2. The broader social outcomes of education: Educating for thriving individuals and societies

High-quality education that translates into better and more relevant skills pays off for individuals, communities and societies in significant and diverse ways. It leads to higher earnings, increased productivity, innovation and sustained economic growth. Beyond these economic outcomes, high-quality education also generates a wide range of social returns. Better-educated individuals live longer and healthier lives. They become more engaged citizens and are more likely to take action for collective well-being. Sustained high-quality education supports communities in proactively addressing emerging challenges, such as climate change but also making the most of new opportunities, such as the digital transformation. This chapter provides an overview of the broader social outcomes of education. Such returns span a continuum, from private benefits (e.g. better health, better opportunities for one’s children) to societal ones, as private benefits translate into positive externalities and collective benefits. The social outcomes of education can thus be considered as an outcome in themselves or as a crucial channel towards better economic outcomes.

High-quality education pays off for individuals, communities and societies in significant and diverse ways

High-quality education leads to higher earnings, increased productivity, innovation and sustained economic growth. Beyond these economic outcomes, it also generates a wide range of social returns. Indeed, there is much evidence that high-quality education translates into enhanced public health and political participation, and helps individuals and societies adapt to change and respond creatively to disruptions. Better-educated individuals live longer and healthier lives. They become more engaged citizens and are more likely to take action for collective well-being. Sustained high-quality education supports communities in proactively addressing emerging challenges, such as climate change but also making the most of new opportunities, such as the digital transformation. When emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic arise, high-quality education is also key for building individual and societal resilience, and fostering a sustainable recovery.

High-quality education develops the skills, attitudes and knowledge that are crucial for individuals to thrive in an interconnected world, and contribute to societies’ transformations and collective well-being. In rapidly evolving economies and societies, a well-rounded set of skills, including cognitive, socio-emotional and digital skills, makes the difference between being ahead of the wave and falling behind. A good level of literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments is the key that enables individuals to unlock all the benefits of Internet use and use the Internet in diversified and complex ways rather than just for information and communication (OECD, 2019[1]). Beyond foundation skills, strong lifelong learning attitudes – namely a willingness to learn and a habit of learning – are vital for individuals to continue acquiring skills and knowledge at all stages of life, and hence, adapt more easily to changing life circumstances (OECD, 2021[2]). A good level of cognitive and socio-emotional skills, knowledge and attitudes also support individuals’ physical and mental health throughout life (Almlund et al., 2011[3]; Shuey and Kankaraš, 2018[4]). In addition, the framework of the OECD Learning Compass 2030 puts forward a range of transformative competencies that have the potential to help students shape a better future (OECD, 2020[5]). Such transformative competencies include how to create new value, reconcile tensions and dilemmas, and take responsibility, thereby blending critical thinking and creativity, empathy and respect. Evidence from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 shows that students who are better aware of global issues, more interested in learning about other cultures and better able to adapt their thinking and behaviour to novel situations are more likely to report that they take actions for collective well-being and sustainable development (OECD, 2021[6]).

Accordingly, many education systems are now integrating cross-cutting themes in their curricula, such as environmental education and sustainability issues (for 21 jurisdictions out of 37 examined), local and global citizenship and peace (19/37), core literacy and lifelong learning (19/37), and health education and well-being (19/37) (OECD, 2020[7])1. Education outcomes thus go beyond academic learning. Already in schools, education provides a setting to support and enhance students’ well-being, to enable students to socialise and benefit from productive interactions with their peers, become responsible and engage in collective actions. The pandemic has further emphasised the role of education systems beyond imparting knowledge and skills. Schools, teachers and education systems have been crucial in ensuring students remain in good health, access social services and participate in fruitful interactions during the pandemic. Beyond the protective role of school environments, at the individual level, skills and stronger attitudes towards learning such as self-efficacy or intrinsic motivation are likely to have shielded students from becoming disengaged or dropping out during school closures (OECD, 2021[2]). For adults, the level of education has made the difference between those who have remained engaged, at work, with public services or health providers and those who have been or felt left out or left behind. Lower-educated- people have felt more lonely and less included in societies than better-educated ones during the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2021[8]).

Educating with a whole-child and whole-of-society approach requires investments in education that acknowledge all the individual and societal benefits education provides (Box 2.1). Such benefits span a continuum, from private benefits (e.g. better health, better opportunities for one’s children) to societal ones, as private benefits translate into positive externalities and collective benefits. Better-educated individuals with healthier behaviours are more likely to be in good health and thereby help reduce the cost of healthcare and the spread of diseases. In turn, reductions in illness can translate into reduced social or health-related expenditure. Better-informed citizens, who participate more in the political life and are able to distinguish fact from opinion can support better-functioning public institutions and democracies. High-quality education can help individuals move up the social ladder, translating into higher social cohesion, reduced inequality and enhanced social mobility. Such social returns to education can thus be considered as an outcome in themselves or as a crucial channel towards better economic outcomes.

Countries increasingly take a whole-child approach in measuring the performance of their education systems, focusing on a range of social outcomes.

Apart from its participation in international assessments (e.g. PISA, the OECD Survey of Adult Skills – PIAAC), Chile relies on the Education Quality Measurement System (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación- Simce) to measure the performance of its education system. In the context of the Quality Assurance System, Simce assesses students’ learning outcomes in a range of curricular areas and in relationship with the school and social environment in which students evolve (MINEDUC, n.d.[9]; Agencia de la Calidad de la Educacion, n.d.[10]).

The standardised tests administered through Simce (ex. reading comprehension and writing, mathematics, natural sciences) are taken by students in Grade 2, 4, 6 and 8 of basic education, and Grades 10 and 11 of upper secondary education. Along with the assessments, Simce collects data on teachers, students and parents through questionnaires to analyse students’ outcomes in their wider learning context (Agencia de la Calidad de la Educacion, n.d.[10]). Simce measures key dimensions for a comprehensive child development through indicators for personal and social development that include: academic self-perception and self-assessment, school motivation, school climate, citizenship participation and training, and healthy life habits (Agencia de Calidad de la Educacion, 2019[11]).

Evidence from Simce test results combined with these personal and social development indicators have served as inputs for resource allocation to struggling education communities. Schools have thus been categorised in four performance levels (from high performance to insufficient), based on their students’ Simce test results and progress relative to previous measurements, personal and social development indicators, and a range of student characteristics (e.g. vulnerability) (MINEDUC, n.d.[12]). The resulting school categories have been used, first, to identify struggling schools and thus determine which schools will receive the evaluation and orientation visits carried out by the Quality Measurement System. Second, the categories have been used to provide support and allocate resources to schools in need.

In France, the Ministry of National Education and Youth has devoted particular efforts to developing analyses and applied research examining how education policies can shape social returns to education. Some of these projects have been carried out in co-operation with other public or government bodies (e.g. France Stratégie - an autonomous institution reporting to the prime minister and in charge of strategic reflection, the Ministry of Economy and Finance). The Ministry of National Education and Youth has put a strong focus on inclusion, understood in a broad sense beyond social inclusion. It has thus investigated the design of more inclusive schools for students with special education needs (e.g. through additional investments in human resources, teacher professional development) or how education policies can help bridge gender gaps.

Thus, in 2019, the Ministry of National Education and Youth and the Secretary of State for Equality between Women and Men and the Fight against Discrimination, together with other ministries with responsibilities in the area of education policy, signed a new agreement for gender equality in the education system covering the 2019-2024 period (Convention interministérielle pour l’égalité entre les filles et les garçons, 2019[13]). The agreement puts forward five intervention areas, including: i) steering the gender equality policy as closely as possible to the students, ii) training all education staff for gender equally, iii) transmitting a culture of equality and mutual respect to young people, iv) fighting sexist and sexual violence, and v) moving towards greater gender diversity in training provision through greater freedom for boys and girls in their orientation choices (Convention interministérielle pour l’égalité entre les filles et les garçons, 2019[13]). The ministry has thus devoted special attention to girls’ self-censorship throughout their education pathways as this also affects their subsequent inclusion in the economy and society. The ministry’s work programme has included work on guidance provision at key moments of students’ education pathways seeking to avoid self-censorship and/or discrimination in orienting girls (and boys) towards specific professions. In 2021, mandatory modules on gender equality to train the education community to deconstruct prejudice were also introduced as part of initial teacher education and teacher professional development (Ministère de l’Education Nationale et de la Jeunesse, 2022[14]).

This chapter therefore examines how education translates into a range of benefits for individuals, communities and societies:

First, the chapter analyses the role of sustained high-quality education for health and well-being, and in particular the mechanisms through which education impacts 1) health outcomes, health-related behaviours and life expectancy (as well as externalities on peers and children), and 2) mental health and psychological well-being.

Second, the chapter examines the role of education and skills for building more civic, cohesive and inclusive societies, putting the emphasis on how high-quality education 1) supports civic engagement and reduces antisocial behaviour to the benefit of communities, 2) helps build social capital, and particularly trust, 3) supports equity in subsequent lifetime outcomes and 4) forms more tolerant and open-minded individuals who can underpin more cohesive societies.

Third, the chapter delves into the critical role played by education systems in helping individuals, communities and societies 1) make the most of new opportunities, such as the digital transformation and 2) proactively addressing emerging challenges, such as climate change.

