1. Key Policy Insights

While Japan has successfully contained the number of infections, the pandemic has proved difficult to bring under control. Successive waves of infections induced the government to introduce states of emergencies, which became more targeted over time. Confinement measures and behavioural changes kept transmission rates relatively muted, but at some near-term cost to the economy. After the initial shock, the economy has struggled to regain its footing, even though fiscal and monetary policy reacted quickly and robustly to offset the impact on households and businesses.

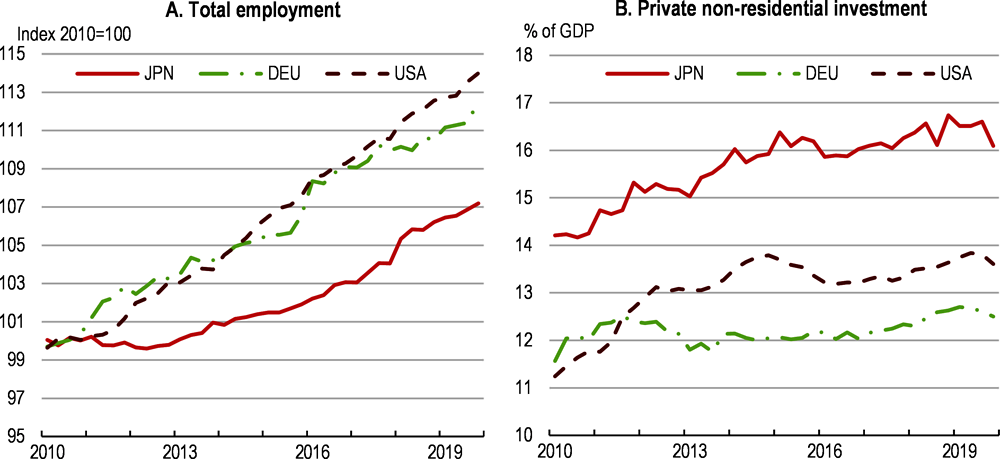

The pandemic hit when the effects of past structural reforms to boost employment and to adjust regulation to improve the business environment were starting to show. Despite the headwinds created by an ageing and shrinking population, the level of employment had been rising as elderly individuals remained in work and more women participated (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Business fixed investment had strengthened somewhat and productivity growth, which had long been anaemic, showed signs of picking up (Panel B). This progress was set back as the pandemic caused output and employment to fall and unemployment to rise. The pandemic also exposed weaknesses, some of which have been long-standing concerns. For example, labour market duality meant that despite aggregate income gains income inequality did not decline, although poverty rates were diminishing slowly, and low-paid and temporary workers were more exposed to the downturn. Other weaknesses, such as the difficulties households, businesses and government experienced in adapting to remote working had heretofore been less in focus. The government reaffirmed the commitment to furthering structural reforms, with a greater emphasis on the digital transformation and climate change.

Against this background, the key messages of this Survey are:

The economy is recovering as the pace of vaccinations picks up. Growth will strengthen eventually allowing monetary and fiscal authorities to reduce their support to the economy and focus more on structural changes that will sustain growth in the longer term. In particular, avoiding the types of scarring that occurred after previous downturns will be important.

The pandemic pushed up public debt to even higher levels and the country faces mounting budget pressures from a rapidly ageing and shrinking population. Fiscal sustainability needs to be secured in the longer run and actions taken to improve the state of public finances and push forward with reforms to boost productivity and participation. Longer-term sustainability also requires bringing greenhouse gas emissions down in line with government targets. Achieving these targets may require extra public spending or weigh on economic growth, depending on the approach adopted.

Improving economic and social outcomes calls for further structural reforms. Progress in digital transformation would boost productivity while offering households better and more targeted services. Many of the preconditions for the successful use of digital tools are in place, but complementary investments in hardware and human capital are needed.

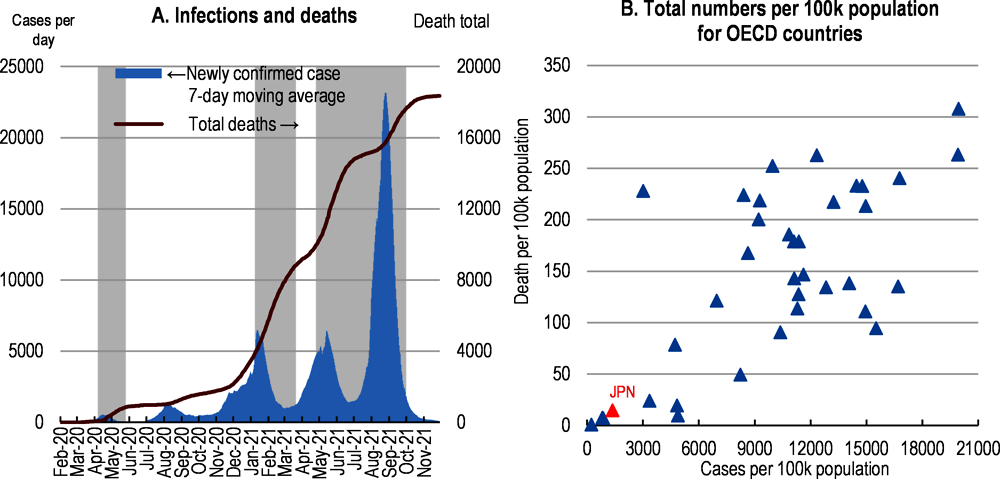

After Japan’s first case of COVID-19 was confirmed on 16 January 2020, the number of cases gradually increased (Figure 1.2). The government requested schools to close in March, and then declared a state of emergency in April. Under Japan’s Constitution, this merely allows prefectural governors to request school closures, restrict the use of public facilities and request non-essential businesses to close, but not to impose curfews or similar impingements on individuals. Even so, the effect was large given people’s changes in behaviour and a successful information campaign promoting the avoidance of the “three Cs” (closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings). In addition, normal sanitary measures in Japan, such as wearing masks and regular hand washing, helped early on. As a result, the rate of infections and deaths in Japan is relatively low (Figure 1.2). The largely voluntary confinement contributed to a dramatic drop in economic activity as businesses closed or shifted to telework and households shielded themselves. This helped bring the spread of the coronavirus under control while the capacity for testing and medical care was stepped up.

A second wave of infections between late-July and mid-August 2020 saw a limited rise in new cases of COVID-19 and a comparatively low death rate, thanks in part to test-track-and-trace measures. While limiting the number of infections considerably below the health system’s capacity to cope with them, central and local governments gradually lifted the restrictions on large-scale events and other activities involving close personal interaction. Central government also subsidised travel and eating-out to assist the domestic tourism and hospitality sector. However, partly as a result of increased movement, the number of infections rose worryingly in late 2020, prompting the government to declare a second state of emergency in January 2021. Unlike the first one, it targeted designated areas, and still permitted small-scale events and school attendance. With the spread of new and more contagious variants in 2021, a third and then a fourth state of emergency were declared. In the meantime, an amendment to the law in February 2021 granted governors of prefectures affected by the state of emergency greater powers, enabling them to order restaurants and bars to shorten their hours and to compensate or fine them.

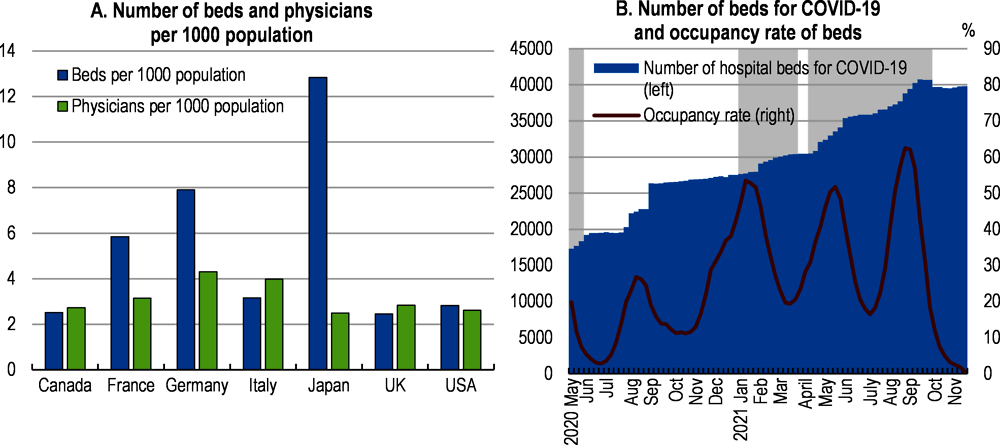

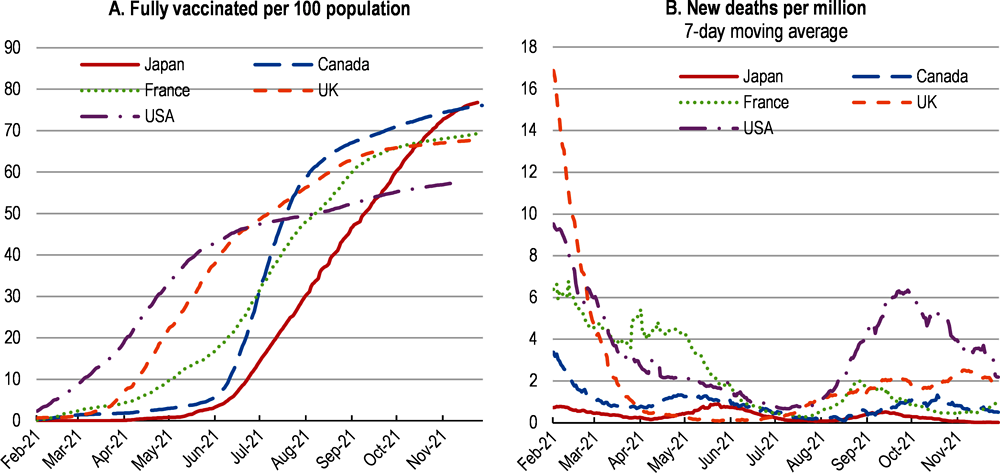

One key vulnerability in coping with the virus was limited medical capacity to deal with infections. While Japan has more hospital beds per capita than other G7 countries, it has fewer physicians, and the number of beds devoted to COVID-19 was relatively modest (Figure 1.3). Therefore, when infections rose in particular localities, hospital admissions could quickly stretch health service capacity. In addition, large-scale vaccination started later in Japan than in other G7 countries (Figure 1.4). The vaccination campaign was initially limited to a sole vaccine. There were initial teething problems in getting local government online vaccine information systems operational. Subsequently, more vaccines were approved and more resources devoted to making vaccination available. As a result, the pace of vaccination picked up, with over 1 million doses administered daily by mid-June 2021 and Japan’s national vaccination rate overtaking that of the United States in September, and that of all other G7 countries by November.

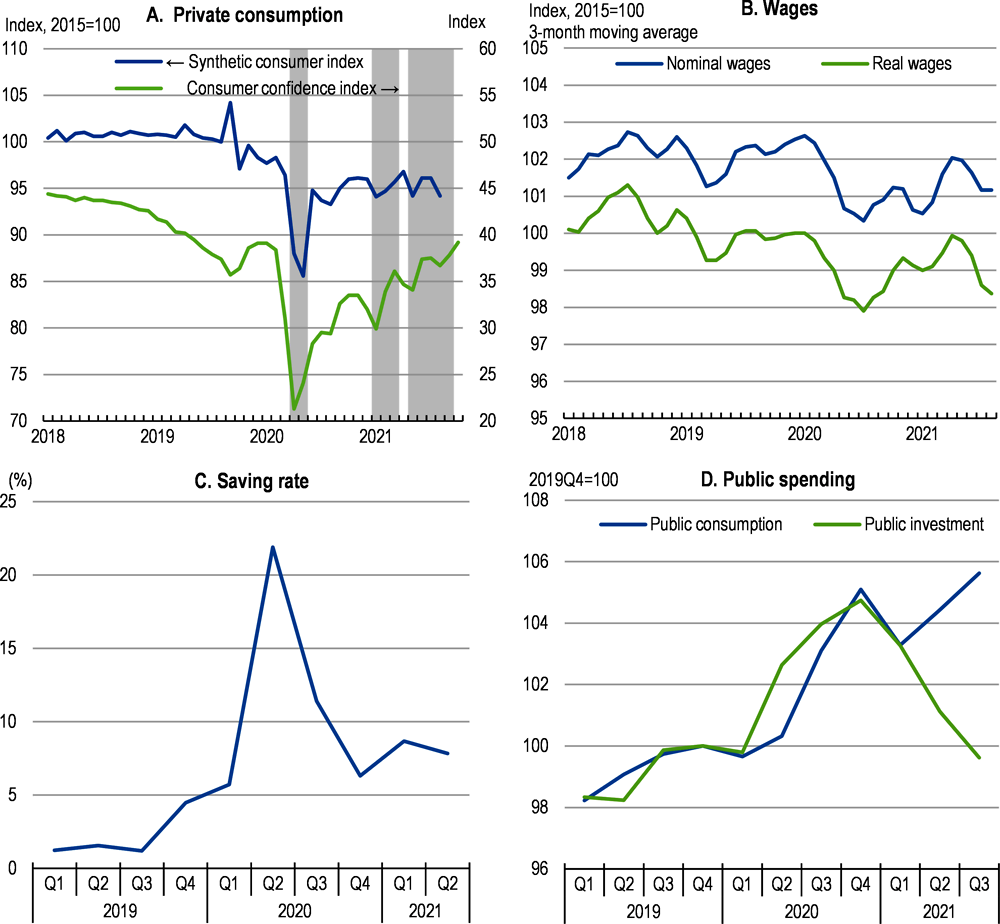

With the onset of the pandemic and the introduction of the first state of emergency, consumer confidence and private consumption plunged (Figure 1.5). They bounced back to some extent as sanitary restrictions were eased and infection rates declined, supported by government incentives. However, subsequent waves of infections gave rise to stop-and-go confinement measures holding back private consumption and the recovery in consumer confidence has been less than complete. Even so, as sanitary measures have become more geographically targeted and households and businesses have adapted to the new environment, not least by employing digital tools, the impact of new sanitary measures on the economy has lessened.

