Overview

The economic recovery in Emerging Asia, which began in 2021, is expected to continue in 2022, although great uncertainty remains. Countries in Emerging Asia faced persistent waves of COVID-19 cases from the Delta variant in 2021 and, more recently, from the Omicron variant. The potential emergence of new variants of concern in 2022 remains a risk. Furthermore, differences in economic outlook among Emerging Asian countries have become more visible, with approaches to managing the pandemic differing starkly. Looking ahead, Emerging Asian economies are projected to expand by 5.8% on average in 2022 and by 5.2% in 2023. Growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) is forecast to be 5.2% for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2022 and 5.2% in 2023, albeit with countries in the region varying in the pace of their recoveries. Indeed, economic growth in ASEAN will range from -0.3% in Myanmar to 7.0% in the Philippines in 2022 (Table 1).

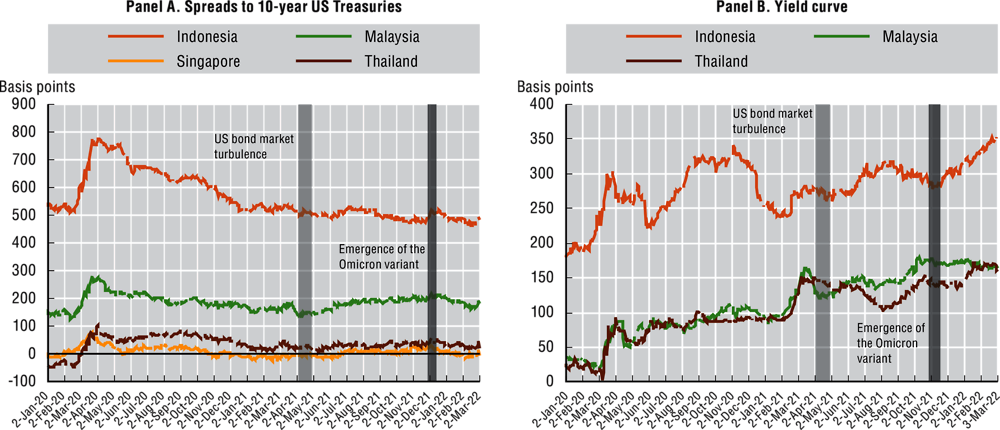

Developments on financial markets were broadly benign in 2021, as the evolution of stock-market capitalisation demonstrates. After falling sharply in the first quarter of 2020, stock-market capitalisation recovered quickly, exceeding pre-pandemic levels in most countries in Emerging Asia. As for bond markets, the increase in nominal interest rates in the United States in the first quarter of 2021 was temporary, and its effects on Emerging Asian government-bond yields were limited (Figure 1, Panel A). In parallel, yield curves widened to some extent recently, in particular in Indonesia and Thailand (Figure 1, Panel B), due to a combination of rising long-term yields and declining short-term yields. The risk of a correction in global stock prices remains high and the war in Ukraine may trigger higher financial market volatility. In addition, the increase in policy rates in the United States could quickly lead to capital outflows from Emerging Asia.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected banking sectors across Emerging Asia. In several countries, profitability levels in the banking industry deteriorated between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, although non-performing loan ratios remained mostly stable during the same period. In the first half of 2021, growth in bank lending turned negative in some countries, while deposit growth also fell back to levels that are more moderate. On a more positive note, however, stability in the banking sector remained relatively robust, with capital adequacy ratios above 15% in most countries.

The pandemic has inflicted substantial damage on labour markets in Emerging Asia. This deterioration has been particularly acute in the Philippines and Viet Nam. In terms of individual sectors across Emerging Asia, the impact has been especially heavy for the micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises. Sectors of the economy that are especially cyclical, and indeed those that rely on face-to-face interactions, have endured the gravest job losses since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis.

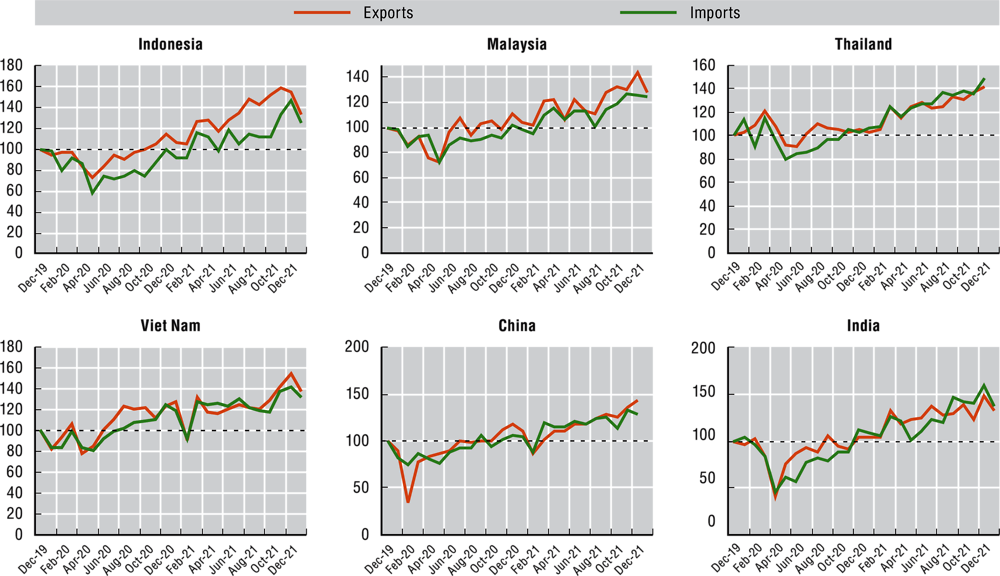

On the upside, international trade was a bright spot in 2021. Indeed, the recovery of global trade following the severe contraction of early 2020 has been remarkable. The upturn that started to take hold in the final quarter of 2020 continued into 2021, and onwards into early 2022. Importantly, trade activity has been plateauing at high levels in recent months, rather than declining. Merchandise exports in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Viet Nam, China and India have exceeded their pre-pandemic levels in recent months (Figure 2). Indeed, robust global demand for goods has driven a strong trade performance in the region, in particular for manufactured goods, chemicals and transportation equipment. However, supply disruptions affecting key sectors such as semiconductors could weigh on growth in some countries in the region. In light of the Omicron variant, and as case counts increase across Asia’s production and shipping hubs, the risk of extended dislocations to the balance of supply and demand around the globe will remain high, at least in the first half of 2022. The war in Ukraine also risks triggering further supply-chain bottlenecks.

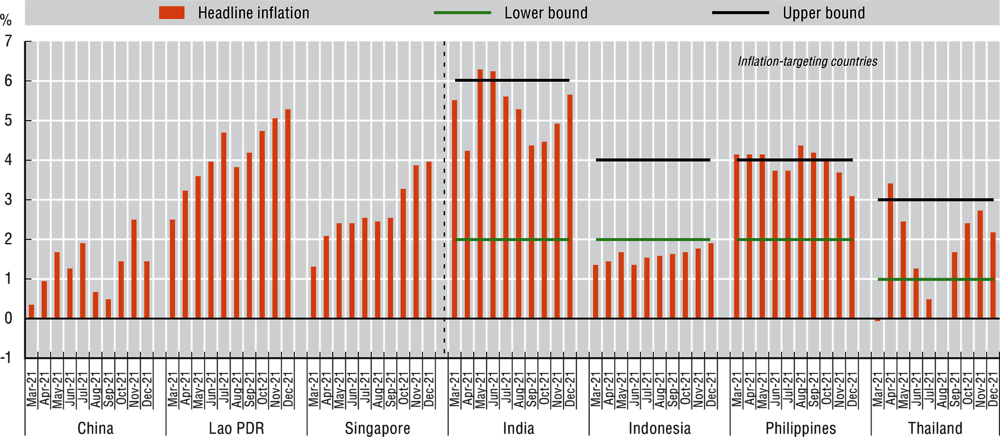

Inflation has surprised to the upside in major advanced and emerging economies, with a combination of rising energy prices, a swift rebound in demand, persistent supply-chain bottlenecks, and the comparison with weak figures from a year earlier all adding to the uptick. Higher commodity prices have led to an increase in energy prices, adding acute cost pressures in a range of industries. Indeed, headline inflation has come in above expectations for inflation-targeting countries in the region, with the Philippines, Thailand and India all experiencing headline inflation above the upper limit of their tolerance bands at various points between April and November 2021. In India and Indonesia, data for December 2021 also pointed to rising inflation, even though it remained within these countries’ tolerance bands (Figure 3). Energy prices were a key driver of inflation dynamics in 2021. Indeed, there was a steep rise as of August 2021 in the prices of energy commodities such as natural gas, oil and coal. In the countries of Emerging Asia, another factor contributing to headline inflation is the pass-through from currency depreciation.

