1. Enhancing the effectiveness of the office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life of Malta

This chapter analyses the institutional and procedural set-up of the office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, the human and financial resources of the office, and the organisational culture. This chapter examines the Commissioner’s core functions, including on investigations as well as in strengthening capacity and raising awareness on integrity amongst officials covered by the Standards in Public Life. This chapter also provides recommendations on strengthening integrity measures in the office of the Commissioner.

Worldwide, no two parliaments are the same. They differ in form, role and functioning, as they are shaped by each country’s own history and culture. Yet parliaments have a set of common functions that aim at giving citizens a voice in the management of public affairs. In this sense, as the highest legislative authority of any government, parliaments carry out four major functions:

To legislate – that is, to examine, debate, and approve new or amended laws.

To set the budget – that is, to approve the collection of taxes and other revenue, and to authorise government spending.

To scrutinise the work of the government (Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, 2016[1]).

The four functions of the legislative body can only be effective insofar as the actors who make up and serve the legislative branch, including both elected and appointed officials, are committed to and held responsible for protecting and upholding the public interest. In particular, this requires establishing effective values and standards to guide behaviour, as well as oversight mechanisms that ensure accountability for the actions taken by such officials.

Accountability can be realised by ensuring answerability, that is, the obligation for elected and appointed officials to provide clarification, explanation or justification for their actions when concerns are raised about breaches of the standards; and enforcement, that is, the ability to take formal action against illegal, incorrect or unethical conduct. Yet overseeing and enforcing standards of conduct of members of parliament presents several unique challenges. First, what standards of conduct should be expected of elected and appointed officials? Second, when these standards are breached, what institutional mechanisms and attributes are needed to effectively oversee these officials?

These challenges emerge in part because of the accountability role that these actors have over government, and in part because of parliamentary privilege; that is, the notion that members of the legislative branch are free to regulate their own conduct in their respective assemblies, without interference from outside bodies (particularly the Executive and the courts). This privilege is meant to ensure that members of the legislative branch can speak freely while carrying out their role, e.g. when they are voting or promoting legislative initiatives. Such privilege is fundamental to the legislative branch’s autonomy and independence, and to its ability to carry out its roles of representing constituents and scrutinising executive power (OSCE, 2012[2]).

Yet, “when trust, respect and confidence in elected representatives is damaged, it is incumbent on the democratic legislature […] to steel its nerve and provide leadership around standards of conduct which the public expect” (House of Commons Committee on Standards, 2022[3]). This organisational review is concerned with how that leadership should play out in practice: what institutional mechanisms and attributes should the legislature set out to oversee officials, how should the institutions be established and organised, and what should the core responsibilities be? In particular, this review looks at the legislative, institutional and organisational set-up of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life (herein “the Commissioner”) and his office.1 The role of the Commissioner was created in 2017 by the Standards in Public Life Act (Chapter 570 of the laws of Malta), and the current incumbent was appointed in October 2018. The role of the Commissioner was created with the aim of enforcing the integrity standards amongst Members of Parliament (MPs), Ministers, Parliamentary Secretaries, Parliamentary Assistants and persons of trust. Amongst its responsibilities, the Commissioner is in charge of examining the declarations of income, assets, interests and benefits, investigating breaches of any statutory or any ethical duty, and making recommendations on ethical matters including on lobbying, acceptance of gifts, the misuse of public resources and confidential information.

This chapter analyses the institutional and procedural set-up of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life and his office, the human and financial resources the Commissioner relies on to fulfil his functions, and the organisational culture of his office. Through this assessment, this chapter identifies the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to the Commissioner’s mandate, and provides recommendations to improve the effectiveness and impact of the office.

Oversight mechanisms that provide accountability for elected and appointed officials can take several different configurations. They can be set-up as standing committees within parliament, or be instituted within the functions of the Prime Minister or Speaker. A growing trend however is towards establishing oversight bodies that are independent of the executive, and accountable to parliament. These bodies may report directly to the Prime Minister or Speaker (as is the case in Canada, the Netherlands and New South Wales, Australia) or may report to a parliamentary standards committee (as is the case in the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), Scotland and Malta).

To ensure independence, good practice suggests designing the oversight mechanisms within the following parameters:

establishing the function of the oversight mechanism in the constitution or legislation

appointing the head of the office by the legislative body for a fixed term with limited opportunities for renewal

ensuring that the appointment procedure facilitates multi-party support and that the head of the office is politically neutral and commands respect from all parties

protecting the head of the office from removal except for proven misbehaviour or other reasonable grounds in legislation (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2021[4]).

The legal and institutional set-up of the Commissioner and his office fits well within these parameters. The Act on Standards in Public Life creates the Commissioner, and grants him full autonomy and independence from the Executive, with accountability only to Parliament. The Commissioner does not report through a Minister, but rather directly to Parliament. This independence is further achieved through the appointment procedure for the Commissioner, in which the role is filled via appointment by the President of Malta acting in accordance with a resolution of the House of Representatives (decided by the votes of not less than two-thirds of all the members of the House).

The Commissioner is also protected in law from unfair removal. Article 7 outlines the provisions for the Commissioner’s removal from office, noting that “a Commissioner may at any time be removed or suspended from his office… on the grounds of proved inability to perform the functions of his office (whether arising from infirmity of body or mind or any other cause) or proved misbehaviour”. The process for removal requires the House of Representatives to agree via a two-thirds majority vote.

Moreover, the Commissioner has complete independence in terms of staffing. This independence is guaranteed in the Standards in Public Life Act (Article 11(1)), whereby the Commissioner can recruit officers and employees as necessary for carrying out the functions, powers and duties under the Act. This power includes the ability to define the number of persons that may be appointed, their salaries and conditions of appointment. Additionally, it empowers the Commissioner to engage an external consultant with relevant expertise to support an investigation (Article 11(2)).

However, several factors in the legislative framework may impact the Commissioner’s independence. First, while the Commissioner can only be dismissed due to certain conditions and following a two-thirds majority vote, the Act on Standards in Public Life is enacted by a simple majority vote. As such, particularly in light of the majoritarian parliamentary system, the Act can be repealed or amended by the government at any time, leaving the Commissioner’s position vulnerable to being dismantled. To close this loophole, the functions and role of the Commissioner for Standards could be enshrined in the Constitution of Malta. This would follow the same precedent as the Parliamentary Ombudsman and the Auditor General.2

Second, the Standards Act fails to grant legal personality to the office of the Commissioner. This further threatens the independence of the Commissioner, as without its own legal personality, the office of the Commissioner is technically part of government, thus arguably it is subject to article 110(1) of the Constitution of Malta on the appointment, removal and disciplinary control over public officers. To that end, the Ministry for Justice could consider assigning a legal personality to the office of the Commissioner in the Standards Act.3

Third, the term limits of the Commissioner are currently set for a five year, non-renewable term. This limited period raises challenges concerning the Commissioner’s ability to fully advance the mandate, as well as ensure an appropriate replacement in a timely manner. The current model in Malta is based on the UK system, where the Parliamentary Standards Commissioner is appointed for a non-renewable, five-year term. Other jurisdictions however enjoy a longer period of time (six or seven years), with the possibility of a one-time term renewal (e.g. Canada, France,4 the Netherlands, etc.). Within Malta, there is also precedent for allowing a one-time term renewal: both the Auditor General and the Ombudsmen are eligible for reappointment for one additional consecutive term of five years. To allow a Commissioner to fully realise their mandate and to bring the terms of appointment in line with other parliamentary oversight bodies in Malta, the Ministry for Justice could amend the Standards Act to allow for a five-year term with the possibility of reappointment for one consecutive term of five years. Reappointment should only be approved by the votes of not less than two-thirds of the House of Representatives.5

Fourth, unlike similar models elsewhere, there are limited specifications regarding the preferred background of a Commissioner. While Articles 5(1) and 5(2) of the Standards Act specify the disqualifications and incompatibilities to be appointed Commissioner, the Act does not contain further measures detailing the qualifications or background of the Commissioner. Additionally, although the current incumbent is a well-respected lawyer with decades of public service to Malta who has retained the respect of both political parties, he has been subject to criticism for his own political past. In this sense, the lack of specifications on the qualifications or background of the incumbent may become a challenge to ensure that future Commissioners will have the level of experience, expertise and/or strength needed to maintain the independence and high quality of the Office. In light of these challenges, the Ministry for Justice could consider defining in the Standards Act clearer parameters on qualifications and background to guide the appointment of future Commissioners.6

Finally, a fourth challenge emerging from the legislative framework concerning the independence of the Commissioner relates to the appointment of a temporary Commissioner. This is dealt with extensively in Chapter 2.

