1. Key policy insights

The longest expansion on record came to a juddering halt with the worldwide spread of the coronavirus. The containment measures introduced have contributed to the economy suffering one of the largest shocks outside wartime and leading to extremely high unemployment. A rapid and substantial policy response has aimed to shield households and businesses from the worst of this shock. As the economy re-emerges from the shutdown pressures on public finances will be intensified, but policy support should remain available while the economy is operating well below capacity. Sanitary measures remaining in place until the coronavirus is eliminated will weaken an already sluggish productivity growth and population ageing will continue constraining the available labour supply. The government should therefore continue to focus on structural reforms liberalising productive forces, especially by removing regulatory barriers that stand in the way of boosting productivity. Helping Americans go back into employment and acquire the skills needed to take advantage of new job opportunities will also support the return of the high levels of prosperity American’s have enjoyed in the past.

The coronavirus pandemic threatens achievements made over the last decade in boosting material standards of living. For American households, unemployment has risen precipitously and while government interventions have shielded most families from the brunt of the shock, prospects are now less certain.

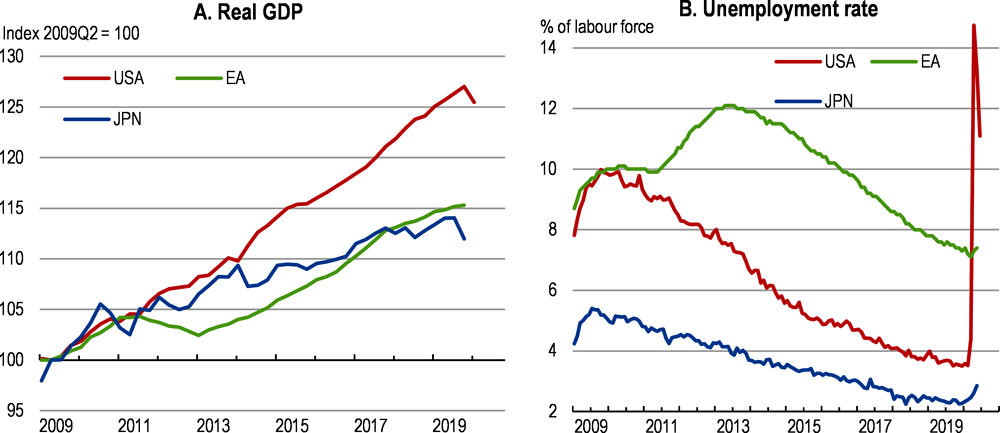

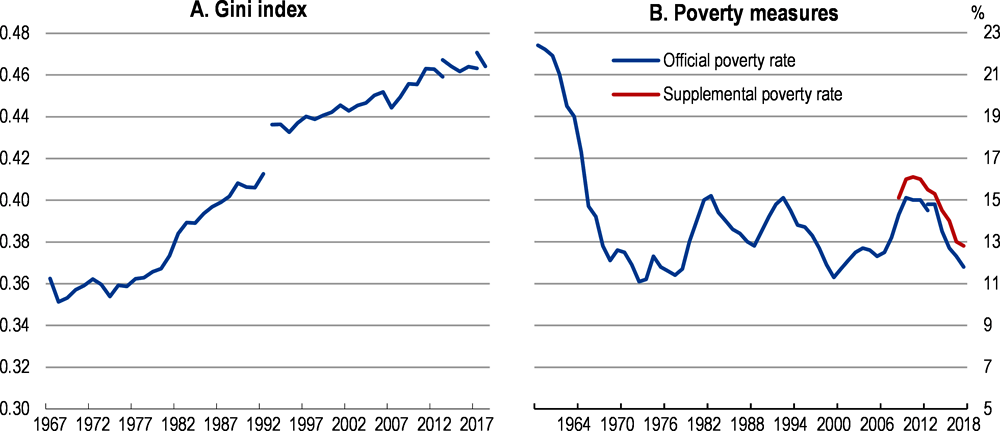

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus, the United States had benefitted from resilient economic growth during the 2010s. In 2019, the economic expansion and the unbroken string of monthly job gains became the longest on record (Figure 1.1). The strength of the labour market had gradually induced those on the margins to increase their participation. Strong job gains and gradual increases in real wages helped raise household incomes, bringing to an end the previous flat trend in median real income. Measures of poverty stabilised, although at relatively high levels. Indeed, as the labour market tightened the wages of those towards the bottom of the income distribution increased more rapidly than median wages. This had improved wellbeing for many Americans, as measured by the Better Life Index. Despite progress, income and wealth inequality have been persistently high and many Black and African Americans and indigenous populations remain in the low-income groups. Furthermore, the income gains to the workforce may not be widely shared due to polarisation of earnings. Large disparities also exist across the country. For example, differences in a suite of health outcomes measured by the OECD’s Better Life Index are dramatic, with states, such as Mississippi, among the worst performers in the OECD.

The economy is projected to see a marked contraction in economic activity in 2020 before partially recovering in 2021. As confinement measures are lifted, much of the dislocation caused by shelter-in-place orders will wane, many businesses will reopen and most workers return to work. However, policy support will continue to be needed as the shock will dent prospects for some industries, such as the hospitality sector, and many workers will have lost their attachment to employers and will face difficulties in finding new jobs. The consequences of the coronavirus shock will likely lead to business failures and sectoral shifts in output that will require many workers to find new jobs. Against this background, the main messages of the Survey are:

Macroeconomic policy still needs to provide additional support in the near term to help the recovery and should remain ready to act in case of further waves of contagion or unexpected downturn.

Lowering regulatory barriers will facilitate the return to sustained growth, especially regulations in the labour market, because they prevent workers from realising their potential and employers from getting the right skills. Occupational licensing and restrictive land use regulation should be eased because they hinder people moving to more productive jobs.

Under-privileged groups should be supported, especially workers who have not completed a college education, through supporting a strong recovery and lowering regulatory barriers to their labour-market participation, while considering how to strengthen education, training, lifelong learning and health policies. Such measures will improve the employability and opportunities of those groups lagging behind and typically those who fare less well during downturns.

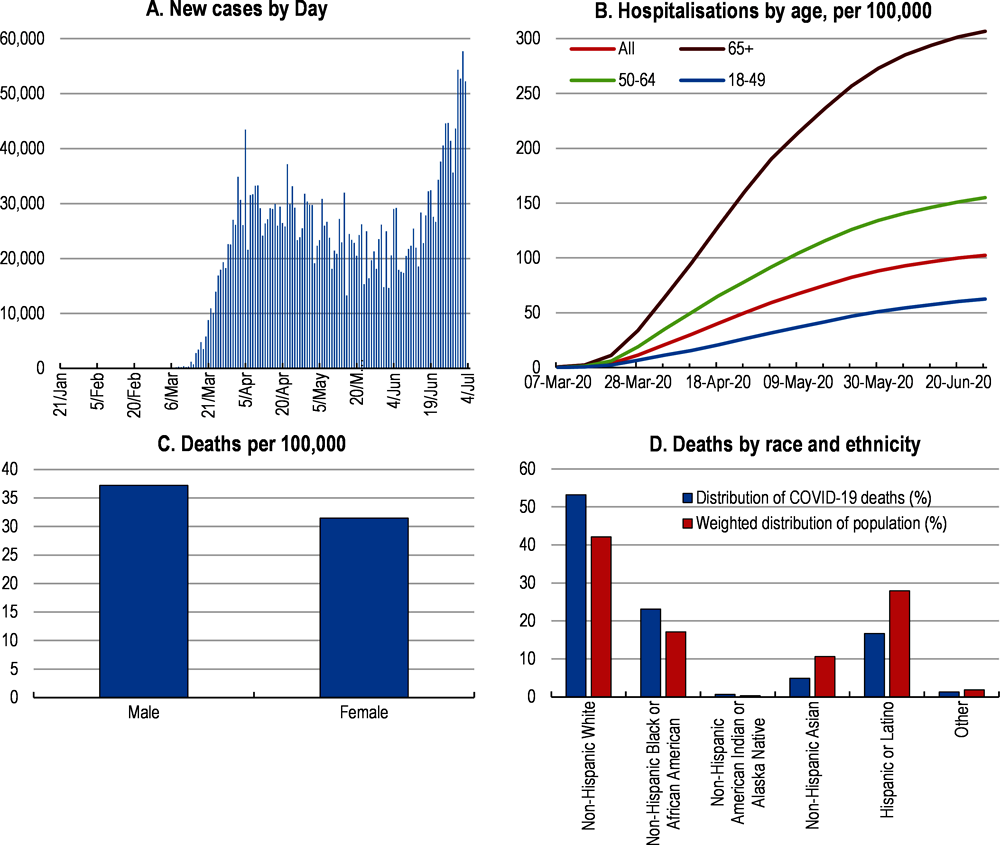

Since the first case recorded in late January, the spread of the coronavirus has been rapid and by May 2020 over one million Americans have been diagnosed with COVID-19, with important clusters in several large metropolitan areas. Even though the US health system was apparently well placed to deal with a pandemic, ranked as having a high ability to respond rapidly and mitigate the spread of a virus and with comparatively large health care capacity (GHS Index, 2019[1]), the coronavirus pandemic has proven difficult to bring under control. Confinement measures decided in most states have helped to flatten the curve of new cases, but there are large uncertainties about the future course of the pandemic. The incidence of COVID-19 appears to disproportionally affect the elderly, black and African Americans, while mortality risk appears elevated for men (Figure 1.2).

As the coronavirus started to spread, states implemented distancing strategies to slow the contagion. Most states closed schools and nonessential businesses, restricted public gatherings and then issued Shelter-in-Place orders, with the first being introduced in California in late March. Some states began to relax containment measures in late April, adopting a phased re-opening of the economy. Typically, schools and bars, restaurants and places of entertainment remained closed in May 2020, but other sectors can begin to operate with some restrictions requiring distancing in the workplace and staggering shift times. The ambition is to replace non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as lockdowns, with increased testing and contact tracing while avoiding overburdening the health sector. At the federal level, support for testing provides a complement for state strategies to reopen their economies.

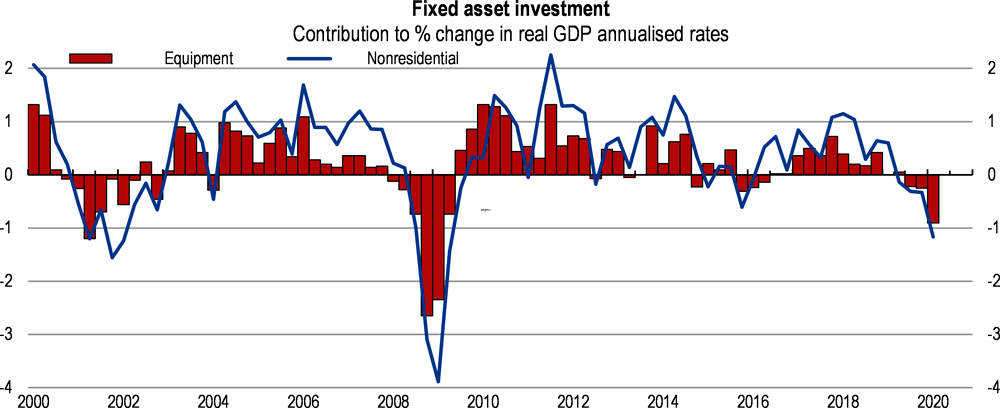

The containment measures, businesses shutting down, and households staying at home have led to a severe contraction in economic activity. Activity in the entertainment sector and passenger transport has been decimated. This has provoked an unprecedented sharp increase in unemployment. Over 20 million workers lost their jobs during April, far quicker than during the 2008 financial crisis or even the Great Depression. To compound the coronavirus shock, the oil price collapsed as supply overwhelmed storage capacity. By early May, drilling activity was down by 50% on the beginning of the year and contributed to the slump in investment (Figure 1.3). Financial markets have shown signs of stress with yields surging in some markets and measures of asset prices falling by around one fifth.

