1. Key policy insights

Following a robust recovery from the COVID-19 shock, Denmark’s GDP growth has slowed and the economy has been running at two speeds between domestic and specific international activities. Headline inflation has fallen, but underlying price pressures remain high. While the public finances are robust with a budget surplus and low public debt, population ageing poses long-term risks to the Danish social model as long-term care spending increases and the working-age population declines, calling for efficiency gains at the local level. Denmark has put in place ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and made significant strides in achieving efficient climate change mitigation policies. Further policy reforms to advance the green transition can help to reduce dependence on fossil fuel energy and achieve ambitious targets.

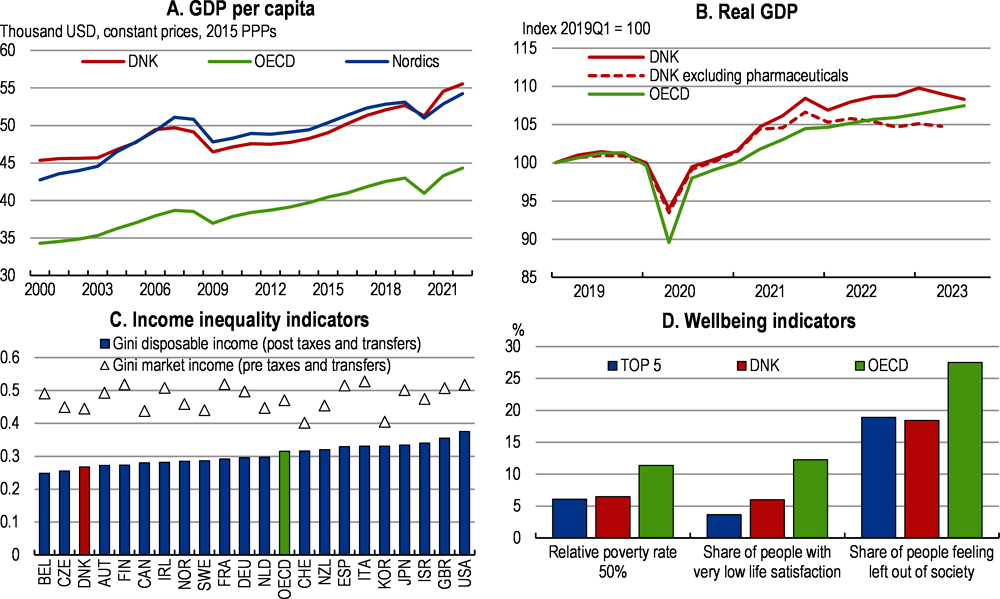

Denmark’s economy recovered swiftly from the COVID-19 crisis and proved resilient to disruptions following the energy crisis and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine in 2022, although growth is now slowing (Figure 1.1). Despite surging commodity prices and weaker activity in main trading partners, industrial growth has been strong, driven by a small number of high value activities and services have fully recovered from the pandemic. Living standards remain high. Employment reached a record level, including for groups that historically have had integration difficulties. Decisive and targeted policy responses contributed to this good performance, while keeping public finances sound. Policy initiatives contributed to preventing energy shortages by diversifying supply sources, encouraging savings, and supporting green investment.

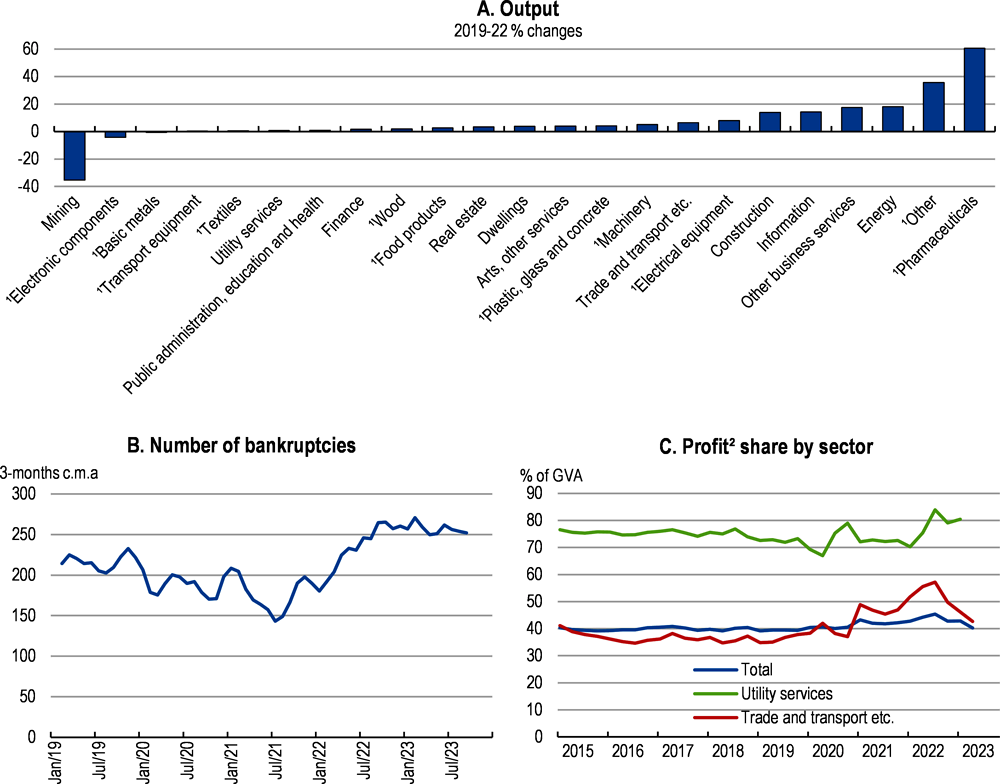

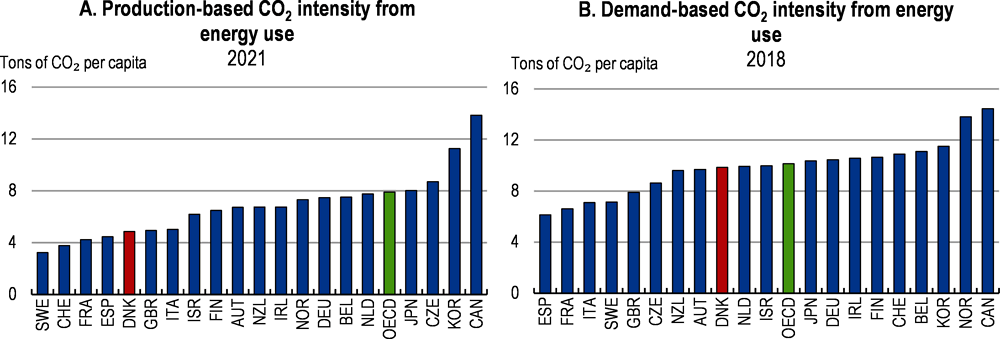

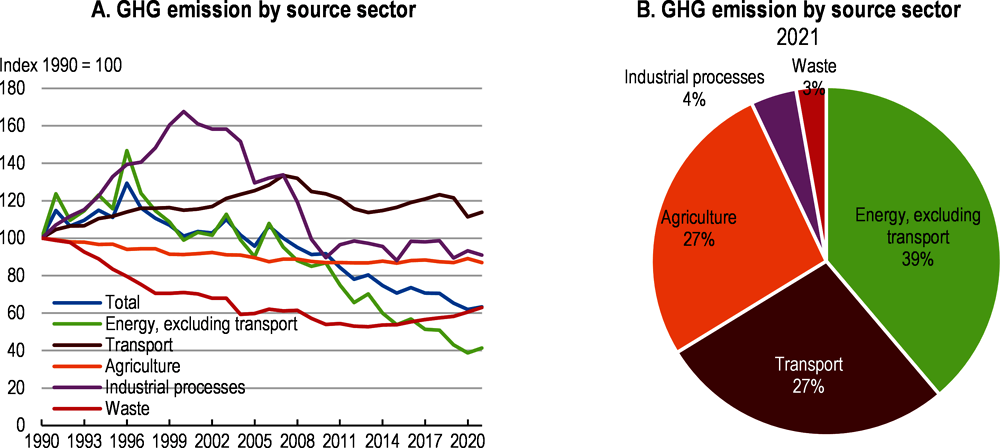

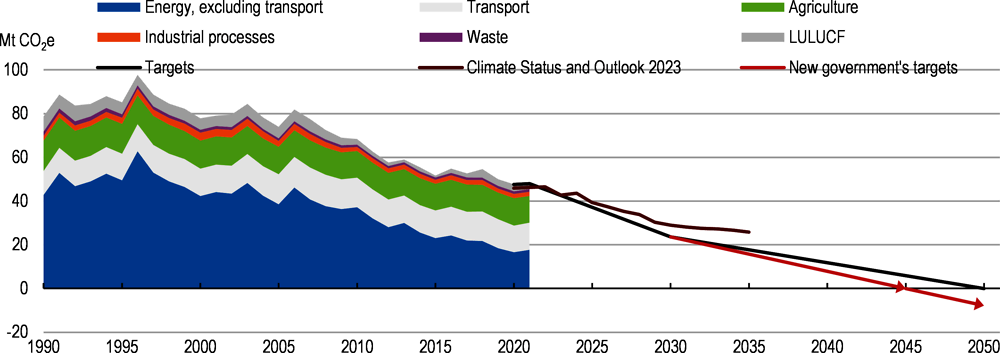

The current slowdown of the economy should reduce risks of overheating and dampen inflation, but it also masks large disparities. The Danish economy has been running at two speeds, with most of GDP growth driven by the pharmaceutical sector (Figure 1.1, Panel B). Productivity growth has been uneven across sectors and supported by multinational firms producing abroad. Ambitious targets for the decarbonisation of the economy have been set out, including reaching net neutrality by 2045. While Denmark made substantial progress in the design of efficient climate change mitigation policies, further action is needed to encourage technological advancements and greater emission reductions across sectors.

The new government programme includes a package of structural reforms to address these challenges and, in the tradition of consensus- and evidence-based policy making, expert commissions have been appointed on a range of priority areas (Box 1.1). Complementary reforms will be needed to sustain high living standards and progress. Against this background the main messages of the Survey are:

Long-term sustainability of public finances relies on future increases in effective retirement ages and lower use of early retirement schemes. Fiscal space is significant, but in the medium run, continuing to meet fiscal rules while maintaining high quality public services requires achieving savings and efficiency gains.

Adapting the labour market to demographic, technological and environmental changes entails reducing disincentives to work, changing the education and training systems to match evolving skills needs, and removing unnecessary obstacles to international recruitment in shortage areas.

While Denmark achieved significant strides in climate change mitigation, meeting ambitious targets and strengthening climate adaptation entails further policy action, with a particular focus on accelerating the deployment of green electricity production capacity and pricing agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

The “2030 plan” and past “Denmark can do more” agreements encompass a vast range of reforms and investment in priority areas, such as employment, health, education, defence and climate. DKK 32 billion (1.1% of GDP) and DKK 21.2 billion (0.8% of GDP) will be allocated to welfare services and the green transition by 2030 respectively. After a temporary rise in military support to Ukraine, spending on defence will be maintained at 2% of GDP. Some measures are part of the Recovery and Resilience Plan revised in November 2023, which entails DKK 12.1 billion in grants (0.5% of GDP) whose disbursement is conditioned on the achievement of 93 milestones and targets, mainly in the green, digital and heath fields. Expert groups were appointed to formulate policy recommendations including on the future of welfare institutions and elderly care, climate change policies in the agriculture sector, and the healthcare and education systems.

Raising labour supply

Policy measures since 2021 aimed at strengthening work incentives by restricting unemployment benefits for graduates, relaxing means-testing rules for pensioners, and easing international recruitment including by reducing the pay limit to recruit non-EU workers. Reforms of the personal income tax, cash assistance, student allowances, master’s programmes, and the abolishment of a public holiday are expected to increase participation and employment rates by 2030.

Fostering green investment and research

Favourable depreciation rules for green investment and generous tax credits for R&D spending were introduced in 2020 (accelerated depreciation, increased ceiling for depreciation, deduction for R&D investment to 130% with a DKK 50 million cap). Large investments on public infrastructure (DKK 106 billion, 4% of GDP) and R&D for the green transition (DKK 10.7 billion, 0.4% of GDP) are planned between 2022 and 2035. In 2022, around DKK 2.4 billion was dedicated to green public research (0.1% of GDP).

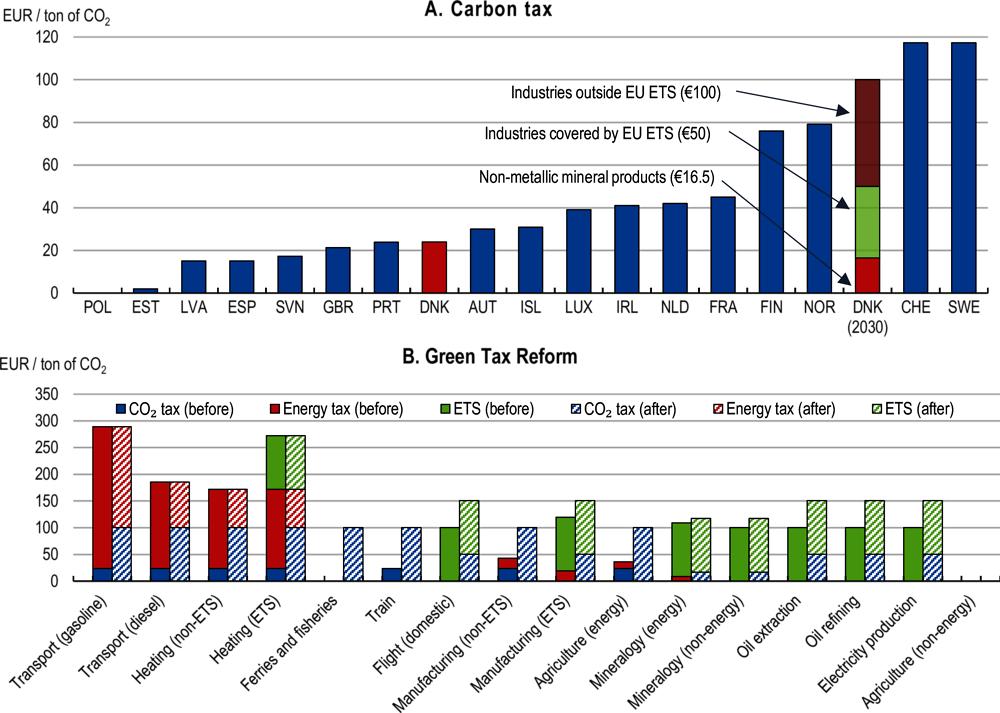

In 2022, a political agreement for increasing the carbon tax and expanding its scope in 2025 aimed to create a predictable framework for investment in emission mitigation for industry. Plans to introduce a kilometre-based and CO2 differentiated toll for trucks by 2025, a passenger tax on domestic air travel, accelerate investment in the energy transmission network and interconnection with neighbouring countries, and develop district heating while eliminating individual gas heating by 2035 have also been approved.

