1. Key Policy Insights

The Danish economy has recovered quickly from the COVID-19 crisis. Rapid action to support firms and households contained the economic contraction to one of the mildest in Europe, while fast vaccine rollout enabled the removal of shutdown restrictions and an early reopening. Policy support should continue to be removed where activity has recovered, though the uncertain worldwide health and economic situation warrants ongoing flexibility. Monetary policy is set to remain strongly expansionary, increasing the importance of being ready to tighten macroprudential regulation if risks from rapid house price appreciation continue to build. The crisis was worse for the young, the foreign-born and those with low educational attainment. While employment rates for these groups have now recovered, policy should return to addressing long term structural issues facing these groups, such as helping the labour-market entry of young people and improving the integration of migrants.

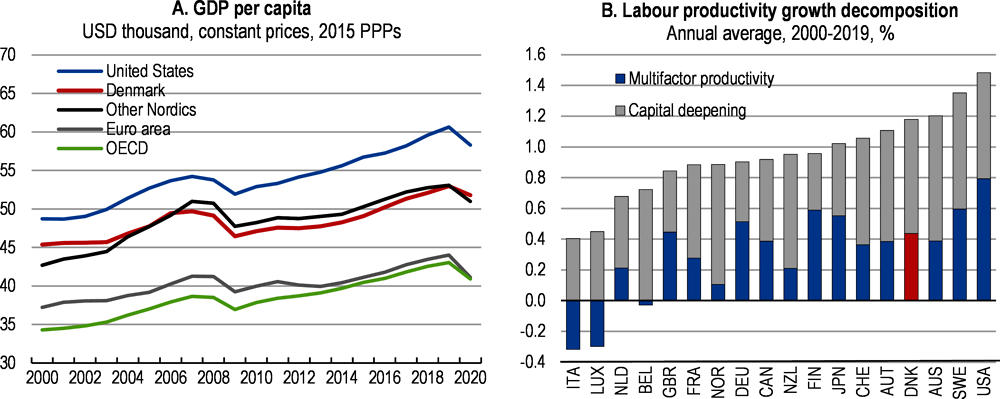

The Danish economy performed solidly in the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, with real GDP growth averaging 1.8% per year driven primarily by labour productivity growth (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Successive Danish governments have favoured policy settings that have led to high labour-market flexibility, market competition, strong adoption of digital tools and a business-friendly climate, which have underpinned investment and productivity (Figure 1.1, Panel B). This has been done while reducing environmental damages and maintaining social policies conducive to high inclusiveness.

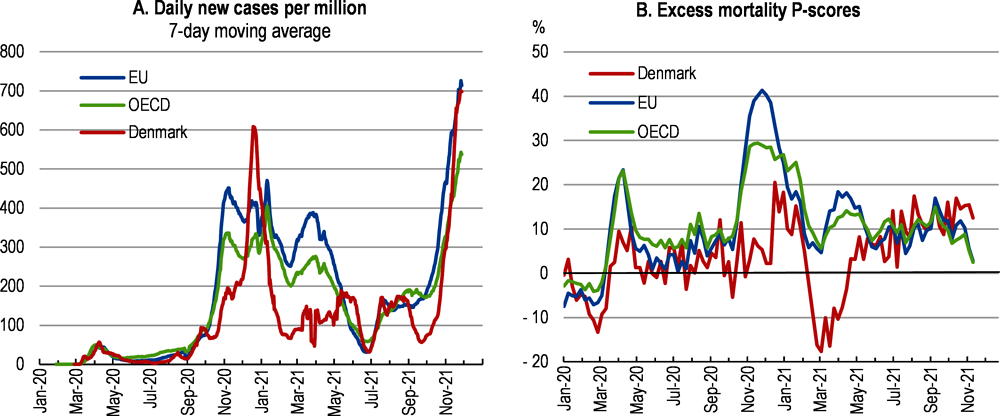

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused substantial disruption and loss of life. Denmark suffered a first wave of cases in the second quarter of 2020, a more deadly second wave in early-2021, and a resurgence in late 2021 linked to the spread of the virus’s Delta variant. Thanks to rapid action to control the virus and strong fiscal support, the contraction of activity and employment has been milder than expected. Progress in health protocols, together with high vaccination rates, allowed an early reopening of the economy. Activity bounced back in the second quarter, with GDP and employment surpassing pre-crisis levels, and growth is projected to remain solid in the absence of further worsening in the health situation.

Government measures have helped those who were hit the hardest by the crisis. Young people (those aged 15-34) and the foreign-born saw the biggest declines in employment at the height of the crisis, though employment for these groups had recovered by mid-2021 (Statistics Denmark, 2021[1]). The loss of employment during the crisis was also severe among those with low educational attainment, in contrast to employment gains recorded for people with tertiary education (Statistics Denmark, 2021[1]).

In the short term, Denmark is withdrawing exceptional support for liquidity, households and the health system, while keeping some funds in reserve in case further COVID-related spending is necessary. Once the recovery is well established, it should resume its strong focus on structural changes to achieve strong, resilient and inclusive post-pandemic growth. Medium-term objectives include climate policy, preparing for an ageing population, and accelerating the country’s digital transformation. While Danish firms are overall well placed to benefit from digital transformation, more could be done to boost the diffusion of ICT tools and productivity.

Lowering carbon emissions is at the heart of the recovery strategy. Denmark has had considerable success in reducing its greenhouse gas emissions over the past decade. To continue this trend, the Climate Act adopted by Parliament in 2020 has set an ambitious legal obligation to reduce carbon emissions by 70% relative to 1990 by 2030 – one of the most ambitious abatement objectives among OECD countries. Denmark intends to lead by example and to encourage other countries to follow its course. However, such deep cuts in emissions will be difficult to achieve with existing technologies, and failing to prioritise the most cost-effective abatement opportunities would increase costs from the transition. Designing climate policies that minimise adverse economic and social consequences will therefore be crucial, though there will still be a structural adjustment challenge as decarbonisation creates winners and losers (Chapter 2). In theory, high carbon prices encourage efficient cuts in emissions, but they often face low acceptability by households, even in Denmark, and as for other environmental policy measures, they can affect competitiveness of trade-exposed firms. As a first step, emission pricing should be made more uniform through a minimum price of EUR 60 per tonne of CO2e, complemented by measures to mitigate social impacts. They should continue to be complemented by measures to accelerate private investment in low-carbon activities such as easier regulatory measures to facilitate market entry, public investment in green networks, and support to research and development in clean technologies.

Cutting emissions from energy, transport and agriculture will be particularly challenging. These sectors face large transformations – both challenges and opportunities (Chapter 3). For these transformations to be economically sustainable, a supportive policy environment should facilitate the emergence of new and innovative firms that challenge incumbents, flexibility to reallocate labour and capital, and support for reskilling displaced workers. The Danish system of “flexicurity” has been well-suited to similar challenges in the past, and should once again be helpful. While Denmark can act on its own in many areas, it will need to take into account policy changes at the broader level of the European Union, which are likely to be important, though future EU climate policies remain uncertain at present.

Against this background, the key messages of this Economic Survey are that:

Denmark weathered the COVID-19 crisis relatively well and has returned to solid growth. Withdrawal of exceptional fiscal support is warranted, but the government needs to be ready to restore substantial stimulus should the health situation unexpectedly deteriorate. As the recovery is now well established, structural reforms should once again be the main driver of strong and sustainable growth.

The crisis was worse for the young, the foreign-born and those with low educational attainment. While employment rates for these groups have now recovered, policy should return to addressing long term structural issues facing these groups, such as helping the labour-market entry of young people and improving the integration of migrants. Further progress in reducing gender gaps is also a priority.

Denmark has made the commendable commitment to cut its carbon emissions rapidly. However, achieving deep cuts while managing the socioeconomic consequences will be a challenge. The focus needs to be put on encouraging private investment and innovation in clean technologies. A just transition should help those adversely affected by climate policy.

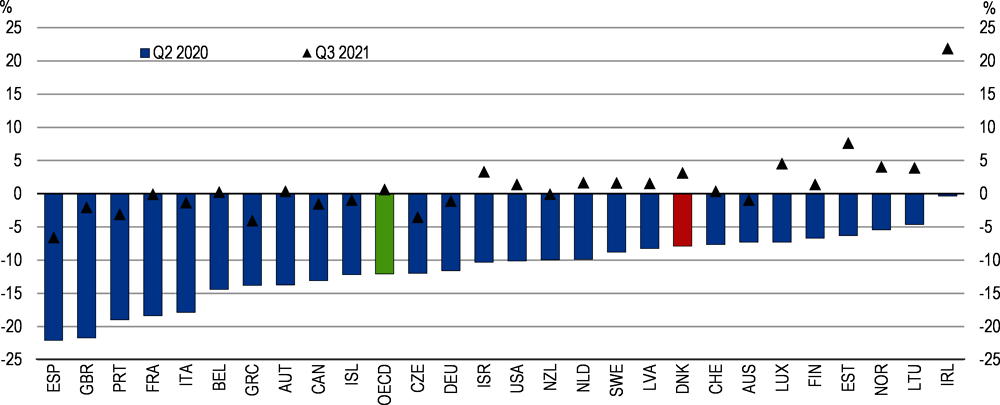

Denmark weathered the COVID-19 crisis better than other countries, as rapid action to contain the spread of the virus in March 2020 and again in December 2020 was successful in quickly bringing down the number of cases (Figure 1.2, Panel A) and containing mortality (Figure 1.2, Panel B). Combined with one of the fastest vaccination rollouts in the EU, this provided space to ease containment measures earlier than in many countries, though uncertainties prevail regarding future virus mutations and the situation is still precarious. Proof of vaccination or a recent negative test was again required for visits to restaurants, travel and large events as Delta variant case numbers rose rapidly in late 2021. While there was a substantial contraction of GDP in 2020 and a further decline in the first quarter of 2021, the economic hit was less than in most European countries (Figure 1.3).

The collapse in foreign demand, particularly for services, played a large part in the 2020 economic contraction (Table 1.1). The decline in private consumption was one of the smallest among OECD countries and investment expanded, driven by strong growth in housing construction (+6.9%) and public investment (+9.8%). Final domestic demand was down just 0.8%, with net exports responsible for the majority of the contraction in GDP. This reflected a smaller effect of the first wave of the virus within Denmark, with bigger contractions in major trading partners translating to lower external demand, even as the composition of Danish exports increased resilience (see below). Exceptional fiscal support supported domestic demand during 2020, in particular via wage subsidies and disbursement of frozen holiday allowances (Box 1.1).

Initial broad support for badly affected firms and households

The Danish Government acted quickly and decisively to provide fiscal support during the crisis. Throughout 2020, VAT and tax payments for firms of DKK 276 billion (11.8% of GDP) were postponed. In 2021 tax payments for firms of a further DKK 57 billion (2.3% of GDP) were postponed. The last postponed tax payment has been deferred until January 2022. Firms have also had the opportunity to apply for interest-free loans from the Danish government for VAT and tax payments for a total amount of DKK 258 billion (10.6% of GDP) from April 2020 to June 2021. Firms have received loans for a total amount of DKK 36.1 billion (1.5% of GDP). The loans were initially planned to be due for repayment from November 2021 to May 2023. To provide further liquidity, repayment dates for DKK 20.8 billion (0.9% of GDP) of loans for have been postponed to begin from April 2022.

In addition to the measures to improve liquidity through deferred payments and loans, compensation has been provided to firms and self-employed people with declines in turnover of at least 30%, later increased to 45% at an estimated cost of DKK 79 billion (3.4% of GDP) as of June 2020. This compensation was subsequently extended, specifically to companies affected by restrictions between September and December 2020 and more broadly from December 2020 to June 2021. Entitlement periods for unemployment and sick leave benefits were frozen and job search requirement cancelled.

Wage compensation was made available for employees of firms experiencing large falls in demand, with the government covering at least 75% of salary for hours not worked. Following extensions, wage compensation expired on 31 August 2020 but was reintroduced in December 2020 and ran until 30 June 2021. Two loan guarantee schemes were launched, with DKK 66 billion (2.8% of GDP) in off-balance sheet funding. Additional measures to support the financial system included release of the counter-cyclical capital buffer and extraordinary lending facilities from the central bank.

Subsequent stimulus packages targeted household incomes and green investment

A further stimulus package was agreed in June 2020, totalling around 2.5% of GDP in 2020 and 0.8% in 2021, including some previously announced and off-budget measures. Releasing holiday allowances from mandatory pension savings boosted household income by about 1½ per cent of GDP after tax. Frontloading of energy renovation of social housing was expected to boost investment by 0.2% of GDP in 2020 and 0.4% in 2021. A one-off payment of DKK 1000 to transfer recipients was estimated to cost DKK 2.3 billion (0.1% of GDP). The package also included a temporary increase in the R&D enhanced tax allowance to 130% in 2020 and 2021 (later extended to 2022) for R&D expenses up to DKK 850 million.

Finally, in December 2020 the green recovery package for 2021-22 passed at an estimated cost of 2.6% of GDP, partly funded by EU Recovery and Resilience Facility grants. This package included another disbursement of holiday allowances in March 2021, expected to boost incomes by DKK 22 billion (0.9% of GDP) after tax. More funds were allocated to support firms affected by restrictions over the winter and for investments that reduce greenhouse gas emissions in energy, buildings, transport and agriculture. About 0.7% of GDP was allocated in 2021 to compensate the mink industry, which had to cull its stock in late 2020 following infection with a mutated strain of COVID-19. Further funding was provided to increase the generosity of the “housing-job scheme”, which gives tax deductions for household services such as cleaning and childcare and for the costs of energy saving renovations of private homes.