In addition to having independence clarified in the appropriate legislative framework, parliamentary oversight bodies need clear roles and responsibilities assigned to them. Although parliamentary oversight bodies may have a wide range of responsibilities, the common function across all these bodies is the ability to receive and/or investigate complaints of misconduct or breaches of ethics. Depending on the set-up, the oversight body may have additional roles and responsibilities, such as:

Providing confidential advice and guidance to elected and appointed officials on ethical dilemmas and on upholding integrity standards (as is the case in Canada, France and the United Kingdom).

Overseeing register(s) of interests, including asset and interest declarations (as is the case in Canada, France and the United Kingdom), or lobbying disclosures (as is the case in Ireland).

Providing advice to the executive on what additional integrity standards or measures may be necessary to address gaps in the integrity system for elected officials and those appointed to support them.

In Malta, Article 13 details the functions of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life as follows:

To give recommendations to persons seeking advice/clearance on whether an action or conduct intended by him would be prohibited by the Code of Ethics or by any other particular statutory duty (e.g. “negative clearance”).

To investigate the conduct of persons subject to the Act (e.g. Members of the House of Representatives, including Ministers, Parliamentary Secretaries and Parliamentary Assistants, as well as persons of trust and any other officials as determined by the Ministry of Justice by a special decision).

To monitor parliamentary absenteeism and to make sure that members of Parliament pay the administrative penalties to which they become liable if they miss parliamentary sittings without authorisation from the Speaker.

To examine the declarations of assets and financial interests filed by persons who are subject to the Act.

To monitor the evolution of lobbying activities and to issue guidelines for the management of risks connected to such activities.

To make recommendations concerning the improvement of the Code of Ethics of Members of the House of Representatives and of the Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, on the acceptance of gifts, the misuse of public resources, the misuse of confidential information, and on post-public employment (e.g. the revolving door) (Office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life Valletta, Malta, 2020[5]; Government of Malta, 2018[6]).

The following section reviews the first three functions (negative clearance, complaints handling, and monitoring parliamentary absenteeism), and the measures established to carry out these functions. Where gaps are identified, recommendations are made to strengthen the Commissioner’s capacities to handle these functions. The functions related to asset and interest declarations, lobbying and Codes of Ethics are mentioned, however detailed analysis and recommendations related to strengthening the Commissioner’s role in these areas are included in the respective chapters that review each of these functions in detail.

1.3.1. Negative clearance

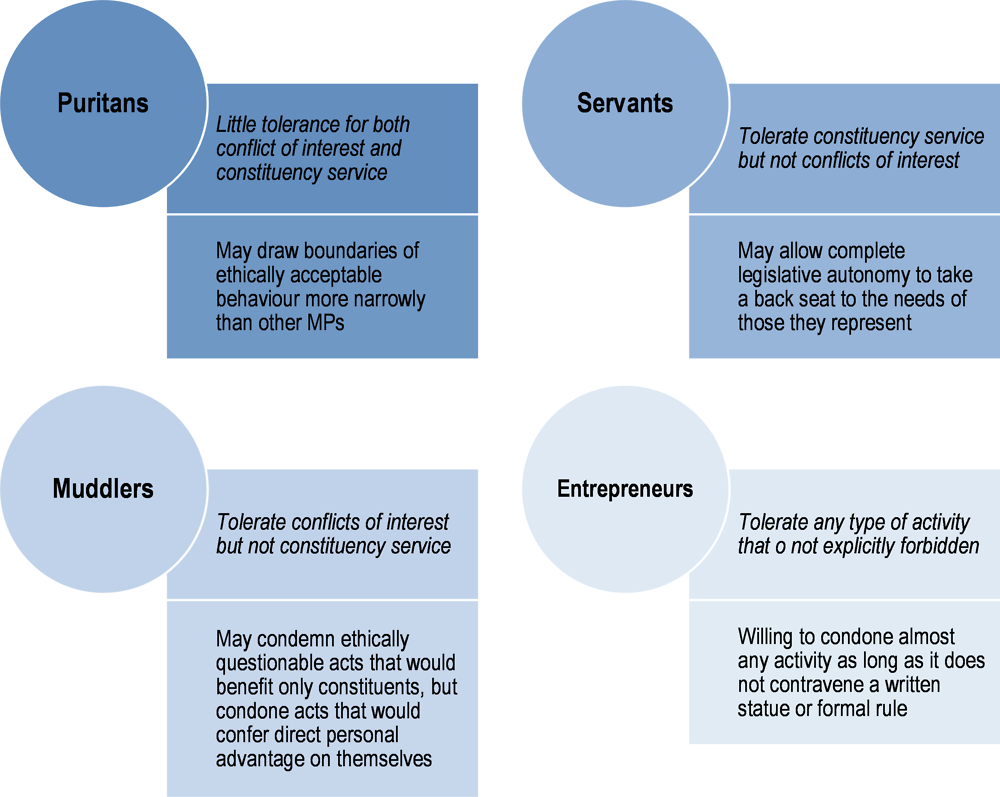

Integrity and ethics, particularly political integrity, is not always a clear-cut question of common sense. Often politicians face competing values, with different views on what these values look like in practice, leading to a lack of consensus on what constitutes political integrity. For example, in a study that looked at the political culture in the UK in the 1990s, Mancuso (1993[7]) noted four distinct ethical types: puritans, servants, muddlers and entrepreneurs (see Figure 1.1).

While these are not necessarily exhaustive types, they point to the fact that there is not always homogenous consensus on values, or how they should be applied, across political actors. To that end, having mechanisms in place that can provide integrity advice and guidance are essential for helping to raise knowledge about integrity standards and build capacity and skills for implementing the standards. Such guidance and advice can be considered in two different forms: (1) through awareness raising, trainings and workshops on the integrity standards; and (2) through written or verbal confidential advice.

The Commissioner could strengthen his role on providing general recommendations and proactive integrity guidance by developing and implementing workshops and training for officials covered under the Standards Act

Discussions with key stakeholders from parliament, government, business and civil society all underscored a lack of consensus on the core integrity values and standards in Malta. While stakeholders agreed the Commissioner’s efforts were instrumental in setting higher standards, they signalled that significant efforts were still required to build consensus around the core values for the political class. Particular challenge areas raised included the line between conflict of interest and constituency service, as well as a values-based and rules-based approach. These discussions highlighted the need to continue raising integrity awareness among persons covered by the Standards Act and further strengthen the advisory function within the integrity system.

Under the current framework, the Commissioner is responsible for addressing negative clearance requests for people covered by the Standards Act. In other words, if a person subject to the Act requests it, the Commissioner is empowered to give recommendations on whether an action or conduct intended by the requester would be prohibited by the applicable Code of Ethics or by any other statutory or ethical duty. This function of “negative clearance” is working well.

