Executive summary

After a strong recovery, economic activity has slowed on the back of higher energy prices and cost of living. Inflation has fallen significantly since its peak in October 2022, but underlying price pressures have remained high.

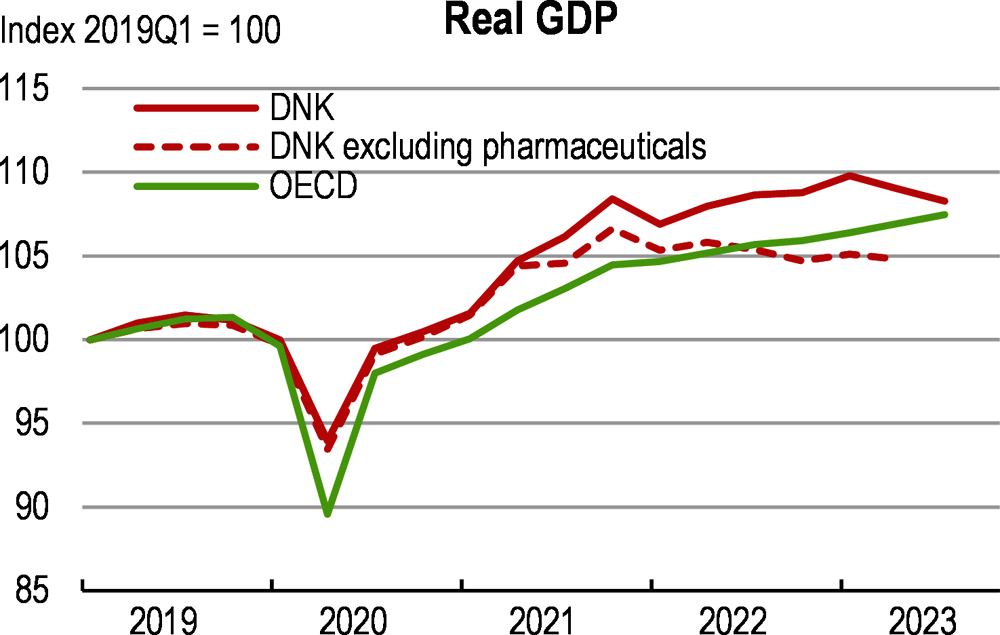

The economy has been running at two speeds and growth has decelerated (Figure 1). Activity in the pharmaceutical sector has been buoyant, contributing alongside shipping exports to the current account surplus reaching 13.4% of GDP in 2022. Excluding this sector, GDP dropped in the first half of 2023. Employment has continued to grow albeit at a slower pace. Consumption and investment have decelerated as strong inflation has hit household purchasing power and financial conditions have tightened. Higher borrowing costs have contributed to the weakening of the housing market.

Inflation receded in the first half of 2023, but at 3% in November, core inflation remains elevated. Soaring energy prices pushed inflation in 2022 to its highest level since the 1980s as in most OECD countries, despite a relatively low energy dependency. Domestic price pressures from wages have increased but remain contained so far.

Growth will remain subdued (Table 1). Wages will continue to adjust to higher prices, sustaining consumption. Exports will remain relatively strong as the economic situation improves in main trading partners, but the contribution of the pharmaceutical sector may fade. Higher interest rates will keep the housing market weak and investment low. Headline inflation is expected to fall to 2.5% by 2025.

Risks to the outlook relate to more persistent inflation. This could result from stronger than expected wage growth. Monetary policy is bound by the peg to the euro and the central bank is expected to follow decisions of the European Central Bank. Fiscal policy will need to be tightened if inflationary pressures continue or intensify relative to the euro area.

The financial sector has been resilient so far. Credit losses have remained low, despite fast rising interest rates. The banking sector is well capitalised with adequate liquidity buffers, but medium-sized banks are exposed to commercial real estate risks, where activity has declined sharply. Household gross debt has declined, real and financial household assets are significant, but indebtedness remains among the highest in the OECD. The share of variable-rate mortgages has risen, and loan-to-value ratios are high, increasing the risk of defaults, although the capacity to repay is strong. While the housing market is currently adjusting, macroprudential policies should be strengthened to manage the cycle in the medium term.

The public finances are robust. The government budget has been in surplus since 2017, public debt is low and a strong budgetary framework is in place. Public support to households and firms in response to rising energy prices has been limited but appropriate overall. Measures targeted to the most vulnerable helped to cushion the increase in the cost of living, but the deferred indexation of social benefits to wages induced large temporary losses in purchasing power for those out of work.

Despite successful pension reforms and rising employment rates among older workers, population ageing poses risks to the Danish social model. Public spending on welfare services will increase, while the working age population will decline. While fiscal space is currently significant, further meeting the fiscal rules will imply achieving savings after 2030.

Reducing the regulatory burden on local governments, as planned, can help to achieve efficiency gains. The impact of the reform on the quality of services across territories needs to be carefully monitored. Other policy avenues for efficiency gains include improving public procurement, deepening cooperation across municipalities and reforming public employment services.