Oil prices are expected to remain volatile throughout 2022, against a background of low levels of global inventories and declining amounts of spare production capacity. Moreover, lingering uncertainty around the war in Ukraine could push oil prices higher still.

With COVID-19 caseloads up again due to the Omicron variant, monetary policy makers in Emerging Asia have been holding rates steady until economic prospects improve durably. Many central banks in the region kept policy rates unchanged in January and February 2022. The People’s Bank of China unveiled further measures to support liquidity, including an additional cut to the reserve requirement ratio.

Central banks in the region are expected to maintain an accommodative monetary stance over the course of the year.

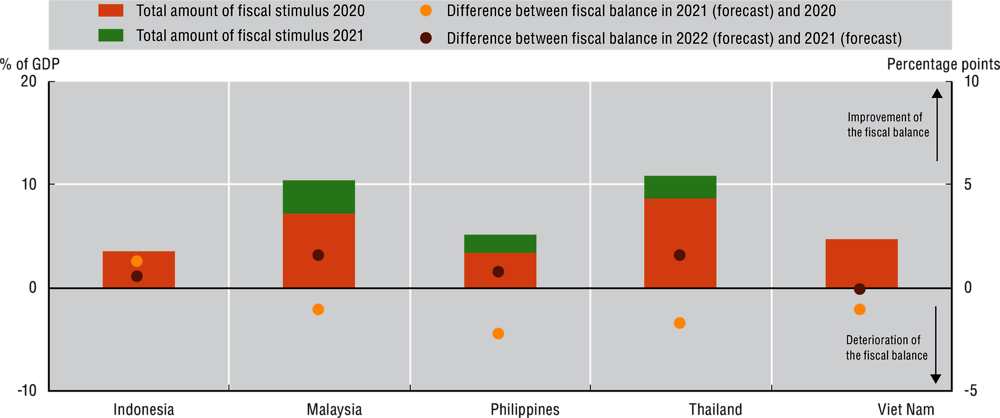

Although fiscal support programmes have continued into 2021, the outlook for public finances is gradually improving. Throughout 2021, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand rolled out extra fiscal stimulus, adding to the large amounts already deployed in 2020 (Figure 4). Indeed, fiscal deficits are still projected to exceed 5% of GDP in many ASEAN countries for the full year of 2021. As economies slowly recover, however, and notwithstanding the continuation of discretionary fiscal measures to shelter households, workers and firms from the impact of renewed COVID-19 outbreaks, fiscal deficits are forecast to narrow marginally in 2022 (Figure 4).

As regards public debt, the debt-to-GDP ratios of general governments in most Emerging Asian countries are expected to continue rising in 2022, although at a much slower pace compared to 2020. The rapid build-up of government debt at a period of low economic growth during the COVID-19 crisis has increased the need for an assessment of the sustainability of government debt.

Challenges to the Outlook

Looking ahead, the most immediate threat to the near-term growth outlook in Emerging Asia remains the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, as cases due to the Omicron variant remain elevated in the first quarter of 2022. The public health situation is nevertheless expected to improve gradually over the course of 2022, as vaccination rates increase, and as societies adapt to new protocols. Further risks to the recovery stem from longer-than-expected supply chain disruptions and higher-than-expected inflation. The war in Ukraine may also push up inflation. A normalisation of monetary policy in advanced economies, including the US Federal Reserve’s policy-rate hike of March 2022, will lead to a tightening of external financing conditions, and could increase the volatility of capital flows. Furthermore, a return to political stability in Myanmar would greatly contribute to the economic recovery in the country.

ASEAN-5

Indonesia is experiencing steady economic recovery. Real GDP growth is projected to reach 5.2% in 2022, and 5.1% in 2023. Fiscal stimulus is expected to do the heavy lifting, with the 2022 budget aiming to improve welfare for the lower-income fringes of the population. In addition, a gradual easing of travel restrictions is expected to lead to a recovery in the tourism sector. On the downside, however, the economic recovery remains subject to a very high degree of uncertainty due to the continued spread of the Omicron variant. Room for monetary manoeuvre has narrowed given the risk of capital flight, amid rising yields on US Treasuries.

Malaysia was confronted with a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases in 2021, with repeated outbreaks between February and October, and a peak in August. Real output is projected to expand at an annual rate of 6% in 2022, and 5.5% in 2023. On the upside, the negative effects of containment measures on growth should be tempered by sustained fiscal support and recovering global demand. The outlook is exposed to downside risks, however, with the fast-spreading Omicron variant and an intensifying degree of disruption to supply chains expected to slow the recovery in the near term.

In the Philippines, renewed outbreaks of COVID-19 in the autumn of 2021, followed by record-high case counts due to the Omicron variant in early 2022, have prompted new rounds of restrictions, albeit more localised in nature. The outlook is for robust growth in 2022 (+7%), while output growth is likely to remain strong in 2023 (+6.1%). A faster implementation of investment projects in infrastructure, plus the recovery in cash remittances by overseas Filipino workers constitute upside risks to the forecast, although pandemic-related uncertainties continue to tilt the risk balance to the downside.

Thailand also experienced a new wave of COVID-19 cases in the second half of 2021, with Omicron-fuelled cases surging in early 2022. Real GDP is forecast to grow by 3.8% in 2022, before accelerating to 4.4% in 2023. The continued fiscal support provided in 2021 will likely ease pandemic-related pressures on domestic demand. In addition, the reopening of borders to visitors from certain countries will support efforts to restart Thailand’s key tourism sector. On the other hand, the evolution of the pandemic remains an important downside risk.

In Viet Nam, surging COVID-19 caseloads with a record-high number of cases recorded in February 2022 constitute a headwind to economic growth, in addition to lingering supply-chain disruptions. Real GDP is expected to expand by 6.5% in 2022, and then to edge 6.9% higher in 2023. Still, the balance of risk remains tilted mainly to the downside. A marked deterioration in employment in the third quarter of 2021, when Viet Nam’s unemployment rate surged to multi-year highs, is expected to weaken household demand in the short term.

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore

Brunei Darussalam recorded weak growth for most of 2021, amid the continued spread of COVID-19 and the reimposition of containment measures. On the upside, the economy should benefit from government policies aimed at intensifying activities outside of the oil and gas sector. Real GDP is set to grow by 3.5% in 2022, followed by an expansion of 3% in 2023. Furthermore, volatile commodity prices and the uncertain medium- to long-term outlook for fossil fuels continue to cloud the outlook for exports.

In Singapore, a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases in the second half of 2021, followed by another significant surge due to Omicron, prompted the authorities to unwind the country’s remaining restrictions at a slower pace than had initially been foreseen. Nevertheless, economic growth is still set to reach 4% in 2022, followed by 3% in 2023. Furthermore, risks to the outlook are broadly balanced. On the upside, the reopening of international borders to travellers from certain countries should buttress services exports. On the downside, persistent supply bottlenecks could hamper merchandise exports.

Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar

In Cambodia, a severe resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic began in the second quarter of 2021, and case counts have been on the rise in recent weeks, fuelled by the Omicron variant. Output growth is expected to come in at 5.6% in 2022, and 6.3% in 2023. On the upside, Cambodia’s high vaccination rate should alleviate the burden on the healthcare system. Moreover, Cambodian agriculture is expected to remain resilient. Still, the balance of risks to this outlook appears to be slightly to the downside, due to the importance of foreign tourism. This is a sector with high uncertainty despite the easing of some restrictions. Furthermore, a rapid increase in flows of credit to the non-financial corporate sector risks undermining financial stability.

