4. Towards more inclusive growth

Income inequalities and the risk of poverty are limited in Hungary. This is largely related to existing social transfers. Nevertheless, there is room to achieve the same result in a more cost-effective way by improving the targeting of those transfers. At the same time, inequalities of opportunities are a substantial issue. Women face significant employment and pay gaps compared to men. Moreover, social mobility from one generation to the next is limited, which is related to the education system. Public education spending is low in international comparison and students’ achievements are closely related to their socio-economic background. The COVID-19 pandemic also revealed weaknesses in the social protection of workers. Addressing them would require devising a permanent short-time work scheme that could be activated rapidly during recessions, as well as relaxing eligibility conditions for unemployment benefits and extending their duration, at least during recessions.

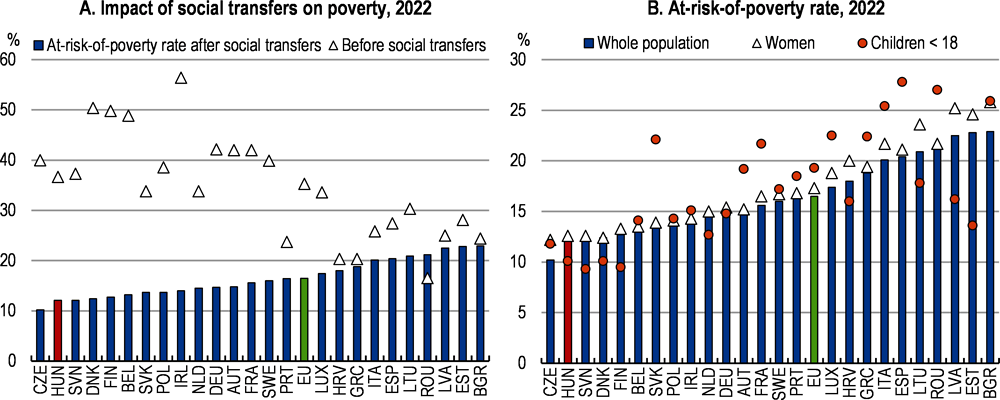

Income inequalities are limited in Hungary. In particular, the share of poor people is the second lowest in the EU, and the existing social transfers largely contribute to this outcome. Without such transfers, the poverty rate would be above the EU average (Figure 4.1, Panel A). In contrast to other countries, there is no significant difference in poverty rates between men and women, or between different age groups (Figure 4.1, Panel B). Nevertheless, the Roma population, representing 7% of the total population in Hungary, is facing a poverty rate of 33%, significantly above the general population poverty rate of 12%.

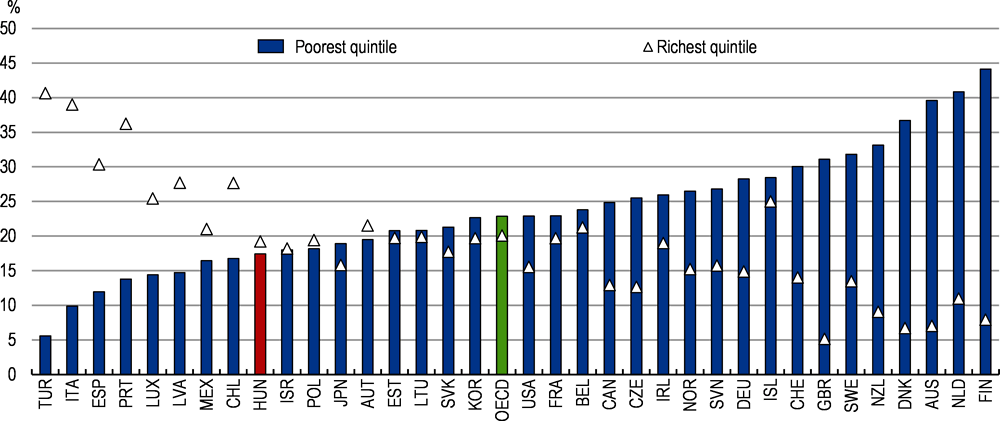

Even though social transfers significantly reduce poverty on average, the same result could be achieved in a more cost-effective way by better targeting transfers at low-income people. Current transfers are not well-targeted to those most in need. In 2020, Hungarians in the upper income quintile received a larger fraction of social transfers than those in the lower income quintile (Figure 4.2). By contrast, 25% of transfers accrued to the poorest income quintile in Czechia, and up to 45% in Finland, while 13% and 8% accrued to the richest quintile, respectively.