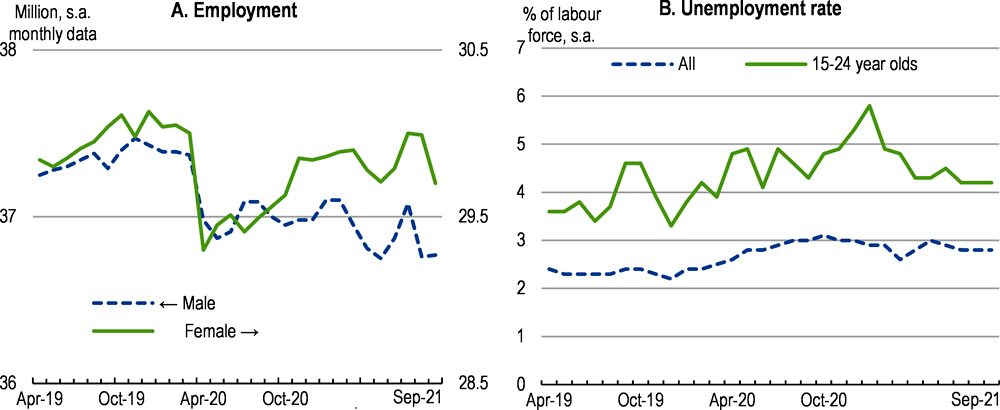

The pandemic entailed immediate job losses. The number of people employed dropped by almost one million in April 2020 and has not recovered completely since (Figure 1.6). Most of the job losses were concentrated in industries particularly exposed to the coronavirus and confinement measures, such as accommodation, food and drink services and to a lesser extent manufacturing. Employment in healthcare by contrast rose over the past year. The initial job losses were felt more heavily by women. However, by April 2021, more women had (re) entered employment such that employment loss relative to the pre-pandemic level was standing around 200,000 whereas for men the loss exceeded 500,000.

The unemployment rate rose relatively gradually from 2.5% prior to the pandemic and peaked at 3.1% in October before starting to edge down, partly thanks to employment retention measures. The rise in unemployment was more pronounced for younger age cohorts. Those remaining in employment saw hours cut by 10% relative to pre-pandemic conditions at the nadir in May 2020. Wages also fell, although more modestly than the cut in hours, partly due to composition effects as after the initial shock the numbers (of women) in regular employment rose steadily whereas low-wage workers with non-regular contracts were more likely to lose their jobs. In addition, mid-year and end-of-year bonuses, which typically make up a sizeable portion of total compensation, were sharply retrenched. As a result, total household earned income fell in 2020, before gradually recovering as the economy began to reopen.

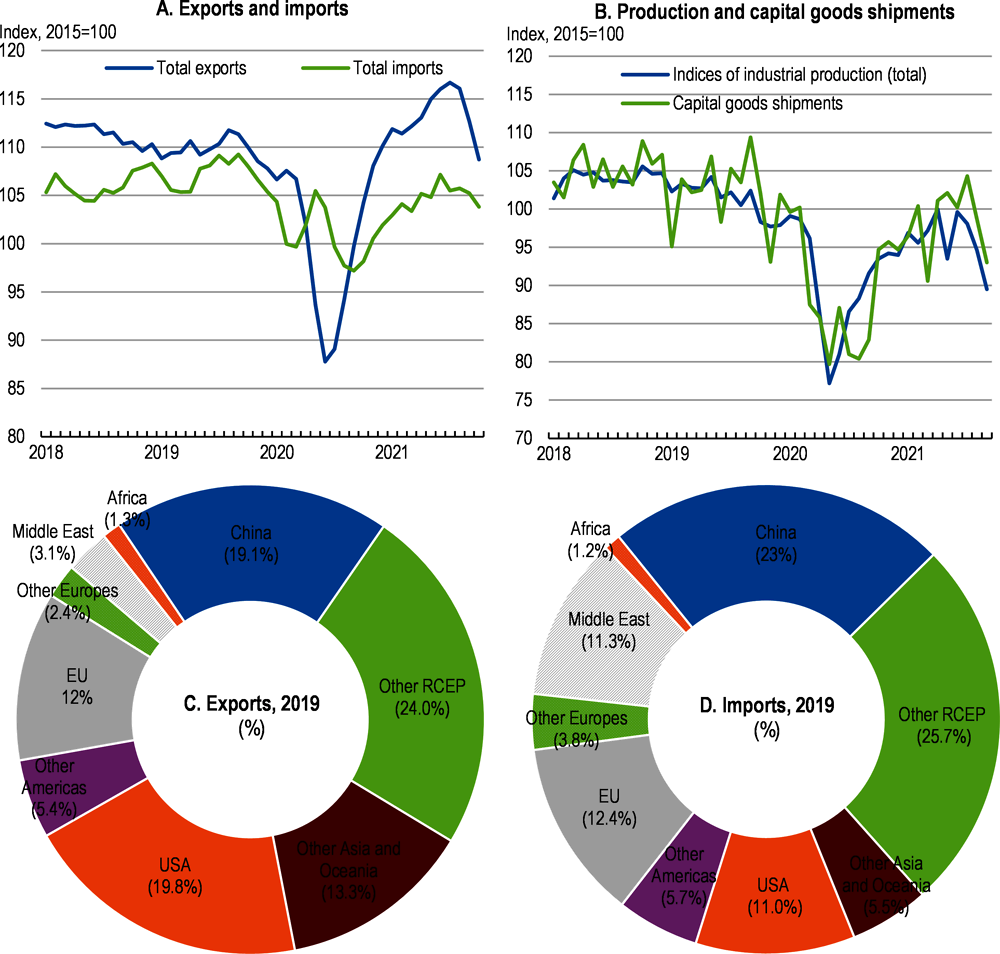

The initial economic recovery benefited from strong export markets, particularly in East Asia and the United States. The recovery in exports outpaced imports, reflecting weak private consumption growth (Figure 1.7). While the strong rebound of automobile-related demand in 2020 has moderated recently, exports of ICT-related products continue to strengthen as trading partners recover. The recovery of industrial production has boosted investment (as tracked by higher-frequency capital goods shipments), which had collapsed in mid-2020 along with industrial production (Figure 1.7). The recovery of trade has been uneven as supply bottlenecks have periodically constrained growth. For example, shortages of intermediate goods, once inventories were depleted, have held back automobile exports, which fell by almost 15% in August 2021. The recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement will support stronger trading relationships and promote free and fair trade and investment amongst members, notably through tariff reductions, simplification of rules of origin, prohibition of performance requirements (such as technology transfer and adoption of a given royalty rate under a license contract), free data flow and better intellectual property rights protection.

Inbound tourism had been a rapidly growing part of the economy in recent years, following relaxation of visa requirements and overseas promotion efforts. International visitor arrivals nearly quadrupled between 2010 and 2019 to almost 32 million, with much of the increase accounted for by visitors from China, South Korea and Hong Kong, China. Pandemic-related restrictions on international travel, which have tried to leave flows open with countries with limited infection rates, led to visitor numbers collapsing to just 4 million in 2020 and remaining subdued so far in 2021. The planned Olympics and Paralympic Games were postponed in 2020 and while the initial hope was for tourists to come for the games, eventually decisions were made to limit audience numbers and prevent international tourists from attending. As a result, the expected boost to economic activity from associated inbound tourism was considerably reduced. Some investments in infrastructure, tourism and hospitality in anticipation of the Games will nonetheless increase capacity when international travel again becomes feasible (Osada et al., 2016[1]).

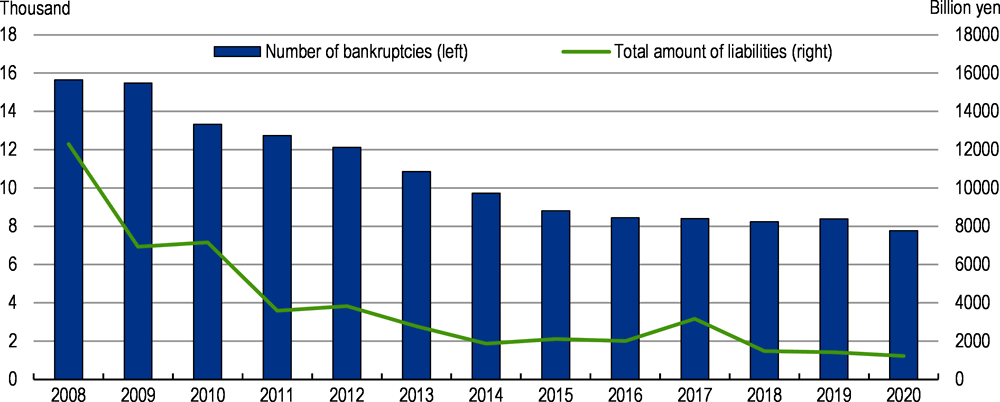

Macroeconomic policy reacted strongly in the face of the pandemic. The Government launched a series of economic measures to keep workers attached and secure business continuity. They included the Employment Adjustment Subsidy, cash benefits to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and concessional loans. The coverage of the Employment Adjustment Subsidy was expanded and its eligibility criteria were relaxed. As a result, non-regular workers who are not covered by employment insurance, were covered. Furthermore, targeted support was provided for industries particularly hard hit by the pandemic. For example, the government provides subsidies to businesses that are requested to shut down for a period or reduce operating hours. These measures have successfully protected jobs and businesses. Indeed, compared with many other countries unemployment has remained low, bankruptcy numbers have fallen and the spread of infections has remained relatively muted. In addition, a special JPY 100,000 (around USD 900) cash payment was made to all individuals around mid-2020. This contributed to a sharp increase in the household saving rate in 2020, partly as a result of its untargeted nature and of measures to prevent the spread of infections. The spike in the aggregate saving rate largely reflected a fall in the consumption of higher-income households. Furthermore, the subsidies for travel, lodging and restaurants in a series of Go to… campaigns promoting domestic tourism and entertainment activities were implemented. However, these policies were suspended as infections began to climb again. Public consumption and investment were stepped up to address the pandemic and support the recovery. Monetary policy was also supportive and ensured ample liquidity for the financial sector.

Following the sharp contraction in 2020, the economy is projected to recover, gradually eliminating slack (Table 1.1). The government in September 2021 announced a plan to relax restrictions as vaccination progresses, even in the case of a new wave of infections. As sanitary restrictions are lifted and vaccination accelerates, economic activity will strengthen. Subsidies to support the service sector (for travel costs), which were suspended in December 2020, are assumed to be restarted and boost consumption in 2022. However, the decision whether and when to restart this programme will be determined taking into account COVID-19 infection rates. While the household saving rate is projected to decline from the level reached in 2020, albeit without fully reverting to pre-pandemic levels, sluggish wages will limit the uptick in consumption growth. Exports are set to pick up thanks to the ongoing recovery of large trading partners, including the United States, China and other Asian countries. Relatedly, investment will gain speed, helped also by government subsidies promoting digitalisation and decarbonisation. Inflation is expected to rise only gradually from very low rates as domestic demand recovers, and cuts in mobile phone fees as well as the resumption of service sector subsidies push down the headline consumer price index.

While the outlook is for a steady expansion, there are substantial risks (Table 1.2). The evolution of infections is of major concern. Success in reducing transmission and progress in vaccination may allow a stronger recovery, whereas continued infections would hold back any recovery and potentially aggravate scarring with workers failing to regain employment and new entrants to the labour force not finding jobs. Commodity price spikes and supply-chain disruptions present threats, while progress in vaccination and additional fiscal packages in other countries could boost exports further.