Improving public healthcare services

In 2022, a political agreement was reached to strengthen the integration of healthcare services at the local level and quality assurance, develop digital technologies and address shortages of GPs in some regions. An emergency plan of DKK 0.8 billion in 2023 and DKK 1 billion in 2024 was approved to reduce waiting lists and treatment backlogs in hospitals. The “2030 Plan” includes a DKK 5 billion health package and allocates DKK 3.25 billion to mental healthcare by 2030. Funds in the Recovery and Resilience Plan have been allocated to strengthen pharmaceutical preparedness and prevent shortages of critical drugs.

Source: Danish Government (2023a and 2023b), Danish Ministry of Finance (2023b).

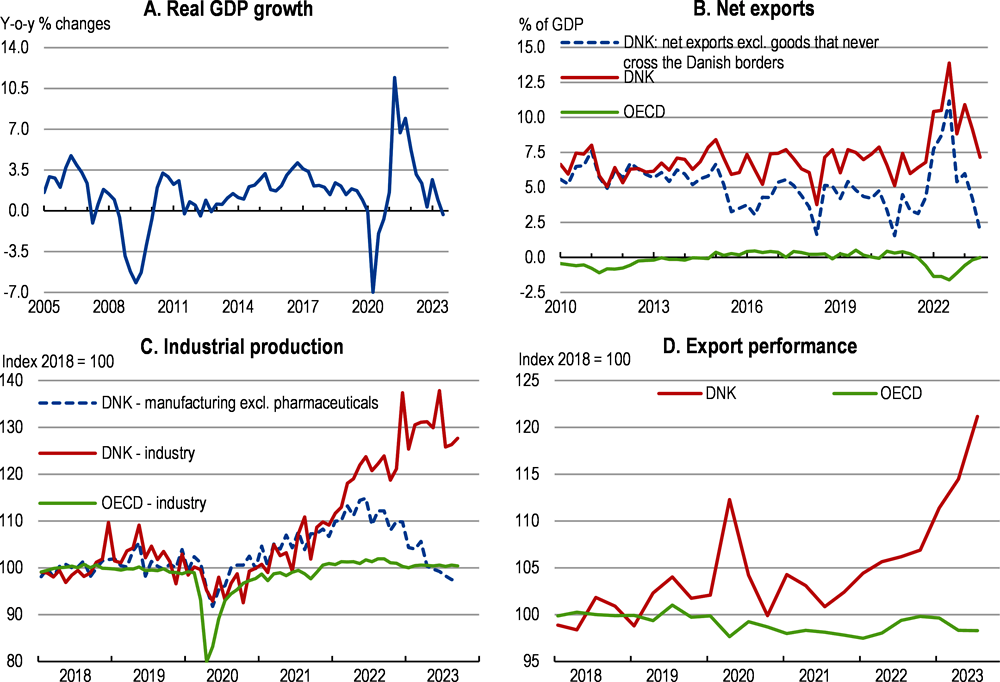

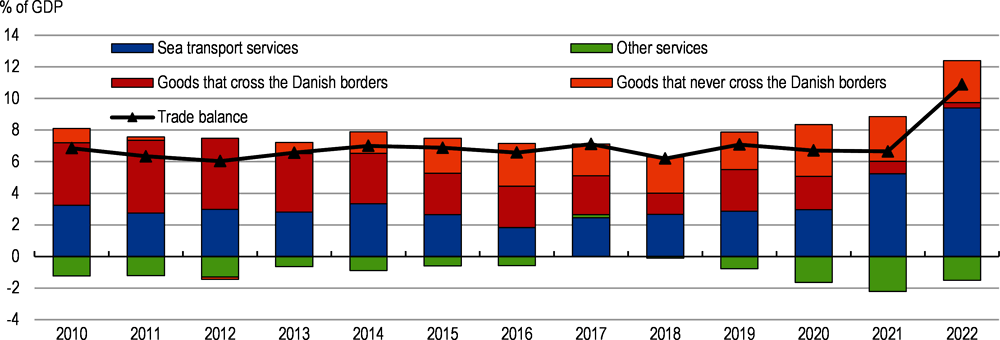

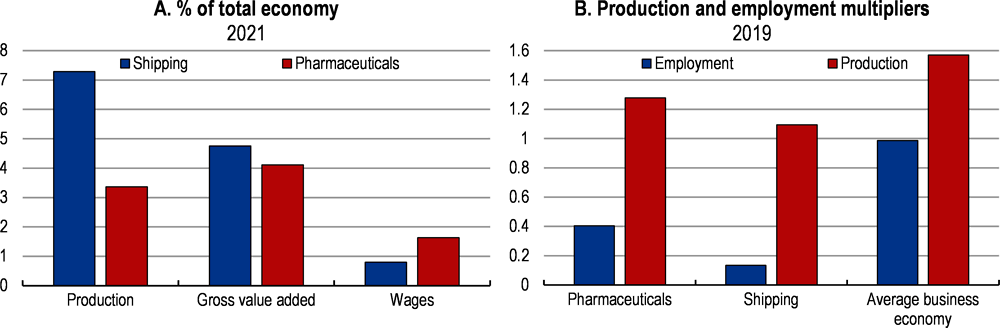

High inflation has weighed on economic activity

While Denmark’s GDP and trade outcomes have been relatively strong since 2020, growth has lost momentum and the economy has been running at two speeds over the past year (see Figure 1.1, Panel B, Figure 1.2, Panel A). Economic growth decelerated from 6.8% in 2021 to 2.7% in 2022 as large spikes in energy and food prices pushed up inflation and dampened domestic demand. Industrial production and export performance have increased significantly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis and are well above 2019 levels but have been mostly driven by buoyant activity in the maritime transport and pharmaceutical sectors (Figure 1.2, Panel B, C and D). Other manufacturing industries have been affected by the slowdown in international trade (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023a). In the first half of 2023, GDP was 0.5 per cent lower than in the same period in 2022 when excluding the pharmaceutical industry (Statistics Denmark, 2023). At the same time, the current account surplus reached 13.4% of GDP in 2022, among the highest in the OECD, due to strong performance by international sectors, notably of pharmaceuticals and shipping, and net income surpluses.

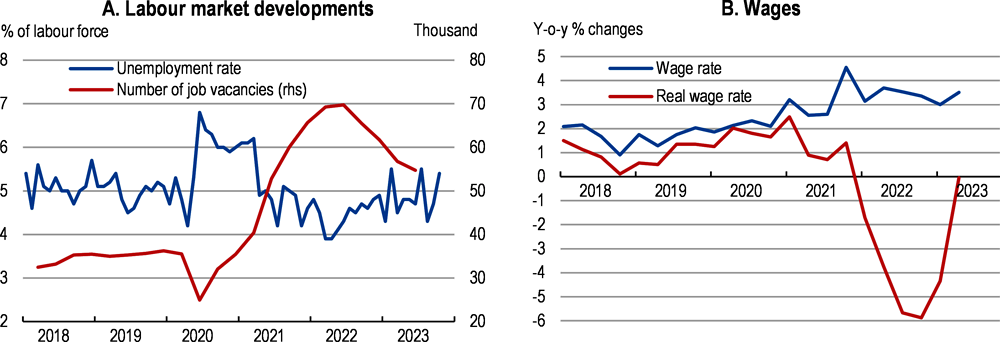

Employment growth has been strong, considering the recent slowdown in economic activity (Figure 1.3). After a short-lived drop in 2020, employment recovered fast, exceeding its pre-pandemic level by 3% in 2022. The unemployment rate fell from 6.4% at its peak in mid-2020 to 4.5%, and labour shortages were reported in almost all sectors of the economy (see Chapter 2). While tensions have eased since early 2023 and unemployment increased moderately, recruitment difficulties remain stronger than before the pandemic, with more than 30% of employers reporting labour shortages as a barrier to doing business in the construction and services sectors. Good labour market outcomes have coincided with a drop in productivity growth since 2022, when excluding Danish companies producing abroad (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023a).

Labour immigration has supported the strong expansion of employment and contributed to mitigating shortages. The number of international employees increased by 31% from December 2019 to May 2023 (Danish Ministry of Economics, 2023), due to improved employment rates of foreign-born residents, an acceleration of international recruitments and boosted by Ukrainian refugees since 2022 (see Chapter 2). Around 30 000 residence permits were attributed to Ukrainians under the special programme (Special Act) and around half of displaced adults from Ukraine were employed in mid-2023.

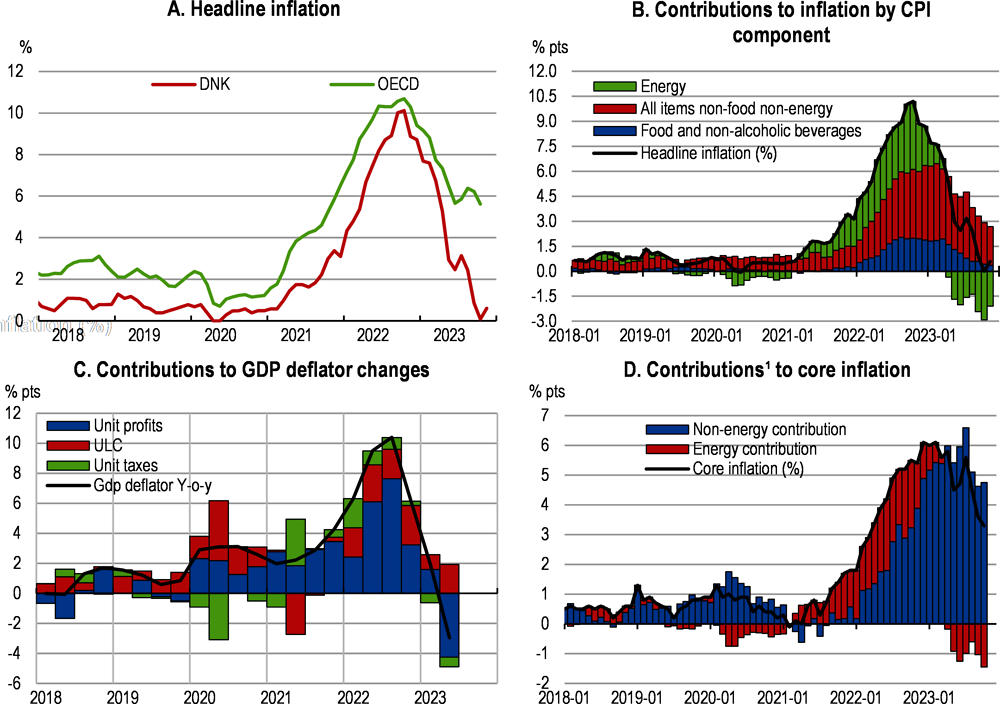

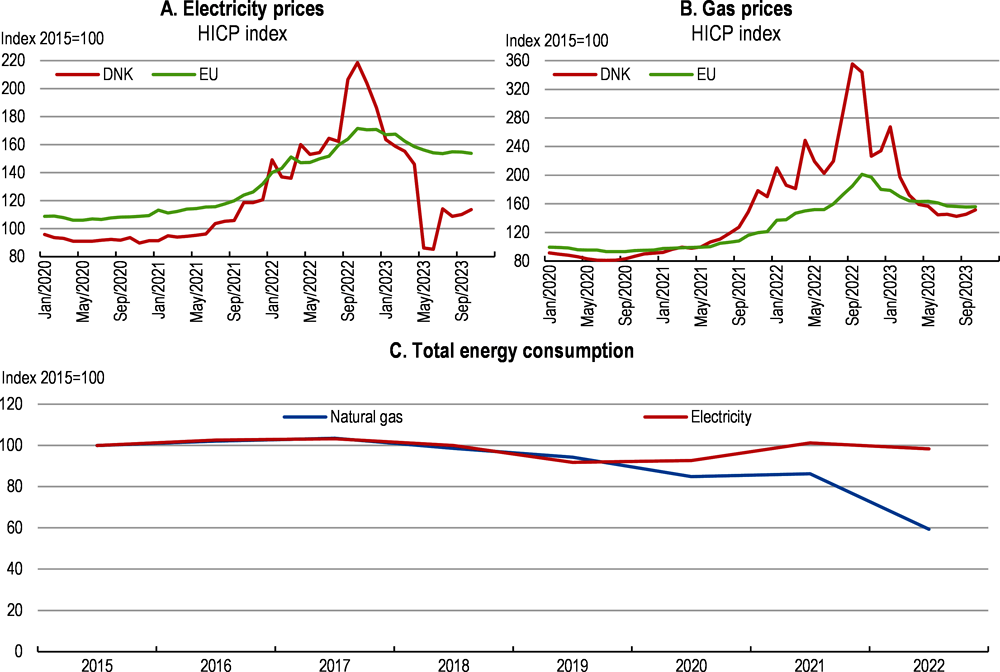

Inflation started to pick up during the post-pandemic recovery due to supply bottlenecks and strong demand (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023b; Harr and Spange, 2023). It was driven higher by soaring energy prices triggered by the war in Ukraine, leading to the highest inflation seen since the 1980s (Figure 1.4, Panels A and B). After reaching a peak of 10% in October 2022, headline inflation declined fast to 0.6% in November 2023, as commodity prices normalised. Food price growth has decelerated by more than 10 percentage points, while electricity and gas prices fell by around 45% and 50% respectively from their peaks in autumn 2022.

Core inflation peaked in February 2023 (6.7%) and has dropped since, as falling producer prices are being progressively passed to consumers. Lower energy prices have contributed by diminishing the cost of intermediate inputs and non-energy costs have started to recede in mid-2023 (Figure 1.4, Panel D). Still, at 3% in November, core inflation remained high, standing well above its pre-crisis level (around 1% in 2021). Sticky core inflation was mainly driven by inflation in services that has been running at around 5% since the first half of 2023. Unit labour costs have contributed to price growth but have remained contained (Figure 1.4, Panel C). By contrast, the contribution of profits has declined since the end of 2022 and was negative in the second quarter of 2023. Large increases in the GDP deflators were mainly driven by selected industries, such as transport, utilities, mining and quarrying and agriculture (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023a).

With a flexible wage bargaining system in the private sector characterised by general sector-level agreements with substantial room for firm-level negotiations, real wages declined significantly in 2022 as nominal wages picked up much less than inflation (see Figure 1.3, Panel B). In 2023, wage growth has remained limited, but has accelerated in the second half of the year. Following the latest collective agreements in Spring 2023, nominal wages are expected to increase by at least around 9-10% over the next two years, partly compensating for losses in purchasing power.

