1. An overview of diversity, equity and inclusion in education

This chapter introduces a conceptualisation of the main themes in the area of diversity, equity and inclusion, and reflects on the external contexts that affect them. It also presents a holistic framework on how governments and schools can address diversity, equity and inclusion. It further looks at its various components, such as governance, resourcing, capacity building, school-level interventions, and monitoring and evaluation. This framework guides the subsequent chapters of this report. In addition, the chapter discusses how more equitable and inclusive education settings can have broader implications not only for students but also for societies as a whole.

This chapter provides the context shaping diversity, equity and inclusion in school education, conceptualises the main themes of the report and proposes a holistic framework for the analysis. It also discusses how more equitable and inclusive education systems can have broader implications not only for students but also for societies as a whole.

The chapter presents a holistic framework to analyse how governments and schools address diversity, equity and inclusion. It considers six dimensions of diversity - migration; ethnic groups, national minorities and Indigenous peoples; gender; gender identity and sexual orientation; special education needs; giftedness - and examines the intersections between them. The chapter reviews and discusses five key policy areas to consider when analysing equity and inclusion in education: governance; resourcing; capacity building; school-level interventions; and monitoring and evaluation. The subsequent chapters will analyse the issues relevant to each individual component of the holistic framework in more depth.

This chapter and this report focus mostly on school education. Indeed, while examples on early childhood education and care (ECEC) and higher education are mentioned when particularly relevant, they are not considered as key focus points in this report. The report is based on the work of the Strength through Diversity Project, which will also be referred to as “the Project” throughout.

Education policy does not happen in a vacuum. It requires openness and interactions between systems and their environments and is influenced by economic, political, social and technological trends (OECD, 2016[1]; OECD, 2019[2]). The major global developments of our time, such as demographic shifts, migration and refugee crises, rising inequalities, and climate change have contributed to the increasing diversity found in our countries, communities and classrooms. These changes warrant reflection about the implications that diversity has on education systems and conversely, the potential role education systems play in shaping these trends and building more sustainable, cohesive and inclusive societies for tomorrow.

Ageing population and urbanisation

In 29 out of 361 OECD countries, natural population decline2 is a reality across several regions, and ageing in cities and rural areas is significant. This demographic change will have considerable social and economic impacts (OECD, 2019[3]). The first major driver of population decline is the declining total fertility rates (TFR).3 The average TFR of OECD countries decreased from around 2.8 children per woman of childbearing age in 1970 to somewhere between 1.3 and 1.9 in 2020, which is well below the rate (2.1 children per woman) needed for population replacement (OECD, 2022[4]). Consequently, many OECD countries will experience declining numbers of students and graduates over the next decade (Santa, 2018[5]). The second major driver of population decline is ageing which results from people living longer lives and, consequently, the elderly population (aged 65 and over) continuing to grow at an unprecedented rate across all OECD countries (OECD, 2022[6]). The ageing population trend also poses a challenge to modern societies; ageing populations have different educational needs, compared to the traditional school population, particularly concerning their need to develop technological and digital literacy, which they would not have learnt as part of their initial education. From a lifelong learning perspective it is of great importance to foster the development of digital skills, using a combination of policies that provide high-quality education and training for all, anticipate changes in the demand of skills, and ensure that education and training systems are aligned with labour market needs (OECD, 2019[7]).

These changes in population composition have not affected countries uniformly but affected some areas more than others. On the one hand, the decline of agriculture and traditional primary industries in rural areas has made cities increasingly important and attractive. Young people migrate out of the countryside to study, find more and better employment opportunities, and make use of amenities in larger cities (OECD/European Commission, 2020[8]). This trend of rural depopulation has thus been driven by the positive net migration towards metropolitan regions in recent years, which is generally known as urbanisation (OECD, 2020[9]). The number of people living in cities more than doubled in the last 40 years from 1.5 billion in 1975 to 3.5 billion people in 2015, with almost half of the world’s population living in cities, and this share is estimated to reach 55% by 2050 (OECD/European Commission, 2020[8]).

These trends have important implications for equity and inclusion within education systems. Quality and access to education show great variation between rural and urban areas, as cities offer more and better opportunities in education compared to rural areas (OECD/European Commission, 2020[8]). In most countries, there are more socio-economically disadvantaged students in rural4 than in urban schools, and students in rural schools tend to underperform in secondary education and are less likely to complete a higher education degree in comparison to students in cities (OECD, 2014[10]; OECD, 2019[11]). In addition to the urban-rural gap in education systems, inequities within cities are also on the rise. Some of the urban inequities that threaten equity and inclusion in education are unequal allocation of educational resources, lack of access to cultural institutions, residential segregation in major cities, higher concentration of single-parent families, and more disparate income levels (OECD, 2014[12]). Geographic inequalities within cities are highly interlinked with social and economic status, which further presents a risk of residential and social segregation in schools (OECD, 2017[13]; OECD, 2019[14]). Moreover, there are significant differences in educational outcomes between students from different socio-economic backgrounds, which suggests that education is both a predictor and the outcome of segregation (Cerna et al., 2021[15]).

Ageing and urbanisation take place within the context of other socio-economic trends that vary widely among countries and regions. On the one hand, lower income countries tend to have higher fertility rates (World Bank, 2016[16]). On the other hand, countries with greater economic and political stability are preparing for the realities of a rapidly ageing population, whereby the elderly outnumber those of working-age.

The increasing diversity associated with these trends has important implications for education systems (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). For example, many OECD countries are experiencing a general decline in the school-age population, resulting in excess school capacity in certain regions and communities. However, areas in which schools have the capacity to take more students are unlikely to be those that generally receive an influx of students (which are typically urban, rather than rural, areas). This phenomenon may thus drain resources from where demand outstrips capacity.

Increasing migration and refugee crises

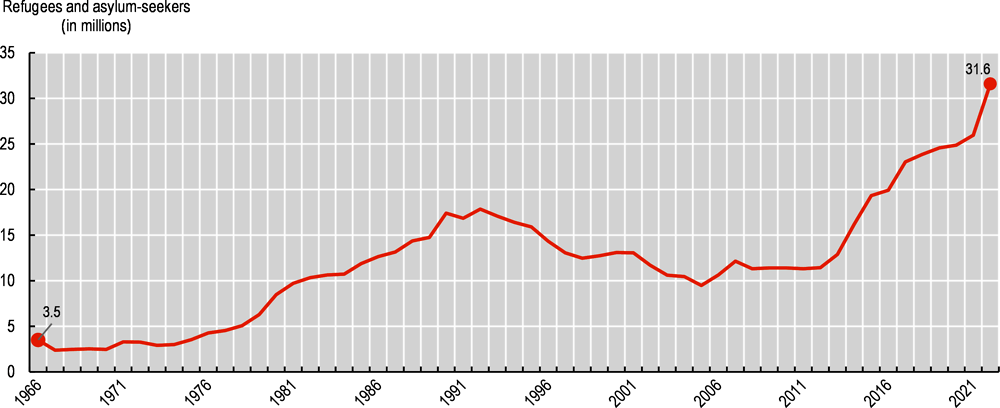

Further demographic changes over the last decades have also been driven by migration flows, which are profoundly changing the composition of societies and accordingly of schools and classrooms (Cerna, Brussino and Mezzanotte, 2021[17]). Immigrants are significantly more concentrated in specific types of regions than the native-born population. in the 22 OECD countries with available data, more than half of the foreign-born population (53%) lives in large metropolitan regions, compared to only 40% of the native-born population (OECD, 2022[18]). Student populations and classrooms in urban areas are therefore more diverse and projected to become increasingly more so due to trends in migration (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). Refugee crises have also been occurring more often, and on a larger scale, in the last couple of decades. The rapid increase in the numbers of refugees can be seen in Figure 1.1. The 2014-2015 refugee crisis has had a major effect on OECD countries due to the number of those and the comprehensive policy response required. Even though many of the countries had already welcomed previous flows of refugees, the magnitude and diversity of the flows within a short time period was unprecedented (Cerna, 2019[19]).

According to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of globally displaced people (refugees, internally displaced people and asylum-seekers) as of June 2022 is at a record high of over 103 million people (UNHCR, 2022[20]). As of mid-2022, there were 31.6 million refugees and asylum-seekers around the world (Figure 1.1), with approximately half being under the age of 18 (UNHCR, 2022[20]). As of November 2022, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has also forced 7.8 million people to flee their homes, with the number of refugees continuing to rise (UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2022[21]).

Moreover, the adverse effects of climate change and natural disasters, such as rising sea levels, desertification and extreme weather conditions, will further exacerbate existing refugee crises, leading to a higher number of displaced people, and worsening living conditions for many vulnerable groups (UNHCR, 2022[23]). Indeed, millions of people are fleeing their homes due to natural disasters and this situation is projected to become more severe in the future (OECD/EBA, 2022[24]). Given the prominence and severity of refugee crises around the world, it is crucial that education systems address the diverse needs of refugee students, including their learning, social and emotional needs, and promote their inclusion in schools (Cerna, 2019[19]).