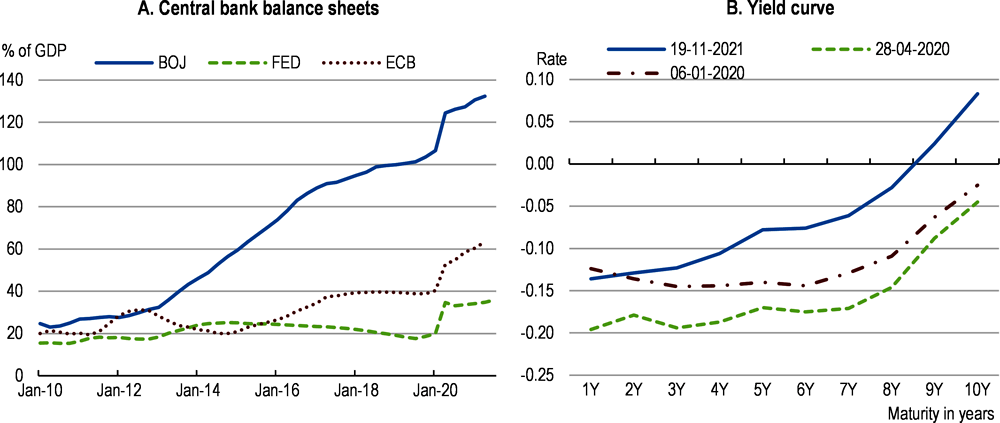

Monetary policy reacted promptly to the pandemic

The Bank of Japan moved quickly in response to the pandemic and adjusted measures as understanding of the shock evolved (Table 1.3). Overall, monetary policy continues to be accommodative. The Bank of Japan has used quantitative and qualitative easing and yield curve control to maintain short-term policy interest rates at minus 0.1% and the 10-year government bond yield around zero, keeping the yield curve relatively flat (Figure 1.8). The renewed commitment to buying Japanese government bonds, the increased purchase of T-bills and the new funding-for-lending type measures to cope with surging loan demands amid Covid-19 have boosted the balance sheet further. The Bank of Japan now holds around 7% of the total market capitalisation of the first tier of the Tokyo Stock Exchange and just under half of the total stock of Japanese government bonds (Fueda-Samikawa and Miyazaki, 2021[2]).

Inflation remains subdued

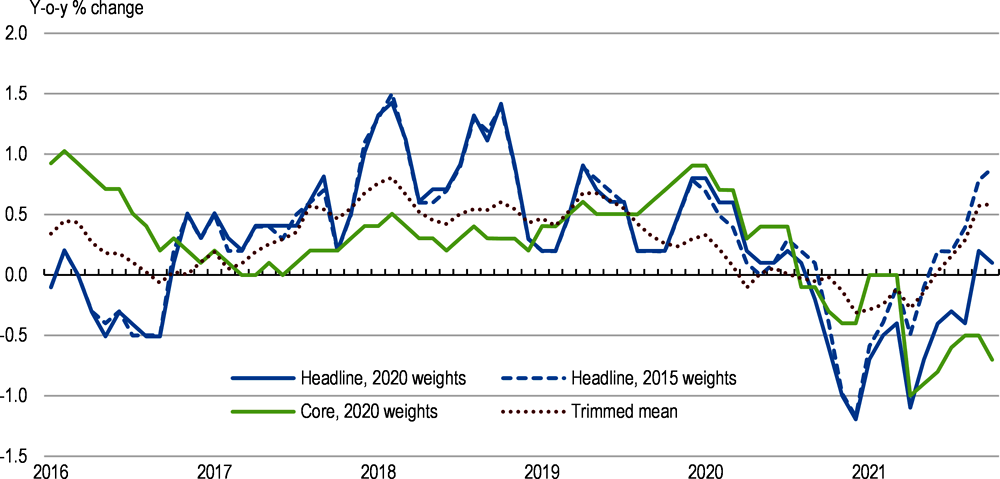

Consumer price inflation has been hovering around 0-1% in recent years, persistently undershooting the 2% Bank of Japan target rate (Figure 1.9). Wage inflation has slowed as well since late 2019. While the effect of the pandemic was deflationary during 2020 and early 2021, several policy-induced changes were also weighing on prices. For example, the reduction in mobile phone charges, at the behest of the government, had a sizeable impact on inflation rates (around 1.1 percentage points). In addition, government subsidies to the domestic travel and hospitality sector have put downward pressure on their prices. Stripping out these transitory effects, a trimmed mean measure of underlying inflation has begun to inch up more recently.

Inflation expectations have remained subdued, partly a result of a backward-looking component that is strong in relation to other OECD economies and has given limited traction to the inflation target following its introduction in 2013 (Turner et al., 2019[3]). However, inflation should gradually pick up as the economy begins to emerge from the pandemic and spare capacity shrinks. Inflation pressures may also come from the external sector. Increasing commodity prices, spikes in the costs of international transportation and recent exchange rate depreciation have put upward pressure on import prices. However, the collapse of import prices when the pandemic hit was substantial, such that on a year-over-year basis import price inflation remained negative in early 2021. Nonetheless, sustained commodity price increases, further supply disruptions and rising inflation in other markets overseas could pass through to higher domestic inflation. Inflation expectations have not moved much in recent years but are likely to increase as observed inflation picks up along with economic conditions. Against this backdrop, it is appropriate that monetary policy accommodation is not withdrawn prematurely.

In March 2021, the Bank of Japan released the results of a policy assessment, which confirmed the usefulness of the existing 2% inflation target, Quantitative and Qualitative Easing with Yield Curve Control, negative interest rates and commitment to overshooting. With an eye to ensuring the sustainability of monetary easing and remaining nimble in the face of changing economic and financial circumstances, the assessment introduced a few changes. The first one was to establish the Interest Scheme to Promote Lending, in which interest is paid, as an incentive, and the rates are linked to the short-term policy rate on financial institutions’ balances held at the Bank of Japan. With this scheme, the Bank of Japan can cut short- and long-term interest rates more nimbly while taking into account the impact on financial intermediation. The second change was a clarification of the fluctuation range for the yield on 10-year government bonds, aiming to find the appropriate balance between controlling yields and maintaining market functioning. This may eventually allow banks to earn some profits from a somewhat steeper yield curve. The third one was to relax the commitment to purchase exchange-traded funds, though maintaining the intention to re-enter the market when it is volatile. This change reflects an assessment that the effects of purchases tend to be greater the higher instability in the financial markets and the larger the size of purchases.

The financial sector has supported firms during the pandemic

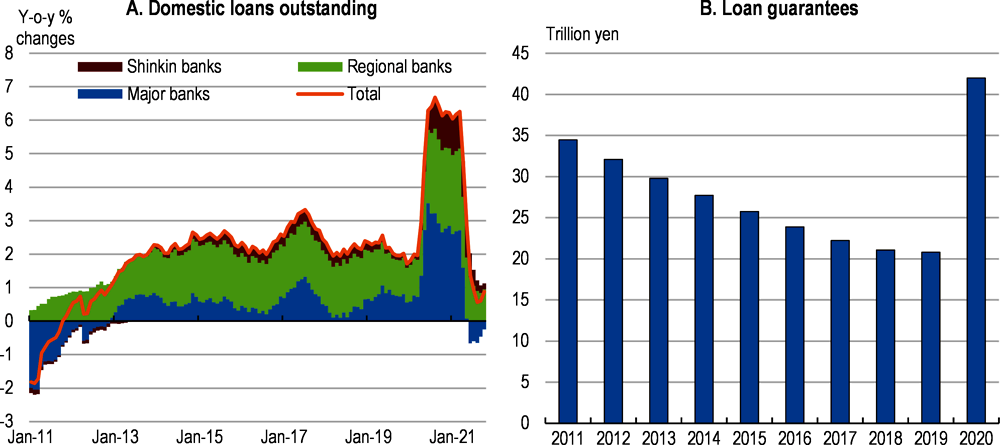

Financial institutions provided credit as cash flows dried up with the onset of the pandemic (Figure 1.10). The build-up of loans was split between large and small enterprises and concentrated in the manufacturing sector. Major banks tend to lend to larger enterprises, whereas regional banks lend to small and medium-sized enterprises. Part of the pickup in SME lending was underpinned by the public credit guarantee corporations, which support lending to small and medium-sized enterprises. As a consequence, loan guarantees have risen substantially, to over 7% of GDP – exceptionally high by international standards. By mid-2021, the growth of loans had slowed to rates seen through most of the 2010s. In the household sector, housing loans remained relatively unaffected by the pandemic. In contrast, outstanding credit card loans declined as the pandemic and confinement measures led to a curtailment of private consumption.

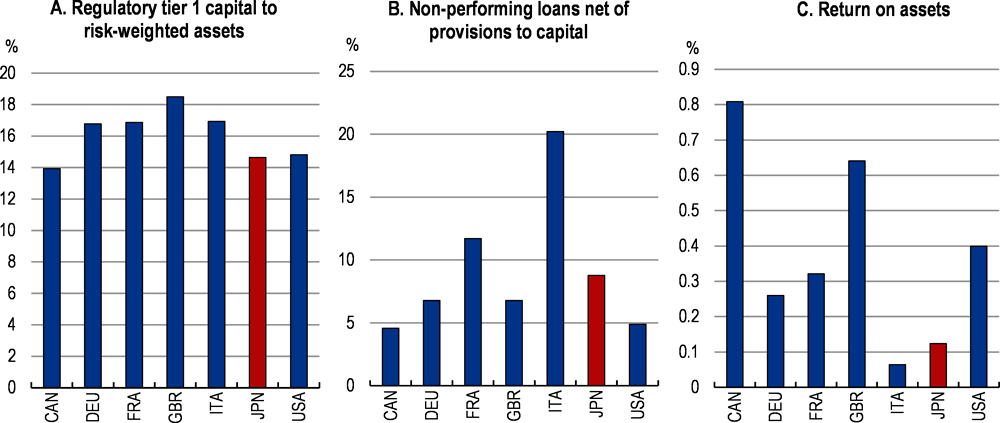

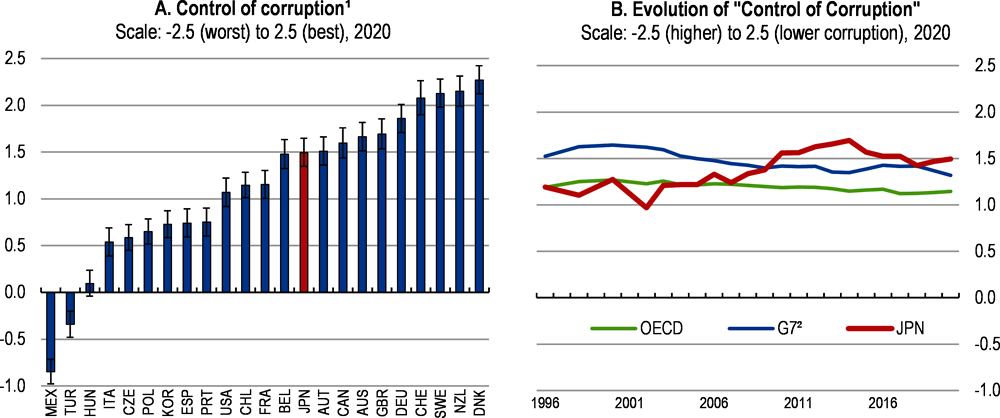

The financial sector has withstood the pandemic shock relatively well. Efforts to strengthen the financial sector, particularly the major banks, following the global financial crisis in 2008, appear to have paid off and recent stress tests suggest that the financial system is in a position to withstand further shocks while the economy continues to recover (Bank of Japan, 2021[4]). Capital adequacy of the major financial institutions appears in line with other major economies and non-performing loans is also relatively low (Figure 1.11). However, the return on assets is on the low side. Generally these metrics are weaker for the regional banks.

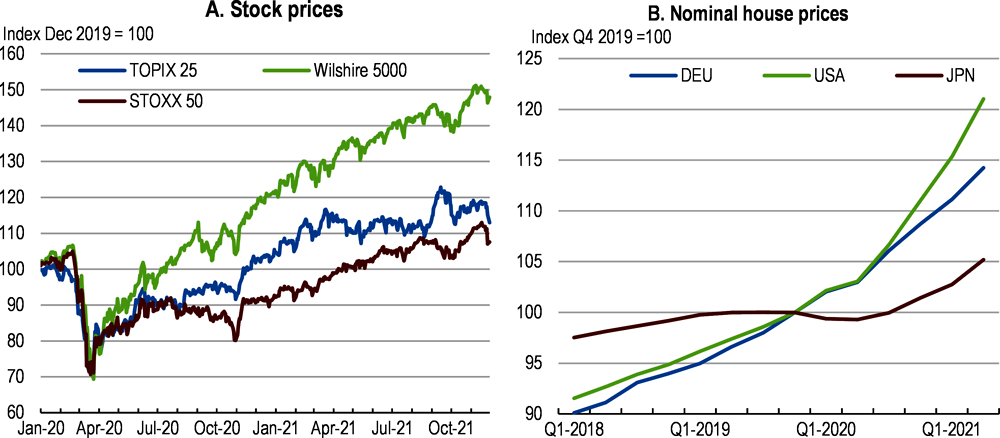

Financial policy needs to navigate the withdrawal of support and faces a number of risks. Notably, the cost of credit could increase, hitting some firms with high debt loads that are still struggling. One estimate suggests that up to 500,000 smaller companies, mainly in the sectors most exposed to the coronavirus, would face difficulties if restrictions on economic activity were to persist for more than two years (NRI, 2020[5]). A second set of risks revolves around elevated asset prices. Indeed, following the initial shock of the pandemic, some asset prices have climbed higher, notably stock prices (Figure 1.12). Housing prices have also strengthened, but less than elsewhere. Finally, some financial firms are exposed to foreign currency funding. Bank foreign-currency denominated loans have risen in recent years with regional banks increasing such loans to residents, whereas overseas branches of major banks have tended to increase these loans. In early 2020, a tightening of foreign currency funding markets required central banks around the world, including the Bank of Japan, to ensure sufficient liquidity. Japanese banks are increasingly focusing on how to balance the stability of foreign currency funding with their cost control. In this context, financial supervisors need to remain vigilant to liquidity and funding risks.

