Executive summary

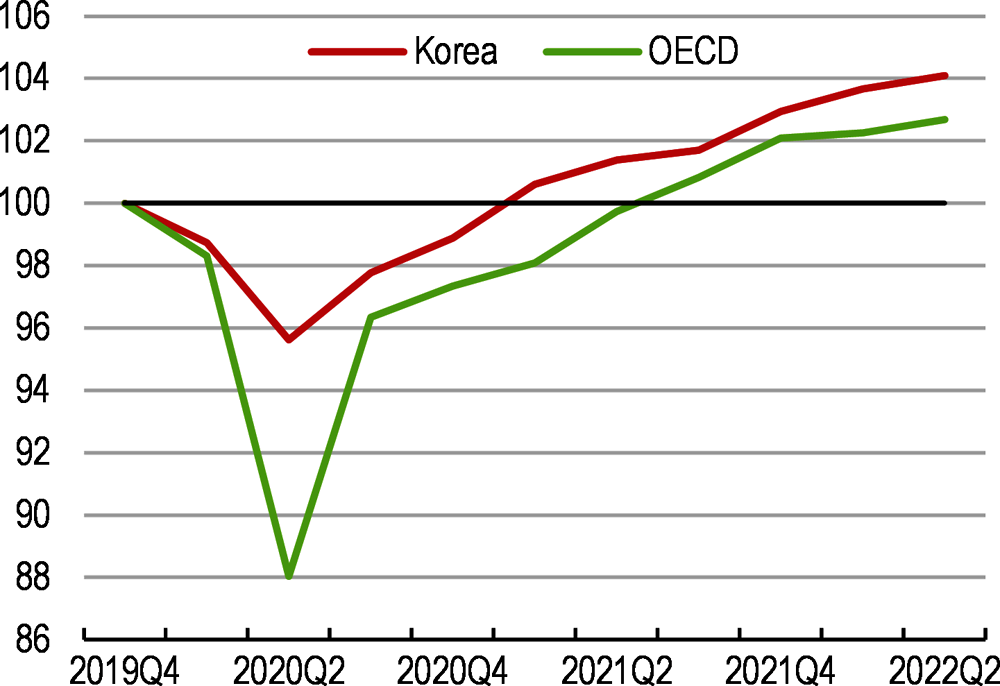

Korea’s skilful management of the COVID-19 pandemic protected its people and economy. GDP per capita surpassed the OECD average for the first time in 2020 on the back of one of the smallest GDP contractions among OECD countries, followed by a strong export-led rebound in 2021 and early 2022 (Figure 1).

The labour market is recovering. Employment has surpassed pre-crisis levels, led by health and public services jobs and job creation programmes. Manufacturing jobs have recovered to pre-crisis levels, while contact-intensive services lag behind.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is weighing on economic activity and exposes supply chain dependencies. Korea’s direct trade and financial links with Ukraine and Russia are limited, and stockpiles of oil and gas are considerable. However, a dependence on the two countries for raw materials to produce semiconductors highlights the need for resilience and diversification in the sourcing of key inputs for industry.

The recovery will continue, albeit at a slower pace. Real GDP is projected to grow by 2.8% in 2022, helped by additional fiscal stimulus from the Yoon government, and 2.2% in 2023. The Omicron wave and supply disruptions weighed on economic activity in early 2022, while the lifting of practically all restrictions set the stage for consumption in contact-intensive services to recover from late spring, although with a drag from inflation (Table 1).