Regarding the Commissioner’s role to provide proactive general recommendations and integrity guidance, although this is not a new function, it could be further developed to achieve a greater impact. Raising awareness about integrity standards and building knowledge and skills to manage integrity issues appropriately are essential public integrity elements (OECD, 2020[8]). Raising awareness helps public officials recognise integrity issues when they arise, and well-designed training and guidance help equip public officials with the appropriate knowledge and skills to apply integrity standards. Additionally, integrity awareness raising and training can help trigger a change of behaviour by reminding people of the values and standards that should guide them when carrying out their duties.

The Commissioner has been proactive in using the findings of investigations to issue guidance on key risks that emerged. For example, the Commissioner issued recommendations to address potential conflicts of interest resulting from dual employment of Members of Parliament taking up positions in the public sector. He has also issued guidance related to the use of social media. However, to date, aside from awareness raising about the existence of the office of the Commissioner, there have been no trainings or workshops held by the Commissioner for those who are covered under the Standards Act. This, taken together with the lack of consensus around the core values for the political class, suggest that more proactive efforts could be undertaken to provide guidance and support to those covered by the Standards Act.

Aside from awareness raising and capacity building on integrity more generally, providing principles, rules, standards and procedures that give public officials clear directions on how they are expected to behave when engaging with third parties can help foster a culture of integrity (OECD, 2021[9]). In Malta, this remains an area that could be further strengthened, as discussed in Chapter 5.

To that end, the Commissioner could develop and implement a series of workshops for officials covered under the Standards Act, which focus on the core values and standards of conduct outlined in the respective Codes of Ethics and the new proposed regulation on Lobbying. In particular, considering the recent election, the Commissioner could prepare a workshop for the new parliamentary session. Informed by lessons learned in other jurisdictions, this workshop could take place a month or two after MPs take up their roles, allowing these MPs to settle and process information (McCaffrey, 2020[10]). These workshops could include ‘ethical dilemma’ training, whereby participants are presented with an ethical dilemma, and discuss in small groups what actions they would take to resolve those dilemmas. This practice borrows from the lessons learned in the civil service, where other jurisdictions have used dilemma training to support delivery of integrity training to public officials (see Box 1.1).

Dilemma training in the Flemish Government, Belgium

The Agency for Government Employees in the Flemish Government offers dilemma training to public officials. During the training, participants are given practical situations in which they face an ethical dilemma with no clear path to resolving the situation with integrity. The facilitator encourages discussion between the participants about how to resolve the situation and helps them explore the different choices. The focus of the training is the debate rather than possible solutions, as the objective is to help participants identify how different values might act in opposition to one other.

One example of a dilemma situation is:

Frans F. is a supplier with whom you have been working for a long time. Negotiations are currently underway to continue the cooperation with this supplier. You meet Frans F. during a study day and he proposes to have lunch together at noon. He takes you to a fancy restaurant and says “Don't worry, the bill is mine”. What do you do?

1. We have known each other for a long time. I will enjoy the lunch.

3. I make him pay, but make it clear that this makes me uncomfortable, and that it will not be repeated.

4. I order the cheapest dish on the menu and report the situation.

Dilemma situations could cover themes such as conflicts of interest, ethics, loyalty, leadership and so on. The training sessions and situations used can be targeted to specific groups or entities.

Source: (OECD, 2018[11]) and https://overheid.vlaanderen.be/personeel/integriteit/omgaan-met-integriteitsdilemmas (unofficial English translation, original in Dutch).

1.3.2. Complaints handling

When ethical standards are alleged to have been breached, parliamentary oversight bodies play an essential, investigative role to determine whether misconduct took place. Under the Act on Standards in Public Life, the Commissioner is responsible for handling complaints and allegations of breaches of any statutory or any other ethical duty of any person to whom the Act applies. The Commissioner can also launch an own-initiative investigation to investigate possible breaches even if no official complaint has been made. Handling complaints and carrying out investigations is an essential part of the Commissioner’s remit.

Determining the effectiveness of the complaint and investigatory process requires looking at it from two different perspectives: (1) the perspective of the complainant; and (2) the perspective of the person the complaint was submitted against. The following deals with these two perspectives, and how they are realised in practice by the procedures in place by the Commissioner.7

With regards to the perspective of the complainant, the complaints function should be visible, accessible, timely and effective. “Visible” requires complainants knowing that a mechanism exists for them to raise their concerns with. In practice this means that the parliamentary oversight body should raise awareness about who can submit a complaint and on what issues, and what they can expected from the process. To be “accessible”, complainants should not face significant obstacles when trying to submit their complaint. In practice, this means that the parliamentary oversight body should have clear procedures for submitting complaints, whether by post, telephone, email or online; guidance in plain language should be provided; and complainants should feel safe accessing the mechanism. “Timely” means that the parliamentary oversight body should react quickly to confirm receipt of the complaint, and process the complaint in a timely manner. Finally, “effective” means that once an investigation is complete, the parliamentary oversight body’s findings should be received by a competent body that has the ability to take a clear course of action on the findings.

To strengthen accessibility for complainants, the Commissioner could enhance guidance on how to submit a complaint, enable anonymous complaints, and have the power to grant whistle-bower status

With regards to visibility, the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life has a clear website that is easy to access.8 The Commissioner has also participated in a number of public events to raise awareness about the existence of his office and the complaints mechanism. For example, the Commissioner has carried out presentations to students at the University of Malta on issues related to standards in public life and lobbying, conducted several interviews with the media on his functions and the Standards Act, appearing on One, Net, TVM, Malta Today, 103 – Malta’s Heart, and Lovin Malta.

With regards to accessibility, there are clear procedures in place for submitting complaints, including by post, email and through the Commissioner’s website. Complaints can also be received orally and put in writing no later than ten days (although this procedure has yet to be used). A dedicated webpage about “complaints” details how to make a complaint, and covers information about who complaints can concern, what actions can be complained about, the timeframe, and what happens if other proceedings are ongoing. The website also clarifies the reasons why the Commissioner may reject the complaint.

The Commissioner also provides support to complainants, including following up with them once a complaint is received to ensure sufficient information has been provided. Previous complainants noted that the process to submit a complaint to the Commissioner is straightforward, and several appreciated the support of the Commissioner and his office in helping to guide complainants through the process. Others however noted that more could be done to clarify the complaints procedure. To that end, the Commissioner could consider including on his website a section that details what the Commissioner cannot investigate, and who the appropriate authority for undertaking that investigation may be. In other jurisdictions, detailed information on the complaints process, including what can and cannot be investigated, is included on their website (see Box 1.2). Moreover, it is worth noting that the website does not clarify who can submit a complaint, and for those who may not be well versed on the Commissioner’s role or the Standards Act, it may not be immediately clear. To that end, the Commissioner could consider clarifying on the website that the complaints mechanism is open for everyone.

Canada

The webpage of the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner of Canada contains a section on investigations, with two separate subsections that clearly differentiate what the Commissioner can and cannot investigate. Additionally, it contains a subsection on what to expect during an investigation, which aims to provide participants in an investigation with a clear idea of what happens in the course of an investigation carried out by the Commissioner, and the main differences between investigations under the Conflict of Interests Act and those under the Conflict of Interests Code.

The Netherlands

The webpage of the Integrity Investigation Board of the Netherlands contains a section with information on how to submit a complaint, including information regarding what the Integrity Investigation Board cannot investigate and a simple form that complainants can fill in order to make an online complaint. The form contains a link to further information on the use of personal data by the Integrity Investigation Board and why personal information is required to process any compliant.

United Kingdom

The webpage of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards of the United Kingdom contains clear information on what the Commissioner can and cannot investigate. Additionally, a section with frequently asked questions may also help to guide complainants through the process to submit a complaint, including the answers to the following questions:

What information do I need to provide when making an allegation?

Can I make a complaint about the Commissioner’s decision not to investigate a matter?

How can I complain about the standard of service an MP has or has not provided?

Can I complain about something an MP has posted on a social media platform?

How do I complain about something an MP has said in the House of Commons Chamber?

