copy the linklink copied!Assessment and recommendations

The Rural Development Strategy Review (RDSR) of Ethiopia studies the rural-urban transformation process of the country, along with the evolution of rural development strategies, and identifies potential areas of reform. This overview summarises the main results and recommendations of the RDSR. It recognises the large and continuous efforts of the Government of Ethiopia (GoE) in promoting rural development and highlights the increasingly important roles of intermediary cities. Ethiopia’s socio-economic landscape is fast changing, governed by three main transformations: economic, demographic and spatial. These transformations will bring both challenges and opportunities. However, the current framework for rural development, the Agricultural Development-Led Industrialisation (ADLI) strategy, may not be capable of fully addressing these challenges and reap on the benefits of rising opportunities. Thus, this report calls for a shift in paradigm, and updating of the current strategy, in order to maintain Ethiopia’s successful economic path and promote an inclusive rural-urban transformation.

copy the linklink copied!Introduction

Ethiopia is facing key challenges that require the reconsideration of its current approach towards rural development. In the mid-1990s, Ethiopia embarked on a series of reforms that transformed the country from a stagnant into a dynamic economy. Since 2004, the country has benefitted from unprecedented economic growth that has further translated into poverty reduction and higher levels of welfare. Despite the latter, the gap between rural and urban areas is increasing. Ignoring the rising rural-urban disparities will put the development process of Ethiopia at risk.

Ethiopia’s successful growth process has been driven by a series of reforms and development plans that aimed to create a conducive environment for structural transformation. The Agricultural Development Led Industrialisation (ADLI) strategy has been the basis for these reforms. ADLI accounts for a number of different policies but its main objective is to increase agricultural productivity. This approach seemed adequate at the time, considering the socio-economic context and low base from which Ethiopia’s growth process started post its political transition in 1991. However, today, the country stands at a different stage of its development path and faces different challenges from those that motivated ADLI at the time.

These new challenges stem from three major transformations that are currently underway in Ethiopia, which will have significant effects on the well-being of rural populations.

The first transformation is demographic. Ethiopia is in an early stage of its demographic transition, i.e. the country’s population will continue to grow between now and 2050, which means that a large number of people will enter the labour market in the coming years. The increase will be particularly important for rural areas, as these have higher fertility rates.

The second transformation is economic. Although the agricultural sector’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) is decreasing, it still accounts for more than two-thirds of total employment. In addition, non-farm activities only account for a small share of rural employment. The premature state of the rural non-farm economy questions the sector’s reliability as a potential source of employment opportunities in the short or medium term. Overall, Ethiopia’s structural transformation is taking place at a slow pace.

The third transformation is spatial. Ethiopia will remain a predominantly rural country until 2050, i.e. more than 50% of the population is expected to reside in rural areas. However, it is urbanising fast. Although the country is currently characterised by a monocentric urban system, the urbanisation process taking place is mainly being propelled by intermediary cities. Intermediary cities have a strong potential to contribute to rural development but are confronted with several binding constraints. These constraints include limited knowledge about the socio-economic processes shaping agglomeration effects, lack of adequate polices or policies implemented in silos, as well as a consistent financing gap.

Effectively addressing the challenges resulting from these three transformations will depend on the capacity of institutions and policies to adapt to these changes. In practice, it will require a paradigm shift in Ethiopia’s approach to rural development.

copy the linklink copied!Ethiopia has benefitted from sustained economic growth, which has contributed to poverty reduction