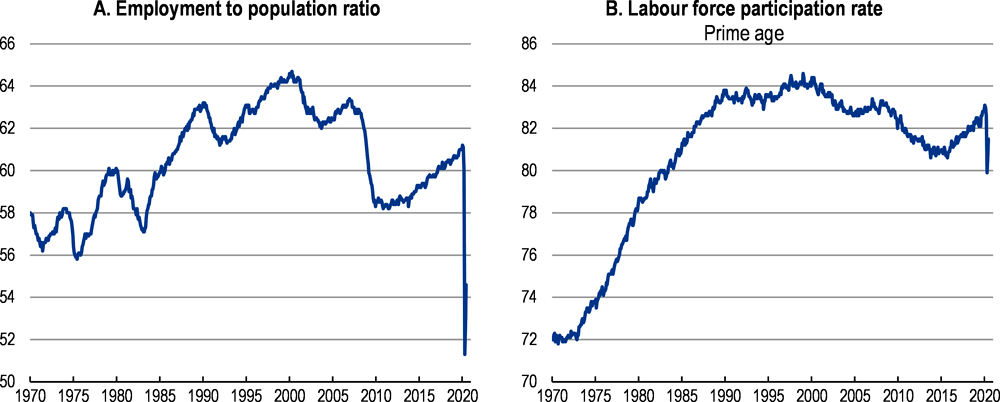

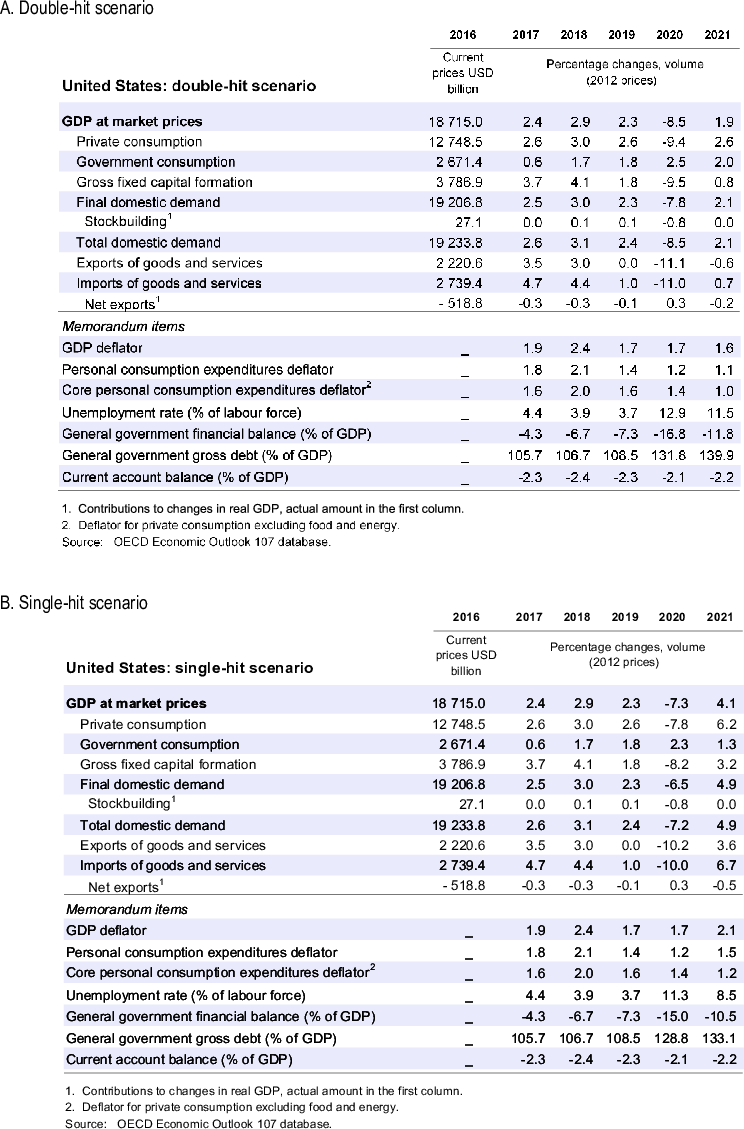

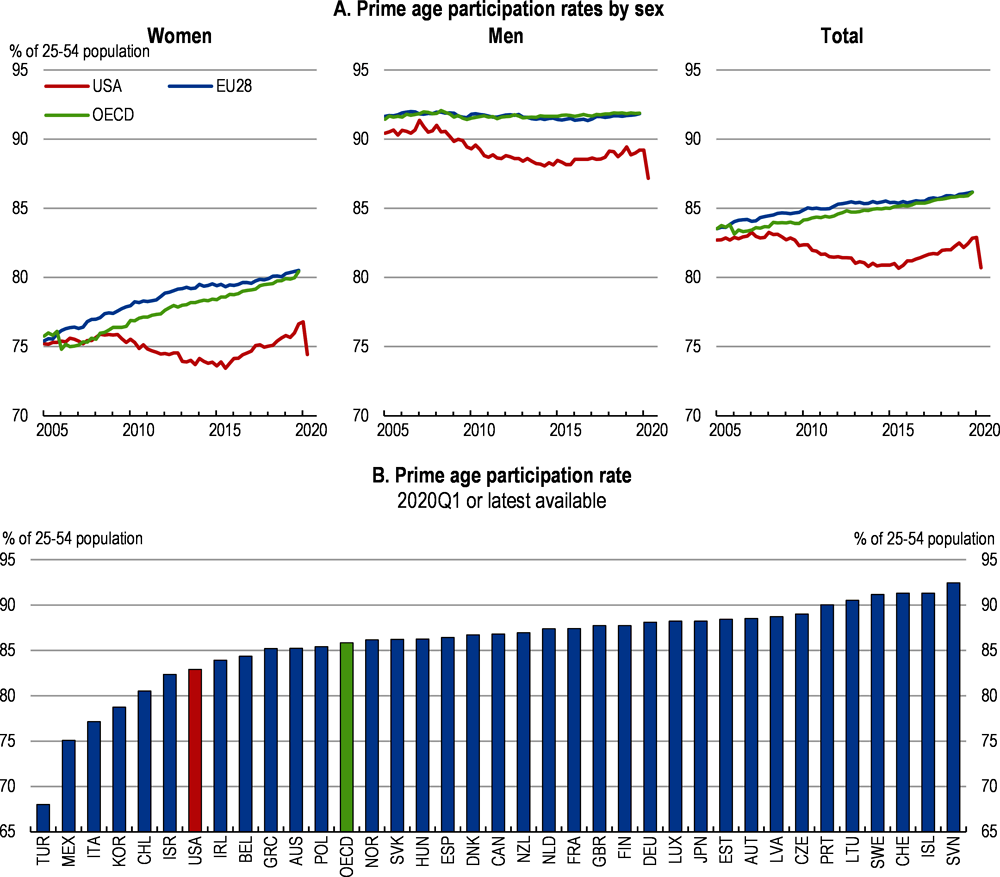

The economy is set to climb out of the coronavirus recession as states and sectors sequentially reopen (Table 1.2). The economy was largely constrained by shelter-in-place measures through most of April and May but then reopened with restrictions lingering in sectors and parts of the country where distancing remained a concern. Nonetheless a renewed wave of coronavirus infections remains a possibility. In the double-hit scenario a renewed, but milder, outbreak of COVID-19 infections is assumed to occur in October and November. To minimise the risk of a second wave leading to another large-scale lockdown of the economy to protect lives, developing testing to identify those infected and then tracking and isolating to limit further infections will be needed. Augmenting medical capacity to cope with a second wave and identifying those who have acquired immunity will help mitigate the impact on the economy of a second wave by facilitating greater reliance on targeted measures to limit the spread of the virus. In the single-hit scenario, the economy is assumed to recover gradually as the distancing restrictions are lifted. An unusually large share of the unemployed are on temporary furlough, which suggests that many will regain employment relatively quickly, providing a strong rebound in the short term. However, employment dropped dramatically and many workers have not retained attachments to employers (Barrero, Bloom and Davis, 2020[2]). In addition, some businesses will face uncertain futures, particularly if liquidity problems translate into solvency issues. Furthermore, labour force participation dropped sharply to levels not seen since the early 1980s (Figure 1.4). A large fall in prime-age participation also occurred during the 2008 financial crisis and took around a decade to reverse with some of workers facing greater difficulties re-entering the market, such as those with lower levels of educational attainment.

During the recovery from the financial crisis in 2008, the unemployment rate came down relatively gradually over a long period, partly due to workers slowly re-entering the labour force. In part, this reflected the difficulties in making employer-employee matches, especially for a worker who has dropped out of the labour force. Congress has recognised this threat and set up the Paycheck Protection Program to help small businesses keep workers on their books. While the initial sums available were quickly oversubscribed, the early indications are that millions of workers have lost this link. As such the unemployment rate is assumed to decline relatively gradually also after the current recession. In addition, a reallocation of labour across sectors is likely to be required during the recovery, as activities requiring face-to-face contact, such as travel and accommodation, will be affected to infection risks, while other sectors, especially health and digital services, will benefit from rising demand. Past experience shows that inter-sectoral labour reallocation takes time because of retraining needs and is impeded by regulations, such as occupational licensing.

Weakened consumer demand in conditions of elevated unemployment and heightened uncertainty will depress business investment, which is likely to weaken productivity growth. With high unemployment rates, inflation is set to be quiescent throughout the projections. These projections are subject to substantial uncertainty and risks as the world continues to grapple with the coronavirus pandemic (Table 1.1). Macroeconomic policy should be ready to act further if required, including by continuing to support the economy as it emerges from lockdown.

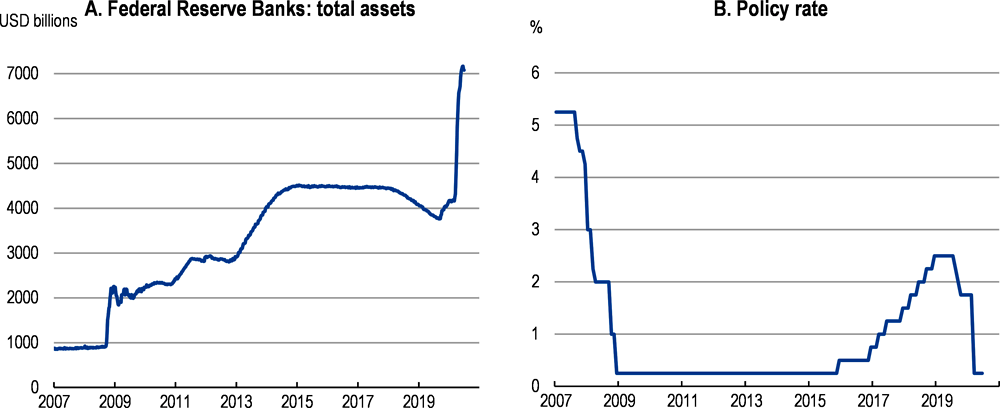

Monetary policy reacted forcefully and quickly to the emerging coronavirus crisis. The Federal Reserve dropped the target range for the federal funds rate to 0-0.25% in two unscheduled meetings and then announced the resumption of large scale purchases of Treasury and agency Mortgage-Backed Securities to address a severe deterioration in the functioning of these critical markets. These purchases, have swollen the size of the balance sheet far quicker than was seen during the 2018 global financial crisis (Figure 1.5). Statements made clear that the federal funds rate would remain low giving markets forward guidance. As a result of the shock, wage and price inflation is likely to remain muted and continue the prolonged period of undershooting the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target. In the medium term, weak productivity growth coupled with reshoring and diversifying supply chains may put upward pressure on prices. If inflation were to pick up more robustly and the real economy safely recovered the Federal Reserve would then be able to scale back asset purchases and ultimately raise interest rates once again.

In responding to the coronavirus shock, monetary policymakers have enhanced and expanded their tools. Forward guidance and quantitative easing used in the Great Recession proved their mettle and are now familiar to market participants, although there is concern that increasing the balance sheet further may diminish the effectiveness of balance sheet tools. There are options to buttress forward guidance, such as by committing to buy bonds at specific maturities (Brainard, 2019[3]). Other Central banks have already adopted negative interest rates. In the United States, the structure of the capital markets would make it more difficult to implement them (Bernanke, 2020[4]). The Federal Reserve has examined this option and decided that it is not an attractive monetary policy tool in the United States (FOMC, 2019[5]). Given potentially limited room for manoeuvre, drawing up contingency plans for forward guidance and large scale asset purchases, including the possibilities for expanding the range of eligible assets in case of an even more severe downturn would be advisable (Gagnon and Collins, 2019[6]).

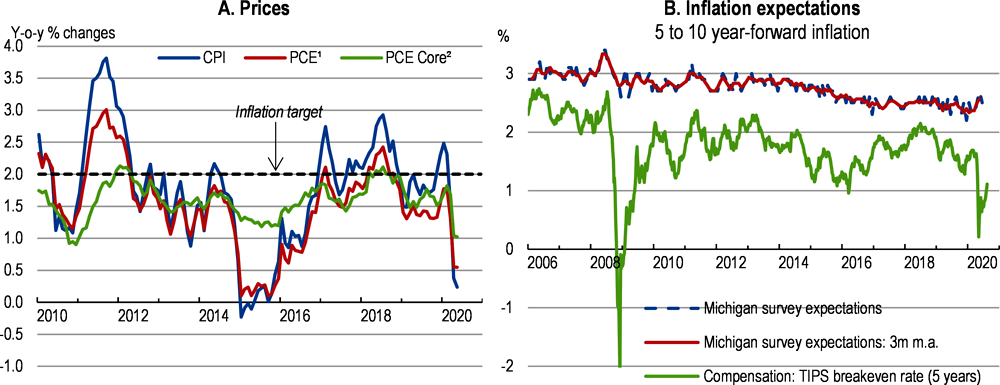

Continued undershooting of the symmetric inflation target of 2% is a concern for meeting the price stability part of the Federal Reserve’s mandate in the future. This may be particularly worrisome given the slide in some measures of inflation expectations to low rates by historical comparison (Figure 1.6). If inflation expectations become anchored at these rates and inflation and interest rates decrease in response, monetary policy will be unable to respond to future downturns using conventional tools as aggressively as it has in the past.