Actual expenditure in 2020 was well below expectations and small by international comparison

As of June 2020, the Ministry of Finance estimated the cost of COVID packages at DKK 125 billion (5.4% of GDP). Despite extension and expansion of aid, total expenditure in 2020 has been tentatively estimated by the Danish Economic Councils (2021[2]) at less than DKK 50 billion (2.2% of GDP). Public consumption, wage compensation and transfers increased roughly in line with expectations, but compensation to badly affected firms and calls on guarantee schemes were substantially less than expected. After accounting for the fall in revenue, the budget balance declined by almost 5% of GDP in 2020, which is large historically but among the smallest declines in OECD countries.

Source: Danish government information releases; Danish Economic Councils (2021[2]); OECD Economic Outlook database.

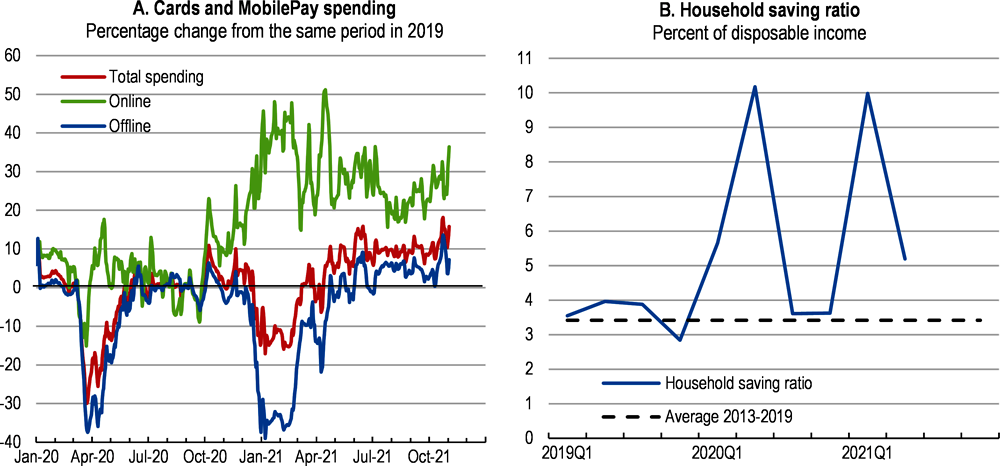

A rapid recovery in consumption began in March 2021 as virus containment measures eased (Figure 1.4, Panel A). Household consumption exceeded the pre-crisis (2019) level in the second quarter of 2021. However, spending was roughly flat from the start of June as the immediate rebound ended, and additional savings built up during the crisis had not yet been spent by mid-2021 (Figure 1.4, Panel B). While the decline in private consumption during the crisis was smaller than elsewhere, forced saving during lockdowns in conjunction with an increase in government transfers to households saw a considerable increase in the household saving rate, which reached its highest level in at least 20 years during the second quarter of 2020 and again in the first quarter of 2021. The rapid rebound in consumption spending as constraints ease is consistent with the small role of precautionary saving (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2021[3]), reflecting the relatively milder downturn in Denmark and strong social safety net. Consumer confidence has also recovered, turning positive in May for the first time since the pandemic began.

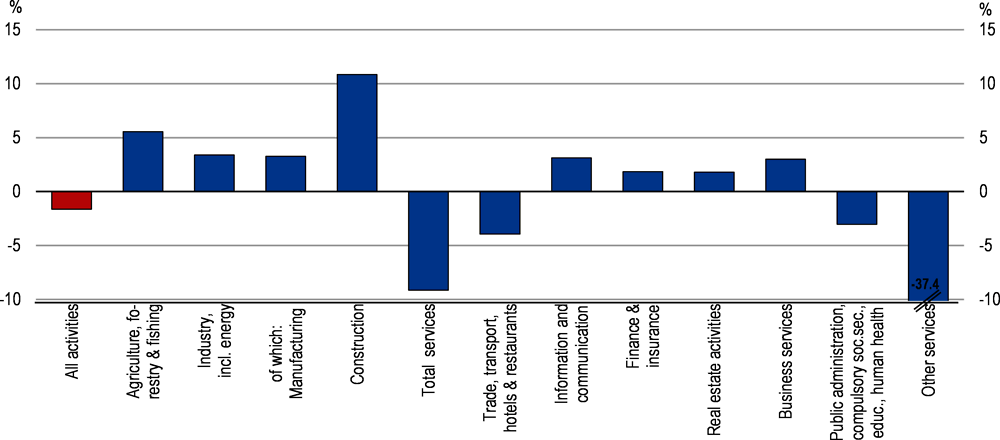

The consequences of the crisis varied considerably across the economy, with some industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, construction and information and communication expanding production (Figure 1.5). Materials shortages were constraining production in about 35% of industrial companies as of mid-2021, although differences in specialisation have meant this problem has not been as severe as in neighbouring countries. Public sector employment expanded, particularly in the health sector as testing and vaccination capacity ramped up. Conversely, industries requiring face-to-face contact were particularly badly hit, such as trade, transport, hotels and restaurants as well as cultural services.

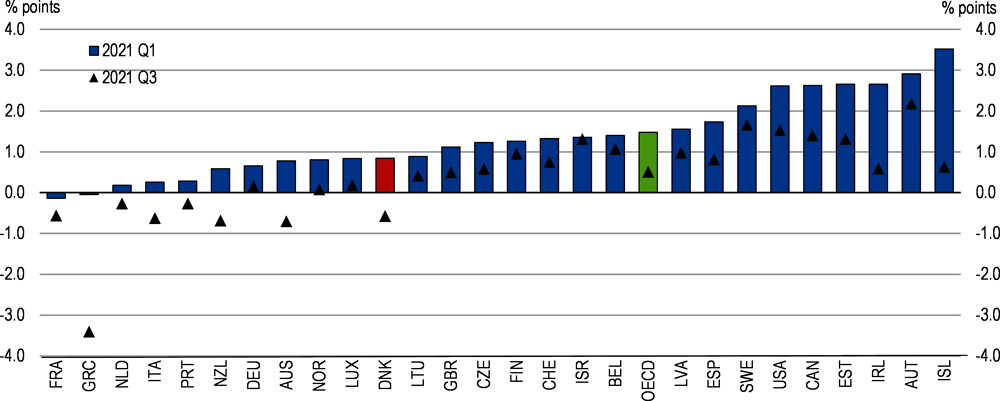

The COVID-19 crisis disrupted an almost decade-long strengthening of the labour market, although the increase in unemployment was smaller than in most OECD countries (Figure 1.6). The small effect on aggregate unemployment reflects the success of the government-supported wage compensation (or job retention) scheme in preventing job separations, as well as rapid recovery once the virus situation improved. Around 250 000 employees (9% of all employees) were on wage compensation in spring 2020 and early estimates indicate that government policy support saved 81,000 jobs (Bennedsen, Birthe Larsen and Scur, 2020[4]). Sectors badly affected by the crisis, such as hospitality, culture, leisure and retail were over-represented in the take-up of wage compensation (Andersen, Svarer and Schrøder, 2020[5]). When the scheme ended temporarily in August 2020, over 90% of those who had been on wage compensation were back in employment by October (Danish Economic Councils, 2021[2]). The take up of wage compensation was lower during the second wave, peaking at 100 000 in January 2021.

The labour market recovered rapidly from spring 2021, with declining unemployment, a high number of job postings and increasing labour shortages across much of the economy. Shortages can be expected to ease as the immediate rebound ends, the job matching process has time to operate, increases in the retirement age boost participation, and excess labour in the health sector is released. At the same time, decreasing spare capacity will put upward pressure on wages through 2022. Wage pressures remain contained overall (+2.6% in the year to the second quarter of 2021, or +3.1% in the private sector), but are higher in some industries, notably construction, real estate, and information and communication.

By avoiding a larger labour market disruption, the wage compensation scheme has reduced the magnitude of any “scarring” effects on long-term labour market outcomes due to the crisis. Long-term unemployment, which increases the risk of scarring and entrenched labour market disadvantage, rose during the crisis but remains lower than following the Global Financial Crisis (Danish Economic Councils, 2021[2]). Long-term unemployment comprises a relatively small share of total unemployment in comparison with other OECD countries. The downside of a wage compensation scheme is the risk of impeding reallocation in response to structural adjustments, which would normally be facilitated by the flexibility, low level of employment protection and high active labour market program spending inherent in Denmark’s “flexicurity” model (Box 1.2). The phase-out of the wage compensation scheme in June 2021 reduces this risk, as does the temporary nature of the COVID crisis. However, there is some evidence that the COVID shock may have accelerated labour reallocation already underway in the Danish economy, with relatively low-skilled occupational groups that were already in decline prior to the crisis most likely to see high take-up of wage compensation (Mattana, Smeets and Warzynski, 2020[6]).

The Danish flexicurity model is characterised by three core elements: flexible rules for hiring and dismissals, generous replacement rates of unemployment insurance benefits, and substantial active labour market policies. Furthermore, the labour market is largely organised by social partners, through broad based collective agreements. Two thirds of Danish workers are union members and labour issues such as minimum wages, working hours and holidays are mainly covered by collective agreements rather than Danish law.

The flexicurity model in its current form was largely developed through the 1990s. A substantial decrease in the duration of unemployment benefits and a much stronger emphasis on active labour market policies was implemented to promote return to work through upskilling and to ensure that the unemployed are available to the labour market. Together with a prolonged economic boom, these adjustments are seen as a major driver of the decrease in structural and actual unemployment since the mid-1990s (Unemployment Benefit Commission, 2015[7]).

The main advantage of flexicurity is that it limits the financial risk to both employers and employees. The high degree of flexibility allows companies to make quick adjustments to their work force in the different phases of the business cycle, reducing the risk associated with hiring new staff. At the same time, the high unemployment replacement rate limits the risk for employees when taking up a new job, and allows for consumption smoothing in case of joblessness. The model delivers a high rate of job turnover and low skills mismatches compared with other OECD countries. During the global financial crisis, a sustained increase in structural unemployment was avoided as the flexicurity system enabled a large proportion of the jobless to find employment relatively quickly (Eriksson, 2012[8]).

The Danish flexicurity system is nevertheless expensive, due to the high replacement rate of unemployment benefits and the highest spending on active labour market policies in the OECD.

Source: OECD (2016), OECD Economic Surveys: Denmark, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark (2021), The Danish Labour Market.

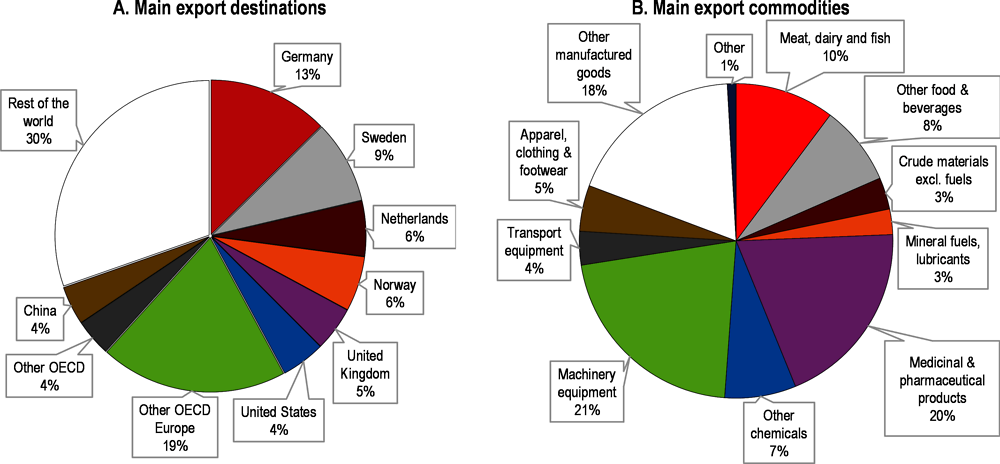

Danish trade is diversified in terms of destinations and commodities (Figure 1.7). Products that are less sensitive to fluctuations in foreign activity, such as agriculture, pharmaceuticals and green technologies, underpinned an increase in Danish export market share during 2020, even as exports declined overall due to the collapse of foreign demand. Uncertainty around the exit of the United Kingdom from the EU was significantly reduced by the finalisation of a trade agreement, avoiding a worst case scenario that could have seen Danish exports to the UK fall by 17% (Smith, Hermansen and Malthe-Thagaard, 2019[9]).

Exports of services fell more than goods during the crisis, in part due to the collapse in international tourism. Shipping is Denmark’s biggest service export and the value of sea transport exports declined but then recovered (in part driven by price increases from global supply constraints), whereas exports of travel, construction and business services have been recovering more slowly (Statistics Denmark, 2021[10]). As for neighbouring countries, Denmark was a net importer of travel services prior to the crisis, as Danes spent more on travel abroad than international visitors spent in Denmark (OECD, 2020[11]). During the crisis, exports of travel services declined to a similar extent as imports, with little change in the overall balance.

Denmark’s large current account surplus fell slightly to 8.2% of GDP in 2020 as exports contracted by more than imports. The current account surplus reflects the gap between (particularly) high saving and low domestic investment, as strong returns on international investment combine with a trade surplus, and is assessed by the IMF (2021[12]) to be stronger than implied by medium-term fundamentals and desirable policies. The strong peg of the Danish Krone to the Euro may also contribute to the current account surplus if it contributes to undervaluation of the currency, though evidence on valuation relative to fundamentals is mixed (IMF, 2021[12]). The external imbalance acts as a drain on demand elsewhere in the European Union but also provides a source of financing for investment in other countries. Denmark had a current account deficit as recently as 1998, building up a substantial surplus since then as a consequence of tax revenue from North Sea oil production, tax reforms that have reduced interest rate deductability and pension reforms. The pension system has been gradually shifting from a pay-as-you-go system to a generous fully funded system, which is associated with an increase in national saving and therefore an increasing current account balance (Koomen and Wicht, 2021[13]).

