Executive summary

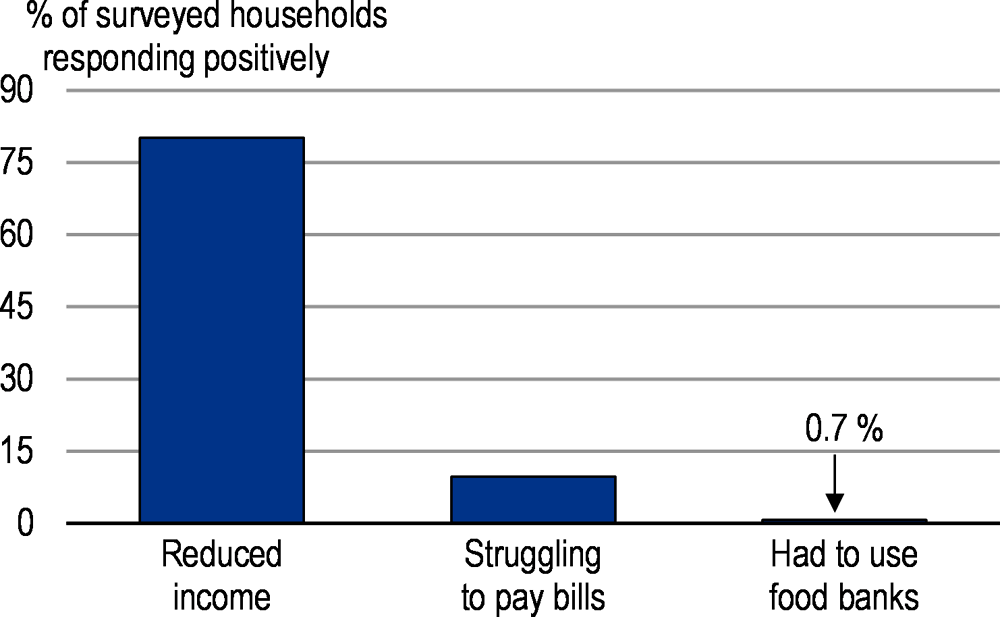

Like many countries, the United Kingdom has been hit severely by the COVID-19 outbreak. A strict lockdown, was essential to contain the pandemic but halted activity in many key sectors. While restrictions have eased, the country now faces a prolonged period of disruption to activity and jobs, which risks exacerbating pre-existing weak productivity growth, inequalities, child poverty and regional disparities (Figure 1). On-going measures to limit a second wave of infections will need to be carefully calibrated to manage the economic impact. The country started from a position of relatively high well-being on many dimensions. But productivity and investment growth have been weak in recent years and an ambitious agenda of reforms will be key to a sustainable recovery. Leaving the EU Single Market, in which the economy is deeply integrated, creates new economic challenges. Decisions made now about management of the COVID-19 crisis and future trade relationships will have a lasting impact on the country’s economic trajectory for the years to come.

The Government has moved quickly to support the economy, while continuing to prepare the exit from the EU Single Market and the Customs Union and to pursue policies to address weak productivity and investment. Since March, monetary and fiscal policies have eased significantly and major programmes were implemented to protect workers and firms to prevent long-term economic scars. Since July 2020, the Government has moved to a new phase of support with the Plan for Jobs and the Winter Economic Plan. It has phased out some emergency measures, extended and introduced others, including programmes to help people get back to work, incentives to promote social consumption, and temporary reductions in VAT rates for the hospitality sector and stamp duty on property transactions. The Industrial Strategy, a multidimensional approach intended to foster productivity growth in place since 2017, includes measures that will also help to boost investment, innovation and skills.

The economy contracted sharply in Spring 2020 and unemployment is likely to increase (Table 1). The COVID-19 crisis occurred against the background of subdued growth and investment since 2016. Many activities fell sharply during the lockdown, but some have since picked up substantially. Nevertheless, overall demand is set to recover only gradually as consumer-facing sectors remain disrupted and due to higher unemployment and business closures leaving scars on the economy.

The outlook is exceptionally uncertain. A resurgence of COVID-19, leading to further lockdown measures would lead to weaker growth, higher unemployment and even greater pressure on balance sheets. A disorderly exit from the EU Single Market, without a trade agreement with the European Union, would have a major negative impact on trade and jobs.

