Executive Summary

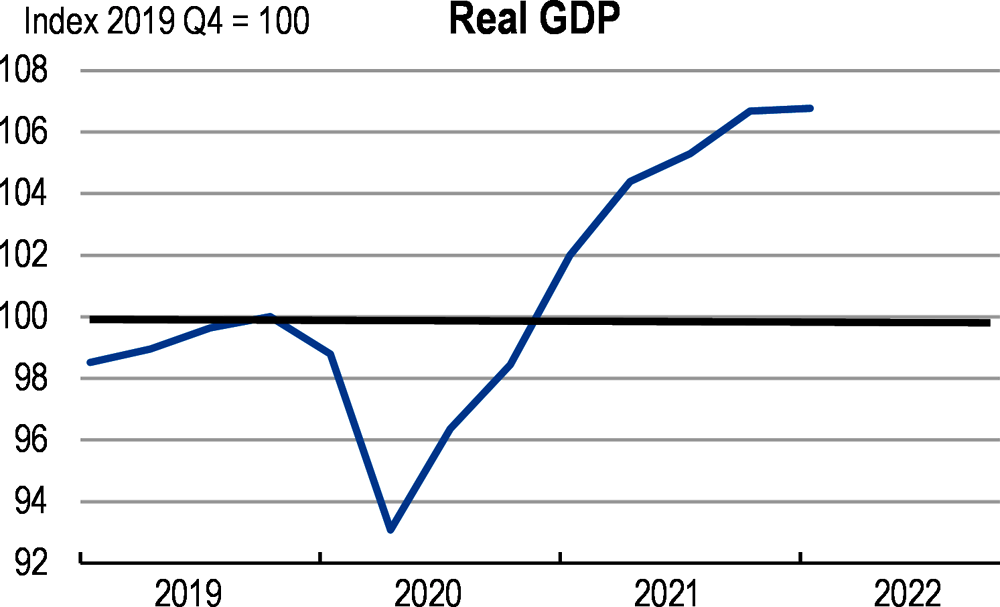

Estonia has withstood the pandemic shock better than its peers. Thanks to a large, timely and effective policy response to mitigate the COVID-19 shock, GDP contracted by only 2.7% in 2020, one of the softest contraction in Europe. An acute second wave at the beginning of 2021 did not put the recovery on hold, and GDP is now well above its pre-pandemic level (Figure 1).

OECD projections envisage this trend to slow, owing to the war in Ukraine. After an annual output growth of 8.2% in 2021, high inflation will hinder growth to 1.3% in 2022 and 1.8% in 2023 (Table 1). Private consumption will remain muted, as wages will grow less than inflation. The expected pick-up in EU fund absorption and future spending related to the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility will also underpin growth.