Importantly, demographic change and increased mobility lead to questions about the fundamental design of today’s education systems, and their role in building nation-states by transmitting a common language, history and identity. Globalisation and increasing diversity are creating fissures in assimilationist models as influences beyond national affiliations progressively seep into our everyday lives. There is also a growing emphasis in the public discourse on the need to foster tolerance and respect of others since global competencies are crucial for maintaining international co-operation in the pursuit of world peace and addressing shared challenges like climate change.

Rising inequalities

Global economic growth has increased in recent decades, lifting millions out of poverty. However, this growth is not benefiting everyone equally. Almost all OECD countries have experienced rises in income inequality in the last 30 years (OECD, 2011[25]; OECD, 2015[26]; OECD, 2016[27]), social mobility has stalled (OECD, 2018[28]), and the middle class has been squeezed by rising costs, employment uncertainty and stagnating income (OECD, 2019[29]; OECD, 2021[30]). Moreover, technological progress can exacerbate inequality. In the face of automation, artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalisation, labour market demand for medium-level skills is shrinking while high- and low-level skills (for tasks that are difficult to automate) are in increasing demand (OECD, 2013[31]; OECD, 2016[32]). This led to a hollowing out of jobs involving mid-level skills (OECD, 2016[32]). The result has been a pattern of job polarisation by skill level in many but not all OECD countries (Autor, 2015[33]; Berger and Frey, 2016[34]). This means important job gains in some industries and regions and significant job losses in others. As job prospects shift, the transition can be especially difficult for individuals in rural areas where there is lower technological readiness and fewer opportunities to adapt.

Widening inequality also has significant implications for growth and macroeconomic stability, as it can lead to a suboptimal use of human resources and raise crisis risk (Dabla-Norris et al., 2015[35]). Inequality perpetuates socio-economic disadvantage and intergenerational mobility by hindering the ability of disadvantaged people to invest in greater education and training for themselves and their children (Katharine Bradbury and Robert K. Triest, 2016[36]). In fact, children whose parents did not complete secondary school are 4.5 times less likely to go to tertiary education than children who have at least one parent with a higher education degree, on average across countries participating in the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) (OECD, 2014[37]). Education has an important role to play in breaking this cycle by ensuring that all students receive the opportunities and support needed to succeed in the global future.

Digitalisation

The way we work, consume and communicate with each other has changed rapidly over the past decades as nearly every area of people’s lives and work has been reshaped by the digital transition (OECD, 2019[38]). New digital technologies and information and communication technology (ICT) generate both opportunities and challenges for inclusive education. On the one hand, there is potential to support and improve education processes of students with special education needs (SEN), minority groups and students living in areas that have more limited traditional educational offerings. Examples include personalised learning or Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to create more equitable and inclusive curricula (OECD, 2021[39]) as well as computer aided learning on tablets and iPads (UNESCO, 2020[40]). On the other hand, many countries face a real challenge regarding inequalities in access to digital technologies and the Internet in education. To overcome these inequalities, policies to encourage the participation of underrepresented groups in the digital economy have been put in place through online universities or digital learning workshops (van der Vlies, 2020[41]). Another aspect is gender-based digital exclusion due to a lack of access to skills and technological literacy for girls, who are less often exposed to technology, contributing to the digital gender divide in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education. To bridge inequalities of this nature, campaigns aimed at awareness-raising and policies providing enhanced, safer and more affordable access to digital tools are key (OECD, 2018[42]).

Digitalisation can have implications also for students’ well-being, which is a core aspect of inclusion. Indeed, while digital spaces offer vast opportunities for children to play, learn and explore, there are increasing digital risks. Some examples include cyberbullying, hate speech and revenge porn which may negatively affect children’s well-being (Burns and Gottschalk, 2020[43]). Children who are victims of cyberbullying, for instance, tend to show higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which may affect their education (Gottschalk, 2022[44]). Some students are more exposed to the risk of being cyberbullied than others: students with SEN and those who identify as LGBTQI+ (which stands for lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer, intersex) generally incur in this risk. Girls are also more likely to be cyberbullied than boys are (ibid.), highlighting that this is a digital risk that may be disproportionately experienced by different student groups and can therefore affect equity and inclusion in the school environment. Children with SEN, those facing mental health difficulties, and those with physical disabilities might also be disproportionately vulnerable to exposure to digital risks (El Asam and Katz, 2018[45]).

Data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 show that students’ use of the Internet continues to increase while the opportunity to learn digital skills in school is far from universal. Indeed, students with a higher socio-economic status and with more educated parents are more likely to have better digital schools. Schools can foster proficient readers in a digital world by closing these gaps and teaching students basic digital literacy (Suarez-Alvarez, 2021[46]). Thus, providing all students with the critical thinking skills necessary to safely navigate digital spaces and technology is an important commitment for the development of an equitable and inclusive education system.

Weakening trust and social cohesion

The democratic process relies on the civic knowledge and skills of citizens, as well as their engagement in public matters (OECD, 2019[2]). Trust is an important indicator to measure how people perceive the quality of, and how they associate with, government institutions in democratic countries (OECD, 2022[47]). On average, OECD countries are performing reasonably well on various measures of governance, such as citizens’ perceptions of government reliability, service provision and data openness. However, trust levels decreased in 2021 as countries struggle with the largest health, economic and social crisis in decades (though they remain slightly higher than in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis) (ibid.). Public confidence is now evenly split between people who say they trust their national government and those who do not. Historical data show that it takes a long time to rebuild trust when it is diminished: for instance, it took about a decade for public trust to recover from the 2008 crisis (ibid.). Furthermore, the OECD (2022[47]) has found that disadvantaged groups with less access to opportunities have lower levels of trust in government. In particular, younger people, women, people living on low incomes, people with low levels of education, and people who feel financially insecure consistently report lower levels of trust in government. Across countries, there is a sense that democratic government is working well for some, but not well enough for all.

Education can help societies increase trust and social cohesion. Indeed, individuals’ higher levels of education generally translate into greater civic participation, such as voting and volunteering, which help to build social cohesion (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]; OECD, 2010[49]). All these facts combined can contribute to a successful and healthy democracy (ibid.). There are thus incentives for governments to invest in quality education for all citizens, including and particularly for diverse groups, to eliminate barriers to their inclusion in education and generate benefits for both individuals and the societies in which they live. There exists a large literature that examines the economic impact of diversity, including the assessment of how ethnic and immigrant diversity affects social cohesion. Most of this literature focusing on OECD countries addresses how diversity can affect trust, voting patterns, civic participation, preferences for redistribution and investment into public goods (OECD, 2020[50]).

Moreover, the inclusion of minority groups in education has an impact on other groups’ development (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). Indeed, there is mounting evidence that social interactions between groups have a positive impact on social cohesion, and particularly, trust. As children go through their early life experiences, they form their attitudes and beliefs about other groups, which may be harder to change as they grow older (ibid.). Young people must have opportunities to interact with members of other ethnic groups for meaningful cross-group bonds to develop - and diverse schools can offer more of these opportunities. Indeed, inclusive school environments are characterised by positive social experiences for all students (Nishina et al., 2019[51]), such as decreased bullying, reduced loneliness and greater numbers of cross-group friendships. In addition, studies on students in inclusive environments show that those who learn in such schools report greater interest in living and working in ethnically diverse environments when they become adults and are more likely to do so as adults. By contrast, ethnically isolated schools may limit opportunities for young people to challenge skewed perceptions and assumptions about people from other racial groups (Tropp and Saxena, 2018[52]).

In increasingly diverse societies, the need to adapt education systems to all learners’ needs will be essential in building cohesion and inclusive societies that leave no one behind. Indeed, inclusive education can offer all children a chance to learn about and accept each other’s abilities, talents and needs (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). This process, through the fostering of meaningful relationships and friendships, can strengthen social competences while also building social cohesion (Council of Europe, 2015[53]). In an increasingly globalised and complex world, inclusive education can strengthen the trust and sense of belonging of citizens and among citizens (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]).

Well-being and mental health

Across the OECD, up to one in five people are living with a mental health condition at any time, and around one in two people will experience mental ill-health in their lifetime (OECD, 2021[54]). Children and adolescents’ mental health can have an important impact on their education. The majority of mental disorders tends to begin during school years: half of all mental illnesses begin by the age of 14 and three-quarters by mid-20s (Kessler et al., 2007[55]; OECD, 2018[56]), with anxiety and personality disorders sometimes beginning around age 11 (OECD, 2012[57]).

Mental health problems can affect many areas of students’ lives, reducing their quality of life and academic achievement, including early dropout from school (Breslau et al., 2008[58]). They can also affect a student's energy levels, concentration, dependability and optimism, hindering performance (Eisenberg et al., 2009[59]; Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2020[60]). Beyond education, living with a mental health condition makes it more difficult to stay in school or employment, harder to study or work effectively, and more challenging to stay in good physical health (OECD, 2021[54]). These individual and social costs also have an economic dimension. Mental health problems represent the largest burden of disease among young people, and mental ill-health is at least as prevalent among young people as among adults (OECD, 2015[61]).