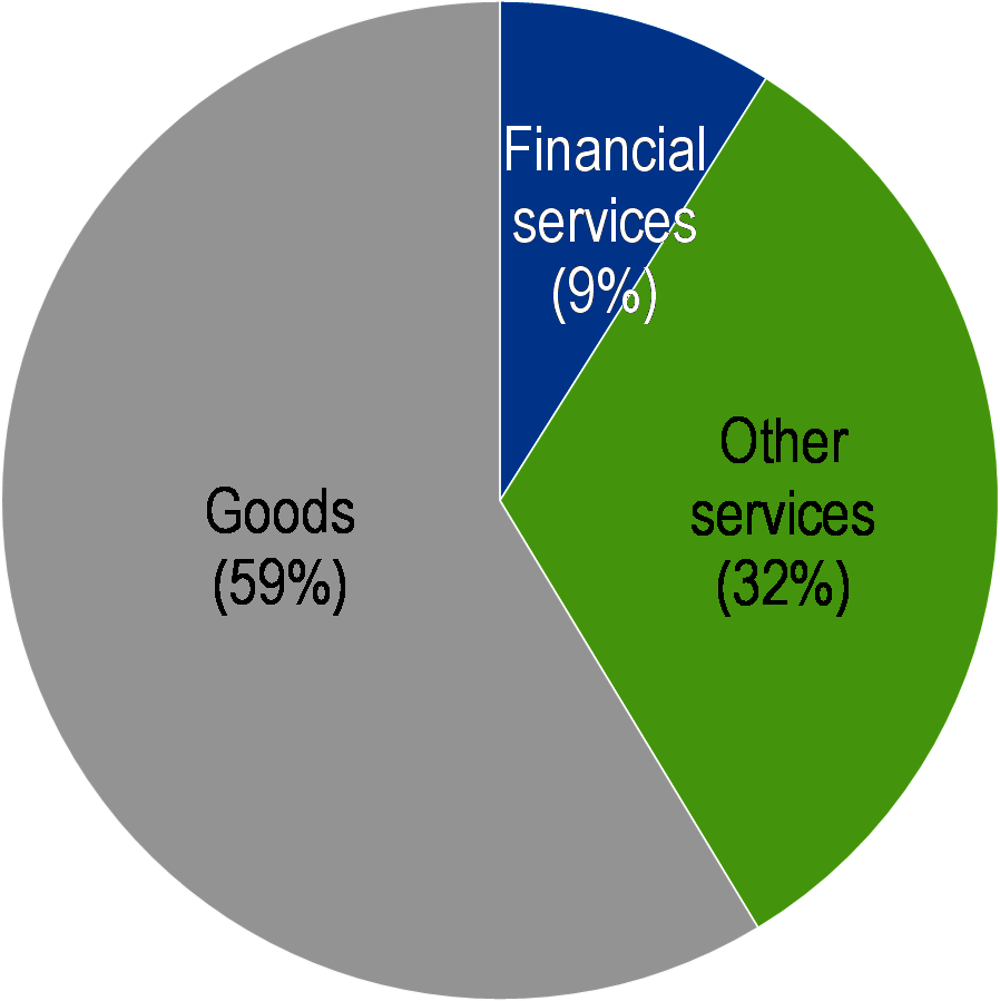

Agreeing a close trade relationship with the European Union would support recovery, productivity and employment for both parties. While negotiations have focused on maintaining low trade frictions on goods, trade in services is crucial for a service-based economy such as the United Kingdom (Figure 2). Following exit from the Single Market, UK-based financial institutions will lose their passporting rights. Keeping close relationships with the European Union will help to limit costs.

Implementation of a multifaceted package will help support a sustainable recovery following COVID-19 and raise growth potential. The supportive fiscal policies already in place will hasten the recovery but further measures will be needed to mitigate scarring. The scope for further monetary easing is limited but low interest rates provide fiscal space. A key challenge will be ensuring that people in activities that are lastingly impacted by the COVID-19 crisis are able to move to new activities and do not become detached from the labour market.