Better-educated individuals enjoy healthier and longer lives

Better-educated individuals tend to live healthier and longer lives (Galama, Lleras-Muney and Kippersluis, 2018[15]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). They are less likely to suffer from a range of health conditions (e.g. overweight, high blood pressure, heart disease), report better health-related behaviours (e.g., they eat healthier, smoke less, exercise more) and enjoy higher life expectancy.

Education translates into better health through better income and social protection, as well as healthier behaviours…

Education can translate into better health through a range of channels. Education helps individuals be better aware of risky health behaviours (e.g. excessive drinking) and better informed regarding available healthcare or medical services, thus taking better health-related decisions (Grossman, 1972[17]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). At the same time, education enhances other channels, such as income, that can in turn support a healthier life. Better-educated individuals are likely to have higher earnings, live in safer neighbourhoods and benefit from better health insurance through their jobs. Education can also improve health by reducing financial constraints to adopt a healthy and diverse diet, and stress due to low socio-economic conditions or difficulty in meeting basic financial ends (Marmot, 2017[18]; Lance, 2011[19]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]).

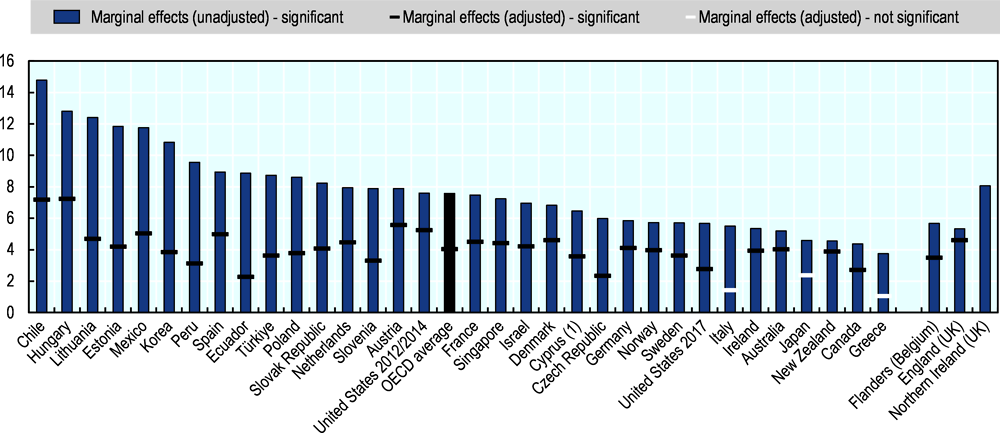

The positive relationship between education and health has been documented in a variety of countries. Adults with better numeracy skills display better self-reported health in countries with available data in the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Figure 2.1.). In a similar vein, individuals having attained a higher qualification via formal adult education, even at a later stage in life, are more likely to report good health outcomes relative to those who did not attain a higher qualification (Desjardins, 2020[20]). Higher education levels are also associated with higher life expectancy. Recent evidence on the relation between education attainment and longevity in OECD countries shows that average absolute gaps in life expectancy between high and low-educated individuals at age 25 were of 5.2 years for women and 8.2 years for men (Murtin and Lübker, 2022[21]).

Yet the strength of the association varies across countries, populations and types of health outcomes…

However, the strength of the association between education and health varies across countries and type of health outcomes. While education-related inequalities in smoking are significant across most European countries, Canada and the United States, they tend to be even larger in some Northern, Central and Eastern European countries (OECD, 2019[23]). In a similar vein, gaps in life expectancy by education level display large cross-country differences. In 2016, tertiary-educated adults at age 25 in Estonia on average had a 8 years longer life expectancy than their lower-educated peers (Eurostat, 2021[24]). In contrast, the education-related gap in life expectancy was of only 1.3 years in Italy, where adults also displayed higher average life expectancy in general. This being said, inequalities in life expectancy across countries tend to be smaller for individuals with higher education attainment compared to individuals with lower education or less (Marmot, 2017[18]).

Understanding the extent to which better education translates into healthier lives is crucial for addressing health inequalities (within and between countries), achieving better health outcomes at the societal level (e.g. reducing the spread of diseases) and more effectively using public resources. Research evidence on the causal impact of education on health remains, nevertheless, mixed (Galama, Lleras-Muney and Kippersluis, 2018[15]; Grossman, 2015[25]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). It highlights substantial heterogeneity in the estimated effects of education on health across time, space, populations and health outcomes studied. For instance, education has a stronger effect on men’s mortality than women’s mortality. By contrast, education-related inequalities in overweight are higher for women than for men (OECD, 2019[23]).

There are many factors that can drive the variation in education effects on health…

Education policies are thus likely to generate different effects on health in different contexts and environments (Lance, 2011[19]). Beyond methodological aspects, a range of factors can drive the observed heterogeneity in education effects on health (Galama, Lleras-Muney and Kippersluis, 2018[15]).

To start with, education translates into higher lifetime earnings that can be used for better health-related goods and services. At the same time, labour market returns to education vary for different groups of individuals, cohorts, in time and by academic streams or professional field (Bradley and Green, 2020[16]; Carneiro, Heckman and Vytlacil, 2011[26]).

Variations in the availability of general safety nets and universal health care access is also a likely factor behind the variation in the health outcomes of education, as illustrated by Figure 2.1.. Countries with universal health care access tend to display lower net effects of education relative to those where health insurance is tied to individual earnings – hence to educational attainment to some extent (Lleras-Muney, 2018[27]).

The availability of health-related information also matters as there is evidence suggesting that better-educated individuals are more responsive to it and thus more likely to adopt healthier attitudes and lifestyles where information is available (Galama, Lleras-Muney and Kippersluis, 2018[15]; OECD, 2019[23]). Illustrating this, while better-educated individuals displayed higher rates of smoking several decades ago, lower-educated individuals are now twice as likely to smoke (OECD, 2019[23]). The diffusion of information related to smoking risks is likely to have played a significant role in reducing the prevalence of smoking among the better-educated.

Differences in the quality of schooling, and hence, in the extent to which education systems equip individuals with a well-rounded level of skills matter for education’s effect on health outcomes (Lleras-Muney, 2018[27]). Studies that examine the impact of specific skills emphasise the role of high-quality education for health-related outcomes. Low literacy skills among young children aged 5 have, for instance, been associated with worse self-reported health outcomes and worsening health-limiting conditions during adulthood (Schoon et al., 2015[28]). Similarly, academic achievement, measured by performance on standardised tests in literacy and numeracy across childhood, is related to better self-reported health in adolescence and early adulthood (Shuey and Kankaraš, 2018[4]; Lê-Scherban et al., 2014[29]). In addition, socio-emotional skills equally help predict health-related behaviours in terms of diet, exercise and smoking (Almlund et al., 2011[3]; Heckman, Stixrud and Urzua, 2006[30]). In fact, socio-emotional skills can be more important than cognitive ones for a range of health-related outcomes (e.g. smoking, obesity and self-reported health) (Conti, Heckman and Urzua, 2010[31]; Lance, 2011[19]).

High-quality early childhood education and care can boost lifetime health outcomes, but the size of its effects can vary widely across beneficiaries. Early childhood education and care can bridge gaps between children of different backgrounds and ensure all children develop a well-rounded set of skills to thrive. For instance, a set of early childhood programmes targeted at disadvantaged children generated substantial benefits to participants in terms of reduced prevalence of heart disease, cancer, stroke and mortality across the lifecycle (García and Heckman, 2020[32]). While the programme resulted in large gains in terms of quality-adjusted life years for men, its benefits were relatively small for women. More generally, the type, beneficiaries and timing of early childhood interventions shape the size of their effects (Lleras-Muney, 2018[27]). Evidence from the Head Start early childhood education programme in the United States shows that the benefits of the programme vary largely across its recipients and depend on the quality of alternative care children would have received instead of Head Start (Kline and Walters, 2016[33]). The benefits are large for students who would otherwise be in home care, whereas they are negligible for those who would otherwise attend a different preschool.

Evidence suggests that the health benefits of education also play out in terms of positive externalities…

At the same time, education can also affect the health outcomes of peers or individuals’ own children, and education investment decisions need to account for such positive externalities. Research has documented, for instance, the existence of peer effects for teenagers’ excessive drinking or smoking behaviours (Lance, 2011[19]). In addition, parental education can have intergenerational effects on health. If better-educated mothers breastfeed more, provide healthier food for their children or ensure a better living environment for them, children’s health-related outcomes are likely to be enhanced. Better-educated parents can either spend more resources on health (e.g. live in better neighbourhoods or buy higher-quality medical products or services) or spend existing resources better (e.g. obtain better information about doctors or be more aware of health dangers and adapt their behaviour accordingly) (Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). Children’s health at a given time can therefore depend on children’s previous health condition, any parental investment made before and the environment in which children are born or evolve (e.g. parental relationship stability, school environment, whether they live in a better neighbourhood) (Conti and Heckman, 2014[34]). Parental education can thus affect children’s health at various life stages, from pregnancy and birth, until later in life when parental education shapes the environment in which children grow up and evolve.

Better-educated individuals also enjoy happier lives

High-quality education helps build the skills, knowledge and attitudes that support individuals’ mental health and psychological well-being throughout life...