Electricity and gas prices were already among the highest in the EU due to elevated taxation, but almost doubled in a few months in 2022 (Figure 1.5). Despite a relatively low dependence on energy, energy imports, and gas compared to other EU countries, inflation was comparable to the level seen in the EU in 2022. Firms passed rising production costs quickly onto consumer prices (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022a). Relatively modest but appropriate measures were implemented to support households and firms affected by soaring energy prices (Box 1.2), while switching to alternative sources of energy supply. Measures were taken to reduce dependency on Russian natural gas, including the diversification of energy supply sources with the delivery of Norwegian gas via the new Baltic Pipe, the prolongation of fossil fuel fired power plants, and financial support to phase out gas for heating. Denmark should become a net exporter of gas from 2024 with the reopening of the Tyra gas field and the development of biogas production.

Policy action in response to the energy crisis helped to maintain a strong price signal, while partly protecting the most vulnerable. Together with the mild winter in 2022/23, and investment in energy efficiency, it contributed to reducing energy consumption (see Figure 1.5). At the same time, the untargeted cut of the electricity tax rate between January and June 2023 to the EU minimum, while electricity prices were already on a declining trend, weakened price incentives for energy savings. As stressed in the previous Economic Survey, excessive electricity taxation undermines the electrification of energy consumption (OECD, 2021a). While the electricity tax should be reduced to support green investment, it should be maintained at a level that encourages energy savings.

Support measures in response to surging energy prices have been modest by international comparison and are estimated to amount to around 0.4% of GDP (OECD, 2023a) .

Temporary measures targeted at households using gas for heating, families, and low-income pensioners accounted for around half of the total fiscal cost.

A means-tested DKK 6 000 tax-free heating cheque supported around 400 000 households among the hardest hit by the energy price surge in 2022. Households were eligible if their heating source was particularly exposed to rising energy prices. The total cost of the measure is estimated at around DKK 2.4 billion. Subsidies for the replacement of individual gas heating systems were also introduced and access to loans for energy savings investment facilitated.

Two tax-free cheques summing up to DKK 10 000 were allocated to low-income retirees in 2022 and 2023.

In 2023, the child benefit was increased by DKK 660 per child and DKK 300 million was allocated to low-income families as lump sum payments. Financial support was also provided to students receiving a disability allowance or a family allowance as single parents.

Measures to reduce the energy bill and encourage the electrification of energy consumption included a 6-month cut of the electricity tax to the EU minimum rate in 2023 for an estimated cost of DKK 3.5 billion, around a third of the total cost of the energy measures.

In 2022 and 2023, energy consumers could postpone the payment of their energy bill above a ceiling up to 5 years with a low interest rate. The government offered state guarantees for households' frozen debt to the energy companies and state loans for energy companies, as compensation, but the uptake has remained low.

In 2023, companies could postpone the payment of the withholding tax and labour market contributions. Small grocers and other energy-exposed food stores in small towns are eligible to subsidies to compensate for increased energy costs and for energy improvements up to DKK 100 000.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

Businesses coped well with the COVID-19 crisis and the rising production costs, but there are signs of weakening activity in the domestic economy. Only a few sectors saw output decline between 2019 and 2022 (Figure 1.6, Panel A) and employment growth was broad-based (see Chapter 2). At the same time, since 2022, industrial production growth was primarily sustained by the pharmaceutical sector whose production is mostly done abroad, highlighting the growing importance of multinational companies in exports and as a growth driver. The number of bankruptcies increased surpassing the pre-crisis level but fell in the first half of 2023 (Figure 1.6, Panel B). After a moderate increase, mostly sustained by rising energy and freight prices in transport and utilities, the share of profits in total value added has been returning to its long-term average since mid-2022 (Figure 1.6, Panel C).

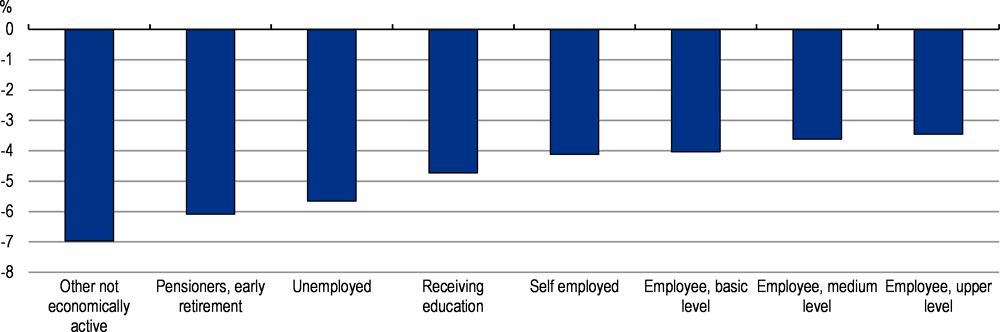

High inflation and low confidence have weighed on domestic demand. Despite the large pandemic-related excess savings, private consumption volumes dropped as purchasing power fell and savings increased. Real wages were down by 6% compared to a year earlier in the last quarter of 2022. Low-income households and out-of-work people have been the most affected by inflation (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023c; Figure 1.7). Income losses of social assistance recipients were large, as benefits are indexed to wage growth with a two-year delay. This indexation mechanism is generous and works as an automatic stabiliser when inflation is low but fails to protect social benefit recipients in a timely way during high inflationary episodes. A more rapid benefit indexation would have improved the protection of the poorest households compared to ad hoc measures, although this would still have implied some decline in living standards and would have added to inflationary pressures. Vulnerability to rising energy prices has also been higher for those unable to switch to cheaper sources (such as district heating) or to invest in energy savings. People living in rural areas and renters are more exposed, the former relying more on individual heating sources (as opposed to district heating) and the latter on property owners for energy efficiency investments (such as housing refurbishment, or changes in the heating system).

Uncertainty around the economic outlook remains high

Economic growth is projected to decelerate to 1.3% in 2023 and 1.2% 2024, the lowest annual rates since 2014 except 2020 (Table 1.1). High inflation, weak global demand, and tightening monetary policy have hit activity in 2023. A slow recovery will follow, with GDP growth reaching 1.5% in 2025. Lower energy prices will sustain demand from Denmark’s main trading partners and consumers. In line with the wage negotiations in spring 2023, real wage growth will resume and underpin households’ purchasing power. At the same time, stricter lending standards and high borrowing costs will weigh on investment. Construction activity is expected to decelerate on the back of weakening housing markets. Inflation is projected to recede from 7.7% in 2022 to 2.5% in 2025. Falling energy and food commodity prices will progressively be reflected in retail prices, but underlying inflation will remain modestly above normal levels with risks that it could prove more persistent.

Uncertainty around the outlook is high and mostly relates to trade prospects and future price developments (Table 1.2). Denmark is a small open economy exposed to trade developments in its main trading partners (Box 1.3). So far, demand for Danish exports has remained strong, but could be affected by growing restrictive trade policies in non-EU trading partners slowing international exchanges and freight activity. On the upside, an acceleration of green investment in Europe would sustain foreign demand for Danish environmental goods (notably wind turbines). Domestically, persistent tensions in the labour market could trigger stronger wage growth than suggested by the latest wage negotiations, slow the decline in inflation and boost activity. Still, as inflation expectations have remained well anchored, a wage-price spiral affecting macroeconomic stability is considered a tail risk. By contrast, employment and hours worked could fall faster than expected, notably in sectors where productivity has declined, leading to reduced domestic demand and activity.

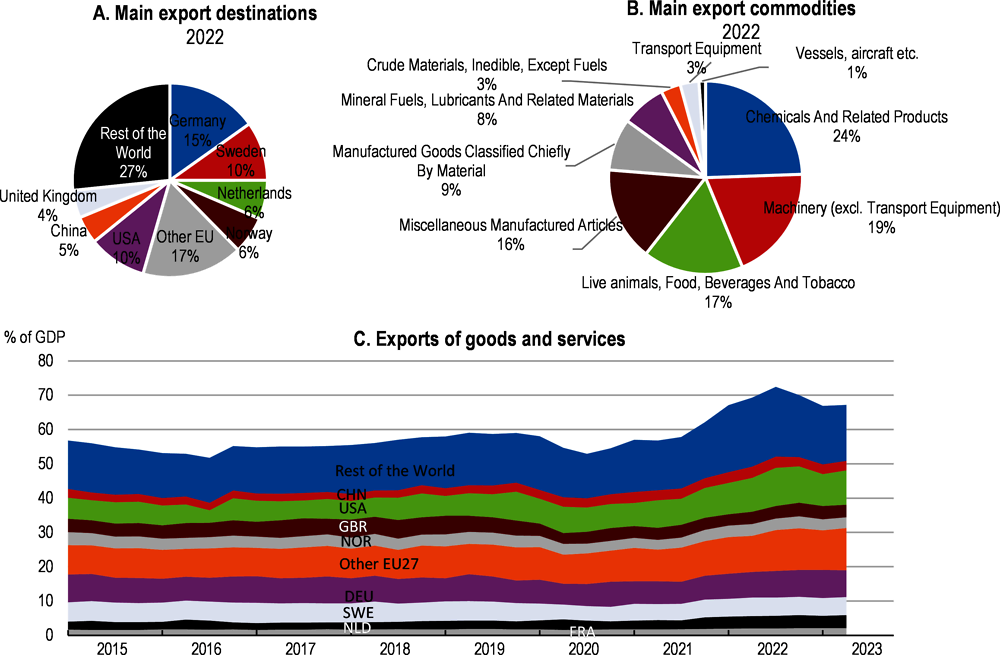

Denmark’s exports accounted for almost 70% of GDP in 2022, among the highest in the OECD. Exports are largely made up of goods with a relatively less elastic demand (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2020a). The main export industries include transport and shipping (including maritime transport, which accounts for around a fifth of total exports), chemical products (including pharmaceuticals), agriculture, green technologies, and machinery. Danish exports are primarily to Europe, but the share of trade to non-European countries has been growing in recent years, particularly to the US and China (Figure 1.8). Measured by foreign value added, China was the fifth largest supplier of inputs to Danish exports in 2020 and just over 3% of Danish employment in the private sector and 7% of export-related employment were linked to final Chinese demand in 2018 (Zhuang et al., 2023).

Tightening monetary policy has helped to manage strong demand

Monetary policy has tightened fast, with policy rates increasing from -0.6% in June 2022 to 3.60% in September 2023. The monetary policy stance is linked to ECB decisions since the Danish krone is pegged to the euro. The Danish central bank does not have an inflation target. Its primary mandate is to keep the Danish krone stable vis-à-vis the euro. Since 2022, the spread to the ECB policy rate widened by thirty basis points following appreciation pressures on the Danish krone. While the long-standing fixed-exchange regime remains the foundation of macroeconomic stability and reduces uncertainty arising from exchange rate volatility, it is important that domestic demand is managed to ensure macroeconomic stability. Inflation was largely in line with inflation in the euro area in 2022 but has dropped faster in the first half of 2023, suggesting the macroeconomic policy mix has been broadly appropriate. The central bank should continue to maintain the peg in line with its mandate and adjust interest rates as needed. Should monetary policy conditions step out of line with the Danish business cycle, fiscal and macroprudential policies will need to react.

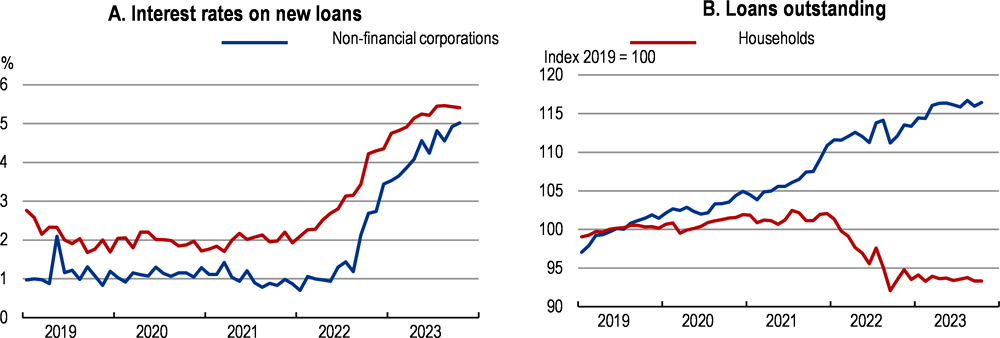

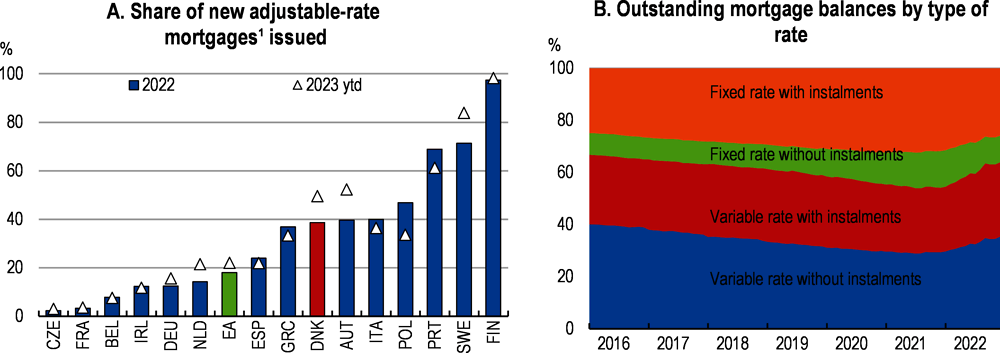

Monetary policy tightening has contributed to stabilising inflation. Rising borrowing costs and interest rate expenses have dampened domestic demand, especially construction. The interest rate pass-through on new loans has been relatively high in Denmark as mortgage loans are closely linked to capital market financing conditions due to strict matching rules between mortgage loans and the bonds that fund them. The pass-through from higher market rates to borrowers’ interest payments has been gradual, due to fixed interest rate periods on loans, with most of it expected to materialise in 2023 (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023d). By August 2023, more than half of homeowners with variable-rate mortgage loans have had their interest rates adjusted one or more times since 2022, with 27% of homeowners' mortgage debt adjusted within the last 12 months (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023e). The average interest rate on new business and household loans has increased significantly, contributing to the fall in the credit-to GDP ratio, and the significant deceleration of credit growth (Figure 1.9).