While other transfers may play a role as well, the low level of minimum income benefits and the universality of most family benefits contribute to the lack of targeting of social transfers in Hungary. The minimum income benefit is only about 20% of the poverty threshold, one of the lowest levels in the EU. Moreover, most family benefits in Hungary are not means-tested. This includes the family allowance, the childcare allowance, and the child-raising support. The family allowance is granted to parents of children below compulsory school age, children aged below 16 attending compulsory school education, and children aged below 20 attending public education or vocational training establishments. The childcare allowance is granted to parents raising children aged below 3, and the child-raising support is granted to parents of families with at least three children (OECD, 2022[1]).

Avoiding non-take up by households in need may be an argument for having a minimum universal child benefit for all families to ensure continuously low child poverty. At the same time, additional family benefits may be made available subject to means-testing to improve targeting. Italy implemented such a reform of its family support in 2022, merging six family benefits into one universal benefit, topped up with additional benefits that are means-tested based on income and wealth criteria (OECD, 2022[2]). Means-testing is widely used in the OECD countries where social transfers are well targeted (Box 4.1). Considering the large empirical evidence demonstrating the impact of parental income and income shocks on children’s cognitive development and school attainment (OECD, 2018[3]), a better targeting of family benefits towards low-income families may contribute to increase intergenerational mobility, which is currently low in Hungary (see below).

The resulting targeting may be further reinforced by using the realised savings to increase minimum income benefits and ensuring that they reach all people in need, including in the Roma population. Looking ahead, a comprehensive review of existing social transfers in Hungary would be useful to better understand to what extent they reach the lowest parts of the income distribution, and how their targeting could be further improved while keeping poverty low.

In Denmark, housing benefits may only be granted based on a means test taking into account households’ income and financial wealth. Moreover, housing rentals can only be subsidised up to a certain limit. All child and youth benefits are also means tested.

In the Netherlands, housing benefits are means tested and subject to the condition that households always pay part of the rent themselves. There are two child benefit systems. The general child benefit is not means-tested, but the higher additional child benefit is subject to a means test. Childcare benefits are also means tested.

In Sweden, all social assistance programs are means tested. The Early Childhood Education and Care benefit is means-tested based on income, but other social assistance programs are subject to wealth criteria as well.

Source: OECD Tax-benefit Database: Description of policy rules for Sweden (2022), OECD Tax-benefit Database: Description of policy rules for the Netherlands (2022), OECD Tax-benefit Database: Description of policy rules for Denmark (2022).

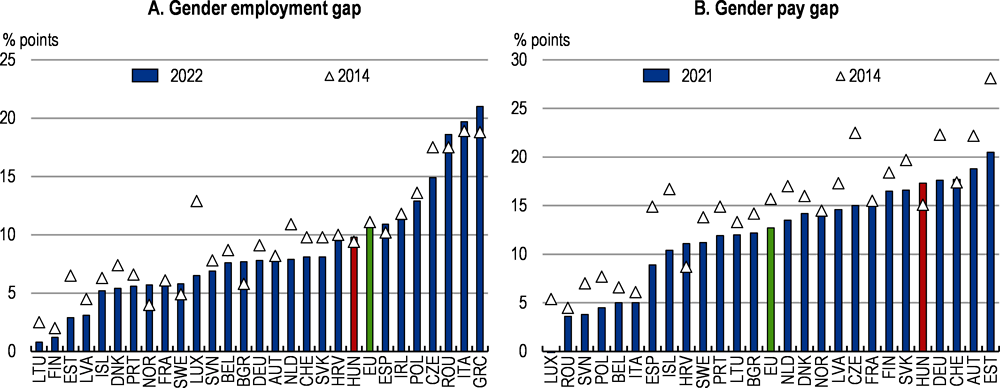

While social transfers and family structures manage to keep women out of poverty, women face significant employment and pay gaps compared to men. In 2022, the employment rate of men was 10 percentage points higher than the one of women, and their wage 17% higher (Figure 4.3). Nevertheless, there is no significant difference in the propensity of men and women to work part-time.

Gender wage gaps may have different causes, and understanding their origin is a pre-condition for devising effective policies. A first explanation is related to pure labour market discrimination against women. A second explanation is that after the birth of their first child, women may accept lower wages in return for the non-monetary benefit of flexible working arrangements which allow them to spend more time in unpaid work at home. A third explanation is that, after the birth of their first child, women may transition to more flexible working schedules than men. As a consequence, they may not develop the skills and professional networks that would allow them to climb the wage ladder. While the second and third explanations are both related to maternity, the third one supports the idea that wage gaps may increase with age.

