Chapter 13. India

Support to agriculture

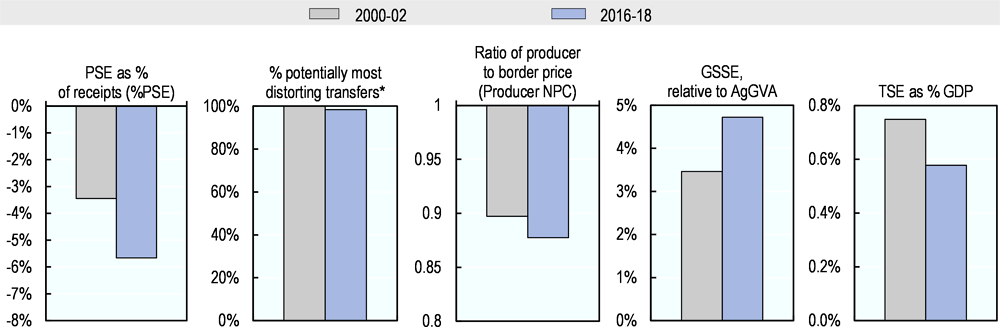

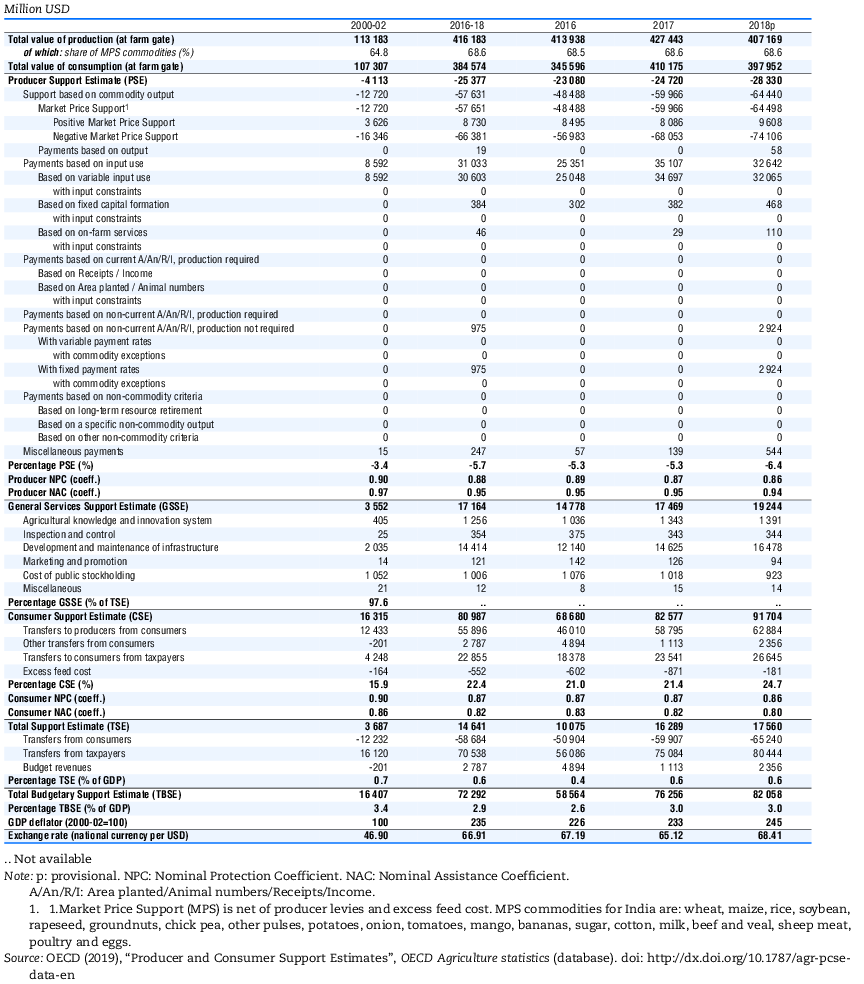

Support to producers in India is composed of budgetary spending corresponding to 7.2% of gross farm receipts and positive and negative market price support (MPS) of +2% and -14.9% of gross farm receipts. Overall, this leads to negative net support of -5.7% of gross farm receipts (%PSE) in 2016-18. The negative value of the PSE means that domestic producers were implicitly taxed, as budgetary payments to farmers do not offset the price-depressing effect of complex domestic regulations and trade policy measures, which often lead to producer prices that are below comparable international market levels. Budgetary transfers to agricultural producers are dominated by subsidies for variable input use, such as fertilisers, electricity, and irrigation water. In turn, public expenditures financing general services to the sector (GSSE) correspond to just half of the subsidies for variable input use. Total budgetary support (TBSE) is estimated at 2.9% of GDP.

Mirroring the farm price-depressing effect on producers, the policies provide implicit support to consumers. Policies that affect farm prices, along with food subsidies under the Targeted Public Distribution System, reduced consumption expenditure by 22.4% (%CSE) on average across all commodities in 2016-18.

Main policy changes

The central government increased the Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) for all crops covered by the system. It also introduced additional schemes (including a Price Support Scheme and a Price Deficiency Payment Scheme) to encourage the procurement of crops other than grains and cotton, such as pulses or oilseeds. In addition, tariffs for several key commodities were increased, including chickpeas, sugar and wheat.

The central government adopted an Agricultural Export Policy framework, which recommends avoiding the application of export restrictions on most organic and processed agricultural products.

To address farm indebtedness, several states announced in 2017 and 2018 support packages for farm loan waivers, reaching an estimated total of INR 1 846 billion (USD 26.8 billion). Existing estimates highlight, however, that overall concerned states had actually allocated only 40% of the announced amount by December 2018.

The 2019-20 Interim Budget introduced the Income Support Scheme, which is an unconditional cash transfer payment to small-scale farmers, with landholdings of up to 2 hectares.

Assessment and recommendations

-

The measurement of support related to agricultural policies (PSE) highlight one of the fundamental issues in Indian agriculture: that for many products and over most of the period reviewed Indian farmers have been receiving prices that are lower than the prices prevailing on international markets. The central government should continue the initiatives to reduce domestic marketing inefficiencies and work closer with states and Union Territories (UTs) to thoroughly reform regulations and to foster more efficient and competitive markets. Marketing provisions should be adopted in a harmonised and consistent way across states (building on initiatives underway such as the model marketing act or the electronic national agricultural market portal) and should be synchronised with any Minimum Support Price (MSP) system reforms through coherent plans.