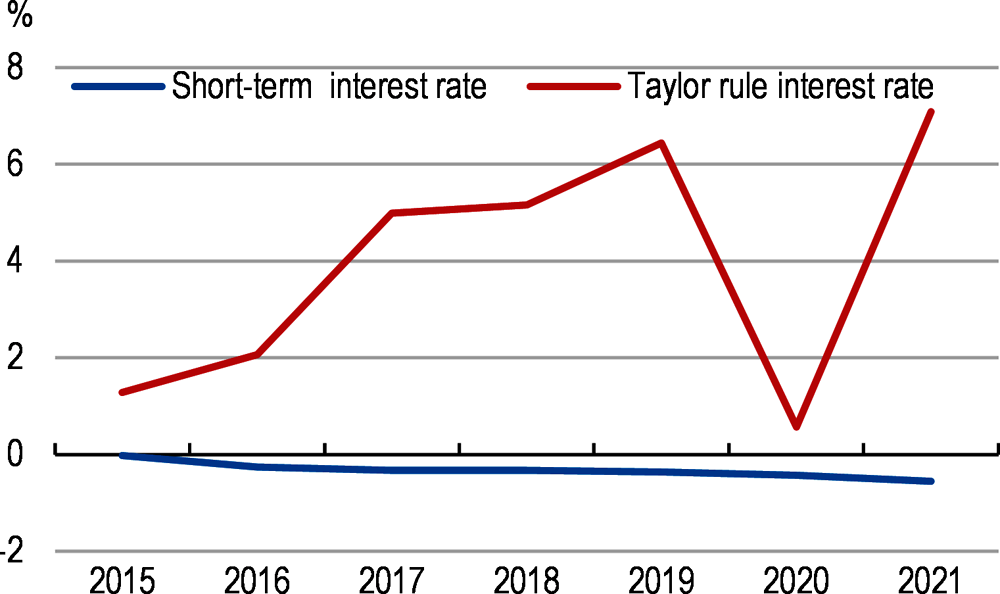

Inflation poses a risk to the outlook. Consumer price inflation has risen at double-digit rates since the end of 2021, and reached a record high of 19% year-on year in April. Upward price pressures came mainly from the cost of food and energy. Moreover, the stronger than anticipated recovery is also fuelled by the ECB accommodative monetary policy stance (Figure 2). Interest rates are too low to tame Estonia’s high inflation, thus making it important to tightly target fiscal spending to refugees and the most vulnerable, building defence capacity and investing in energy infrastructures, to avoid stoking inflationary pressures further. Funding from the European Union not affecting the budget balance will stimulate investment and domestic demand, which warrants a normalization of current spending. Macro-prudential policy should be adjusted given the rapid increase in housing market prices.

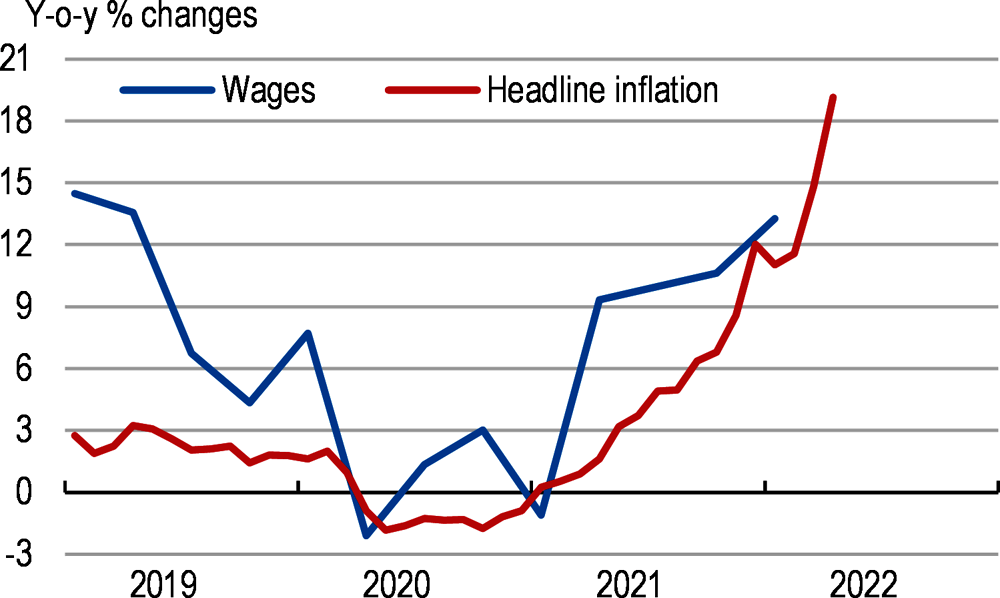

Labour shortages are rising, putting upward pressure on wages, inflation and competitiveness (Figure 3). The strong rebound in activity is amplifying the lack of suitable labour despite unemployment, underscoring entrenched skill mismatches. Pandemic-induced stricter border controls and administrative hurdles have also led to a lack of foreign workers to help filling the gap, notably in the digital and construction sectors.

Strengthening up-skilling and re-skilling programmes, in line with employers’ needs, will be key to address labour shortages and keep the economy on a strong path, while giving low-skilled and displaced workers the opportunity to benefit from the recovery. Better pathways from vocational education to higher levels of education would help to reduce the scarcity of skilled labour. The influx of refugees may also help, but it would be important to conduct a rapid assessment to identify the newly unemployed that could quickly join the labour market, and expand training and active labour market policies for the others.