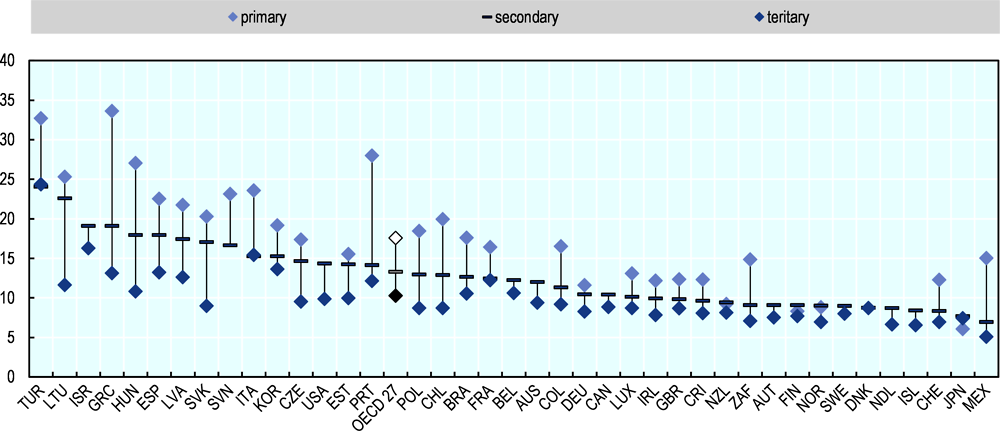

Around one in two people experience mental health problems at some point in their life and the COVID-19 pandemic further increased the pervasiveness of mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression (OECD, 2021[35]). Increased mental health or psychological problems are costly for individuals, employers and society (OECD, 2021[36]). But education systems can equip individuals with the skills needed to protect their psychological well-being and thrive in life. Indeed, higher levels of educational attainment are correlated with increased life satisfaction and less pervasive negative feelings and states (Figure 2.2. ). It is worth noting though that these education-related inequalities in subjective well-being are smaller in countries whose populations have higher average life satisfaction overall.

There are several channels for education to translate into mental health…

Similarly to physical health, mental health can benefit from high-quality education through a range of channels. Better-educated individuals have access to better resources and develop better health-related behaviours that in turn can favour their mental health. At the same time, they may enter more stressful occupations or face higher pressure to maintain high achievement (academically or professionally) (Dahmann and Schnitzlein, 2019[37]). Causal evidence of education’s role for mental health remains nevertheless mixed and less developed relative to research on education’s impact on physical health, notably due to data availability challenges.

Socio-emotional skills seem to play a key role in shaping mental health outcomes…

Social-emotional skills matter for mental health outcomes. Early socio-emotional skills play a key role in supporting individuals’ psychological well-being, from early ages and until adulthood (OECD, 2020[38]; OECD, 2021[39]). Socio-emotional skills related to emotional regulation – optimism, stress resistance and emotional control – are also associated with teenage students’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being (OECD, 2021[39]). Among the Big Five personality traits2 put forward by psychology research Agreeableness (including skills such as co-operation or trust), Conscientiousness (including skills such as the ability for self-control or persistence) and Emotional Regulation (including skills such as stress resistance) relate positively and strongly to both mental and physical health (Strickhouser, Zell and Krizan, 2017[40]). Social and emotional skills are thus strong predictors of life satisfaction across different ages in adulthood, even after accounting for individuals’ income and employment status as adults (Flèche, Lekfuangfu and Clark, 2021[41]).

Social-emotional skills are malleable and can be learned. The environments in which individuals evolve (e.g. family, peers, life events) and the learning activities in which they engage shape the development of social and emotional skills (OECD, 2015[42]; OECD, 2021[39]). A range of policy interventions, innovations in teaching practices and parental efforts can support their development (OECD, 2021[39]). While OECD countries’ curricula mostly emphasise cognitive skills, they give equal prominence to a range of social and emotional skills students need to develop to thrive in life (OECD, 2020[7]). Interventions focused on social and emotional learning have been found to be effective at increasing pro-social behaviour and reducing the need for behavioural programmes (OECD, 2021[39]). In addition, teachers play a key role in enhancing students’ social and emotional development. A range of teaching practices and approaches, including interactions with students, emphasis on critical thinking in specific subjects and classroom organisation are effective at enhancing students’ social and emotional development (OECD, 2021[39]).

… While the evidence regarding cognitive skills and well-being is more mixed during school years due to the effects of school climate and test anxiety

While better education tends to be associated with enhanced well-being in adulthood, higher academic achievement can display more ambiguous effects during school years given the risks of test anxiety and bullying.

Early cognitive skills, self-regulation, self-awareness, emotional health and social skills relate positively with adult mental health (Shuey and Kankaraš, 2018[4]; OECD, 2020[38]; Schoon et al., 2015[28]). Five-year-old children with better receptive language skills, better self-regulation and visual-motor skills display better mental health outcomes as adults (Schoon et al., 2015[28]).

During the school years, the relationship between student performance in cognitive assessments and their well-being is more ambiguous. 15-year-old students display lower average levels of life satisfaction than younger ones (OECD, 2021[39]) and better academic achievement does not automatically translate into higher life satisfaction. Students with very high and very low levels of life satisfaction display, for instance, lower reading scores in the PISA (2018) assessment (OECD, 2019[44]).

School climate and test anxiety are likely to shape these patterns. On the one hand, students’ life satisfaction is positively related to a good disciplinary climate in school, teacher support and feedback, students’ co-operation and sense of belonging in school. Students who were less exposed to bullying were also more likely to report higher life satisfaction (OECD, 2019[44]). On the other hand, more demanding learning environments for 15-year-olds, associated with higher parental and teacher expectations, and increased schoolwork pressure towards the end of compulsory education can limit students’ well-being. Students expressing a greater fear of failure displayed both higher academic achievement but also lower life satisfaction levels. Students’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being also relate negatively with test anxiety (OECD, 2021[39]).

Education policies and the focus of curricula on the whole child, including socio-emotional development, play a key role in addressing students’ psychological well-being and mental health conditions. Policy interventions should nevertheless ensure that while they seek to enhance all students’ well-being, they also provide specific, targeted support for learners experiencing mental health conditions (OECD, 2021[45]). Indeed, the characteristics and impact of mental health conditions require an integrated whole-of-government approach that brings together health, education, social protection and employment services (OECD, 2021[36]).

Education supports civic engagement and reduces antisocial behaviour to the benefit of communities and societies

Education also supports the formation of well-informed citizens…

Beyond its role in shaping a range of economic and broader social individual benefits, education supports the formation of engaged and well-informed citizens who can better contribute to their communities. Education systems can instil civic and democratic values in students, through the knowledge, attitudes and skills the latter acquire in schools. Analytical, information-processing and critical-thinking skills developed in schools can make for more enlightened and engaged citizens and, in turn, better-functioning democracies. Creativity helps individuals innovate, thrive from a personal perspective but also challenge existing norms and find new solutions when unexpected disruptions arise in their societies. Critical thinking is a crucial pillar of well-functioning democracies, even more in the digital age with its abundancy of information sources, multiplicity of facts and views, and rise of “fake news” (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[46]).

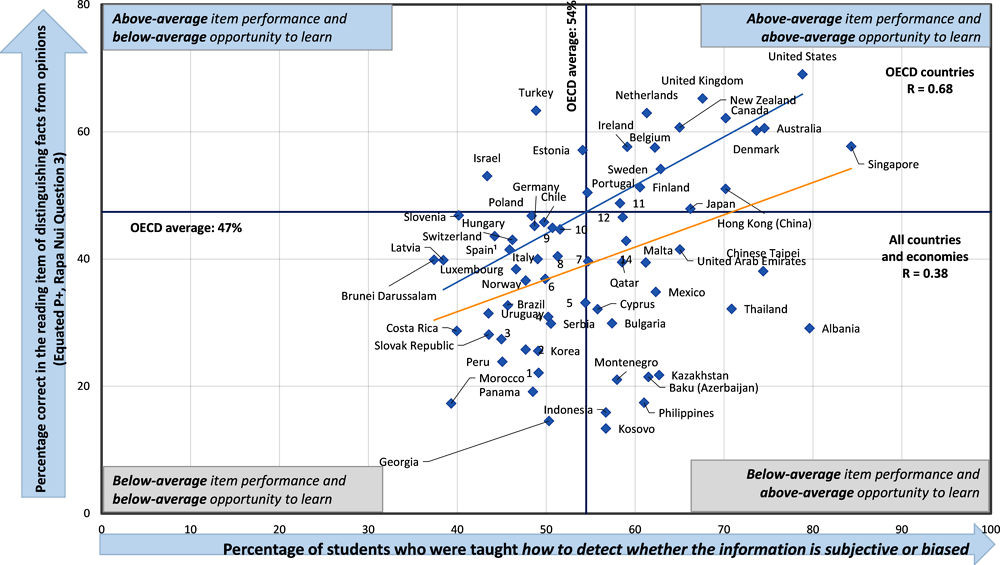

Evidence from PISA (2018) shows that education systems where more students are taught how to detect biased information in school also display higher proportions of students who are able to distinguish fact from opinion (Figure 2.3.). Yet, on average across OECD countries, only one in two 15-year-old students were trained at school on how to recognise biased information (OECD, 2021[47]), even though critical thinking and creativity can be taught, learned and assessed in primary and secondary education (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[46]). The relationship between students’ access to training on how to recognise biased information and their ability to distinguish fact from opinion varies across countries, suggesting there is leeway for education systems to learn from each other and enhance the effectiveness of such training (OECD, 2021[47]).