Across all countries that have tracked population well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the mental health status of young people has been markedly worse than that of the general population (OECD, 2021[62]). Often, the mental health of these population groups has worsened faster than that of the general population. At the same time as mental health declined, there were significant disruptions to mental health support and services delivered in schools, and other settings outside of specialist mental health care. Worldwide, 78% of countries reported at least partial disruptions to related school programmes (WHO, 2020[63]). Data from March 2021 in Belgium, France and the United States reveal that the share of 15-24 year-olds reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression was more than twice as high than the most recent data available from before the outbreak (Sciensano, 2021[64]; Santé Publique France, 2021[65]; U.S. Census Bureau, 2021[66]).

The increased prevalence of mental disorders entails important challenges for education systems that have to support the mental health of students, and ensure that their well-being needs are being met.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has had, and is still having, a profound impact not only on people’s health, but also on how they learn, work and live. At the peak of the crisis in 2020, more than 188 countries, encompassing around 91% of enrolled learners worldwide, closed their schools to try to contain the spread of the virus (UNESCO, 2020[67]). In 2020 and 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the school attendance of 1.5 billion students (Vincent-Lancrin, Cobo Romaní and Reimers, 2022[68]), with schools remaining closed or being re-opened and then closed again depending on the severity of the health situation. Reasons for re-opening schools despite the unstable health conditions varied across countries, but included the need to develop students’ knowledge and skills, catch up on learning losses, provide extra services, and allow parents to return to work, among others (Reimers and Schleicher, 2020[69]). A number of schools switched to hybrid learning, combining in-person schooling with distance learning where students and teacher alternated between the two modes of delivery (OECD, 2021[70]).

School closures carry high social and economic costs for people across various communities. Their impact, however, is particularly severe for the most vulnerable and marginalised students and their families. The disruptions to learning caused by school closures can exacerbate already existing disparities within education systems while also affecting other aspects of these students’ lives, such as interrupted learning, poor nutrition, exposure to violence and exploitation, and increased dropout rates (UNESCO, 2020[71]).

During school closures, education systems had to rapidly adapt and find solutions to ensure educational continuity for their students. However, as systems moved to e-learning, the digital inequalities in connectivity, the gaps in access to devices and the varying skill levels of students became a key challenge for ensuring equity and inclusion in education. For instance, parents in more advantaged families were likely to have had better digital skills and be better equipped to support home learning for their children. Many students living in camps, informal settlements and overcrowded places, such as refugee or Roma students, were unlikely to have had access to digital devices or a quiet place to study. Moreover, students with SEN may have experienced different barriers in accessing some types of devices or software, and non-native speaker students may have struggled without appropriate support (OECD, 2020[72]).

School re-openings, too, entailed challenges for countries to respond to disadvantaged and vulnerable students’ needs. As mentioned before, disadvantaged and vulnerable students have been on average significantly less engaged in remote learning (Lucas, Nelson and Sims, 2020[73]), and countries have been considering various measures to ensure educational equity and inclusive environments in order to limit further educational gaps for these student populations. Some areas that require particular attention from governments include ensuring the return to schools and containing dropout rates for vulnerable populations, addressing learning gaps, ensuring the well-being of students while supporting teachers and monitoring that these efforts are inclusive of all students. The pandemic has also highlighted the need for efficient and targeted use of education resources, as discussed more in depth in Chapter 3.

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that the future is unpredictable, and that people require adaptability and resilience to cope in a world that is rapidly changing (OECD, 2021[74]). Education is key in strengthening cognitive, social and emotional resilience5 among learners, helping them understand that living in the world means trying, failing, adapting, learning and evolving. Educational institutions and education systems, too, need to become more flexible and resilient to succeed amid unforeseeable disruptions. Resilient education systems plan for disruption, and withstand and recover from adverse events, are able to fulfil the human right to education, whatever the circumstances, and foster the level of human capital required by successful economies in the short and longer term (OECD, 2021[74]; Schleicher, 2018[75]). At the same time, resilient education systems develop resilient individuals who adjust to everyday challenges, play an active role in their communities, and respond to an increasingly volatile, uncertain and ambiguous global landscape (OECD, 2021[74]).

Climate change and environmental crises

The effects of the climate crisis are being, and will increasingly be, felt on a global scale (UNICEF, 2019[76]). Evidence shows that extreme temperature events have been increasing as a consequence of human-induced climate change (IPCC, 2021[77]). Increased temperatures, air pollution and extreme events such as floods, droughts and storms, are disrupting people’s lives around the globe. These changes will not only have significant consequences for the health and human capital of societies, but also for the education of children. In particular, they may affect vulnerable children and exacerbate current education inequalities (UNICEF, 2019[76]). Indeed, groups that are more susceptible to climate-related risks are individuals living under the poverty line in both urban and rural areas, those with physical impairments, young girls and boys, and minority and immigrant groups (Hijioka et al., 2014[78]; UNICEF, 2015[79]).

Climate-related disasters can damage or even destroy schools and learning materials as well as important infrastructure such as bridges and roads needed to access schools. These events can disrupt children’s learning for months leading to missed days of school, absenteeism and lower academic performance in comparison to students in other schools. Moreover, climate change affects clean air, safe drinking water, and sufficient nutritious food and secure shelter, which has compounding effects on children’s academic well-being. The risk in livelihood security and income results in parents being unable to afford school costs, and children often miss classes to help with household activities. In some cases, families are forced to migrate which frequently translates to dropouts or lower academic performance (UNICEF, 2019[76]).

Air pollution also creates a burden on student’s learning. As reported by the World Bank (2022[80]), a study in Barcelona (Spain) shows that, adjusting for socio-economic status, students exposed to high pollution levels in school had less cognitive development growth than those in less polluted schools (Sunyer et al., 2015[81]). Similarly, evidence from the United States demonstrates lower test scores and more absences for children attending schools downwind of a major highway (Heissel, Persico and Simon, 2019[82]; UNESCO, 2020[83]). Furthermore, at the end of secondary school, high levels of transitory pollution and extreme temperatures can reduce students’ performance on high-stakes exams used to select students for tertiary level education. Consequently, students most affected by adverse environmental conditions may be less likely to gain entrance into tertiary educational institutions or fail to enter the most prestigious institutions (Ebenstein, Lavy and Roth, 2016[84]; Graff Zivin et al., 2020[85]; Graff Zivin et al., 2020[86]; Park, 2020[87]). The resulting suboptimal educational and labour market sorting may alter long-term skill acquisition and earnings (Horvath and Borgonovi, 2022[88]; Kyndt et al., 2012[89]).

As socio-economically disadvantaged families and ethnic minority communities are more likely to live closer to pollution sources, such as toxic waste, where housing is more affordable, this can have a larger impact on the educational outcomes of disadvantaged student groups (Persico, 2019[90]). This is even more concerning in the Global South, where air pollution levels are higher, giving rise to growing challenges in offering suitable learning environments for students (World Bank, 2022[80]).

An overview of the state of equity and inclusion in education systems across the OECD can provide an important starting point for this report’s analysis. Indeed, without relevant information on the current state of equity and inclusion and progress achieved over the years in these areas, any analysis would only provide a partial picture. Yet, efforts to provide a comprehensive analysis of equity and inclusion face several challenges, stemming from measurement difficulties, complexity of the field, limited data availability, and more (as discussed more extensively in Chapter 6).