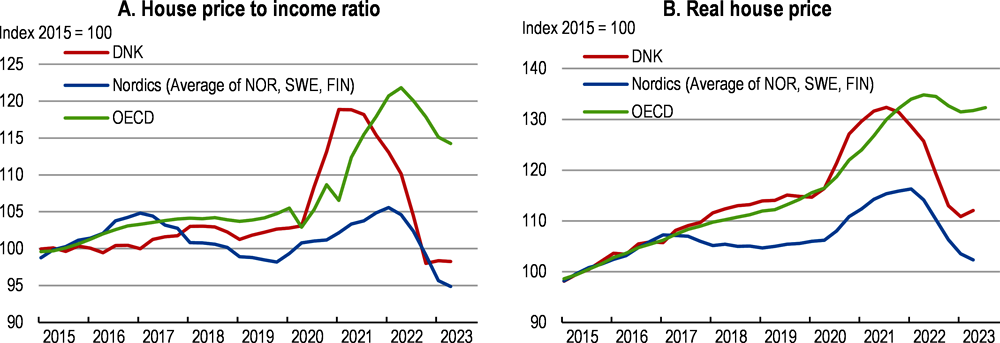

Together with reduced household purchasing power, rising interest rates have slowed housing market and commercial real estate activity significantly (Figure 1.10). House prices and transactions have improved since early 2023, but both the number of transactions and nominal prices have declined by almost 50% and 8% respectively between their peak in the first half of 2022 and the second quarter of 2023. Between 2020 and 2022, house price growth was the second highest in the Nordic region, exceeding income growth. The persistent supply-demand gap in the housing stock played a role, with insufficient supply particularly in major cities such as Copenhagen. The drop in house prices should mitigate the housing affordability issues in these main cities that has accentuated since 2020 (OECD, 2021a). At the same time, the drop in house prices reduces the capacity of homeowners with large mortgages to repay their debt when selling their house, although homeowners with fixed rate mortgages would benefit from some home equity protection due to the lower market value of their mortgage debt. Among homeowners who bought after 2021, one in ten could have debt exceeding home value by the end of 2023, with the effect strongest for first-time buyers (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022b).

Evolving financial risks call for strengthened supervision

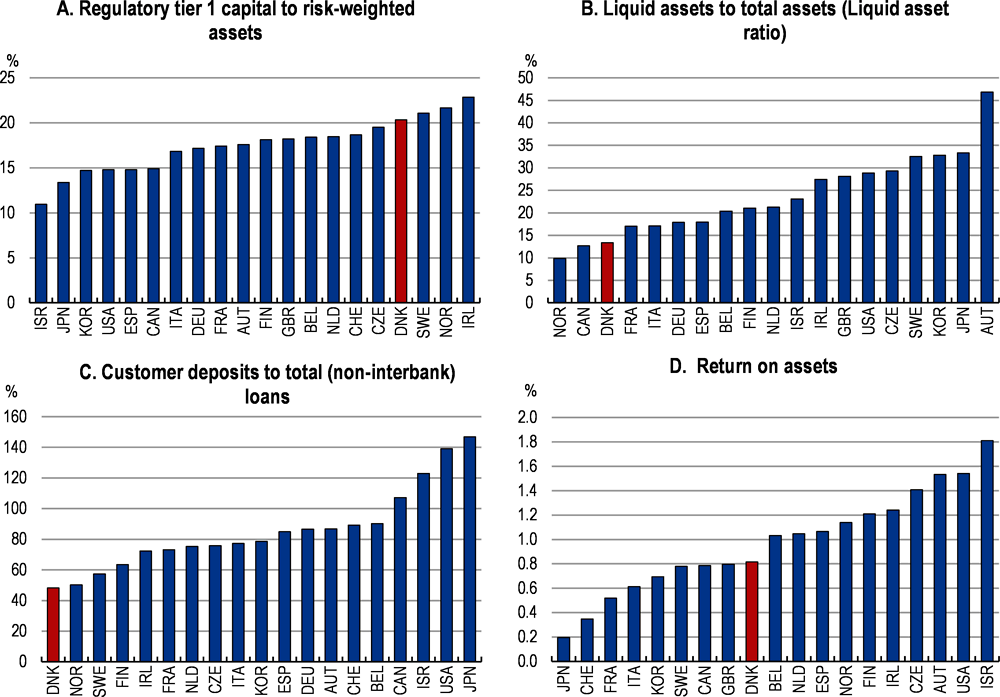

Fast increases in interest rates, slower growth, and financial market volatility have underlined risks to financial stability. Banks are in a good position to adjust, with capital significantly above regulatory requirements (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022b, Figure 1.11, Panel A). Danish banks had adequate liquidity buffers to handle the market turmoil in the US and Swiss banking sectors in early 2023 and to meet the increasing demand for liquidity. Recent stress tests suggest that banks are well prepared for a medium-to-severe recession, but a severe recession would leave some institutions close to breaching their capital buffer requirements (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022c). After a drop in 2022, profitability in the financial sector reached the OECD average in the first quarter of 2023 (Figure 1.11, Panel D). At the same time, the liquidity ratio has fallen since the beginning of 2023 and the Danish banking sector is the most highly leveraged in the OECD (Figure 1.11, Panel B and C). A narrow deposit base, heavy reliance on wholesale funding and shorter maturity of new issuances raises liquidity and rollover risks. Close supervision of banks’ assessments of risk and impairment charges, capital adequacy planning, and liquidity management is thus warranted. Participation in the European Banking Union could improve prudential supervision via wider and deeper cooperation and provide access to the Single Resolution Fund (Table 1.3).

While non-performing loans have remained at a low level (1% in first half of 2023), tighter financing conditions and high inflation have affected the debt service capacity of borrowers and increased the risk of business and personal failures for the most leveraged. Bank lending to the corporate sector rose by 20% over 2022, and credit growth to businesses has remained high, suggesting that corporate customers needed additional financing on an ongoing basis (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022b). Medium-sized banks are particularly exposed to corporate customers vulnerable to interest rate rises and falling property prices, including real estate companies and small businesses that account for 65% of their total corporate lending (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022c). Commercial real estate lending has accounted for the largest share of impairment charges in recent economic crises and is particularly at risk (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023d). Banks’ return requirement on such lending has increased, and commercial real estate activity has dropped in 2023, compared to a period of extremely high activity in 2021 and 2022, raising concerns for further price drops. Lower rental income and higher vacancy rates as activity slows would also reduce debt servicing capacity in this sector.

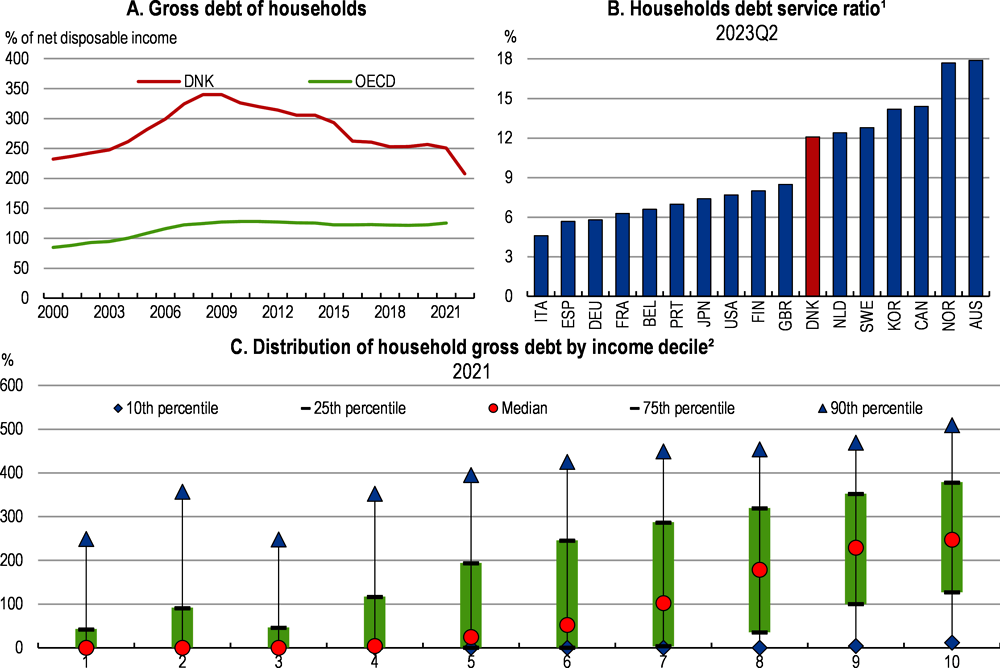

Despite declining in recent years, household gross debt continues to be among the highest across all OECD countries (Figure 1.12). This partly reflects the high level of mandatory pension savings and the unique Danish mortgage system, by which mortgage loans are funded through the issuance of bonds and priced at the capital market rate, which allows for cheaper mortgages. The elevated level of debt, together with the relatively large and increasing share of variable-rate mortgages, accentuates the impact of monetary policy on households’ balance sheets. Homeowners are increasingly repaying fixed-rate loans and refinancing existing mortgages by taking out variable-rate loans, on the expectation of declining interest rates in the years to come (Figure 1.13). Refinancing existing fixed-rate mortgages can reduce outstanding debt due to the reduction in bond prices underlying mortgages. At the same time, as interest rate rises pass through to variable mortgage rates, rising debt servicing costs can reduce disposable income and increase the risk of loan default. In August 2023, almost a sixth of homeowners’ mortgage debt received a new and higher interest rate, with the average rate on this new debt at 5.52%, including fees. This contributed to increasing the average interest rate on all mortgage debt to 3.1%, including fees, double the record low set in 2021. At the same time, because interest payments are deductible from personal income tax, the increase in interest rates will be partly compensated by higher deductions. For now, mortgage defaults are not rising, and credit institutions’ impairment rates remain low (European Commission, 2023). Loan defaults are projected to increase only moderately, as households’ capacity to repay their loans is estimated to be large (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2022b). Risks are also reduced by the distribution of debt, which is mostly held by high income earners and households with substantial asset holdings (Figure 1.12). The Danish central bank expects that 36,000 more households will be in deficit in 2023 compared to the estimated 85,000 households in 2021, with income being insufficient to cover modest living standards, pay fixed costs, and service debt (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2023d).

Denmark should take measures to reduce structural vulnerabilities in the housing market over time and consider strengthening macroprudential measures in the medium term once the housing market stabilises. Reforms of housing taxation should lower housing demand and prices in the short run (Box.1.4). A sizeable proportion of the new lending taken out as variable rate with deferred amortisation has a high loan-to-value (LTV) ratio above 60% (37%, Danish Systemic Risk Council, 2022). Consideration should be given as the housing market recovers to tightening LTV restrictions, such as subjecting new mortgages for highly indebted households to lower LTV limits than the current 95%. The Danish requirement is low relative to other Nordic countries, and most first-time buyers borrow up to the threshold. The Systemic Risk Council recommendation in June 2021 to limit access to interest-only loans for borrowers with LTV ratios above 60% has not been taken up. Complementary restrictions on debt-to-income can also ensure households’ ability to sufficiently service their debt at high valuations, with tighter limits on interest-only and floating rate mortgages as recommended in past Surveys (Table 1.3). Credit assessments of borrowers are based on their ability to service a mortgage loan at current interest rates. Introducing an interest rate stress test based on income as used by lenders in the United Kingdom and being considered in Canada should be envisaged given the use of floating-rate debt.

The property tax reform currently underway aims at restoring the link between the real estate taxation and property values without affecting the level of total revenues from recurrent taxes on immovable property. The new tax system replaces the long-standing nominal tax freeze (in place since 2002) with proportional taxation, maintaining a progressive element for the most valuable homes. The effective tax rate is estimated at 0.41% on property values up to 11.5 million DKK and 1.12% for values above (1% of all properties). New valuations will be updated every second year. After being approved in 2017 and delayed several times, the reform should become effective from January 2024.

A new automatic and complex valuation system based on a number of indicators has been developed and first estimates of property values were provided to households in autumn 2023. Due to the level of uncertainty as for the assessment of the property value, a principle of prudence has been implemented and property owners are taxed based on a value set 20% below the assessment. Preliminary assessments will be amended, with a final valuation expected in 2025.

In the medium run, property tax will rise in the largest urban areas, such as Copenhagen and Aarhus, where house prices have increased faster than in less densely populated areas. The reform will improve the fairness of property taxation as it should level out taxes relative to valuations and ultimately help to narrow the substantial price differences between small towns and large cities.

The new tax system affects the housing market and property prices. Homeowners who bought their property before the introduction of the new system will be entitled to a tax subsidy if the level of property tax increases following the reform. This subsidy is not available to new homeowners from 1 January 2024. As a result, market activity will likely intensify before the reform comes into place and could stagnate as the new taxes kick-in. Analysis suggests that apartment prices in the major cities will need to fall around 5-10% for the total costs (mortgage plus tax) to be unchanged versus the previous system (Nykredit, 2023). The subsidy helps to gain acceptance of a challenging reform and will effectively fade as its real value depletes over time. Nevertheless, it is generous and it will temporarily affect mobility and disadvantage first-time buyers should property prices not fully adjust to the changes in property tax levels.

The green transition poses a challenge to financial stability. Denmark is relatively exposed to climate risks, especially floods, and the implementation of drastic measures to achieve climate targets could result in capital shortfalls relative to requirements (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2020b). However, transparency about how banks manage these risks could be improved. Lack of regulatory standards hinder the ability to integrate these risks into the supervisory framework. Standardised regulatory guidance can lead to a significant increase in the disclosure of climate-related risks (Acosta-Smith et al., 2023). Denmark could take inspiration from the UK that became the first country to establish a mandatory financial sector disclosure regime in 2022 to improve the quantity and quality of climate-related reporting.

Fiscal policy needs to manage population ageing and the green transition

Fiscal policy is sound, but there are risks to sustainability in the longer term

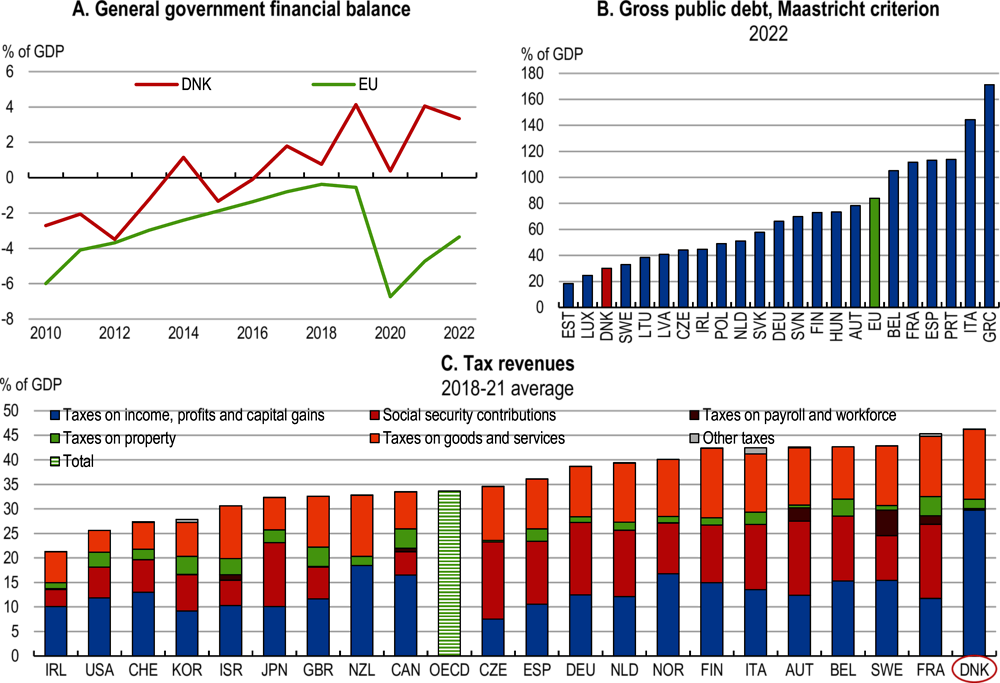

The public finances have proved robust and fiscal policy rightly adapted to fast-changing economic conditions over recent years. Gross public debt is around 30% of GDP and the government balance has been in a surplus since 2017 (Figure 1.14, Panels A and B). After a sharp deterioration due to the COVID-19 crisis, the headline budget surplus has been substantial, partly due to the fast economic recovery and high tax revenues on labour and capital income. A generous system of social support and public spending is financed through relatively high taxes (Figure 1.14, Panel C).