In Lao PDR, a rising number of daily new COVID-19 cases prompted a tightening of containment measures throughout 2021 and early 2022. On the upside, exports of goods are expected to be a bright spot in the economy, supported by increasing demand in neighbouring countries. However, the risks to the economic forecast are mostly tilted to the downside. A lower rate of vaccination coverage in Lao PDR compared to some other countries in the region means that domestic risks related to the pandemic remain high. Overall, real GDP growth for 2022 is forecast at 4.6%, followed by 4.9% in 2023.

In Myanmar, political unrest that began in February 2021, and which coincided with the sharp rise in COVID-19 cases, has derailed the recovery. Output is forecast to decline by 0.3% in 2022, before expanding by 3.3% in 2023. This outlook is subject to downside risks related to the impact of the political turmoil on consumption and investment, and to the relatively low vaccination rate in Myanmar compared to neighbouring countries. Another factor tilting the balance of risks to the downside is the persistent depreciation of the domestic currency, the Myanmar kyat, which has lost nearly 34% of its value since February 2021.

China and India

In China, the pandemic remained largely under control in 2021. Localised outbreaks led to the reimposition of restrictions in parts of the country, as the Omicron variant continued to spread. On the upside, however, exports reached record highs in 2021 and are expected to remain buoyant in the near term. Still, weak domestic consumption continues to pose a major downside risk. Meanwhile, the ongoing turmoil in the property sector, which has resulted from the financial distress of Evergrande Group and several other property developers, remains a major downside risk. China’s real GDP growth is projected to reach 5.1% in 2022, followed by another 5.1% expansion in 2023.

In India, the period from April to June 2021 saw a steep contraction in activity on the back of a severe wave of COVID-19. Subsequently, new COVID-19 cases rose to multi-month highs in early January 2022, fuelled by the Omicron variant. Overall, real GDP is projected to grow by 8.1% in 2022 and by 5.5% in 2023. On the upside, budget measures for the 2022 fiscal year, including higher infrastructure spending, could support the post-pandemic recovery. On the other hand, the evolution of the pandemic remains a significant downside risk to the outlook. The deterioration of the situation on the fiscal front is also worrisome. The financial sector is constrained by non-performing assets.

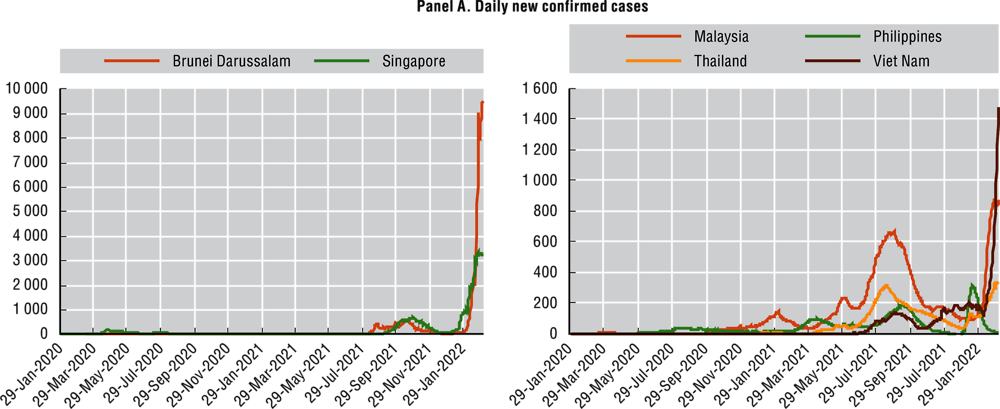

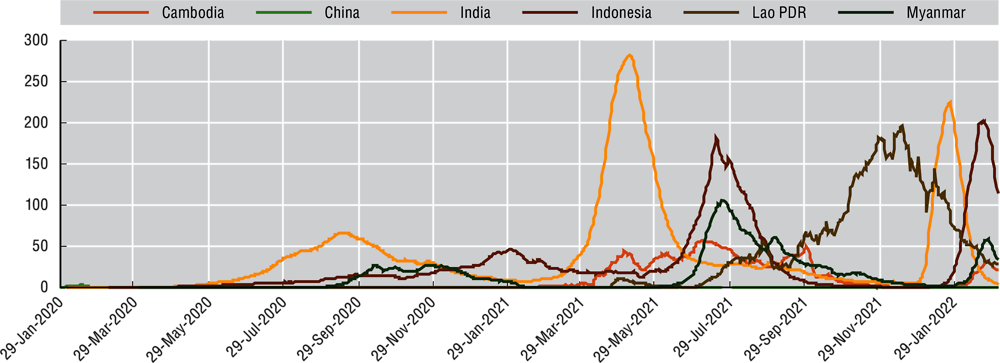

The countries of Emerging Asia are still in the grip of the pandemic. Although the numbers of daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases in some countries in the region have decreased from the peaks that they reached in the second half of 2021, recent data show increases in cases in some countries at the beginning of 2022 (Figure 5, Panel A). As of 5 March 2022, Brunei Darussalam had experienced more than 190 000 cumulative confirmed cases per million people. Meanwhile, Singapore and Malaysia saw more than 150 000 and 100 000 cases per million people, respectively. Thailand and Viet Nam had reached more than 40 000 cases per million people, and India and the Philippines had both reached more than 30 000 cases (Figure 5, Panel B).

Various challenges still hinder the effective distribution of vaccines

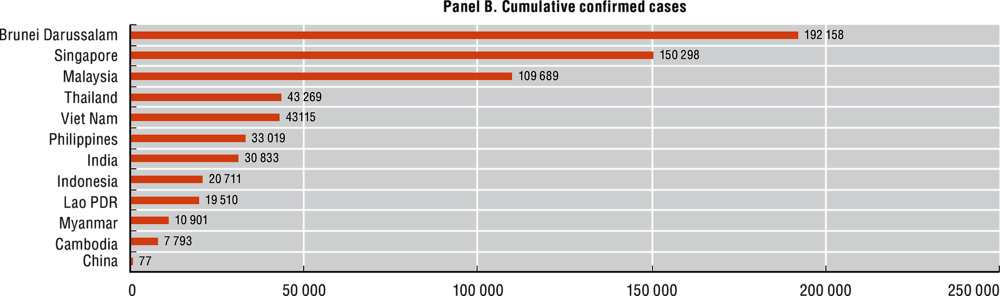

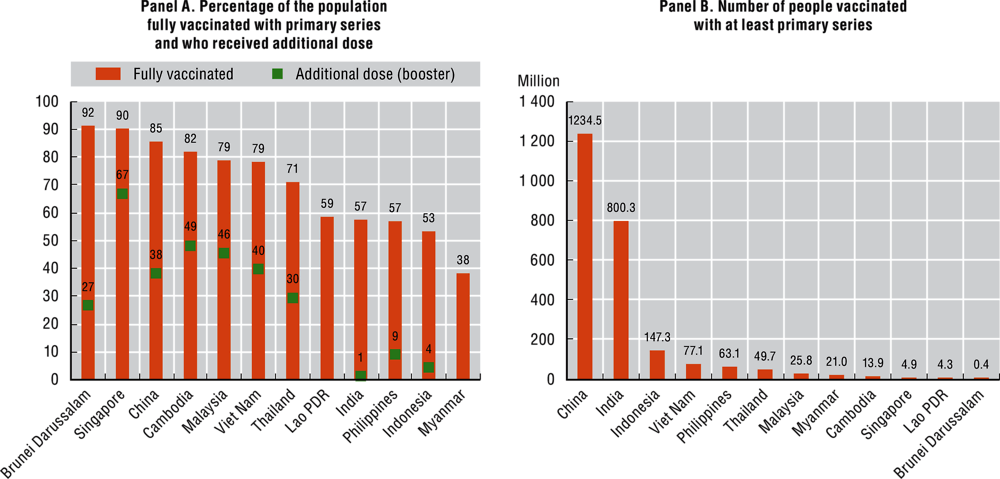

Vaccination has so far been considered effective in helping to protect people against severe disease. Although billions of doses of vaccine have been distributed in the region, and billions of people have been fully vaccinated with the primary series of doses (Figure 6, Panel B), vaccine distribution programmes are uneven across Emerging Asian countries and still face challenges in some countries. As of 5 March 2022, Brunei Darussalam, Singapore and China led the region, also among the highest in the world, in vaccine distribution, with 92%, 90% and 85% of their respective populations having received a complete schedule of the primary series of vaccine doses (Figure 6, Panel A). Elsewhere, Cambodia had attained a rate of full vaccination of around 82%, while Malaysia and Viet Nam had both reached around 79%, and Thailand had hit 71%. In Myanmar, Indonesia, Philippines, India, and Lao PDR, however, the number of fully vaccinated individuals still accounted for less than 60% of the population.