The demographic shift to a higher share of older people with a low propensity to save is set to reduce the current account via the saving rate, but this effect is likely to be small (Leszczuk and Pojar, 2016[14]). A sustainable increase in public and private investment would bring the current account closer to balance and several recommendations in this Survey push in this direction, including shifting towards less distortionary taxation that creates less disincentives to investment, providing more support to green investment and R&D, and relaxing the medium-term deficit limit in the Budget Law. Conversely, recommendations to tighten macroprudential policy and mortgage interest deductions could increase already high saving rates.

Consumer price inflation picked up to 3% in October 2021, following weak price growth in 2020. The pickup reflects a recovery in commodity prices and supply constraints (particularly affecting container shipping) as economies reopen globally. A gradual acceleration in wage growth, notably in construction where annual wage growth approached 4% in mid-2021, is set to underpin more durable price growth as the recovery of the economy sees spare capacity used up. Policy measures that support industries, such as construction, with little spare capacity should be better targeted, for example by reforming the housing-job scheme (BoligJobordningen) to better support cost-effective energy savings (Chapter 3).

GDP is forecast to grow by 2.4% in 2022 and 1.7% in 2023 (Table 1.1 above). A contraction in the first quarter of 2021 gave way to strong growth as vaccination enabled a gradual relaxation of containment measures, with economic activity further supported by the global recovery. The recovery is now well established, with output and labour market indicators consistent in showing that little spare capacity remained in the second half of 2021.

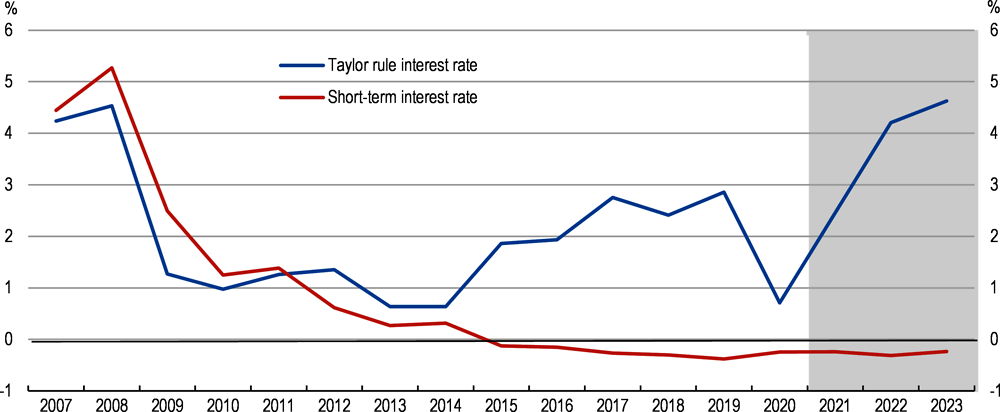

The divergence between economic conditions in Denmark and the Euro Area is likely to see expansionary ECB monetary policy becoming less well-suited to Denmark. Denmark has maintained a fixed currency peg for almost 40 years, which has reduced uncertainty from exchange rate volatility and enjoys broad political support. The peg to the euro means that Denmark’s monetary policy is de facto set by the ECB, with negative real interest rates contributing to credit growth. As the recovery in Denmark picks up speed, the level of interest rates will be lower than indicated by the level of inflation and extent of spare capacity (Figure 1.8). Fiscal and/or macroprudential policy may need to be tighter to prevent overheating, though inflation is still projected to remain contained in the near term.

The volatility of economic activity during 2020 and early 2021 points to substantial risks around the forecast. Slower progress in bringing the pandemic under control globally is the key downside risk, with potential under a worst case scenario for further substantial outbreaks (Table 1.2). Like other OECD countries, Denmark should re-orient its development assistance to contribute further to global efforts to reduce the risk of new strains and protect people in less developed countries, including by expanding its pledge to provide 1 million vaccine doses and USD 16 million to the COVAX initiative. A larger-than-expected increase in insolvencies as exceptional fiscal support is removed (see below) would slow jobs growth and put pressure on banks’ balance sheets, potentially combining with low bank profitability to constrain the availability of finance for new activity. On the upside, household spending of excess saving during the crisis would boost private expenditure and profits, with potential for positive feedback loops via faster wage growth as labour shortages intensify. Risks of overheating and accelerating price growth have increased with the fast pace of the recovery in 2021. A globally synchronised recovery could further boost demand for Danish exports and in particular Denmark could benefit from an upturn in demand for renewable energy technologies if green recovery packages become more extensive.

House prices have risen rapidly

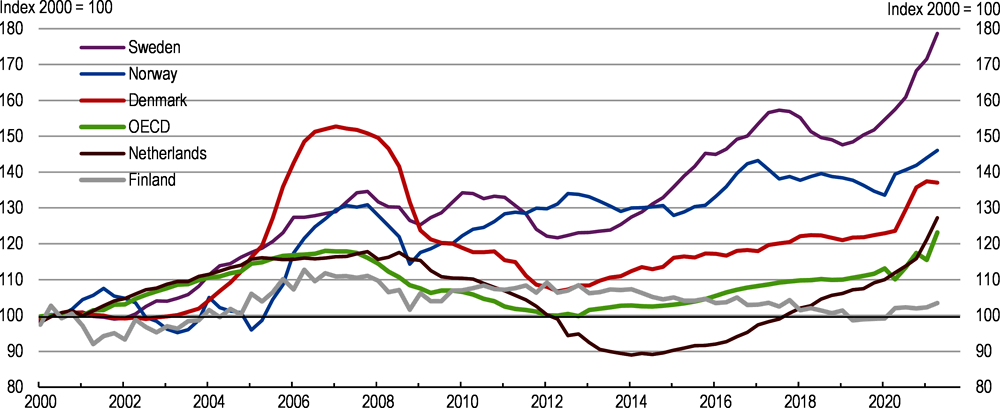

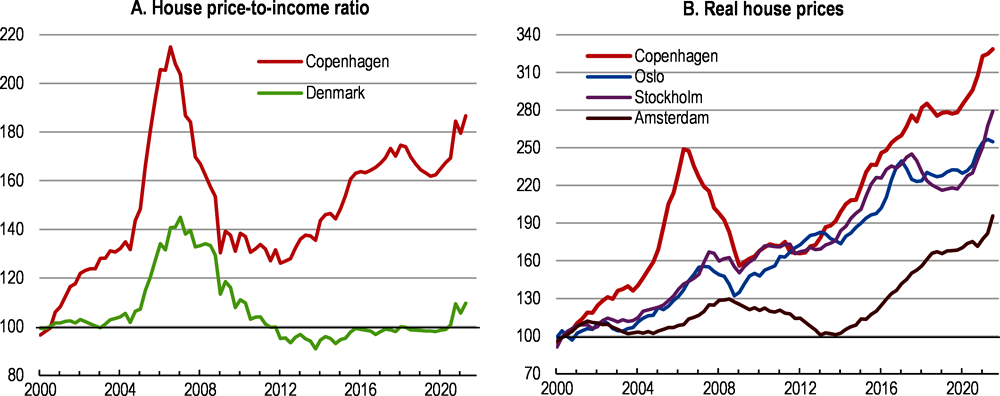

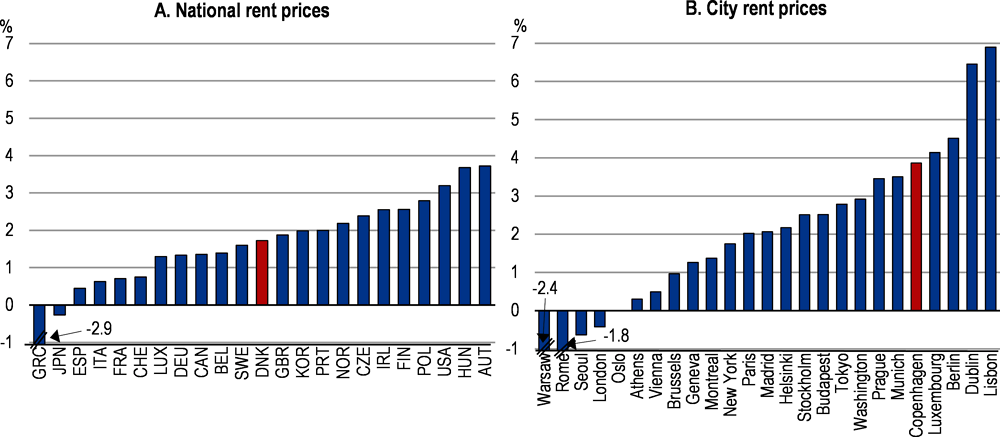

As in many other countries house price growth stepped up during the crisis (Figure 1.9), as low interest rates, household income growth and forced saving increased the flow of money into housing despite the economic contraction. Price growth was particularly marked in Copenhagen (Figure 1.10), while demand and prices for rural summer houses also spiked, though both account for only a small share of the national housing stock. Price growth has been partly credit-fuelled, as outstanding mortgages expanded by 3.4% in the year to March 2021. Rental prices have also risen. Since 2010, nationwide rents have increased by just more than average per capita incomes. The rate of increase has been much faster in Copenhagen (Figure 1.11), with estimated average rent levels for flats in Copenhagen the second highest in major EU cities in 2020 (Eurostat and iSRP, 2021[17]).

House price and rental growth in excess of incomes exacerbates affordability problems and increases inequality. The distribution of housing assets and expenses makes a relatively large contribution to inequality of income (after housing expenditure) compared with other EU countries (ElFayoumi et al., 2021[18]). Challenges are greatest for the young and low-income households, whose labour market outcomes were worst affected by the COVID crisis. Households on average spend 23% of their gross adjusted disposable income on housing, including utilities and repairs, which is among the highest in OECD countries (OECD, 2020[19]). More than 80% of private renters in the bottom quintile of the income distribution spend over 40% of their disposable income on total housing costs. This partly reflects a high share of students living apart from their parents due to generous support for students, as well as high utility costs due to energy taxation (Chapter 2) – the housing cost overburden rate for low income earners falls around the middle of OECD countries when only taking rent expenses into account (OECD, 2021[20]).

Denmark’s large social housing sector plays an important role in making housing affordable for those at the bottom of the income distribution, but these benefits should be enhanced through better targeting while monitoring any negative effects from reduced social mixing. Social rental housing accounts for of 21% of dwellings, the third highest share in the OECD behind the Netherlands and Austria (OECD, 2021[20]). Social housing is referred to as general housing, reflecting its aim to house a broad range of the population. All households are eligible for waiting lists, with wait timesreaching several decades for the most popular estates (Phillips, 2020[21]). There are no income thresholds, although priority can be given to those in acute need. The quality, size, age and location of social housing typically nonetheless mean that tenants predominantly have low incomes, with 80% of tenants in the bottom half of the income distribution (Folketinget, 2016[22]). The lack of means testing is similar to municipal housing in Sweden or the universal model traditionally in place in the Netherlands and Austria, albeit some targeting has been implemented in these two countries to exclude approximately the top half and top 20% of income earners respectively (OECD, 2020[23]).

Another important factor in improving housing affordability is removing impediments to the delivery of more supply in response to higher prices, particularly in Copenhagen. The supply elasticity is estimated to be at the upper end among OECD countries (Cavalleri, Cournède and Özsöğüt, 2019[24]) and unlike in many OECD countries residential construction expanded during the crisis, supported by energy renovations of social housing. However, strict rent regulation impedes growth of the private rental market and spatial mobility. There are four different rent regulation systems, with non-rent-regulated letting of buildings built since 1991. The coexistence of controlled and flexible rent sectors has been shown to increase spatial misallocation (Chapelle, Wasmer and Bono, 2019[25]; Skak and Bloze, 2013[26]). Reducing the strictness of rent regulation is unlikely to lead to a large increase in inequality: while recent analysis is lacking, historical data indicate that, among renters, the biggest beneficiaries among renters from regulated rent have been high-income households (Svarer, Rosholm and Munch, 2005[27]); and in the long term lower house prices imply lower rent levels, even if rents may rise temporarily after controls are eased (Cournède, Ziemann and De Pace, 2020[28]). More stringent rental market regulations are also associated with severe downturns that are more likely and more protracted, which may be related to bottlenecks in housing supply and lower labour mobility (Cournède, Sakha and Ziemann, 2019[29]).

Asset price growth is increasing financial stability risks

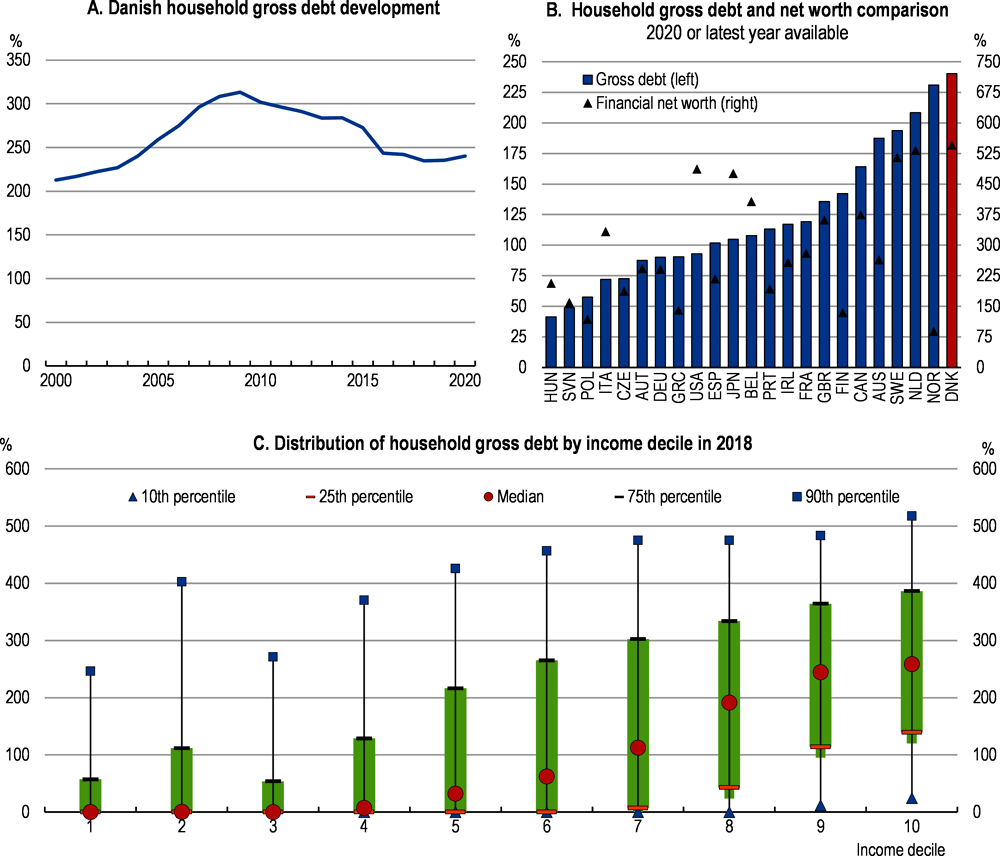

Strong asset price growth during the downturn raises the prospect of credit risks reaching high levels as the economy recovers. The primary source of financial stability risk is the acceleration of house prices amid high household gross debt, though equity prices have also increased with the Danish C25 index reaching record highs in 2021. Household debt is high by international comparison, though risks are reduced by the distribution of that debt, with most held by high income earners and substantial asset holdings (Figure 1.12). However, even without directly adverse effects on the financial system, high levels of debt amplify macroeconomic volatility (Sutherland and Hoeller, 2012[30]).

