performed without children. Some have policies to protect time for a wide range of activities without children. This is the case for settings for children aged 3 to 5 in the Czech Republic, Finland, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Turkey for teachers, and in the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic for assistants as well. In settings for children aged 0 to 5, protecting time for a wide range of activities without children is in place in Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg and Norway for teachers, and in Luxembourg for assistants (Figure 3.14, Figure C.3.11).

Leadership is pivotal for organisations’ success and a key driver of potential change and quality improvement in educational settings. Leaders can help build a climate of trust, collaborative and caring relationships, and a sense of belonging (Brinia, Poullou and Panagiotopoulou, 2020[63]; Heikka, Halttunen and Waniganayake, 2018[64]). It is expected that leaders act as promoters of the quality of ECEC settings, providing resources and conditions for staff to develop high-quality practices. Findings from TALIS Starting Strong show that in centres in which leaders set a clear vision, staff report a stronger sense of self-efficacy (OECD, 2020[2]). Importantly, effective leadership can play a significant role in staff engagement in professional development initiatives (Jensen and Iannone, 2018[40]; Keung et al., 2020[65]; Page and Waniginayake, 2019[66]).

Leadership practices can focus on pedagogical dimensions (e.g. staff-child interactions, staff motivation for achieving the centre goals, community and parental/guardian engagement), as well as on management and administrative tasks (e.g. hiring staff, managing budgets) (Daniëls, Hondeghem and Dochy, 2019[67]; Douglass, 2018[68]). While different dimensions of leadership are important for quality, pedagogical leadership, depending on the context and situation, can play an important role in shaping everyday classroom practices (Halpern, Szecsi and Mak, 2020[69]). Recent research suggests that pedagogical leadership practices that strategically focus on children’s educational processes and foster trust, collective understanding and responsibility for excellence, are related to high-quality, teacher-child interactions (Ehrlich et al., 2019[3]).

A literature review has highlighted that a leader’s ability to communicate and maintain good relationships with his/her staff and the community, providing frequent feedback and recognising accomplishments, are key factors for effective leadership (Daniëls, Hondeghem and Dochy, 2019[67]). Additionally, leaders should take into consideration staff needs and expectations, providing them with opportunities for skill development, while creating adequate work conditions through the establishment of a respectful, trusting and safe environment (Bove et al., 2018[39]; Page and Eadie, 2019[70]).