Executive Summary

Switzerland has been resilient through the pandemic and the turmoil in energy markets that followed Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Nevertheless, the economy is facing uncertain prospects amid tightened financing conditions and slowing global growth.

Economic activity has slowed. Weak foreign demand, tighter financing conditions and heightened uncertainty weigh on the economy. Manufacturing production has stalled and prospects are subdued. Economic sentiment remains low.

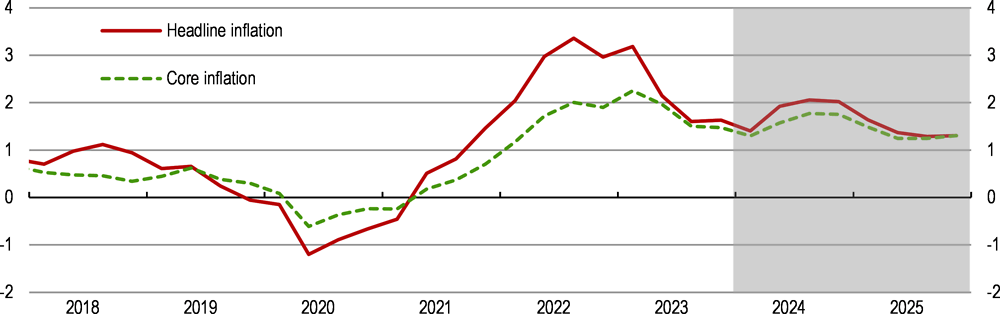

Inflation has returned within the 0-2% target range, but inflation pressures remain. Import price inflation has retreated, but inflation of domestic goods and services remains elevated. Short-term inflation expectations remain at the upper side of the 0-2% range. The labour market is robust with the unemployment rate around 4% and vacancies at high levels. Real wages continue recording negative growth.

Real GDP growth is projected to remain below potential in 2024 before picking up in 2025. A tight monetary policy stance internationally as well as domestically will still weigh on global activity and on domestic demand. Inflation will rise temporarily above 2% over the course of 2024, pushed by expected rent and electricity price increases, before moderating towards the beginning of 2025. Domestic consumption growth will be subdued. The unemployment rate will increase slightly to 4.4% in 2025.

Uncertainty surrounding the outlook is high. Inflation might turn out more persistent than expected, requiring further monetary tightening, with risks surrounding household indebtedness, repricing of real estate and repercussions on financial stability. Energy shortages or renewed energy price spikes could further slow the economy. On the other hand, favourable resolution of geopolitical tensions could result in higher trade, revived confidence and higher growth and stability.

Monetary policy has been appropriately tightened. However, inflation is expected to return temporarily above the 0-2% target and inflation expectations remain at the upper end of the target range. Elevated interest rates globally and weak activity heighten risks and vulnerability in the financial system.

Between June 2022 and June 2023, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) hiked the policy interest rate by 250 basis points, from -0.75% to 1.75%. To tighten monetary conditions, the SNB has been selling foreign exchange over recent quarters. As a welcome side effect, this has contributed to reducing the outsized balance sheet of the SNB.

The acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS effectively safeguarded financial stability but raises new risks and challenges. UBS – already a global systemically important bank before the merger – has become even larger and it has been given a transition period until 2030 to meet the progressively higher capital requirements of the “too big to fail” (TBTF) regulations. The acquisition was made without making use of the existing TBTF resolution regime, raising questions on optimal regulation and supervision of large banks going forward.

The housing market has started showing signs of cooling, but vulnerabilities remain. Growth in prices of real estate has started abating after years of steep growth. Property is estimated to be overvalued by up to 40%. Large interest rate hikes or other shocks could result in steep price corrections, leading to deteriorated mortgage portfolios of banks.

Fiscal policy is facing hard choices, despite low public debt and a return to fiscal surpluses. Population ageing, the need to tackle climate change, an increase in defence spending and rising interest rates on public debt are all putting pressures on public finances. Reforms to rein in public spending and to increase public revenues are needed.

A broadly neutral fiscal stance is warranted to sustain the moderately growing economy. Automatic stabilisers should operate freely to cushion the growth slowdown. The decision to extend the amortisation period for reducing the “COVID debt” will avert overly tight fiscal policy over the coming years.

A substantial pension reform is overdue. Ageing is putting pressures on age-related costs (pension, healthcare and long-term care) and weighs on employment and growth. A recent reform gradually raises the retirement age of women to 65 and secures higher revenues to the pension fund but this will only temporarily delay pressures. The ratio of retirees to employees is set to soar and pension replacement rates for the mandatory pension system are set to drop significantly over time. Under current policies, time spent in retirement will be longer. Adapting parameters of the pension system to rising longevity can slow the rise in expenditures.

Strengthening tax revenues can also help to safeguard fiscal sustainability while meeting growing spending needs. Switzerland relies more on direct taxation, notably personal income tax, than most other OECD countries. VAT revenues are among the lowest in the OECD and revenues from taxation of immovable property are also low.

