Korea

GDP growth is projected to decline to 1.5% in 2023 before picking up to 2.1% in 2024. China’s recovery should boost exports over time. Private consumption and investment will remain weak in the near term in response to higher interest rates and a sluggish housing market, but will pick up gradually in 2024. Inflation will continue to decline, but only moderately, with utilities and services price adjustments yet to come. Employment is set to contract from high levels and unemployment to rise from historical lows.

The Bank of Korea has appropriately maintained the policy rate at 3.5% since January 2023 and signalled a data-driven approach going forward. Fiscal consolidation should proceed in view of rapid ageing, in line with the proposed fiscal rule. Support to households should become increasingly targeted to those that are not sufficiently protected by permanent social protection schemes. Structural reforms should facilitate the reallocation of labour and capital to expanding sectors and address high social protection gaps.

The economy has slowed

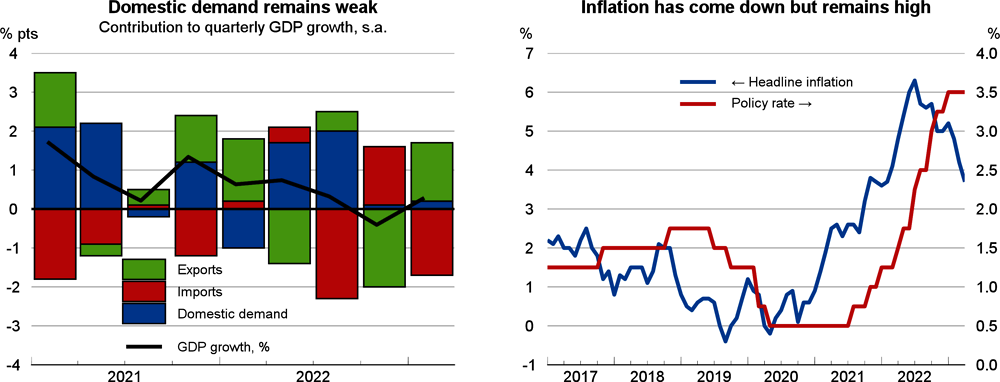

Real GDP grew by 0.3% in the first quarter of 2023, after a contraction in the previous quarter. Private consumption picked up, led by in-person services as the last pandemic curbs were lifted. High inflation and interest rates dragged down private investment. Exports and imports rebounded after a deep contraction in the fourth quarter of 2022. Headline inflation fell to 3.7% in April 2023, and core inflation remained largely unchanged at 4.0%, with services and utility prices increasing. Job creation has slowed after robust gains in 2022.

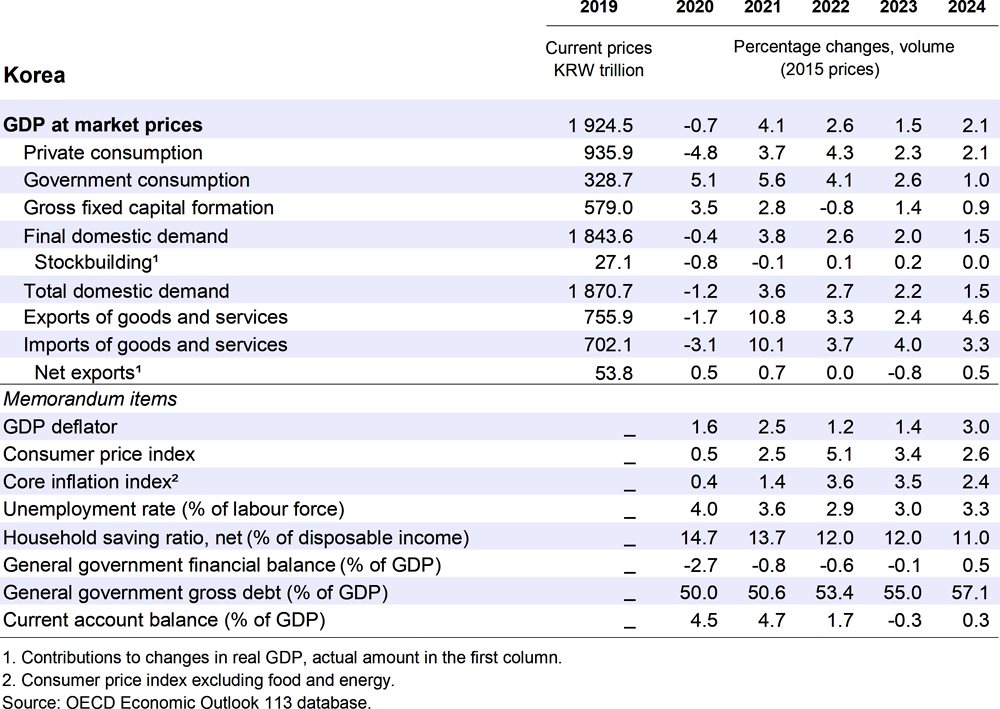

Korea’s direct trade with Russia and Ukraine is limited, but rising energy and food prices pushed up inflation. A slowdown in global demand, notably for semiconductors, has dampened exports considerably, along with sluggish demand from China in late 2022. Together with a weak exchange rate since early 2022, notably against the US dollar, this has resulted in a trade deficit. Recent global bank failures have impacted financial conditions in Korea only very modestly so far.

Macroeconomic policies are being tightened

After raising the main policy rate ten times from 0.5% in August 2021 to 3.5% in January 2023, the Bank of Korea has kept it on hold. The policy rate is assumed to remain at the current level until the second half of 2024 by which time inflation is projected to be close to the 2% target. Fiscal policy will tighten in 2023 on the assumption that supplementary budgets will be avoided, which will work in the same direction as monetary policy. The 2023 budget cut the managed budget deficit (excluding social security) from 5.1% of GDP in 2022 to 2.6% of GDP by scaling back discretionary expenditures. The fiscal stance is assumed to be slightly contractionary in 2024, in line with the government’s fiscal consolidation plan.

Growth is projected to weaken

Real GDP growth is expected to slow to 1.5% in 2023, before rebounding to 2.1% in 2024. Exports are set to pick up with China’s recovery. Elevated debt servicing burdens and a sluggish housing market will continue to weigh on private consumption and investment in the short term, but demand growth should strengthen in 2024. Inflation will gradually moderate but remain above target, as planned increases in service and utility prices have been postponed until the second half of 2023. Further global financial turmoil could increase the household debt servicing burden and trigger volatility in financial markets. Increasing geopolitical tensions may lead to realignments of Korean supply chains. A stronger than expected recovery in China and easing geopolitical tensions would improve the economic outlook.

Structural challenges call for policy action

Against the backdrop of rapid population ageing, fiscal consolidation should proceed. The proposed fiscal rule, which caps the managed budget deficit at 3% of GDP, would help to limit the build-up of fiscal pressure. The pension reform to be announced in the second half of 2023 should help to secure adequate retirement income and fiscal sustainability. The government recently extended a temporary fuel tax cut until the end of August 2023 to ease living costs. It would be better to target vulnerable groups more directly, notably by addressing gaps and weaknesses in the social safety net, and enhancing incentives for energy savings. Stepping up training and activation policies for those who lose their job and strengthening the social safety net would facilitate workforce reallocation. Reducing the stringency of product market regulation would help to lower productivity gaps between large and small firms and reduce labour market dualism. Policies should also focus on reconciling career and family, including greater public financing of parental leave and expanding after-school care to boost female employment and fertility. To further reduce GHG emissions, Korea’s emission trading scheme should be aligned with climate targets.