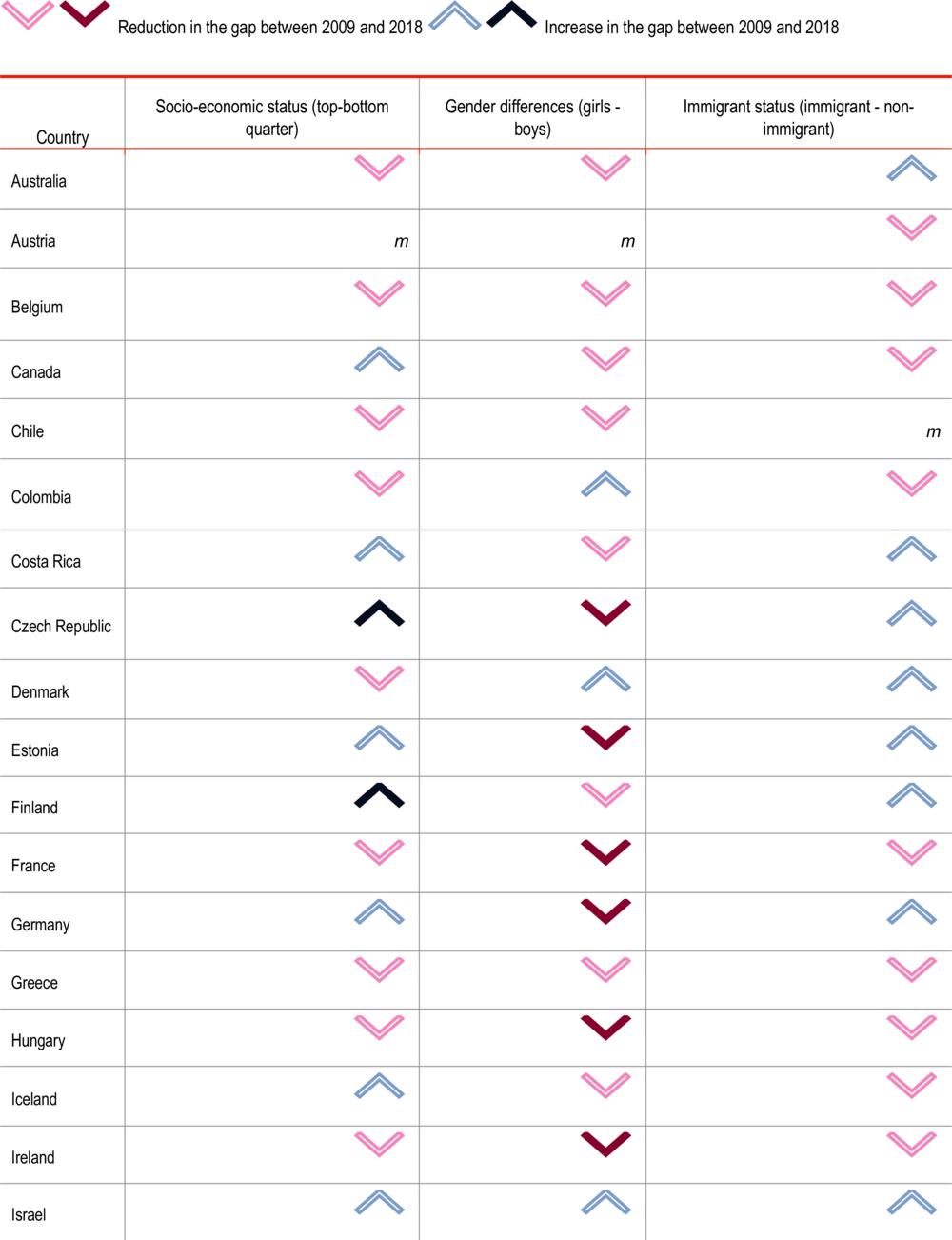

Data from PISA 2018 provides a first picture of the state of equity and inclusion of diverse student groups, namely in terms of socio-economic advantage and disadvantage, gender and immigration status. In terms of socio-economic status, PISA found that socio-economically advantaged students outperform disadvantaged ones across all OECD countries with available data. On average across OECD countries6 the score difference between students in the top and bottom quarters of the ESCS7 index was 89 points, with variations across countries. In terms of gender differences, the data shows a reading gap in favour of girls across all OECD countries in 2018, with an average difference of 29 points. The gap appears larger for students in the 10th (bottom) percentile, with an average of 41 points, compared to students that perform in the 90th percentile, who show a gap of 18 points. Lastly, in terms of immigration status, in almost all OECD countries there is a reading gap in favour of native students compared to immigrant students. On average, immigrant students performed 40 points lower than their native peers. This difference is smaller, between the two groups, after accounting for gender, and students' and schools' socio-economic profile.

While this overview provides a static picture of the gaps in 2018, considering the trends over the past decade can provide important information regarding the evolution of these gaps. As countries have long considered the importance of improving their results and fostering equity in education and the inclusion of all students.

Table 1.1 provides an overview of evolution of the differences in scores between different groups from 2009 to 2018 (the specific values are provided in the Annex Table 1.A.1). The data show that gender is the only dimension of diversity that has seen a widespread evolution over this time period: it is the only dimension for which a large number of countries shows a significant reduction in the gap between girls and boys. No country displays a statistically significant increase in gender gaps in reading scores. Nevertheless, a wide variation of developments can be observed. In the Czech Republic, Estonia, Ireland, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden, the scores of boys and girls both increased, but it increased to a larger extent for boys, thus reducing the gender gap. In France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Portugal, Republic of Türkiye and on average across OECD countries, reading scores for boys increased, but decreased for girls. Finally, in Hungary, Japan, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and Switzerland, the scores of both groups decreased, but girls’ performance to a larger extent, thus effectively also reducing the gender gap.

For the other two dimensions no clear pattern appears, as most changes are not significant and they are going in both directions. Notably, the Czech Republic, Finland and the Slovak Republic are the only countries that show a significant change between 2009 and 2018 in terms of socio-economic status of their students. While in the Czech Republic the scores of both groups increased over time (however more so for advantaged students, thus exacerbating the gap), the scores in Finland and the Slovak Republic decreased, but more so for disadvantaged students.

The immigration status variable shows mixed results: among the few countries with significant results, Italy and Luxembourg show a decrease in the gap between the two years. In both countries, the score of students with an immigrant background increased and the score for students without an immigrant background decreased, thus reducing the gaps. On the contrary, in the Netherlands, the scores for both groups decreased, but for students with an immigrant to a larger extent, thus increasing the gap. In Slovenia, the score of students with an immigrant background decreased while it increased for students without such background, thus also exacerbating the divide between the two groups.

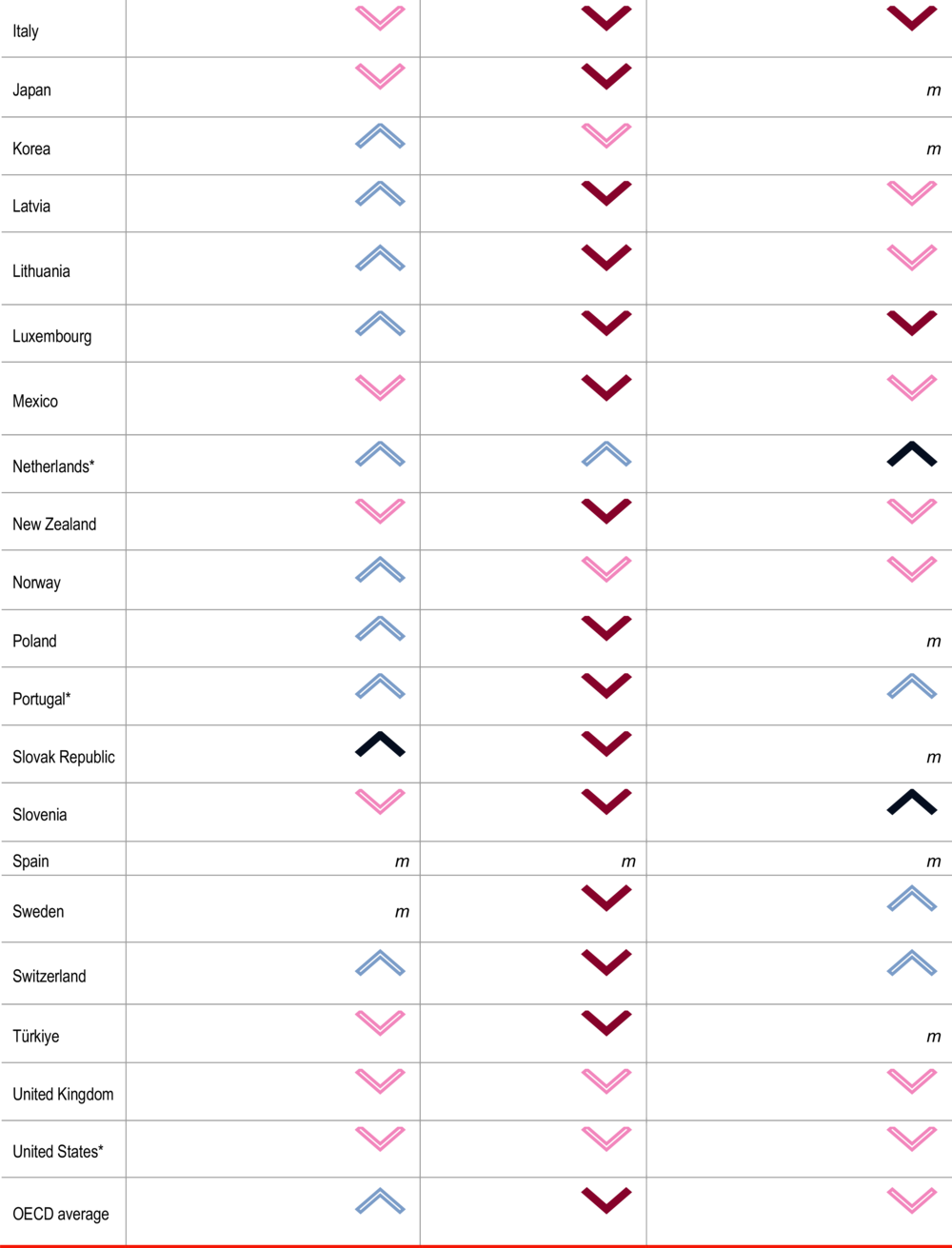

Defining the key concepts in the area of diversity, equity and inclusion in education is no easy undertaking. These concepts vary not only across literature, but also in the meaning that different education systems attribute to them. Indeed, there is neither a universal definition of equity nor of inclusion in education. The Strength through Diversity Project has adopted some definitions to operationalise the concepts and provide some basis for its analysis, but these are not meant to be normative or prescriptive for countries. Most countries and education systems have developed their own definitions, which reflect their history, priorities and educational goals.