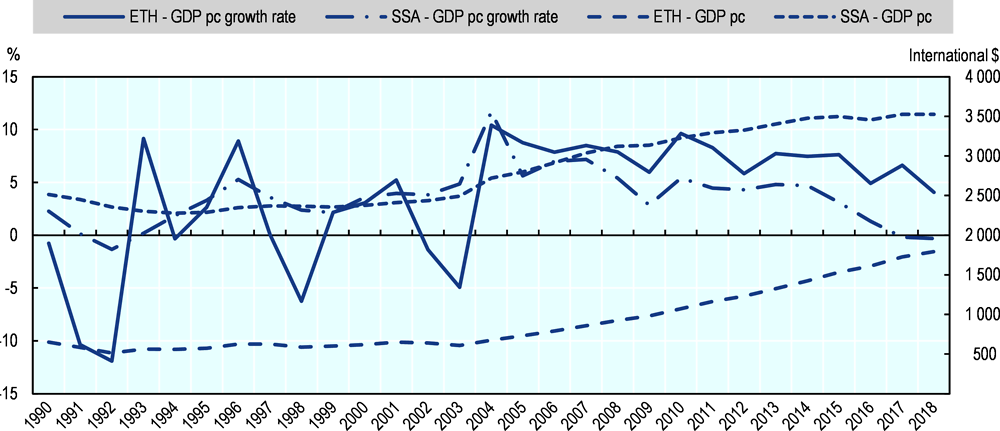

Ethiopia has achieved sustained economic growth since the mid-1990s. Ethiopia’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has experienced sustained growth, with an average annual growth rate of 7.4% between 2004 and 2018. Ethiopia’s economic growth outperformed that of the majority of other sub-Saharan African countries, which stood at an average of 5.2% during the same period (Figure 0.1).

Agriculture has consistently been the backbone of the Ethiopian economy, but its contribution to GDP is decreasing. In 1992, the share of GDP coming from agriculture peaked at 64%; since then it has decreased, reaching 31% in 2018. In parallel, there has been a slow shift in employment out of agricultural activities. Between 2005 and 2013, the share of employment corresponding to agricultural activities decreased from 80% to 73%. However, Ethiopia’s rural non-farm economy is still at an early stage in its development: more than 70% of Ethiopia’s rural households’ income comes from crop-production.

Grain crops have dominated Ethiopia’s agricultural production. In 2018, grain crops accounted for 79% of all crops produced, and almost 88% of all crop area in the country. Smallholders account for most of this production. In 2018, 16 million smallholders produced almost 95% of all grain crops in the country. Ethiopian smallholders are characterised by a very small plot size. In 2015, almost 64% of all holders produced crops in less than 1 ha, and almost 40% of holders produced crops in less than 0.5 ha.

Economic growth has translated into significant poverty reduction and overall human development since the mid-1990s. Ethiopia’s poverty head count, i.e. the share of the population living below the national poverty line, fell from 44% in 2000 to less than 30% in 2011, and to 24% by 2017. Human development has also increased since the mid-1990s. During the period 2000-10, Ethiopia’s Human Development Index (HDI) showed considerable improvement. The country’s HDI shifted from 0.35 in 2000 to 0.46 in 2013, with an average annual increase of 2.12%.

copy the linklink copied!Ethiopia is characterised by a growing population and a large share of young people

Ethiopia is going through the early stages of a demographic transition. Since the mid-1950s, Ethiopia’s total population has not stopped growing; in fact, it has increased from 18 million in 1950 to almost 99 million in 2015. This made Ethiopia the most populated country in East Africa in 2017, followed by Tanzania (53 million), Kenya (47 million) and Uganda (40 million).

Ethiopia is characterised by a very young population. Indeed, almost 42% of the total population is under 14 years of age, while the working-age population (those aged 15-64 years old) accounts for 55% (Figure 0.2). The nature of Ethiopia’s population structure puts a greater burden on its working-age population. Thus, the working-age group will continue to support the group, which is not yet in the labour market.

Ethiopia’s current population structure brings economic opportunities. Ethiopia’s demographic dividend started in 2002, and during its first year it potentially contributed 0.068% to economic growth; it will continue to contribute to economic growth until it peaks 22 years later (by 2024), reaching up to 0.92%. It will then slowly decline, and 65 years after it began, it will stop (by 2067). Changes in the population structure from then on will have a negative impact on economic growth.

Internal migration plays a key role in Ethiopia’s rural-urban transformation process. Although the scale of internal migration has not drastically changed since the late 1990s, its patterns have evolved. Notably, the importance of rural-to-urban migration has increased, while that of rural-to-rural migration has decreased. The most important driver of internal migration in Ethiopia is the search for employment. Although empirical evidence remains limited, rural-to-urban migrants seem to be better off when compared with non-migrants; consumption of goods other than food tends to more than double while diet further improves for migrants when compared with people who opted to not migrate.