… and provides students with opportunities to exchange ideas and engage in collective activities to stimulate future civic engagement

In addition, education includes students in social networks, providing opportunities to interact, exchange diverse ideas and engage in collective activities. Schooling teaches students how to socialise in productive ways that matter for subsequent political and civic engagement (Glaeser, Ponzetto and Shleifer, 2007[48]). Collaboration skills can be taught and practiced in cognitive subjects (e.g. science, mathematics) but also in physical education class where students work together to reach common goals (OECD, 2017[49]). School and classroom activities and environments matter for students’ ability and attitudes towards collaboration. Students who engage in more communication-intensive activities (e.g. explaining ideas in science class, doing practical experiments and arguing about science questions) display more positive attitudes towards collaboration. Exposure to diversity in schools also relates positively to collaborative skills: students without an immigrant background tend to perform better in terms of collaborative skills when they are in schools with higher concentration of immigrant students (OECD, 2017[49]).

At macro level, there is strong correlation between education and the strength of democratic institutions, but equity of education outcomes seems to matter even more…

High-quality education matters for democracy and well-functioning institutions. Empirical analyses highlight the strong cross-country correlation between education and democracy, supporting the role of education as a crucial pillar for democracy (Lochner, 2011[50]; Apergis, 2018[51]). Macro-economic evidence on the effect of increases in a nation’s education on the strength of democratic institutions remains, however, mixed, reflecting a range of methodological challenges and differences in the estimation of a causal relationship. While most studies examine the role of average years of schooling, the distribution of education in a country appears to matter more than the average level of its population’s education for the implementation and sustainability of democracy (Castelló-Climent, 2008[52]). Indeed, greater equity in education outcomes is associated with stronger measures of political rights and civil liberties. In addition, evidence based on foreign students’ role for institutions in their home countries suggests that education systems’ efforts to teach democratic values tend to make a difference (Glaeser, Ponzetto and Shleifer, 2007[48]; Lochner, 2011[50]). Foreign-educated individuals tend to promote democracy at home when they acquire their foreign education in a democratic country (Spilimbergo, 2009[53]).

… While at micro level, education tends to translate into higher voter engagement, but less so in volunteering activities

At the individual level, investment in schooling tends to translate into higher voter engagement (e.g. voter registration, voting), political information (e.g. following campaigns and public affairs) and support for free speech (Lochner, 2011[50]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). Available research on the effect of schooling for civic engagement tends, however, to rely on data from the United States, with additional evidence stemming from Germany and the United Kingdom. Evidence from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills shows that adults who have attained a higher educational qualification, even at later stages in life, display higher levels of political self-efficacy - a sense of being able to influence the government (Desjardins, 2020[20]). In contrast, higher educational attainment does not necessarily translate into higher engagement in volunteering activities (Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). The opportunity cost of time, which is higher for better-educated individuals who earn more and hence, may lose more in terms of earnings if they devote time to volunteering, may explain some of these findings.

Education also plays a key role in reducing criminal behaviour

The effects of education on crime can run through a range of channels. Education increases wages and hence, the opportunity cost of crime. Measures that prevent high school dropout and enhance labour market skills can therefore be very effective at reducing crime. Education also keeps children in the classroom and thereby off the streets where they could get involved in criminal activities. In addition, by keeping children away from potential criminal activities, education helps reduce criminal intensity and the risk that students leave school with a criminal record. Students who remain in school longer leave education with better chances of abiding the law later in life, making education a promising instrument for crime reduction (Lochner and Moretti, 2004[54]; Bell, Costa and Machin, 2022[55]).

In addition, education can also teach individuals how to be more patient and change their preferences towards risk, highlighting the crucial role of socio-emotional skills (Lochner, 2011[50]; Bradley and Green, 2020[16]). In fact, research evidence suggests that socio-emotional skills matter more than cognitive ones for predicting low engagement in criminal activity (Jason Baron, Hyman and Vasquez, 2022[56]; Cunha, Heckman and Schennach, 2010[57]) (OECD, 2021[39]). Early socio-emotional skills are associated with a lower likelihood of individual involvement in crime, delinquent or antisocial behaviour later in life (OECD, 2020[38])).

Fostering the development of socio-emotional skills from an early age can thus translate into lifetime social benefits. For instance, a two-year long training on social skills and self-control targeted at disruptive kindergarten boys from low socio-economic backgrounds helped increase self-control and trust later in life (Algan et al., 2022[58]). The intervention enhanced educational achievement, reduced criminality as young adults and increased social capital in adulthood. Even when the labour market returns to the individual are not accounted for, the benefits of the training programme in terms of reduced education costs (e.g. grade repetition), crime (arrest and court costs) and social transfers already compensate the programme’s costs (Algan et al., 2022[58]).

Crime entails substantial social costs and education’s role in reducing crime translates into social benefits that go beyond the private returns to individuals. Research estimates show that education-related policies can translate into sizeable social benefits (Box 2.2). Increases in years of high school attendance and policies that enhance schooling of individuals who belong to more crime-prone groups (Lochner, 2011[50]). In a similar vein, increases in public school funding – whether these run through operating expenditures (e.g. teacher salaries) or capital expenditure (e.g. building renovations) – that translate into improvements in school can also be a cost-effective crime prevention measure (Jason Baron, Hyman and Vasquez, 2022[56]). In fact, the estimated cost effectiveness of increases in school funding for crime reduction appears to be similar to that of a range of early childhood education interventions (e.g. Head Start in the United States) (Jason Baron, Hyman and Vasquez, 2022[56]; Anders, Barr and Smith, 2022[59]).

Research has often relied on changes to compulsory school leaving laws to examine the role of education for crime reduction and estimate the derived social benefits.

Crime reduction generated by an extra year of schooling generates sizeable social benefits. In a landmark study, Lochner and Moretti (2004[54]) exploited changes in compulsory schooling laws between 1914 and 1974 to examine the effect of educational achievement on criminal activity (probability of incarceration and arrest). They estimate sizeable social externalities from education-generated crime reduction thanks to lower incarceration and victim costs. Social savings associated with a 1% increase in men’s high school graduation rate in 1990 would have amounted to more than USD 2 billion or more than USD 3 000 per additional male graduate (Lochner and Moretti, 2004[54]; Lochner, 2011[50]). The positive externalities in crime reduction generated by an extra male high school graduate accounted for 14-26% of the private returns to high school completion. Increases in high school graduation rates thus appeared to be more cost-effective in reducing crime than policies increasing the size of police forces (when estimates accounted for both crime reduction and productivity enhancement effects).

Accounting for the dynamic persistence effects of education on crime is key for accurate cost-benefit calculations. While Lochner and Moretti (2004[54]) highlighted that a significant part of education’s effect on crime was due to a productivity effect (thanks to higher wages associated with increased education levels), Bell, Costa and Machin (2022[55])show that for compulsory school leaving reforms after the 1980s, education reduced crime mostly by shifting crime-age profiles. Indeed, increases in mandatory schooling reduce crime rates by keeping youth longer in school and preventing them from engaging in criminal activity, but also by reducing the likelihood that individuals engage in crime later in life. Education reforms thus reduce crime at all ages of the lifecycle, with a more pronounced reduction at younger ages.

Thus, more recent reforms led to relatively modest effects on average educational attainment and wages. The more limited contribution to crime reduction of the productivity effect of education raises questions about the net returns of more recent reforms. Using a similar methodology to Lochner and Moretti (2004[54]), Bell, Costa and Machin (2022[55]) show that by age 18, the social benefits of compulsory schooling law reforms just outweigh their costs. However, the benefit-cost ratio of the reforms increases when estimates also consider crime reduction among the older age groups (19-24): the cost-benefit ratio shows a return of USD 2.10 per dollar spent on the reform.

Education helps build social capital and more inclusive and cohesive societies

Education is a strong determinant of trust…

Education is a key predictor of social capital, including actual social relationships and networks (see previous section) and norms of trust and reciprocity that facilitate co-operation between individuals (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020[60]; Algan, 2018[61]). A large literature has documented the role of social capital, and particularly of trust (trust in others and trust in institutions), for economic growth, government performance, financial development or economic exchanges, health-related behaviours, crime and well-being (for a review, see (Algan and Cahuc, 2010[62]; Algan, 2018[61])). During the COVID-19 crisis, social capital has played a mediating role in reducing the spread of the virus (Makridis and Wu, 2021[63]). Individuals in communities with high levels of social capital reduced their mobility directed at retail and recreational activities faster than individuals living in communities with low social capital (Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020[60]). In addition, trust in scientists during the pandemic has shaped support for and compliance with non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g. closing nonessential businesses, implementing a curfew, mandating the use of face masks in public places) and vaccination (Algan et al., 2021[64]).