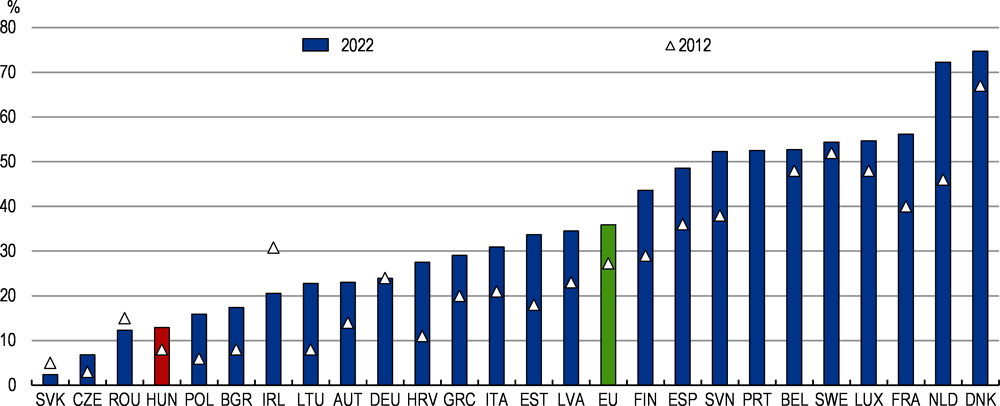

The available evidence shows that pure labour market discrimination between men and women does not play a significant role in explaining the gender wage gap in Hungary. This gap is mostly related to maternity and does not increase with age (Ciminelli, Schwellnus and Stadler, 2021[4]). The adequate policy response in this case would be to promote flexible working arrangements such as teleworking and part-time work, promote a more equal sharing of parental leave and flexible working arrangements between men and women. This can be complemented with improved access to early childcare facilities. Hungary already provides universal childcare benefits to make childcare more affordable, but only few nursery places are available, as highlighted in the 2021 OECD Economic Survey of Hungary (OECD, 2021[5]). While the number of places for young children in childcare facilities has increased by nearly 20% between 2017 and 2022, less than 13% of children under the age of three benefitted from formal childcare in 2022. This is far below the EU average, even considering measurement uncertainty (Figure 4.4). Expanding the number of places in childcare facilities should remain a priority, as acknowledged by the government. That would contribute to reduce both the wage gap and the employment gap between men and women. Potential fiscal savings achieved by providing more targeted transfers to families (see above) could be used to finance additional childcare places.

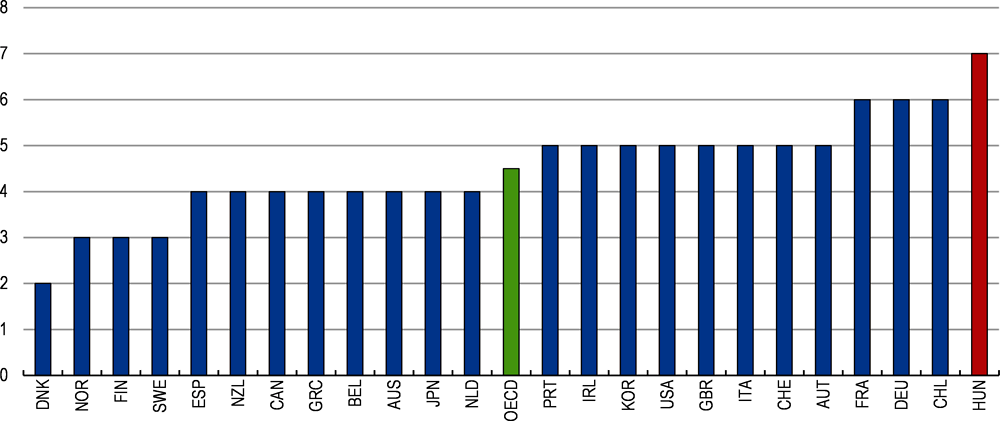

Inequalities of opportunities are not only significant between men and women. They are also high across people from different economic backgrounds. Social transfers keep income inequalities low at a given point in time, but moving up the income ladder is difficult in Hungary. With current intergenerational mobility, it would take on average seven generations for low-income family children to reach the average income, versus only two or three generations in Scandinavian countries (Figure 4.5).