Fiscal policy has been prudent as the economy reached full employment and pressures on capacities increased. Support measures following the energy crisis in 2022 have been modest compared to other OECD countries (at around 0.4% of GDP, see Box 1.2). New public spending related to the energy crisis, defence and the acceleration of the green transition have been financed to a significant extent by restraining other spending lines. The impact of fiscal policy on GDP growth is estimated to be broadly neutral in 2024, partly because increased spending on defence will have a moderate impact on domestic activity and support measures will be fully phased out. Fiscal policy may need to be tightened if inflationary pressures do not recede as expected and persist relative to the euro area.

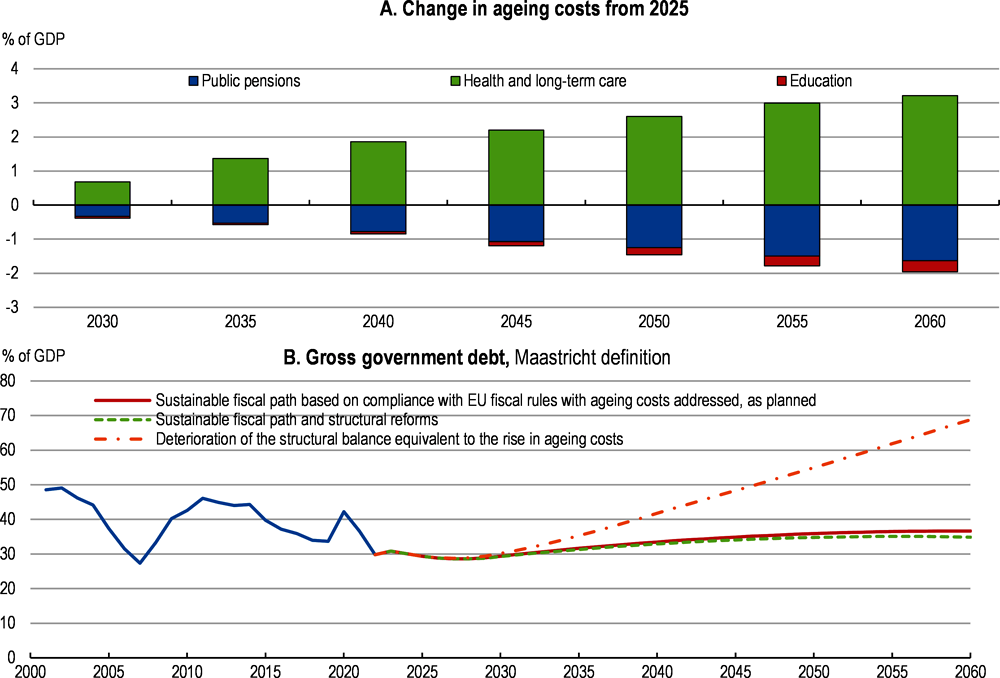

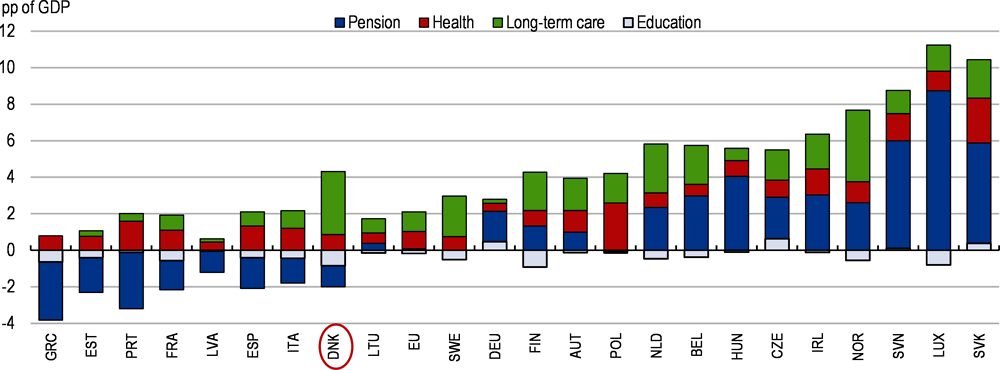

Denmark has a sound fiscal framework, including four-year expenditure ceilings, automatic sanctions for local governments in case of overspending and a structural deficit limit. In 2022, in line with past OECD recommendations, the Budget Law was revised to increase the structural deficit limit from 0.5% to 1% of GDP (Table 1.7). Relaxing the limit gives fiscal room to address demographic headwinds after 2030 and investment needs without affecting long-term fiscal sustainability. The government aims for a structural budget deficit at 0.5% of GDP by 2030. Following this approach and progressively converging to fiscal balance by 2060 would stabilise public debt at a low level (see Figure 1.15). Implementing structural measures in line with the recommendations of this Survey would modestly further reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. The impact on public finances is found to be relatively limited, due to the low level of debt, Denmark’s strong economic performance and because some recommended reforms are not included in the analysis (Box.1.5). However, while pension costs are set to fall in the coming decades due to past reforms and a further shift towards private provision that is already well-developed, net ageing costs are set to rise by around 1.1% of GDP by 2050, primarily due to higher health and long-term care costs. If these costs were allowed to rise without being offset by spending adjustments in other areas or higher tax revenues, debt would be on a sustained rising trend.

Projections from the Danish Ministry of Finance that include increasing ageing costs suggest the government fiscal target is achievable and point to room for extra spending or tax initiatives within the objective of a structural budget balance of -0.5% of GDP amounting to around 2% of GDP by 2030 (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2023a). However, these projections are based on a set of assumptions of significantly higher labour market participation of older workers following reforms and stable working hours. In addition, after 2030, the retirement of the baby boomer generation and the gradual indexation of the retirement age to life expectancy gains are projected to temporarily push the fiscal deficit above the 1% limit defined in the law for more than 10 years (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2023a).

Maintaining the generous social system while keeping the public finances on a sustainable path will be challenging. Costs related to demographic changes are expected to increase significantly and put pressure on the government budget (Figure 1.16). The population aged 75 and more is expected to increase by 25% by 2030, raising demand for long-term care services that are mostly provided and financed by municipalities. At 3.6% of GDP, spending on long-term care is already among the highest in the OECD after the Netherlands and Norway, reflecting the advanced development of formal care services and the high costs per person (de Biase and Dougherty, 2023).

This box summarises potential medium-term impacts of selected structural reforms included in this Survey on GDP (Table 1.4) and fiscal balance (Table 1.5). The quantification impacts are illustrative. The estimated fiscal effects include only the direct impact and exclude potential behavioural responses that might occur due to a policy change. While recommended reforms in this Survey have budget and GDP implications, not all can be quantified due to model limitations. The impact of the recommendations on early retirement schemes, education, competition enforcement, and environmental policies are not or only partially evaluated.

Amongst a large range of social services, municipalities must provide for long-term care to all citizens who need it for free. Increasing demand as the population ages, rising costs and limited room for productivity gains complicate the provision of high-quality services. Costs have already been reduced by limiting institutionalisation and offering individual rehabilitation and training to make the elderly more self-sufficient before granting home care. Nevertheless, some municipalities reported they had to cut budgets on some welfare services, especially in rural areas. This is primarily due to fast rising costs of specialised social services. Between 2018 and 2023, the gap between spending in this area and state compensation reached DKK 4.3 billion (KL, 2023). This reflects that municipalities have a responsibility to prioritise between sectors and services within the overall expenditure ceiling, based on local priorities and demands, and rising demand for public services does not automatically lead to an increase in the expenditure ceiling. Adjustments are made on an ad-hoc basis. To compensate cost pressures in the specialised social services sector, the government committed to a DKK 1.5 billion investment from 2024-2026.

Going forward, state grants to municipalities are set to adjust to demographic changes and a strong equalisation scheme helps to prevent disparities between municipalities. Additional funding will be needed to meet future demand if the provision of public services continue to grow in line with private consumption opportunities, a trend that coincides with citizens’ expectations (Beck et al., 2023; KL, 2022). The government plans to allocate DKK 32 billion (1.1% of GDP) to welfare services by 2030, including DKK 19 billion to adapt to demographic changes (Danish Ministry of Finance, 2023b). In the longer term, meeting growing demand will be more challenging as the fiscal space diminishes. Reducing the administrative burden on care workers and municipalities as planned by the government can free up resources. At the same time, the impact of deregulation on the quality of public services and discrepancies across municipalities must be monitored. Should further savings be needed, cutbacks or tariff ceilings on services provided by municipalities could be considered. By contrast, a major reform of the Danish welfare model that would consist of diversifying funding sources of long-term care by adjusting public support to the means of citizens for non-essential services as is done for instance in the Netherlands would avoid restricting the provision of public services.

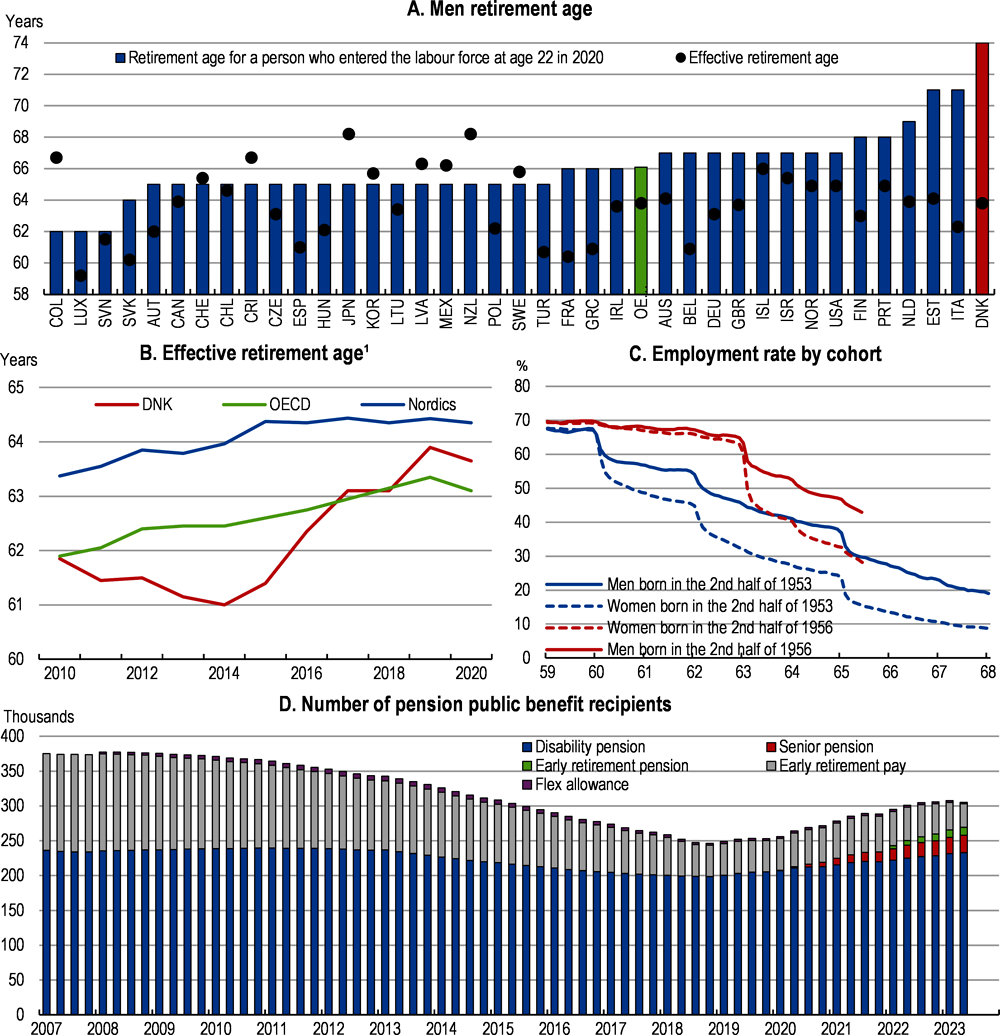

Despite the ageing of the population, public spending on pensions is projected to decline together with the share of pensioners relying on means-tested benefits as private pension schemes mature and working lives are prolonged (Box 1.6). The strict indexation of the legal retirement age to life expectancy gains is projected to push the legal retirement age 10 years beyond the current effective retirement rate (Figure 1.17, Panel A). The retirement age would also be the highest in the OECD, even when compared with OECD countries that already have implemented reforms to ensure the sustainability of their pension systems. However, as the retirement age increases, so does the risk of larger inflows into early retirement schemes open to those with long careers and disability benefits, especially for those in physically demanding occupations due to higher incidence of reduced work capacity and of chronic diseases. The effective retirement age has increased in line with the statutory retirement age so far, and employment rates of older workers have improved significantly (Figure 1.17, Panel B and C). At the same time, the number of disability pension recipients has been on a rising trend since 2018, partly due to the recent increase in the retirement age and the creation of two new schemes in 2021 and 2022 (Figure 1.17, Panel D, see Chapter 2). The Ministry of Finance assumes a broadly stable share of disability recipients from 2030 as the increased inflow in disability pensions due to higher retirement age is compensated by other factors, including the higher education level. This may underestimate the future costs of ageing for public finances should the share of people with low work capacity increases. Reforms could address barriers to prolong working lives, including for those with reduced work capacity, while maintaining adequate options to protect the more vulnerable (see Chapter 2).