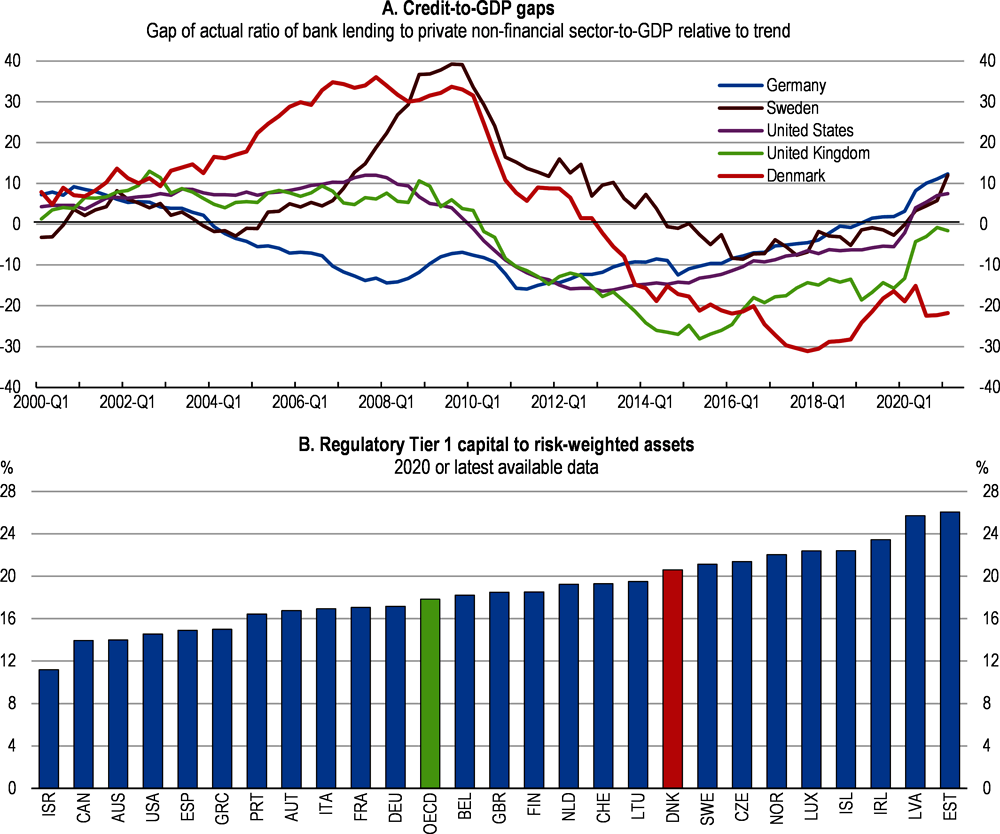

Credit growth has outpaced GDP since the start of 2018 and continued to do so during the crisis. The credit-to-GDP ratio offers no evidence of excess credit growth as it remains below its long-term trend (Figure 1.13, Panel A), although in level terms the credit-to GDP ratio at the end of 2020 was still among the half dozen highest for OECD countries where data are available (BIS, 2021[31]). Credit standards have been largely unchanged in 2020 and early 2021, although there are some signs of increased risk-taking, with loans to highly indebted home buyers representing an increasing share of new lending, especially in Copenhagen (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2021[32]). Banks are liquid and well capitalised (Figure 1.13, Panel B), though profitability has fallen under the low interest environment since 2017. Loan impairment changes increased in 2020, but are expected to decline in 2021 (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2021[32]). Danmarks Nationalbank’s (2020[33]) stress test shows that a few systemic institutions breach the requirements for their capital buffers in the most severe recession scenario. Mortgage credit institutions, which are responsible for the bulk of mortgage lending and fund this lending through issuing bonds, are strongly dependent on the health of the housing sector and highly interconnected with pension and insurance companies (IMF, 2021[12]). As recommended in the 2019 Economic Survey, Denmark should improve prudential regulation and enable cross-border banking by joining the European Banking Union (Table 1.3).

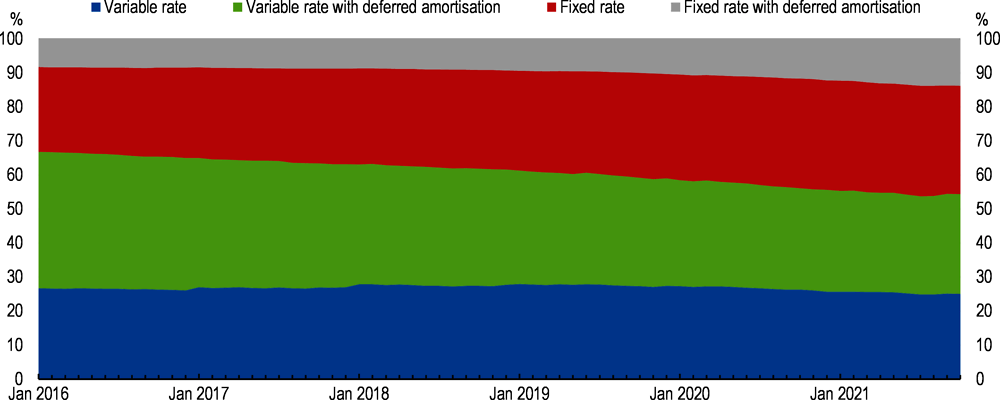

Exposure of households to interest rate increases is heightened because around half of mortgage loans are at variable interest rates and just under half of mortgage debt is on deferred amortisation (interest-only) terms (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2021[34]). However, the composition of mortgage lending to households has recently shifted towards fixed interest rate loans (Figure 1.14), in part due to guidelines introduced between 2016 and 2018 that restrict the capacity of highly indebted households to take out variable interest rate loans without amortisation. The share of mortgage loans with deferred amortisation has increased since late 2020, and such loans are most widespread in the major cities of Copenhagen and Aarhus.

Denmark should be ready to further tighten macroprudential regulation, in order to stem risks from the combination of high asset prices, highly indebted households and “low for long” interest rates that are not calibrated to Danish economic conditions (Figure 1.8 above). A tighter macroprudential stance is generally linked to a lower likelihood of economic crises (Cournède, Sakha and Ziemann, 2019[29]) and restrictions on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios are effective at curbing credit growth (Cerutti, Claessens and Laeven, 2017[35]; Carreras, Davis and Piggott, 2018[36]). However, distributional effects also need to be taken into account as tighter restrictions can prevent house purchases for people with low incomes and wealth. Consideration should be given to tightening loan-to-value restrictions, which are most effective preceding or during the build-up of risks (OECD, 2021[37]), particularly as the Danish requirement of a 5% down payment is low relative to the other Nordic countries and the vast majority of first-time buyers borrow right up to the threshold. Work should begin to implement the possibility of restrictions on debt-to-income (or as applied more commonly, on debt servicing) to complement loan-to-value caps by ensuring households have sufficient income to service their debt as valuations soar. Households with high debt-to-income ratios are restricted from loans with variable interest rates and deferred amortisation (Table 1.3), which reduces interest rate sensitivity. The government has not taken up the Systemic Risk Council’s recommedation in June 2021 to limit access to interest-only loans for borrowers with a loan-to-value ratio above 60%, but has acted on its recommendation to raise the countercyclical buffer to 1% from 30 September 2022.

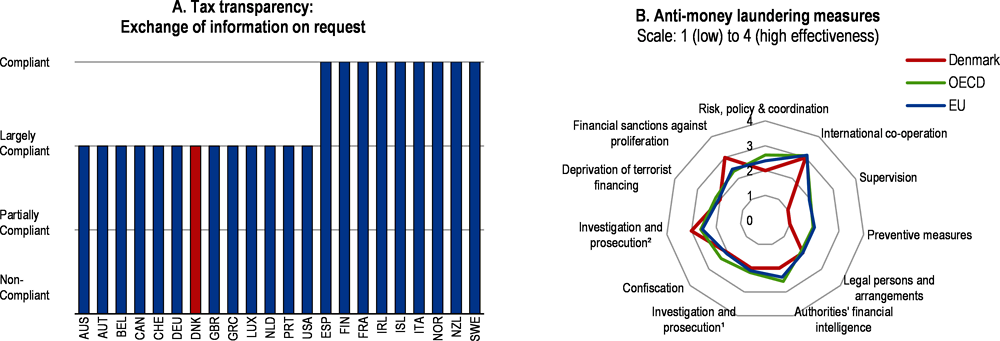

Improvements to preventive measures and supervision under Denmark’s anti-money laundering framework need to continue. Denmark has tightened its anti-money laundering framework since large-scale money laundering was disclosed in the Estonian branch of Denmark’s largest bank in 2018. While reforms have continued since the last Financial Action Task Force assessment (Figure 1.15), there is still scope to further intensify penalties for non-compliance and scrutiny, for example through more on-site inspection of higher-risk financial institutions and application of technological innovations (IMF, 2021[12]).

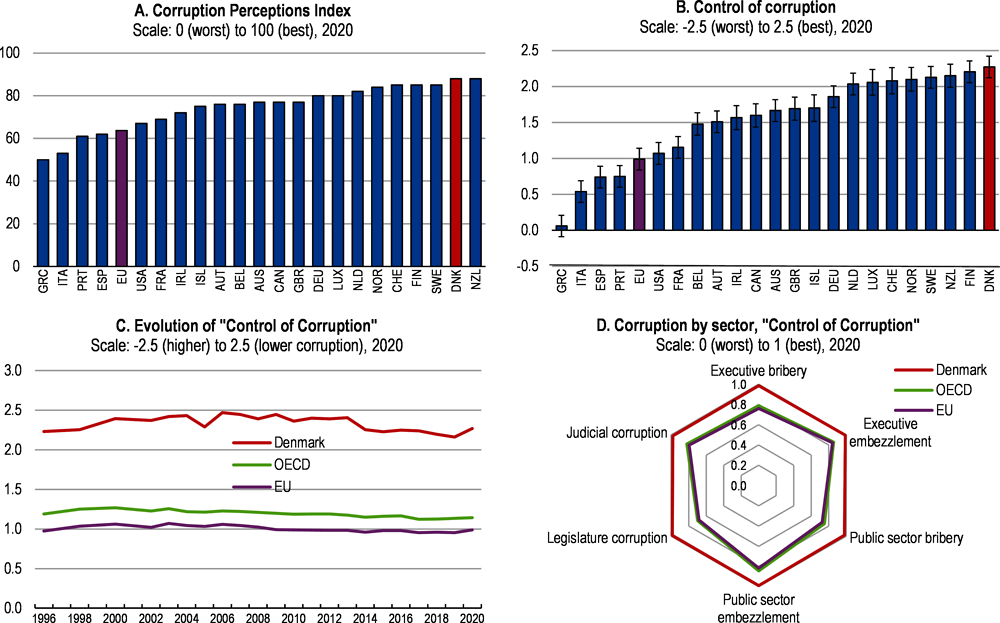

Control of corruption is perceived to be among the best in the OECD across a broad range of indices (Figure 1.16). There is room for improvement on foreign bribery, where there has been a failure to thoroughly investigate foreign bribery allegations involving major Danish companies, with sanctions rarely imposed (OECD, 2015[38]). Legal changes are still needed to reduce the difficulty of imposing corporate liability for the actions of employees and more tightly define the defence for small “facilitation payments”.