A range of challenges has hindered the distribution of vaccines in Emerging Asia. Problems regarding the vaccine supply range from upstream manufacturing issues to questions of vaccine distribution. Together, these problems constitute one of the major challenges that countries face in improving their performance. Some Emerging Asian countries will need to improve vaccine facilities, including via the provision of a stable electricity supply and the availability of cold storage. This is important in order to be able to receive and safely distribute a fuller range of vaccines, including those that require storage at an ultra-low temperature. Governments also need to ensure a smooth distribution and last-mile delivery of vaccines, especially in remote and rural areas.

From a demand perspective, it is crucial to address vaccine hesitancy. In order to address the fears and doubts of people who are hesitant about taking a vaccine, it is crucial to ensure a high degree of transparency, to strengthen vaccine outreach efforts and campaigns, and to provide clear and accurate information about the virus and vaccines continuously. Information should address questions of safety and the potential side effects of vaccines, as well as the risks of getting a severe case of COVID-19. When it comes to addressing the safety question, any potential adverse reactions following vaccination should be reported in due time. Health professionals should communicate such information in order to build trust and confidence.

International co-operation can provide valuable support to speed up vaccine distribution

It is clear that international co-operation helps to accelerate the worldwide development, manufacturing and distribution of vaccines. Notably, the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access facility (COVAX) and the Asia Pacific Vaccine Access facility (APVAX), are two examples of co-operation that include Emerging Asian countries. The COVAX initiative was launched in April 2020, and by mid-January 2022, the facility had reached its milestone of delivering a billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines to 144 participant countries, including some in Emerging Asia. However, there remains room for a further enhancement of international co-operation, particularly at the regional level. Indeed, regional initiatives have the potential to address further the large gaps that remain between countries when it comes to vaccination. More recently, some ASEAN member countries have called for an increase in support and for the specific allocation of more resources from the COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund for vaccine procurement.

Public healthcare responses are a necessary complement to vaccination programmes

Even as vaccination rates increase, preventive measures and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are still an important part of the governments’ response to COVID-19. These include wearing masks, physical distancing measures, restrictions on movement, hygiene measures, proper ventilation, and robust testing and contact tracing. In addition, medical systems and facilities also need to be improved.

Most countries have made policy adjustments in response to the emergence of the Omicron variant, and Emerging Asian countries are no exception. Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Viet Nam issued travel bans, at certain times, from countries where the variant was first identified. Countries have also extended, strengthened, or reintroduced non-pharmaceutical interventions. Most measures in response to Omicron have taken the form either of capacity limits or of vaccination requirements for particular settings. Mask mandates of some form were already widely in place. With the exceptions of Indonesia’s introduction of capacity limits, and Singapore’s expansion of vaccination requirements, non-travel reactions to the emergence of the Omicron variant have been rather muted. This is likely to be because stringent measures, such as requirements to wear masks, were already in place beforehand, and due to the apparent rarity of severe disease and death from Omicron as compared to other variants of the virus.

In addition to preventive and restrictive measures, improving medical facilities and supplies is crucial as countries seek to cope with large increases in COVID-19 caseloads. In addition to short-term responses to outbreaks of the virus, some countries have unveiled strategies aimed at enhancing healthcare capacity that will yield benefits in the longer term.

Digital tools have played an important part in the management of the pandemic

The pandemic has led to an acceleration in digitalisation. Indeed, digital health tools have played a key role in helping to manage the pandemic (Table 2), especially as restrictions on human contact have been employed in order to stop the spread of the virus. These tools have been developed by both public and private actors, and they fall into two main categories: surveillance and telemedicine. However, some tools possess functions that overlap these two categories. Broadly speaking, surveillance tools are used to track the spread of the virus in the community.

Telehealth and telemedicine could be further developed

The expansion of telemedicine will require improvements to infrastructure, such as fast and affordable wireless Internet connections. In order to reap the gains from this infrastructure, meanwhile, digital skills in the medical sector and the general population must improve. Education on how to use telemedicine applications will need to be widespread, and developers must make them as user-friendly as possible, without compromising their functionality. Care providers will need to learn how to operate the applications in order to work with both medical professionals and patients, and to be able to demonstrate to patients how to use them effectively, troubleshooting as needed. They will need training on how to make assessments via teleconference, a setting in which current patient data is often absent. In addition, legal frameworks will need to be created or updated. Some countries in Emerging Asia already have legal frameworks for telemedicine.

A gradual rise in inflation in Emerging Asia is causing some concerns. At present, inflation seems to be more contained in Emerging Asia than in advanced economies, in part due to monetary policy’s effectiveness at managing inflationary pressures. This notwithstanding, the region could see a rise in inflation as 2022 progresses, as the economy strengthens and as food prices rebound.

A sustained rise in global prices for food and fuel could alter the course of inflation

Developments in global commodities and energy markets are a big driver of inflation risks. In particular, the focus is on food and fuel prices. Notably, food accounts for the largest weighting in the consumer price index (CPI) for many economies, including those in Emerging Asia. Moreover, apart from their direct impact on headline inflation, food and fuel also have indirect effects, as their prices tend to affect the cost of other goods and services.

Having lost substantial ground in 2020, global fuel prices soared to multi-year highs in 2021, following sharp cuts in supply from oil-producing countries, and then a recovery in demand. Likewise, food prices have been picking up some steam. In the first half of 2021, food prices were generally fairly contained in Emerging Asia. However, upward pressure on prices in global markets is likely to feed through into domestic prices if it continues. Indeed, the latest data for January 2022 point to rising food prices in India, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Furthermore, disruptions to global supply chains could also underpin faster inflation, exacerbated by rising shipping costs. In addition, the war in Ukraine is likely to compound inflationary pressure. Prices for agricultural commodities such as wheat, sunflower oil and corn, for which Russia and Ukraine are major producers, have risen because of supply risks. Global food price inflation is anticipated to pass through to higher domestic prices in Emerging Asian countries.

A reversal in the monetary-policy stances of advanced economies poses another risk

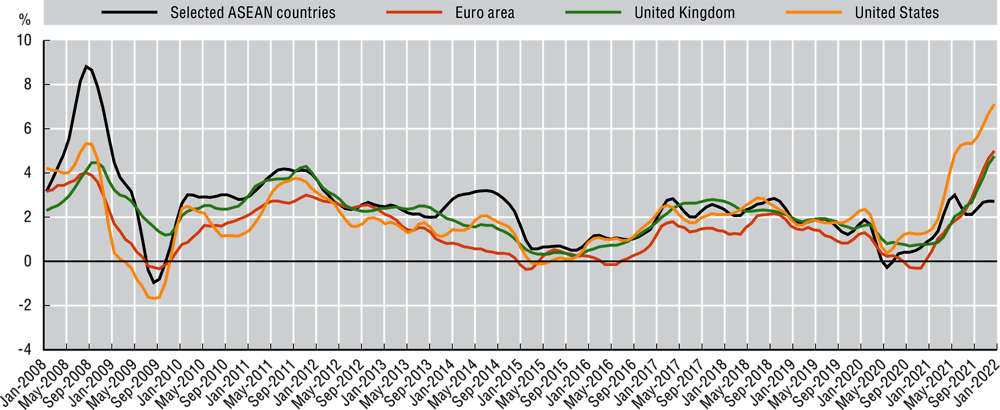

The trajectory of inflation in advanced economies, and its possible implications for international capital flows, constitutes another source of apprehension. As shown in Figure 7, headline inflation rates in the euro area, the United Kingdom and the United States have risen sharply to multi-year highs since the start of 2021. The possibility of inflation overshooting expectations, a phenomenon that was observed during previous financial crises, also cannot be discounted over the coming quarters. However, inflation in selected member countries of ASEAN appears for now to be more moderate than in the advanced economies.