Against the backdrop of interest rates likely to remain lower in the future as inflation rates have declined (Kiley and Roberts, 2017[7]), the Federal Reserve has undertaken a review of its monetary policy framework. One essential aspect of this review will be to ensure central bank communication is effective, particularly when policy rates are near or constrained by the effective lower bound. In this environment, explaining clearly the future path of policy rates will be crucial. It is thus vital that monetary policy independence is maintained. Changes to the monetary policy framework should make clear that the inflation target is symmetric (as recommended by past OECD Economic Surveys). One option is to allow the Federal Reserve to meet the inflation target on average, with explicit overshooting of the inflation target during expansions to offset undershooting during contractions. Average inflation targeting would potentially help stabilise inflation expectations around the inflation target. However, the operationalisation is complicated. Analysis by Reifshneider and Wilcox (2019[8]) point to a number of drawbacks if the review leads to a rules-bound approach. These include the possibility that rules may not be able to prevent inflation expectations from sliding, they may not be aggressive enough in the case of a large shock and also lack credibility. In addition, rigid policy rules that include explicit demands to make up for inflation shortfalls may be difficult to implement due to communication challenges if they arise from idiosyncratic and temporary supply shocks (Box 1.1). In this context, retaining discretion will be important in setting policy.

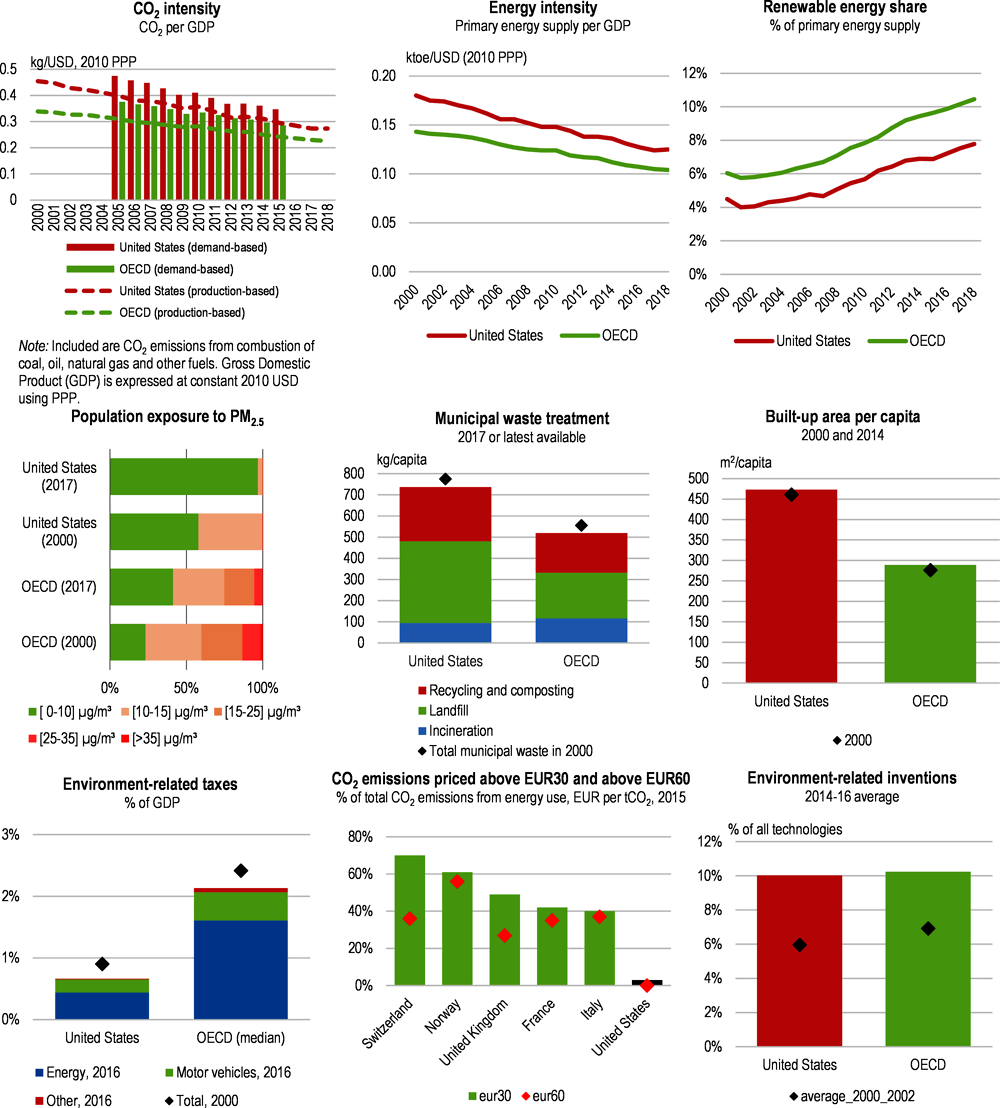

A new area of challenges is how monetary and financial policy should adjust to enhanced climate risks (Brainard, 2019[9]). Mitigation and adaptation measures will affect prices and employment, which may require monetary policy to react to the extent to which these shocks are temporary or permanent. The resilience of the financial sector to possible changes in asset valuations is another climate related risk. They can arise if policy changes create stranded assets affecting balance sheets. Companies are increasingly reporting climate-related financial exposures. The 500 largest firms have estimated exposures totalling $1 trillion. Other central banks, such as the Bank of England and Banque de France, are including climate risks in their stress testing of the financial system. Against this background, systematically assessing financial institutions’ exposures to climate-related risks through rising sea levels and potential flooding, fires and regulatory changes, such as energy efficiency standards creating stranded assets would complement existing stress tests without adding to the regulatory burden.

The financial markets were hit hard by the coronavirus shock. Asset prices in stock markets dropped sharply and by early May were around one-fifth lower than their peaks recorded in February. Credit markets also showed signs of strain, with yields in different markets surging as liquidity dried up. This led the Federal Reserve to create a suite of new lending facilities (see Box 1.2). Liquidity facilities have been created to underpin credit for securities firms, money market mutual funds, major companies and state and local governments. An additional facility to target lending to “main street” businesses is an innovation expanding support to sectors traditionally far beyond the purview of monetary authorities. In addition, prudential regulators have temporarily relaxed some requirements for the financial sector to avoid credit drying up.

The Federal Reserve moved quickly to prevent liquidity drying up on different markets by resurrecting or introducing new loan facilities, extending the reach of the central bank across the economy. These include:

Primary and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities to provide liquidity for corporate bonds,

Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility that will support the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS) backed by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration

Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility to support the flow of credit to short-term funding markets.

Municipal Liquidity Facility to help state and local governments manage cash flow pressures after the municipal bond market showed signs of stress.

Main Street Business Lending Program to support lending to small-and-medium sized businesses.

These facilities are supported by equity investments by the U.S. Treasury in order to ensure that the Federal Reserve will not have to absorb losses.

In addition, the Federal Reserve established liquidity swaps with foreign central banks to prevent the disruption of credit that may occur with the breakdown of bank funding markets. The swap lines provide dollar or foreign currency liquidity to institutions during times of market stress.

To support initiatives to shore up credit markets, the financial regulators have advised banks to work constructively with customers in modifying loans, eased compliance requirements for lenders, delayed implementation of new regulatory requirements, targeted temporary changes in capital requirements, reduced reserve requirements and increased the availability of the discount window to meet liquidity needs and support customers by ensuring the continued functioning of financial markets.

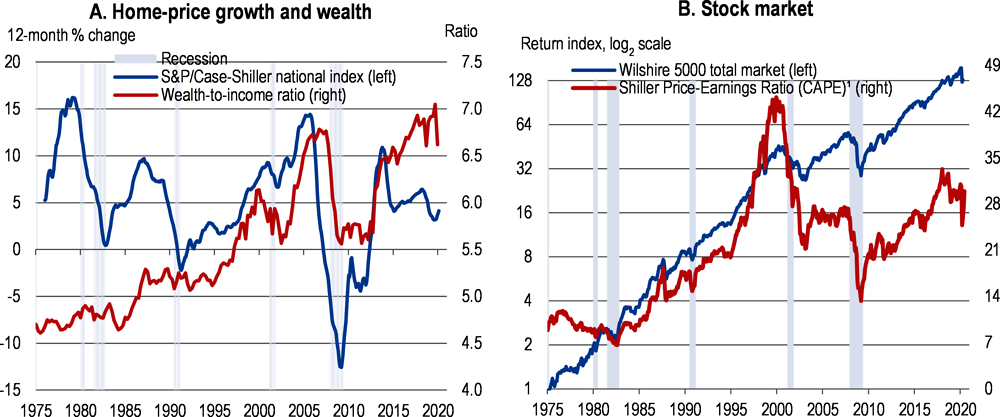

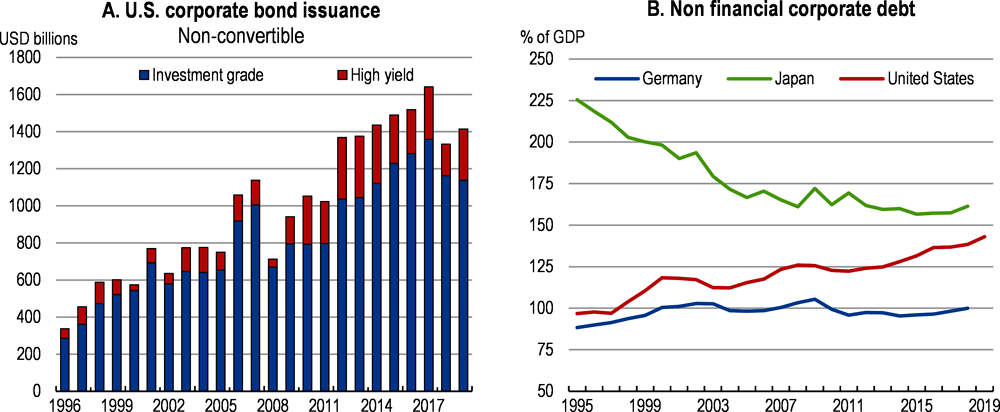

The banking sector appears to have withstood the initial impact of the coronavirus shock. However, the long period of low interest rates - which contributed to elevated asset prices (Figure 1.7) - is likely to continue. The low interest rate environment had supported high stock market valuations and house prices in some cities, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego. Concerns about the sharp retrenchment in asset prices since the start of the coronavirus pandemic are mitigated by relatively healthy household balance sheets, at least on aggregate. A somewhat larger concern is that the scale of loans in the non-financial corporate sector is at historic highs (Figure 1.8). Furthermore, some evidence indicates that the firms that had been amassing large debt loads were those with high leverage and low earnings and cash holdings. In addition, credit quality had deteriorated. The share of non-bank institutions in segments of the financial markets had been growing more important, such as syndicated loans.

The vulnerabilities in the corporate sector creates risks (Federal Reserve, 2020[10]). With economic activity contracting sharply, highly leveraged firms are particularly exposed to default risks while the economy recovers. Liquidity support to bridge a period of subdued earnings may leave firms with even higher leverage. Ratings downgrades and pressures on the corporate bond market could amplify the economic downturn if earnings remain weak and firms face difficulties in refinancing existing debt.