Government spending supported the economy during the crisis

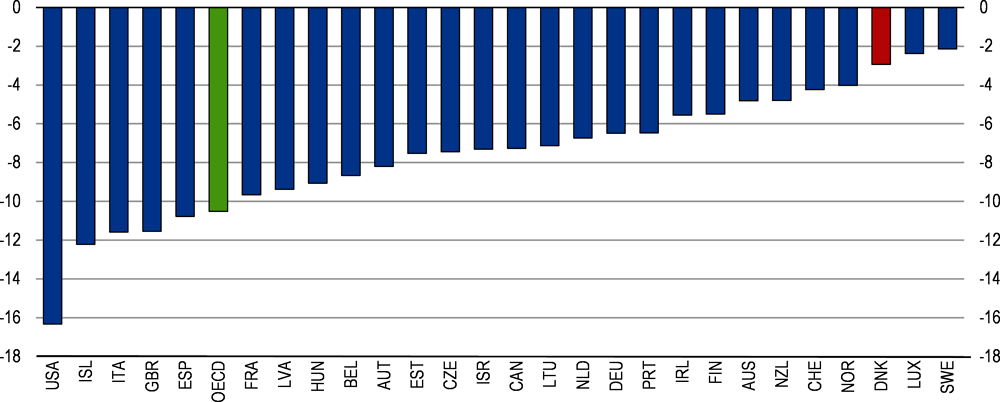

Significant fiscal support during the COVID crisis (Box 1.1 above) prevented a wave of insolvencies or a big decline in employment, yet the structural balance remained in surplus in 2020. This reflected a strong budget position entering the crisis along with under-spending relative to government plans, which contributed to a deterioration in the budget balance that was smaller than most OECD countries (Figure 1.17). Strong revenue collection was partly due to taxation of holiday pay disbursements and the tax on pension yields, which depends on highly variable investment returns and reached 2.1% of GDP in 2020, substantially above the average of 1.3% of GDP over the past two decades. Despite strong automatic stabilisers – the budget balance semi-elasticity is the largest in the OECD, along with Belgium and Sweden (Price, Dang and Botev, 2015[39]) – Denmark in 2020 had the smallest general government deficit as a share of GDP in the OECD. Almost all of the 2% of GDP in discretionary fiscal easing in 2020 was due to one-off COVID-related measures.

A larger budget deficit in 2021 reflects substantial temporary factors. Temporary spending due to COVID-19 is estimated by the Ministry of Finance (2021) at 1.5% of GDP, just below the 2020 level. A further 0.7% of GDP relates to one-off support to compensate the mink industry for culling, while revenue from the pension yield tax is expected to be lower than in 2020. Several initiatives boosted public investment in 2021 and will see it remain at an elevated level thereafter, including the Green Recovery Package, Digitisation Fund and EU Recovery and Resilience Facility. Unlike many recovery packages in other OECD countries, Denmark has not implemented any measures likely to worsen environmental outcomes (OECD, 2021[40]), and at around 60% the share of recovery spending directed towards environmental goals is high by international comparison (O’Callaghan,, Yau and Murdock, 2021[41]; European Commission, 2021[42]).

The Danish government should continue to remove exceptional COVID-related support where economic activity has recovered. This entails first making support more targeted. For example, the government-appointed Economic Expert Group (2021[43]) has recommended targeting to firms still affected by a significant decrease in turnover. The recovery is well underway, with the output gap closed and unemployment below its pre-crisis low as of the third quarter of 2021. There is evidence of capacity pressures in some sectors, notably in construction where there are increasing reports of skill shortages. Ending temporary COVID-19 spending (including one-off mink industry compensation) will be sufficient to return to close to structural balance in 2022, consistent with the government’s strategy to rapidly deploy substantial support and then withdraw support quickly once it is no longer necessary. The government’s budget proposal for 2022 would see the structural deficit reduced to 0.2% of GDP, including DKK 4 billion (0.17% of GDP) reserved for additional COVID-related measures. The government needs to be ready to restore substantial stimulus should the health situation deteriorate, which could threaten domestic and external demand.

Sustainable public finances over the long term

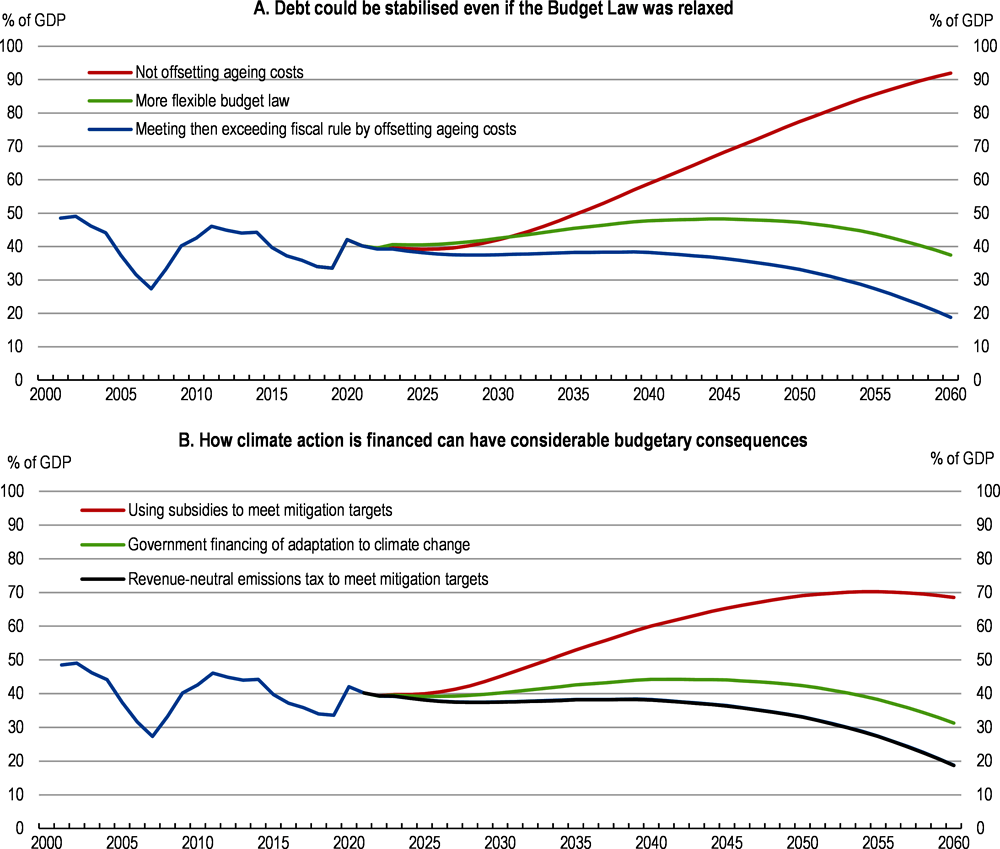

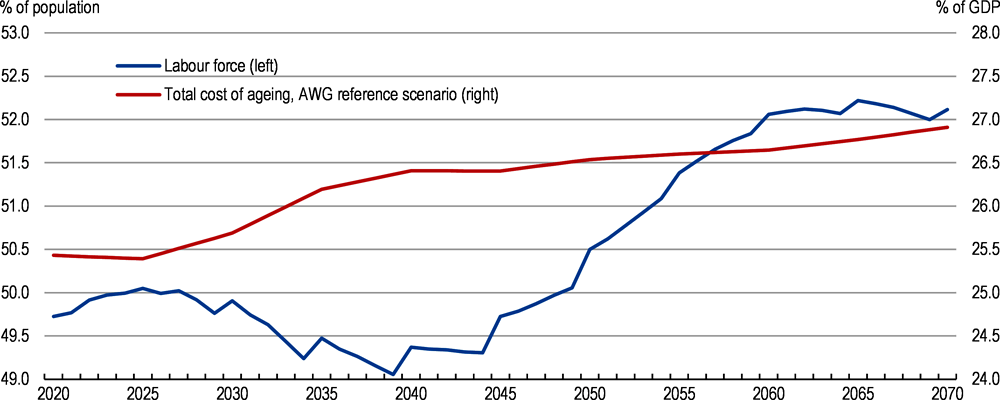

Based on current settings, Danish fiscal policy is sustainable (Figure 1.18, Panel A). The re-imposition of the Budget Law structural deficit limit of 0.5% of GDP from 2022 will see public debt declining again as a share of GDP. The decline is set to accelerate after 2040, as strong indexation of retirement ages to increases in life expectancy combine with a relaxation of demographic headwinds following the retirement of the large baby boom generation (Figure 1.19). As set out in the 2019 Survey, long-term sustainability is contingent on the continued implementation of retirement age increases as life expectancy grows, under which the statutory retirement age is projected to reach 70 years in 2040 and 73 years in 2060. For someone starting work in 2018, Denmark is projected to have the highest retirement age in the OECD when they retire, which contributes to the affordability of high pension replacement rates (in excess of 100% for low-income earners) (OECD, 2019[44]). Already in 2016, 18% of males from the lowest socioeconomic quintile were not expected to survive from 50 to retirement age, compared with 4% of high socioeconomic females (Alvarez, Kallestrup-Lamb and Kjærgaard, 2021[45]). Under strong indexation, the effect of increasing retirement ages on lower socioeconomic groups needs to be monitored to ensure that disadvantaged older workers have sufficient access to lifelong learning, job opportunities and flexible work arrangements, with adequate safety net provisions such as disability benefits as a fall-back.

As a small open economy with its own currency and strong automatic stabilisers, Denmark needs to remain fiscally cautious. The Budget Law provided a strong starting point entering the crisis and has helped to reduce overspending by municipalities. That said, the temporary nature of adjusting to the retirement of a single large generation argues against overly restrictive policy settings in the medium term, as debt financing of the transition period would not put long-term sustainability at risk. There is also a need for substantial public investment in research and development as well as infrastructure to underpin the energy transition (Chapters 2 and 3), some of which should be debt funded to align the recovery of costs with benefits accruing well into the future. Finally, under low real interest rates, debt declines more quickly for a given primary balance and the costs of debt are lower (Blanchard, 2019). Current and expected interest rates are considerably lower than when the Budget Law was agreed in 2012, strengthening the budget balance, though this could change if high debt and rising inflation globally triggered an increase in interest rates. A review of the Budget Law after five years was planned as part of its introduction and is currently ongoing. Periodic evaluation and review can be valuable to update fiscal rules to changing circumstances, as in Sweden where the fiscal policy framework is re-evaluated every eight years.

Relaxing the structural deficit limit under the Budget Law to around 1% of GDP would provide space to address longer-term challenges from demographic headwinds (particularly between 2025 and 2040) and investment needs, without threatening fiscal sustainability or the capacity for active fiscal policy. Independent Danish institutions including the Central Bank and Economic Councils support such a move, which would keep the Budget Law in line with the EU Fiscal Compact structural limit of 1% of GDP for countries with a debt-to-GDP ratio well below 60%. There would also be benefits from increasing budget flexibility for municipalities. In particular, allowing a surplus from one year to be carried over would provide flexibility to react to the specific timing of local issues.

The budgetary ramifications of climate change depend critically on policy choices (Figure 1.18 above, Panel B). A revenue-neutral carbon tax is estimated to have only a very small effect on debt dynamics via slightly lower GDP growth, which is due to the increased cost of producing greenhouse-gas intensive goods in Denmark. Revenue neutrality is feasible by using additional revenue to address distributional and leakage concerns (Chapter 2), and desirable as the tax base will be eroded by the long-term shift to net zero emissions. By contrast, relying heavily on subsidies could have a negative and enduring effect on public finances. Public funding of adaptation costs would worsen the budgetary position, but, on its own, would be unlikely to disrupt the declining trend in debt as a share of GDP. Municipalities have concerns around their capacity to deal with climate adaptation such as flood protection, where the costs could be too big for a single municipality to handle. A clear framework should be developed setting out where private, local or central authorities are responsible for the costs of adaptation, taking into account the limited fiscal capacity of municipalities. Integrating environmental risk into longer-term fiscal assessments, as in the UK and Germany, would help Denmark to identify and, if possible, quantify potential risks as well as opportunities for budget planning by the public sector (OECD, 2020[53]).

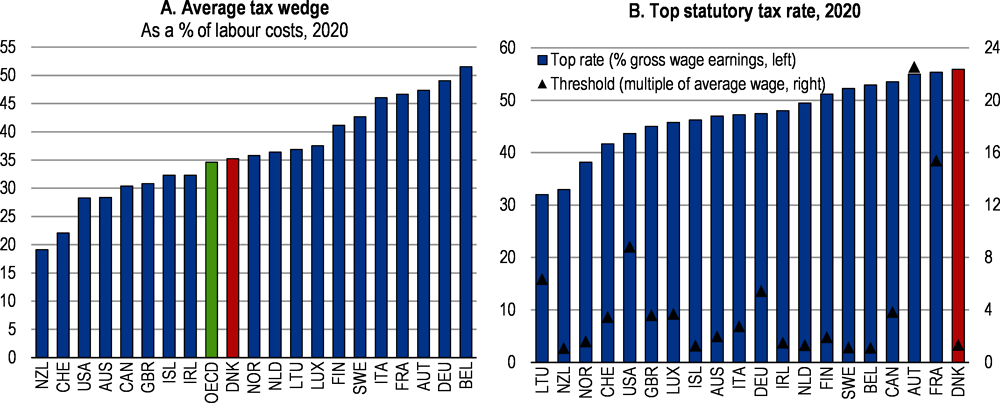

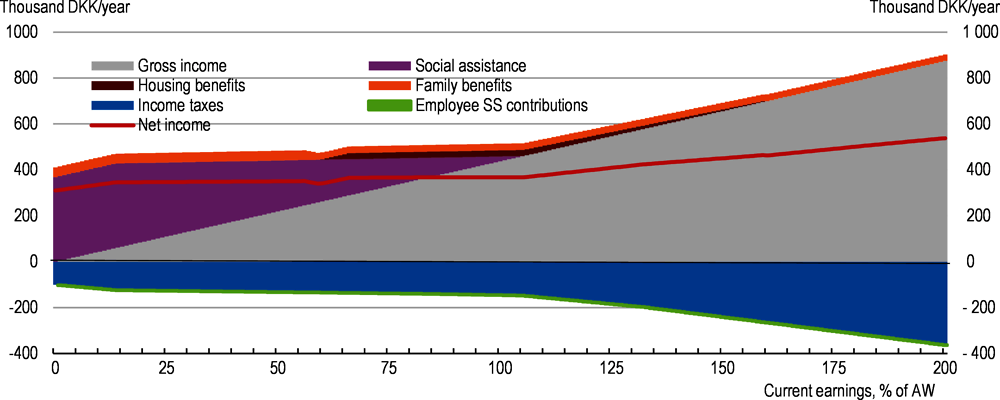

The Danish tax system is overall well-designed and efficient, with limited use of tax expenditures and a total tax wedge around the OECD average (Figure 1.20, Panel A). Marginal tax rates are below the OECD average for low- and middle-income earners, but well above for high income earners due to the 55.9% top marginal tax rate (Figure 1.20, Panel B). Such high tax rates reduce the incentive to increase earnings through more working hours or further education. When benefits are also taken into account, marginal effective tax rates are high, at close to 100% between two-thirds of the average wage and the average wage for a couple with two children as social assistance payments are phased out (Figure 1.21). Tax rates are also high on capital income, blunting incentives for entrepreneurship, investment and job creation.