-

India has become an important agro-food exporter in a number of commodities. The 2018 Agricultural Export Policy framework recommending to avoid the application of export restrictions for organic and processed agricultural products is an important step towards reducing uncertainty and transaction costs throughout supply chains. An extension to all agro-food products should be considered to create a stable and predictable market environment. Reducing tariffs and relaxing other import restrictions is also key for a predictable market environment and for tapping into the potential of imports to contribute to diversification of diets and to improving food security across all its dimensions. Together with domestic marketing reforms, moving away from export and import restrictions has the potential to provide farmers and private traders with the right incentives to invest in supply chains.

-

The large share of employment in agriculture compared to its GDP contribution reflects the persistent productivity gap with other sectors, which translates into low farm incomes. In the short to medium-term, direct cash transfers targeting the incomes of poorest farmers can back their adjustment to changing market conditions. In the long term, significant structural adjustments need to occur in India involving the transition of farm labour to other activities and a process of consolidation towards farm operations sufficiently large to benefit from economies of scale. Continued reforms in land regulations need to be complemented by investments in key public services to the sector (such as education, training, infrastructure) and the broader enabling environment (including financial services).

-

Environmental pressures are starting to loom large and risk jeopardising long-term productivity growth. Generating savings by scaling back variable input subsidies can be used to train farmers in an efficient and sustainable use of such inputs, by ensuring extension systems focus more on climate change, sustainability, and digital skills. Responding to challenges posed by climate change also calls for further investments in the agricultural knowledge system and in the institutional framework needed to ensure appropriate concertation and consistency among all stakeholders.

-

India has also made significant progress in recent years in eliminating waste and inefficiencies in the food distribution system and these efforts should continue. The Government of India should continue the experimental replacement of physical grain distributions by direct cash transfers, and expand and adjust in light of experiences gained.