Trust is the foundation of social capital (Borgonovi and Burns, 2015[65]) and education is one of the strongest determinants of trust. Increases in individual education and in the average level of education of individuals in the surrounding community are associated with higher levels of trust (Helliwell and Putnam, 2007[66]). Education builds the cognitive and socio-emotional skills needed to interpret the behaviour of other individuals and engage in effective collaborations with them (Borgonovi and Burns, 2015[65]). Evidence from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills shows that information-processing skills related positively with trust (OECD, 2019[22]) and that individuals who attain a higher education qualification are more likely to report trust in others than those who did not reach such a qualification (Figure 2.4.). The effect of education on trust appears progressive: each extra qualification is associated with higher levels of interpersonal trust (Borgonovi and Burns, 2015[65]). Moreover, teaching practices matter for the production of such social capital: horizontal teaching practices, such as working in groups, are associated with more pro-social beliefs, including higher levels of trust (Algan, Cahuc and Shleifer, 2013[67]). While only correlational, evidence based on PISA data suggests that education systems could play a key role in rebuilding trust in scientists, which has proved to be an issue during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a significant association at the system-level between students’ performance in science and trust in scientists (Algan, 2021[68]).

…although consensus on the mechanics driving the relationship between education and trust has not been reached

While education and trust display strong positive associations, the research literature has not yet achieved consensus on the mechanisms underpinning this relationship (Borgonovi and Pokropek, 2017[69]). A range of factors can shape the positive association between education and trust. Personal ability and intelligence can support both higher levels of trust and educational attainment. In addition, better-educated individuals may find it easier to trust others if they engage in more social interactions throughout their studies (Yang, 2019[70]). Evidence based on the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) shows that a large part of the association between education and generalised trust is mediated by literacy skills, income and occupational prestige (Borgonovi and Pokropek, 2017[69]).

More generally, the social environment in which individuals evolve shapes the strength of the mechanisms that drives the link between education and trust. Greater birthplace diversity supports a stronger positive relationship between literacy skills and generalised trust, while greater income inequality diminishes the strength of the association (Borgonovi and Pokropek, 2017[69]).The quality of government institutions also matters. Evidence based on European countries shows that at the individual level, increases in education translate into higher levels of social trust when individuals reside in a high-quality institutional setting, with impartial and non-corrupt institutions (Charron and Rothstein, 2016[71])). As individuals get better educated, they also become better aware of favouritism and more likely to detect corruption behaviours, which in turn reduces their level of trust in the absence of high-quality government. As a matter of fact, the role of education for trust tends to become negligible in the absence of impartial and non-corrupt institutions.

Education can also help foster social inclusion and support social mobility…

Education systems can help build more inclusive economies and societies. Social inclusion can be broadly understood as “the process of improving the ability, opportunity and dignity of people, disadvantaged on the basis of their identity, to take part in society” (Cerna et al., 2021[72]; World Bank, 2013[73]). Education can promote equal opportunities for all, and ensuring equity of participation and outcomes in initial education is a first step.

Education participation and attainment have largely increased across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[2]). At the same time, education mobility remains a concern: in the last decades, mobility from the lower and middle education levels to the upper levels has been slowing down (OECD, 2018[74]). Although access to education has largely increased in the past decades, large inequalities by socio-economic status remain in the completion of tertiary education (OECD, 2018[75]), and inequality in education is persistent across several generations (Blanden, Doepke and Stuhler, 2022[76]). Rising inequalities and low social mobility hamper growth and productivity, can translate into rising social tensions and societal divides, while increasing individuals’ exposure to hazards, violence and reduced capacity to fulfil their potential (OECD, 2018[74]).

Inequalities in learning opportunities start early and for students of low socio-economic backgrounds, a great teacher and a good school are often one of the most powerful paths for moving up the social ladder (OECD, 2019[77]). While in many OECD countries, a student’s postal code remains a core predictor of their chances to succeed, evidence from PISA and the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) shows that excellence and equity in education and training systems often go hand in hand (OECD, 2019[77]; OECD, 2019[78]). Indeed, many countries that ensure inclusiveness in skills development also display high levels of foundational skills among their youth, tertiary graduates and adults (OECD, 2019[78]). In contrast, countries that display the lowest equity performance also display low levels of average performance.

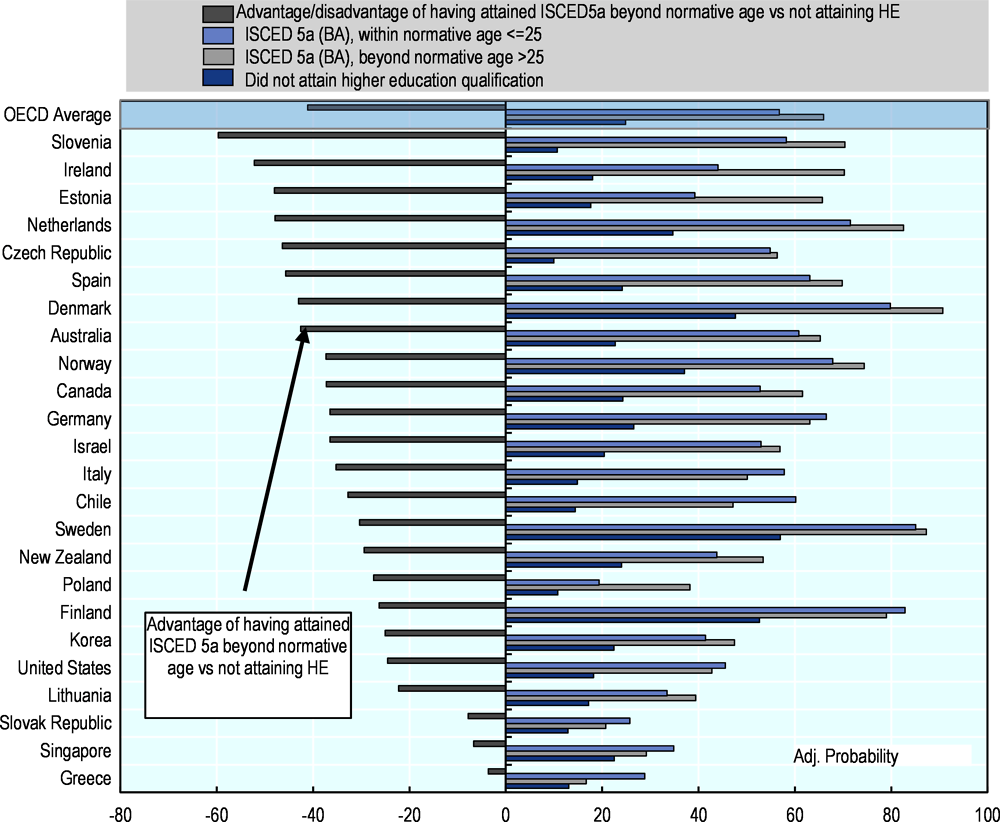

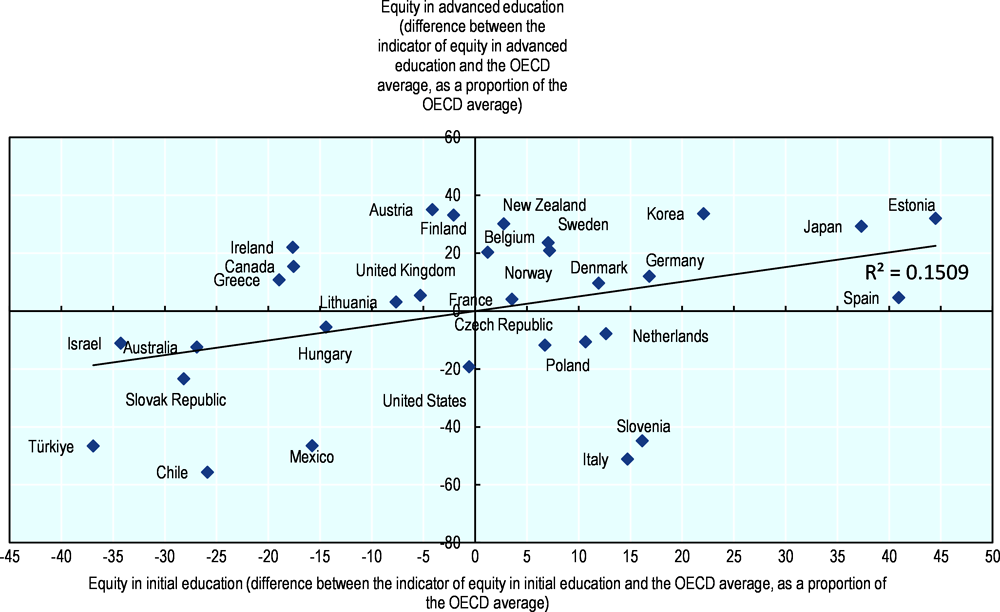

Achieving equity within education systems is a key precondition for achieving equity in subsequent lifetime outcomes. Early intervention is key to break the cycle of intergenerational disadvantage and smoothen lifetime income mobility for individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds (OECD, 2018[74]). Education policies that ensure equitable learning opportunities and outcomes during compulsory schooling can support upward mobility in education and equity in educational attainment (OECD, 2018[75]). While several countries, including Denmark, Estonia, Japan and Korea, maintain equity of learning (in terms of participation and quality) from initial to advanced education, few countries achieve maintaining equity in advanced education in spite of low equity in initial education (Figure 2.5).