The Danish pension system consists of a mix of pay-as-you-go and defined contribution schemes:

A tax financed and means-tested public pension, including a universal basic flat amount, a pension allowance subject to means-testing of non-labour income, and a supplementary benefit for the most disadvantaged.

A minor mandatory defined contribution scheme (ATP) for employees and those receiving temporary social security benefits.

Quasi-mandatory fully funded occupational schemes covering around 90% of full-time employees.

In 2021, public pensions accounted for around 70% of total gross pension payments and 84% of individuals older than 65 received means-tested pensions. As private pension schemes introduced in the 1990’s mature, public spending on pensions is projected to decline from around 9% of GDP in 2019 to 7% towards 2060 together with the share of pensioners relying on means-tested benefits. In 2019, total savings into labour market pension schemes and private pension plans were estimated at 120% and 29% of GDP, respectively. In 2021, the total sum of savings in occupational schemes (excluding ATP) has been valued at over DKK 4 000 billion, or approximately 1.6 times the national GDP.

Source: Ministry of Finance (2020) Pension Projection Exercise 2021, Country Fiche Denmark., OECD (2023) Pensions At A Glance: Country Profiles – Denmark

The climate transition will also have a significant impact on the public finances, which is not fully included in the long-term fiscal assessments. Projections from the Ministry of Finance estimate the effects of legislated climate policies on the budget, but not those of complementary measures needed to reach the national emission targets. They consider transitory revenues from the carbon tax, losses of excise duties on motor fuels as electric cars become more widespread and the cost of the Green Fund, a public financial reserve for green investment. Illustrative OECD projections suggest that the cost of the climate change transition and its impact on public finances will critically hinge on the type of abatement policies implemented (Guillemette et Château, 2023; OECD, 2021a). Fully recycling carbon-based revenue to reduce the tax burden and support affected households would offset some of the negative effects of the transition on activity and fiscal sustainability, while an extensive use of subsidies would push public debt up.

Identifying fiscal risks related to climate change, as done in the UK and in Germany would help to strengthen debt sustainability analysis (OECD, 2020a). One important risk is that the public sector might need to invest more than planned to reach the decarbonisation targets if policies aiming at fostering green investment by private stakeholders prove less effective than expected. As for adaptation, Denmark has a strong insurance system against natural disasters, but its fiscal cost, especially government liabilities, could be made more transparent (Radu, 2022). As part of the new adaptation strategy, a clear framework should be developed setting out where local and central governments are responsible for the cost of adaptation and establishing mechanisms to support local governments for which adaptation costs would be higher (Table 1.7).

Improving the efficiency of public spending

Achieving efficiency gains in the public sector should be part of the government’s strategy to meet deficit targets, given that room to increase tax revenues is limited (see Figure 1.14). Structural reforms envisaged in the government programme are projected to increase fiscal space to partly finance additional defence and welfare spending (Danish Government, 2023a). The government expects that the reforms, including the education reform and the abolition of a public holiday will raise hours worked, thereby the tax revenue. Efficiency gains are projected in public employment and administrative services (Table 1.6). However, uncertainty on the impact of the measures and the level of savings that can be achieved is high.

Savings are expected to come to a significant extent from local governments. Local governments account for around 60% of total public expenditure, the highest share in the OECD. Municipalities bear the responsibility and the financial risk for the provision of a large range of public services for which demand is set to rise significantly in the coming years, such as long-term care. They will come under increasing pressure due to rising costs that will need to be carefully managed. Municipalities have a high degree of autonomy in the allocation of funding but have annual spending limits combined with strict sanctions in case of overspending. Increasing budget flexibility by defining multiannual spending ceilings would allow them to better manage specific local needs (OECD, 2021a). The 2020 reform of the equalisation scheme reinforced redistribution across municipalities (Ornstrup, 2023). However, the system remains complex and may reduce incentives for a cost-efficient service provision (Mau Pedersen and Blom-Hansen, 2020). Regular reviews and thorough analysis of this system by an arm’s length body with input from municipalities would help to identify potential loopholes, drive future adjustments, and ultimately set up mechanisms rewarding efficiency gains in case high redistribution is found to weigh on performance.

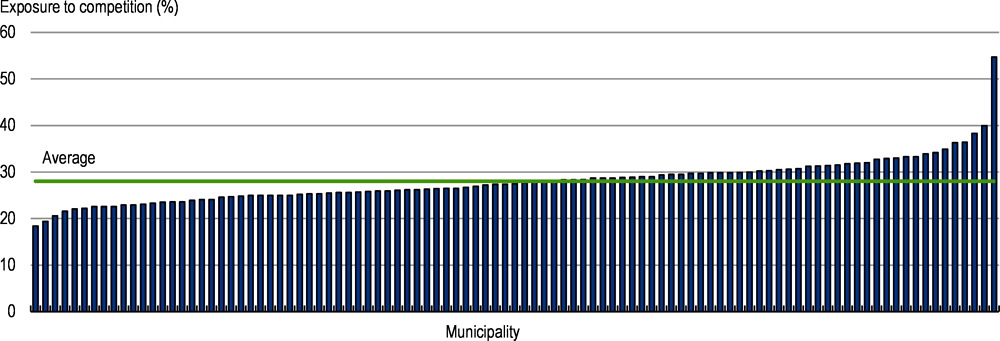

Opening more public services to competition could lead to cost savings, especially in technical areas (OECD, 2016). High competition, defined by a high number of participants in tenders, tend to reduce prices for public contracting authorities (Danish Competition Authority, 2023). Only 26% of public services go through a public tendering process, with strong discrepancies across municipalities (Figure 1.18; KL, 2023). The framework for public procurement is sound and governed by EU legislation. At the same time, implementation issues exist as illustrated by a relatively high number of cancelled tenders (one in four) and high transaction costs for small contracts and in some sectors (Danish Competition Authority, 2022). Rules could be made clearer and better applied by using more centralised procurement and professionalised procurement offices. Green procurement could also be developed by establishing strict criteria for the environmental sustainability of publicly procured goods and services like done in Germany (Table 1.7).

Inter-municipal cooperation could be strengthened to achieve efficiency gains (OECD, 2021f). A large share of municipalities has partnership arrangements for service delivery, especially in the field of healthcare and environment (KL, 2023). Expanding this practice to a broader range of local government and policy areas would help to reap economies of scale and scope. Cooperation mechanisms allow local governments to invest at the right scale, support the adoption of innovative services, and improve access to expertise, especially in remote locations that experience skills shortages (OECD, 2019b). While already used, benchmarking could be developed further to identify and share best practices. The “idea bank” - a database that provides the municipalities' inspiration to gain fiscal room – developed by KL, the interest group representing all municipal councils – is a first step. Tools to facilitate knowledge and data sharing across local government in the social and the employment areas are in place (the Social Economic Investment model and the “What works” database of the STAR employment agency). The scope of evaluation and dissemination mechanisms could be expanded (OECD, 2021b). In Australia, the central and local governments jointly produce a report on the performance of subnational service delivery. Establishing a Common Assessment Framework to assess performance like done in Germany by the Association of Local Government Management could be considered. An independent body could monitor the implementation of the regulatory reform, develop data-based evaluations, diffuse best practices across municipalities, and promote inter-municipal cooperation when relevant.

The government plans to save around DKK 3 billion (0.1% of GDP) by transforming job centres - the public bodies in charge of implementing active labour market policies and around DKK 3 billion by easing the regulatory burden for municipalities. The first measure is expected to cut the public employment services budget by more than a quarter. Some consolidation is warranted as spending on active labour market policies is remarkably high by OECD standards, especially when considering the low level of unemployment. As recommended in a previous Survey (OECD, 2019a), programmes for which evaluation does not conclude a positive impact or finds large crowding out effects should be phased out. At the same time, maintaining high-quality support to job seekers and limiting disparities in service provision across municipalities is necessary to address current and future labour market challenges (see Chapter 2). As for the second measure, significant increases, and differences in administrative costs per inhabitant across municipalities – which can vary from one to two - suggest there is room for savings (KL, 2023). However, past experiences such as the “free municipalities” programmes suggest the impact of deregulation on policy outcomes might be low (Arendt and Bolvig, 2016). Disparities in the quality of public services risk increasing with deregulation, calling for monitoring its impact across municipalities and regions.

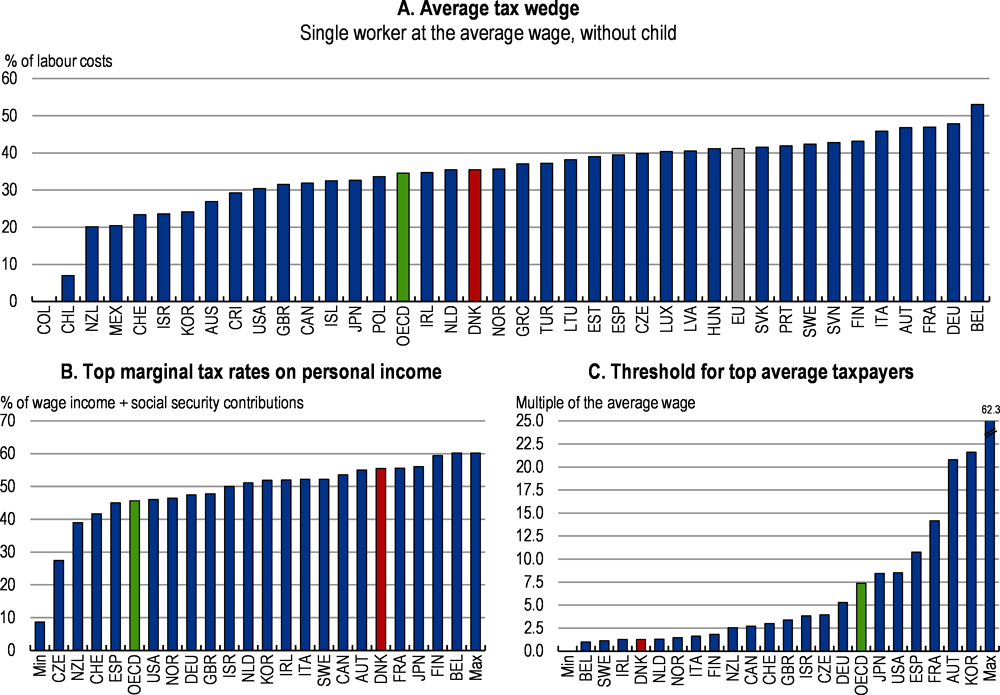

Reducing the tax burden on labour income

The Danish tax system is overall well-designed, but while the average tax wedge is close to the OECD average, labour income taxation is relatively high for upper-middle and high incomes and can discourage productive investment and longer working hours (Figure 1.19, Chapter 2). As stressed in past Economic Surveys, increasing immovable property taxation to reduce the tax burden on labour could raise Denmark’s economic potential (OECD, 2021a; Table 1.7). A reform initiated in 2023 will raise the earned income tax credit of the personal income tax, the top tax rate, and the income threshold at which the highest rate applies to DKK 2.5 million (more than five times the average wage). This would help to marginally reduce the marginal tax rates for most taxpayers, but room to increase financial incentives to work remains significant and the impact of these measures on tax optimisation should be monitored (see Chapter 2).

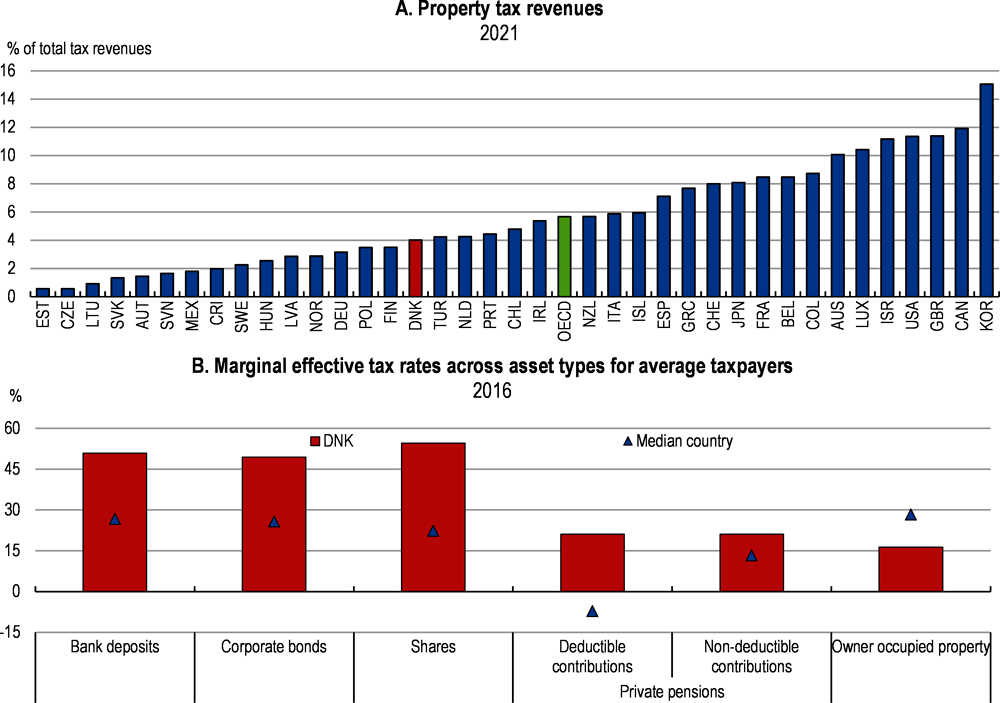

Reform of the tax system should strengthen tax neutrality across assets. The tax system unduly supports housing investment compared to other assets (Figure 1.20). Owner-occupied housing is taxed less than other assets, due to a generous tax relief for interest expenses and a tax exemption on capital gains (Millar-Powell, et al., 2022). This low property taxation and high interest deductibility are found to be capitalised into real house prices and to incentivise larger housing purchases and indebtedness (Gruber et al., 2021; Høj, Jørgensen and Schou, 2018). Empirical evidence also shows that mortgage interest relief does not raise homeownership rates or support new entrants into the housing market (OECD, 2022g; Gruber et al., 2021). As recommended in past Surveys, recurrent taxes on immovable property should be increased and interest rate deductibility on mortgage loans be reduced, for instance by gradually making the full amount of interest expenses subject to the lower rate of 25.5% (OECD, 2019a). This would ease housing demand and contribute to smoother housing cycles (Cournède, Sakha and Ziemann, 2019). These measures risk temporarily undermining the housing market and creating financial difficulties for some groups of households (OECD, 2022g). They should be implemented gradually, after the implementation of the property tax reform and once the housing market has stabilised. For credit-constrained households, taxation could be deferred until the owner sells the house. In addition, tax subsidies allocated to homeowners whose property tax will increase after the reform in 2024 should be progressively phased out in real terms to ensure equal treatment of taxpayers and support mobility (see Box.1.4). Besides, planned cuts to inheritance taxation of family-owned businesses should be avoided. This measure is regressive, distorts allocation of resources and risks locking in capital in poorly performing firms (OECD, 2019a).