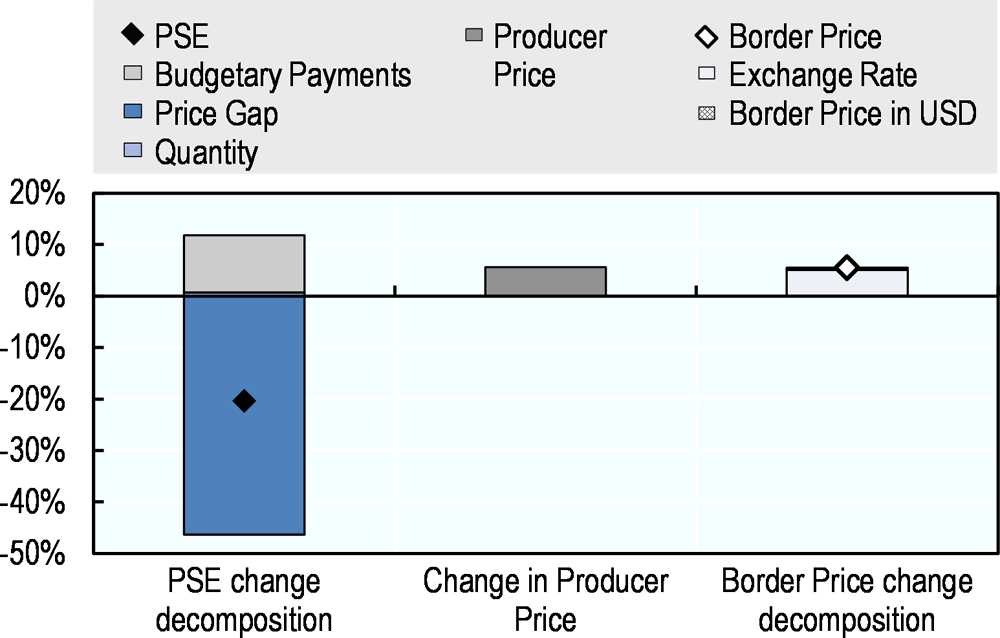

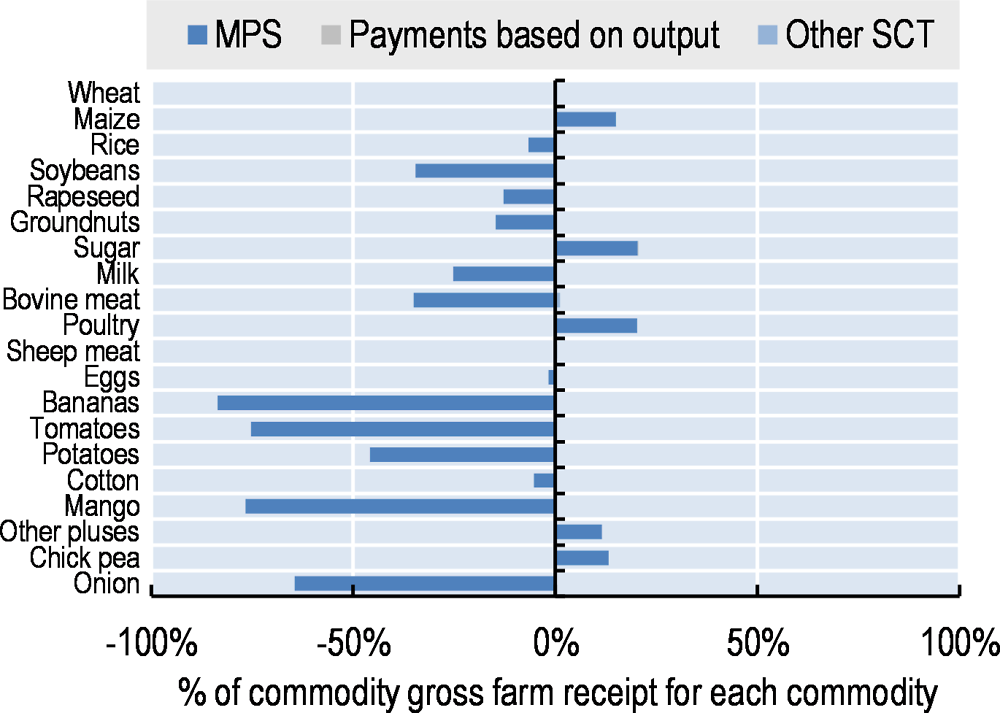

Support to producers remained negative throughout 2000-18, but fluctuated markedly over this period. It averaged -5.7% in 2016-18. A positive MPS for maize, sugar, chickpea, other pulses and poultry, together with large input subsidies, only partly compensate the large negative MPS for the majority of exported products in 2016-18, worth -14.9% of gross farm receipts. Policies for these commodities over the period covered – whether impeding exports or depressing producer prices through domestic market regulations – led to prices received on average by farmers 12% lower than reference prices in 2016-18 (Figure 13.1). Virtually all gross producer transfers (whether positive or negative, i.e. expressed in absolute terms) are implemented in forms that are potentially most production and trade distorting, a consistent pattern since 2000-02. Producer support slightly decreased year-on-year (i.e. has become more negative), mainly due to depreciation of the Indian Rupee more than offsetting some increase in producer prices (Figure 13.2). Single commodity transfers (SCTs) mirror the MPS pattern, with most commodities being implicitly taxed in the range between 2% and 84% of commodity receipts (Figure 13.3). At 4.9% in 2016-18, expenditure for general services (GSSE) relative to agriculture value added increased compared to 2000-02, contributing to an overall positive total support estimate (TSE) of 0.6% of GDP.

Contextual information

India is the seventh largest country by land area (2.97 million km2) and the second most populous after China with over 1.3 billion people (Table 13.2). While the share of urban population continued to increase over the past decade, more than two thirds of the population still live in rural areas. At just 0.15 ha per capita, agricultural land is very scarce.

Agriculture still accounts for 43% of employment, but its 16% share in GDP indicates that labour productivity remains significantly lower than in the rest of the economy. The productivity gap is also reflected in the evolution of farm incomes, which correspond to less than one-third of non-agricultural income. Value added has been gradually shifting away from agriculture, but mostly into services rather than manufacturing. Services led economic growth over the last 15 years, playing a more important role in India’s economic development than in most other major emerging economies.

Indian agriculture is continuing to diversify towards livestock and away from grain crops. While grains and milk remain dominant, there has been a gradual change in the composition of production to other crops – such as sugar cane, cotton, fruit and vegetables – as well as certain meat sub-sectors. Livestock output growth has been faster and less volatile than crop production. The sector continues to be dominated by a large number of small-scale farmers, as the national average operational holding size has been in steady decline.

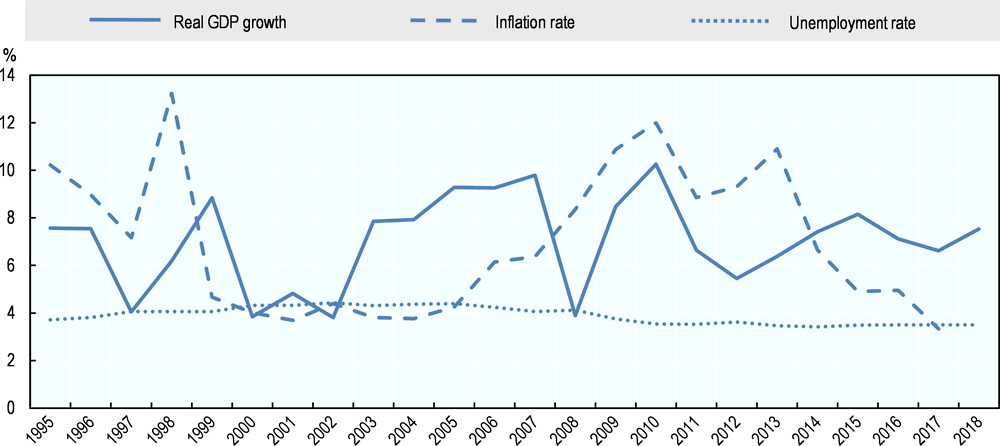

With real GDP growth averaging 7.1% in 2016-18, India is now among the fastest-growing G20 economies. Recent reforms such as the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the inflation-targeting monetary policy framework, and the further liberalisation for foreign investments have improved the business environment. The low unemployment figures hide significant degrees of informal employment (Figure 13.4).

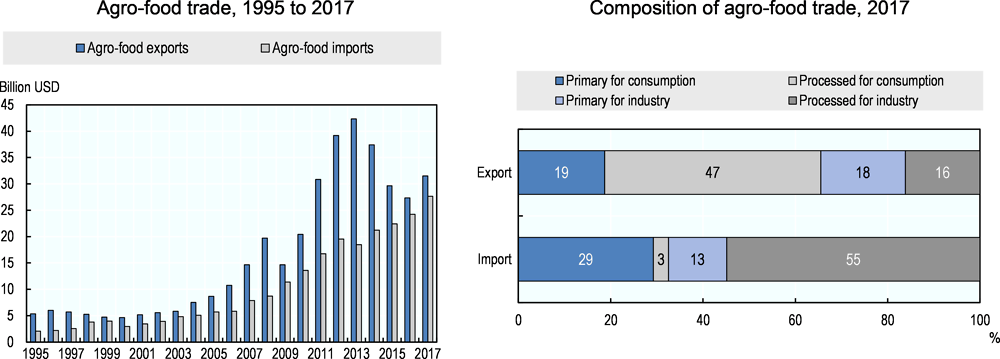

India has consistently been a net agro-food exporter over the last two decades, but agro-food imports have been steadily increasing since 2007, while exports have declined consistently between 2013 and 2016. Products for direct consumption dominate agro-food exports, representing 66% of the total in 2017. Processed products for further processing by domestic industry are the key import category, accounting for 55% of total agro-food imports (Figure 13.5).