Long-term fiscal sustainability plans rely on relatively large increases in effective retirement ages and private pension schemes. Strict indexation of the legal retirement age is projected to increase it to the highest level in the OECD and risks inducing a wider likelihood to use disability-based early retirement schemes. Reform of early retirement schemes should ensure people with reduced work capacity remain in the labour market as far as possible.

Denmark is highly dependent on trade and on a few firms and sectors. Diversifying economic activity would reduce risks and help to benefit from new opportunities, including those presented by the climate transition.

Denmark’s deep integration into global value chains has large economic benefits but exposes the country to international risks. Denmark has a large and persistent current account surplus and the concentration of exports in a few sectors increases dependence on sector-specific trade policies and regulations abroad.

Improvements in business conditions can help a wide range of firms to thrive in the digital and green transitions. Digitalisation is reshaping competitive dynamics and competition policy needs to be adapted. There is room to increase the weight of young firms in the economy. The entrepreneurial ecosystem generates innovative businesses, but more could be done to support R&D, facilitate cooperation between universities and businesses, and make entrepreneurship more inclusive.

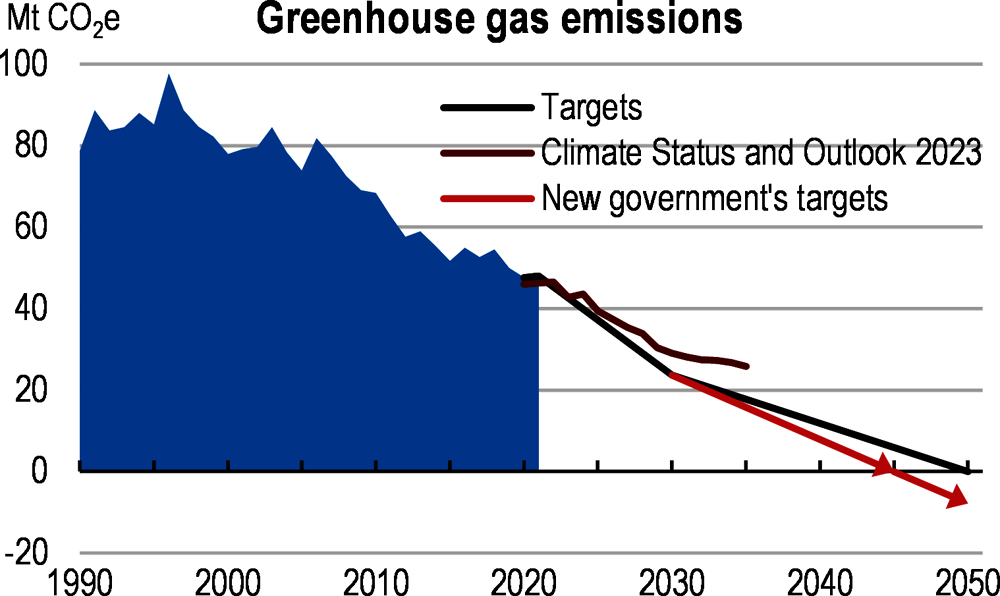

Denmark has put in place ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and made significant strides in achieving efficient climate change mitigation policies. However, further action is needed to encourage technological advancements and greater emission reductions across sectors (Figure 2). The green tax reform expands the coverage and sets a path for wide-ranging carbon pricing from 2025 onwards. Consistency with the EU Emission Trading Scheme II needs to be ensured.

The green tax reform needs to be completed to accelerate emission reductions and avoid distortions across sectors and technologies. Introducing a tax on emissions from agricultural production as currently under discussion could help achieve this in a cost-efficient way. Tax revenues could be used to compensate socio-economic costs in emission-intensive activities.

Moving to a carbon neutral economy entails accelerating electrification of the energy mix and further expanding green power production capacity. This requires finding agreements at the local level and reducing administrative barriers to investment and infrastructure development. Legislation to simplify planning and approval procedures and prioritise energy infrastructure over local concerns could significantly speed up the deployment of renewable energy sources.

Population ageing and the digital and green transitions are transforming jobs and skills requirements, calling for agile labour and education policies. Persistent labour shortages are holding back growth and complicating the provision of welfare services.