…and also help build societies that are more cohesive, through the formation of more tolerant and open-minded individuals

Cohesive societies help support the well-being of their members, fight exclusion and marginalisation, promote trust and foster a sense of belonging, while supporting upward social mobility (OECD, 2011[82]). Beyond its role for trust and well-being, as well as for helping individuals move up the social ladder, education can also support the formation of more tolerant and open-minded individuals and of more cohesive societies as a consequence.

Education is a key determinant of tolerance and low levels of discriminatory attitudes. Research evidence suggests that lower education levels are associated with greater levels of in-group favouritism, prejudice, ethnic exclusionism, xenophobia and negative attitudes towards immigrants (for a review, see (Easterbrook, Kuppens and Manstead, 2016[83]; Mezzanotte, 2022[84]; Borgonovi and Pokropek, 2019[85])). Encouragingly, across OECD countries, most students are interested in learning about other cultures and students who are different from them. Such an interest is positively associated with students’ respect for people from other cultures and awareness of intercultural communication (OECD, 2020[86]). A range of education activities can foster students’ global competence or capacity to live in a diverse and interconnected world. Indeed, students’ interest in learning about other cultures, their ability to understand different perspectives and their awareness of intercultural communication are all positively associated with the number of learning activities related to such topics they engage in at school (OECD, 2020[86]).

Hence, through its socialisation role, education helps improve communication in society between individuals with different backgrounds (e.g. socio-economic, cultural, and religious), with implications for economic growth (Gradstein and Justman, 2002[87]). Beyond a socialisation role, education can also help reduce perceptions of economic or cultural threat and thereby translate into more tolerance towards individuals who are different. Evidence based on cross-country data suggests that better-educated individuals display lower opposition to migration than lower-educated ones and that this increased acceptance levels are largely due to lower feelings of threat (Borgonovi and Pokropek, 2019[85]).

As economies and societies are becoming more digital than ever, it is critical to ensure that everyone can thrive in the digital age

The pandemic has accelerated the digitalisation of economies and societies, and countries’ preparedness to seize the benefits of a digital world largely depends on their populations’ skills (OECD, 2019[1]). To thrive in a digital world, individuals need a well-rounded set of skills, including good cognitive and digital skills, and the socio-emotional skills that enable them to be flexible, adapt and manage change.

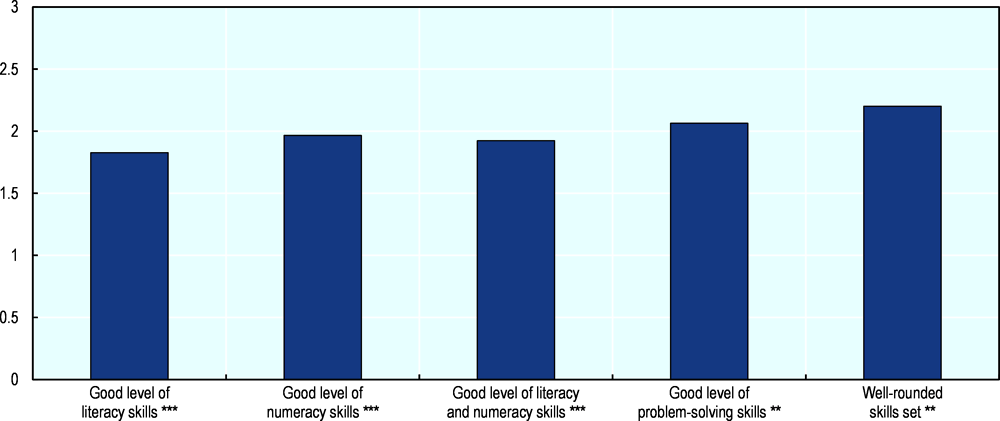

Skills help bridge digital inequalities in access, use and outcomes derived from the use of digital technologies. Increasingly, a lack of skills has become a major source of digital divides in access to Internet. Among European households who lack Internet access, many more report lacking access (44% in 2019) because of a lack of skills than before (32% in 2010) (Eurostat, 2021[88]). In addition, skills shape how effectively individuals can engage in digital societies (OECD, 2019[1]). A well-rounded set of skills enables individuals to move from a simple use of Internet for information and communication to a more complex use, encompassing learning online, e-finance or creativity-related tasks (Figure 2.6. ). Not all individuals need to perform such tasks but as societies go digital, individuals may be required to do so and hence, should have the necessary skill set to adapt. Such gaps in uses are also likely to translate and reflect well-being divides between low and high-skilled individuals. Evidence from Internet search engine data from the United States reveals that searches associated with job search, civic participation and healthy habits consistently predict well-being (Algan et al., 2019[89]). While job search is negatively associated with well-being, civic engagement is associated with higher life evaluation and healthy habits, higher positive affect and lower negative affect.

During the pandemic, digital skills have made a difference to continue engage in society, work, learn and to access health care online…

During the pandemic, many public and private services have moved online. Having a well-rounded level of skills has made a difference between continuing to engage in society, work, learn and access health care, and being left out or left behind. Already before the pandemic, lower-educated individuals were more likely to feel left out of society and this perception has become more acute during the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2021[8]). While a range of factors may have triggered this feeling, digital divides that prevented individuals from connecting to other people or accessing a range of services during lockdowns are likely to have exacerbated this perception. Without basic skills, individuals are locked out of the benefits of an increasingly digital world. Lacking basic literacy and numeracy skills constitutes a barrier to performing activities online, while lacking problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments is a barrier to performing more diverse and complex activities (OECD, 2019[1]).

Digital skills are also important to protect against the risks associated with digital technologies…

Skills also enable individuals to better protect themselves – and their children – against any risks associated with digital technologies. The increasing use of digital devices and Internet may be detrimental to individuals’ well-being and social relationships. While a causal relationship has been challenging to establish, evidence suggests that excessive uses of digital technologies are associated with lower life satisfaction, increased risk of depression and anxiety, lower sleep quality and higher prevalence of negative feelings (e.g. feeling sad and miserable) (OECD, 2021[90]; Hooft Graafland, 2018[91]; OECD, 2019[44]).

Better-educated- individuals are potentially better informed about digital-related risks, have access to other non-digitally based activities during their leisure time, or are more careful about their online engagement. Students who perform better in the PISA assessments are, for instance, less likely to report feeling bad without an Internet connection (OECD, 2019[1]). In addition, skills also shape how individuals take care of their online safety and data privacy. A good level of skills increases the likelihood that individuals take action to enhance their online security by managing access to their personal information, using anti-tracking software or changing settings to limit cookies (OECD, 2019[1]). Digital skills also help children to better cope with cyberbullying, for instance by enabling them to take the necessary actions to block senders and delete messages (Gottschalk, 2022[92]).

By integrating digital technologies in teaching and learning, education can help build the skills needed for a digital world and bridge divides…