Most jurisdictions across the OECD have a definition of equity and inclusion

The majority of education systems have a definition of both equity and inclusion (Figure 1.2). Twenty-eight jurisdictions reported in the Strength through Diversity Survey 2022 (see Annex 1.A) that they had a definition of equity, either formal or operational, and 30 have a definition of inclusion. Only four jurisdictions did not have a definition of inclusion (Australia, Finland, the Netherlands and New Zealand) and four did not have a definition of equity (Denmark, Finland, Lithuania and New Zealand).

An analysis of the definitions and explanations of concepts provided by education systems (reported in Annex 1.A) shows that commonalities exist across education systems in the adopted definitions of equity. Twenty-three of the 30 education systems that reported having a definition mentioned explicitly that education should be provided without prejudice to student characteristics, background or origins. These elements span across social status, nationality, ethnic origin, gender, special education need or disability, sexual orientation, religious and political affiliation, language, health condition, parent education and place of residence. In this regard, 12 systems highlighted that special efforts should be made to prevent discrimination in education. Fifteen education systems also underlined the importance of ensuring equality of opportunity between students. According to Slovenia’s comprehensive definition, the notion of equal opportunity presupposes that each individual is treated in accordance with the law of justice - meaning that equals must be treated the same and others must be treated in accordance with their differences - in situations in which many people compete for limited resources (for example, acceptance into a quality school or university). Various systems, finally, underlined that access to education should be granted to all students (ten education systems), in order to avoid any gaps or differences between them (six), and allow them to achieve by removing barriers and obstacles (four). Additional points that were mentioned by a small minority of educations systems are reported in Table 1.2.

In relation to inclusion, the information reported in Annex 1.A shows the key elements that countries consider in their definitions. Out of the 30 countries that reported definitions in the Survey, 20 underlined that their understanding of inclusion concerns all students, without prejudice. Twelve countries also stressed the relevance of ensuring access and participation to the students to ensure their inclusion in education. In contrast to their approach to defining equity, several education systems (11) considered inclusion as concerning students with special education needs – at times exclusively and at times as a core but not exclusive focus. For instance, the concept of inclusion in the Flemish Community of Belgium “has a specific usage in that it refers to the leading principle for schools’ approach to pupils with SEN”. While Ireland does not have a general holistic definition on inclusion in education, it has a specific definition for the inclusion of students with SEN, which underlines that “a child with special educational needs shall be educated in an inclusive environment with children who do not have such needs unless the nature or degree of those needs of the child is such that to do so would be inconsistent”. Seven countries highlighted the role of mainstream education in the inclusion of students with SEN.

Another common element, which is shared with the systems’ definition of equity, was the focus on avoiding discrimination, with an explicit mention of various groups of students. However, it differs from equity as eight countries’ definitions of inclusion made explicit reference to the concept of diversity. Colombia, Mexico and Scotland (United Kingdom), for instance, stressed the importance of valuing and respecting students’ diversity.

A further difference is that inclusion definitions (for six education systems) stated the relevance of providing support and accommodations to students who require them, along with ensuring appropriate learning (ten systems) for all. Equality of opportunity was also mentioned by six education systems, as in the case of equity, as the removal of barriers (six systems). Finally, three education systems stressed the idea of inclusion being a process, which is a key aspect of the definition proposed by UNESCO and adopted by the Strength through Diversity Project (as discussed in the next section). Three systems also highlighted the importance of ensuring the quality of the education provided in regard to inclusion, as it is not enough for children to be allowed into education if not provided with high-quality learning. Additional points that were mentioned by a small minority of educations systems are reported in Table 1.2.

Given that, as discussed, education systems’ definitions vary widely, the Project has adopted specific definitions that allow for a shared understanding of the concepts when analysing policies and practices concerning equity and inclusion in education (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). These definitions are not meant to be prescriptive nor recommended for education systems to adopt, but reflect the main understanding of these areas in this report and throughout the work of the Project. The following sections describe the key concepts in the areas of equity and inclusion in education, and highlight the developments and principles that have led the Project to select these specific understandings.

Equity

The Strength through Diversity Project defines equitable education systems as being those that ensure the achievement of educational potential is not the result of personal and social circumstances, including factors such as gender, ethnic origin, Indigenous background, immigrant status, sexual orientation and gender identity, special education needs, and giftedness (Cerna et al., 2021[15]; OECD, 2017[13]). In operationalising equity in education, the OECD makes a distinction between horizontal and vertical equity (OECD, 2017[93]). While horizontal equity considers the overall fair provision of resources to each part of the school system (providing similar resources to the alike), vertical equity involves providing disadvantaged groups of students or schools with additional resources based on their needs (ibid.). Both approaches are complementary and play an important role in the process of inclusion of vulnerable groups of students (described below).

However, other organisations, projects and researchers adopt different definitions for the concept of equity, and for that of equality (Mezzanotte and Calvel, forthcoming[94]). For UNESCO, equity “considers the social justice ramifications of education in relation to the fairness, justness and impartiality of its distribution at all levels or educational sub-sectors” (UNESCO-UIS, 2018, p. 17[95]). UNESCO also defines the concept of equality, as “the state of being equal in terms of quantity, rank, status, value or degree”. Equality of opportunity, in particular, is understood to mean that everyone should have the same opportunity to thrive, “regardless of variations in the circumstances into which they are born” (UNESCO-UIS, 2018, p. 17[95]). Having been granted such opportunities and considered their innate abilities, however, students’ outcomes will still depend on how much effort they put in. This concept holds individuals accountable, as they are considered responsible for, and to have control over, their effort. This implies that the differences in outcomes that arise from differences in effort are fair, while those that derive from personal characteristics – such as socio-economic background or gender – are not fair. The definition adopted by the Project, as described above, is thus in line with the concept of equality of opportunity.

Inclusion

The OECD Strength through Diversity Project adopts a broad definition of inclusive education, while recognising that there exist various definitions of this concept and disagreements about these definitions (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). For the scope of this report and the broader work of the Project, inclusive education is defined as “an on-going process aimed at offering quality education for all while respecting diversity and the different needs and abilities, characteristics and learning expectations of the students and communities, eliminating all forms of discrimination” (UNESCO, 2009, p. 126[96]). More than a particular policy or practice related to a specific group of students or individuals, this definition identifies an ethos of inclusion and communities of learners, which does not only involve an individual dimension but also a communal one. The goal of inclusive education is to respond to all students’ needs, going beyond school attendance and achievement, while improving all students’ well-being and participation (Cerna et al., 2021[15]).

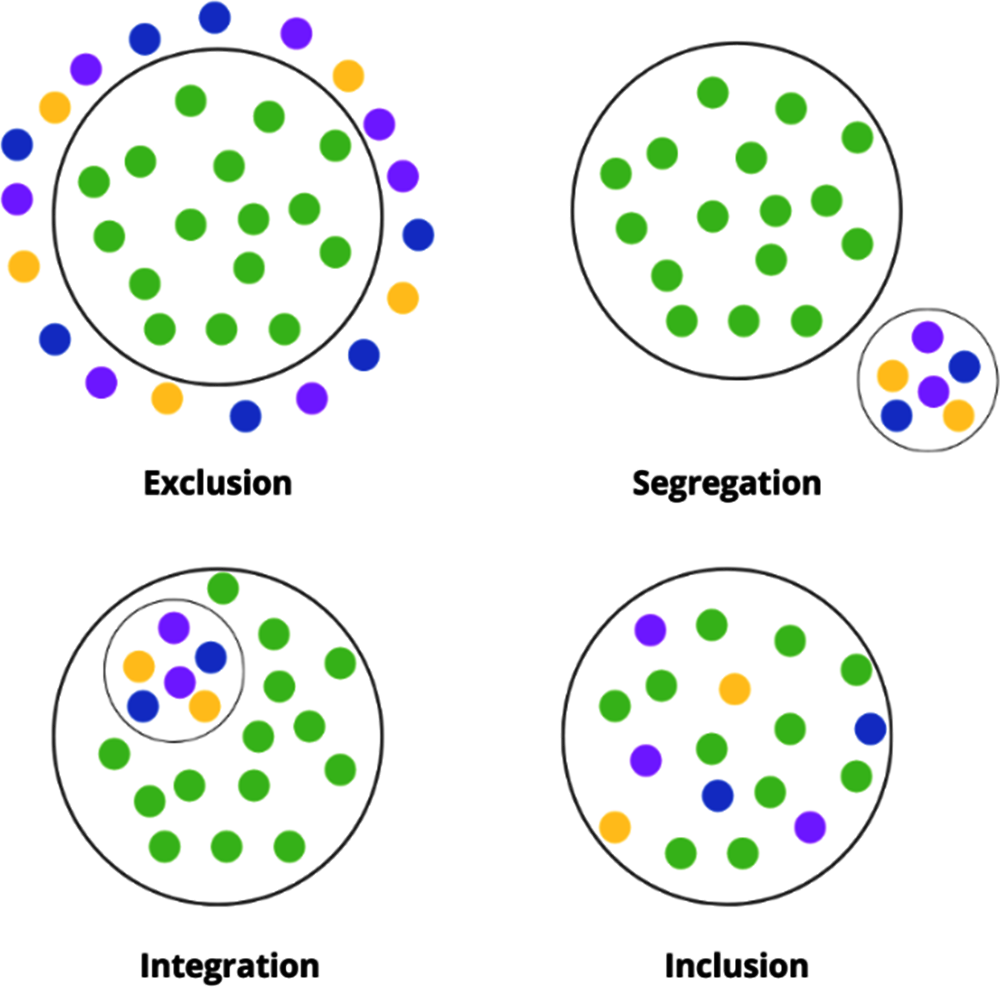

Inclusion can also be conceptualised as a historical development of different models of education. Researchers generally categorise educational systems into four categories: exclusion, segregation, integration and inclusion (Figure 1.3)