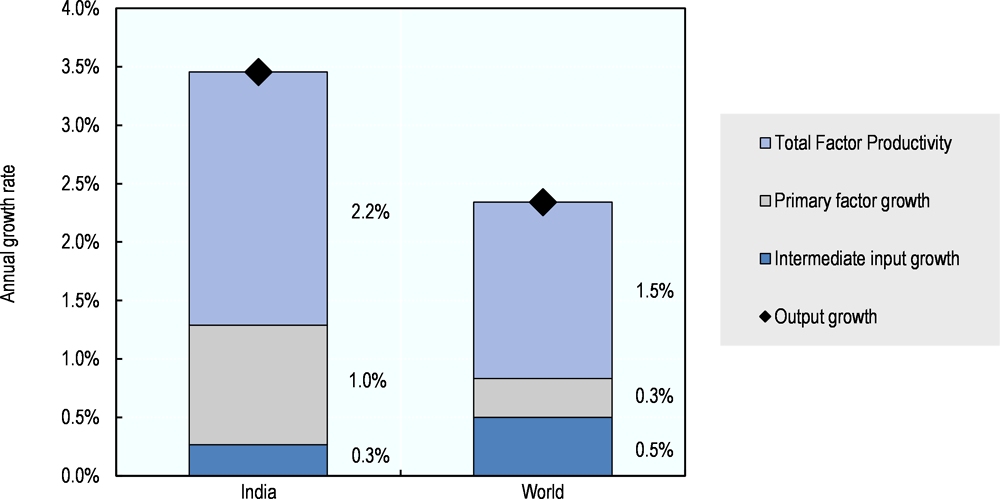

Agricultural output growth in India averaged 3.5% in 2006-15, more than one-third above the world average (Figure 13.6). This has mainly been driven by an important increase in total factor productivity (TFP) at 2.2% per year, backed by technological progress in the form of improved seeds and better infrastructure (including irrigation coverage, road density, and electricity supply).

However, the sustained growth in agricultural output has been exerting mounting pressures on natural resources, particularly land and water. This is reflected in the nutrient surplus intensities at the national level and the share of agriculture in total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which are much higher than the average for OECD countries. Livestock rearing is the main source of GHGs (Table 13.3).

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Over the past several decades, agricultural policies have sought to achieve food security, often interpreted in India as self-sufficiency: seeking to ensure that farmers receive “remunerative” prices, while at the same time safeguarding the interest of consumers by making food available at affordable prices. The set of policies directly relating to agriculture and food in India consist of five major categories: i) managing the prices and marketing channels for many farm products; ii) making variable farm inputs available at government-subsidised prices; iii) providing general services for the agriculture sector as a whole; iv) making certain food staples available to selected groups of the population at government-subsidised prices; and v) regulating border transactions through trade policy. In addition and more recently, environmental measures concerning agriculture have been gaining prominence, (OECD/ICRIER, 2018[2]) provides further information on the set of policies.

In India, states have constitutional responsibility for many aspects of agriculture, but the central government plays an important role by developing national approaches to policy and providing the necessary funds for implementation at the state level. The broad policy guidelines are currently set within a framework of three-year action agendas, prepared by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog, a policy think tank of the Government of India).1 The central government is responsible for some key policy areas, notably, for international trade policies and for overseeing the implementation of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) of 2013.

Policies that govern the marketing of agricultural commodities in India – from the producer level to downstream levels in the food chain – include the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) and the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts. Through these acts, producer prices are affected by regulations influencing pricing, procuring, stocking, and trading of commodities. Differences exist among states in the status of their respective APMC Acts and in how these acts are implemented. The electronic portal (electronic national agricultural market, eNAM) initiated in 2016, and the 2017 model Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act – shared with state governments as a recommendation for adoption – aim to gradually encourage a single national agricultural market.

Based on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the central government establishes a set of Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for 24 crops each year. It can also provide a bonus payable above and over the MSP for some crops, as can do state governments. The national and state-level agencies operating on behalf of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) buy wheat, rice and coarse grains through open-ended procurement at MSP. A number of other agencies can buy pulses, oilseeds and cotton at MSP, and some perishable agricultural and horticultural commodities without MSP are also procured. However, procurement under the price support scheme has been effectively operating mainly for wheat, rice and cotton and only in a few states.

On the input side, major policies enable agricultural producers to obtain farm inputs at low prices. The largest input subsidies are provided through policies governing the supply of fertilisers, electricity, and water. Other inputs are also supplied at subsidised prices, including seeds, machinery, credit, and crop insurance. In recent years, loan debt waivers have been implemented across several states.

In the area of general services, expenditures are dominated by the development and maintenance of infrastructure, particularly related to irrigation. Public expenditures for public stockholding and related to the agricultural knowledge and innovation system are also significant.

Public distribution of food grains operate under the joint responsibility of the central and state governments. The Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) operates under the NFSA in all states and Union Territories (UTs). A set of Other Welfare Schemes (OWS) also operate under the NFSA. The central government allocates food grains to the state governments and the FCI transports food grains from surplus states to deficit states. The state governments are then responsible for distributing the food grain entitlements, i.e. allocating supplies within the state, identifying eligible families, issuing ration cards, and distributing food grains mainly through Fair Price Shops.

India’s Foreign Trade Policy – formulated and implemented by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) – is announced every five years, but it is reviewed and adjusted annually in consultation with relevant agencies. The current policy applies until 2020. India’s Basic Customs Duty (BCD) (also known as the “statutory rate”) is agreed at the time of approving the annual budget.

India has managed for several decades its agricultural exports through a combination of export restrictions, including export prohibitions, export licensing requirements, export quotas, export duties, minimum export prices, and state trading requirements. The application or elimination of such restrictions could be changed several times per year, taking into account concerns about domestic supplies and prices.

Regarding export subsidisation in agriculture, the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) – under the responsibility of the Ministry of Commerce & Industry (MOCI) – has provided in recent years financial assistance to exporters in the form of transport support.2

India ratified the Paris Agreement on Climate Change one year after the submission of its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), on 2 October 2016. The INDC – which became its NDC – includes a commitment to reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 33-35% by 2030 below 2005 levels, but specifies that this commitment does not bind India to any sector specific mitigation obligation or action (Climate Action Tracker, 2018[3]).

As concerns agriculture, India’s NDC has a strong focus on climate change adaptation, as addressed in several of the central government’s main programmes for agriculture (entitled “missions”). These include, among others, the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture; the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana mission promoting organic farming practices; the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana mission promoting efficient irrigation practices; or the National Mission on Agricultural Extension & Technology.

Domestic policy developments in 2018-19

Domestic price support policies

The central government raised the Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) throughout 2018 in its effort to achieve the 2017-stated goal of doubling farmers’ incomes by 2022. On 1 February 2018, when presenting the 2018-19 Union Budget, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) first announced an MSP valued at 150% of the cost of production for all kharif3 crops. In July 2018, the central government approved this MSP hike and clarified that the cost of production considered represents the cost of all inputs plus the imputed cost of family labour. For instance, this implied a raise by 16% to INR 1 700 per quintal (USD 248 per tonne) for maize; by 13% to INR 1 750 per quintal (USD 255 per tonne) for non-basmati rice; and by 11% to INR 3 399 per quintal (USD 495 per tonne) for soybean (GOI, 2018[4]; AMIS, 2018[5]; GAIN-IN8086, 2018[6]).