Top marginal tax rates should be reduced as recommended in past surveys (Table 1.4), but consideration should also be given to reducing high effective marginal tax rates faced by middle income families receiving social benefits. Further in-work tax benefits could be used to reduce marginal tax rates as benefits are withdrawn, though payoffs are smaller when the distribution of earnings is narrow, as in Denmark, or where tax rates or benefits are high (Immervoll and Pearson, 2009[54]).

To offset the negative revenue consequences of lower income taxation, planned updating of property valuations in 2024 should occur as soon as possible, in conjunction with a reduction of mortgage interest deductibility. Reducing mortgage tax deductibility, as recommended in previous surveys, would reduce incentives for high household leverage, easing housing demand and contributing to smoother housing cycles (Cournède, Sakha and Ziemann, 2019[29]). Taxation of housing (especially owner-occupied housing) is presently low, both relative to other forms of saving and by international comparison (OECD, 2018[55]), so that increasing taxation of housing will improve the overall efficiency of the tax system. Environmental taxes should continue to increase, in particular through broad-based greenhouse gas emissions pricing (Chapter 2) and better aligning incentives for woody biomass use with its environmental impacts (Chapter 3). Overall the tax and other recommendations in this survey would have a small long-term negative budgetary impact (Table 1.5), which as discussed above could be accommodated without threatening fiscal sustainability. Increasing taxation of housing will offset some of the negative distributional effect of reducing income taxation, though some tradeoff between equity and efficiency of the tax system is likely to remain for substantive reductions (2 percentage points or more) in the top marginal tax rate.

Strong productivity is critical to underpin wellbeing as Denmark confronts structural challenges from the energy transition, digitalisation and an ageing population. Productivity is set to be the main driver of income growth as participation rates stabilise or fall, providing individuals with the option to work less or consume more and society with revenue to fund Denmark’s social welfare model. Policy settings that promote productivity are thus critical (Box 1.3), including via cost-effective climate policy (Chapter 2).

As in other countries, productivity growth has slowed in recent decades, though Denmark has maintained its relatively high level of labour productivity (Figure 1.1 above) due to a relatively strong productivity performance in the manufacturing industry over the past decade. Strong multifactor productivity growth in manufacturing has been partly driven by an increase in operations of Danish companies abroad, including an increase from 2% to 14% of manufacturing gross value added from exports of goods that do not cross the Danish border but rather are processed abroad. Manufacturing productivity would be around 14% lower if processing abroad was excluded, but as it is not possible to fully separate related income and expenses, productivity could also be a similar extent higher depending on how domestic labour is allocated to operations abroad (Danish National Productivity Board, 2020[57]). Meanwhile, as in other countries productivity growth has stagnated in services, particularly in less knowledge-intensive services including trade, transport, and food and accommodation. Firms at the bottom of the productivity distribution are falling behind and innovation is lacking altogether in services, as even the most productive firms have experienced persistently slow productivity growth (OECD, 2020[58]).

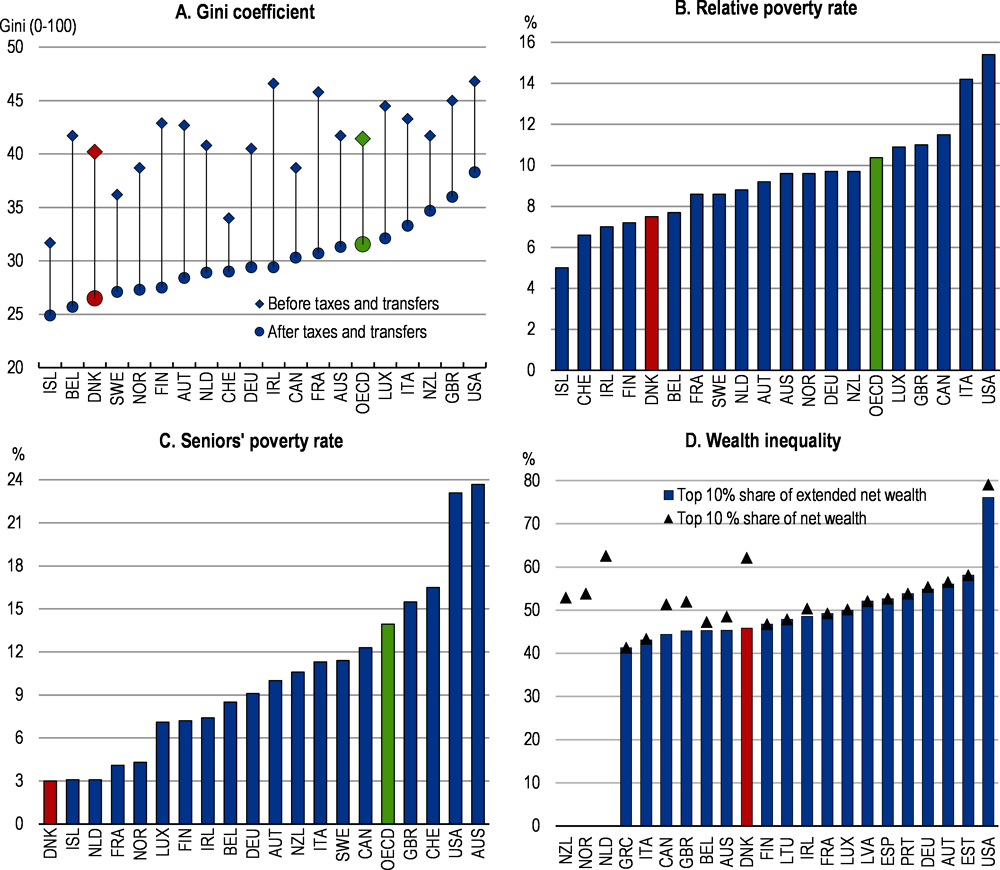

Denmark has among the lowest income inequality and relative poverty rates in the OECD (Figure 1.22, Panels A to C). The bigger hit to youth employment during the COVID crisis will exacerbate the trend over the past decade for relative poverty risks to increase for those aged under 40, while relative poverty rates have declined among those aged 65 and above (OECD, 2021[59]). The income hit to vulnerable groups and rapid asset price growth are also likely to have increased wealth inequality, which has been stable on a moderate level over the last two decades in advance of the crisis but higher if large employment-based pension assets are excluded (Figure 1.22, Panel D).

The estimated impact of some key structural reforms proposed in this Survey are calculated using historical relationships between reforms and growth in OECD countries (Table 1.6). As these simulations abstract from detail in the policy recommendations, are based on swift and full implementation of the proposed reforms and do not reflect Denmark’s particular institutional settings, the estimates should be seen as purely illustrative.

Enhancing the benefits of digital transformation (section 1.4.1) and strong female labour force participation, (section 1.4.2) while improving the integration of migrants (section 1.4.3), are key steps to broaden Denmark’s productivity success. The latter two groups are also important for inclusiveness, as is the indigenous population in Greenland (Box 1.4). Lack of competition has been identified as one factor in weak productivity growth in some domestic-focused sectors, so implementation of the European Competition Network directive is welcome (Table 1.7). Sound infrastructure governance, including good project selection and planning, is associated with a significant boost in productivity growth among firms in infrastructure industries and in industries that use infrastructure intensively (Demmou and Franco, 2020[61]). Denmark ranks highly for infrastructure governance, but is among the bottom third of countries for national infrastructure planning (Oprisor, Hammerschmid and Löffler, 2015[62]). Consideration should be given to introducing an independent infrastructure advisory body, as in the United Kingdom and Australia (ITF, 2017[63]), to help prioritise projects according to cost-benefit analysis. Danish municipalities often have difficulty planning key infrastructure projects as they have limited capacity, and lessons from one region have not been used to inform others (for example when building new hospitals simultaneously).

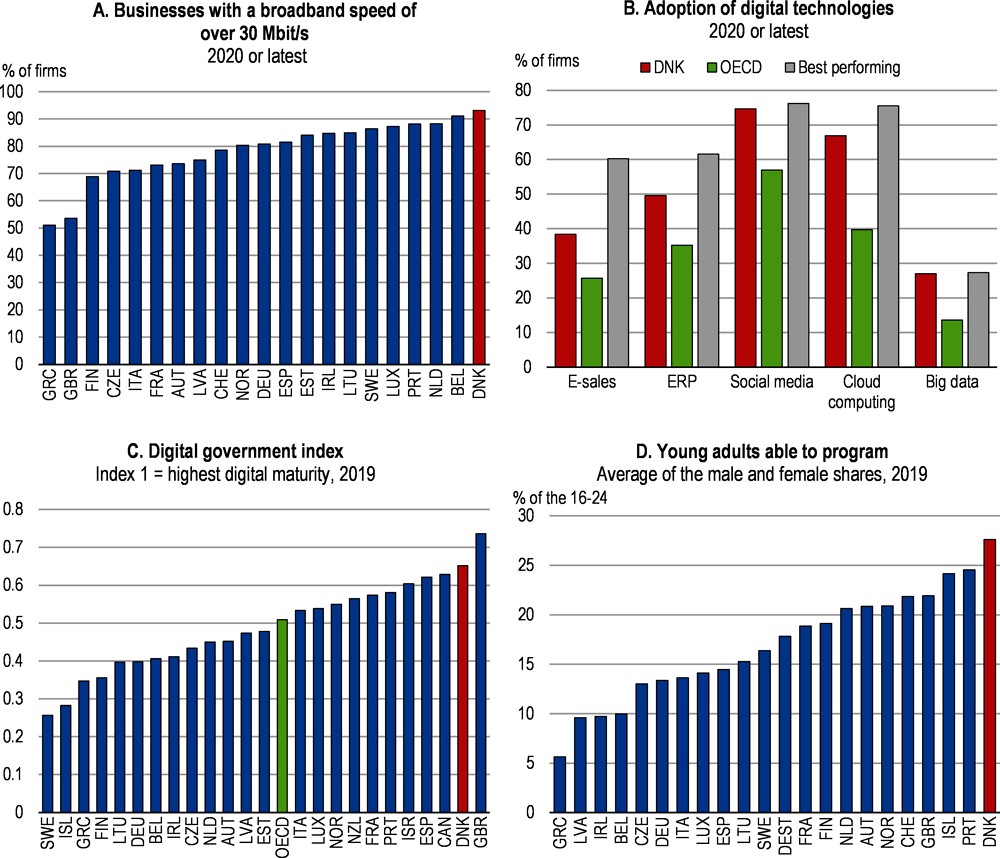

Supporting diffusion of the benefits from the digital transformation

Danish firms are well-placed to benefit from digital transformation (Figure 1.23). Broadband and mobile internet speeds are high and growth in internet bandwidth in 2020 was well above the OECD average (OECD, 2021[64]), which is even more impressive given the solid starting point. Among 27 EU and 18 non-EU countries, Denmark ranked behind only Finland on the European Commission’s (2021[65]) International Digital Economy and Society Index, which summarises indexes of digital performance and competitiveness. There is strong uptake of digital security measures (Eurostat, 2021[66]). Denmark also has a high share of STEM graduates (Eurostat, 2021[67]) and Danish adults are among the top-performers in problem solving in technology-rich environments (OECD, 2019[68]). A digital growth reform package was introduced in 2018 and a new digitalisation strategy will be launched in early 2022 on the basis of of the Digitization Partnership (2021[69]) recommendations released in October 2021.

Denmark performs less well on barriers to cross-border data flows (ECIPE, 2019[70]). There are legitimate reasons to protect data privacy and Denmark should continue to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation. However, there are also examples where decisions by the Danish data protection agency have curtailed the use of digital tools, notably cloud computing (ECIPE, 2019[70]). Less trade restrictive measures, such as rules on how rather than where data are stored, should be considered. Denmark should also promote international discussions with a view to finding greater interoperability with other countries’ approaches to cross-border data flows, including in the context of the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative on e-commerce.

Greenland is the world’s largest island and home to Denmark’s only recognised Indigenous group, the Inuit, who make up 85% of its population of just over 55 000. Greenland became a self-governing entity within the Kingdom of Denmark with the Home Rule Act of 1979 and autonomy in all areas except foreign and monetary affairs was reinforced with the 2009 Act of Self-Government. About half of the Greenland budget is financed by Denmark.

Socio-economic outcomes for the largely Inuit population of Greenland lag those for Denmark as a whole. Life expectancy is more than 10% lower in Greenland, which is similar to the gap for the indigenous population in Australia but larger than that for New Zealand, Canada, the United States and Mexico (OECD, 2019[71]). Relatively short life expectancy is primarily due to a high mortality rate from accidents and suicide. The life expectancy gap has changed little over the past two decades after rapid improvement between the late 1940s and early 1960s and more gradual convergence thereafter. Educational attainment is well below that in other Nordic countries, with about half of adults in Greenland aged 25-64 having no education beyond lower secondary school. Educational attainment is reflected in incomes, with average gross income for prime aged people with higher or general upper secondary education more than double that of those without upper secondary education, and overall average incomes consistently 30% lower than in Denmark over the past decade. Income inequality is high compared with the rest of Denmark. The unemployment rate halved between 2014 and 2019 to match that in Denmark as a whole at 5.1%. A lack of systematic data collection by indigenous status makes it difficult to make comparisons for the indigenous population specifically, including Inuit living elsewhere in Denmark.

Source: Statistics Greenland (various issues), Greenland in Figures; IWGIA (2021) The Indigenous World 2021: Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland); StatBank Greenland.