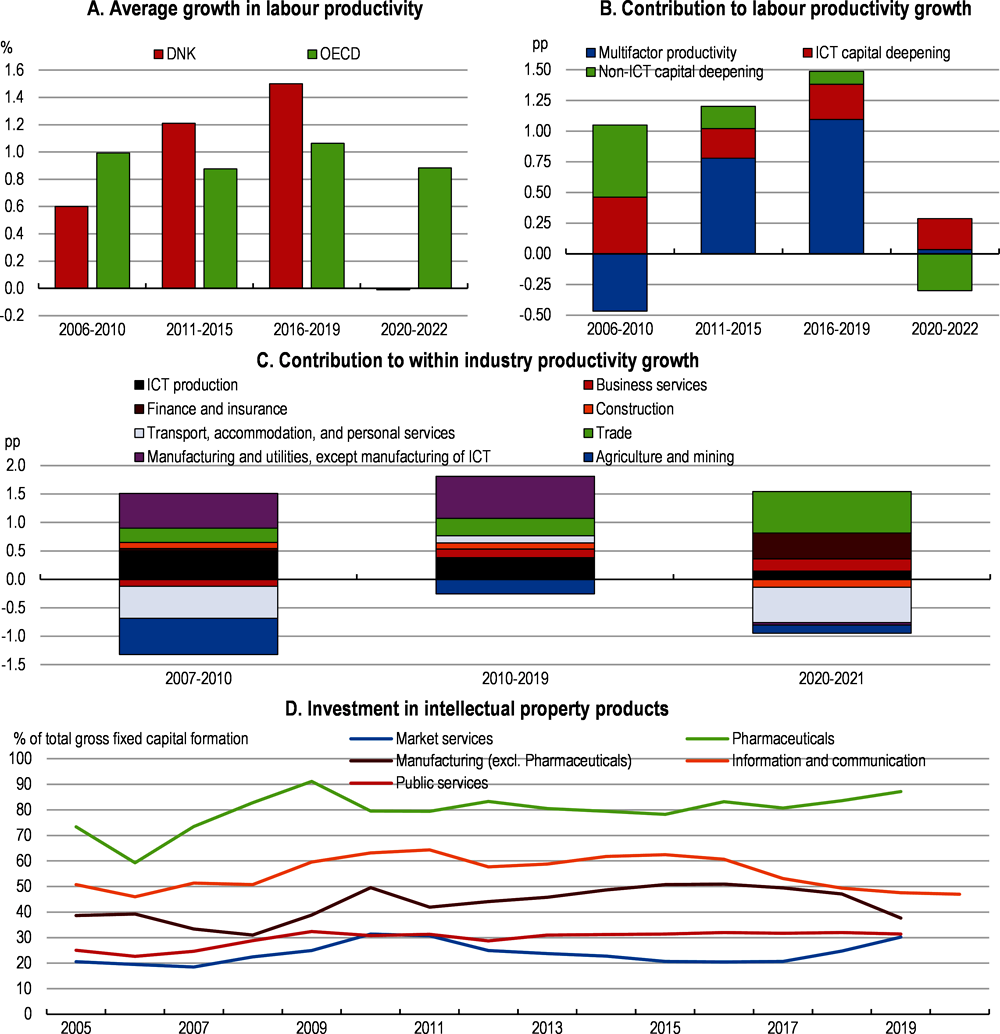

Productivity growth is key to maintain high living standards, especially in countries experiencing population ageing like Denmark. The country is among the most productive in the OECD and productivity growth has been relatively strong before the pandemic (Figure 1.21, Panel A). Productivity growth was driven by robust investment and substantial efficiency gains (Figure 1.21, Panel B). Investment in automation and product innovation in the manufacturing sector played a role (DORS, 2023b). Trade also sustained productivity gains with the growing weight of Danish multinational companies producing abroad and of large firms with capital intensive activities in the Danish economy (OECD, 2019a; Danish Ministry of Finance, 2022). While improving, multifactor productivity growth within services has remained lower than in manufacturing, as did investment in intangibles (Figure 1.21, Panels C and D). Since the pandemic, productivity growth has slowed and even dropped when excluding offshore production by Danish firms, mostly due to labour hoarding. This drop will likely mitigate as firms adjust the level of employment and working hours. However, subdued investment levels due to the tightening credit conditions may imply that productivity growth will stay low for longer.

Boosting the economic potential of a small open innovative economy

Addressing trade risks

Denmark is among the most open economies in the OECD with exports accounting for 70% of GDP in 2021. Denmark is strongly integrated in European and global value chains with imports playing a key role both in meeting domestic needs, but also as an input into exports. Looking through these effects, foreign final demand drives a third of domestic value added, above the OECD average, and almost half of private employment when considering the full value chain (OECD, 2022a). Denmark has a large and persistent current account surplus that has increased dramatically since 2020, partly due to a temporary spike in sea freight rates and profits in the pharmaceutical sector (Figure 1.22). Merchanting and processing activities by large Danish multinationals play a significant role.

The Danish export industry sells high value-added products, such as in pharmaceuticals and machinery, and is well positioned in the fast-changing trade environment thanks to a sound business environment, a competition-friendly regulatory framework, and a highly educated population. This should match some long-term trends in foreign demand, including the green transition (Box.1.7). Denmark is a global leader in clean technology and renewable energy sources, such as the production and export of wind turbines.

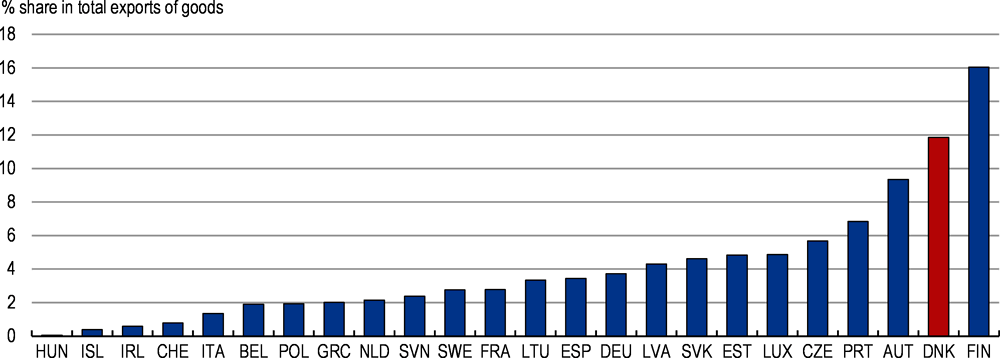

In 2020, Denmark had the second highest share of exports of environmental goods and services (goods and services aiming at the protection of the environment and the management of natural resources) among EU countries (almost 12% of total exports, Figure 1.23). It accounts for more than one-third of the world’s wind technology turbine sales. Other green exports have also been growing consistently, including district heating, bioenergy, and other energy technologies. In 2021, the Danish government launched an action plan as the first step to strengthen green exports and enhance joint initiatives between Danish businesses and business organisations. The government has doubled the export loan scheme of the Export and Investment Fund (EIFO) to DKK 50 billion and extended it to 2035.

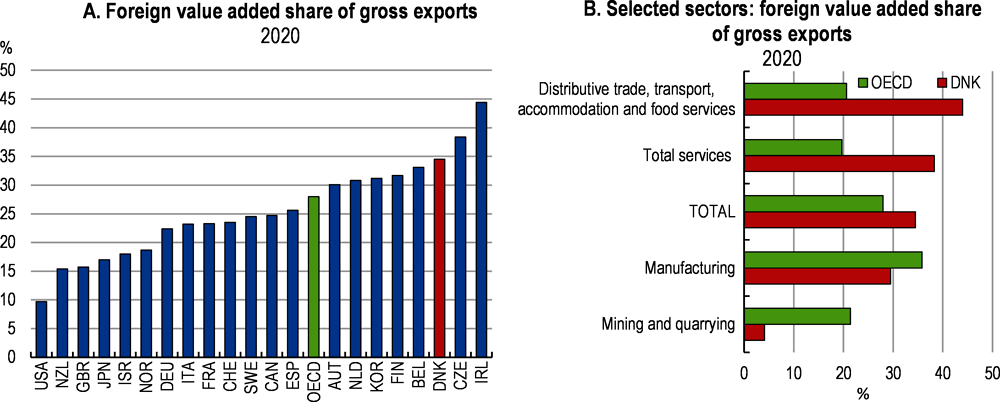

Trade openness entails large benefits but exposes the economy to international risks, including weakening global trade, geopolitical tensions, and supply chain distortions (Schwellnus et al., 2023). Denmark has one of the highest shares of foreign value-added content in exports in the OECD (Figure 1.24). Such deep integration in global value chains allows the business sector to specialise and integrate into parts of the value chain where it has comparative advantages, while bringing productivity and production price gains through economies of scale (Andrews, Gal and Witheridge, 2018). At the same time, this leaves Danish exporting firms exposed to trade restrictions that have been increasing over the last decade. 20% of the increase came from China (OECD, 2021c), whose importance in Denmark’s trade has grown significantly (see Box.1.7). Among others, restrictions could affect the shipping industry by reducing interregional trade and thus demand for transport services. Strategies should be considered to mitigate risks of supply disruptions, for instance when public and private interests are misaligned, or when private firms underestimate risks due to the lack of information. The government can take a more proactive role in co-ordinating data collection and analysing global value chains risks, including with ex-ante risk assessments and stress-testing to identify vulnerable supply chains as done in Australia and Switzerland. Other types of risk-reducing strategies can induce economic efficiency and welfare losses that should be carefully assessed (OECD, 2023i). Because the structure of import dependencies in strategic sectors is close with that of other EU countries, coordinating policy response at the EU level could bring significant benefits.

Like other OECD small open economies, concentration of Danish exports in few sectors increases the dependence on sector-specific trade policies, regulation abroad and shifts in foreign demand. Five international industrial groups accounted for 92% of the surplus in the balance of payments in 2018, and these large groups can be highly specialised, which increases exposure to international market changes (Christensen et al., 2020). Over 2002-2021, around 7% of cumulative Danish goods exports were derived from insulin, making the regulation of insulin markets abroad a major source of risks. Since 2021, economic growth has been largely driven by the pharmaceuticals and shipping industries, but spillovers to the Danish economy are limited (Box.1.8). Developing analytical tools to measure the economic contribution of these sectors like done for instance in Ireland (Timoney, 2023; Casey, 2023; Irish Central Statistics Office, 2023) would help to better assess Denmark’s position in the business cycle, productivity developments, and vulnerabilities.

The pharmaceutical and shipping industries are an important source of income to the Danish economy. In 2022, pharmaceuticals and shipping accounted for around 17% and 25% of total exports respectively, from about 7% and 18% in 2015. Over the last decade, shipping has grown 60% in registered tonnage, while the export of pharmaceutical products has more than tripled. 2021 and 2022 were, however, outstanding years for the shipping industry with strong demand for maritime transport services after the COVID-19 crisis and exceptionally high freight rates.

Direct positive ripple effects of these activities on other sectors of the economy have been limited, as suggested by the relatively low production and employment multipliers (Figure 1.25). Only around 40,000 and 35,000 Danish workers (1.3% and 1.1% of total employment) are employed in the shipping and the pharmaceutical industries. At the same time, both industries are highly capital and knowledge intensive, with around 40% of the workforce made up of high-skilled and highly educated workers.

Productivity spillovers from successful exporting multinationals to local firms can benefit the domestic economy (Di Ubaldo et al., 2018). High value-added activities contribute to strong productivity growth, including by pushing innovation and efficiency gains in other sectors and companies. However, large offshore trade reduces this potential positive impact in Denmark. Shipping vessels often do not sail in Danish waters, as they are mostly transporting goods between other countries. Similarly, the pharmaceutical industry has increasingly benefited from merchanting and processing activities, whereby exports are produced and sold abroad without crossing Danish territory. This reduces the pressure on domestic capacities, especially labour resources, but limits its benefits. Multinationals have a low propensity to reinvest earnings domestically. Earnings are often used to expand international activities, which raises national savings (IMF, 2022).

Offshore trading has a direct impact on the measurement of GDP and productivity. This elevates GDP growth since earned income from activity from abroad is classified as exports rather than investment income (OECD, 2019a). Fast rising merchanting and processing blur the line as to whether GDP and productivity gains reflect domestic activity and innovation, or whether they are being boosted by increasing measurement challenges.

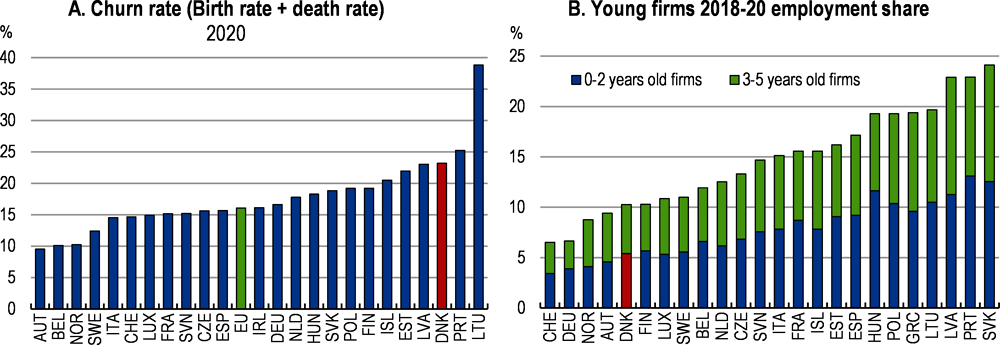

Encouraging small innovative firms to grow

Denmark’s entrepreneurial ecosystems generate a healthy pipeline of new and innovative businesses, but the weight of young firms in the economy has remained relatively low compared to other OECD small open countries (Figure 1.26). Public support has been extensive to address the lack of financial resources, which was one of the main barriers to growth identified by businesses (European Commission, 2020). The three state investment funds were merged to improve coherence and provide internationally competitive financing to Danish firms. While seed and growth investments have increased in recent years, activity on venture capital markets has dropped in 2022 (Danish Ministry of Business, 2023). Larger funding rounds and more “patient” capital are needed, especially in sectors where return on investment takes time (OECD, 2022b). Cluster organisations and industry-specific incubators could play a greater role by providing longer-term results-driven funding as in Norway. Pension funds could be allowed to increase their share of investments in unlisted Danish companies, as recommended in previous Economic Surveys (Table 1.8). Increasing the cap for carry-forward losses in the corporate tax system would also help young innovative but not yet profitable firms (IMF, 2023).