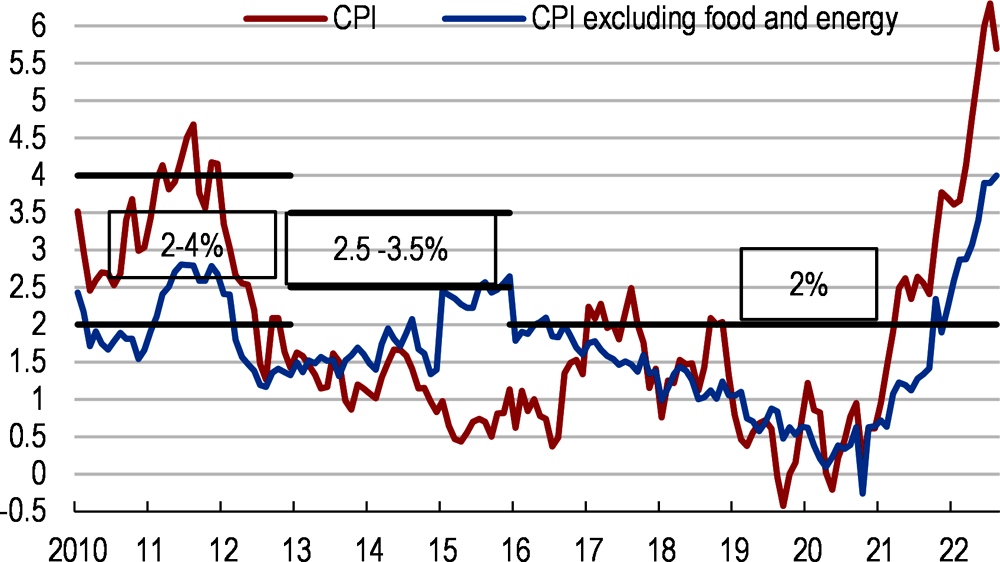

Monetary policy has been normalising on the back of high inflation pressures (Figure 2). Despite a tick-down, headline consumer price inflation remained almost triple the 2% inflation target in August 2022. Core inflation reached 4%. Wage increases remain modest. In a timely response, the Bank of Korea initiated normalisation in August 2021. So far, it has raised the key policy rate in seven steps from 0.5% to 2.5%, helping to keep inflation expectations anchored.

Public debt remains low in international comparison despite large pandemic-related fiscal deficits. As consumption finds its new normal, continued pandemic support to businesses would hinder necessary structural change. Future ageing-related expenditure increases also call for a rebalancing of support going forward.

Korea is among the OECD’s largest greenhouse gas emitters. It has committed to reducing emissions by 40% from the 2018 level by 2030, and to net zero by 2050. High emission intensity leaves room for emission reductions with considerable co-benefits from cleaner air. A renewed emphasis on nuclear will help, but investments need to be stepped up for renewables, transmission infrastructure and energy efficiency.

Korea’s emission trading scheme (K-ETS), the first in East Asia, covers about three-quarters of domestic emissions, but is not yet aligned with the new and more ambitious emissions reduction targets. Improving the institutional framework for electricity supply would allow the marginal carbon cost to pass through, improving the effectiveness of the K-ETS for electricity generation, a major and systemically important emitting sector.

A large majority of Koreans support efficient climate policies, provided that an explicit price on carbon is combined with funding for low-carbon technologies and infrastructure (Figure 3).

Sizeable productivity gaps between large and small firms raise concerns about insufficient competition. Regulations are stringent, notably in services. Large companies are highly productive and have considerable economic power. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with chronically low productivity receive numerous forms of support and special treatment allowing them to stay afloat. Compliance with worker rights to social insurance and minimum wages has room for improvement.