On 3 October 2018, the central government also raised the MSPs for 2018-19 rabi crops that will be harvested and marketed during the marketing year 2019-20. This represents an increase by 6% for wheat to INR 1 840 per quintal (USD 248 per tonne); by 5% for chickpea to INR 4 620 per quintal (USD 670 per tonne); and by 5% for rapeseed and mustard to INR 4 200 per quintal (USD 610 per tonne) (GOI, 2018[7]).

In response to decreasing sugar prices between October 2017 and May 2018, the central government increased in July 2018 the Fair and Remunerative Price for sugar (i.e. the minimum price sugar mills pay to sugar cane farmers) by 8% to INR 275 per quintal (USD 39.9 per tonne) for the 2018-19 marketing year (GAIN-IN8115, 2018[8]). In recent years, sugar mills have often fallen short in how much of the full FRP they pay to sugar cane producers. As part of a 2018 support package for sugar producers and sugar mills, the central government aims to support mills address this shortfall (called cane price arrears) through direct payments to farmers, soft loans to mills through banks, or various border measures (see details in next sections).

Stockholding policies

In addition to the MSPs hikes, the central government introduced in September 2018 the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Yojna (PM-AASHA) programme. The programme has three sub-schemes: i) a Price Support Scheme (PSS); ii) a Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS); and iii) a Private Procurement & Stockist Scheme (PDPS). The three components are separate from any other existing schemes for the procurement of rice, wheat, coarse grains, cotton and jute. PM-AASHA aims at covering existing gaps in these procurement schemes by providing a menu of additional compensation mechanisms. Under the Price Support Scheme (PSS), state governments take a proactive role in the procurement of pulses, oilseeds and copra from farmers, which is led by central agencies and is fully funded by the central government. The Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS) covers all oilseeds for which an MSP is notified. A direct payment of the difference between the MSP and the selling/modal price is made to pre-registered farmers selling the produce in the notified market yard through an auction process. The payments are to be done directly into the registered bank accounts of farmers. The sub-scheme does not foresee actual physical procurement of crops as farmers would be paid the difference between the MSP price and sale/modal price on disposal in the notified market. Under the Private Procurement & Stockist Scheme (PDPS), states would also have the option to roll out private sector participation in procurement operations; no operational pilots are currently running under the PDPS (GOI, 2018[9]; NITI Aayog, 2018[10]).

An increased procurement of pulses was one of the key stated policy objectives during 2017-18. The procurement of pulses has been extended through the PM-AASHA programme at the end of 2018, aiming to reinforce the existing Market Intervention Scheme and Price Support Scheme (MIS-PSS). Existing estimates highlight that the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Ltd. (NAFED) purchased about 4.4 million tonnes of pulses in 2017-18 (about 18% of the estimated 24.5 million tonnes produced), primarily from large farmers with marketable surplus. Under the PSS scheme of the PM-AASHA, proposals for procurement have been approved at the end of 2018 in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, but these have not yet been reported as operational (Economic Times, 2018[11]; Live Mint, 2018[12]).

In June 2018, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) approved the creation of 3 million tonnes of annual sugar buffer stock starting 1 July 2018. Instead of buying sugar from mills, the government will finance the cost of storage at mill-owned warehouses. The buffer stock is subject to revision, depending on prevailing prices and sugar supply in the market (GAIN-IN8115, 2018[8]).

Subsidies for variable inputs use

Phase I of the Pan-India rollout of Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) for fertiliser subsidy payments – initiated in 2016 – was reported as completed at the end of March 2018. Under the fertiliser DBT system, the full fertiliser subsidy has started to be paid on a weekly basis to fertiliser companies through an automated system, based on the actual fertilisers sales made to farmers at the points of sale (GOI, 2018[13]).

To address farm indebtedness, in 2017 and 2018, several states announced support packages for farm loans write-offs, through which local governments reimburse the lending institutions the implementation of the debt waivers. The loan waiver announcements primarily concern the states of Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, for an estimated total of INR 1 846 billion (USD 26.8 billion). The amounts allocated represent a significant burden on states’ budgets, as they are between three to seven times their respective annual agricultural budgets. However, available estimates point to selected states having actually allocated by December 2018 approximately 40% of the overall announced amounts. The implementation of these programmes can vary across states, but waivers are usually conditional in most states. First, they are limited in terms of farms covered. For instance, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh granted waivers only for small-scale farmers, with landholdings of less than 5 acres (2 hectares). The waivers largely concern short-term credit, on which the banking sector has focused disproportionately. Small-scale farmers are particularly dependent on short-term credit, which enables them to procure seasonal inputs. Second, the waivers cover only specific periods of the production season. In this sense, state governments have been setting their own cut-off dates that define benefitting farmers according to the start date of the loan taken (Indian Express, 2018[14]; Times of India, 2018[15]; Times of India, 2018[16]; Live Mint, 2018[17]; Business Today, 2018[18]; ICRIER, 2019[19]).

Several inefficiencies exist with respect to the coverage and implementation of loan waivers. The documentation required to prove eligibility for the loan waiver has been proving burdensome for many small-scale farmers. In addition, non-institutional sources still account for as much as 36% of agricultural credit and thus de facto remain outside the scope of such schemes (OECD/ICRIER, 2018[2]; Hindustan Times, 2018[20]).

Based on the experience gained in 2016-17 in the implementation of the crop insurance scheme (Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, Prime Minister Crop Insurance Scheme) and with a view to ensure increased transparency, accountability and timely payment of claims to the farmers, the central government revised the PMFBY’s Operational Guidelines from 1 October 2018. In this sense, the insurance companies that fail to clear crop insurance claims within two months and state governments that delay their contribution will both have to pay farmers a 12% interest. The Guidelines also provide insured farmers with an additional day to file individual claims, directly through the programme’s portal (GOI, 2018[21]).

Other payments to producers

To improve the liquidity position of sugar mills and enable them to clear cane price arrears they have towards farmers, the central government approved in May 2018 a payment of INR 5.5 per 100 kg (USD 0.8 per tonne) of sugar cane to farmers. The payment is to be provided directly to farmers and concerns output sold to mills during the marketing year 2017-18 (GAIN-IN8115, 2018[8]; GOI, 2018[22]; GOI, 2018[23]).