How do I complain about something an MP has done in their Ministerial role?

Sources: Official websites of the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner of Canada, https://ciec-ccie.parl.gc.ca/en/investigations-enquetes/Pages/default.aspx; the Integrity Investigation Board of the Netherlands, https://www.tweedekamer.nl/klacht-indienen-bij-het-college-van-onderzoek-integriteit and the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards of the United Kingdom, https://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-financial-interests/parliamentary-commissioner-for-standards/parliamentary-commissioner-for-standards/.

Beyond clear procedures for submitting complaints, a second attribute of accessibility relates to how safe potential complainants feel accessing the mechanism. Currently the Act on Standards in Public Life does not allow for anonymous complaints. Five anonymous complaints have been received thus far, but the Commissioner was unable to receive them. To facilitate access for those who wish to keep their identity confidential, the Commissioner allows for complainants to indicate in their submission that they wish for their identity to be kept confidential. It is not clear the extent to which the Commissioner can protect the identity of these individuals, which may impede those with a legitimate complaint from coming forward. To that end, enabling individuals to submit a complaint anonymously can help encourage reporting on wrongdoing and strengthen trust in the reporting system. As discussed in Chapter 2, the Standards in Public Life Act could be amended to allow for anonymous complaints. To facilitate anonymous reporting, the Commissioner could set up a portal allowing anonymous complainants to submit their information using a pseudonym and employ encryption technology for follow-up to ensure that the complainant remains anonymous. The example of the corruption hotline using double-encryption technology in Austria may serve as an example (see Box 1.3).

In 2013, the Federal Ministry of Justice in Austria launched a portal to enable individuals to report wrongdoing. The portal can also be accessed via a link on the Federal Ministry of Justice homepage, where individuals can find and download further information on the portal. The portal is operated by the Central Public Prosecutor’s Office for Combating Economic Crimes and Corruption (CPPOCECC).

The whistleblowing system is an online anonymous reporting system, which is especially suited for investigations in the area of economic crimes and corruption. The whistle-blower (or “discloser”) may report anonymously any suspicion that a crime in the general remit of the CPPOCECC pursuant to section 20a of the Code for Criminal Procedure (CCP) was committed; the investigation authority in turn may make inquiries with the whistle-blower, while maintaining his or her anonymity in order to verify the value of the information. Any reports within the focus set forth by section 20a CCP, but outside the CPPOCECC remit, are forwarded to the competent authority (mostly financial authorities).

To ensure that anonymity is guaranteed, when setting up a secured mailbox, the whistle-blower is required to choose a pseudonym/user name and password. The anonymity of the information disclosed is maintained using encryption and other security procedures. Furthermore, whistle-blowers are asked not to enter any data that gives any clues as to their identity and to refrain from submitting a report through the use of a device that was provided by their employer. Following submission, the CPPOCECC provides the whistle-blower with feedback and the status of the disclosure through a secure mailbox. If there are issues that need to be clarified regarding the case, the questions are directed to the whistle-blower through an anonymous dialogue. Such verified reports can lead to the opening of investigations or raise concrete suspicions requiring the initiation of preliminary investigations.

As of 31 May 2017, the introductory page of the electronic whistleblowing system was accessed 343 0296 times. A total of 5 612 (possible) criminal offences were reported, less than 6% of which were found to be completely without justification. A total of 3 895 of the reports included the installation of a secured mailbox. About 32% of the reports fell into the scope of other (especially financial) authorities and were forwarded accordingly.

Sources: Austrian Federal Ministry of Justice, www.bkmssystem.net/wksta; and https://www.bkms-system.net/bkwebanon/report/clientInfo?cin=1at21&c=-1&language=eng.

Allowing anonymity however may not be sufficient in all cases. Public employees in particular who raise a complaint against their colleagues or superiors may need additional assurance that there will not be reprisals and work-related sanctions for reporting wronging and misconduct of superior officers or fellow colleagues covered by the Standards Act. Indeed, providing for and clearly communicating about the protections afforded to whistle-blowers supports an open organisational culture and encourages the disclosure of wrongdoing, as public employees are aware of how to report misconduct and have confidence in reporting due to the clear protection mechanisms and procedures in place (OECD, 2016[12]). To that end, as recommended in Chapter 2, the Commissioner could be enabled to grant whistle-blower status to public employees.

If granted this authority, the Commissioner could ensure that public employees are aware of the possibility to be granted whistle-blower status, and what whistle-blower status is (and is not). To that end, the Commissioner could consider carrying out communication campaigns on the new mechanisms in place and raising awareness amongst public employees about reporting channels, protection mechanisms and procedures to facilitate the submission of complaints, through newsletters and/or information sessions. Examples from other jurisdictions can be used to design communication and awareness raising campaigns on whistle-blowing protection in Malta. For instance, the Slovak Republic integrated whistle-blower protection into their ethics training, forging a strong link between protecting the public interest and integrity, and the United States requires that agencies provide annual notices and biannual training to federal employees regarding their rights under employment discrimination and whistle-blower laws (OECD, 2016[12]).

The Commissioner could ensure that cases are handled in a timely manner

Complaint mechanisms need to deal with complaints in a timely, efficient manner and good practice suggests clarifying in law or related guidance expected service standards for dealing with a complaint.

Once the Commissioner has received a complaint, his office conducts a preliminary review to determine whether the complaint is eligible for investigation in terms of the Standards Act. If the complaint is not eligible, the Commissioner informs the complainant and the case is closed. Complainants noted that while they appreciate the length of time it takes to investigate a complaint, the Commissioner can take a long time in the ‘initial assessment’ phase, i.e. determining whether to accept the complaint or not. To strengthen timeliness in this regard, the Commissioner could set a service standard of a specific time period within which to determine whether the complaint will be accepted or not. The Commissioner could also ensure sufficient human resources are available to meet this service standard (see Section 1.4).

If a complaint is found eligible, the Commissioner opens an investigation. This includes collecting, filing and recording evidence, summoning witnesses, preparing and revising the draft reports. Interviews with the Commissioner and his office found that the process to investigate complaints has improved with practice, although carrying out an investigation can be incredibly lengthy and time consuming, given the complexity of the cases received. For example, the office staff transcribes the verbal evidence, which has become one of the main challenges in terms of workload. Although there is a possibility to outsource the transcription of evidence, the Commissioner has been reluctant to do so because of the sensitivity of the information collected in the course of an investigation. Additionally, the Commissioner and his office have noted that witnesses have been co-operating so far, although there have been some delays in certain cases where people were summoned but could not attend because of COVID-19.

Concerted efforts are ongoing to make the process more efficient by formalising procedures, based on lessons learned from previous cases -e.g. summarising witnesses’ interviews rather than transcribing them. Yet given the lack of resources, when the Commissioner receives a complex case, the rest of the work is put on the backburner. As will be further explored in Section 1.4, the Commissioner could consider bringing in more dedicated resources to manage the various elements of complaints handling.

To ensure effectiveness of the Commissioner’s findings, the Committee for Standards in Public Life could be restructured

Implementing clear investigative procedures and timely responses to reports of misconduct strengthen the credibility of the integrity system. Timely investigations can act as a deterrent for those covered by the Standards Act to comply with their ethical duties and to not engage in misconduct because of the risk for detection, sanctioning and shaming. The Commissioner’s response and investigation of complaints are a first step towards enhancing the integrity of elected and appointed public officials, but ensuring his reports are discussed and wrongdoings, when ascertained, are sanctioned, are essential for reinforcing integrity standards in the long term. Indeed, making sure that findings do not just sit on the shelf but instead trigger sanctions can help strengthen the credibility of the system and signal to the public the government’s real commitment to political integrity.