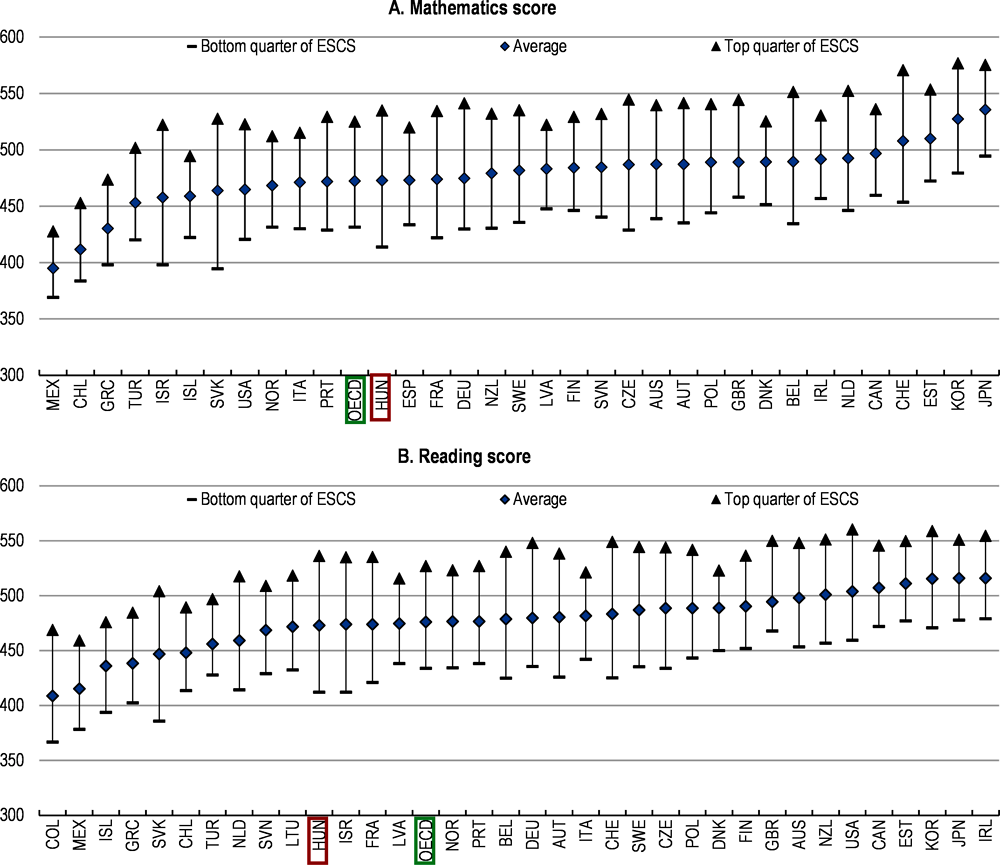

The low income mobility across generations is at least partly related to the education system. Hungary’s educational outcomes measured by the OECD PISA survey are not significantly different from the OECD average, but they are more dispersed and tend to reproduce inequalities from one generation to the next (OECD, 2023[6]). The achievements of Hungarian students are closely related to the socio-economic status of their parents. For example, PISA outcomes in mathematics are 30% better among students from the highest socio-economic background than among those from the lowest socio-economic background. Other countries such as Latvia manage to have a similar average performance with a lower dispersion between students with different socio-economic backgrounds (Figure 4.6).

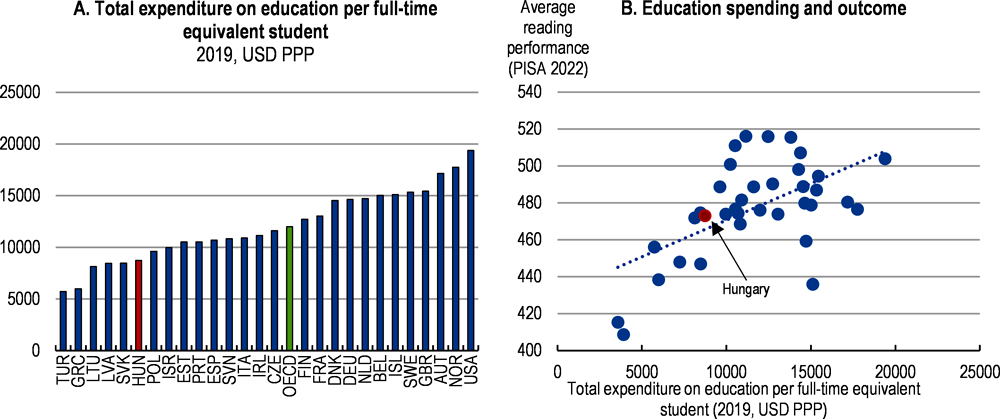

Reforms of the education system can contribute to improving education outcomes and avoid that socio-economic advantages or disadvantages are passed from one generation to the next. The low average student performance and the disparity between students with different backgrounds coincides with low education spending in Hungary (Figure 4.7). In OECD countries, the correlation between the number of years of education across parents and children, which is a proxy for education persistence, is lower in countries where public spending on education is higher (OECD, 2018, pp. 298-299[3]). Nevertheless, the efficiency of education spending also varies significantly across countries, and while spending more on education should be a long-term objective in Hungary, there is also room to undertake a review of education spending to see how to improve its efficiency.