copy the linklink copied!Ethiopia’s spatial dynamics are changing

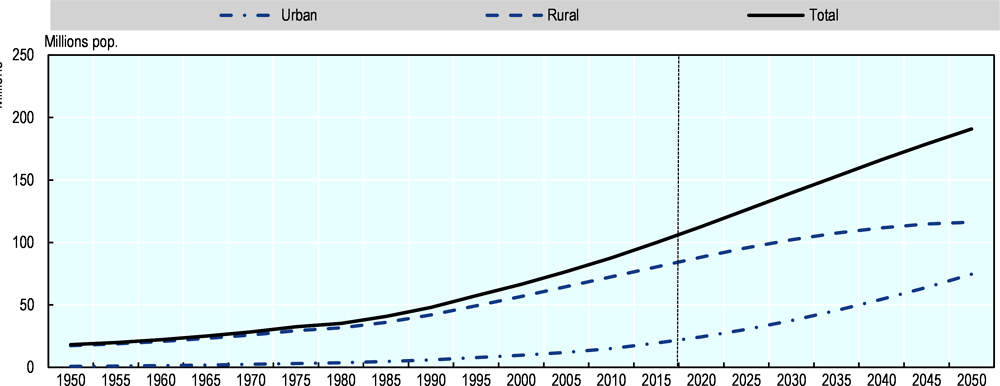

Ethiopia is, and will remain until at least 2050, a predominantly rural country. In 2015, the rural population was estimated to be approximately 80.5 million, or 81% of the total population. More importantly, although there are increasing investments to boost manufacturing, as well as ongoing efforts to improve rural electrification, irrigation and mechanisation (which will contribute to the rural-urban transformation), most of the population is expected to reside in rural areas until about 2050 (Figure 0.3).

Ethiopia is one of the least urbanised countries in the region. In 2015, urban areas hosted 20% of the Ethiopian population; this value is lower than the regional averages of sub-Saharan Africa and East Africa, which during the same year stood at 39% and 27%, respectively.

Ethiopia’s urban system strongly relies on its capital city, Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa is the largest city in Ethiopia and the only agglomeration with more than 1 million people. Other than Addis Ababa, there is a small group of cities characterised by a total population hovering at around 300 000 inhabitants; this includes agglomerations such as Mekele, Adama, Dire Dawa, Gondar and Hawassa. Although, today, Ethiopia is characterised by a monocentric urban system, several cities are starting to play more important roles. This could release pressure from Addis Ababa and allow other cities in the urban system to accommodate higher-value economic activities and inhabitants.

Ethiopia is urbanising rapidly. It took Europe 110 years to increase its urban population from 15% in 1800 to 40% in 1910, whereas Ethiopia will experience this change in half that time. By 2025, the urban population is expected to account for 24-29% of Ethiopia’s total population; this number will reach up to 30-40% by 2035.

Intermediary cities are driving Ethiopia’s urbanisation process. Cities with fewer than 50 000 inhabitants will continue to account for the largest share of Ethiopia’s urban population between 2020 and 2035, going from 51% in 2015 to 40% in 2035. Nevertheless, intermediary or medium-sized cities with the number of inhabitants ranging from 100 000 to 500 000 will experience the highest average annual growth rates, which are estimated to be 10.21% between 2015 and 2025 and 8.18% between 2025 and 2035 (Figure 0.4).

copy the linklink copied!There has been significant progress in terms of welfare in rural areas, but the rural-urban gap is increasing

Despite the success of poverty reduction in rural areas, since the mid-2000s, the gap between urban and rural areas has increased from 2005 to 2016. In 2000, the poverty head count in urban areas was close to 33%, i.e. almost 14 percentage points lower than in rural areas; by 2005, this difference was four percentage points, but by 2016, the difference had increased by almost 11 percentage points (Figure 0.5).

Although monetary poverty has decreased, multi-dimensional poverty remains high. In 2016, at the national level, Ethiopia’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) sat at 0.48, the highest value across those East African countries for which data is available. The total incidence of multidimensional poverty stood at 84%, i.e. 84% of the population in Ethiopia is considered multidimensionally poor. This number contrasts with the monetary poverty estimate, in which only 24% of the population is considered poor. Ethiopia also shows a large gap in multidimensional poverty between urban and rural areas. In 2016, rural areas’ MPI stood at 0.55, while in urban areas it stood at 0.16. Indeed, the incidence, i.e. the share of multidimensionally poor people in rural areas, reached almost 92% of the total rural population; in contrast, urban areas’ incidence was close to 16%. In other words, amongst the almost 74 million people living in rural areas in 2016, close to 68 million were multidimensionally poor.