Vulnerable households are likely to feel the pinch of inflation

At a time when labour markets are still reeling from the impact of the pandemic, a successful anchoring of inflation is of critical importance. The impact of the pandemic in Emerging Asia included income losses, a fall in working hours for those in employment, and a fall in labour income in 2020, before income-support measures were implemented. Furthermore, job destruction has disproportionately affected low-paid and low-skilled jobs. Indeed, published data for 2021 indicate that the picture for wages and earnings in the region remains grim. Policy makers should remain mindful of the interactions between wages and inflation, even if wage pressures currently appear to be low in Emerging Asia. Moreover, there is evidence of growing wage inequality in some countries the region.

Buoyed by rising input costs such as base metals, the robustness of property prices in Emerging Asia is another point of concern. Indeed, property prices are reported to have increased considerably across major cities in Emerging Asia. While this indicates favourable prospects for the sector, it will also fuel inflation, further tightening the budgets of households that are already experiencing economic difficulty and contending with lower real earnings.

Imbalances in supply and demand have affected global logistics and the production of semiconductors

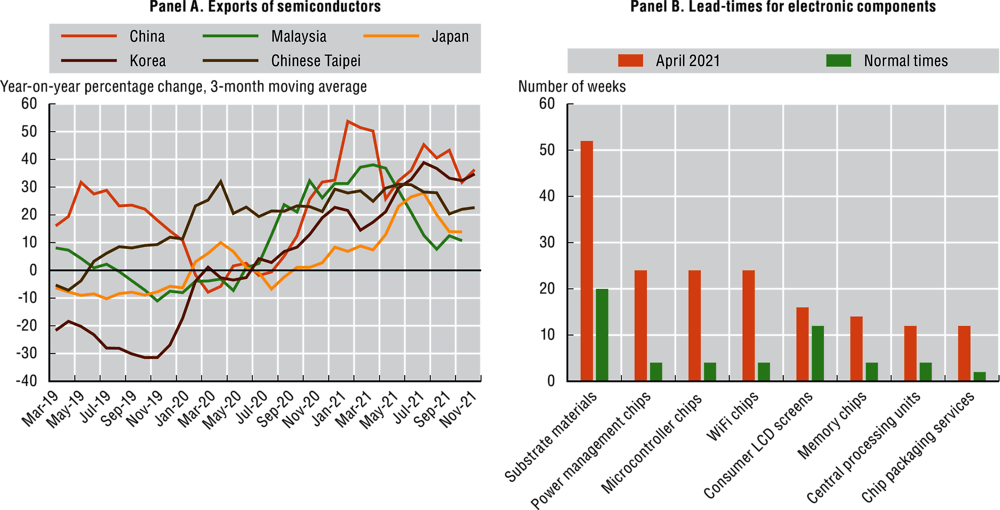

Imbalances between supply and demand have affected several key industries, including the global logistics sector and the production of semiconductors. One of the major factors behind these bottlenecks is the rise in demand for semiconductors, which has been driven by structural changes triggered by the shift to remote work. Major manufacturers such as China, Malaysia, Japan, Korea and Chinese Taipei saw their exports of semiconductors surge in the first half of 2021 (Figure 8, Panel A). Meanwhile, measures to contain COVID-19 disrupted production in major chip-manufacturing hubs, as well as in packaging sites in countries such as Korea, Malaysia and Viet Nam. Due to imbalances between supply and demand, the lead times for various electronic components lengthened considerably in 2021. For instance, lead times for power management and microcontroller chips lengthened to a minimum of 24 weeks in April 2021, compared to four weeks in normal times (Figure 8, Panel B).

Increases in the price of commodities to above their pre-pandemic levels, in particular for energy and metals, represents another triggering factor.

Finally, logistical disruptions have emerged in the transport sector, and in container shipping in particular. The brisk rebound in trade in merchandise as of the second half of 2021 coincided with a shortage of shipping containers, as the spread of the Delta variant to many Southeast Asian countries exacerbated bottlenecks in the supply chain. On top of that, waiting times at ports increased due to high import volumes, containment measures at port facilities, and labour shortages, with measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 affecting the mobility of migrant workers. As a result, shipping transit times increased, and transport costs from China to ports in the United States and Europe rose sharply.

Supply-chain disruptions could weaken output growth and affect consumers in Emerging Asia

Supply-chain disruptions could reverberate through Emerging Asian economies and weaken output growth. Indeed, manufacturing sectors affected by severe shortages appear to have been reporting weaker output dynamics since May 2021. For instance, the total production output for integrated circuits declined substantially in Thailand in June, and in Malaysia in July. Other sectors that rely on electronic equipment, such as the production of passenger cars, also reported lower output. In Malaysia, for example, the production of passenger cars declined by nearly 17.8% in April 2021 compared to the previous month.

At the consumer level, shortages of certain products have triggered rationing and cost-push increases to prices, as discussed in the previous section. These shortages may be partially responsible for the recent spike in inflation for consumer durables in some countries in the region. Prices of oil, natural gas and commodities had already firmed up since the second half of 2020, while higher transport costs have added further to price pressures. Prices of household durable goods rose in November 2021 in some countries in Emerging Asia, most notably in India, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Singapore.

As of early 2022, there were some signs that stresses in supply chains were easing. However, the balance of risks is mostly tilted to the downside. The concern is that the Omicron variant of COVID-19 could delay further improvements. Additional supply-chain disruptions and slowdowns may occur in the near term, as cases of the fast-spreading variant are reported across major production and shipping hubs in Asia. In particular, and against the backdrop of China’s zero-COVID strategy, potential lockdowns in areas of the country in which large-scale production facilities are concentrated, such as the lockdown of the city of Shenzhen in mid-March 2022, could imply higher producer prices in the coming months. Furthermore, the war in Ukraine could add further upside pressure on oil and metal prices. On the other hand, the imbalance between supply and demand for semiconductors is likely to ease gradually in 2022 as pandemic-related risks recede, and as investment in semiconductor facilities increases.

The current fiscal environment in Emerging Asia is challenging

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the pressure on public finances due to supportive measures such as cash-transfer packages and higher healthcare budgets. As expected, widening deficits led to a significant rise in governments’ stock of debt after the outbreak of the pandemic. The public debt of Emerging Asia (excluding Brunei Darussalam) increased by an average of 15.5% from 2019 to 2020. Debt levels are forecast to have risen by the end of 2021. Fiscal deficits widened sharply in 2020 in all countries in Emerging Asia, and they are expected to have deteriorated further in 2021 in many countries. In addition, a comparison with the pre-pandemic period 2010-19 shows that both debt levels and fiscal deficits deteriorated markedly in 2020 and 2021 compared to that period.

As levels of sovereign debt have increased sharply in Emerging Asia, the question of the sustainability of this debt has come to the fore. Fiscal frameworks, which comprise fiscal rules, fiscal institutions and budgetary procedures, are an important tool both for supporting fiscal sustainability and for increasing the predictability of public policies. Most countries rely on a combination of numerical and procedural rules. Policy makers should assess the advantages and drawbacks associated with different types of numerical and non-numerical fiscal rules. Table 3 summarises some of these advantages and drawbacks.

The monetary environment is changing due to the pandemic

In order to keep the system as liquid and accommodative as possible, and to avert a significant loss in market confidence, Emerging Asian economies have implemented a mixture of monetary policies. These include direct lending and forbearance, loan guarantees, loan reclassification and restructuring, and adjustments to interest rates and reserve requirements.

In parallel, there seems to be a consensus that natural rates of interest are trending downwards in developed and developing economies alike. Emerging Asian economies are no exception, although there are also cases in the region where the trend is on the rise. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand experienced a decline in their real natural rate of interest over the past two decades. This decline was already in progress for these countries in the early 1990s.