In Malta, following the course of his investigation, the Commission can issue a report containing his conclusions and recommendations to the Committee for Standards in Public Life (herein the “Committee for Standards”). The Committee for Standards must decide whether to adopt the conclusions and recommendations contained in the report, and take an action by application of Articles 27 and 28 of the Standards Act, including the imposition of an appropriate sanction if it finds that there has been misconduct.

To date, the Commissioner has submitted six cases to the Committee for Standards. Although the Committee for Standards has not rejected a case report submitted by the Commissioner, as a whole, it has failed to implement sanctions effectively, mainly because of its current composition and lack of incentives for its members to work above political party lines.9 Indeed, discussions with key stakeholders, including members of the Committee for Standards, the office of the Ombudsman, academics and representatives from civil society underscored the weaknesses of the composition of the Committee for Standards and highlighted that such Committee is currently the weakest element of the integrity framework for elected and appointed officials in Malta. Additionally, members of the Committee for Standards have been criticised for acting in a politicised way, including the Speaker of the House who has issued rulings that have prevented the Committee for Standards from imposing sanctions where there was evidence of misconduct by government MPs.

While Chapter 2 deals with this issue in more detail, it is important to note here that the Committee’s difficulties in reaching consensus on proportionate sanctions in cases of proven misconduct damages the integrity system as a whole. To that end, as noted in Chapter 2, the Ministry for Justice could consider changing the structure of the Committee for Standards to enhance its independence and functioning. Reforms could include the following specific actions:

Including lay members on the Committee for Standards to bring an independent and external perspective to the deliberations of the Committee, and elaborating clear guidelines for their appointment.

Appointing as the chairperson of the Committee for Standards a former judge selected by all political parties and known for his/her integrity and independence, to raise the nature of the discussions beyond specific individuals or political parties and ensure a timely response to reports of misconduct.

Elaborating clear guidelines for the appointment process of MPs as members of the Committee for Standards, including ensuring that MPs appointed as members of the Committee are not sitting members of the Cabinet.

Developing guidelines for members of the Committee for Standards on their role and responsibilities, values and expected standards of behaviour, along with other integrity measures.

To ensure transparency, the mechanisms detailed in the Standards Act on fair process could be further elaborated on in the form of rules of procedure.

Beyond ensuring that the complaints function is visible and accessible, complaints are handled in a timely manner, and results are effective, parliamentary oversight bodies also need to ensure they handle complaints in line with the principles of fair process. These principles include:

taking measures to address any actual or perceived conflict of interest;

keeping the complaint confidential as far as possible, with information only disclosed if necessary to properly review the matter;

upholding the right of the individual to be advised of a complaint lodged against them and to present their position, as well as comment on any adverse findings before a final decision is made (Office of the Ombudsman, 2012[13]).

In Malta, there are clear mechanisms in place for protecting the principles of fair process. These mechanisms are outlined in the Standards Act: Article 18(3) states that before the Commissioner makes any finding or recommendations about a person investigated, such person should have access to all evidence and should have the right to be heard in accordance with the principles of fair trial. Moreover, Article 21(1) of the Standards Act mandates the secrecy of the information obtained by the Commissioner in the course of an investigation under the Act, except for the purposes of the investigation and for the publication of the case reports.

The legal basis concerning transparency and accountability in the process could be strengthened, and is further explored in Chapter 2. In addition to the legal basis, the Commissioner and the Committee for Standards have agreed on a series of internal procedures aimed at guaranteeing the principles of fair process in order to safeguard the right to privacy of the individual under investigation.

Going forward, the Commissioner could detail rules of procedure for his office on case handling, from receipt to issuing of the final report to the Committee. These rules of procedure should build on Articles 18(3) and Article 21(1), as well as the internal procedures agreed between the Commissioner and the Committee for Standards. In line with proposed good practice elsewhere, the Commissioner could consider allowing the House of Representatives to review and approve the rules of procedure, in order to obtain their buy-in and support.10 The Commissioner could also consider sharing these rules with those subject to an investigation.

1.3.3. Monitor parliamentary absenteeism and oversee payment of fines

In addition to the function of receiving and investigating complaints of misconduct or breaches of ethics, parliamentary oversight bodies may have other roles and responsibilities. In Malta, Article 13(1d&e) of the Standards Act requires the Commissioner to scrutinise the register with all the details of absentee Members of Parliament and to ensure that those who have been absent without permission pay the monthly administrative fine.

However, the Commissioner has noted that this function could be carried out by the Clerk of the House of Representatives, as such role takes up an important amount of time which could be devoted elsewhere to achieve a greater impact in raising integrity standards amongst people in public life. In this sense, in line with international good practices, the Ministry of Justice could consider removing this function from the Standards Act and entrusting it to the Clerk of the House and the political parties (see also Chapter 2 for more details on this recommendation).

1.3.4. Asset and interest declarations

Under the Standards Act, the Commissioner is responsible for examining and verifying the declarations of assets and financial interests filed by persons subject to the Act. Early in his term, the Commissioner developed a methodology for the review and verification of these declarations (see Box 1.4).

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life has defined an internal procedure for carrying out the review of the annual declarations made by MPs. Such procedure relies on the submission of the following information per MP:

The annual declaration, which is submitted by each MP to the Speaker of the House by 30 April of the following year.

Ministers/parliamentary secretaries returns to the Speaker of the House, which are to be submitted by 31 March of the following year.

Extracts of the income tax return completed by each MP drawn up by the Commission for Revenue and passed on to the Speaker of the House.

The process consists of the following six steps:

1. The office of the Commissioner maintains an excel sheet for each MP, where data is inputted from each of the aforementioned sources (source of information is clearly indicated). To assess the information available on each MP, data for each year is inputted in different columns allowing to compare how the amounts and assets would have changed from one year to another.

2. A senior official within the office of the Commissioner reviews the information populated and lists any queries or clarifications that are necessary.

3. In cases where an MP has carried out a property transaction during the year, a copy of the public deed is requested. This, in order to understand the financing of property acquisitions as well as the possible movements in bank balances/investments and the possible sources of financing of future property acquisitions. In cases where the movement of assets and/or liabilities do not make sense with i) the income illustrated on the return completed by ministers/parliamentary secretaries; ii) with the extracts of income derived from the Commission for Revenue in the case of MPs; and/or iii) with other facts known by the office of the Commissioner, specific clarifications are requested. The respective MP is given 14 days to reply. All communication is done in writing and a separate file is opened to maintain all correspondence.

4. A senior official within the office of the Commissioner reviews the documentation received. If deemed necessary, further information or clarification is requested.

5. Depending on the outcome of the analysis, the MP may need to re-submit the annual declaration. Depending on the error or omission, further action may be taken or the file could be concluded satisfactory.

6. In all cases, a concluding memo is included in the respective file.

Source: Questionnaire on the office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2021.

There are a number of challenges related to this role, most notably due to gaps in the Standards Act and the Income Tax Management Act. These issues are addressed in detail in Chapter 4, it is however worth noting here that any increased responsibility for the Commissioner to handle interest and asset declarations will require considerations related to human resources.

1.3.5. Monitor the evolution of lobbying activities and issue guidelines to manage lobbying-related risks

The Commissioner is also responsible for identifying the activities in Malta that should be considered as “lobbying”, issuing guidelines for those activities, and making recommendations to regulate such activities (Article 13(1f) of the Standards Act).

To date, the Commissioner has prepared a Consultation Paper that sets out the proposals to regulate lobbying, including defining who is a lobbyist, what constitutes lobbying, and how such lobbying activities should be regulated. A full analysis of these proposals is dealt with in Chapter 5, but it is worth noting here that the proposals by the Commissioner include assigning his office the responsibility for managing a Register of Lobbyists and a Transparency Register. This will require significant financial and human resources in order to implement the function.