One possible avenue to reduce the influence of the socio-economic background on education outcomes would be an expansion of early childhood education for children below three. This is often the part of the education system with the highest returns on public spending, not only in terms of average outcomes but also for reducing inequalities (Heckman, 2008[7]). Empirical evidence from the United States and Norway suggests that early childhood education is particularly effective in remedying initial cognitive and social development disadvantages of children from less stimulating family backgrounds (Heckman and Masterov, 2007[8]) (Havnes and Mogstad, 2015[9]).

The way funding is allocated to schools also matters for equity. Evidence from the United Kingdom shows that the sorting of pupils into schools plays an important role in explaining why the test scores of richer and poorer children diverge (Crawford et al., 2016[10]). Funding combining both horizontal equity – schools with similar characteristics are funded at the same level – and vertical equity – schools with higher needs receive higher resources – allows to account for students’ educational needs relating to socio-economic disadvantages and learning difficulties. It can be used, for example, to provide further help to pupils, such as additional teaching time, specialized learning material, and in some cases smaller classes. Such type of funding has been adopted in Australia, Canada, Chile, and the Netherlands (OECD, 2018[3]).

Developing a more supportive learning environment also comes through recruiting and training teachers and fostering effective learning strategies. Teacher quality is particularly important to support the long-term success of children in disadvantaged areas: students assigned to high value-added teachers, measured by how much they improved children test scores on average, are more likely to attend higher-ranked colleges, earn higher salaries, and live in higher socio-economic status neighbourhoods (Chetty et al., 2014[11]). For a majority of countries, a larger proportion of more experienced teachers teach in less challenging schools than in more challenging schools. Some countries have put in place proactive approaches to reverse this trend. In Japan and Korea, teachers and principals are often reassigned to different schools so that the most capable professionals are more equally distributed. Getting the best teachers to teach in disadvantaged schools may also require higher pay. While results from France show that the salary increase needs to be sizeable to provide a sufficient incentive (Prost, 2013[12]), non-financial incentives such as faster career progression, or the free choice of a new assignment after having served in a disadvantaged school, can also be used to complement financial incentives.

Flexible schooling and adapting teaching methods and programme contents to the needs of disadvantaged students can help improve achievements. In the United States, “charter schools” are public schools that enjoy greater leeway to manage staff, adapt curricula and organise teaching time. They often target students from disadvantaged backgrounds. A substantial body of research finds that charter schools can exert a significant, lasting impact on educational attainment and the later employment of disadvantaged youth (OECD, 2016[13]). Such examples could be adapted to the Hungarian context in order to target specific groups of disadvantaged students, including among the Roma population.

Vocational training programmes, in which students from disadvantaged socio-economic background tend to be disproportionally represented, have a key role to play to help these students move up the income ladder. In Hungary, a large share of upper-secondary students are enrolled in vocational programmes and all of these programmes now combine school- and work-based learning, well above the OECD average of 45% (OECD, 2023[14]). Upper-secondary vocational graduates in Hungary also have a high employment rate, exceeding that of upper-secondary graduates from the general education system. Nevertheless, access to tertiary education for students enrolled in vocational education is more limited in Hungary than in most other OECD countries, as 40% of VET programmes do not provide a pathway to access tertiary education after successful completion. In such cases, restarting secondary education and obtaining the baccalaureate is required to access tertiary education. This share is twice as high as the OECD average (OECD, 2023[14]). Creating additional pathways to higher education would offer VET graduates more opportunities for lifelong learning and career progression.

The design of unemployment or in-work benefits is key to mitigate the impact of economic shocks on workers’ income and career path. The recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic provided a stress test for the Hungarian social protection system of workers and revealed some weaknesses.