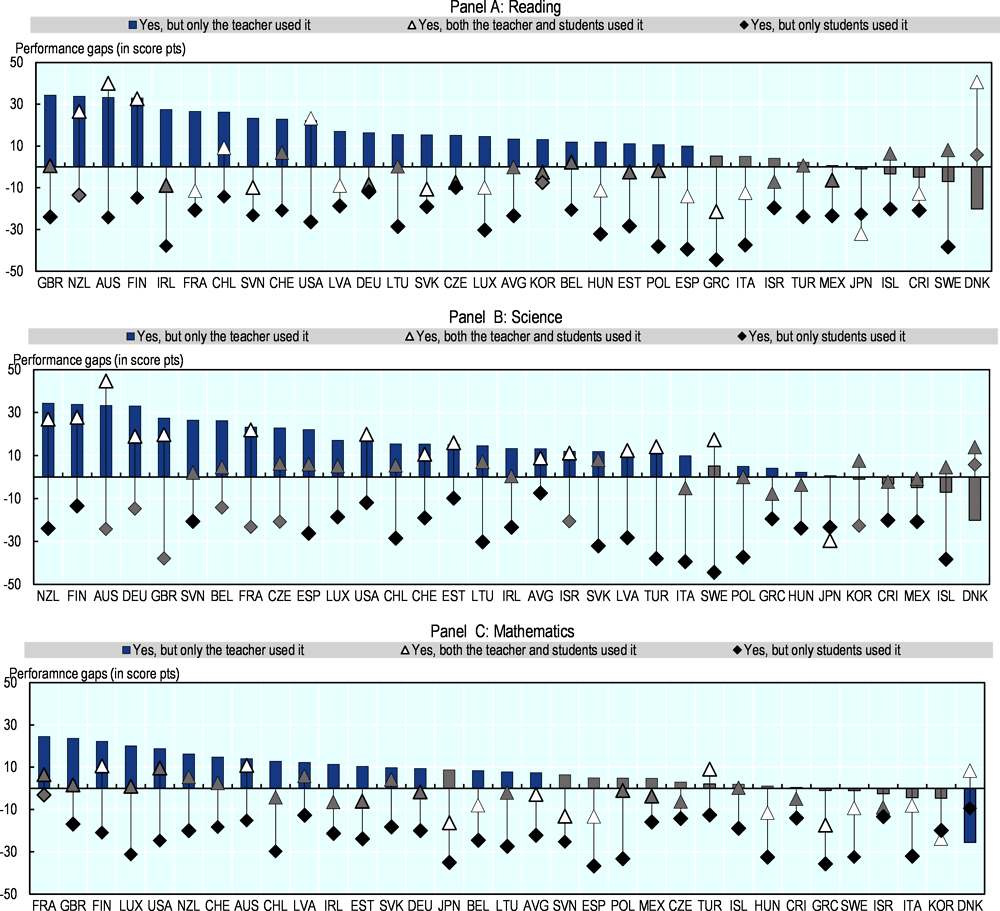

Education systems play a key role in laying the foundations for thriving students and citizens in an increasingly digital world. Beyond seeking to equip students with a well-rounded mix of skills and learning attitudes, education systems have equally focused their efforts on integrating digital technologies in students’ learning. The introduction and use of digital technologies and Internet in schools has been one of the main drivers of innovation in education practices observed in the past decade in OECD countries (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019[93]) and the pandemic has further boosted the digital transformation of education systems. Data from PISA (2018) show that on average across OECD countries, around two-thirds of students had experienced the use of digital devices as part of their science, reading or mathematics classes in the previous month3. In science, such uses were in most cases performed either by teachers and students together (for 31% of all science students) or teachers only (for 31% of all science students) in contrast to student-led uses (for 12% of all science students).

The use of digital technologies in education systems can be part of the solution for building the skills needed for a digital world, including digital skills. Although children are exposed to digital technologies from an ever earlier age, not all young individuals are technologically savvy and the use of digital technologies in schools can enhance students’ digital skills (OECD, 2015[94]; OECD, 2017[95]) (Malamud and Pop-Eleches, 2011[96]; Malamud et al., 2018[97]; Bulman and Fairlie, 2016[98]). Evidence from PISA (2018) shows that students who had more opportunities to learn digital skills at school are more likely to perform well in emergent aspects of reading, such as distinguishing fact from opinion (OECD, 2021[47]). While divides in access to digital technologies at home persist in many OECD countries, schools can help bridge inequalities in students’ access to such technologies and in the extent to which they seize their benefits for learning.

Digitalisation also provides new opportunities for education systems to shift away from a “one-size-fits-all” teaching approach to personalised learning experiences. Smart uses of digital technologies hold great potential in terms of inclusion, through adaptive learning, enhanced personalisation of learning experiences, access to a greater array of learning resources and equipment (e.g. through remote laboratories), or the use of Artificial Intelligence-based tools to accompany instruction with diagnosis and personalisation. Learning analytics4, based on big data gathered from online navigation, social networks or networked devices and sensors, also support the development of more personalised learning experiences (OECD, 2019[99]; OECD, 2021[100]). These allow for easier identification of students at risk of dropout and assessment of the effectiveness of a variety of teaching strategies. Such innovative uses of data and digital technologies in education systems provide pathways for more inclusive and high-quality learning experiences.

The use of digital technologies in teaching and learning can enhance student academic performance, but many countries are yet to reap the benefits of digital education

Indeed, when technology enters teaching and learning practices in innovative ways, it can translate into higher student performance and engagement (Paniagua and Istance, 2018[101]; OECD, 2019[1]; OECD, 2021[100]). Evidence from PISA (2018) shows that the use of digital devices as part of teaching activities can support better student performance, although not all education systems have managed to tap into the potential of digital technologies for effective teaching and learning (Figure 2.7).

PISA data also suggests, however, that seizing this potential depends on how technology is being used in the teaching and learning process and the underlying pedagogical intent. Indeed, teacher-led and (though to a somehow lesser extent depending on countries) combined student-teacher uses of digital devices for learning tend to be more positively associated with student performance than student-led uses of digital devices, even after accounting for students and schools’ socio-economic background, school digital infrastructure or student perceived digital competence. In Australia and New Zealand, countries where combined teacher-student uses of digital technologies are very frequent (OECD, 2021[47]), such uses also display the largest association with student performance relative to the other types of digital devices use, suggesting that students in these countries are seizing the benefits of digital technologies through enhanced instructional practices. More generally, these findings are in line with research evidence pointing at the importance of engaging teachers in the use of digital technologies rather than sidestepping them, and building capacity within the education system for the pedagogical use of digital technologies instead of merely focusing on digital infrastructure availability (Beg et al., 2022[102]; Sailer, Murböck and Fischer, 2021[103]).

In contrast, student-led uses of digital technologies tend to display mostly negative associations with student performance, suggesting that students may not perform the most productive uses of digital tools, particularly if teachers do not oversee or guide student use and students get distracted or make passive uses of technology. At the same time, student-led uses tend to be more recurrent in socio-economically disadvantaged schools than advantaged ones on average across OECD countries5. The potential of digital technologies for inclusion and bridging learning gaps may therefore not be reached in the absence of policies that support more innovative uses of digital technologies in disadvantaged schools (e.g. through targeted teacher professional learning opportunities, provision of external expertise and guidance for the introduction of digital technologies in teaching and learning, development of students’ digital skills).

Evidence from Figure 2.7 also shows that countries have unequally seized the benefits of the digital transformation in their education systems. The average positive associations between teacher-led or combined student-teacher uses of digital devices in teaching and learning suggest that there is great potential for most countries to further leverage the digital transformation in education, but that countries need to adopt a range of policies to support effective digital education. Students in a number of education systems, including Australia, Finland, New Zealand or the United Kingdom, appear to derive more substantial benefits from teacher-led and combined student-teacher uses of digital devices in contrast to their peers in other OECD countries. Evidence from TALIS (2013) shows that Australia, Finland, New Zealand or the United Kingdom were also ahead already in 2013 in terms of the preparation and training of their teachers for digital technologies use (OECD, 2019[1]). These countries have likely managed to design a digital education policy ecosystem (including polices to ensure the availability of digital education infrastructure and foster innovation in digital education technologies, capacity building to ensure their effective use, etc.) that enables more effective and innovative uses of digital technologies for learning and teaching.

The challenges and opportunities of our times require, more than ever, developing resilient and proactive citizens for a sustainable future

Education plays a key role in raising awareness and sensitivity about a range of global and environmental issues…

Education is instrumental in raising awareness and sensitivity about a range of global issues and forming citizens who are prepared to live and act for a sustainable future. Skills shape students’ and citizens’ ability to live in an interconnected world and take action for collective well-being (OECD, 2020[86]). Building a sustainable future also requires behavioural changes, understanding and acceptance of climate action policies.

The PISA 2018 assessment has examined the competences students need to develop to be able to thrive in a diverse and interconnected world. Students who display higher values in indices that reflect their attitudes and dispositions regarding global issues (e.g. awareness of global issues, interest in learning about other cultures, cognitive adaptability) are more likely to report that they take actions for collective well-being and sustainable development (OECD, 2020[86]). Such positive attitudes and dispositions regarding global issues are positively related to students’ global competence test performance. While positive attitudes and dispositions towards global issues are likely to shape students’ motivation and performance in learning about these topics, it is also likely that better understanding such issues can result in more positive dispositions and likelihood that students take action.

When it comes to students’ preparedness for building a sustainable future in particular, evidence from several PISA rounds highlights that students’ environmental awareness and pro-environmental attitudes are positively associated with their science performance (OECD, 2021[6]). Students with a better understanding of science are thus more likely to be environmentally aware and equally display a deeper sense of responsibility for sustainable development issues (OECD, 2021[104]; Echazarra, 2018[105]). The number of science activities in which students participate at school and their exposure to enquiry-based teaching also matter for their attitudes towards the environment. More generally, students’ attitudes regarding global issues relate positively with the number of global competence activities they engage in at school, even after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile (OECD, 2020[86]).

Students’ awareness of environmental problems is strongly associated with the content of students’ curriculum…

Beyond learning activities organised in schools, the content of formal curricula can also help improve students’ awareness of and attitudes towards such issues. A number of countries (e.g. Australia, Denmark and Estonia) already prioritise environmental awareness and stability among their education goals (OECD, 2020[5]). Evidence from PISA 2018 shows that almost all students have environmental issues included in their curricula and that including such topics in the curriculum matters. Students’ awareness of climate change and global warming is strongly associated with their inclusion in students’ curriculum on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[86]). At the same time, students’ environmental sustainability competence displays large overall variance and a high level of general educational achievement is not sufficient for developing greater awareness of environmental problems (Borgonovi et al., 2022[106]; Borgonovi et al., 2022[107]). In contrast, being a top performer in science is positively associated with higher levels of environmental awareness even after accounting for students’ reading and mathematics achievement. These findings highlight the importance of the content of education curricula, and of science education in particular, for equipping students with the relevant skills needed to promote a sustainable future (Borgonovi et al., 2022[106]; Borgonovi et al., 2022[107]).