1.3.6. Issue recommendations to improve the Code of Ethics and raise integrity standards

The final function allocated to the Commissioner is laid out in Article 13(g) of the Standards Act, and includes issuing recommendations for improving the Code of Ethics for those covered by the Act, as well as recommendations regarding the acceptance of gifts, misuse of public resources, misuse of confidential information, and post-public employment measures.

In July 2020, the Commissioner issued a document proposing the adoption of revised codes of ethics for MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries and additional guidelines. The content of these revised codes and additional guidelines is assessed in Chapter 3, but it is worth noting that the revised codes and additional guidelines recommend several registries that will be managed by the office of the Commissioner, including:

The proposals also foresee a three-year “cooling-off period” for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, and a one-year “cooling-off period” for MPs.

As noted previously, the proposed additional registries will need to be effectively managed in order to achieve their intended aim. It is paramount that the Commissioner has the appropriate staffing and financial resources in place to carry out these functions.

For parliamentary oversight bodies, a critical factor for ensuring independence rests in the ability to raise the human and financial resources necessary to carry out duties. This includes hiring independently of the broader public service recruitment system and having stability in the assigned financial resources.

In addition, given the role of raising integrity standards in Malta, it is imperative that the Commissioner and his office operate in a way that is above reproach. This involves strengthening existing integrity measures, as well as implementing new ones, to guide ethical behaviour.

1.4.1. Ensuring the office of the Commissioner has sufficient financial and human resources

Independence in human and financial resources ensures that the staff working within the parliamentary oversight body are not dependent upon the executive for employment. Similarly, the stable financial resources protect oversight bodies from political pressure, thereby strengthening independence. Indeed, the resources allocated to an oversight body must be commensurate with their mandate in order for them to fulfil it in a credible manner, and should be published and stable across years, while allowing some flexibility in periods where there is a higher demand for the oversight body’s services –e.g. when an unusually high number of investigations are required. To ensure the Commissioner and his office are fit-for-the-future, the following sets out recommendations to improve the financial and human resource capacity of the office.

Malta should ensure that the Commissioner has the appropriate financial resources to implement the strengthened roles and responsibilities regarding lobbying and asset and interest declarations

In Malta, the Commissioner has a certain degree of independence in terms of his office’s budget. Article 11(5) of the Standards Act states that the Commissioner should present to the House of Representatives, by 15 September of each year, a financial plan indicating the ensuing year’s activities of his office. There are no specific guidelines to follow and the Commissioner has complete discretion to draw up the budget estimates for the running of his office. As any other entity, the allocated budget of the Commissioner depends on an approval by the House of Representatives (specifically by the House Business Committee), who considers the estimates of the office’s financial plan. So far, the House of Representatives has always approved the annual estimates presented by the Commissioner and has always guaranteed the Commissioner the budget requested in the financial plan.

Such practice is in line with good practices adopted in other jurisdictions. For instance, in Canada, before each fiscal year, the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner prepares an estimate of its budgetary requirements for the coming fiscal year. The estimate is considered by the Speaker of the House of Commons and then transmitted to the President of the Treasury Board, who lays it before the House with the estimates of the Government of Canada for the fiscal year (Government of Canada, 1985[14]).

With the new mandates and functions on lobbying, assets and interests declarations and handling of additional registers, it is paramount that the Commissioner has the appropriate financial resources to carry out his new functions effectively. To that end, the Commissioner could consider carrying out a socialisation process with the House Business Committee of the House of Representatives in order to explain the need to increase the budget size of his office permanently to consistently deliver on the new functions. The budget size should increase accordingly.

The Commissioner could undertake a workforce planning exercise to identify the skills and competencies needed within his office to carry out its functions

In Malta, the Commissioner has complete independence in terms of staffing. This independence is guaranteed in Article 11(1) of the Standards in Public Life Act, whereby the Commissioner can recruit officers and employees as necessary for carrying out the functions, powers and duties under the Act. This independence includes defining the number of persons that may be appointed, their salaries and conditions of appointment. Additionally, the Act empowers the Commissioner to engage in the conduct of an investigation, in a consultative capacity, any person whose particular expertise is essential to the effectiveness of the investigation (Article 11(2) of the Standards Act).

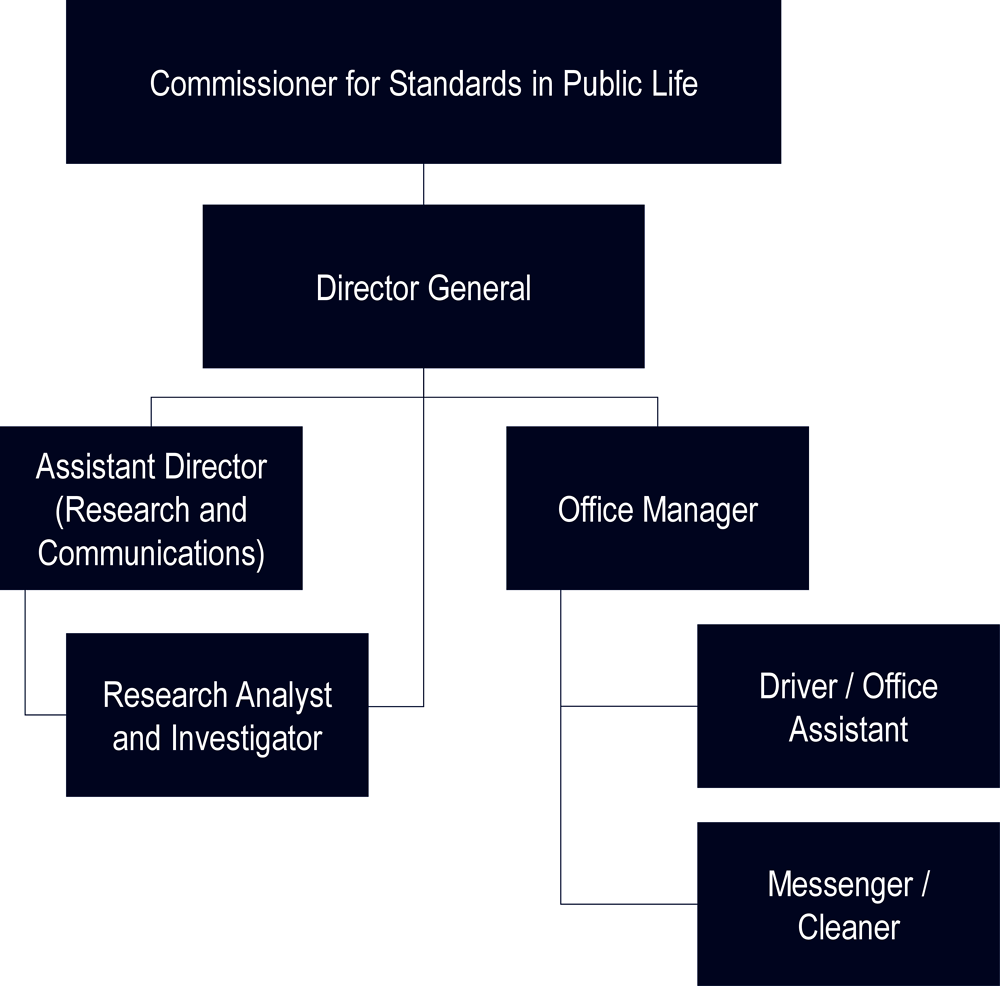

Currently, the office of the Commissioner consists of seven staff members including the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, a Director General, an Assistant Director, a Research Analyst and Investigator, an Office Manager/Personal Assistant, a driver and a messenger/cleaner (see Figure 1.2). The employees who joined the office immediately after the appointment of the Commissioner (this is, the Office Manager/Personal Assistant, the driver and the messenger/cleaner) joined the office without public calls. The Director General and the Assistant Director were detailed from the public service following the approval of the Principal Permanent Secretary and the Prime Minister. The most recent recruit – the Research Analyst and Investigator – was employed through a public call.