Difference in terms of welfare between rural and urban areas risks to increase if Ethiopia’s ongoing economic, demographic, and spatial transformations are not properly addressed.

copy the linklink copied!Intermediary cities will play key roles for rural development and addressing the rural-urban gap

Addressing rural development in Ethiopia requires putting intermediary cities at the forefront of the development agenda. Intermediary cities help to promote a more inclusive urbanisation process and a balanced urban system. These agglomerations can enhance the living standards of urban dwellers by alleviating pressure from megacities in terms of housing, infrastructure, transportation and public service provision. They can provide the hard and soft infrastructure needed for attracting private and public investment. Well-managed intermediary cities can facilitate a rural-urban transformation and contribute to developing countries’ structural transformation process.

Ethiopia’s economic and spatial landscape is gradually changing, and intermediary cities are at the centre of this process. As discussed above, Addis Ababa plays a central role in Ethiopia’s urban system and it is characterised by a high primacy: it is 8 times bigger than the second largest city in the country. Nevertheless, despite Addis Ababa’s pre-eminence, a number of urban clusters of diverse sizes and functions are being formed; some of them are linked to the capital city following transportation and road infrastructure investment since the mid-1990s; others are anchored on regional capitals. Moreover, many intermediary cities are growing faster than Addis Ababa, further reducing the primacy of the capital (Figure 0.6).

The changes in Addis Ababa’s role further reflect the Ethiopian government’s efforts to establish a more balanced urban system. These efforts manifest in several ongoing policies, such as the development of industrial activities in regional capitals or intermediary cities. Following policy strategies, such as the promotion and establishment of export processing zones and industrial parks, cities like Adama, Adwa, Hawassa, Bishoftu, Sebeta and Mekele are expanding their manufacturing base. However, the population increase in these agglomerations largely outstrips employment creation.

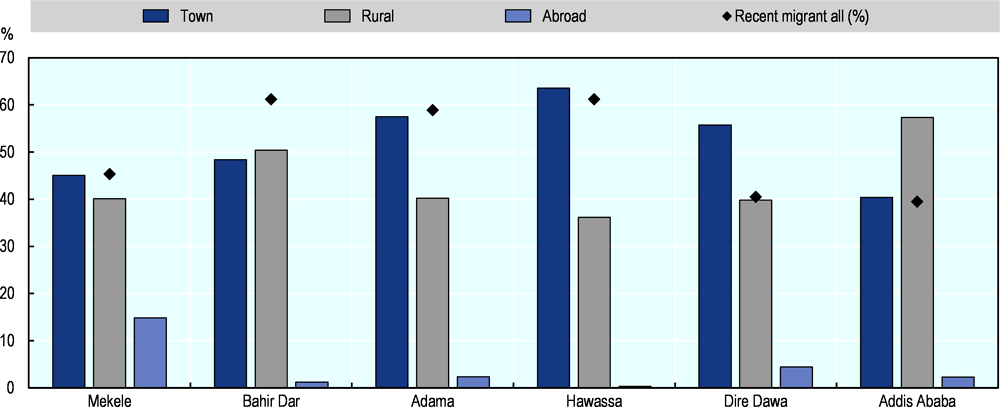

Rural-to-urban migration is a rising phenomenon in Ethiopia and across intermediary cities. As highlighted above, although Ethiopia’s internal migration has historically been dominated by rural-to-rural flows, large public investments in infrastructure, factories and public services, as well as employment opportunities, have fuelled rural-to-urban migration. However, rural migration is not always the main contributor of population growth across intermediary cities. Figure 0.7 shows the shares of recent migrants coming from rural areas, towns and abroad. In most of the selected intermediary cities, the largest share of recent migrants came from small towns and not from rural areas.

Increasing evidence suggests that intermediary cities can play an important role in enhancing rural well-being. They can help to reduce poverty by enabling better access to employment, health and education services, and urban infrastructure. In addition to providing access to basic services, intermediary cities enable flows of remittances between urban and rural areas. Their role in linking the two territories facilitates the circular or seasonal migration of rural households, and it also enables rural households to diversify their livelihoods and sources of income beyond the subsistence agricultural sector. However, the growth linkages between urban and rural areas depend on a number of factors, notably on the physical and market distances between them.