The Government of India presented the 2019-20 Interim Budget on 1 February 2019. The most important aspect concerning agriculture within the Interim Budget is the implementation of the Income Support Scheme (PM-KISAN). This programme will provide a direct income transfer to small-scale farmers (with landholdings of up to 2 hectares) amounting to INR 6 000 (USD 87) annually independent of the farm size, to be paid in three equal instalments. The unconditional payment does not require farmers to produce and targets farmers’ broad needs, which can include everything from the purchase of inputs to any other non-farming related needs. The first instalment covers 1 December 2018 to 31 March 2019. Land records as on 1 February 2019 in the concerned states and UTs are used for identification of beneficiaries. However, in practice, given the remaining inefficiencies in the land recordkeeping system, the vast majority of land records reflect outdated information (GOI, 2019[24]). The Telangana state government had first introduced such type of income support of INR 4 000 per acre (USD 142.7 per ha) in May 2018, to be provided twice per year (the Rythu Bandhu Scheme) (Gulati and Saini, 2019[25]).

Domestic marketing regulations

The Agriculture Export Policy approved in December 2018 (see trade policy developments section) notes that it aims at using the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) field offices, Export Promotion Councils, Commodity Boards and Industry Associations to act as ‘advocacy forum’ for domestic marketing regulations reform by all the states. Other areas of action include working with state governments to remove perishables from their respective APMC Acts as well as to rationalise and streamline mandi (government-regulated wholesale markets) taxes on export-oriented agricultural products (GOI, 2018[26]).

Changes to land regulations

Restrictive land leasing laws have largely contributed to making tenancy be informal, insecure and inefficient. There is also significant variation in the adoption and implementation of land and tenancy reforms across states and over time. The Union Budget 2018-19 put forward the Model Land Cultivators License Act, proposing to provide tenant cultivators with a licence, without compromising on the legal rights of the landholder. The licence would enable these farmers to avail the benefits of farm credit, crop insurance, and compensation in the event of a natural calamity (MOF, 2018[27]).

Policies relating to agri-environmental areas

Through the scheme for the Promotion of Agricultural Mechanization for In-situ Management of Crop Residue – introduced in March 2018 – payments support farmers in addressing air pollution caused by in-situ crop residue burning in the states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and NCT of Delhi. The scheme foresees the establishment of custom hiring centres that provide subsidised in-situ crop residue machinery and equipment to individual farmers. It also provides support by creating awareness through demonstration camps and capacity building activities for effective management and utilisation of crop residue. Financial assistance of 50% is provided to individual farmers for procurement of equipment and machinery. State governments, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), and Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVKs, agricultural science centres) are also involved in supporting capacity building programs, trainings, communication and information activities for raising awareness on in-situ crop residue management and achieving zero straw burning (GOI, 2018[28]).

A dedicated Micro Irrigation Fund set up under the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) has been approved with an initial allocation of INR 20 billion (USD 289.8 million) for encouraging public and private investments in micro irrigation.4 The main objective of the Fund is to support the states in mobilising the resources for expanding coverage of micro irrigation (MAFW, 2018[29]).

Support to processors

The central government has been introducing several measures that would encourage sugar mills to increase sugar processing for ethanol production. In June 2018, it approved soft loans (i.e. loans with a below-market rate of interest) to sugar mills of INR 44.4 billion (USD 640 million) through banks for setting up new distilleries or for expanding existing capacity. In September 2018, the CCEA then approved an increase to the ex-mill prices for ethanol by between 7% and 11% according to the feedstock used (whether derived from either B heavy molasses and partial sugarcane juice, from 100% sugarcane juice, or from C-molasses) (GAIN-IN8115, 2018[8]).

Food subsidy

The Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution released on 31 May 2018 the “Handbook for Implementation of Cash Transfer of Food Subsidy”, developed jointly with the Department of Food and Public Distribution (DoFPD) and the World Food Programme (WFP). The Handbook aims to serve as a guide to all states and UTs that are implementing or planning to implement cash transfers for food subsidy. It details out the prerequisites, processes, and roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders involved in the cash transfer process. Pilots for food subsidy through direct cash transfers are currently being implemented in the UTs of Chandigarh, Puducherry and urban areas of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. The Handbook also highlights recent achievements in reducing leakages in the current food distribution system through automation of operations and biometric authentication of beneficiaries (GOI, 2018[30]).

Trade policy developments in 2018-19

Changes to tariff measures and other taxes on imports

The Government of India 2018-19 Union Budget replaced the 2% Education Cess and the 1% Secondary and Higher Education Cess5 with a Social Welfare Surcharge (SWS) of 10% of the tariff on imported goods, including several food and processed food products. The SWS collected is to fund various social welfare schemes in education, health and social security. Specified goods, which were exempt from the levy of the Education Cess and the Secondary and Higher Education Cess, are also exempted from the SWS. These include poultry cuts and offal (chilled and frozen), selected dairy products, selected fruits, dried peas, selected coffee products, and rice (MOF, 2018[31]; MOF, 2018[32]).

The multi-favoured nation (MFN) tariff for sugar was raised from 50% to 100% in February 2018 (GOI, 2018[22]; GOI, 2018[23]). On 23 May 2018, the MOF Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (CBIC) also notified an increase in MFN tariffs on other imported agricultural products, including shelled almonds, in-shell walnuts, wheat, protein concentrate and textured protein substances. The tariff for wheat was raised from 20% to 30% (GAIN-IN8067, 2018[33]).

On 1 March 2018, MOF CBIC raised the tariff for chickpeas from 40% to 60%. On 16 May 2018, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) under MOCI issued a notification that restricted all peas imports for the period of 1 April to 30 June 2018. A subsequent DGFT notification of 2 July 2018 extended this quantitative restriction until 31 December 2018 and in January 2019 it was further prolonged to 31 March 2019 (CBIC, 2018[34]; GAIN-IN8110, 2018[35]; GOI, 2018[36]). On 29 March 2019, MOCI extended the quantitative restriction for peas and other selected pulses until 31 March 2020. Imports of pigeon peas will be subject to a quota of 200 000 tonnes and other pulses to a quota of 150 000 tonnes (GAIN-IN9028, 2019[37]).