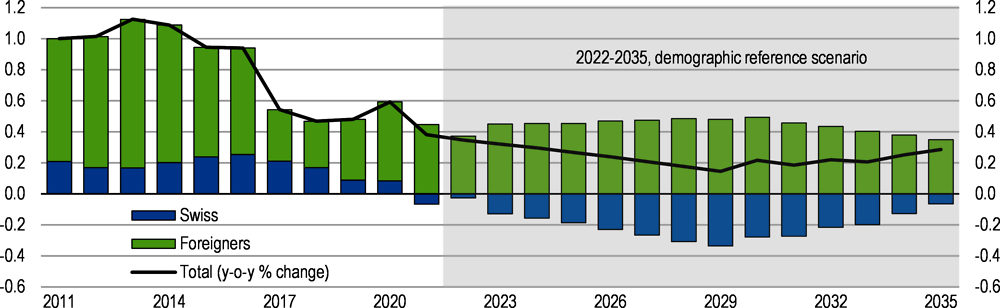

The Swiss labour market boasts high employment rates and low unemployment. However, labour and skills shortages are rising and are increasingly becoming a structural issue. Rapid population ageing and a preference shift towards shorter working hours weigh on future economic growth. For some groups, such as mothers and older workers, there is potential to increase participation.

Bringing more mothers to work full time will help ease shortages and reduce the sizable gender income gap. A high labour participation rate of women masks a remarkably high incidence of part-time work, among mothers in particular. The interplay between the tax and benefit systems and high costs of childcare result in strong disincentives to work for second earners, notably mothers. Low supply of affordable childcare exacerbates the issue.

A range of disincentives and barriers contribute to early retirement and low uptake of work by older workers. After the age 65, the employment rate shows a steeper decline than in OECD peers. A significant share of workers retire before 60. Once unemployed, older workers find it more difficult to find a new job. Financial disincentives for employers also weigh on the employment of older workers, as rising pension contribution rates make employing older workers costly. Incentives within the pension system and more flexibility to combine retirement and work can encourage more workers to work longer.

Immigration is key for Switzerland’s economy in terms of labour and skills. Over the past two decades, net migration has been persistently positive. The foreign-born population represents 30% of the total population, the second highest share in the OECD. Skilled immigrants from non-EU/EFTA countries will become increasingly important to counter declines in the domestic population. Active steps should be taken to maintain Switzerland as a top destination for global talent. Better welcoming skilled migrants and easing the transition to permanent settlement can improve social and labour market integration and ease labour shortages.

Switzerland as an Alpine country is strongly impacted by climate change. Growth has decoupled from emissions and energy use, but emission reductions will have to accelerate markedly if Switzerland is to meet the net-zero target by 2050. The existing policy mix is comprehensive but needs strengthening to reach net zero.

Switzerland imposes high carbon prices in international comparison. However, the CO2 levy and the mineral oil tax, fixed in nominal terms, are set to be eroded in real terms over time, which is not consistent with the need to accelerate emission reductions. Carbon prices are cost effective and efficient instruments to reduce emissions. A higher carbon tax or stronger incentives within an emission trading system could strengthen incentives to lower emissions in buildings, industry and road transport.

Comprehensive further electrification of the economy will be required to reach climate neutrality. Production of electricity will have to increase, requiring steep investment into renewables such as solar and wind, whose electricity output should rise 8-fold to 2035. The recently revised Energy Act has secured incentives for investment up to 2035 through pricing instruments and investment support. Reduced red tape and faster approval processes for building new capacity as well as upgrading the electricity grid can boost further the needed investment into renewables.

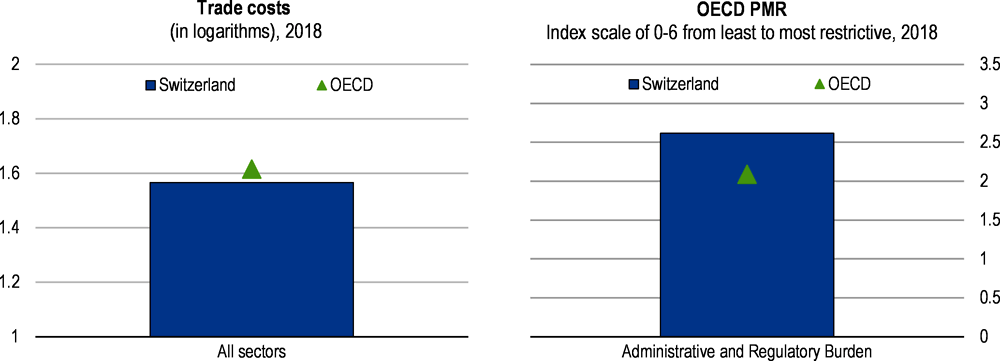

Geopolitical tensions and a global shift towards protectionism and large-scale industrial policy programmes pose challenges. Industrial policy programmes can be costly, are often ineffective and distort trade, undermining competitive markets. Switzerland should strengthen its resilience and productivity by staying committed to the rules-based trading system, strengthening ties with key trading partners and enhancing domestic competition.

Switzerland has shown remarkable strength during previous economic downturns. Its adaptable economy, effective macroeconomic stabilisation tools, and robust fiscal framework have led to shallower recessions, lower impact on household incomes and faster recoveries compared to OECD peers. A comprehensive risk planning and monitoring system, including essential-goods stockpiles to bridge supply disruptions, has proved robust during periods of severe shortages. Having the private sector at the centre-stage in such efforts facilitates adaptability and flexibility.

Sustained trade and economic partnership with the EU remain key. The Switzerland-EU partnership is at risk of eroding. Negotiations on an encompassing “framework agreement” came to a standstill in 2021. Resuming negotiations is imperative to secure cooperation and ensure continued access to its key trading partner. Failing to find an adequate alternative would be harmful for Switzerland’s external trade and competitiveness, with repercussions for productivity and resilience.

Reduced barriers to cross-border trade and a lower administrative burden can spur competition, productivity growth and raise resilience. There is room to strengthen trade facilitation measures and reduce costs of trade further. Border processes and procedures can be digitalised and thus become less onerous, lowering the cost of trade. Swiss businesses still face a high administrative burden. Less red tape would boost growth