The short-time work scheme did not avoid large income losses for the poorest during the pandemic

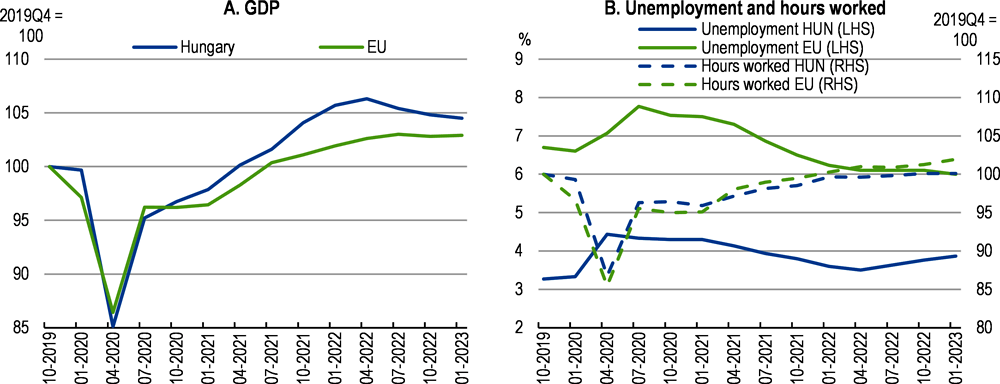

In most European countries, the recession triggered by the pandemic led to much larger fluctuations in hours worked than in unemployment (Figure 4.8). Hungary is no exception to this, as unemployment rose by only 1.1 percentage points between late 2019 to its peak in mid-2020. By contrast, hours worked and economic activity dropped by 15% during the first wave of the pandemic, both in Hungary and in the European Union.

This divergence of unemployment and hours worked was related to the widespread use of job retention schemes in Europe. All EU countries relied on such schemes during the pandemic, but for 15 among them including Hungary, the pandemic was the first time a job retention scheme had been applied (Baptista et al., 2021[15]) (Box 4.2). The common feature of these job retention schemes was to allow keeping work contracts in force while work was partially or fully suspended, and compensating workers for at least part of their income losses. These schemes helped to limit costly layoffs and re-hirings following a temporary disruption of economic activity. By contrast, the United States did not rely on job retention schemes but mitigated the impact of the crisis by strengthening unemployment benefits and family support. (Blanchard, Philippon and Pisani-Ferry, 2020[16]).

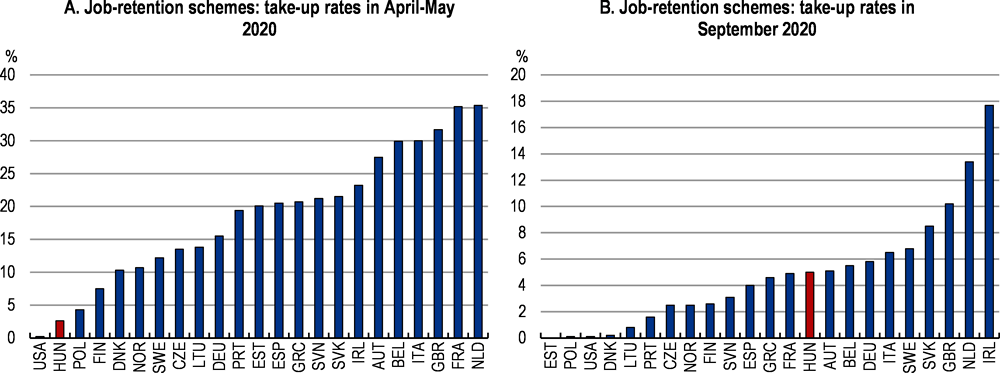

Hungary’s short-time work scheme was characterised by a low take-up rate compared to similar schemes in other OECD countries during the first wave of the pandemic in April-May 2020, partly related to its introduction only several weeks after the start of the pandemic and its initially strict eligibility conditions. The situation improved during the second wave in the autumn of 2020 (Figure 4.9).

Hungary had three major job retention schemes during the pandemic.

A first short-time work scheme was launched in mid-April 2020, a month after the state of emergency had been declared (11 March). Its eligibility conditions were very strict initially, but the government relaxed them at the end of April. While the programme initially covered 70% of wage losses for working time reduction comprised between 30 and 50% and up to HUF 75,000 per month (50% of the minimum wage at the time), it was then extended to cover 70% of wage losses for working time reduction comprised between 15 and 75% and up to HUF 112,000.

A specific programme for R&D workers was also launched in mid-April 2020. It benefitted most researchers in Hungary, even if their job was not directly threatened by the pandemic, and it was much more generous than the short-time work scheme. This programme lasted for four months and was relaunched for another five months in January 2021.

A sector-specific programme for the sectors most affected by the pandemic, mainly related to tourism, hospitality and cultural services, replaced the previous general short-time work scheme immediately after the second lockdown in November 2020. The number of eligible sectors was extended during the third pandemic wave in March 2021. The subsidy covered a maximum of 50% of the wage, and up to 150% of the minimum wage.