On 20 June 2018, MOF announced tariff increases on various products imported from the United States, in retaliation to the duty increases introduced by the United States on steel and aluminium. The retaliatory tariffs cover several agricultural products, such as kabuli chana chickpeas, Bengal gram chickpeas, lentils, almonds and walnuts in shell, or apples. The increased tariffs were initially announced to take effect from 4 August 2018 but have been postponed repeatedly and as of 29 March they were deferred until 2 May 2019 (Global Trade Alert, 2019[38]).

Under the terms of the India-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, on 31 December 2018, MOF notified a lower tariff effective 1 January 2019 for imports of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) and RBD (refined, bleached and deodorised) Palm olein from ASEAN countries to 40% and 50%, respectively (CBIC, 2018[39]; CBIC, 2018[40]).

Export measures

A MOCI notification of 2 February 2018 removed the minimum export price6 for onions (of USD 700 FOB per tonne), applied since November 2017, until further notice (MOCI, 2018[41]).

Several export measures are also part of the 2018 support package for sugar producers and mills. In this sense, the export tax on sugar exports was withdrawn and Minimum Indicative Export Quotas (MIEQ) of 5 million tonnes were allocated mill-wise covering the 2017-18 marketing season (representing about 15% of 2018 production). A Duty Free Import Authorization (DFIA)7 scheme for sugar mills was introduced to incentivise export of surplus sugar. Support for sugar exports also includes a transport cost subsidy by between INR 1 000 and INR 3 000 (USD 14.5 and USD 43.6) per tonne, depending on the distance to the port (GOI, 2018[22]; GOI, 2018[23]).

The DGFT introduced a 7% export subsidy for chickpeas (between April – June 2018) and a 5% export subsidy for non-basmati rice (between November 2018 – March 2019) – based on the FOB value of the products – under the 2015-20 Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) (GAIN-IN8110, 2018[35]; Economic Times, 2018[42]).

In July 2018, the western states of Gujarat and Maharashtra, India’s leading milk producers, provided a subsidy of INR 50 000 (USD 728) per tonne for exports of skim milled powder (SMP), while the central government approved a further subsidy of 10% of the export price (Reuters, 2018[43]).

In December 2018, the GOI approved the Agriculture Export Policy framework. Key objectives of the policy document include doubling agricultural exports by 2022 and boosting the value added of agricultural exports. Underlining that there is “an increasing need for the GOI to establish a stable and predictable Agriculture Export Policy, which aims at reinvigorating the entire value chain”, the policy document proposes three main areas for action that could support the above objectives. First, ensuring that processed agricultural products and organic products will not be subject to export restrictions. Second, initiating consultations among stakeholders and Ministries in order to identify the “essential” food security commodities on which export restrictions could still be applied under specific market conditions. Third, reducing import barriers applied to agricultural products for processing and re-exporting. The central government also approved the proposal for establishing a monitoring mechanism to oversee the implementation of this policy framework, with MOCI as the coordinating department and with representation from various line Ministries/Departments and Agencies as well from state-level governments (GOI, 2018[26]; Hindu Business Line, 2018[44]).

References

[5] AMIS (2018), AMIS Market Monitor No. 56, March 2018, http://www.amis-outlook.org/fileadmin/user_upload/amis/docs/Market_monitor/AMIS_Market_Monitor_Issue_56.pdf.

[18] Business Today (2018), “Only 40% Farm Loan Waivers in 4 States So Far; Here are Major Reasons for Delay”, 24 December, https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/only-40-pct-farm-loan-waivers-in-4-states-major-reasons-for-delay/story/303821.html (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[34] CBIC (2018), “Notification No. 25 /2018 – Customs”, Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs, Ministry of Finance, 6 February.

[39] CBIC (2018), “Notification No.82/2018 - Customs”, Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs, Ministry of Finance, 31 December.

[40] CBIC (2018), “Notification No.84/2018 - Customs”, Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs, Ministry of Finance, 31 December.

[3] Climate Action Tracker (2018), “Countries: India”, http://climateactiontracker.org/countries/india.html (accessed on 15 January 2019).

[11] Economic Times (2018), “Government to Procure 44 Lakh Tonne of Oilseeds and Pulses Under the PM- AAASHA Scheme”, 27 October, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/government-to-procure-44-lakh-tonne-of-oilseeds-and-pulses-under-the-pm-aaasha-scheme/articleshow/66390149.cms (accessed on 1 March 2019).

[42] Economic Times (2018), “Non-basmati exporters to get 5% benefit under merchandise exports scheme”, 26 November, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/india-to-give-5-percent-subsidy-for-non-basmati-rice-exports-for-4-months-government/articleshow/66762378.cms (accessed on 15 March 2019).

[33] GAIN-IN8067 (2018), “Government of India Increases Tariffs on Certain Agricultural Imports”, Global Agricultural Information Network, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 6 June, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Government%20of%20India%20Increases%20Tariff%20on%20Certain%20Agricultural%20Imports_New%20Delhi_India_6-7-2018.pdf.

[6] GAIN-IN8086 (2018), “India: Grain and Feed Update”, Global Agricultural Information Network, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 17 July, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Grain%20and%20Feed%20Update_New%20Delhi_India_7-17-2018.pdf.

[35] GAIN-IN8110 (2018), “Pulses Market and Policy Changes - A Review of the Last 5 Years”, Global Agricultural Information Network, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 28 September, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Pulses%20Market%20and%20Policy%20Changes%20-%20A%20Review%20of%20the%20Last%205%20Years_New%20Delhi_India_9-28-2018.pdf.

[8] GAIN-IN8115 (2018), “India: Sugar Semi-annual”, Global Agricultural Information Network, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 18 October, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Sugar%20Semi-annual_New%20Delhi_India_10-18-2018.pdf.

[37] GAIN-IN9028 (2019), “India Notifies Continued QRs on Pulses in IFY 2019”.

[38] Global Trade Alert (2019), “India: Imposition of Duties on Imports of Goods from the United States”, https://www.globaltradealert.org/intervention/61850/import-tariff/india-immediate-notification-of-proposed-suspension-of-wto-concessions-and-imposition-of-duties-on-imports-of-goods-from-the-united-states.

[24] GOI (2019), “Government committed to farmers’ welfare”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=188894.

[13] GOI (2018), “DBT in Fertilizer Subsidy Schemes”, Government of India, Department of Fertilizers, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, http://fert.nic.in/sites/default/files/documents/website%20dbt.pdf.