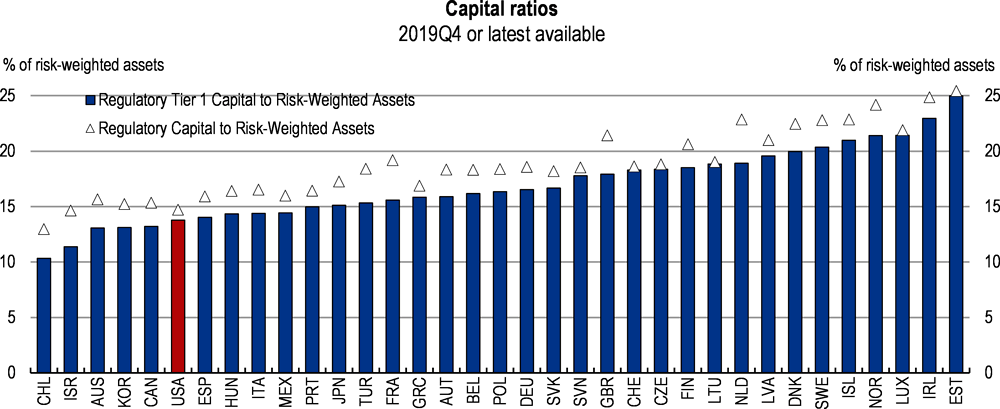

The constellation of risks requires careful monitoring and action to prevent them, particularly those from the non-bank sector, ultimately materialising on bank (or government) balance sheets. The weaknesses revealed in governance and controls in some of the larger banks warns against complacency. The early experience of the coronavirus pandemic, suggests that the banking sector has weathered the shock, validating the efforts of lawmakers and regulators to strengthen banks resilience. In this light, maintaining robust prudential regulation on banks, particularly the largest systemically important financial institutions, remains essential. The policy framework for financial stability has improved since the 2008 financial crisis, with the implementation of the Dodd-Frank Act. Strict regulation and supervision particularly of larger banks and systemically important financial institutions, including monitoring of capital adequacy and conducting stress tests have played a role in boosting banking sector resiliency (Figure 1.9). For example, non-performing loans have decreased steadily and accounted for only around one percent of total loans on the eve of the coronavirus crisis. However, this situation may deteriorate rapidly as the economy emerges from the lockdowns and liquidity support is withdrawn. Small and medium sized enterprises are likely to be particularly vulnerable, but also enterprises in sectors, such as hospitality, may also come under stress. The corporate bankruptcy system works effectively although if particular asset classes face more uncertain prospects leading to solvency concerns uncoordinated action by creditors runs the risk of triggering fire sales. Finally, the Federal Reserve has begun to release publically a regular Financial Stability Report to assess emerging risks (as recommended by past Economic Surveys).

Prudential regulation can create trade-offs in terms of access to credit, as typically smaller relational lenders, who are often important for low-income households, incur proportionally large costs in meeting regulatory standards. The authorities have reacted to the proportionally heavier regulatory burden imposed on the smaller banks and have acted to lighten it on the banks least likely to threaten financial markets. Additional policies to foster financial inclusion would support access to credit of under-banked groups (Box 1.3). In the longer run, the Federal Reserve could alter macroprudential policy to be more dynamic varying counter-cyclical capital buffers over the cycle to further strengthen the resilience in case of a downturn. This should be gradually introduced with the aim of being operational over future cycles.

Previous OECD Economic Surveys have argued for housing finance reform to target improving housing affordability in the rental market, which is likely to benefit lower-income households, while reducing taxpayer exposure to costly bailouts. The government-sponsored enterprises, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, remain important players in the housing market and their portfolios are designed to help provide affordable housing. However, the housing finance system remains essentially unchanged since they were taken into government conservatorship in the midst of the sub-prime crisis, and as the housing market has recovered they have made profits. More recently, some recapitalisation has been allowed. Greater recapitalisation may provide preconditions for the government to step back from guaranteeing these enterprises. A number of options exist depending on the desired involvement of the private sector in the mortgage market (CBO, 2018[11]). Decisions about the size of the capital base for the government-sponsored enterprises will partly determine the government’s credulity in distancing itself from pressure for bail outs.

Low-income households are less likely to have access to banking services (Azzopardi et al., 2019[12]). For poorer households, social and demographic characteristics appear to be potent covariates with access to banking services (Hayashi and Minhas, 2018[13]). These include educational attainment, the age of the head of the household, internet access, race, employment status and homeownership. Technological solutions may be feasible to address access to banking services for these demographic groups. Amongst low-income households, access to the internet is associated with an 11 percentage point increase in the probability of being banked.

Access to banking services has recovered after the financial crisis and now only around 7% of households are unbanked. Community banks can play an important role in offering traditional banking services, they provide the sole bank branch in around 40% of counties in the United States (CEA, 2019[14]). These banks account for 92 per cent of federally insured banks and are responsible for 16% of total loans and leases, but are much more important for small loans to banks and businesses. The roll out of the Dodd-Frank Act imposed large burdens on these banks that were recognised and rolled back in the “Crapo Bill” of 2018.

Fiscal policy also reacted forcefully to the coronavirus (Box 1.4). Initial policy moves were relatively small and mainly targeted the medical response, but as the scale of the impact on the economy became clearer Congress passed a suite of budgetary acts to shield families and businesses. One-off payments to all families and boosted unemployment insurance payments provided the bulwark in shielding households from the shutdown. Congress has also authorised direct payments to distressed industries, such as airlines. Credits are available for other companies. For small businesses these loans become grants if mainly used to support payrolls as policymakers recognised the importance of keeping workers attached to businesses. In addition, some funds have been directed to support state governments that have come under budgetary strain due to the impact of dealing with the coronavirus at a time when their revenue sources are drying up. Cumulatively these measures will see budget deficits balloon in the short term, and will contribute to raising general government debt by over 20% of GDP in 2020 and 2021.

The federal government has introduced a number of measures in response to the spread of the coronavirus. Initially the acts passed by Congress targeted mainly the medical response but later developed to shield households and businesses from the shock and the impact of the shutdowns being introduced across the country. The main support packages were:

The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act provided early support, including by enhancing telehealth, for the response to the crisis, including through making appropriations for vaccine development, support for state and local governments’ prevention and response efforts, and the purchase of medical supplies.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act targeted to support workers and social assistance. The bill provides for free testing for the coronavirus, 2 weeks paid sick leave (capped) and then additional paid sick leave for workers with children for up to 3 months. Additional resources were devoted to providing food for households with low income. Money was also targeted to support the expected increase of unemployment insurance, which is administered by the states. The bill also increases Medicaid payments to states.

The CARES Act provides support for households and businesses during the crisis. For households the principle measures were: About $301 billion will provide income support for families in the form of direct payments of $1200 for each adult and $500 for children (unless household income is above a threshold) and about $250 billion will boost unemployment insurance payments to $600 per week through July, expand coverage to include the self-employed and gig economy workers, and extend benefits from 26 weeks to 39 weeks. Additionally, the federal government will defer interest and principal payments on federal student loans. The act also supports businesses, cities and states that have been hard hit by the coronavirus. Of this, the CARES Act allows the Treasury to make loans to airlines, air cargo, and national security critical firms of $25 billion, $4 billion, and $17 billion, respectively. The remaining $454 billion will provide equity to the Federal Reserve to establish 13(3) lending facilities for other businesses. Such lending facilities could support around $4 trillion in business loans. Around $350 billion is included to support business interruption loans to small businesses. Principal on these loans that small businesses used for payroll, rent, interest on existing obligations, and utilities for eight weeks will be forgiven if such small business maintain pre-crisis employment levels. Thus, these business interruption loans are effectively grants to keep workers on the payroll during the crisis.

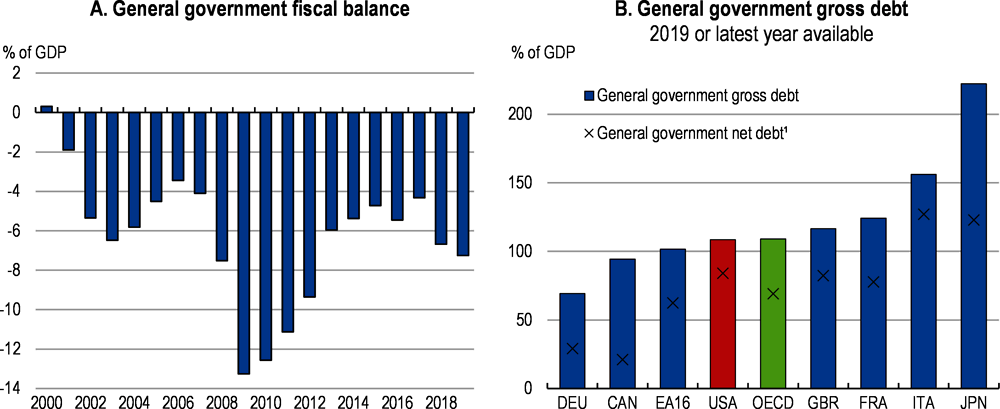

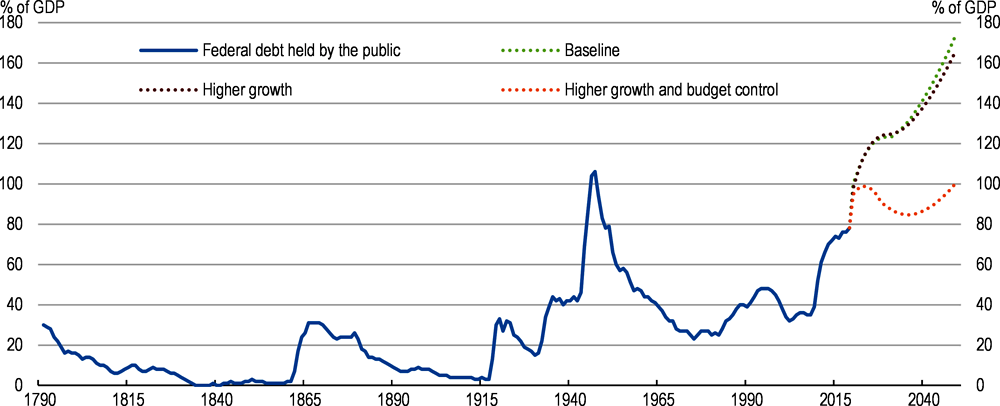

The temporary increase in deficits and rise in debt levels incurred in the coronavirus response will add to the debt stock, but will not fundamentally alter the long-run sustainability challenge. This is largely determined by the underlying growth in spending pressures leading to growing deficits in the absence of corrective action. Even before the crisis the federal government had been running large deficits, raising debt levels (Figure 1.10). However, as interest rates are low and set to remain low for some time, the ability to service interest payments on comparatively large debts is enhanced (Blanchard, 2019[15]). The U.S. dollar’s international reserve currency position reduces concerns about volatile increases in interest rates. A sharp fiscal retrenchment would be counter-productive and as such the temporary provisions in the recent tax reform should not be allowed to expire. Furthermore, automatic stabilisers and additional measures implemented as part of the crisis reaction should be allowed to play out. In the long term, demographic trends will increase spending as a share of GDP. As such, fiscal policy should aim to stabilise debt by gradually reducing budget deficits. From a longer-term perspective, ensuring fiscal sustainability will require measures that will constrain spending growth of some programmes (notably Medicaid, Medicare and Social Security), raise revenue and improve the efficiency of public spending.

Letting the automatic stabilisers operate and boosting productive spending

In the near term, fiscal policy should allow the automatic stabilisers to operate and support aggregate demand as the economy recovers. As with precious recessions, Congress has extended unemployment insurance and increased discretionary spending and should be ready to continue support as the economy reopens. In particular, measures to help workers back into employment and viable firms to weather periods of still subdued demand would support reviving the economy. In addition, fiscal support for state and local governments during a period when their revenues have dried up would counter an unwelcome fiscal contraction just as the economy is beginning to regain its footing.

For future downturns, counter-cyclical policy could be made more potent, which may reduce output losses and see quicker recoveries. One proposal would trigger automatic payments to households when the unemployment rate increased by 0.5 percentage points over the last three months on average relative to the lowest unemployment rate observed over the past year (Sahm, 2019[16]). Breeching this threshold has been a reliable indicator of having entered a recession in the past. That said, fiscal policy reacted with impressive speed to the coronavirus spread with a number of sizeable spending packages.

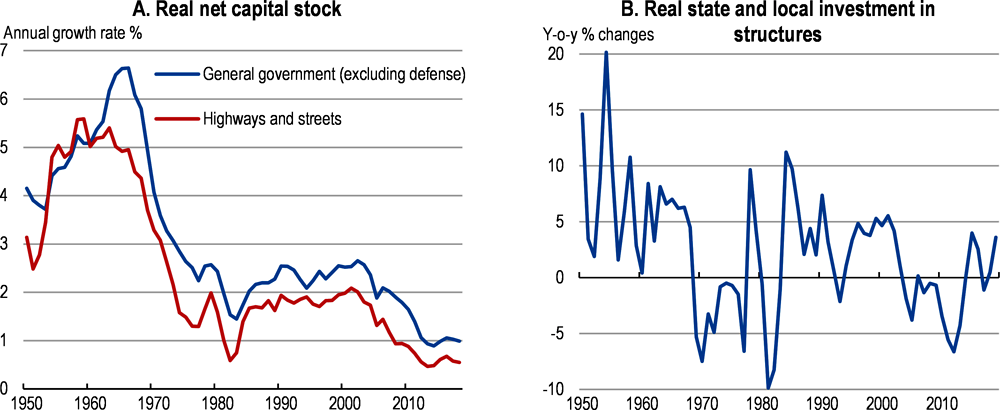

Given the failure of the government capital stock, particularly transportation infrastructure, to keep pace with output growth there is a case for boosting infrastructure investment and badly needed maintenance of existing assets (Figure 1.11). Establishing a pipeline of new projects and necessary maintenance based on cost-benefit analysis, would help ensure value for money and potentially support counter-cyclical policy. For example, if Congress decides to boost investment spending temporarily during a downturn it would be easier to channel spending into higher-return projects. While investment in these assets is often implemented by state and local governments, the federal government plays an important role through grants for highway and mass transit projects, telecommunications and water. For example, the surge in capital stock growth in the 1950s and 1960s is related to the expansion of the inter-state highway system.