A number of other structural issues are emerging in the financial sector. Despite the relatively good measures of capital adequacy, chronic pressure on profits from ageing and the low-interest rate environment raises some questions about the banking sector. As highlighted in the previous OECD Economic Survey, given the incentives some financial institutions have to take on additional risk, financial regulators need to remain vigilant (OECD, 2019[6]). These incentives appear to be stronger in the regional banks, which are possibly also more vulnerable to emerging competition from FinTech.

Addressing the relative weakness of regional banks

The regional banks (and the local credit unions or Shinkin) traditionally play an important role in lending to small and medium-sized enterprises, notably in rural areas. However, as the population and economic activity has increasingly been concentrated in larger metropolitan areas, the combination of low interest rates and an ageing population have created problems (high fixed costs in maintaining regional networks and fear of risk taking) and concerns about the health of the regional banking sector. Intensified competition in retail banking has seen an increasing concentration of loans to low-return borrowers (firms for whom interest rates are low given their credit score) (Kawamoto et al., 2020[7]), with the share thereof amongst SMEs having risen to around one quarter before the pandemic (Bank of Japan, 2020[8]). This exposes regional banks to credit risks, particularly as the exceptional pandemic-related support for firms is withdrawn. The operational efficiency of the regional banks has been eroding since the mid-2000s. Digitalisation could play some role in reducing costs as cashless transactions and remote banking could reduce some of the fixed costs of maintaining a network of banks and ATMs. However, a recent survey of regional banks showed that while many felt operational efficiency had increased during the pandemic, only around one fifth were considering using information technology to reduce system costs (Fueda-Samikawa and Miyazaki, 2021[2]). Many saw ICT creating opportunities to expand customer services and improve the efficiency of face-to-face sales, but with progress constrained by ICT weakness in business partners.

As ageing is pronounced outside the major cities, progress in digitalisation needs to be balanced against the danger that technology-shy elderly and other customers may lose access to some financial services if banks retrench physical provision drastically. Against this backdrop, the Bank of Japan introduced a special deposit facility and the FSA established a scheme to encourage regional financial institutions to strengthen their efficiency and business foundations (with knock-on benefits for the regional economy). Many regional banks are considering ways to rely more on providing fee-based services (almost 70% in the aforementioned survey), which may be needed given that digitalisation entails new sources of competition in banking services.

Digitalisation of financial services

The ongoing digitalisation of the financial sector and the development of FinTech create new opportunities and challenges for policy (Box 1.1). One issue is mitigating cyberattacks, which have become more prevalent particularly as computing and remote working become more common (Bank of Japan, 2021[4]). In addition, regulatory and competition issues arise as new technologies can facilitate the provision of financial services by non-bank entities. For example, intensified competition could push down bank profitability further and aggravate search-for-yield incentives. As such, the authorities will need to keep abreast of such developments to understand where risks are being built up and whether evading regulatory requirements constitutes unfair competition.

Japan has been at the forefront of some FinTech developments, particularly with respect to cryptocurrencies. The involvement of the banking sector has been more muted, partly due to regulatory issues. Cybersecurity and the interaction with the rest of the financial sector are issues of concern in a rapidly evolving market.

The Japanese authorities were quick in responding to crypto currencies. The Payment Services Act recognised these currencies as legal property, requiring traders to register in order to comply with anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism regulations. Partly due to establishing a favourable regulatory environment, Japan has become a major market for Bitcoin with 29 bitcoin exchanges in operation. The tax authorities tax gains on these currencies. In 2020, legislation came into effect to regulate cryptocurrency derivative trading that fell outside the Payment Services Act. After a series of cyberattacks, the Financial Services Agency has begun to regulate the exchanges more rigorously. This has also led to greater self-regulation by the participants on these exchanges.

The Bank of Japan has been evaluating the possibility of a central bank digital currency. Work initiated in 2016 with the European Central Bank explored distributed ledger technologies (European Central Bank; Bank of Japan, 2020[9]). In April 2021, the Bank of Japan began testing basic functions such as issuance, distribution, and redemption, focusing on a general purpose (or retail) central bank digital currency. It envisages future work on ensuring privacy, handling end-user information and the impact on financial intermediation of banks.

At present, banking regulation limits banks’ ability to engage in non-banking activities. As such, banks are forming partnerships with technology companies. Indeed, three of the major banks have announced a collaboration with technology companies. An alternative approach is to exploit firm databases to understand when contractors and subcontractors may need additional funding during a major project.

Another strand of development has been so-called platformers. They initially offered digital payments services, but with a large customer base have developed new financial services. Likewise, retail companies are trying to leverage the information from their customer databases in offering new services. By linking data from different databases, new approaches to screening loan applications are possible. For example, “smart money lending” can assign a credit rating score based on an individual’s behaviour, both financial and non-financial. In this way, credit can become available to previously unbanked individuals and in some cases small firms (Bank of Japan, 2021[10]).

As the experience of the cryptocurrencies exchanges shows, regulation needs to be nimble to ensure cybersecurity. Regulators also need to check whether technology companies and platformers’ innovative uses of personal data are secure and do not expose clients to digital crime. In this regard, there are trade-offs in using third-party service providers for data services. Such firms can invest more heavily in cybersecurity, but regulators also need to assess whether their use is compliant with financial sector regulation (FSB, 2019[11]). Intensified competition with existing banks in an environment of low interest rates may also provoke heightened risk taking, particularly in the absence of a level-playing field (Restoy, 2021[12]).

Green finance is becoming more prominent

The green bond market in Japan grew quite rapidly in 2020, with issuance rising to over USD 10 billion, taking cumulative issuance to USD 68.4 billion (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2021[13]). Government-backed bodies, such as the Japan Housing Finance Agency, account for around one third of total issuance with buildings, transport and energy the most important market segments. The institutional framework around the market is also developing. A sizeable share of issues are reviewed, receive a green bond rating and some are certified, thereby reducing the risk of “greenwashing”. Furthermore, there is growing support for environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting. For example, a public-private partnership, the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) Consortium, was launched in 2019 to promote improved climate-related financial disclosures, including through issuing guidelines (TCFD Consortium, 2020[14]). In addition, the Tokyo Stock Exchange revised its Corporate Governance Code in June 2021, requiring future listed companies on the Prime Market to disclose information based on TCFD recommendations or equivalent international frameworks (Tokyo Stock Exchange, 2021[15]). Furthermore, the Financial Services Agency established a working group under the Financial System Council to discuss the disclosure system, including sustainability, with a broad range of stakeholders. Other governments and central banks have also become involved in this area. For example, the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation of March 2021 requires financial firms to be transparent to their clients about sustainability risks and possible adverse sustainability impacts. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission in March 2021 announced the creation of a Climate and ESG Task Force. Similarly, the Financial Services Agency has established a Sustainable Finance Office. The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, of which the Bank of Japan and the Financial Services Agency became members, have supported such initiatives. The Financial Services Agency will continue to work to avoid greenwashing such as by promoting discussion on issues of ESG rating and better data provision (Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance, 2021[16]). The Bank of Japan also announced the details of a new fund-provisioning measure in September 2021. This new facility provides funds for counterparties that have taken the decision to invest or lend, while discipline will be maintained through disclosure requirements on the financial institution’s efforts to address climate change. The funds will be provided until the end of fiscal year 2030, in principle, to give long-term support for financial institutions’ efforts. The new facility will become operational by the end of 2021. Progress on these different initiatives could create the conditions for Japan to become an important node in green finance (Shirai, 2021[17]).

The government reacted swiftly to provide fiscal support in the face of the pandemic. It introduced economic policy packages in April and December 2020 and three supplementary budgets for fiscal year 2020 as the impact of the shock became clearer. Furthermore, it adopted an additional economic policy package in November 2021 (Table 1.5). The later measures focused more on the exit from the pandemic and beyond. This included support to enhance R&D and investment in advanced technologies, thus promoting the digital transformation and green growth. The support also strengthened policies to address distributional concerns and enhance workforce skills (Box 1.2). These initiatives will help sustain domestic demand while the economy remains weak. Indeed, support for structural reforms, which require upfront investments in education and training or physical capital, can help sustain demand in the short run while the economy is weak and improve longer-term economic prospects. The immediate fiscal measures have been successful in limiting drops in employment and enterprise failures, which are low by international comparison.

On 19 November 2021, the government adopted a new economic policy package, with four pillars and highlighting growth and distribution. The total package amounted to JPY 78.9 trillion (around 14.6% of annual GDP) for fiscal years 2021-22, including estimated contributions from the private sector. Central and local governments are projected to spend JPY 49.7 trillion (9.2% of GDP), with the central government responsible for the lion’s share (JPY 43.7 trillion).

The first pillar seeks to prevent the spread of COVID-19, with measures such as ensuring medical care provision, vaccines and drugs for COVID-19. It also provides support to vulnerable households and businesses, such as cash benefits for low-income households and affected small and medium-sized enterprises, and support for some sectors affected by high energy prices.

The second pillar is to support the reopening of socio-economic activities while preparing for the next crisis. This pillar includes measures such as using vaccination certificates or negative test results, restarting subsidies to stimulate demand in some service sectors, developing domestic vaccines and medicines and promoting international co-operation to reduce COVID-19 infections. A contingency reserve fund for COVID-19 (around JPY 6.8 trillion) is also included to be available for a future crisis.

The third pillar has two parts, a growth strategy and a distribution strategy:

1. The growth strategy includes expanding investment and R&D, especially for starting the operation of the University Endowment Fund worth JPY 10 trillion in FY2021, achieving the government’s net zero carbon emission goal with clean energy technologies, a new initiative called “Rural-Urban Digital Integration and Transformation” for revitalising localities with digital technology, and “economic security” with a new fund to support key technologies and improve their supply.

2. The distribution strategy includes measures to promote wage increases, to promote human capital development and labour reallocation by combining vocational training and out-placement support, and to raise the salaries of workers in the public sector such as nurses or caregivers. It also encompasses support for families with children, such as cash benefits for child-rearing households and additional provision of child-care facilities.

The fourth pillar includes measures to enhance resilience and disaster management capabilities, for which the government established a five-year plan (FY2021-25).

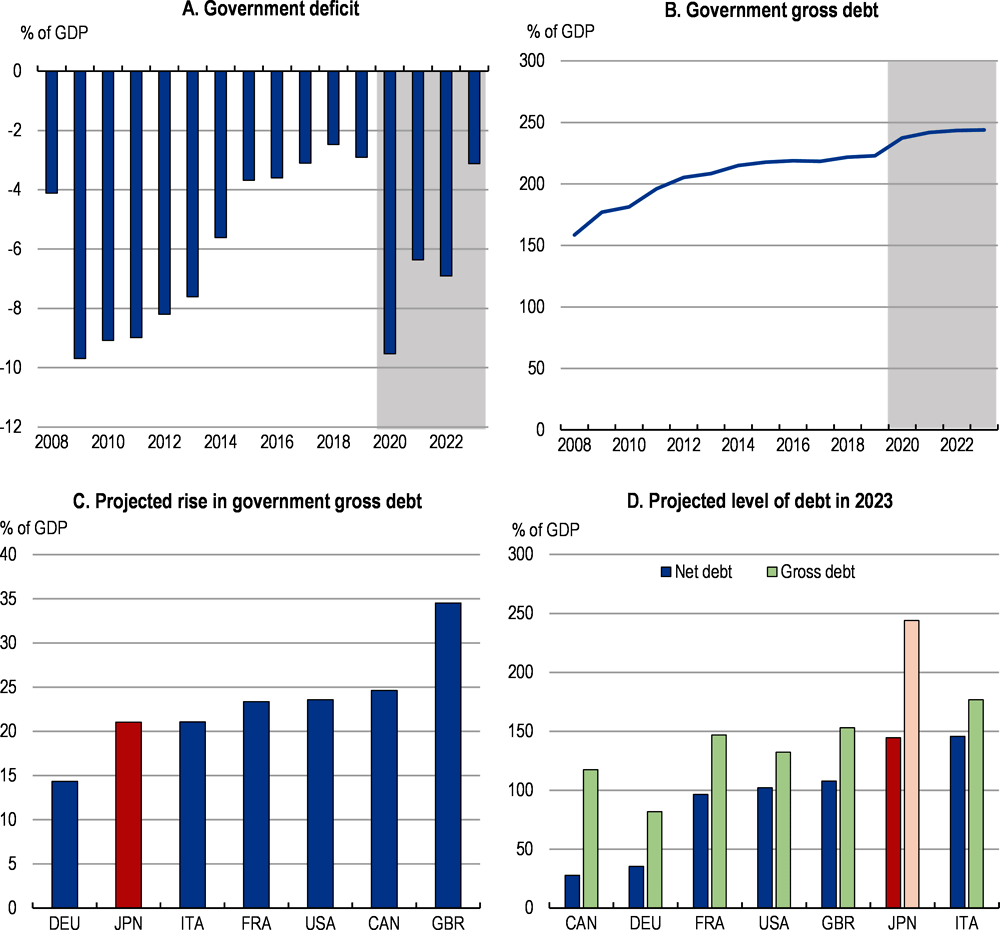

Like in many countries, the policy packages entail sizeable fiscal costs (Figure 1.13). The general government deficit ballooned to around 10% of GDP in 2020 and is on course to exceed 6½ per cent of GDP in 2021. However, reflecting the transitory nature of the shock, subsequent policy support is expected to be pared back as progress with vaccination allows the economy to reopen more fully. Nonetheless, public debt as a share of GDP has risen to unprecedented levels by historical and comparative standards, with gross government financial liabilities now exceeding 240% of GDP. The net debt position is projected to remain high and liquidating government financial assets in a time of market stress may be difficult.