Ethiopian intermediary cities contribute to the development of rural areas in different ways:

-

They serve as market centres for agricultural goods and have growing potential to increase agricultural intensification and enhance diversification towards higher value-added agricultural goods. However, in most cases, market linkages need to be strengthened. Ethiopia’s predominantly subsistence agriculture-based economy limits the scope for the development of technologically advanced farming and commercialisation. Additionally, there are major constraints in providing an adequate supply of agricultural goods for industrial use or agro-processing in intermediary cities.

-

Intermediary cities can provide employment opportunities. The rate of job creation in some of Ethiopia’s intermediary cities is surpassing that of the capital city. Government-led policies and investment in the manufacturing sector are facilitating job creation, especially in cities such as Adwa and Mekele in the north; Adama, Sebeta and Bishoftu in the Oromia region; and Hawassa in SNNPR. However, despite having higher employment rates, intermediary cities are characterised by a larger informal sector compared with Addis Ababa.

-

Intermediary cities promote financial flows. Ethiopia’s intermediary cities play a crucial role in facilitating financial flows between urban and rural areas in many different ways. Intermediary cities host the headquarters of growing numbers of microfinance institutions (MFIs). MFIs tend to cater to the needs of low-income households (both rural and urban) which are unable to access larger formal institutions, and they provide small-sized loans. Remittances from intermediary cities to rural areas is another form of financial flow that follows from the opportunities developed across intermediary cities.

copy the linklink copied!Adama is an intermediary city that has strong potential for development

Adama benefits from its strategic location. The city, formerly known as Nazareth, is located along a major transportation corridor and is part of a developing connected urban cluster. Adama is located close to Addis Ababa, and has a strong connection to intermediary cities such as Mojo. Adama is one of Ethiopia’s fastest-growing cities in terms of population, urban built-up areas and economic function. According to CSA projections, the city’s population grew by 4.8% annually between 2010 and 2015; by 2016, the total population was expected to reach nearly 400 000.

Adama is linked with its surrounding rural hinterlands predominantly through production-consumption linkages and rural-to-urban migration. The city heavily relies on its surrounding rural areas for the supply of agricultural and livestock products, both for household consumption and for wholesale trade by local enterprises. Furthermore, Adama is a distribution centre for agricultural inputs, including fertilisers, herbicides, insecticides and other farming equipment.

However, there is still significant scope for strengthening the linkages between Adama and its surrounding rural areas. The current weak rural-urban linkages stem from a range of constraints, including economic and policy constraints, which limit Adama’s ability to build functional linkages with surrounding rural areas. This is largely because the economic planning for the municipality and the neighbouring zones are conducted separately, limiting the scope for integrated and harmonised policies. Furthermore, two additional fundamental issues constrain Adama’s ability to build strong rural-urban linkages: infrastructure constraints (including roads, public services and transportation), and the city’s inability to sufficiently generate productive jobs.

copy the linklink copied!Despite their potential, Ethiopia’s intermediary cities face critical challenges

Ethiopian intermediary cities are challenged by three fundamental gaps that affect their contribution not only to rural development but also to overall national economic growth:

-

Knowledge gap: Data on intermediary cities is either hardly available, or it is unreliable. Overall, there is a significant gap in the availability of reliable and representative empirical knowledge across Ethiopia’s urban areas. Current information on urbanisation trends, as well as on the functions and dynamics across all of Ethiopia’s urban areas, remains incomplete and is not representative at district level.

-

Policy gap: The policy gap concerns the lack of co-ordinated policies addressing the needs of intermediary cities, while accounting for their potential role in the urban system. Despite their fundamental roles and growth, intermediary cities remain overlooked in national urban policies as national urban policies tend to primarily focus on large agglomerations. In addition, rural and urban policies do not use a place-based approach and continue to rely heavily on the binary assumptions of rural and urban divide. As a result, policies targeting rural and urban areas treat the two territories in isolation, leaving intermediary cities to fall between the cracks of the urban and rural divide.