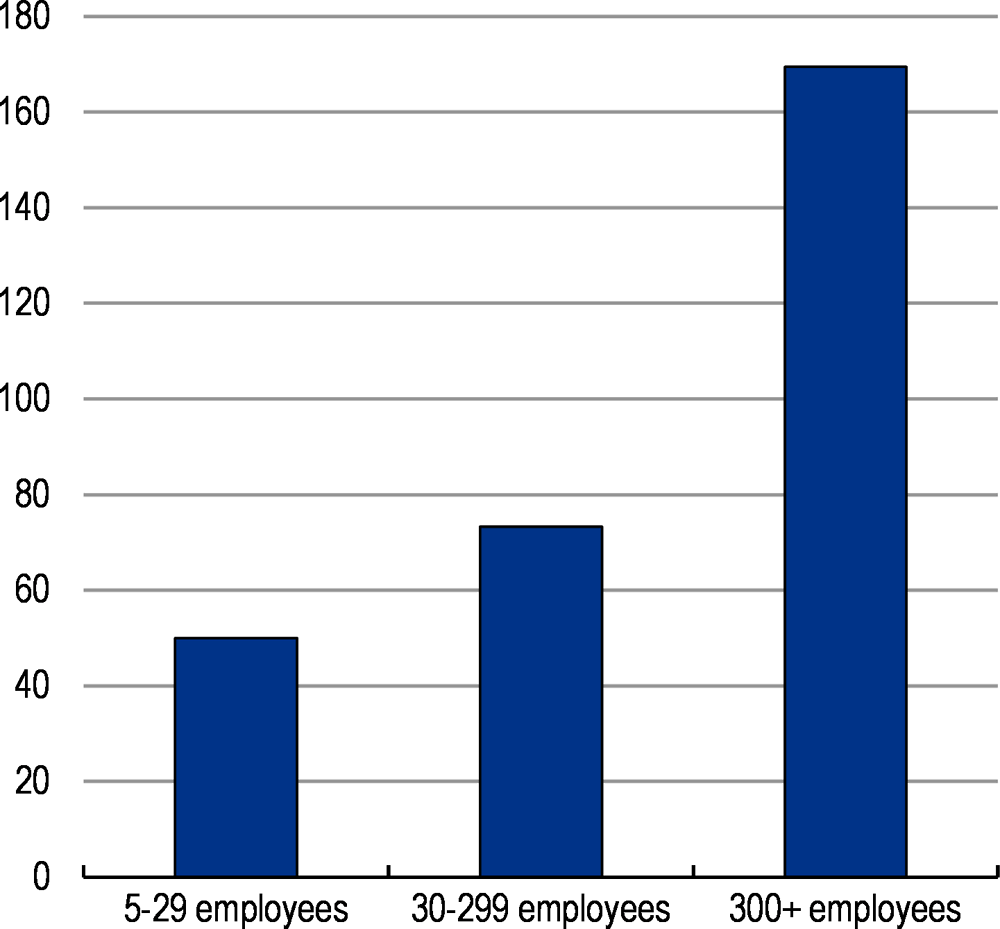

The productivity gaps lead to important income inequalities, which are compounded by labour market dualism. The incidence of non-regular workers is high in small companies relative to larger ones. Regular workers in large companies receive high wages (Figure 4), social insurance coverage and strong employment protection, while non-regular workers receive lower wages, are less likely to receive social insurance payments when they need it, and more likely to work in precarious jobs.

Women tend to end up on the wrong side of labour market dualism after childbirth, with a vastly negative impact on future earnings and social security. This stark choice between career and family largely stems from social norms and unforgiving work practices, but employer co-payments of maternal leave also play a role. The situation holds back female employment and leads young women to postpone family formation and have fewer children over their lifetime.

Faced with productivity gaps, labour market dualism and weaknesses in the education system, young people compete fiercely to enter good universties and land secure and attractive careers in large firms and the public sector.

This Korean “golden ticket syndrome” leads to low youth employment (Figure 5) and family formation, reduces life satisfaction, and potentially has a long-term scarring effect.

Competition to enter top universities is intense, leading to high pressure on students and large outlays on private tutoring. To gain admission, many students apply to departments that do not correspond to their interests and capabilities, resulting in sub-optimal use of talent. Universities face weak competition, in part due to admission quotas that are not flexible enough to respond to rapidly changing labour market demands.

The decline in vocational secondary education has contributed to mismatch between youth’s skills and labour market demand. The share of students attending vocational high schools fell from 40% in 1995 to 18% in 2021, reflecting in part a rise in vocational tertiary education. Moreover, their role has changed as the share of vocational graduates entering tertiary education has risen from 19% to 44%.

Weaknesses in the social safety net contribute to persistently high income inequality and poverty, notably among the elderly (Figure 6).

Only around half of the labour force has access to unemployment benefits. Furthermore, Korea’s tax-benefit system may discourage taking up or returning to low-paid work from social assistance or unemployment benefits.

Korea’s pension system as a whole fails to secure adequate pension income for many seniors. The Basic Pension is poorly targeted. Beneficiaries of the National Pension Service generally receive a low level of benefits, partly reflecting short contributory periods. Both workers and employers prefer severance payments over pension annuities, and participation in the supplementary personal pension scheme is low.

Despite mandatory insurance, health and long-term care is unaffordable for many elderly. Too few poor elderly are eligible for healthcare benefits under the Basic Livelihood Support. Many recipients of long-term care are unnecessarily hospitalised, reflecting weak primary care, lack of coordination between long-term care and health care, and underdeveloped home and community-based long-term care.