Firstly, exclusion occurs when students are directly or indirectly prevented from or denied access to education in any form. This may happen when students are not allowed to register or attend school, or conditions are placed on their attendance. Exclusion in education does not only mean “out-of-school children” but can have many expressions (International Bureau of Education, 2016[98]; UNESCO, 2012[99]). For instance, exclusion can be from entry into a school or an educational programme, due to inability to pay the fees or being outside the eligibility criteria. Segregation occurs when diverse groups of students are educated in separate environments (either classes or schools). This can happen, for instance, when students with a learning disability are forced to attend a school/class exclusively for students with disabilities, but also when schools teach either females or males only (i.e., same-sex or single-sex education). Integration is achieved by placing students with diverse needs in mainstream education settings with some adaptations and resources, on the condition that they fit into pre-existing structures, attitudes and an unaltered environment (UNESCO, 2017[100]). For example, integration can consist in placing a student with a physical impairment or a learning disability in a mainstream class but without any individualised support and with a teacher who is unwilling or unable to meet the child’s learning, social or disability support needs. In literature and policy, integration and inclusion have been compared and sometimes confused, whereas the two concepts present significant differences.

Inclusion is a process that helps to overcome barriers limiting the presence, participation and achievement of all learners. It is about changing the system to fit the student, not changing the student to fit the system, because the “problem” of exclusion is firmly within the system, not the person or their characteristics (UNICEF, 2014[101]). According to UNICEF (2014[101]), inclusive education is defined as a dynamic process that is constantly evolving according to the local culture and context, as it seeks to enable communities, systems and structures to combat discrimination, celebrate diversity, promote participation and overcome barriers to learning and participation for all people. All personal differences (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, Indigenous status, language, health status, etc.) are acknowledged and respected.

UNESCO (2008[102]) has also described the key factors of inclusive education for all students: i) the promotion of student participation and reduction of exclusion from and for education; and ii) the presence, participation and achievement of all students, but especially those who are excluded or at risk of marginalisation. The key message is that every learner matters and matters equally. Moreover, according to UNESCO (2005[103]), inclusion highlights the groups of learners who may be at risk of marginalisation, exclusion or underachievement, including students belonging to ethnic groups, national minorities or immigrant students, among others. UNESCO’s interpretation also implies a moral responsibility to ensure that groups that are more statistically at risk are carefully monitored and steps are taken to ensure their presence, participation and achievement in education (UNESCO, 2005[103]).

Why it is relevant to differentiate between equity and inclusion

The concepts of equity and inclusion are strictly related and overlap, but they emphasise complementary elements that contribute to successful education systems. Equity stresses the role of providing the same opportunities to all students and equalising resources provided to support them. The goal of equity is to give the means to all students to achieve at the best of their capabilities.

A focus on educational equity may not be enough to fully address student diversity. Indeed, an exclusive focus on equity could lead to narrow assimilationist or isolationist policies and practices without fully addressing inclusion. For example, having all students achieving a minimum level of performance and meeting educational goals that are established without considering the diversity of their experiences (assimilation) can promote equity but not inclusion. Inclusion encompasses the principles of equity while broadening this focus through proposing a transformative approach to remove barriers for all students, stressing in particular the need to recognise and address different experiences, needs and challenges of diverse and vulnerable groups of students. While equity focuses on opportunities, inclusion is more strictly associated to who the individual is, i.e., their identity (e.g., cultural identity, gender identity), and whether the education system acknowledges individuals for who they are (i.e., the sense of belonging). Moreover, inclusion fosters students’ well-being as a key element to ensure their full participation in education through the development of their self-worth and sense of belonging to schools and communities. Well-being is generally not as much of an explicit focus in relation to equity.

Improving equity does not necessarily result in the validation of an individual’s sense of self and belonging within society. If that validation does not occur, it may hinder social cohesion on a larger scale and on a longer time frame. Educational research has brought about a better understanding of the necessity of responding to individual student needs by providing each learner with individualised feedback and providing inclusive and multicultural programmes (Nusche, 2009[104]). In this context, education systems cannot only play an important role in boosting equity, but also in fostering just and inclusive societies.

Why equity and inclusion in education matter

The importance of fostering equity and inclusion in educational settings has various rationales, spanning from human rights, to educational, individual and societal gains (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). More equitable and inclusive education has been shown to provide benefits for all students in improving the quality of education offered, as it is more child-centred and focused on achieving good learning outcomes for all students, including those with a diverse range of abilities (UNESCO, 2009[105]). Greater equity in education can help students achieve their potential, which can have implications on their outcomes later in life. A carefully planned provision of inclusive education can not only improve students’ academic achievement, but also foster their socio-emotional growth, self-esteem and peer acceptance (UNESCO, 2020[83]). For instance, from a review by Ruijs and Peetsma (2009[106]), it appears that students with special education needs achieve academically better in inclusive settings than in non-inclusive settings. Research also shows that attending and receiving support within inclusive education settings can increase the likelihood of higher education enrolment for students with SEN (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2018[107]). These settings are also beneficial for students that have no disability or impairment, since attending a class alongside a student with SEN can yield positive outcomes for their social attitudes and beliefs (Abt Associates, 2016[97]). Similarly, with the inclusion in education of students from ethnic groups and national minorities, young people have the opportunity, through repeated exposure and practice, to engage with others who differ from them. This interaction can promote feelings of satisfaction and social efficacy within the current school setting and inform future social interactions and social adaptability in college, communities, and the workplace (Nishina et al., 2019[51]). The inclusion of diverse students can thus help to fight stigma, stereotyping, discrimination and alienation in schools and societies more broadly (UNESCO, 2020[83]). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action (1994[108]) asserts that: “Regular schools with inclusive orientation are the most effective means of combating discrimination, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all”. As predicted by Contact Hypothesis (Allport, 1954[109]), increased inter-group contact can lead to a reduction of hostility, prejudice and discrimination between groups, which can refer to all types of diversity. Instead, a context that allows contact between diverse peers can build strong social skills, an important asset in today’s diverse and international places of work.

Better academic and social outcomes for all students are correlated with improved labour outcomes later in life, as well as better health and well-being (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). Literature has shown the correlation between skills earned in schools and income levels from the labour market (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2008[110]), and an even stronger correlation between the years of education achieved and the returns to education, through an increase in productivity or the signalling effect of education8 (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2020[111]; Harmon, Oosterbeek and Walker, 2003[112]). Considering how important education and skills have become in the labour market, a critical question is whether such learning opportunities can be accessible to all. Previous OECD (2017[13]) work has found that countries have been advancing at different rates in providing quality education and skills development opportunities to disadvantaged individuals. In most countries, inequality in learning opportunities begins at birth, and often widens as individuals grow older (OECD, 2017[13]). These inequalities result in very different life outcomes for adults. In some countries, access to learning opportunities differs considerably between certain population groups, which highlights the need for more equitable and inclusion education systems.

Better education also provides a range of indirect benefits, which are also likely to entail positive economic consequences (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). For instance, greater education is associated with better health status and increases in some aspects of social cohesion and political participation (OECD, 2006[113]). In terms of health, research shows that more years of education and higher levels of qualification are associated with a lower incidence of physical and mental disorders. These relationships have been shown to hold across different countries, income ranges, age and ethnic groups (OECD, 2006[113]).