In the current fiscal and monetary environments described above, policy makers in Emerging Asia should consider a range of options for managing public debt.

Depending on the national context, swap agreements provide an additional tool for renegotiating the terms of debt. In the process of renegotiation, payments can be earmarked for a particular objective. The debt-for-policy swap is an umbrella term for a type of financial swap where a sovereign issuer accepts debt relief in exchange for participation in a mandated policy action. Under such a scheme, the creditor buys the debt of a participating debtor country in exchange for a commitment to channel payments directly into achieving policy goals selected by the creditor.

Debt-for-climate swaps have the potential to provide debt relief for Emerging Asian economies while simultaneously promoting climate-change mitigation or disaster prevention. These swaps may be particularly useful for island nations in Asia, which are some of the most exposed in the world to risks related to climate and natural disasters. Debt-for-equity swaps are another variation on this arrangement, and are used in both the public and private sectors. In this type of deal, a share in a public or private company is exchanged for an equivalent amount of debt. This provides a mutual benefit, both to the debtor (debt relief and investments), and to the creditors (partial recovery of debt beyond what would be expected otherwise).

In the same way, a debt buyback, wherein debtors offer a lump-sum payment in exchange for the cancellation of the remainder of the outstanding debt, can also be an option for some countries. Creditors are more likely to accept these terms when it appears that the lump-sum payment is the best possible outcome for them with respect to the debt in question.

With the encouragement of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, the Group of Twenty (G20) countries launched the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which aims to lessen the debt burden of low-income and least-developed countries, as they recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The DSSI suspends debt-service payments (both principal and interest), and provides emergency relief for eligible countries.

Prevailing conditions present significant opportunities for policy makers. First, there is an opportunity to increase the efficiency of how the financial resources that are available in the system are put to use. Second, there is an opportunity to harness other financing modalities in order to facilitate recovery from the pandemic.

Green bonds herald a number of advantages for governments seeking financing

One potential upside of bond and security instruments that are in line with environmental, sustainability and governance (ESG) principles is the guarantees they offer about how the funds are used. Green bonds that focus on environmentally responsible projects are used widely, and are one of the most promising instruments for financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Another advantage of green bonds is their capacity to spread the cost of funding the mitigation of climate change across several human generations. This makes green bonds particularly suitable for raising money for environmentally friendly investments, both public and private. Green bonds are also a good option for attracting a broad spectrum of institutional investors.

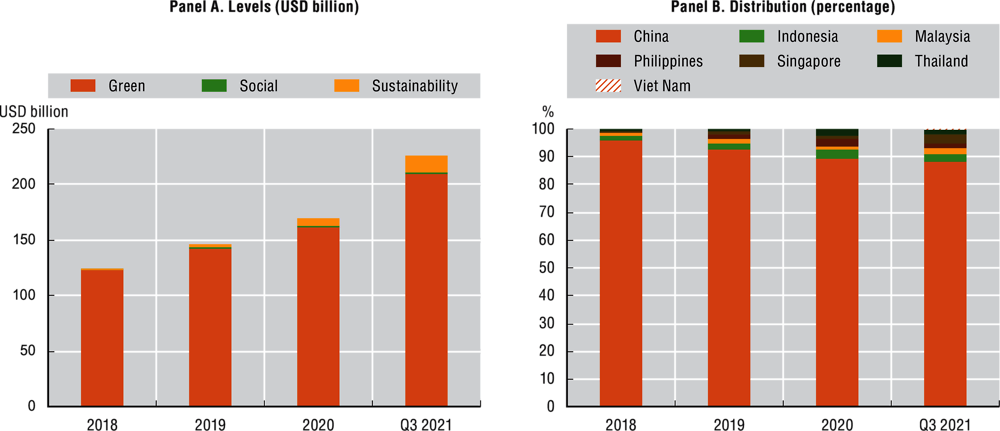

Recourse to ESG-themed bonds is not new in Emerging Asia. In terms of market size, data as of the third quarter of 2021 showed that the combined value of outstanding green, social and sustainability bonds in the seven economies for which data were available is more than USD 225 billion (Figure 9, Panel A), which is still a fairly small amount. In 2020, these bonds accounted for about 0.9% of the total for all outstanding bonds (i.e. local and foreign-currency bonds combined). Nevertheless, the stock of this kind of debt grew at an encouraging pace of about 24% a year in compounded annual growth terms between 2018 and the first three quarters of 2021, even when pandemic bonds are excluded. China still accounts for the highest share of outstanding ESG bonds, but the other economies in the region are gradually catching up (Figure 9, Panel B).

Various policies are needed to address existing barriers to the development of the green bond market

In order to develop green bond markets, it is important to address barriers for both issuers and investors. In particular, a broad pool of investors is crucial for ensuring the successful development of sovereign green bond markets and making sure that yields respond accurately to fundamentals. Hereafter, Table 4 summarises existing barriers, together with potential policy options to overcome these obstacles, both on the supply side and the demand side.

External support and private placements could be leveraged to overcome complexity and cost

In order to reduce the cost of external reviews, and to streamline the reporting process, governments in Emerging Asia should take advantage of the support that they can get from organisations and experts such as development banks, structuring advisors and stock exchanges. Notwithstanding the longer-term desirability of a generalisation of public issuance in order to foster liquid markets, governments could also potentially cut costs by envisaging private placements of green bonds, selling them directly to a limited number of investors. In addition to cutting costs, private placements can also speed up the issuance of a bond. The Indonesian government, for example, turned to private placements in April 2020 to finance its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regulatory challenges relating to the management of proceeds from green bond issuance need to be addressed

Sovereign issuers should plan in advance for how they will manage the proceeds if they do not expect to invest them immediately. Moreover, there have to be safeguards to track the allocation of proceeds, and to make sure that the same eligible green project does not get listed more than once. In making sure that the net proceeds from a green bond flow into a suitable budget allocation, it is important to consider whether governments should open a special account to manage the funds that they raise from green bonds. Although there is currently no consensus on the best practice in this regard, setting up a special account for the management of net proceeds may streamline the allocation process and enhance investors’ confidence.

Clear and standardised definitions can reduce the risk of greenwashing and facilitate cross-border transactions

One of the bottlenecks constraining the development of markets for green bonds in Emerging Asia is the lack of an overarching framework to define and classify these assets. At present, the market for green bonds in most countries in the region is generally not subject to government regulation. This presents a challenge, as the risk of greenwashing is arguably higher in countries that lack a clear regulatory framework for green bonds. Furthermore, the standardisation of definitions for green bonds is essential in order to facilitate cross-border transactions in Emerging Asia, albeit without resorting to a heavy-handed approach. Imposing overly detailed standards has the potential to increase issuance costs, so standards should allow issuers sufficient room for flexibility in order to respond to the different constraints that they may face.

Increasing the supply of sovereign green bonds, in particular from sub-national entities, is equally important to attract more institutional investors

There is scope in Emerging Asia for more sovereign issuers to launch green bonds. In so doing, they would signal their support for the market, and would contribute to its deepening by increasing the supply of green bonds in the medium term. Arguably, the issuance of sovereign green bonds could send a strong signal that governments are committed to supporting the market for this kind of asset by providing opportunities to invest in a broad range of projects, and at relatively low yields. In turn, a deeper market would create favourable conditions for a decline in yields. Moreover, sub-national entities (e.g. cities, regions, provinces and public utilities) could also issue green bonds in order to finance investments in green public infrastructure.

There are various policy options for increasing the participation of domestic institutional and retail investors in green bond markets

Institutional investors may face specific constraints that can limit their investment options. For instance, investors have to work within a framework of restrictions regarding the currencies that they can invest in and the size of the deals that they can make. Such limits can affect their capacity to invest in green bonds. As they seek to make their offerings as attractive as possible, sovereign issuers of green bonds need to strike a careful balance between the duration of the projects that they wish to finance, and the appetite of investors. For instance, longer tenors tend to attract insurance companies and pension funds that seek to match their long-term liabilities with long-term assets. Reputational risk could be tackled through penalty mechanisms in case the issuer does not fulfil its environmental obligations. In addition, governments may apply tax incentives to green bonds. They can also hold regular investor roadshows to promote participation in green bond markets, both within the region and beyond.