-

Financing gap: Despite their increasing population, intermediary cities have limited financial resources, and therefore limited capacity to invest in the infrastructure and public services needed to meet growing demand. Municipal revenue is the main source of funding for urban infrastructure investment; however, across Ethiopia, municipal revenue only makes up 3% of total national revenue, and there is a substantial gap between municipal expenditure and revenue. Intermediary cities that have a low tax base from which to extract revenue, and those that attract a low level of investment, face even larger constraints in adequately financing their infrastructure investment needs.

copy the linklink copied!The evolution of rural development policy in Ethiopia shows the need for a better integration of rural-urban linkages

Ethiopia’s rural policy has evolved along with political changes and in parallel to economic development. Prior to 1991, the monarchy (1941-74) and the Derg period (1974-91) both prioritised the industrial sector. National development strategies mixed export-oriented (mainly during the Imperial period) and import substitution industrial development strategies, and the agricultural sector tended to be used as a source of foreign currency. Since 1991, Ethiopia’s development strategies have dramatically changed from emphasising industry to emphasising agricultural sector-driven policies. In 1991, agricultural sector development and rural areas were placed at the heart of the national development agenda. This led to the establishment of the Agricultural Development-Led Industrialisation (ADLI) strategy as the main framework for national development. The ADLI functioned as the main pillar for all national development strategies, which prioritised small-scale agricultural sector development. Table 0.1 summarises the evolution of rural policy between 1950 until today.

The GoE implemented a series of restructuring reforms, which had been under way since the early 1990s. These reforms took the form of national development strategies such as: the Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (SDPRP), the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP), the Growth and Transformation Plan I (GTP I), and the Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTPII). Table 0.2 shows some of the main distinctions in policy approaches across the plans, and highlights some of the development strategies specifically targeting rural areas.

The progression across Ethiopia’s national development strategies reflect the changes in the socio-economic dynamics of the country since 1991. As of 1991, the Government of Ethiopia extensively invested in rural areas. The national focus on agricultural productivity has had dual objectives. First, the Government of Ethiopia is aiming to address the persistent issue of food security in the country. Second, it is aiming to boost agricultural output for industrial development, and enable Ethiopia to reach its Agenda 2025 goal of becoming a lower-middle-income country.

Ethiopia’s national development strategies have gradually expanded their remit to include the growing role of urbanisation and urban areas in national development. The Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP), as well as GTPI and GTPII recognise the key role of urban areas, especially in Ethiopia’s industrial development agenda. The PASDEP is particularly distinctive among the national development plans, as it is the only plan that explicitly promotes the urban agenda, has a comprehensive urban component, and integrates the National Urban Development Policy (NUDP) into the objectives of the development plan. The PASDEP and the NUDP stand out in their approach. Both plans take broader spatial approach and recognise the need for stronger rural-urban linkages, for inclusive rural development and promote the development of small towns. The two plans are well co-ordinated, and PASDEP embeds the main objectives of the NUDP as part of its urban development agenda. However, this approach is not carried on in the following development strategies.

copy the linklink copied!How to strengthen Ethiopia’s rural development strategy?

Ethiopia stands today at a different stage of its development path and faces different challenges from those that motivated ADLI in the mid-1990s. These challenges result from the country’s ongoing demographic, economic and spatial transformations. Addressing these challenges will require a shift in Ethiopia’s approach to rural development. This process entails updating ADLI in order to better capture Ethiopia’s new reality.

Experiences from emerging economies and OECD countries provide guidance on how to strengthen Ethiopia’s rural development strategy. The OECD’s New Rural Development Paradigm (NRDP) builds on these experiences and provides an analytical framework for assessing rural development strategies in emerging economies like Ethiopia. The NRDP stresses the need for strategies that are context-specific and maximise policy complementarities. Strategies need to be multi-sectoral, focusing on not just agriculture but also rural industry and services, and on not just rural areas but also rural-urban linkages. Strategies have to be multi-agent and multi-level, involving not just national but also local and regional governments as well as the private sector, international donors, nongovernmental organisations and rural communities.

This report proposes four main areas of reforms that could strengthen Ethiopia’s rural development strategy. These areas have been identified through the analytical framework provided by the NRDP, an extensive consultation process including key stakeholders in Ethiopia, two workshops held in Addis Ababa, as well as the analysis carried out by the OECD Secretariat. They are summarised as follows:

-

A new approach to agricultural development. Agriculture will continue to play a key role in Ethiopia’s development path. Increasing agricultural productivity has been, and will continue to be, key to reducing poverty. Moreover, increasing staple crops’ supply will also be necessary in order to support efforts to develop agro-processing industries, feed a growing population, as well as a key driver for off-farm job creation. However, as the country transforms, the approach to agriculture has to evolve from focusing mainly on improving agricultural supply to improving the productivity of the different elements composing agricultural value chains.