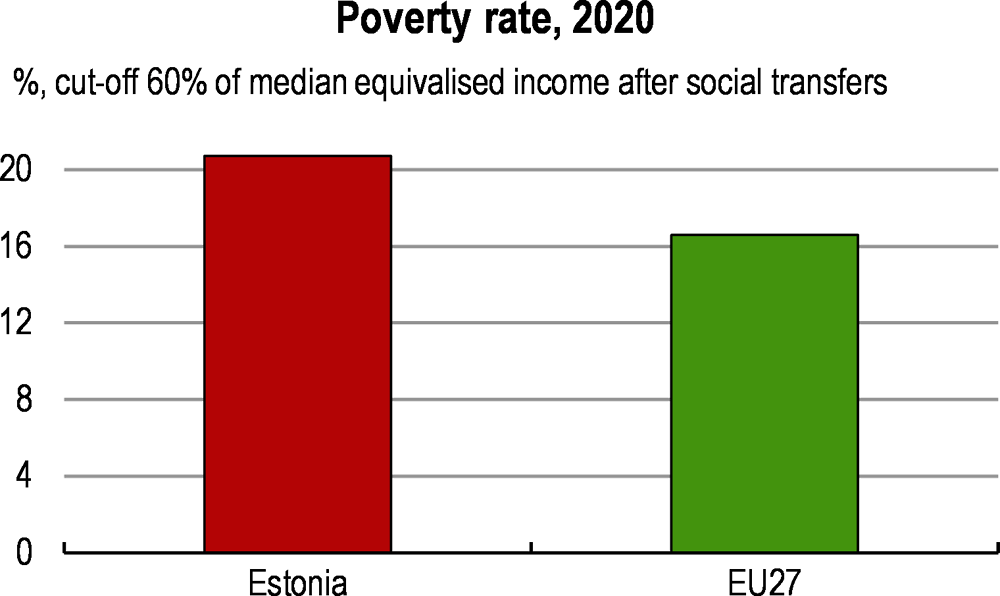

Poverty challenges have been made more acute by the pandemic and are now worsened by rising inflation. This highlights the importance of meeting the government´s goal of reducing relative poverty to 15% by 2023, from one of the highest levels in Europe (Figure 4).

Poverty is multi-faceted in Estonia. Several groups such as pensioners and single parents face a much higher risk of poverty than the general population. Moreover, one out of ten workers are living in a poor household. In the face of rapid developments in wages and inflation, minimum wage and basic pension are not keeping pace, and social partners should continue to discuss future increases.

There is room to make anti-poverty transfers more effective and better targeted. Introducing in-work benefits, which currently do not exist, could reduce poverty while making work pay more. Reducing employees’ social security contributions for low wage earners would also reduce poverty by strengthening employment, notably for young workers. Digital technologies could be used more intensively to target persons in need of support.

The gender pay gap is high. While Estonian women have high employment rates and outperform men in the education system, the gender pay gap remains one of the highest in the OECD, despite progress in recent years. The amendments reinforcing the implementation of the equal pay principle that were abolished in 2019 should be re-introduced.

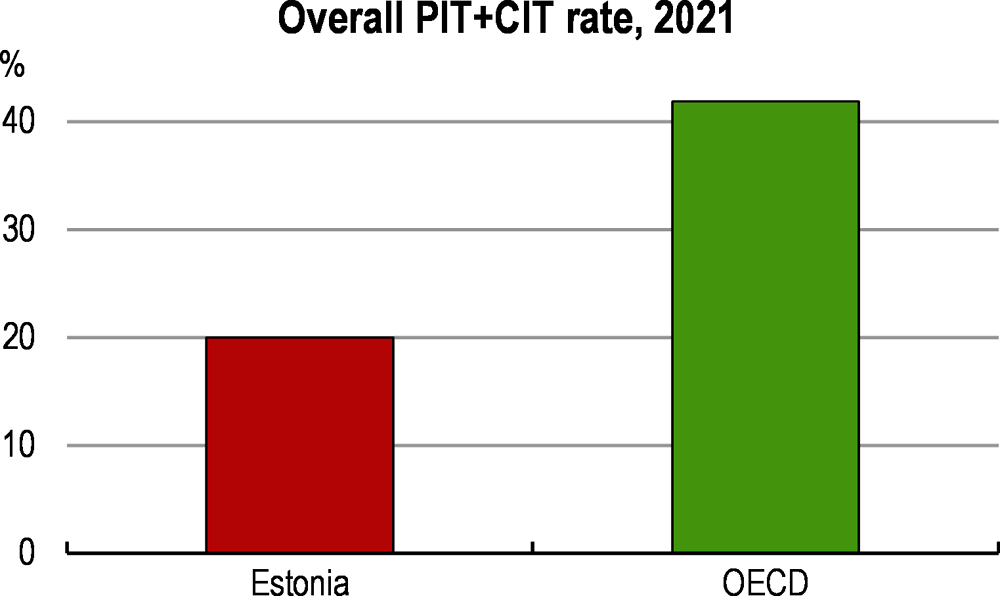

To prepare for future challenges – notably climate change and ageing – tax reform options that do not jeopardize the efficiency of the tax mix could be discussed. In the long term, population ageing will increase health and pension spending. Reducing carbon emissions and adapting to climate change will require more public investment. One option is to review the taxation of corporate income, which is among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 5). In particular, Estonia could examine the benefits obtained from the preferential 14% corporate tax regime granted to companies that distribute dividends regularly. This new regime should be evaluated to assess its merits regarding investment and entrepreneurship, compared to its cost. Furthermore, Estonia could discuss whether the new land valuation, to be carried out in 2022, is an opportunity to also evaluate the stock of housing and business properties and then expand the property tax base beyond land.