In addition to the six officers and employees, the Commissioner has retained three people on a contract-for-service basis. These consultants include i) a legal advisor to give advice on legal issues arising primarily from investigations; ii) an auditor to assist in the examination/verification of the declarations of assets and interests; and iii) a media consultant to provide support and advice regarding communications with the media and the use of online platforms by the office of the Commissioner.

As previously mentioned, the office of the Commissioner is small in number. Although having a small office may be a strength in terms of management, engagement and co-ordination of the staff, it can be a challenge in terms of ensuring that functions are fulfilled in a timely and efficient manner, as has been detailed above. Moreover, as there is the potential for new functions to be added to the Commissioner’s remit, for example on lobbying, asset and conflict of interest declarations, and registries under the revised Codes of Ethics, the workload of the office is expected to increase substantially.

With a view to analysing the current workforce and increasing the human resources of the office to handle additional functions, the Commissioner could undertake a workforce planning exercise to identify what additional positions are required, the roles and work to be performed in each position, and the qualification and performance criteria that should guide objective selection processes. Key elements of workforce planning are outlined in Box 1.5.

Tracking staff numbers in itself does not constitute workforce planning, rather it is only one facet of workforce planning. Workforce planning requires an accurate understanding of the composition of the public administration’s workforce, including skills, competences and staffing numbers in the immediate, medium and longer term and how to cost-effectively utilise staff to achieve government objectives.

Generally, workforce planning models are comprised of similar elements, including:

Source: (OECD, 2015[16]).

As part of this workforce planning exercise and with the aim of developing strategies to close the gaps between the current workforce and the future workforce needed, the Commissioner could develop a medium term plan for filling the gaps in the competencies of the workforce through new recruitment and training. In such plan, the Commissioner could determine the strategies to close the gaps by developing scenarios of the size, structure and competences of the workforce needed to deliver its current and new functions, as well as conducting analysis of the cost implications of the different options. Practices from other jurisdictions can be used by the Commissioner to conduct this exercise (Box 1.6).

In the Korean government, a workforce plan is established by each central ministry and agency every five years. The process begins by organisations analysing the current workforce: its size, disposition, structure and composition, as well as recent changes, personnel management practices, and current competency level. The second step is to project what will be necessary for the next five years: workforce size, composition and competencies required to achieve mid- to long-term vision and strategies. The third step is to estimate the gap between the current level and future demand. If a significant gap is identified, likely problems are analysed and possible alternatives for closing the gap are reviewed. The final step is to develop strategies for reducing the gap so that, by the end of the five-year period, the objectives of the workforce plan – workforce size and competency levels – will have been achieved. A workforce plan includes recruitment (selection, promotion and transfer), development (education, outside training and mentoring) and disposition (career development and job posting).

Source: (OECD, 2015[16]).

1.4.2. Strengthening integrity measures

In addition to ensuring the office has the appropriate human and financial resources to prepare for the future, the Commissioner could also strengthen his office by implementing several public integrity measures. These include strengthening merit-based recruitment, adopting a Code of Ethics, and providing further guidance on managing and preventing conflicts-of-interest.

The Commissioner could strengthen merit-based recruitment processes for his own staff

While the Commissioner’s independence precludes him from following public recruitment procedures and public procurement rules, the Commissioner has strived to ensure that the right processes are applied to bring in the right people, in a fair and transparent way. Three years after establishment, the Commissioner could consider formalising these processes to ensure that merit-based recruitment remains the norm. A clear, merit-based process for recruitment and appointment will further strengthen the office’s reputation as a key integrity actor in Malta, which not only upholds integrity standards, but also applies integrity standards internally. Core principles of merit-based recruitment, and how they can be exercised in practice, are outlined in Table 1.1.

Building on these principles, the Commissioner could establish an organisational structure that details the existing positions, with clear and justifiable criteria for each position. This is the first step to develop a merit-based system. Additionally, the Commissioner could ensure that all future employment calls are done publicly. Pre-determined criteria for each position could be included in the advertisement, with measures in place to ensure objectivity in decision making (e.g. requiring a standardised curriculum vitae, carrying out standardised tests, conducting a panel interview, and using various tests depending on the position). The Commissioner could ensure that the job advertisement is published together with detailed information on the selection criteria and the selection process, providing transparency and objectivity to the recruitment procedure. The recruitment process of the staff of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards in the United Kingdom may serve as an example for the Commissioner (see Box 1.7).

In the United Kingdom, the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards recruits new members of her team through public employment calls. The Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards sets pre-determined criteria for each position, which are included in the job description together with the key responsibilities and values that the jobholder should carry out and comply with once in his/her role. The job description is published on the House of Commons careers website.

The selection process is based on the analysis of the criteria set out in the skills and experience section of the job description. Candidates that are interested in the position should send an application form, which is used to select those candidates that could move on to the next round of the selection process. Successful candidates are invited to undertake a series of written tests, including psychometric tests and case studies tests, and to attend a competency-based interview.

Source: (House of Commons, n.d.[17]); Interview with the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards of the UK Kathryn Stone on the 28 October 2021; and UK House of Commons, Careers at the House of Commons, https://housesofparliament.tal.net/vx/lang-en-GB/mobile-0/appcentre-HouseOfCommons/candidate.

Additionally, considering that the office of the Commissioner is not included in the exclusions of the Ombudsman Act (First and Second Schedule of the Ombudsman Act), nothing stops a candidate who applied to work in the office of the Commissioner of referring grievances about the selection process to the Ombudsman. In this sense, there is an independent body with investigative powers and authority to intervene in HR processes of the office of the Commissioner when breaches are deemed to have happened. However, to further clarify this procedure and ensure that candidates are aware of their rights, the Commissioner could include information on this procedure in the job advertisement of the corresponding procedure.

The Commissioner could establish an internal Code of Ethics in consultation with their staff and other key stakeholders, and publish it on the website to raise awareness about values and integrity standards applied in the office

Setting high standards of conduct that must be implemented by any public official –whether elected, appointed or recruited on merit– and that prioritise the public interest reflects the commitment to serving the general interest and building a public-service oriented culture (OECD, 2020[8]). Standards of conduct express public sector values, and these values are key for guiding the behaviour of public officials. In particular, values set out the basic principles and expectations that society deems to be of importance for public officials, and provide clarity for organisations and public officials at all levels regarding expected behaviours.

The office of the Commissioner is well-versed on the role high integrity standards play in guiding the conduct of those covered by the Standards Act. However, given the independence granted to the Commissioner and his office, employees within the office of the Commissioner fall into a ‘grey zone’. Some employees, who were detailed from the civil service, are obligated to follow the Code of Ethics for Public Employees and Board Members of the Public Administration Act. Other employees, based on the recruitment levers used, do not fall under this broader Code of Ethics.

It is worth noting that beyond broader integrity standards detailed in a Code of Ethics, some common measures do apply to employees of the office of the Commissioner. For example, under Articles 10(1) and 11(6) of the Standards Act, both the Commissioner and his staff are expected to take an oath that they will faithfully and impartially perform their duties, and that they will not divulge any information acquired by them under the Act. Moreover, the Commissioner has implemented some additional measures, including a contractual obligation for officers to obtain permission from the Commissioner before accepting other paid work either through other employment or through self-employment. Additionally, although there is no legal requirement for doing so, the Commissioner conducted self-due diligence before accepting the appointment with the intention to avoid any possibility of a potential conflict of interest.

Although these measures are a first step towards setting integrity standards for the office of the Commissioner, developing a Code of Ethics that provides internal and external clarity on the integrity measures the office is committed to upholding could further strengthen its integrity. Moreover clear standards of conduct could also strengthen public perceptions regarding the independence of the Commissioner and his office. This is particularly needed in light of public commentaries accusing the office of the Commissioner of political bias and lack of standards, which have affected public perception of its independence and capacity.