[26] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves agriculture export policy”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186182 (accessed on 10 March 2019).

[23] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves comprehensive policy to deal with excess sugar production in the country”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://www.pib.nic.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1547295 (accessed on 10 March 2019).

[7] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves enhanced MSP for Rabi Crops of 2018-19 Season”, 3 October, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://www.pib.nic.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1548396 (accessed on 8 January 2019).

[4] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves hike in MSP for Kharif crops for 2018-19 Season”, 4 July, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://www.pib.nic.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1537544 (accessed on 8 January 2019).

[22] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves interventions to deal with the current crisis in the sugar sector”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA), http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=179797 (accessed on 10 March 2019).

[9] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves new umbrella scheme Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA)”, 12 September, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=183409 (accessed on 8 January 2018).

[28] GOI (2018), “Cabinet approves promotion of agricultural mechanisation for in-situ management of crop residue”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=177136 (accessed on 28 February 2019).

[21] GOI (2018), “Government modifies operational guidelines for PMFBY”, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=183545 (accessed on 10 March 2019).

[30] GOI (2018), “Government of India makes systematic progress towards cash transfers of food subsidy”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=179657 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

[36] GOI (2018), “Quantitative restrictions on import of pulses”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=187272 (accessed on 20 March 2019).

[25] Gulati, A. and S. Saini (2019), “An Answer to Rural Distress”, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/indian-farmers-suicides-agrarian-crisis-farmer-protest-5525912/ (accessed on 7 January 2019).

[44] Hindu Business Line (2018), “New Agri-export Policy Gets Cabinet Nod”, 16 December 2018, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/new-agri-export-policy-gets-cabinet-nod/article25682474.ece (accessed on 10 March 2019).

[20] Hindustan Times (2018), “The Politics of Loan Waivers: Deep Despair of Punjab’s Excluded Farmers”, 6 April, https://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/the-politics-of-loan-waivers-deep-despair-of-punjab-s-excluded-farmers/story-og43IIdFAKrFaT9TK3NUVK.html (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[19] ICRIER (2019), Background report for the 2019 Monitoring and Evaluation of Agricultural Policies in India.

[14] Indian Express (2018), “Politics over Economics of Farm Loans: My Waiver vs Your Waiver”, 20 December, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/politics-over-economics-farm-loans-my-waiver-your-waiver-amit-shah-gehlot-rajasthan-bjp-congress-agrarian-distress-5501315/ (accessed on 10 January 2019).

[17] Live Mint (2018), “Farm Loan Waiver Doesn’t Do Much for Maharashtra Farmers”, 25 December, https://www.livemint.com/Politics/6d990NXpfqaOIboKA7FVvK/Farm-loan-waiver-doesnt-do-much-for-Maharashtra-farmers.html (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[12] Live Mint (2018), “Farmer Angst Stokes Record Pulses Procurement in 2017-18”, 28 June, https://www.livemint.com/Politics/FoJ7WHJxWfSxV4uZmu3KII/Farmer-angst-stokes-record-pulses-procurement-in-201718.html (accessed on 17 February 2019).

[29] MAFW (2018), “Rainfed Farming System - Programmes, Schemes & New Initiatives”, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, http://agricoop.gov.in/divisiontype/rainfed-farming-system/programmes-schemes-new-initiatives (accessed on 1 March 2019).

[41] MOCI (2018), “Export Policy of Onions – Removal of Minimum Export Price”, GOI Notification No. 48/2015-2020, Ministry of Commerce & Industry.

[31] MOF (2018), “Finance Bill, Reference Clause 108”, Ministry of Finance, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ub2018-19/fb/bill.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2019).

[32] MOF (2018), “Notification No.11/2018-Customs”, Ministry of Finance, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ub2018-19/cen/cus1118.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[27] MOF (2018), “Summary of Budget 2018-19”, Ministry of Finance, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=176062 (accessed on 28 February 2019).

[10] NITI Aayog (2018), “NITI Aayog to Work on Mechanism for Implementation of MSP for Different Agricultural Crops”, 9 March, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=177233 (accessed on 8 January 2019).

[1] OECD (2019), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

[2] OECD/ICRIER (2018), Agricultural Policies in India, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302334-en.

[43] Reuters (2018), “India’s Milk Powder Exports to Surge on Subsidies, Dampen Global Prices”, 27 July, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-milk-exports-exclusive/exclusive-indias-milk-powder-exports-to-surge-on-subsidies-dampen-global-prices-idUSKBN1KH0GQ (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[16] Times of India (2018), “INR 4 250 crore Agriculture Debt Waiver ‘Minuscule’, Say Farmers”, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/rs-4250-cr-agri-debt-waiver-miniscule-say-farmers/articleshow/63447757.cms (accessed on 15 February 2019).

[15] Times of India (2018), “Karnataka Budget: Loan Waiver of INR 25 000 for Farmers with Borrowing below INR 2 lakh”, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/karnataka-budget-loan-waiver-of-rs-25000-for-farmers-with-borrowings-below-rs-2-lakh/articleshow/64867596.cms (accessed on 15 February 2019).

Notes

← 1. These replaced the former five-year plans prepared by the erstwhile Planning Commission of India (the 12th Five Year Plan 2012-17 was the last of these plans).

← 2. A Ministerial Decision on Export Competition at the WTO Ministerial Conference held in Nairobi in 2015 has put an end to the subsidisation of agricultural exports, which for India would occur at the end of 2023 (https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/l980_e.htm).

← 3. The kharif cropping season is from July to October during the south-west monsoon (summer) and the rabi cropping season is from October to March (winter). The kharif crops include rice, maize, sorghum, pearl millet/bajra, arhar (pulses), soybean, groundnut, cotton. The rabi crops include wheat, barley, oats, chickpea/gram, linseed, mustard.

← 4. Micro irrigation is an irrigation method with lower pressure and flow than a traditional sprinkler system. It encompasses several ways of water application: drip, spray, subsurface, or bubbler irrigation.

← 5. These represented additional charges on imported products or basic income taxes to finance education programmes.

← 6. This represents the price below which exporters are not allowed to export a specific commodity. It is set taking into consideration concerns about the domestic prices and supply of that specific commodity.

← 7. A DFIA is issued to allow duty free import of inputs which are required for the production of the export-oriented product.