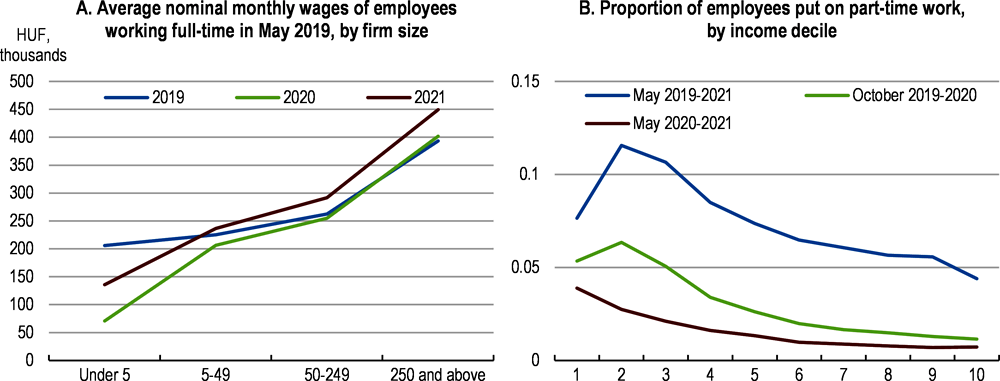

The empirical evidence available so far suggests that employees working in smaller firms or belonging to the lowest income deciles faced significant income losses during the pandemic despite the job retention schemes (Gáspár and Reizer, 2022[19]). For example, full-time workers in firms with less than 5 employees in May 2019 earned less than half of their earlier monthly salary in May 2020 on account of lower working hours (Figure 4.10). Teleworking was often not an option for low-skilled workers in services, and those at the lower end of the income distribution were more likely to see their working hours reduced during the pandemic.

In order to avoid any implementation delay during future recessions, Hungary may consider devising a permanent short-time work scheme in advance. The experience of other countries suggests that such schemes are effective in stabilising employment and allow firms to retain valuable staff during downturns, thus avoiding human capital losses due to job separations. The main drawback of such schemes is that they may hinder productive job reallocations if they continue to be used into economic recoveries to protect businesses that have become unproductive. To limit this drawback, two features should be built into their design. First, employers relying on the short-time work scheme for longer should be asked to contribute more. Second, eligibility rules should be stable. Ideally, they should be designed under normal economic conditions and not during recessions to avoid pressure to set up excessively generous schemes that may be difficult to turn off later (Cahuc, 2019[20]) (Hijzen and Martin, 2013[21]).

Unemployment benefit duration could be extended, at least during recessions

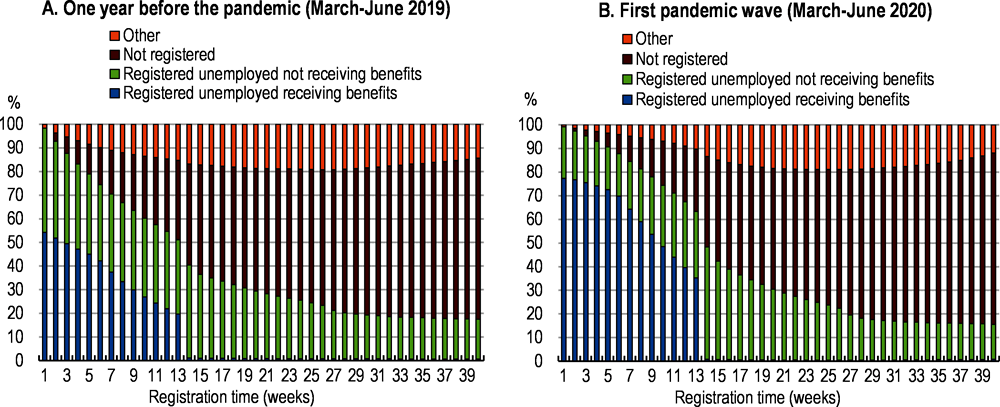

Job losses during the first wave of the pandemic resulted in a doubling of the number of people on the employment service register compared to the same period of 2019 (Boza and Krekó, 2022[22]). As the lockdowns made it more difficult than usual to find a new job, most OECD countries temporarily eased the eligibility conditions for unemployment benefits, increased benefit levels, and/or extended benefit durations. Hungary maintained its unemployment benefit system unchanged during the pandemic, despite having the shortest unemployment benefit duration in the OECD (Table 4.2).