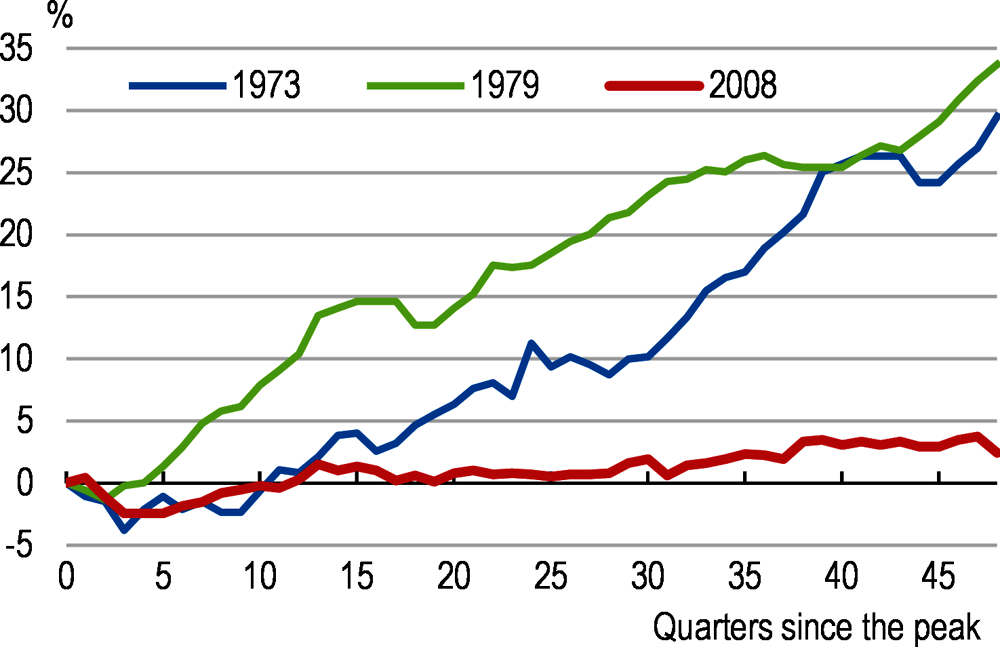

Well-directed good-quality public investment and higher private investment are needed to strengthen the recovery and boost productivity. Low investment and innovation rates have been key factors behind the weak productivity performance of past years (Figure 3). Adoption rates of complex technologies lag best performers. The competition framework is well designed but will need to be adapted to changes in business models triggered by digitalisation. Land-use restrictions impede effective competition. The Government has accelerated the substantial increase already underway in funding to housing, transportation and R&D investment. Policy continuity in other areas of the Industrial Strategy should be ensured to sustain progress in economic development. The long-standing challenge of narrowing regional differences, which may be exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, requires investing in the capacity of lagging regions. There is a commitment to invest 0.2% of GDP in broadband infrastructure by 2025. Emergency support to firms has prevented business failures but will need to be better targeted to viable firms.

The Government has started to exit from emergency employment measures, while implementing new measures with the Plan for Jobs and the Winter Economic Plan to support low-income and youth workers. The Job Retention Scheme has helped to prevent massive layoffs during the lockdown. It is being phased out and will be replaced by a new six-month wage subsidy programme at the end of October. A bonus was introduced to encourage firms to continue to employ furloughed workers through to 2021. Although unemployment benefits remain low by international standards, the Universal Credit and Working Tax Credit payments temporary increase has supported incomes in response to the crisis. A temporary wage subsidy scheme, Kickstart, has been introduced to encourage the hiring of young people. Resources were also allocated in July for job search and training. Additional spending on active labour market measures are welcome and further increases would help to accompany unemployed workers in their job search and ease adjustment to new working arrangements, alongside measures to strengthen adult education and training.

Expanding efforts now to provide good-quality ICT training to low-skilled workers would help adapt to the changes in the labour market, while boosting productivity growth and reducing inequality. The proportion of under-qualified workers is one of the highest in OECD countries. Public and corporate spending on adult learning has declined, alongside participation in lifelong training. Additional support for job search, skills and apprenticeships was set out in July 2020. Further measures should prioritise schemes to develop digital skills and to improve access for low-wage, low-skilled workers. Better targeting of the apprenticeship system would also help.

Very low-income households are mostly those out of work or single-parent families, groups particularly affected by the crisis. The minimum wage has risen rapidly to one of the highest levels in the OECD. While past rises had a negligible impact on employment, a further sharp rise in the minimum wage now could have harmful impacts on youth and low-qualified workers. In-work benefits and tax credits are more effective tools to support low-income households as they can be targeted without harming employment.

The COVID-19 crisis may have exacerbated gender inequality. Prior to the crisis, the share of women in work had increased, but was still significantly lower than for men. The high share of women with a part-time job resulted in a large gender pay gap. Precarious female employment is often associated with child poverty. Increasing support for good-quality childcare would help women to take up full-time jobs.

The crisis provides an opportunity to encourage more environmentally-sustainable growth. The United Kingdom was in 2019 the first G7 country to legislate a target of zero net emissions by 2050. Despite more rapid falls in carbon emissions than in other OECD countries, the country is not on track to meet its target. The Plan for Jobs includes measures to increase the carbon efficiency of the public sector and social housing, together with subsidies to improve home insulation, complementing measures taken over the years. Further concrete actions are needed to reduce emissions in the transport sector. Policy coherence would be improved by equalising carbon pricing across sectors and fuels and by ending incentives to oil and gas field development, while taking action to address fuel poverty.

Once the recovery is firmly established, addressing the remaining structural deficit and putting the public debt-to-GDP ratio on a downward path should come to the fore. In responding to the COVID-19 crisis, the public debt-to-GDP ratio will reach a historically high level, despite low interest rates, and a structural deficit is likely to emerge. Population ageing is putting pressure on public finances. Indexing state pensions to average earnings rather than using the “triple lock” (the maximum of earning growth, inflation and 2.5%) would improve sustainability. Pension reforms should ensure that adequate support is provided to poorer pensioners. Once growth has firmed, broadening the tax base would support social objectives, such as health, while raising equity.

The current fiscal framework combines three targets and provides little effective medium-term guidance, particularly given the major changes to the wider economic and fiscal outlook. A review of the fiscal framework and a spending review are planned for the autumn. A more credible and stable medium-term framework would provide a better guide to policy, recognising the trade-off facing the United Kingdom, and other economies, in balancing responding to the immediate crisis whilst maintaining the sustainability of the public finances.