The efficiency of business supports could improve. These amounted to DKK 42 billion across more than two hundred different schemes in 2021. The latter should be streamlined and better targeted. The deferral of tax payments in 2023 and 2024 to alleviate liquidity constraints and smooth firms’ financial burden in response to the energy crisis was not targeted and should be kept limited in time to reduce deadweight losses and the risk of keeping non-viable firms afloat. Support for green entrepreneurship is fragmented, calling for a unified strategy with more coordination across programmes like the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, and data-based monitoring should be introduced like in Germany with the Green Start-up Monitor (OECD, 2022c).

In 2020, the tax allowance for R&D expenses increased from 101.5% to 130% with a DKK 50 million cap on qualifying expenditures. OECD empirical evidence suggests that this measure should boost innovative activities, especially in small companies and for projects that are already close to hitting the market (OECD, 2020b). Nevertheless, the R&D tax subsidy rate remains well below the OECD median and the increased deduction ended in 2023. The R&D tax incentive could be raised for R&D spending exceeding a pre-defined baseline amount, like it is done in the US, Korea, or Portugal, as it would avoid deadweight losses and benefit smaller firms (Table 1.8, OECD, 2019a). Business-based R&D spending is found to be larger in countries implementing either an incremental R&D tax incentive or a hybrid scheme (Koski and Fornaro, 2022). The positive effects of R&D subsidies would nevertheless need to be monitored to ensure value for money (DORS, 2023b), particularly in the light of the current concentration of R&D spending in a small number of firms.

Denmark is a highly innovative country, especially in the green area. Patents per million habitants increased by 73% between 2014 and 2019 and a fourth of patents were on environmental-related technologies in 2018, the highest share in the OECD. However, weak links of universities to the business ecosystem have hindered the commercialisation of research (OECD, 2022b). Developing cooperation between firms and universities would help the diffusion of innovation. In 2022, DKK 700 million was allocated to developing green research innovation partnerships. Cooperation could be facilitated by reforming the intellectual property right system and the operation of technology transfers offices (OECD, 2022b). Policy avenues include streamlining processes to establish collaborative research agreements, switching ownership of intellectual property from universities to teachers like done in Sweden, including entrepreneurship in the performance evaluation of teachers or in the public funding system of universities or providing targeted finance for spin offs.

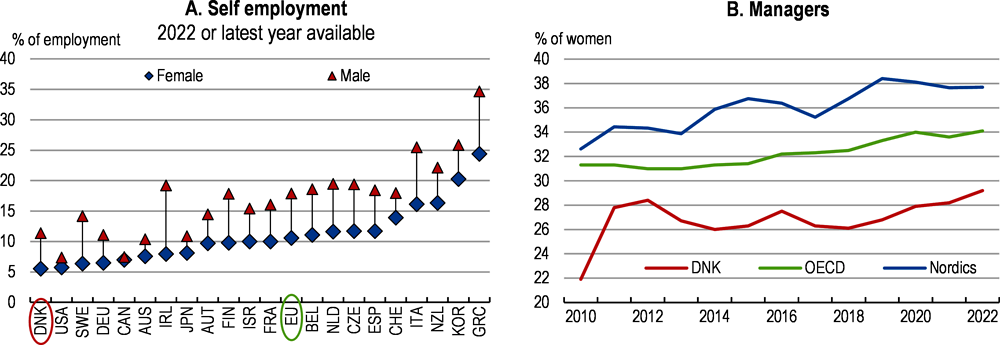

The entrepreneurial capability of women could be better used: men were more than twice as likely as women to be self-employed in Denmark in 2019, one of the highest gaps in the OECD (Figure 1.27, Panel A; OECD, 2021d). There would be almost 52 000 more entrepreneurs in Denmark if women started businesses at the same rate as core-age men all else equal (OECD/European Commission, 2021). Women remain underrepresented in studies that provide the skills and competences needed to launch or manage a business (Grünfeld et al., 2020). Denmark has provided little targeted responses to reduce the gap and has not taken a gender-specific approach to entrepreneurship policy (OECD, 2021d). Yet, mainstream programmes have a weaker impact in incentivising women’s entrepreneurship than programmes dedicated to women (OECD/EU, 2018).

Gender equality in management positions has also not improved significantly over the past decade (Figure 1.27, Panel B). Studies have shown that greater gender diversity in management leads to better, innovative idea generation, greater productivity, and better financial performance (OECD, 2023c). Since January 2023, public institutions and private companies are required to set targets for both the board of directors and senior management, as well as develop policies to promote a more equal gender balance in top management. Denmark could go further and consider introducing quotas as a transitional tool like in Norway or France (Box.1.9). At the same time, recent evidence suggests that quotas and targets may not be sufficient in and of themselves (Denis, 2022; EMPOWER: OECD, 2020). Policies addressing gender stereotypes, especially in the education system (see Chapter 2), and complementary measures should be developed, such as mentorship, networking and capacity-building actions, and active recruitment of women in leadership positions.

While Denmark has a target for female representation in top management, only 21.1% of board members were women in the companies subject to those targets. The European Union has recently passed a Directive to increase the share of women in boards, with a target of at least 40% women in non-executive board members at large companies before 2026. At the current pace of improvement, Denmark will not reach this goal until 2036.

Jurisdictions that have initiated mandatory quotas or voluntary targets for board composition in listed companies have achieved a greater level of board gender diversity than other jurisdictions. 14 OECD countries have introduced quotas, including Norway in 2005, France in 2010, Belgium in 2011, and were more likely to reach their targets than those using recommendations (Denis, 2022).

At the same time, the introduction of quotas led to unintended side effects in some countries (“golden skirt” effects with a small group of women serving on multiple boards, or an increase in family-related appointments). In addition, no strong link has been found between the share of women on boards and those in management positions. By contrast, alternative measures, such as diversity disclosure requirements in the United States helped to achieve substantial progress.

Source: OECD, 2022d

Adapting to the digital transition

Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to raise productivity growth by automating tasks, freeing up resources, and developing data-driven decisions. The adoption of digital technologies is well advanced in the private and public sectors in Denmark. The use of AI is widespread, including in small firms: more than one fifth have used the technology, one of the highest shares in Europe (Eurostat, 2023). However, integrating AI technologies in work processes requires expertise and resources, making its adoption challenging. In particular, shortages of IT and AI specialists can hamper the digital transition (see Chapter 2).

Regulatory and cybersecurity compliance can be difficult for firms with limited legal and technical resources. A large share of Danish firms, especially SMEs, are not prepared to comply with the EU directive Network and Information Security II to be transposed in October 2024, and one in every four SMEs has not put in place vital IT security precautions (Industriens fond, 2023; Danish Business Board, 2022). Denmark provides information and guidelines about cybersecurity, online tools for conducting risk assessments of a company's digital security and for testing its digital security level. A public-private partnership funded by the European Union to support cybersecurity in SMEs is in place and the “SME: digital initiative 2022-25” includes DKK 120 million in grants to SMEs for the purchase of consultancy, competence courses, and guidance on regulation. Participation in knowledge sharing networks could be encouraged further, for instance by engaging clusters to develop support to SMEs (OECD, 2022b).

Digitalisation poses new challenges to competition as specific features of digital markets favour the entrenchment of market power and winners-take-it-all dynamics. Persistent positions of dominance due to strong scale economies and network effects lower competitive pressures, with possible detrimental effects on innovation incentives, efficiency, and consumer welfare (Danish Competition Authority, 2020). This calls for new competition policy to promote entry and competition in digital markets (Nicoletti et al., 2023). Regulation in this area is mostly defined at the EU level to avoid fragmentation and safeguard the effective functioning of digital markets, amongst others. Nevertheless, the Danish Competition and Consumer Authority has rightly allocated ample resources for digital competition enforcement, including by establishing a Digital Markets Unit.

Further adjustments of national regulation can improve the effectiveness of competition law in the digital sectors, including adapting merger control regimes as in Germany, Austria, Norway, and Sweden for instance, or allowing for market investigations like in the UK (KST, 2020; OECD, 2022e). As envisaged since 2021, the Competition Authority should be allowed to control mergers that could potentially distort competition, even when below turnover thresholds for notifications of mergers, and have more power to impose remedies if competition issues are identified. Major actors in the digital sectors should also be asked to declare future acquisitions plans. The system for evaluating the impact of regulation on competition can better keep up with the digital transition and other structural transformation of the economy by introducing an oversight function that allows for returning proposed rules for which impact assessments are considered inadequate and a continued monitoring of the regulation impact on fast evolving markets (Table 1.8).

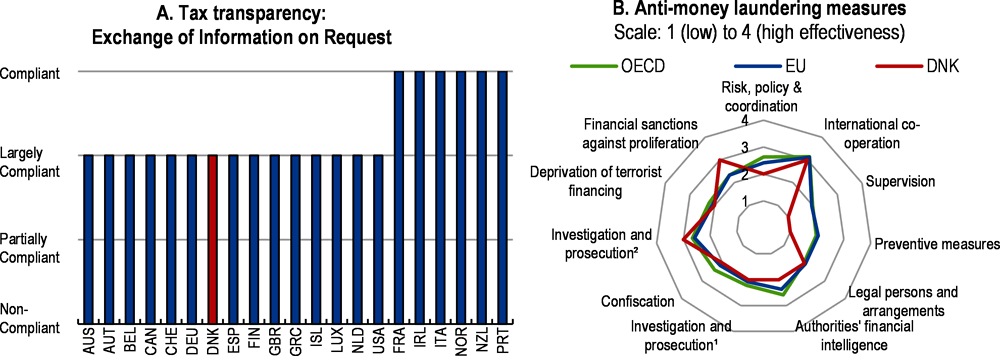

Addressing corruption and money laundering risks

In 2018, large-scale money laundering in the Estonian branch of Denmark’s largest bank highlighted weaknesses in the Danish anti-money laundering framework. Reforms in this area have intensified over the past five years (Danish Tax Agency, 2022). The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (DFSA) adopted a new institutional risk assessment model in 2021 and is developing a new supervisory strategy. Compliance with the FATF’s technical recommendations has improved (FATF, 2021). Further strengthening preventive measures and supervision would contribute to improving confidence in the financial sector (Figure 1.28). More effort should be put on on-site inspections of higher-risk financial institutions and on the regulatory framework for virtual asset providers (IMF, 2022).

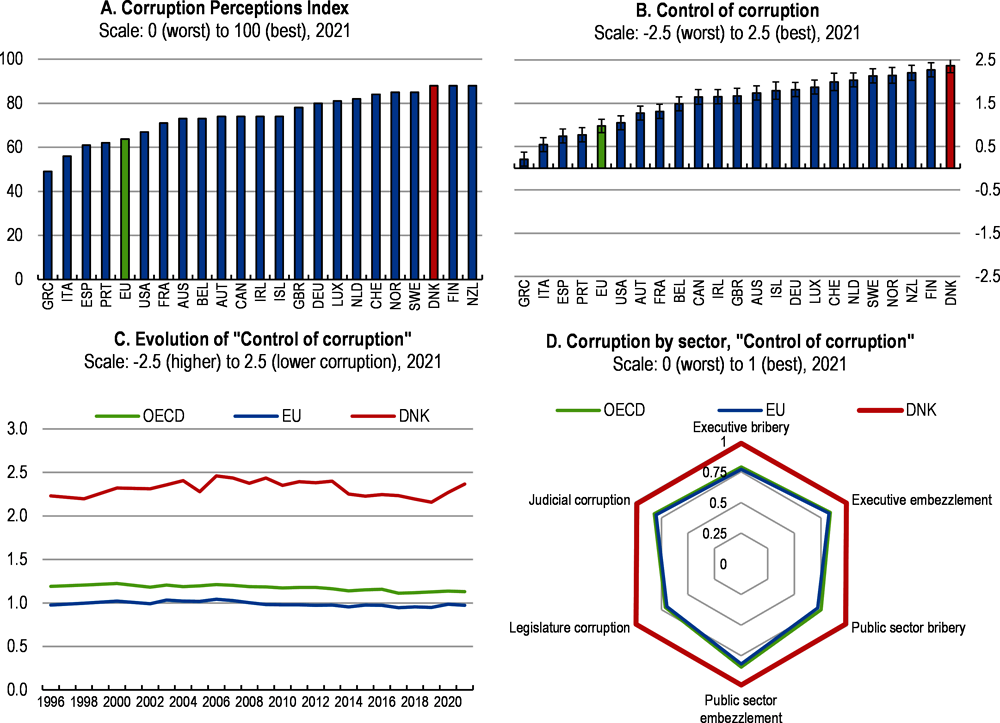

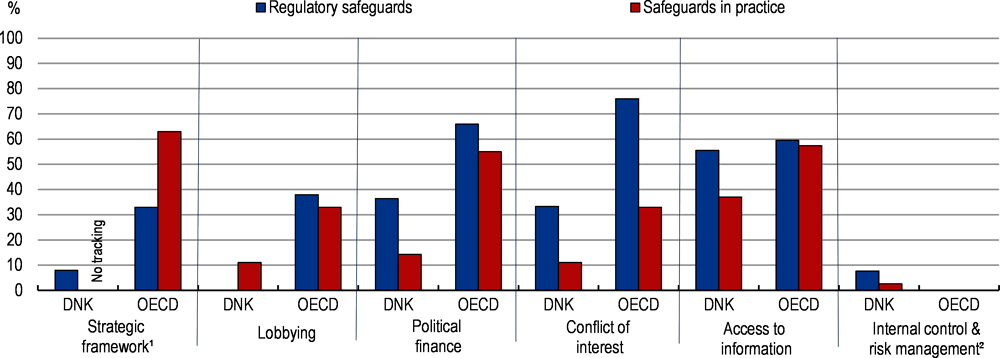

Denmark performs strongly in measures of perceived corruption and of reported bribery (Figure 1.29). The level of trust and satisfaction of citizens vis-à-vis public institutions is high, but public integrity issues exist and preventive measures against corruption risks need strengthening. By OECD standards, Denmark has weak integrity safeguards and controls against corruption risks (Figure 1.29). The OECD Public Integrity Indicators show that Denmark has not invested a strong strategic framework for anti-corruption and integrity. Both regulatory safeguards and practice in implementation consistently performs below the OECD average in the areas of lobbying, political finance, conflict of interest and access to public information. Denmark could strengthen regulatory safeguards in terms of internal control, internal audit, and risk management.

Government plans to reinforce openness and transparency in the law-making process, for instance by revising the Public Information Act, are a first step in the right direction. Shifting from ad hoc integrity policies to a comprehensive, risk-based approach in line with the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity as initiated in Sweden would contribute to limiting corruption risks. Achieving the highest standards of transparency in decision making processes, especially with respect to relationships with lobby groups, for instance by establishing a lobby register like done in Finland would avoid risks of distorting policy making. Independent handling of internal disciplinary procedures would improve trust in the government and the national administration.