The funding for the grants for road transportation and mass transit comes from fuel taxes and is channelled through the Highway Trust Fund or appropriations such as the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (covering 2016-2020). Additional appropriations are needed because tax revenues have repeatedly fallen short of spending, reflecting difficulties in raising the fuel tax rate, which has not changed since 1993. This is compounded by investment becoming increasingly expensive, increasing fuel efficiency and the shift to hydrogen and electric vehicles. There are already around 1 million electric vehicles in the United States and penetration is expected to develop further and reduce fuel tax revenues substantially (Davis and Sallee, 2019[17]). One option is to switch increasingly to user fees for funding (Box 1.5). This is in line with the proposed reforms for inland water transport moving from fuel taxes to user fees that are set to cover investment needs and operation costs. Alternatively, if fuel taxes were raised to reflect inflation since they were introduced the additional revenue raised would be substantial ($25-$50 billion annually depending on the scenario).

The federal authorities face difficulties in investing in specific infrastructure assets. Funding from general revenue is likely to be a limited option given projected discretionary spending. That places an onus on other forms of funding, principally user fees or value capture. This would potentially open the door for innovative financing solutions, such as public-private partnerships, which have been used to some success in states such as Virginia and California and across the OECD. However, options to use public-private partnerships are often limited by budgeting procedures. The bias in the municipal bond market for tax-exempt bonds and restrictions on using bonds to fund projects with private ownership of assets discourages such financing. At the federal level, appropriations may set ceilings that make it difficult for multiyear projects to remain under (Section 302(b) allocations) and limits on long-term contracting can reduce opportunities to experiment with different financing mechanisms. In order to tap into different delivery options the federal government should experiment with states on ways to relax rules for specific infrastructure projects. On the bases of ex post evaluation, best practice cementing new ways to budget for these types of investment projects should be disseminated.

It needs to change to more user fees and taking into account externalities

The present system is ill-adapted to meet trends in transport use. The major charge levied on drivers is the gasoline tax. At the federal level this is only 18 cents per gallon and while the receipts have been earmarked for interstate highways, infrastructure projects and mass transit, the amounts collected have been insufficient to meet spending needs. The switch to electric cars, hydrogen technology, and better fuel efficiency further undermines the tax base.

There are several externalities from driving include pavement damage, accidents, congestion, local air pollution and the emission of long-range transboundary pollutants and greenhouse gases. At present drivers pay a fraction of the wider costs they impose. Given the different natures of the externalities a combination of approaches is likely optimal. For the purposes of infrastructure provision, a switch towards user fees that better account for pavement damage and congestion. In addition user fees would reduce demand and signal more accurately where new capacity is needed, thereby ensuring the efficiency of public investment.

A number of states (California, Illinois, Oregon and Washington) are piloting programmes to introduce distance-based charging. Elsewhere in the OECD, some countries have already moved to distance based tolling for heavy goods vehicles and current technology is approaching the stage when this can approach can be extended to the passenger car fleet.

As an alternative, several states already implement road use taxes (Kentucky, New Mexico, New York and Oregon). Expanding this approach to the federal level could yield revenues in the range of $1.7-$2.7 billion if levied at the rate of 1 cent per mile on commercial trucks (CBO, 2019). However, enforcement or upfront capital costs would be larger than the current reliance on fuel taxation. Without enforcement evasion can be an important problem (around 50% in some cases) and has led states to repeal distance-based charges in the past. On the positive side, a distance based tax that varied with weight per axel could reduce pavement damage substantially. There would also be ancillary positive impacts reducing congestion if fees varied by time and place.

Growing spending pressures

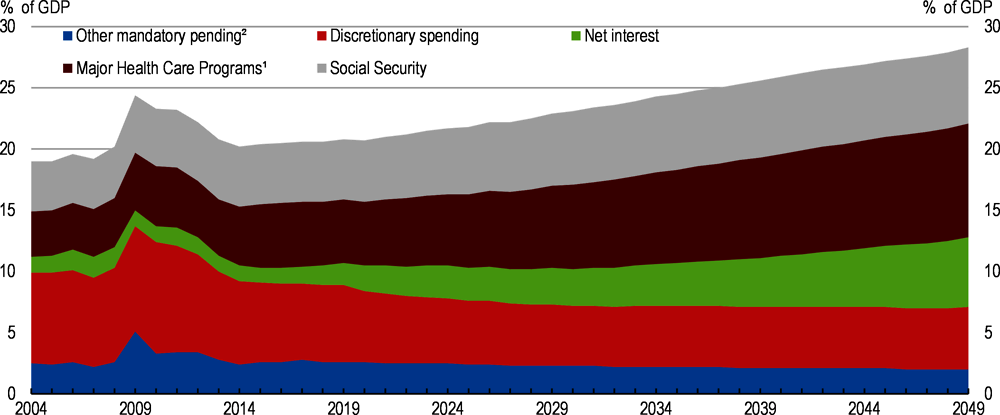

The spending pressure on federal budget’s long-term sustainability is largely driven by health and social security, which together account for three-quarters of mandatory spending (Figure 1.12). Mandatory spending currently accounts for around 13% of GDP and is expected to rise by another 2 percentage points over the next decade. The upward pressure on spending largely comes from rising health care costs, ageing - as more people enter retirement - and rising interest payments as the debt burden continues to mount. Without corrective action, fiscal policy is unstainable in the long term (Box 1.6).

The United States spends a substantially larger share of income on health care than other OECD countries (over 16% of GDP in the United States against an OECD average of under 9%). The public sector is responsible for over 40% spending on health, with compulsory insurance accounting for about another one-third of spending. The public sector portion has gradually expanded over time (Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans’ Affairs). Reform options are complicated as the system has evolved with employers and health insurance companies playing an important role. Proposals for further expansion and Medicare-For-All would come at a substantial cost and need radical changes to funding, particularly if current levels of provision were offered (CBO, 2019[18]). An approach adopted in other OECD countries would be to provide a less generous basic package and allow households wanting more health care coverage to top up using private plans. An alternative approach would be using greater means-testing in accessing healthcare.

Large differences in health spending exist not only across countries, but also between states. Various estimates suggest opportunities to curb wasteful spending which may account for as much as 30% or $750 billion of spending in 2009. (Smith et al., 2013[19]). Benchmarking states suggests considerable savings could be made by reducing the use of emergency departments, ensuring medication is taken as intended, reducing avoidable hospitalisations and unnecessary procedures and improving end-of-life care (Linder et al., 2018[20]). The administration has acted to accelerate the approval process at the FDA to promote greater competition in the pharmaceutical market, which has contributed to the recent decline of prescription drug price inflation (Council of Economic Advisers, 2019[21]). In light of the coronavirus, reforms to health spending should ensure that they do not undermine the health sector’s capacity to respond to medical needs. In addition, it appears that large-scale testing capacity is a prerequisite for introducing more targeted measures and avoid the shuttering of the economy when a pandemic hits. Increased availability of personal protective equipment for health professionals and the population at large should help to reduce the transmission of a virus. Beyond this, improved governance and better co-ordination while reducing some of the regulatory barriers that initially hampered testing would enhance the ability of the health sector to respond effectively to a future health crisis.

There is scope to make savings in social security spending that would grow over time by increasing the progressivity of the system. The CBO estimates that modest changes to the formula used could reduce social security payments by 0.2 percentage points of GDP, by reducing benefit levels for higher earners (CBO, 2018[22]). More aggressive changes would have larger impacts, although such changes would weaken the link between social security benefits and earnings. Alternative approaches to ensure sustainability include changing the price index used to calculate benefits and increasing further the early and full retirement ages. Finally, raising the cap on earnings subject to contributions or the tax rate would raise additional revenues (Burtless, 2019[23]).

Discretionary spending – that is, spending decided annually in the budget process - currently accounts for 30% of federal outlays. Discretionary spending has been trending down to around 6% of GDP. Defence spending now accounts for around one half of this category. Government projections cap discretionary spending growth which will reduce it to historically low levels (5.4% of GDP). This type of spending includes transportation and education outlays and a continued squeeze on these programmes without rethinking how they are funded or their objectives may be neither realistic nor sustainable. For example, underfunding maintenance can provoke large capital spending when infrastructure assets fail. In addition, discretionary spending can play an important role in macroeconomic stabilisation during downturns (as seen around 2009).

Given current policies the Congressional Budget Office projects that federal debt held by the public will rise substantially over the coming decades (Figure 1.12). To explore options to restore long-run sustainability, a number of mechanical simulations were conducted using reforms recommended in this Survey. Measures intended to boost GDP growth (increasing labour supply and productivity growth) raise the level of nominal GDP by 4% by 2030 and almost 10% in 2050 slowing debt accumulation. However, the scale of the challenge requires additional action to bring the budget deficit under control.

A mixture of base-broadening measures and addressing environmental externalities to increase revenue and indexation measures to constrain spending has the potential (other things being equal) to bring debt levels down. The effort would be substantial amounting to a 2½ percentage point of GDP reduction in the deficit by 2030. Even then, underlying spending pressures are still mounting due to demographic and excess health spending cost pressures. Ageing accounts for around half of the growth in spending in these projections, with the remaining increases due to rising net interest payments and excess cost growth in health spending, more than offsetting falls in discretionary spending.

The impact of the coronavirus on debt sustainability is relatively modest in comparison with the pressures emanating from pensions and health spending, but losses in the private sector (such as from contingent liabilities) could materialise quickly and push up debt levels even further.

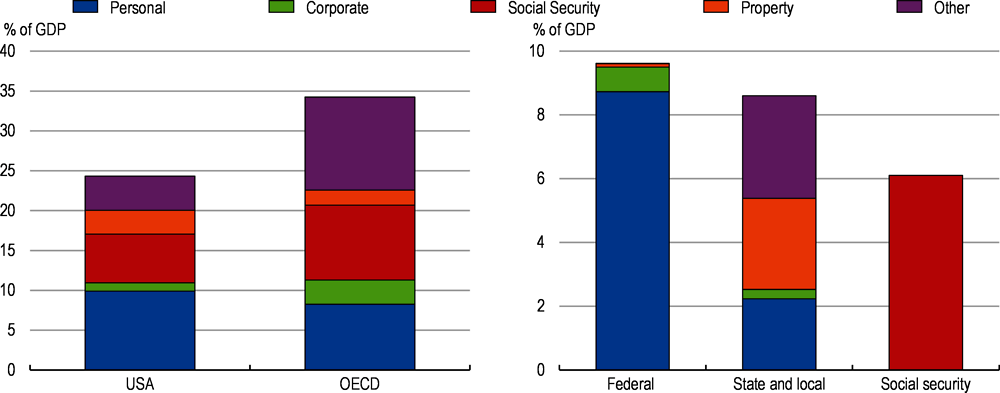

Raising additional revenues

Tax revenues for all levels of government account for almost 25% of GDP, and considerably less than the total tax receipts on average in the OECD (Figure 1.14). This is principally due to lower revenues from sales taxes rather than a value added tax, which is levied in other OECD countries. Combined personal and corporate income taxes are around the level elsewhere in the OECD and taxes on property are relatively high. The federal government is almost completely reliant on personal income tax revenues. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 cut these tax rates, which has seen revenue decline, but the personal income tax structure remains relatively progressive in comparison with other OECD countries. However, changes to personal tax rates and some of the modifications for corporate taxation were temporary (in part to ensure meeting budget scoring conventions). Historically, Congress has often extended such taxes or made them permanent to avoid abrupt fiscal shocks.

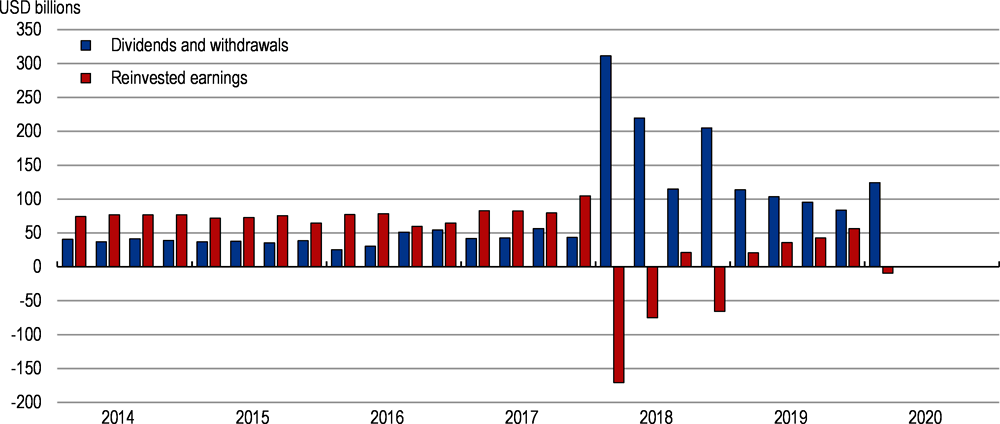

The full implications of the tax reform have yet to play out, but some measures appear to have brought improvements. Changes to remove incentives for multinational companies to park earnings abroad have seen more profits being reported (Figure 1.15). However, growing pressure on public finances will likely require raising more tax revenues. In order to minimise the negative impact on growth, fully reversing the tax reforms and raising marginal tax rates on those taxes most inimical to growth, such as income taxes, should be avoided (Akgun, Cournède and Fournier, 2017[24]). Reversing the improved investment incentives for businesses would weaken long-term prospects for the economy.