The deterioration in the fiscal position comes after a period of progress in reducing deficits and the ambition since around the turn of the century has been to move to a primary balance or surplus to help ensure long-run fiscal sustainability. Plans to achieve a positive primary balance have been repeatedly deferred (OECD, 2019[6]). Fiscal policy should continue to support the economy in the near term. Only once the recovery is secure should fiscal consolidation efforts resume in order to ensure long-run sustainability. The government has decided to continue its gradual efforts to achieve the fiscal consolidation target of reaching a primary surplus by FY-2025, and the economic and fiscal consequences of the COVID-19 shock will be reviewed during FY-2021 (Cabinet Office, 2021[18]). Based on recent Cabinet Office projections, assuming a high growth rate, the primary surplus would be achieved in FY 2027 without further expenditure reforms, and in FY 2025 if expenditure reform continues.

Recent evaluations of fiscal sustainability increasingly discuss the interest rate burden rather than the debt level, arguing that higher debt levels are sustainable in a low interest-rate environment (Blanchard, 2019[19]). Net interest payments on outstanding debt in Japan have fallen to under 1% of GDP in recent years, notwithstanding rising debt. However, the current very low interest rate burden partly stems from the Bank of Japan’s Quantitative and Qualitative Easing and Yield Curve Control (Jones and Seitani, 2019[20]). This downward pressure on interest rates coupled with a large share of domestic financing has allowed the government to continue running budget deficits without risk of rising or volatile interest rates. As long as these conditions continue to hold, the financing of current debt levels is manageable. However, in the longer run, monetary policy success would imply higher interest rates as inflation remains durably around target and inflation expectations are consistent with a higher rate of inflation. Rising interest rates in the rest of the world may also break the current relationship. In this context, progress in fiscal consolidation will be needed to guard against a rise in interest rates pushing up interest payments and eventually initiating a debt spiral, even without additional pressures on the government budget.

Even if the short-term threat to fiscal sustainability is limited, action will be called for to address longer-term challenges. Notably, the impact of ageing and mounting pressure from social security spending without corrective action will increase budget deficits and threaten sustainability. Current official projections suggest that health and long-term care spending, largely driven by ageing, is on course to rise by 3 percentage points of GDP by 2040 and social security spending by 2½ percentage points. A newer source of pressure on the government budget is meeting the targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. This effort will require investment upfront, but carbon pricing may lift revenues. As such, meeting the climate change targets will have different impacts over time. Furthermore, a legacy of the pandemic is that the government holds larger contingent liabilities, to wit the doubling of loan guarantees to small enterprises to over 7% of GDP.

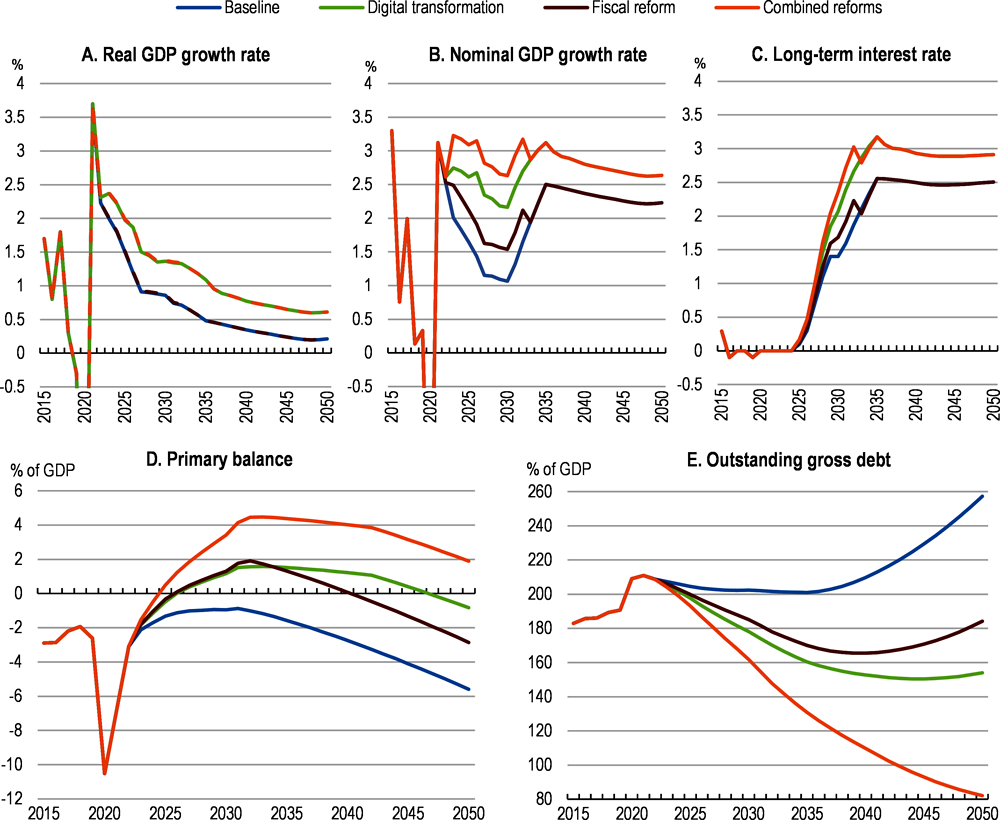

Incorporating these spending pressures in a simplified projection framework can give an indication of fiscal policy sustainability (Figure 1.14). For the baseline projections the path of the economy combines a baseline case of the Cabinet Office projection through FY2030 (Cabinet Office, 2021[21]) and the longer-run OECD projections (Guillemette and Turner, 2018[22]). Revenue projections are based on the Cabinet Office projections until FY 2030 after which GDP shares are kept constant (ageing may lower tax revenue, so these simulations may be overly favourable). Expenditure paths, which include the effects of ageing on health and long-term care and social security spending, take into consideration CPI or wage inflation and an ageing factor derived from the Cabinet Office projections. Long-term interest rates are determined by nominal GDP growth plus a term and risk premium. Effective interest rates are based on a nine-year moving average of long-term interest rates (which is the average tenor of Japanese government bonds).

In the baseline scenario, the debt ratio edges down over the short term, but as the economy slows and spending pressures intensify (due to ageing), budget deficits begin to widen and debt rises strongly beyond the 2030s, increasing by more than 50 percentage points of GDP by 2050 to around 260% of GDP. In the baseline simulation, fiscal policy is kept constant to examine the possible outcome if policymakers do not react. The results suggest that fiscal policy will need to adjust at some stage to ensure long-term sustainability. Options to do this are explored in additional simulations.

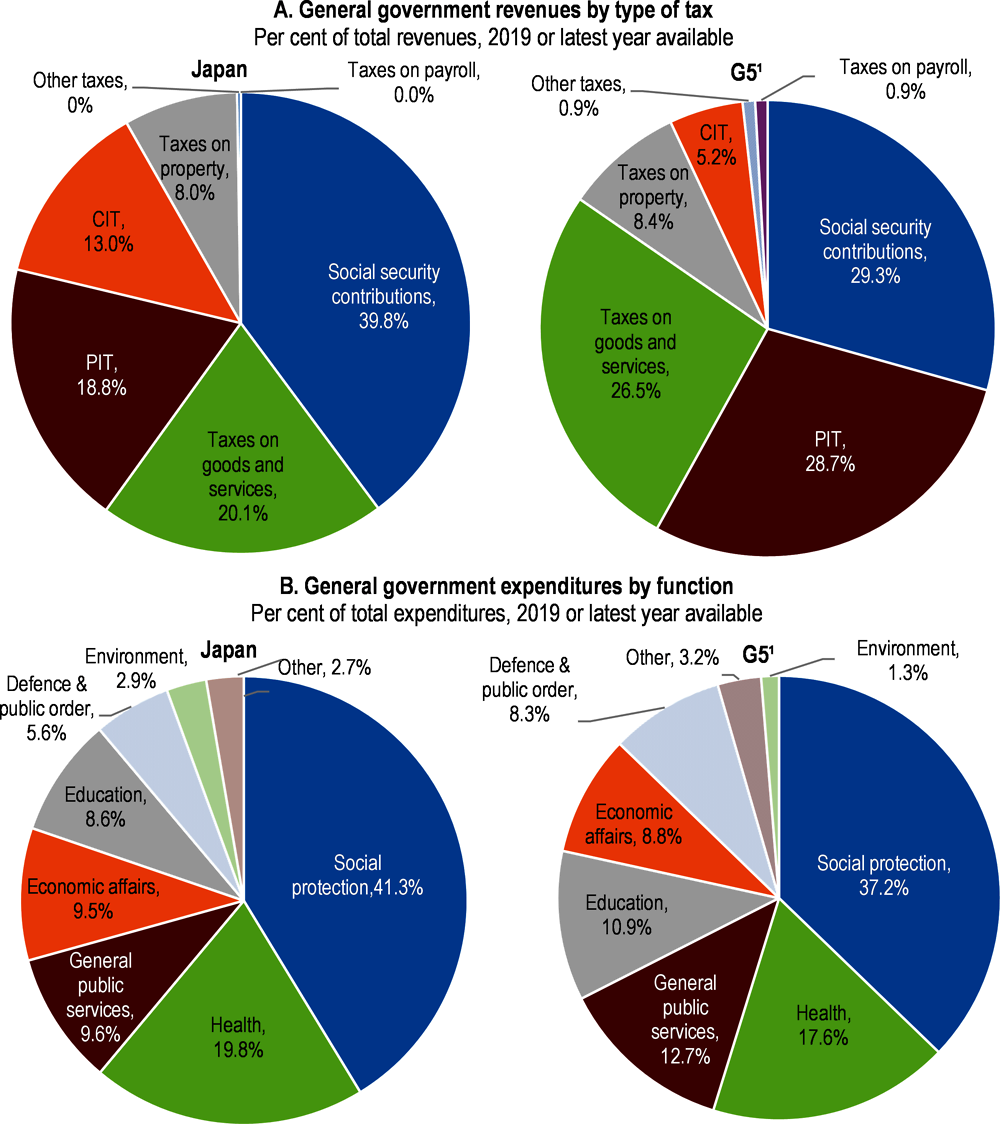

Progress towards sustainability was made prior to the pandemic, notably by the gradual increase in social security contributions over the years. Indeed, the share of social security contributions in general government revenue is large in comparison with other major economies (Figure 1.15). The consumption tax rate hike in October 2019 helped improve the fiscal position further, but the appetite for additional sizeable tax hikes is low, partly due to distributional consequences with low-income households particularly exposed to resultant price rises. Opportunities for cutting spending exist but government spending as a share of GDP is relatively small compared with many other OECD countries. Moreover, as noted, spending pressures are likely to intensify not only driven by ageing-related costs but also due to meeting greenhouse gas emission objectives.

In part, digital transformation could help contain the rise in spending over time and thus contribute to consolidation (see chapter 2). There are arguments to continue relying principally on consumption taxes for future consolidation needs once the economic recovery is secure. Indirect consumption taxes are a very efficient tax instrument and empirical evidence suggests that they are less damaging to economic growth (Johansson et al., 2008[23]). Similarly, making greater use of market-based instruments to meet greenhouse gas abatement goals could not only generate revenues in the short to medium term, but can help ensure that the unavoidable costs of the emission abatement needed to meet targets are minimised. Here again the distributional impact of these taxes will adversely hit low-income households. In this light, recycling some of the revenues raised to cushion the adverse initial impact of these measures is likely needed as part of a package to increase the chances of successful implementation (IMF and OECD, 2021[24]).

Against this background, the simulations also explore the impact of different packages of policies discussed in this Survey as means to improve fiscal sustainability, while taking into account growth and inclusiveness considerations:

In a fiscal reform scenario, the consumption tax is raised gradually from its current rate of 10% to 20% and the carbon tax from the current JPY 289/tCO2 to JPY 4000/tCO2 between FY2023 and FY2033. Like in the previous Economic Survey, the simulation assumes a rise in the consumption tax rate of one percentage point a year over a decade (OECD, 2019[6]). The assumed rise in the carbon tax rate is steep, but starts from a very low base and will generate comparatively little revenue relative to the consumption tax, even at its peak before revenues taper off as the economy successfully reduces carbon emissions. A higher carbon price may be required to ensure carbon neutrality (Kaufman et al., 2020[25]). The consumption and carbon tax hikes increase consumer prices and reduce real consumption, with the effects estimated using the multiplier from the Cabinet Office’s Economic and Fiscal Model (Cabinet Office, 2018[26]). The path of spending assumes one-half of the tax increases are used to raise spending to offset the impact on output (consistent with the implementation of the 2019 consumption tax rate hike). Additional spending would involve public spending on active labour market policies, social benefits for families, investing in green innovation and supporting the digital transformation as outlined elsewhere in this Survey.

