Suicide

Suicide is a significant cause of death in many OECD countries, and accounted for over 150 000 deaths in 2014, or 12 suicides per 100 000 people. There are a complex set of reasons why some people choose to attempt or commit suicide, with multiple risk factors that can predispose a person to attempt to take their own life.

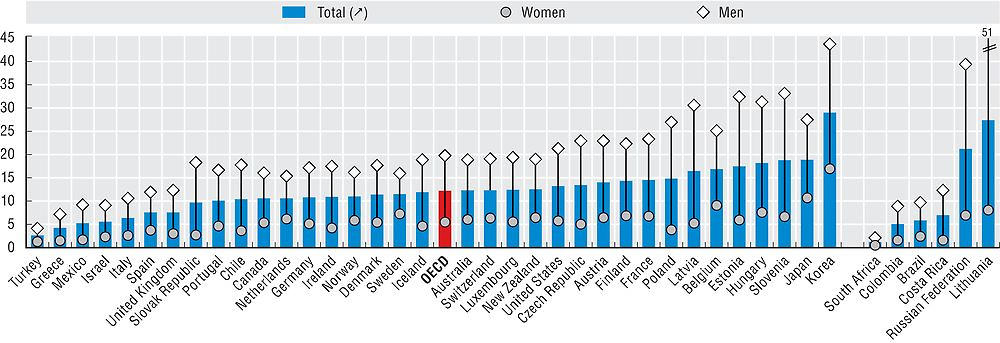

In 2014 suicide rates were lowest in Turkey, Greece, Mexico, and but also in South Africa and Colombia, at five or fewer deaths per 100 000 population (Figure 6.6). In Hungary, Slovenia, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania and the Russian Federation, on the other hand, more than 18 deaths per 100 000 population were caused by suicide. There is a eleven-fold difference between Turkey and Korea, the two countries with respectively the lowest and highest suicide rates. However, the number of suicides in certain countries may be under-reported because of the stigma that is associated with the act, or because of data issues associated with reporting criteria.

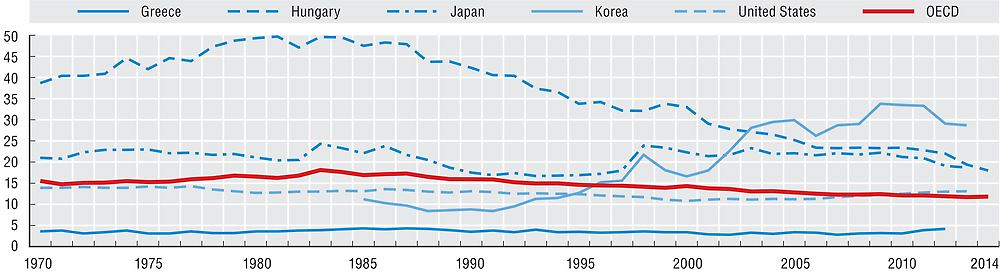

Suicide rates increased in the 1970s and peaked in the early 1980s (Figure 6.7). Since the mid-1980s, suicide rates have decreased by around 30% across OECD countries, with pronounced declines of over 50% in Hungary for example. On the other hand, death rates from suicides have increased in countries such as Japan and Korea. In Japan, there was a sharp rise in the mid- to late 1990s, coinciding with the Asian financial crisis, but rates have started to decline in recent years. Suicide rates also rose sharply at the same time in Korea until 2011.

Previous studies have shown a strong link between adverse economic conditions and higher levels of suicide (Van Gool and Pearson, 2014). Suicide rates rose slightly at the start of the economic crisis in a number of countries, but more recent data suggests that this trend did not persist. In Greece and Spain, overall suicide rates were stable in 2009 and 2010, but have increased since 2011 from very low levels. This underlines that countries need to closely monitor high-risk populations such as the unemployed and those with psychiatric disorders.

Death rates from suicide are three-to-four times greater for men than for women across OECD countries (Figure 6.6). In Poland and Slovak Republic, men are at least six times more likely to commit suicide than women. While the gender gap is smaller in Netherlands and Sweden, male suicide rates are still at least twice as high as those of females.

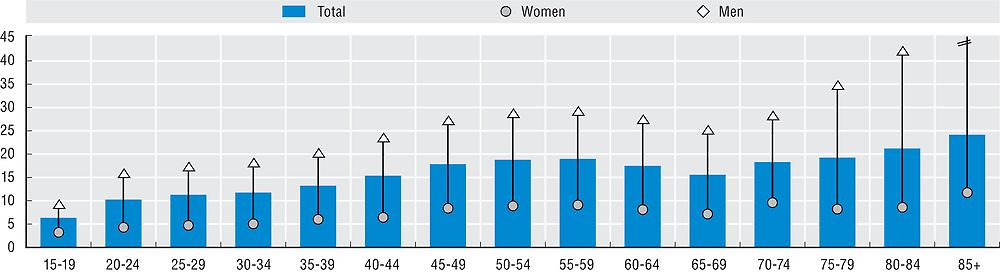

On average, older people are more likely to take their own lives, with 20 people aged 70 years or more per 100 000 (Figure 6.8), but this pattern is not general across the OECD. Austria, France, Germany, Hungary and Korea are examples where older people take their own lives more often than young people. The largest increasing age gradient is found in Korea, where rates amongst the eldest group are almost 15 times higher than those of teenagers. Differences in suicide rates between men and women become particularly important from 75 years old, where suicide rates are six times greater for men than for women. This pattern may reflect higher social isolation, possibly following ending of a long term partnership by dissolution or death, of older men compared to older women. It could also come from higher incidence of diseases among men leading to suicides.

Except in a few countries, youth are much less likely to commit suicide with only 9young people aged between 15 and 29 years out of 100 000. However, in a minority of OECD countries like Ireland, New Zealand and Norway, young people are more likely to take their own lives than older people. Suicide rates among under 30s are highest in Finland, Japan, Korea and New Zealand, with 15 or more suicides per 100 000 youth. They are lowest in Mediterranean European countries and Luxembourg.

The World Health Organization defines suicide as an act deliberately initiated and performed by a person in the full knowledge or expectation of its fatal outcome. Comparability of data between countries is affected by a number of reporting criteria, including how a person’s intention of killing themselves is ascertained, who is responsible for completing the death certificate, whether a forensic investigation is carried out, and the provisions for confidentiality of the cause of death. Caution is required therefore in interpreting variations across countries.

Mortality rates are based on numbers of deaths registered in a country in a year divided by the size of the corresponding population. The rates have been directly age-standardised to the 2010 OECD population to remove variations arising from differences in age structures across countries and over time. The source is the WHO Mortality Database. Deaths from suicide are classified to ICD-10 codes X60-X84.

Further reading

OECD (2015), Health at a Glance 2015 – OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2015-en.

Van Gool, K. and M. Pearson (2014), “Health, Austerity and Economic Crisis: Assessing the Short-term Impact in OECD Countries”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 76, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxx71lt1zg6-en.

Figure notes

Figures 6.7 and 6.8: See Statlink for precise latest years ranging from 2009 and 2014.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en and OECD Secretariat calculations form WHO Mortality Database.