But educating citizens who take action for a sustainable future also requires developing students’ agency and sense of empowerment

To form citizens who can promote a sustainable future, education systems also need to focus on developing students’ agency and sense of empowerment that enable them to take impactful actions for the future (OECD, 2021[104]). Although students have a high level of awareness, self-efficacy and interest in environmental issues, only one in two students feels that they can do something about the problems of the world (OECD, 2021[104]). Students with higher levels of science proficiency tend to be more pessimistic about the future of the environment. While complacency with environmental issues may be problematic, pessimism about the future that impedes students to take action is equally undesirable (OECD, 2021[104]; Echazarra, 2018[105]).

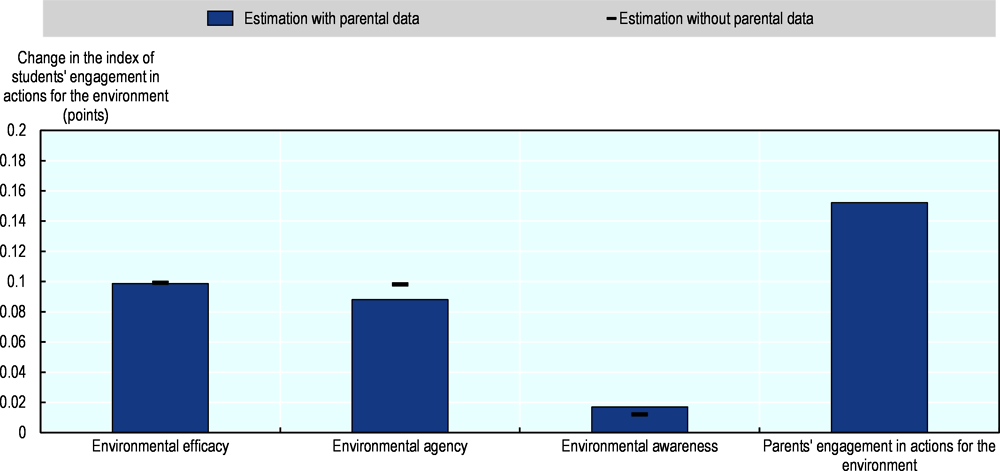

Educating students and citizens for a sustainable future thus requires going beyond the core set of knowledge and skills related to environmental issues. Building a sense of empowerment and resilience is crucial. Indeed, students who display a higher sense of agency and self-efficacy regarding the environment are more likely to take action for the environment (Figure 2.8). Specific pedagogies such as learning in real-life contexts, project- and enquiry-based learning, and discussion-based teaching can be effective at developing both knowledge and students’ agency and confidence to take action (OECD, 2021[6]). Evidence in Figure 2.8 shows that students’ engagement in actions for the environment also relates to their parents’ engagement in such actions. Whether this positive association reflects the crucial role played by parents in the socialisation of their children or the scope for children to shape their own parents’ participation in actions for the environment, it highlights the need for education systems to involve parents and caregivers in the development of children’s skills for a sustainable future (Borgonovi et al., 2022[107]).

In addition, evidence from PISA (2018) shows that building students’ cognitive adaptability can be a pathway for fostering resilience, a capacity to deal with uncertainty and an ability to understand different perspectives (OECD, 2020[86]). Indeed, cognitive adaptability refers to students’ ability to adapt their “thinking and behaviour to the prevailing cultural environment or to novel situations and contexts that might present new demands or challenge” (OECD, 2020[86]). Students’ cognitive adaptability and resilience are positively associated across all countries and other participants in PISA 2018, even after accounting for students and schools’ socio-economic profiles.

Education systems thus play a major role in nurturing resilient learners who can tackle disruptions and adapt to changing environments, capitalise on existing opportunities and reach their potential (OECD, 2021[45]). Most countries/jurisdictions with available data in the OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030-Curriculum database embed student agency concepts in around one-third of their curricula and not all teachers feel prepared to support the development of student agency (OECD, 2020[7]). Beyond the inclusion of student agency in future-oriented curricula and support for teachers’ professional learning, a range of other approaches can foster learners’ resilience and ability to shape a sustainable future. Education systems that foster student agency are those where teachers and students co-construct active learning environments instead of putting teacher-led instruction at the core (Schleicher, 2021[108]). In addition, policy efforts that encourage student engagement and nurture positive learning climates, provide adaptive pedagogies for all and support to the most vulnerable learners can equally help develop more resilient students (OECD, 2021[45]). Empowering learners to navigate confidently in uncertain and changing worlds also requires a whole-child approach of education that brings together the development of students’ social and emotional skills, their well-being and mental health (OECD, 2021[45]).

Overall, high-quality education pays off for individuals, communities and societies in significant and diverse ways. It is thus important, when considering public investments in education, to go beyond the sole economic benefits, and to also consider its many broader social outcomes and education’s contribution to thriving individuals and societies.

Better-educated individuals live healthier and longer lives. They display higher levels of self-reported health, with externalities on their children and peers, and by age 25, those with tertiary education benefit from a 5 to 8 years life expectancy premium relative to their low-educated peers. They also enjoy happier lives, as education helps build the skills, knowledge and attitudes that support individuals’ mental health and psychological well-being in adulthood.

Education also supports civic engagement and reduces antisocial behaviour to the benefit of society. Analytical, information-processing and critical-thinking skills developed in school build more enlightened and engaged citizens and, in turn, better-functioning democracies. Education also develops tolerance and open-mindedness as a basis for more cohesive societies. Cognitive and socio-emotional skills also play a key role in reducing criminal behaviour, translating into lower crime-related costs and large social benefits.

In addition, education helps build social capital and more inclusive societies. It is a strong determinant of trust, which constitutes the foundation of social capital and holds key implications for economic growth, government performance, economic exchanges, health and well-being. In addition, education systems can support more inclusive economies and societies through social mobility. Achieving equity within education systems is a key precondition for achieving equity throughout an individual’s learning pathway, and across generations.

Last but not least, sustained high-quality education also helps individuals and communities make the most of new opportunities, such as the digital transformation, and proactively addressing emerging challenges, such as climate change. Education and skills have made a difference during the pandemic to continue engage in society, work and learn, and not be left behind in an increasingly digital world. By integrating digital technologies in teaching and learning, education can help build the skills needed for a digital world and bridge divides. In addition, education plays a key role in raising awareness and sensitivity about a range of global and environmental issues. Developing students’ agency and sense of empowerment that enables them to take impactful actions for the future is critical for building proactive citizens who take action for a sustainable future.

The broader social outcomes of education thus include both private benefits (e.g. better health, better opportunities for one’s children) and societal ones, as private benefits translate into positive externalities and collective benefits. While many such returns can be considered as outcomes in themselves, they also yield economic and monetary benefits, albeit in indirect ways, thereby strengthening the economic returns to education discussed in Chapter 1.

References

[11] Agencia de Calidad de la Educacion (2019), Resultados Educativos 2019, http://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/PPT_Nacional_Resultados_educativos_2019.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

[10] Agencia de la Calidad de la Educacion (n.d.), Simce, https://www.agenciaeducacion.cl/simce/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

[68] Algan, Y. (2021), “Confiance dans les scientifiques par temps de crise”, Conseil, No. 068, Conseil d’Analyse Economique, https://doi.org/10.21410/7E4/EATFBW.

[61] Algan, Y. (2018), “Trust and social capital”, in Stiglitz, J., J. Fitoussi and M. Durand (eds.), For Good Measure: Advancing Research on Well-being Metrics Beyond GDP, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[58] Algan, Y. et al. (2022), “The Impact of Childhood Social Skills and Self-Control Training on Economic and Noneconomic Outcomes: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment Using Administrative Data”, American Economic Review, Vol. 112/8, pp. 2553-2579, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200224.

[62] Algan, Y. and P. Cahuc (2010), “Inherited Trust and Growth”, American Economic Review, Vol. 100, pp. 2060-2092, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/aer.100.5.2060 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

[67] Algan, Y., P. Cahuc and A. Shleifer (2013), “Teaching Practices and Social Capital”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 5/3, pp. 189-210, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.5.3.189.

[64] Algan, Y. et al. (2021), “Trust in scientists in times of pandemic: Panel evidence from 12 countries”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 118/40, https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.2108576118/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL.

[89] Algan, Y. et al. (2019), “Well-being through the lens of the internet”, PLoS ONE 14(1): e0209562, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209562.

[3] Almlund, M. et al. (2011), “Personality Psychology and Economics”, Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 4, pp. 1-181, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53444-6.00001-8.

[59] Anders, J., A. Barr and A. Smith (2022), “The Effect of Early Childhood Education on Adult Criminality: Evidence from the 1960s through 1990s”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, https://doi.org/10.1257/POL.20200660.

[51] Apergis, N. (2018), “Education and democracy: New evidence from 161 countries | Elsevier Enhanced Reader”, Economic Modelling 71, pp. 59-67, https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0264999317313561?token=2623B634446474B455767E785BA8C409637316F7587F02051199A98B775F5C8B5F435E5DF9A57C6700E3061BA0A2D851&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20220124153820 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

[102] Beg, S. et al. (2022), “Engaging Teachers with Technology Increased Achievement, Bypassing Teachers Did Not”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 14/2, pp. 61-90, https://doi.org/10.1257/POL.20200713.

[55] Bell, B., R. Costa and S. Machin (2022), “Why Does Education Reduce Crime?”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 130/3, pp. 732-765, https://doi.org/10.1086/717895/SUPPL_FILE/20200833APPENDIX.PDF.