Weak business dynamism reduces the scope for entry of new firms to boost the diffusion of ICT tools and productivity, heightening the importance of quickly phasing out COVID support measures that favour pre-existing firms as the economy reopens. New business entries have failed to reach the 2007 peak and have been falling since 2015, both of which are worse than the average of 14 OECD countries for which comparable data are available (OECD, 2021[72]). Entry and job reallocation rates declined between 2000 and 2015, with the magnitude of decline falling around the middle of OECD countries (Calvino, Criscuolo and Verlhac, 2020[73]). This contributes to a relatively low share of start-up firms (OECD, 2021[74]). Denmark generally performs well on key policy factors for business dynamism such as regulatory burdens and red tape, judicial and bankruptcy efficiency, innovation, and skills. However, there is scope to improve access to finance: early stage companies find it difficult to raise equity finance and access to capital in the scale-up phase is limited (EC, 2019[75]). This is reflected in a low share of new business lending going to SMEs (OECD, 2020[76]) and one of the smallest markets for private equity growth capital in EU countries (Invest Europe, 2021[56]). A well-developed venture capital market (though much of this is invested abroad) and public-private equity financing via the Danish Growth Fund are positive features to build upon.

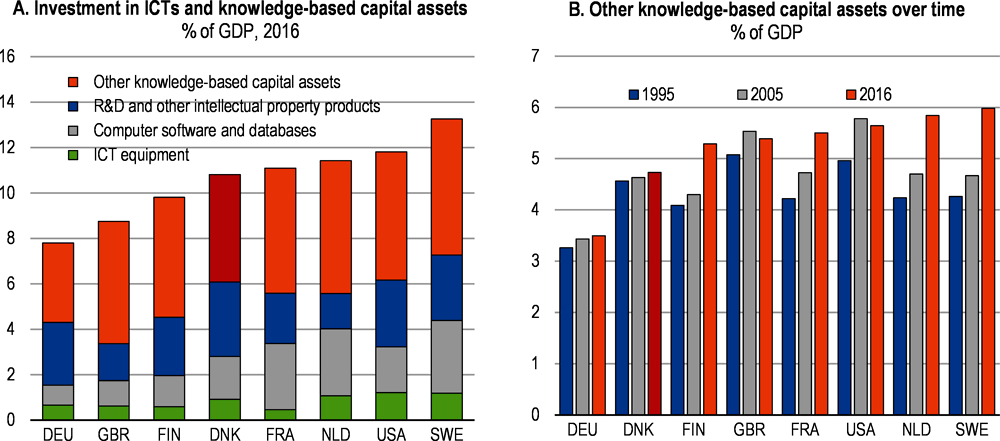

Investment in ICTs and knowledge-based capital is around average among peer countries, and intangible knowledge-based capital has not increased nearly as fast as in Finland, France, the Netherlands and Sweden (Figure 1.24). Intangible investment is typically riskier and harder to use as collateral, heightening the importance of making it easier for firms to raise equity finance. The 2019 Economic Survey recommended enabling pension funds to increase the share of investments in unlisted Danish equity (Table 1.7). Easing access to financing for young innovative firms and reducing barriers to digital trade each have the potential to increase firm productivity in Denmark by around half a per cent through increasing adoption of digital technologies (Sorbe et al., 2019[77]).

While Danes in general are highly educated and have strong technical skills, there is a relatively large share of young adults (17% in 2018) who do not finish high school or have a vocational qualification (OECD, 2020[19]). This is higher than the OECD median (13%) and well behind leading countries such as the United States, Canada, the Czech Republic and Korea with less than 10%. Around 38% of young adults who do not finish high school suffer from multiple or complex problems, while many others have been enrolled in further education without finishing it (MoF, 2020). These issues point to the importance of early intervention: Denmark already has among the highest rates of enrolment in Early Childhood Education and Care, but efforts are needed to make the teaching profession more attractive and strengthen the impact of professional development for educators (OECD, 2020[78]), including more formal ICT training. Tailoring such training towards engaging children most likely to drop out of school would deliver benefits through broadening the base of strong foundational skills needed to help people to adjust to new technology.

As in other OECD countries, teleworking became more prevalent during the COVID crisis. The Government should continue to take steps to maximise the potential productivity gains and reductions in commuting from more prevalent teleworking while managing the potential downsides. A high share of teleworking before the crisis reflected fast and reliable broadband coverage, high ICT skills as well as a high share of employment in knowledge and ICT-intensive services more amenable to remote work (Milasi, González-Vázquez and Fernández-Macías, 2021[79]). As high income workers can benefit from a wage premium from working from home, whereas lower income workers are less likely to be able to work from home, teleworking is likely to reinforce existing inequalities (Stantcheva, 2021[80]). Rural-urban disparities are likely to be exacerbated by differences in access to teleworking, while gender labour market disparities can be reduced by the greater likelihood of women in employment to work remotely (Stantcheva, 2021[80]). To continue to get the greatest benefits from teleworking, the government should disseminate best management practices for SMEs in particular, while working with social partners to reform labour laws to reflect new tele- and hybrid working arrangements across the income distribution, addressing concerns around issues such as hidden overtime and inappropriate home working environments.

Enhancing the benefits from strong female labour market participation

Danish women are well-integrated into the labour market thanks to strong educational attainment and supportive policy settings. The gap between employment rates of women and men is among the smallest in the OECD at 5.7 percentage points. The gender gap in employment is similarly low to other Nordic countries for people aged 15-54 but roughly 5 percentage points larger for those aged 55 to 64, suggesting a cohort effect that will bring the gender employment gap down further as this generation retires.The median wage gap for full-time employees of 4.9% is also relatively low (OECD, 2021[81]). The decline in women’s employment during the COVID crisis was similar to that for men, though a bigger fall in employment for women aged 25-34 is consistent with international evidence that mothers took on the bulk of the additional childcare responsibility when schools and childcare facilities closed (Sevilla and Smith, 2020[82]). Good access to parental leave and high-quality early childhood education and care helps support mothers to return to work, fostering gender equality in the labour market, though as recommended in the 2019 survey () more flexibility in the provision of childcare services would reduce the interruption to women’s pathway to senior and management positions. Taxes on the incomes of second earners fall around the middle of OECD countries (OECD, 2021[83]).

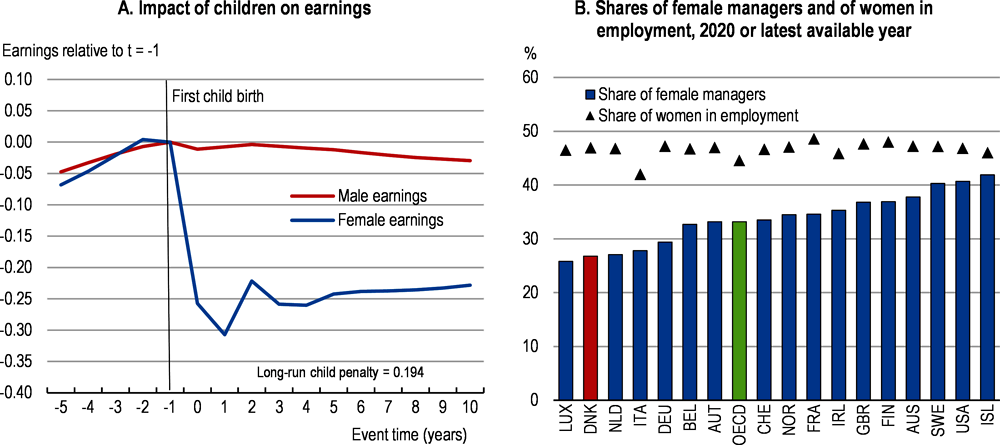

Despite the labour market success of Danish women, they still suffer a significant earnings penalty with motherhood (Figure 1.25, Panel A). One important step to remedy this is a more even split between the share of parental leave taken by mothers and fathers through implementing the EU-wide minimum of two months reserved for each parent (Table 1.7). Fathers who take leave are more likely to take an active role in childcare, even after they return to work. Danish evidence shows that when fathers take longer leave, mothers reduce their own leave and experience wage gains that increase overall earnings (Andersen, 2018[84]), consistent with quasi-experimental evidence from Canada that greater use of parental leave by fathers boosts female participation by more than it reduces male participation (Patnaik, 2019[60]). Denmark should monitor uptake after increasing the share of leave reserved for second parents, as the replacement rate of 53% of average earnings is below the OECD average (69%) (OECD, 2021[85]) and there has been low takeup in countries such as Japan, Korea and France with generous leave periods but below-average replacement rates (OECD, 2016[86]).

Danish women account for only a small share of managers (Figure 1.25, Panel B). Reporting of gender-disaggregated statistics to Statistics Denmark has been successful in reducing pay gaps (Bennedsen et al., 2019[87]), but there are no gender-based quotas for supervisory boards, which have been successful in raising the female share in a number of neighbouring countries including Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Norway, or managers. Providing female role models and mentors is critical to change gender stereotypes, support leadership development and access to networks for women (OECD, 2017[88]). Requirements for gender balance in positions of leadership need to be strengthened, potentially including quotas as a transitional tool to drive the shift and provide role models for women. By expanding the overall talent pool, a higher share of women in leadership positions boosts corporate performance in countries with otherwise high gender parity (Post and Byron, 2015[89]) and removing barriers to the allocation of women and minorities into high-skilled occupations can have a substantial effect on aggregate economic performance (Hsieh et al., 2019[90]). That said, there is little evidence that gender quotas for boards of directors have raised short-term economic efficiency elsewhere, notably in Norway where a 40% quota for the boards of publicly listed companies was introduced in 2008 (Smith, 2018[91]). Complementary reforms may be needed, such as reducing barriers to women working outside the public sector, where the female share of almost 70% is among the highest in the OECD.