Social and sustainability bonds can complement green bonds in financing a sustainable recovery

Social and sustainability bonds are similar to green bonds. Social bonds finance projects that aim to address a specific social issue, or to achieve positive social outcomes. Meanwhile, sustainability bonds are bonds that raise funds for undertakings that have green or social aspects. The outstanding value of social and sustainability bonds is still marginal by comparison with green bonds. However, available data show a rising tide of interest in these bonds in Asia following the emergence of COVID-19 in early 2020. Even if pandemic bonds are excluded, the average monthly issuance of social and sustainability bonds in Emerging Asian economies for which data are available rose more than five-fold from 2019 through to the third quarter of 2021. Among the economies of Emerging Asia, China, Malaysia and Singapore are leading the way in terms of new issuance.

Social and sustainability bonds come in different shapes and sizes, and pandemic-oriented bonds increasingly now constitute one type of social bond among others. Their proceeds can finance the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic and help mitigate its economic and social repercussions. Governments in Emerging Asia have also begun to explore the potential of social bonds to finance public spending related to COVID-19. In April 2020, the Government of Indonesia issued its first pandemic bond.

Other types of social or sustainability bonds include education bonds, health bonds and gender bonds. As their names suggest, the proceeds of such bonds flow into projects in the education and health sectors, or into efforts to promote gender equality and the empowerment of women. Water bonds, meanwhile, fund improvements to the quality and scope of water infrastructure. In Emerging Asia, multilateral institutions such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) are among the active issuers of these bonds. Moreover, there are promising signs that other stakeholders are increasingly willing to participate in this market. In the case of gender bonds, for example, a number of non-sovereign, non-multilateral issuances followed in the wake of the gender bond that the ADB issued in 2017.

As with green bonds, various institutional and regulatory barriers hinder the further development of social and sustainability bonds. Some Emerging Asian countries already have dedicated frameworks, but the adoption of common standards has been relatively slow, and the lack of a standardised set of metrics to measure their impact has led to concerns about “social washing”, or so-called “pink washing”. For the social and sustainability bond markets to grow further, more issuance by sovereign and sub-sovereign entities is essential. Additionally, social and sustainability bonds would benefit from a broadening of the investor base.

Offshore debt issuance can be an option under certain circumstances

The offshore bond market has significant potential to close funding gaps. Indeed, there is scope for Emerging Asia’s policy makers to take advantage of the much bigger offshore investor base, which contains many investors that are keen to invest in ESG-linked instruments. In addition, ESG instruments can provide an additional dimension to efforts to recycle Asia’s sizeable savings pool within the region.

In order to capitalise on this opportunity whilst mitigating debt-servicing risks, Emerging Asia can bolster the capacity of the cross-country systems that are already in place. One important facility in this respect is the Multi-Currency Bond Issuance Framework (AMBIF), which the ASEAN+3 grouping (including China, Japan and Korea) put together in order to make the recycling of the region’s savings more efficient and inclusive, but without overlooking individual countries’ peculiarities. Recent data show that there have been 12 issuances under the AMBIF, and that these are denominated in seven different local currencies.

It is worthy of note, moreover, that smaller economies in Emerging Asia can also leverage strong bilateral relations in order to gain access to offshore markets.

Multilateral institutions and development banks will continue to have a big role to play in helping emerging economies to raise funds and to ensure the sustainability of their debt as they recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Their assistance is particularly critical for low-income economies with very tight fiscal situations and highly under-developed domestic capital markets. Indeed, multilateral institutions and development banks have the potential both to provide risk-management solutions and to leverage their high credit ratings in order to reduce the cost of borrowing for their clients, both public and private. Multilateral institutions can also intermediate syndicated loans.

It is impossible to rule out the recurrence of pandemics or other similar catastrophes. Considering their potential impact, hedging the associated risks is, therefore, critically important. Insurance-linked securities (ILS) can offer insurance companies and governments some respite in challenging situations, by transferring a portion of these risks to investors. Below, Table 5 lists various ILS that could be used to cope with pandemic-related risks.

Pandemic bonds are one of the kinds of ILS mechanisms that are worthy of consideration over the coming years. They are similar in structure to catastrophe bonds, and are distinct from pandemic social bonds. A prominent example of pandemic bonds is the Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF) bond that raised USD 325 million when it was issued in 2017.

Another relevant and related initiative is risk pooling. In this mechanism, different stakeholders contribute to a fund. The list of contributors typically includes insurance companies, and sometimes government entities. Instruments like catastrophe bonds or pandemic bonds are issued in order to generate revenues. Coupon payments are then paid on a regular basis, as long as the underlying event does not occur. One good example is the Indian insurance regulator’s proposal in 2020 to create an Indian Pandemic Risk Pool. Pandemic bonds would back up this pool, and it would have a multiple-trigger mechanism in order to respond both to epidemics and pandemics.

Another ILS option is the mortality swap, which is an agreement to exchange one or more cash flows in the future, based on the outcome of at least one index measuring survival rates or mortality, chosen at random. Mortality swaps bear considerable similarity to reinsurance contracts, as both often involve swaps of anticipated payments for actual payments (or claims), and both may be used for similar purposes. Mortality swaps are not insurance contracts in the legal sense of the term, and therefore are not affected by some of the distinctive legal features of insurance contracts. They can typically be arranged at a lower transaction cost than a bond issuance, and can be cancelled more easily. They are also more flexible, and they can be tailor-made to suit diverse circumstances.

A further variation on this theme are extreme mortality bonds, which hedge against an insurer or reinsurer becoming insolvent. They work on the premise that a jump in mortality rates adversely impacts the amount and timing of the death benefits that an insurer or reinsurer would have to pay out. Extreme mortality bonds are short-term tradeable securities, with a payout structure that is explicitly linked to a mortality index. The main focus of extreme mortality bonds is pandemic outbreaks. As such, extreme mortality bonds are designed to cover the risk of mortality or the specific risk of premature death.

Finally, another option for hedging the losses that can emanate from financially costly pandemics presents itself in the form of pandemic futures and options. In a related field, and by way of background, the emergence of markets for weather-related derivatives (i.e. weather futures and options) is a remarkable development, because these instruments target risks that are not market risks, but which, on the contrary, are relatively uncorrelated with the fluctuations of the stock market. Pandemic derivatives could be envisaged along similar lines to exchange-traded weather derivatives, which are usually linked to widely followed measures such as temperature and rainfall. Bilateral deals traded over the counter could be tailor-made for specific pandemic-related risks.

Exploring potential options further, sovereign catastrophe risk pools could provide a mechanism for Emerging Asian governments to enhance their financial preparedness against pandemic risks, by pooling risks into a single, more diversified, and less risky portfolio. Catastrophe risk pools also allow participating countries to partially retain risk through joint reserves or capital, and to transfer excess risk to the re-insurance and capital markets. Another advantageous feature of a risk pool is that profits that accrue to the pool during years with fewer disaster events can be retained within the pool, rather than being distributed to various stakeholders. Four sovereign catastrophe risk pools exist currently, including one in Southeast Asia. The four pools are the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), the African Risk Capacity (ARC), the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI), and the Southeast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility (SEADRIF).

A model could be envisaged whereby countries enter into an insurance contract with an over-arching risk-pooling facility, and pay a premium to gain access to rapid liquidity in the aftermath of a pandemic in the form of bridge financing. In order to avoid cross-subsidisation of premiums among countries, the premiums that each participating country would pay should have a basis in the level of risk that it brings to the regional risk pool. The participation of sub-national entities (i.e. municipalities) in this platform could also be considered.