These positive effects on individual outcomes also lead to broader societal benefits (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). Economic literature has studied the role of education in rising incomes at the country level, in particular in terms of higher Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and its annual growth rate (Bassanini and Scarpetta, 2001[114]; Hanushek and Woessmann, 2007[115]). Providing more education, knowledge and skills to individuals, i.e., accumulating human capital, increases their productivity and employability, which in turn rises the country’s overall income and development. Individual non-economic outcomes also affect society more generally: better education can contribute to reduced violence and crime rates, reductions in the cost of healthcare and welfare systems (e.g., unemployment benefits, etc.), and can foster innovation. Policies that support individuals in obtaining the highest qualifications of which they are capable have the potential to provide not only personal, but also economic, benefits. This includes both savings in national healthcare and socio-political costs, such as greater political engagement, higher levels of trust, and more positive inter-group attitudes (Easterbrook, Kuppens and Manstead, 2015[116]).

The World Bank also argues that equity and inclusion in education are essential for shared prosperity and sustainable development (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]; World Bank Group, 2016[117]). Disparities in education are one of the major drivers of income inequality, both within and among countries. Without basic education, individuals in the bottom of a nation’s income distribution are unlikely to be successful in a globalised economy. As the World Bank World Development Report 2012 notes, fair and inclusive education is one of the most powerful levers for a more equitable society (World Bank, 2011[118]). While, as discussed, there are very important human, economic, social and political reasons for pursuing a policy and approach of more equitable and inclusive education, it is also a means of bringing about personal development and building relationships among individuals, groups and nations (UNESCO, 2005[103]). Inclusive education can further offer all children a chance to learn about and accept each other’s abilities, talents and needs (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). This process, through the fostering of meaningful relationships and friendships, can strengthen social competences while also building social cohesion (Council of Europe, 2015[53]). In an increasingly globalised and complex world, inclusive education can strengthen the trust and sense of belonging of people and among people.

Some scholars have raised concerns regarding the potential negative effects of an inclusive education system and the challenges in its implementation (Forlin et al., 2011[119]). For instance, a frequent argument against inclusive education is that it could have an adverse effect on the achievement of children without SEN (Mezzanotte, 2022[48]). The arguments against inclusion propose that students with SEN occupy the teachers’ attention, which might adversely affect other children (Dyson et al., 2004[120]; Huber, Rosenfeld and Fiorello, 2001[121]). In contrast, proponents of inclusive education sustain that in inclusive classes there is more adaptive education, which might have a beneficial effect on all students (Dyson et al., 2004[120]). Overall, literature has identified mostly positive or neutral effects of inclusive education on the academic achievement of students without SEN, in particular at the lower education levels (Kart and Kart, 2021[122]). Evidence indicates that it is possible for all learners to achieve at high levels in an inclusive school system (AuCoin, Porter and Baker-Korotkov, 2020[123]; Mezzanotte, 2022[48]).

Another important concept that relates to both equity and inclusion is diversity. Diversity corresponds to people’s differences which may relate to their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, language, culture, religion, mental and physical ability, class, and immigration status (UNESCO, 2017[100]). More specifically, it refers to the fact that many people perceive themselves or are perceived to be different and form a range of different groups cohabiting together. Diversity is multidimensional, might relate to physical aspects and/or immaterial ones such as cultural practices, and makes sense according to the boundaries defined by groups of individuals.

Students from diverse background are generally more disadvantaged in education, and, for this reason, become the target of equitable and inclusive reforms, practices and policies (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). As mentioned above, various countries emphasise the importance of focusing on specific groups of students and valuing their diversity in their definitions of equity and inclusion in education.

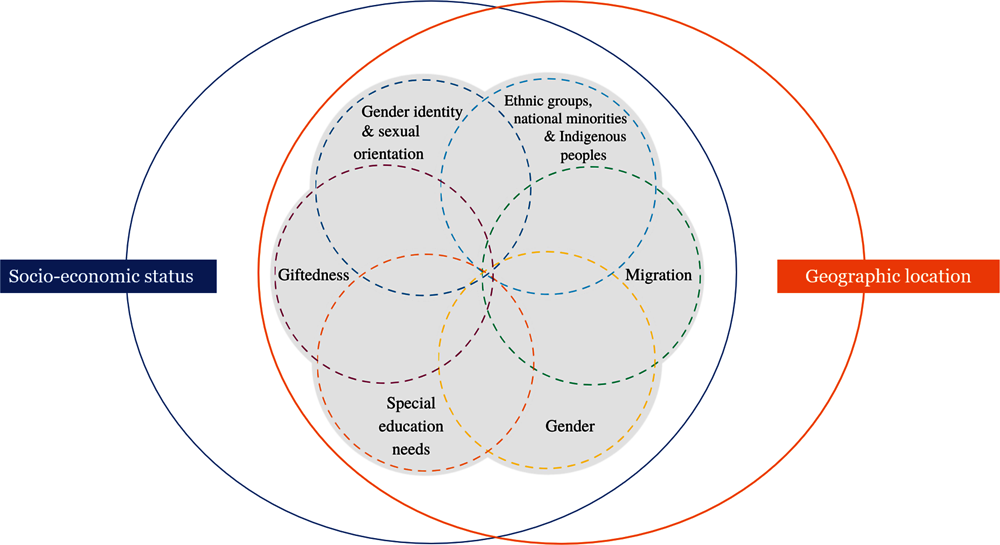

While acknowledging that many dimensions of diversity exist, the Strength through Diversity Project has focused on the following dimensions (Cerna et al., 2021[15]):

Besides the six dimensions of diversity, the Project also considers the role of two overarching factors, namely students’ socio-economic status and geographic location, as shown in Figure 1.4.

The following sections first introduce the key concepts considered by the Project in relation to the six dimensions of diversity, followed by the two overarching factors that shape the educational experiences of students.

Migration

The Project considers the range of migration experiences that individuals may have, whether direct (foreign-born individuals who migrated) or not (individuals who have at least a parent or guardian who migrated) (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). Ancestry, intended as migration experiences that go beyond the parental generation, is not considered in itself, but reflected in analyses that consider ethnic groups and other national-minorities induced diversity.

The Project focuses on international migration as a source of migration-induced diversity, irrespective of reasons for migration and the legal status of the individual migrant, while reflecting on the educational implications of factors like legal status, migration experiences and age at migration. For the scope of the Project’s analysis, individuals are considered to have an immigrant background or to have an immigrant-heritage if they or at least one of their parents was born in a country that is different from the country in which they access educational services (Cerna et al., 2021[15]; OECD, 2018[124]).

Ethnic groups, national minorities and Indigenous peoples

National minority is a complex term, for which no international definition has been agreed (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). It is therefore up to countries to define which groups constitute or not minorities within their boundaries. Minority groups can be categorised according to individuals’ immigrant status and nationality of origins, but also depending on their ethnic affiliation and Indigenous background. While individuals can perceive themselves or be perceived as forming an ethnic group, they are not necessarily officially considered as a national minority in the country they live in. Roma communities for example, while being widely perceived as an ethnic group, are not always considered a national minority (Rutigliano, 2020[125]). National minority is also an administrative category and should be thought about as such. While being useful in data collection and policy making, it often does not reflect the complex diversity between and within different ethnic groups.

Ethnicity refers to a group or groups to which people belong, and/or are perceived to belong, as a result of historical dynamics as well as certain shared characteristics (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). With variations between different contexts, these characteristics can correspond to geographical location and ancestral origins, cultural traditions, religious beliefs, social norms, shared heritage and language. As ethnicity has its basis in multiple social characteristics, it is not deterministically defined and someone can be a member of an ethnic group even if they differ from other group members on some dimensions. Ethnic affiliation might ultimately depend on the agency of an individual who chooses to be part of a specific ethnic group and, as such, places their identity in the context of a broader social group. This affiliation can be non-exclusionary and change over the life course, as individuals choose to adopt or reject such affiliation. Finally, ethnicity is fundamentally a criterion of differentiation that can be both a source of recognition and valorisation, and of inequalities and discrimination.

The concept of race is close to the notion of ethnicity and the boundaries between both are often blurry (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). However, race as a concept has been deconstructed since the second half of the 20th century, mostly through a worldwide UNESCO campaign in the 1950s, upheld by renowned anthropologists. It was shown that the concept of race, besides bearing a strong negative connotation in numerous countries (e.g., European countries), has little biological basis as biological differences across individuals from different racial groups are minuscule. It was highlighted that racial differences across individuals would have no bearing on education policy if it were not for their overlap with ethnic differences and for the structural discrimination faced by members of certain “visible”9 minority groups both in education settings and society more widely. It is important to acknowledge that some countries commonly use the notion of race in political and academic languages. However, its social origins rather than its biological bases are usually emphasised. Within the Project, the diversity related to the aforementioned characteristics is referred to as ethnicity and ethnic diversity, and the terms race and racial diversity are not used.

Indigenous peoples, according to the United Nations’ definition, are those who inhabited a country prior to colonisation, and who self-identify as such due to descent from these peoples and belonging to social, cultural or political institutions that govern them (United Nations, 2019[126]). The colonisation process in some countries has had a double impact on Indigenous peoples and in particular on children in relation to education. In addition to undermining Indigenous young people’s access to their identity, language and culture, colonisation has resulted in Indigenous children generally not having had access to the same quality of education that other children in their country have enjoyed. These two factors have generally undermined the opportunities and outcomes of various generations of Indigenous peoples and children, and still affect these populations today. Education systems may need interventions on their general design, to recognise and respond to the needs and contexts of Indigenous students (OECD, 2017[127]).