In a digital transformation scenario, digitalisation and further investment in intangible assets are assumed to raise productivity growth by 0.3 percentage points relative to baseline (Saruyama and Tahara, 2020[27]). In addition, the labour force continues to benefit from increased participation rates as assumed in some projections (The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 2019[28]). On the expenditure side, possible efficiency savings from digitalisation are assumed to reduce spending by 10% relative to baseline and are phased in after FY2023 over 20 years.

In the fiscal reform scenario, gradual consolidation efforts improve the budgetary position until around the mid-2030s. At that horizon, the underlying budgetary pressures associated with ageing again begin to dominate and debt to mount. The digital transformation scenario builds in the possible impact of structural reforms, with higher productivity growth boosting GDP and improvements in cost effectiveness helping contain spending. However, here as well the gains are eventually insufficient as the underlying spending pressures again continue to rise and from the late 2030s to boost deficits and lead to increases in debt levels. In contrast, combining fiscal and structural reforms promoting digitalisation would keep fiscal policy sustainable until at least mid-century, keeping gross government debt levels on a downward path. While these simulations are sensitive to the assumptions used (Box 1.3), they clearly show that a combination of fiscal consolidation and structural reforms can help ensure long-run sustainability.

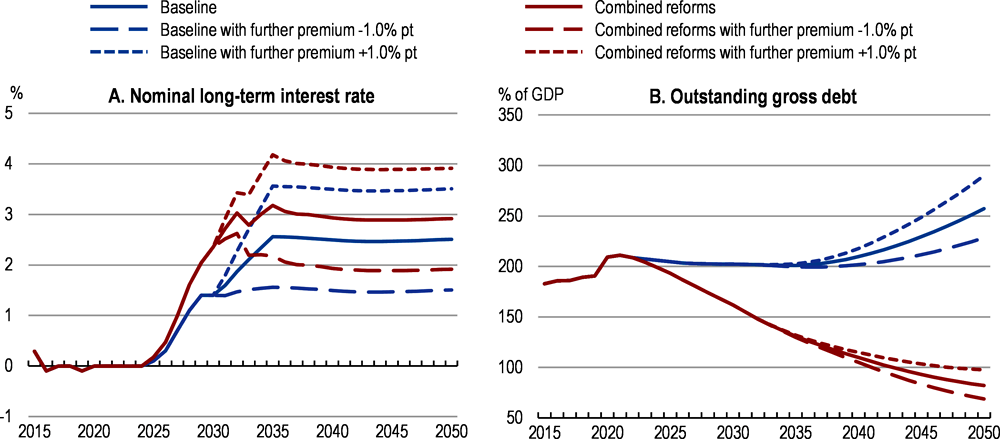

The projections rest on a number of simplifying assumptions. For long-term debt sustainability analysis, the primary balance, interest rates and the GDP growth rate are critical. The difference between long-term interest rates and nominal GDP growth rates after 2030 is around 0.2%-0.3%, which is low compared to historical experience on average over long periods. However, there is considerable uncertainty about whether interest rates will remain subdued or rise once economic growth is again on a firmer footing. Additional simulations therefore assume that the interest rate-growth differential is higher or lower by one percentage point. The results of these assumptions for the baseline scenario and the combined reforms scenario are shown in Figure 1.16. In the baseline scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2050 would be 30 percentage points less (more) in the lower (higher) interest rate scenario.

A second set of sensitivity analyses concerns the pace and timing of fiscal consolidation (Table 1.6). To explore this, the size of the assumed annual consumption tax rate hike is halved or the starting date of the tightening is pushed back to 2028. In both cases, debt levels in 2050 would be slightly above 200% of GDP and about 15 percentage points above the original fiscal reform scenario. These results are consistent with the previous OECD Economic Survey of Japan’s finding that delay would ultimately increase the size of the required adjustment (OECD, 2019[6]).

The above debt sustainability analysis suggests that the potential boost to productivity from digitalisation is not sufficient to ensure long-run debt sustainability. Moreover, the risks around these simulations are likely large, not least the scope for future natural disasters that could knock the economy off course. In this context, debt sustainability requires complementing fiscal consolidation efforts with other structural reforms. The previous Economic Survey laid out the main elements of a strategy (OECD, 2019[6]). A comprehensive fiscal consolidation plan would include the following elements (the possible fiscal impact is reported in Box 1.4), some of which are already in train:

Gradually raising further the consumption tax rate. In 2019, it was hiked from 8% to 10% − still amongst the lowest in the OECD (OECD, 2018[29]). The above simulations also include additional revenue from environmental taxes. Base broadening, particularly in the context of a reconfiguration of international taxation, offers additional means to raise more revenue at less cost to the economy.

Constraining spending growth in health and long-term care by making more use of home-based care, generic drugs and co-payments. In addition, digitalisation could help improve spending efficiency. Trials already underway suggest that monitoring robots can alleviate pressure on medical staff (see chapter 2) and could thus complement these reforms.

Rationalising the provision of local public services and infrastructure by promoting joint provision by local authorities. In the case of public investment and maintenance of the public capital stock, digitalisation may also help raise spending efficiency. Drones, robots and big data promise new ways to increase spending efficiency while reducing risks to workers.

Raising the pension eligibility age above 65 while promoting continued work by the elderly. In May 2020, the government enacted the Pension Reform Act. The reform introduces actuarial adjustments for delaying retirement, which should increase incentives to remain in work. The upper age limit was extended from 70 to 75 years of age.

The estimated budgetary effect of the reforms proposed in the report are reported in Table 1.8. These effects are illustrative. In practice, the design of policies may differ, such as the period over which they are phased in and whether flanking measures are adopted, including the recycling of revenues to address distributional goals. For example, the effect of raising the consumption tax in the debt sustainability analysis is lower than the policy effect reported in the table because of the assumption to use revenues raised from this tax to offset the impact of a higher tax rate on the most vulnerable households.

Long-run environmental and fiscal sustainability are interdependent. Ambitious goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will require government intervention, either through spending which will ultimately require additional fiscal revenue, such as from carbon pricing, or by imposing regulations, which will set an implicit price on emissions. In either case, such measures will weigh on economic activity. A well-designed package of policies can minimise economic costs while ensuring climate change objectives are met.

Progress in reducing emissions has been steady recently

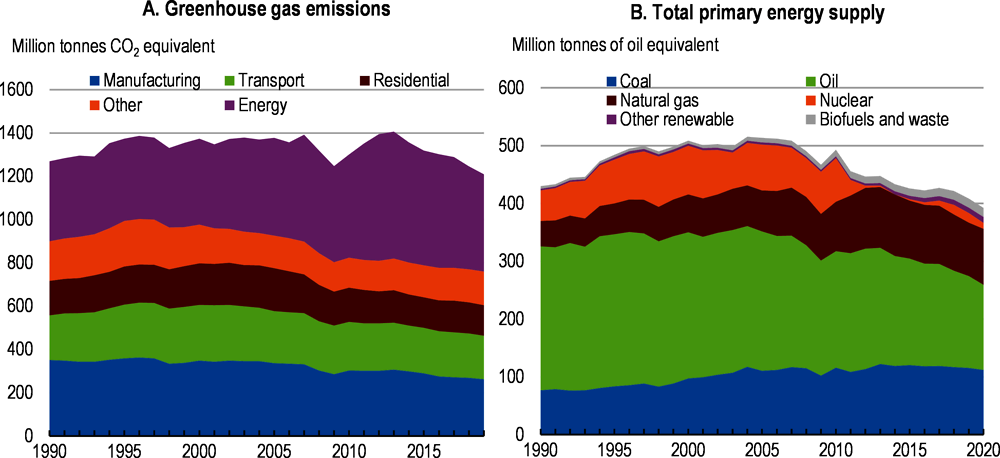

Greenhouse gas emissions peaked in 2013 (Figure 1.17), as the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and subsequent nuclear accident led to the shutdown of nuclear power plants and increasing reliance on fossil fuels (Box 1.5). Since 2013, greenhouse gas emissions have declined steadily, notably through greater energy efficiency and the wider use of low-carbon electricity. The energy sector is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases and its share has grown since the beginning of the century, though it has begun to decline more recently. As the restart of nuclear power was only very gradual, energy production has relied on a growing share of renewables and imported fossil fuels. The latter still accounted for 88% of total energy supply in 2019.

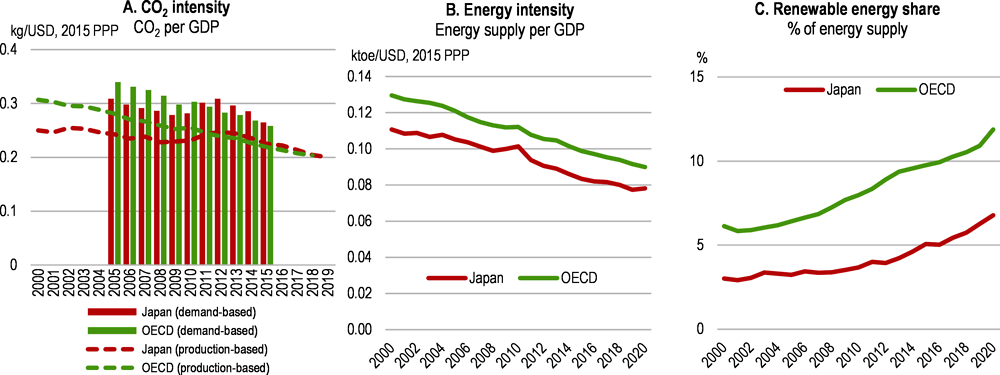

Economic activity and greenhouse gas emission have thus decoupled, although the advantage over the OECD average has been eroded as other countries have made sizeable gains (Figure 1.18). Japan stands out as one of the most energy efficient economies, owing in part to tightening energy efficiency standards for products, vehicles and housing. Widespread efforts to reduce energy demand to relieve pressure on the electricity sector after the Tohoku earthquake have had lasting effects. Current projections of energy use suggest a declining population, shrinking demand, and ongoing increases in energy efficiency will offset demand driven by economic growth.

In March 2021, the tenth anniversary of the Tohoku Earthquake, the subsequent tsunami and then the catastrophic failure of the Fukushima nuclear reactor was commemorated. The succession of disasters was one of the costliest in recent history, with almost 20,000 people losing their lives or disappearing as a result, and over 470,000 people evacuated. Housing, factories and farms were destroyed and land was contaminated by radiation. The legacy of these events is still being felt today. Early estimates of the costs of the destruction were up to around JPY 17 trillion (3% of annual GDP) (OECD, 2011[30]). Dealing with the consequences has required JPY 31.4 trillion of government spending between 2012 and 2020 (Reconstruction Agency, 2021[31]). Substantial further costs will have to be incurred to deal with the nuclear power plant and to complete decontamination (METI, 2016) (JCER, 2019[32]).

The Fukushima prefectural government has been restructuring the economy, restoring sectors such as tourism and agriculture, but also targeting renewable energies and promoting digitalisation with the support of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry as part of the Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework. For example, Fukushima is the site of a major hydrogen demonstration project examining the possibilities of lowering the cost of hydrogen production as well as adjusting demand in the power grid by changing the production of hydrogen. This is achieved by a large solar energy facility (20MW solar photovoltaic) that can either produce electricity for the grid or produce hydrogen (by a 10MW electrolyser) for fuel cells and vehicles thereby storing the energy produced and reducing the intermittency problem. Other sectors receiving support includes medical, robot and drone-related industries. Fukushima is a major supplier of medical devices, both nationally and internationally, with new initiatives exploring how new technologies can help an ageing population. Support is also available in Fukushima for developing robots for use during disasters.

The government has made strong commitments to reduce emissions

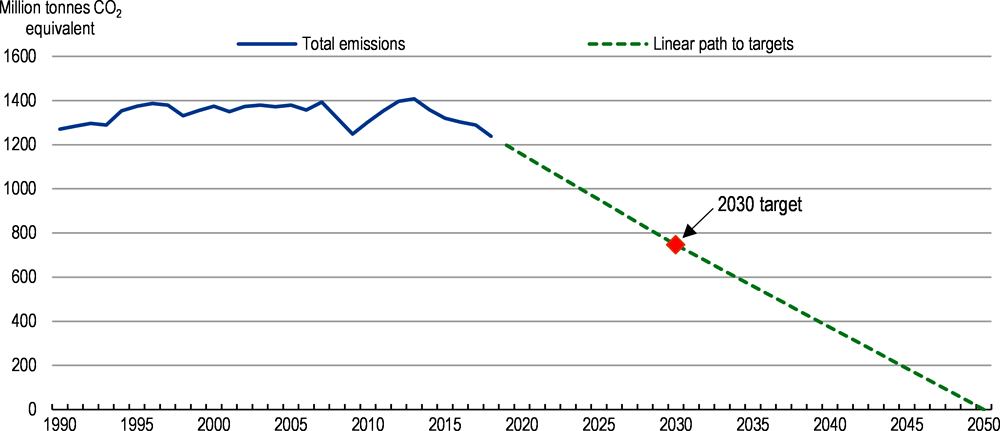

In 2020, the government committed to a net zero greenhouse gas emission goal by 2050. In 2021, it committed to a new intermediate target of reducing these emissions by 46% of the 2013 level in 2030 (and by 50% if possible), as against an original Paris Agreement target of a 26% cut (Figure 1.19). The intermediate target’s horizon is relatively close and major infrastructure projects to switch energy mixes will likely prove difficult to complete in such a timeframe if permits and licenses need to be secured. Such a switch is feasible as renewable generation facilities have relatively short construction times. However, - as discussed below - complementary investments in network infrastructure and demand-side management will be needed.