To that end, the Commissioner could consider establishing a Code of Ethics that details the core values for his office. In line with good international practice, the Commissioner could avoid overloading the Code with too many values, as this can make it difficult for staff to remember them. Indeed, as the number of items humans can store in their working memory is limited, a memorable set of values or key principals ideally has no more than seven elements (plus or minus two) (Miller, 1955[18]; OECD, 2018[11]). To that end, the Code of Ethics could be limited to no more than seven elements to support understanding and implementation. Box 1.8 highlights examples from Australia and Colombia.

The REFLECT model of the Australian Government

The Australian Government developed and implemented different strategies to enhance ethics and accountability in the Australian Public Service, including the Lobbyists Code of Conduct, the Australian Public Service Values, the Ministerial Advisers’ Code and the Code of Conduct. To help public servants address ethical dilemmas during the decision-making process, the Australian Public Service Commission also developed a decision-making model. The model follows the acronym REFLECT:

The Colombian General Integrity Code

In 2016, the Colombian Ministry of Public Administration initiated a process to define a General Integrity Code. Through a participatory exercise involving more than 25 000 public servants through different mechanisms, five core values were selected:

In addition, each public entity has the possibility of integrating up to two additional values or principles to respond to organisational, sectoral and/or regional specificities

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Australia, “APS Values”, www.apsc.gov.au/aps-values-1; Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública, Colombia, www.funcionpublica.gov.co/web/eva/codigo-integridad.

The Code could be developed in consultation with the office’s staff and published on the Commissioner’s website to raise awareness about integrity standards applied in his office. Developing the Code of Ethics with the support of the office’s staff can help the staff in understanding and applying the integrity standards in their daily activities, while allowing the participation of other key stakeholders can help raising awareness about what the public can and cannot expect from the office of the Commissioner. Other jurisdictions, such as Canada, have defined values and standards of integrity for their oversight bodies, in consultation with their employees (see Box 1.9).

The Code of Values and the Standards of Conduct for employees of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner of Canada were adopted by consultation with employees in October 2019. These documents set out the expectations for behaviour governing all activities that the employees of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner perform to fulfil the Office’s mandate.

All employees, no matter what their level, are expected to adhere to the values—respect for people, professionalism, impartiality and integrity—set out in the Office’s Code of Values. Employees who do not comply with the Code of Values and who knew or reasonably should have known that they were not in compliance may be subject to appropriate disciplinary measures that include reprimand, suspension, dismissal, or legal or other proceedings.

Additionally, the Standards of Conduct support the Code of Values and are intended to offer guidance on its application in different issues including engaging in outside activities, handling conflict of interests, and using social media.

Source: (Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, 2019[19]; Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, 2019[20]).

The Commissioner could establish guidance on managing and preventing conflict of interest for their employees

Managing conflicts of interest in the public sector, including in oversight bodies, is crucial. If conflicts of interest are not detected and managed, they can undermine the integrity of decisions or institutions, and lead to private interests capturing the policy process. “Conflict of interest” can be understood to mean “a conflict between the public duty and private interests of a public official, in which the public official has private-capacity interests, which could improperly influence the performance of their official duties and responsibilities” (OECD, 2004[21]).

Currently, the office of the Commissioner does not have specific guidance in place to support staff in identifying and managing their potential or actual conflicts of interest. As such, in addition to developing a Code of Ethics, the Commissioner could also elaborate guidance for staff on managing and preventing conflicts of interest. This is particularly important given the Commissioner’s investigatory role. Indeed, given the nature of the complaints process and the size of Malta, there could be situations in which a member of the office of the Commissioner has private interests that could intersect with their public duty. While these situations may not lead to an actual conflict of interest, they could be perceived as potentially influencing the official’s impartiality and therefore need to be managed.

To that end, the Commissioner could develop guidance that clarifies what conflict of interest is (as applicable to the office’s staff), how to identify conflict of interest and to whom, and how to manage and prevent conflict of interest. In terms of clarifying what conflict of interest is, there are two types of approaches: a descriptive approach (defining a conflict of interest in general terms) or a prescriptive one (defining a range of situations considered as being in conflict with public duties) (OECD, 2020[8]). In line with a prescriptive approach, OECD countries have considered the following types of external activities and positions as those which could lead to a potential conflict of interest:

Regarding when conflicts of interest could be identified, the policy could cover several opportune moments. First, upon taking up their duties in the office of the Commissioner, all new staff could be required to submit a conflict-of-interest declaration to the Commissioner. Second, staff could be required to disclose a conflict of interest when a new conflict arises – for example, a staff member’s partner takes on a new job that leads to a real or potential conflict with the activities carried out by the staff within the office of the Commissioner. Finally, staff members who are specifically involved in investigations could be required to disclose any real or potential conflicts of interest when a new case is received. This will ensure that any conflicts are dealt with prior to undertaking an investigation, to protect the integrity of the process. With regards to who should receive the declarations, given the size of the office, it is reasonable that the Commissioner could receive the conflict-of-interest declarations.

Regarding what measures could be taken to manage or resolve a conflict of interest, good practice suggests applying measures that are proportionate to the functions occupied and the potential conflict of interest situation. To that end, measures could include one or more of the following:

Recusal of the public official from involvement in an affected decision-making process.

Restriction of access by the affected public official to particular information.

Transfer of the public official to duty in a non-conflicting function.

Re-arrangement of the public official's duties and responsibilities.

Assignment of the conflicting interest in a genuinely 'blind trust' arrangement (OECD, 2004[21]).

The following provides a detailed summary of the recommendations for enhancing the effectiveness of the office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. The recommendations contained herein mirror those contained in the analysis above.

References

[4] Committee on Standards in Public Life (2021), Upholding Standards in Public Life, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1029944/Upholding_Standards_in_Public_Life_-_Web_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

[1] Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (2016), Recommended Benchmarks for Codes of Conduct applying to Members of Parliament, https://www.cpahq.org/media/3wqhbbad/codes-of-conduct-for-parliamentarians-updated-2016-7.pdf.

[14] Government of Canada (1985), Parliament of Canada Act, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/p-1/page-17.html#h-391298.

[6] Government of Malta (2018), Standards in Public Life Act Chapter 570, https://legislation.mt/eli/cap/570/eng/pdf.

[17] House of Commons (n.d.), Job description, https://housesofparliament.tal.net/vx/lang-en-GB/mobile-0/appcentre-11/brand-2/candidate/download_file_opp/1646/20709/1/0/e8597bc2cb3156e8b2e3564656514fb60638fc54 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

[3] House of Commons Committee on Standards (2022), Review of fairness and natural justice in the House’s standards system, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9146/documents/159562/default/ (accessed on 19 May 2022).

[7] Mancuso, M. (1993), “Ethical Attitudes of British MPs”, Parliamentary Affairs, Vol. 46/2.

[10] McCaffrey, R. (2020), Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly, Topical issues in other legislatures, http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2017-2022/2021/standards_privileges/2421.pdf.

[18] Miller, G. (1955), “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information”, Psychological Review, Vol. 101/2, pp. 343-352, http://www.psych.utoronto.ca/users/peterson/psy430s2001/Miller%20GA%20Magical%20Seven%20Psych%20Review%201955.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2018).

[9] OECD (2021), Lobbying in the 21st Century: Transparency, Integrity and Access, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c6d8eff8-en.

[8] OECD (2020), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en.

[11] OECD (2018), Behavioural Insights for Public Integrity: Harnessing the Human Factor to Counter Corruption, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264297067-en.

[12] OECD (2016), Committing to Effective Whistleblower Protection, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252639-en.

[16] OECD (2015), Dominican Republic: Human Resource Management for Innovation in Government, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264211353-en.

[21] OECD (2004), “OECD Guidelines for Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service”, in Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service: OECD Guidelines and Country Experiences, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264104938-2-en.