-

Mobilising resources and scaling up investment to improve the well-being of rural populations. The GoE has made major investments in infrastructure, especially in roads, electricity, and water and sanitation services. Nonetheless, striking differences between urban and rural areas prevail. Moreover, job creation will be necessary to reduce the rural-urban gap and promote the well-being of rural populations. Although off-farm activities in rural Ethiopia have (for the time being) a limited potential for job creation, the development of activities along downstream agricultural value chains offers interesting opportunities. However, this will further depend on creating a conducive environment for private sector participation.

-

Enhancing co-ordination between rural and urban policies. Ethiopia has excelled in the implementation of multi-sectoral interventions for rural development, but rural and urban policies are implemented in silos. Today, Ethiopia’s rural and urban policies tend to be fragmented. As a result, the socio-economic interactions between the two areas are not fully captured, and policies do not take into account or harness the changing dynamics of Ethiopia’s urban and rural landscape. Improving the capacity of local authorities will be necessary to address the needs of a growing population and effectively reduce policy fragmentation.

-

Complementing the existing policy framework with a territorial approach. The GoE has to facilitate the development of functional territories. However, implementing such approaches will require a learning process. Ethiopia could experiment with some pilot projects in certain zones and woredas. Based on the results from the pilot projects, the GoE could analyse the potential for extending this approach. This will further require improving the knowledge base regarding urban-rural processes, revise the existing definition of urban and rural areas, reinforce statistical systems, and carry out spatial planning at the regional level in order to provide sub-national governments with tools for evidence-based policy making.

Table 0.3 describes the suggested areas for reform, as well as a set of selected actions to achieve them. It is important to note that some of these actions are repeated across different outcomes. This repetition aims to highlight the need for a co-ordinated approach that builds on policy complementarities across different sectors. Moreover, these actions are not exhaustive, they aim to provide guidance on the way forward; they may also differ depending on the characteristics of each region or agro-environmental zone, and will eventually have to change in line with the evolution of Ethiopia’s economy and society.

References

[11] Alemu et al. (2002), “Agricultural Development Policies of Ethiopia since 1957”, South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 17/1-2, pp. 1-24, https://doi.org/10.1080/10113430209511142.

[9] CSA (2013), Labour Force Survey 2013, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/5870.

[3] CSA (2013), Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Wereda Level from 2014 – 2017, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, https://www.scribd.com/document/343869975/Population-Projection-At-Wereda-Level-from-2014-2017-pdf.

[8] CSA (2007), Population and Housing Census, 2007, Central Statistcal Agency, Addis Ababa, http://www.csa.gov.et/census-report/complete-report/census-2007.

[7] CSA (1994), Population and Housing Census, 1994, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2746.

[6] CSA (1984), Population and Housing Census 1984, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2745.

[18] MOA (2017), Rural Job Opportunity Creation Strategy, Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Addis Ababa.

[17] MoA (2015), Agricultural Growth Programme II, FDRE Ministry of Agriculture , Addis Ababa.

[15] MoFED (2010), Growth and Transformation Plan I, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Addis Ababa, http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/eth144893.pdf.

[14] MoFED (2006), Ethiopia: Building on progress - A plan for accelerated and sustained development to end poverty (PASDEP), Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Addis Ababa.

[13] MoFED (2003), Rural Development Policy and Stratgies, Ministry of Finance and Development , Addis Ababa, https://www.gafspfund.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/6.%20Ethiopia_Agriculture%20strategy.pdf.

[12] MoFED (2002), Ethiopia: Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (SDPRP), Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Addis Ababa.

[5] NPC (2017), Ethiopia’s Progress Towards Eradicating Poverty: An Interim Report on 2015/16 Poverty Analysis Study, National Planning Commission, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[16] NPC (2016), Growth and Transformation Plan II, National Planning Comission, Addis Ababa, https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/resilience_ethiopia/document/growth-and-transformation-plan-ii-gtp-ii-201516-201920.

[4] Schmidt, E. et al. (2018), Ethiopia’s Spatial and Structural Transformation Public Policy and Drivers of Change, International Food Policy Reserach (IFPRI), Washington DC, http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/132728/filename/132940.pdf.

[2] UNDESA (2018), World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, Online Edition., United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/.

[10] Welteji, D. (2018), “A critical review of rural development policy of Ethiopia: Access, utilization and coverage”, Agriculture and Food Security, Vol. 7/1, pp. 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0208-y.

[1] World Bank (2019), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators (accessed on 22 December 2019).

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/a325a658-en

© OECD and PSI 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.