Successive governments have adopted a wide range of policies to reduce emissions. The Green Growth Strategy adopted in 2021 identifies 14 promising sectors that would contribute to meeting climate change targets (METI, 2021[33]). While OECD-wide analysis suggests that available technologies are sufficient to meet 2030 targets (IEA, 2021[34]), research and development is key as existing technologies are unable to deliver all the promised emission reductions to meet the net zero emission target by 2050. The government’s emission abatement plans are integrated into energy policy, which through a series of Strategic Energy Plans pursues energy safety, security, economic efficiency and environmental sustainability. Energy security is important given Japan’s reliance on imported energy. Furthermore, coal and natural gas remain important sources of supply which constrains mitigation options until the infrastructure is in place to expand significantly the share of renewables or carbon capture, utilisation and storage and mixed combustion technologies are available and cost effective.

Major efforts will be needed to meet climate goals

In the energy sector, some of the hardest choices need to be made to ensure meeting the net zero emission target by 2050. The Green Growth Strategy estimated that renewable generation could potentially cover 50-60% of total electricity generation in 2050, from around 17% in 2018 (METI, 2020[35]). While new policies are still being developed it is unlikely that they will be less ambitious. Japan’s renewable share is below the OECD average, although it has been increasing quite rapidly. This is particularly the case for photovoltaic power after generous subsidies were given (in the form of feed-in tariffs) from 2012. Japan had some of the highest feed-in tariffs in the world. As a next step, a system of support through a feed-in premium will be introduced in 2022 with the aim of better integration with electricity markets and continuing support for further expansion of renewables. The shift from a feed-in-tariff to a feed-in premium has occurred in other OECD countries as they expanded their renewable generation capacity. In addition, countries also use auctions to allocate support (IEA, 2018[36]), which can help ensure the level of support diminishes over time, when feasible, and also becomes technologically neutral (AURES, 2019[37]).

A major constraint to the expansion of renewable energy is the fragmentation of the electricity network into regional grids, which may be aggravated by additional renewable generation being sited away from the major demand areas. Indeed, offshore wind and the more experimental tidal generation capacity have just started to be developed. Japan is also unusual in that the grid developed using two different frequencies (60 Hz in the west and 50 Hz in the east) with limited interconnector capacity. A high share of intermittent supply and distributed generation is hard to balance in smaller networks, which limit pooling and allow for less flexibility, ultimately threatening network security and thereby putting constraints on the contribution from renewable generation. The authorities have begun to take stronger action to improve network resilience, as advocated in previous OECD Economic Surveys (OECD, 2019[6]). Reforms in 2020 introduced transmission charges to support investments in the transmission and distribution network and the feed-in premium to integrate renewable energy into the electricity market more effectively. These steps will strengthen the ability of the grid to deal with more supply from renewables. The previous OECD Economic Survey also advocated ensuring competition in the electricity market, as incumbents with market power have incentives to hinder the development of renewables (Dong and Shimada, 2017[38]). In order to ensure neutrality of the electricity transmission network, legal unbundling was introduced in 2020. The competition authorities will need to evaluate its impact. Further measures to increase competition, transparency and market liquidity may be needed. Harnessing digitalisation by making use of smart grids and by increasing demand flexibility may help to mitigate supply volatility of renewable energy supply and network constraints.

A second set of issues revolves around nuclear power. In order to meet the 2030 target, current plans assume that its share in energy generation rises to around 20-22%, replacing fossil fuels. Restarting more of the existing plants will require close adherence by the nuclear operators to the regulator’s demand to satisfy considerably strengthened safety and performance requirements as well as continuing efforts to reassure the public that the risks are understood and contained. The government in 2020 passed a further act that requires stricter accident-prevention measures for nuclear power. As of July 2021, the Nuclear Regulation Authority had granted permission to restart to 16 nuclear power plants, of which 10 have already started operations. The remaining six applications are being reviewed. In 2021, the Nuclear Regulation Authority blocked the restarting of one nuclear power plant due to safety concerns. Research and development of new nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors is underway. With improved safety and performance features, they could contribute to reducing emissions.

Other options in the energy sector are contingent on the outcomes of ongoing research and development:

Hydrogen and ammonia are options and already a number of applications exist, but currently they are relatively expensive. Japan is one of the first countries to develop a hydrogen strategy and a number of demonstration projects are underway. Plans to reduce costs by one third, making it competitive with natural gas, would allow hydrogen to replace fossil fuels in sectors such as transportation and industry. In addition, ammonia, as well as hydrogen, can be used for power generation and maritime transport. Ammonia can be used for power generation by remodelling existing thermal power plants (co-firing) and thereby contribute to decarbonisation, while providing stable electricity supply and avoiding lock-in. Ammonia can be supplied at lower cost than hydrogen due to the existing raw material transportation and storage networks for the production of goods such as fertilisers. The Green Growth Strategy estimated that hydrogen and ammonia generation could potentially cover about 10% of total electricity in 2050. France and Germany have also launched plans in this area, including subsidies to support the roll-out of fuel cells in transport. In France, the support measures during the pandemic targeted “green” hydrogen – producing hydrogen when electricity supply exceeds demand thus storing electricity. A similar approach is being trialled in Fukushima (Box 1.5), which could be extended to help balance electricity markets as hydrogen costs fall.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage is another largely experimental option, but by 2050 its roll-out could allow coal-fired power to contribute to meeting a sizeable, though as yet undetermined, share of electricity demand. Due to Japan’s current heavy reliance on fossil fuels to provide baseload power, the costs of switching totally out of these in a relatively short time span, by means other than a restart of a larger share of its nuclear fleet (currently nuclear generation accounts for around 7½ per cent of electricity production), would be extremely high. The average age of the coal-fired fleet is estimated to be around 25 years, whereas the normal retirement age is around 40 years (Climate Analytics and Renewable Energy Institute, 2018[39]). The government estimates that replacing inefficient coal-fired generation plants with newer ones with capture carbon could also reduce emissions over and above the gains in generation efficiency. However, the impact of the proposed recycling - for example to methane to be used as a fuel or as a chemical fertilizer – on emission reduction remains uncertain (IEA, 2021[40]). As such, major investment in new coal-fired capacity should be contingent on progress in developing new decarbonisation technologies - such as carbon capture utilisation and storage and ammonia co-firing - and cost-benefit analysis.

Achieving emission reductions in the transport sector will likely require further investment. The government currently supports emission reductions from the car fleet through a mix of tax incentives and purchase subsidies. The Japanese automotive industry has pioneered electric (hybrid or purely electric) and hydrogen-based vehicles using fuel cells, and is both a major global supplier and a large domestic market. Expanding the charging infrastructure is needed to make greater use of electric vehicles, which is supported by a subsidy for their installation. Indeed a major expansion of battery electric vehicles or plug-in hybrid electric vehicles is envisaged to around 20-30% of the automotive fleet in 2030 (IEA, 2021[40]). In the medium term, the development of fuel cell vehicles is envisaged. Production capacity for hydrogen-powered vehicles is currently small and the network of hydrogen stations for fuel cell vehicles is only just beginning to be established. Government support policies in this field should periodically assess their contributions to emission reductions to prevent marginal abatement costs diverging and thereby increasing the overall costs of emission reduction. The experience of other countries suggests that in some cases actual reduction achieved in operational settings can be quite different from ex ante expectations (Plötz, Funke and Jochem, 2018[41]).

Making more use of market-based instruments

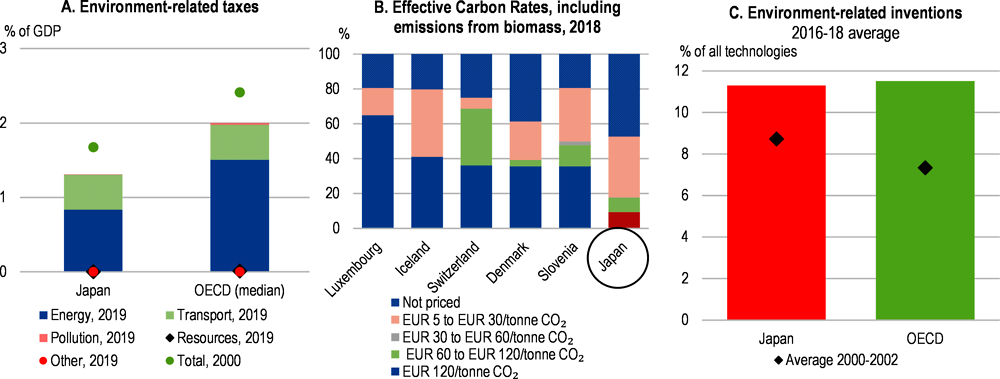

Energy and climate policy has often taken a regulatory approach complemented with voluntary agreements with major private sector actors. Periodic systematic and transparent evaluation of marginal abatement costs is called for to ensure that the policies being developed are not excessively costly. Market-based instruments are relatively less used, although a carbon tax exists (Figure 1.20). However, the effective carbon rate - which assesses the combined impact of fuel excise taxes, carbon taxes and emission permit prices - is relatively low in comparison with other OECD countries (the share of energy-related carbon emissions priced at a EUR 60 per tonne of CO2 benchmark stood at 24% in 2018 (OECD, 2021[42])). Furthermore, like in other countries, a slew of exemptions means that many emissions are not subject to a carbon price and that effective rates vary by sector. The specific climate change mitigation tax rate of JPY 289 (USD 2.72) per tonne of CO2 is one of the lowest rates in the OECD and has a rather narrow base covering coal and petroleum (when taking into account other energy taxes the price per tonne of CO2 would rise to JPY 4057 – or around EUR 30), which is lower than the OECD average of around EUR 50). On the other hand, the high level of support offered by feed-in tariffs has pushed up the price of electricity. Some prefectural governments have implemented their own measures, such as the linked emission trading schemes in Tokyo and Saitama, and other cities have adopted their own climate change goals. The emission trading schemes are rather small as they exclude manufacturing and the residential sector.

Given the major infrastructural requirements for making the energy sector transition to meet the net zero emission target, government spending will need to remain elevated in this area. As the government also needs to ensure fiscal sustainability, making more use of market-based instruments is warranted. Not only will they generate revenue (at least in the short to medium run), and thus contribute to both environmental and fiscal sustainability, but they will also help minimise the costs of reducing emissions. The government is currently evaluating the options of using market-based instruments, such as carbon taxes, emission trading schemes or carbon credit markets, as part of a broader strategy. A voluntary trading system (the J-Credit Scheme) is already in place for some companies and local authorities, wherein the government certifies emission reductions, which could provide a basis along with the existing carbon tax and regional trading schemes to develop policy further. Experience in other countries suggests that effective carbon rates in trading systems need to be higher and more stable to make a durable contribution to abatement (OECD, 2021[42]). As such, design will be important and will need to consider auctioning the permits.

Market-based instruments are important but unlikely to meet emission objectives on their own. The rise in tax rates needed to reduce emissions where demand is inelastic in the short run can be penal (Heal, 2020[43]). In these cases, short-run adjustment costs can be extremely high for households and firms, which introduces political constraints. Furthermore, electricity prices are already relatively expensive for end users in Japan, which may hinder a move to greater reliance on electricity. Against this background, easing adjustment costs with subsidies (while preserving incentives to reduce emissions), investing in R&D, and the use of regulation all play an important part of an overall policy. Regulation, such as energy efficiency requirements, has already contributed to high levels of energy efficiency in Japan. Elements of the Green Growth Strategy are in line with a multi-prong strategy. Nonetheless, cost-benefit analysis is required to ensure that overall costs are minimised.

While significant fiscal support appears to have cushioned the blow, the shock of the pandemic on households was sizeable. Limited capacity to conduct administrative procedures online, by both households and government, and the poor integration of government databases hindered getting support to the most vulnerable workers and households. It is likely also leading to widening inequality. The rise of single-person households and nuclear (not multigenerational) families leaves many households exposed to income shocks, even as poorer households have fallen behind in recent decades (adjusting for household composition) (Hori, Maeda and Suga, 2020[44]).

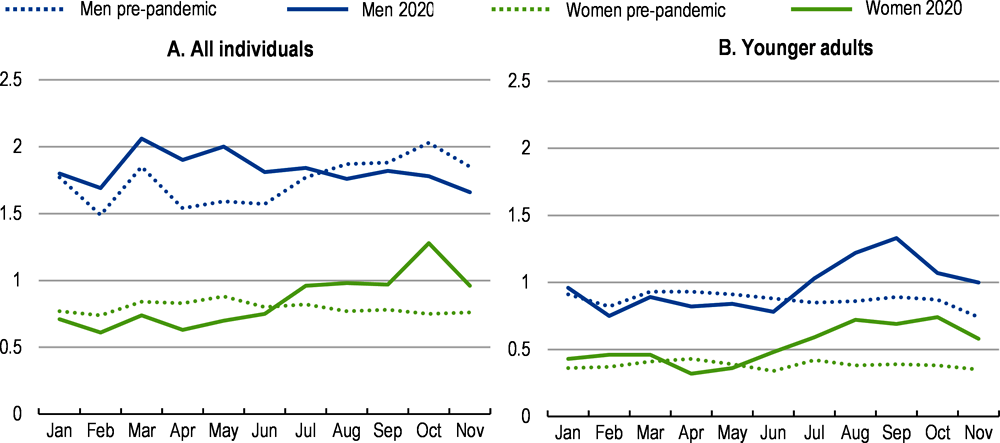

As the pandemic wore on, the suicide rate rose during 2020 and by the end of the year was significantly higher than in the pre-pandemic period (Sakamoto et al., 2021[45]). By contrast, the suicide rate in the United States fell in 2020 (Ahmad and Anderson, 2021[46]). The increase in suicides in Japan was notable for women and younger adults, although their rates of suicide are lower (Figure 1.21). These groups are over-represented (given their population shares) in the sectors facing the largest pandemic-related shocks, such as restaurants and tourism, and are also more likely to be in non-regular employment and thus exposed to greater employment precariousness.