While the proportion of jobseekers who were eligible for unemployment benefits during the first pandemic wave was higher than a year before, 20% of those who registered at the National Employment Service did not receive any benefits. Moreover, 40% of registered jobseekers, equivalent to half of those initially eligible to unemployment benefits, lost their unemployment benefits after 3 months (Figure 4.11), in a context where it was difficult to find a new job due to lockdowns and depressed economic activity.

Shorter benefit durations will generally act as an incentive to find a new position more quickly after a job loss. Nevertheless, these incentives are unlikely to be effective during recessions when the number of job vacancies is limited. Drawing on the lessons from the pandemic, eligibility criteria and benefit durations could be made more generous in times of macroeconomic downturns. For example, France made the duration of benefits contingent on macroeconomic conditions in 2023. Such a reform would account for the fact that people already unemployed at the onset of a recession or falling in unemployment during a recession will likely require more time to find a job than when economic activity is strong.

References

[15] Baptista, I. et al. (2021), Social Protection and Inclusion Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis. An Analysis of Policies in 35 Countries, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=10065&furtherNews=y.

[16] Blanchard, O., T. Philippon and J. Pisani-Ferry (2020), “A New Policy Toolkit is Needed as Countries Exit COVID-19 Lockdowns”, PIIE Policy Brief 20-8, https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/documents/pb20-8.pdf.

[22] Boza, I. and J. Krekó (2022), What Happend to Jobseekers After Being Registered?, in The Hungarian Labour Market 2020 (Á. Szabó-Morvai et al. editors), https://kti.krtk.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/MT2020_teljes-kotet.pdf.

[20] Cahuc, P. (2019), “Short-Time Work Compensation Schemes and Employment”, IZA World of Labour, https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/485/pdfs/short-time-work-compensations-and-employment.pdf?v=1.

[11] Chetty, R. et al. (2014), “Where is the land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States *”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 129/4, pp. 1553-1623, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022.

[4] Ciminelli, G., C. Schwellnus and B. Stadler (2021), “Sticky floors or glass ceilings? The role of human capital, working time flexibility and discrimination in the gender wage gap”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1668, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/02ef3235-en.

[10] Crawford, C. et al. (2016), “Higher Education, Career Opportunities, and Intergenerational Inequality”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 32/4, pp. 553-575, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grw030.

[23] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2022), 80% of Roma Live in Poverty, https://fra.europa.eu/en/news/2022/80-roma-live-poverty.

[19] Gáspár, A. and B. Reizer (2022), Average Wages at Exceptional Times. Wage Trends in Hungary during the First 18 Months of the Coronavirus Pandemic, in The Hungarian Labour Market 2020 (Á. Szabó-Morvai et al. editors), Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Institute of Economics, https://kti.krtk.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/MT2020_teljes-kotet.pdf.

[9] Havnes, T. and M. Mogstad (2015), “Is universal child care leveling the playing field?”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 127, pp. 100-114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.04.007.

[7] Heckman, J. (2008), “Schools, skills and synapses”, Economic Inquiry, Vol. 46/3, pp. 289-324, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x.

[8] Heckman, J. and D. Masterov (2007), “The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children”, Review of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 29/3, pp. 446-493, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2007.00359.x.

[21] Hijzen, A. and S. Martin (2013), “The Role of Short-Time Work Schemes during the Global Financial Crisis and Early Recovery: A Cross-Country Analysis”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, https://docs.iza.org/dp7291.pdf.

[17] Krekó, J. and J. Varga (2022), Job Retention Wage Subsidies during the Pandemic in Hungary, in The Hungarian Labour Market 2020 (Á. Szabó-Morvai et al. editors), Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Institute of Economics, https://kti.krtk.hu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/MT2020_teljes-kotet.pdf.

[6] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results - Factsheet - Hungary, https://www.oecd.org/publication/pisa-2022-results/webbooks/dynamic/pisa-country-notes/3df2ae68/pdf/hungary.pdf.

[14] OECD (2023), Spotlight on Vocational Education and Training: Findings from Education at a Glance 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acff263d-en.

[18] OECD (2022), OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en.

[1] OECD (2022), The OECD Tax-Benefit Database - Description of Policy Rules for Hungary, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/TaxBEN-Hungary-latest.pdf.

[2] OECD (2022), The OECD Tax-Benefit Database - Description of Policy Rules for Italy, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/TaxBEN-Italy-latest.pdf.

[5] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1d39d866-en.

[3] OECD (2018), A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-en.

[13] OECD (2016), Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en.

[12] Prost, C. (2013), “Teacher Mobility: Can Financial Incentives Help Disadvantaged Schools to Retain Their Teachers?”, Annals of Economics and Statistics 111/112, p. 171, https://doi.org/10.2307/23646330.