There are opportunities to increase revenue without raising marginal tax rates. Closing loopholes and broadening tax bases for a number of taxes could raise revenue.

Adjusting the step up provision that currently bases capital gains on inherited assets on the difference from the value on transfer to the original purchase price. This would also reduce incentives for tax planning and increase incentives for productive investment.

Reforming the carried interest provision for pass-through business could increase revenue modestly ($1.5 billion annually if treated as labour income) and treat this income source similarly to other performance-based compensation. However, to preserve intangible capital investment some carried forward provision may need to be retained.

Taxing pass-through owners on the basis of the Self-Employment Contributions Act rather than the Federal Insurance Contribution Act. This would raise an addition $20 billion a year and treat different types of owners equally. It would also remove incentives to use different business forms for tax planning and help simplify the tax code.

Complementary to closing loopholes, recent evaluations of tax policy implementation suggests sizeable tax underpayment. Increasing inspection and investment in modern technology to identify suspicious returns could potentially yield additional increases in tax payments (Sarin and Summers, 2019[25]).

Another means to raise revenue is to reduce or remove tax expenditures. The 2017 tax reform capped the mortgage interest rate deduction, but reforms could go further and eliminate it entirely. These tax deductions and the state and local tax deduction is partly capitalised into housing values and is regressive in that high-income filers benefit the most from these tax expenditures. The federal government also foregoes significant tax revenue through the support of private health care.

Introducing a wealth tax has been advocated to cover increased government spending and make the tax system highly progressive (Saez, Berkeley and Zucman, 2019[26]). At present only six OECD countries implement a wealth tax raising relatively little revenue, although it does rise to 1% of GDP in Switzerland (OECD, 2018[27]). Administration and compliance issues, such as exemptions progressively undermining the tax base, have ultimately led countries to repeal recurrent taxes on net wealth. While a case can be made for a net wealth tax, effective taxation of capital income at the individual level as well as recurrent taxes on immovable and property and estate and gift taxes are likely a more robust approach to raising revenues sustainably.

Finally, if additional tax revenue is needed introducing a federal value added tax would be amongst the least distortionary means, but the political economy surrounding this tax makes legislation difficult. Environmental taxes and taxes that address externalities are options for new taxes that could raise revenues and well-being. For example, accounting for some of the negative effects of driving by increasing the fuel tax and thereafter indexing it to inflation could make a sizeable contribution to revenues. Increasing the excise tax on tobacco could produce a modest revenue gain while improving health (Box 1.7).

Ensuring competition

Overall the business environment is competitive internationally. The United States is normally placed amongst the highest in the competitiveness rankings produced by the World Bank and World Economic Forum (Schwab, 2019[28]). While performance is good overall there are areas of relative weakness. For example, although the United States is ranked as the 6th best in the world for the overall ease of doing business ,the rank drops to 55th for the ease of opening a new business and to 64th for getting electricity (World Bank, 2019[29]). In the wake of the coronavirus shock, ensuring competition is likely to be important in facilitating the restructuring of the economy by supporting the entry of new firms and preventing the loss of existing firms giving rise to anti-competitive behaviour by the remaining incumbents.

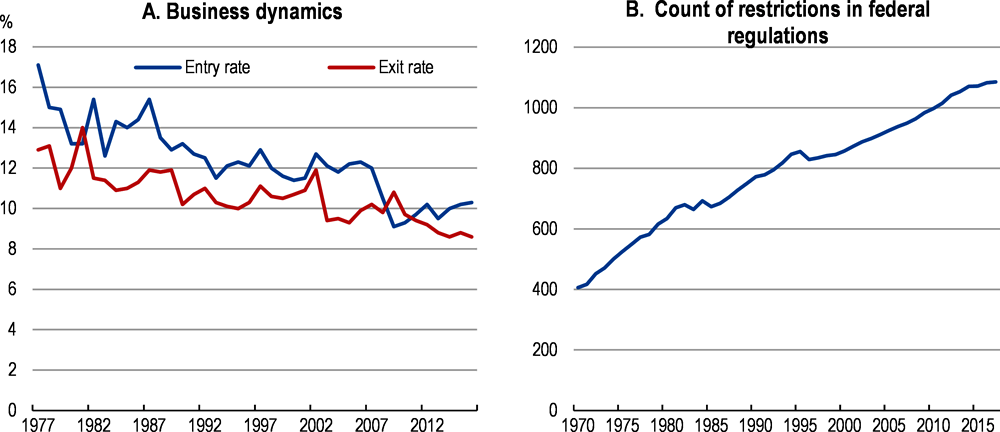

The decline in new firms entering the market is a cause for concern, given that they are often important for spurring productivity growth (Alon et al., 2018[30]). One explanation for the slowdown in firm entry is increased regulation (and greater lobbying) creating barriers to entry (Figure 1.16). Regulation appears to have become more important in deterring small firms. Regulation (measured by the number of restrictions contained in federal regulation) roughly doubled since the mid-1970s and empirical evidence suggests this could account for a 2.5% decrease in firm creation rate (which fell by around 7% during the same period) (Gutiérrez and Philippon, 2019[31]). Regulation at the state and local level will also weigh on entrepreneur’s decisions. The administration is beginning to address the growing burden of regulation on the business environment. Regulatory agencies are now required to evaluate the overall costs of their actions are placing on the economy, by introducing regulatory cost caps. This effort also requires regulatory agencies to reduce at least two regulations for the introduction of a new regulatory burden. This has helped curb – and even led to a shrinkage in – the restrictions embodied in federal regulations.

Competition policy has an important role to ensure that the economy remains vibrant and preserves the incentives for innovation and productivity growth. Examining competition policy in light of the new modes of business in technology sectors in particular was recommended in the past two OECD Economic Surveys The large technology-dominated markets (due to the network characteristics) may present special cause for concern.. A trade-off needs to be struck between the advantages - such as services being offered for free to consumers - and the challenges to new firms in overcoming network effects. In addition, the network characteristics may give advantages to incumbents that can facilitate entry into new markets, make markets less contestable and affect competition by making it more difficult for new entrants to attain viability. The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission have launched inquires into the large technology companies (Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon).

A number of authors have pointed to evidence consistent with the economy becoming less competitive, but empirical research on whether the economy is becoming more or less competitive is active but inconclusive (Syverson, 2019[32]). Evidences from specific markets suggests rising concentration has had detrimental outcomes. For example, hospital concentration has been linked with higher prices and lower quality (Gaynor, Martin and Town, 2012[33]). However, it is harder to assess whether similar effects hold across the economy. For example, dramatic rises in mark-ups suggesting rising market power have been questioned and subsequent work found smaller increases (Hall, 2018[34]) (De Loecker et al., 2019[35]) (Demirer, 2019[36]). Aggregate data suggesting increasing concentration or mark ups can coexist with healthy competition. In the retail sector large firms, such as Amazon and Walmart, have attained important positions in the national market. However, concentration at the regional level has not increased, suggesting that localised markets are still competitive and benefitting the consumer (Rossi-Hansberg, Sarte and Trachter, 2019[37]). Further empirical evidence suggests that concentration rising in sectors where productivity growth is strongest. In this light, concentration ,ay reflect the effective working of the market and winner–takes-most outcomes (Autor et al., 2017[38]).

A possible challenge in markets like healthcare and telecoms and media markets concerns vertical mergers, which are harder to bring under existing antitrust policy. As a general matter, vertical mergers should be less problematic than horizontal mergers, as they can potentially generate substantial benefits and reduce costs. Yet they also have the potential to be anticompetitive. For example, in the evolving telecom and media market, vertical mergers between content providers and telecom firms may give rise to problems of input foreclosure (Shapiro, 2019[39]). However, ultimately the effect of any particular vertical merger is an empirical matter.

Securing the gains from trade

Trade volumes had gradually picked up into early 2018, but have become volatile thereafter as trade policy dramatically increased in importance and then the differential impact of the coronavirus across trading partners. Imports and exports have spiked and then collapsed as trade measures have been introduced. In particular, tariffs levied on imports from China have risen from an average of 3.1% in early 2018 to 19.3% in late 2019 with tariffs covered by these measures accounting for almost two-thirds of Chinese imports (Bown, 2019[40])), but subsequently some were relaxed so that firms could import inputs needed for the coronavirus response. The impact of the coronavirus shock is likely to have enduring impacts on trade as supply chains are made more resilient.

Trade policy has also reacted to the outcome of long-standing disputes that have worked through multilateral institutions (such as the WTO dispute over support in the aerospace industry) to new measures and potential threats of new measures. In many cases, these measures have provoked counter-measures affecting U.S. exports.

The administration’s aim in introducing different measures since early 2018 has been to address shortcomings in existing trade rules. In particular, disputes have arisen due to concerns about intellectual property rights, non-tariff barriers to access certain markets (such as forced technology transfer), and the lack of a level playing field through distorted public procurement procedures and restrictions on foreign directed investment. There is cross-country support for this agenda, but disagreement on how best to achieve the goals.

The administration has negotiated a new trade agreement with Canada and Mexico (USMCA), which was passed by Congress in late 2019. This agreement modernises aspects - such as e-commerce - of the former NAFTA agreement as well as aiming to promote domestic manufacturing, though rules of origin requirements. Discussion with other countries have been largely on a bi-lateral basis. Tariff increases or other trade measures have been rescinded or not implemented when these discussions reached agreement, often with a commitment to increase imports from the United States. In particular, an agreement with China in January 2020 marked a pause in the escalation of this dispute. A greater reliance on and a more effective a multilateral approach would require finding solutions to issues that the current constellation of organisations and agreements are ill-adapted to address (Bown and Hillman, 2019[41]). The administration also needs to find a way to unwind trade measures, which can be long lasting. The US tariff on light trucks was introduced in 1964, in a dispute over poultry exports, and remains in place.

Empirical evidence suggests that the short-run impact of the tariffs has raised prices for domestic consumers, implying welfare losses of around $50 billion which needs to be weighed against the costs of inaction (Fajgelbaum et al., 2019[42]). Sectors and regions most exposed to retaliatory tariffs are also suffering. Empirical research suggests that regions most exposed to retaliatory tariffs areas experienced drops in consumption, as proxied by new car sales, of nearly 4%, which is likely driven by falls in relative employment of 0.7% rising to 1.7% for goods-producing employment (Waugh, 2019[43]).

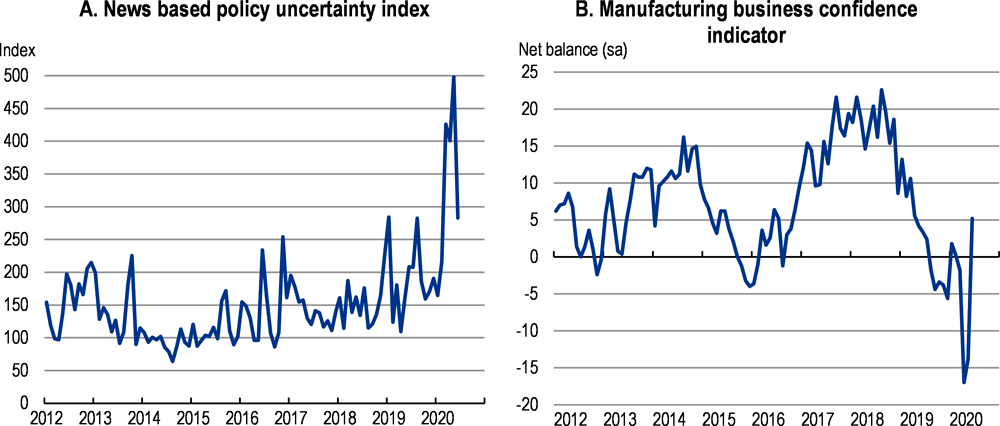

The introduction of tariff measures and retaliatory actions has accompanied increases of trade-related uncertainty (Figure 1.17). This has likely depressed business confidence and investment as companies wait to see the repercussions before determining how they will be affected and whether they need to reshape their supply chains. One study estimates that trade policy uncertainty may have reduced investment by more than one percentage point (Caldara et al., 2019[44]). To the extent that changes in trading relationships reflect investment decisions to protect supply chains or a pull-back from competition this will contribute to de-globalisation and as a negative supply shock will tend to depress long-run living standards.