The pandemic raises the risk of another so-called ice age generation (Ohta, Genda and Kondo, 2008[47]). In past recessions, the failure of newly-minted graduates to enter employment has resulted in persistent relatively poor labour market performance over time by that cohort with lower wages and less secure employment outcomes. This underscores the need to secure a strong recovery and help this group into work or provide them additional training, notably to improve their digital skills.

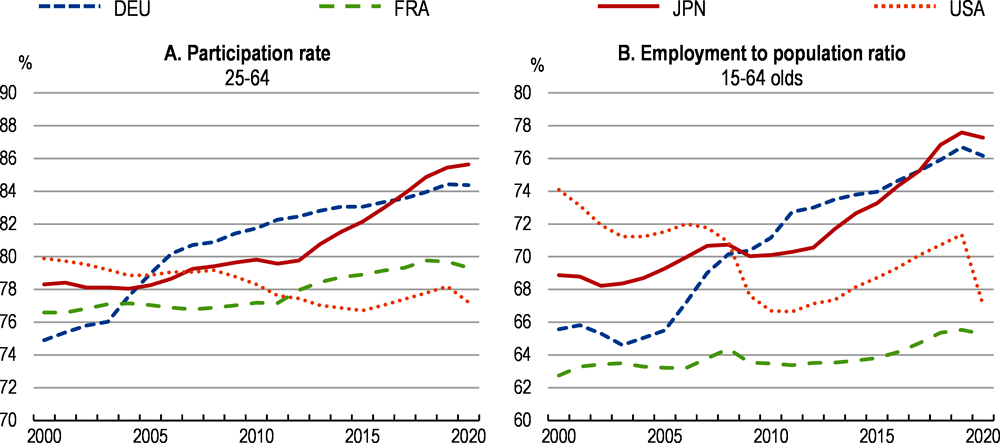

The worsened labour market conditions mark a setback from the 2018 Work Style reforms and previous labour market reforms that were beginning to have some effect in conjunction with underlying trends towards increased participation and macroeconomic policy support (Kawaguchi, Kawata and Toriyabe, 2021[48]). Efforts to raise the compulsory retirement age that firms set for their own employees (OECD, 2017[49]), which has been at quite early ages, were starting to pay off. In addition, empirical evidence links reforms to expand social insurance coverage to non-regular workers with increased participation and hours worked (Yamada and Mehr, 2021[50]). The impact of the reforms appeared to offset pressures from ageing, with Japan now having one of the highest participation rates amongst G7 countries (Figure 1.22). Participation rate increases for elderly cohorts are even more pronounced. The rise in the employment-to-population ratio is also amongst the highest along with Germany, which made substantial progress in raising participation among the elderly following the introduction of labour market reforms in the early 2000s (Turner and Morgavi, 2020[51]).

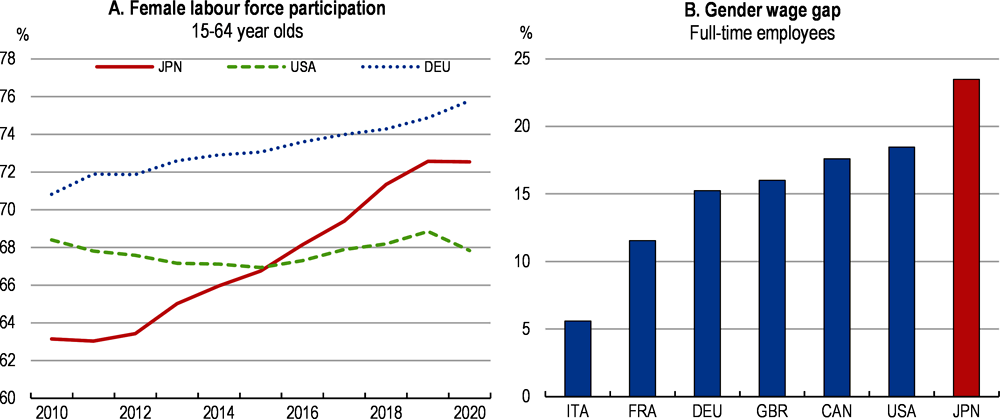

In addition to the elderly’s, women’s labour force participation has risen quite strongly (Figure 1.23). The government has sought to improve working conditions for women. For example, limits on working hours and the provision of childcare places had pronounced effects on labour supply by young mothers helping them remain in and return to employment (Nagase, 2018[52]). More recently, the number of childcare facilities has been increased further, partially funded by revenues raised from the consumption tax hike in 2019. Demand for childcare places remains unmet and places are rationed. Other measures included enhancing the attractiveness of the parental leave system, which often acts as a barrier to participation in other countries as well (OECD, 2016[53]). However, take-up is still far from complete, especially by fathers. In addition, central government, local governments and employers with over 300 regularly employed workers (from April 2022 this requirement will be extended to employers with over 100 workers) are required to establish gender action plans and disclose related information. Such actions are now promoted in the Corporate Governance Code, following revisions in June 2021. The revision requires listed companies to publish their policies and measurable voluntary goals for ensuring diversity in middle-management positions, including the promotion of women. Although the gender pay gap remains pronounced for Japan, it has been falling gradually from around 33% at the beginning of the century. These initiatives and the recently enacted Work Style reforms, by capping overtime hours and encouraging equal pay for equal work, will erode further some of the remaining disincentives for women to participate and raise their relative earnings.

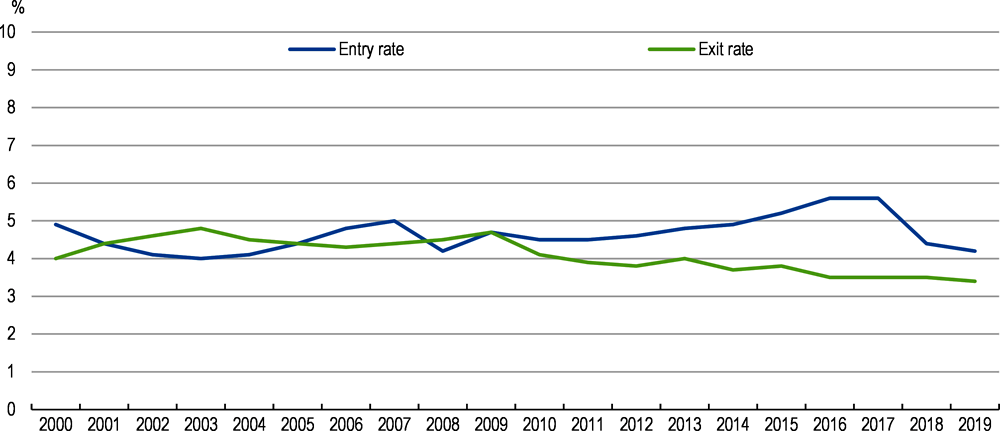

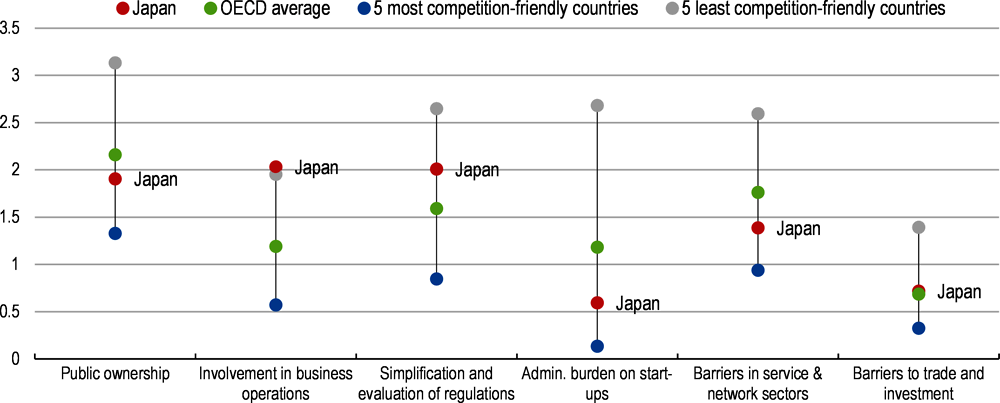

While employment has continued to expand, so has the share of part-time and non-regular employment, aggravating labour market dualism. Non-regular workers, such as temporary employees, are often the margin for adjustment during a shock because layoffs of regular workers can be very expensive. The recent Work Style reforms, including by encouraging equal pay for equal work, have begun to erode the dualism. Indeed, the number of women in regular employment had been increasing steadily, including during the pandemic. But more can be done to promote greater labour market dynamism. Previous OECD Economic Surveys have recommended reducing employment protection for regular workers (by lowering the costs of dismissal for these workers), expanding social insurance coverage and training for non-regular workers, avoiding that workers have to leave the labour force to care for children or elderly relatives and capping the number of hours worked (OECD, 2019[6]). Reducing dualism further would help augment pensions, facilitate greater labour mobility (particularly if career track programmes diminished in importance and mid-career mobility and re-entry of caregivers into regular contracts was supported) and reduce the current training disparity between regular and non-regular workers.

Pension system reforms in early 2021 help in this respect. Following on from earlier reforms that expanded the coverage of Employees Pensions Insurance (EPI) to include part-time workers in firms with more than 500 workers (OECD, 2019[6]), the new reform reduces that threshold to firms with over 100 employees and then 50 employees, which could bring another 650,000 workers into this pension system. Moreover, deduction of pension insurance contributions at source under the EPI would prevent non-regular workers from failing to pay their contributions, which is currently an issue. Non-regular workers covered by the EPI would have higher contribution rates and benefit from the employer’s pension contributions and thus enjoy higher retirement income in the future. The government should strengthen measures to reduce the number of firms that fail to pay the employer share of pension contributions.

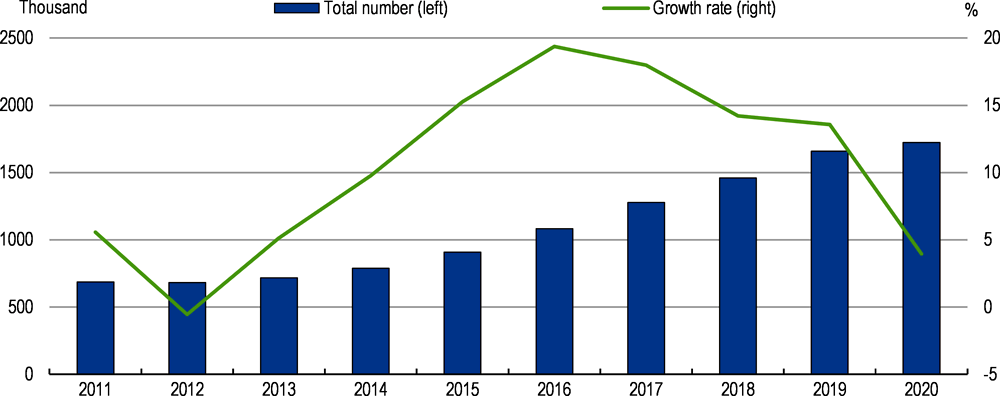

On current projections, the pressure on the labour market from ageing will peak during the 2050s. Efforts to mitigate this effect on labour supply involve continuing to implement the recent reforms, carrying out plans to raise the mandatory retirement age of civil servants and introducing actuarial adjustments to deferred pensions. In addition, improving older workers’ training and skills will help preserve attachment, particularly in an era of technological disruption associated with the digital transformation. Providing training is more of a challenge for non-regular workers, for whom firm-based training is often limited. At present, though improvements are being made, there are still disincentives to participation for second earners embedded in pensions and healthcare, such that some dependent spouses can also benefit without making contributions. Removing these implicit subsidies for non-participation would further support greater labour market participation. Finally, against the background of an ageing and shrinking population, boosting the number of foreign workers can help raise labour supply. Given strong labour demand and policy changes, foreign worker inflows increased substantially in recent years (Figure 1.24). The government introduced the Points-Based System for Highly-Skilled Foreign Professionals in 2012. In addition, further progress on this front has been made with the Specified Skilled Worker System that was introduced in 2019 to extend the coverage for foreign workers with specific skills and expertise, but immigration flows have remained relatively low and halted during the pandemic. As a result, the number of Specified Skilled Workers remains considerably short of initial estimates (around 32 thousand as of July 2021 against 345 thousand expected by 2024). The government should continue to build on current immigration policies to increase labour supply.