Improving the integration of migrants

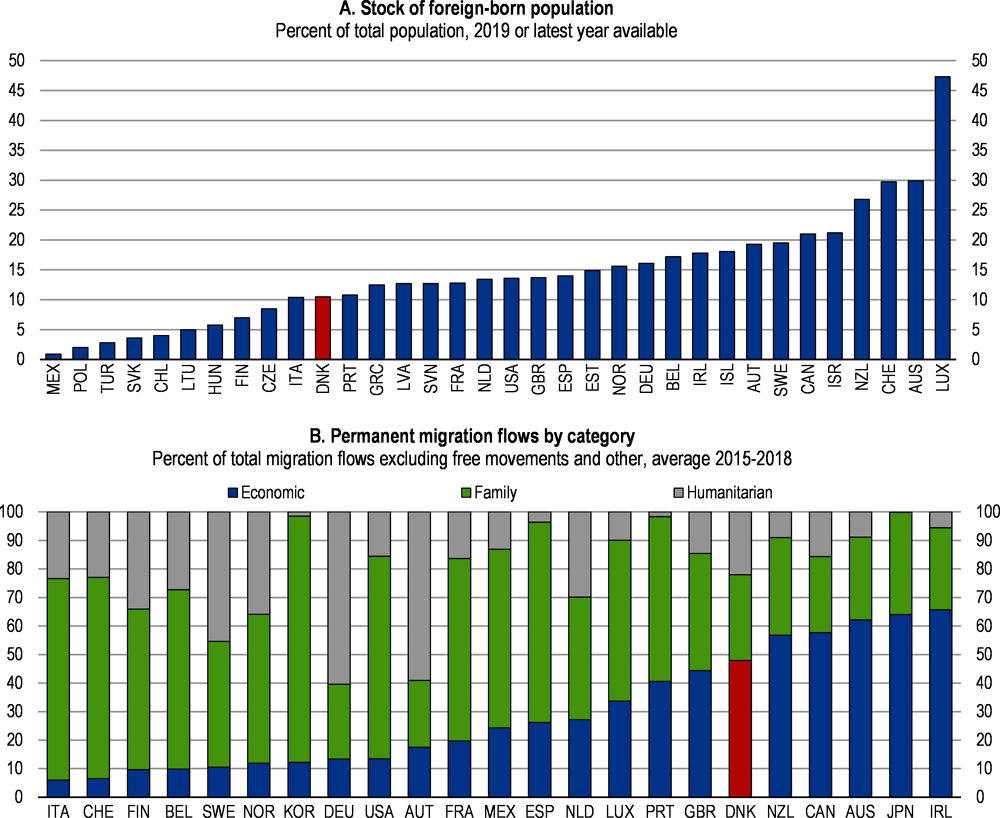

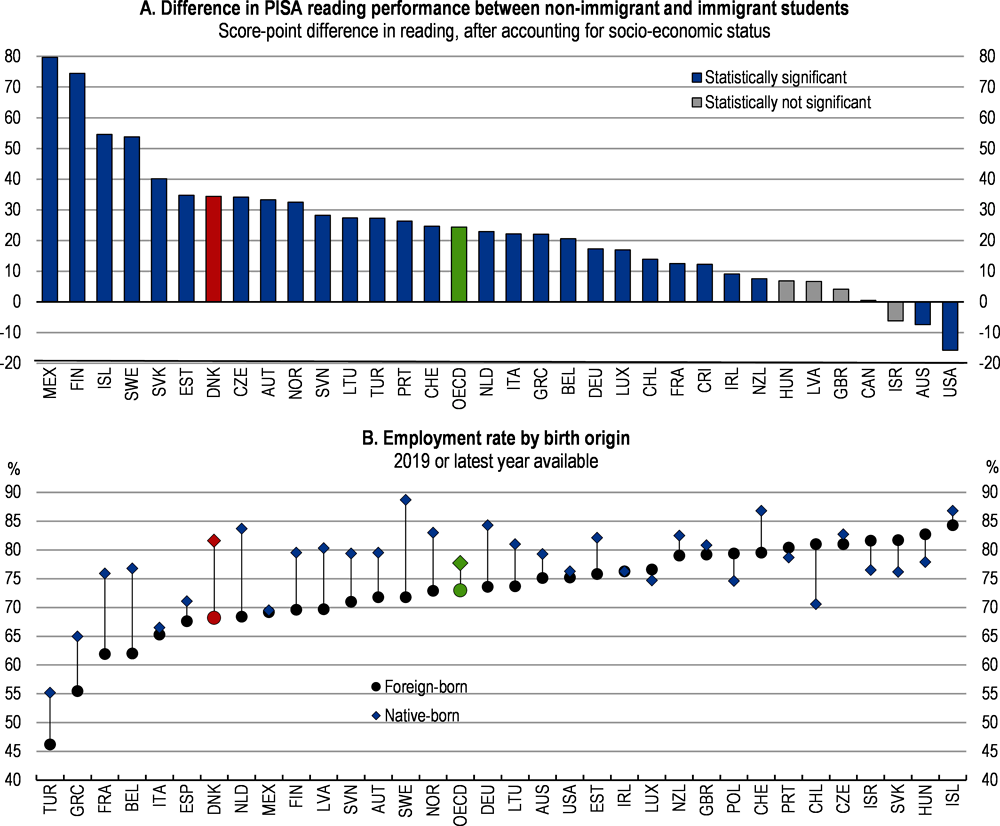

A relatively small share of the Danish population was born overseas, with the split between economic, family and humanitarian immigrants tilted towards workers (Figure 1.26). Foreign labour has the potential to increase productivity through new ideas and knowledge as well as complementary skills, but the benefits to Denmark are hampered by the large gap in employment and educational outcomes between immigrants and the native Danes (Figure 1.27). Reducing these gaps would benefit immigrants themselves as well as the economy more broadly, while enhancing the fiscal impact of immigrants, which is estimated at about -1% of GDP (Ministry of Finance, 2020[92]). Employment during the COVID crisis declined much more for the foreign born (-3.7%) than for people of Danish origin (-2.2%). In part this was because foreign-born people were more likely to be working in badly hit industries, notably transportation, accommodation and food services, and travel, cleaning and other operational services. By the second quarter of 2021, employment of immigrants and natives alike had exceeded the pre-crisis level.

As set out in the 2016 and 2019 Economic Surveys, the quality and implementation of integration programs for migrants is unequal across municipalities and should be improved. Subsidised employment schemes have had the largest effect on the rate of movement from social assistance to regular employment (Heinesen, Husted and Rosholm, 2013[93]) but the share of recent migrants in company-oriented employment or internships has fallen from a peak of 28% in 2017 to less than 20% in 2020 and 2021. The two-year Integration Education Programme established in 2016 and due to run until June 2022 has been succesful in building collaboration with employers and educational institutions to develop work experience, skills and networks while reducing hiring reticence on the part of employers (Rambøll, 2018[94]). This Programme should be extended and broadened further while working to reduce high dropout rates, partly due to low salaries. Enhanced language training should also be a key aspect of improving integration programmes: historical improvements in Danish language training for refugees had a significant permanent positive effect on earnings, led to better outcomes for their children and carried a benefit-cost ratio of up to 15 to 1 (Arendt et al., 2021[95]). Municipalities still see insufficient Danish skills as one of the greatest barriers facing unemployed immigrants (VIVE, 2021[96]) and the Danish Education Association (2015[97]) has proposed improving integration through intensive Danish language training during the first 6 months and language mentoring once immigrants are in work. Providing greater certainty to refugees that they will be able to stay in Denmark would increase their incentives to integrate and learn Danish.

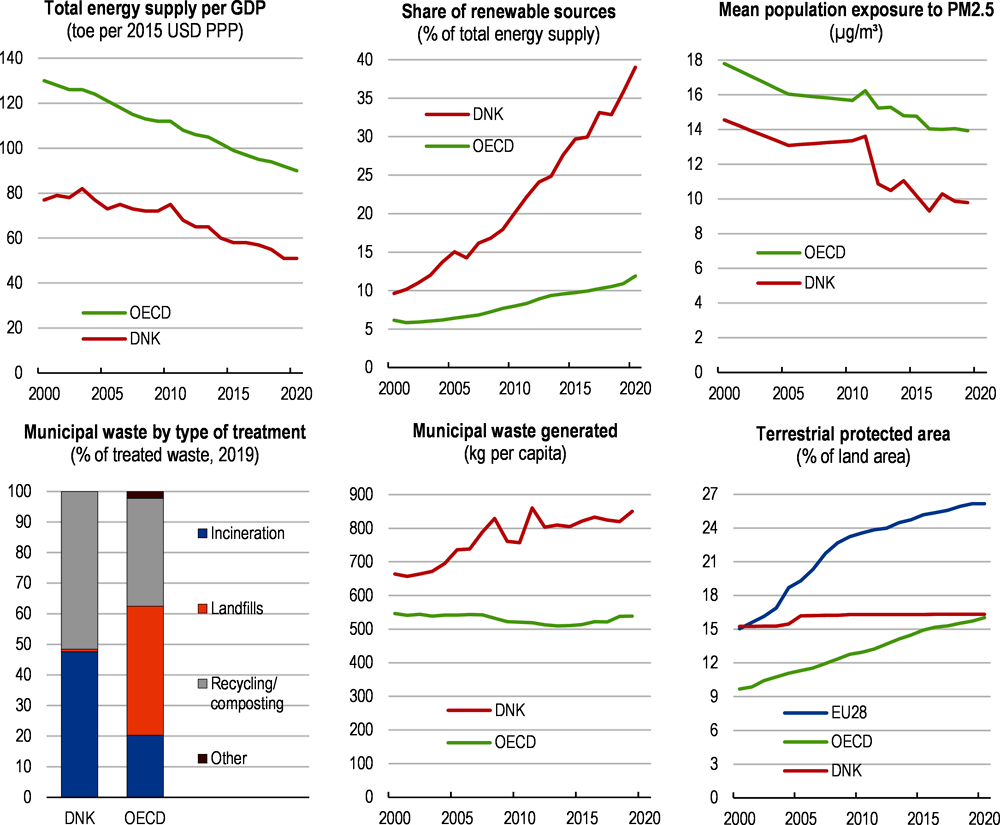

Demark performs relatively well and has made notable progress across a range of environmental indicators (Figure 1.28). Apart from being a green energy pioneer, the country has also succeeded at mitigating air and water pollution with ambitious and innovative policies. The development of renewable energy, proactive energy efficiency policies and tightened regulation of vehicles, while reducing greenhouse gas emissions, also contributed to a substantial improvement in air quality. While exposure to particulate air pollution exceeding WHO recommendations (10 micrograms per m3) concerned nearly all inhabitants in 2000, it now affects a minority (36% of the population in Denmark against 74% of the European Union), and premature deaths related to particulate matters have also dropped. However, the average exposure of Denmark’s inhabitants still exceeds WHO recommendations, particularly in urban areas.

Denmark is also performing well on a number of waste management indicators. It has succeeded in reducing its share of landfilled waste to less than 1% of municipal waste (against 39% in all OECD countries), with more than half incinerated. Recovery and recycling rates exceed 85% for construction and destruction, end-of-life vehicles, and waste electrical and electronic equipment (OECD, 2019[98]).

This success stems from a long tradition of using a policy mix of economic incentives, together with support for innovation and green technologies, ambitious targets and an effective centralised governance for the environment. Environmental taxation amounts to 3.4% of GDP, ranking highly among OECD and European OECD countries (respectively 2.1% and 2.3% of GDP on average), mainly for taxing air emissions (including greenhouse gases, but also NOx and SOx). Taxation on landfilling and incineration succeeded in creating strong incentives and reducing landfilling (though incineration is still high). Denmark is also among the few countries that has implemented a tax on pesticides for agriculture, discouraging the most harmful substances by calibrating rates to their impact on the environment and human health. Finally, water discharge in the countryside is charged relative to the pollution load, applying to nitrogen, phosphorous and organic material (OECD, 2019[98]). Conversely, in agriculture, practices allowing for more efficient use of nutrients are subsidised at their cost (Chapter 3).

Despite progress, weaknesses remain with regard to water quality, biodiversity and waste. Although Denmark has successfully reduced its nutrient discharges using regulation and economic incentives, the nutrient balance of agriculture is still higher than the OECD average, contributing to the poor quality of surface water: 27% of all surface waterbodies and 62% of coastal waterbodies are in bad or poor ecological state, according to the Water Framework Directive classification, relative to 16% of all EU surface water bodies and 9% of EU coastal waterbodies (EEA, 2018[99]). Facing similar issues on nitrogen pollution, the Netherlands in March 2021 adopted a new law with a comprehensive programme of nitrogen-reduction measures, supported by a monitoring system that will allow measures to be adjusted according to EU directives (OECD, 2021[100]). In Denmark, the share of protected areas at land is still low relative to other countries (Figure 1.28 above), particularly as regards to the EU objectives of establishing protected areas for at least 30% of lands and 30% of marine areas. This is partly due to the fact that Denmark is a densely populated country with a high share of land with intensive agricultural production and production forest land. Denmark is in the process of designating 19 new protected areas at sea which will allow to reach the 30% target (form 19% today) Habitats and biodiversity are also under threat, particularly in marine environments, as 55% of known species and 95% of habitats are considered to have a poor or bad conservation status in Demark, both of which are high relative to other EU countries (EEA, 2020[101]). In 2020 a broad political agreement was made in Denmark about a Danish Nature and Biodiversity Package, including up to 75 000 hectares of untouched forest, establishment of 15 new nature national park with a DKK 888 million budget for 2021-2024.

Efforts also remain to establish a circular economy, as Denmark has a very high material consumption and municipal waste volume per capita, showing a failure to consume low-material goods and to enhance circular economy patterns for municipal waste. A strategy to prevent or recycle waste is crucial, with clear objectives, milestones and responsibilities and the Action Plan for the Circular Economy published in July 2021 for the period 2020-2030 paves the way for a carbon neutral waste and recycling sector. However, this would require a new waste management pattern in the long term, dealing with the reduced supply of waste for energy generation. The use of large-scale electric heat-pumps and alternative fuels for residential heating, as recommended in Chapter 3, would efficiently address this risk of shortage without recourse to importing more waste for burning.

The large synergies between climate mitigation strategies and other environmental objectives should be harnessed (OECD, 2019[102]). Agriculture offers a particularly favourable ground for such synergies, as arable land covers 60% of Danish terrestrial territory (Chapter 3). Practices that contribute to carbon sequestration in soils and reduced nutrient loads in the environment generally also benefit biodiversity, as well as the quality of air, soils and waterbodies. Similarly, many measures that reduce transport or residential CO2 emissions will also improve air quality, such as the restriction of high-emission vehicle use or the electrification of house heating. Denmark has made progress in sustainable fishing practices and the fight against overfishing, notably through strong monitoring of fishing activities and endorsement of the Marine Stewardship Council label (over 85% of Denmark’s catch) (OECD, 2019[98]). Such action directly benefits marine biodiversity and habitats and secures resources for future economic growth, but can also preserve marine ecosystems and their capacity of to store carbon (Sala et al., 2021[103]) (Mariani et al., 2020[104]).

The integration of environmental dimensions other than climate change in policy decisions will help identify synergies and options to enhance them. It will also highlight the risk of trade-offs and help address them so that they do not turn into barriers to action. The material consumption and emissions to build low-carbon technologies (e.g. CCS plants or wind turbines) or non-exhaust pollutions from brakes, clutches, tyres and road surfaces due to electric vehicles use for instance, should be accounted for, even if life-cycle emissions of renewable technologies are overall much lower (IPCC, 2014[105]). Assessing the material impact of these technologies would also help anticipate waste management and alleviate detrimental environmental impact, for instance by integrating the material in the circular economy (Wind Denmark International, 2019[106]). Valuing a broad range of natural assets in policy decisions can be a first step forward (Dasgupta, 2021[107]).

References

[52] Agrawala, S. et al. (2010), “Plan or React? Analysis of Adaptation Costs and Benefits Using Integrated Assessment Models”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 23, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5km975m3d5hb-en.

[45] Alvarez, J., M. Kallestrup-Lamb and S. Kjærgaard (2021), “Linking retirement age to life expectancy does not lessen the demographic implications of unequal lifespans”, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, Vol. 99, pp. 363-375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.insmatheco.2021.04.010.

[84] Andersen, S. (2018), “Paternity Leave and the Motherhood Penalty: New Causal Evidence”, Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 80/5, pp. 1125-1143, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12507.

[5] Andersen, T., M. Svarer and P. Schrøder (2020), Rapport fra den økonomiske ekspertgruppe vedrørende udfasning af hjælpepakker.

[95] Arendt, J. et al. (2021), Language Training and Refugees’ Integration, IZA Institute of Labour Economics Discussion Paper No. 14145, http://ftp.iza.org/dp14145.pdf.

[4] Bennedsen, M., I. Birthe Larsen and D. Scur (2020), “Preserving job matches during the COVID-19 pandemic: Firm-level evidence on the role of government aid”, Covid Economics, Vol. 27, pp. 1-30.

[87] Bennedsen, M. et al. (2019), Do firms respond to gender pay gap transparency?, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25435/w25435.pdf.

[31] BIS (2021), Credit-to-GDP gaps, https://www.bis.org/statistics/c_gaps.htm.

[73] Calvino, F., C. Criscuolo and R. Verlhac (2020), “Declining business dynamism: Structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 94, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/77b92072-en.

[36] Carreras, O., E. Davis and R. Piggott (2018), “Assessing macroprudential tools in OECD countries within a cointegration framework”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 37, pp. 112-130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2018.04.004.

[24] Cavalleri, M., B. Cournède and E. Özsöğüt (2019), “How responsive are housing markets in the OECD? National level estimates”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1589, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4777e29a-en.

[35] Cerutti, E., S. Claessens and L. Laeven (2017), “The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 28, pp. 203-224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2015.10.004.