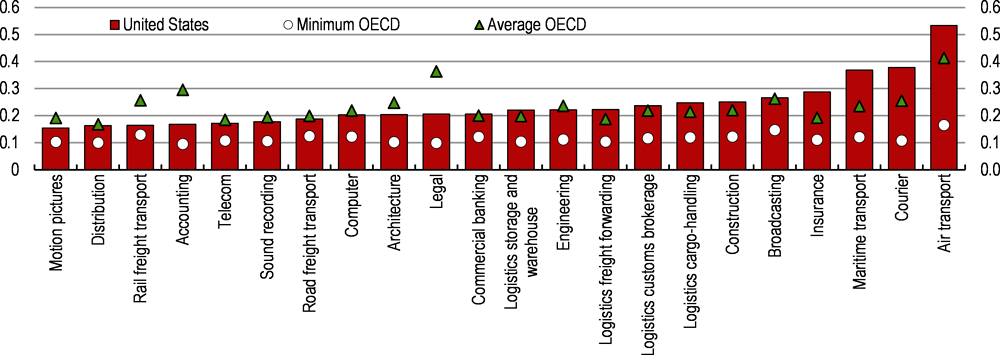

So far, much of the focus has been on trade in goods. However, the composition of exports is increasingly shifting towards services and they already account for over half of gross exports and 70% of the value added exported. The importance of this type of trade is unlikely to diminish in the future and is particularly susceptible to regulatory barriers. At present, the regulatory environment for services trade is relatively open in 18 out of the 22 sectors measured by the OECD, including distribution services, rail freight transport services and professional services. On the other hand, services trade restrictions are particularly pronounced in maritime transport, postal/courier services and air transport services (Figure 1.18). The lifting of the Jones Act in the wake of hurricanes highlights some of the costs regulatory barriers impose on the U.S. economy (Box 1.8). Against this background, making further progress in reducing trade impediments would be beneficial (Box 1.9).

The Jones Act was introduced in 1920 to ensure a merchant marine fleet that could also serve as a naval reserve. One requirement is the restriction that goods shipped between U.S. ports are transported by U.S. built, owned and operated vessels. Over time, rising costs of building new vessels within the United States relative to other countries, has seen the U.S. fleet age and the shipbuilding industry increasingly concentrating on producing tug boats and barges. These are relatively small vessels and mainly ply their trade along the Mississippi river and not along coastal ports or between the contiguous states and Alaska, Guam, Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

Through the restrictions on which ships can operate for domestic cabotage, one effect of the Jones Act is higher transportation costs. Higher costs are particularly severe for the non-contiguous areas as they are more reliant on shipping (Grennes, 2017[45]). The restrictions and high costs have seen goods diverted through Canada, for example, before being exported by ship back to the United States. In the wake of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, the Jones Act is often waived to allow the timely delivery of emergency supplies. This highlights that the Jones Act has failed to preserve a sizeable merchant marine fleet at the expense of higher prices and trade diversion.

Services trade covers activities such as transportation, telecommunications, financial services and other professional services. For these industries regulations present important barriers to service providers seeking to enter new markets. Considerable regulatory differences exist across countries, with regulations set by national authorities or professional bodies. In some cases the complexity of regulation can inhibit trade almost entirely. Reducing these barriers involves domestic policy reforms (such as lifting restrictions on foreign investments in particular sectors) and also international co-operation. International co-operation would reduce trade costs by promoting transparency and reducing uncertainty, including through locking in regulatory co-operation in trade agreements.

The policy indicators underlying the Services Trade Restrictiveness Indicator can be mapped to trade costs (Benz, 2020). For the United States, the largest barriers to services trade in relation to the country with the lowest trade costs are in air transport, courier services and insurance. In these sectors halving the trade costs relative to the best performer would reduce trade costs by around one fifth.

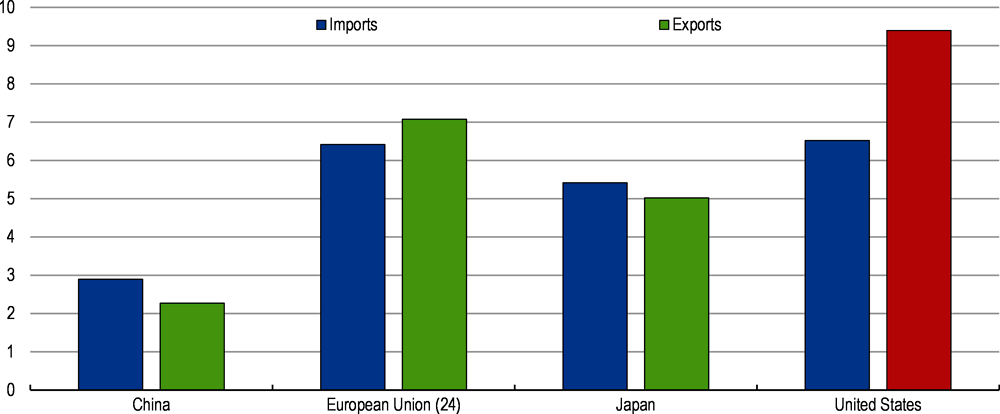

To examine potential gains, simulations using the OECD METRO model assess the impact on trade flows from reducing services trade costs to those observed amongst members of the European Economic Area. This sets a level of ambition, which is achievable but required sustained negotiations to ensure market access across various regulatory regimes. If similar agreements were reached across G20 countries the boost to trade in the medium term would be substantial for all economies (Figure 1.19). For the United States, imports and exports of goods and services would rise in the medium term by around 6% and 10%, respectively. The wider impact on the economy would lower prices and increase variety and efficiency and boost to the level of US GDP of around 1½ percentage points. By contrast, efforts to eliminate nearly all tariff barriers on trade in goods were estimated using the OECD METRO model to yield gains of around 3% for imports and exports in the medium term (OECD. 2018).

Addressing corruption, money laundering and financial crimes

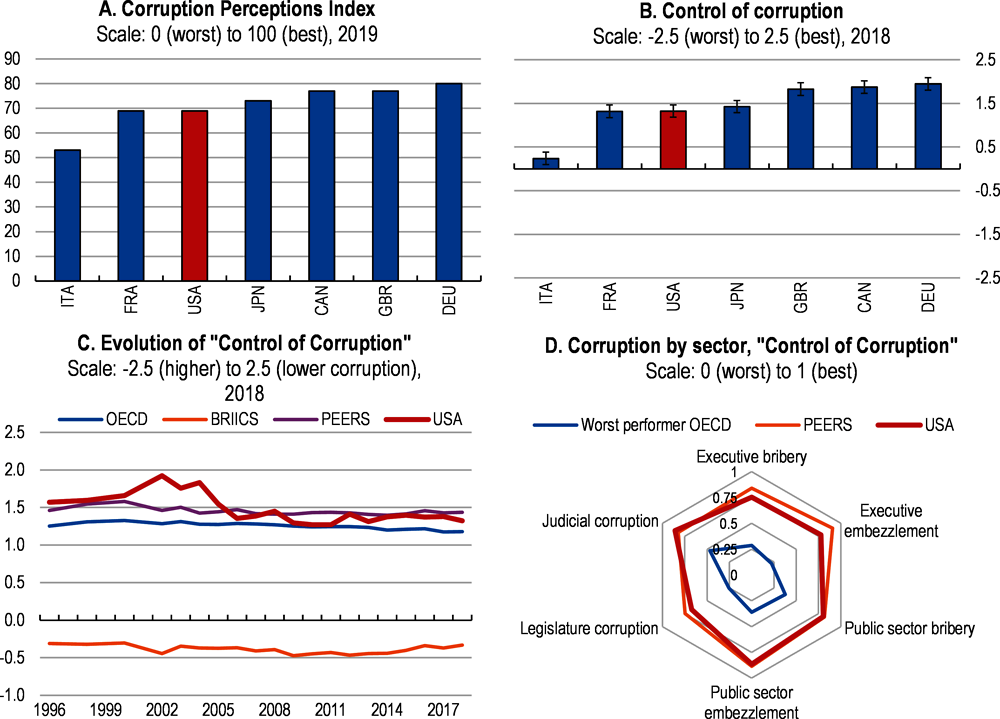

The perception of corruption is low, but remains somewhat weaker than in most other G7 counties (Figure 1.20). The control of corruption indicator is also relatively weak, but has been improving over the past 20 years. The main area of weakness is control of executive embezzlement. Within the public sector evidence suggests that corruption is declining. The public integrity section of the Department of Justice oversees efforts to combat corruption by elected and appointed officials at all levels of government as well as the private citizens involved. The charges levied against individuals peaked in 2008 at 1304 and have subsequently declined, by around one half for government officials. Conviction rates are around 90% for government officials and 75% for private individuals.

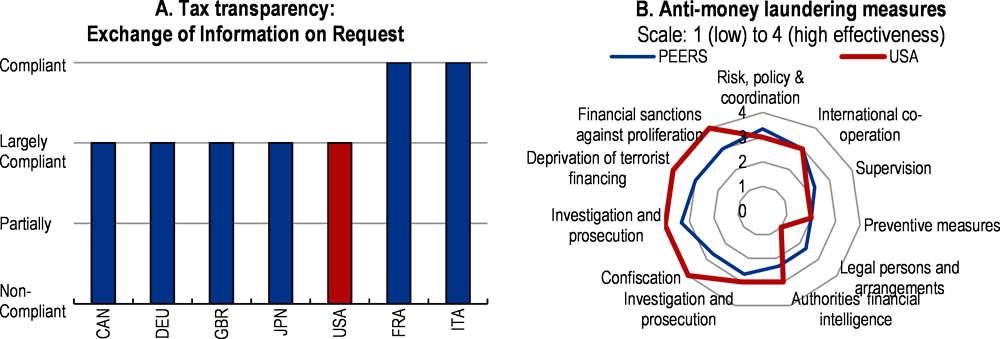

The United States attracts money laundering activities by virtue of its economic and financial importance in the global economy. In terms of tax transparency, which reduces the scope for tax evasion, the United States is largely compliant and similar to other G7 countries and with respect to the effectiveness of anti-money laundering measures, the United States performs better or at least equivalent to other G7 countries. Concerning the Technical Compliance of anti-money laundering measures, however, the Financial Action Task Force judges the United States non-compliant in four areas: transparency and beneficial ownership of legal persons, customer due diligence, other measures and regulation and supervision of designated non-financial businesses and progressions. The Department of Treasury and the FBI provide information to financial market participants about how the financial markets are being used to channel illicit proceeds out of foreign countries. Lawmakers should finalise the enactment of the Illicit Cash Act and the Corporate Transparency Act which both have already passed the House of Representatives with bipartisan support and are awaiting approval by the Senate; both acts together would substantially boost the United States’ efforts to combat money laundering.

The impact of the coronavirus is likely to undo some of the achievements of the long economic expansion. Not only had the employment to population rate fallen to its lowest level ever recorded prime age labour force participation has also dropped precipitously. The prime age participation rate also dropped markedly during the last recession and have only just returned to pre-crisis rates (Figure 1.22). That recovery in participation coupled with a gradual increase in earnings, had become stronger at the bottom of the wage distribution over time and had lifted household income. As a result, poverty was beginning to come down and the sustained rise in income inequality has halted (Figure 1.23). The very strong labour market had successfully retained or brought in workers who are often on the margins. For example, disability rolls had fallen as the inflow of eligible workers into disability insurance has slowed.

The impacts of the coronavirus and shelter-in-place orders have dealt a sharp blow to this progress. Labour force participation has slumped to around 60%, affecting those with traditionally weaker attachment to the labour force to a greater extent. Thus, while a robust recovery from the current downturn will limit the damage to the labour market by drawing back in workers on the margins, additional effort will be needed to make sure opportunities are again widely shared. Action to improve active labour market policies - such as job placement services, support for geographical mobility and retraining or reskilling opportunities - would help workers displaced by the coronavirus shock (OECD, 2018). In addition, continuing efforts to provide apprenticeships and training to young workers just entering the labour force would help avoid the scarring effects from failing to make a successful transition from school to work in a difficult labour market.

Despite progress, inequality of opportunity remains a concern. Average income levels between racial and ethnic groups have not narrowed, resulting in a worrying persistence of inequalities (Box 1.10). Intergenerational income mobility is low by comparison with other countries. For example, existing patterns of income persistence suggest that it would take 5 generations to move from the lowest income decline to reach average income, which is somewhat longer than average for the OECD (OECD, 2018[46]). Furthermore, recent work suggests that this is a place-based phenomenon with a strong racial and ethnic component in outcomes (Chetty et al., 2018[47]). In this context, working to overcome barriers to opportunity through education and health as well as moving to opportunity could help improve well-being.