Students from ethnic minority groups and Indigenous communities are different groups, and may require varying policy responses based on their specific needs. Nonetheless, they often face similar challenges when it comes to education.

Gender

Although the words “sex” and “gender” are often used interchangeably, their definitions are different (Brussino and McBrien, 2022[128]). Sex refers to the biological and physiological characteristics of being male or female, such as reproductive organs and hormones (Council of Europe, 2019[129]). Gender involves social roles and relationships, norms and behaviours that boys and girls are informally taught, such as how they should interact with others, what they might aspire to become and what opportunities they might expect, based on their sex (ibid.). These socially determined roles and behaviours may or may not correlate with the sex assigned at birth. The Council of Europe has defined gender as “socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men” (Council of Europe, 2011[130]). The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that the “characteristics of women, men, girls and boys that are socially constructed” include “norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships with each other. As a social construct, gender varies from society to society and can change over time” (WHO, 2018[131]). Gender differs from sex as the latter refers to “the different biological and physiological characteristics of females, males and intersex persons, such as chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs” (WHO, 2018[131]).

In education, gender gaps have historically favoured males. However, over the past century, many countries have made significant progress in narrowing and even closing, long-standing gender gaps in educational attainment and today males on average have lower attainment and achievement than females in many OECD countries (Borgonovi, Ferrara and Maghnouj, 2018[132]).

Gender identity and sexual orientation

“Sexual and gender minorities” refers to LGBTQI+ people, that is, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex individuals. The “+” is often added to the LGBTQI acronym to include people who do not self-identify as heterosexual and/or cisgender but who would not apply the LGBTQI label to themselves either. These people include questioning individuals, pansexual individuals, or asexual individuals (OECD, 2020[133]). While the notion of gender has shifted towards a more inclusive definition, away from a binary and heteronormative understanding, policy makers and educators are facing new challenges regarding inclusion in schools. Gender is increasingly being acknowledged as a spectrum, and gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of being masculine, feminine or androgynous. Sexual orientation corresponds to the sexual and emotional attraction for the opposite sex, the same sex or both (Cerna et al., 2021[15]).

Studies show that LGBTQI+ people tend to suffer from significant social exclusion. In most OECD countries, they are still stigmatised and suffer various forms of discrimination, including in education (OECD, 2019[134]). While there is little research on the difference of educational achievement between LGBTQI+ students and the rest of the population, various studies have shown that these students are greatly exposed to bullying and tend to feel unsafe in the classroom (UNESCO, 2016[135]). This phenomenon also affects heterosexual and cisgender individuals who are perceived as non-conforming to gender norms (ibid.). It highlights both a significant lack of inclusion of these people and a persisting rigidity of mainstream gender representations.

There is growing evidence that more inclusive measures at school level, such as a curriculum that contains references to gender fluidity, coupled with broad anti-discrimination laws and policies are key in fostering tolerance and the long-run socio-economic inclusion of LGBTQI+ people (Cerna et al., 2021[15]).

Special education needs

Special education needs (SEN) is a term used in many education systems to characterise the broad array of needs of students who are affected by disabilities or disorders that affect their learning and development (Brussino, 2020[136]; Cerna et al., 2021[15]). As there is no universal consensus on which disorders and impairments can cause a special education need, and each country adopts its own classification, the Project has grouped them into three broad categories: learning disabilities, physical impairments and mental disorders.

Learning Disabilities are disorders that affect the ability to understand or use spoken or written language, do mathematical calculations, coordinate movements, or direct attention (Brussino, 2020[136]; Cerna et al., 2021[15]). They are neurological in nature and have a genetic component. The severity of symptoms varies greatly across individuals because condition specific intensity differs in relation to co-morbidity. Learning Disabilities are independent of intelligence: individuals with average or high performance in intelligence tests (such as IQ tests) can suffer from one or multiple learning disabilities and as a result struggle to keep up with peers in school without support. The most common learning disabilities are: dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, and Auditory Processing Disorder (APD).

Physical Impairments affect the ability of individuals to access physical spaces due to reduced mobility or to access information that is delivered in specific ways: visual delivery for visual impairments and voice/sounds for hearing impairments. In the case of hearing impairments, the production of information via sounds can also be compromised. The severity of symptoms can vary and technological/physical aids can ensure that individuals with such impairments are able to access learning in standard school settings. Physical impairments can either have hereditary components or be the result of specific diseases or traumatic events that produce long-lasting physical consequences. The most common physical impairments are mobility impairments, visual impairments and hearing impairments (Brussino, 2020[136]; Cerna et al., 2021[15]).

Mental health. In recent years, students’ mental health and its interaction with educational systems and services have received increasing attention (Brussino, 2020[136]; Cerna et al., 2021[15]). Poor mental health can be both a consequence of lack of support for students experiencing disabilities and impairments, as well as a distinct medical condition hampering students’ academic progress and broader well-being. Due to the stigma associated with mental health conditions, many students in school suffer from mental health conditions that are long-standing and severely limiting. The experiences that children have in school can also be partially responsible for the onset of specific mental health conditions, for example due to the experiencing of bullying, social isolation and stress. The most common mental health conditions affecting children in school include:

Giftedness

Gifted students are students who have been classified as having significantly higher than expected intellectual abilities given their age, with intellectual abilities being assessed through psychometric tests of cognitive functioning and/or performance in classroom evaluations. The specific methods (tests, portfolios, observations) used to identify giftedness vary greatly across countries and within countries and so do the specific cut-offs used to evaluate giftedness. Other conceptions of giftedness encompass more liberal or multi-categorical approaches that point out the limitations of describing intelligence in a unitary way (Murphy and Walker, 2015[137]). Students can also be considered to be gifted in specific domains that are not strictly academic in nature, such as music, sports and arts.

In conversations about educational policy and issues of equity and inclusion, gifted learners tend to occupy a marginal space. This marginalisation mostly stems from the assumption that in displaying signs of exceptionality and high intelligence, learners identified as gifted will inevitably achieve educational success without additional support. In reality, however, gifted students can happen to be left behind and underserved in classrooms unable to meet their specific educational needs (Rutigliano and Quarshie, 2021[138]).

The role of socio-economic condition and geographical location

Besides the six main dimensions of diversity, the Project accounts for the role that socio-economic variations play in educational outcomes. The effect of socio-economic background is observed in most countries and education is both the result and the determinant of socio-economic stratification (OECD, 2019[91]).

The Project examines the extent to which socio-economic condition determines the outcomes and opportunities different groups of students have and the extent to which legislative and organisational features in different education systems are more or less supportive of students’ learning (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). In particular, it analyses socio-economic status as a lens through which other forms of diversity can be “distorted” and it uses it to evaluate the degree of equity and inclusivity of education systems.

Socio-economic status is not the only overarching dimension that determines the parameters through which equity and inclusion operate in education systems: the geographical dispersion of different social and demographic groups and of schools plays an equally relevant role (as discussed in the section on Contextual developments shaping diversity, equity and inclusion in school education) (Cerna et al., 2021[15]). If different social and demographic groups are located in specific areas of a country or of a city, creating classrooms that reflect the broad heterogeneity of the overall population and curricula that build upon such diversity can be challenging. Similarly, the location of school, particularly lower and upper secondary schools, which tend to be fewer, bigger and more specialised than primary schools, can have an important bearing on how inclusive an education system can be.

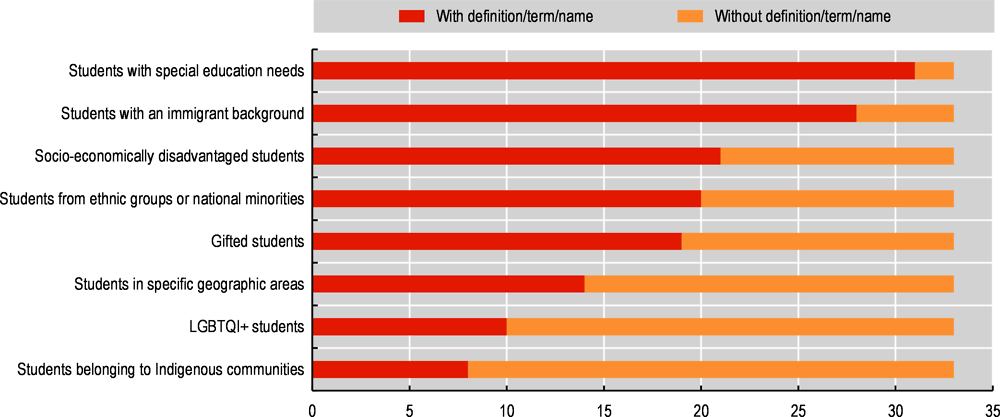

OECD education systems focus on different dimensions of diversity, depending on their national context