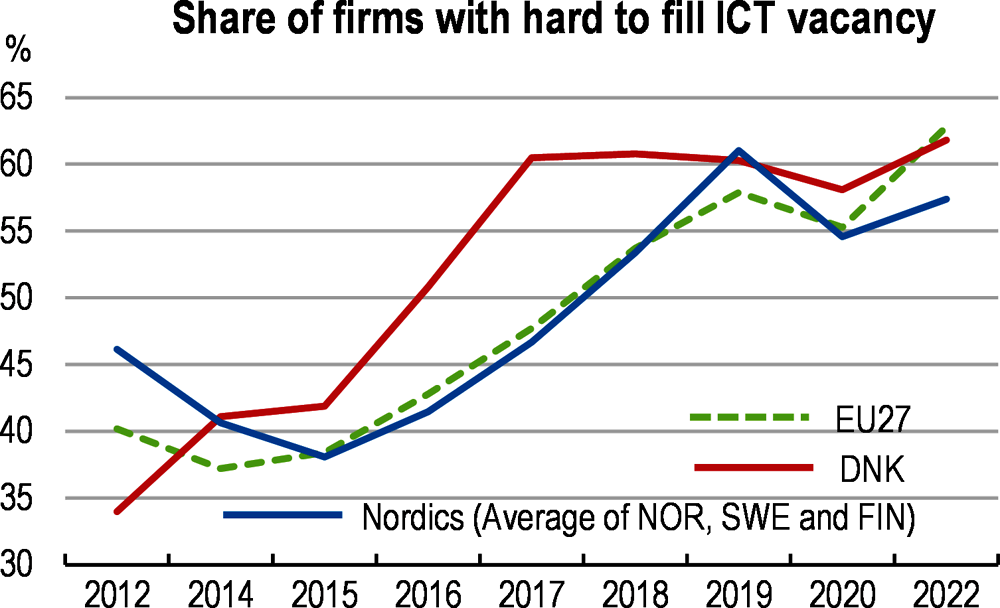

Despite the economic slowdown and rising labour force participation and migration, recruitment difficulties persist and remain elevated in many sectors, such as long-term care and ICT (Figure 3). The labour force is not fully mobilised due to structural factors, including late labour market entry by the young and early retirement.

Activation policies have proved effective in helping workers in transitions and during economic shocks. The government announced a reform of public employment services to reduce the cost of activation policies. Ineffective programmes should be phased out. Contracting out employment services to private providers and enhancing the digitisation of services could be considered, but careful monitoring of the reform is needed.

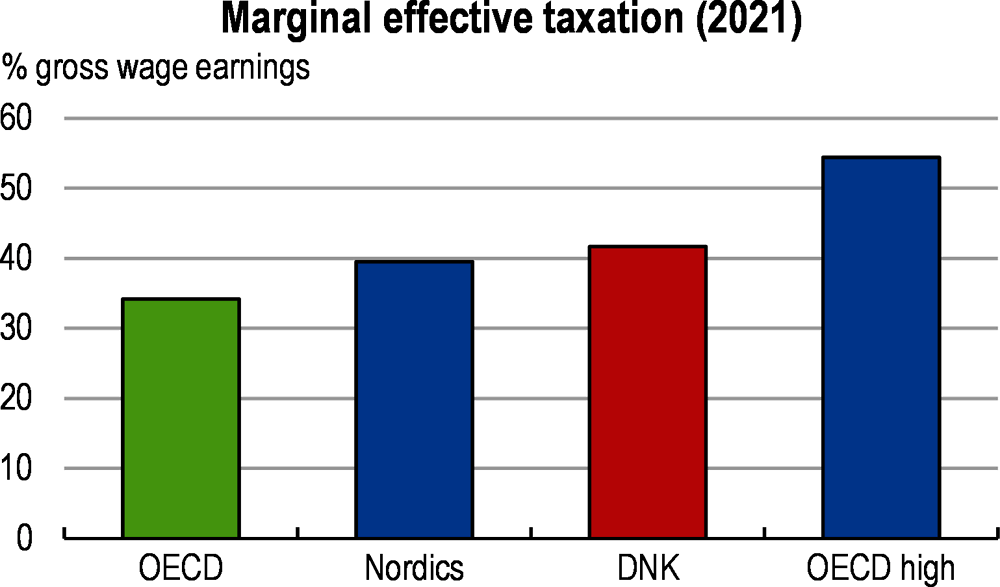

Moving taxation further away from personal income to housing would bolster work incentives. The planned cut of the personal income tax is a step in the right direction, but more needs to be done to reduce the fiscal burden on work effort (Figure 4). Lessening the favourable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing would improve the functioning of the housing market and create an opportunity to lower labour taxes further.

There is room to facilitate the recruitment of foreign-born workers where there are shortages. Several relaxations of migration policies have been or are expected to be actioned. Further easing eligibility requirements in shortage areas, as well as streamlining and reducing administrative burdens, can contribute to addressing acute recruitment issues.

Education reform can speed up youth entry into the labour market. Limiting the duration of very generous student allowances as planned will help to reduce graduation ages. Replacing grants by income contingent loans for master’s degrees and targeting the voluntary tenth year in lower secondary education to students with the greatest learning needs should also be considered.

While it has the potential to address skills needs, too few students opt for vocational education and training. Lack of mobility between vocational and academic tracks deters students, calling for developing programmes across tracks. Case-based teaching can increase awareness of the opportunities offered by vocational education.

Second-generation migrants are often concentrated in the same schools, with a greater probability to leave school early. Raising awareness of different school enrolment options among immigrant parents and more effective second-chance programmes could improve school diversity and reduce dropouts.