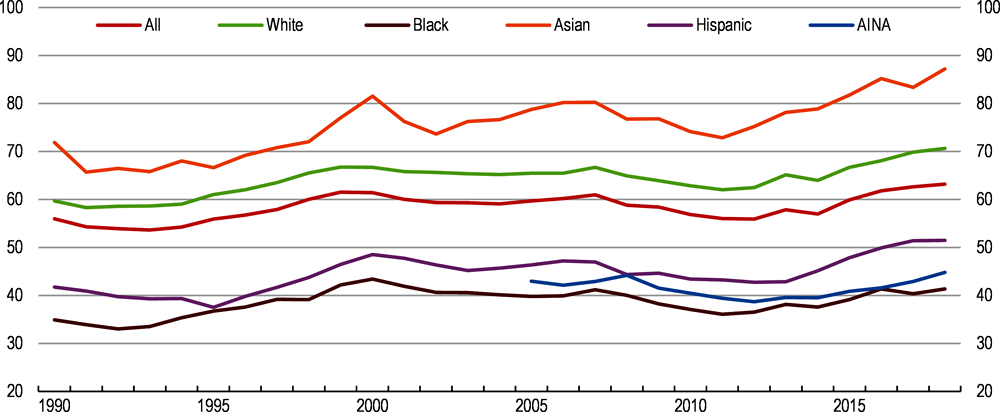

Inequalities appear persistent for some groups, notwithstanding progress in educational attainment. household income for Black and African American and American Indian and Native Americans (AINA) remains stuck below median income for all American households (Figure 1.24). By contrast, the gap for Hispanic households appears to be narrowing somewhat. These gaps remain after controlling for other factors. Furthermore relative income convergence appears to have slowed after the Great Recession (Akee, Jones and Porter, 2019[48]).

Reducing regulatory burdens in the housing and labour markets

In the housing and labour market regulatory barriers to mobility across the country and between jobs are impediments to workers getting access to employment and making the transition to better and more productive jobs and as a result depress output (Box 1.11). To the extent that the coronavirus changes patterns of economic activity, these also create barriers to a strong recovery. Notably, restrictions on land use and housing can prevent cities from growing (Hsieh and Moretti, 2019[49]). This is important as the economic geography of the United States is changing with the population and employment shifting west and south. The inability of some cities to grow in population size or effectively integrate surrounding regions by strengthening economic links limits potential returns to scale and hinders workers finding jobs including by moving from declining to better performing areas. In addition, urban sprawl can reduce accessibility of jobs to workers. The federal government, states and some cities run “moving to opportunity” schemes that provide assistance to help families to move for improving job and education opportunities. The health risks revealed by the coronavirus pandemic will alter some of this calculus as the public preferences for high density cities may diminish and public policies will need to balance making cities resilient to contagion and productivity gains.

One factor behind barriers to moving is policy fragmentation, which for housing is more pronounced than many other OECD countries. Many decisions are made at the local level and do not consider the broader implications of housing, land use and transport planning. Overly restrictive and poorly integrated policy can affect timely and co-ordinated supply of infrastructure and give rise to sprawl, which is more prevalent in the United States than in other OECD countries. As a result, workers find it difficult to move jobs. Furthermore, even within cities, workers may find it extremely difficult to find work within a reasonable commuting distance, especially if they rely on mass transit.

Occupational licensing has become more prevalent now covering around one quarter of the labour force and creating barriers to raising efficiency through better matches and implications for inequality. New evidence from occupation licensing suggests that the effects can be large (Box 1.10). Furthermore, the operation of occupational licensing can create obstacles for particular groups of the population. The coronavirus pandemic revealed the barriers that they can create are detrimental requiring action to reduce their impact. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued a national emergency order to permit doctors to treat patients in states where they don’t have a licence to practice. In addition, several states have decided to wave occupational licensing restrictions or issue temporary licences for medical personnel.

Occupational licensing introduces sand in the process of workers and firms finding good matches, inhibiting moves to new jobs and depressing labour market fluidity. The types of restrictions imposed can have different effects with most depressing job mobility. On the other hand there is some evidence that educational requirements appear to support mobility by increasing worker skills. Moreover, interstate job-to-job mobility tends to be lower towards states with more extensive and stricter licensing regulation. At present, initiatives such as Arizona accepting licences issued by other states work towards reducing the regulatory burden. However, even this relaxation still blocks the trade in services across state boundaries.

Non-compete clause in employment contracts, which create restrictions on workers moving to competitors, have become more prevalent over time and appear to cover around one quarter of the labour force. While there are reasons for such clauses, such as protecting market sensitive information being revealed to competitors, they have been applied in anti-competitive ways, which also has a negative impact on labour market fluidity. Comparative data for other OECD countries reveals that the diversity of enforcement across the US (spanning from very restrictive in Florida to unenforced in California) is similar to the differences across the OECD (Portugal to Mexico).

Reforms proposed in the Survey are quantified in the table below. Some of the estimates reported are based on empirical relationships between past structural reforms and productivity, employment and investment. These relationships allow the potential impact of structural reforms to be gauged. The effects are based on estimates, not necessarily reflecting the particular institutional settings of the United States. This includes how representative changes in policies under the control of the states are for the whole country. As such, these quantifications are illustrative.

Reducing inequalities in education and health

Education provides a primary means of improving opportunity and policy has succeeded in raising participation and attainment. Since 2000, high school completion rates and measures of educational attainment rose, especially for Black and African Americans and Hispanic, although they still lag white and Asian students (Brey, 2018[50]). At college level, undergraduate enrolment more than doubled since 2000, with participation rates rising quickly, particularly for Hispanic young adults, and closing the gap with white and Asian students. Another change that has gradually emerged with the latest cohorts is women now more likely to have a college education than men (Coile and Duggan, 2019[51]).

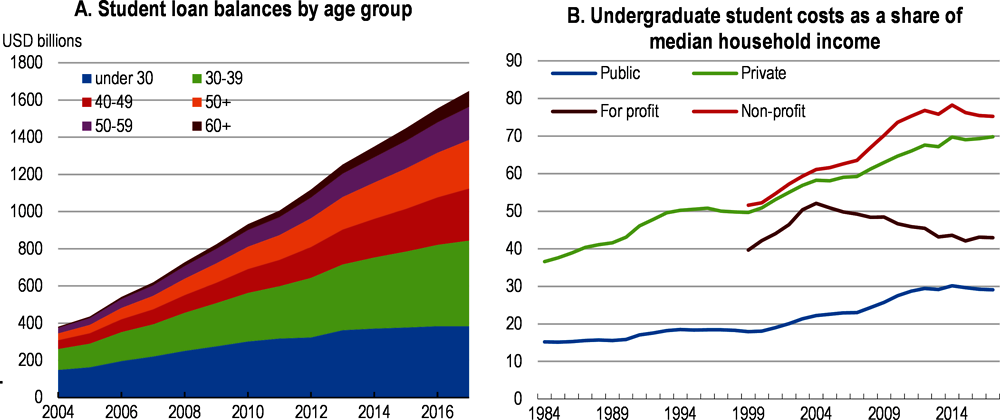

The growth in college education has led to the growth of student debt, which is a concern for students coming from low-income backgrounds. Investing in education remains an important means of improving opportunities and wellbeing. For example, higher levels of educational attainment are correlated with higher earnings, though there are differences with Asian and white generally earning more than Black and Hispanic young adults (Brey, 2018[50]). Students from lower income backgrounds have higher delinquency rates. Whether these problems is concentrated by race or ethnicity are difficult to determine (the design of student loan programmes prevents collecting such information). That said, student debt borrowing is rising faster in areas with a higher Black and African American shares of the population. Furthermore, the average debt levels to average income ratios in these areas is very high and the default rates (18% of borrowers) are double those in majority-white areas. A legacy of student debt delinquency can create problems for borrowers in the future (Box 1.12).

After a sustained increase in costs of attending college, more recent information suggests that this has plateaued, in relation to median household income (Figure 1.25). The amount of borrowing amongst younger cohorts appears to be stabilising and students are switching away from for-profit schools that had often been associated with poorer outcomes and greater student debt problems. Many students face difficulties due to the costs, resulting in growing student debt burdens which now represent the second largest component of household debt after mortgages. Furthermore, large numbers have defaulted on Federal Direct Loans or Federal Family Education Loans (25 and 40 percent of borrowers in repayment, respectively) (Di and Edmiston, 2017[52]). The use of income-contingent loans is relatively undeveloped. Student debt is associated with a number of poor outcomes (Goodman et al., 2018[53]), including delaying household formation and first house purchase, slowing new firm formation which often relies on personal debt to finance and disqualifying borrowers from access to additional credit when they are in delinquency and default

Part of the increase in costs since the Great Recession has been a retrenchment in state funding for public universities (Bound et al., 2019[54]). However, partly offsetting this merit aid programmes have been implemented in 27 states, usually offering reduced in-state tuition fees to qualifying students. Recent findings suggest these programmes do not induce additional students, but help reduce the debt burden of the students and may lead to lower delinquency rates, particularly amongst low-income and minority groups (Chakrabarti, Nober and van der Klaauw, 2019[55]). As a result, merit aid helps improves opportunity for disadvantaged groups but expanding such programmes may not reach those that would benefit most from raising their educational attainment. For these individuals, more targeted interventions may be more appropriate. Debt forgiveness would be another approach to reducing the longer-term burdens on individuals, but this comes at substantial fiscal cost to the federal budget.

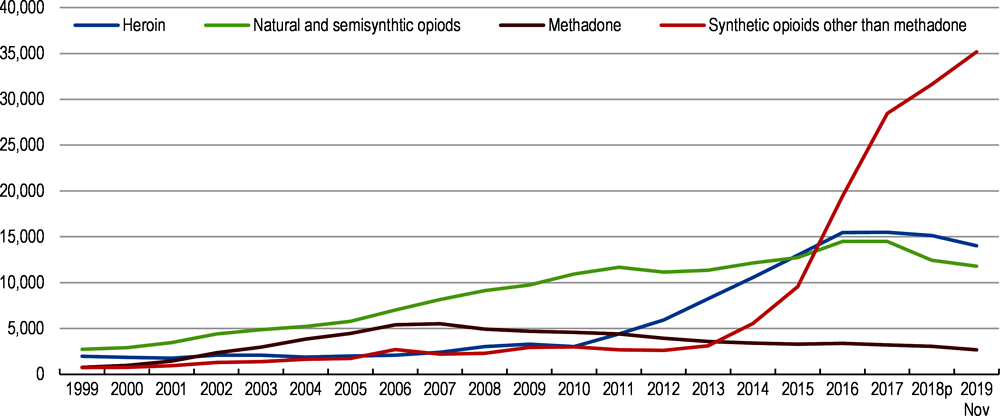

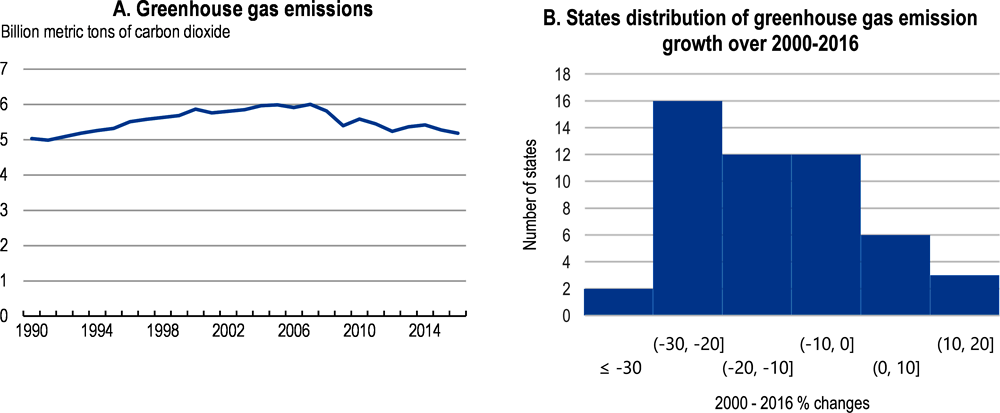

A final area of disparities across population groups concerns health. For example, differences in utilisation of health care by income group are stronger than in many OECD countries (OECD, 2019[56]). In part, this may reflect incomplete health insurance coverage as well as geographic differences in provision. While health un-insurance rose slightly in 2018 to 8.5% of the population, it remains around half the rate that existed before the role out of the Affordable Care Act. Nonetheless, health disparities can be very large between population groups, with health assessments of American Indians being considerably worse than the national average (Baciu et al., 2017). Disparities in health outcomes by some measures across population groups have been gradually declining. For example, over the last decade the difference between Black and White life expectancy at birth has narrowed by over 1 year, although the gap remains sizeable at 3.6 years and is partly driven by declining white life expectancy. Notwithstanding the relative improvement, life expectancy has been falling since 2014 and remains amongst the bottom quartile of OECD countries.