Public spending efficiency ensures the adequate use of tax revenue. In the healthcare sector, there is room to achieve better outcomes with similar expenditures. Pharmaceuticals fail to provide good value as the use of generic drugs remains lower than in other countries. Moreover, and despite Estonia being a front-runner in digital technologies, the secondary use of health data could be improved. Streamlining it to remodel services around patient needs could trigger sizeable efficiency gains.

Improving the selection, monitoring and decision-making of infrastructure projects will be key to deliver better value-for-money. Past projects funded by the European Union were too large to meet adequate cost-benefit objectives. The upcoming disbursement of large amounts of new EU funds makes it important to strengthen project selection , notably by systematically relying on cost-benefit analysis. Use of digital technologies and big data could help.

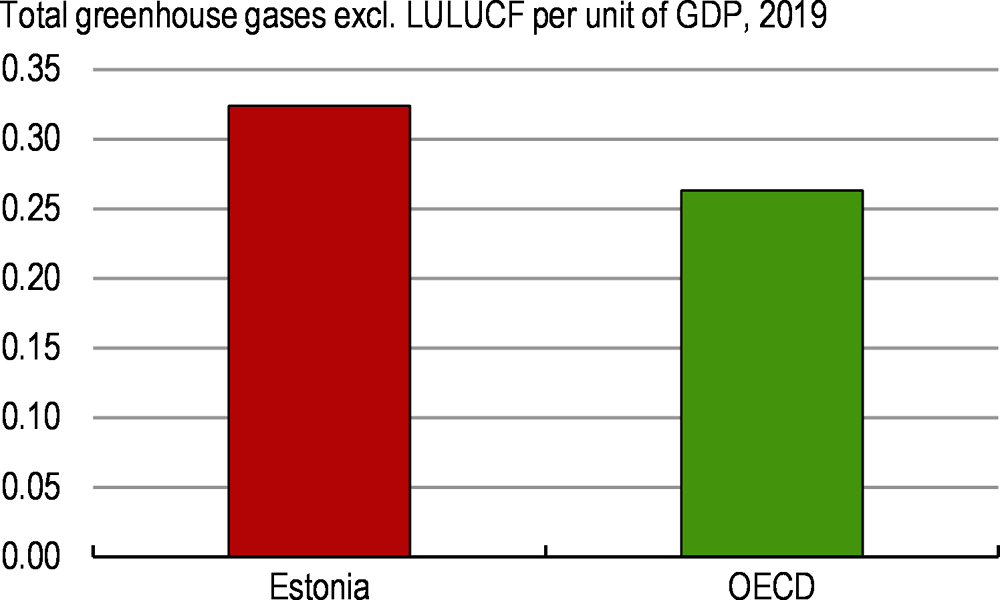

Estonia’s high GHG emissions have declined substantially, but further progress is required (Figure 6). Estonia has a relatively carbon intensive economy among OECD countries. Oil shale is prevalent in Estonia’s energy supply although the share of renewable energy has been consistently rising. Highly concentrated in the north-eastern region of Estonia, the oil shale industry is being gradually phased out. This transformation will have a significant economic and social impact on the Ida-Viru region, which the government seeks to mitigate with good governance, targeted active labour market policies, income support and strengthened regional development policies.

Estonia is aiming for net zero emissions by 2050 but the transition can have an adverse social impact. To achieve this will require a comprehensive and cost-effective approach. Decarbonisation will involve a large reallocation of capital and labour toward low-carbon activities, which will be disruptive for businesses, workers and consumers. Helping vulnerable groups will be essential in making these changes more acceptable and in avoiding resistance.

Emissions pricing is the most efficient climate policy. Carbon prices should be broad-based and equal across the economy and should be gradually increased in the medium-term. For example, transport emissions should be directly linked to carbon to encourage higher fuel efficiency while user-friendly and low carbon alternatives to private car use, such as public transport, should be developed further.

Innovation and investment will be key for transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Public investment in R&D, focused on more environment-related issues, should be increased and the deployment of innovative low-carbon technologies in the private sector should be supported. Providing a more certain regulatory and business environment for renewable energy would also stimulate investment. This should be accompanied by cost-effective investment in upgrading the energy infrastructure. To improve energy efficiency in buildings, more extensive support should be given for renovations.