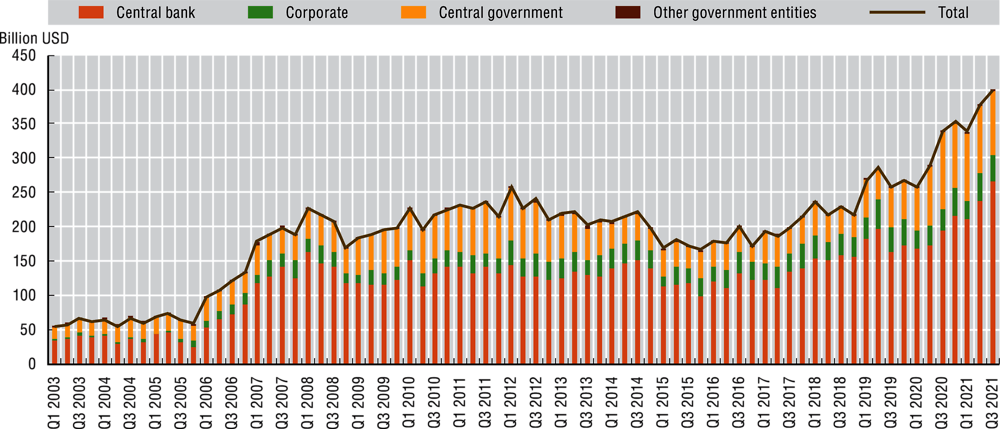

Bond issuance in Emerging Asia has grown significantly over the past two decades. The amount of local-currency bonds issued in the member countries of ASEAN for which data are available increased to approximately USD 399 billion at the end of the third quarter of 2021, from around USD 55 billion in early 2003 (Figure 10). As the bond market has grown, issuance by governments, government-affiliated entities and corporations has also progressed.

Aggregate data that depict a growing bond market do, however, mask considerable diversity across the different economies of Emerging Asia. Bond markets account for a larger share of GDP in countries with more advanced capital markets such as Malaysia and Singapore. In the third quarter of 2021, this amounted to 125.2% in Malaysia and 115% in Singapore. Bond markets are also relatively large in Thailand, at around 86% of GDP. In contrast, bond markets in Indonesia and Viet Nam remain very small, equating to less than 30% of these countries’ GDP as of the third quarter of 2021.

There is scope for reducing barriers to bond market participation in Emerging Asia

At present, the goal of broadening the participation of issuers and investors in Emerging Asia’s bond markets faces a range of barriers, and these differ substantially among countries. For instance, in countries whose bond markets are at an early stage of development, basic institutional and legal frameworks are still in the process of being established. In these markets, levels of investor protection, and of transparency with regard to tax processes, remain insufficient. In other countries with more advanced capital markets, there is still scope to diversify the investor base. One area for improvement in such countries is the level of liquidity in secondary markets.

Regional initiatives have played an important role in the development of Emerging Asia’s bond markets

In order to enhance the development of local financial markets across the region, a number of multilateral initiatives were established in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 (Table 6). As early as September 2001, ASEAN+3 policy makers worked together with domestic credit rating agencies within the region to form the Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia (ACRAA). In 2003 and 2004, meanwhile, the Executives’ Meeting of East Asia-Pacific Central Banks (EMEAP)1 established the first and second Asian Bond Funds. The aim of these funds was to support the development of regional bond markets, and to retain some of the region’s foreign currency reserves in local investments. In launching the Asian Bond Market Initiative (ABMI) at the end of 2002, the ASEAN+3 countries sought to develop local-currency bond markets, and to promote regional financial co-operation and integration.

Again within the context of the ABMI, other initiatives include the establishment by ASEAN+3 of a multi-currency bond-issuance framework. The purpose of this framework is to support intra-regional transactions via standardised processes for the issuance of bonds and notes, and for investments more generally. It has achieved this by creating common market practices, by instituting a common document for submission, and by setting out transparent issuance procedures in the implementation guidelines for each participating market. In May 2021, the 24th meeting of ASEAN+3 finance ministers and central bank governors acknowledged the continuing progress of the ABMI under its medium-term roadmap for 2019-22.

Digital and financial literacy are increasingly relevant policy areas

Given the rapid digitalisation of financial services, financial literacy has become increasingly intertwined with digital literacy over the past few years. While technology can certainly broaden the reach of financial services, it also tends to increase the scale of the risk that users need to understand and be mindful about. Moreover, as with other forms of literacy, there are notable “divides”, such as between men and women, urban and rural residents, and small and large firms. This is largely due to disparities in access to digital tools, and in people’s abilities to use them.

National authorities in Emerging Asia are aware of the challenges at hand, and financial literacy has been pursued vigorously in the region, with authorities gradually integrating the digital component into their frameworks. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore are already implementing strategies for financial education, all of which are stand-alone projects. In Malaysia and Singapore, the frameworks have been in place since the early 2000s. The strategies to enhance digital financial literacy in Emerging Asia are generally multi-pronged, and they tend to take effect through various media platforms.

In order to make policy interventions more inclusive, it is crucial for national authorities to identify gaps by systematically collecting data, and by incorporating this information into the design and execution of their programmes.

Financial stability is a critical prerequisite for the use of market-based instruments. The global financial crisis of 2007-08 and its aftermath led to a new emphasis on macroprudential policy as a means of addressing systemic risk. Indeed, it became clear after that crisis that microprudential policy alone could not cope with system-wide financial distress. In light of adverse developments in the build-up to both the Asian and the global financial crises, authorities in Emerging Asia enacted a range of macroprudential measures to ensure the stability of the financial system as a whole, to increase banks’ resilience to shocks, and to reduce the build-up of systemic risk.

Macroprudential policy must preserve financial stability in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis

The COVID-19 outbreak has been the first test for many countries of how changes in their macroprudential framework would perform during a severe negative shock. Monetary authorities in Emerging Asia responded differently during the COVID-19 shock compared to two other recent shocks, namely the taper tantrum and the commodity-price shock. During the first half of 2020, which corresponded to the height of the COVID-19 shock, a number of Emerging Asian countries temporarily eased some macroprudential constraints that could have impeded the provision of credit to the economy. For instance, Malaysia and India temporarily relaxed liquidity requirements, while Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand loosened other types of macroprudential measures.

The stabilisation of cross-border capital flows may gain a new dimension in the aftermath of the pandemic. The divergence in economic performance between advanced and emerging economies in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis is likely to lead to an increase in the volatility of capital flows for most Emerging Asian countries. Macroprudential measures can affect the nature and volume of cross-border capital flows by influencing the composition of balance sheets in the banking system, both in terms of assets and of liabilities.

Finally, the COVID-19 crisis highlights the importance of regional and international co-operation in the area of macroprudential policy. Policy makers in Emerging Asia and around the world intervened in a relatively synchronised way to mitigate the impact of the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, by exploiting the flexibility of existing regulatory frameworks. Given the cross-border spillover effects of domestic macroprudential measures, which are potentially amplified by frictions in the banking sector, regional or international co-ordination of macroprudential policy may be all the more necessary.

References

ADB (2017), The Asian Bond Markets Initiative: Policy Maker Achievements and Challenges, Asian Development Bank, Manila, https://doi.org/10.22617/TCS178831-2.

ADB (n.d. a), COVID-19 Policy Database, Asian Development Bank, Manila, https://covid19policy.adb.org/ (accessed multiple times between June 2021 and March 2022).

ADB (n.d. b), AsianBondsOnline, Asian Development Bank, Manila, http://www.asianbondsonline.adb.org/ (accessed multiple times between June 2021 and December 2021).

IMF (2021), World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021 Edition, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/October.

OECD (2022), Inflation (CPI) (indicator), https://data.oecd.org/price/inflation-cpi.htm (accessed on 7 March 2022).

OECD (2021), Economic Outlook No. 110, December 2021, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=EO (accessed on 4 March 2022).

Our World in Data (2022), Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) database, https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 6 March 2022).

Schaechter, A., T. Kinda, N. Budina and A. Weber (2012), “Fiscal Rules in Response to the Crisis – Toward the ‘Next-Generation’ Rules. A New Dataset”, IMF Working Papers, No. 12/187, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12187.pdf.

Ting-Fang, C. and L. Li (2021), “How the chip shortage got so bad – and why it’s so hard to fix”, Nikkei Asia, 16 April, Tokyo, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-Spotlight/How-the-chip-shortage-got-so-bad-and-why-it-s-so-hard-to-fix.

Note

← 1. EMEAP includes central banks from the following countries: Australia, China, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.